- Department of Counseling and Educational Leadership, Montclair State University, Montclair, NY, United States

The Illescas Center at Esmeraldas College was considered by some students, faculty, and administrators as a “Black space,” “radical space,” and “community center.” While the perception of MSIs elicits a more welcoming image to communities of color because they serve more students of color, this research shows that Black spaces are still necessary for MSIs to consider in their quest to better serve students of color. Respondents were aware however, that this particular Black space, while a source of support for Black students and other stakeholders, caused conflicting feelings for others, and more specifically, administrators. While this conflict ultimately ended in the demise of the Illescas Center, it is a contradiction that must be explored to ensure that MSIs are held to the “serving” part of their designation.

“We need studies that analyze the strategic use of black characters to define the goals and enhance the qualities of white characters. Such studies will reveal the process of establishing others in order to know them, to display knowledge of the other so as to ease and to order external and internal chaos” (Toni Morrison, “Playing In the Dark,” p. 52–53).

The administrative closure of the Alonso de Illescas Center1, a thirty-year old community center on the Esmeraldas College campus, occurred on a fall morning and without any warning. The center was an office space that belonged to Esmeraldas College (a public college) but community activists and educators mainly used it. In other words, while the center was open to Esmeraldas faculty, staff, and students, not many knew about it and those who did saw it as a space where racial politics even influenced its name. Thus, while tension surrounding the Illescas Center always existed between the college and the community, not many people expected the center to be taken away from its participants in such stealthy manner. In one morning, the center was stripped of its belongings and the walls were painted to transform it into an administrative office. While the center was on its way to being emptied out, protesters, concerned students, faculty, and administrators, soon gathered by the former center and demanded answers. Many who happened to walk by the office that morning, used social media to publicly report what was occurring on the Esmeraldas campus. As more and more people found out about what was going on, the Esmeraldas campus was no longer quiet. As protesters increased, so did campus police. Services on campus closed unexpectedly, creating chaos and more disruption. A quiet morning on a seemingly quiet campus transformed as protest began to form. It was clear that Esmeraldas College was in the midst of a struggle. One mid-level administrator who managed a center for the academic affairs department provided a summary of what she knew:

Well, what happened is that there was a community-based center that was won via community struggle in [the 1980s] and it was named after [Alonso de Illescas]…and it was basically like a very interesting space because even though it was within the school, it was a ton of community work so they didn't receive funding. They basically got the space and the lights from the school and from what I've learned throughout this last month and a half is that it's been an antagonistic space from an administration perspective where in the last decades they either have tried to change the name or just take over the space…they finally did take over the space the wee hours of the morning…they came in, shut the building down and took everything from the center.

The closure of the Illescas Center was significant in many ways. For one, the center was named after a political hero of African descent who signified the birth of a new community of Africans and Native Americans who replaced a European colonial power, thus providing a powerful symbol of racial contestation on a college campus. Secondly, the Illescas Center was part of the Esmeraldas College community, a designated minority serving institution (MSI) that primarily served students of color who were active on campus and in the surrounding community. Finally, the closure of the Illescas Center left an indelible mark on the lives of students who once felt they could trust Esmeraldas College administrators who have supported them in many ways and demonstrated to students a harsher side of higher education. Students were unfamiliar with this side and felt that after this incident they no longer felt safe. To these students, there was the Esmeraldas College “before” the Illescas Center closure and an “after.”

The purpose of this paper is to explore the role of Black spaces at a Minority Serving Institution (MSI) by analyzing the administrative closure of the Illescas Center at Esmeraldas College. Minimal research has focused on the aftermath of campus conflicts and what was learned in their wake. This will be accomplished by analyzing the administrative closure of the Illescas Center at an MSI that served community and campus activists and specifically, functioned as an office for the Black Student Organization (BSO). Based on 18 semi-structured and in-depth interviews, the author examined perceptions of the administrative closure of the Illescas Center and its impact on higher education stakeholders. The results suggest that (1) counterspaces, more specifically Black spaces, offer an opportunity for higher education researchers to explore the ways MSIs provide support for students of color in higher education and (2) Black spaces serve a purpose even in institutions that are designated MSIs (3) after an incident of racial conflict, affected stakeholders reassess how they feel their organization feels about them as Black people or people of color and how they value racial justice on their campus.

Background: Esmeraldas College and MSI Research

The Illescas Center at Esmeraldas College was considered by some students, faculty, and administrators as a “Black space,” “radical space,” and “community center.” While the perception of MSIs elicits a more welcoming image to communities of color because they serve more students of color, this research shows that Black spaces are still necessary for MSIs to consider in their quest to better serve students of color. Respondents were aware however, that this particular Black space, while a source of support for Black students and other stakeholders, caused conflicting feelings for others, and more specifically, administrators. While this conflict ultimately ended in the demise of the Illescas Center, it is a contradiction that must be explored to ensure that MSIs are held to the “serving” part of their designation.

MSIs are known for enrolling a majority student of color population. According to the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions (PCMSI) “Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) emerged in response to a history of inequity and lack of minority people's access to majority institutions.” They include the following institutional types: Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs), and Asian American, Native American and Pacific Islander Serving Institutions (AANAPISIs). PCMSI writes that MSIs “have carved out a unique niche in the nation, serving the needs of low-income, underrepresented students of color.” In 2012, MSIs enrolled almost 3.6 million students or 20% of all students enrolled in some form of postsecondary education. MSIs also enroll a disproportionate number of students of color. According to PCMSI,

HBCUs represent just 3 percent of all colleges and universities; they enroll 11 percent of African American students. TCUs represent less than 1 percent of higher education institutions yet enroll 9 percent of Native American students. HSIs represent only 4 percent of postsecondary institutions but enroll 50 percent of all Latino students. AANAPISIs represent less than 1 percent of all colleges and universities, yet enroll 20 percent of all Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. (Paragraph 4, https://cmsi.gse.upenn.edu/content/brief-history-msi)

Esmeraldas College receives grants for its MSI status but it is not an HBCU. At the time of this study, the total undergraduate population consisted of over 12,000 students divided into over 9,000 full-time students and over 3,000 part-time students. This population is split almost evenly between men (over 6,000) and women (over 6,500). The largest population consisted of Latina/o students with over 4,100 students, while Asian students comprised of the second largest racial population (over 3,400), followed by White students (a little over 2,400) and Black students (2,600). Eleven students identified as Native American, over 800 students held visas, and over 500 students were identified as undocumented.

For some respondents, student diversity is attractive to administrators and students. One administrator cited student diversity as a main reason students matriculate at Esmeraldas College. However, the administrator also suggests that student diversity is deceiving as the administrators and faculty are not as diverse. He said:

So again, the choice of where to go to school, I think, you know, the first choice they make that relates to Esmeraldas is due to race to some extent. And then of course once they get here, like many campuses, despite the fact that we're extremely diverse, the faculty still tends to be majority White… you see this professor at the front of a class of a hundred people …and it's a little intimidating to some extent.

For many administrators and students, there is recognition that diversity is limited to students on a campus that is considered an MSI. Thus, aside from increasing faculty and administrator diversity, a center like the Illescas Center might be a welcome opportunity for a college such as Esmeraldas to reduce some of the “intimidation” that students might experience with a mostly white faculty and staff. Instead, the Illescas Center was as a source of organizational conflict, between administrators and students that should be explored as an example of how racism might manifest on an MSI. The notion of Black spaces at MSIs also begs the question—are MSIs mostly operating as White spaces?

Black Spaces and Higher Education

Black and White spaces have historical significance in higher education given its racist origins and history. Since its inception, higher education was built as a segregated space for White men that protected and promoted the ideologies and practices of White Supremacy. Wilder (2014) writes

The founding, financing, and development of higher education in the colonies were thoroughly intertwined with the economic and social forces that transformed West and Central Africa through the slave trade and devastated indigenous nations in the Americas. The academy was a beneficiary and defender of these processes (p. 2).

These processes were further cemented by the creation of two separate systems of education for Black and White people, built under a system of White Supremacy in which anti-Blackness was a value. As an organization, higher education then, had its origins in White Supremacy but even more poignant is that the system in many ways has protected anti-Blackness, although not always overt as its origins manifested. While researchers of campus racial climate and organizational culture and conflict have attempted to understand the ways in which racism continues to pervade systems of higher education, few researchers have discussed or found ways to understand anti-Blackness as a value that continues to affect values, beliefs, practices, and policies in higher education. The Illescas Center closure provides an important case study for the continued significance of race and notions of it that often negatively affects Black students specifically.

While segregation is no longer legal, the physical aspect of Black and White spaces continue to be cause for debate in higher education. Arguments over the continued existence of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and other institutions such as MSIs that are perceived to privilege the needs of people of color over White people provide rich accounts of the ways Black spaces are often minimized and subjected to criticism in the post Brown and Civil Rights eras. Yet, more research has elucidated on the experiences of Black students and other Students of Color suggesting that Black spaces are still very necessary to counter the effects of racism in higher education. For example, campus racial climate studies continue to emphasize that despite administrative efforts to address racial conflict in their organizations, students still face racial hostility in varying degrees (McClelland and Auster, 1990; Hurtado, 1992; Hurtado et al., 1998; Cabrera et al., 1999; Solorzano et al., 2000; Museus and Truong, 2009). Other researchers identify institutions such as historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) as “movement centers: organizations or institutions that enable a subjugated group to engage in sustained protest by providing communication networks, organized groups, experienced leaders and an opportunity to pool social capital” (Williamson, 2008, p. 2). Williamson extends this idea about Black spaces, Black colleges specifically, from movement centers to sites of organizing and places where “students used the college campus to organize themselves into a wedge against white supremacy while at the same time, they participated in campaigns initiated by other movement centers” (p. 2).

Less understood are Black spaces within MSIs, how racism manifests in these institutions, and how college administrators in these institutions respond to racial conflict. Despite this dearth in research, a few studies have begun exploring racism in higher education at Hispanic Serving Institutions (HSIs). In one study, Garcia (2016) discussed the effects of a hostile campus racial climate on student affairs professionals at HSIs. Another study by Sanchez (2017) finds that Latinx students have a greater chance at experiencing racial microaggressions at HSIs that only enroll 25% of Latinxs as opposed to 80%. Finally, Vega (forthcoming) studied racial conflict at an MSI and makes three major conclusions: (1) there is a gap in perception between administrators and students about dimensions of racial conflict (2) this gap in perception leads to dissatisfaction with and distrust for administrative response to racial conflict (3) informal learning about the institution, role of community members, and racial diversity initiatives occur after a public racial incident occurs. Vega argues that these gaps in perceptions of racial conflict contribute to benign institutional neglect in regard to student concerns about racism on their campus, even at institutions that identify as MSI.

In response to hostile campus racial climates, higher education stakeholders have formed counterspaces. Counterspaces “serve as sites where deficit notions of people of color can be challenged and where a positive collegiate racial climate can be established and maintained” (Solorzano et al., 2000, p. 70). For many students of color, counterspaces in higher education provide a place where they can feel free from microaggressions and other forms of prejudice and discrimination in spaces that have historically privileged White people. Similar to Williamson's understanding of movement centers, counterspaces also provide marginalized populations with resources to aid in protest. Additionally, counterspaces, similar to Black spaces, have historically represented spaces that White people fear. For example, Anderson (2015) says the following about Black spaces: “many whites assume that the natural black space is that destitute and fearsome locality so commonly featured in the public media, including popular books, music and videos, and the TV news—the iconic ghetto” (p. 10). In contrast, Anderson describes White spaces as “settings in which black people are typically absent, not expected, or marginalized when present” (p. 10). As such, counterspaces could be a source of organizational conflict between students, administrators, and faculty. More specifically, Black space in higher education can simultaneously serve as an empowering place for Black students and other students while at the same time be potentially feared and ghettoized for their racial-political nature—and eventually eradicated—by higher education stakeholders.

This paradoxical notion of counterspaces, particularly in MSIs, serves as a chance for higher education researchers to explore the ways MSIs provide support for students of color in higher education. As organizational conflict theorist, Pondy (1967), suggests, counterspaces and more specifically Black spaces are a manifestation of individuals' “drive for autonomy.” Pondy writes, “autonomy needs form the basis of a conflict when one party either seeks to exercise control over some activity that another party regards as his own province or seeks to insulate itself from such control” (p. 297). In this case, the creation of Black spaces not only may be a way to assert come control in a largely White space, but also challenges researchers and other higher education stakeholders to consider the ways MSIs provide or do not provide support to students of color.

The closure of the Illescas center also signifies the need Black students and other stakeholders have for Black spaces even in institutions where racial diversity is considerable and often outnumbers White people. As the definition of counterspace suggests, the Illescas Center provided a safe space for Black students to discuss issues that affect Black people in the U.S. Unfortunately, and less explored, are the deficit notions of Black spaces that people in positions of power (i.e., administrators) may hold in higher education and how these deficit notions may break down systems of support for Black students and other students of color.

Organizational Conflict Theory and Higher Education

Organizational conflict is a systemic social process that produces discord when there is disagreement about behaviors, values, practices, and policies among individuals or groups within an organization. Power is often involved in that there is an attempt to deter one group from attaining more resources than other groups, when groups try to maintain dominance, or when groups try to achieve privileges (Burke, 2006; Jones, 2007; Tolbert and Hall, 2008). Conflict is “[t]he clash that occurs when the goal-directed behavior of one group blocks or thwarts the goals of another.” (Jones, 2007, p. 413) It also “…arises whenever individuals or groups perceive differences in their preferences involving decision outcomes, and they use power to try to promote their preferences over others' preferences” (Tolbert and Hall, 2008, p. 79). Tolbert and Hall (2008) also suggest that the pervasiveness of organizational conflict means that the reasons why the phenomenon exists is due to systemic reasons not individual ones.

Conflict is often conceptualized from the perspective of resolution and management of problems that arise in an organization (Contu, 2018) and is the least understood aspect of organizational theories. Researchers have conceptualized organizational conflict from three different perspectives that shape our understanding of conflict: the traditional, human relations, and interactionist perspectives (Robbins and Coulter, 2016). The traditional perspective suggests that conflict must be prevented because it is not an endemic part of the group or organization—“that it indicates a problem within the group.” The human relations perspective recognizes the strength in conflict and suggests that it is a natural part of any group or organization. The youngest of these perspectives, the interactionist view of conflict, builds on the human relations perspective by including the understanding that conflict is not only natural and positive but also essential to the learning, improvement, and growth of a group. These perspectives have important implications for organizations and stakeholders who deal with conflict. For example, if an organization's stakeholders and decision makers believe that conflict is not a natural part of the organization, the traditional perspective, they may consider firing individuals rather than understanding the types of conflict that may be important for that organization to understand, such as racial conflict. On the other hand, accepting conflict as a part of an organization that should be studied, understood, and learned from (the interactionist perspective), could produce more effective practices particularly when considering racial conflict in organizations.

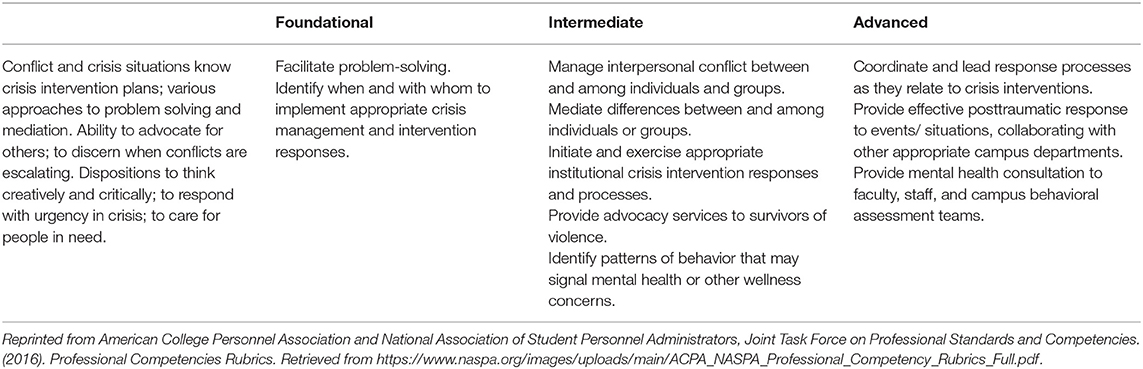

In higher education, organizational conflict is minimally studied, but is considered an important competency among higher education practitioners. Specifically, two higher education associations (NASPA and ACPA), delineate practices associated with being competent in conflict. The rubric suggests that conflict is associated with crises and the ability to manage conflict by identifying when conflict escalates. While conflict is often considered as a phenomenon that must be managed, fewer understandings of conflict suggest that it is a normal part of an organization and that learning from it can actually be positive for a system. As such, one might think that conflict would move beyond resolution and management in education, but how conflict is understood in education is still relatively unknown (Table 1).

The next section will review how conflict has been theorized and how it applies to this work.

Four Components of Organizational Conflict

Conflict can be described as a process that must meet four different components: the actors, environment, perceptions between parties, and how conflict is handled. The first component for conflict to occur are the actors, parties, or subunits involved; that being some researchers say that conflict must involve at least two parties (Tolbert and Hall, 2008) while others (e.g., Burke, 2006) say conflict can occur within the individual but the conflict is often in relation to the environment in which the individual is in. The second component is the field of conflict or the continuation of present state and all alternative conditions. The third component is called the perceptions that involved parties have of each other or “dynamics of conflict situation.” The fourth component is called the “management, control, or resolution of conflict.” This is where “conflict situations are generally not discrete situations with a clear beginning or a clear end.” (Tolbert and Hall, 2008, p. 84).

According to Burke (2006), these components are found in four types of conflict that could exist in an organization: (a) conflict within the individual, (b) interpersonal conflict (i.e., individuals with each other, (c) intergroup conflict (i.e., offices and programs in interaction with each other), and (d) interorganizational conflict.

Causes and Bases of Organizational Conflict

Researchers have attempted to understand the causes and bases of organizational conflict (Pondy, 1967; Burke, 2006; Tolbert and Hall, 2008). Jaffee (2012) argues that historically, organizational conflict occurs due to two types of tensions: the individual conflict which is based on human desires, skills, and competencies to assess, evaluate or change the organization. The second type of tension is the organizational tension which is derived from the diversification of organizational responsibilities that have the potential to disrupt affinity to the organization.

Although written almost 50 years ago, Pondy (1967) included five reasons for conflict occurring (1) Interdependence, (2) Differences in Goals and Priorities, (3) Bureaucratic Factors, (4) Incompatible Performance Criteria, and (5) Competition for scarce resources. Tolbert and Hall (2008) suggests there are three bases that cannot be avoided in an organization, thus making organizational conflict inevitable and must be accepted as a given. They write, “Since these three key bases of conflict—differentiation, duplication of functions, and hierarchy—are more or less inevitable features of modern organizational life, the potential for conflict is inherent in all organizations” (Tolbert and Hall, 2008, p. 81). Here we note that while Tolbert and Hall's causes were broad and important, they did not encapsulate everything that could cause organizational conflict. Burke (2006) described how organizational conflict manifests in Twenty-First century organizations. He says there are seven reasons for organizational conflict to occur and keeps these reasons very specific. Interestingly, much of Burke's reasons surround the areas of human diversity and the need for more education on cross-cultural communication. Among these reasons includes: globalization, diversity, work complexity (differentiation); flatter hierarchies (hierarchical); electronic communication (technological); and difficulty and accountability in managing scarcity of resources.

Organizational conflict theories provided the author with a guide into asking the following research questions. To understand some of the components of the conflict, such as which actors were involved and who was mostly affected by the closure, I asked: (1) Who was involved in and affected by the Illescas Center closure? As noted earlier, there are various reasons cited by researchers for why organizational conflict occurs. To this end, the second research question was (2) What caused the Illescas Center closure? And finally, to get a sense of the perspective of conflict that the organization may hold, my third research question was (3) How did the Esmeraldas College administrators handle the conflict that followed the Illescas Center Closure?

Method and Analytic Plan

As a former Latina higher education administrator, I was granted access to higher education spaces for this study in a way that non-administrators may not have received. For one, I understood the angst that higher education administrators feel in discussing race and racism in their institution. Having personally encountered conflict with supervisors and other administrators regarding how racism manifests and how to discuss this with students, I am particularly privy to the consequences of these events in my professional life. I also was able to interview participants through colleagues who were connected to the institutions I studied for this project. Additionally, because I lived and worked in the region where the institutions resided, I was able to witness events such as the protests that followed the Illescas closure.

While undergoing a separate investigation of racial incidents in postsecondary settings, I encountered the closure of a university center that was described by participants as an incident of racial and organizational conflict. Organizational conflict provides researchers with a way to study conflict such that individual and organizational tensions are made visible and interactions between individual beliefs, values, and practices and organizational values and practices can be explored. Organizational conflict theory can be especially important in understanding racial conflict in higher education since it is often studied from an individual perspective. Rather, organizational conflict theory suggests that organizational values, beliefs, and practices influence individual behavior that may or may not align with organizations (Jaffee, 2012). Alternately, the individuals' behaviors might impact the organization. This study seeks to understand the individual tensions that cause conflict surrounding the Illescas Center. Jaffee (2012) writes:

At the most fundamental and general level, organizational conflict stems from the unique capacities of humans. Humans, unlike other “factors of production” or organizational inputs, have the capacity to assess subjectively their environment and act to resist, alter, or counter perceived constraints. When humans are embedded in organizational structures, there is an inherent tension between the goals and objectives of organizational owners and the valued discretion and autonomy of human agents. This human factor tension has manifested itself in forms of conflict that have shaped the history and evolution of organization theories and management practices. Put another way, this tension both produces, and is the product of, the structures and processes that we call “organization” or “administration”.

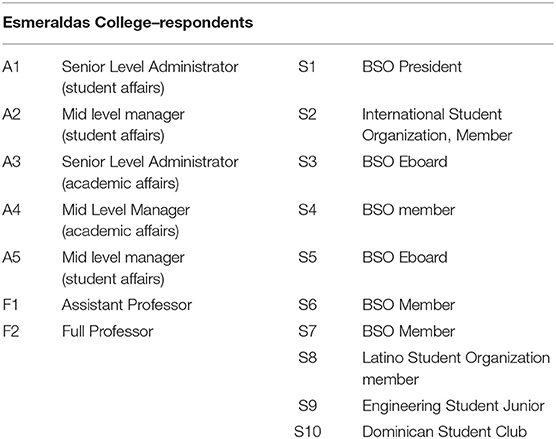

To get at the heart of this individual tension, I employed a phenomenological research design (Patton, 1990; Creswell, 2013), which is used to illuminate how several individuals make meaning of their lived experiences (Patton, 1990; Creswell, 2013). Drawing from eighteen open-ended interviews and over a year of qualitative research with participants who have identified themselves as having handled incidents of racial conflict, the interviews were used to understand how faculty, administrators, and students perceived the closure of the Illescas Center. Respondents were asked to participate in 45–60 min individual in-depth and semi-structured interviews. Included among MSI respondents were two senior level administrators, three mid-level managers, one assistant professor, one full professor, and ten students. All students interviewed participated in a racial/ethnic student organization. To obtain a more accurate account of the closure of the Illescas Center, the author asked questions regarding the components (the actors, environment, perceptions between parties, and how conflict was handled) such as (1) Who was involved? (2) Describe the Illescas Center and its purpose on campus (3) How did the actors involved perceive each other during this conflict? I interviewed students who were part of student organizations and administrators who were part of student affairs and student services offices. I interviewed administrators who had decision-making responsibilities and were in the position of hearing about racial incidents but may have had no power to respond at the organizational level (see Harper and Hurtado, 2007); faculty who were told about racial incidents but may not have had the power to respond at the organizational level (e.g., junior faculty); and students who were involved in student-run organizations who had desired some responsibility in contributing to racial diversity initiatives. For the purposes of confidentiality, I am keeping the specific areas in which administrators and faculty work as some handle issues related to diversity. Since those areas tend to be very specific, titles and associations will remain vague to protect the respondent's identity. Table 2 reflects a breakdown of the respondents for this project.

I also asked questions about the causes for this particular conflict such as (1) Why was the Illescas Center closed? Finally, I inquired about perspectives on how the closure of the Illescas Center was handled and what was learned, if anything, from this conflict.

Data Collection and Analysis

Respondents were identified using the snowball technique, which is a method that uses word of mouth as a way to contact respondents. Patton (1990) writes that it is an “approach for locating information-rich key informants or critical cases.” (p. 176). However, I also employed a purposeful method of identifying respondents. To ensure that the information I gathered met the goals of my research, I sent emails to various departments and student organizations that work in the areas of diversity to speak with respondents who have information about or directly handle racial incidents or diversity on their campuses.

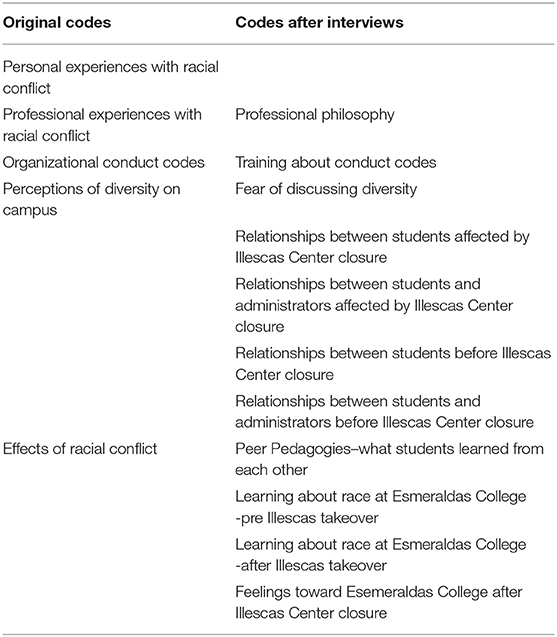

The first phase included archival data collection. In this phase, I studied the institution I used as research site. I collected conduct codes, policies, and procedures to report discrimination, campus crime reports, student newspapers, documents that reported racial incidents, and responses such as open letters to the college community. In this phase, I identified and secured interviews with those individuals directly involved in racial incidents and those who had an indirect involvement in the decision making of those responses. Phase two consisted of interviews with students, faculty, and other administrators about their perceptions of responses to racial conflict. A sample of codes that were developed using organizational conflict theories and how they changed after an analysis of five interviews are reflected in Table 3.

Participants' responses were audio recorded, transcribed, and organized with Dedoose, a data analysis system. Using themes raised by participants from a representative set of interviews, I then adjusted the codes I first developed based on organizational conflict theories to come up with a new set of codes (Miles and Huberman, 1994). This new set of codes was then applied toward the rest of the interviews.

In order to build a strong case study, I reviewed school conduct codes on racial conflict, campus crime reports, and school documents/training that referred to racial conflict. In order to understand this process, it was also not enough to obtain interviews; I provided an account of campus racial cultures within the institutions I studied by gaining the participants' perspectives on the climate and culture of the colleges. I substantiated this work by documenting the colleges' histories via publications written about the campuses' racial histories, and newspapers that provided more details and information about how the campuses have dealt with racial conflict.

Findings

Findings from this data suggest that administrators who had direct involvement with the Illescas Center closure handled the situation from the traditional and human relations perspective of organizational conflict. In other words, administrators sought to manage conflict because they believed in the power of conflict as a useful tool to help stakeholders understand each other and get along but did not suggest how or that this particular event could produce positive and long-lasting effects for the institution. On the other hand, students affected by the closure, mainly members of the Black Student Organization (BSO), experienced the center's closure as a hostile event that generated fear that Black students would be targeted again in future events and caused ambiguity about overall institutional care for Black students. No participant suggested that there could be learning involved from this and students interviewed for this research admitted that administrators did not take the time to work with students affected to understand what could be learned after the closure. Overall, this event represents largely intergroup conflict, between student groups and administration, and conflict within the individual since students were left with various unresolved understandings of what they perceived as institutional neglect of Black students.

While Pondy's perspective is that organizational conflict should be managed and minimized to ensure harmony within the organization, Pondy (1967) suggested that studying the aftermath of organizational conflict is as important as studying its causes and contexts. Because I was present during the manifest stage and aftermath stage, I was able to capture how eighteen respondents (administrators, faculty, and students) made sense of the closure of the Illescas Center. This paper is a first attempt at bringing together perspectives in the aftermath of the closure of the Illescas Center to explore what can be learned from this event. The following section will be divided into four parts: (1) Racial Conceptualizing of the Illescas Center, (2) Perceptions of the Closure, (3) Effects of the Closure and finally, (4) Learning after the Illescas Closure. We will begin with why the closure of the Illescas Center was perceived to be about race.

“That's a Black Space”: Racial Conceptualizing of the Illescas Center

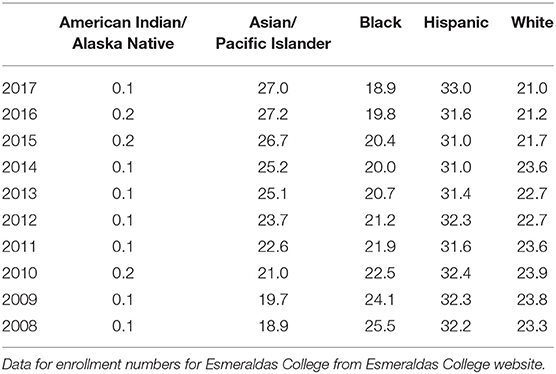

The Illescas Center resides on the Esmeraldas Campus, which is known for its large racially diverse student population. Esmeraldas is one campus that is part of a larger university system consisting of undergraduate and graduate programs. Today, Esmeraldas boasts an extraordinarily high population of Students of Color, but over time, the Black student population has been dwindling and admissions standards have become tougher for students to break through. Table 4 is an overview of the enrollment by race at Esmeraldas between 2008 and 2017.

Because of this, MSI students are accustomed to a different type of racial conflict that was not overt and occurred at levels such as between offices and faculty who are largely White. Thus, they were accustomed to what one administrator calls structural racism that is not blatant, and most specifically, racial conflict between offices or groups. This administrator from academic affairs said:

See its very interesting because, because Esmeraldas College is mostly students of color racial conflict is not as glaring as let's say at Historically White College …I see a lot of [students] able to connect the dots where if, you know, if they're having an issue with their bill at the bursars they're able to connect that structurally to say, it's not because I'm a bad person, they don't individualize it and take it personally but they look at it more structurally and they're just like this is happening because we are in an institution that's run mostly by white people.

A faculty member familiar with the center's historic beginnings discussed with me why this was about race and who was involved in the closure of Illescas. The faculty member described the reasons why the center became a source of conflict for administrators and how they demonstrated their feeling about the center.

A couple of years ago, actually the year before I came to Esmeraldas College there was a campaign to have the Illescas Center, the sign over the door removed because somebody saw the sign and was like, wait, Alonso Illescas the Black freedom fighter?…So folks are like oh the Illescas Center, right there's a radical legacy, there's a black legacy so it's like, Yo! That's a Black space, that's a radical space, that's a community space and the university is like, why would we have that, right? So it is racialized. It is about race.

One student, a former leader of the BSO and near graduation at the time of the interview, was very aware of racial politics and was able to recognize conflicting views about how racism operated on campus. One way he identified was taking away resources that were beneficial to Black and Latina/o students on campus. As organizational conflict theorists suggest, conflict arises when one group attempts to block the goals of another. In this case, one student believes that the closure was one way for administration to regain power from the community who largely controlled the Illescas Center.

Even recent events with the closing of the Illescas Center, which was a place for activism where Black and Brown students.…why it's a form of racial conflict? Because these are systems that were put in place by community members to help the people who are Black and Brown. Now, when you attack those systems and those spaces, where else do they have to go? It was a time and space not controlled by an administration, so community students can come. So, pretty much what Esmeraldas College and most colleges are trying to do, they're trying to create this elite class of folks and then blocking the community from getting on campus. They don't serve the communities that they are in.

As the definition of counterspace suggests, the Illescas Center provided a safe space for Black students to discuss issues that affect Black people in the U.S. This notion of a safe space runs in contrast to the imagined “Black space” playing in the White imagination (Anderson, 2015). Findings from this study suggest that two main perceptions of the Illescas Center prevail: one that racial, radical, and political and thus not desired by the Esmeraldas administration and the other that is supportive, nurturing, and educational. Interestingly, the respondents who identify the Illescas Center as supportive also believe it is a radical space.

One student, Black Student Organization (BSO) president, reflected on the historical origins of Illescas Center related to race and the resources and support it provided to Black community members of Esmeraldas due to these origins. The support the student describes is related to the type of conversations and knowledge about issues affecting Black people in the US that were made possible in this center. The student believed that even administration knew this was about race because they had knowledge of this history for Black the community of Esmeraldas.

So, for [President of Esmeraldas College] to know the history to know how that space was acquired and to take it away in such a manner, that was totally about race in my opinion…Just because what the center stood for. It was really a safe space to talk about [political] prisoners. It was a safe space to talk about Alonso Illescas. It was a safe space to talk about the effects of mass incarceration. Of so many conversations specifically dealing with racial climates and racial tension in America. And for that room to be taken away, and for everyone to know that that's what that room stood for, it just doesn't make any sense.

A faculty remember also reiterated that the Illescas Center was a space for Black and Latinx students who did not feel connected to the College and more specifically, administration. The faculty member recalls:

When we founded the Black Student Organization one of the folks that we were pointed to was a brother who had gone to Esmeraldas College. And, he said “that space is always under constant attack, right and it's the place where black students came together, where latino students came together”… He was interested in that space, knowing that that space has an attachment to black students and Latino students who felt disconnected from the administration

Another student, a BSO member, believed that the center was also a space where “upliftment of community” occurred.

I feel like yes, because that room itself is very historic at Esmeraldas College, you know? That's the room where every revolutionary student meets; that's where a lot of students organize from. You know, that's where we had our meetings from….So a lot of things for uplifttment of community. That was a community center. They sold food to the community in that, fresh fruits and fresh food and organic food…So that room has a lot of significance to the community itself…

Another student, member of the Latinx Student Organization (LSO) described the impact that this space had on her, citing that the Illescas Center helped her become more aware of issues that affected society and helped her become more active on campus. She says:

I would go to the Illescas Center often to hang out and talk and see what was going on. And then, [one] summer, [controversial professor] was teaching on campus and a lot of students and myself didn't agree with that. So we started protesting back and the organizing came out of the Illescas Center. So, that's when I started becoming heavily involved in campus here at Esmeraldas and other campuses as well. And then I got even more involved when they took the Illescas Center away from us out of the blue, without any warning. So, from that moment forward we did a lot, I did and others, a lot of organizing on campus, protests, holding different events, a lot of different things. So, that's when I got really involved on campus as an organizer.

“There Could be Other Reasons”: Competing Reasons for the Illescas Closure

One main reason provided by administrators about the closure was competition for resources, a main source of organizational conflict. Interestingly, while respondents cited development and advancement of opportunities for students as reasons for the closure, administrators were aware of the opportunities offered by the Illescas Center but they felt that was limited to a few students. While all respondents understood how significant this center was for Black students and other community members, students and administrators were told that the center had to be removed to expand administrative space dedicated to student services. One student said, “The reason they gave was saying it would grant a better opportunity for students, because it was used by a few students as compared to the entire campus. How it would give other students more opportunity for development” (BSO officer). One student affairs administrator admits that she knew the historical significance of the center but the need for space among higher education administrators was a real concern. She reflects:

And so it seems to me that in student affairs that when, first of all we don't have any; they're always trying to take it away then when they do give us something its basically something we can't use because its mired in some kind of controversy so at the end of the day we still end up with nothing and neither do our students. So I tell them and I just believe to be authentic with students so as far as I'm concerned I think [we need] all the space they can get and that's it, you know, period. And I just find the whole issue of space thing to be very frustrating and I don't really see giving space to groups or anybody to use when we don't have space enough for ourselves. …

The BSO president admitted that administration might not have only thought about this as related to race but its significance to students of color is too meaningful to overlook. She said:

There could be other reasons, but to me in my mind and too many students' minds, in their thought process, it's like no, this comes down to the fact that this was a space where students of color, the only space for students of color on this campus and you took it away.”

Perceptions of the Illescas Closure

Respondents were attuned to how students were experiencing the closure. Students reacted to the closure very negatively. They felt that it was disrespectful and sent a message to Black students at MSI. Some had trouble describing how administrators felt about Black students because they began to see themselves through the lens of the closure. Meanwhile, administrators who were in touch with more students that were not directly involved with the center, saw the closure as causing some division among the students. This division between student and administrators seem to have been significant and never quite resolved.

“It Was Very Disrespectful”

Students report that they were told about the reasons for the Illescas Center closure after the incident occurred. In addition, they were not given warning about when it was going to happen. One BSO officer recalled the following:

…they took away the Illescas Center without notifying anyone. That was kind of a big controversy that was going on, on campus…. And that was very controversial and stirred up a lot of mix on the campus, it was really bad. I think it was bad overall because how they went about it and things like that. They didn't notify anyone, even the people who worked in that center on a daily basis. They weren't notified of the place being taken away and being converted into something else. They went about it very unprofessional, very kind of disrespectful in a way. Overall it was very disrespectful.

Another BSO member student reported about how the closure created ambivalence about his thoughts about how administration perceived Black students.

They're not really too fond of, you know, black students and all that (pauses) I think that's a little bit too strong of a statement. Let me retract that. Because the reason why I even made that statement, because recently they closed down the Illescas Center…and they closed down the whole campus just to take, seize that room. Obviously, that was wrong…So the students protested. And we were treated like we were rebels. They had barricades at every door, and then the school was on lockdown. So, coming into school, I felt like I was going to prison, because I could only enter through one exit and exit through one exit. And just the way the security guard was just going after students was like wait, what are you doing? Like we pay to come here every day, so how do you treat us like animals.

An international studies organization student described the event as shady because administration removed the items from the center and closed down some areas of the campus down despite the understanding that these spaces would be open given midterms season.

[Campus] had just opened for midterms and it was supposed to be open 24/7, they shut it down. And long story short it was because they took over the Illescas Center. They took everything and put it in storage. They just threw everything in boxes, I saw the pictures of what they did, the boxes are fine, it's just that the way they did it, really shady.

Another administrator from academic affairs, admits that the way administration handled the closure was disrespectful as well. Additionally, the administrator felt that despite the center's efforts to include other marginalized groups, students of color would feel the brunt of this disrespect. She said:

The way that it was done in such a like draconian disrespectful way, to me, it just, it just puts it up there because it's not just about the seizure of the center it's also about power and it's also about, it was a slap in the face to show student how little the administration cares about students of color. Even though a lot of the organizing within the space was also targeted toward the LGBTQ communities, you know and even work and poor communities… but it, it definitely targeted students of color.

“It Was Polarizing”

Some administrators, while recognizing that this was about race and did not describe the event as disrespectful, noticed how divided the campus was about the center being taken over. A student affairs administrator said:

Well, it's kind of interesting. It initially was very polarizing type thing, either you like… there's this part of the student body, is very passionate and oh, this is an outrage! How can the university do this? And you know, this is our space. This is draconian and so on and so forth. And then there's other parts who are like what? What are you talking about? I couldn't care less. You know, how does this… is the B38 still running Brooklyn? That's all I care about. You know, so it was… again, it depends on the student group, the organization. There wasn't this grounds for united, 100% of the student body jumping up and down about it. You know, there was a population who wasn't very excited and very invested in getting something done about it and there's the other part of the student body saying can you guys get out of my way? I'm going to class, as they walk through the protest.

A BSO member also noted how divided some students were about this issue during the protest. They noticed that some were deeply affected by this issue and joined the protest while others did not understand why the protest was occurring since to them “it's just a room.”

And also, because I just… a thought just came to my mind like even throughout the protests now…during the protests, even the school itself was divided. A lot of students didn't know or understand what was going on so like black kids, Latinos, whites, everybody was like divided too. Like some kids were like hey what's going on? We want this room back. And other students were like you know what are you guys doing, shut up. It's just a room, you know? So that itself started to divide the campus itself.

Another student who was a member of the Dominican Student Organization believed that because examinations were happening on campus, that the protest was perceived as not significant. She said:

Like, people just stayed the same. It didn't really make much of a difference because, like I said, people were unaware of what was actually going on. So, people were like, “Oh.” Because this took place during midterms. So, people were like, “I don't care. I have a midterm. Let me go into school.” Because they closed the school down, so nobody would be allowed. So, people were like,” You know, I don't care about this. I need to go to class.“…it's really sad to see how many people who walked right by and, “Oh, whatever. I don't care.”

Effects of the Illescas Center Closure

Many student respondents who spoke about the Illescas Center closure were part of the Black Student Organization (BSO). Thus, respondents mostly wondered about the future of the BSO and their work on campus. Interestingly, all student respondents whether they were closely connected to BSO or not, all recognized how much learning about the history of activism at Esmeraldas, the role the Illescas Center had in that history, and about the BSO.

To begin, many students described the closure as leaving them voiceless and displaced. They wondered about what more could administration take away from Black students after having taken away such a vital resource to them. One BSO member A reflected on the closure and said “We are kind of voiceless.” She said:

We lost our rights to have that room. And it was really hard for us because that was a room that gave birth to the BSO and we grew up in that room. A lot of political clubs and a lot of black clubs had their voice expressed through that room. We had a lot of meetings in that room. It was a really important room. And since they took it away there was a lot of protesting and like a lot of problems that arose because of that. So, in that way we are kind of voiceless, because now where is BSO going to meet? And the other clubs going to meet that express their opinions through that group?

Another student used the word “displaced” as a way to describe the impact he felt after the closure of the center. Students who used the Illescas Center were not offered an alternative. They also lost their belongings because of the closure and wondered where those belongings would end up and if they were going to have those items replaced by administration. Another BSO member said:

Where do these people meet who want to do these things …Like what happens to them now? Now they have…now they have been…they have to relocate. They've been displaced. So now that sets them back from whatever goals they were trying to meet. You know? So I feel that was a very… a stab. Especially how it went down, you know?

According to one student, this displacement caused a dip in activity among students. One student member of the International Student Organization explained the following:

I just feel bad for the BSO because they had a dip in activity after Illescas was taken away because that's where they were founded. So, they lost a lot of their materials. Their first meeting of the semester was in there before the administration took it, so they looked kind of different.

Mostly, there was fear among the students. They wondered, “What else can they take away from us?” Many students wondered how being involved with the protests might affect their scholarships and other resources they felt they had garnered after developing close relationships with administrators prior to the closure. While administrators reported to me that they still feel very strongly about making sure the students are satisfied at Esmeraldas, students were not assured particularly after they learned that some students who were part of organizing the protest were expelled.

Because when the Illescas Center was taken away from us, I'm like: If the campus can take away this building the same way they took a building from us, what else can they take away from us? Like, where does it stop? So, to me, I was like, this is a really big thing. I mean, actually, you know, like, everyone who was part of the Illescas Center, that were — you know, their frequent users would always go there. But they actually like, expelled everybody that was — like, the director, who was like leading the protest. They actually, like, expelled him. He was like, kicked out of campus. So, for a while, everything just died down. They were not allowing anybody to do anything. – Member, International Student Organization.

Learning About the Illescas Center Post Closure

Interestingly, students who did not know about the Illescas Center were forced to learn about it after the closure. Moreover, students who were involved in protests or at least understood the importance of the protest began to see student apathy in a different way. One student, am member of the Dominican Student Organization, reflected:

They would just complain about the issue. You know, people kept asking me, like, “What's the Illescas Center?”— Like, a lot of people didn't even know what the Illescas Center was. They didn't even know where it was. A lot of people didn't know where it was located.…It just brought like a little bit of anger amongst each other. Like, I look at those people protesting—when they should have brought people together.

The Illescas Cener closure was not the only event that caused some changes. The protest also caused people to look at the BSO different. One change was about perceptions of the purpose of the BSO and its leaders as “fighting for what they believe in.” Prior to the closure, BSO and other groups did fight for certain changes but those changes seemed to produce less conflict between administrators and students:

So like we're mediators between the student body and the administration. We fight for the change to be implemented on this campus. Like before, I believe, campus would… the library itself would close, I believe at a 11 o'clock or 12 o'clock and the computer lab would close so early, but students had to fight for the library to be open till 12:30, for it to be open 24 hours even a week before finals week. So it's student organizations that fight for these changes on this campus.

While it seems that student organizations at Esmeraldas College seem to be the ones to advocate for certain changes that relate to student services, BSO's role in the protest that occurred after Illescas Center closure shifted beyond the expected role as “mediator” between student body and administration. One student said that people looked at the BSO as being able to “stand up for what they believe in” after the protest. However, the respondent also recognized that multiple groups chose to use the Illescas Center closure as way to protest other student concerns. The student said:

People realize that we are willing to stand up for what we believe in. People look at us differently. But there are also actually problems because throughout our protest there were people advocating for different causes. [For example] Someone was advocating for ROTC or something. When I say them, I mean the other students on campus. They realize that people really do fight for when they believe in. …

Additionally, a few respondents' perceptions changed regarding the treatment of Black students at Esmeraldas in general. One student said: “But they looked at other people; they just looked at the school as a whole differently…in a worse way.” Another student admitted that he prefers to ignore how racism manifests on campus. However, after the closure and treatment of students during the protest, he had to recognize it.

I'm kind of a more optimistic kind of person. I kind of like put a blind eye to those type of things. And I like to believe that everyone has the same positive mindset. And the whole racism thing is over, but when I saw this thing happen, I was kind of like okay, I kind of see it a little bit more now. I like to turn a blind eye to those type of things because probably I wasn't exposed to it as much. I really wasn't exposed to it as much.

Aftermath: Theoretical Considerations and Implications for Practice Applying Organizational Conflict Frameworks to Understand Racism in Higher Education

Organizational conflict provides an opportunity to understand how racism works aside from the individual and interpersonal forms that is much more documented and understood in education research. It also helps provide a framework to understand how racism might manifest at MSIs, an area that needs attention. While research suggests that hate crimes and various forms of racial discrimination diminish at campuses that have higher numbers of Black and Latinx students, the research does not provide a more nuanced explanation for loss of resources such as the one experienced with the Illescas closure. Focusing only on hate crimes, or the more overt forms of conflict, misses important areas where racial conflict may be occurring within an organization and more specifically, an MSI.

Despite the promises of organizational conflict theories on understanding race in higher education, theoretical perspectives of organizational conflict do not apply a critical race lens. Centering race in organizational conflict theories could provide researchers of organizations with insight into the process of racial conflict, how it may manifest on college campuses, and how one can respond effectively to such instances.

The Role of Institutional Agents in the After Math of Conflict

Pondy (1967) stressed the importance of studying the aftermath of conflict in organizations. However, not much theorizing has gone into what is learned after conflict or protest. An important part of this learning includes actors involved and most specifically, institutional agents. Stanton-Salazar (2011) defines an institutional agent as an individual who is aware of their position on campus and recognizes that the organization does not or cannot allocate resources equally among its members. With this recognition, then, actors in these positions become institutional agents when they “…directly transmit, or negotiate the transmission of, highly valued institutional support, defined for now in terms of those resources, opportunities, privileges, and services which are highly valued” and these resources “are mobilized to benefit another, such as when [institutional agents] uses his or her position, status and authority, or exercises key forms of power, and/or uses his or her reputation, in a strategic and supportive fashion” (p. 1075). This definition of an institutional agent suggests that there may be some conflict involved in recognizing that the institution may allocate resources unequally across various lines such as race. Thus, more work should be done in understanding how institutional agents identify and navigate various forms of organizational conflict. Based on these findings, institutional agents should be aware of how race based organizational conflict affects stakeholders, the environment, and the organization as well. The following is a summary of what institutional agents might learn from this work and studying organizational conflict at their institutions.

Race-Based Organizational Conflict Affects Trust Between Students and Administration

All 10 student respondents reported feeling either unsafe or unable to trust administrators after the Illescas Center closure. Despite this, student affairs administrators felt they gave students sufficient explanation about the closure and how that office space will be used (i.e., center was going to be transformed into a student services office that more people could benefit from). Additionally, according administrators and students, no student organization has a dedicated office space to convene. Yet, students expressed that they became more distrustful of administrators after the center was taken over. Administrators should think about how responses to incidents of racial conflict match or do not match their perceptions of students' feelings of safety toward them.

Race-Based Organizational Conflict Causes Black Students to Experience Individual Conflict

In organizational conflict theories, individual conflict suggests that the individual's ideas about themselves are not aligned very well with how the organization perceives the individual. For this study, I was interested to understand the impact of the closure of the Illescas Center on the affected students' perceptions about racism at Esmeraldas College. While organizational conflict theorists often focus on employees of an organization, in higher education, students, particularly student leaders, play an important role in how the organization continues to run. As such, organizations should pay attention to how students' perceptions about race and racism are affected after an incident of racial conflict as this can diminish motivation toward students' individual academic goals and participation on campus.

In the Illescas case, student respondents had a difficult time describing their perceptions about how administrators felt about Black students after the Illescas closure. While they all reported that administrators felt positively toward Black students prior to the closure, this perception was shaken after the center that meant much to Black students at Esmeraldas was taken from them. While both students and administrators reported that the center was taken in order to provide more services for more students, student respondents and some administrators felt that this was direct affront to the Black community at Esmeraldas for historical reasons but also because Illescas provided a “voice” for Black students. Illescas helped amplify issues that affected Black people within and beyond Esmeraldas, provided Black students with an opportunity for leadership development within and beyond Esmeraldas, and was a supportive space—a Black space—for Black students within an MSI that was still largely run by white administrators and faculty.

Race Based Organizational Conflict Affects Interpersonal Conflict Among Students

Students who were involved with the protest and activities after the Illescas Center closure were frustrated with two main issues: other students' perceived apathy toward a center that was focused on Black students, issues, and community. While administrators and students recognized that students who were not involved with the protest after the closure prioritized coursework, student respondents felt negatively about this. They also mentioned that some students may have caused confusion about what the protest was about since some used the event as a way to voice other concerns.

Race-Based Organizational Conflict Causes Intergroup Conflict

The closure of the Illescas Cener left an indelible mark on the lives of student respondents interviewed for this research. But it may have also taken away one more Black space from the Esmeraldas community. The closure seemed to have caused conflict between groups—Esmeraldas administrators and the BSO, Esmeraldas administrators and the surrounding community—even if temporarily—but significantly as the event caused changes in perceptions about race, racism, and MSI in the minds of those directly affected by the Illescas Center and its subsequent closure. Interestingly, these also seemed to be a divide among administrators that I interviewed about the Center's closure. Those administrators who were not directly involved with the Center's closure tended to side with the students and understood the importance of the Center. While the students affairs administrators recognized the importance of the Center, they felt that another center that was available to all students should take priority. Thus, students were not the only ones to experience conflicting feelings about the significance of a Black space at Esmeraldas College.

Organizational Values of Black Spaces and White Spaces

While many of the respondents called the Illescas Center a “Black Space” the same respondents also acknowledged that the Illescas Center was also a place of support for other students of color. Having worked in higher education for almost twenty years, a common statement made by Black student organizations and other organizations that support students of color is that these organizations are “open to everyone.” Thus, it is not surprising to note that a value of the Illescas Center is to support students of color generally. However, more studies should be considered to understand why Black spaces are encouraged to make available their resources to other people of color or why stakeholders would define it as a Black space despite its availability to other people of color.

Conclusion

Although Esmeraldas College serves a predominantly student of color population, there is a perception that a school like Esmeraldas College may not need to support students of color as they navigate race and racism in higher education. But a closer look at the numbers of Esmeraldas suggests that the Black student population specifically is dwindling behind the Latina/o and Asian student populations. Additionally, even though a Black Studies Department exists at Esmeraldas College, one faculty member offered that Black Studies Departments are not enough because they were led by faculty and are not organized by students. According to my respondents the resurgence of the BSO occurred because the Illescas Center brought together various stakeholders from the Esmeraldas community. Both the Center and the BSO helped create a home for Black students that they felt was necessary for students to thrive at Esmeraldas College. Despite the high number of Black students at Esmeraldas College, there was no sense of community, alluding to the idea that just because a college admits a high number of Black and Latina/o students, it is an important component of structural diversity, but an insufficient way to create a healthy racial climate for Black students. The assistant professor said:

And I think that while Esmeraldas College has an interesting history because historically the Black studies department, which became a program, was the space for Black folks but it wasn't always student-centered space. So he (student activist) wanted a student-centered space for Black folks to engage and when I got to Esmeraldas College I saw so many faces of people of African descent, African American, Nigerian American, Jamaican, Haitian, Dominican but I didn't see any community.

In the end, community seems to be the base of any organization, and in particular a necessity for Black communities within higher education, despite the institutions' designation. While Black spaces might cause conflicting feelings among stakeholders within these institutions, stakeholders must learn to acknowledge and learn from these types of organizational conflicts in order to ensure the success of Black communities at MSIs or HWIs. Building community for Black people at MSIs might mean building Black spaces in order to truly live up to the “serving” part of the MSI designation. Therefore, we must continue to create and study Black spaces, because as Anderson and Morrison demonstrate, the people and spaces Black spaces represent, continue to play in the imaginations of dominant populations at the risk of our own eradication.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Teachers College, Columbia University IRB committee with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Teachers College, Columbia University IRB committee.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^Alonso De Illescas is a late 16th century Afro Ecuadorian freedom fighter. The name will be used as a pseudonym for the university center that was closed by the Esmeraldas College (also a pseudonym for the MSI) administration.

References

Burke, W. W. (2006). “Conflict in organizations,” in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, eds M. Deutsch, P. Coleman, and E. C. Marcus (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 781–804.

Cabrera, A. F., Nora, A., Terenzini, P. T., Pascarella, E., and Hagedorn, L. S. (1999). Campus racial climate and the adjustment of students to college: a comparison between White students and African-American students. J. High. Educ. 70, 134–160. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1999.11780759

Contu, A. (2018). Conflict and organization studies. Organ. Stud. doi: 10.1177/0170840617747916. [Epub ahead of print].

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Garcia, G. A. (2016). Exploring student affairs professionals' experiences with the campus racial climate at a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI). J. Divers. High. Educ. 9, 20–33. doi: 10.1037/a0039199

Harper, S. R., and Hurtado, S. (2007). Nine themes in campus racial climates and implications for institutional transformation. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 2007, 7–24. doi: 10.1002/ss.254

Hurtado, S. (1992). The campus racial climate: contexts of conflict. J. High. Educ. 63, 539–569. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1992.11778388

Hurtado, S., Milem, J., Clayton-Pedersen, A., and Allen, W. (1998). Enhancing campus climate for racial/ethnic diversity: educational policy and practice. Rev. High. Educ. 21, 279–302. doi: 10.1353/rhe.1998.0003

Jaffee, D. (2012). “Conflict at work throughout the history of organizations,” in The Psychology of Conflict and Conflict Management in Organizations (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 75–97.

Jones, G. (2007). Organizational Theory, Design and Change, 5th Edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McClelland, K. E., and Auster, C. J. (1990). Public platitudes and hidden tensions: racial climates at predominantly White liberal arts colleges. J. High. Educ. 61, 607–642. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1990.11775114

Miles, M., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Museus, S. D., and Truong, K. A. (2009). Disaggregating qualitative data from Asian American college students in campus racial climate research and assessment. New Dir. Inst. Res. 142, 17–26. doi: 10.1002/ir.293

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Pondy, L. R. (1967). Organizational conflict: concepts and models. Adm. Sci. Q. 12, 296–320. doi: 10.2307/2391553

Sanchez, M. E. (2017). Perceptions of campus climate and experiences of racial microaggressions for latinos at hispanic-serving institutions. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 1–14. doi: 10.1177/1538192717739351

Solorzano, D., Ceja, M., and Yosso, T. (2000). Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: the experiences of African American college students. J. Negro Educ. 69, 60–73.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2011). A social capital framework for the study of institutional agents and their role in the empowerment of low-status students and youth. Youth Soc. 43, 1066–1109. doi: 10.1177/0044118X10382877

Tolbert, P. S., and Hall, R. H. (2008). Organizations: Structures, Processes and Outcomes. New York City, NY: Routledge.

Wilder, C. S. (2014). Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press.

Keywords: MSI, organizational conflict, race, black space, diversity

Citation: Vega BE (2019) Lessons From an Administrative Closure: The Curious Case of Black Space at an MSI. Front. Educ. 3:88. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00088

Received: 15 June 2018; Accepted: 21 September 2018;

Published: 15 January 2019.

Edited by:

Marybeth Gasman, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesReviewed by:

William Casey Boland, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesDina Maramba, Claremont Graduate University, United States

Andrés Castro Samayoa, Boston College, United States

Copyright © 2019 Vega. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Blanca E. Vega, dmVnYWJAbW9udGNsYWlyLmVkdQ==

Blanca E. Vega

Blanca E. Vega