- Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Since the launch of the Whole School Approach to Integrated Education (WSA) in 1997, mainstream schools in Hong Kong have been admitting an increasing diversity of learners. They include, for example, children identified with different categorical learning needs, and more recently those who learn Chinese as a second language. Nonetheless, many teachers in this predominantly Chinese community remain skeptical to date about their pedagogical capacity for achieving greater inclusion. This paper discusses the contextual challenges of glocalizing inclusive quality education in Hong Kong. In response to the teachers' concern about their professional readiness to support the learning of all children, it proposes a research framework for understanding their inclusive pedagogy—as a bottom-up approach to inform the development of more cultural-specific inclusive teacher education therein.

Toward Inclusive Quality Education

In 2015, the United Nations launched the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015a). As a global action plan, it aims to stimulate local responses in areas of critical importance for humanity and the planet over the next 15 years. One of its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) concerns achieving inclusive and equitable quality education for all. It calls for more inclusive practices that support the increasing diversity of learners in different local settings, not least when global enrolment in education has increased significantly since the preceding Millennium Development Goals (United Nations, 2015b).

Prior to the SDGs, this paradigm shift from providing access to facilitating inclusion has already started to occur in many educational contexts with long histories of compulsory school attendance (Rouse, 2006). In the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR)1, for example, an education blueprint titled Quality School Education (aka ECR7) was published in September 1997. It highlights the importance of, inter alia, developing quality indicators, establishing quality assurance mechanism, and raising the professional standards of principals and teachers (Education Commission, 2010). Based on this local quality framework, a series of policy initiatives was announced in the following years. Some examples were Information Technology for Learning in 1998, Whole School Approach to Integrated Education (WSA) in 1999, Language Proficiency Requirement for English and Putonghua Teachers in 2000, and Basic Competency Assessments in 2004 (Education Bureau, 2007; Chong, 2012).

This official “quality turn” (Cheng, 2002, p. 48), however, was not particularly welcomed by many local teachers. For instance, more than 1,000 of them expressed in a survey that the “frequently changing education policies” and “pupil's problems” had caused them considerable pressure (Chan, 2002). In relation to the growing concern about teachers' wellbeing and the stress confronting them, the Committee on Teachers' Work2 recommended in particular a review of the WSA in 2006:

There can be no doubt that the diversity in student ability, together with students' behavioral problems and interruptions in learning, is stressful and burdensome to teachers. The Education and Manpower Bureau should continue its review of Integrated Education, and work closely with schools, Teacher Education Institutions, and outside bodies (e.g., educational psychologists, voluntary agencies, parents' group, etc.) in the formulation of support measures to tackle special educational needs and student diversity (Committee on Teachers Work, 2006, p. 41).

The message here seems clear: the expanding and diversifying school population has somehow exceeded teachers' capacity to respond (Davis and Florian, 2004)—a phenomenon emerging not only in Hong Kong but also across the globe amid the worldwide trend toward more inclusive quality education (Sharma et al., 2008). Within various European contexts, for example, the majority of teachers have considered responding to individual learner differences as one of the biggest challenges in their inclusive classrooms (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education, 2001). In light of this, international research has started to explore how effective pedagogy for all learners might be developed (e.g., James and Pollard, 2011), and their participation facilitated (e.g., Black-Hawkins, 2010).

Whole School Approach to Integrated Education

According to Morris and Scott (2003), many international educational reforms designed to improve the quality of schooling tend to be rhetorical than substantive in their pedagogical impact. The same may apply to the WSA in Hong Kong. As the local education for all policy, it set out to explore how students identified with special educational needs might be integrated effectively into mainstream schools (Lian, 2004). Although the development of integrated special needs education has been advocated as an approach to inclusive schooling since the Salamanca Statement in 1994 (UNESCO, 1994), practitioners in Hong Kong appear to have considerable reservations about its practicality. While over 70 schools had been contacted during the recruitment process (Crawford et al., 1999), only nine of them joined the pilot scheme of the WSA in 1997. They were provided with extra resources and professional support to accommodate a total of 48 students identified with “mild grade mental handicap,” “hearing impairment,” “visual impairment,” “physical handicap,” and “autistic disorder with average intelligence” (Education Department, 2002).

Two years later, an official evaluation of this pilot—commissioned by the former Hong Kong Education and Manpower Bureau—concludes that many teachers were doubtful whether the needs of “disabled” children could best be met through integration (Crawford et al., 1999), not least because they had found it hard to support the learning of all children in practice (Cheng, 2007). Mittler (1998) argues in another review that the WSA can generate a positive impact on the pedagogy and organizational thinking of mainstream schools. This assertion, however, may seem more relevant to understanding educational inclusion, wherein systemic changes are expected in addition to integration (Nind, 2005).

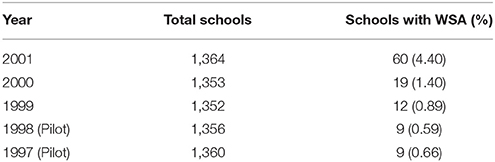

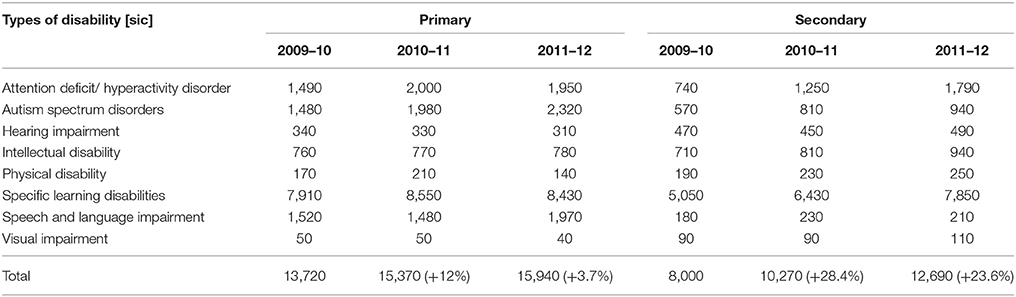

Despite a lack of broad consensus on the effectiveness of integration in context, the WSA has been formally adopted as a nationwide policy since 1999. Underpinning this control model of implementation (Morris and Scott, 2003) appears to be a belief that it can nevertheless improve the overall quality of education. Whilst concerns have been raised over the professional readiness of those responsible for teaching the increasing diversity of learners (Poon-Mcbrayer, 2014), figures from 1997 to 2001 show that schools responded rather positively to the administration's call for greater integration (Census and Statistics Department, 2002; Hui and Dowson, 2003; Luk-Fong, 2005) (see Table 1). As one of the long-term consequences of the WSA, more “disabled” pupils have gained access to mainstream education in the HKSAR to date (see Table 2). In recent years, the newly-admitted school population has also included newly-arrived children from the Chinese mainland, and those who learn Chinese as a second language. However, this growing proportion of integrated learners alone may tell us very little about the inclusivity of learning and teaching. For example, some public sector schools in Hong Kong were criticized for not spending the extra funding they received for the benefit of their increasing diversity of learners (Subcommittee on Integrated Education, 2014). Although most teachers may agree in principle to the integration of some, many remain skeptical about their pedagogical capacity for supporting the learning of all (see, for example, Chao et al., 2016).

Table 1. Whole School Approach to Integrated Education - Statistics (Census and Statistics Department, 1990; Hui and Dowson, 2003; Luk-Fong, 2005).

Table 2. Students by major types of identified disability [sic] studying in mainstream primary and secondary schools (Legislative Council Secretariat, 2012).

Exploring Inclusive Pedagogy

Forlin (2010) points out that a barrier to inclusive education worldwide concerns teachers' (perceived) lack of necessary knowledge and skills to carry out their work. This has called for the development of more inclusive pedagogy that supports the learning of all children. Lewis and Norwich (2005), for example, emphasize the importance of a solid “teaching knowledge base” (p. 9) to pedagogies for inclusion. It comprises knowledge of the curriculum subject area, knowledge of the learning process, and knowledge of the learners. Rouse (2008) argues that developing effective inclusive practice requires teachers to not only reconsider their beliefs (believing) and do things differently (doing), but also extend their knowledge (knowing). Some examples are knowing how children learn, what strategies are available, as well as how learning can be appropriately assessed and monitored. Rix et al. (2009) highlight in their systematic literature review the relevance of subject-specific curriculum skills to effective inclusive teaching. All these hypotheses, contrary to those which suggest specialist teaching for some (e.g., Kauffman et al., 2005), consider teachers' repertoires of knowledge and skills as the key to inclusive teaching for all. More importantly, they acknowledge teaching a diversity of learners as a manageable professional challenge for all teachers. This premise supports, for example, the observation that guidance on inclusion through the National Strategies in England tends to emphasize the strengthening of generic teaching, rather than the development of specialist approaches (Ellis et al., 2008).

Based on this theoretical underpinning of inclusive pedagogy, Florian and Linklater (2010) assert the importance of preparing teachers to make the best use of what they already know when learners experience difficulty in the inclusive classroom. According to Rouse (2008), many teachers do not act upon their knowledge of good practice when they support the increasing diversity of learners. That is, they do not translate fully their pedagogical “knowing” into inclusive “doing.” The reason behind this knowledge-practice gap is hitherto speculative. Kershner (2014), for instance, criticizes existing theories as “somewhat fragmentary and inconsistent” (p. 843) to inform teaching in highly contextualized settings. Black-Hawkins et al. (2008), on the other hand, suggest that teachers will only develop an inclusive pedagogical approach when they believe in their ability to make a difference, as well as the transformability of learning capacity (Hart et al., 2004). Given our limited understanding of this inclusive decision-making, and more specifically the challenges that many Hong Kong teachers face when they “do” inclusion, what research, then, might be useful for informing inclusive teacher education in the context (see also Li, 2014)?

What Do Teachers Believe About Teaching a Diversity of Learners?

First, previous research has suggested that many barriers to greater inclusion within the Hong Kong classroom are closely related to teachers' philosophy and attitudes. One example is the Confucian collectivist value that tends to favor uniformity over diversity. According to Cheng (2007), this has induced in the HKSAR a “rigidly defined curriculum” (p. 38) that is centrally controlled by local government authorities, including the Curriculum Development Council, the Curriculum Development Institute, the Hong Kong Examination and Assessment Authority, and the Education Bureau. Against this sociocultural backdrop, what do teachers believe about teaching a diversity of learners? A body of literature has proposed that teachers' attitudes to inclusion tend to be positively correlated to their familiarity with teaching more diverse groups of learners (e.g., Nind, 2005; Forlin et al., 2014). This resonates with conceptualizing inclusive pedagogy as the accumulated professional craft knowledge of teachers (Hagger and McIntyre, 2006; Black-Hawkins and Florian, 2012; Florian and Beaton, 2017). It is therefore of research significance to explore whether practitioners in the HKSAR, owing to their increased exposure to the growing integrated student population in the past two decades, have strengthened their beliefs about teaching a diversity of learners (e.g., their self-efficacy, and their attitudes toward the WSA). By gaining an emic understanding of their views on, and experiences about, supporting the learning of all students in the context, the inquiry may provide an inclusive perspective (Seale et al., 2014) upon whether the WSA is the right option for fostering quality education in the HKSAR, especially amid its ensuing top-down approach to policy implementation.

What Do Teachers Do in Practice to Support the Learning of All Students?

Second, prior studies have consistently illustrated the uniqueness of pedagogy in the Chinese classroom (e.g., Watkins and Biggs, 2001). For instance, while literature written in English has agreed on the effectiveness of a “peer-group interactive approach” (p. 92) in the inclusive setting (Rix et al., 2009), Phillipson (2007) points out that Chinese learners do not prefer working in groups in class. Rather, they are usually perceived as passive learners from the Western point of view. These contrasting perspectives on teaching and learning may show the limitations of transplanting across cultures a teaching approach, without considering the context in which it is to be applied (Rao and Yuen, 2007; Li, 2018). Based on her 2-year case study with a Hong Kong primary school adopting the WSA, Luk-Fong (2005) criticizes the “export of Western practice” (p. 101) to the pre-dominantly Chinese community. She calls for new theories to understand the phenomenon in Hong Kong vis-à-vis its unique cultural setting.

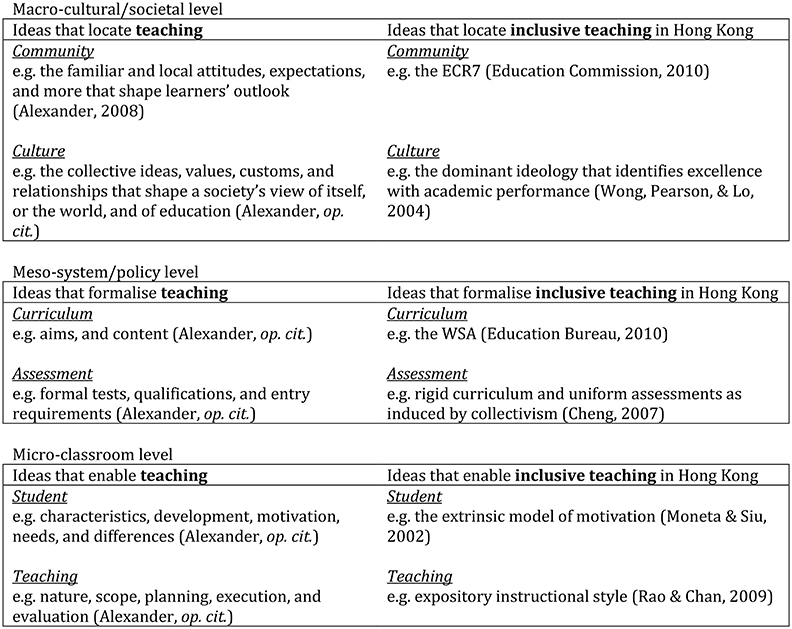

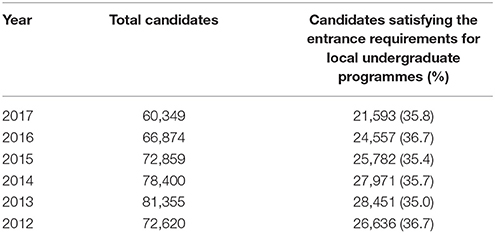

Alexander (2008) conceptualizes pedagogy as an ecological construct—a joint enterprise between teaching and the values, evidence, theories, as well as collective histories that inform it. Figure 1 below exemplifies how this constructivist framework for theorizing pedagogy might support an empirical understanding of inclusive pedagogy in Hong Kong. For instance, the dominant ideology of the Confucian-heritage Culture tends to identify excellence with students' academic performance in standardized summative assessments (Wong et al., 2004). In Hong Kong, most local students are expected to take the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination (HKDSE) when the complete Grade 12. Nonetheless, only less than half of them are able to “achieve” in this nationwide university entrance test every year (see Table 3). According to Moneta and Siu (2002), these high achievers appear to be those who are extrinsically motivated. They argue that it is partly because the school environment in the HKSAR penalizes students for, and thus discourages, their intrinsic motivation. Amid these pedagogical surroundings, what do teachers do in practice to support the learning of all students? Given the theoretical uniqueness of pedagogy, Figure 1 offers some starting points for understanding not only teachers' inclusive practices per se, but also the “dialectical relationship(s)” (Tsui, 2003, p. 67) between these inclusive practices and their macro-cultural, meso-systemic, and micro-classroom contexts.

Table 3. Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education Examination - Statistics (Hong Kong Examination and Assessment Authority, 2018).

The Way Forward

In relation to the global movement toward inclusive quality education, this paper discussed in particular some challenges facing the local education for all policy in Hong Kong. It argued that the further glocalization of this international rhetoric involves an understanding of local teachers' inclusive pedagogy, including their “believing” about teaching a diversity of learners, and their “doing” that supports the learning of all students. It also proposed a research framework to examine the multi-layered construct of their inclusive pedagogy within the wider socio-cultural setting. If inclusive quality education is to be glocalized worldwide, more empirical efforts are needed to explore how this global policy might be realized pedagogically in different local contexts through and with their teachers.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer TZ and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Footnotes

1. ^The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) was established on 1 July 1997 when China resumed the exercise of sovereignty over the former British Dependent Territory.

2. ^The Committee on Teachers' Work is an independent committee formed by the HKSAR government in 2006 to study the workload of teachers, and recommend measures to reduce the pressure on them.

References

Black-Hawkins, K. (2010). The framework for participation: a research tool for exploring the relationship between achievement and inclusion in schools. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 33, 21–40. doi: 10.1080/17437271003597907

Black-Hawkins, K., and Florian, L. (2012). Classroom teachers' craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teach. Teach. 18, 567–584. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2012.709732

Black-Hawkins, K., Florian, L., and Rouse, M. (2008). Achievement and Inclusion in Schools and Classrooms: Participation and Pedagogy. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?

Census and Statistics Department (1990). Hong Kong Annual Digest of Statistics. Hong Kong: The Government Printer.

Census Statistics Department (2002). Hong Kong Annual Digest of Statistics. Available online at: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B10100032002AN02B0500.pdf

Chan, F. (2002). Stress Turns Teachers' Thoughts to Self-Harm. South China Morning Post. Available online at: http://www.scmp.com/article/394424/stress-turns-teachers-thoughts-self-harm

Chao, C. N. G., Forlin, C., and Ho, F. C. (2016). Improving teaching self-efficacy for teachers in inclusive classrooms in Hong Kong. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 20, 1142–1154. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1155663

Cheng, K. (2002). “The quest for quality education: the quality assurance movement in Hong Kong,” in Globalization and Education: The Quest for Quality Education in Hong Kong, eds J. K. Mok and D. K. Chan (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press).

Cheng, C. (2007). Challenges posed on inclusive education in Hong Kong and their implications for educational provision and intervention. Hong Kong Special. Educ. Forum 9, 32–46.

Chong, S. (2012). The Hong Kong policy of quality education for all: a multi-level analysis of its impacts on newly arrived children. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 16, 235–247. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2010.481430

Committee on Teachers Work (2006). Final Report. Available online at: http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr06-07/english/panels/ed/papers/ed0212cb2-1041-6-e.pdf

Crawford, N., Heung, V., Yip, E., and Yuen, C. (1999). Integration in Hong Kong: where are we now and what do we need to do? Hong Kong Special. Educ. Forum 2, 1–13.

Davis, P., and Florian, L. (2004). Teaching Strategies and Approaches for Pupils With Special Educational Needs: A Scoping Study. Available online at: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/6059/1/RR516.pdf

Education Bureau (2007). Consultancy Reports. Available online at: http://www.edb.gov.hk/en/about-edb/publications-stat/major-reports/consultancy-reports/index.html (accessed December 31, 2017).

Education Commission (2010). Education Commission Report no.7: Quality School Education. Available online at: http://www.edb.gov.hk/en/about-edb/publications-stat/major-reports/consultancy-reports/edu-commission-report-7/index.html (accessed December 31, 2017).

Education Department (2002). Support for Students With Learning Difficulties in Mainstream Schools. Available online at: http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr01-02/english/panels/ed/papers/ed0228cb2-1171-4e.pdf

Ellis, S., Tod, J., and Graham-Matheson, L. (2008). Special Educational Needs and Inclusive Report: Reflection and Renewal. Available online at: https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/ddacdcb2-3cba-4791-850f32216246966e.pdf

European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (2001). Inclusive education and effective classroom practices. European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education. Available online at: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/inclusive-education-and-effective-classroom-practice_IECP-Literature-Review.pdf

Florian, L., and Beaton, M. (2017). Inclusive pedagogy in action: getting it right for every child. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1412513

Florian, L., and Linklater, H. (2010). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: using inclusive pedagogy to enhance teaching and learning for all. Cambridge J. Educ. 40, 369–386. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2010.526588

Forlin, C., Sharma, U., and Loreman, T. (2014). Predictors of improved teaching efficacy following basic training for inclusion in Hong Kong. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 18, 718–730. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2013.819941

Forlin, C. (2010). Teacher education reform for enhancing teachers' preparedness for inclusion. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 14, 649–653. doi: 10.1080/13603111003778353

Hagger, H., and McIntyre, D. (2006). Learning Teaching From Teachers: Realising the Potenetial of School-Based Teaching Education. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Hart, S., Dixon, A., Drummond, M. J., and McIntyre, D. (2004). Learning Without Limits. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Hong Kong Examination Assessment Authority (2018). Examination Report. Available online at: http://www.hkeaa.edu.hk/en/hkdse/assessment/exam_reports/ (Accessed April 7, 2018).

Hui, M. L. H., and Dowson, C. R. (2003). “The development of inclusive education in Hong Kong,” in Inclusive Education in the New Millennium eds M. L. H. Hui, C. R. Dowson, and M. G. Moont (Hong Kong: Education Convergence), 11–24.

James, M., and Pollard, A. (2011). TLRP's ten principles for effective pedagogy: Rationale, development, evidence, argument and impact. Res. Pap. Educ. 26, 275–328. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2011.590007

Kauffman, J. M., Landrum, T. J., Mock, D., Sayeski, B., and Sayeski, K. S. (2005). Diverse knowledge and skills require a diversity of instructional groups: a position statement. Remed. Spec. Edu. 26, 2–6. doi: 10.1177/07419325050260010101

Kershner, R. (2014). “What do classroom teachers need to know about meeting special educational needs?” in The SAGE Handbook of Special Education, ed L. Florian (Los Angeles, CA: SAGE).

Legislative Council Secretariat (2012). Integrated Education. Available online at: http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr11-12/english/panels/ed/papers/ed0710cb2-2518-2-e.pdf

Lewis, A., and Norwich, B. (2005). Special Teaching for Special Children? Pedagogies for Inclusion. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Li, E. (2014). Preparing teachers in Hong Kong to support inclusion: A cultural framework for inclusive teacher education. Hong Kong J. Spec. Educ. 16, 48–54.

Li, E. (2018). Towards Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education for All: To Borrow or not to Borrow? BERA Blog. Available online at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/towards-inclusive-and-equitable-quality-education-for-all-to-borrow-or-not-to-borrow

Lian, M. G. J. (2004). Inclusive education: theory and practice. Hong Kong Spec. Educ. For. 7, 57–74.

Luk-Fong, P. Y. Y. (2005). Managing change in an integrated school: a Hong Kong hybrid experience. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 9, 89–103. doi: 10.1080/1360311042000299766

Moneta, G. B., and Siu, C. M. Y. (2002). Trait intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, academic performance, and creativity in Hong Kong college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 43, 664–683.

Morris, P., and Scott, I. (2003). Educational reform and policy implementation in Hong Kong. J. Educ. Policy 18, 71–84. doi: 10.1080/0268093032000042218

Nind, M. (2005). Inclusive education: discourse and action. Br. Educ. Res. J. 31, 269–275. doi: 10.1080/0141192052000340251

Phillipson, S. N. (2007). “The regular Chinese classroom,” in Learning Diversity in the Chinese Classroom: Contexts and Practice for Students With Special Needs, ed S. N. Phillipson (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press), 3–33.

Poon-Mcbrayer, K. F. (2014). The evolution from integration to inclusion: the Hong Kong tale. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 18, 1004–1013. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.693397

Rao, N., and Yuen, M. (2007). “Listening to children: voices of newly arrived immigrants from the Chinese mainland to Hong Kong,” in Global Migration and Education: Schools, Children and Families eds L. D. Adams and A. Kirova (London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 139–150.

Rix, J., Hall, K., Nind, M., Sheehy, K., and Wearmouths, J. (2009). What pedagogical approaches can effectively include children with special educational needs in mainstream classrooms? A systematic literature review. Support Learn. 24, 86–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9604.2009.01404.x

Rouse, M. (2006). Enhancing effective inclusive practice: knowing, doing and believing. Kairaranga 7, 8–13.

Rouse, M. (2008). Developing inclusive practice: a role for teachers and teacher education? Educ. North 16, 1–20.

Seale, J., Nind, M., and Parson, S. (2014). Inclusive research in education: contributions to method and debate. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 37, 347–356. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2014.935272

Sharma, U., Forlin, C., and Loreman, T. (2008). Impact of training on pre-service teachers' attitudes and concerns about inclusive education and sentiments about persons with disabilities. Disab. Soc. 23, 773–785. doi: 10.1080/09687590802469271

Subcommittee on Integrated Education (2014). Report Vol. 14. Available online at: http://www.legco.gov.hk/yr13-14/english/panels/ed/ed_ie/reports/ed_iecb4-1087-1-e.pdf

Tsui, A. B. M. (2003). Understanding Expertise in Teaching: Case Studies of Second Language Teachers. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Available online at: http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

United Nations (2015a). Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform Our World. Available online at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (Accessed December 31, 2017).

United Nations (2015b). We Can End Poverty: Millennium Development Goals and Beyond 2015. Available online at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/ (Accessed December 31, 2017).

Watkins, D. A., and Biggs, J. B. (2001). “The paradox of Chinese learner and beyond,” in Teaching the Chinese Learner: Psychological and Pedagogical Perspectives, eds D. A. Watkins and J. B. Biggs (Hong Kong: CERC), 3–23.

Keywords: inclusive education, inclusive pedagogy, inclusive teacher education, Hong Kong, policy and practice, Confucian heritage cultures

Citation: Li E (2018) Glocalizing Inclusive Quality Education in Hong Kong: From Pedagogical Challenges to Research Opportunities. Front. Educ. 3:47. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00047

Received: 16 March 2018; Accepted: 12 June 2018;

Published: 13 July 2018.

Edited by:

Gary James Harfitt, University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Tracy X. P. Zou, University of Hong Kong, Hong KongYu Hua Bu, East China Normal University, China

Copyright © 2018 Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eddy Li, ZWRkeWxpQGNhbnRhYi5uZXQ=

Eddy Li

Eddy Li