- 1Office of the Executive Vice President for University Academic Affairs, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, United States

- 2Indiana University School of Social Work, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, United States

- 3Technical Communication, Department of Technology Leadership and Communication, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, United States

School attendance is important for student long-term academic and career success. However, in the U.S., our current practice often disenfranchises more at-risk students than it helps. Students slated for suspension and expulsion are often recipients of these practices. This manuscript offers a recommended change in how we frame student absenteeism and attendance using attendance markers and conceptual information by identifying the discrepancies, proposing options, and recommending a new way to actively leverage attendance data (not absenteeism data) for proactive student support. Particular attention is paid to how excused and unexcused absences and in-school suspensions are treated. An emerging pivot program, the Evaluation and Support Program, engages students while they receive school services, community support, and complete consequences is discussed as a possible, promising intervention.

Introduction

Failure to be present in the school environment can thwart development (Carroll, 2010) and seriously impair mental, cognitive, and socio-emotional outcomes (Kearney, 2008; Maynard et al., 2012; Heyne and Sauter, 2013; Gottfried, 2014) especially in the early schooling days. States have enacted legislation to guarantee that children in their formative years are properly educated to play a useful role in society (Gentle-Genitty et al., 2015). A discrepancy exists between the gray areas of the desire to educate children and the legal issues of the amount of education required. This discrepancy causes a struggle to define attendance and absenteeism for society, and more specifically, for teachers and attendance officers (Kearney, 2004).

The frames of how we currently look at these issues are focused on labels such as absenteeism and truancy. We can examine those frames more closely by starting with the changing definitions. For the purposes of this discussion, absenteeism is the study of the various forms or interplay of policies and procedures governing attendance ranging from presence to absence and all its corollary constituents, outcomes, interventions, and consequences (Gentle-Genitty et al., 2015; Heyne et al., 2018). Truancy is the label used for students who do not attend school when they are supposed to be attending, although there are nuances of what that looks like (see, ex. Gentle-Genitty, 2009; Maynard et al., 2012; Gentle-Genitty et al., 2015). Attendance is defined as the amalgamation of student behaviors, policies, procedures, and protocols used for capturing the formal presence or absence of a student in a registered school system by an official school officer or system (Gentle-Genitty et al., 2015). Because the field of school attendance and absenteeism is still emerging, recent efforts have focused not on attendance or absenteeism but instead on the complex relationships students have with their schools and families (Keppens and Spruyt, 2017) and various iterations and categorization of school attendance problems (i.e., school refusal, truancy, school withdrawal, dropout…), resulting in no consensus on these efforts (Heyne et al., 2018). Further, challenges rest in the inconsistent use and lack of consensus of definitions, and the variations result not in new terms, but in a categorization of the same behaviors according to their persistence, severity, and or avoidance (Gentle-Genitty et al., 2015; Heyne et al., 2018).

Studies show that students who are engaged and see value in education are less likely to experience truancy (Gentle-Genitty, 2009). Students who have absences and tardies in one semester are more likely to have ongoing absences and tardies (Gottfried, 2017). Similarly, students who do not attend and who have classmates who do not attend have a correlation between the absences and their individual grades (Marbouti et al., 2018). Timing has also been shown to have an effect on attendance or lack thereof (Marbouti et al., 2018).

Schools have mechanisms and protocols for collecting data on student absenteeism. However, the literature shows that schools are not adequately evaluating the effectiveness of their procedures for collecting and validating attendance data, resulting in unintended consequences for the students, schools, and communities. This manuscript offers a recommended shift to the view of absenteeism and attendance and recommends ways to leverage attendance data for proactive student support. An intervention may disrupt trauma, connect students to supports, establish positive relationships, and provide pivot pathways to student success, thereby reducing rates of suspension and expulsion.

Interventions

Interventions exist and have been contributing to the research in this area for a number of years (ex. Jenson et al., 2013). The Ability School Engagement Program (ASEP) mitigates risk factors for violence and anti-social behaviors (Cardwell et al., 2019). Another intervention included leadership binders and examined student attitudes toward school (Berlin, 2019).

Another recently proposed intervention, the Evaluation and Support Program (ESP), is an alternative to the expulsion and arrest method, placing the responsibility for re-engaging youth on the school and community. ESP is being used alongside a value system called CORE, which includes civility, order, respect, and excellence (CORE). This tiered method (Kearney, 2016) offers alternatives to the expulsion and arrest method and placing the responsibility for re-engaging the youth on the school and community prior to expulsion. The CORE-ESP intervention could begin changing the framing of absenteeism and includes workshops covering anger management, conflict resolution, drug education, and other similar topics and focuses on (1) priority evaluation and assessment with at least one parent, (2) treatment recommendations inclusive of education and therapy, and (3) at the end of completed tasks, a review hearing to evaluate educational placement. Interventions are focused on care and quality of life and can include the following:

• Anger Management, Academic Growth and Recovery, CORE Court, Community Service.

• Drug Education, Individual Counseling, Group Counseling, Mentoring.

• Truancy Intervention, Conflict Mediation, Restorative Justice.

• Apex Credit Recovery Pathway, Academic Reengagement, Career Builders & Parenting Workshops, Healing Hearts, Extended Day School.

The tiered model emphasizes a genuine concern and care for students by viewing the at-risk students as a member of the larger community and seeks viable alternatives to arrest and expulsion including

• Offer most interventions on school grounds to reduce unnecessary travel and cost.

• Use an Integrated System of Care framework to address the needs of the students and families while maintaining the safety of the learning environment.

• Decrease involvement of identified at-risk students into the juvenile justice system.

• Reduce out-of-school suspensions and disproportionality with school discipline to provide alternatives to arrest and expulsions through positive evidence-based school discipline practices.

• Ensure that when students are out of the classroom due to suspension or expulsion, a continuing education plan is in place and plans for adequate support and services are available upon re-entry.

• Reduce law enforcement referrals and arrests on school property, except where an arrest is necessary to protect the health and safety of the school community.

• Expand access to academic, mental health, and other community supports for students and their families.

• Increase academic success through implementing a plan toward social and academic re-engagement.

The impetus for this program was a decree by a local judge, which noted that the court perceived a pervasiveness in disenfranchising at-risk student populations. Disenfranchising can take many forms including the reporting structure for status offenses. The program goal is to strategically interrupt the school-to-prison pipeline through strong connections with community partnerships and by establishing a pre-screening consultant with the prosecutor's office. In addition, schools work with the local school hearing office to design parallel tracks and establish alternative pathways. This perspective takes an inclusive approach rather than the marginalized vs. mainstream approach currently held by most policy analysis frameworks.

Recommendations

Much research is needed in the area of addressing these complex issues. Reframing the beliefs and practices in the educational system is a place to start and can be founded on the belief that student bonds contribute to student success (Gentle-Genitty, 2009; Veenstra et al., 2010). For students who commit offenses that rise to the level of public safety concern and who experience trauma, the most stable factor in their lives is often school. Establishing strong connections with community resources can help keep at-risk students in school. Without this reframing, at-risk students may continue to pivot away from school and rarely return or graduate—often reinforcing the school-to-prison pipeline. Reframing with an attendance focus instead of an absenteeism focus disrupts trauma, connects students and families to support, establishes positive relationships, and provides pivot pathways to success.

Multiple Attendance Markers

Multiple markers can be used to track and report attendance including teacher records, attendance officer reports, test-taking outcomes, suspensions (in- and out-of-school), expulsions, attendance percentages or percentiles, discipline behaviors, excused and unexcused absences, and the student's overall presence. Presence can be used to mark the student's attendance every day, every half-day, or by period. Period or half-day tracking more effectively captures patterns and attending behaviors (Keppens and Spruyt, 2017). As the field of absenteeism has grown, methods for tracking processes and interventions have also grown. Beyond simply tracking presence or physical attendance, current research also considers tracking processes, interventions, classifications, and categorizations. Through the evaluation and analysis of the mental/cognitive and socioemotional as well as the physical attendance of the child in determining patterns of school attendance, much more targeted and structured outcomes have come to light.

Heyne and Sauter (2013) and Kearney (2008) share concerns on school refusal and other psychological underpinnings from tracking more than just physical attendance. When focusing on increasing rates of attendance, including more data can aid schools in more accurately responding to students' needs by treating them as humans vs. as mere numbers or targets and emphasizing a cognitive behavioral approach coupled with a mental health approach to absence and presence (Klerman, 1988). This approach is ideal because it surfaces early manifestation of daily symptoms that often result in negative outcomes.

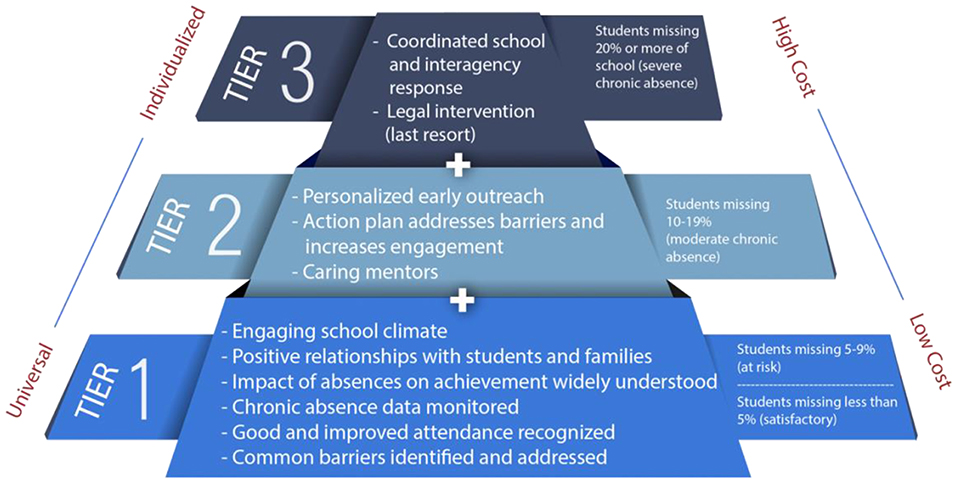

The tiered approach (Figure 1) divides students into three tiers reflecting the level of anticipated need for support (Kearney, 2016). Prevention, Tier 1, captures all students (those missing <5% are considered satisfactory, those missing 5–9% are considered at-risk). It reinforces value for attendance and provides structures for monitoring, clarifying, recognizing, educating, and establishing a culture of positive attendance. It is the universal prevention and education approach capturing 50–100% of students. This tier also includes the need to establish positive relationships with families. Early intervention is critical for success. Recognizing good and improved attendance, educating and engaging students and families about the importance of attendance, monitoring absences, and setting attendance goals helps establish a supportive and engaging school climate.

Figure 1. Assessing levels of student need—Implementing a model of tiered intervention (Kearney, 2016; Used with permission from Attendance Works).

Tier 2 captures the 11–49% of students who have a history of absence (missing 10–19% of school) or who face a risk factor that makes attendance tenuous. These students need a higher level of more individualized support in addition to the universal supports (Kearney, 2016). Tier 2 involves building caring supportive relationships (such as first period teachers Success Mentors, foster care, transportation) with students and families to motivate daily attendance and address challenging barriers.

Tier 3, the highest level of need, often captures the top 10% of the population who require more intensive and individualized responses. Their chronic absence is at a threshold of missing 20% or more of school in the past year or during the first month of school and/or facing risk factors. These are the most vulnerable students facing serious hurdles, and they may be homeless, involved in foster care, or involved in the juvenile justice system.

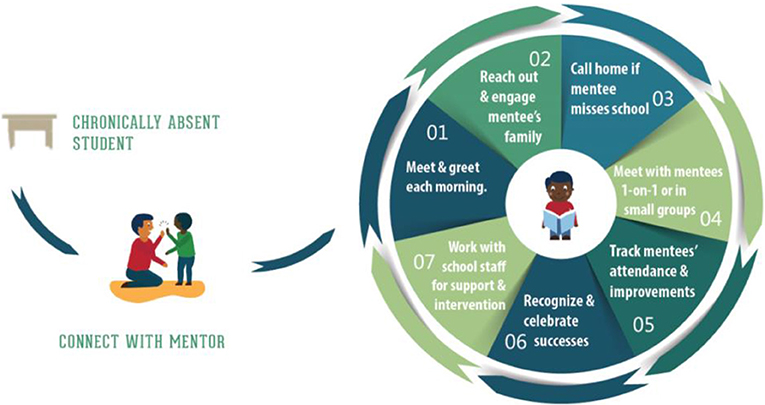

Core-ESP Connect-Success Mentor Model

The CORE Connect-Success mentor model (Figure 2) includes success mentors (teachers) who are advocates and motivators and encourage their 1st period students (mentees) during CORE time to attend school every day (Kearney, 2016). Teachers track the attendance of their 1st period students and form a relationship that lends to academic success through the ethics of care. Other periods are responsible for taking attendance also; however, sharing information through an open systems process strengthens the cadence and increases accountability for tracking at-risk students.

School districts can reallocate funds to invest in preventative and diversion programs to allow schools to access prevention and provider dollars, create partnerships to apply for local juvenile diversion and school safety and research grant opportunities, and seek out other federal community and private funding. Director of Student Services meetings can be held with representatives from various agencies (Department of Education, Department of Child Services, law enforcement, etc.) to foster a consistent dialogue to allow everyone to develop better processes. The result is improvements in defragmented services by integrating care with other community organizations, assessment of the overall mental health status of school districts, and the establishment of clear lines of communication to create new and improved reciprocal partnerships between schools and the courts that are more responsive to the needs of schools.

Other outcomes from coordination can include:

• Partnering with higher learning institutions to develop and evaluate effective risk assessment tools aimed at determining the high-risk offenders.

• Recruitment of enthusiastic human capital and other district resources to foster a sense of internal support.

• Training of key personnel in Trauma Informed Care and Brain Science to create Trauma Informed Care Schools within the school districts.

It is necessary to create a positive reinforcement behavioral alternative approach to expulsion and arrest. Students need to know they may successfully return to their schools armed with a better understanding of the connection between their behavior at school and that of the community, and consequences associated with their actions.

Discussion

Attendance-focused tracking can help to show care with immediate action for all involved, especially when the tiered levels of need and strategic responses are used. This focus on attendance instead of absenteeism may help foster a positive environment where students are better able to improve mental, cognitive, and socio-emotional outcomes (Gentle-Genitty, 2009; Heyne and Sauter, 2013; Gottfried, 2014, 2017).

Students and parents should understand policies, practices, and definitions (Kearney, 2004; Gentle-Genitty et al., 2015) to help them feel that the school cares. The child and their attendance should be celebrated, and a sense of school bond fostered (Gentle-Genitty, 2008, 2009; Veenstra et al., 2010). This bond can be leveraged for the benefit of all in protecting and fostering safety. The same is true when schools are able to use tracking attendance to establish a strategic method of collecting daily period data to establish patterns of student behavior. This is a shift in thinking. Tracking attendance should be a complementary responsibility to the larger task of ensuring we value and appreciate those who do attend and allow for them to bond and value their schooling. Thus, teacher engagement and classroom modifications should be norms.

What must be done? Much future research is needed in these areas. More intervention programs must engage teachers to look more deeply at attendance and the idea of paying attention to presence rather than absence. Teachers need to learn more about the contexts of their student absences. For example, why do students miss class when there is a substitute teacher? Are the students who are absent missing on specific days? For example, perhaps they are struggling and do not attend on days that include math classes. Do all the siblings in one family miss specific days because living situations cause late drop offs or missing the bus? We live in a schooling-dependent society where many parents work, and the school is the official place for their children to learn while they are gone. Students show up in the school environment every day and interact in complex relationships with teachers and administrators who are supposed to care, but often, few see what is really happening. The outcomes can lead to loneliness, suicide, bullying, and, sadly, school shootings. Students are being pushed to the edge simply because there is a stark change in patterns of behavior and engagement, and schools have no way to formally notify each other that something was off. More research in these areas and additional alternatives to attendance and engagement tracking may help.

Schools have not been effective focusing on absenteeism (Gentle-Genitty et al., 2015). Operationalizing attendance problems is not just the idea of excused and unexcused absences, as both are absences where the student is not ready and able to learn. It is about the same students being suspended repeatedly via in-school suspensions and marked absences. If the students are attending, regardless of the form, they must be counted as present. This factor alone will help us to gather more accurate data and decide which data is being tracked for patterns of behaviors and changes, and what actions we take with the data to protect all students and offer support to those most in need.

A tiered approach (Kearney, 2016) can help with school-wide interventions that benefit all and are individualized and intensified, working best in a culture of school attendance that values presence. This is a culture where typical factors of attendance are tracked and reported, discrepancies in what is tracked and used are shared, and negative patterns are disrupted early. There is no sense in collecting information if it will not be used to help the students. Focusing on attendance saves money, helps students graduate, and ultimately helps schools play the roles they were meant to play as bridges between families and communities to prepare students for their roles as responsible citizens.

This work offers only a glimpse into reframing the absenteeism focus to a focus on attendance and discusses other unintended consequences of attendance issues, including the effects on at-risk students. This list of recommendations and outcomes is not exhaustive, but suggestive and intended to inspire and expand current ideas about what positive interventions and preventions could be implemented in other schools. All of this is done with the hope of changing the attendance paradigm from being punitive to being a trauma-informed care approach that fosters positivity and support for reengagement. Perhaps this manuscript can expand the conversation to continue this important work more broadly.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This project and community partnership was made possible through countless agency and school collaborations and seed funds from the IUPUI Chancellor Bantz Community Fellowship Program. The Primary Author was the program's 2017 Community Research Scholar and grant recipient. In addition, support to capture the research work is attributed to IUPUI's Olaniyan Scholars—undergraduate researchers: Teresa Parker, Darius Adams, Timara Turman. Warren Township school staff, agency partners, and Prosecutor's Office, prosecutor Kristen Martin are also to be thanked.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Berlin, S. (2019). Improving Student Attitudes Towards School Via the Implementation of Leadership Binders. Master's Thesis, Goucher College School of Education, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Cardwell, S. M., Mazerolle, L., and Piquero, A. R. (2019). Truancy intervention and violent offending: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Aggress. Violent Behav. 49:101308. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2019.07.003

Carroll, H. C. M. (2010). The effect of pupil absenteeism on literacy and numeracy in the primary school. Sch. Psychol. Int. 31, 115–131. doi: 10.1177/0143034310361674

Gentle-Genitty, C. (2008). Chronic Truancy and Social Bonding: Role of Schools. Las Vegas, NV: International Association for Truancy and Dropout Prevention.

Gentle-Genitty, C. (2009). Tracking More Than Absences: Impact of School's Social Bonding on Chronic Truancy. Latvia: Lambert Academic Publishing. doi: 10.1037/e625252012-001

Gentle-Genitty, C., Karikari, I., Chen, H., Wilka, E., and Kim, J. (2015). Truancy: a look at definitions in the USA and other territories. Educ. Stud. 41, 62–90. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2014.955734

Gottfried, M. A. (2014). Chronic absenteeism and its effects on students' academic and socioemotional outcomes. J. Educ. Stud. Risk 19, 53–75. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2014.962696

Gottfried, M. A. (2017). Does truancy beget truancy?: evidence from elementary school. Elem. Sch. J. 118, 128–148. doi: 10.1086/692938

Heyne, D., Gren-Landell, M., Melvin, G., and Gentle-Genitty, C. (2018). Differentiation between school attendance problems: why and how? Cogn. Behav. Pract. 26, 8–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.03.006

Heyne, D., and Sauter, F. M. (2013). “School refusal,” in The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of the Treatment of Childhood and Adolescent Anxiety, eds C. A. Essau and T. H. Ollendick (Chichester, NM: Wiley), 471–517. doi: 10.1002/9781118315088.ch21

Jenson, W. R., Sprick, R., Sprick, J., Majszak, H., and Phosaly, L. (2013). Absenteeism and Truancy: Interventions and Universal Procedures. Eugene, OR: Ancora Publishing.

Kearney, C. A. (2004). “Absenteeism,” in Encyclopedia of School Psychology, eds T. S. Watson and C. H. Skinner (New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plemum, 1–2.

Kearney, C. A. (2008). An interdisciplinary model of school absenteeism in youth to inform professional practice and public policy. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 20, 257–282. doi: 10.1007/s10648-008-9078-3

Kearney, C. A. (2016). Managing School Absenteeism at Multiple Tiers. An Evidence-Based and Practical Guide for Professionals. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199985296.001.0001

Keppens, G., and Spruyt, B. (2017). Towards a typology of occasional truancy: an operationalization study of occasional truancy in secondary education in Flanders. Res. Pap. Educ. 32, 121–135. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2015.1136833

Klerman, L. V. (1988). School absence: a health perspective. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 35, 1253–1269. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36582-8

Marbouti, F., Shafaat, A., Ulas, J., and Diefes-Dux, H. A. (2018). Relationship between time of class and student grades in an active learning course. J. Eng. Educ. 107, 468–490. doi: 10.1002/jee.20221

Maynard, B. R., Salas-Wright, C. P., Vaughn, M. G., and Peters, K. E. (2012). Who are truant youth? Examining distinctive profiles of truant youth using latent profile analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 41, 1671–1684. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9788-1

Keywords: attendance, absenteeism, expulsion, suspension, excused absences

Citation: Gentle-Genitty C, Taylor J and Renguette C (2020) A Change in the Frame: From Absenteeism to Attendance. Front. Educ. 4:161. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00161

Received: 31 July 2019; Accepted: 23 December 2019;

Published: 21 January 2020.

Edited by:

Christopher Kearney, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, United StatesReviewed by:

Ricardo Sanmartín, University of Alicante, SpainAitana Fernández-Sogorb, University of Alicante, Spain

Copyright © 2020 Gentle-Genitty, Taylor and Renguette. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carolyn Gentle-Genitty, Y2dlbnRsZWdAaXUuZWR1

Carolyn Gentle-Genitty

Carolyn Gentle-Genitty James Taylor

James Taylor Corinne Renguette

Corinne Renguette