- 1Department of Education, Université du Québec en Outaouais (UQO), Gatineau, QC, Canada

- 2Service de Soutien à la Formation (Teaching & Learning Service), Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada

The habits of university students today have changed drastically thanks to the technological tools at their disposal and the access to an enormous amount of information on the web, which they can copy, use, and reference in their assignments. Unfortunately, the line has become blurred about what is and what isn't permitted by their professors and their universities, sometimes resulting in students committing plagiarism. Research has shown that many students arrive at university unprepared. They lack the informational skills needed to research and choose the information relevant for their assignments, the writing skills necessary to properly integrate the found information with paraphrases or quotations, or the referencing skills to provide their sources in order to write their assignments with integrity. In this research, we aimed to examine how professors in six different universities viewed their role in the teaching of academic integrity by means of educating students on informational, writing, and referencing skills as well as teaching their students about plagiarism prevention. Forty-nine professors and lecturers were interviewed about their role in the teaching of various skills. Results show that there were four types of information searching assignments required by the professors: searches for published information, searches for authentic contextual information, searches limited to the handouts given to the students and no information research required. Seven roles emerged from the data, from the Ambassador professor who takes full responsibility for the teaching of skills to prevent plagiarism to the Detached professor, who completely dissociates from this responsibility for different reasons. Recommendations are presented on how to encourage professors to adopt the four roles of the “Integrity Ambassador”: the intermediary who promotes the discovery of all services available to students; the awakener, who encourage students' appreciation of learning for the sake of learning; the accompanist, who guides and supports students with direct interventions in class so that they develop the skills and knowledge necessary to write their assignments with integrity; and finally, by being a model, the Integrity Ambassador cultivates a climate of integrity in class and in the university, showing how one can lead an academic life with integrity.

Introduction

The habits of university students today have changed drastically thanks to technology (Bryant, 2017). They have more tools at their disposal (Goldman and Martin, 2016) and have access to an enormous amount of information on the web (Anderson, 2016), which they can copy, use and reference in their assignments. Students have also developed techniques for teamwork (Purcell et al., 2013), sharing information (Davidson and Goldberg, 2009), and writing collaboratively (Allen and Jackson, 2017; Walsh and Borkowski, 2018). Unfortunately, the line has become blurred about what is and what isn't permitted by their professors and their universities, sometimes resulting in students committing academic fraud (Huang, 2017).

Plagiarism is on the rise all over the world (Dee and Jacob, 2012; Janssens and Tummers, 2015; Amiri and Razmjoo, 2016) and constitutes a major problem for many reasons. Firstly, students are not learning what they should (Adam et al., 2017) since plagiarism leads to surface learning rather than deep learning (Wheeler and Anderson, 2010). Secondly, students who plagiarize have an unfair advantage over other students who accomplish their work with integrity. Thirdly, the validity of the diplomas awarded (Vargas, 2018) and the education system are compromised. Finally, research has shown that students who plagiarize during their studies tend to commit other fraudulent actions once out of school (Lovett-Hooper et al., 2007; Guibert and Michaut, 2011).

Newton's research has shown that 65% of undergraduates “simply did not recognize that plagiarism constitutes ideas as well as words” and do not know how to prevent it (Newton, 2016). King and Brigham (2018) mention that many students arrive at university unprepared. They lack the informational skills needed to research and choose the information relevant for their assignments (Siddiq et al., 2016), the writing skills necessary to properly integrate the found information with paraphrases or quotations (Wojahn et al., 2015), or the referencing skills to provide their sources (Gravett and Kinchin, 2018).

Peters (2015) in her research has been examining the digital scrapbooking strategies students use when they are writing their assignments. She is of the opinion that training students to properly use digital scrapbooking strategies would reduce the number of plagiarism cases in universities (Peters et al., 2019). Various digital scrapbooking strategies are used in tandem with informational, writing and referencing skills to find information (use key words, analyse, and evaluate information), use it ethically while writing (quote and paraphrase) and reference it appropriately (in the text and in a bibliography). Peters' results show that while students expect to receive training in regard to these strategies in university, many of their professors expect them to have already mastered the strategies and skills necessary to write their assignments with integrity. There is clearly a divide between students' and professors' expectations which can results in a lack of student training in the three skills needed to write ethically and unfortunately in students being caught for involuntary plagiarism.

Professors have mixed feelings about how to deal with plagiarism (Coalter et al., 2007). Many of them don't want to play detective or have to spend hours looking for plagiarism in their students' papers (Doró, 2014) while others simply don't report the cases of plagiarism they do detect because of lack of administrative support (Thomas, 2017). Also, many professors are unaware about what precisely constitutes plagiarism and don't know how to detect it (Wheeler and Anderson, 2010).

As a result, the education system is faced with a major problem: too many students plagiarize when instead they “need to learn the importance of academic integrity and understand that it is not just a hoop to be jumped through, but is integral to intellectual and personal growth” (Wheeler and Anderson, 2010). Eaton and Edino (2018) explain that there are different methods to teach academic integrity in courses of various disciplines.

In this research project, we aimed to examine how professors in six different universities viewed their role in the teaching of academic integrity by means of educating students on informational, writing, and referencing skills as well as teaching their students about plagiarism prevention.

Conceptual Framework

Academic Integrity and Plagiarism

Academia seems much more preoccupied with defining plagiarism than with defining academic integrity. A quick Google search yields 27,400,000 results about the definition of plagiarism, but only 1,130,000 results for the definition of academic integrity. Macfarlane et al. (2014, p. 340) published a literature review on academic integrity and underlined how the concept “is widely used as a proxy for the conduct of students, notably in relation to plagiarism and cheating.” However, the authors of that review focused on the academic integrity of professors, explaining how integrity is associated with virtues such as humility, pride, and respect.

The International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) specifies six fundamental values for student academic integrity: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, courage (International Center for Academic Integrity, 2014). Fishman (2016) definition specifies that academic integrity is “acting in accordance with values and principles consistent with ethical teaching, learning, and scholarship” (p. 8). So, for students, this means learning the content by doing the work required by their professors, honestly and fairly, without engaging in plagiarism (Adam et al., 2017).

Plagiarism has been defined as the use of someone else's words or ideas as one's own in order to gain something. In a student's case, this gain would translate into better grades (Muthanna, 2016). Numerous authors have examined the types of plagiarism (Walker, 1998; Curtis and Vardanega, 2016), its causes (Rettinger and Kramer, 2009; Horbach and Halffman, 2019), or its consequences (Ho, 2015; Kashian et al., 2015). Some studies look at the issue from the students' perspectives (Childers and Bruton, 2016; Cronan et al., 2018), others from the professors' (Thomas and De Bruin, 2012; Bruton and Childers, 2016). However, most of the literature has focused on punishing perpetrators of plagiarism rather than preventing it. In order for students to know how to prevent plagiarism, they need the knowledge and skills to produce assignments with integrity.

Informational, Writing, and Referencing Skills as Cross-Disciplinary Skills

Informational skills are automatically used by students from all disciplines when they need information to write their assignments (Piette et al., 2007; Boubée, 2011). These skills are much more than just the ability to search for information. They involve critical thinking and analysis (Simonnot, 2007; Harris, 2013), as well as proper interpretation of the information for one's needs in order to select which information will be used (American Association of School Librarians, 2007). A study by Roy (2009) indicated that many students would like to be trained to better evaluate the relevance, value, and credibility of information they find online. Umunnakwe and Sello (2016) specify that the large amount of information available to students has inhibited their creative, critical thinking, and problem-solving abilities.

Students need these informational abilities as well as their writing skills if they are to succeed academically (Woodard and Kline, 2016) regardless of the discipline they are studying. Writing is an intellectually demanding activity (Fleuret and Montésinos-Gelet, 2012), and is today more complex than ever with the omnipresent possibility of copying and pasting now acknowledged to be a spontaneous habit of students (Rinck and Mansour, 2014) as well as for most writers. Haapanen and Perrin (2017) break down writing from sources into three subprocesses: decontextualization, contextualization, and textualization. In the first subprocess, students find information and remove it from its original context. In the second subprocess, students integrate this information in their own writing, contextualizing it in the new text. The last subprocess involves harmonizing the initial information found with the new text, i.e., rendering it in the same linguistic form. This writing process is not necessarily linear (Quinlan et al., 2012) and may vary for each student (Stapleton, 2010) since they may use different strategies (De Silva and Graham, 2015) and technological tools (Lenhart et al., 2008).

Referencing in all disciplinary academic writing is compulsory (Gravett and Kinchin, 2018) and just like informational and writing skills, it also requires critical thinking (Monney et al., 2019). While students are writing their text, they must keep track of the information found (Association of College Research Libraries, 2015; Martin and Lambert, 2015) and reference the authors they quote or paraphrase directly in their text (Hirvela and Du, 2013). The consulted sources must also be included in the bibliography, usually situated at the end of the text and handed in with the assignment (Couture, 2017). The proper use of quotes and paraphrases will show how the student has built his argumentation and will also both display and prove the depth of his completed research (Duplessis and Ballarini-Santonocito, 2007; Vardi, 2012). However, according to Hutchings (2014), many students are scared of committing plagiarism when referencing, owing to their lack of referencing skills (Zimitat, 2008; Shi, 2012; Adam et al., 2017).

Informational, writing and referencing skills are not linked to domain-specific curriculum; students in all university programs are required to use these skills, making them transversal or cross-disciplinary skills (Song-Turner, 2008). The term “academic literacies” have been emerging and have a common agenda according to Parker (2011, p. 5), this being to generate students who can write “within institutional and disciplinary conventions… and see themselves as contributors to the intellectual community.”

Professors' Roles in Teaching Academic Integrity

Little research has been done in examining what actions professors take to promote academic integrity to their students (Tippitt et al., 2009; Löfström et al., 2015). Some researchers have analyzed professors' attitudes toward plagiarism (Coalter et al., 2007; MacLeod, 2014) or how they deal with integrity in their specific disciplines (Adkins and Radtke, 2004; Halbesleben et al., 2005; Mayhew and Murphy, 2009). However, to our knowledge, closely examining the specific skills and knowledge taught by professors to promote academic integrity has never been undertaken—the goal of this article.

Professors' Attitudes Toward Plagiarism

A study by Thomas and De Bruin (2012, p. 21) showed that most professors “acknowledged the seriousness of student academic dishonesty and the role that they as faculty play in influencing students' moral development.” Conversely, a non-negligible proportion of their participants did not agree with this statement and felt that it was not their responsibility to teach about academic integrity.

This attitude is unfortunate since Broeckelman-Post (2008) has found that professors who discuss specific expectations for assignments in regard to source attribution and plagiarism have a positive impact on students' behavior. The researcher's results “showed that talking about plagiarism was correlated with one-fifth less academic misconduct-level plagiarism by students” (Broeckelman-Post, 2008). If all professors talked to their students about integrity in their studies, plagiarism cases could be reduced on campuses all over the world.

Roles Professors Adopt When Teaching Integrity in Their Disciplines

Gallup has constructed the Gallup Workplace Audit survey (GWA) to measure employee engagement in different workplaces and countries (Harter and Agrawal, 2011). Using this instrument, Maheshwari et al. (2017) measured the levels of professors' engagement in higher education in India. Their results indicate that one third (34%) of professors are “involved in, enthusiastic about and committed to their work and contribute to their organization in a positive manner. They work with passion and they drive innovation and move their organization forward” (p. 123). They are the engaged professors. A little over half (52%) of the professors are not engaged, and are not passionate about their work while the rest (14%) are actively disengaged and unhappy at work (Maheshwari et al., 2017).

Kuh (2003) explained these low levels of engagement using a concept he calls the “disengagement contract” between professors and students. Some professors, according to Kuh, don't make students work too hard so that they won't have to grade too many papers or have to explain the grades they are giving. In these cases, the bargain between professor and student is “I'll leave you alone if you leave me alone” (Kuh, 2003, p. 28). Such weak engagement from professors is seriously troubling when considering how research has linked student success to professors' engagement (Riddell and Haigh, 2015; Mårtensson and Roxå, 2016). A survey by Gallup Purdue University (2014) has shown that professors have an impact on their students' engagement even after they leave university.

When looking specifically at academic integrity, Adkins and Radtke (2004) examined which type of teaching role professors adopted when teaching accounting ethics. Three different roles were uncovered: the active vs. the passive professor, or the resource for students. The active professor “actively prepares him/herself to broach the topic in the classroom and adopts a methodology to support an ongoing learning process.” The authors mention the importance of being fully committed and trained to teach ethics to be able to assume this role.

The passive professor, when compared to the active professor, is not as committed, confident or enthusiastic when it comes to teaching ethics. He or she will refer students to books or websites. Whereas, the active professor will be an expert in accounting ethics, the passive professor is not expert, but will readily discuss ethics issues with students (Adkins and Radtke, 2004).

The third role a professor can adopt, according to Adkins and Radtke (2004), is to be prepared to offer resources to the students. Like the active and passive professors, the professor who acts as a resource will also discuss ethics with students. However, “in this informal capacity, faculty members do not need to prepare for ethics presentations or discussions, as is necessary in the other two possible roles. A faculty member can merely draw upon his/her personal knowledge of accounting ethics and professional conduct to guide interactions with students” (Adkins and Radtke, 2004, p. 293).

Research Questions

The conducted research aims to describe the various roles professors adopt when they teach academic integrity. More specifically, the research questions were:

- What roles do professors play in teaching academic integrity through informational, writing and referencing skills to their students?

- What roles do professors play in teaching their students about plagiarism knowledge?

Method

The results presented in this article come from a broader project on digital scrapbooking strategies (SSHRC, 2016–2019) that involved several research steps using a mixed-methods research approach. Data collection took place in 2017 and 2018 in six Quebec universities. In the present article, the results come from qualitative data drawn from 49 semi-structured interviews with professors at the six universities.

The Participants

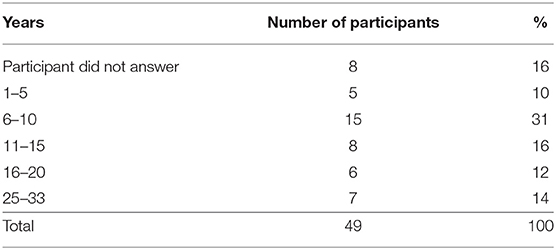

The participants were eight part-time professors (16%) and 41 university professors (84%) from six Quebec universities. There were 21 men (43%) and 28 women (57%). The participants had different levels of teaching experience (see Table 1), with the largest proportion (31%) of respondents having between six and 10 years of teaching experience. Some participants choose not to disclose their years of teaching experience in the interviews.

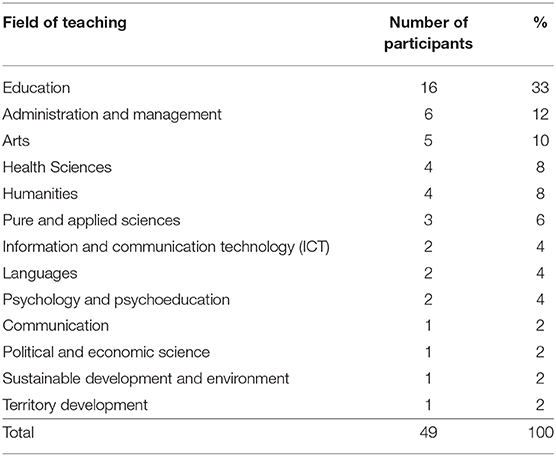

As Table 2 indicates, one third of participants are from the field of education. This is a limit of the study. However, there are 33 professors from other disciplines which were interviewed, permitting us to interpret the results as trends which apply across faculties.

Research Instrument

University professors in the six universities were invited by their administration to participate in individual interviews through e-mail. The total recorded interview time was 29 h and 24 min. On average, the interviews lasted 36 min. The interview protocol had 23 questions. Professors were asked socio-demographic questions to start, followed by prompts about the classes they taught and the assignments they gave students. Then, data on the three types of skills (informational, writing and referencing) was elicited from the professors. Finally, participants commented on how they taught about plagiarism prevention.

Data Analysis

All the interviews were transcribed and all data that could identify participants was deleted from the transcription. The transcriptions were analyzed with N'Vivo. All the interviews were systematically coded, in order to detect trends in the professors' opinions about their role in teaching academic integrity to their students. The inter-rater agreement on the recoding of 12% of the interviews was 80%.

Four broad categories were established for the analysis: the three types of skills and plagiarism prevention. Then, sub-categories were added examining if the professors taught or did not teach the skills or plagiarism knowledge, the reasons why, how the teaching was done, who was responsible and when it was done. In total, 66 sub-categories for the actions and justifications of the professors were used. Once the coding was finished, similarities, and differences were compared for the categories and sub-categories and seven general roles emerged from the variations noted. The actions for each of the four broad categories were tallied for all the participants, which lead to an individual profile for each of them with their preferred role. These will be presented in detail in the following section.

Results

Requirements of Professors for Web-Related Written Assignments

At the beginning of each interview, participants were questioned on the requirements they issue to students when giving assignments that might require them to conduct information searches on the web.

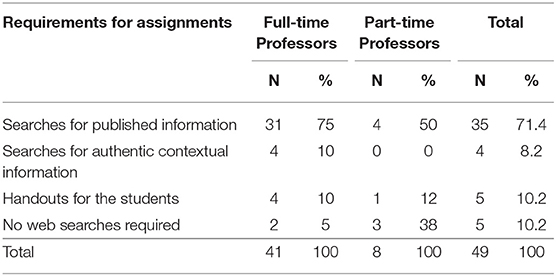

Of the 49 participants, 71% of them required students to search for information for their assignments.

The other types of requirements were not as frequent, with only four or five participants mentioning providing handouts on the course's webpage, or not requiring any web searches.

From the outset in the interviews, professors were asked whether the assignments they asked their students to do required a search for information on the web. Four types of requirements emerged from the qualitative data.

Of the 49 professors, 79% answered yes: in 71% of cases, the requested work required a search for published information on the web and in 8% of cases, the students had to search for authentic contextual information. In the other cases (21%), there was a search for information was done in handouts posted by the professor on the course's webpage (10%) or no web research at all (10%).

When comparing part-time and full-time professors, two differences stand out (see Table 3). A larger percentage (38%) of part-time professors than full-time professors (5%) did not require web searches from their students. Only full-time professors demanded searches for authentic contextual information in their classes.

Searches for Published Information

The majority of professors (71%) demand that their students search the web for published information, books, and articles on the web, in databases, and using different tools such as Google Scholar. Some professors dictate how many sources students need to find while others also specify quality criteria: “I never give specific requirements to my students about how many sources they should have. I always tell them very clearly that I do not want Wikipedia: I want scientific sources. I want either books or articles” (Prof45, Political and Economic Science). Professors explained how these sources have to be used by students to support their opinions or to present a link between theory and practice.

Searches for Authentic Contextual Information

There are different types of information available online, and four professors (two in administration, one in environmental studies and one in computer science) ask their students to search the web for non-scientific information or what one professor called “authentic contextual information” (Prof37, Administration and Management). For example, students will be required to read company websites and find out about their products and about their competitors in order to develop their own business.

Handouts for the Students

Five other participants also said they do not require web searches in their assignments because their students can get the information they need in the documents provided to them by their professors. During the interviews, some of these participants specified how they upload many documents on the course's website (Moodle, Blackboard, etc.) while others gather all the notes and pertinent articles in one course handout that the students purchase, eliminating the need for students to search for more information. One participant specified that his objective is not to evaluate the ability to search for information but rather “if they are able to articulate the theoretical course content and can they create learning tasks that are pertinent and coherent” (Prof33, Education).

No Web Searches Required

Five participants indicated that they did not give out assignments that required web searches. Three reasons were given. One participant explained that “undergraduate students have not taken a methodology course yet. If I ask for sources, they will not know how to find them and they will come to me with questions. So, I will have to give a methodology course for them to do the work and I do not have time for that” (Prof01, Sustainable Development and Environment). Two other professors said that searching the web was not necessary to cover the course content and that was why they did not ask for that type of assignment. Finally, two professors mentioned that the course relied on one document (accounting norms and ministry program) and that students could use this source for all the information they needed.

The Roles That Professors Adopt in Teaching Skills About Academic Integrity

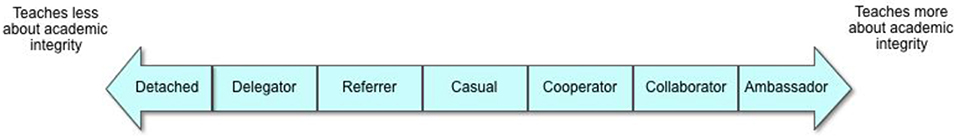

The analysis of the interviews yielded seven roles that professors choose to endorse when teaching skills that can help students write their assignments with integrity. These roles can vary, according to the skills taught. For example, a professor can choose to adopt one role when teaching about writing and yet another role when it comes to teaching about plagiarism. In this section, we describe the seven roles (see Figure 1). The following section will present the roles according to the skills taught.

The Ambassador Professor

This type of professor takes up the responsibility to teach students about one or more of the integrity skills or about plagiarism. The Ambassador professor deliberately includes activities in his or her curriculum to help students develop the necessary skills and knowledge to write their assignments with integrity. Here are two examples of professors who adopt the role of Ambassador.

One professor (Prof01, Humanities, Informational skills) specified how he “always gives students criteria to choose sources that are valid. We look at the criteria, at the questions we should ask ourselves, all the verifications needed before we use a source in an assignment.” Another professor specified how, even though it is not written in his course outline, he systematically works with the students to understand how to produce a good report for a customer, how to write a proper introduction and conclusion, and how to eliminate unnecessary information (Prof37, Administration and Management, Writing skills).

The Collaborator Professor

The Collaborator professor chooses to collaborate with other experts in the institution, whether they are librarians or writing specialists. These experts come into the classroom and give training, in collaboration with the professor, to help students develop the three skills and acquire knowledge about plagiarism. The professor is an active partner in providing this training.

In interviews, all but one of the Collaborators specified having a partnership with the librarians of their institutions. One professor who worked with a librarian explained how “there is three hours at the library dedicated to learning about searching for information. The following week, we reinvest what they learned in another kind of exercise. The librarian comes to this class also. This is not an optional activity” (Prof46, Health Sciences, Informational skills).

The one Collaborator who did not organize a partnership with the librarians, a professor in pure and applied sciences, teamed up instead with the French Department. The students' assignments were graded twice. First by someone from the French department who underlined all the grammatical errors. The papers were returned to the students who corrected their mistakes and then submitted to the professor who graded the content a second time. This professor explained how “students found it difficult but many understood the importance of the language. It is important to make students aware but by myself, I am limited” (Prof19, Pure and Applied Sciences, Writing skills).

The Cooperator Professor

The Cooperator professor also invites specialists to help train the students, but unlike the Collaborator, the Cooperator is more passive. The professor does not take part in the training, letting the specialist prepare the class and teach the students. During his interview, Prof22 discussed how “someone from the library comes and trains the students on scientific sources, their differences. Then I ask students to use scientific sources from refereed journals in their assignments” (Prof22, Arts, Informational skills). This same professor asks the specialists from the Oral and Written Communication Centre to “come to class, give a presentation. They are the ones who manage everything: the dates when students can send their assignments, make appointments, how to do it all” (Prof22, Arts, Writing skills).

The Casual Professor

A professor who is Casual in teaching about academic integrity will take the opportunity, when it arises, to provide training for the students. Whereas, the Ambassador will provide systematic training and include it in teaching time, the Casual professor will not plan for this training but will instead offer it when he or she feels it is needed. This excerpt from Prof29 illustrates the role of the Casual professor very clearly: “What I noticed was that unfortunately, I react more than I prevent, that is when a student tells me, “I'm having trouble. I do not know how to find something”, that's where I'll give him time or guide him. For the rest of the students, as long as I do not have specific requests on that, I do not intervene” (Prof29, Education, Informational skills).

Few of the professors said that they were Casual about teaching about plagiarism. One of them said, “I do not talk about it often, I talk about it when I think it could be a problem for an assignment. Or if I find that it was a problem and I did not think it would be one, I'm going to do some kind of reminder about plagiarism” (Prof01, Sustainable Development and Environment, Plagiarism knowledge).

The Referrer Professor

The Referrer professor gives out information of all kinds or sends the students to consult someone else for training. Many professors have adopted this role, providing students with the information they deem necessary, or sending the students to student services if they need help with their referencing skills. In order to explain about plagiarism, one professor tells his students: “There is a policy on plagiarism. Go read it” (Prof31, Education, Plagiarism knowledge) while another one explains, “At the beginning of a class I tell them, listen there are pages on the site of the university where you will find the rules on plagiarism, you will even find a quiz. I encourage you to do the quiz, I do not want proof, you are adults. So, you should really understand the limits of what you can do, what you cannot do. If there is plagiarism, you are entirely responsible, I have informed you, from that moment, it is your responsibility” (Prof49, Territory Development, Plagiarism knowledge).

Other professors will refer the students to websites, various software programs (spellcheck, reference management, etc.) or will upload numerous documents on the course platform for the students. “From the first class I bring them the documents from which I build the course myself, the course notes are on Moodle, they all have access to Moodle. There is a part of the work that I do, to facilitate things for them” (Prof36, Education, Referencing skills).

The Delegator Professor

The Delegator professor believes that teaching about academic integrity and the associated skills is carried out as part of another course in the program. Therefore, it is the responsibility of others, at university or before that to teach about informational, writing, referencing skills as well as plagiarism knowledge. One Delegator, when questioned about whether he taught teaching informational skills, said, “I must say no, except in my methodology classes, where it's the object. The answer is regrettable, but we have a limited number of sessions, we want to pass on our content and it would not be effective if all the professors did that. It's better, in my opinion, if there is a course dedicated to this at the beginning of the program. After that, students might need reminders, but the bulk of the teaching is done” (Prof01, Sustainable Development and Environment, Informational skills). Yet another Delegator explains she does not teach about writing paraphrases and quotes because she has “…the impression that all this work is done at the college level. That's what I remember from when I was a college student 25 years ago, so maybe things have changed, but the methodological work, I have the impression that it is the college who takes care of it” (Prof50, Education, Writing skills).

The Detached Professor

The Detached professor is one who takes no responsibility for the teaching of academic integrity and the skills and knowledge associated with it. One Detached professor explained that he didn't teach about plagiarism because he did not know about the consequences of plagiarizing (Prof03, Education, Plagiarism knowledge) while another said that he/she “had enough of the university's decisions and their lack of severity and consequences” (Prof26, Pure and Applied Sciences, Plagiarism knowledge). Other Detached professors mentioned wanting to spend the time in class on content rather than on teaching skills that could help students write with integrity.

“Generally, I do not ask for sources in their assignments because I think that undergraduates have not had a methodology course yet. If I ask for sources, they will not know how to find them and they will come to me to question me. So, I will have to give a methodology course for them to do the work and I do not have time for that. I do not ask them to quote scientific articles. It is very rare that I ask to go beyond. I prefer to ask for more work, rather than asking them to spend their time looking for information because there they will waste a lot of time on it and they do not learn the subject of my course” (Prof01, Sustainable Development and Environment, Informational skills).

Finally, other Detached professors specified that teaching these skills was not their responsibility. “No. I consider that it does not belong to me. I do not give a French course, I give an accounting course” (Prof17, Administration and Management, Writing skills). One Detached professor commented that “this raises perhaps a more fundamental question…which concerns more the program curriculum. I think that one of the dangers that we have as a professor is to want to compensate for all the shortcomings that can be observed in a program and to say to ourselves: “I will take care of it.” Yes, but at some point, you have your course objectives and that's it. I will not take care of this responsibility” (Prof39, Administration and Management, Referencing skills).

Roles Adopted by Professors to Help Students Develop Academic Integrity

In order to determine the roles adopted by professors to help students cultivate their academic integrity, the number of actions mentioned by the professors were tallied for each of the roles.

The preferred role for each professor was determined by the highest frequency of declared actions in the various roles he or she adopted. For example, one professor's (Prof30) actions are mostly (73%) those of an Ambassador, 18% of her actions reflect moments when she referred students elsewhere, while the remainder (9%) of situations demonstrate a Casual role of intervening only when necessary. Therefore, Prof30 was categorized as a frequent Ambassador because her interventions were for the most part frequently planned and systematic.

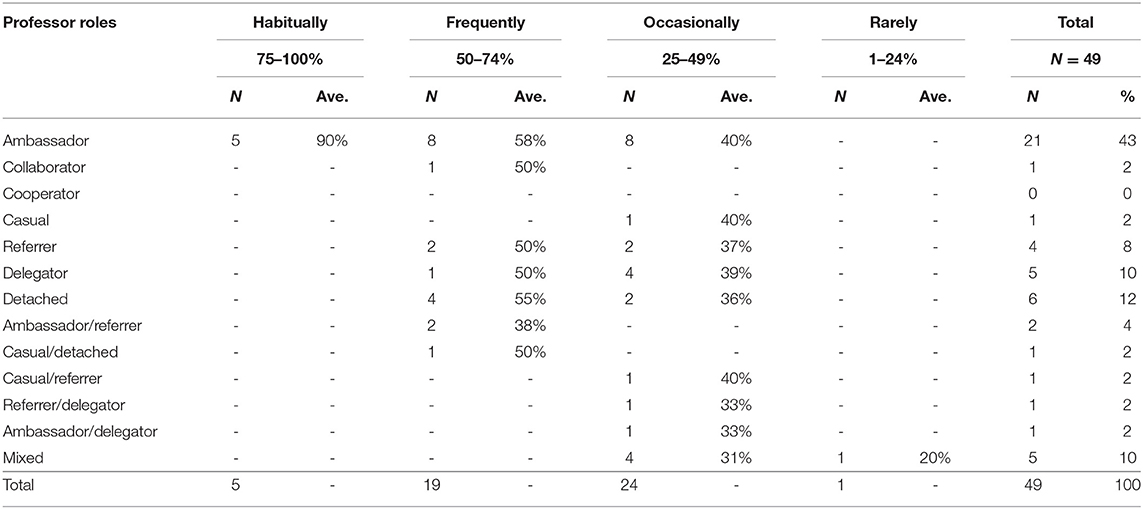

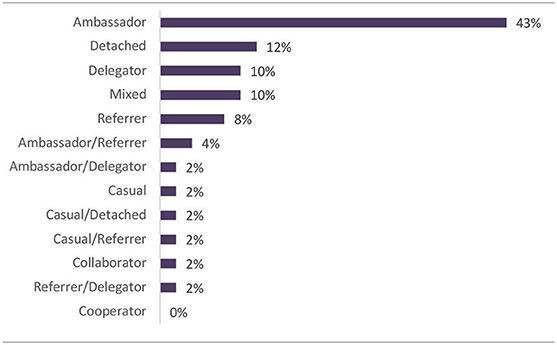

Thirty-eight professors (78%) adopted one predominant preferred role (see Table 4). Eleven professors (22%) chose to combine their interventions equally between two or more roles, depending on the skills or knowledge being taught. Six of them chose a hybrid style, alternating between two roles, while five professors divided their time between three or five roles. They were identified as mixed-role professors.

The cooperator professor was not adopted as the predominant role by any of our participants. However, some of the professors do initiate actions reflecting this role, for example, inviting university librarians in their classroom and cooperating with them to train students in information literacy or referencing skills.

Twenty-one professors chose to predominantly adopt an Ambassador role (see Table 5). It is the only role that is habitually adopted by five professors, while sixteen other professors chose to frequently or occasionally adopt this role. At the other end of the engagement spectrum, Detached is the role predominantly adopted by 12% of professors, closely followed by the Delegator (10%).

Most of the Ambassadors taught in the arts, human and social sciences, and education disciplines with only a few Ambassadors from the fields of pure and applied, and health sciences. All but three, or 86%, of the Ambassadors asked their students to carry out assignments that required searches for published information. When looking at demographic factors, two stand out. Of the 28 women, only eight (29%) chose a predominant role as Ambassadors, compared to 13 (62%) of the 21 men. There was also a big difference between part-time and full-time professors. More than half (63%) of part-time professors were Ambassadors while only 39% of full-time professors were Ambassadors.

Skills and Knowledge Taught by Professors to Help Students Develop Academic Integrity

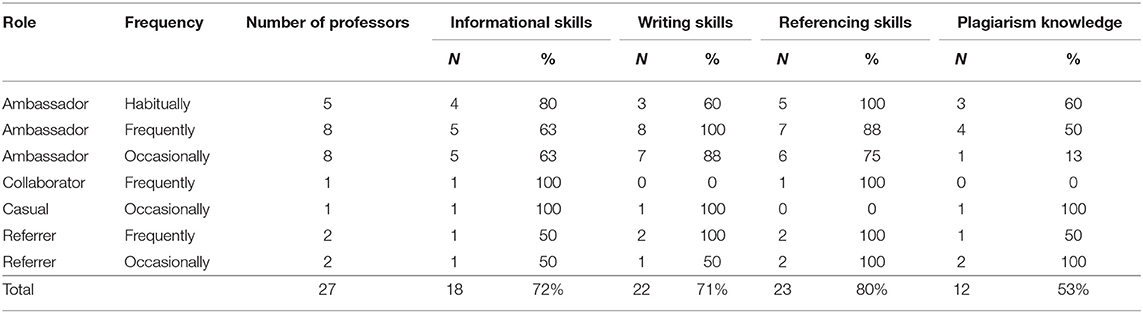

When identifying the skills and knowledge taught by professors to help students develop their academic integrity, only the actions of the 38 (78%) professors who adopted a single instructional role were examined. This decision was taken because the hybrid and mixed roles were not adopted by many participants (22%), and the frequency of their actions was essentially occasionally and/or rarely. In Table 6, the roles that professors adopt when teaching have been divided into two tables in order to demonstrate what is specifically taught about informational, writing, and referencing skills or about plagiarism knowledge. The data is further broken down by adopted role (Ambassador, Collaborator, Casual, and Referrer).

The most taught skill is referencing, followed closely by informational and writing skills. What is surprising is how only a little more than half of the professors actually teach about plagiarism. Ambassadors (of all levels of frequency) declare that they teach more writing (86%) and referencing skills (86%) than the other professors, but teach less about plagiarism knowledge.

As for Delegators and Detached professors, overall, these professors delegate the teaching of these topics to other colleagues or do not consider it their responsibility to teach on these topics.

Discussion

Ninety percent of professors interviewed require assignments that require students to search the web for information. This finding is consistent with Morton's (2007) finding that the essay was the most frequent assignment and that “almost all university tasks required for their completion the use of external sources” (p. 228). Since the large majority of participants in this study required their students to use information in their assignments, it would be understandable that their curriculum covered how to write an assignment with the proper technological tools (for example online grammar checkers and referencing software) using informational, writing and referencing skills. These cross-disciplinary skills can be very useful to students during the course of their studies and can help them produce assignments with integrity.

However, it is unfortunate to note that while most professors do teach about academic integrity and its related skills and knowledge, this instruction is done somewhat haphazardly, without a systematic approach on the part of the professors, the most common frequency being occasionally, regardless of the role. These results confirm those of Thomas and De Bruin (2012) who found that university professors considered that it was not their duty to teach academic integrity. This failure of professors to assume responsibility in this area can be attributed to many reasons: lack of time, interest, and training to teach about academic integrity and its related skills and knowledge are those most cited by our participants.

Nonetheless, five professors chose to be ambassadors habitually, and systematically included the teaching of academic integrity in their curriculum. All of these Ambassadors felt it was their responsibility to teach about skills and knowledge related to academic integrity. They are truly “Integrity Ambassadors” working to create a culture of integrity. In the next section, we will expand on Integrity Ambassadors and why it is so important to encourage all professors to adopt this role.

How to Cultivate Integrity

Today's youth are under a lot of pressure to succeed (Selwyn, 2008; Haidar et al., 2018). In order to do so, many of them do cheat whether intentionally or not, in an exam or by plagiarizing in an assignment (Koh et al., 2011). Crittenden et al. (2009) explain how a “cheating culture is one in which people: (1) are tolerant of cheating behavior, (2) believe in the need for cheating to achieve a goal, and (3) perceive that everyone around them is cheating in order to succeed” (p. 338). Farnese et al. (2011) posit that in a “morally disengaged culture,” honest students, in contact with peers who legitimize cheating behaviors, will learn and use transgressive actions. Is this the type of culture we want to cultivate in our students? Wouldn't we rather be talking about instigating a culture of learning or a culture of integrity? But how does a professor become an Integrity Ambassador?

A body of literature exists whose subject is teaching students about their learning culture. Both culture and integrity are abstract concepts to teach and both can have an impact on shaping the identity of students, on their cultural identity (Richard, 2018) and their personal integrity identity. The term “cultural mediator” (passeur culturel in French), first used by Zakhartchouk (1999), has emerged to describe a professor who will guide students in a cultural adventure, where they will acquire the tools necessary to face daily situations (Hamelin, 2014). Gohier (2002) specifies how the cultural mediator will bring students to understand their culture but also to question it in order to think and act. The professor will use various means to teach about types of culture, from popular culture to culture at home, in the school, or in the workplace, but also by referring to what is familiar to students (Gohier, 2002).

Integrity Ambassadors

The Association Canadienne d'éducation de langue française (ACELF, 2009) mentioned four roles that the cultural mediator plays when teaching about culture: he or she is at the same time an intermediary, an awakener, an accompanist and a model. In our conception of the Integrity Ambassador, this professor would adopt these four roles.

As an intermediary, the Ambassador will promote the discovery of the services available to students, introducing them to librarians, writing services, and any other services available to assist them in writing assignments with integrity.

The Integrity Ambassador will also play the role of an awakener. He or she will encourage students' appreciation of learning for the sake of learning and will nourish their reflection on what it means to write a paper without plagiarizing, inspiring others to do the same.

As an accompanist, the Integrity Ambassador guides and supports students with direct interventions in class so that they develop the skills and knowledge necessary to write their assignments with integrity. The accompanist will also cultivate a climate of integrity in class and in the university.

By being a model, the Integrity Ambassador cultivates a climate of integrity in class and in the university, showing how one can lead an academic life with integrity. The Integrity Ambassador is an active promoter of the notion of integrity through his or her actions.

However, in order for more university professors to become Integrity Ambassadors, certain conditions need to be in place. Zakhartchouk (1999) mentions three such conditions for cultural mediators that also apply to Integrity Ambassadors.

Firstly, Integrity Ambassadors need to work on their own personal integrity identity, their skills and knowledge about academic integrity in order for them transmit this integrity culture to their students. Research has shown that some professors admit that they lack the knowledge required to teach about plagiarism (Colella, 2018; Michalak et al., 2018), that they are inconsistent when dealing with it (de Jager and Brown, 2010), and some of them have even been caught plagiarizing (Elliott et al., 2013). Professors need to learn about academic integrity if they are to teach about it and become models for their students.

Secondly, Integrity Ambassadors must be convinced that academic integrity is cross-disciplinary and as such is every professors' responsibility, regardless of discipline or the course taught. The skills and knowledge required to write assignments with integrity should be requirements in every course and should addressed by all professors. This is not to say that in each class, all skills, and knowledge about writing with integrity should be taught. A program approach should be implemented, where there will be a gradation of skills presented systematically in each year of the program so that students can improve and hone their skills as they progress through their degree (Benharrat, 2018).

Thirdly, professors need to be trained to teach about academic integrity. Professors need to modify their pedagogical approaches to encourage creativity in their assignments and craft assignments that foster the develop critical thinking, especially with web searches which in turn will discourage plagiarism. Richard and Gaudet (2015) explain that cultural mediators need to be able to teach the skills and knowledge related to academic integrity, but also transmit to students the values and the attitudes related to integrity. The same needs apply to Integrity Ambassadors.

Finally, we choose to add another condition not mentioned by Zakhartchouk (1999). Integrity Ambassadors have to be supported by their institution, their administrators, and support staff. Giving recognition to professors who are Integrity Ambassadors will show everyone that integrity is an important institutional value. The culture of integrity cannot be developed in class only, but has to be encouraged throughout the university and on all occasions. It must be part of our mission to equip students with skills, but also with an ethical approach to their studies and their personal and professional lives.

Conclusion

This research has examined the roles professors play to promote academic integrity. Two limits need to be mentioned. First, the fact that one third of the professors come from the education field and second, that professors interested in academic integrity might have been more likely to accept to participate in this study. Nonetheless, the roles that emerged from the data are interesting and merit further research.

The results presented here have shown that most university professors do engage with teaching some aspects of academic integrity. However, the results also show that few professors systematically included academic integrity in their curriculum. If we want our students to learn, and our diplomas to be worth something, we need to train all of our professors to become Integrity Ambassadors and to support them in this role. If professors adopt all of the implicit roles of the Integrity Ambassador (the intermediary, the awakener, the accompanist and the model), they will be fully engaged in promoting academic integrity and will train students who will thrive academically in an ethical environment.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Université du Québec en Outaouais, Comité d'éthique de la recherche. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MP was the principal author for this article with TB and SM as coauthors.

Funding

This research project was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adam, L., Anderson, V., and Spronken-Smith, R. (2017). ‘It's not fair’: policy discourses and students' understandings of plagiarism in a New Zealand university. High. Educ. 74, 17–32. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0025-9

Adkins, N., and Radtke, R. R. (2004). Students' and faculty members' perceptions of the importance of business ethics and accounting ethics education: is there an expectations gap? J. Business Ethics 51, 279–300. doi: 10.1023/B:BUSI.0000032700.07607.02

Allen, R. N., and Jackson, A. R. (2017). Contemporary teaching strategies: Effectively engaging millennials across the curriculum. Univ. Det. Mercy Law Rev. 95:1.

American Association of School Librarians (2007). Standards for the 21st-Century Learner. Chicago, Il: American Library Association.

Amiri, F., and Razmjoo, S. A. (2016). On Iranian EFL undergraduate students' perceptions of plagiarism. J. Acad. Ethics 14, 115–131. doi: 10.1007/s10805-015-9245-3

Anderson, T. (2016). “Theories for learning with emerging technologies,” in Emergence and Innovation in Digital Learning: Foundations and Applications, ed G. Veletsianos (Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University Press, 35–50.

Association canadienne de l'éducation de langue française (ACELF), Fédération culturelle canadienne-française (FCCF), and Fédération canadienne des directions d'écoles francophones (FCDEF). (2009). Trousse du passeur culturel: la contribution des arts et de la culture à la construction identitaire.

Association of College and Research Libraries (2015). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.

Benharrat, A. (2018). “Développer attention et motivation en stimulant la “prise de conscience”: le cas de la formation documentaire à l'université,” in Colloque international: Apprendre, Transmettre, Innover à et par l'Université Saison_2, Groupe de recherche interdisciplinaire IDEFI-UM3D (Montpellier).

Boubée, N. (2011). Caractériser les pratiques informationnelles des jeunes: Les problèmes laissés ouverts par les deux conceptions ≪natifs≫ et ≪naïfs≫ numériques. Commun. Rencontres Savoirs CDI 24, 1–14.

Broeckelman-Post, M. A. (2008). Faculty and student classroom influences on academic dishonesty. IEEE Trans. Educ. 51, 206–211. doi: 10.1109/TE.2007.910428

Bruton, S., and Childers, D. (2016). The ethics and politics of policing plagiarism: a qualitative study of faculty views on student plagiarism and Turnitin®. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 316–330. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1008981

Bryant, K. N. (2017). Engaging 21st century Writers With Social Media. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-0562-4

Childers, D., and Bruton, S. (2016). “Should it be considered plagiarism?” student perceptions of complex citation issues. J. Acad. Ethics 14, 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10805-015-9250-6

Coalter, T., Lim, C. L., and Wanorie, T. (2007). Factors that influence faculty actions: a study on faculty responses to academic dishonesty. Int. J. Scholarship Teach. Learn. 1:n1. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2007.010112

Colella, J. (2018). Plagiarism education, perceptions, and responsibilities in post-secondary education (Ph.D. Thesis). University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada.

Couture, M. (2017). Normes bibliographiques, Adaptation française des normes de l'APA (selon la 6e édition du Publication Manual, 2010). Montréal, QC: Télé-université.

Crittenden, V. L., Hanna, R. C., and Peterson, R. A. (2009). The cheating culture: a global societal phenomenon. Bus. Horiz. 52, 337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.02.004

Cronan, T. P., Mullins, J. K., and Douglas, D. E. (2018). Further understanding factors that explain freshman business students' academic integrity intention and behavior: plagiarism and sharing homework. J. Bus. Ethics 147, 197–220. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2988-3

Curtis, G. J., and Vardanega, L. (2016). Is plagiarism changing over time? A 10-year time-lag study with three points of measurement. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 35, 1167–1179. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1161602

Davidson, C. N., and Goldberg, D. T. (2009). The Future of Learning Institutions in a Digital Age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/8517.001.0001

de Jager, K., and Brown, C. (2010). The tangled web: investigating academics' views of plagiarism at the University of Cape Town. Stud. High. Educ. 35, 513–528. doi: 10.1080/03075070903222641

De Silva, R., and Graham, S. (2015). The effects of strategy instruction on writing strategy use for students of different proficiency levels. System 53, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2015.06.009

Dee, T. S., and Jacob, B. A. (2012). Rational ignorance in education a field experiment in student plagiarism. J. Hum. Resour. 47, 397–434. doi: 10.1353/jhr.2012.0012

Doró, K. (2014). Why do students plagiarize? EFL undergraduates' views on the reasons behind plagiarism. Romanian J. Eng. Studies 11, 255–263. doi: 10.2478/rjes-2014-0029

Duplessis, P., and Ballarini-Santonocito, I. (2007). “Petit dictionnaire des concepts info-documentaires,” in Petit dictionnaire des concepts info-documentaires Approche didactique à l'usage des enseignants documentalistes, ed S. CDI (Nantes: Savoirs CDI), 1–99.

Eaton, S. E., and Edino, R. I. (2018). Strengthening the research agenda of educational integrity in Canada: a review of the research literature and call to action. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 14:5. doi: 10.1007/s40979-018-0028-7

Elliott, T. L., Marquis, L. M., and Neal, C. S. (2013). Business ethics perspectives: faculty plagiarism and fraud. J. Business Ethics 112, 91–99. doi: 10.1007/s10551-012-1234-5

Farnese, M. L., Tramontano, C., Fida, R., and Paciello, M. (2011). Cheating behaviors in academic context: does academic moral disengagement matter? Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 29, 356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.250

Fishman, T. (2016). Academic integrity as an educational concept, concern, and movement in US institutions of higher learning. Handb. Acad. Integr. 7–21. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-098-8_1

Fleuret, C., and Montésinos-Gelet, I. (2012). Le rapport à l'écrit : Habitus culturel et diversité. Québec: Les Presses de l'Université du Québec.

Gallup and Purdue University (2014). Great Jobs Great Lives The 2014 Gallup-Purdue Index Report A Study of More Than 30,000 College Graduates Across the U.S.

Gohier, C. (2002). La polyphonie des registres culturels, une question de rapports à la culture: l'enseignant comme passeur, médiateur, lieur. Rev. Sci. Éduc. 28, 215–236. doi: 10.7202/007156ar

Goldman, Z. W., and Martin, M. M. (2016). Millennial students in the college classroom: adjusting to academic entitlement. Commun. Educ. 65, 365–367. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2016.1177841

Gravett, K., and Kinchin, I. M. (2018). Referencing and empowerment: exploring barriers to agency in the higher education student experience. Teach. High. Educ. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1541883. [Epub ahead of print].

Guibert, P., and Michaut, C. (2011). Le plagiat étudiant. Éduc. Soc. 2, 149–163. doi: 10.3917/es.028.0149

Haapanen, L. M., and Perrin, D. (2017). “Media and quoting,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Media, eds C. Cotter and D. Perrin (London; New York, NY: Routledge - Taylor & Francis Group), 424–441. doi: 10.4324/9781315673134-31

Haidar, S. A., De Vries, N., Karavetian, M., and El-Rassi, R. (2018). Stress, anxiety, and weight gain among university and college students: a systematic review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 118, 261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.10.015

Halbesleben, J. R., Wheeler, A. R., and Buckley, M. R. (2005). Everybody else is doing it, so why can't we? pluralistic ignorance and business ethics education J. Bus. Ethics. 56:385. doi: 10.1007/s10551-004-3897-z

Hamelin, É. (2014). L'enseignant, passeur culturel au Togo. Trois-Rivières, QC: Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières.

Harris, R. (2013). Evaluating Internet Research Sources. Available online at: http://www.virtualsalt.com/evalu8it.htm (accessed September 17, 2014).

Harter, J. K., and Agrawal, S. (2011). Cross-Cultural Analysis of Gallup's Q12 Employee Engagement Instrument. Omaha, NE: Gallup.

Hirvela, A., and Du, Q. (2013). “Why am I paraphrasing?”: undergraduate ESL writers' engagement with source-based academic writing and reading. J. Engl. Acad. Purposes 12, 87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2012.11.005

Ho, J. K. K. (2015). An exploration of the problem of plagiarism with the cognitive mapping technique. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 32, 735–742. doi: 10.1002/sres.2296

Horbach, S. S., and Halffman, W. W. (2019). The extent and causes of academic text recycling or ‘self-plagiarism’. Res. Policy 48, 492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2017.09.004

Huang, J. C. (2017). What do subject experts teach about writing research articles? An exploratory study. J. Engl. Acad. Purposes 25, 18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2016.10.004

Hutchings, C. (2014). Referencing and identity, voice and agency: adult learners' transformations within literacy practices. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 33, 312–324. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2013.832159

International Center for Academic Integrity (2014). The Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity. Clemson, CA: Clemson University.

Janssens, K., and Tummers, J. (2015). “A pilot study on students' and lecturers' perspective on plagiarism in higher professional education in Flander,” in Plagiarism Across Europe and Beyond, 12–24. Available online at: http://academicintegrity.eu/conference/proceedings/2015/Janssens_Pilot.pdf

Kashian, N., Cruz, S. M., Jang, J. W., and Silk, K. J. (2015). Evaluation of an instructional activity to reduce plagiarism in the communication classroom. J. Acad. Ethics 13, 239–258. doi: 10.1007/s10805-015-9238-2

King, A., and Brigham, S. (2018). Understanding the influence of high school preparation on the success strategies of Canadian University Students. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 256:503.

Koh, H. P., Scully, G., and Woodliff, D. R. (2011). The impact of cumulative pressure on accounting students' propensity to commit plagiarism: an experimental approach. Account. Finance 51, 985–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-629X.2010.00381.x

Kuh, G. D. (2003). What we're learning about student engagement from NSSE: benchmarks for effective educational practices. Change Mag. High. Learn. 35, 24–32. doi: 10.1080/00091380309604090

Lenhart, A., Arafeh, S., Smith, A., and Rankin Macgill, A. (2008). “Writing, technology and teens,” in Pew Internet and American Life Project, eds D. John and T. Catherine (Washington, DC: MacArthur Foundation), 1–76.

Löfström, E., Trotman, T., Furnari, M., and Shephard, K. (2015). Who teaches academic integrity and how do they teach it? High. Educ. 69, 435–448. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9784-3

Lovett-Hooper, G., Komarraju, M., Weston, R., and Dollinger, S. J. (2007). Is plagiarism a forerunner of other deviance? imagined futures of academically dishonest students. Ethics Behav. 17, 323–336. doi: 10.1080/10508420701519387

Mårtensson, K., and Roxå, T. (2016). Peer engagement for teaching and learning: competence, autonomy and social solidarity in academic microcultures. Uniped 39, 131–143. doi: 10.18261/issn.1893-8981-2016-02-04

Macfarlane, B., Zhang, J., and Pun, A. (2014). Academic integrity: a review of the literature. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 339–358. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2012.709495

MacLeod, P. D. (2014). An Exploration Of Faculty Attitudes Toward Student Academic Dishonesty in Selected Canadian Universities. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary.

Maheshwari, R., Singhvi, S., Hameed, S., and Mathur, M. (2017). Faculty engagement in higher education: a new paradigm to foster quality teaching. source>Riding New Tides 121–133. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Priyanka_Jaiswal10/publication/321420090_Riding_the_New_Tides_Navigating_the_Future_through_Effective_People_Management/links/5ad447110f7e9b2859360d30/Riding-the-New-Tides-Navigating-the-Future-through-Effective-People-Management.pdf#page=142

Martin, N. M., and Lambert, C. (2015). Differentiating digital writing instruction: the intersection of technology, writing instruction, and digital genre knowledge. J. Adolesc. Adult Literacy 59, 217–227. doi: 10.1002/jaal.435

Mayhew, B. W., and Murphy, P. R. (2009). The impact of ethics education on reporting behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 86, 397–416. doi: 10.1007/s10551-008-9854-5

Michalak, R., Rysavy, M., Hunt, K., Smith, B., and Worden, J. (2018). faculty perceptions of plagiarism: insight for librarians' information literacy programs. College Res. Libraries 79:747. doi: 10.5860/crl.79.6.747

Monney, N., Peters, M., Boies, T., and Raymond, D. (2019). Évaluer la compétence de référencement documentaire chez des étudiants de premier cycle universitaire: pratiques déclarées d'enseignants universitaires. Revue Internationale des Technologies en Pédagogie universitaire 16, 39–55. doi: 10.18162/ritpu-2019-v16n2-05

Morton, J. (2007). Authenticity in the IELTS Academic Module Writing test: a comparative study of Task 2 items and university assignments. IELTS Collected Papers: Research in Speaking and Writing Assessment, 1, 197–248.

Muthanna, A. (2016). Plagiarism: a shared responsibility of all, current situation, and future actions in Yemen. Account. Res. 23, 280–287. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2016.1154463

Newton, P. (2016). Academic integrity: a quantitative study of confidence and understanding in students at the start of their higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 482–497. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1024199

Parker, J. (2011). Academic and digital literacies and writing in the disciplines: a common agenda? J. Acad. Writing 1, 1–11. doi: 10.18552/joaw.v1i1.15

Peters, M. (2015). Enseigner les stratégies de créacollage numérique pour éviter le plagiat au secondaire. Can. J. Educ. 38:1.

Peters, M., Vincent, F., Gervais, S., Morin, S., and Pouliot, J.-P. (2019). “Les stratégies de créacollage numérique et les compétences requises pour les mobiliser,” in Le Numérique en Éducation: Pour Développer des Compétences, ed T. Karsenti (Québec, QC: PUQ), 185–206. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvjhzrtg.14

Piette, J., Pons, C.-M., and Giroux, L. (2007). Les jeunes et Internet: 2006 (Appropriation des nouvelles technologies). Rapport final de l'enquête menée au Québec. Québec, QC: Ministère de la culture et des communications.

Purcell, K., Buchanan, J., and Friedrich, L. (2013). The Impact of Digital Tools on Student Writing and How Writing is Taught in Schools. Pew Research Center. Available online at: https://www.nwp.org/afnews/PIP_NWP_Writing_and_Tech.pdf

Quinlan, T., Loncke, M., Leijten, M., and Van Waes, L. (2012). Coordinating the cognitive processes of writing: the role of the monitor. Written Commun. 29, 345–368. doi: 10.1177/0741088312451112

Rettinger, D. A., and Kramer, Y. (2009). Situational and personal causes of student cheating. Res. High. Educ. 50, 293–313. doi: 10.1007/s11162-008-9116-5

Richard, M. (2018). Formation par et pour les pairs: jouer son rôle de passeur culturel en milieu francophone minoritaire au Nouveau-Brunswick. Can. J. Educ. 41, 170–193.

Richard, M., and Gaudet, J. (2015). Comprendre le rôle de passeuses culturelles que jouent les enseignantes afin de mieux intervenir en milieu francophone minoritaire. Rev. Sci. Éduc. 41, 115–133. doi: 10.7202/1031474ar

Riddell, J., and Haigh, C. A. (2015). Preaching what we practice: how institutional culture supports quality teaching. J. Eastern Townships Stud. 44, 15–33.

Rinck, F., and Mansour, L. (2014). Littératie à l'ère du numérique: le copier-coller chez les étudiants. Linguagem em (Dis)curso 13:25. doi: 10.1590/S1518-76322013000300007

Roy, R. (2009). Enquête génération C - CEFRIO 2009 Les utilisateurs 12-24 ans: utilisateurs extrêmes d'Internet et des TI. Réseau CEFRIO 7, 3–5.

Selwyn, N. (2008). ‘Not necessarily a bad thing…’: A study of online plagiarism amongst undergraduate students. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 465–479. doi: 10.1080/02602930701563104

Shi, L. (2012). Rewriting and paraphrasing source texts in second language writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 21, 134–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2012.03.003

Siddiq, F., Scherer, R., and Tondeur, J. (2016). Teachers' emphasis on developing students' digital information and communication skills (TEDDICS): a new construct in 21st century education. Comput. Educ. 92, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.006

Simonnot, B. (2007). Évaluer l'information. Documentaliste-Sciences de l'Information. Available online at: http://www.cairn.info/revue-documentaliste-sciences-de-l-information-2007-3-page-210.htm

Song-Turner, H. (2008). Plagiarism: academic dishonesty or “blind spot” of multicultural education? Aust. Univ. Rev. 50, 39–50.

Stapleton, P. (2010). Writing in an electronic age : a case study of L2 composing processes. J. Engl. Acad. Purposes 9, 295–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2010.10.002

Thomas, A. (2017). Faculty reluctance to report student plagiarism: a case study. Afr. J. Business Ethics 11. doi: 10.15249/11-1-148

Thomas, A., and De Bruin, G. P. (2012). Student academic dishonesty: what do academics think and do, and what are the barriers to action? Afr. J. Bus. Ethics 6, 13–24. doi: 10.4103/1817-7417.104698

Tippitt, M. P., Ard, N., Kline, J. R., Tilghman, J., Chamberlain, B., and Meagher, G. P. (2009). Creating Environments that FOSTER academic integrity. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 30, 239–244.

Umunnakwe, N., and Sello, Q. (2016). Effective Utilization of ICT in English Language Learning–The Case of University of Botswana Undergraduates. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 4, 1340–1350. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2016.040611

Vardi, I. (2012). Developing students' referencing skills: a matter of plagiarism, punishment and morality or of learning to write critically? High. Educ. Res. Dev. 31, 921–930. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.673120

Vargas, J. F. (2018). A Comparative study of whether the relationship between moral reasoning and academic misconduct differs between traditional and nontraditional students (Doctoral dissertation). University of Miami, Coral Gables, United States.

Walker, J. (1998). Student plagiarism in universities: what are we doing about it? High. Educ. Res. Dev. 17, 89–106. doi: 10.1080/0729436980170105

Walsh, A., and Borkowski, S. C. (2018). Why Can't I Just Google it? factors impacting millennials use of databases in an introductory course. J. Acad. Bus. Educ. 19, 198–215.

Wheeler, D., and Anderson, D. (2010). Dealing with plagiarism in a complex information society. Educ. Bus. Soc. 3, 166–177. doi: 10.1108/17537981011070082

Wojahn, P., Westbrock, T., Milloy, R., Myers, S., Moberly, M., and Ramirez, L. (2015). “Understanding and using sources: student practices and perceptions”, in Information Literacy: Research and Collaboration Across Disciplines (Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado), 185–209.

Woodard, R., and Kline, S. (2016). Lessons from sociocultural writing research for implementing the common core state standards. Reading Teach. 70, 207–216. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1505

Keywords: professors, roles, academic integrity, informational skills, writing skills, referencing skills, plagiarism, university

Citation: Peters M, Boies T and Morin S (2019) Teaching Academic Integrity in Quebec Universities: Roles Professors Adopt. Front. Educ. 4:99. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00099

Received: 01 July 2019; Accepted: 02 September 2019;

Published: 18 September 2019.

Edited by:

Tricia Bertram Gallant, University of California, San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Ceceilia Parnther, St. John's University, United StatesKatherine E. Crossman, University of Calgary, Canada

Copyright © 2019 Peters, Boies and Morin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martine Peters, bWFydGluZS5wZXRlcnNAdXFvLmNh

Martine Peters

Martine Peters Tessa Boies1

Tessa Boies1 Sonia Morin

Sonia Morin