- School of Education, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Feminist epistemology ensures women's ways of seeing are central to research purpose and process. In particular, feminist standpoint theory, including Black feminist standpoint theory, recognizes epistemic privilege. Situated knowledge, what is known and the ways it can be known, is shaped by the positionality of knowledge producers in studying upwards to expose oppressive social structures. A reflexive approach prompts feminist researchers to reflect deeply on the situation and perspective of their position in relation to the focus of research. The research process with women school leaders of diverse heritages led the author to re-examine her personal and professional story, as well as her scholarship, as a white woman of working class origins, raised, educated, and working in education as an educator, school leader, initial teacher educator, educational leadership and management programme leader, and scholar in the UK. The author developed a heuristic device for reflection as a “7 Up” intersectionality life grid to think about her life in education at 7 year intervals in relation to the experience of learning, educating, leading, and researching in the context of unequal gender, class, and race relations in wider society. The process revealed white supremacy, white privilege, and white fragility in her lived reality and scholarship. This re-examination enabled her to deepen understanding of her positionality and position-taking as it relates to work in the field of women, gender, and educational leadership. In this critically reflexive autoethnography, I report on reflections guided by the 7 year intervals of the “7 Up” framework at nine points (birth to 56 years old) as reflexivities of complacency, reflexivities that discomfort and reflexivities that transform. Following feminist theorists who think with and against Bourdieu's social theory, I draw on the concepts of misrecognition and symbolic violence, and for the first time in work on intersectionality in educational leadership, hysteresis to theorize about complicity with white supremacy, the accrual of white privilege and examples of white fragility. The “7 Up” intersectionality life grid tool has capacity to prompt the critically reflective and transformative self-narrative work essential to feminist scholars. It is also a valuable tool for critical reflexivity among women and men students, educators, leaders, and learners of diverse heritages across national contexts. Engaging with reflexivities that discomfort has the potential to transform self-narratives, construct relationships, and carry out and interpret research differently.

Reflexive Practice in Feminist Research

Deliberations about representation, research goals and who has the “right,” or is best placed, to conduct research with whom are problems for already privileged academics simultaneously “damned if you do and damned if you don't” include women of heritages not shared by the researcher herself (Patai, 1994, p. 66). Acknowledging positionality and its influence on the research process from design to dissemination is essential in ethical critical feminist qualitative research (Sikes, 2010). Doing research differently means establishing a degree of reciprocity between researcher and participant in resisting the temptation to speak for another. A reflexive approach prompts deep reflection on a scholar's position in relation to the research focus. It is a methodological tool used to “better represent, legitimize, or call into question [our] data” (Pillow, 2003, p. 176), useful as a component of a feminist epistemology ensuring women's ways of seeing are central to both research purpose and process. Feminist standpoint theory recognizes epistemic privilege (Harding, 1991; Collins, 2000). Situated knowledge, what is known and the ways it can be known, is shaped by the positionality and politics of knowledge producers. Analyses of hierarchical social structures is informed by distinctive standpoint insights from a group consciousness perspective; it requires “studying up” (Harding, 2004, p. 30).

Self-reflexivity (self-disclosure), and reflexivity as recognition of another validate knowledge claims to assert transcendence of our “own subjectivity and own cultural context in a way that releases [us] from the weight of (mis)representations” (Pillow, 2003, p. 186). Declarations of positionality by white scholars pre-empt accusations of re-colonizing research participants in voyeuristic ways. As such, reflexivities may lead to complacency. Ironically so, when critical reflexivity aims to disrupt the complacency associated with positivism (May and Perry, 2011).

Reflexivity, or reflexive practice, is also about transforming habitus i.e., embodied “systems of durable and transposable dispositions” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 72), through the “awakening of consciousness and socioanalysis” (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 116). Reflexivities and pedagogies of discomfort question the construction and representation of differences in relation to power and domination (Pillow, 2003; Blackmore, 2010). They serve as a researcher's rigorous, disruptive set of “critical self-disturbances” (Fuller, 2017a, p. 105) and ongoing self-critique enabling a re-narration of self that, in turn, informs a fresh understanding of diverse narratives. Questions asked here concern a scholar's reflexive practice and are about the process of re-narration. How are our ways of seeing ourselves in the world transformed by working with others to see ourselves as another sees us? What sort of tool might deepen reflection to deconstruct and reconstruct self-narratives developed over time that lead to more socially just practice?

The purposes of conducting a critical autoethnography were: to further develop scholarly reflexive practice; to try to see myself as another sees me (Laible, 2003) by re-examining my self-narrative through a race lens in an attempt to achieve “double-consciousness” (Du Bois, 1903, p. 2); to establish reciprocity in self-disclosure; and to expose misrecognition i.e., the long-forgotten arbitrariness of social divisions relating to gender, class, and race (Bourdieu, 1977). The major contributions of this paper to the field of women and gender in educational leadership relate to method and the theorization of intersectionality in educational leadership.

Adopting a critical race perspective, I use the concepts of white supremacy, white privilege and white fragility. White supremacy is “the recognition that race inequity and racism are central features of the education system. These are not aberrant nor accidental phenomena that will be ironed out in time, they are fundamental characteristics of the system” (Gillborn, 2005, p. 498).

White privilege refers to “the expression of whiteness through the maintenance of power, resources, accolades, and systems of support through formal and informal structures and procedures” (Bhopal, 2018, p. 19). It is “an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, maps, passports, codebooks, visas, clothes, tools, and blank checks” or “an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was ‘meant’ to remain oblivious” (McIntosh, 1988, p. 1). White fragility is “triggered by discomfort and anxiety, it is born of superiority and entitlement. White fragility is not weakness per se. In fact it is a powerful means of white racial control and the protection of white advantage” (DiAngelo, 2018, p. 2). The focus on race is designed to expose complicity with white supremacy in the English education system (Gillborn, 2005), reveal the benefits accrued by virtue of white privilege (Bhopal, 2018) and to recount discomforting race moments (Rollock, 2013) as examples of white fragility (DiAngelo, 2018).

The paper comprises a brief review of selected critical autobiographical and auto-ethnographical accounts by feminist scholars of educational leadership and an outline of key Bourdieuian concepts: misrecognition, hysteresis, and symbolic violence. Reflexive research with women of diverse heritages led to developing a tool that transformed my self-narrative enabling me to see myself more clearly as another might see me. I describe the use of gender, class, and race lenses in the development of the “7 Up” intersectionality life grid. Next, I present findings from a critical autoethnographical study as they relate to three categories of reflexivity: reflexivities of complacency associated with the comfortable and familiar; reflexivities that discomfort as those familiar accounts that are nevertheless painful; and reflexivities that transform as new and uncomfortable self-critical disturbances. Using Bourdieu's concepts of hysteresis and misrecognition, there follows a discussion of the shifting self-narrative: from a discourse of upward social mobility (Reay, 2017) to one of accruing the benefits of white privilege (Bhopal, 2018). Finally, I suggest how the tool might be useful to learners, educators, leaders, and scholars undertaking similar self-work in their reflexive scholarship and professional practice across phases, sectors, and national contexts.

Feminist Scholars' Self-Narratives

Feminist and gender theorists have long engaged in critically reflexive scholarship. The personal is political articulates the connection between individual experiences of gender inequalities and the political, social, and organizational structures perpetuating gendered oppressions (Weaver-Hightower and Skelton, 2013). The theorization of women's individual stories within feminist frameworks critiques and challenges inequalities in education and broader society (Shakeshaft, 2015). Self-narratives form the basis of feminist standpoint theory (see Smith, 1979; Harding, 1991; Collins, 2000; Ladson-Billings, 2000) that values “insider” perspectives. Those standpoints uncover multilevel power relations perpetuated by patriarchy, capitalism, and colonialism as they are played out in families, institutions (including education), society, and international relations. This remains relevant in the twenty-first century in the light of misogynist and racist political discourses [e.g., during the 2016 US presidential election campaign (England, 2017); leading up to and following the UK decision to leave the European Union in 2016 (Isaac and Hilsenrath, 2016)].

Scholars of educational leadership recount personal experiences as stories of “female firsts” (Mertz, 2009, p. 6), connecting them with research as intellectual histories (e.g., Blackmore, 2013; David, 2013), critical evocative portraiture (Lyman et al., 2012, 2014), and collaborative autoethnographies (Newcomb, 2014). So doing, they engage with epistemologies and methodologies that disrupt traditional ways of knowing about education and educational leadership (Young and Skrla, 2003). Many recount the “multiple marginality” (Mertz, 2009, p. ix) at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender (see e.g., Rusch and Jackson, 2009; Grant, 2014; Jean-Marie, 2014; Martinez, 2014; Osanloo, 2014; Peters, 2014; Santamaría and Jaramillo, 2014; Welton, 2014). Critical reflexivity reveals the intercontinental perspectives of scholars committed to social justice leadership to demonstrate what informs and motivates their work (Lyman et al., 2012).

From a critical race perspective, UK scholars have contributed counter narratives about intersecting oppressions in higher education (e.g., Ahmed, 2009; Chakrabarty, 2012) but not necessarily as accounts by scholars of gender and educational leadership. One exception is Showunmi's (2018) account of a Black woman's socialisation as white and the multiple discriminations and oppressions faced from every quarter in not being sufficiently Black or white to meet colleagues' expectations in higher education.

Accounts by white scholars confronting the “other within” (Blackmore, 2010, p. 45) and their own “complicit[y] in the whiteness of educational leadership” remain rare (Blackmore, 2013, p. 26) (see also Rusch and Horsford, 2009; Mansfield, 2014; Fuller, 2017a). Their scarcity indicates the prevalence of “white fragility” (DiAngelo, 2018, p. 2), i.e., the inability to engage in dialogue about race and desire to retain white privilege in the field (Bhopal, 2018). Accounts by white scholars of “seemingly peripheral race moments” (Rollock, 2013, p. 492) are needed in race and educational leadership research.

White researchers electing to carry out race research have a particular responsibility to critically reflect upon and demonstrate awareness of these issues. They must remain alert to and report on the dynamics of race and their responses to it. To do so not only ensures the development of critically reflexive practice but also remains crucial to making the processes of whiteness visible. To do otherwise, to remain silent about these processes even while researching race is to enact and endorse a paradigm interred in racial division and hierarchy. (Rollock, 2013, p. 506-7)

This “scholastic self-reflexivity” assists the theorisation of privilege and the reflexive process (Wilkinson, 2008, p. 111) that might facilitate the unlearning of privilege (Rusch and Horsford, 2009). Declaring white privilege is not enough; its abolition must be the goal (Ignatiev, 1997; Ahmed, 2004).

Reflexivity, Misrecognition, Hysteresis and Symbolic Violence

There is no neat dovetail between gender and feminist theories and Bourdieu's social theory. Indeed, feminist scholars have fruitfully thought with and against Bourdieu by troubling his work with respect to gender (see e.g., Moi, 1991; Lovell, 2000; Adkins, 2004). I have struggled with the apparent permanence of masculine domination, a theorisation of gender binaries, limited recognition of contemporary post-structural gender theorisation (e.g., Butler, 1990) and feminist activism (e.g., the Women's Movement) (Bourdieu, 2001). But there is precedence in using key Bourdieuian concepts as thinking tools in education research (e.g., Reay, 2004), including from a critical race perspective (e.g., Rollock et al., 2015), and scholarship in educational leadership (e.g., Thomson, 2017) including with an intersectionality perspective (Fuller, 2013, 2018). Following Moi (1991, p. 1035), I see gender and race as social categories, like social class, that belong “to the ‘whole social field’ without specifying a fixed and unchangeable hierarchy between them.” In this section, I outline some of Bourdieu's key concepts.

Bourdieu's theory of practice (1977) and account of masculine domination (2001) demonstrate the relationship between reflexivity, misrecognition, hysteresis and symbolic violence. For Bourdieu, reflexivity is a “sociology of sociology” requiring scholars to reflect on practice and position (in relation to the research field and its participants) to avoid “unconscious projection” of these relations to the research process, analyses, and interpretations (Deer, 2014, p. 197), rather than to value an “insider” perspective. However, there is also concern for ethnocentrism and the scholarly gaze (Bourdieu, 1977) that resonates with concerns related to reflexivity in feminist standpoint theory (Harding, 1991; Pillow, 2003). Both Bourdieu's reflexive practice (1977) and feminist standpoint scholarship “study up” from individuals to theorise about unequal social structures (Harding, 2004 p. 182–31).

Challenges to the prevailing doxa, the “natural or social world [that] appears as self-evident,” or “the naturalization of arbitrariness” in the established social order, needs mediation by the reflexive social scientist (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 163). In feminist standpoint scholarship, the political perspective positions women as knowers and recognises knowledge production is for women (Harding, 2004); they are capital-accumulating subjects rather than capital-bearing objects (Lovell, 2000). Bourdieu acknowledges the arbitrariness on which divisions (sex, class, race) reproduce power relations and the associated symbolic violence, constitutes, and produces misrecognition “of the limits of cognition that they make possible, thereby founding immediate adherence, in the doxic mode, to the world of tradition experienced as a ‘natural world’ and taken for granted” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 164). Reflexivity enables “unveiling [of] the unknown mechanisms of the established order, of symbolic violence and by sharing this knowledge in a reflexive and political alliance with the dominated—the ‘downtrodden’—as a form of counter-power” (Deer, 2014, p. 203). In their critiques, feminist scholars unveil the symbolic violence of Bourdieu's social theory with respect to his consideration of women (Lovell, 2000; Adkins, 2004).

Nevertheless, a number of key concepts enable us to consider how the social order is reproduced by, and reproduces habitus as embodied “systems of durable and transposable dispositions” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 72) that conform to the dominant social order i.e., playing by the rules of the game from a particular position in any given field. The hysteresis effect results when there is a mismatch between habitus and the field so that “practices are always liable to incur negative sanctions when the environment with which they are actually confronted is too distant from that to which they are objectively fitted” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 78). It is “one of the foundations of the structural lag between opportunities and dispositions to grasp them which is the cause of missed opportunities” (op. cit., p. 83). The hysteresis effect might be weakened when “enlightened self-interest” enables the adjustment of dispositions in crossing boundaries (Bourdieu, 2001, p. 37), for example, in women's achievement of leadership roles or recognition of their scholarship.

Whilst Bourdieu (2001) recognises some changes to women's conditions respecting educational, reproductive and employment rights brought about by feminism, he argues there is permanence in the masculine domination of women. Only if political action takes into account “all the effects of domination” (added emphasis), perhaps as they are also “raced” and “classed,” might it lead to the “progressive withering” of masculine domination (Bourdieu, 2001, p. 117). The male/female, masculine/feminine dualisms must be further complicated by the intersections of a range of social inequalities. Oppression constitutes actual physical and symbolic violence experienced by women in families, communities, the education, and political systems, workplace, and wider society, as sex discrimination, sexual harassment, sexual violence, the countless everyday slights by individuals and women's continued underrepresentation in positions of power depending on women's various positions (Moi, 1991). The reflexive social scientist and feminist activist might disrupt the violence of masculine domination by challenging the arbitrariness of misrecognised justifications for the established social order, many of which still largely go unchallenged. Focusing on such disruptions reveals the nature and extent of hysteresis and symbolic violence experienced in acquiring dispositions associated with, for example, a cleft habitus.

Despite the reservations I share with feminist scholars, I see in Bourdieu's (2001) theorisation a glimpse of hope for a more socially just society in the possibility of political action, including in education, based on an understanding of intersecting oppressions; and the development of a cleft habitus described as “a very strong discrepancy between high academic consecration and low social origin, in other words a cleft habitus, inhabited by tensions and contradictions” (Bourdieu, 2007, p. 100). Bourdieu's key concepts are useful thinking tools in theorising about gender, race, and class in educational leadership (Fuller, 2013, 2018).

Method—A Critical Autoethnography

Undertaking a critical autoethnography was prompted by two research projects about the intersection of race, gender, and class in headship (Moorosi et al., 2017, 2018; Torrance et al., 2017). Similarities between our stories resulted from a researcher's desire to become closer to research participants (Pillow, 2003). There was complacency in identifying with participants' experiences, recalling: dislike of food, solo international travel, racist television programmes in the 1970s. To go deeper, I needed to engage with discomforting reflexivities focused on differences. To impose order on a necessarily messy reflexive narrative I developed a chronological qualitative life grid to capture and analyse reflexivities as they surfaced. I use data from my life narrative situated in specific sociocultural contexts (Chang, 2008; Boylorn and Orbe, 2014).

The “7 Up” Intersectionality Life Grid

The “7 Up” intersectionality life grid is a heuristic device for reflection on a life in education as learner, educator, leader, and scholar from birth to 56 years (1962–2018). It focuses primarily on the intersections of gender, class, and race. However, an intersectional analysis is not limited to those social categories; arguably other intersecting social category factors such as age, religion, and sexual orientation may become apparent or be specifically highlighted in such an analysis. It is a qualitative life grid designed to enable analysis of education policy impact over time and “insight into the relationship between the macro, meso, and micro levels for case-based approaches” to research (Abbas et al., 2013, p. 320). It synthesises multilevel perspectives as societal (macro), systemic (meso), organisational and personal (micro). Such an approach produces dense narrative data (Abbas et al., 2013) requiring clear guidelines about what to include. Imposing a 7 yearly timescale is not wholly arbitrary. A UK television series charting the lives of 14 children from the age of seven in 1963, at 7 year intervals, recently reached 63 Up (see also Granada Television, 1999; ITV, 2019). Participants reflected on their lives and previous eight programmes. Some have withdrawn from the project. The inclusion of only four girls/women, all of whom were white, reveals the extent of intersecting biases inherent in social research in the 1960s (Fuller, 2014a), as do the questions asked, answered, or resisted on camera about gender relations.

The “7 Up” intersectionality life grid provided a framework in which to record reflections relating to learning from birth (birth−1962) through primary (7−1969), and secondary (14−1976) to tertiary (21−1983, 28−1990, 35−1997, 42−2004) education; educating and leading in secondary (35−1997, 42−2004, 49−2011) and higher education (49−2011, 56−2018) and researching (35−1997, 42−2004, 49−2011, 56−2018), in the context of unequal gender, class, and race relations in UK society. The focus on particular years led to thinking about those immediately preceding or following as the limitations became clear regarding what might be omitted. For example, the grid misses 2 years' attendance at a progressive middle school during the 1970s (aged 11–13) and the experience of physical abuse i.e., I was hit round the head by a teacher. Where I have included a reflection from outside a particular age/year I use circa (c) to indicate the approximate and/or closest age (e.g., c14).

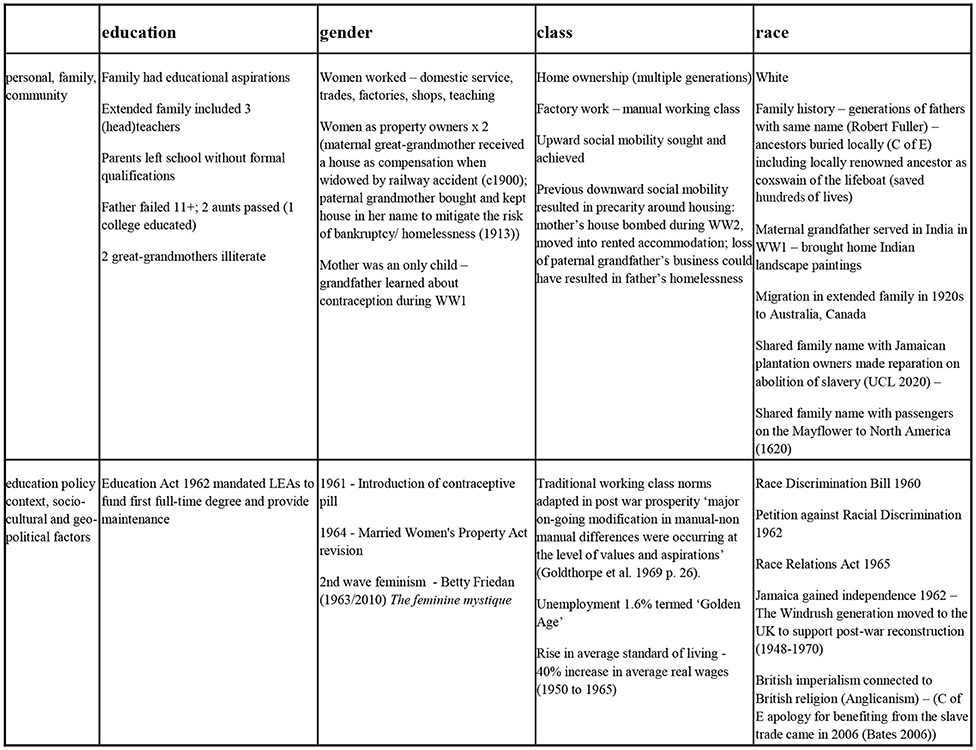

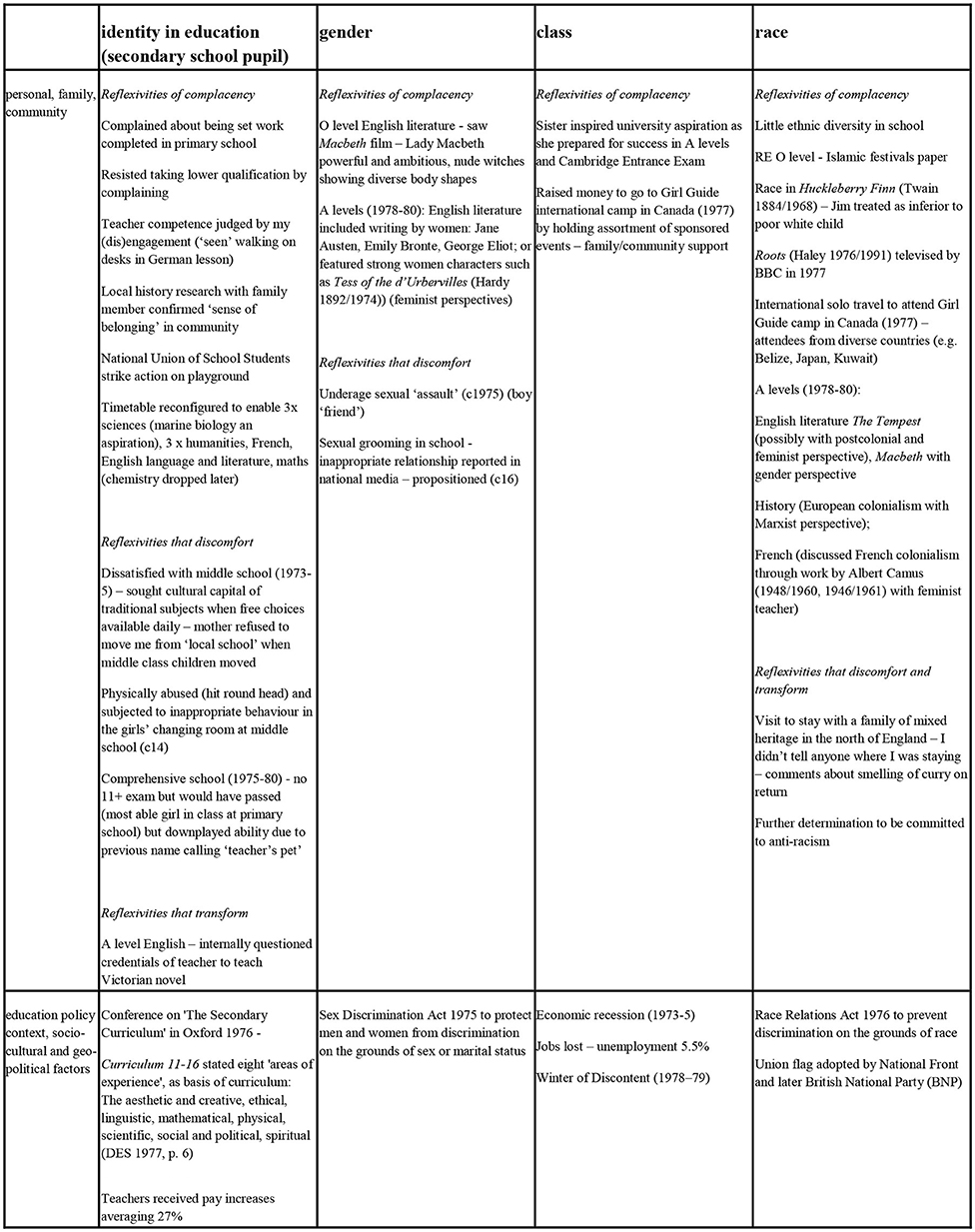

The “7 Up” intersectionality life grid evolved into nine grids (one per age—year: see Figures 1, 2 as examples) each containing: four columns associated with identity labelled: education, gender, class, race; and two rows as “personal, family, community” (micro level factors) and “education policy context, socio-cultural, and geo-political factors” (macro level factors). Cells were populated with notes from memory and desk research. Questions that guided reflections about my positionality in the social field (family, community, education, workplace), the development of dispositions resulting in a scholarly (cleft) habitus and my position-taking with respect to gender and feminist scholarship in educational leadership are provided as Appendix 1. They are adapted from questions asked of headteachers in a range of research projects focused on gender, identity, and educational leadership (Fuller, 2013; Moorosi et al., 2017; Torrance et al., 2017).

Figure 2. Example of ‘7 up’ intersectionality life grid (14−1976) showing reflexivities of complacency, reflexivities that discomfort and reflexivities that transform.

Subsequent autobiographical writing revealed contrasting reflexivities. Reflexivities accounting for and confirming a pre-existing self-narrative identifying with feminism, upward social mobility, antiracism, and social activism are called reflexivities of complacency. Painful recollections of gender-related oppressions and achieving social mobility are identified as reflexivities that discomfort; and recognising complicity with white supremacy, accruing white privilege and my own white fragility, whilst these are reflexivities of discomfort (Pillow, 2003) they are also reflexivities that transform. They are mapped against education policy context, socio-cultural, and geo-political factors. Their appearance in the same time frame reveals the simultaneity of a commitment to antiracism alongside the limitations of its enactment.

In the sections that follow I recount reflexivities of complacency, reflexivities that discomfort and reflexivities that transform found in the “personal, family, community row” of the “7 Up” life grids relating to intersecting identities as learner in publicly funded education including at a Russell Group university (birth, 7, 14, 21); leader outside education about to enter teaching (28); and learner-educator-leader-researcher (c28 onward) having taught and led as English teacher, head of English, deputy headteacher, and school governor in five mixed comprehensive schools (35, 42, 49); initial teacher educator (49); associate professor of educational leadership (56) leading postgraduate courses, including an educational leadership and management programme (56), and research projects at Russell Group universities.

This study has the ethical approval of my institution. There are inherent challenges and “risks” of such an autoethnography such as the potential re-identification of individuals as family members, teachers, classmates and colleagues and institutions (see Sikes, 2010 for further discussion of researchers' concerns in life history and autobiographical work). The individuals I have identified by my relationship or name have given informed written consent for their participation. Indeed, conversations with my sister, Lynn, about this project enhance its trustworthiness. I believe our teachers thought we shared similar dispositions for higher education and we were each tutored by our comprehensive school teachers in extra-curricular classes for the Cambridge Entrance Examination. The women who participated in the research projects that inspired this autoethnography each gave informed consent to the use of their words in my writing. I refer to institutions in general terms though readers might be able to discover the schools and universities I have attended and worked in. I have withheld my age when the re-identification of an individual or institution might be undesirable. However, it remains the case that individuals might recognise themselves (Sikes, 2010). I am particularly mindful of becoming the story I write (Ellis, 2009). That has led to some omissions about my private life; though at times I have chosen to be open.

Findings

The findings are reported as three categories of reflexivity: reflexivities of complacency; reflexivities that discomfort; and reflexivities that transform.

Reflexivities of Complacency

Reflexivities of complacency confirm a self-narrative and identity as feminist (e.g., experiencing, recovering from and confronting a range of gender related oppressions [see below (14 onward)], upwardly socially mobile [e.g., moving from manual working-class to educated middle-class (21), into a profession (c28, 35 onward)], anti-racist [e.g., calling out (c7), teaching (c28 onward), and researching about racism (49 onward)] and social activist [e.g., campaigning for human rights (c21 onward), supporting professional activism about women's careers in education (c49 onward)]. They relate to learning [e.g., comparative religion (14), socialist/Marxist perspectives on history (c14), sociology (c14), feminist and post-colonial literature/feminist and postcolonial readings of literature (c14, 21), education studies that explored anti-racism and Islamophobia (c28, 35), critical leadership studies (c42)], and teaching [e.g., feminist and post-colonial curriculum content (c28 onward) and critical pedagogy (c28 onward)], leadership, management, and organisation with social justice in mind (35 onward), and educational leadership scholarship with a feminist (c42 onward) and intersectional lens (49 onward).

Having described my students' open challenge to me about my white privilege as an example of enabling critical dialogue in the classroom, Victoria Showunmi reminded me “we must not be complacent Kay” (56) (personal telephone conversation). Her comment led to this framing of reflexivities of complacency. In the section that follows I recount reflexivities that discomfort relating to gender and class.

Reflexivities That Discomfort

Recollecting gender and class related oppressions of exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence (Young, 2004) such as sexual grooming (c14), sexual assault (c14), acquaintance rape (21), and sexual harassment in the workplace (35, c42); gender barriers in the workplace such as underrepresentation in senior posts (28) and sex discrimination (c42) have been painful. Those relating to violation of the person are deeply misogynist, cause long-lasting damage and take decades to heal. Everyday sexism in the workplace such as comments on clothing and make-up (28, 35, c42), conversation colonisation, silencing in meetings (c49, 56) sex discrimination in the selection process (21, c42) along with the gender pay gap (49) are symptomatic of the symbolic violence of persistent patriarchal structures resulting in women's exploitation and marginalisation.

Behaviours leading to marginalisation based on social class at a Russell Group university included questions about schooling, comments about accent, disparaging misidentification as “northern,” and “self”-segregation in dining halls (c21). My confidence waned. I was silent in class and stopped attending altogether in my final year (21). By graduation, the thought of teaching, taking a further degree or working in higher education filled me with terror.

A career path of “snakes and ladders” respecting status and salary (Fuller, 2017b) meant moving from: temporary cleaning, care, and shop work as a teenager (c14), catering, factory, and pub work as a student (c21) to full-time managerial work including clerical, cashiering, and catering (21, 28) and hitting a glass ceiling in retail management (28). All are occupations in which women are concentrated (Trade Unions Congress, 2012) though men held senior management posts (see e.g., Brandwood et al., 2008). Teaching (c28) and school leadership (35, 42) simultaneously meant the social mobility of entering the professions and a symbolic return to the community (Reay, 2017) by teaching and leading in five mixed comprehensive schools dominated by white working-class children (c28, 35, 42, 49) albeit in a region with the greatest ethnic diversity outside London. Nearing the completion of a doctorate, I doubted I had the intellectual capacity to become an academic (c42). The residues of being an interloper remained (Johansson and Jones, 2019). The eventual transition to higher education meant losing market value (c42) that took 14 years to restore (56) [in real terms there remains a £10 K per annum deficit without assuming I might have secured further promotions in the meantime (c56)].

Though discomforting, these reflexivities are ones I have long come to terms with. They fire the “passionate partiality” (Reay, 2017, p. 2) associated with an interest in gender and class in educational leadership. It is the reflexivities that discomfort associated with recognising the place of whiteness in my trajectory that have the power to transform a self-narrative, to construct relationships and do research differently.

Reflexivities That Transform

Each account is framed by a quotation from a woman of Black and Global majority heritage interviewed about the intersection of race, gender, and class in headship (Moorosi et al., 2017, 2018; Torrance et al., 2017). This serves to illustrate moments when their voices disrupted my reflection and self-narrative. They also focus the narrative on differences in an attempt to do the impossible i.e., to de-centre whiteness whilst simultaneously acknowledging it. In addition to providing examples relating to learning and teaching (curriculum content and pedagogy), leadership, management and organization, and scholarship, I share reflexivities relating to socialisation, politicisation, and colonialism.

Learning and Teaching—Curriculum Content and Pedagogy

“I remember seeing something about Nelson Mandela on the TV and him being released. And then I'd learnt this word Apartheid and I thought that was a really amazing word and […] Badgered [my teacher] to let me teach her year two class for just a section of the lesson [laughter]” (Nicola describing an experience of teaching aged ten or eleven) (see Moorosi et al., 2017, 2018).

Despite my awareness of, and calling out racism among family members (c7, 21 onward), I briefly internally questioned the credentials of two teachers to teach English literature i.e., the Victorian novel and revenge tragedy, because of their ethnic identities (c14, c21) (Lander and Santoro, 2017).

Despite study of post-colonial literature and an anti-racist initial and continuing teacher education (c28, 35), I was ill-equipped, early in my career, to teach children about race when opportunities arose. Whilst teaching The Tempest, I asked pairs of children to depict roles of “master” and “slave” i.e., Prospero and Caliban. A white child enacted “master” and a child of Black African heritage enacted “slave.” My racialized construction of their identities racialized the power dynamics of the play in what might become a postcolonial understanding. However, I failed to control my visceral response of panic to enable discussion about the power of the tableau. I was unable to facilitate race dialogue without explicitly racializing individual children. This paternalistic response, an indicator of white fragility, resulted in missing an opportunity to engage children in a critical race dialogue (Borsheim-Black, 2015).

Leadership, Management, and Organisation

“‘We do think it's an issue but it's an issue for you’ [her emphasis]. [Laughs]. So they didn't recognise. I found that really upsetting [audibly emotional]” (Saeeda in Fuller, 2018, no page).

Despite an espoused commitment to anti-racism and my knowledge of the McPherson Report (McPherson, 1999) that outlined institutional racism (c35), I failed to see a Black African male colleague in a public space (age withheld) (Fuller, 2017a). I wholly underestimated the impact of invisibility on his mental and physical health (Chakrabarty, 2012). The inadequacy of my response to a colleague of African heritage explaining her experience of working in a predominantly white institution provides another example of white fragility (age withheld) (DiAngelo, 2018). I failed to negotiate and reconcile the stated grievances of white colleagues, the unsurprising emotionality of my Black colleague suffering the consequences of racism, and a selfish concern for my professional reputation in not wanting to be thought racist. I listened but my responses were derisory (age withheld).

Scholarship

‘They're the worst! Absolutely. I can't stand academics’ [laughs] (Annette).

Kay: ‘I could be criticised for this work [researching the experiences of women headteachers of BGM heritages as a white scholar] […], but I feel I have to take that risk.

Nicola: Yeah. Exactly.

Kay: And I have to include people in my work.

Nicola: Absolutely. Because otherwise that story would never be told.

Kay: No. That's right.

Nicola: And you can't risk that. That's a far more dangerous risk.’

Although, my professional teaching and school leadership practice taught me to recognise girls and boys were not homogenous groups, I first approached gender scholarship as if women and men were (c42). I did not ask survey respondents about ethnicity or religion (Fuller, 2009). One woman forced open a space to comment on the barriers to her progression as a headteacher, newly arrived from Kenya, of an independent school for Muslim girls (previously unpublished survey data).

Subsequently, headteachers of colour participated in the qualitative research; both men, one led an Islamic faith school (Fuller, 2013). I have been challenged at academic conferences about not including women from diverse heritages (49). More recently, the challenge has been about whether and how white scholars should research race (Rollock and Gillborn, 2011; Rollock, 2013).

Socialisation

‘My father came to this country in the fifties. My mum joined in 1971 at which point I was a little baby’ (Hasna).

I was socialised into the dominant culture of whiteness never questioning my racial identity (DiAngelo, 2018). Generations of my father's family attended the established Church of England. My sense of belonging begins with a graveyard full of ancestors and being at the centre of a rich local history researched in primary and further valued at secondary school [c7, 14 (see Butcher, 1979)].

I learned to be silent about race and racism witnessed among family members describing a sari-wearing woman as “sunburnt” (c7) (DiAngelo, 2018). I corrected them saying she was Indian; I genuinely thought they did not know. I was confused by the dissonance between Christianity and church-goers engaging in racist talk (Fuller, 2017a). This critical awareness resulted in not revealing I was going to stay with a mixed heritage family (Pakistani-English) (14). On my return, comments were made about smelling of curry. More recent examples of racism in the family include name calling (c49) and comments about unfamiliar names and headwear (c56). In adulthood I always call such comments out.

Politicisation

‘I call myself black, I mean politically black, but also just black’ (Annette)

‘I remember my secondary school being closed down one day because the BNP (British National Party) were going to march through’ (Nicola).

Despite, awareness of the Rock against Racism movement (14, 21); disgust at the National Front's appropriation of the Union flag; and campaigning against apartheid (21) (Fuller, 2017a), I failed to call out persistent racist name-calling (age withheld) (Fuller, 2017a). I misinterpreted the response of laughter (Houshmand et al., 2019) constructing it as acceptance or indifference. This repeated in the workplace (age withheld) when one workmate called another her “sun-kissed friend;” once more I was silent (DiAngelo, 2018). Further examples of ignoring and/or perpetuating microaggressions of everyday racism included the Anglicisation of South Asian first names, blindness to the cultural diversity of the workforce in a multi-ethnic city and the dominance of whiteness among social groups (c28). I had become colour blind instead of recognising and valuing difference (DiAngelo, 2018).

Colonialism

‘My dad had lived here obviously with other single men because our country was a British colony at the time’ (Hasna).

At the London Schools and the Black Child Conference in 2014, a Black woman, sharing my family name, called me “sister.” Her recognition of me prompted historical research revealing settlers, colonisers, and slave-owners among our namesakes. Family members settled in Canada and Australia in the 1920s (c14, c56). Our namesakes, born 20 miles from my birthplace, boarded the Mayflower bound for the “New World” in 1620.

The Legacies of British Slave-ownership archives (University College London, 2020) show our namesakes benefited from slave ownership including when reparations were paid on the emancipation of slaves (e.g., Mary Ann Fuller). One Jamaican plantation and slave owner (Henry Fuller) willed manumission for Princess, the “Negro” mother of Fanny a “free ‘Negro’ woman,” leaving an annuity to each. The inheritance of emancipation by Princess and property by Fanny and Henry's two children, described in racialized terms as “mulatto,” suggests a sense of responsibility but not necessarily affection or sexual consent from Fanny. The brutality of enslavement largely goes unnamed, unrecorded and unrecognised. It must be read between the lines.

Historically, then, our family namesakes include powerful Cambridge educated [e.g., Charles Beckford Fuller (1739–1825)] wealthy men [e.g., Augustus Elliott Fuller (1777–1857)] in politics [e.g., Henry Fuller Attorney General of Trinidad; John “Mad Jack” Fuller MP (1757–1834) heir to the Jamaican fortune of Rose Fuller MP (1708–1777)], the military [e.g., Frederick Hervey Fuller (1786–1865)] and as Jamaican planters and merchants (e.g., John Fuller; Stephen Fuller) who lobbied to manipulate the price of sugar post abolition (1807–1815) (Ryden, 2012). They embodied the power structures of white supremacy at the height of British colonialism and slavery.

Below, I discuss a transformed self-narrative from a discourse of social mobility to one of complicity with white supremacy, accrual of white privilege and enactment of white fragility.

A Transformed Self-Narrative: Seeing Myself as Another Might See Me

Women of Black and Global Majority heritages held up mirrors to distort my reflection. Their words, and the subsequent critical autoethnographic work, resulted in the reconstruction of a self-narrative that refreshes my worldview and renews my critically reflexive stance (see Boylorn and Orbe, 2014). The process ensured the feminist standpoint beginning with accounts by marginalised groups “go[es] beyond experience to an understanding of meaning” (Shakeshaft, 2015, p. xvii) to consider the functioning of hierarchical social and organisational structures (Harding, 2004).

Complicity with white supremacy, the accrual of white privilege and enactment of white fragility have each been exposed by examining the misrecognised narrative of upward social mobility (Reay, 2017), and the experiences of hysteresis and symbolic violence associated with gender and class, but not, for me, with race. It is necessary to discuss these at multiple levels as historical, systemic, institutional and individual.

Complicity With White Supremacy: The Enduring Impact of Slavery and Colonialism

Powerful descriptions of individual and collective diaspora directly recount or imply the enduring impact of the historical structures of slavery and colonialism (Moorosi et al., 2017). Recognising the painful legacy of slavery does not necessarily result in apology [see e.g., apology by the Church of England (Bates, 2006) and refusal to apologise by David Cameron (Dunkley, 2015)] or reparation [see e.g., by the University of Glasgow (Carrell, 2019)].

Regardless of whether or not I am directly related to slave-traders, slave-owners, colonisers, and settlers, I benefit directly and disproportionately from the nation's creation of wealth based on the historical enslavement of human beings and the exploitation of resources throughout the British Empire; its actual and symbolic capital. Wealth creation enabled a welfare state that afforded me free access to education, healthcare, unemployment, and other benefits (birth onward) (albeit these have been depleted in recent years Reay, 2017). Tomlinson (2019) argues there remains collective ignorance about this in the UK because it is not taught in schools.

Complicity With White Supremacy: Social and Education Policy

Social policy influenced by liberal feminism, enacted as sex equality legislation [Equal Pay (1970) (c7), Sex Discrimination (1975) (c14), and Equality Acts (2010) (c49)] worked in my favour alongside liberal education policy designed to provide access to higher education for the working-class [e.g., the Education Act (1962) mandated Local Education Authorities to fund a first full-time degree and provide a maintenance grant (birth) that almost quadrupled in 1980 when I went to university (c21)]. Other legislative measures supported my access to higher education including Circular 10/65 (1965) laying out plans for comprehensive (non-selective) education (c7); raising the school leaving age in 1972 (c7); and the articulation of a broad and balanced curriculum (DES, 1977) (c14).

This taken-for-granted entitlement to higher education, despite experience of the hysteresis effect and an unsafe sexual environment, belies the lack of access for people of minority ethnic heritages (Bhopal, 2018) (c21). It is a clear indicator of the accrual of benefits from my white privilege as symbolic capital.

The Accrual of Benefits From White Privilege

An unquestioned sense of belonging [to the dominant culture—a white working-class family committed to girls' education, women's independence and membership of the established church (birth onward)]—and entitlement to education [speaking back to teachers who: listened, enabled access to higher status qualifications (O levels), redesigned the timetable to accommodate science/humanities interests, supported access to a Russell Group university (14)] resulted in early accrual of the benefits of white privilege.

At the same time, Black children were isolated in communities and schools, confronting the hysteresis effect and the actual and symbolic violence of being systematically categorised as educationally sub-normal (Coard, 1971) (c7). Their linguistic resources were underestimated by teachers (Fuller, 2013, 2018). By contrast, encouraged to aim high, my sister, Lynn, and I applied to Cambridge (she succeeded, I failed). Access to and success in elite higher education institutions [e.g., attending and working in Russell group universities (c21 onward)], and access to continued professional development [e.g., the Aurora programme provided by the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (c49)] continues to positively influence my trajectory [see Bhopal (2018) for a discussion of the disproportionate benefit of the Athena Swan programme for white women scholars]. I have largely overcome the hysteresis effect felt earlier (c21).

Enactment of White Fragility

At a personal level, I have recounted examples of white fragility. DiAngelo (2018) argues white people's engagement with race dialogue is best seen on a continuum depending on context and circumstances. That may be so. What remains troubling is the dissonance between the espousal of social justice values of equality, equity, diversity, and inclusion (14 onward) (Fuller, 2017a, 2019) and the extent and persistence of ignorance, blindness, insensitivity, disengagement, and inadequacy in practice (c21 onward). Arguably, that can be explained as adherence to the dominant white social order, but there is evidence of attempting to understand and disrupt that from an early age (c7), resulting in being silenced (14), and the gradual restoration of an openly anti-racist stance (c28 onward). It is no surprise that the most powerful societal and institutional influences to conform were felt during childhood, during my experience of the hysteresis effect at university and during a career in a capitalist enterprise focused on features of women's subordination (managing departments associated with the domestic world—baby-wear, haberdashery; and appearance—fashion and cosmetics) (21, c28). Resistance of those forces was enhanced by a progressive, critical education (c14 onward), a career transition into education (c28 onward) and scholarship in gender and educational leadership with an increasingly intersectional perspective (c42 onward).

As a result of this study, I am forced to recognize my trajectory has been influenced by the coincidence and conspiracy of white supremacy in the English education system (Gillborn, 2008), and the accrual of white privileges (Bhopal, 2018); not by my own merit nor as some sort of miracle (Reay, 2017). In the sense that historical structures, social, and education policy, organizational priorities and family dispositions coincided, they conspired to do me “good,” whilst simultaneously conspiring to disadvantage children, teachers, leaders, and scholars of colour who are likely to have experienced the hysteresis effect of their intersecting identities relating to race, gender, and class as they navigated the actual and symbolic violence of “whiteworld” (Gillborn, 2006).

So What?—Thinking About Intersectionality

Pontso Moorosi's response to an early presentation of this work was to ask “so what?” (Berry and Fuller, 2019). It was never the intention to indulge in a narcissistic process of confession (Pillow, 2003). Acknowledgment of white privilege might be welcomed, but in itself is insufficient (Ignatiev, 1997; Ahmed, 2004). Here, I argue for the usefulness and importance of the “7 Up” intersectionality life grid as a tool for critically reflexive teaching, leadership and scholarship across phases, sectors, and national contexts. I suggest critical reflexive intersectional work, with its potential for transforming self-narratives and therefore feminist standpoints, is an essential component in a feminist epistemology.

Critically Reflexive Teaching and Leadership

Immediately following the conference presentation, a private comment was made about never before considering the extent of white privilege. The “7 Up” intersectionality life grid can be used as a pedagogical tool for professional reflexivity, in the writing of cultural or critical autobiographies that help students, teachers, and leaders in the ongoing development of critical consciousness in preparation for culturally responsive learning, pedagogy, and leadership for social justice (Sleeter, 2001; Capper et al., 2006; Tintiangco-Cubales et al., 2015). It has potential to identify funds of knowledge and identity useful in the learning and teaching process (Wrigley et al., 2012; Esteban-Guitart and Moll, 2014).

That means charting and distinguishing between reflexivities of complacence, reflexivities that discomfort to reach reflexivities that transform with respect to a hitherto less or unconsidered aspect of identity for those who usually identify with the mainstream e.g., as white, heterosexual, able-bodied, and/or male. A specific focus on religion might be particularly helpful though my awareness of religious difference was linked to racial difference and developed in church and school [e.g., understanding my identity as a Gentile through the parable of the Good Samaritan (7); learning about Islamic festivals, female circumcision (c14)]. The accompanying intellectual work that focuses on the underlying arbitrariness of social practice in our upbringing, education, the workplace, and wider society, with a socio-historical and geopolitical perspective, might surface the context and circumstances of the hysteresis effect, if and when it was experienced, as well as the nature and extent of actual physical and/or symbolic violence. This paper acts as an example of such critical self-work.

Increased consciousness has the potential to facilitate the adjustment of dispositions in order to benefit from opportunities as positions change in a given field or there is movement into a new field, difficult though that might sometimes be. A nuanced understanding of the hysteresis effect that negatively influences an individual's trajectory might be gained through reflexivity. That might benefit learners, educators, and leaders to make sense of their own trajectories and lead to more inclusive practice for the benefit of others.

Critically Reflexive Scholarship

Epistemological and ontological perspectives influence the scholar's methodological choices as well as their critical engagement with research data. The “7 Up” intersectionality life grid provides a methodological tool for scholars to engage in critical reflexive practice to enhance their understanding and articulation of positionality and position-taking in their particular field. For white scholars, in particular, the focus on race could enhance an understanding of the power of white supremacy, white privilege and the ubiquity of white fragility in the education system. Such understandings might facilitate and enrich cross-cultural research in a number of contexts.

Benefits for research participants involved in research have been framed as opportunities to reflect on practice and thereby further develop a conscience for social justice (Torrance et al., 2017). This autoethnography made clear there are benefits for scholars having their identities reflected back to them, and distorted, by research participants. For example, the accrual of white privilege was highlighted through women's descriptions of diaspora and unbelonging (Maylor, 1995), white fragilities in accounts of white women leaders' denial of institutional racism (Fuller, 2018), and white supremacy in comparatively easy access to higher education. Pinpointing the hysteresis effect and ways individuals negotiate it is fertile ground for future research that might support learning and the achievement of leadership by diverse groups.

Transforming a Feminist Standpoint

It is the “7 Up” intersectionality life grid's potential for transforming a self-narrative that makes this contribution to feminist ways of seeing women's leadership important. Critically reflexive writing necessarily involves scholars writing themselves into their work. The declaration, “I am a single, White, middle-class woman working in higher education. I construct my family origins as manual working class” (Fuller, 2013, p. 16) rarely gets further explanation as a statement of positionality. It has been fixed by the act of writing. The reality is that identity constructions shift depending on context, circumstances and relationships. Whilst none of the statements above has changed, my understanding of what they mean has.

How feminist scholars articulate the fluidity of their standpoint has been addressed, at least in part, here. I have recognised and begun to articulate intellectual struggles with gender, feminist, and social theories and my position-taking in the field of women and gender in educational leadership (see also Fuller, 2013, 2014b). This research has re-affirmed my position that gender is simultaneously a relational, performed and conferred identity (Adkins, 2004) that necessarily intersects with identity factors such as “race,” social class, religion, sexual orientation, nationality as well as learner, educator, leader, and scholar identities. For me, the conferred identity of girl/woman has resulted in some experience of oppression (Moi, 1991); the performed identity that draws on privileges associated with whiteness has recovered from and resisted some of those oppressions. Feminist scholarship is political. It focuses on social justice. Starting with our own experiences and trajectories we can “study up” to discover the hierarchies and structures of patriarchy, capitalism and postcolonialism that need to be dismantled (Harding, 2004, p. 31).

Having reconstructed my self-narrative, refreshed my worldview and renewed my critically reflexive stance, I am much more likely to foreground white privilege than social mobility in future descriptions of my positionality. Acquiring a fuller understanding of, and declaring white privilege cannot be seen as making reparation for and abolishing it (Ignatiev, 1997; Ahmed, 2004). But collectively, through activism and education, we might turn such very small steps into a march toward that goal.

Postscript

At the time of writing, in the midst of the Covid 19 pandemic (2020), we are locked down globally. A reviewer of this paper wished me well-being in “these precarious times.” It is impossible to say what the long-term effects of this crisis will be for individuals, groups, organisations, communities, and society. I cannot envisage what 63 Up will be for me in the way I might just a few months ago. We are already able to recognise inequalities in how it is being experienced based on ‘race’, age, underlying physical health conditions, mental health, housing, and access to green spaces, access to technology, employment in health and social care and other essential services, employment in non-essential services (being furloughed or made redundant), and location in developed and developing nations.

Whilst we might all be in this together, we are not in it together equally. Educating and leading for social justice persists as a global challenge.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available. The material is of a sensitive nature and is kept private. Two examples are provided in the text as Figures 1, 2.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by School of Education, University of Nottingham. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

KF is the sole author and investigator in this research.

Funding

The intellectual work for this project was supported by the University of Nottingham, UK.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to students, teachers, leaders, and scholars of colour for continuing to talk about race. The comments of reviewers and my colleague Professor Pat Thomson on an earlier draft of this paper have enabled me to strengthen it further.

References

Abbas, A., Ashwin, P., and McLean, M. (2013). Qualitative Life-grids: a proposed method for comparative European educational research. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 12, 320–329. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2013.12.3.320

Adkins, L. (2004). Introduction: feminism, Bourdieu and after. Sociol. Rev. 52, 3–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00521.x

Ahmed, S. (2004). Declarations of whiteness: the non-performativity of anti-racism. Borderlands 3. Available online at: http://www.borderlands.net.au/vol3no2_2004/ahmed_declarations.htm

Ahmed, S. (2009). Embodying diversity: problems and paradoxes for Black feminists. Race Ethnicity Educ. 12, 41–52. doi: 10.1080/13613320802650931

Bates, S. (2006, February 9). Church apologises for benefiting from slave trade. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/feb/09/religion.world.

Berry, J., and Fuller, K. (2019, July 11). Ways of seeing women's leadership in education. [Paper presentation] at the Women Leading Education across Continents Conference (Nottingham).

Blackmore, J. (2010). ‘The other within’: race/gender disruptions to the professional learning of white educational leaders. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 13, 45–61. doi: 10.1080/13603120903242931

Blackmore, J. (2013). “Forever troubling: feminist theoretical work in education,” in Leaders in Gender and Education, eds M. Weaver -Hightower and C. Skelton (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 15–31.

Borsheim-Black, C. (2015). “It's pretty much white”: challenges and opportunities of an antiracist approach to literature instruction in a multilayered White context. Res. Teach. Eng. 49, 407–429. Available online at: www.jstor.org/stable/24398713

Boylorn, R. M., and Orbe, M. P., (eds.) (2014). Critical Autoethnography: Intersecting Cultural Identities in Everyday Life. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Brandwood, P. M., Woolnough, H. M., Hahlo, K., and Davidson, M. J. (2008). Career Development and Good Practice in the Retail Sector in England: A National Study to Investigate the Barriers to Women's Promotion to Senior Positions in Retail Management. Psychology: Reports. Paper 1. Available online at: http://ubir.bolton.ac.uk/371/digitalcommons.bolton.ac.uk/psych_reports/1

Capper, C., Theoharis, G., and Sebastian, J. (2006). Toward a framework for preparing leaders for social justice. J. Educ. Admin. 44, 209–224. doi: 10.1108/09578230610664814

Carrell, S. (2019, August 23). Glasgow University to pay £20m in slave trade reparations. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/aug/23/glasgow-university-slave-trade-reparations.

Chakrabarty, N. (2012). Buried alive: the psychoanalysis of racial absence in preparedness/education. Race Ethnicity Educ. 15, 43–63. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2012.638863

Coard, B. (1971). How the West Indian Child is made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain. London: Caribbean Education & Community Workers' Association.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge.

David, M. (2013). “A “mother” of feminist sociology of education?” in Leaders in Gender and Education, eds M. Weaver-Hightower and C. Skelton (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 43–60.

Deer, C. (2014). “Reflexivity,” in Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts, ed M. Grenfell (Abingdon: Routledge), 195–208.

Dunkley, E. (2015, September 30). David Cameron rules out slavery reparation during Jamaica visit. BBC News. Available online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-34401412.

Ellis, C. (2009). Revision: Autoethnographic Reflections on Life and Work. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

England, C. (2017, January 3). Donald Trump blamed for massive spike in Islamophobic hate crime. Independent. Available online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/donald-trump-blame-islamophobic-anti-muslim-ban-hatecrime-~numbers-southern-poverty-law-center-a7582846.html.

Esteban-Guitart, M., and Moll, L. C. (2014). Funds of Identity: a new concept based on the Funds of Knowledge approach. Cult. Psychol. 20, 31–48. doi: 10.1177/1354067X13515934

Fuller, K. (2009). Women secondary headteachers: alive and well in Birmingham at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Manage. Educ. 23, 19–31. doi: 10.1177/0892020608099078

Fuller, K. (2014a). Looking for the women in Baron and Taylor's (1969) educational administration and the social sciences. J. Educ. Admin. Hist. 46, 326–350. doi: 10.1080/00220620.2014.919903

Fuller, K. (2014b). Gendered educational leadership: beneath the monoglossic façade. Gender Educ. 26, 321–337. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2014.907393

Fuller, K. (2017a). “Assumptions and surprises: parallel and divergent social justice leadership narratives,” in A Global Perspective of Social Justice Leadership for School Principals, ed P. Angelle (Information Age Publishing), 87–109.

Fuller, K. (2017b, October 12). Women achieving against the odds. [Keynote presentation] Women in Education: Professional Women Conference Series (London: Westminster Briefing).

Fuller, K. (2018). New lands, new languages: navigating intersectionality in school leadership. Front. Educ. 3, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00025

Fuller, K. (2019). Lead the Change Series: Q & A With Kay Fuller. Issue 96. Available online at: http://www.aera.net/Portals/38/docs/SIGs/SIG155/96_%20Lead%20the%20Change_KF_July%202019.pdf

Gillborn, D. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. J. Educ. Policy 20, 485–505. doi: 10.1080/02680930500132346

Gillborn, D. (2006). Rethinking white supremacy: who counts in “WhiteWorld”. Ethnicities 6, 318–340. doi: 10.1177/1468796806068323

Gillborn, D. (2008). Coincidence or conspiracy? Whiteness, policy and the persistence of the black/white achievement gap. Educ. Rev. 60, 229–248. doi: 10.1080/00131910802195745

Goldthorpe, J., Lockwood, D., Bechhofer, F., and Platt, J. (1969). The Affluent Worker in the Class Structure. Cambridge University Press.

Grant, C. (2014). “Still I rise: an early-career African American female scholar's told truths on surviving academia,” in Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo?, ed W. S. Newcomb (Information Age Publishing), 87–116.

Harding, S. (1991). Whose Science? Whose Knowledge?: Thinking From Women's Lives. Cornell University Press.

Harding, S. (2004). A socially relevant philosophy of science? Resources from standpoint theory's controversiality. Hypatia 19, 25–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2004.tb01267.x

Houshmand, S., Spanierman, L. B., and De Stefano, J. (2019). “I have strong medicine, you see”: strategic responses to racial microaggressions. J. Counsel. Psychol. 66, 651–664. doi: 10.1037/cou0000372

Ignatiev, N. (1997, April 11–13). The point is not to interpret whiteness but to abolish it. [Presentation] “The Making and Unmaking of Whiteness” (University of California, Berkeley, CA). Available online at: https://genius.com/Noel-ignatiev-the-point-is-not-to-interpret-whiteness-but-to-abolish-it-annotated.

Isaac, D., and Hilsenrath, R. (2016). A Letter to all Political Parties in Westminster. EHRC. Available online at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/our-work/news/letter-all-political-parties-westminster (accessed March 11, 2020).

ITV (2019). 63 Up. Available online at: https://www.itv.com/presscentre/ep1week23/63

Jean-Marie, G. (2014). “Navigating unchartered territories in academe through mentoring networks,” in Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo? ed W. S. Newcomb (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 25–39.

Johansson, M., and Jones, S. (2019). Interlopers in class: a duoethnography of working-class women academics. Gender Work Organ. 26, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12398

Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). “Racialized epistemologies,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd Edn., eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 257–277.

Laible, J. (2003). “A loving epistemology: what I hold critical in my life, faith and profession,” in Reconsidering Feminist Research in Educational Leadership, eds M. D. Young and L. Skrla (SUNY Press), 179–192.

Lander, V., and Santoro, N. (2017). Invisible and hypervisible academics: the experiences of Black and minority ethnic teacher educators. Teach. Higher Educ. 22, 1008–1021. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2017.1332029

Lovell, T. (2000). Thinking feminism with and against Bourdieu. Feminist Theory 1, 11–32. doi: 10.1177/14647000022229047

Lyman, L., Strachan, J., and Lazaridou, A. (2014). “Critical evocative portraiture: feminist pathways to social justice,” in International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Social (In)Justice, eds I. Bogotch and C. Shields (New York, NY: Springer International Handbooks of Education), 253–274.

Lyman, L., Strachan, J., and Lazaridou, A., (eds.) (2012). Shaping Social Justice Leadership. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Mansfield, K. C. (2014). “Reflections on perpetual liminality,” in Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo? ed W. S. Newcomb. (Information Age Publishing), 129–144.

Martinez, M. A. (2014). “My relationship with academia as a Latina scholar,” in Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo?, ed W. S. Newcomb (Information Age), 145–155.

May, T., and Perry, B. (2011). Social Research and Reflexivity: Content, Consequences and Context. London: Sage.

Maylor, U. (1995). “Identity, migration and education,” in Identity and Diversity: Gender and the Experience of Education, eds M. Blair, J. Holland, and S. Sheldon (Buckingham: The Open University Press), 39–50.

McIntosh, P. (1988). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (From Working Paper 189 “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women's Studies”). Available online at: https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/mcintosh.pdf

McPherson, W. (1999). The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/277111/4262.pdf

Mertz, N. (2009). Breaking Into the All-Male Club: Female Professors of Educational Administration. New York, NY: SUNY.

Moi, T. (1991). Appropriating Bourdieu: feminist theory and Pierre Bourdieu's sociology of culture. New Literary Hist. 22, 1017–1049. doi: 10.2307/469077

Moorosi, P., Fuller, K., and Reilly, E. (2017). “A comparative analysis of intersections of gender and race among black female school leaders in South Africa, United Kingdom and the United States,” in Cultures of Educational Leadership: Global and Intercultural Perspectives, ed P. Miller (London: Palgrave McMillan), 77–94.

Moorosi, P., Fuller, K., and Reilly, E. (2018). Leadership and intersectionality: constructions of successful leadership among Black women school principals in three different contexts. Manage. Educ. 32, 152–159. doi: 10.1177/0892020618791006

Newcomb, W. S., (ed.). (2014). Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo? Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Osanloo, A. F. (2014). The invisible other: ruminations on transcending “La Cerca” in academia,” in Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo? ed W. S. Newcomb (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 55–64.

Patai, D. (1994). “(Response) When method becomes power,” in Power and Method, ed A. Gitlen (New York, NY: Routledge), 61–73.

Peters, A. (2014). “Young, gifted, female and Black: the journey to becoming who I am,” in Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo? ed W. S. Newcomb (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 41–54.

Pillow, W. (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 16, 175–196. doi: 10.1080/0951839032000060635

Reay, D. (2004). “It's all becoming a habitus”: beyond the habitual use of habitus in educational research. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 25, 431–444. doi: 10.1080/0142569042000236934

Reay, D. (2017). Miseducation: Inequality, Education and the Working Classes. Bristol: Policy Press.

Rollock, N. (2013). A political investment: revisiting race and racism in the research process. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 34, 492–509. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2013.822617

Rollock, N., and Gillborn, D. (2011). Critical Race Theory (CRT). British Educational Research Association Online Resource. Available online at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/critical-race-theory-crt

Rollock, N., Gillborn, D., Vincent, C., and Ball, S. J. (2015). The Colour of Class. Abingdon: Routledge eBook.

Rusch, E., and Horsford, S. (2009). Changing hearts and minds: the quest for open talk about race in educational leadership. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 23, 302–313. doi: 10.1108/09513540910957408

Rusch, E., and Jackson, B. (2009). “A first woman with clout,” in Breaking Into the All -Male Club: Female Professors of Educational Administration, ed N. Mertz (New York, NY: SUNY), 13–26.

Ryden, D. B. (2012). Sugar, spirits, and fodder: the London West India interest and the glut of 1807–15. Atlantic Stud. 9, 41–64. doi: 10.1080/14788810.2012.636995

Santamaría, L. J., and Jaramillo, N. E. (2014). Comadres among us: the power of artists as informal mentors for women of color in Academe. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 22, 316–337. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2014.946281

Shakeshaft, C. (2015). “I'm not going to take this sitting down: the use and misuse of feminist standpoint theory in women's educational leadership research,” in Women Leading Education Across the Continents: Overcoming the Barriers, eds E. Reilly and Q. Bauer (Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield), xv–xviii.

Showunmi, V. (2018). “Interrupting whiteness: an autoethnography of a Black female leader in higher education,” in Women Leading Education Across the Continents: Finding and Harnessing the Joy in Leadership, eds R. McNae and E. Reilly (Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield), 128–136.

Sikes, P. (2010). “The ethics of writing life histories and narratives in educational research,” in Exploring, Learning, Identity and Power Through Life History and Narrative Research, eds A-M. Bathmaker and P. Harnett (Abingdon: Routledge), 11–24.

Sleeter, C. (2001). Preparing teachers for culturally diverse schools: research and the overwhelming presence of whiteness. J. Teach. Educ. 52, 94–106. doi: 10.1177/0022487101052002002

Smith, D. (1979). “A sociology for women,” in The Prism of Sex: Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, eds J. Sherman and E. Beck (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press), 135–188.

Tintiangco-Cubales, A., Kohli, R., Sacramento, J., Henning, N., Agarwal-Rangnath, R., and Sleeter, C. (2015). Toward an ethnic studies pedagogy: implications for K-12 schools from the research. Urban Rev. 47, 104–125. doi: 10.1007/s11256-014-0280-y

Torrance, D., Fuller, K., MacNae, R., Roofe, C., and Arshad, R. (2017). “A social justice perspective on women in educational leadership,” in Cultures of Educational Leadership: Global and Intercultural Perspectives, ed P. Miller (London: Palgrave McMillan), 25–52.

Trade Unions Congress (2012). Women's Pay and Employment Update: A Public/Private Sector Comparison. Available online at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/tucfiles/womenspay.pdf

Twain, M. (1968). Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. London: Pan Books (Original Work Published 1884).

University College London (2020, January). Legacies of British Slave-Ownership. UCL Department of History. Available online at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/.

Weaver-Hightower, M., and Skelton, C., (eds.) (2013). Leaders in Gender and Education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Welton, A. (2014). “Since she is gone, who will get me through?” in Continuing to Disrupt the Status Quo? ed W. S. Newcomb (Information Age Publishing), 177–192.

Wilkinson, J. (2008). Good intentions are not enough: a critical examination of diversity and educational leadership scholarship. J. Educ. Admin. Hist. 40, 101–112. doi: 10.1080/00220620802210855

Wrigley, T., Thomson, P., and Lingard, B. (2012). Changing Schools: Alternative Ways to Make a Difference. Abingdon: Routledge.

Young, I. M. (2004). “Five faces of oppression,” in Oppression, Privilege, and Resistance, eds L. Heldke and P. O'Connor (Boston, MA: McGraw Hill), 37–63.

Young, M. D., and Skrla, L., (eds.) (2003). Reconsidering Feminist Research in Educational Leadership. New York, NY: SUNY Press.

Appendix 1

Guiding questions for reflexive practice (adapted from Fuller, 2013) Think about

1. Your experiences of discrimination, those you have witnessed, those you have heard about in school, outside school, in the family, in wider society. How will you make sure you do not misrecognize the reasons for a colleague's thwarted ambitions or another colleague's success?

2. Your construction and performance of gender, those of your family, your colleagues as leaders, teachers and non-teaching staff. How are multiple femininities and masculinities enacted in the school and family?

3. Your personal values and their source, those of your colleagues, those of students and their families. How do you know whether your understandings match those of others? How will you open up dialogue to find out?

4. Your preconceptions about groups of people as new parents, Muslim women and men and working-class teachers. How will you ensure that you enable people to tell you about their particular desires, interests and needs?

5. Your understanding of equal opportunities. How might an equality discourse undermine the desires, interests, and needs of some groups and individuals in your school? Whose different desires, interests, and needs require a different approach?

6. Your teaching and leadership of teaching about gender, race, and class. How do you and others teach students to identify and deconstruct stereotypes?

7. Your relationships with families. How do you encourage parents to engage with school life? How do you welcome families into school? Do you visit students' homes and communities?

8. Your dialogue with students and families. How do you help students and families to understand the school and education systems? The curriculum choices they have? Their implication on students' future pathways?

9. Your understanding of racism. Is there an intercultural curriculum in place? How do you know? Do you know about students' cultural heritages? Do you know about students' linguistic resources? How do you monitor students' curriculum choices? Examination entries? Grouping arrangements? How do you record racist incidents? How do you teach about racism?

Keywords: intersectionality, feminist research, reflexivity, life grid, gender, ‘race’

Citation: Fuller K (2020) The “7 Up” Intersectionality Life Grid: A Tool for Reflexive Practice. Front. Educ. 5:77. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00077

Received: 30 January 2020; Accepted: 13 May 2020;

Published: 23 June 2020.

Edited by:

Lauri Johnson, Boston College, United StatesReviewed by:

Andrés Castro Samayoa, Boston College, United StatesCorinne Brion, University of Dayton, United States

Copyright © 2020 Fuller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kay Fuller, S2F5LkZ1bGxlckBub3R0aW5naGFtLmFjLnVr

Kay Fuller

Kay Fuller