- 1Department of Editorial, Universidad Estatal a Distancia, San José, Costa Rica

- 2Department of Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 3Department of Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Institute of Research in Education, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 4Faculty of Psychology, Institute of Neurosciences, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Teachers who present high emotional skills and knowledge of strategies to mediate the conflicts generated in the classroom, are able to exercise a better management of both the teaching tasks that correspond to them and to establish an emotionally nutritive and productive educational climate for the students. This research aims to study and analyze, under an integrative conceptual revision methodology, the theories and models that consider individual, group and social aspects of the origin, development and attention of conflicts, as well as emotional elements that underlie people’s behavior. All this within interpersonal relationships and in the different areas of action; in order to synthesize the results of each, establishing points of agreement and complementarity that serve to be adapted to the educational field. Educational mediation and emotional regulation are two constructs that have been previously studied separately, or in conjunction with others, but not in a complementary way between them. The presentation of these conceptual discussions suggests the formulation of new theoretical proposals, aimed at improving interpersonal relationships, the environment and dynamics of teaching–learning, focusing efforts on the teachers’ collective.

Introduction

The accelerated increase of conflicts and acts of violence in the educational field, the deep and lasting damages that these cause in the victims, both in their personal and academic development, and the way in which these situations must be handled, have become issues of interest and attention in many countries of the world, where a high percentage of secondary school students (90%) say they have witnessed cases of aggression (Filella et al., 2018). Teachers and other members of the educational community are negatively affected in their physical-emotional states causing work leaves due to stress, emotional exhaustion and serious health problems (Bush and Pope, 2008). These situations are frequent and increasingly shocking, associated with unpleasant emotions that result from aspects of their teaching functions (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2018, p. 1251).

To give attention to this problem, we propose the elaboration of a conceptual model aimed at the development of tools and resources for teachers, to improve the management of conflicts that arise in the context of the classroom. This model focuses on three constructs, conflict mediation, emotional regulation, and coping strategies.

The development of this study is based on empirical evidence, systematic reviews and meta-analysis of each of the elements that justify its use in the educational field, with the objective of contextualizing the current state of conflicts in education and analyzing other proposals that have been developed previously. From this literature review and the analysis of the gaps that previous models or programs have, we intend to justify the need to develop a conceptual model and point out the main contributions it makes to the field of education, considering the evidence that has shown that when the climate in the classroom is negative, it tends to generalize in the educational institution, making it more vulnerable to situations of violence and bullying (Wang et al., 2014).

The empirical findings (e.g., Ortega, 2006; Peña and Repetto, 2008; Pérez-Escoda et al., 2012; Miñaca-Laprida et al., 2013; Blair and Raver, 2015) have evidenced the positive impact that the implementation of programs aimed at the development of emotional skills has had on aspects such as the improvement of climate in schools and the prevention of aggressive manifestations among students.

Other empirical studies (Folger, 2008; Moral and Pérez, 2010; Carrasco et al., 2016; García-Raga et al., 2016, among others), have indicated that the use of conflict mediation in the educational field is perceived as very positive for teachers, students and directors, highlighting above all, its impact on conflict resolution and the prevention of serious and violent situations; it has also been highlighted the resistances that many educational institutions have to adopt this tool as part of their resources for the construction of a culture of institutional peace.

Finally, different investigations (Ruiz de Alegría et al., 2009; Castaño and León del Barco, 2010; Martínez et al., 2011; Limonero et al., 2012) have shown the close relationship that exists between coping strategies and the management of significant emotional situations for people, using variables such as age, type of conflict, high or low emotional intelligence and resilience, among others.

In this study we intend to show how these elements can be complemented to create a model that generates integral solutions for conflict management in educational centers, which represents an added value compared to other studies that have used them separately. The improvement in the development of teaching functions is directly manifested in high quality professional performance; therefore, it is important to work so that the teacher achieves a good state of health and a high level of subjective well-being, a factor that works as a protector against depression and exhaustion (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999).

This model can be contrasted with systematic review studies or descriptive non-experimental studies, where the systematic observation record is used, through which conflicts can be observed and recorded as they occur in their natural context, to be able to analyze and quantify them.

Central Constructs of the Integrated Circular Model of Conflict (ICMC)

This proposal integrates the constructs conflict mediation, emotional regulation and coping strategies under an Integrated Circular Model of Conflict (ICMC), whose particularity is to be able to feedback from the teachers’ own experiences, transforming their functions, from knowledge facilitators-transmitters to reflective-practical ones, who analyze everyday educational situations, making continuous adjustments to improve the teaching-learning process.

Conflict Mediation in the Educational Field

The mediation of conflicts implies the application of established principles and techniques aimed at resolving differences that arise between parties, without the need to apply sanctions or punitive measures, which have shown little to no effectiveness (Sánchez Ruiz, 2016).

The construct conflict mediation is addressed in this article from the Transformative Mediation Model, which suggests considering disputes and differences as opportunities for growth and achieving moral transformation (Bush and Folger, 1996). Transformative mediation includes recognition and appreciation not only conceptually, but as dynamic elements that can be used in a three-step mediation; to. “…(a) Concentrating efforts on exposing the conflict; (b) adopting conscious measures that encourage those involved to be active participants in the deliberation and decision of the conflict; (c) inviting, helping the parties to consider the other’s perspective” (Bush and Folger, 1996, p. 156).

There are abundant studies that have been conducted on conflict mediation in the field of education, whose ultimate goal is to establish a culture of peace in schools (Ramírez and Justicia, 2006; Monjas et al., 2008; Carrasco and Corral, 2009; Caballero, 2010; Medina Díaz, 2015; Sandoval and Garro-Gil, 2017; among many others). Caballero (2010) pointed out that, given the emergence of conflicting situations among students in schools, the use of mediation motivated the participation of families, which turned out to be a fundamental element to provide a prompt and satisfactory solution. In addition, he highlighted that improving the socio-emotional skills of students, becomes increasingly important, demonstrating its impact on personal, academic and work development, as well as its special impact on the prevention of antisocial behaviors; aspects such as knowing how to listen, putting oneself in the place of another person, understanding, knowing how to appreciate the other person and showing it to them, trusting, negotiating, cooperating, etc., are skills that can be improved and acquired if they are not innate. The extent to which they are put into practice in interpersonal relation contexts allows to consider them basic and useful tools for education in conflict regulation strategies. The serious attention deficiencies that exist in different environments, including education, are the source of constant physical, sexual, and psychological conflicts and aggressions in Latin America and the Caribbean. There is evidence of a gradual deterioration in interpersonal relationships, which has overwhelmed the capacities and preparation of teachers to cope with this situation (e.g., UNICEF, 2011; Ibarrola-García and Iriarte, 2012). Therefore, the need to transform classrooms into spaces of peaceful coexistence is growing; in this sense, the mediation of conflicts in the school environment has been gaining strength in recent decades, motivating the curiosity among professionals about the novelty and effectiveness of its contents and the supposed educational advantages it presents (Sandoval and Garro-Gil, 2017), since it allows to materialize in practice a set of educational principles in the framework of peace and human rights, life in democracy or civic education. It enables the development of capacities that transform conflicts by influencing the socio-personal development, through the discovery of skills and the recognition of diversity (Lederach, 2008), encouraging creative, reflexive and critical thinking, communicative and dialogic skills, responsibility, self-regulation, self-knowledge, and self-esteem. Moral and Pérez (2010) applied and evaluated a mediation program in the educational field, aimed at the prevention of structural violence, whose results evidenced the need to elaborate, apply and evaluate more programs of this type, since they not only collaborate in the resolution of the arised conflictive situations, but also encourage the involvement of the different actors in the educational environment, such as students, teachers, and administrative staff, who perceive mediation as a strategy that encourages change and transformation of interpersonal relationships.

The decrease in conflicts is noticeable in the educational centers that have applied mediation processes, where one of the factors indicated as determining for the success of the application of these processes, is the active participation of both the management team of the educational center and the teachers (Carrasco et al., 2016). The implementation, therefore, of a culture of peace achieved through initiatives of conflict mediation processes in education, should not only be a matter of learning and application for the student, but the adults should also be affected by the educational function of the processes of mediation. That is, if you really want to deepen the democratization of educational institutions with the use of mediation, the entire educational community must be guided, since they are all part of the relational dynamics and everyone is prone to get involved in conflict situations, although its members occupy different and unequal positions in the same institution and their rights and duties are regulated by means of different regulations.

Although it is true that the central point of mediation is to create spaces and generate tools and environments for the resolution of differences between people, the role played as a facilitator of relational meetings cannot be ignored, as a key that awakens creativity, reflection, recognition of the other and self-knowledge, factors that have been shown to help decrease verbal aggression and violence (Farell et al., 2001; Jones, 2001) and increase awareness of each of the parties as participants and responsible for their own conflicts.

Emotional Regulation

Emotional regulation, which refers to a process which people use to manage the emotions they experience, when they happen and how they are experienced and expressed is indispensable in order to adapt to social dynamics, trying to maintain good physical, psycho-emotional health, as well as healthy and productive interpersonal relationships. According to the Extended Process Model of Emotional Regulation proposed by Gross (2015), it is indicated that the emergence of emotions -and other affective states- occur as a result of a series of evaluations that individuals perform.

For example, negative emotions, such as anger, can trigger conflicts or even episodes of violence if they are not regulated properly (Fritz et al., 2015; Filella et al., 2018). This process begins with a given situation (entry), which is perceived by the person in a subjective way. The analysis generated by this perception allows the activation of an evaluation system for said situation, which finally leads to action. Gross (2015) highlights, as a central element in this process, that individuals have different evaluation systems, a reason that justifies the different types of outputs (responses or actions) that they manifest. Various studies have investigated this process linked to variables such as subjective psychological well-being (Pekrun et al., 2002; Ryff et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2017), the stage of development of the person (Mairean, 2015; Zamorano, 2017), or the use of cognitive reevaluation or suppression in academic contexts (Zamorano, 2017).

Regulating emotions requires effort, focused on different points. For example, exercise control over the processes that underlie the activation based on the maturation of neurophysiological regulation systems; emphasize the attention and input of information that directly affects the emotional state of the person; interpret information that is emotionally significant; manage the internal signals of emotional activation, to be able to access coping strategies if necessary, whether material or interpersonal; predict and control the emotional requirements that correspond to family scenarios; and select adaptive modes (behaviors that meet the demands of the context) to express themselves emotionally. By regulating emotions, people put into practice a whole range of analysis and evaluations, regarding which factors can bring them closer to the idealized emotional state. Considering the differences of these evaluation systems and implementing these processes into emotional regulation in educational institutions, to give emotional tools to students and teachers, involves the generation of better teaching environments, with a broad vision of educational processes, not only to instruct in the academic area, but for life in general; considering that developing the capacity to regulate emotions, from early ages of the evolutionary process, seems to produce long-term beneficial effects, since it helps to foster resistance to higher order desires, postponement and direct behavior toward the achievement of objectives (Hofmann et al., 2012; Oriol et al., 2017).

The acts of aggression that occur in the classroom do not refer to a problem of violence in itself, but is largely attributable to the lack of skills, education and emotional regulation, which teachers have in the first instance, as well as to the absence of previously established educational mediation strategies that allow an effective intervention to regulate the conflicts that arise in the classroom. Empirical research indicates that implementing systematic actions to train these skills has a real impact on reducing violent and aggressive behaviors (e.g., Pérez-Escoda et al., 2012; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2015; Filella et al., 2016).

The impact that student behavior has on the intensity and type of emotions that teachers experience is a factor to consider (Frenzel et al., 2009b), since they prefer to work with a student who works hard and is constantly motivated and focused on learning. This is perceived as very positive by teachers, which causes them to experience positive emotions and is an incentive to want to improve the teaching-learning processes (Hargreaves, 2000; Zembylas, 2002; Frenzel and Goetz, 2007; Frenzel et al., 2009b). Therefore, motivation and discipline in the classroom represent elements that influence experiences such as the enjoyment or anger of teachers (Becker et al., 2015).

The development of emotional skills represents the basis for learning and development of other abilities, being that the acquisition of knowledge is mediated by emotions (Khosla et al., 2009; Miller, 2010; Yip and Côté, 2013; Gilar-Corbí et al., 2018). The development of emotional skills represents the basis for learning and development of other abilities, being that the acquisition of knowledge is mediated by emotions (Khosla et al., 2009; Miller, 2010; Yip and Côté, 2013; Gilar-Corbí et al., 2018). When seeking and creating positive and nutritious teaching-learning environments, where the development of capacities for emotional management is promoted, another aspect that Gross includes in the Extended Process Model must be analyzed, the importance of the dynamic context as the setting for interpersonal relationships. This factor is an influencer that allows the teaching experiences to be strengthened, facilitating the internalization and apprehension of knowledge and its subsequent implementation by students (Woods, 2010, 2012; Erkutlu and Chafra, 2014; Goggin et al., 2015; Gilar-Corbí et al., 2018), while avoiding that teachers reach exhaustion when experiencing negative emotions (Chang, 2013).

Coping Strategies

By engaging in conflict situations throughout their lives, people manifest behaviors, cognitions and perceptions that allow them to regulate such situations. These manifestations are called coping strategies. The proposal made by Blake and Mouton (1964) in the Double Interest Model, a conceptual approach used in this article, allows analyzing both the interests of onself and those of other people involved in a conflictive situation. By combining both interests, five possible coping responses are generated in people; (a) integration (high self-interest and high interest in others); (b) domination (high self-interest and low interest in others); (c) servility (low self-interest and high interest in others); (d) avoidance (low self-interest and low interest in others); and (e) commitment (moderate self-interest and moderate interest in others) (Montes et al., 2014, p. 239).

Research aimed at studying the types of coping strategies used to regulate conflicts, have focused attention on aspects such as conflict and emotion (Cabanach et al., 2010), the social aspects, considering elements such as attitudes and belief systems or even a combination of concepts such as the resolution of applied problems and the theory of coping related to stress (Heppner et al., 2004). The taking of a decision that a person makes to face a conflict, underlies emotional aspects from previous experiences, which generate automatic behaviors, being that the perceived effectiveness of a problem-solving activity is seen as the degree to which one’s actions facilitate or inhibit progress toward solving the problem (Libin, 2017).

Given the diversity of aspects that influence (consciously or unconsciously) the selection of strategies and techniques to deal with conflict situations in everyday life, one of the main objectives of educational systems must be the teaching of emotional and social skills for coexistence of citizens and to resolve conflicts, considering that for young people, the importance of belonging and self-affirmation during the adolescence stage makes it essential to have coping skills and non-violent resolution of conflicts (López and de la Caba, 2011). An investigation by Mestre et al. (2012) noted that adolescents who have a low tendency to aggressiveness employ coping mechanisms focused on problem solving, seeking help and social support and focusing on the positive elements of the conflict. This implies the selection of a strategy that is interested in the self and also in the interests of others (Montes et al., 2010, 2014). Both dimensions are independent and, when combined, result in different coping strategies that are applied according to the objectives set, since, despite the fact that people respond to their conflicts based on their previous experiences and their own characteristics, also make the necessary modifications, according to the type of conflict they face (Laca Arocena and Alzate Sáez de Heredia, 2004). Starting from the theoretical perspective of Blake and Mouton (1964), and also including the contexts of personal interrelation, especially the educational field, and specifically the classroom, the need to analyze the behaviors of the people involved in a conflict is evident, to understand when they use coping strategies focused on the intrapersonal effect of emotional experience, that is, directed at the impact of affection on their own conflict behavior, and when they focus on the interpersonal effect of emotional experience, that is, in the impact of affection on the behavior of others. The fact of observing and identifying the coping strategies used by the students and by the teachers themselves, in their “pure state” (in situ, not manipulated), allows the implementation of adequate, prompt and direct tactics and mechanisms to better manage conflicts that arise in the classroom.

Integrated Circular Model of Conflict (ICMC)

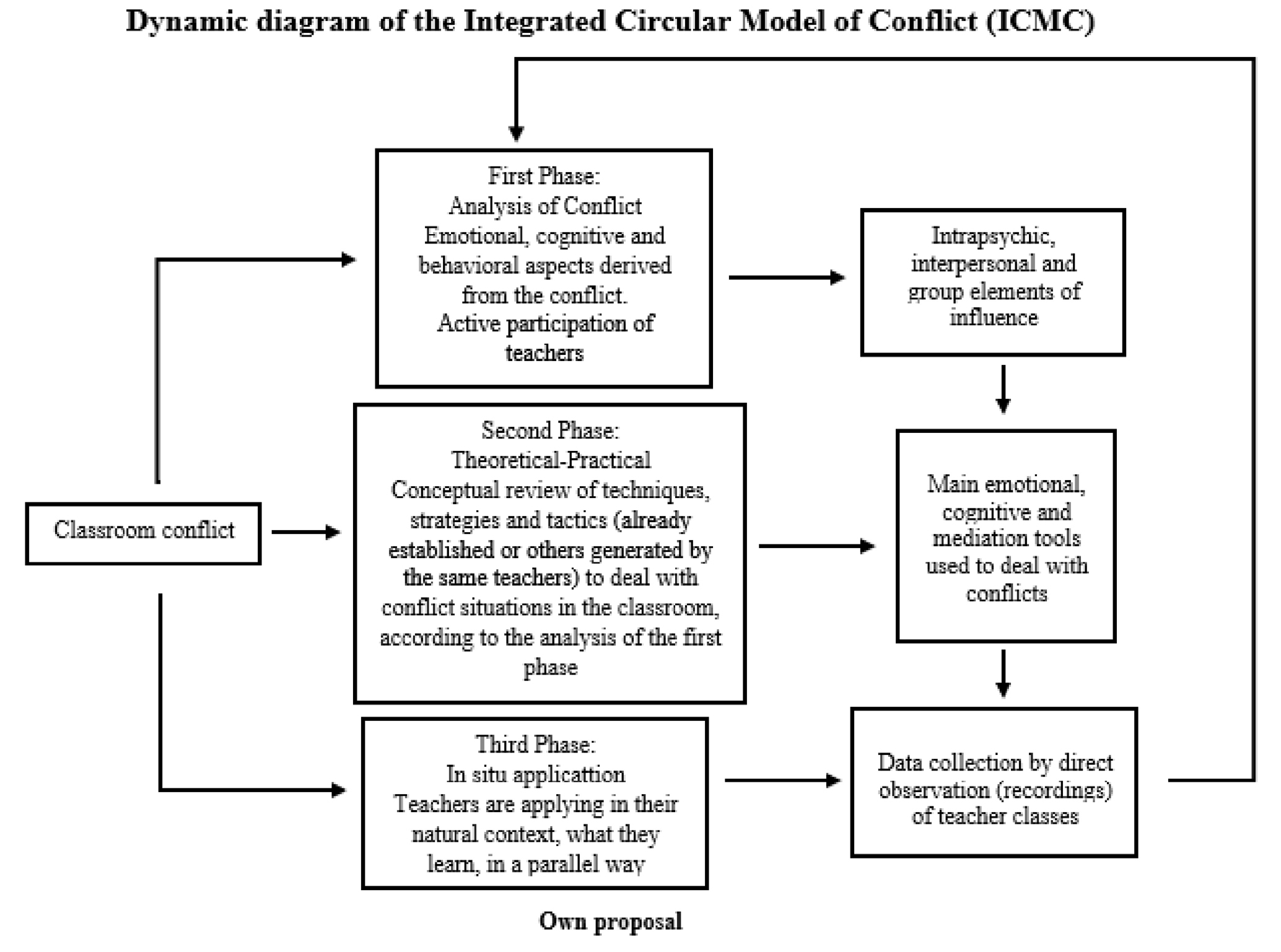

Analyzing that coping strategies involve a series of efforts that individuals make in order to get rid of unpleasant emotional experiences, a central point of differentiation with emotional regulation, which addresses emotions in general, not just limited to negative ones, in addition to knowing that coping strategies “… place greater emphasis on longer periods of time, such as, for example, coping with the death of a loved one” (Gross and Thompson, 2007; Gross, 2014; in Pascual and Conejero, 2019, p. 5), the ICMC is made up of three phases that include conflict analysis, theoretical and practical review and application in situ for the handling that teachers do of conflict situations that arise in the natural context of action, the classroom.

This model presents some similarities with other models and programs proposed above, in aspects such as the use of cognitive reevaluation for the creation of awareness, the development of coping resources for the management of conflict situations, the development of skills for emotional regulation, focus on working with teachers as primary users and students as secondary users, tutorial intervention, the use of mediation as one of the central points of the program, among others (e.g., P.E.C.E.R.A., by de Morales Ibáñez and Alzina, 2006; The Evaluation of the Structural Violence Prevention Program in the Family and in the School Centers, of Moral and Pérez, 2010; Happy Emotional Education Program, of Filella et al., 2018).

Specifically, in the area of emotional regulation or moods, the model ICMC takes the theoretical approach proposed by Groos as a reference. For example, from the Modal Model of Emotions (Gross and Thompson, 2007) the proposals adopted are that emotional regulation can be studied according to the place where the regulation strategy is inserted into the process of emotion generation (Gross, 1999). This is considered important because of the flexibility of action that it allows, thinking about the unique characteristics of the school environment, where it is required to be able to act not only depending on the conflict situation, but mainly on the emotional and behavioral reactions of those involved (especially the students). Two more aspects taken from the Model of Extended Process of Emotional Regulation (Gross, 2015) are included in the construction of the ICMC, the first is the consideration of the differences in the assessment systems that people have and the other is, the consideration of the context (educational in this case) as an element of influence at the time of the emergence and subsequent regulation of emotional states. Considering these three aspects, the model ICMC focuses on the instruction for teachers, the use of cognitive reevaluation, as a basis for the development of consciousness and as a complement to the debate of one’s thoughts, aiming to achieve in them a flexible way of thinking that helps to contemplate the wide range of nuances that exist to regulate a conflict before reaching states of aggression and violence. In addition, the teaching-learning process for emotional regulation includes the observation and analysis of the context and the educational environment, specifically the classroom, the natural field of the teacher’s work, confirming what Trías points out “… teachers are key actors in understanding what occurs in the classrooms, and consequently, should have a more relevant place in research on the self-regulation of learning” (Trías, 2017, p. 125).

This element encourages the use of creativity and imagination of those involved in a conflict, elements not indicated in the Gross and Thompson Model, but emphatically in the conflict theory of Lederach (2008) and of the Transformative Mediation of Bush and Folger (1996) not only to find ways to solve the conflict situation, but also to generate resources through which people can analyze and know themselves (inside-revaluation) and at the same time activate mechanisms of emotional regulation aimed at social interaction (outside-recognition), being able to exercise control not about the emergence of thoughts or emotions, but about the reactions, from spontaneous and automatic reactions to reactions mediated by the reflexive act (use of the cognitive). These points are important since, according to McFarland et al. (2003), the self-knowledge acquired by people who have a tendency to attend their own mood, is involved in the development of greater regulatory capacity and, therefore, a greater adaptation capacity for interpersonal relationships.

Regarding the alternative dispute resolution models proposed so far, the ICMC is radically separated from the punitive or sanctioning model, by virtue of the empirical evidence that shows its little to no effectiveness in the medium and long term (Sánchez Ruiz, 2016). The theoretical perspective that the ICMC incorporates to tackle the construct of Conflict Resolution is the transformative mediation model from which it adopts the position to transform the conflict extending to the objectives of each one of the conflicted parties (Galtung, 2003) and the elements of revaluation and recognition of the model of transformative mediation (Bush and Folger, 1996). It coincides in some points with the proposal of the integrated conflict model (Caramés et al., 2010), for example, in trying to balance the positions of both parties involved in the conflict, so that, from there, they can work more focused on the reestablishment of the relationship than in the result obtained in the mediation, and like this one, proposes an analysis of the conflict and the coping strategies of those involved.

The ICMC has two particular characteristics that aim to complete some gaps detected in these models; on the one hand, it is a dynamic model (Diagram 1) that feeds on the experiences of teachers and makes adjustments according to the needs of each educational institution. This represents a differential point of other models and programs that present pre-established and equal training for all educational centers. The consideration of the differences existing in each educational institution, in aspects such as the location, the number of students, whether it is private, public or semi-private, if they have mediation programs already established in the center, hourly availability, among others, are factors that should be considered so that the implementation of the program or model has a greater chance of causing a significant and lasting impact over time. In addition, it represents a point of identification and involvement of teachers within the model, since it is being built and fed back from their experiences.

The other aspect that differentiates it is the flexibility of being able to carry out constant evaluations of the activities that are worked with teachers, since these are being implemented in parallel in the daily routine of the teaching functions. These constant evaluations allow to make the necessary adjustments, almost immediately, since the recordings of the classes of the participating teachers are used, under a direct observation methodology (Portell et al., 2015a, b; Anguera et al., 2017) in order to record the perceptible behavior of teachers when they face conflict situations.

Connection Between Conflict Mediation, Emotional Regulation and Coping Strategies and Its Applicability in the Educational Field

Under this conceptual framework, the relationship between conflict mediation, emotional regulation, and coping strategies, and its application in the field of education is analyzed.

A mediation process must consider the emotional aspects that influence the creation of the conflict, for example, negative emotions, such as anger, can trigger conflicts or even episodes of violence if they are not properly regulated (Filella et al., 2018).

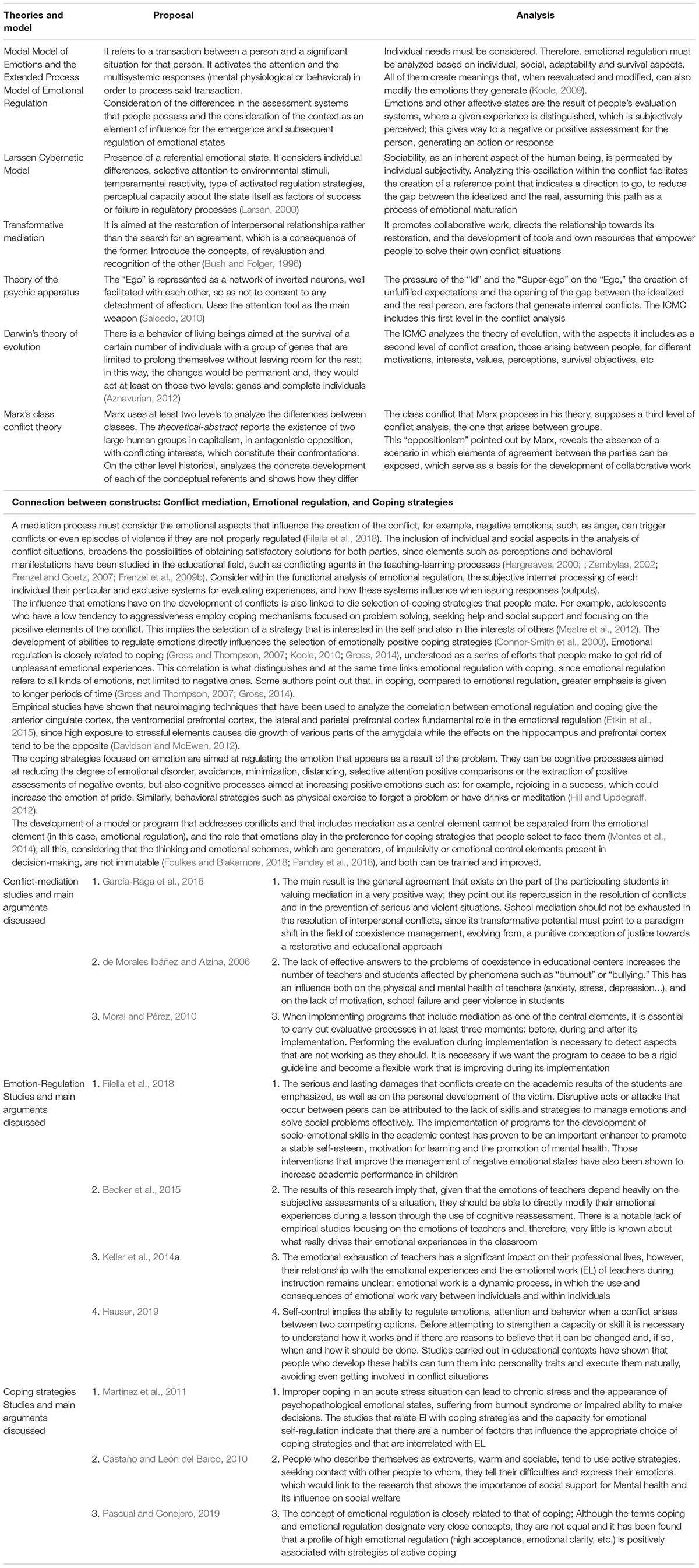

The inclusion of individual and social aspects (different levels) (Table 1) in the analysis of conflict situations, broadens the possibilities of obtaining satisfactory solutions for both parties, since elements such as perceptions and behavioral manifestations have been studied in the educational field, such as conflicting agents in the teaching-learning processes (Hargreaves, 2000; Zembylas, 2002; Frenzel and Goetz, 2007; Frenzel et al., 2009b).

Table 1. Conceptual summary of the Integrated Circular Model of Conflict Theories, models and previous studies.

The influence that emotions have on the development of conflicts is also linked to the selection of coping strategies that people make. The development of abilities to regulate emotions directly influences the selection of emotionally positive coping strategies (Connor-Smith et al., 2000). The concept of emotional regulation is closely related to that of coping (Gross and Thompson, 2007; Koole, 2010; Gross, 2014). Coping understood as the efforts that people make to get rid of unpleasant emotional experiences. This, specifically, is what distinguishes and at the same time links emotional regulation with coping, since emotional regulation refers to all kinds of emotions, not limited to negative ones. In addition, some authors point out that, in coping, compared to emotional regulation, greater emphasis is given to longer periods of time (Gross and Thompson, 2007; Gross, 2014).

The neuroimaging techniques that have been used to analyze the relationship between emotional regulation and coping, give the anterior cingulate cortex, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the lateral and parietal prefrontal cortex a fundamental role in emotional regulation (Etkin et al., 2015). Empirical studies have shown that high exposure to stressors is associated with the growth of various parts of the amygdala while the effects on the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex tend to be the opposite (Davidson and McEwen, 2012).

The coping strategies focused on emotion are aimed at regulating the emotion that appears as a result of the problem. They can be cognitive processes aimed at reducing the degree of emotional disorder, avoidance, minimization, distancing, selective attention, positive comparisons or the extraction of positive assessments of negative events, but also cognitive processes aimed at increasing emotion such as, for example, gloating in a success, which could thus increase the emotion of pride. Similarly, behavioral strategies such as physical exercise to forget a problem or have drinks or meditation (Hill and Updegraff, 2012).

The development of a model or program that addresses conflicts and that includes mediation as a central element cannot be separated from the emotional element (in this case, emotional regulation), and the role that emotions play in the preference for strategies of coping that people select to face them (Montes et al., 2014); all this, considering that the thinking and emotional schemes, which are generators of impulsivity or emotional control, elements present in decision-making, are not immutable (van Gaal et al., 2012; Foulkes and Blakemore, 2018; Pandey et al., 2018), and both can be trained and improved.

Discussion

Empirical evidence has shown the close links between the emergence, development and regulation of conflicts, emotional regulation and coping strategies (e.g., Amstadter, 2008; Bargh and Morsella, 2008; Custers and Aarts, 2010; Garaigordóbil and Peña-Sarrionandia, 2015, among others). People with more developed emotional intelligence naturally tend to attend to their own moods, usually select more adaptive coping strategies, focused on conflict regulation, with a high share of commitment toward collaborative work and, in addition, tend less to get involved in conflict situations (Extremera Pacheco and Fernández-Berrocal, 2013).

To address this interaction, knowledge is required to generate resolution and prevention tools for the accelerated growth of conflicts experienced by educational institutions in many countries around the world (Filella et al., 2018), contemplating the different factors involved. This study proposes a model aimed at facilitating the development of resources for teachers that allow them to improve the management of the different conflict situations that arise in the context of the classroom. This dynamic model aims to complete gaps detected in other previously developed models, integrating elements that allow a synergy of actions aimed at stimulating the cognitive, emotional and behavioral dimensions, in a more complete way than what is provided by each element separately.

For the elaboration of ICMC, conceptual proposals have been analyzed (e.g., Hauser, 2019), empirical studies of psycho-pedagogical intervention in emotional education and experience sampling, applied in the field of education (e.g., P.E.C.E.R.A., by de Morales Ibáñez and Alzina, 2006; The Evaluation of the Program for the Prevention of Structural Violence in the Family and School Centers, of Moral and Pérez, 2010; Happy Emotional Education Program, of Filella et al., 2018), as well as models and theories that deal with the central elements separately (e.g., Murray, 2005; Caballero, 2010; Cabanach et al., 2010; Pérez-Escoda et al., 2013; Romera et al., 2015; Balzarotti et al., 2016; Filella et al., 2016, among others); this analysis has indicated three possible areas of conflict development that should be considered; in the first place, the conflict that the person has with himself (from the theory of the psychic apparatus, Salcedo, 2010); second, the conflict that the person has with another person (from Darwin’s theory of evolution, Aznavurian, 2012) and, finally, the conflict that is generated between groups (from Marx’s class conflict theory, Izaguirre, 2014). We consider that analyzing this oscillation between the “I” and the “we,” between the being as an individual entity and the being as a social entity, with the mediation of exercises that encourage creativity, imagination, reflection and the development of consciousness, it enables the execution of cognitive reevaluation and, therefore, the development of the ability to alter one’s responses, one of the characteristics associated with the human condition (Baumeister and Heatherton, 1996).

Carrying out constant evaluations of daily tasks and including teachers as main protagonists, adds value to this model, since it allows them to expand their functions, not only acting as transmitters of knowledge, but also as generators of information aimed at developing research which will result in improvements in their own functions, taking advantage of their experiences to enrich the teaching–learning processes, recognizing the importance of the research–practice–research relationship. This, in addition to representing an applied advantage over other previous models and programs, allows to produce new theories related to educational dynamics and the importance of teacher participation, which supports and in turn enables a more rigorous empirical development. A door is left open for the application of this model with the objective of obtaining empirical results that demonstrate its strengths and weaknesses, improving the weak aspects for future research.

Conclusion

Addressing the conflictive situations that arise in the educational field, and specifically in the context of the classroom, is not a simple task, especially due to the lack of preparation, and therefore of resources and tools presented by teachers, whose emotional manifestations are subject to student behaviors (Becker et al., 2015); due to this, there are effects on areas such as, instructional environments (Hargreaves, 2000), the well-being and health of teachers (e.g., Chang, 2009; Keller et al., 2014), effectiveness in the classroom (e.g., Sutton, 2005) or emotions and motivation of the students (e.g., Frenzel et al., 2009a; Radel et al., 2010; Becker et al., 2014).

Various empirical studies (e.g., UNICEF, 2011; Keller et al., 2014; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2015, among others) have concluded that the classroom is the place where more conflicts are produced in schools (Martínez, 2018), also, that emotions are the most determining factor in the emergence of conflicts between people, and that these are directly related to the selection of coping strategies that people make to regulate these situations (Montes et al., 2014).

Given the evidence of studies that analyze these constructs separately, we conclude the following; it is necessary to create a model that integrates the most important aspects, involved in the emergency, development and regulation of conflicts in education, such as conflict mediation, emotional regulation and coping strategies, in order to deepen the concepts, analyze and synthesize the aspects that link some elements with others to develop exercises, implement them and evaluate them in a way that generates cognitive, emotional and behavioral resources, which makes it possible to improve the management that teachers make of the conflicts that arise in the classroom.

The generation of more theory that supports the empirical research (Keller et al., 2014) carried out in the area of conflicts, emotions and coping strategies in the educational field is required. This model succeeds other models and programs (e.g., Gross and Thompson, 2007; The Evaluation of the Program of Prevention of Structural Violence in the Family and in the School Centers, of Moral and Pérez, 2010; P.E.C.E.R.A., of de Morales Ibáñez and Alzina, 2006; Happy Emotional Education Program, Filella et al., 2018) that have shown the importance of each central element of this research, separately, but never together, which turns this model into a pioneering proposal, which aims to make a contribution to solve this need of lack of knowledge.

To ensure that teachers solve the training gaps that they show when they face conflicts in the educational field, one of the first aspects that must be worked with them is the direct modification of their emotional experiences through cognitive reevaluations (Becker et al., 2015). Cognitive reevaluation plays a very important role in regulating emotions and, in effect, behaviors; Therefore, future studies could consider how this intervention should be designed to promote effective and adaptive cognitive reevaluation strategies in teachers so that they can benefit emotionally.

Synthesizing, this study offers relevant and timely information on the operation of the central constructs of the ICMC model, conflict mediation, emotional regulation and coping strategies, and how they interrelate at the moment that a conflict emerges. First advancing toward the understanding of the processes involved, at the intra-individual and interrelational level (from the proposal of the Extended Process Model of Emotional Regulation, Gross, 2015), since before trying to strengthen a capacity or ability it is necessary to understand how it works and if there are reasons to believe that it can be changed and, if so, when and how it should be done (Berkman, 2016). This understanding derives not only in new points of view for future conceptual studies that deepen the changing and vertiginous needs experienced by educational institutions, teachers and students, but also in scientific development aimed at achieving conceptual improvements and strengthening existing theories. This has important practical implications for teachers, in aspects such as the development of essential skills for managing conflicts arising in their natural context of action, the classroom; learning techniques to be able to distance themselves emotionally from conflict situations (abstraction) and have the ability to analyze and decide clearly (perspective) the actions to follow (Fujita et al., 2006). Another practical implication involves training teachers for the formation of habits to regulate emotions, so that they in turn can transmit them to students. Studies carried out in educational contexts have shown that people who develop these habits can turn them into personality traits and execute them naturally, avoiding even getting involved in conflict situations (e.g., Galla and Duckworth, 2015; Duckworth et al., 2016).

Finally, with the strengthening of these three elements: conflict mediation, emotional regulation and coping strategies, teachers enable the reduction of behavioral problems in the classroom, with fewer interruptions between classmates, and with more involved and participatory students in educational issues (Hauser, 2019).

Limitations

Although this study provides evidence linking particular characteristics of each of the central elements, which can be complemented to develop a conceptual model that responds to the growing number of conflicts that arise in schools, its conclusions are limited in several ways.

Prospective studies are required to validate the complementarity of these elements in a single conceptual model and should serve as a basis for future adjustments to the model.

In the absence of empirical data evidencing the linkage between these three elements together, the approach and the results of this model should be interpreted with caution. In future studies, other variables may be included that may be important factors in the emergence, development and regulation of conflicts in educational institutions, for example, specific competences of the subject, personality, social, family factors, among others. It is also suggested that any other research carried out that includes some of these core elements should apply research methods with process-oriented measurements, as well as direct observation of teacher performance, with the objective of adding value compared to other studies, regarding the registration of their perceptible behaviors, and of the different dimensions involved, cognitive, expressive (emotional), and behavioral (Bruchmann et al., 2011).

Finally, since previous research has shown the link between the emotions of teachers and the motivation of students (Frenzel et al., 2009a; Ursu et al., 2009; Kunter et al., 2013), it is suggested to future research to analyze whether there is a direct involvement between cognitive reevaluation and the level of motivation of students and teachers; that is, if cognitive reevaluation can stimulate nociceptive neurons that in turn promote the motivational states of people.

Author Contributions

PB contributed to conceptual structure, and responsible for the literature review and the drafting of this manuscript. IA made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication. MA revised the manuscript and approved it for publication.

Funding

PB gratefully thanks to Universidad Estatal a Distancia de Costa Rica (UNED) the support of an academic grant (Acuerdo COBI No 7661), in order to do this research. PB and IA also acknowledge the support of University of Barcelona (Vice-Chancellorship of Doctorate and Research Promotion). IA thanks also the support from Grup de Recerca en Psicologia Social, Ambiental i Organitzacional 2017 SGR 00564 (PSICOSAO). MA gratefully acknowledges the support of a Spanish government subproject Integration ways between qualitative and quantitative data, multiple case development, and synthesis review as main axis for an innovative future in physical activity and sports research (PGC2018-098742-B-C31) (2019-2021) (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades/Agencia Estatal de Investigación/Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional), that is part of the coordinated project New approach of research in physical activity and sport from mixed methods perspective (NARPAS_MM) (SPGC201800X098742CV0). In addition, MA thanks the support of the Generalitat de Catalunya Research Group, GRUP DE RECERCA I INNOVACIÓ EN DISSENYS (GRID). Tecnología i Aplicació Multimedia i Digital als Dissenys Observacionals (Grant number 2017 SGR 1405).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Amstadter, A. (2008). Emoton regulation and anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 22, 211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.004

Anguera, M. T., Camerino, O., Castañer, M., Sánchez-Algarra, P., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2017). The specificity of observational studies in physical activity and sports sciences: moving forward in mixed methods research and proposals for achieving quantitative and qualitative symmetry. Front. Psychol. 8:2196. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02196

Aznavurian, A. (2012). Darwin Hoy. Análisis de Problemas Universitarios. 188X–168X. Avaliable at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=340/34023237002.

Balzarotti, S., Biassoni, F., Villani, D., Prunas, A., and Velotti, P. (2016). Individual differences in cognitive emotion regulation: implications for subjective and psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 17, 125–143. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9587-3

Baumeister, R., and Heatherton, T. (1996). Self-regulation failure: an overview. Psychol Inq. 7, 1–15.

Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., Morger, V., and Ranellucci, J. (2014). The importance of teachers’ emotions and instructional behavior for their students’ emotions—an experience sampling analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 43, 15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.002

Becker, E. S., Keller, M. M., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., and Taxer, J. L. (2015). Antecedents of teachers’ emotions in the classroom: an intraindividual approach. Front. Psychol. 6:635. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00635

Berkman, E. T. (2016). “Self-regulation training,” in Handbook of Self-Regulation, eds K. D. Vos and R. F. Baumeister (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 440–457.

Blair, C., and Raver, C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: a developmental psychobiological approach. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 711–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015221

Bruchmann, M., Herper, K., Konrad, C., Pantev, C., and Huster, R. J. (2011). Individualized EEG source reconstruction of stroop interference with masked color words. Neuroimage 49, 1800–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.032

Bush, R. A. B., and Folger, J. P. (1996). La Promesa de la Mediación. Cómo Afrontar el Conflicto a Través del Fortalecimiento Propio y el Reconocimiento de los Otros [The Promise of Mediation. How to Deal with Conflict Through Self-Strengthening and the Recognition of Others]. Barcelona: Ediciones Granica S.A.

Bush, R. A. B., and Pope, S. (2008). La mediación transformativa: un cambio en la calidad de la interacción en los conflictos familiares [Transformative Mediation: a change in the quality of interaction in family conflicts]. Revista Med 2, 17–28.

Caballero, G. (2010). Convivencia escolar. un estudio sobre buenas prácticas. [School coexistence. Study on good practices]. Rev. Paz. Confl. 3, 154–168.

Cabanach, R., Valle, A., Rodríguez, S., Piñeiro, I., and Freire, C. (2010). Escala de afrontamiento del estrés académico (A-CEA) [Coping Scale of Academic Stress (A-CEA)]. Rev Iberoam. Psicol. Salud 1, 51–64.

Caramés, L., Caramés, L., Vera, M., and Ordóñez, J. J. (2010). Mediación y Resolución de Conflictos: El Modelo Integrado. [Mediation and conflict resolution: The Integrated Model.]. Avaliable online at: http://eoepsabi.educa.aragon.es/descargas/H_Recursos/h_1_Psicol_Educacion/h_1.8.Mediacion/10.Mediacion_modelo_integrado.pdf

Carrasco, S., Villà, R. Y., and Ponferrada, M. (2016). Resistencias institucionales ante la mediación escolar. Una exploración en los escenarios de conflicto. [Institutional resistance to school mediation. An exploration in conflict scenarios.]. Rev. Antropol. Soc. 25, 11–131.

Carrasco, V., and Corral, J. (2009). Estudio de Caso: la Cultura de la Mediación. Una Experiencia de Formación en Educación Secundaria [Case Study: The Culture of Mediation. A Training Experience in Secondary School.] [Paper Presentation]. X Congresso Internacional Galego-Português de Psicopedagogia. Braga: Universidade do Minho.

Castaño, E. F., and León del Barco, B. (2010). Estrategias de afrontamiento del estrés y estilos de conducta interpersonal. [Stress coping strategies and interpersonal behaviour styles.]. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 10, 245–257.

Chang, M.-L. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: examining the emotional work of teachers. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 21, 193–218. doi: 10.1007/s10648-009-9106-y

Chang, M.-L. (2013). Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of student misbehavior: appraisal, regulation and coping. Mot. Emot. 37, 799–817. doi: 10.1007/s11031-012-9335-0

Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., and Saltzman, H. (2000). Responses to STRESS in adolescence: measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 976–992. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.976

Custers, R., and Aarts, H. (2010). The unconscious will: how the pursuit of goals operates outside of conscious awareness. Science 329, 47–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1188595

Davidson, R. J., and McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 689–695. doi: 10.1038/nn.3093

de Morales Ibáñez, M., and Alzina, B. R. (2006). Evaluación de un programa de educación emocional para la prevención del estrés psicosocial en el contexto del aula. [Evaluation of an emotional education program for the prevention of psychosocial stress in the classroom context.]. País Vasco Rev. Ansi. Estrés 12, 401–412.

Duckworth, A. L., Gendler, T. S., and Gross, J. J. (2016). Situational strategies for self-control. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11, 35–55. doi: 10.1177/1745691615623247

Erkutlu, H., and Chafra, J. (2014). Ethical leadership and workplace bullying in higher education. Hacettepe Univ. J. Educ. 29, 55–67. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0577-0

Etkin, A., Buchel, C., and Gross, J. J. (2015). The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 693–700. doi: 10.1038/nrn4044

Extremera Pacheco, N., and Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2013). Inteligencia emocional en adolescentes [Emotional intelligence in adolescents]. Rev. Pad. Maestros 352, 34–39.

Farell, A., Myer, A., and White, K. (2001). Evaluation of responding in peaceful and positive ways (RIPP): a school-based prevention program for reducing violence among urban adolescents. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 30, 451–463. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_02

Filella, G., Cabello, E., Pérez-Escoda, N., and Ros-Morente, A. (2016). Evaluación del programa de Educación Emocional “Happy 8-12” para la resolución asertiva de conflictos entre iguales. [Evaluation of the Emotional Education program “Happy 8-12” for the assertive resolution of conflicts between equals.]. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 14, 582–601. doi: 10.14204/ejrep.40.15164

Filella, G., Ros-Morente, A., Oriol, X., and March-Llanes, J. (2018). The assertive resolution of conflicts in school with a gamified emotion education program. Front. Psychol. 9:2353. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02353

Folger, J. P. (2008). La mediación transformativa: preservación del potencial único de la mediación en situaciones de disputas [Preservation of the unique potential of mediation in dispute situations]. Rev. Med. 6–16.

Foulkes, L., and Blakemore, S.-J. (2018). Studying individual differences in human adolescent brain development. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 315–323. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0078-4

Frenzel, A. C., and Goetz, T. (2007). Emotionales erleben von lehrkräften beim unterrichten. Z. Pädagog. Psychol. 21, 283–295. doi: 10.1024/1010-0652.21.3.283

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., and Sutton, R. E. (2009a). Emotional transmission in the classroom: exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 705–716. doi: 10.1037/a0014695

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Pekrun, R., and Jacob, B. (2009b). “Antecedents and effects of teachers’ emotional experiences: an integrated perspective and empirical test,” in Advances in Teacher Emotion Research: The Impact on Teachers’ Lives, eds P. A. Schutz and M. Zembylas (Berlin: Springer), 129–152.

Fritz, J., Fischer, R., and Dreisbach, G. (2015). The influence of negative stimulus features on conflict adaption: evidence from fluency of processing. Front. Psychol. 6:185. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00185

Fujita, K., Trope, Y., Liberman, N., and Levin-Sagi, M. (2006). Construal levels and self-kolhe control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 90, 351–367.

Galla, B. M., and Duckworth, A. L. (2015). More than resisting temptation: beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. J. Perspect. Soc. Psychol. 109, 508–525. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000026

Galtung, J. (2003). Paz Por Medios Pacíficos. [Peace by Peaceful Means.], 1st Edn. Bakeaz: Sage, 267–273.

Garaigordóbil, M., and Peña-Sarrionandia, A. (2015). Effects of an emotional intelligence program in variables related to the prevention of violence. Front. Psychol. 6:743. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00743

García-Raga, R. L., Chiva, I., Moral, A. Y., and Ramos, G. (2016). Fortalezas y debilidades de la mediación escolar desde la perspectiva del alumnado de educación secundaria. [Strengths and weaknesses of school mediation from the perspective of secondary school students.]. Pedagogía Soc. Rev. Int. 28, 203–215. doi: 10.7179/PSRI_2016.28.15

Gilar-Corbí, R., Pozo-Rico, T., Sánchez, B., and Castejón, J. L. (2018). Can emotional competence be taught in higher education? a randomized experimental study of an emotional intelligence training program using a multimethodological approach. Front. Psychol. 9:1039. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01039

Goggin, D., Cassidy, S., Sheridan, I., and O’Leary, P. (2015). “Extensibility-validation of workplace learning in higher education-examples and considerations,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Barcelona, 4966–4973.

Gómez-Ortiz, O., Del Rey, R., Romera, E. Y., and Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2015). Los estilos educativos paternos y maternos en la adolescencia y su relación con la resiliencia, el apego y la implicación en acoso escolar. [Paternal and maternal educational styles in adolescence and their relationship with resilience, attachment and involvement in bullying.]. Anal. Psicol. 31, 414–425. doi: 10.6018/analesps.31.3.180791

Gross, J. (1999). “Emotion and emotion regulation,” in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2nd Edn, eds L. A. Pervin and O. P. John (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 525–552.

Gross, J. J. (2014). “Emotion regulation: conceptual and empirical foundations,” in Handbook of Emotion Regulation, 2nd. Edn, ed. J. J. Gross (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 3–20.

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychol. Inq. 26, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Gross, J. J., and Thompson, R. A. (2007). “Emotion regulation: conceptual foundations,” in Handbook of Emotion Regulation, ed. J. J. Gross (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 3–24.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: teachers’ perceptions of their interactions with students. Teach. Teach. Educ. 16, 811–826. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2014.930403

Hauser, M. D. (2019). Patience! How to Assess and Strengthen Self-Control. Front. Educ. 4:25. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00025

Heppner, P. P., Witty, T. E., and Dixon, W. A. (2004). Problem-solving appraisal and human adjustment: a review of 20 years of research using the problem-solving inventory. Couns. Psychol. 32, 344–428. doi: 10.1177/0011000003262793

Hill, C. L. M., and Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion 12, 81–90. doi: 10.1037/a0026355

Hofmann, W., Baumeister, R. F., Förster, G., and Vohs, K. D. (2012). Everyday temptations: an experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. J. Perspect. Soc. Psychol. 102:1318. doi: 10.1037/a0026545

Ibarrola-García, S. E., and Iriarte, C. (2012). La Convivencia Escolar en Positivo: Mediación y Resolución de Conflictos. Madrid: Pirámide.

Izaguirre, I. (2014). Acerca de la teoría de las clases y de la lucha de clases. Por qué han sido sustituidas las clases sociales en el discurso académico. [About the lass theory and the class conflict theory. Why social classes have been replaced in academic discourse.]. Theomai 29, 13–37.

Jones, T. S. (2001). Evaluating Your Conflict Resolution Education Program: a Guide for Educators and Evaluators. Columbus, OH: Ohio Commission on Dispute Resolution and Conflict management.

Keller, M. M., Chang, M.-L., Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., and Frenzel, A. C. (2014). Teachers’ emotional experiences and exhaustion as predictors of emotional labor in the classroom: an experience sampling study. Front. Psychol. 5:1442. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.014

Khosla, R., Chu, M. T., Yamada, K. G., Kuneida, K., and Oga, S. (2009). “Emotionally intelligent diagnostic assessment for personalised e-training,” in 2009 11th IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (Ism 2009), San Diego, CA: IEEE, 693–698.

Koole, S. (2009). The psychology of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Cogn. Emot. 23, 4–41. doi: 10.1080/02699930802619031

Koole, S. L. (2010). “The psychology of emotion regulation: an integrative review,” in Cognition & Emotion: Reviews of Current Research and Theories, eds J. De Houwer and D. Hermans (Nueva York, NY: Psychology Press), 128–167.

Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., and Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: effects on instructional quality and student development. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 805–820. doi: 10.1037/a0032583

Laca Arocena, F., and Alzate Sáez de Heredia, R. (2004). Estrategias de conflicto y patrones de decisión bajo presión de tiempo. [Conflict strategies and decision patterns under the pressure of time.]. Rev. Int. Cien. Soc. Hum. Soc. 15

Lederach, J. (2008). La imaginación Moral: el Arte y el Alma de Construir la paz. [The Moral Imagination: the art and Soul of Building Peace.]. Bogotá: Grupo Editorial Norma.

Libin, E. (2017). Coping Intelligence: efficient life stress management. Front. Psychol. 8:302. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00302

Limonero, J. T., Tomás-Sábado, J., Fernández-Castro, J., Gómez-Romero, M. J., and Ardilla-Herrero, A. (2012). Estrategias de afrontamiento resilientes y regulación emocional: predictores de satisfacción con la vida [Resilient coping strategies and emotion regulation: predictors of life satisfaction]. Psicol. Cond. Rev. Int. Clín. Salud 20, 183–196.

López, A. R., and de la Caba, C. M. (2011). Estrategias de afrontamiento ante el maltrato escolar en estudiantes de Primaria y Secundaria. [Coping strategies facing school abuse in Primary and Secondary students.]. Oviedo Rev. Dial. 39, 59–68.

Luo, Y., Qi, S., Chen, X., You, X., Huang, X., and Yang, Z. (2017). Pleasure attainment or selfrealization: the balance between two forms of well-being are encoded in default modenetwork. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 12, 1678–1686. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsx078

Lyubomirsky, S., and Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 46, 137–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006824100041

Mairean, C. (2015). Individual differences in emotion and thought regulation processes:implications for mental health and wellbeing. Symposion 2, 243–260.

Martínez, A. E., Piqueras, J. A., and Inglés, C. J. (2011). Relaciones entre Inteligencia emocional y estrategias de afrontamiento ante el estrés. [Relationships between Emotional Intelligence and Coping Strategies with stress.]. Rev. Elect. Motiv. Emoc 14:37.

Martínez, M. (2018). La formación en convivencia: papel de la mediación en la solución de conflictos. [Training in coexistence: the role of mediation in conflict resolution.]. Educ. Hum. 20, 127–142. doi: 10.17081/eduhum.20.35.2838

McFarland, C., White, K., and Newth, S. (2003). Mood acknowledgment and correction for the mood-congruency bias in social judgment. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 39, 483–491.

Medina Díaz, M. (2015). Mediación entre pares en las escuelas públicas: una alternativa para la solución de conflictos. [Mediation between pairs in public schools: an alternative for conflict resolution.]. Griot 8, 85–103.

Mestre, V., Samper, P., Tur-Porcar, A., Richaud de Minzi, M., and Mesurado, B. (2012). Emociones, estilos de afrontamiento y agresividad en la adolescencia. [Emotions, coping styles and aggressiveness in adolescence.]. Univ. Psychol. 11, 1263–1275.

Miller, A. M. (2010). Emotionally intelligent leadership: a guide for college students. Rev. High Educ. 33, 294–295. doi: 10.1353/rhe.0.0120

Miñaca-Laprida, M. I., Hervás, M., and Laprida-Martín, I. (2013). Análisis de programas relacionados con la educación emocional desde el modelo propuesto por Salovey y Mayer [Analysis of programs related to emotional education from the model proposed by Salovey and Mayer]. Rev. Educ. Soc. 17, 1–17.

Monjas, M. I., Sureda, I., and Basete, G. F. J. (2008). ¿Por qué los niños y las niñas se aceptan y se rechazan? [Why boys and girls accept and reject each other?]. Cult. Educ. 20, 479–492.

Montes, C., Rodríguez, D., and Serrano, G. (2014). Estrategias de Manejo de Conflicto en Clave Emocional. [Conflict Management Strategies in an Emotional Key]. Available online at: http://revistas.um.es/analesps (accessed March 21, 2019).

Montes, C., Serrano, G., and Rodríguez, D. (2010). Impacto de las motivaciones subyacentes en la elección de las estrategias de conflicto. Bol. Psicol. 100, 55–69.

Moral, A. M., and Pérez, M. D. (2010). La evaluación del “Programa de prevención de la violencia estructural en la familia y en los centros escolares”. Rev. Española Orientac. Psicopedagogía 21, 25–36.

Murray, S. L. (2005). Regulating the risks of closeness a relationship specific sense of felt security. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 14, 74–78. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00338.x

Oriol, X., Miranda, R., Oyanedel, J. C., and Torres, J. (2017). the role of self-control and grit in domains of school success in students of primary and secondary school. Front. Psychol. 8:1716. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01716

Ortega, R. (2006). “La convivencia: un modelo de prevención de la violencia [“Coexistence: a model of violence prevention”],” in La Convivencia en las Aulas, Problemas y Soluciones, eds A. Moreno and M. P. Soler (Bleiberg: Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia). doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.483

Pandey, A., Hale, D., Das, S., Goddings, A.-L., Blakemore, S.-J., and Viner, R. M. (2018). Effectiveness of universal self-regulation–based interventions in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 172, 566–575. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0232

Pascual, O. J. A., and Conejero, L. S. (2019). Regulación emocional y afrontamiento: aproximación conceptual y estrategias. [Emotional regulation and coping: conceptual approach and strategies]. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 36, 74–83.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., and Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 37, 91–105. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

Peña, M., and Repetto, E. (2008). Estado de la investigación en España sobre Inteligencia Emocional en el ámbito educativo. [State of research in Spain on Emotional Intelligence in the educational field.]. Revi. Electr. Investig. Psicoeducat. 6, 400–420.

Pérez-Escoda, N., Filella, G., Bisquerra, R., and Alegre, A. (2012). Desarrollo de la competencia emocional de maestros y alumnos en contextos escolares. [Development of the emotional competence of teachers and students in school contexts.]. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 10, 1183–1208.

Pérez-Escoda, N., Filella, G., Soldevila, A., and Fondevila, A. (2013). Evaluación de un programa de educación emocional para profesorado de primaria [Evaluation of an emotional education program for primary school teachers]. Educación 16, 233–254.

Portell, M., Anguera, M. T., Chacón-Moscoso, S., and Sanduvete-Chaves, S. (2015a). Guidelines for reporting evaluations based on observational methodology (GREOM). Psicothema 27, 283–289. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2014.276

Portell, M., Anguera, M. T., Hernández-Mendo, A., and Jonsson, G. K. (2015b). Quantifying biopsychosocial aspects in everyday contexts: an integrative methodological approach from the behavioral sciences. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 8, 153–160. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S82417

Radel, R., Sarrazin, P., Legrain, P., and Wild, T. C. (2010). Social contagion of motivation between teacher and student: analyzing underlying processes. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 577–587. doi: 10.1037/a0019051

Ramírez, S., and Justicia, F. J. (2006). El maltrato entre escolares y otras conductas problema para la convivencia. [Abuse between students and other problem behaviors for coexisting.]. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 4, 265–290.

Romera, F. J., Lucena, C., García, M. J., Alcántara, E., and Pérez-Vicente, R. (2015). “The role of ethylene and other signals in the regulation of Fe deficiency responses by dicot plants,” in Stress Signaling in Plants: Genomics and Proteomics Perspectives, Vol. 2, ed. M. Sarwat (Berlin: Springer).

Ruiz de Alegría, B., Basabe, N., Fernández, E., Baños, C., Nogales, M., Echebarri, M., et al. (2009). Cambios en las estrategias de afrontamiento en los pacientes de diálisis a lo largo del tiempo. [Changes in coping strategies in dialysis patients over time.]. Rev. Soc. Enferm. Nefrol. 12, 11–17.

Ryff, C., Heller, A., Schaefer, S., Reekum, C., and Davidson, R. (2016). Purposeful engagement, healthy aging, and the brain. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 3, 318–327. doi: 10.1007/s40473-016-0096-z

Salcedo, M. (2010). El aparato psíquico freudiano: ¿una maquina mental? [The Freudian psychic apparatus: a mental machine?]. Rev. Psicol. 1, 89–127.

Sánchez Ruiz, I. (2016). El Conflicto y la Mediación en la Comunidad Educativa. [Conflict and Meditation in the Educational Community]. Universidad de La Rioja, 8.

Sandoval, L., and Garro-Gil, N. (2017). La Teoría relacional: una propuesta para la comprensión y resolución de los conflictos en la institución educativa. [The Relational Theory: a proposal for the understanding and resolution of conflicts in the educational institution.]. Estud. Sobre Educ. 32, 139–157.

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 21, 1251–1275. doi: 10.1007/s11218-018-9464-8

Sutton, R. E. (2005). Teachers’ emotions and classroom effectiveness: implications from recent research. Clear. House 78, 229–234.

Trías, D. (2017). Autorregulación en el Aprendizaje, Análisis de su Desarrollo en Distintos Contextos Socioeducativos. [Self-Regulation in Learning, Analysis of Its Development in Different Socio-Educational Contexts.]. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid.

UNICEF (2011). Violencia Escolar en América Latina y el Caribe: Superficie y Fondo [School violence in Latin America and the Caribbean: Surface and background]. Available online at: http://www.unicef.org/lac

Ursu, S., Clark, K. A., Aizenstein, H. J., Stenger, V. A., and Carter, C. S. (2009). Conflict-related activity in the caudal anterior cingulate cortex in the absence of awareness. Biol. Psychol. 80, 279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.10.008

van Gaal, S., de Lange, F. P., and Cohen, M. X. (2012). The role of consciousness in cognitive control and decision making. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:121. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00121

Wang, W., Vaillancourt, T., Brittaing, H., McDougall, P., Kygsman, A., Smith, D., et al. (2014). School climate, peer victimization, and academic achievement: results from a multi-informant study. Sch. Psychol. Q. 29, 360–377. doi: 10.1037/spq0000084

Woods, C. (2010). Employee wellbeing in the higher education workplace: a role for emotion scholarship. High Educ. 60, 171–185. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9293-y

Woods, C. (2012). Exploring emotion in the higher education workplace: capturing contrasting perspectives using Q methodology. High Educ. 64, 891–909. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9535-2

Yip, J. A., and Côté, S. (2013). The emotionally intelligent decision maker: emotion-understanding ability reduces the effect of incidental anxiety on risk taking. Psychol. Sci. 24, 48–55. doi: 10.1177/0956797612450031

Zamorano, T. (2017). Autorregulación Emocional y Estilos de Afrontamiento en Pacientes Con Trastorno Límite de la Personalidad [Emotional Self-Regulation and Copingstyles in Patients with borderline personality disorder]. Master Thesis. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Keywords: emotional regulation, educational mediation, teachers, conflicts, interpersonal relations

Citation: Bonilla R. P, Armadans I and Anguera MT (2020) Conflict Mediation, Emotional Regulation and Coping Strategies in the Educational Field. Front. Educ. 5:50. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00050

Received: 13 August 2019; Accepted: 14 April 2020;

Published: 09 June 2020.

Edited by:

Abílio Afonso Lourenço, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Jesús-Nicasio García-Sánchez, Universidad de León, SpainJhonatan Steeven Navarro-Loli, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Peru

Copyright © 2020 Bonilla R., Armadans and Anguera. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pedro Bonilla R., cGJvbmlsbGFAdW5lZC5hYy5jcg==; cGVkcm8uYm9uaWxsYTVAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

Pedro Bonilla R.

Pedro Bonilla R. Immaculada Armadans

Immaculada Armadans M. Teresa Anguera

M. Teresa Anguera