- Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Training and Education Sciences, Edubron Research Group, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

In contrast with the plethora of studies on the academic motivation of regular students in regular educational settings, this study aims to shed light on the motivation and educational support needs of chronically ill children in hospital schools. This in-depth qualitative study seeks to explore whether the expected motivational dimensions central in SDT research are present in this specific population and setting and if the expected relationships with 'needs' are present. In contrast with research on academic motivation and needs in common classrooms, research on hospital schools is very scarce. Using the theoretical framework of self-determination theory, we investigated the presence of different types of motivation linked with ABC. More specifically, we investigated students' motivational types linked with the educational support needs that they expect their hospital school teacher(s) to address. A purposive selected sample of six students with severe chronic or long-term illnesses from three different hospital schools in Flanders (Belgium) was interviewed, using elicitation techniques to further deepen the data collection. Despite their chronic illnesses, all participating students were academically motivated, although some students indicated that not feeling well could cause temporary motivational regression. We were able to distinguish differences in motivation and expected need support. More controlled motivated students from the university hospital schools indicated a preference for support in terms of relatedness. More autonomously motivated students from a hospital school within a revalidation center showed more autonomous motivation and preferred competence support, instead of the autonomy-support that would be expected according to self-determination theory.

Introduction

A significant number of children suffer from chronic or long-term diseases (Boonen and Petry, 2012), ranging from 10 to 20% of children (Thompson and Gustafson, 1996; Phelps, 2006). This causes long-term absence from school (Boonen and Petry, 2012). According to this study, the continuous absence of chronically or long-term ill children from school is problematic, because education plays an extensive role in stimulating their cognitive growth, their sense of being normal and their psychosocial welfare. Steinke et al. (2016) state that adjusted education is essential in preserving academic continuity for these children. Crossland (2002) points out that an inability to achieve may threaten their self-image and result in frustration. Thies (1999) agrees: “Falling behind academically leads to catching up, and catching up takes time away from keeping up. Self-confidence and achievement motivation are undermined” (p. 395). These statements suggest that long-term or regular hospitalization may play a role in academic motivation which, in turn, affects academic engagement (Ryan and Deci, 2002), learning (Ryan and Deci, 2000) and academic performance (Vansteenkiste et al., 2006).

No research has yet been done on the motivation of students in hospital schools and what kind of educational support is needed and possibly related to their motivation. Bearing in mind that one of the major concerns of hospitalized children is the interruption of their pace of academic study (Lian and Chan, 2003), these aspects are interesting to explore.

Over recent decades, several international studies have extensively explored the motivation of adolescents and adults in different contexts, through self-determination theory (SDT) (e.g., Mullan et al., 1997; Reeve, 2002; Gagné and Deci, 2005), including how this motivation can be stimulated. Satisfying students' basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) is essential to enhance intrinsic motivation (Ryan and Deci, 2017).

Although SDT is defined as a universal motivation theory, Kaplan and Madjar (2017) discovered more nuance in it. They investigated in their study (published in this journal) whether students' perceptions about basic psychological need support are positively associated with their sense of relatedness, competence and autonomy. They found that the feeling of need support was very important irrespective of cultural background, whereas the feeling of relatedness could be related to different outcomes across cultures. This means that SDT could also function differently within specific contexts. Therefore, it is interesting to explore the relationship between motivation and psychological need support in the specific context of hospital school children. Are these children still motivated to put effort in their academic performances, despite their medical condition and psychosocial difficulties? Do they experience motivational problems? If so, what personal or contextual factors can explain these motivational difficulties? What psychological needs do these children have? How can these be met by their hospital school teacher(s)?

In comprehensive treatment for ill children, school and teacher support are important elements of a child's social environment. School is an important psychosocial environment, a tie to their normal life, their hope for the future and a condition for their future independent life (Becan, cited in Jenko and Lipec Stopar, 2015). Therefore, it would be useful to investigate the support needs of the students, alongside their academic motivation.

The aim of this study is to explore the academic motivation of students in hospital schools and the support they expect from their hospital school environment. This empirical research can contribute to SDT research, because it will be the first to investigate SDT in the specific context of hospital schools in combination with the target group. This study can also provide practical benefits for hospital school teachers and administrators. Knowing how students are motivated and how they want to be supported, can facilitate reflection about their teaching and support practices.

In what follows, we provide further theoretical background regarding the definition of ill children and support. We then argue why SDT theory can provide a useful lens to explore motivation and need support within this specific educational research context.

Theoretical Framework

Educational programs for Chronically Ill Children

Although there are many definitions available of chronic illness among children, in this study we follow the definition of RIZIV, the official public institution for social security in Belgium. According to RIZIV, “a chronically ill child is either a child that suffers from cancer, is treated chronically for kidney insufficiency via peritoneal or hemodialysis or suffers from another life-threatening disease that acquires a continuous treatment of at least 6 months or a repetitive treatment with the same duration” [Definition Chronically Ill Child (n.d.), 2019].

Not all children that receive special education because of their health issues suffer from a chronic disease. There are also those who experience a long-term illness causing a long period of hospitalization.

Given that illness and frequent or long-term hospitalizations impair a child's participation in school, educational interventions become an essential component in supporting this student population (Kaffenberger, 2006). Crossland (2002) states that school is important because of its central role in a child's development, and because it represents an area over which a health-impaired child can command some control.

Instead of attending a “regular” school, these children have other educational options, such as hospital schools, where customized educational programs can be run, adjusted to their needs. The specific content and form of these educational programs depend on the type of disease and treatment, but also on children's regular or long-term absence. This means that long-term or chronically ill children form a very specific target group.

Previous studies indicate that hospital schools (teachers) help students maintain a sense of normalcy (AAP, 2000; Ratnapalan et al., 2009). Moreover, in Lynch et al. (1993), parents expressed concerns regarding children's need for social and emotional support, as well as academic assistance. While developing programs and services for children with chronic illnesses, teachers need to be aware of these needs and concerns.

How education is provided in hospital schools can differ. There are several studies that discuss the differences between hospital schools in their educational programming (Ratnapalan et al., 2009; Steinke et al., 2016; Magalhães et al., 2018) as well as the intensiveness of educational services.

A similarity among hospital schools is that the hospital school teachers act as tutors. According to Bloom (1984), a tutor instructs one student, or two or three students simultaneously. Previous research has considered face-to-face human tutoring as an effective learning method (e.g., Cohen et al., 1982; Bloom, 1984; Chi et al., 2008). This means that in hospital schools, children are taught through a highly beneficial instruction method. Furthermore, Crossland (2002) proved that one-on-one teacher contact is a motivating factor in children's academic pursuits.

Hospital schools have not been widely investigated from an educational research perspective over the years. The few existing studies include diverse topics such as hospital school programming (Steinke et al., 2016), concerns of hospitalized children and their parents (Lian and Chan, 2003), adapting creative and relaxation activities to children with cancer (Jenko and Lipec Stopar, 2015). A focus on the quality and effects of these learning environments in hospital schools and on learning outcomes is clearly lacking in the educational research literature. Nevertheless, it is important for both theory and practice.

An exception is Crossland (2002), who investigated in a multiple-case study the efficacy beliefs and learning experiences of children with cancer in the hospital setting. Among other hypotheses, she investigated how self-efficacy beliefs influenced students' motivation to learn in this setting. She discovered that the hospital education experience for students who had no immediate expectation of returning to school was only moderately important and seemed to have a marginal impact on the children's academic motivation. Moreover, the motivational value of the hospital programs arose from the social interactions that the children had with their hospital teachers. Steinke et al. (2016) state that hospital teachers show ongoing compassion for their students and make a difference for them. According to Lian and Chan (2003), hospital school teachers can comfort the children and encourage them when it comes to their health condition.

These studies point to the importance of the supportive role of the hospital school teacher in these contexts, but it remains unclear whether all students expect such support in the same way.

In addition, Crossland (2002) highlights that during difficult periods when children were physically incapable of maintaining their high level of academic performance, their inability to achieve seemed to threaten their self-image and resulted in frustration. This suggests that support of the need for competence may be important for these children.

Although Crossland (2002) provided some motivational insights, her study was about the influence of self-efficacy beliefs on the learning experiences of children with cancer in a hospital setting, according to Bandura framework (Bandura, 1993). As stated by Bandura (1995), self-efficacy beliefs determine students' level of motivation. Apart from self-efficacy, there are other factors that enhance motivation, such as satisfying the needs of students. Self-efficacy and need satisfaction relate to different aspects of motivation. Therefore, it is interesting to investigate the motivation of students with chronic and/or long-term illness in terms of this need satisfaction. SDT provides a comprehensive framework to investigate students' needs and how these needs can be satisfied (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

Academic Motivation and Need Support

Self-determination theory states that “all individuals have natural, innate and constructive tendencies to develop an ever more elaborated and unified sense of self” (Ryan and Deci, 2002, p. 5). The foundation of SDT is a dialectical view concerning the interaction between an active, integrating human nature and social contexts that either nurture or hinder the organism's active nature (Ryan and Deci, 2002).

Through empirical investigation, SDT has identified three psychological needs that when satisfied, form the basis for optimal motivation and well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2017). These needs are also important to determine the conditions that foster those positive processes (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

The three needs are competence, autonomy and relatedness (abbreviated as 'ABC'). Competence is about feeling effective in one's ongoing interactions with the social environment and experiencing opportunities to exercise and express one's capacities (e.g., Deci, 1975; Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2017). Autonomy refers to the need to self-regulate one's experiences and actions (Ryan and Deci, 2017), in other words to be self-determined (Reeve and Sickenius, 1994). Relatedness is about feeling socially connected to others (Ryan and Deci, 2017), and having a sense of belongingness with other individuals (Deci and Vansteenkiste, 2004) and with one's community (Ryan, 1995). These psychological needs are claimed to be universal, as they represent innate requirements rather than acquired motives (Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2017). This means that they can be applied to thinking and acting in different domains, such as health care, education, work, sports, religion and psychotherapy (Ryan and Deci, 2000). When these needs are satisfied, they enhance intrinsic motivation (Reeve and Sickenius, 1994), but when thwarted, they lead to diminished motivation and lower well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

According to SDT, different types of motivation reflect the differing degrees to which the value and regulation of the requested behavior have been internalized and integrated. Two overarching motivation types in SDT are autonomous and controlled motivation. Autonomous motivation is found among students who want to learn without any pressure. This contrasts with controlled motivated students who learn because they feel more pressured to do so, mainly from external sources. The pressure originates from within the students or from the outside (Ryan and Deci, 2000). The processes through which non-intrinsically motivated behaviors can become truly self-determined and the ways in which the social environment affects those processes are highlighted by SDT (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

Considering that students are always in active exchange with their classroom environment according to SDT (Reeve, 2006), they need supportive resources from their environment to nurture these inner motivational resources (cf. autonomy, competence, and relatedness).

As stated by Reeve et al. (2004) teachers can appeal to autonomous motivation by providing structure and autonomy support. But can we apply this statement to chronically ill children in hospital schools?

Reeve (2006) explains that autonomy-supportive environments involve and nurture (rather than neglect and frustrate) students' psychological needs, personal interests and integrated values. A teacher's motivating style can be placed on a continuum that ranges from highly controlling to highly autonomy-supportive (Reeve, 2006).

Autonomy-support and structure should exist side by side in a mutually supportive way (Reeve, 2002). This statement is supported by Jang et al. (2010) and Hospel and Galand (2012) as they found evidence that support and structure function in a complementary way. Sierens et al. (2009) proved that “structure needs to be coupled with at least a moderate amount of autonomy support to have a positive association with self-regulated learning” (p. 65).

Now, exactly how are the basic psychological needs met when setting up an autonomy-supportive and structured learning environment? Reeve et al. (2007) state that autonomy support satisfies the need for autonomy, whereas structure satisfies the need for competence (Grolnick and Ryan, 1989).

There has been less research on teacher involvement, which feeds into the need for relatedness (Vansteenkiste et al., 2012). As stated earlier, this may be an important need of hospital school students.

This Study

Regular or long-term hospitalization can lead to students with chronic or long-term disease falling behind academically. This may lead to motivational regression or a decrease in the quality of motivation. There has been little research into the motivation of these students, and even less is known about these students' thoughts on teacher support in terms of the provision of autonomy, structure and relatedness. Can we expect that if students receive more autonomy support, it will go together with more autonomous motivation in this specific context?

As previous research in this area is scarce and the targeted sample is difficult to reach, we opted for an in-depth qualitative study using SDT (Ryan and Deci, 2017) as a theoretical lens to gain insight into how motivation and need support are perceived and assessed in the accounts of hospital school students. The qualitative research design also allowed us to gain insight into other influential factors, beyond those expected from SDT as a starting point.

The following research questions are central in this study:

1) Which types of academic motivation are present in the accounts of hospital school students?

2) What kind of educational support do students want in the learning environment (hospital school teachers) to fulfill their basic psychological needs?

3) What is the relationship between their academic motivation and preferred support?

4) What other influential factors stimulate or impede their academic motivation?

Methodology

Context and Sample

There are several options to acquire adjusted education for chronically ill children: homebound instruction (Boonen and Petry, 2012), synchronized online education (e.g., “Bednet” in Flanders), hospital schools and even education provided by a voluntary organization (School Ziekzijn, 2019). International research on students who attend hospital schools is limited.

Hospital schools are part of special education schools (teaching form 4, type 5) in Flanders where students receive a customized educational program, adjusted to their own individual needs. Hospital teaching is highly individualized in nature (Steinke et al., 2016); therefore, most instruction occurs one-on-one (Muylaert and Misplon, 2014). In such a context, the teacher acts as a tutor for the students.

In Flanders there were 440 children who attended one of the six secondary hospital schools in 2017–2018 (Prepublication Statistic Yearbook of Flemish Education, 2018). Magalhães et al. (2018) and Ratnapalan et al. (2009) discuss how educational services differ across hospitals, with great variability concerning organization, funding and structure. These considerations also apply to hospital schools in Flanders.

Every hospital school in Flanders is obliged by law to provide a minimum of 5 h per week of instruction to students (Structure Organisation of Special Secundary Education, 2019). Aside from this regulation, the amount of instruction can vary according to the health condition and educational needs of the student (principal of a university hospital school and vice-principal of the hospital school in a revalidation center, personal communication, 6th and 7th February, 2019). There seems to be a slight difference in average instruction time between a hospital school connected to a revalidation center and a hospital school linked to a university hospital. Data collection for this study was conducted in both settings, namely in two university hospital schools (hereafter referred to as university hospital school one and two), and in a revalidation center. In the hospital school connected to the revalidation center the average instruction time is around ten periods a week, against around eight in university hospital school one. The maximum instruction time is approximately 15 periods a week, provided that ample time is left for all necessary therapies and other health care treatments.

There were also differences regarding instruction methods between the two settings. The students in university hospital schools mostly receive one-on-one instruction, whereas students in the hospital school connected to the revalidation center are often divided into groups of two or three.

Participants were sought through purposive sampling followed by snowball sampling. Purposive sampling was used to gather participants with long-term or chronic illnesses who were enrolled in secondary hospital schools. This sample is frequently hospitalized and there is regular contact with the hospital school. Furthermore, these students between 12 and around 18 years old were expected to be better able to talk about abstract topics such as motivation and preferred educational support than their primary school peers (6-12 years old). As a result, they were expected to have more in-depth knowledge about the topics through experience (Ball, 1990), which justifies the choice for purposive sampling.

As there was no direct access to potential participants, every secondary hospital school in Flanders was contacted.

Three university hospital schools and one hospital school related to a revalidation center were prepared to support this research. The principal, teacher or coordinator of these hospital schools then recruited the participants, who were all included in the study. This procedure explains using snowball sampling (Cohen et al., 2007) because it allowed access to this difficult target groups through informal networks.

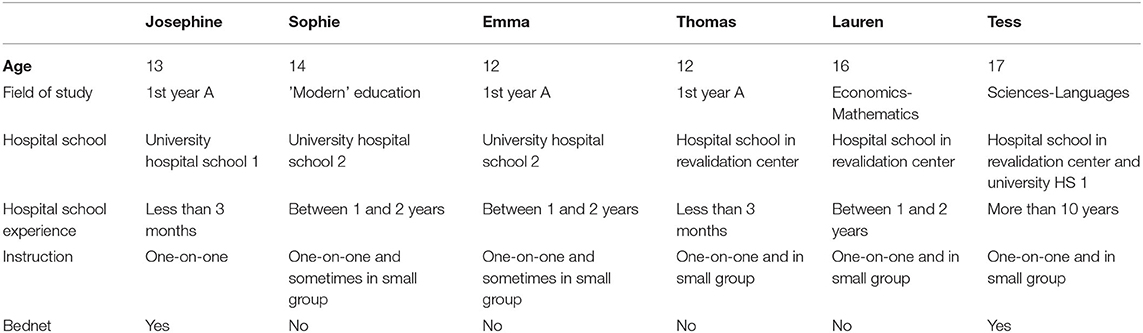

Specific information about the six students who participated in the study can be found in Table 1. There are two important aspects worth mentioning about two of the respondents. First, Sophie suffered a stroke, which left her unable to speak. As a result, she had to learn to speak all over again. She still experiences difficulty in finding the right words to express herself. Second, Lauren does not have any fellow students. She does not have a “home school,” because she will graduate at the end of the course of the examination committee.

The participants' parents signed an informed consent form to grant their permission for the interview. Before conducting the interview, students were asked if they participated voluntarily. Students' real names were replaced by pseudonyms to ensure their anonymity.

Instrument

Semi-structured interviews using elicitation techniques were carried out. The main questions were derived from the guiding SDT theoretical framework.

Questions about motivation, psychological needs and other conditions formed the core of the interview guide. To safeguard the construct validity of the interview guide, it was based on relevant literature. A pilot interview of a 13 year old was conducted to test the cognitive validity and the “flow” of the interview guide.

Closed-ended questions regarding motivation and elicitation techniques concerning need support were used to complement the interviews. Motivation and need support are relatively difficult topics for students to talk about. There was a concern that not every student would be able to talk about these constructs without significant support. That is why two self-report instruments accompanied the questions in the interview guide. Combining self-report instruments and in-depth interviews provided substantial and complementary data. The first instrument consisted of a set of items tapping academic motivation which were based on the Dutch version of the Academic Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SRQ-A; Vansteenkiste et al., 2009) and the Short Inventory of Learning Patterns (ILSSV; Donche et al., 2012; Vermunt and Donche, 2017). All motivation-items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “absolutely not important”; 5 = “very important”).

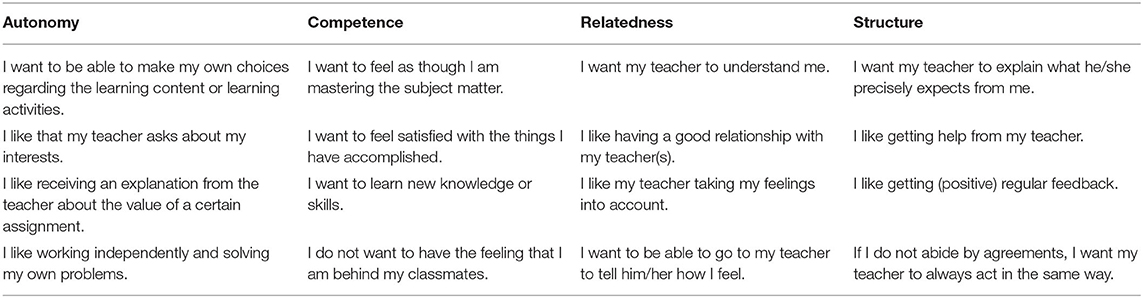

The second instrument as shown in Table 2 consisted of propositions (hereafter referred to as “items”) about need support that were derived from related literature (Reeve, 2006; Sierens et al., 2006; Vansteenkiste et al., 2007) ensuring its construct validity. During the interviews, students had to order the items by importance for them (very important, rather important, less important and not important). See Appendix A for an example of an item arrangement.

Procedure

The semi-structured interviews were carried out throughout the second half of January 2019. Closed-ended questions on motivation and elicitation techniques regarding need support were used during the interview to ensure elaborate responses. Students were asked to order items regarding need support according to their importance to them. Then, they were asked why they had chosen this arrangement.

All interviews took place in the hospital school classroom or at the bedside of the student, depending on their medical condition at the time of the interview. All interviews were taped and transcribed verbatim. The average duration of the interviews was around 30 min.

Data Analysis

To code the interviews, the qualitative data analysis computer software program Nvivo (version 12.3) was used. Thematic analysis was applied which facilitated identifying (semantic) themes or patterns in the data that were important or interesting (Braun and Clarke, 2013). The main interview questions were used as starting themes for analysis.

According to Braun and Clarke (2006), thematic analysis can be inductive or deductive depending on the role of theory. As SDT theory was used as a theoretical lens for this study, the interviews were deductively coded using a coding tree, in concord with relevant literature (research questions one, two and three). However, given its general and broad scope, the content for the fourth research question was coded inductively.

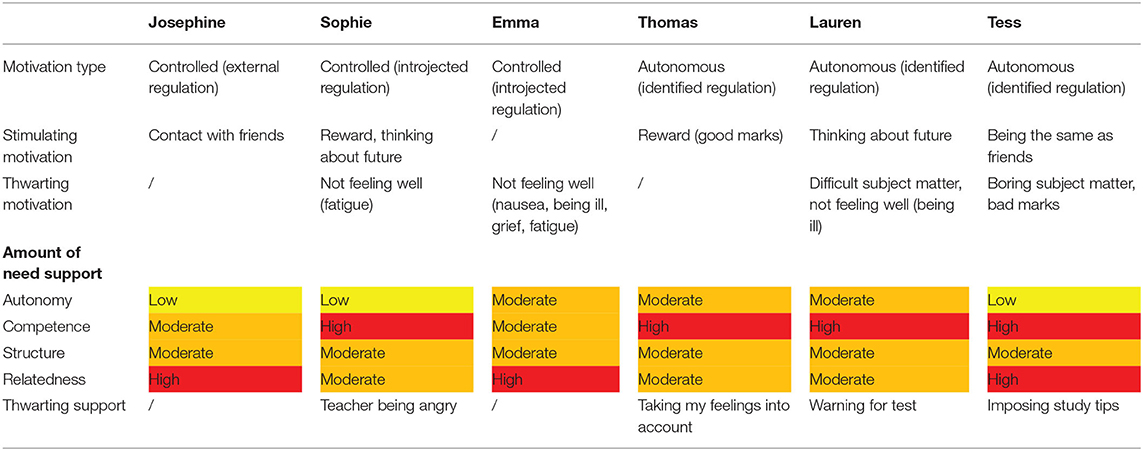

In addition to the qualitative data-analysis and interpretation, the self-reported data were inspected. Two Excel sheets were created to get an overview of the scores for (types of) motivation and to quantify the items about need support. The five motivational types were ranked using the closed-ended questions with a score from one to five. The scores for the motivational types concerning autonomous and controlled motivation were added up to get a score for both for each student. The items concerning need support were also given scores, ranging from one to four (one = not important, two = less important, three = rather important, four = very important). The scores were added up to get a total score per type of support for each student. This quantification enabled a further outline of the information and comparison between the respondents. Table 3 contains more information about the scores across respondents.

A second reviewer was appointed to code two of the interviews to support inter-rater reliability. The coding tree was found to be relatively extensive (see Appendix B), but all codes were used by both reviewers. There were only a few fragments that differed in assigned code. Those were fragments that raised reasonable doubt with both reviewers. After exploring the different possibilities, consensus was found on which code to use for these fragments. We can conclude that inter-rater reliability was high.

Results

Types of Academic Motivation

The first research question aimed to investigate possible differences in motivation types among students in hospital schools.

All interviewed students attach much importance to their studies. Most of them indicate the value of their studies for their future.

“Because later I … I have something. For example, if I have a degree and that way I can do later when I find a job, do the kind of work that I want to do.” (Thomas)

All students in this sample indicated in the interview that they were either moderately or strongly motivated. Josephine, Sophie and Tess scored high for both dimensions of motivation (controlled and autonomous) in the closed-ended questions, which suggests that they are highly motivated. This was not supported by what Josephine stated in the interview. There she indicated that she possessed a more moderate form of motivation, just like Emma.

In contrast to the students who scored high for both motivational dimensions (controlled and autonomous), Thomas, Emma and Lauren clearly preferred one of the two dimensions.

It is striking that none of the questioned students indicates to be amotivated. All students in this study are academically motivated in some way.

There were further differences among the interviewed students regarding motivation types. Josephine, Sophie and Emma are motivated in a more controlled manner, but further distinctions can be made. Josephine proved to be more externally motivated. She reported experiencing pressure from her parents, friends and teachers. Sophie's and Emma's motivation is more introjected. They pointed out that they would feel disappointed in themselves if they did not study (well).

“Studying is important and if you get bad marks, then I would feel so disappointed in myself because I haven't studied enough.” (Sophie)

Thomas, Lauren, and Tess are more autonomously motivated. These students displayed a more identified motivation, indicating that they seek extra learning or to learn something.

“Because I want to learn more. That I… [thinks]… because I just like to learn new things.” (Thomas)

The answers to the closed-ended questions support what the students said in the interview, but this does not apply to Thomas' answers. According to his scores on motivation types, he should be intrinsically motivated, but this cannot be confirmed based on what he says in the interview. There he never referred to studying as being fun.

Preferred Support From Teachers in the Learning Environment

The second research question aimed to investigate what kind of support students want from their social environment (hospital school teachers) to fulfill their psychological needs. We questioned both the preferred amount and quality of support in terms of ABC.

Regarding the amount of support, an equal number of students indicated the need for high, moderate or low support based on the interviews. On the contrary, the ordered items according to their importance show that all studied students want either moderate or high support from their hospital school teachers. Several students did not place any items in the column of “not important,” because they find any support relevant to some extent. It is also remarkable that the scores for autonomy support were lower than we expected, particularly regarding the students with autonomous motivation.

There were differences among students regarding the quality of their preferred support. Josephine and Emma proclaimed to have a high need for support concerning relatedness. Thomas, Tess and Sophie reported having a high need for competence support. Tess had a high need for relatedness and competence support. Her ordering of the items showed that she finds support in relatedness to be slightly more important than the need for competence support.

Most students from the hospital schools in the university hospitals preferred support in terms of relatedness.

“I don't want to have the feeling: I don't like that teacher. Because here it is like you are one-on-one and it's like uhm…” (Emma)

Every interviewed student of the hospital school of the revalidation center wanted a high amount of competence support from their hospital school teachers.

All questioned students found the need for structure moderately important. The need for autonomy support is perceived as being of low or moderate importance. Asking about their interests, working independently and solving their own problems are appraised to be less or not at all essential to them. Grounded in the arrangement of the items of all students in this study, support regarding relatedness and competence are equally perceived as most valuable to them. These forms of support are followed by structure, and autonomy support is ultimately considered to be the least important form of need support.

Relation Between Academic Motivation Type and Preferred Support

In this section we distinguish students with more controlled motivation and those with more autonomous motivation to discuss our findings.

Most questioned students with a more controlled motivation expressed a high need for support in terms of relatedness (see Table 3). They all find it important to have a good bond with their hospital school teacher and to have their hospital school teacher take their feelings into account. They referred to the fact that they are mostly alone with their teacher and rely on a good relationship with him or her.

“Yes, I find that important, because if I, I'll have to be here for another while. So if I have to sit here the whole time with a teacher that I don't like, then yeah, because I have to do a lot of lessons with her, so I just don't want that. That's why. Because in class you can still talk with people, you can just forget about that teacher, just focus on the lesson for a bit. But when she's sitting next to you, then it is like yeah no…” (Josephine)

All of these students want a teacher who understands them, particularly when they are not feeling well or have problems. Most students also specified that being able to go to their teacher to tell him/her how they feel is less important.

Sophie finds competence support more crucial than relatedness support, so she can be described as a deviant case among the students with a more controlled motivation. She pointed out that learning new knowledge and skills and being satisfied with the things she accomplishes are very important to her.

“Because I find it important that I learn something.” (Sophie)

Sophie also values feeling as though she knows the subject matter, because she finds it crucial to understand everything. She finds not wanting to fall behind her classmates rather important, because she does not like being the last one.

Although Sophie expressed a high preference for competence support, relatedness is of moderate importance to her. She finds support in terms of relatedness more important than autonomy support (low importance) or structure (moderate importance). To her, a teacher who understands her is essential. This implies that although relatedness support is not the most important to her, this kind of backup is perceived to be still more critical than structure and autonomy support.

Most students with a more controlled motivation in this sample state that autonomy support is of less importance to them. All of these students find working independently and solving their own problems not or less vital. They reported that they want their teacher to help them solve their problems.

“But now, I don't have to be independent. I just let my, if I have a problem, I just let someone solve it, because I already have a lot of problems. If I have to think about that as well. Ah, I don't understand that exercise, so I have to quickly ask that. I don't want that.” (Josephine)

Moreover, they all agreed that getting an explanation from their hospital school teacher about the value of a certain assignment is less important, since they can figure this out themselves. Being able to make their own choices about learning content or learning activities is valued by most students as less important. Emma states that she likes the opportunity to choose occasionally between different assignments, whereas Josephine indicates that in her home school she is not allowed to choose, so she wants to be treated in the same way. She feels that her teacher knows best what is important for her.

Finally, the hospital teacher asking about their interests is considered by most students as very or rather important. They find it pleasant when their teachers take their interests into account.

Regarding competence support, no interviewed students indicated that an item related to competence support was unimportant. It is clear that most of the more controlled motivated students assess this as moderately important. Most students want to feel satisfied about the things they have accomplished. All students indicated that learning new knowledge and skills is important to them. For the minority, feeling satisfied with what they have accomplished is rather important; they do not want to fall behind their classmates and they want to know the subject matter.

“I've had that a lot, but now I still think: oh, are they already in chapter five and I'm still at three. Then I have a feeling of…not so happy and also … [thinks] that I am less, but also that I seem to be… Then I have a strange feeling regarding the teacher like: Oh, do they want to teach? Or are they being too slowly?” (Emma)

As far as structure is concerned, questioned students with a more controlled motivation find this type of support moderately important. Every student pointed out that their teacher explaining what he/she exactly expects from them and getting help from their teacher are rather important to them. The students indicated that they want help from their teacher when necessary, when they do not understand something. All students expressed that getting (positive) regular feedback is less important to them.

“That's not necessary. (Sophie)

Most of these students declared that a teacher always reacting in the same way if they do not follow made agreements, is less important to them.

There is another example of structure support that Emma mentioned next to the given items. She added that putting a deadline on an assignment provides support for her.

The more autonomously motivated students (Thomas, Lauren and Tess) point out that receiving competence support is essential to them. Feeling as though they are mastering the subject matter is important to all pupils.

“Yes, that's nice huh. [smiles] If you go to class and every time you don't understand everything, that's not good. That would demotivate me if I would never understand anything.” (Lauren)

They want to understand the subject matter before doing a test. Furthermore, all of these students declared that feeling satisfied with what they have accomplished (in terms of getting good marks) and learning new knowledge or skills is either very or rather important to them. They like learning new things. No students (apart from Lauren) pointed out any items regarding competence support as less or not important. Lauren perceived not wanting to fall behind her fellow students as not important, as she does not have any classmates. Aside from the given items related to competence, Lauren also finds a teacher who has mastered his/her subject matter and supports her in that matter paramount to her.

Although Tess1 expressed competence support as very important, she indicated that relatedness support is even more essential to her. She qualified all items concerning relatedness as very important. She indicated that she wants a good relationship with her teacher, and that she likes getting respect and understanding from her teacher. She also wants her teacher to understand how she feels and to take her feelings into consideration.

“Yes, she doesn't have to be my best friend, but just that you do feel that she respects you and so on. And that's also nice that if you for a long time…have a real, a kind of super excellent bond with her.” (Tess)

Most autonomously motivated students in this study expressed that autonomy support is of moderate importance to them. Most of these students find it important to make their own choices about learning contents or learning activities and like having the option to choose. The majority of these students pointed out that getting an explanation about the value of a particular assignment is rather important to them. Lauren, for example, stated that if she finds something useless, she will not be interested. This clarification can help her. Interestingly, all of these students indicated that a teacher asking about their interests is less important.

“It actually doesn't matter whether a teacher, whether she likes to… Or that she knows that I like skiing or not, that doesn't make a difference.” (Tess)

Most of these students find wanting to work independently and solving their own problems less important. They state that it does not matter if a teacher asks about their interests or not.

Alongside autonomy support, relatedness support is moderately important to the more autonomously motivated students. Most highly value a teacher that understands them. They specify that they want their teacher to understand their problems or when they are not feeling well.

“If I don't have a good day, that she will understand.” (Tess)

Being able to go to their teacher to tell him/her how they feel is considered very or rather important by most questioned students with a more autonomous motivation. More specifically, they state that they want to be able to tell him/her about their problems or about not having a good day. Each item concerning relatedness was seen as less important by either Thomas or Lauren. Finally, none of the students specified an item concerning relatedness as unimportant.

Structure is specified by these students as moderately important. Most of them stated that their teacher explaining what he/she precisely expects from them is very dear to them. They declared that if they do not get this explanation, they find it difficult to conceive what the teacher means.

“Yes, again in a practical way, I don't like when they say: Just do some exercises by then. Then I want to know that exercise, on that page, by then, because otherwise it is not clear to me.” (Lauren)

Most interviewed students with a more autonomous motivation also pointed out that getting (positive) regular feedback, is less important to them. They specified that getting positive feedback is nice, but not always necessary. In addition, most students stated that getting help from their teacher is rather important. They specified that they only want help when things get difficult for them.

Their teacher always reacting in the same way if they do not follow agreements is also perceived by most as less important.

Next to the given items concerning structure, Tess indicated that teachers clearly communicating with her and with her home school can offer her support. Lauren stated that having an overview of the study matter for an exam and going over this with the teacher helps her to structure things.

Other types of support that questioned students find helpful, are creating a distraction, for example by implementing humor (Tess) and private lessons that lessen negative distractions (Sophie).

Types of support that students in this sample experience as thwarting are warnings regarding tests, teachers being angry and imposing study tips. When ordering the items, Thomas specified that his teacher taking his feelings into account is less important to him. However, he also mentioned this item to be a form of impeding support.

“If they take my feelings into account, I feel bad and then I'm also a bit ashamed.” (Thomas)

Other Influential Factors That Stimulate or Impede Academic Motivation

Students in this study were asked what other factors stimulated or impeded their academic motivation, aside from the items about needs they were confronted with. They pointed out two types of factors that influence their motivation: factors that relate to the satisfaction of the three psychological needs described in SDT, and factors that do not relate to SDT. Table 3 provides an overview of students' motivation types, factors stimulating or impeding their motivation, need support and thwarting support.

The interviewed students described factors concerning competence that stimulate or impede their motivation. A few students specified that thinking about the future, in terms of accomplishing something, being able to succeed again in their home school or getting a diploma enhances their motivation. Tess wants to graduate at the same time as her friends. Emma and Thomas pointed out that getting a reward strengthens their academic motivation. Thomas specified this reward in terms of getting good marks.

Furthermore, Lauren stated that when the subject matter is difficult, it thwarts her motivation. Tess added that bad marks decrease her motivation, which is another competence issue.

Josephine and Tess described another influential factor related to SDT, more precisely to relatedness. Tess indicated that she wants to be the same as her friends. Josephine emphasized that staying in contact with friends has a positive effect on her academic motivation.

“For example, I attend a lesson through Bednet. Because most of the time when I attend a lesson, there's a break after it sometimes. So, then I talk with friends, because they are allowed to stay during the break and I think that's fun. And then it gives me extra motivation to continue to still follow the lessons.” (Josephine)

The fourth research question concerns what other factors, besides the ones described in SDT, stimulate or impede the hospital school students' academic motivation. Several questioned students declared that not feeling well impedes their motivation. This discomfort, they say, can be caused by nausea, illness, grief and fatigue.

“I think that if I don't sleep well that I'll be less motivated. Actually, like those easy things that make you less motivated, such as nauseous or ill or sad. Things like that, more something sensitive, which make you less motivated.” (Emma)

Conclusion and Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the academic motivation of students in hospital schools and their expectations regarding support from their hospital school environment using SDT as a theoretical lens. Furthermore, we investigated whether other factors stimulated or impeded student motivation.

First, this study examined whether types of academic motivation within SDT could be distinguished among students in hospital schools. The academic motivation of all studied students was (reasonably) high: no student indicated being amotivated, despite their illnesses. This suggests that their illness does not affect academic motivation in such a way that students are not motivated at all. In addition, this research shows that their academic motivation is relatively stable over time according to the students' perceptions. Despite long-term or regular hospitalization, the quantity of their academic motivation is moderate or high and questioned students perceive their motivation quality as relatively stable. However, these students did admit that not feeling well because of nausea, illness or fatigue, can temporarily thwart their motivation. This proves Thies' (1999) statement about these children's motivation possibly being undermined during illness and hospitalization, but only as a temporary problem.

A further distinction could be made between students with a more controlled vs. a more autonomous motivation. SDT declares that students with a more controlled motivation experience pressure from within or from the outside (Ryan and Deci, 2017). Most interviewed students with a more controlled motivation claimed to experience pressure from within (introjected motivation). The minority indicated that they experienced pressure from other persons (external sources). Every student with a more autonomous motivation in this study portrayed identified motivation, which is the form of motivation that is almost completely internalized (Ryan and Deci, 2017). These students indicated that they voluntarily want to learn new things and that they see the relevance of studying. Thus, they perceive this behavior as personally important (Ryan and Deci, 2002).

The analyses made clear that in this sample all students from the university hospital school setting had a more controlled motivation, but every student from the hospital school in the revalidation center showed a more autonomous motivation. This suggests that the context in which students learn, as well as the types of treatments (which depend on their illnesses) may influence academic motivation types. As SDT states: there is an interaction between an active, integrating human nature and social contexts that either nurture or hinder the organism's active nature (Ryan and Deci, 2002). Caution is needed in confirming this finding, because the hospital (school) setting is not the only social context that has an influence on students' academic motivation; there may be other (contextual) factors that need to be taken into account.

The second research question concerned what kind of support students want from their social environment (hospital school teachers) and whether there is a relationship between their academic motivation type and preferred support. Although Ryan and Deci (2017) state that not all persons are conscious of the needs they want to be satisfied, in this study we can only rely on what students disclosed. An important observation is that all students in this study expressed needs in terms of autonomy, competence and relatedness, and in general, expected a moderate to high support from their hospital school teachers. Important differences were found between students with a more controlled vs. autonomous motivation. Most questioned students with a more controlled motivation found relatedness support most important. More autonomously motivated students in this study, pointed out that competence support was paramount to them. The importance of support regarding relatedness and competence is not surprising, because those were the two needs that were suspected to be important for ill children derived from Crossland's research (2002).

According to Reeve (2006), relatedness “revolves around a teacher-provided sense of warmth, affection and approval of students” (p. 233). Moreover, Ryan and Deci (2017) state that relatedness refers to feeling connected and significant among others. Students in this study who want more support from their teacher in terms of relatedness are looking for respect, understanding, consideration of their feelings from their teacher, and they want to tell their teacher how they feel. These aspects fit perfectly into Reeve's (2006) and Ryan's and Deci (2017) description. It is not unexpected to see this type of desired need support with most studied students from the university hospital schools, because the educational context may be influential. After all, Reeve (2006) points out that students “are always in active exchange with their classroom environment” (p. 226). The interviewed students in the university hospital schools never or rarely receive instruction in small groups. Most of the instruction is provided one-on-one; therefore a good relationship with their teacher is paramount. This provides an explanation for the need for relatedness support. Sophie was the only student of the university hospital setting that found competence support the most important. She was verbally less competent than her peers, a result of the stroke she suffered. This may clarify her strong need for competence support. It also feeds into the presumption mentioned earlier, namely that the type of illness and treatment may affect the type of support that students need the most.

Although Reeve et al. (2004) specified that autonomous motivation can be appealed to by providing structure and autonomy support, it is competence support that was perceived to be most relevant to the more autonomously motivated students in this study. Structure was of moderate importance to these students, which is foreseeable since structure also feeds the need for competence (Grolnick and Ryan, 1989). It is interesting to note that the hospital school students with a more autonomous motivation in this sample did not consider autonomy to be very important to them, which would be expected according to SDT. After all, SDT is a macro-theory that should be applicable to many different domains. Though, the specificity of the research context might have induced these more divergent results. Most questioned students with a more autonomous motivation declared that they did not find it important to work independently and solve their own problems. A possible clarification may lie in the fact that they could feel isolated. We may also not forget that these students already have a lot of problems to deal with. This could be another plausible explanation for the fact that they do not find autonomy support to be that crucial. Most interviewed students did express the need for a moderate amount of autonomy support. Sierens et al. (2009) proved that you need at least a moderate amount of autonomy support alongside structure to have a positive association with self-regulated learning, which seemed the case for the majority of the more autonomously motivated students in regular classroom settings.

Next to the given items, students in this study pointed out some other forms of support that help or hinder them. Helpful support in terms of structure involved setting deadlines. The perceived competence of teachers can support students' feelings of competence. Introducing distraction and private lessons were also considered to be supportive. Support that these students experienced as hindering were warning regarding tests, teachers being angry and imposing study tips. Most of these methods of thwarting support were indicated by the more autonomously motivated students. These forms of hindering support are all examples of a controlling teaching style. This style is characterized by, for example, teachers building up pressure, giving commands and using forceful language, which does not support autonomous motivation (Vansteenkiste et al., 2007). Therefore, it is not surprising that (mostly) more autonomously motivated students in this study indicated these types of support as hindering.

Questioned students also provided factors that impeded or thwarted their motivation, next to the items about the three psychological needs. Several of these students indicated that their education is important for their future and that thinking about the future enhances their motivation. Thinking about the future entailed accomplishing something, being able to succeed again in their home school or getting a diploma. On the contrary, boring or difficult subject matters and bad marks were perceived as thwarting their academic motivation. These factors all reflect the need for competence. Moreover, some of the interviewed students felt that a connection to their friends stimulated their academic motivation, which refers to the need for relatedness. Strikingly, this way of stimulating academic motivation was indicated by the students attending lessons through synchronized online education (Bednet) in this study. This confirms that education can help students maintain their connections with their world beyond the hospital (Magalhães et al., 2018).

The fourth research question involved other influential factors that stimulate or impede students' academic motivation. Several students said that not feeling well impedes their motivation. This hardship can be caused by nausea, illness, grief and fatigue.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Some limitations of this study need to be taken into consideration. Given the exploratory nature of this study, the particular research setting and the difficulty of finding suitable respondents, the sample size is rather small. Only six students were interviewed. The majority were girls and all of them received general secondary education. Future research should strive for a broader sample with a balance between sexes and more variation regarding education levels. Nevertheless, all possible efforts were made to enlarge this sample, but gaining access to these children proved to be extremely difficult.

Another limitation lies in the fact that students were confronted with several elicitation techniques. By using closed-ended questions, we might have induced unintended answering effects. However, constructs such as motivation and need support are not easy to talk about. Due to the provided structure, students were able to talk extensively about the two constructs. Aside from the given items, they did come up with other examples or forms of support. Moreover, when students were asked about the required quantity of support, their answer ranged from low to high support. However, through ordering the items, it became clear that a few of them wanted more support than they first indicated. This means that they may not have fully understood what “support” entailed until they were confronted with the items. This again proves that using the instrument was a sound choice.

A further limitation is the cross-sectional nature of this study. The motivation and need support of these students were investigated at a certain time in their treatment. Observing these students in these specific contexts in a more longitudinal way could provide more information about the developing relationship between motivation and forms of need support. However, setting up this type of data collection in the context of hospital schools and specific medical treatments would be challenging, as it would require extensive funding and long-term dedication from a team of researchers.

Finally, it would be interesting for researchers to conduct a contrastive study of the motivation of hospital school students compared to the motivation of 'regular' students. For example factors that are perceived as thwarting the motivation of hospital school students, such as boring subjects, receiving bad marks and fatigue, can be expected to thwart the motivation of regular students as well.

Contribution

Despite the limitations mentioned above, this study contributes to the empirical research on SDT by investigating SDT in the context of hospital schools and chronically ill children. This research points out individual differences in motivation and educational support needs. It offers teachers insight into qualitative differences in motivation and the interplay between motivation and needs.

Moreover, this research offers evidence that students' motivation in hospital schools is related to preferences for educational support. When teachers give their students the chance to reflect on their academic motivation and support needs, they can use these insights to negotiate together which kinds of educational support could be realized in this specific teaching environment, and how this approach could enhance student motivation and learning.

Data Availability Statement

Parents were not asked if we could use the data for research goals other than the research their children participated in. More specific information about interpretation and data analysis can be obtained through the corresponding author upon request. The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

TM and VD contributed to the conception and the design of this study. TM was responsible for the data collection. Data analyses and interpretation of the data were conducted by TM. VD supported and critically revised the analyses. TM outlined the manuscript. VD critically revised this manuscript and made suggestions for improvement. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnote

1. ^Tess is the only pupil that has experience with two different hospital schools (cf. Table 1). She is mostly taught in the hospital school in the revalidation center. When she is admitted to the university hospital, she receives instruction in university hospital one.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on School Health. (2000). Home, hospital, and other non-school-based instruction for children and adolescents who are medically unable to attend school. Pediatrics 106, 1154–1155. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.5.1154

Ball, S. J. (1990). Self-doubt and soft data: social and technical trajectories in ethnographic fieldwork. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Ed. 3, 157–171. doi: 10.1080/0951839900030204

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educ. Psychol. 28, 117–148. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3

Bandura, A. (1995). “Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies,” in Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies, ed A. Bandura (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 1–45. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511527692

Bloom, B. S. (1984). The two-sigma problem: the search for methods of group instruction as effective as one-to-one tutoring. Educ. Res. 13, 4–16. doi: 10.3102/0013189X013006004

Boonen, H., and Petry, K. (2012). How do children with a chronic or long-term illness perceive their school re-entry after a period of homebound instruction? Child Care Health Dev. 38, 490–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01279.x

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE Publication.

Chi, M. T., Roy, M., and Hausmann, R. G. (2008). Observing tutorial dialogues collaboratively: insights about human tutoring effectiveness from vicarious learning. Cogn. Sci. 32, 301–341. doi: 10.1080/03640210701863396

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education, 6th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203029053

Cohen, P. A., Kulik, J. A., and Kulik, C.-L. C. (1982). Educational outcomes of tutoring: a meta-analysis of findings. Am. Educ. Res. J. 19, 237–248. doi: 10.3102/00028312019002237

Crossland, A. (2002). Efficacy beliefs and the learning experiences of children with cancer in the hospital setting. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 48, 5–19.

Deci, E. L., and Vansteenkiste, M. (2004). Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction: understanding human development in positive psychology. Ricerche Psicol. 1, 23–40.

Definition Chronically Ill Child (n.d.) (2019). Law Concerning the Mandatory Insurance for Medical Care and Payments. Retrieved from: https://www.riziv.fgov.be/webprd/docleg/sp/?1&tmpl=kartlis&OIDN=1503577&-VIEW=1&ulang=nl (accessed November 29, 2019).

Donche, V., Coertjens, L., Vanthournout, G., and Van Petegem, P. (2012). Providing constructive feedback on learning patterns: an individual learner's perspective. Reflect. Educ. 8, 114–131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067854

Gagné, M., and Deci, R. M. (2005). Self-determination and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 26(4), 331–362. doi: 10.1002/job.322

Grolnick, W. S., and Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children's self-regulation and competence in school. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 143–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.81.2.143

Hospel, V., and Galand, B. (2012). Are both classroom autonomy support and structure equally important for students' engagement? A multilevel analysis. Learn Instr. 41, 1–10. doi: 10.016/j.learninstruc.2015.09.001

Jang, H., Reeve, J., and Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: it is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 588–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019682

Jenko, N., and Lipec Stopar, M. (2015). Adapting creative and relaxation activities to students with cancer. Int. J. Special Educ. 30, 4–12.

Kaffenberger, C. (2006). School reentry for students with a chronic illness: a role for professional school counselors. Prof. School Counsel. 9, 223–230. doi: 10.5330/prsc.9.3.xr27748161346325

Kaplan, H., and Madjar, N. (2017). The motivational outcomes of psychological need support among pre-service teachers: multicultural and self-determination theory perspectives. Front. Educ., 2:42. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00042

Lian, M.-G. J., and Chan, H. N. H. (2003). Major concerns of hospitalized school-age children and their parents in HongKong. Phys. Disabil. Educ. Relat. Serv. 22, 37–49.

Lynch, E. W., Lewis, R. B., and Murphy, D. S. (1993). Educational services for children with chronic illnesses: perspectives of educators and families. Except. Children 59, 210–220. doi: 10.1177/001440299305900305

Magalhães, P., Mourão, R., Pereira, R., Azevedo, R., Pereira, A., Lopes, M., et al. (2018). Experiences during a psychoeducational intervention program run in a pediatric ward: a qualitative study. Front. Pediatrics 6:124. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00124

Mullan, E., Markland, D., and Ingledew, D. K. (1997). A graded conceptualisation of self-determination in the regulation of exercise behaviour: Development of a measure using confirmatory factor analytic procedures. Pers. Individ. Differ. 23, 745–752. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00107-4

Muylaert, I., and Misplon, L. (2014). Een descriptief-exploratief onderzoek naar het vervolgonderwijs van leerlingen uit de Ziekenhuisschool Stad Gent (Unpublished master thesis), Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium.

Phelps, L. (2006). Chronic Health-Related Disorders in Children: Collaborative Medical and Psychoeducational Interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/11435-000

Prepublication Statistic Yearbook of Flemish Education (2018). Statistisch Jaarboek van het Vlaamse Onderwijs. Retrieved from: https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/statistisch-jaarboek-van-het-vlaams-onderwijs-2017-2018#Excel (accessed October 15, 2018).

Ratnapalan, S., Rayar, M. S., and Crawley, M. (2009). Educational services for hospitalized children. Paedriatr. Child Health 14, 433–436. doi: 10.1093/pch/14.7.433

Reeve, J. (2002). “Self-determination theory applied to educational settings,” in Handbook of Self-Determination Research, eds E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 183–203.

Reeve, J. (2006). Teachers as facilitators: what autonomy-supportive teachers do and why their students benefit. Elem. Sch. J. 106, 225–236. doi: 10.1086/501484

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., and Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students' engagement by increasing teachers' autonomy support. Motiv. Emot. 28, 147–169. doi: 10.1023/B:MOEM.0000032312.95499.6f

Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., and Jang, H. (2007). “Understanding and promoting autonomous self-regulation: a self-determination theory perspective,” in Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research and Application, eds D. Schunk and B. Zimmerman (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 223–244.

Reeve, J., and Sickenius, B. (1994). Development and validation of a brief measure of the three psychological needs underlying intrinsic motivation: the AFS scales. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 54, 506–515. doi: 10.1177/0013164494054002025

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychologial needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. J. Pers. 63, 397–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2002). “Overview of self-determination theory: an organismic dialectical perspective,” in Handbook of Self-Determination Research, eds E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan (Rochester, NY, US: University of Rochester Press), 3–33.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory. Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development and Wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sierens, E., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., and Dochy, F. (2006). De authoritatieve leerkrachtstijl: een model voor de studie van leerkrachtstijlen. Pedagogische Studiën 83, 419–431.

Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., and Dochy, F. (2009). The synergetic relationship of perceived autonomy support and structure in the prediction of self-regulated learning. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 79, 57–68. doi: 10.1348/000709908X304398

Steinke, S. M., Elam, M., Irwin, M. K., Sexton, K., and McGraw, A. (2016). Pediatric hospital school programming: an examination of educational services for students who are hospitalized. Phys. Disabil. Educ. Relat. Serv. 35, 28–45. doi: 10.14434/pders.v35i1.20896

Structure Organization of Special Secondary Education (2019). Retrieved from: https://data-onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/edulex/document.aspx?docid=14309

Thies, K. M. (1999). Identifying the educational implications of chronic illness in school children. J. School Health 69, 392–397. doi: 10.1111/j1746-1561.1999.tb06354.x

Thompson, R. J., and Gustafson, K. E. (1996). Adaptation to Chronic Childhood Illness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/10188-000

Vansteenkiste, M., Sierens, E., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Dochy, F., Mouratidis, A., et al. (2012). Identifying configurations of perceived teacher autonomy support and structure: associations with self-regulated learning, motivation and problem behavior. Learn. Inst. 22, 431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.04.002

Vansteenkiste, M., Zhou, M., Lens, W., and Soenens, B. (2006). Experiences of autonomy and control among Chinese learners: vitalizing or immobilizing? J. Educ. Psychol. 97, 468–483. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.468

Vansteenkiste, M, Sierens, E., Soenens, B., and Lens, W. (2007). Willen, moeten en structuur: over het bevorderen van een optimaal leerproces. Begeleid Zelfstandig Leren 37, 1–27.

Vansteenkiste, M, Sierens, E., Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., and Lens, W. (2009). Motivational profiles from a self-determination perspective: the quality of motivation matters. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 671–688. doi: 10.1037/a0015083

Vermunt, J. D., and Donche, V. (2017). A learning patterns perspective on student learning in higher education: state of the art and moving forward. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 29, 269–299. doi: 10.1007/s10648-017-9414-6

Ziekzijn, S. (2019). Leren Kan, Ook Voor Wie Ziek Is. Available online at: https://www.s-z.be (accessed January 18, 2020).

Keywords: hospital school, education, illness, needs, autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, relatedness

Citation: Mombaers T and Donche V (2020) Hospital School Students' Academic Motivation and Support Needs: A Self-Determination Perspective. Front. Educ. 5:106. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00106

Received: 28 January 2020; Accepted: 05 June 2020;

Published: 14 July 2020.

Edited by:

Waganesh A. Zeleke, Duquesne University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lynne Sanford Koester, University of Montana, United StatesMing Lui, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong

Copyright © 2020 Mombaers and Donche. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tine Mombaers, dGluZS5tb21iYWVyc0B1YW50d2VycGVuLmJl

Tine Mombaers

Tine Mombaers Vincent Donche

Vincent Donche