- School of Education, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

In the global context of deepening social and political divisions and at a time of growing forced displacement of people due to conflict, there is an ever increasing need for educators and school leaders to understand issues relating to equality and diversity with respect to themselves and the students with whom they work. In particular, the intersecting characteristics that make up individual and collective identities simultaneously afford opportunities and inflict oppressions depending on circumstances and context. This paper focuses on a theorization of intersectionality as simultaneity through an analysis of linguistic exchanges as they reveal fluctuations of empowerment and disempowerment in the context of culturally and linguistically responsive school leadership. It draws on research findings from the English case as part of an international comparative project focused on Black women principals' experiences of leading schools in England, South Africa and the United States of America. It reports an account of a British Pakistani Muslim woman's experience of school leadership as she negotiated a discussion of institutional racism in a school serving a multi-ethnic population of students. Using Bourdieu's linguistic concepts, I argue that a fine grained analysis of a series of reported linguistic exchanges with multiple stakeholders reveals how various members of the school community accepted or resisted her authority to use official language. There is no guarantee that linguistic habitus will convert into linguistic capital. Moreover, I argue that educators and school leaders need to understand intersectionality as simultaneity so they can navigate identity, institutional and social practices in relation to school leadership and the education of minoritized students.

Introduction

Mass migration has exposed deep divisions, as families risk their lives seeking refuge from conflict. Some find welcomes in new lands, new cities, new schools; others find racism played out as hostility, prejudice, discrimination and hate crime. At a time when the fields of politics and education have legitimized a racist, misogynist, and Islamophobic discourse, researchers need to focus on intersecting characteristics that make up individual and collective identities among school leader, teacher, and student populations. This paper challenges simplistic assumptions about the alignment or misalignment between these identities.

Some research draws explicitly on Intersectionality Theory. Even so, the fluctuations in powerfulness and disempowerment in women of Black and Global heritages doing school leadership remain undertheorized. Interview findings with eight women headteacher/principals revealed oppressions and opportunities relating to their “raced” and “gendered” identities. Here, findings from the account of a British Pakistani Muslim woman headteacher (Saeeda) demonstrate the simultaneously powerful and powerless aspects of her professional identity. Her identity was affected by a multi-faceted identity practice that interconnected with social and institutional practice. The analysis of linguistic exchanges, as discursive struggles with multiple stakeholders, revealed the nature of oppressions and opportunities associated with intersectionality. Saeeda's account of identity, institutional and social practice reveals her lived reality of doing school leadership.

This paper demonstrates the explanatory power of a fine-grained analysis of an individual's linguistic habitus, its relationship with dominant identity, institutional and social discourses and the resulting exposé of a woman school leader's simultaneous empowerment and disempowerment. Further, I argue that an understanding of language, discourse and power as they relate to intersecting identities is vital for researchers, policy-makers, school leaders and educators doing intersectionality work in a pluralist society. Whilst Bourdieu's social theory has been used to theorize educational leadership (Thomson, 2017), researchers have not used his linguistic concepts as thinking tools in the analysis of the relationship between leader and student identities.

In the following section, I review the small body of empirical research using Intersectionality Theory to investigate links between leader and student identities. Next, I provide an outline of Bourdieu's (1992) linguistic concepts. In the following sections, I describe the research project and present findings relating to Saeeda's account of identity, social and institutional practice. Her accounts of linguistic exchanges with members of the school population were analyzed to reveal the powerful/lessness felt during her headship. The discussion section focuses on the interrelationship between intersectionality, linguistic habitus and official language to show the influence of language use in leadership. I conclude there is no guarantee that linguistic habitus and competence in using the official language converts into linguistic capital.

Intersectionality as Simultaneity in School Leadership

It is not new to think about intersectionality as simultaneity (Holvino, 2010). The ambivalence of oppression and opportunity is a long-standing theme in the experience of women of color, of Black and Global Majority (BGM), Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) and Indigenous heritages (hereafter women of BGM heritages following Campbell-Stephens, 2009) (Collins, 2000; Hooks, 2000; Horsford, 2012). The intersection of race, sex, and class in women's lives is a well-established focus of research (Davis, 1981; Amos and Parmar, 1984; Mohanty, 1988; Mirza, 1997; Smith, 1999). Indeed, Intersectionality Theory provided an alternative to a white, middle class women's narrative of gender and a Black men's narrative of race (Crenshaw, 1991). It is a central concept of Critical Race Theory (CRT), which has exposed endemic racism in the English school system and wider society (Gillborn, 2005; Chakrabarty et al., 2012; Rollock et al., 2015). In the 15 years since López (2003) called for it, little has found its way into the field of educational leadership. Researchers, school leaders, educators and policy-makers still need to debate how social, institutional and identity practices interact “within a theory of power about how the individual is able to or enabled to exercise agency” (Gunter, 2006, p. 266).

Few empirical studies published in the English-speaking educational leadership canon1 draw explicitly on Intersectionality Theory to report connections between the identities of women principals of BGM heritages and the students they served. Nor are there studies using Intersectionality Theory in non-settled countries. Their exclusion constitutes “institutional silencing” (Gitlin, 1994, p. 4 cited in Bloom and Erlandson, 2003, p. 345) (also Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010). More recently, a small but important literature is developing a discourse about the links between women and the communities they serve in the United States (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010; Arnold and Brooks, 2013; Santamaría, 2014; DeMatthews, 2016), South Africa (Lumby and Heystek, 2012; Moorosi, 2014; Lumby, 2015), Canada (Armstrong and Mitchell, 2017), Australia, Canada, New Zealand (Fitzgerald, 2006), and England (Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010; Lumby and Heystek, 2012; Curtis, 2017). Each reveals the ubiquity of racial and gendered oppressions women principals experienced with respect to individual identity, institutional and wider social practice (Holvino, 2010).

Everyday oppressions related to specific geopolitical and socio-historical contexts such as the racism associated with colonialism and postcolonial diaspora in England, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada; the legacies of slavery, segregation and de/re-segregation in the United States; and the legacy of Apartheid in South Africa. Institutionally, women of BGM heritages were subject to oppressions regardless of their status as school leaders. They were underrepresented despite demographic shifts in the school population (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Fitzgerald, 2006; Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010; Lumby and Heystek, 2012; Santamaría, 2014; Fuller, 2017a; Johnson, 2017). They struggled against the dominant discourse of school leadership as white and male (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003) with appointment panels preferring the latter candidates (Fitzgerald, 2006; Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010; Lumby and Heystek, 2012; Lumby, 2015).

Lumby and Heystek (2012, p. 17) found a “vision of coherence” masked the exclusion of ethnic minority colleagues through non-acceptance, privileged al legiances, and adherence to different values. The internalization of exclusionary practices, “both from the outside community and your own” led to low career expectations and aspirations (Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010, p. 47). Internal barriers to career advancement were created and sustained by social and institutional practice. Their appointment to under-resourced schools (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Arnold and Brooks, 2013) attended by students from materially impoverished homes (Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010; Arnold and Brooks, 2013; DeMatthews, 2016) meant Black women principals entered a cycle of stereotyped identities as Messiah, sacrificial lamb, or scapegoat when their advocacy for students became problematic (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Arnold and Brooks, 2013). This was a harsh environment in which to work (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010). Principals were expected to follow education policy against the educational interests of minoritized children (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010). At the same time they were expected to use their cultural resources to take responsibility for children's needs (Fitzgerald, 2006; Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010). For some, bridge leadership (Horsford, 2012) increased the emotional labor of working and walking between worlds (Fitzgerald, 2006; Curtis, 2017) or the potential for “being ghettoized” (Wilson et al., 2006, p. 250).

Some studies identified opportunities. For example, bridge leadership enabled transformative community education. Its adherence to democratic practice required non-hierarchical leadership approaches to “meet the needs of people where the[y] are and … to connect with who they are” (original emphases) (Horsford, 2012, p. 18) (Armstrong and Mitchell, 2017; Curtis, 2017; Johnson, 2017). Indeed, some school leaders associated working with minoritized students with a fast track to promotion (Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010). Santamaría (2014) has argued some leaders of color practice applied critical leadership as a consequence of experiencing simultaneous oppressions regarding race, gender and class. However, there were no guarantees that educators and leaders from BGM heritages exercised culturally responsive pedagogy and leadership (Fuller, 2013; DeMatthews, 2016). Nor could it be assumed white educators and leaders lacked critical consciousness (Fuller, 2013, 2015; Santamaría, 2014).

Language, Discourse, and School Leadership

The relationship between learner identities, language and school leadership features in research about the practice knowledge needed to work with children with English as an Additional Language (Mistry and Sood, 2010, 2011; Lumby and Heystek, 2012; Mansfield, 2014). Linguistic understanding goes further than acknowledging what language a school leader speaks, though language might be recognized as a key intersecting aspect of leader and learner identities and a factor in the facilitation of learning (Santamaría, 2014). Beyond recognizing the challenges and opportunities associated with linguistic diversity in learner and leader populations, Lumby and Heystek (2012, p. 10) saw language as a key component and medium of identity construction “conceived as a performance captured during its ongoing and fluid construction and perceived through the prism of language.”

Shah (2006) acknowledged the multiplicity of languages spoken by Muslims worldwide, noting British Muslims coped with four intersecting identities relating to: country of abode, country of origin, racialized, and religious identities. These intersecting identity discourses were accompanied by conflicting dominant discourses of students' achievement, leadership, and management against the backdrop of discourses of risk, in the wake of the 7/7 London bombings, and political Islam. Muslim students struggled against conflicting discourses inside and outside school. Citing Haw (1998), Shah noted Muslim girls' educational aspirations outstripped those of their teachers. She called leaders to focus on specific issues, namely: “Personal/group identity; Media projections; Stereotyping/assumptions; Job routes; Role models; Peer pressure; and Community perceptions/stances” (Shah, 2006, p. 227).

Johnson's (2017) historical and contemporary account of Muslim women headteacher/principals as pioneers and novices in the United Kingdom is a welcome contribution but there remains little research that focuses on the fluctuations of powerfulness and powerlessness in the experience of Muslim women headteacher/principals leading schools populated by students from multi-ethnic heritages in England.

Identity, Language, Discourse, and Power

Given the social construction of identity, we can attribute meaning to each of the differences comprising intersectionality in specific contexts. Individuals construct subjectivity; but understandings of gender and societal structures also affect that construction. It is dialogic: discursive. In a performative understanding, there is a language, through which we “do” race, gender, sexuality, identity (Butler, 1990). Differences are “interdependent and interactive” (Holvino, 2012, p. 169) with social processes such as class or race. Individuals “translate and negotiate” between multiple aspects of their identities as they move across geographical and social spaces, be they countries, institutions or both (Arifeen and Gatrell, 2013, p. 154). Here, four of Bourdieu's (1992) linguistic concepts become useful: official language, linguistic habitus, linguistic capital and linguistic exchanges in theorizing the relationship between identity, language, discourse and power.

Official language is formalized, legitimized, and hegemonic. Use of it enhances an individual's position in the field of education, educational leadership, or an individual school. There is an official language and set of behaviors associated with being a headteacher requiring them to speak in particular ways to different people such as students and parents, colleagues and governors. Use of official language forms part of the headteacher's linguistic habitus. The acquisition of cultural capital, including linguistic knowledge, an understanding of how language works or of different languages, also informs linguistic habitus. The use of different registers (more or less formal) depending on context and circumstances, other languages than the dominant language of instruction, for example, and the languages associated with doing aspects of identity such as race, gender, sexuality, and social class add to the formation of linguistic habitus. How a person does race, gender, sexuality, and social class might enhance or detract from their linguistic capital. Linguistic capital is an embodied cultural capital acquired as first language development and enhanced as a child moves through education and other experiences into adulthood. It acquires symbolic value depending on the response of the listener or interlocutor. It might be converted to economic capital if it can be reproduced in appropriate ways “for a particular market” (Thompson, 1992, p. 18) or audience. Social structures and power relations are expressed and reproduced through linguistic exchanges, or dialogic encounters between individuals.

An individual's linguistic competence in matching language to situation or audience will be constructed as compliance with, or transgression of dominant or normative languages, behaviors, and discourses associated with each facet of their identity. Thus, the fine grained analysis of accounts of linguistic exchanges between a headteacher and members of the wider school population might reveal fluctuations in power relations. This will depend on her interlocutor's construction of the match between use of language and the intersecting facets of her identity as assets or deficits. It might be possible to comply with the dominant discourse of what it means to be a British Pakistani mother by using the “right” language. Simultaneously, the same woman might transgress the dominant discourse of what it means to be headteacher of a school in England by using the “wrong” language.

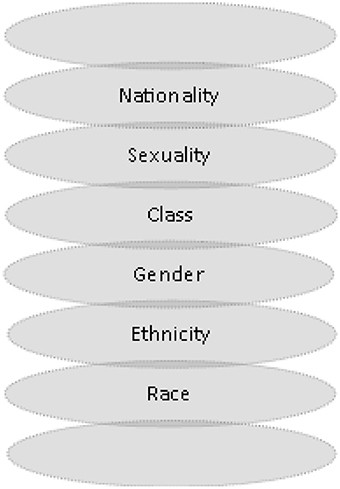

An individual's linguistic habitus may or may not translate into linguistic capital; their intersectional identity may in one situation lead to oppression and in another to opportunity. This makes visible the “simultaneous experience of oppression and privilege” (Dill et al., 2007, p. 629 cited in Holvino, 2012, p. 170) and the resulting nuanced fluctuations of powerlessness and powerfulness. This conceptualization of intersectionality goes beyond multiple and various categorical complexities (McCall, 2005) associated with the investigation of superdiversity to advocate for social justice (Vertovec, 2007). A hologram demonstrates the complexity, multiplicity, fluidity and ever changing quality of identity practice that defies a researcher's attempt to capture and fix an individual's identity (Figure 1; Holvino, 2012).

Figure 1. Theories of difference: making a difference with simultaneity (Holvino, 2005) (http://slideplayer.com/slide/4446160/). Permission received for reprint from Evangelina Holvino.

In the following sections I describe the research project that produced Saeeda's account of school leadership including an account of my positionality as researcher.

The Research

This paper reports findings from Saeeda's (a pseudonym) account of achieving and doing headship/principalship as a British Pakistani Muslim woman leading a primary school in England. It belongs to the English case in an ongoing comparative research project focused on the intersections of race and gender in school leadership in South Africa, England, and the United States (Moorosi et al., 2017). The English case consisted of eight women headteacher/principals of BGM heritages leading primary and secondary schools in London, the south, the Midlands and north of England. Each account is also an individual case or unit of study.

Positionality

I adopt an interpretivist approach in recognizing my part in the investigation. The exploration is from participants' perspectives but my construction is the one presented (Morrison, 2012). Specifically, this research is an example of women being studied on their own terms that challenges and transforms educational leadership theory (Shakeshaft, 1987). A critical feminist perspective acknowledges the centrality of values to research activity; that “describing and changing the world are elided” (Morrison, 2012, p. 31); I do not have a neutral stance.

Aiming to “tread new and different theoretical waters” (Dantley et al., 2009, p. 125), I dive into these new waters to foreground race, ethnicity and religion in my theorization of women's school leadership. I aim to amplify voices of women marginalized by underrepresentation in school leadership (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Fitzgerald, 2006; Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010; Lumby and Heystek, 2012; Santamaría, 2014; Fuller, 2017a).

Scholars addressing oppression have used “their prime area of understanding as a philosophical and perspectival home” (Dantley et al., 2009, p. 125). As a white gender and feminist scholar, I have not ignored “race” (Fuller, 2013, 2015, 2017b). I remain grateful that the women shared their stories with me. I believe I established rapport but do not take that for granted. I engaged in self-disclosure to answer questions implying the desire to know “Who are you?” and “Why should I talk to you?” (Dunbar et al., 2002). I provided interview questions in advance as a way of mitigating the social intrusion of carrying out an intercultural interview (Shah, 2004).

I do not automatically share understandings with women of BGM heritages (Rollock, 2013). In a radio interview Baroness Doreen Lawrence described taking measures to avoid suspicion of shoplifting,

“When you walk into a store you do get a second glance. You walk in a certain way with your bag closed” (Baroness Lawrence cited in Watts and Davenport, 2014, no page).

Neither the white male radio presenter, nor I immediately understood. I would make sure my bag was closed because someone might steal from me. Baroness Lawrence's point spoke to the police practice of “stop and search” and the extent of racism in the wider community. These are everyday microaggressions of racism (Delgado and Stefanic, 2001). Moments of hesitation and potential misunderstanding revealed how far a white researcher must go before joining a race dialogue in which they are made unsafe (Leonardo and Porter, 2010) in which they unlearn privilege (Rusch and Horsford, 2009). I adopt a reflexive stance “which demands that those involved in studying intersectionalities problematize their own social location at the intersection about which they seek to produce knowledge” (Holvino, 2010, p. 259). I have recounted “self-critical disturbances” to demonstrate experiences with racism (Fuller, 2017b, p. 105) and sense of the “Other Within” (Blackmore, 2010).

Site and Participants

In England, women headteacher/principals, of BGM heritages, are underrepresented. In nursery and primary education, they comprise 2.3% of headteachers and 5.8% of classroom teachers (Department for Education, 2016). In secondary education, they make up 1.8% of headteachers compared with 9.9% BGM women teachers (Department for Education, 2016). In the population as a whole 14 per cent of the population did not self-identify as White (Office of National Statistics, 2012).

Participants responded to an invitation as women of BGM heritages. Five led secondary schools and three led primary schools. The women self-identified variously as Black British/Black Caribbean, Indian, Bangladeshi, British Pakistani, or mixed heritages including with white British in one case. Black British Feminism has been conceptualized as an inclusive “self-defining presence as people of the postcolonial diaspora” (Mirza, 1997, p. 3). Almost all were born in the United Kingdom. The women's ages ranged between late thirties to early fifties. Almost all had children whose ages ranged from pre-school to adulthood. Most were married; five had married white British men. Two women identified as Muslims. Further detail about Saeeda is provided in the account of her identity practice below.

Data Collection—The Interview

Face to face semi structured interviews took place in participants' schools. These were purposeful conversations lasting between 50 and 80 min. They were recorded and transcribed. I asked questions about (1) the achievement of school leadership; (2) what constitutes successful school leadership? and (3) what sustains them in their work?. To explore connections between headteacher/principal and student identities I asked about their work with staff and students: “How do you encourage young BGM/BME girls/women to achieve in their education? In their professional lives? In their leadership?” Participants gave full informed consent to the research on the understanding I would not reveal names, schools, or their locations. I followed the ethical approval protocols of my institution. Most participants made minor changes to the transcripts; one deleted text relating to personal and family detail and material she thought might identify her.

Preliminary findings from three women headteacher/school principals working in South Africa, England and the US have reported similarities in those women's early influences, and on their resistance, agency and strength (Moorosi et al., 2017).

Data Analysis

During this fine-grained analysis of Saeeda's transcript, I sought feedback from all participants with respect to linguistic habitus. Saeeda's account resonated strongly with those of other interviewees: in total, seven valued linguistic diversity as an asset. All recounted personal or parental histories of postcolonial diaspora. Trustworthiness in the reporting and interpretation of findings has been demonstrated by the back and forthness of member checking described in the effort to establish credibility, dependability, the possibility of transferability, and confirmability. However, these women do not constitute a homogenous group. I do not claim Saeeda's case is typical of this group or of British Pakistani Muslim women headteacher/principals. Instead, I have drawn on it to illustrate the value of using Bourdieu's linguistic concepts in looking closely at a headteacher/principal's account of linguistic exchanges to reveal how linguistic habitus does or does not convert into linguistic capital. Saeeda's transcript was coded to locate, analyse and interpret accounts of linguistic exchanges to reveal oppressions and opportunities at the point of intersectionality. I consulted Saeeda by telephone to discuss my interpretation of her Muslim identity and the role Islam might take in a feminist theorization. She was the only British Pakistani Muslim woman in the sample; the only Muslim woman leading a multi-ethnic school.

The limitations are clear. Findings are not intended to be generalizable. However their validity lies in my belief that Saeeda's account was genuine; her demonstration of emotion during the interview reinforced the sense of residual pain having confronted institutional racism. Her interlocutors might give different accounts. Nevertheless, the findings demonstrate how Saeeda's identity, social and institutional practice influenced her school leadership; “the ways in which race, gender and class produce and reproduce particular identities that define how individuals come to see themselves and how others see them in organizations” (Holvino, 2010, p. 262). Saeeda's words are in italics.

Saeeda's Identity Practice

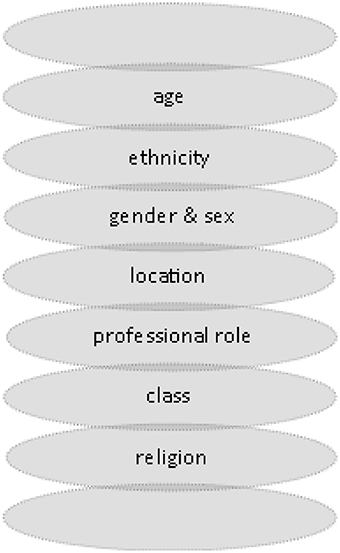

Saeeda was born in England. Her parents had moved from Pakistan: her father to study and her mother after they married. Her father had worked as a bus driver, then shopkeeper. Saeeda's subjective identity was described in terms of the intersecting aspects of age, ethnicity, gender, sex, location, professional role, class, and religion (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Saeeda's identity model of simultaneity (adapted from Holvino, 2005). Permission received for reprint and adaptions from Evangelina Holvino.

Saeeda was in her mid-forties. She identified as British Pakistani. She was multilingual, speaking English, Punjabi, and Urdu (her husband's language). She had a nuanced understanding of languages and language construction; she recognized the linguistic habitus of children with English as an Additional Language (EAL). Saeeda used her family roles of mother, daughter, wife to identify in terms of gender and sex. Her parents provided childcare. She had taken her baby into school once a week, whilst on maternity leave, to work on the school development plan. Her husband (a skilled tradesman) supported her as a working mother by agreeing to move near her family. He offered her the opportunity to give up work when it was difficult despite Saeeda being the higher earner, “as an Asian woman, it's my husband's responsibility to look after me […] he will say to me quite genuinely, ‘Well why don't you just give up? Why don't you just not do that?”’ Having lived in four locations across the UK, Saeeda was living “a stone's throw” from school, where her family had settled and she was educated. She was fully aware of children's transnational family identities. A career in industry preceded that of teacher, local authority consultant for students with EAL, and headteacher in two schools. She was from an educationally aspirational family having attended comprehensive school, college and university. She had a degree, a teaching qualification and a continued interest in reading about leadership. Saeeda deliberately understated her Muslim identity in relation to school leadership because the school population was multi-faith and it would be inappropriate to do otherwise.

The social differences described above are relational. In her first headship Saeeda's ethnic identity differed from her colleagues; she had family roles as mother, daughter, and wife.

Social Practice

Saeeda was acutely aware of the interconnectedness of identity, social and institutional practice. The way cultures were accepted, perceived and spoken about when she was growing up in 1970s England was different to contemporary attitudes. The dominance of whiteness and invisibility of people from BGM heritages in the media was linked with childhood recognition “All the teachers here, all the people in power, are all white.” That was internalized as “to be successful you have to be white.” It simultaneously provided the motivation to become a teacher and role-model who “wanted to show people that that's not the case” and to use her cultural experience in school “You're tackling stereotypes all the time just by being around.”

Below I explore meanings attributed to differences as they were understood by Saeeda and her interlocutors with respect to institutional practice. Saeeda reported linguistic exchanges that reveal discursive struggles and the negotiation of power relations. She recounted multiple oppressions of institutional practice in the education system regarding: career “choices” and job applications, and in her work as headteacher in her first school. Some were simultaneously constructed as opportunities; as was her second headship.

Institutional Practice

Career Choices and Job Applications

Saeeda speculated about her appointment as “Section 11” teacher funded by the Local Government Act (1966) “to help meet the special needs of a significant number of people of commonwealth origin with language or customs which differ from the rest of the community” (National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum, 2015, no page).

“It kind of pigeon-holed me there on in […], and later on in life I do question why I didn't get the other job [classroom teacher] [laughs].”

She problematized the balance between structure and agency in her career progression,

“the trajectory for me has been written in a way, unless I was, in those early years, I was willing to fight it. In the early years I wasn't. I just wanted a job.”

She worked as Ethnic Minority Achievement coordinator and local authority consultant for students with EAL. This career history combined with assumptions made about her identity “how you look and what your name is” meant she was “pushed into” some career “choices,”

“when I go to a school where the majority of children are Asian, I'm immediately thought of ‘well there's an advantage here’, and there might not be because I might not have a second language. I mean I have but I might not speak the language the children speak, and although my name suggests I'm Muslim, I might be practising or I might not be practising.”

Assumptions about ethnicity, language and religion led to overt discrimination at a predominantly white school. Saeeda was told,

“you would be better suited using your skills in a particular type of school. You know what we mean don't you?”

Saeeda's appointment to a consultancy post was simultaneously constructed as an opportunity because it, “suited me fine at that time because I had a little boy […] and I thought great because it's more flexible.”

In the next section I explore locations of conflict in a series of linguistic exchanges Saeeda recounted from her first headship.

Naming Institutional Racism

Saeeda focused on raising academic attainment in a school where the population was 60% Indian and 40% Pakistani heritage children many of whom were EAL speakers. She recognized low expectations as institutional racism.

Linguistic exchanges were reported between:

• Headteacher and parents,

• Headteacher and children,

• Headteacher and staff,

• Headteacher and school governors, and

• Headteacher and the local authority.

Stretches of Saeeda's speech reveal the nature of the encounters.

Headteacher and Parents

As parents negotiated aspects of their own and their children's diasporic identities, a discursive struggle occurred. Some did not speak the same first language. Like Saeeda, many mothers spoke Urdu as an additional language; their linguistic habitus coincided as a shared multilingual resource through which to communicate. It was given value and converted symbolically into linguistic capital.

Headteacher and Children

Similarly there was a discursive struggle with children whose linguistic habitus was still forming. Children were in the early stages of language and speech development (aged 4–7 years old),

“they will speak Pahari. They'll speak their particular dialect. […] I know from their reaction that they don't understand me, but if you're not tuned into how children should react, then you don't know whether they've understood you because children usually just nod.”

Saeeda's linguistic habitus converted symbolically into linguistic capital that enhanced her sensitivity to children's needs. She valued children's broadening linguistic habitus,

“Some of them are bilingual. Some of them have their first language really well developed and it's just a case of us developing their conceptual knowledge like you would with any child, with a monolingual child.”

Her linguistic habitus benefitted children's developing linguistic habitus that would convert by way of educational outcomes into linguistic capital.

Headteacher and Staff

The previous headteacher, senior leaders (white women) and staff adopted a deficit discourse to excuse lower academic attainment. Opposing discourses regarding bi/multilingualism became a site of conflict. Saeeda communicated with children to

“…see that at the very least they were average children. So they should be achieving in line with what the national average is.”

Teachers' lack of aspiration aligned with lack of community knowledge, “the teachers, because they're mostly white and middle-class, they come from other areas.” They were “well meaning” but lacked knowledge, understanding and expectation. Their linguistic habitus comprised limited resources; they undervalued the children's and Saeeda's linguistic habitus.

Saeeda named decades of low expectations as institutional racism. She said to senior colleagues,

“‘When I first came, I didn't realise. I didn't understand what was going on other than there were low expectations. But I would say that this is what is termed institutionalised racism’. I actually used that term.”

Saeeda cited the McPherson Report (McPherson, 1999) (inquiry into the murder of Stephen Lawrence, son of Baroness Doreen Lawrence referred to above) definition,

“they clearly didn't have a clue what I was talking about because they hooked onto the racism word. I had to print out the definition for them and say to them, ‘I'm not saying you are racist. I'm not saying that. Let me make that clear. What I'm saying to you is that because […] historically whatever has been put in place here at the school, because of that, our children haven't attained to their potential’.”

Despite initial acceptance, apology and a conciliatory tone, these white women senior leaders could not “get past” the “barrier” that naming institutional racism created,

“I've started to use the word stereotyping because I feel then people listen to the rest of the conversation. If you say institutionalised racism, people sit up immediately and there's a barrier there and in my experience with the many people that I've spoken to, become very defensive and I can't get past what I'm actually trying to- I can't get through to them what I'm actually saying.”

“… the message didn't get across- and it didn't get across because I think I used that term. So as I say, subsequently I use the word stereotyping which seems to be more palatable.”

Each senior leader expressed concern for individual and institutional reputations. One deflected the issue back to Saeeda,

“We do think it's an issue but it's an issue for you' [her emphasis]. [Laughs]. So they didn't recognise. I found that really upsetting [audibly emotional].”

Saeeda's recollection remained painful. The white women senior leaders took control of the discourse.

Headteacher and School Governors

Governors, mainly Asian men from the community, challenged her. They were frustrated by her counter discourse, but this was a gendered challenge “culturally again you're stereotyped.” She was

“… telling them something different and I don't know if they were frustrated with themselves because they'd been long-established governors or if they didn't believe what I was saying, but over time that was proven to them, the things that I was saying about where our results should be etc.”

Saeeda convinced governors expectations should be higher and parted from the school on good terms with them. The British Indian chair of governors proved an ally having previously wondered whether institutional racism accounted for poor school performance.

Headteacher and the Local Authority

Saeeda and the local authority clashed over her naming of institutional racism,

“they start to think about legal action. […] they get very defensive. I've said to them, ‘I would like something positive to come out of it. I'm not wanting to sue anybody or anything like that. I just want something positive to come out of it”’

Saeeda cited the UK Equality Act (2010) and the Public Sector Equality Duty (Equality Human Rights Commission, 2012),

“I did bring that up because I think they failed in their duty towards me most definitely. Going forward, I don't feel that they're educating sufficiently their teaching staff within schools […] now [training's] voluntary and it's not something that the [Local Authority] push particularly, but it's a duty on schools to do it.”

Saeeda's resistance of the dominant white leadership discourse, reference to equalities and employment legislation and determination to influence new principals might be seen as a partial success. The local authority planned to incorporate equality and diversity training, led by Saeeda, into headteacher induction.

Below, I discuss the relationship between linguistic habitus, official language and linguistic capital in relation to the interplay of shifting facets of identity as they simultaneously interacted with social and institutional practice to reveal fluctuations of powerfulness and powerlessness in school leadership.

Intersectionality, Linguistic Habitus, and Official Language

As a British Pakistani Muslim woman Saeeda transgressed the dominant discourse of white, male school leadership in England. Her very presence in headship tackled stereotypes (Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010). The interrelationship between her identity, institutional and social practices demonstrates the simultaneity of oppression and opportunity associated with intersecting facets of her identity present in her experiences of the education system—as child, teacher, and headteacher. There were blatant attempts at ghettoization during a teaching appointment process (Wilson et al., 2006). Indeed, assumptions about Saeeda's ethnicity, language, and religion are an example of overt discrimination at a predominantly white school (Lumby and Heystek, 2012). Nevertheless, she constructed securing an EAL consultancy as advantageous for a new mother managing family responsibilities and career. In retrospect, Saeeda saw EMA and EAL focused work as constraints rather than a “fast track” to headship (Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010, p. 41). The complexity and fluidity of intersectionality as simultaneously oppressive and advantageous, depending on context and circumstances, is demonstrated clearly in this account of a career path. In addition to the opportunities inherent in her identity practice, Saeeda reconstructed experiences of oppression as opportunities to enact agency (Moorosi et al., 2017). She self-defined and self-determined “because speaking for oneself and crafting one's own agenda is essential to empowerment” (Collins, 2000, p. 36).

The co-construction of identity through language reinforces the opportunity and oppression associated with it. As parents learned to negotiate aspects of their own and their children's diasporic identities (Arifeen and Gatrell, 2013), Saeeda's identity practice afforded bridge leadership (Horsford, 2012). Most would expect a positive response to a focus on raising academic attainment (Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010; Arnold and Brooks, 2013; Santamaría, 2014; DeMatthews, 2016); instead, male governors questioned her authority. Naming oppression is an important pro-active and defensive strategy used by Black women principals (Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010), but naming institutional racism revealed the gulf between Saeeda's professional knowledge, understanding, expectation and values and that of her colleagues (Mistry and Sood, 2011). There was danger of being made a scapegoat and this school became an increasingly harsh environment (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010).

This analysis of linguistic exchanges and an understanding of the relationship between linguistic habitus, official language, and linguistic capital enables theorization of the fluctuations of power relations. Saeeda's linguistic habitus was informed by acquisition of languages, linguistic knowledge and identity practice, shown here as a model of simultaneity showing the intersections of professional role with age, ethnicity, gender and sex, location, class, and religion (Figure 2). There is an official language, a way associated with being a British Pakistani, married, Muslim woman with children in her forties living in England who has negotiated powerful conflicting discourses (Shah, 2006). Each aspect of Saeeda's identity influenced her propensity and capacity to speak with authority in the context of her professional work. The linguistic exchanges revealed the power relations between speakers as Saeeda's authority depended on their recognition and/or acceptance of her authority to speak using the official language.

The official language operates on multiple levels. First, English is the official language of the UK and dominant language of instruction in schools (Welsh is an official language and a language of instruction in Wales). Second, English is a globally dominant language; 1.5 billion people are learning English worldwide and English learning is seen to empower (Bentley, 2014). Third, equalities and employment legislation builds on historical race relations, sex discrimination legislation, and the findings of inquiries such as The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry (McPherson, 1999). Fourth, education policy enacted in law can be seen as the official language of doing education and school leadership. A headteacher's successful compliance with education policy is commonly measured by children's academic outcomes and school inspections.

Saeeda speaks English; it has been the language of instruction throughout her education and career. Saeeda recognized the power of using official language in school leadership; she consulted the McPherson Report (McPherson, 1999) to name institutional racism correctly as a collective, institutional and possibly unintentional practice. She cited The Equality Act (2010) and Public Sector Equality Duty (Equality Human Rights Commission, 2012) to local authority personnel. Saeeda enacted the official language of education policy to secure children's success in the English education system. There is much evidence that Saeeda had command of the official language associated with school leadership. This competence was part of her linguistic habitus that might be expected to result in her empowerment and the acquisition of linguistic capital.

In two cases, Saeeda's authority was accepted by virtue of her multilingualism and linguistic understanding, combined with her professional role. Her linguistic habitus, developed at home (Punjabi and Urdu) and in school (English) was directly connected to her ethnic identity. It was valuable in her work and converted into linguistic capital through early appointments in her career. It served to empower her among students and parents who accepted her authority and ability to speak.

However, Saeeda's authority to speak was challenged by three groups. Senior leaders resented her use of official language in describing institutional practice as institutional racism—it was reconstructed and deflected as comprising a personal issue for Saeeda based on her minoritized identity. Her colleagues' linguistic resources might be limited but they spoke the official language of white privilege (Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010; Lumby and Heystek, 2012; Santamaría, 2014) to reify the continuing contemporary power of colonial times (Mirza, 2009). In their hostility, they reasserted the dominant discourse of education and leadership as white to undermine Saeeda's authority (Gillborn, 2005; Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010). They refused to recognize the institutional racism that led to under-attainment among children who had traveled to new lands to be faced with learning new languages of reconfigured identities (Arifeen and Gatrell, 2013). Any “vision of coherence” (Lumby and Heystek, 2012, p. 17) was unmasked to reveal Saeeda's exclusion and an expectation to educate against the interests of children with EAL (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010). Earlier in her career she was expected to use her cultural resources to take responsibility for their needs (Fitzgerald, 2006; Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010). This bridge leadership (Horsford, 2012) increased the emotional labor of biculturalism (Fitzgerald, 2006; Curtis, 2017).

Using neutralized language after the event, i.e., “stereotyping” as a euphemism for institutional racism, failed to undo the apparent damage. The linguistic dexterity this code switching demonstrated was undermined by the power of white privilege. Finally, a defensive response from local authority personnel to Saeeda's use of official language, reinforced hierarchical power relations where other interests took precedence over Saeeda's and those of children from minoritized populations. Each of these linguistic exchanges demonstrated fluctuations in Saeeda's sense of empowerment and disempowerment. The precarity of her position depended on the constructions of, and interactions between identity and institutional practice. Deep rooted structural inequalities were too secure for a headteacher to address “in solitude” (DeMatthews, 2016, p. 15); nevertheless, Saeeda was, like many women principals, concerned with educating and leading for social justice in the community and wider society (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Fitzgerald, 2006; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010; Arnold and Brooks, 2013; Santamaría, 2014; Lumby, 2015; DeMatthews, 2016; Armstrong and Mitchell, 2017; Curtis, 2017; Johnson, 2017).

Social practice, and the dominant discourse or official language associated with it, pervades identity and institutional practice. There is no static macro level backdrop to micro level practices. Social practice legitimises discourses, particularly when political parties engage in discourse that “generates hostility, discrimination, prejudice or division; [is] abusive or denigrating; promot[es] stereotypes; or us[es] false, erroneous or misleading information” (Equality Human Rights Commission, 2017, p. 1). This research took place at the beginning of 2016. The socio-political and historical context is important because it took place following the forced displacement of approximately 6 million Syrians by the end of 2015; two thirds of whom had headed to countries throughout the Middle East and beyond (Yazgan et al., 2015). This was: (1) before the European Union referendum in the UK (23 June 2016), just before the date of the referendum was set but after the EU Referendum Act 2015; (2) before the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States (7 November 2016) but during an election campaign marked by “incendiary rhetoric” (England, 2017) of racism, misogyny and Islamophobia; and importantly, (3) after investigations into unfounded allegations of the radicalization of Muslim students in Birmingham schools in 2014 (Mogra, 2016). It does not matter whether or not Saeeda worked in a Birmingham school. Her first headship spanned the time when allegations about Muslim school leaders and educators featured daily in the national press (Cannizzaro and Gholami, 2018). The challenges to her authority to use official language described above, be it the English language, the language of equalities or employment legislation, or education policy, occurred in that public discourse context. Saeeda's caution not to overstate her Muslim identity should be read in that context as identity self-censorship. This social practice enters the organization as resistance to the headteacher/principals' authority from stakeholders including teachers (Bloom and Erlandson, 2003; Witherspoon and Taylor, 2010), senior colleagues (Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010) sometimes, though not on this occasion, parents (Coleman and Campbell-Stephens, 2010; DeMatthews, 2016) and the wider community (Fitzgerald, 2006).

Saeeda's linguistic habitus led simultaneously to the acquisition of linguistic capital and oppression. There are no guarantees that linguistic habitus and the competent use of official language will convert into linguistic capital, economic or symbolic.

Conclusion

In this paper I have demonstrated the importance of foregrounding race, ethnicity and religion in a critical feminist theorization of intersectionality as simultaneity in women's school leadership. The interdependence and interaction of identity, institutional and social practice (Holvino, 2010) can be seen in this fine-grained analysis of linguistic exchanges taking place in everyday school leadership practice between headteacher and students, parents, staff, governors and, in this case, the local authority. In other locations across the UK, Europe, and on other continents, it might take place between headteacher and executive headteacher, chief executive or multi-academy trustees; between school principals, superintendents and school boards. These exchanges exposed the nature and degree of fluctuation in the headteacher's empowerment and disempowerment in her everyday practice. The social construction of identity converted linguistic habitus done by one person, and recognized by another, into linguistic capital, symbolic or otherwise. By contrast, challenges to official language use, and specifically making an educational issue personal to the headteacher in her minoritized ethnic identity, reified colonial power in new times (Mirza, 2009) as institutional racism that impacted on students, teachers and/or school leaders. Bourdieu's concepts have proved useful thinking tools in the analysis of data and in this theorization. They can be applied to an equally nuanced analysis of the remaining data in the English case—each headteacher described similar exchanges with various members of the school community; and in the comparative analysis of data from the South African and US cases.

This theorization could be applied to men of BGM heritages as well as women. It can be used to help white leaders' and educators' unlearn their privilege (Rusch and Horsford, 2009) and to think about the education and leadership of minoritized students and staff. A theorization of intersectionality as simultaneity that focuses on language, discourse and power as they relate to intersecting identities is vital for researchers, policy-makers, school leaders and educators doing intersectionality work in pluralist societies all over the world. It is particularly necessary when racist, misogynist and Islamophobic discourses are increasingly legitimized. As children, young people and their families arrive and settle in new lands, for whatever reason, many are simultaneously reconfiguring new identities, learning new languages, building lives, having families and developing careers. Further research is needed that focuses on the fluctuation of empowerment and disempowerment as it occurs in their lived realities. Educators and school leaders at every level need to better understand the complexity and fluidity of intersectionality and its relationship with language, discourse and power. That way, they might be able to navigate identity, institutional and social practices as they and others experience them. Importantly, it is understanding the influence of these on the leadership of staff and on children's learning that might make a difference.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the University of Nottingham Code of Research Conduct and Research Ethics. The School of Education Ethics Committee approved the study. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the School of Education Ethics Committee.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer CB and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Footnotes

1. ^Educational Administration Quarterly (EAQ); Educational Management, Administration & Leadership (EMAL) (formerly Educational Management and Administration); International Journal of Educational Management (IJEM); International Journal of Leadership in Education (IJLE); Journal of Cases in Educational leadership (JCEL); Journal of Education Policy (JEP); Journal of Educational Administration (JEA); Journal of Educational Administration and History (JEAH); Journal of Research on Educational Leadership (JREL); Journal of Research on Leadership Education (JRLE); Leadership and Policy in School (LPS); Management in Education (MiE); School Leadership & Management (SLM).

References

Amos, V., and Parmar, P. (1984). Challenging imperial feminism. Fem. Rev. 17, 3–19. doi: 10.1057/fr.1984.18

Arifeen, S. R., and Gatrell, C. (2013). A blind spot in organization studies: gender with ethnicity, nationality and religion. Gend. Manage. Int. J. 28, 151–170. doi: 10.1108/GM-01-2013-0008

Armstrong, D., and Mitchell, C. (2017). Shifting identities: negotiating intersections of race and gender in Canadian administrative contexts. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 45, 825–841. doi: 10.1177/1741143217712721

Arnold, N., and Brooks, J. (2013). Getting churched and being schooled: making meaning of leadership practice. J. Cases Educ. Leadersh. 16, 44–53. doi: 10.1177/1555458913487034

Bentley, J. (2014). Report from TESOL 2014: 1.5 Billion English Learners Worldwide. Available online at: https://www.internationalteflacademy.com/blog/bid/205659/report-from-tesol-2014-1-5-billion-english-learners-worldwide

Blackmore, J. (2010). The other within: race/gender disruptions to the professional learning of white educational leaders. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 13, 45–61. doi: 10.1080/13603120903242931

Bloom, C. M., and Erlandson, D. A. (2003). African American women principals in urban schools: realities, (re)constructions, and resolutions. Educ. Adm. Quart. 39, 339–369. doi: 10.1177/0013161X03253413

Campbell-Stephens, R. (2009). Investing in diversity: changing the face (and heart) of educational leadership School Leadersh. Manage. 29, 321–331. doi: 10.1080/13632430902793726

Cannizzaro, S., and Gholami, R. (2018). The devil is not in the detail: representational absence and stereotyping in the ‘Trojan Horse’ news story. Race Ethn. Educ. 21, 15–29. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2016.1195350

Chakrabarty, N., Roberts, L., and Preston, J. (2012). Critical race theory in England. Race Ethn. Educ. 15, 1–3. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2012.638860

Coleman, M., and Campbell-Stephens, R. (2010). Perceptions of career progress: the experience of black and minority ethnic school leaders. School Leadersh. Manage. Formerly School Organ. 30, 35–49. doi: 10.1080/13632430903509741

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Curtis, S. (2017). Black women's intersectional complexities: the impact on leadership. Manage. Educ. 31, 94–102. doi: 10.1177/0892020617696635

Dantley, M., Beachum, F., and McCray, C. (2009). Exploring the intersectionality of multiple centers within notions of social justice. J. School Leadersh. 18, 124–133.

Delgado, R., and Stefanic, J. (2001). Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: New York University Press.

DeMatthews, D. (2016). Social justice dilemmas: evidence on the successes and shortcomings of three principals trying to make a difference. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2016.1206972. [Epub ahead of print].

Department for Education (2016). School Workforce in England: November 2015. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/school-workforce-in-england-november-2015

Dill, B. T., McLaughlin, A. E., and Nieves, A. D. (2007). “Future directions of feminist research: intersectionality,” in Handbook of Feminist Research, ed S. N. Hesse-Biber (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 629–637.

Dunbar, C., Rodriguez, D., and Parker, L. (2002). “Race, subjectivity, and the interview process,” in Handbook of Interview Research, eds J. Gubrium and J. Holstein (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 279–298.

England, C. (2017). Donald Trump blamed for Massive Spike in Islamophobic Hate Crime. Independent. Available online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/donald-trump-blame-islamophobic-anti-muslim-ban-hate-crime-numbers-southern-poverty-law-center-a7582846.html

Equality Human Rights Commission (2012). Public Sector Equality Duty Guidance for Schools in England. Available online at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/publication-download/public-sector-equality-duty-guidance-schools-england

Equality Human Rights Commission (2017). Voluntary Principles on Standards for Political Discourse. Available online at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/voluntary-principles-onstandards-for-political-discourse.pdf

Fitzgerald, T. (2006). Walking between two worlds: indigenous women and educational leadership. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 34, 201–213. doi: 10.1177/1741143206062494

Fuller, K. (2015). “Feminist theories and gender inequalities: headteachers, staff, and children,” in Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, ed. M. Peters (Singapore: Springer Science+Business Media), 1–6.

Fuller, K. (2017a). Women secondary headteachers in England: where are they now? Manage. Educ. 31, 54–68. doi: 10.1177/0892020617696625

Fuller, K. (2017b). “Assumptions and surprises - parallel and divergent social justice leadership narratives,” in A Global Perspective of Social Justice Leadership for School Principals, ed P. Angelle (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 87–110.

Gillborn, D. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. J. Educ. Pol. 20, 485–505. doi: 10.1080/02680930500132346

Gitlin, A. (1994). Power and Method: Political Activism and Educational Research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gunter, H. (2006). Educational leadership and the challenge of diversity. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 34, 257–268. doi: 10.1177/1741143206062497

Holvino, E. (2005). Theories of Difference: Making a Difference with Simultaneity. Available online at: http://slideplayer.com/slide/4446160/

Holvino, E. (2010). Intersections: the simultaneity of race, gender and class in organization studies, Gend. Work Organ. 17, 248–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00400.x

Holvino, E. (2012). “The “simultaneity” of identities: models and skills,” in New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development, eds C. L. Wijeyesinghe and B. W. Jackson III (New York, NY: New York University Press), 161–191.

Horsford, S. D. (2012). This bridge called my leadership: an essay on black women as bridge leaders in education. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 25, 11–22. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2011.647726

Johnson, L. (2017). The lives and identities of UK Black and South Asian head teachers: metaphors of leadership. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 45, 842–862. doi: 10.1177/1741143217717279

Leonardo, Z., and Porter, R. (2010). Pedagogy of fear: toward a Fanonian theory of ‘safety’ in race dialogue. Race Ethn. Educ. 13, 139–157. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2010.482898

López, G. (2003). The (racially neutral) politics of education: a critical race theory perspective. Educ. Adm. Quart. 39, 68–94. doi: 10.1177/0013161X02239761

Lumby, J. (2015). School leaders' gender strategies: caught in a discriminatory web. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 43, 28–45. doi: 10.1177/1741143214556088

Lumby, J., and Heystek, J. (2012). Leadership identity in ethnically diverse schools in South Africa and England. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 40, 4–20. doi: 10.1177/1741143211420609

Mansfield, K. C. (2014). How listening to student voices informs and strengthens social justice research and practice. Educ. Adm. Quart. 50, 392–430. doi: 10.1177/0013161X13505288

McPherson, W. (1999). The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/277111/4262.pdf

Mirza, H. (2009). Plotting a history: black and postcolonial feminisms in new times, race. Ethn. Educ. 12, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/13613320802650899

Mistry, M., and Sood, K. (2010). English as an additional language: assumptions and challenges. Manage. Educ. 24, 111–114. doi: 10.1177/0892020608090404

Mistry, M., and Sood, K. (2011). Rethinking educational leadership to transform pedagogical practice to help improve the attainment of minority ethnic pupils: the need for leadership dialogue. Manage. Educ. 25, 125–130. doi: 10.1177/0892020611401772

Mogra, I. (2016). The “Trojan Horse” affair and radicalisation: an analysis of Ofsted reports. Educ. Rev. 68, 444–465. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2015.1130027

Mohanty, C. T. (1988). Under western eyes: feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Fem. Rev. 30, 61–88. doi: 10.1057/fr.1988.42

Moorosi, P. (2014). Constructing a leader's identity through a leadership development programme: an intersectional analysis. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 42, 792–807. doi: 10.1177/1741143213494888

Moorosi, P., Fuller, K., and Reilly, E. (2017). “A comparative analysis of intersections of gender and race among black female school leaders in South Africa, United Kingdom and the United States,” in Cultures of Educational Leadership: Global and Intercultural Perspectives, ed P. Miller (Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan), 77–94.

Morrison, M. (2012). “Understanding methodology,” in Research Methods in Educational Leadership and Management, 3rd Edn, eds A. Briggs, M. Coleman and M. Morrison. (London: Sage), 14–28.

National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum (2015). Do Schools Get Extra Money To Support EAL Learners? Available online at: http://www.naldic.org.uk/eal-teaching-and-learning/faqs/doschoolsget_extra_moneyto_support_eal_learners/

Office of National Statistics (2012). Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales: 2011. Available online at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/ethnicityandnationalidentityinenglandandwales/2012-12-11

Rollock, N. (2013). A political investment: revisiting race and racism in the research process. Discourse Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 34, 492–509. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2013.822617

Rollock, N., Gillborn, D., Vincent, C., and Ball, S. J. (2015). The Colour of Class. Abingdon: Routledge eBook.

Rusch, E., and Horsford, S. (2009). Changing hearts and minds: the quest for open talk about race in educational leadership. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 23, 302–313. doi: 10.1108/09513540910957408

Santamaría, L. (2014). Critical change for the greater good: multicultural perceptions in educational leadership toward social justice and equity. Educ. Adm. Quart. 50, 347–391. doi: 10.1177/0013161X13505287

Shah, S. (2004). The researcher/interviewer in intercultural context: a social intruder! Br. Educ. Res. J. 30, 549–575. doi: 10.1080/0141192042000237239

Shah, S. (2006). Leading multiethnic schools a new understanding of Muslim youth identity. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 34, 215–237. doi: 10.1177/1741143206062495

Thompson, B. T. (1992). “Editor's introduction,” Language and Symbolic Power, ed P. Bourdieu (Cambridge: Polity Press), 1–31.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethn. Racial Stud. 30, 1024–1054. doi: 10.1080/01419870701599465

Watts, J., and Davenport, J. (2014). Doreen Lawrence: I Still Have to Close My Bag in a Shop to Show I'm Not Stealing. London Evening Standard. Available online at: http://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/doreen-lawrence-i-still-have-to-close-my-bag-in-a-shop-to-show-im-not-stealing-9149537.html

Wilson, V., Powney, J., Hall, S., and Davidson, J. (2006). Who gets ahead? The effect of age, disability, ethnicity and gender on teachers' careers and implications for school leaders. Educ. Manage. Adm. Leadersh. 34, 239–255. doi: 10.1177/1741143206062496

Witherspoon, N., and Taylor, D (2010). Spiritual weapons: black female principals and religio-spirituality. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 42, 133–158. doi: 10.1080/00220621003701296

Yazgan, P., Utcu, D., and Sirkeci, I. (2015). Editorial – Syrian crisis and migration. Migr. Lett. 12, 181–192. Available online at: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=477035

Keywords: educational leadership, school headteacher/principal, intersectionality, race, gender, religion

Citation: Fuller K (2018) New Lands, New Languages: Navigating Intersectionality in School Leadership. Front. Educ. 3:25. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00025

Received: 13 January 2018; Accepted: 10 April 2018;

Published: 30 April 2018.

Edited by:

Paula A. Cordeiro, University of San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Melanie Carol Brooks, Monash University, AustraliaCorinne Brion, University of San Diego, United States

Copyright © 2018 Fuller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kay Fuller, S2F5LkZ1bGxlckBub3R0aW5naGFtLmFjLnVr

Kay Fuller

Kay Fuller