- 1College of Arts, Social Sciences and Education, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 2The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 3School of Health, Medicine and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 4School of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

Background: Secondary education for Indigenous children from remote communities requires separation from their communities and families. As these students transition to boarding schools, they face several challenges that are additional to those faced by their non-Indigenous peers. In response, adequate academic and emotional well-being support needs to be provided by school and residential staff. This systematic review reports on international and Australian capacity development initiatives for education and boarding staff that support these students.

Methods: Five databases were searched using database-specific search strings, considering peer-reviewed articles and gray literature, published between 2001 and 2016. The resultant publications were screened to identify (a) their nature and quality and (b) their characteristics in terms of aims, strategies, and outputs.

Results: Seven hundred thirty-six citations were identified; 51 full text publications met inclusion criteria for assessment. Seven publications were eligible for review. Staff capacity building initiatives encompassed a range of approaches, including training, feedback, reflective practice, mentoring, networking, and supervision. Only one publication focused specifically on the support of education staff, others were centred on improving educational, behavioral, and emotional outcomes for Indigenous boarding school students. All of the research was descriptive, with only two original research publications.

Conclusion: Despite a variety of approaches being described in brief, we found no high quality research that focused exclusively on staff capacity building approaches in the Indigenous boarding school context. The few publications available to review were exclusively descriptive in nature, highlighting a clear need for well-executed evaluation research.

Background

The transition from primary to secondary school brings changes in social interactions, academic expectations, and school environments, all of which occur concurrently (Anderson et al., 2000). Students confront the important challenges of social acceptance, including making friends, “fitting in,” and possibly dealing with bullying (Howard and Johnson, 2004; Gerner and Wilson, 2005). The secondary school environment is considerably different to the primary school environment; schools are larger and more competitive (Demetriou et al., 2000) and more demands are placed on students with greater emphasis placed on evaluation (Wigfield et al., 1991; Anderson et al., 2000; Howard and Johnson, 2004; Benner and Graham, 2009). Ability is more highly valued than effort (Jackson and Warin, 2000). Hence the primary to secondary transition is a social and academic turning point for children (Smith et al., 2008; Langenkamp, 2009) and has been shown to be a stressful event for many (Rice et al., 2011; Hanewald, 2013).

Successful school transitions are facilitated by situational variables such as having a supportive home environment (Rice, 1997), accessible teachers in high school, a strong peer network, and an older sibling (Anderson et al., 2000). Secondary school teachers and other staff can assist students by inducting students to increase familiarity with the new school environment (Graham and Hill, 2003). They can also strengthen student characteristics that may facilitate successful transition experiences, such as appropriate knowledge and thinking skills to cope with the increased academic challenges, being conscientious and having the ability to work independently, and coping strategies that they can employ during times of difficulty (Anderson et al., 2000). Despite the challenges, most students are able to adjust well to the primary to secondary school transition, and any negative effects are relatively short term (Anderson et al., 2000).

For some students, combinations of demographic characteristics, interpersonal relationships, social and emotional support as well as the availability of resources, personal characteristics, and structural factors such as poverty, accumulate to render children particularly vulnerable (Mechanic and Tanner, 2007). Boden et al. (2016) found that reduced levels of protective factors such as positive family relationships were related to lower resilience and higher levels of family risk, but the role played by specific risk factors in shaping transitions is unclear (Boden et al., 2016). What is known is that children with access to relational supports and resources, and particularly positive parent–child relationships, are likely to do better in transitions than those who do not have these benefits (Côté, 2006; Berzin, 2010). For some students, the stress resulting from transition can have far-reaching effects on self-esteem (Jindal-Snape and Miller, 2008), resulting in behavioral problems (Howard and Johnson, 2004), mental health concerns (Lord et al., 1994; Zeedyk et al., 2003; Gutman and Eccles, 2007), and a substantial decline in academic performance (Palmer, 2008). The effects of these social concerns are heightened by their concurrent nature, producing an accumulation of stress factors (Griebel and Berwanger, 2006). In turn, elevated levels of stress hormones are known to suppress an individual’s ability to generate an effective immune response and can influence learning by acting on parts of the brain involved in memory (Turner-Cobb et al., 2008).

Students from remote communities are often required to attend boarding schools for secondary education because of a lack of secondary school options in their home communities. A comparison of the experiences of primary to secondary transition of boarders and non-boarders at 21 Western Australian Catholic schools found that boarding students reported experiencing significantly more emotional difficulties and depression, anxiety, and stress than non-boarders. These emotional and mental health factors impacted boarding students overall sense of well-being while they schooled away from home rather than social factors, e.g., sense of connection with peers and school (Mander et al., 2015).

Indigenous students from remote communities are often compelled to attend boarding schools because (a) there has never been a school in their community; or (b) educational institutions have been closed as a result of irregular school attendance, low retention rates, and achievements in literacy and numeracy (Wilson, 2014). Indigenous students transitioning to boarding school not only face the same challenges as experienced by their non-Indigenous peers but also having to deal with moving across cultures, languages, and world views (Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009; Perso et al., 2012). In addition, many Indigenous students from remote communities come from socially disadvantaged communities where poverty, familial unemployment, welfare dependency, and/or poor health and housing conditions are common. Cultural, social, and language differences, combined with a lack of school readiness, being away from familiar support of family and community, and the feeling of shame at not having higher achievement levels may eventually lead to anxiety and school leaving (Morgan et al., 2010). The challenge is to provide better preparation for boarding school transitions to Indigenous students and families while they are still at primary school, and better support for students at boarding schools. As well, school staff can support students through culturally competent practice, defined as “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes and policies that come together in a system, agency or among professionals that enable that system, agency, or professions to work effectively in cross-cultural situations” (Cross, 1989).

Boarding schools that cater for Indigenous students often struggle to meet the complex needs of these students. For many schools, there is a tension between aspirations to support students to realize their full potential and having adequate resources to meet this goal (Florisson, 2014). Some schools have implemented strategies such as (a) Indigenous awareness-building programs; (b) Indigenous scholarships and bursaries; (c) relationship building initiatives between Indigenous schools and communities; and (d) Indigenous Education Centres (Barr, 2009).

Providing support to Indigenous students experiencing transitional stressors can be exceedingly complex for boarding school, boarding house, and other staff members. Like the students, boarding school staff are often working cross-culturally and cross-linguistically. Staff may have limited understanding of the home environments and experiences of the students whom they support. Staff roles include supporting students to adjust to a vastly different way of being in the world, including values, behaviors, living environments and experiences, peer relationships, and academic expectations. Staff also advocate within the school and boarding house environments to better attend to the needs of students. These roles are critical to the successful transitions of Indigenous students to boarding school. This paper reports a review of the literature to determine what staff capacity development interventions have been documented for education, boarding, and support staff to work effectively with Indigenous boarding school students.

The Context

This review directly informs the provision of Indigenous student support by Queensland Education’s Transition Support Services (TSS), Department of Education and Training, Queensland Government. TSS has been working with students from Cape York communities and Palm Island in their transitions to boarding schools since 2007. Currently, TSS is using a case management approach that is based on a “skilled helper” mentoring model. While this model has been effective in engaging with and supporting students and their families, TSS identified the need for a new model of practice to better support the well-being and resilience of students. Also recognized was a need for regular professional mentoring/debriefing support for staff in their provision of structured support for students. In collaboration with CQUniversity Australia, TSS is developing a new model of student support that focuses on the resilience and well-being of their students. This review informs the capacity development processes of TSS in preparation for the soon-to-be-implemented change model. The review informs TSS by reporting on initiatives found in schools and boarding houses that focus on staff capacity development to support the well-being of Indigenous children.

Methods

The aim of this systematic literature review is to identify staff capacity development initiatives that support the well-being of Indigenous children in their transition to boarding schools. The research questions are determined as follows:

1. What is the type and quality of the included publications?

2. What are the characteristics of staff capacity development initiatives reported in the literature?

3. What are the reported outcomes of the above initiatives?

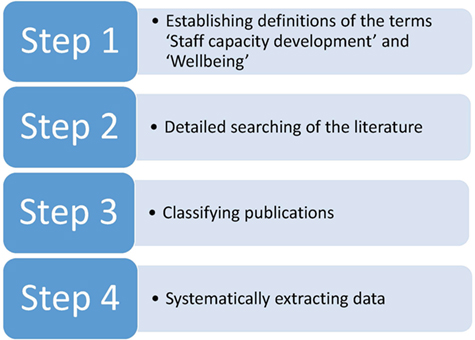

A four-step systematic review method, as described by Bainbridge et al. (2014), was adopted (Figure 1) and described in detail below.

Step 1: Establishing Definitions of the Terms “Staff Capacity Development” and “Well-being”

This literature review examined staff capacity development, in the context of supporting the well-being of Indigenous students’ transitioning to boarding schools. The terms young people and children are used interchangeably in the literature to describe students between the ages of 11 and 19 years. We used the Wignaraja (2009) definition for “Capacity development,” which is the establishment of conditions that will allow individuals to engage in the process of learning and adapting to change. Staff capacity development encompassed building and enhancing knowledge, skills, confidence, and competency, including formalized training, peer mentoring, and supervision. Contexts included boarding school/house/support service environments involving Indigenous students. For the context of this study, well-being was defined as meeting basic physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual needs of the individual; and where denial of these needs will result in behavioral and emotional difficulties (Tsey and Every, 2000).

Step 2: Detailed Searching of the Literature

The start year of the search, 2001, was chosen based on the release of the Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs report on multiple pathways for Indigenous students (MCEETYA, 2001). The 16-year time period from 2001 to 2016 was considered to be adequate to provide comprehensive coverage of relevant initiatives that have been documented since the release of the above report. In addition to Australian literature, publications from New Zealand, Canada, and USA were considered. These countries were included as they have similar colonial history, laws, political structures, and socioeconomic outcomes with respect to Indigenous peoples (Lithopoulos, 2007). Peer-reviewed journal articles and gray literature were included to ensure comprehensive coverage of existing literature and to avoid publication bias.

Search 1

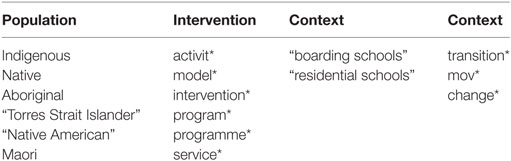

The following combination of terms was searched in both title and abstract for our preliminary search: “staff capacity development” OR “staff capacity building” AND “Indigenous students” OR “Indigenous children” OR “Indigenous young people” AND “boarding school” OR “boarding schools.” Our first search on staff capacity building initiatives yielded no results due to the narrow focus on the support of Indigenous students’ transitioning to boarding school.

Search 2

We subsequently conducted a second search, following consultation with an expert librarian, to identify support strategies (programs and activities) for Indigenous children transitioning to boarding schools. The intention to search the literature identified for any described staff capacity building components. Please find the key concepts for our database search in Table 1. Search 2 was conducted using the following terms in the title and abstract: activit* OR model* OR intervention* OR program* OR programme* OR service* AND “boarding school” OR “boarding schools” OR “residential school” OR “residential schools” AND Indigenous OR Native OR Aboriginal OR “Torres Strait Islander” OR “Native American” OR Maori AND Transition* OR mov* OR chang*. The following databases were searched: Informit, Proquest, JStor, Wiley, and Google Scholar. Separate searches were performed for each database using database-specific subject headings and keywords. In each case, Boolean logic was applied. Gray literature searches were performed through the Australian Indigenous Health Info Net and Closing the Gap Clearinghouse (AIHW and AIFS); Alberta Health Services, Canada; and Education Counts, New Zealand. Electronic database searching was completed on 24/04/16.

Screening According to Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

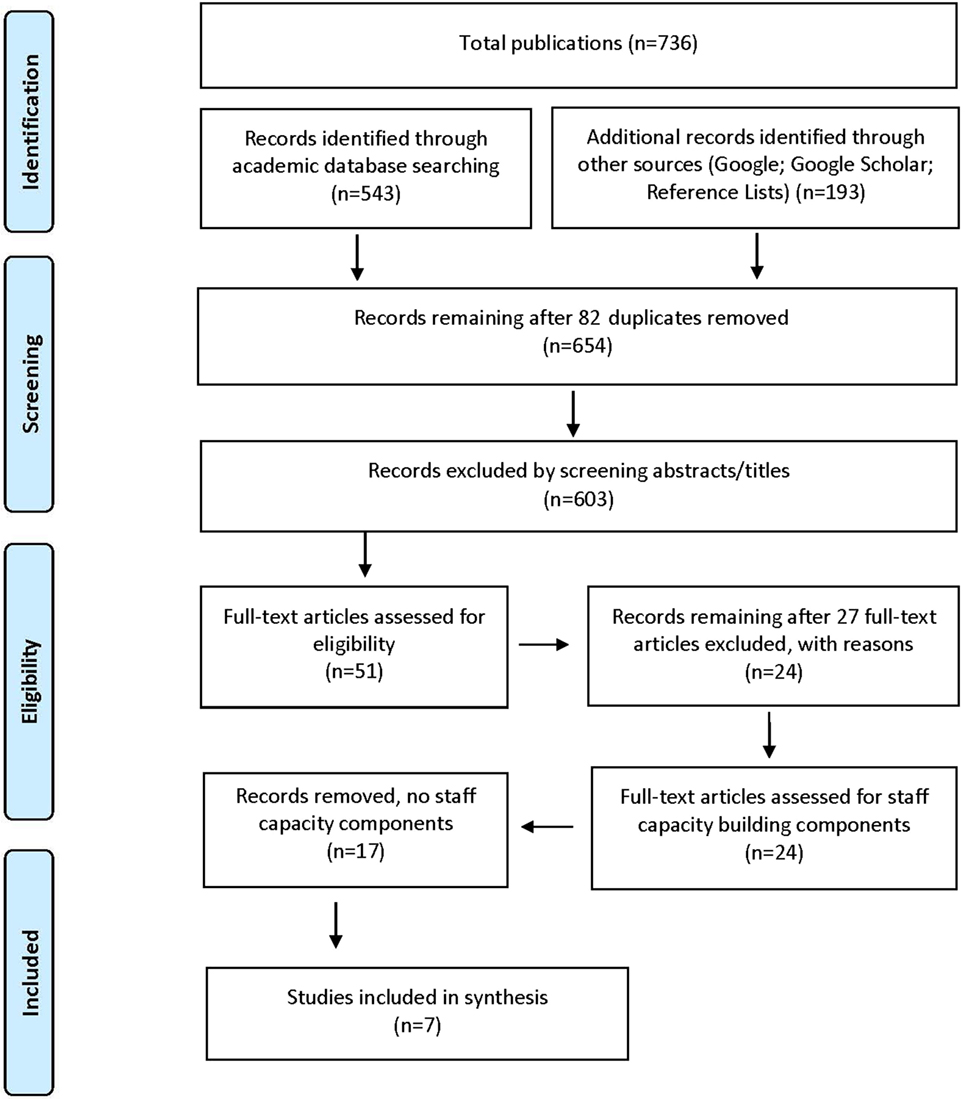

The combined database searches yielded 736 references. These were imported into the bibliographic citation management software, EndNote X7 and 82 duplicates removed. After removing duplicates, 654 publications were screened by one author (Marion Heyeres) to remove articles that did not meet inclusion criteria, based on the titles and abstracts. Inclusion/exclusion criteria for the first stage of the search were established at the onset of the review and included

• the key search terms were included in the title and abstract;

• the study was published between 2001 and 2016;

• the study was available in English;

• the study focused on Indigenous boarding school students from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and/or USA.

Fifty-one out of 654 publications (7.8%) were identified for full text review. Another author (Janya McCalman) blindly assessed the 51 publications to verify inclusion and classification selected by the main researcher. There was an initial 61% agreement, with full consensus achieved after negotiations between the two authors, which resulted in 24 papers remaining. For the final step of the search, an additional inclusion criterion was applied that publications should report on the description or evaluation of a staff capacity building initiative. Four authors (Marion Heyeres, Janya McCalman, Roxanne Bainbridge, and Michelle Redman-MacLaren) independently assessed the remaining 24 publications to assess the inclusion of publications against these criteria.

Step 3: Classifying Publications

The papers that met the search criteria were classified by (a) the “type of research” and (b) “study quality.” Consistent with Sanson-Fisher et al. (2006) classification system, publications were grouped according to original research; reviews; program descriptions; discussion papers/commentaries; or case reports. Original research studies were then classified under the following three categories:

• Measurement research: publications that developed or tested a measure of staff capacity building in Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff;

• Descriptive research: publications where the primary aim was to explore issues, processes/models, or attributes related to staff capacity building;

• Intervention research: publications in which the aim was to test the effectiveness of an intervention implemented with education and/or boarding school staff.

Research is often assessed by the quality of the methodology used to generate data. We had intended to apply the quality criteria to quantitative (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 2016) and qualitative (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2013) studies. However, due to a paucity of original research studies (n = 2/7 or 29%), peer review was used as a benchmark to determine research quality (Sanson-Fisher et al., 2006).

Step 4: Systematically Extracting Data

The characteristics and outcomes of staff capacity development initiatives were identified by hand searching the included publications and extracting data according to a predefined framework. The elements of this framework were first author; year of publication; country of origin; context; target population; staff capacity building initiative; aim; strategies; and staff capacity development outcomes.

Results

The Quantity, Nature, and Quality of Identified Publications

Figure 2 details the process of how the publications were screened and assessed, as recommended by the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” statement (PRISMA, 2015). Seven publications were included in the qualitative synthesis of the review.

Classification on Type and Quality of Publications

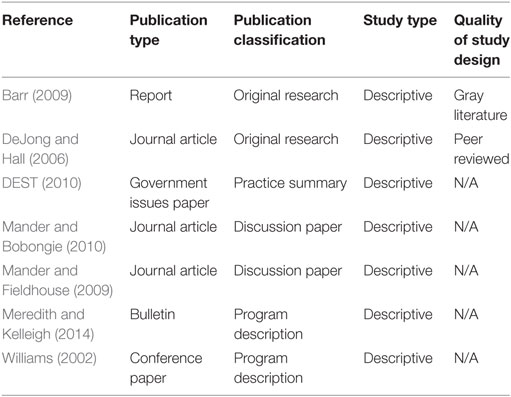

In Table 2, the type and quality of publications is displayed. Publications included three journal articles (DeJong and Hall, 2006; Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009; Mander and Bobongie, 2010), one government issues paper (DEST, 2010), one report (Barr, 2009), and one conference paper (Williams, 2002). All included papers were classified as descriptive research. Only two documents were original research (DeJong and Hall, 2006; Barr, 2009), of which only one was peer reviewed (DeJong and Hall, 2006) and therefore met the established quality criteria.

The Characteristics of Staff Capacity Building Initiatives

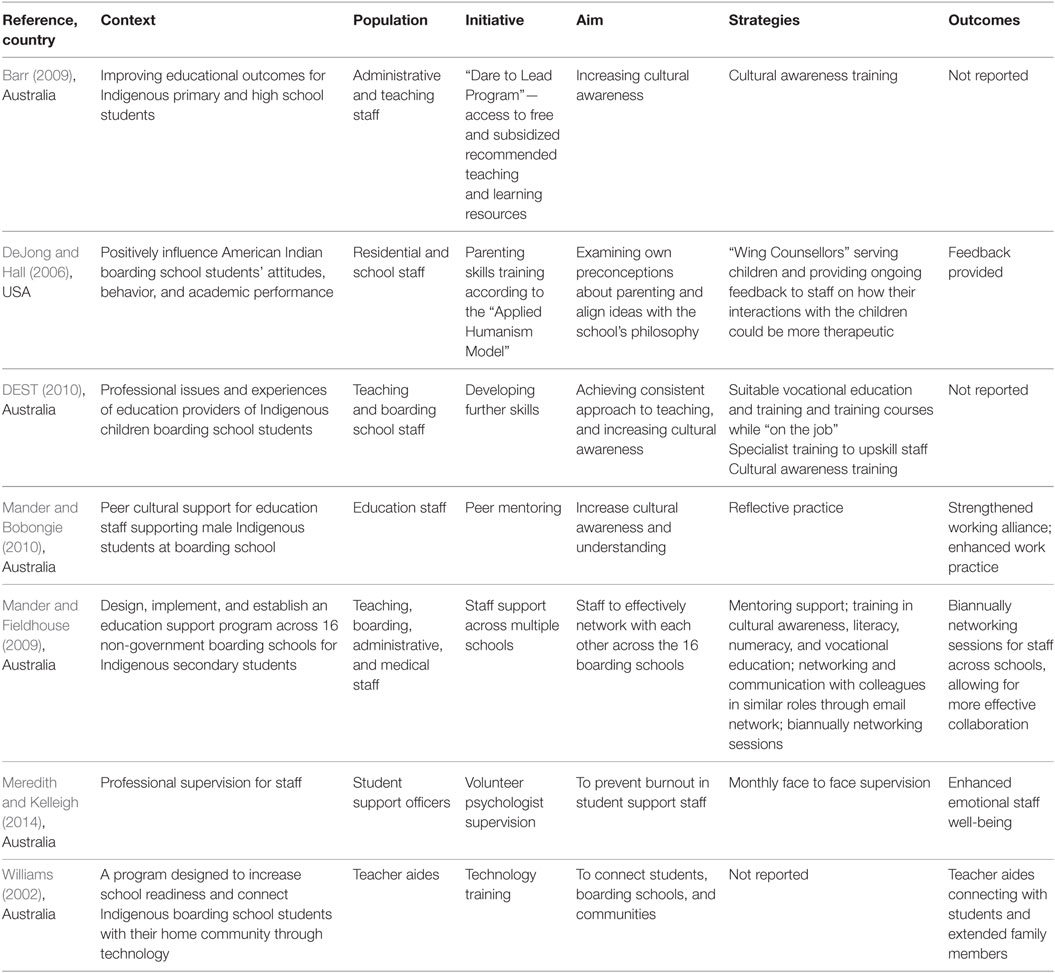

Table 3 displays the key characteristics of the staff capacity building initiatives reported in the seven (n = 7) included publications. The characteristics of publications on supporting Indigenous students who transition to boarding schools are described in detail.

Populations and Locations

The seven included publications that reported on staff capacity building initiatives were implemented in various places across Australia (Williams, 2002; Barr, 2009; Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009; DEST, 2010; Mander and Bobongie, 2010; Meredith and Kelleigh, 2014) and in the USA (DeJong and Hall, 2006).

Aims

The majority of publications focused on improving educational, behavioral, and emotional outcomes for Indigenous boarding school students (6/7 or 86%). The aim of staff capacity initiatives to support Indigenous students’ transitions to boarding schools included the development of quality relationships between students and staff that were warm and caring, while including clear and firm expectations about rules and responsibilities (DEST, 2010). In DEST (2010), the aim of the staff capacity enhancement was to provide a shared language and methodology to achieve a consistent approach to teaching. Williams (2002) was concerned with the issue of teacher aides connecting with students who were temporarily away from boarding schools. DeJong and Hall (2006) described the training of education and boarding staff of three residential schools in USA in parenting skills. The training was based on an “Applied Humanism Model,” which intended to train staff to interact in a more therapeutic way, to examine their own preconceptions on parenting, align ideas with the school’s philosophy, and positively influence Native American student’s attitudes, behavior, and academic performance (DeJong and Hall, 2006).

One of the most frequently mentioned requirements to successfully supporting Indigenous students was for school and boarding staff to have strong cultural awareness and to be able to translate it into practice (Barr, 2009). Increasing cultural awareness in staff was reported in three publications (Barr, 2009; DEST, 2010; Mander and Bobongie, 2010). For example, Mander and Bobongie (2010) reported a peer mentoring approach geared to achieve improved cultural awareness and understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous education staff.

Williams (2002) aimed to assist successful student transition through adequate preparation of primary school children for their time away from home. Extended support to and regular communication with families and communities using information and communication technology was seen as a vital element to supporting students while away from home. Within this context, staff capacity development encompassed the training of teacher aides to enable them to connect with their children and extended family members.

Mander and Fieldhouse’s (2009) paper aimed to support education staff across 16 boarding schools to effectively communicate and network with each other. And finally, Meredith and Kelleigh’s (2014) focused exclusively on the well-being of student support staff, aiming to prevent support staff burnout by monthly supervision sessions.

Strategies

Many studies reported multiple strategies for supporting Indigenous students. There were four key strategies used to enhance staff capacity to implement Indigenous student support strategies: training, reflective practice, mentoring/supervision, and networking and communication.

Training was the most commonly reported method of enhancing staff capacity, reported in six (n = 6) publications. Training was provided in cultural awareness for individual staff members and across the curriculum (n = 3). Cross-cultural awareness training was often offered mandatorily (Williams, 2002; Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009; DEST, 2010). Barr (2009) captured the essence of a cultural competence training program as follows:

The important issue was the teachers really getting to know the kids, knowing where they were coming from, valuing their culture and actually seeing that they did bring a lot of really valuable stuff to school, that hadn’t been widely recognised and wasn’t valued. And the reason it wasn’t being valued is because it simply wasn’t understood. Teachers need to have a look at the cultural screen that they use to view the world and to be really aware of that cultural screen … And be a lot less judgmental. (p. 23)

Training was also provided through vocational education and training (VET) courses for staff while on the job (n = 1), through specialist training to upskill staff (n = 1), and through training in literacy, numeracy, and vocational education (n = 1). For example, in the “Work Program: Core Issue 6 Boarding” of the Australian Government, the challenge to finding staff with the right skills and attitude was seen as a barrier to provide adequate support. Consequently, additional support for already qualified staff was seen as highly important (DEST, 2010). Training programs to improve literacy, numeracy, and cultural awareness as well as general vocational education and technology skills were made available to upskill staff. Training was provided either before staff took up their positions or via VET and tertiary courses while on the job (DEST, 2010).

Mentoring/professional development was reported in two studies, including one on one support for teaching, residential, administrative, and medical staff (n = 1) (Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009) and professional supervision provided by volunteer counselors to support staff (n = 1) (Meredith and Kelleigh, 2014). Mander and Bobongie (2010) described the benefits of peer mentoring between Indigenous and non-Indigenous education staff. Being non-Indigenous, Mander’s understanding of cultural issues faced by Indigenous boys and his ways of dealing with them was supported through his self-reflectory practice in interaction with his Indigenous colleague. A volunteer supervision partnership between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Psychology Interest Group and Yalari, a Queensland-based Indigenous organization which places Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in boarding schools throughout Australia was described by Meredith and Kelleigh (2014). Positive feedback from student support officers, coordinators and volunteer psychologists covered a variety of areas: emotional support and sound advice for staff, the importance of keeping students emotionally safe; a deepening of understanding the challenges Indigenous children face when being schooled away from home; and gaining awareness of casual racism.

DeJong and Hall (2006) reported on reflective practice, where staff was being trained using the Applied Humanism model. This approach helped them examine their own preconceptions about parenting and to align their ideas with the site’s philosophy. Results showed that children were more resilient when given structure and support, behavior expectations were clear and consequences were logical rather than punitive, and when children were treated with respect.

Networking and communication was reported in one publication (n = 1), where colleagues in similar roles networked across multiple schools through an email network (Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009). This email network encouraged multiple links to be forged between staff at participating schools, to network and communicate with colleagues in similar roles about various aspects of supporting students. Biannual networking sessions for staff across the schools allowed them to come together and share, network, and discuss the challenges and success they have experienced in supporting students with the transition into residential schools.

Outcomes

Only five (71%) of the seven included publications reported outcomes for participants. Only two (29%) of these reported benefits to students. One reported therapeutic interactions with students and feedback to staff by “Wing Counsellors” (DeJong and Hall, 2006); and the second reported improved connections between schools with students and extended families, whereby information technology training allowed teacher aides to strengthen these relationships (Williams, 2002). The other three publications (43%) reported broader benefits for staff and schools. These included enhanced emotional staff well-being through regular face-to-face supervision sessions (Meredith and Kelleigh, 2014); a strengthened working alliance and enhanced cross-cultural work practice between two staff members (Mander and Bobongie, 2010); and more effective collaboration across 16 boarding schools through biannual networking sessions for staff (Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009).

Discussion

Transition to secondary schooling, and particularly to boarding school, is a time of adjustment for all young people who can provoke feelings of stress and anxiety (Rice et al., 2011; Hanewald, 2013). It must be acknowledged that transition to boarding school for Indigenous children is far more complex than for their non-Indigenous peers (Barr, 2009; Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009). Respectively, education and boarding staff that support Indigenous students face additional challenges to the staff in mainstream educational settings. Our literature search found that there was little documentation in the literature of staff capacity development initiatives to support Indigenous students at boarding schools.

Type and Quality of Publications

As outlined in the findings, all included publications reporting staff capacity development initiatives were of descriptive nature. Only two publications out of seven identified as original research, and these included one peer-reviewed journal article and one non-peer-reviewed gray literature. There has not been much progress since early 2000 in producing high quality research that evaluates the effectiveness of staff capacity development initiatives to better support students in their transition to boarding schools. Evaluation of the effectiveness of staff capacity development is therefore required (Mellor and Corrigan, 2004).

Characteristics of Staff Capacity Development Initiatives and Reported Outcomes

The main characteristics of staff capacity development initiatives reported in the literature (Table 3) included co-mentoring, supervision, cultural awareness training, provision of feedback on work practices, training in literacy and numeracy, vocational education, and networking. Co-mentoring, as reported in two publications (DEST, 2010; Mander and Bobongie, 2010), resulted in improved skills and knowledge as well as strengthening group coherence through support from within.

Generally, finding the right staff for boarding houses is a major concern for schools, parents, and students and continues to be a challenge in the provision of quality support for students. A background in teaching and/or youth work is seen as favorable prerequisite for boarding house staff. However, empathy and commitment to enhancing student’s well-being and resilience is equally important. Staff training in numeracy and literacy teaching skills can be provided either before the staff takes up the position or during employment with suitable VET courses. In addition to upskilling staff, capacity development can be directed toward providing a shared language and methodology to achieve consistency of approach to both support and educate across school and boarding house (DEST, 2010).

The need for cultural awareness to be embedded in all areas of school activities was reported across the literature (Barr, 2009; Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009; DEST, 2010; Mander and Bobongie, 2010). Strategies to achieve cultural competency in non-Indigenous staff include professional training (Barr, 2009) and peer mentoring, as described by Mander and Bobongie (2010). However, there is more to it: “Cultural competence requires more than an awareness of Indigenous culture, but a willingness to engage with heart as well as mind…” (Sims, 2011, p. 12). Teachers really need to engage with students: know where they come from; value their culture; and acknowledge the valuable assets they bring to the school.1 If we truly want to move forward in Indigenous education, we must break down the ethnocentric attitude of the “Western way” which privileges dominant views and is still entrenched in society as the only valid and authentic way of viewing the world (Perso, 2012).

The evidence of reported outcomes of staff capacity development initiatives provides little guidance for those wishing to enhance staff capacity to better meet the needs of Indigenous students’ transitioning to boarding schools. As evidenced in one project (Williams, 2002), there was no deliberate professional development program put in place, either in the home community or at the destination boarding schools to support teachers and boarding house staff. They just got on with the job and learned and worked together. This confirms our experience, and as evidenced in a number of publications, boarding school and boarding house staff learn how to provide specialist support for Indigenous students on the job. It is also evident that there is very limited documentation about this on-the-job learning.

Application and Further Recommendations

The purpose of this review was to inform the staff capacity development of the TSS staff who support Indigenous students from Cape York and Palm Island communities to form a community of practice to share and document strength-based practices across seven Queensland boarding schools. Strategies for sharing best practices in supporting Indigenous students included an initial meeting to which boarding school principals and other staff, boarding house staff, community Mayors, and educational representatives, and TSS staff were invited to establish the community of practice and brainstorm strategies for student well-being enhancement. Strategies were established for sustained networking through the group, including the development of a reference group, advocacy group, email network, and Facebook page. The sharing of best practice student support and staff capacity building initiatives will commence at the start of 2017 and will be carefully documented and published in a later paper.

Limitations

A limitation of this review is that we found only seven studies that we considered eligible for inclusion. Only two publications were exclusively concerned with the support of education staff. Evidence derived from the remaining five publications relied on brief descriptions of staff capacity building within the broader context of the support of Indigenous boarding school students. Furthermore, the majority of included publications were of qualitative and descriptive nature. Most information was derived from short paragraphs about staff capacity building and support within the main body of evidence on student focused challenges and/or achievements.

Conclusion

Our systematic review found limited evidence of staff capacity building initiatives in the Indigenous boarding school context. Evidence extracted from publications from Australia and the USA showed that staff capacity development methods included various training programs to improve literacy, numeracy, and cultural awareness as well as general vocational education to upskill staff. Other strategies were professional feedback on interpersonal interactions between staff and students, reflective practice to improve cultural understanding, mentoring, networking, and professional supervision. Outcomes reported on staff capacity development included benefits such as feedback provided on work practice, enhanced emotional staff well-being, strengthened working alliances, enhanced cross-cultural work practice, and increased effectiveness of collaboration across a number of boarding schools, better connection between students, schools, and communities. Methodologically, this review highlighted exclusively descriptive research in the field of staff capacity building in the Indigenous boarding school context. As descriptive research does not provide evidence on whether initiatives were successful in improving capacity in staff, nor provide an explanation on how to improve staff capacity, it is evident that there is a clear need for more rigorous evaluation research.

Author Contributions

MH: lead author contributed to all areas of manuscript. JM: reference screening, some writing, and proof reading. RB: reference screening, some writing, and proof reading. M-RM: reference screening, some writing, and proof reading.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This review is part of a 5-year NHMRC 1076774 project: psycho-social resilience, vulnerability, and suicide prevention: a mentoring approach to modifying suicide risk for remote Indigenous students at boarding school.

Footnote

- ^Cahil, R., and Collard, G. What Works – The Work Program. A Conversation about Building Awareness.

References

Anderson, L. W., Jacobs, J., Schramm, S., and Splittgerber, F. (2000). School transitions: beginning of the end or a new beginning? Int. J. Educ. Res. 33, 325–339. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(00)00020-3

Bainbridge, R., Tsey, K., McCalman, J., and Towle, S. (2014). The quantity, quality and characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian mentoring literature: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 14:1. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1263

Barr, J. (2009). Indigenous Education Initiatives in AASN Schools: Building Relationships. Sydney: Australian Anglican Schools Network.

Benner, A. D., and Graham, S. (2009). The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Dev. 80, 356–376. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01265.x

Berzin, S. C. (2010). Educational aspirations among low-income youths: examining multiple conceptual models. Child. Sch. 32, 112–124. doi:10.1093/cs/32.2.112

Boden, J. M., Sanders, J., Munford, R., and Liebenberg, L. (2016). The same but different? Applicability of a general resilience model to understand a population of vulnerable youth. Child Indic. Res. 1–18. doi:10.1007/s12187-016-9422-y

Côté, J. (2006). Identity studies: how close are we to developing a social science of identity? An appraisal of the field. Identity 6, 3–25. doi:10.1207/s1532706xid0601_2

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2013). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Making Sense of Evidence. Oxford: Better Value Healthcare Ltd. Available at: http://www.casp-uk.net/

Cross, T. L. (1989). Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care: A Monograph on Effective Services for Minority Children Who Are Severely Emotionally Disturbed. Washington, DC: Georgetown Univ. Child Development Center.

DeJong, J., and Hall, P. (2006). Best practices: a cross-site evaluation. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 13, 177–210.

Demetriou, H., Goalen, P., and Rudduck, J. (2000). Academic performance, transfer, transition and friendship: listening to the student voice. Int. J. Educ. Res. 33, 425–441. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(00)00026-4

Effective Public Health Practice Project. (2016). Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Hamilton: McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences.

Florisson, J. (2014). Achieving Positive Outcomes through Boarding, for Remote Indigenous Students. Esperance: Boarding Training Australia.

Gerner, B., and Wilson, P. H. (2005). The relationship between friendship factors and adolescent girls’ body image concern, body dissatisfaction, and restrained eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 37, 313–320. doi:10.1002/eat.20094

Graham, C., and Hill, M. (2003). Negotiating the Transition to Secondary School. SCRE Spotlight. Edinburgh: ERIC.

Griebel, W., and Berwanger, D. (2006). Transition from primary school to secondary school in Germany. Int. J. Transit. Child. 2, 32–39.

Gutman, L. M., and Eccles, J. S. (2007). Stage-environment fit during adolescence: trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 43, 522. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.522

Hanewald, R. (2013). Transition between primary and secondary school: why it is important and how it can be supported. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 38, 68. doi:10.14221/ajte.2013v38n1.7

Howard, S., and Johnson, B. (2004). Transition from Primary to Secondary School: Possibilities and Paradoxes. Ph.D. Dissertation, Australian Association for Research in Education, Melbourne.

Jackson, C., and Warin, J. (2000). The importance of gender as an aspect of identity at key transition points in compulsory education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 26, 375–391. doi:10.1080/713651558

Jindal-Snape, D., and Miller, D. (2008). A challenge of living? Understanding the psycho-social processes of the child during primary-secondary transition through resilience and self-esteem theories. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 20, 217–236. doi:10.1007/s10648-008-9074-7

Langenkamp, A. G. (2009). Following different pathways: social integration, achievement, and the transition to high school. Am. J. Educ. 116, 69. doi:10.1086/605101

Lithopoulos, S. (2007). International Comparison of Indigenous Policing Models. Canada: Public Safety Canada.

Lord, S., Eccles, J., and McCarthy, K. (1994). Risk and protective factors in the transition to junior high school. J. Early Adolesc. 14, 162–199. doi:10.1177/027243169401400205

Mander, D., and Bobongie, F. (2010). Working alliances: the importance of accessing peer/cultural support in educational practice. Aust. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 27, 41–53. doi:10.1375/aedp.27.1.41

Mander, D., and Fieldhouse, L. (2009). Reflections on Implementing an Education Support Programme for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Secondary School Students in a Non-Government Education Sector: What Did We Learn and What Do We Know? Melbourne: The Australian Community Psychologist.

Mander, D. J., Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2015). The social and emotional well-being and mental health implications for adolescents transitioning to secondary boarding school. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Health 8, 131.

MCEETYA. (2001). Report of the MCEETYA Taskforce on Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Schools. Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs.

Mechanic, D., and Tanner, J. (2007). Vulnerable people, groups, and populations: societal view. Health Aff. 26, 1220–1230. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1220

Mellor, S., and Corrigan, M. (2004). The Case for Change: A Review of Contemporary Research on Indigenous Education Outcomes (No. 47). Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Morgan, M., Drew, N., Purdie, N., Dudgeon, P., and Walker, R. (2010). Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practices. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Palmer, B. (2008). The secondary review and its consequences for secondary education in the northern territory. Curric. Teach. 23, 65–80. doi:10.7459/ct/23.2.06

Perso, T., Kenyon, P., and Darrough, N. (2012). Transitioning Indigenous Students to Western Schooling: A Culturally Responsive Program. Refereed Conference Paper. Brisbane. Available at: http://www.acu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/464723/Perso,_Thelma,_Kenyon,_Pam_and_Darrough,_Neila_Refereed.pdf

Perso, T. F. (2012). Cultural Responsiveness and School Education: With Particular Focus on Australia’s First Peoples; A Review & Synthesis of the Literature. Menzies School of Health Research, Centre for Child Development and Education, Darwin Northern Territory.

PRISMA. (2015). Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Available at: http://prisma-statement.org/PRISMAStatement/FlowDiagram.aspx

Rice, F., Frederickson, N., and Seymour, J. (2011). Assessing pupil concerns about transition to secondary school. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 244–263. doi:10.1348/000709910X519333

Rice, J. K. (1997). The disruptive transition from middle to high school: opportunities for linking policy and practice. J. Educ. Policy 12, 403–417. doi:10.1080/0268093970120508

Sanson-Fisher, R. W., Campbell, E. M., Perkins, J. J., Blunden, S. V., and Davis, B. B. (2006). Indigenous health research: a critical review of outputs over time. Med. J. Aust. 184, 502.

Sims, M. (2011). Early Childhood and Education Services for Resource Sheet No. 7 for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Smith, J. S., Akos, P., Lim, S., and Wiley, S. (2008). Student and stakeholder perceptions of the transition to high school. High Sch. J. 91, 32–42. doi:10.1353/hsj.2008.0003

Stephen, M., and Kelleigh, R. (2014). Supporting Workers in an Indigenous Boarding School Program: An APS Interest Group Volunteer Partnership. Melbourne, VIC: InPsych: The Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society Ltd., 38–39.

Tsey, K., and Every, A. (2000). Evaluating aboriginal empowerment programs: the case of family wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 24, 509–514. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2000.tb00501.x

Turner-Cobb, J. M., Rixon, L., and Jessop, D. S. (2008). A prospective study of diurnal cortisol responses to the social experience of school transition in four-year-old children: anticipation, exposure, and adaptation. Dev. Psychobiol. 50, 377–389. doi:10.1002/dev.20298

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Mac Iver, D., Reuman, D. A., and Midgley, C. (1991). Transitions during early adolescence: changes in children’s domain-specific self-perceptions and general self-esteem across the transition to junior high school. Dev. Psychol. 27, 552. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.4.552

Williams, M. (2002). Reach in – Reach Out – A Journey Starts with a Good Idea. Cairns: The Indigenous Education and Training.

Wilson, B. (2014). A Share in the Future: Review of Indigenous Education in the Northern Territory. Darwin: The Education Business.

Keywords: capacity development, education staff, boarding school, transition, Indigenous, children

Citation: Heyeres M, McCalman J, Bainbridge R and Redman-MacLaren M (2017) Staff Capacity Development Initiatives That Support the Well-being of Indigenous Children in Their Transitions to Boarding Schools: A Systematic Scoping Review. Front. Educ. 2:1. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00001

Received: 18 November 2016; Accepted: 09 January 2017;

Published: 23 January 2017

Edited by:

Ana Lucia Pereira Baccon, Ponta Grossa State University, BrazilReviewed by:

Melissa Christine Davis, Curtin University, AustraliaMercedes Inda-Caro, University of Oviedo, Spain

Copyright: © 2017 Heyeres, McCalman, Bainbridge and Redman-MacLaren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marion Heyeres, bWFyaW9uLmhleWVyZXNAamN1LmVkdS5hdQ==

Marion Heyeres

Marion Heyeres Janya McCalman

Janya McCalman Roxanne Bainbridge

Roxanne Bainbridge Michelle Redman-MacLaren

Michelle Redman-MacLaren