- 1Training and Educational Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

- 2Artevelde University College Ghent, Ghent, Belgium

In higher education, writing tasks are often accompanied by criteria indicating key aspects of writing quality. Sometimes, these criteria are also illustrated with examples of varying quality. It is, however, not yet clear how students learn from shared criteria and examples. This research aims to investigate the learning effects of two different instructional approaches: applying criteria to examples and comparative judgment. International business students were instructed to write a five-paragraph essay, preceded by a 30-min peer assessment in which they evaluated the quality of a range of example essays. Half of the students evaluated the quality of the example essays using a list of teacher-designed criteria (criteria condition; n = 20), the other group evaluated by pairwise comparisons (comparative judgment condition; n = 20). Students were also requested to provide peer feedback. Results show that the instructional approach influenced the kind of aspects students commented on when giving feedback. Students in the comparative judgment condition provided relatively more feedback on higher order aspects such as the content and structure of the text than students in the criteria condition. This was only the case for improvement feedback; for feedback on strengths there were no significant differences. Positive effects of comparative judgment on students' own writing performance were only moderate and non-significant in this small sample. Although the transfer effects were inconclusive, this study nevertheless shows that comparative judgment can be as powerful as applying criteria to examples. Comparative judgement inherently activates students to engage with exemplars at a higher textual level and enables students to evaluate more example essays by comparison than by criteria. Further research is needed on the long-term and indirect effects of comparative judgment, as it might influence students' conceptualization of writing, without directly improving their writing performance.

Introduction

In higher education, writing tasks are often accompanied by rubrics or lists of criteria indicating key aspects of writing quality. The primary aim of these analytic schemes is to support teachers in evaluating the quality of students' writing performance. Sometimes teachers also share the criteria with students before they start writing their text. The wide-held belief is that when students know what aspects are related to quality performance, that they can apply this knowledge successfully to their own performance. However, it can be questioned whether merely sharing teacher-designed criteria with students has the desired effect on students' learning and performance. According to Sadler (1989, 2002), criteria may well explain how the work will be graded, but they do so in rather discrete and abstract terms (e.g., is this text coherent or not), without revealing how the criteria are visualized in a text and how they interactively contribute to the overall quality of a text. This is especially relevant in the context of learning to write, as text quality is more than the sum of its constituent parts (Sadler, 2009). Even rubrics, which specify the performance levels and standards for each of the criteria, can include descriptions that are too abstract for students to truly understand what writing quality entails (Brookhart, 2018). Therefore, Sadler as well as other prominent scholars in the field of assessment (cf. Boud, 2000; Nicol and Macfarlane Dick, 2006; Carless and Boud, 2018) have argued that the relevance of showing examples to students, as “exemplars convey messages that nothing else can” (Sadler, 2002, p. 136). Through the analysis of examples students can experience themselves how high-quality texts are different from average ones, which increases their tacit knowledge of what constitutes text quality, making criteria and standards concrete (Orsmond et al., 2002; Rust et al., 2003; Handley and Williams, 2011).

However, as with most instructional practices, just providing students with examples is insufficient. They should not be seen as model texts that students can copy, but rather as illustrations for which some kind of analysis is necessary to come to a deep understanding of how different dimensions of quality come together (Sadler, 1989; Handley and Williams, 2011; Carless and Chan, 2017). Recently, Tai and colleagues have argued for precisely this shift in education: instead of students being passive recipients of what is the expected standard in their work, they need to actively engage with criteria and examples of varying quality (Tai et al., 2017). There are, however, different ways for doing so, ranging from analytic discussions of only one or two exemplary texts (cf. Carless and Chan, 2017), to comparing and contrasting a number of examples of varying quality (cf. Sadler, 2009). This leaves us with the question how students ideally engage with examples in order to optimize their learning. The aim of the present study is to experimentally investigate whether the way students engage with examples has an impact on their conceptualization of writing quality as well as on their writing performance.

A promising way to provide students with the opportunity to actively engage with examples of varying quality is through the implementation of peer assessment activities (Carless and Boud, 2018). In a peer assessment, examples are authentic pieces of work created by peers, which are therefore quite comparable to the student's own writing. Theories on formative assessment describe that the ability to make qualitative judgments of a peer's work has an effect on how students monitor and regulate the quality of one's own performance (Sadler, 1989; Tai et al., 2017). Self-monitoring and self-regulation skills appear to be a strong predictor of high-quality performance, especially in the context of writing (Zimmerman and Risemberg, 1997; Boud, 2000). Moreover, when students provide peer feedback they need to diagnose strengths and weaknesses in a text and elaborate on possible solutions through which their peers can move forward. This kind of problem-solving behavior asks for a deep cognitive process, which generally has a stronger effect on students' learning than merely receiving feedback (Nicol et al., 2014). By doing so, peer assessment can be used as a pedagogical strategy, not just for assessment purposes, but also for teaching students the content of a course (Sadler, 2010). It is, however, quite a challenge for students to make a deep cognitive analysis of their peers' work, and to provide qualitative feedback accordingly. Students often perceive the quality of the peer feedback as poor, with comments provided at a too superficial level (Patton, 2012; Yucel et al., 2014). In particular, students have the tendency to focus in their feedback at form rather than at content, and they praise their peers more than teachers do (Patchan et al., 2009; Huisman et al., 2018).

To optimize the learning benefits of peer assessment, teachers should support students in how to address both higher and lower level aspects in their feedback. One way to do so is to let students explicitly link the quality of a peer's work to predefined assessment criteria (Rust et al., 2003; Hendry et al., 2011; Carless and Chan, 2017). Although this instructional practice can be effective for peer assessments, an important remark needs to be made. It is not easy for students to use teacher-designed criteria, especially when they do not yet possess a clear understanding of what text quality looks like (Sadler, 2002, 2009). Hence, merely sharing criteria with students is not deemed sufficient. In addition, students may perceive predefined criteria as demands by the teachers, which is associated with only shallow learning and performance (Torrance, 2007; Bell et al., 2013). More beneficial approaches seem to be interactive teacher-led discussions on how to apply assessment criteria to examples (Rust et al., 2003; Bloxham and Campbell, 2010; Hendry et al., 2011, 2012; Bell et al., 2013; Yucel et al., 2014; To and Carless, 2016; Carless and Chan, 2017), or involving students in the developmental process of criteria-based rubrics (Orsmond et al., 2002; Fraile et al., 2017). Drawbacks of such practices are, however, that an effective implementation demands considerable time and resources from teachers, as well as skills to adequately guide students in the peer discussions (Carless and Chan, 2017). In addition, it can be questioned whether breaking down holistic judgments into more manageable parts supports students in grasping the full complexity of judging multidimensional performances (Sadler, 1989, 2009, 2010).

An alternative approach for engaging students with examples of their peers is through learning by comparison. In this approach students are presented with pairs of texts and for each pair they have to indicate which one out of two is the best. It has been established that, even in the absence of evaluation criteria, the process of comparative judgment is easier and leads to more accurate evaluations of quality than absolute judgments in which products are evaluated one by one (Laming, 2004; Gill and Bramley, 2013). In addition, a recent meta-analysis shows that peers are as reliable in making comparative judgments as expert assessors (Verhavert et al., submitted), and that their judgments largely correspond (Jones and Alcock, 2014; Jones and Wheadon, 2015; Bouwer et al., 2018).

Although comparative judgment is originally designed as a method to support assessors in making qualitative judgments (Pollitt, 2004), there is an increasing number of studies pointing toward its potential learning effects (cf. Bouwer et al., 2018). For example, Gentner et al. (2003) found that undergraduate business school students who compared two negotiation scenarios were over twice as likely to transfer the negotiation strategy to their own practice as were those who analyzed the same two scenarios separately, even without any preceding training. Bartholomew et al. (2018b) demonstrated that design students who were part of a comparative-based peer assessment outperformed students who only shared and discussed their work with each other. In open-ended questionnaires afterwards, these students indicated that they especially liked to receive feedback from more than one or two students and that the procedure allowed them to get inspiration for their own work from seeing a wide variety of examples.

Research also suggests that the process of comparing multiple examples requires critical and active thinking, through which students learn the most important features for a particular task. For instance, Kok et al. (2013) revealed that medical students who compared images showing radiological appearances of diseases with images showing no abnormalities learned to better discriminate relevant, disease-related information than students who only analyzed radiographs of diseases. This resulted in improved performance on a subsequent visual diagnosis test. These learning benefits seem to be especially prominent when examples are of contrasting quality. Lin-Siegler et al. (2015) showed that 6th grade students who were presented with stories of contrasting quality wrote stories of higher quality and were more accurate in identifying aspects in their own text that needed improvement compared to students who were presented with only good examples.

Hence, through the process of comparing concrete examples students gradually develop an abstract schema for quality consisting of features that distinguish good from poor quality, which they can use as a benchmark for comparing and evaluating their own work. Whether the learning effects of comparative judgment are more powerful than those of criteria use is not yet investigated, neither are the potential transfer effects to students' own writing capabilities.

Aim of the Present Study

The aim of this study was to compare the learning effects of an analytic approach for the evaluation of essays written by peers to a comparative approach in which students evaluate previous essays by comparison. There were two specific research questions in this study. First, we examined the effects of these instructional approaches on students' evaluative judgments of writing quality. For this research question we investigated the reliability and validity of students' evaluations as well as the content of their peer feedback. Together, this will provide an in-depth insight into the effects of the instructional approach on students' conceptualization and evaluation of writing quality. Second, we examined whether possible effects of the instructional approach for the peer assessment transfer to the quality of students' own writing. As these effects might be moderated by individual differences between students in their knowledge and self-efficacy for writing, we tested and controlled for these individual characteristics.

Methods

Participants

In an authentic classroom context at a university college in Flanders, Belgium, 41 second year bachelor students in business management were instructed to complete a peer assessment of five-paragraph essays in English (L2) and to write a five-paragraph essay in English themselves for the course International Trade English 2A in class. Both tasks were intended as a learning experience for students, they did not receive grades for any of the tasks. There was one student who did not allow us to use the collected data anonymously for research purposes. The data from this student was removed before proceeding with further analysis. Hence, the final dataset consisted of 40 participants, of which 23 female and 17 male students, with a mean age of 19 years (min = 18, max = 22). Dutch was the native language for the majority of students, with the exception of two students who had French as their native language.

Materials and Procedure

The procedure of the present study consisted of three consecutive phases. In the first phase students were informed about the general aims of the study, i.e., to get insight into how peer evaluation of essays contributes to one's writing performance. In addition, they were informed that all data would be treated anonymously and used only for research purposes, and that the study results would not impact their grades. After signing the informed consent, students were asked to fill in a questionnaire that included questions about their demographic characteristics, self-efficacy for writing and background knowledge of writing five-paragraph essays.

The self-efficacy for writing scale (Bruning et al., 2013) consisted of 16 items that measured students' self-efficacy for ideation (5 items, e.g., I can think of many ideas for my writing, α = 0.70), self-efficacy for conventions (5 items, e.g., I can spell my words correctly, α = 0.81) and self-efficacy for the regulation of writing (6 items, e.g., I can focus on my writing for at least 1 h, α = 0.74). As individual writing performance varies largely between genres (cf. Bouwer et al., 2015), one question was added to measure self-efficacy for writing in this particular genre (i.e., I can write a five-paragraph essay). All items are measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 100. Positive but moderate correlations between the subscales confirmed that the scales are only weakly related, and hence, measure different dimensions of students' self-efficacy for writing (0.25 < r > 0.38, p < 0.11). The additional question on self-efficacy for writing a five-paragraph essay had a moderate correlation with the subscale of self-efficacy for conventions (r = 0.51, p < 0.01), and correlated to a lesser degree with self-efficacy for ideation (r = 0.39, p < 0.05) and self-efficacy for regulation (r = 0.40, p < 0.05).

The knowledge part of the questionnaire consisted of 10 open and closed-item questions that measured students' genre knowledge of five-paragraph essays. Before class, students were instructed to study the crucial genre elements of a five-paragraph essay through a slidecast and/or a reader. Knowledge questions were focused on the information in this material and included questions about the crucial elements of the introduction and conclusion in a five-paragraph essay, definitions of topic and subtopic sentences, how to provide support for topic sentences and how to create coherence and unity in the text. In the open-ended questions, students had to indicate what distinguishes a good essay from a weak one (i.e., quality characteristics), and how this genre is different from other types of texts (i.e., genre characteristics).

In the second phase, which lasted for 30 min, students had to peer evaluate five-paragraph essays of last year's students. Ten example essays were available. The topic of the essays was related to doing business abroad, in which students either compared a self-chosen country to Belgium according to the most interesting and relevant cultural dimensions of Hofstede (for more information, see www.hofstede-insights.com), or they explained why they should (not) export a self-chosen business (field) to a certain country. These topics had been discussed in class in the week before. Consequently, all students had the required domain knowledge for evaluating the content of the essays. According to the formal requirements for this writing prompt, essays were within one page (Calibri 11, interspace 1), and references to sources were in accordance to APA norms. The selection of the essays for this peer evaluation was based on the grades for the essays received in the previous year, in such a way that the essays represented the full range of quality from (very) low, over average to (very) high quality.

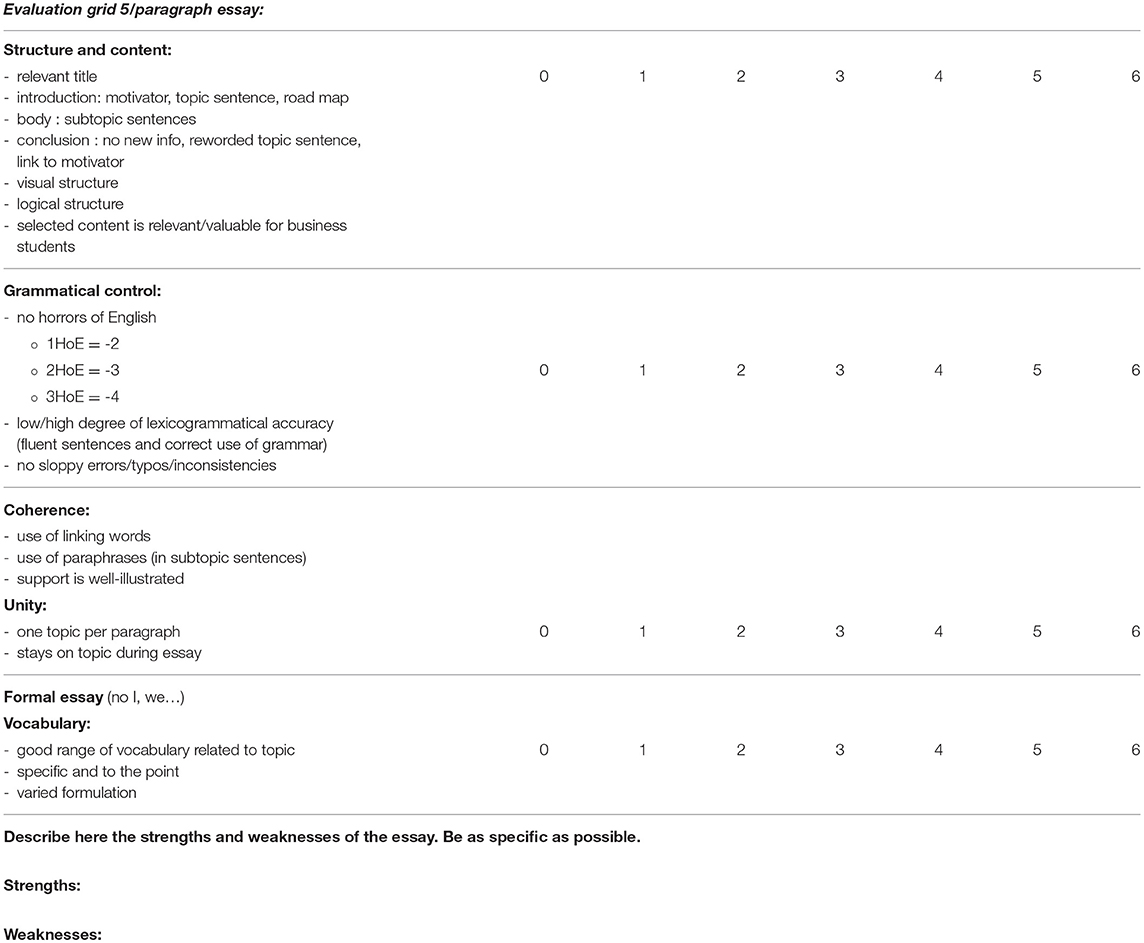

For the peer evaluation, students were randomly divided into two conditions. Half of the students (n = 20) received a criteria list to evaluate the essays analytically, the other students (n = 20) evaluated the essays holistically through pairwise comparisons. Students in the criteria condition were instructed to login to Qualtrics, an online survey platform, in which essays were presented to the students in a random order. Students had to read and evaluate each essay one by one on the computer screen, using the following four sets of criteria: (1) content and structure: does the essay include all required elements of a title, introduction, body, and conclusion, the visual and logical structure of the text, and relevance of content for business students, (2) grammatical accuracy: whether the essay is free from grammatical and spelling errors or inconsistencies, and includes fluent sentences, (3) coherence: whether the essay includes linking words, paraphrases, support, and the content shows unity with only one topic per paragraph and a central overall topic, and (4) vocabulary: whether the essay shows a good range of vocabulary that is related to topic, and is formal, specific and varied. For each of these four criteria, students had to provide a score between 0 (not good at all) and 6 (very good). The evaluation grid describing the criteria is provided in Appendix A.

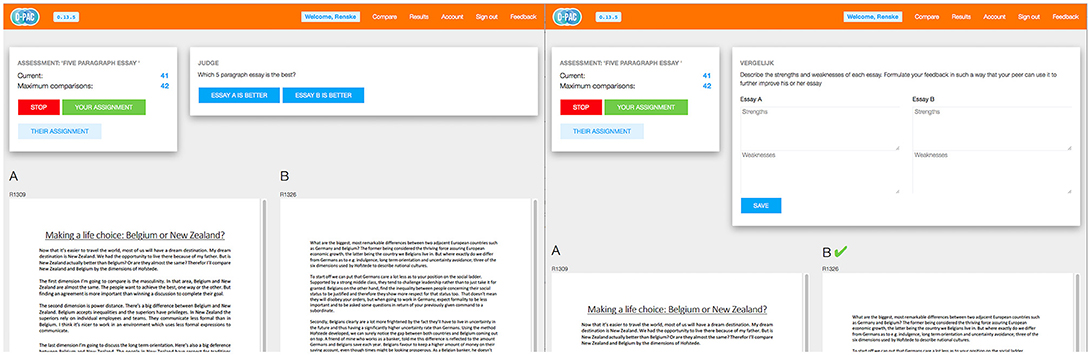

In the comparative judgment (CJ) condition students were instructed to login to D-PAC, Digital Platform for the Assessment of Competences (2018, Version 0.13.6), in which they were online presented with pairs of essays. See Figure 1A for a screen capture of comparative judgment in D-PAC. For each pair, students had to individually indicate which essay they think is best regarding its overall quality. To support students in making the holistic comparative judgments, they were provided with the same teacher-designed quality criteria as applied in the criteria condition. The maximum number of pairwise comparisons per student was 20, but students were allowed to work at their own pace. An equal views algorithm randomly assigned essays to pairs in such a way that the likelihood that a particular student is presented with a new essay is maximized. By doing so, after five comparisons a student will have seen all ten essays. Students who managed to complete the total of 20 comparisons will have evaluated the ten essays four times.

Figure 1. A screen capture of the online platform D-PAC. The left pane (1A) shows how a pair of essays is presented on the screen and how students can make their comparative judgment. After a judgment is made, it is automatically followed by the screen presented in the right pane (1B), in which students can optionally provide feedback on strengths and weaknesses per essay.

Students in both conditions were also requested (but not obliged) to provide feedback in terms of strengths (positive feedback) and weaknesses (negative feedback) for each essay. As in the criteria condition, feedback was incorporated into the flow of comparative judgment. Thus, after each pairwise comparison, students provided positive and negative feedback to each of the two texts. Figure 1B shows how the feedback form is presented on the D-PAC platform. A built-in feature of D-PAC is that the feedback for a particular essay is remembered. This means that when a particular essay is evaluated for a second time, the previous feedback will be automatically presented again. Students are allowed to change this feedback or add new comments to it. As the feedback is presented only after each comparative judgment it is very unlikely that the feedback will influence the judgments that are made.

After the peer assessment, the writing phase started. In this third phase, all students received the same writing prompt as last year. Students were free to choose one out of the two provided topics, and received the same formal requirements (e.g., one page, sources according to APA norms). They received up to 90 min to write their essay. Students were not allowed to leave class until they uploaded their essay into the D-PAC platform for further analysis.

Data Preparation and Analyses

Peer Feedback Coding

The peer feedback that students provided in the criteria (n = 106) and CJ condition (n = 369) were combined into one dataset. As each pairwise comparison in the CJ condition consisted of feedback on two texts, we transformed this dataset in such a way that each row included feedback on only one text. Further, in the CJ condition, students were presented with their previously given feedback once they saw the same essay again. In more than half of the cases, students added new feedback to the already formulated feedback, but in 45% of the cases students did not change their feedback. We excluded all the peer feedback that was identical to the previously formulated feedback from further analysis as this might artificially inflate the probability on a particular type of feedback. This resulted in a total of 203 feedback segments for the CJ condition.

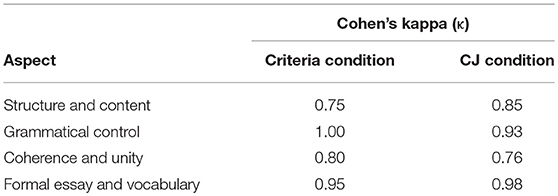

All the positive and negative peer feedback was categorized by the first author according to one of the four quality aspects of writing that are specified in the evaluation grid (see also Appendix A): structure and content, grammatical control, coherence and unity, and vocabulary. To establish the reliability of this coding procedure, a random selection of 10 percent of the essays was double-coded by the second author. Corrected for chance, there was substantial to almost perfect agreement between the two raters in the coding of the peer feedback according to the four aspects in both the criteria and CJ condition, see Table 1. Rater differences in the categorization of feedback segments were discussed and resolved before the first author continued with the coding of all other feedback segments. This collegial discussion led to the addition of a fifth category in which feedback comments were placed that cannot be categorized into any of the four other categories (i.e., miscellaneous category). This fifth category included feedback on, for instance, the font, use of sources, and the use of a picture. The total number of unique feedback points per text was used as a measure of the amount of feedback.

To test the effect of condition on the amount and content of the peer feedback multiple cross-classified multilevel models were performed taking into account possible variance in the amount and content of peer feedback due to students (N = 40) and essays (N = 10) (Fielding and Goldstein, 2006). In particular, to estimate the number of aspects that were mentioned per feedback segment, a generalized linear cross-classified multilevel model was performed with condition as a fixed effect, and students and essays as random effects. As the number of aspects is count data, following a non-normal distribution, this model was tested by a poisson distribution. In addition, separate binomial logistic cross-classified multilevel models were applied to estimate the fixed effect of condition for the average probability on feedback in each of the five categories (structure/content, grammatical control, coherence/unity, vocabulary, miscellaneous) for both positive and negative feedback, given a random essay and a random student. The parameter estimates in these models are in logits, which are a nonlinear transformation of the probabilities (cf. Peng et al., 2002). To enhance interpretation the logits are transformed back to probabilities of occurrence.

Assessment of Essay Quality

The quality of students' own written essays was evaluated by a panel of nine expert assessors using comparative judgment in D-PAC (2018, Version 0.13.6). The panel of assessors consisted of four experienced teachers in business management (three males and one female) and five researchers who are experienced in comparative judgment of writing products (one male and four females). They were instructed to login to the D-PAC platform and complete 40 comparisons in a 4-week period. They were free to do the comparisons when and wherever they wanted. To support the quality of their judgments, assessors were able to consult the students' writing assignment and the assessment criteria at any time. These assessment criteria were the same as the ones that students received during the peer assessment. Of the nine assessors, there was only one teacher and one researcher who did not manage to complete all requested comparisons, they completed only 21 and 24 judgments respectively. Together, the assessors completed 336 comparisons, with each essay being compared 14 to 17 times with a random other.

The Bradley-Terry-Luce model (Bradley and Terry, 1952; Luce, 1959) was used to estimate logit scores for the essays based on the probability that a random assessor assigns a particular essay as the better one, accounting for the quality of the essay to which it is compared. The scale separation reliability of this model was very good, SSR = 0.80, indicating that the estimated logit scores were highly reliable, as were the assessors in their judgments (Verhavert et al., 2017). In addition, there were no individual assessors for whom the pattern of judgments significantly deviated from the estimated model, with standardized likelihood ratios ranging from −1.86 to 1.22.

To estimate the effect of condition on students' writing quality, an independent sample t-test with condition (criteria vs. CJ) as the independent variable was performed and the logit scores for writing quality as the dependent variable. As the number of observations in each condition are rather low, we supplement the p-values with estimations of effect sizes and confidence to get insight in the magnitude and relative importance of the effects of condition (cf. Nuzzo, 2014; Wasserstein and Lazar, 2016).

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Students Within and Between Conditions

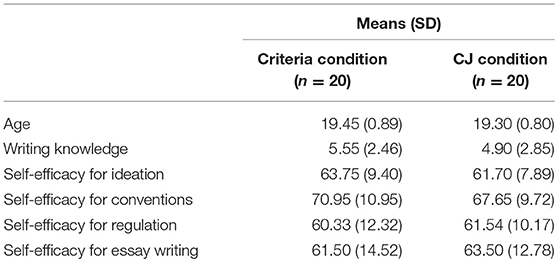

There were no differences between the two groups in terms of student's age [t(38) = 0.56, p = 0.58] or gender [X2(1) = 0.10, p = 0.50]. Table 2 shows an overview of these demographic characteristics as well as of some other potentially relevant characteristics. Results of t-tests on potential differences between conditions indicate that students in the two groups were comparable with respect to their writing knowledge [t(38) = 0.77, p = 0.44], self-efficacy for ideation [t(38) = 0.75, p = 0.46], self-efficacy for conventions [t(38) = 1.01, p = 0.32], self-efficacy for the regulation of writing [t(38) = −0.34, p = 0.74), and self-efficacy for five-paragraph essay writing [t(38) = −0.46, p = 0.65].

Quality of Peer Assessment

Results for the peer assessment phase show that the reliability and validity of the peer evaluations in the two conditions were quite comparable. Students evaluated the texts reliably within conditions, with an SSR of 0.83 for the pairwise comparisons and an average intraclass correlation coefficient 0.80 for the criteria judgments (ranging from 0.56 and 0.61 for the subdimensions grammar and vocabulary to 0.75 and 0.84 for respectively content/structure and coherence). In addition, evaluations between conditions correlated highly, r = 0.87, p < 0.01.

There were considerable differences between conditions in how many evaluations students made during the 30-min time frame. Students in the pairwise comparisons condition made faster decisions (2.9 min for a comparison) than students in the criteria condition (5.6 min for a single essay). As a result, students in the CJ condition generally evaluated more essays than the students in the criteria condition. On average, students in the criteria condition evaluated only five of the ten essays (min = 2, max = 9), whereas students in the CJ condition completed ten comparisons (min = 3, max = 20). As one comparison includes two essays, students in the CJ condition evaluated each essay twice on average.

As a result of evaluating more essays, CJ students provided also more than twice as much feedback than students in the criteria condition: 203 vs. 106 comments. There was no effect of condition on the number of aspects students commented on per essay, neither for positive feedback (p = 0.36), nor for negative feedback (p = 0.41). In both conditions, half of the feedback comments were focused on only one aspect of the essay at a time. For positive feedback at least two aspects were mentioned in 30 percent of the cases, with a maximum of 4 aspects per comment. For negative feedback this percentage was somewhat lower: only 23 percent, with a maximum of 3 aspects per comment. In the other cases the feedback segment was left blank by the student.

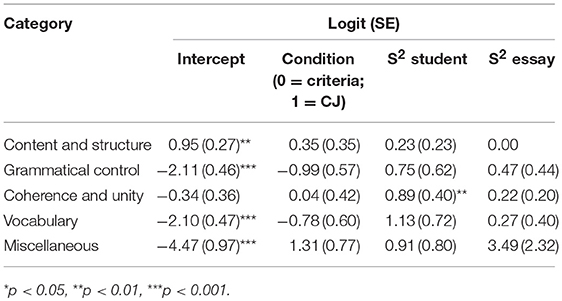

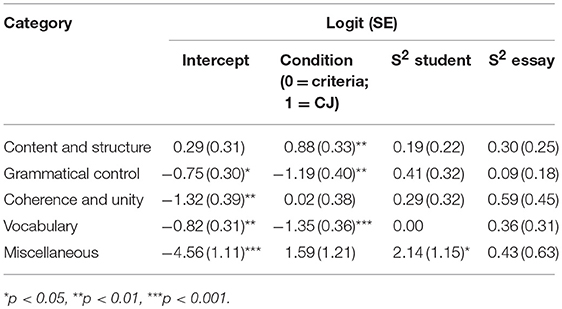

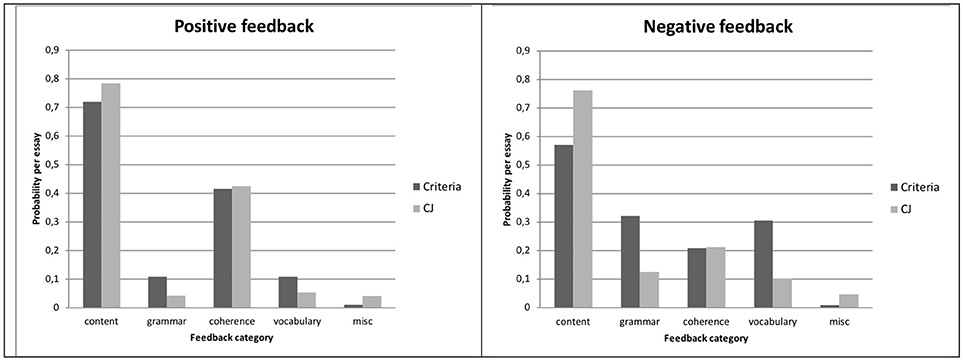

An in-depth analysis of the content of feedback showed considerable differences in the probability that a particular aspect was mentioned, see Tables 3 and 4 for an overview of the results. Table 3 shows that there were no significant differences between conditions for the proportion of positive feedback. The results were rather different for negative feedback, in which the condition affected the proportion of feedback in three of the five categories, see Table 4. Figure 2 shows the results for positive (left pane) and negative feedback (right pane) in more comprehensible terms: the proportion of feedback for each of the five categories. Below, these results of positive and negative feedback per feedback category are systematically presented.

Table 3. Estimates of Logistic Cross-Classified Multilevel Models for Positive Feedback by Category.

Table 4. Estimates of Logistic Cross-Classified Multilevel Models for Negative Feedback by Category.

Figure 2. Effects of condition (criteria vs. CJ) on the estimated probability of positive feedback (left pane) and negative feedback (right pane) for each of the five categories: content and structure, grammatical control, coherence and unity, vocabulary, and miscellaneous.

First, when providing positive feedback, students in both conditions were equally likely to provide feedback on the content and structure of the text, with a probability of 0.72 (t = −3.51, p < 0.01). There was no significant effect of condition (t = 1.01, p = 0.32), and there were no significant differences between students (Wald z = 1.02, p = 0.15) and essays (redundant). In contrast, when students commented on weaknesses in the text, there was a large effect of condition on the probability of content and structure feedback (t = 2.65, p < 0.01). Students in the criteria condition commented on these kinds of aspects only half of the time (proportion = 0.57), whereas students in the CJ condition focused on these aspects in 76% of the cases. There were no significant differences between students (Wald z = 0.88, p = 0.19) and essays (Wald z = 1.19, p = 0.12).

Second, the proportion of positive feedback on aspects related to grammatical control in the criteria condition was 0.11 (t = −4.58, p < 0.001). Although the proportion of feedback on grammar decreased in the CJ condition to only 0.04, this difference was only marginally significant (t = −1.73, p = 0.09). There were no significant differences between students (Wald z = 1.20, p = 0.11) and essays (Wald z = 1.08, p = 0.14). When students provided negative feedback, the proportion of feedback on grammar was not only higher, but there was also a negative effect of condition (t = −1.19, p < 0.01). The proportion of grammar feedback in the criteria condition was 0.32, whereas in the CJ condition this was only 0.13. There were no significant differences between students (Wald z = 1.30, p = 0.10) and essays (Wald z = 0.49, p = 0.32).

Third, the probability of feedback on coherence and unity (0.42) was not significantly different from 0.50 (t = −0.95, p = 0.34), indicating that when students described strengths in a text, they commented on aspects that were related to coherence and unity half of the time. There were, however, large differences between students (Wald z = 2.25, p < 0.05): some students hardly provided feedback on coherence, whereas other students focused on coherence in more than three quarters of the cases {80% CI [0.13, 0.77]}. There was no effect of condition (t = 0.09, p = 0.93) and there were no significant differences between essays (Wald z = 1.09, p = 0.28). When students commented on weaknesses in the text, the probability that they focused on coherence and unity in the text was only 0.21. There was no effect of condition (t = 0.05, p = 0.96), and there were no significant differences between students (Wald z = 0.91, p = 0.18) and essays (Wald z = 1.32, p = 0.08).

Fourth, the results for feedback on vocabulary are quite comparable to the results for feedback on grammar. The proportion of positive feedback on vocabulary was 0.11 (t = −4.51, p < 0.001). There was no effect of condition (t = −1.29, p = 0.20), and there were no significant differences between students (Wald z = 1.57, p = 0.06) and essays (Wald z = 0.69, p = 0.49). In contrast, the proportion of negative feedback on grammar was generally higher, with a negative effect of condition as well (t = −3.79, p < 0.001). Specifically, the proportion of grammar feedback in the criteria condition was 0.31, compared to 0.10 for the students in the CJ condition. There were no significant differences between students (redundant) and essays (Wald z = 1.16, p = 0.13).

Fifth, students in both conditions hardly provided feedback on aspects that could not be categorized in any of the other four evaluation criteria, with a probability of 0.01 in both categories. Although students in the CJ condition mentioned somewhat more miscellaneous aspects, there were no significant differences between condition (t < 1.70, p > 0.09). Only for negative feedback there were significant differences between students (Wald z = 1.86, p < 0.03).

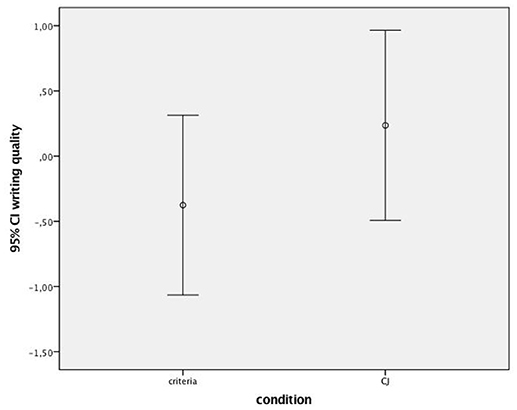

Quality of Writing Performance

Results indicated that students in the CJ-based peer assessment condition wrote texts of higher quality (M = 0.24, SD = 1.56) than students in the criteria-based peer assessment condition (M = −0.38, SD = 1.47), see also Figure 3. The average scores are presented in logits, which represent the probability that a particular text is judged as being of higher quality than a random text from the same pool of texts. In other words, the probability on high-quality texts was generally higher for students in the CJ condition (0.56) than for students in the criteria condition (0.41). An independent t-test revealed that the effect in this sample was moderate (Cohens' d = 0.40), but statistically non-significant, t(38) = −1.28, p = 0.21. An additional analysis of covariance in which the effect of condition on writing quality was controlled for students' knowledge and self-efficacy for writing provided equal results, F(1, 33) = 3.48, p = 0.22, R2 = 0.20.

Figure 3. This graph shows the overlap in the 95% Confidence Intervals of the mean scores for writing quality between the criteria and comparative judgment condition.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the differential learning effects of an instructional approach in which students apply analytic teacher-designed criteria to the evaluation of essays written by peers vs. an instructional approach in which students evaluate by comparison. This was tested in a small-scale authentic classroom situation, showing some interesting and promising findings. First, there were no difference in the reliability and validity of the judgments students made in each of the two conditions, indicating that both types of peer assessments equally support students in making evaluative judgments of the quality of their peers' essays. However, there were some differences between conditions in the content of the peer feedback they provided. Compared to the criteria condition, students in the comparative judgment condition focused relatively more on aspects that were related to the content and structure of the text, and less so on aspects that were related to grammar and vocabulary. This was only the case for feedback targeted to aspects that needed improvement. For feedback on strengths, there appeared to be no difference between conditions. A second important finding of this study is that there appeared to be only a moderate effect of condition on the quality of students' own writing. Students in the comparative judgment condition wrote texts of somewhat higher quality than the students in the criteria condition. This difference was not significant in this sample, but that can be due to the relatively small sample size (cf. Wasserstein and Lazar, 2016). A posterior power analysis indicates that at least 98 students are needed per condition to have 80% power for detecting the moderate sized effect of 0.40 when employing the criterion level of 0.05 for statistical significance.

Two main conclusions can be drawn from these results. First and foremost, the instructional approaches influence the aspects of the text to which students pay attention when providing feedback. Although students in this study were all primarily focused on the content and structure of the text, especially when they provided positive feedback, they were more directed toward the lower level aspects of the text when they needed to provide suggestions for improvement based on an analytic list of criteria. However, when comparing essays, students stayed focused on the higher order aspects when identifying aspects that needed improvement. This finding might be due to the holistic approach in the process of comparative judgment, which allow students to make higher level judgments regarding the essay's communicative effectiveness.

Although it is not necessarily a bad thing to provide feedback on lower level aspects, feedback on higher level aspects is generally associated with improved writing performance (Underwood and Tregidgo, 2006). By doing so, the feedback in the comparative judgment condition can be more meaningful for the feedback receiver. Ultimately, this can also have an effect on feedback givers themselves as the way they evaluate texts and diagnose strengths and weaknesses in a peer's work may have an important influence on how they conceptualize and regulate quality in their own writing (Nicol and Macfarlane Dick, 2006; Nicol et al., 2014).

Second, conclusions regarding the effect of instructional approach on student's own writing performance are somewhat harder to draw based on the results of the present study. Although students in the comparative judgment condition on average wrote texts of higher quality than students in the criteria condition, this was definitely not the case for all students. Even when controlled for individual writing knowledge and writing self-efficacy, differences in writing quality were still larger within conditions than between conditions. Moreover, as the present study took place in an authentic classroom situation constraining the number of participating students, and as it is not ethical to exclude students from possible learning opportunities, it was deliberately decided not to implement a control condition in which students completed the same writing task without being presented with examples. As a result, students in both conditions actively engaged with a range of examples of varying quality. As this process seems to be a necessary condition for students to develop a mental representation of what constitutes quality (Lin-Siegler et al., 2015; Tai et al., 2017), it could very well be the case that students in both conditions significantly improved their writing. More research is needed to examine whether the active use of shared criteria and examples in a peer assessment affects students' learning and performance, above and beyond the instructional approach (teacher-designed criteria or comparative judgment). Another opportunity for further research is to investigate how many examples of which quality are necessary for students to learn.

A possible explanation for the small effects in this study of the learning by comparison condition on students' writing quality may be that improved understanding of writing quality does not easily transfer to one's own writing, at least not on the short time. Further research is needed to understand what instructional factors can foster this transfer. For instance, the learning effects might be stronger once the peer assessment is routinely and systematically implemented in the curriculum. According to Sadler (1998), any feedback-enhanced intervention in which students are engaged in the process of assessing quality must be carried out long enough for it will be viewed by learners as normal and natural (p. 78). To our knowledge, there is no research yet that investigates how the number of peer assessments performed over the course of a curriculum affects students' performance.

The role of the teacher in the transfer from understanding to performance may be a crucial factor as well. Key aspects of pedagogical interventions that successfully promote student's learning include a combination of direct instruction, modeling, scaffolding and guided practice (Merrill, 2002). This implies that a peer assessment on its own may not be sufficient to improve writing. A more effective implementation of any type of peer assessment may be that teachers discuss the results from the peer assessment with students and show how they can use the information from the peer assessment during their own writing process (Sadler, 1998, 2009; Rust et al., 2003; Hendry et al., 2011, 2012; Carless and Chan, 2017). This may be especially true for comparative judgment in which students gradually develop their own understanding of criteria and standards for writing quality through comparing a range of texts from low to high quality, but without any explicit information and/or teacher guidance on the accuracy of their internally constructed standard of quality. At the end of the present study, students in comparative judgment condition confirmed that they missed explicit clues on whether they made the right choices during their comparisons. While acknowledging the importance of teachers, Sadler (2009) remarks that teachers should hold back from being too directive in guiding students' learning process. He states that students assume that teachers are the only agents who can provide effective feedback on their work and that they need a considerable period of practice and adaptation to build trust in the feedback they give and receive from peers, especially when they do this in a more holistic manner. When teachers are too directive in this procedure and keep focusing on analytic criteria instead of on the quality of texts as a whole, students' own learning process might be inhibited. Instead he argues that teachers should guide the process more indirectly, for instance, through monitoring students' evaluation process from a distance and by providing meta-feedback on the quality of students' peer feedback. Together, this implies that a combination of both instructional methods might be more effective than either of them, and that teachers play an important role in how to bring criteria and examples together in such a way that students engage in deep learning processes.

Although the present study provides important insights into how students evaluate work of their peers and what aspects they take into account during these evaluations, the results do not provide any insight into how they evaluate their own work during writing. Theories on evaluative judgment suggest that improved understanding of what constitutes quality does not only improve how students evaluate the work of their peers but also how they evaluate their own work (Boud, 2000; Tai et al., 2017). Although writing researchers have already acquired a decent understanding of how novice and more advanced writers plan their writing product, there is not much information yet on how students evaluate and revise their writing. This is especially relevant for developing writers, as being able to monitor and control the quality of one's own product during writing is one of the most important predictors of writing quality (Flower and Hayes, 1980). Based on the small effects of peer assessment on writing quality in this research it might very well be possible that students have made changes in their writing process. To further our understanding of the learning effects of peer assessment in the context of writing, research should therefore take into account both the process and the product of writing.

Conclusion

To summarize, the present study has taken a first but promising step into unraveling how analyzing examples of varying quality might foster students' understanding and performance in writing. It has been demonstrated that students analyze example texts quite differently by comparison than by applying teacher-designed criteria. In particular, when providing feedback in a comparative approach, students focus more on higher level aspects in their peers' texts. Although the results are not conclusive in whether the effects of learning by comparison also transfer to students' own writing performance, the results do suggest that it can be a powerful instructional tool in today's practice. It inherently activates students to engage with a range of examples of varying quality, doing so in a highly feasible and efficient manner (cf. Bartholomew et al., 2018a). Follow-up research is needed to really get a grip on the potential learning effects of comparative judgment, both to contrast the effects to other instructional approaches such as linking example texts to analytic criteria which is now regularly used in educational practice, but also with regards to contextual factors that are needed for an optimal implementation in practice.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Antwerp. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Flanders Innovation & Entrepreneurship and the Research Foundation [Grant No. 130043].

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bartholomew, S. R., Nadelson, L. S., Goodridge, W. H., and Reeve, E. M. (2018a). Adaptive comparative judgment as a tool for assessing open-ended design problems and model eliciting activities. Edu. Assess. 23, 85–101. doi: 10.1080/10627197.2018.1444986

Bartholomew, S. R., Strimel, G. J., and Yoshikawa, E. (2018b). Using adaptive comparative judgment for student formative feedback and learning during a middle school design project. Int. J. Technol. Des. Edu. Adv. 1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10798-018-9442-7

Bell, A., Mladenovic, R., and Price, M. (2013). Students' perceptions of the usefulness of marking guides, grade descriptors and annotated exemplars. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 38, 769–788. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.714738

Bloxham, S., and Campbell, L. (2010). Generating dialogue in assessment feedback: exploring the use of interactive cover sheets. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 35, 291–300. doi: 10.1080/02602931003650045

Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable assessment: rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies Contin. Edu. 22, 151–167. doi: 10.1080/713695728

Bouwer, R., Béguin, A., Sanders, T., and Van den Bergh, H. (2015). Effect of genre on the generalizability of writing scores. Lang. Test. 32, 83–100. doi: 10.1177/0265532214542994

Bouwer, R., Goossens, M., Mortier, A. V., Lesterhuis, M., and De Maeyer, S. (2018). “Een comparatieve aanpak voor peer assessment: Leren door te vergelijken [A comparative approach for peer assessment: Learning by comparison],” in Toetsrevolutie: Naar een feedbackcultuur in het hoger onderwijs [Assessment Revolution: Towards a Feedback Culture in Higher Education], eds D. Sluijsmans and M. Segers (Culemborg: Phronese), 92–106.

Bradley, R. A., and Terry, M. E. (1952). Rank analysis of incomplete block designs: I. The method of paired comparisons. Biometrika 39, 324–345. doi: 10.1093/biomet/39.3-4.324

Brookhart, S. M. (2018). Appropriate criteria: key to effective rubrics. Front. Edu. 3:22. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00022

Bruning, R., Dempsey, M., Kauffman, D. F., McKim, C., and Zumbrunn, S. (2013). Examining dimensions of self-efficacy for writing. J. Edu. Psychol. 105, 25–38. doi: 10.1037/a0029692

Carless, D., and Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Carless, D., and Chan, K. K. H. (2017). Managing dialogic use of exemplars. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 42, 930–941. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1211246

D-PAC [Computer software] (2018). D-PAC [Computer software]. Antwerp: University of Antwerp. Available online at: http://www.d-pac.be.

Fielding, A., and Goldstein, H. (2006). Cross-Classified and Multiple Membership Structures in Multilevel Models: an Introduction and Review (Report no. 791). London: DfES.

Flower, L., and Hayes, J. (1980). “The dynamics of composing: making plans and juggling constraints,” in Cognitive Processes in Writing, eds L. Gregg and E. Steinberg (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 3–30.

Fraile, J., Panadero, E., and Pardo, R. (2017). Co-creating rubrics: the effects on self-regulated learning, self-efficacy and performance of establishing assessment criteria with students. Stud. Edu. Eval. 53, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.03.003

Gentner, D., Loewenstein, J., and Thompson, L. (2003). Leaning and transfer: a general role for analogical encoding. J. Edu. Psychol. 95, 393–408. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.393

Gill, T., and Bramley, T. (2013). How accurate are examiners' holistic judgments of script quality? Assess. Edu. 20, 308–324. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2013.779229

Handley, K., and Williams, L. (2011). From copying to learning: using exemplars to engage students with assessment criteria and feedback. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 36, 95–108. doi: 10.1080/02602930903201669

Hendry, G. D., Armstrong, S., and Bromberger, N. (2012). Implementing standards-based assessment effectively: incorporating discussion of exemplars into classroom teaching. Assess. Eval. Higher Edc. 37, 149–161. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2010.515014

Hendry, G. D., Bromberger, N., and Armstrong, S. (2011). Constructive guidance and feedback for learning: the usefulness of exemplars, marking sheets and different types of feedback in a first year law subject. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 36, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/02602930903128904

Huisman, B., Saab, N., van Driel, J., and van den Broek, P. (2018). Peer feedback on academic writing: undergraduate students' peer feedback role, peer feedback perceptions and essay performance. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 43, 955–968 doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1424318

Jones, I., and Alcock, L. (2014). Peer assessment without assessment criteria. Stud. Higher Edu. 39, 1774–1787. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.821974

Jones, I., and Wheadon, C. (2015). Peer assessment using comparative and absolute judgment. Stud. Edu. Eval. 47, 93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.09.004

Kok, E. M., de Bruin, A. B. H., Robben, S. G. F., and van Merriënboer, J. J. G. (2013). Learning radiological appearances of diseases: does comparison help? Learn. Instruct. 23, 90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.07.004

Lin-Siegler, X., Shaenfield, D., and Elder, A. D. (2015). Contrasting case instruction can improve self-assessment of writing. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 63, 517–537. doi: 10.1007/s11423-015-9390-9

Merrill, M. D. (2002). First principles of instruction. Edu. Technol. Res. Dev. 50, 43–59. doi: 10.1007/BF02505024

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., and Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: a peer review perspective. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 39, 102–122. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.795518

Nicol, D. J., and Macfarlane Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. Higher Edu. 31, 199–218. doi: 10.1080/03075070600572090

Orsmond, P., Merry, S., and Reiling, K. (2002). The use of exemplars and formative feedback when using student derived marking criteria in peer and self-assessment. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 27, 309–323. doi: 10.1080/0260293022000001337

Patchan, M., Charney, D., and Schunn, C. D. (2009). A validation study of students' end comments: comparing comments by students, a writing instructor, and a content instructor. J. Writing Res. 1, 124–152. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2009.01.02.2

Patton, C. (2012). Some kind of weird, evil experiment: student perceptions of peer assessment. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 37, 719–731. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2011.563281

Peng, C. Y. J., Lee, K. L., and Ingersoll, G. M. (2002). An introduction to logistic regression analysis and reporting. J. Edu. Res. 96, 3–14. doi: 10.1080/00220670209598786

Pollitt, A. (2004). “Let's stop marking exams,” Paper Presented at the Conference International Association of Educational Assessment (Philadelphia, PA).

Rust, C., Price, M., and O'Donovan, B. (2003). Improving students' learning by developing their understanding of assessment criteria and processes. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 28, 147–164. doi: 10.1080/0260293032000045509

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instruct. Sci. 18, 119–144.

Sadler, D. R. (1998). Formative assessment: revisiting the territory. Assess. Edu. Princ. Pol. Prac. 5, 77–84.

Sadler, D. R. (2002). “Ah!…So That's “Quality,” in Assessment: Case Studies, Experience and Practice from Higher Education, eds P. Schwartz and G. Webb (London: Kogan Page), 130–136.

Sadler, D. R. (2009). “Transforming holistic assessment and grading into a vehicle for complex learning,” in Assessment, Learning and Judgment in Higher Education, ed G. Joughin (Dordrecht: Springer), 1–19.

Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 35, 535–550. doi: 10.1080/02602930903541015

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., and Panadero, E. (2017). Developing evaluative judgment: enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Edu. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3

To, J., and Carless, D. (2016). Making productive use of exemplars: peer discussion and teacher guidance for positive transfer of strategies. J. Further Higher Educ. 40, 746–764. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2015.1014317

Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assess. Educ. 14, 281–294. doi: 10.1080/09695940701591867

Underwood, J. S., and Tregidgo, A. P. (2006). Improving student writing through effective feedback: best practices and recommendations. J. Teach. Writing 22, 73–98.

Verhavert, S., De Maeyer, S., Donche, V., and Coertjens, L. (2017). Scale separation reliability: what does it mean in the context of comparative judgment? Appl. Psychol. Meas. doi: 10.1177/0146621617748321

Wasserstein, R. L., and Lazar, N. A. (2016). The ASA's statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. Am. Statist. 70, 129–133. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108

Yucel, R., Bird, F. L., Young, J., and Blanksby, T. (2014). The road to self-assessment: exemplar marking before peer review develops first-year students' capacity to judge the quality of a scientific report. Assess. Eval. Higher Edu. 39, 971–986. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2014.880400

Zimmerman, B. J., and Risemberg, R. (1997). Becoming a self-regulated writer: a social cognitive perspective. Contempor. Educat. Psychol. 22, 73–101.

Appendix

Keywords: criteria, comparative judgment, exemplars, peer assessment, writing, evaluative judgment

Citation: Bouwer R, Lesterhuis M, Bonne P and De Maeyer S (2018) Applying Criteria to Examples or Learning by Comparison: Effects on Students' Evaluative Judgment and Performance in Writing. Front. Educ. 3:86. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00086

Received: 30 April 2018; Accepted: 14 September 2018;

Published: 11 October 2018.

Edited by:

Frans Prins, Utrecht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Jill Willis, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaPeter Ralph Grainger, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

Copyright © 2018 Bouwer, Lesterhuis, Bonne and De Maeyer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renske Bouwer, cmVuc2tlLmJvdXdlckB2dS5ubA==

Renske Bouwer

Renske Bouwer Marije Lesterhuis

Marije Lesterhuis Pieterjan Bonne

Pieterjan Bonne Sven De Maeyer

Sven De Maeyer