- 1Faculty of Education, Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada

- 2Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 3Faculty of Education, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

- 4School of Education, Communication, and Society, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

There has been a global trend toward increased accountability and assessment in schools over the past several decades. Across policy and professional standards, teachers have been repeatedly called to integrate assessment throughout their practice to identify, monitor, support, evaluate, and report on student learning. This professional capacity to integrate and utilize assessment to effectively facilitate student learning has long been characterized as teachers' “assessment literacy,” or more recently “assessment competency,” and “assessment capability”. Concerningly, research indicates that teachers generally maintain low levels of assessment knowledge and skills, with beginning teachers particularly underprepared for assessment in schools. This persistent finding is unsurprising as researchers argue that assessment has historically been a neglected area of study in teacher education programs. However, with the rise of accountability mandates, assessment is beginning to occupy a more prominent and necessary role in pre-service preparatory programs. However, analyzing and situating assessment education in relation to broader conceptions of assessment literacy remains necessary in order to effectively promote the assessment capability of beginning teachers. Likewise, understanding how assessment education and assessment literacy are shaped by the complex dynamics and larger teacher education frameworks and how they contribute to teachers' developing professional identities is essential in constructing a more comprehensive view of teacher preparation within and for accountability-driven systems of education. This paper analyzes teacher education policies, programs, and practices aimed at supporting initial teacher learning in assessment across four country contexts: Australia, Canada, England, and New Zealand. Bernstein's (1999) codes of classification and framing provide an analytic discourse for examining the vertical and horizontal messages about assessment that shape teacher capability in this key area of professional practice. In drawing on policy and teacher education documents and qualitative data (i.e., interview and teacher reflections) from across each country context, the paper concludes with five consistent and interconnected findings about the complex landscape for teacher preparation in assessment.

There has been a global trend toward increased accountability and assessment in schools over the past several decades. Across policy and professional standards, teachers have been repeatedly called to integrate assessment throughout their practice to identify, monitor, support, evaluate, and report on student learning (e.g., Brown et al., 2019; The Classroom Assessment Standards for PreK-12 Teachers; Klinger et al., 2015). Not only are data on student achievement from classroom and large-scale assessments proliferating at an incredible pace, but teachers are largely expected to analyse and utilize these data to meaningfully guide instruction for student development (Black and Wiliam, 2006; Earl, 2013). This professional capacity to integrate and utilize assessment to effectively facilitate student learning has long been characterized as teachers' “assessment literacy” (Popham, 2004; Brookhart, 2011; Xu and Brown, 2016), or more recently “assessment competency” (Popham, 2009; Herppich et al., 2018) and “assessment capability” (Absolum et al., 2009; Hill et al., 2010; Booth et al., 2014; DeLuca and Johnson, 2017).

Concerningly, research indicates that teachers generally maintain low levels of assessment knowledge and skills, with beginning teachers particularly underprepared for assessment in schools (MacLellan, 2004; Bennett, 2011; Xu and Brown, 2016; Herppich et al., 2018; Looney et al., 2018). This persistent finding is unsurprising as researchers argue that assessment has historically been a neglected area of study in teacher education programs (i.e., professional programs responsible for the education and certification of teachers; Stiggins, 1999; Shepard et al., 2005; La Marca, 2006; Taras, 2007; Xu and Brown, 2016). However, with the rise of accountability mandates, assessment is beginning to occupy a more prominent and necessary role in pre-service preparatory programs. As a result, a variety of assessment education models have emerged, yet with little research documenting their design or effectiveness. With growing attention to assessment education in pre-service and in-service contexts, there is an increased need to understand the frameworks of assessment and professional learning driving teacher development efforts globally.

At present, variable definitions and conceptions of assessment literacy, competency, and capability exist in the literature, each with potentially differing implications for assessment education. Over time there has been a shift from instrumental conceptions of assessment literacy, rooted in the acquisition of knowledge and skills (O'Sullivan and Johnson, 1993; Plake et al., 1993; Mertler and Campbell, 2005), toward a more socio-cultural understanding that links to teachers' developing professional identities (Adie, 2012; Scarino, 2013; Willis et al., 2013; Cowie et al., 2014; Xu and Brown, 2016; Looney et al., 2018). This shift has been stimulated by research that recognizes the complexity of implementing assessment knowledge within diverse contexts of learning and in relation to teachers' diverse training background and dispositions (Adie, 2012; Willis et al., 2013; Looney et al., 2018). Particularly, there is a growing recognition on the socio-constructivist nature of assessment (Shepard et al., 2005) and the influence of context on assessment learning (Xu and Brown, 2016). Analyzing and situating assessment education in relation to broader conceptions of assessment literacy remains necessary in order to effectively promote the assessment capability of beginning teachers. Likewise, understanding how assessment education and assessment literacy are shaped by the complex dynamics and larger teacher education frameworks and how they contribute to teachers' developing professional identities is essential in constructing a more comprehensive view of teacher preparation within and for accountability-driven systems of education.

Theorizing the Complex Dynamics of Assessment Capability

Assessment capability involves situated professional judgement, that is the ability to draw on learning and assessment theories and experiences to purposefully design, interpret, and use a range of assessment evidence in the service of student learning. Drawing on Bernstein's (1999) concepts, we theorize how student teacher assessment capability is represented within and across multiple contexts, and how the interrelationships and activities in these different contexts create different desirable identities through dominant forms of consciousness. Assessment, along with pedagogy and curriculum are interrelated message systems that communicate dominant cultural categories and reinforce relationships of power in classrooms, schools, and societies that student teacher must negotiate. Bernstein's (1999) codes of classification and framing, occurring within vertical and horizontal discourses provides a theoretical language to explain how messages about assessment capability are created and circulate in each of our four national contexts.

Where assessment capability is set apart as a specialized set of knowledge and practices, the identified knowledge is strongly classified—ruled, differentiated, and insulated from other knowledges. Specialist knowledge is maintained, reproduced, and legitimated through activities that preserve the boundaries of what is valued as knowledge, and thus the dominance of those people and institutions who set the recognition rules for that knowledge (Bernstein, 1990). When assessment capability is integrated alongside other knowledge, such as part of a teaching and learning cycle, it could be seen as weakly classified, and less able to be regulated. In a weakly classified framework for assessment learning, pre-service teachers engage in integrated learning experiences where assessment is part of, rather than separated from, the learning of other professional knowledges, and embedded within the relationships that structure teaching and learning contexts—social, cultural, curricular, and pedagogical.

Framing refers to how meaning is put together within a context, that is, how the communication of knowledge is organized and controlled. Choices around sequencing and pacing of the knowledge, and the way that the social order is regulated all are features of framing (Bernstein, 2000). The stronger or more explicit the framing, for example through accreditation reviews, explicit criteria or scaffolded assessment tasks, “the smaller the space for potential variation” (Bernstein and Solomon, 1999, p. 271). Weak framing can enable knowledge acquirers to have more apparent choice and control such as developing a feel for assessment quality drawing on peer discussion of exemplars, or observing a mentor teacher on practicum and making connections to university readings. Yet weak framing can lead to some beginning teachers not being able to access what is expected if they do not have a shared understanding of the underpinning knowledge discourses.

Classification and framing codes are part of broader vertical “official” and horizontal or “local” knowledge discourses. Vertical discourses are the coherent, explicit, hierarchically organized knowledge structures where specialized theoretical language is recontextualized, and acquired through graded performances. Vertical discourses are endorsed through standards of practice, certification requirements, and vision statements of graduates. Horizontal discourses, in contrast, are local, context dependent, and social, often created through practice of tacit or craft knowledge (Bernstein, 1999). Horizontal discourses often operate at the classroom level—through instructional moments—in which teachers and students re-interpret “official” knowledges within the diverse contexts of their practice. Assessment education within pre-service programs draws on multiple vertical and horizontal discourses with national and local policy, program structure, and pedagogical practices all informing assessment learning.

In this paper we consider data from vertical knowledge systems such as national policy contexts and teacher education program structures, as well as data from horizontal or local contexts for enactment that includes participant perspectives to consider how assessment capability is realized and recognized through teacher education programs. Our aim is not to precisely identify strongly classified knowledge that beginning teachers should know; such an activity has been conducted elsewhere (e.g., Klinger et al., 2015; DeLuca et al., 2016) through analysis and articulation of standards for practice. Instead, the aim of this paper is to begin to characterize the complex state of assessment education in four country regions by describing the influences across vertical and horizontal knowledge systems in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and England. These four countries have been selected for this study because, aside from the United States, they represent among the largest producers of English-speaking teachers in the world. Given the significant mobility of English-speaking teachers working across countries internationally, understanding how assessment literacy is supported and promoted in initial teacher education within these countries holds international relevance. That said, we recognize the importance and value of continuing to map the preparation of assessment education across other jurisdictions and countries, both English and non-English speaking, and position this study as an initial cross-country investigation.

Methods

For each of the four focal countries, we examine the policies, programs and practices of assessment education in teacher education as a way of acknowledging that assessment capability is situated within complex systems involving both strong and weakly classified knowledges and vertical and horizontal discourses (Bernstein, 1999). Due to local variations in how teacher education programming is offered and access to documents and data, each country has leveraged data unique to its context to most effectively describe teacher education policies, programs, and practices.

Policies

In the subsequent section of this paper, we describe policies within each country that describe both the assessment context for teacher assessment literacy, as well as the policies that shape teacher education and assessment learning. A variety of policies documents in each context have been utilized drawn primarily from publicly accessible government and institutional websites (e.g., university websites, teacher accreditation agencies). These documents have been discursively interpreted to contextualize teacher candidate assessment learning in relation to Bernstein's (1999) classification and framing concepts.

Programs

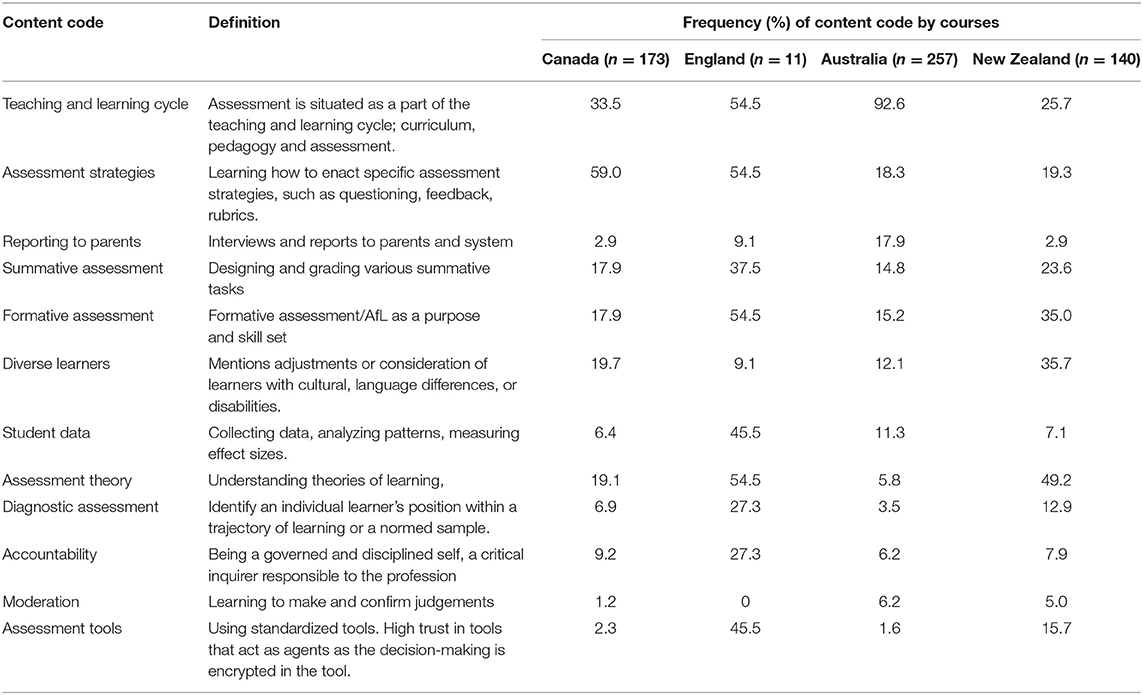

Following our review of the policy context for pre-service teacher assessment capability in each context, we investigate provisions for assessment learning at the programmatic level. In each country, course descriptions were obtained from a select number of teacher education programs and analyzed using a consistent framework. Course descriptions in each context were obtained from university public websites (i.e., information for students regrading course title, length, and description). Universities in each context were selected to reflect geographic distribution and variability of size of initial teacher education programs. In Australia, 17 universities were selected and 357 courses that mentioned assessment in their title or description were identified across teacher education program in those universities. In Canada, 12 universities were selected that had 2-year post-graduate teacher education programs with 173 courses identified that mentioned assessment from those programs. In England, 6 universities were selected that offered a post-graduate certificate of education (PGCE; a 1-year post-degree course) with 11 complete program descriptions identified that mentioned assessment. Importantly, given the structure of programs in England and the fact that assessment was not taught as a standalone course in any program, program session descriptions were used as the unit of analysis rather than course level descriptions. In New Zealand, 140 course descriptions were analyzed that mentioned assessment from six universities.

Using a document analysis template, data were gathered from program websites related to (a) program information (i.e., length, course load, practicum length, cohort size); (b) provisions for and descriptions of explicit assessment courses (including course descriptions, number of credit hours, and whether or not course(s) was elective or required); and (c) descriptions of courses that addressed assessment (including course description, number of credit hours, and whether or not course(s) was elective or required). Beginning with the Australian course descriptions, two researchers inductively identified assessment concepts/topics across descriptions to create a codelist with definitions. Researchers in each context applied the codelist to their course descriptions with latitude to create additional emergent topics codes. Coding reliability was established through a process of inter-coder agreement, in each context, in which at least two researchers coded a subset of course descriptions until agreement was reached (Garrison et al., 2006; Campbell et al., 2013). Code data were reported as frequencies (calculated by dividing the rate of frequency of a code by the total number of coded datum points and multiplied by 100 within each contexts' dataset) to enhance comparability of analysis across contexts.

Practice

In the final section of findings, we examine the resulting practices of program provisions toward assessment learning within each context drawing on data from unique key informants in each context. Each context examined assessment learning from a different key informant perspective.

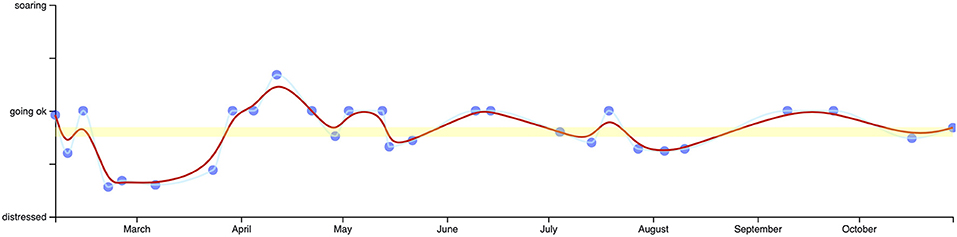

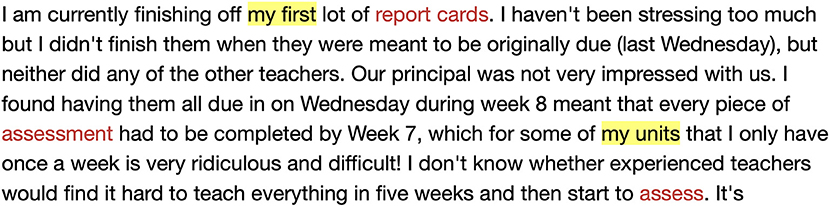

In Australia assessment learning was examined through the perspective of 17 beginning teachers using a reflection protocol. In total, 535 digital reflections were collected from these teachers over several months using GoingOK.org software. Specifically, teachers were invited to indicate “how they were going in their first year of teaching” on a 100-point slider scale (0 = distressed, 50 = going ok, 100 = soaring). Entries accumulated over time and were visible to the beginning teacher as a plotline (see Figure 1 as a sample). For each reflection, teacher were also invited to narrate their experience through descriptive texts. Overall, the dataset is a collection of rich, point-in-time reflections about the day-to-day experiences of beginning teachers (Willis et al., 2017; Crosswell et al., 2018).

Narrative data were analyzed quantitatively using Reflective Writing Analytics that enabled patterns in the group data to be visualized and assessment keywords (in red) to be cross-referenced to metacognitive reflective writing cues (highlighted in yellow in Figure 2; Gibson, 2017). These highlighted entries were then analyzed qualitatively.

In Canada, perspectives on assessment learning were obtained from 25 teacher educators from 12 pre-service programs from across Canada who participated in semi-structured interviews (up to 1 h). Of the 25 educators, 14 instructed standalone assessment courses with the remainder teaching curriculum or professional studies courses. Questions were designed to provide teacher educators with the opportunity to discuss how they approached assessment learning in the courses they instructed and their perception of assessment learning of teacher candidates' outside of their class. Sample interview questions included: At the end of your course, what do you hope students will have learned about assessment? Are there key individuals or opportunities for learning that shape assessment education in your program? Interviews were transcribed verbatim and were inductively analyzed using a standard thematic analysis process (Patton, 2014). Two raters from Canada analyzed a subset of data (i.e., three interviews) to ensure rater reliability, with an overall inter-rater agreement of 92% after discussing any differences in coding.

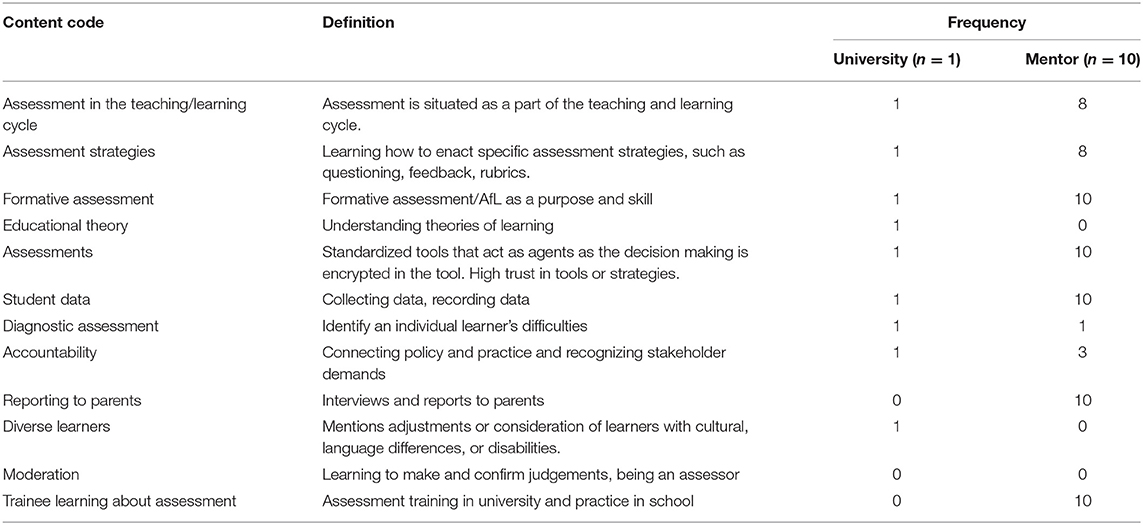

In England, perspectives on assessment learning were obtained from 10 mentor teachers, who supervise pre-service candidates while on practicum, through semi-structured interviews (upto 1 h). All mentor teachers were affiliated with one of the universities involved in the program review analysis. The interviews were completed toward the end of the course post-practicum. The intention of the interviews was to collect mentors' perceptions of the pre-service teachers' assessment learning, as well as data on how schools and pre-service programs enculture and educate pre-service teachers into appropriate classroom assessment practices. Interview questions focused on: (a) How mentors interpreted assessment competency? (b) What support and opportunities were provided to help pre-service teachers understand and carry out assessment? and (c) How did pre-service teachers fit in with school assessment procedures and practices? Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Data were first analyzed deductively using the same coding system constructed for the analysis of the policy documents. One code (i.e., student data) had to be re-described because it had a formulaic approach in schools rather than the more process driven ideas in the handbook. Further, an additional code learning about assessment was generated that was specific to the interview data because all the mentors kept referring back to assessment ideas introduced in the university part of the course vs. those practiced in school. Data were then inductively analyzed for emergent themes. Three specific themes were identified by mentor teachers regarding the assessment learning of pre-service candidates: (a) assessment for learning, (b) marking, and (c) tests. Coding of data was checked by comparison of two researchers with blind-coding of three of the transcripts. A 78% inter-rater agreement was achieved after moderation and discussion.

In New Zealand, analysis of perspectives toward assessment learning were based on a previous study (Cowie and Hill, 2011; Hill et al., 2014) of 25 teacher educators from four universities. Via focus groups, teacher educators were asked to elaborate on their understandings of assessment, what assessment topics and approaches they aimed to develop in their pre-service teachers, and their perceptions of the contextual influences on student teacher learning about assessment. Participating teacher educators coordinated compulsory courses where the course outline included explicit mention of assessment as a learning outcome. In all, 25 teacher educators participated in the focus groups. Focus group data were transcribed verbatim and inductively analyzed using a standard thematic analysis process (Patton, 2014). Multiple raters analyzed a subset of data with discussion amongst raters about codes to ensure rater agreement.

While data on practices from each context is different; taken together, it presents a multiple-perspective view on how assessment education provisions are influencing practice and assessment learning within and through pre-service program components (coursework and practicum).

Policy Contexts for Pre-Service Teacher Assessment Capability

Despite quite different policy foundations, the rise of the accountability movement in each country has led to similar impacts in teacher education programs with assessment beginning to occupy a more dominant role. An analysis of school and teacher education policies in each country provides a description of the framing discourses (i.e., vertical to horizontal; Bernstein, 1999, 2001) shaping teacher education programs and assessment learning within each context.

Australia

Teacher education in Australia occurs mostly through 4-year Bachelor, or 2-year Master of Teaching programs, offered as 400 courses from 40 higher education providers. Historically the six states and two self-governing territories have had slightly different approaches to assessment. National assessment, curriculum, and professional standards for teachers have brought greater standardization, and significant changes to teachers' everyday assessment practices (Adie and Willis, 2016; Van der Kleij et al., 2018).

Assessment in national policy is defined in terms of assessment for, as, and of learning (Ministerial Council for Education Training Youth Affairs, 2010), however most of the policy and support for teacher assessment has focused on assessment of learning (Van der Kleij et al., 2018). Teachers navigate between national, state, and local assessment priorities in their day-to-day assessment work, drawing on multiple assessment literacies (Willis et al., 2013) and multiple assessment roles (Alonzo, 2016). Teachers are under increased scrutiny with assessment data causing a backwash toward more scripted curriculum in many schools (Klenowski and Carter, 2016), and many teachers internalizing national assessment data as an indicator of their effectiveness (Thompson and Mockler, 2016). In practice teachers draw on assessment capabilities such as critical inquiry, reflexivity, and collaboration to align their assessment practices with varying policy demands, conceptions of knowledge, curriculum, learning and teaching activities (Wyatt-Smith and Gunn, 2009; Adie and Willis, 2016; Looney et al., 2018; Willis and Klenowski, 2018). Assessment understandings are formally articulated in policy through Standard 5 of the Australian Teacher Professional Standards, that emphasizes assessment strategies, how to provide feedback, make consistent and comparable judgments, interpret student data and report on student achievement (Australian Institute for Teaching School Leadership, 2011). A graduate teacher is expected to “demonstrate understanding” and achieve greater mastery as they move through their career to be proficient at “using” assessment, to “develop” approaches when highly accomplished, and “model exemplary practice” and “lead evaluations” as lead teachers.

Expectations of pre-service teacher assessment capability are also directly influenced by policy that regulates the training courses, where assessment operates as both a curriculum focus, and accountability lever. Initial Teacher Education (ITE) programs are accredited by the AITSL. Recently revised standards (Australian Institute for Teaching School Leadership, 2018) are having a profound impact on the design and governance of pre-service teacher education courses (Bourke, 2019). From 2018, candidates are assessed at entry for suitability, and before graduation provide assessment evidence about their “positive impact on student learning,” through a Teacher Performance Assessment (Australian Institute for Teaching School Leadership, 2016, p. 45). Additionally, teacher education courses need to demonstrate the “post program impact of graduates… on student learning” (Australian Institute for Teaching School Leadership, 2016, p. 45). Assessment of pre-service teachers, and their teacher education institutions, is being directly linked to assessment of school students in a quality assurance discourse linked to ideas of classroom readiness, standards, and effectiveness (Churchward and Willis, 2018). In Bernstein's (2001) terms, there has been a strengthening of the classification of assessment capability through regulatory policies, that is, assessment is being set apart as a vertical knowledge discourse that is systematically structured and hierarchically organized.

Canada

Education in Canada falls under provincial jurisdiction with teacher education programs preparing candidates to teaching within specific K-12 provincial systems of education. While each of Canada's 13 provinces and territories has its own educational policies, there are striking similarities in educational priorities, including assessment frameworks and mandates for teachers (Volante and Ben Jaafar, 2008; DeLuca et al., 2017; Jang and Sinclair, 2017). Consistently, K-12 teachers are encouraged to use assessment for various purposes in their classrooms including for diagnostic, formative, and summative purposes (Jang and Sinclair, 2017). Increasingly, policies recognize the plethora of assessment methods that can be leveraged to document student learning and invite teachers to engage in regular, formal and less formal, reporting of student progress. All classroom assessment in intended to be standards-based (i.e., linked to provincial curriculum expectations) and relates to both academic standards and learning skills, which are reported separately on provincial report cards. Each province has its own large-scale testing program, with varying structures and degrees of influence on student grades (Klinger et al., 2008).

Accreditation of teacher education programs in Canada is conducted by provincial governments or provincial teacher governing bodies (e.g., Teacher Regulation Branch; Ontario College of Teachers, 2019). Each accrediting body uses a variety of evidence to certify that each program upholds and prepares teachers to meet provincial standards of practice. Teacher candidates are most often recommended for certification upon successful completion of their teacher education program, without additional testing. Teacher education programs are consistently 2-years in duration across provinces and largely function as post-degree programs. There are also concurrent education programs in which teacher candidates begin their program directly after secondary school alongside their undergraduate degree. Provincial standards for the teaching profession vary in specificity; for example, as related to assessment, the Ontario College of Teachers' Standards of Practice indicates that teacher should: “apply professional knowledge and experience to promote student learning. They use appropriate pedagogy, assessment and evaluation, resources and technology in planning for and responding to the needs of individual students and learning communities” (Ontario College of Teachers, 2019). In more depth, the Alberta Teacher Quality Standards (Alberta Government, 2018, p. 5) states, “A teacher applies a current and comprehensive repertoire of effective planning, instruction, and assessment practices to meet the learning needs of every student.” The Alberta Standards (p. 5) further articulates that teacher should:

Applying student assessment and evaluation practices that:

• accurately reflect learner outcomes;

• generate evidence of student learning to inform teaching practice through a balance of formative and summative assessment experiences;

• provide a variety of methods for students to demonstrate their achievement;

• provide accurate, constructive and timely feedback to students; and

• support the use of reasoned judgment about the evidence used to determine and report the level of student learning.

Over the past decade, research on Canadian teacher education programs has noted inconsistent learning outcomes for teacher candidates, specifically within assessment education courses, and pronounced variability of teacher candidates' assessment knowledge and attitudes. Poth (2013) surveyed 23 teacher-education institutions across four Canadian provinces, the vast majority offering required courses in classroom assessment. However, none of the 12 intended learner outcomes identified across the programs (e.g., develop communication skills for reporting achievement) were shared across all programs. Even within a single teacher education programs, there can be variability between assessment education courses, suggesting that while there is a dominant policy discourse on K-12 assessment within provinces, there remains variable learning and interpretations of the policy. Furthermore, teacher candidates within the same cohort have significant variability in knowledge and attitudes toward assessment (Volante and Fazio, 2007; DeLuca and Klinger, 2010; Coombs et al., 2018). Despite the presence of consistent teacher accreditation practices, evidence suggests a fairly weak classification of assessment knowledge as prescribed by teaching standards within Canada, which may contribute to variable assessment education models and outcomes for teacher candidates.

England

Over the last two decades, schools in England have become data driven with many influenced by the need to produce summative performance data for monitoring standards and evaluating school effectiveness. This means that data collection and regular assessment is well-practiced in schools. At the same time, assessment for learning has been encouraged in UK schools with national implementation programs and government incentives for schools to focus efforts on embedding such practices. The dilemma for the classroom teacher is how to reconcile these two different approaches to assessment. On the one hand, teachers have to regularly report on student attainment and demonstrate that their students are on track to succeed in national examinations. At the same time, they are encouraged to be more formative in their assessment practices, for which evidence is often required, increasing the accountability burden on teachers.

In recent years, alongside changes to the National Curriculum in England, new forms of assessment were demanded to align with the changes of content and demands of the curriculum (Harrison, 2016). Instead of measuring and reporting achievement, teachers, and schools were asked to focus on how secure each student's knowledge, understanding and skills were at key points in their schooling, suggesting a competency and mastery learning approach. The common assessment system in most state schools, prior to 2015, had been based on a system of National Curriculum levels. This system was introduced by the Task Group on Assessment and Testing (TGAT) in 1988 and was defined as a concept of progression shown through a sequence of up to 10 levels spanning the range of performance from ages 5 to 16. While the level system was eventually dropped for the 14–16 age group, the system developed and evolved for the 5–14 age range and became a set of eight bands used to measure a child's progress against other children nationally.

The initial purpose of these levels was for mapping progression. While TGAT had intended that the levels system be used for statutory national assessments, over time, levels also came to be used for regular in-school assessment to monitor students' progress toward expected levels. This change distorted the purpose of in-school assessment, particularly day-to-day formative assessment, as the focus became much more of which level students had reached, rather than focusing on assessment for learning. From 2016, schools were informed by government that they would no longer be reporting attainment using National Curriculum levels, but rather schools would have to set up their own systems for assessing students. One difficulty was the conflicting pressures in trying to make appropriate use of assessment as part of classroom teaching on a daily basis, while at the same time collecting assessment data to use in high stakes evaluation of individual and institutional performance. All state schools, at primary and secondary level, now needed to demonstrate that they could report on:

• how well their students have learned;

• what progress students are making year-on-year;

• that all students are on track to meet expectations; and

• how tailored support programs are being used for individuals.

Schools have responded in a range of ways to the new assessment initiatives, with some still in transition from the former level system or attempting to disguise retention of the former system by simply replacing levels 1–8 as A–H, while some schools have introduced new assessment approaches. For example, at elementary level, many teachers are assessing against age related expectations of performance, with learners either being “at,” “working toward,” or “exceeding” performance. At secondary, there is a greater variety of approaches, many of which link assessment in lower secondary school with that used in the final 2 years of study leading to the national GCSE examinations at age 16. The changing context of school assessment has put pressure on teacher education to respond by preparing teachers both for traditional and more contemporary approaches to assessment.

New Zealand

Formative assessment has been prioritized within New Zealand assessment policy since the late 1980's (Department of Education, 1989; Ministry of Education, 1994) with policy documents also acknowledging the role of summative assessment within classroom assessment, and as necessary for reporting and accountability purposes The 1993 New Zealand Curriculum Framework (Ministry of Education, 1993) states that formative assessment should be a priority, with this emphasis reiterated and elaborated on in the 2007 New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007). The section dedicated to assessment includes the assertion that the “primary purpose of assessment is to improve students' learning and teachers” teaching as both student and teacher respond to the information it provides (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 39). Student self-assessment is included as an aspect of the key competency of self-management. The 2007 documents explicitly acknowledge that different groups (parents, government, etc.) each have a role student assessment. The priority given to assessment for learning is reiterated in the Ministry of Education position paper: Directions for Assessment in New Zealand (Absolum et al., 2009), and reinforced in the 2011 Ministry of Education Position Paper: Assessment (Ministry of Education, 2011). This document states:

All young people should be educated in ways that develop their capacity to assess their own learning. Students who have well-developed assessment capabilities are able and motivated to access, interpret, and use information from quality assessment in ways that affirm or further their learning (p. 5).

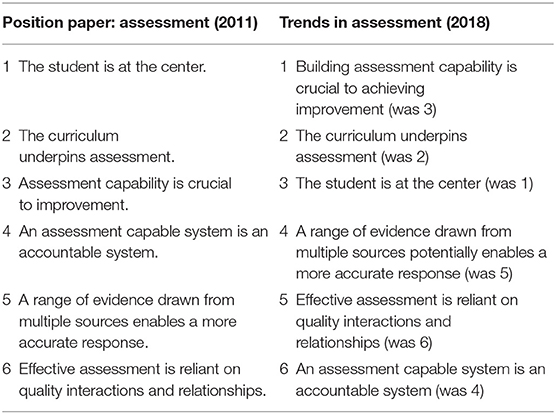

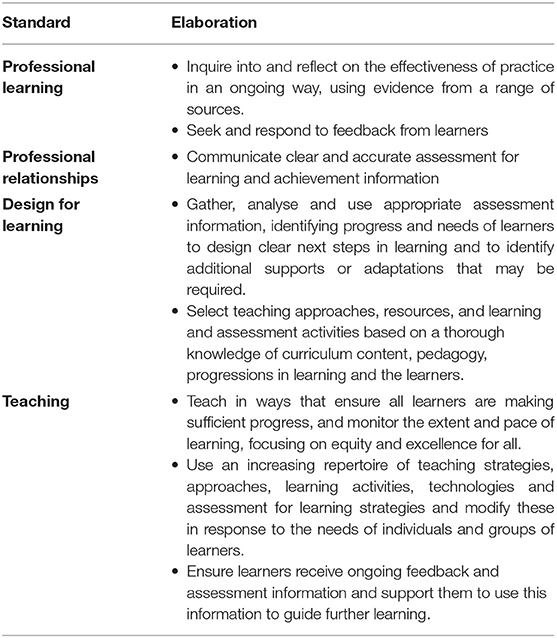

The 2011 document sets out seven principles that emphasize that effective assessment is a key component of quality teaching and learning and that it plays an important role in system improvement. The recently published Trends in assessment: An overview of themes in the literature (Hipkins and Cameron, 2018) reasserted the importance of students at the center of the assessment processes, that the priority should be on assessment in the service of learning and that parents have an important role to play in this (see Table 1 for comparison between priorities of Position Paper, 1999 and Trends report, 2018).

Turning to national assessments, since 1995, national monitoring has been accomplished through light sampling of Year 4 and 8 students, with different curriculum areas assessed over a multi-year cycle. Students respond to individual and group, paper, and practical tasks. Teachers administer, mark, and moderate student responses, creating an important source of professional development on assessment for New Zealand teachers (Gilmore, 1999). New Zealand, however, had no comprehensive compulsory system of national monitoring until 2010 when the National Standards system was introduced. National Standards focused on reading, writing, and mathematics and relied on an Overall Teacher Judgment (OTJ) to evaluate student achievements. Teachers developed their OTJs by synthesizing a range of evidence. Yet in 2019, the National Standards were revoked.

This brief review of New Zealand's assessment policy context point to the influence of policy layering (Ball and Junemann, 2012) in creating vertical and horizontal discourses of assessment with impacts on the social-relational, material conceptual and ideational context for assessment and hence the development of beginning teachers' assessment capability.

Initial teacher education programs in New Zealand offer 3-year bachelor degree programs and one-year graduate diploma and Master of Teaching and Learning programs. Since 2007, initial teacher education providers have been responsible for ensuring their graduates met the requirements of the Graduating Teacher Standards: Aotearoa New Zealand (New Zealand Teachers Council, 2007). The seven Standards are grouped under three overarching categories: (a) professional knowledge, (b) professional practice, and (c) professional values and relationships. Each category could be interpreted as including mention of assessment but the Professional knowledge and Practice categories include an explicit mention of the use of evidence. In June 2018 new teaching standards were promulgated: Our Code Our Standards (Education Council, 2018). These apply to both pre-service and practicing teachers with pre-service teachers expected to meet the Standards “in a supported environment” on graduation from an initial teacher education program.

The Code has four aspects of commitment—to the teaching profession; to learners; to families and whanau, and to society. There are six “Standards,” each with a number of “Elaborations,” that are not legally binding. The Standards are “purposely designed at a high level so every practitioner can apply them to suit the context they are working in.” Four of the Standards have “elaborations” that indicate a focus on assessment (see Table 2).

Table 2. Assessment standards from Our Code Our Standards (Education Council, 2018).

Within the “Professional learning” standard teachers are to (i) Inquire into and reflect on the effectiveness of practice in an ongoing way, using evidence from a range of sources, and (ii) Seek and respond to feedback from learners. The “Professional Relationships” elaboration focuses on clear and accurate communication; the “Design for learning” standard focuses on the selection of teaching, learning and assessment activities and the generation and use of assessment information to identify progress and design clear next steps or supports for learning, and the “Teaching” standard elaborations focus in on “equity and excellence for all,” responsiveness and student access to feedback and information that will allow them to direct their own further learning. At this time the meaning and practice of the Standards and of “in a supported environment” is not clear. Adding complexity, initial teacher education program approval requirements are shifting from a review of program content or student teacher opportunity to learn (what we are aspiring to) to an audit of the assessment tasks being used to determine graduates' achievement of the Standards. The proposition behind these developments is that the government needs to have confidence that pre-service teachers have achieved the Standards and are able to perform key teaching tasks from their first day of teaching, which reflects a move to strong framing in Bernstein's terms.

Pre-Service Program Provisions for Assessment Education

Programmatic provisions for assessment education (e.g., explicit coursework in assessment and embedded assessment learning) for each country were examined by systematically analyzing publicly accessible teacher education program documents (i.e., handbooks, program outlines/calendars, and course descriptions) in each context. Table 3 suggests the relative explicit address of each assessment area in comparison across the countries.

Australia

While there were differences in emphasis between institutions related to assessment content and topics, there were mostly similar patterns across institutions. Few units were “standalone” units where assessment was the main teaching focus. The majority of assessment topics were taught within curriculum units, for example: “activities in workshops and on school visits are intended to increase a mathematical knowledge base… but they also focus on principles of instruction and assessment.” Some institutions taught about assessment in the context of a professional experience unit, with some embedding assessment learning, curriculum and practicum foci in the one unit (see Table 3). There was a significant increase in the number of units that mentioned assessment after the new accreditation requirements for 2018, however the proportions of the approaches did not change, with assessment embedded most often as a topic within curriculum units.

The most frequent assessment topics (see Table 3) were assessment strategies, reporting to parents, formative, and summative assessment. Identifying how assessment could support students with diverse needs, using student data, moderation, concepts of accountability, and assessment theory were less frequently mentioned. Several assessment concepts often overlapped in the unit descriptions. These broad indicators do not reflect all of what the teacher educator would teach about assessment, but do indicate that pre-service teacher assessment capability is taught in a highly integrated and pragmatic approach across pre-service programs in Australia, even with the increasingly strong policy framing from the national accreditation requirements.

Canada

Through the examination of selected pre-service programs across Canada, findings indicate that all teacher education programs had a similar structure of assessment education and offered a standalone course in classroom assessment and/or evaluation, the majority of which were mandatory. Eight programs offered assessment and evaluation courses that were streamed by either teacher qualifications (e.g., Primary/Junior or Intermediate/Senior) or area of specialization (e.g., English as a second language, exceptional learners). Courses descriptions of standalone assessment courses differed greatly in the specificity of the assessment topics addressed. While some courses provided only from a very general description (e.g., “Introduction to a variety of approaches to evaluating student learning”), others were far more detailed [e.g., “Students explore the concept of a balanced assessment program that integrates formative and summative assessment practices. Students develop skills in creating a variety of assessment instruments (e.g., observation check-lists, tests, rubrics, portfolio)”].

All teacher education programs offered non-assessment courses (e.g., curriculum courses or professional studies courses) that embedded classroom assessment and/or evaluation content. An embedded approach to assessment curriculum was evidence by the inclusion assessment and evaluation content in course descriptions. While many curriculum courses addressed assessment topics within a specific domain (e.g., “Examination of instructional and assessment strategies, models of inquiry and critical thinking, and approaches to curriculum integration relevant to the junior division; special focus on the Arts and Language Arts Ontario Curriculum and other pedagogical resources”), others situated classroom assessment within a more general professional studies courses (e.g., “Establishing and maintaining a positive and safe learning environment in the classroom is explored and concepts in instructional planning and evaluation introduced. A variety of approaches based on research and theory will be considered and applied.”).

While the teacher education programs selected represent roughly a quarter of all programs in Canada, consistent findings, specifically in regards to assessment education, indicate similar program structures and models of assessment education. This finding points toward a positive trend to include explicit assessment courses in pre-service programs, yet it appears that the content across these courses maybe less consistent. Course descriptions highlight variable learning objectives for pre-service teachers, spanning assessment theory, practice, application, and philosophy.

England

In comparing PGCE teaching programs, there were mostly similar patterns across the six universities. Assessment was not taught as a standalone course but was embedded within the main program as part of preparation for developing classroom skills and learning about policy, curriculum, and teaching practice. References to assessment were generally listed as “including a focus on assessment principles and practice.” Only one institution had explicit sessions that were entitled assessment, with six half-day workshops: Assessment for Learning 1 (Questioning and Talk), Assessment for Learning 2 (Feedback and Marking), Summative Assessment (Tests and Examinations), Self and Peer Assessment, Using Assessment Evidence to Map and Track Progress, Making Sense of Assessment Classroom Practices. On first reading of the six PGCE programs, there seemed to be similarity between the six institutions in terms of their assessment approach overall; however, coding of assessment content within the programs revealed a different picture (see Table 3).

The top four codes were (a) assessment in the teaching and learning cycle, (b) assessment strategies, (c) formative assessment, and (d) educational theories. These codes all appeared as major ideas that the six courses valued and used as a basis for their programs. Formative assessment tended to be called Assessment for Learning but the emphasis within programs was on the role of assessment in informing teaching and learning. This more active use of assessment was echoed in descriptions of Collecting and Using Assessment Data and in the use of Assessment Tools within five of the institutions. Diagnostic Assessment was evident in three of the programs and often linked in with either Formative Assessment, Assessment Tools, or Collection and Use of Assessment Data. What was less clear were the purposes and practices associated with these tools and how inexperienced teachers were trained and encultured into using these effectively as part of their assessment practices.

Accountability was specifically referred to in terms of its shaping of assessment practices and its effect on whole school systems and teacher workload in three universities, although it was also described in the background of all six with many systems being articulated as “taking part in high stakes assessment systems.” Surprisingly, the codes of Reporting to Parents and Diverse Learners appeared only once and in the same program handbook and Moderation was not evident in any program handbook and yet the system in England has been predicated on standardization of assessment with a recent focus on schools introducing new systems to monitor progression through schooling.

This separation of theory and practice is heavily influenced by policy implementation and nationally enforced changes in practice and has a strong influence on how pre-service teachers learn to assess. The multiple pressures from vertical knowledge systems (Bernstein, 1999) like government policies, and horizontal knowledge expectations introduced by practicum mentors, lead to the notion that preparatory programs do not enable pre-service teachers to fully engage in and understand the requisite assessment knowledge and skills.

New Zealand

Our scan of publicly available Bachelor of Teaching and Master of Teaching/Master of Teaching and Learning primary course and program outlines from six universities (conducted in January 2019) found that, on the whole, knowledge of assessment such as assessment tools, data analysis, and data use often appeared to be assumed or implied as part of good pedagogical practice rather than an explicit focus. Documents from across the universities emphasized pedagogy and learning with embedded assessment principles. Of the 10 publicly available program outlines and 140 course descriptions reviewed, there were only four formal courses where both the unit title and course description reflected an explicit and primary focus on the development of teacher assessment capability or data literacy. For example, a Master's course titled Working together to accelerate learning included a unit descriptor:

Students will undertake a supervised investigation that involves advanced analysis of existing data sets and the drawing of robust and trustworthy conclusions with a view to accelerating learning. The processes involved when making judgments to accelerate learning and promote positive relationships with students will be critically examined.

All program outlines, however, included course descriptions (total 34 courses across all programs) where assessment featured as part of the teaching/learning/assessing cycle, something which is consistent with the NZC framework. This linkage was most noticeable in curriculum-based courses. In an undergraduate curriculum course focused on primary mathematics and statistics, the necessity for building knowledge in assessment processes and use could be inferred as pre-service teachers are required to “design quality learning experiences for diverse learners” and understand questions and concepts related to “learning progressions.” More explicitly in this course description, pre-service teachers would explore the “theoretical models of teaching, learning and assessment” that constitute effective teaching practice.

There was inconsistent emphasis on assessment across programs in practicum courses, with descriptions able to be read as more or less explicitly highlighting the need for development of assessment knowledge and practical expertise. For example, an undergraduate practicum course outlined an exploration of how pre-service teachers might “manage complexities of teaching professionally in order to create and sustain purposeful learning environments and enable achievement for all learners.” In some descriptions, the mention of assessment was more noticeably absent or perhaps taken to be integrated within the practicum experience itself. For example, a practicum course described the course as “designed to deliver through practical application and first-hand experience in classrooms, the necessary curriculum and pedagogical content required of primary teachers.”

Within the course descriptions reviewed there was very little direct mention of assessment task design, assessment decision-making and moderation, or learning progressions. Similarly, there was very little mention of skills of reporting/communicating clear and accurate achievement information with the same true of summative assessment. The development of assessment for learning strategies and knowledge could be assumed in courses promoting pre-service teacher learning about student diversity and achievement where evidence-based practices were to be used to measure or evaluate teaching effectiveness. Ideas of assessment for learning were often linked to a focus on the development of pedagogical content knowledge and curriculum design. For example, a paper titled: “Promoting achievement for diverse learners” aims to explore “diversity in the New Zealand context and its implications for teaching and learning,” “consider strategies to address identified underachievement,” and “examine practices that create effective teaching and learning environments for diverse/all learners.”

There was very little and inconsistent explicit mention of other formative strategies such as diagnostic assessment although these also could potentially be inferred, as in a Masters course: “assessment as is informed by the New Zealand Curriculum.” One undergraduate course made specific reference: “Students will examine in-depth, current and innovative learning teaching practices, formative assessment approaches and examine the role of inclusive and relational practices.” Even less common was mention of the inclusion of students themselves as self- or peer-assessors and decision-makers in their next learning steps. Overall, while ideas of assessment were prevalent across the programs and course descriptions reviewed, it could be concluded that there was a lack of alignment and coordination, with inconsistent treatment and application of assessment theory and skills offered.

Through our policy analysis and interrogation of current program and course descriptions, we see both consistent commitments but also an ever-changing assessment landscape in New Zealand. Our work points to (a) an analysis of how assessment has been incorporated into curriculum documentation, (b) the strong focus within assessment policy on assessment for learning and the move toward and then away from more formalized and public reporting of student achievement via National Standards, (c) a longer-term and more seamless vision of teacher learning and development implicit within Our Codes, Our Standards for teachers, (d) the potential tensions and advantages inherent in the proposed shift from opportunity to learn to outcomes for initial teacher education program audit purposes, and (e) the extent to which current assessment education as reflected in institutional documentation could be viewed as integrated with or embedded in teaching as a holistic practice or judged as underdeveloped due to a lack of explicit coursework.

Practices of Assessment Learning

In order to understand how policies and programs shape the practice of assessment learning within teacher education programs, participant perspectives from each country were sought to highlight the experiences of pre-service teachers, early career teachers, teacher educators, and practicum mentors.

Australia

Drawn from data of teachers' digital reflections during teaching practice, assessment featured as a recurring topic. The teachers confidently used data to monitor student progress, initiated new assessment processes, and felt knowledgeable in how assessment worked within curriculum and pedagogy. However, they also felt unprepared for how to fit assessment into their workload, with assessment being commonly associated with feelings of “being tired all of the time.” Concerns about reporting to parents featured quite often and weighed heavily, for example:

Prior to and during report cards, I was 'distressed'…as can be expected during this time! It felt like I was writing multiple uni assignments all over again. Plus with the added stress of my Principal and parents reading it.

Assessment capability therefore included being able to manage the emotions associated with being judged, and managing time and energy.

Using diagnostic and formative assessment to be responsive to student needs was also a persistent concern. A beginning teacher who was struggling to teach a student with disabilities and who was engaging in challenging behaviors reflected that she knew that she should use formative assessment to identify what his learning needs were, but still felt out of her depth:

I know it will take time to get to know him and get to know strategies which work best with him, but these early days are still hard. There are no support staff trained/specialized with working with students with disabilities/high learning needs. The school is having to train up a teacher aide, so at the moment it feels like I'm on my own. No university course can prepare you for this! I only had 1 subject about teaching students with disabilities. So I am feeling out of my depth. I know this is a great experience for 1st year out, and will only make me stronger.

Assessment capability was entangled with classroom management, managing the resources available to the beginning teacher in the context, and the emotions of feeling uncertain. University learning was of some help but more development was needed. What was apparent throughout this entry, and many others, was the high level of metacognitive reasoning, and agentic reframing by the beginning teacher that turned challenges into learning experiences.

Assessment capability was not represented as strongly classified rather more highly integrated with personal experience than policy discourse suggests. Managing emotions, tiredness, and the assessment relationships with parents, support staff, principals, were all associated with assessment capability, and are elements that do not feature in policy statements. Charteris and Dargusch (2018) emphasize that pre-service teacher assessment capability transcends a checklist approach, and is an ongoing development that involves bodies and minds in assessment decision-making in-situ. This idea is being explored in follow-up research in all four contexts with pre-service teachers writing reflective entries using GoingOk during their assessment learning.

Canada

Through interviews with teacher educators across selected teacher education programs in Canada, four theme were identified that reflected practices of assessment learning in initial Canadian teacher education: (a) limited time for assessment learning, (b) inconsistent messaging, (c) focus of learning, and (d) key pedagogies.

Limited Time for Assessment Learning

Despite the fairly consistent structure for assessment education in Canadian teacher education programs, teacher educators consistently articulated that there was limited time for assessment learning within their programs. A common sentiment expressed by one instructor was, “we're well-aware that when they leave the 6-week course, they don't have any other assessment course in their program and that they all want and need more assessment.” This recognition was in light of high demands from teacher candidates for more assessment education. Anther instructor commented, “teacher candidates sign up for that [assessment/evaluation course] in droves every single time it's offered.” As evident in both the Canadian program document analysis and in what teacher educators noted, additional learning opportunities in assessment beyond coursework (e.g., workshops) appear almost non-existent across programs.

Inconsistent Messaging

Teacher educators, particularly those that instructed assessment education courses, noted the challenge of inconsistent messaging related to assessment across program components. Some teacher educators discussed the primary purpose of assessment as supporting student learning, “the primary purpose of assessment and that is moving learning forward” (TE10), “Assessment is primarily to improve learning” (TE23); while others discussed the primary purpose of assessment as sorting students by performance, “[assessment] differentiates those students who are doing well and those students who are not doing well” (TE19). Teacher educators also noted that assessment was treated differently across courses within their programs and between the program and teacher candidates' practicum experiences: “it seems that in a teacher candidate's feedback, that assessment is not consistently addressed in all course” (TE17) and “students don't experience or feel that we're being consistent” (TE11).

Suggestions to address inconsistent messaging were two-fold. First, a “top-down” approach was suggested, in which faculty administration or department leadership would work to promote consistency. One instructor acknowledged, “our department head has discussion groups on… students' perspectives on assessment and how we can make sure that we're better aligning ourselves the practices with the provincial policy guidelines” (TE13). The second approach was through informal interactions amongst teacher educators to ensure similar assessment learning experiences for teacher candidates, as expressed by one instructor: “where [another professor at our institution] get together and kind of talk strategy about how she's going to do the elementary and I do the secondary” (TE6).

Focus of Learning

In examining course descriptions and in asking teacher educators to describe the focus of learning in their courses, we noted two dominant groups. One group, composed primarily of teacher educators that instructed standalone assessment courses, focused on shaping teacher candidates' approaches or attitudes toward classroom assessment, as exemplified in the following statements: “assessment is the start of a conversation” (TE8); “[Having teacher candidates] recognize that all assessment is subjective, and to embrace that and use that as a way to differentiate the assessment for different students” (TE11), and “we want them to be able to identify and reflect on their beliefs and understandings of our assessment” (TE2). While the second group, primarily teacher educators who embedded assessment topics within general education courses, focused on developing teacher candidates' assessment practices. Teacher educators in this group noted learning goals such as, “I want them to be able to effectively create assessment tools that align with good assessment practices” (TE23); and “I want them to show me how they're understanding those practices, giving me examples of where they've used those practices, and then analyzing for me how those practices are going to inform their pedagogical decision making” (TE17).

Key Pedagogies

In describing their approach to supporting teacher candidates' learning about assessment, teacher educators noted the importance of relational pedagogies including, (a) discussing their assessment attitudes and explicitly modeling of assessment practices, and (b) building explicit connections to K-12 teaching contexts. Modeling was evident across instructors with statements such as: “I'm trying to model a range of assessment methods and phases, both in terms of the product [teacher candidates] hand in but also the kings of activities we do in class” (TE12); “we do a lot formative assessment, learning intention, co-creating criteria, self-peer assessment, building student ownership, working with learners with their setting goals, and making plans and reflecting on their learning” (TE21); and “[I try] to model in our class what they're going to have to do out in the field” (TE9). Building connections to K-12 assessment contexts was also articulated as a key pedagogy for assessment learning. As an example, one instructor commented, “I always have examples of how the policies are playing out in practice” (TE10).

Although not always available, many teacher educators explicitly connected their curricula to assessment policies: “every single section of [assessment policy document] is assigned [for reading]” (TE12). Many teacher educators also included pedagogical activities and assessment tasks that involved engaging directly with assessment policies; for example, “we talk about the provincial policy …the end product is a letter to the Minister of Education” (TE7) and “[weekly discussions] are focused on a particular reading, either from research or from policy documents or supplementary ministry document” (TE13). However, not all teacher educators felt comfortable drawing on provincial assessment policies as those not in the field of assessment were less confident with their knowledge and familiarity with the policies: “I do kind of resist some of those provincial policies” (TE18).

In analyzing teacher educator data, it is clear that there are strong commitments to promoting assessment skills and knowledge of beginning teachers but that learning experiences are highly variable and shaped by the local context (i.e., teacher educator, teacher education program, and program experiences), reinforcing a horizontal discourse despite a dominate pressure, as articulated through needing more time for assessment education, to promote greater capability in beginning teachers. Hence, evident in the Canadian context, is a complex vertical (systemic K-12 assessment policies and practices, and more loosely teaching standards) and horizontal (i.e., teacher education contexts and relational pedagogies) system of assessment discourse that shapes initial learning in assessment.

England

In order to explore practices of assessment learning in England, the views of teacher mentors were solicited. Interestingly, analysis of mentor interviews revealed a different picture as to the priorities of assessment learning to that of the analysis of the program handbooks (see Table 4).

Comparison of the two datasets highlight the different interpretations that the mentors assign to their roles in supporting pre-service teachers as they develop their assessment capabilities. Digging into the interview data revealed three specific areas mentors target when supporting student teachers in assessment: (a) assessment for learning, (b) marking, and (c) tests. In all three of these areas, mentors suggested that an understanding of the purposes and processes of these aspects were introduced in the university course and then developed through practice in the school. They conceptualized their role as evaluating the development of these assessment practices rather than enculturing new teachers into understanding and building relevant assessment practices or in coaching how they might do these assessment tasks well.

Assessment for Learning

All mentors stated that pre-service teachers came to them well-versed in assessment for learning practices and quickly adopted the strategies and practices favored within their school. One strategy, in particular, was highlighted (i.e., “green pen”), which provided opportunity for students to respond to teacher marking and to improve or correct work. What was less clear was how pre-service teachers worked out what to comment on in student work and how these comments should be framed. Mentors seemed surprised that pre-service teachers might need support in providing feedback to students. None had shared the way that they provided feedback on student work with their pre-service teacher, despite this being a training suggestion in the university handbook and none had checked how feedback had been provided by their pre-service teacher. One mentor commented, “I would have known if this had been problematic because the kids wouldn't have been able to ‘green pen’ and also when it came to the test.” Mentors also did not associate evidence of attainment, arising during learning, as data that they should report, believing that such evidence could not be used for important decisions such as grouping students or reporting progress, preferring test data as a means of doing this. There was a clear demarcation between assessment evidence used to inform teaching and learning, and assessment data reported to other stakeholders or used to inform decisions.

All mentors reported that their pre-service teacher designed activities and questions that encouraged classroom talk. One mentor felt that there had been an overemphasis of assessment on-the-fly in the university part of the course and reported that “this left them wide open to problems in school book trawls,” which is an accountability-driven exercise where senior staff look through student exercise books to judge the amount and style of marking and feedback of individual teachers.

Marking

The mentors generally recognized assessment competency as whether the pre-service teachers marked regularly or were able to utilize school marking practices. Four of the schools did comment-only marking and not assigning grades, one school gave a grade that summarized and reflected the work completed over the 2-week period and the rest generally gave grades and brief comments on most pieces of work. When asked about how pre-service teachers made decisions about their comments or grades when they marked, the following factors were suggested–percentage or number of correct/incorrect points or calculations; how the student had performed in relation to peers in the class; how the student had performed in relation to their ability; individual student effort. None of the mentors referred to particular incidents or aspects of work that indicated that specific types of feedback would be needed. In all cases, the mentors felt that the skill of marking developed over time and that the pre-service teachers had made particular progress in this aspect of assessment in the final 4–6 weeks of the teaching practice. One mentor commented,

It's something they pick up and learn to do on the job. When they start, it takes them maybe 3 h to mark a set of books. They would never manage that next year as an NQT with five or more classes. By the end, they realized what they need to look for and just mark that rather than pondering about what to comment on or what to write.

When pressed to discuss what aspect of the student work received a grade or comment, mentors reported that each teacher had their own style of assessment and that there was no consensus on how teachers assigned judgements about quality to individual pieces of work. A similar finding was reported by Cizek et al. (1995) in their study of pre-service teachers' assessment practices. Such an approach does not help pre-service teachers enter the community of practice and suggests that their assessment capability develops in relation to their own experiences of marking rather than being apprenticed into such practices.

Tests

All teachers reported the use of end-of-topic tests every 3–4 weeks, with each test lasting around an hour and consisting of 15–20 structured short answer questions. pre-service teachers were provided with tests that were common for that school. The test questions were generally selected, by whichever teacher had written the scheme of work for that topic, from Testbase (a compository of national SAT/GCSE questions). Mark schemes were also provided with the test but decisions about deviations from the mark scheme were left to individual teachers. All teachers felt their tests must be good assessment instruments because they were constructed from external examination questions. They were unaware of what constructs were being assessed other than topic content and also the range of marks achieved for particular tests both for their own classes and across the age group. Three of the mentor teachers admitted that some of the tests were more difficult than others but saw no problem since all students did the same tests. Again, the way that pre-service teachers were inducted into using these was through experience.

In all three aspects (assessment for learning, marking, and tests), mentors felt that initial ideas about assessment were introduced in university-based sessions while school practice provided opportunity for development. In no case, did mentors report any assessment training practices specifically, but rather that they observed and judged competency in-situ, although without specific or consistent criteria across contexts, consistent with promoting a horizontal discourse of knowledge creation (i.e., “craft” knowledge; Bernstein, 1999). Such an approach means that pre-service teachers make sense of assessment practices experientially rather than being apprenticed into them. Progress in this area may therefore be out of kilter with other aspects of their teaching or with vertically framed assessment knowledge (Bernstein, 1999).

New Zealand

Drawn from focus group data of teacher educators, four themes related to practices of assessment learning were identified in the New Zealand context: (a) Assessment should be part of learning and teaching action in the classroom; (b) the need for teacher educators to shift student teachers' thinking from summative to “next steps” thinking, (c) the need for multiple sources of evidence, and (d) assessment is making judgments against standards.

Assessment Should Be Part of Learning and Teaching

The teacher educator focus groups identified a range of sites and purposes for assessment but in line with longstanding New Zealand policy and practice they depicted the classroom teaching and learning as the key site for assessment (94 comments/4 universities). Assessment was construed as central to responsive teaching; a process whereby a teacher identified what students knew or could do, and what sense they were making within an activity. The emphasis was on the need for assessment to benefit students as exemplified in the following comments: “We look at assessment as a reason for you doing your planning so it's got to be integral to everything you do. That you don't understand assessment unless you understand how the child is going to benefit in some way.” A concern with getting to know children and being aware of the growth in their understanding and skills was often entwined with discussion of the positive potential of assessment. One teacher educator noted: “If the students [pre-service teachers] weren't able to talk about a child and notice growth or notice change or just notice the child, to me even that at a very basic level…I'd be really upset if they couldn't just see the child and see the change.” Congruent with this there appeared to be a commitment, shared within in each group, to focusing on what a child could do rather than what they could not. One group discussed this orientation as a “non-deficit” view of children.

Moving From Summative to “Next Steps” Thinking

Conversations emphasized the importance of teacher educators shifting pre-service teachers' thinking from summative to “next steps” thinking (79 comments/4 universities). From their perspective this shift involved supporting pre-service teachers to think about assessment when they were planning lesson so that they could interact with children during the teaching and learning process. One teacher educator explained this as a process of, “Moving teacher candidates away from assessment as an activity (e.g., a test) … looking at how we build it into their lesson planning and how they can use it to inform the next steps in learning.” Another stated, “We get them (teacher candidates) to collect data, evidence about the child in reading, writing…and they use that information to identify next teaching steps, the sort of things they're going to do and incorporate it in their planning when they're in control in the classroom.”

The Need for Multiple Sources of Evidence

Within the foci detailed previously teacher educators endorsed the need for teachers to gather evidence through formal and informal means and to use more than one source of evidence when making a judgment about a child's learning (50/4): “one piece of evidence may not be enough.” One teacher educator stated, “I think for me the most devastating thing would be if they didn't use a range of different methods in their classroom.” This point was linked with a concern that pre-service teachers might jump to superficial but far-reaching conclusions based on, for example, the surface features of student performances, especially with those children who are presumed to be less able. The teacher educators emphasized the importance of helping pre-service teachers develop a sophisticated and nuanced understandings of evidence and of the children they were teaching so that they were better prepared to notice and recognize subtle evidence of student learning.

Assessment Is Making Judgments Against Standards

Other commentary related to the need for strong curriculum knowledge for teachers to be able to interpret and respond to children's ideas and actions (21 comments/4 universities). This point was summed up in the following two comments”: I think content knowledge is absolutely crucial so they can notice and respond” and “They don't know where to go next if they don't have the content.” There was very little discussion about how pre-service teachers can learn about how to use assessment information to take learning forward or about assessment quality drivers such as validity and reliability, or matters such as test item construction and national and international testing regimes.