- 1Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, United States

- 2School of Education, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA, United States

- 3Individual, Family, and Community Education Department, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States

- 4Department of Kinesiology and Health Education, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

- 5Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 6Department of Psychological Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

- 7Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

Introduction: The present study investigated the mediating roles of familism values and ethnic identity in longitudinal associations between recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a adolescents' reports of their parents' (i.e., mothers' and fathers') use of social and material rewards and prosocial behaviors.

Methods: Participants included 302 recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a adolescents (M age = 14.5 years at Time 1, range = 13–17 years, 53% male) recruited from Los Angeles and Miami. Participants self-reported on their perceptions of parents' use of social and material rewards (Time 1), familism values (Time 3), ethnic identity (Time 5), and multiple types of prosocial behaviors (Time 6).

Results: Path analyses showed that mothers' use of social rewards was indirectly related (via familism values and ethnic identity) to higher levels of everyday types of helping behaviors seen in youth, whereas mothers' use of material rewards was only directly related to motive-based helping behaviors. In contrast, we found no significant direct or indirect relations from fathers' use of social or material rewards and prosocial behaviors.

Discussion: The discussion describes the parenting and cultural assets that facilitate varied types and motives of prosocial behaviors in recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth. Family-based interventions, prosocial development theories, and future research on this topic can target prosocial parenting practices (e.g., social rewards) and cultural assets (e.g., familism values, ethnic identity) to facilitate helping in youth.

Introduction

Scholars have identified prosocial behavior (i.e., voluntary behaviors intended to benefit others) as a key marker of advanced moral development and positive social adjustment (Carlo, 2014; Maiya et al., 2023). Further, parenting and cultural processes are considered important predictors of prosocial and moral development in U.S. Latino/a youth (Davis et al., 2018; Knight et al., 2016). Moral socialization theorists have posited that parents' use of rewards serves as an important socialization practice that encourages youth's prosocial and moral development (Grusec and Goodnow, 1994). Despite the potential importance of specific parenting practices (relative to general parenting styles; see Carlo et al., 2007), there is limited research examining parents' use of rewards, including social (e.g., praise) and material (e.g., money) rewards, as practices to promote prosocial development in U.S. Latino/a youth.

Focusing on U.S. Latino/a youth's positive developmental outcomes such as prosocial behaviors fosters strengths-based perspectives and counter deficit-based perspectives of ethnic minority development (Smith, 2006). Much of the past research on U.S. Latino/a youth has emphasized negative adjustment outcomes (e.g., delinquency; Rodriguez and Morrobel, 2004); therefore, there are some gaps in our understanding of U.S. Latino/a youth's positive social development. Even less is known about the socialization of prosocial behaviors in recently immigrated Latino/a adolescents, who represent a sizeable proportion of the youth populace in the U.S. (Pew Research Center, 2023a; 2023b) For instance, approximately 20 million Latino/a immigrants lived in the U.S. in 2021, which accounted for 31.8% of the country's total Latino/a population that year (Pew Research Center, 2023a). Further, Latino/as represent the youngest ethnic group in the U.S. with youth and young adults comprising a significant proportion of this population (Pew Research Center, 2023b). Thus, understanding how parents can encourage prosocial behaviors in recent immigrant Latino/a youth is an is an important area of research inquiry. In particular, empirical research is needed to better understand mothers' and fathers' use of rewards and the intervening mechanisms that contribute to recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth's prosocial behaviors.

Based on culture-specific socialization frameworks of prosocial development (Carlo and Conejo, 2019), parents who incentivize helping in their children by providing rewards may encourage greater familism (i.e., cultural values of family support, obligation, and interdependence; Knight et al., 2011) and ethnic identity (i.e., a sense of attachment to one's ethnic group; Umaña-Taylor, 2011). For example, Latino/a parents may encourage familism values in their youth, which can in turn encourage a strong ethnic identity, and subsequently predict greater prosocial behaviors in youth (Armenta et al., 2011). Both familism and ethnic identity have emerged as culturally salient processes through which parents encourage various forms of helping among U.S. Latino/a youth (Knight et al., 2016). Although some work exists on the links between parental use of rewards and youth prosocial behaviors (e.g., Carlo et al., 2022), research is lacking examining mothers' and fathers' use of material and social rewards and prosocial behaviors in recently immigrated U.S. Latino/a youth. Thus, we examined the mediating roles of familism and ethnic identity in longitudinal relations between mothers' and fathers' use of rewards and multiple types of prosocial behaviors among recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth.

Multidimensionality of prosocial behaviors

Prosocial behaviors are considered valuable social behaviors that benefit both the self and society at large (Carlo, 2014). At the individual level, prosocial behaviors support youth's morality, health, and wellbeing; at the societal level, prosocial behaviors are central to civic engagement, neighborhood cohesion, and community building (Davis et al., 2022). As youth transition from middle through late adolescence, they tend to display increasingly sophisticated forms of prosocial behaviors (Padilla-Walker et al., 2018). Indeed, recent conceptualizations suggest that youth may engage in several forms of prosocial behaviors. In one such multidimensional typology of prosocial development, Carlo and Randall (2002) proposed various types of prosocial behavioral tendencies youth may engage in based on situational demands (e.g., comforting someone upset) and motives (e.g., selfless v/s selfish) surrounding helping.

In this study, we focused on five types of prosocial behaviors, namely emotional, compliant, dire, altruistic and public prosocial behaviors (Carlo and Randall, 2002). Emotional prosocial behaviors include helping in emotionally and affective-laden situations. Compliant prosocial behaviors involve helping others in response to a request. Dire prosocial behaviors entail helping in risky, emergency situations. Altruistic prosocial behaviors reflect selfless forms of helping that often come at great cost to the self, whereas public prosocial behaviors reflect selfish forms of helping that are performed in front of an audience for self-gain and social approval (Carlo, 2014). Emotional, compliant, and dire prosocial behaviors represent distinct helping behaviors seen in everyday situations; altruistic and public prosocial behaviors represent distinct motive-driven helping behaviors. Due to our emphasis on specific situations and motives associated with helping, we excluded one type of helping—anonymous prosocial behavior (i.e., helping without the knowledge of the recipient)—from this study. Thus, we focused on parents' use of rewards to encourage emotional, compliant, dire, public, and altruistic prosocial behaviors.

Theoretical frameworks

Scholars have long asserted that learning occurs via reinforcement and reward-based mechanisms (Bandura, 1986). In moral socialization frameworks, parents' use of rewards can facilitate their children's internalization of their parents' prosocial and moral messages (Grusec and Goodnow, 1994). The use of social and material rewards is a common parenting practice to encourage prosocial behaviors and other desirable social outcomes in youth (Carlo et al., 2007). Additionally, culturally-based socialization models of value-based behaviors assert that multiple socialization agents (e.g., mothers and fathers) play a formative role in the development of positive social behaviors (Knight et al., 1993; Knight and Carlo, 2012). Therefore, maternal and paternal rewards can promote cultural processes such as familism and ethnic identity, which in turn facilitate U.S. Latino/a youth's prosocial behaviors. In the ecocultural strengths-based model of U.S. Latino/a prosocial development (Carlo and Conejo, 2019), family processes, particularly parenting can influence cultural strengths, including familism and ethnic identity, and a strong, internalized sense of these cultural assets can consequently impact youth's prosocial behaviors. Overall, there is theoretical support for the examination of parental rewards as correlates of youth prosocial behaviors.

Parents' use of rewards and adolescents' prosocial behaviors

Parents typically utilize two main categories of rewards to encourage prosocial behaviors in their children, namely social and material rewards (Carlo et al., 2007; Eisenberg et al., 2006). Social rewards include the use of praise and positive regard to communicate love and approval, whereas material rewards include the use of tangible, physical resources like money and gifts. Both social and material rewards are typically granted after the child has displayed the helping behavior and indicate parents' recognition of the child's desirable behavior(s). Despite the general efficacy of the use of rewards as a parenting practice, moral socialization scholars have noted that social rewards are conceptually more effective than material rewards in fostering prosociality (Eisenberg et al., 2006; Grusec and Goodnow, 1994).

Moreover, scholars assert that parents' routine use of material rewards may hinder children's developing autonomy as well as contribute toward children's overreliance on extrinsic motives and approval from external authority figures (Henderlong and Lepper, 2002; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Parents' routine use of social rewards, on the other hand, may encourage children's relatedness and competence as well as contribute toward intrinsic motives and internalized processes (e.g., moral reasoning, emotions, values) associated with prosocial actions. As children's morally relevant motives and mechanisms become more sophisticated over the course of adolescence, social (but not material) rewards are likely to promote youth's prosocial behavioral tendencies in the absence of external regulatory forces (Fabes et al., 1989; Grusec and Redler, 1980).

Although there is extensive theoretical work on this topic, there is limited empirical evidence on the connections between parents' use of rewards and their youth's prosocial behaviors. Experimental studies have found that social rewards predicted children's intrinsically motivated prosocial behaviors (Eisenberg and Valiente, 2002; Grusec et al., 2000) like altruistic helping, whereas material rewards predicted children's extrinsically motivated prosocial behaviors like public helping. In one study conducted with a predominantly European American, Midwestern sample, Carlo and colleagues (2007) found that parents' material rewards were directly and negatively associated with adolescents' altruistic forms of helping, but directly and positively associated with public and emotional forms of helping. Although these researchers found some direct links between parents' social rewards and public and altruistic prosocial behaviors, parents' social rewards were largely indirectly associated (via sympathy) with several prosocial behaviors such as helping in emotional, compliant, and dire situations. Similarly, researchers found that parents' use of material rewards was directly positively linked to public and directly negatively linked to altruistic prosocial behaviors in youth samples from middle-class communities in Argentina (Richaud et al., 2013) and low-income communities in the U.S. (Davis and Carlo, 2018). This research emphasized the indirect mechanisms of perspective taking, empathic concern, and prosocial moral reasoning linking social rewards to emotional, compliant, and dire prosocial behaviors (Davis and Carlo, 2018).

Across these studies, parents' use of social rewards seems to enhance multiple types of prosocial behaviors in their youth (e.g., emotional, compliant, dire, and altruistic), whereas parents' use of material rewards appears to undermine altruistic prosocial behaviors. Additionally, social rewards appear to exert indirect predictive effects on prosocial behaviors via internalized mechanisms (e.g., sympathy); material rewards fail to exert similar indirect effects. However, to the best of our knowledge, no empirical studies have examined the ways in which U.S. Latino/a parents, both mothers and fathers, use rewards to facilitate their adolescents' prosocial behaviors.

Mediating roles of familism values and ethnic identity

In addition to investigating how parenting practices such as the use of rewards might be directly impacting adolescents' prosocial development, it is important to consider the underlying mediating mechanisms that can help explain why parents' use of rewards facilitate youth's helping behaviors. As noted above, prior work has largely highlighted socio-cognitive and socio-emotive moral mechanisms such as sympathy, empathic concern, perspective taking, and prosocial moral reasoning that intervene on relations between parents' use of rewards and multiple types of prosocial behaviors (Carlo et al., 2018, 2022; Davis and Carlo, 2018), albeit in samples other than recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a families.

Cultural scholars, however, have underscored the importance of examining culture-specific mechanisms that reflect the distinct cultural values, norms, and goals of a specific cultural group (Super and Harkness, 1986, 2002). Culture-specific theoretical frameworks of socialization in Latino/a families present several culturally relevant processes such as family-oriented values (e.g., familism) and cultural identity (e.g., ethnic identity) that undergird connections between parenting and value-based behaviors (Knight et al., 1993; Carlo and Conejo, 2019). Familism refers to a set of cultural values centered around familial solidarity, interdependence, and role flexibility for one's kinship network (Calzada et al., 2013; Sabogal et al., 1987); ethnic identity refers to a dynamic sense of peoplehood within one's culture centered around ethnic knowledge, evaluations, behaviors, and commitment (Pabón Gautier, 2016; Phinney and Ong, 2007).

In accord with the ecocultural strengths-based model of prosocial development (Carlo and Conejo, 2019), parenting can influence cultural strengths, including familism and ethnic identity, and a strong, internalized sense of these cultural assets can consequently impact youth's prosocial behaviors. These culture-specific conceptions of prosocial development emphasize the central roles played by mothers' and fathers' use of rewards alongside cultural processes such as familism and ethnic identity in predicting multiple types of prosocial behaviors among U.S. Latino/a adolescents. Drawing upon cultural perspectives specific to U.S. Latino/a families, parents may use rewards to express approval, support, and warmth toward their youth. Such close parent-child relationships can promote family-oriented cultural values like familism.

In particular, parents' use of social rewards may augment their expressions of warmth, support and general involvement, which not only leads to strengthened parent-child relationships, but also positive family orientations and relationships. Furthermore, parents tend to deliver social rewards within positive emotional environments, which helps adolescents to better focus their attention on the cultural and moral messages shared by parents. There is considerable research evidence linking parental involvement to familism and related cultural values and orientations in U.S. Latino/a samples (Knight et al., 2011). In other scholarship on maternal involvement and cultural values conducted with recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth, researchers suggest that maternal involvement is protective for youth and predicts their later familism and collectivistic cultural orientations (Davis et al., 2018, 2021; see Cahill et al., 2021). Thus, we expected that parents' use of rewards, especially social rewards, would predict greater endorsement of familism among recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth.

Recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth's strong sense of familism can be internalized and contribute toward the development of a secure ethnic identity. Parents' cultural transmission of traditional cultural values such as familism can support their youth's knowledge, insights, and experiences associated with their ethnic affiliation. U.S. Latino/a adolescents' familism values are, therefore, closely tied to the exploration of and commitment to their ethnic identity (Knight et al., 2016). Indeed, there is well-documented evidence, suggesting longitudinal positive relations from familism to ethnic identity in Latino/a samples (Armenta et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2016; Streit et al., 2018).

In turn, familism and ethnic identity are cultural processes that can help elucidate individual differences in recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a adolescents' prosocial behaviors. Since familism values encourage youth to orient themselves toward others' needs and emphasize family assistance behaviors (e.g., household chores), this creates opportunities for youth to practice prosocial actions (Carlo, 2014). As adolescents become increasingly attuned and empathetic toward others, they may be especially inclined to engage in prosocial behaviors. Extant research indicates that familism is linked directly (Armenta et al., 2011; Calderón-Tena et al., 2011) and indirectly (Knight et al., 2015) to higher levels of emotional, compliant, dire, and public prosocial behaviors, but not altruistic prosocial behaviors among U.S. Latino/a adolescents.

Additionally, recent immigrant Latino/a youth's ethnic identity may encourage positive social behaviors consistent with their cultural niche (Knight et al., 1993, 2016). Specifically, youth with a strong sense of their own ethnic identity may engage in prosocial behaviors that align with their ethnic group's collectivistic norms and goals. However, empirical evidence supporting associations between ethnic identity and prosocial behaviors is mixed, and limited studies investigate these connections longitudinally (see Knight et al., 2016 for an exception). For instance, Armenta et al. (2011) found concurrent, positive associations between U.S. Mexican youth's ethnic identity and emotional and compliant prosocial behaviors; similarly, Streit et al. (2018) found cross-sectional, positive links between U.S. Mexican young adults' ethnic identity and emotional, compliant, and dire prosocial behaviors. In contrast, some researchers have found no significant relations between ethnic identity and prosocial behaviors in U.S. Latino/a youth (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2007). The relations between adolescents' ethnic identity and public and altruistic prosocial behaviors are even less clear. Thus, further research is necessary to investigate the relationships between ethnic identity and specific types of prosocial behaviors. Taken together, familism and ethnic identity may act as culture-specific mediators in the associations between recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a parents' use of social and material rewards and their youth's prosocial behaviors.

Study hypotheses

Building primarily on theoretical frameworks and limited empirical research, the primary goal of this study was to investigate longitudinal direct and indirect relations between parents' use of material and social rewards and multiple types of prosocial behaviors via both familism and ethnic identity in recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth. In order to distinguish between mothers' vs. fathers' effects, we tested two separate models with youth's perceptions of their mothers' material and social rewards (model 1) and fathers' material and social rewards (model 2), respectively. Specifically, we hypothesized that parents' (mothers' and fathers') use of material rewards would be directly, negatively associated with adolescents' later altruistic prosocial behaviors and positively associated with adolescents' later public prosocial behaviors; parents' (mothers' and fathers') use of social rewards would be directly, positively associated with adolescents' later altruistic, emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial behaviors. We also hypothesized that parents' (mothers' and fathers') social and material rewards would be positively related to youth's familism over time; in turn, youth's familism would be positively related to their own ethnic identity, and youth's ethnic identity would be subsequently positively associated with all their prosocial behaviors, except public prosocial behaviors. Finally, given the possibility of gendered parental socialization processes of traditional cultural values, norms, and prosocial behaviors with Latinas often displaying higher levels of familism and selfless and emotional forms of prosocial behaviors compared to Latinos (Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004; Sanchez et al., 2017; Streit et al., 2020a,b), we explored gender-moderated effects in associations among parents' use of material and social rewards, familism, ethnic identity, and multiples types of prosocial behaviors among recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants of this study included 302 (53.3% male; M age = 14.51 years at Time 1, range = 13–17 years) recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a adolescents. The sample was recruited from two sites: Los Angeles (n = 150) and Miami (n = 152). Participants from Los Angeles primarily originated from Mexico (70%), El Salvador (9%), Guatemala (6%), and other countries (15%); participants from Miami mainly originated from Cuba (61%), Dominican Republic (8%), Nicaragua (7%), Colombia (6%), Honduras (6%), and other countries (12%). The majority of adolescents and parents immigrated to the U.S. together (67% of Los Angeles families; 83% of Miami families). Participating youth from Miami had lived in the U.S. for a median of 1 year (interquartile range = 0–3 years), whereas youth from Los Angeles had lived in the U.S. for a median of 3 years (interquartile range = 1–4 years). Primary caregivers (75% mothers) reported on their years of education completed (Los Angeles = 9 years; Miami = 11 years) and family income ( ≤ $44,999 for 93% of Los Angeles sample; ≤ $29,999 for 92% of Miami sample). Most adolescents were from two-parent families (71%).

Procedure

The current study was conducted using data from the Construyendo Oportunidades Para los Adolecentes Latinos (COPAL) project (Soto et al., 2022). This project was designed with the objective of collecting longitudinal data on cultural change, family relationships, and health behaviors among recent immigrant Latino/a youth (Forster et al., 2015). Adolescents and their primary parents were assessed every 6 months for a three-year period. For the current study, we only used adolescent-reported data from Time 1, Time 3, Time 5, and Time 6, that is baseline, 1-year post-baseline, 2 years post-baseline, and 2.5 years post-baseline, respectively.

Data were collected from 13 schools in Los Angeles County and 10 schools in Miami-Dade County. Participants from schools with a 75% or greater representation of Latino/a students were selected because recent Latino/a immigrants are likely to reside in ethnic enclaves (Portes and Runbaut, 2006). Participants were recruited from English for Speakers of Other Languages classes and assistance from school officials. Latino/a adolescents met the eligibility criteria to participate in this study if they had lived in the U.S. for 5 years or fewer, were enrolled in the ninth grade at baseline, and their parent was willing to participate in the study. Data were collected at schools, research centers, and other locations convenient for families. Adolescents and their parents were tested in different rooms to ensure privacy. Audio computer-assisted software was used to administer surveys, so that no prior computer experience was required. The survey was available in English and Spanish. The survey measures were translated and back-translated by bicultural staff in both cities. Most parents (98%) and adolescents (84%) completed the survey in Spanish at baseline (Time 1). In return for participation in this project, parents received monetary incentives and adolescents received movie tickets. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Southern California and the University of Miami approved this study.

Measures

Parents' use of social and material rewards

At Time 1, adolescents reported on their perceptions of their mothers' and fathers' use of rewards using the Parenting Practices Scale (Gorman-Smith et al., 1996). Although the Parenting Practices Scale was initially composed of two subscales, parental involvement (15 items) and positive parenting (9 items), on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Always) (Gorman-Smith et al., 1996), we selected items from these subscales corresponding to parents' (i.e., mothers and fathers) use of social rewards (5 items, “When you have done something that your parents like or approve of, how often does your mother/father say something nice about it?”) and material rewards (3 items; “When you have done something that your parents like or approve of, how often does your mother/father give you some reward for it like a present, extra allowance, or something special to eat”), respectively. Initial confirmatory factor analyses and Cronbach's alphas (α = 0.75–0.90) supported the newly created subscales for parents' use of social and material rewards for mothers and fathers. Next, we computed two corresponding observed variables with higher mean scores corresponding to higher levels of parents' use of social and material rewards, respectively.

Familism values

At Time 3, adolescents completed an attitudinal familism scale (Lugo Steidel and Contreras, 2003). Adolescents reported on their own family-oriented cultural values such as familial support, familial interconnectedness, familial honor, and subjugation of self on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (Strongly Disagree) to 4 (Strongly Agree). A sample item from this measure includes “A person should help his or her elderly parents in times of need, for example, help financially or share a house.” A mean composite familism values score was calculated with higher scores representing greater endorsement of familism values by youth. Previous researchers have shown construct validity for the total familism score in Latino/a youth samples (Davis et al., 2021), and we found acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.92) for this composite familism variable in the current sample.

Ethnic identity

At Time 4, adolescents completed the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure, which is a 12-item scale that measures ethnic identity (Roberts et al., 1999). Adolescents reported on their exploration and affirmation of their ethnic identity on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). The ethnic exploration subscale was used to measure adolescents' exploration of their ethnic heritage (5 items; “I am active in organizations or social groups that include mostly members of my own ethnic group”; α = 0.85). The ethnic affirmation subscale was used to measure adolescents' commitment to their ethnic identity (7 items; “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means for me”; α = 0.92). Given the theoretical and empirical interrelations between the ethnic identity subscales, we created a manifest ethnic identity score with higher values indicating stronger ethnic identity in youth. The use of this global ethnic identity variable is well-validated in past research with Latino/a youth samples (Phinney and Ong, 2007). This measure also demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.91) in the current sample.

Prosocial behaviors. At Time 1 and Time 6, adolescents completed the Prosocial Tendencies Measure, which is a 21-item measure used to assess multiple types of prosocial behaviors in adolescents (Carlo and Randall, 2002). Participants rated their tendencies to engage in prosocial behaviors on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Does not describe me at all) to 5 (Describes me greatly) for emotional, compliant, dire, public, and altruistic prosocial behaviors. The emotional subscale was used to measure adolescents' helping behaviors in emotionally evocative situations (4 items; “Emotional situations make me want to help needy others”; Time 1 α = 0.76; Time 6 α = 0.85). The compliant subscale was used to assess adolescents' prosocial behavior in response to a request for help (2 items; “When people ask me to help them, I help them as quickly as I can”; Time 1 α = 0.53; Time 6 α = 0.73). The dire subscale was used to measure adolescents' helping in emergency or crisis situations (3 items; “I like to help people who are in a real crisis or need”; Time 1 α = 0.77; Time 6 α = 0.85). Finally, the public subscale was used to study adolescents' selfishly motivated prosocial behavior (2 items; “I am best at helping others when everyone is watching”; Time 1 α = 0.84; Time 6 α = 0.89), whereas altruistic subscale was used to study adolescents' selflessly motivated prosocial behavior (3 reverse-coded items; “I believe I should receive more recognition for the time and energy I spend helping others”; Time 1 α = 0.69; Time 6 α = 0.89). The anonymous prosocial behavior subscale was excluded from the current study. Separate mean scores were computed for the five subscales; higher mean scores indicated greater likelihood of engaging in corresponding types of prosocial behaviors (i.e., emotional, compliant, dire, public, and altruistic prosocial behaviors). Prior scholarship has documented the construct and convergent validity as well as measurement equivalence for these prosocial behavior types (with European American adolescents; Carlo et al., 2010; see also Carlo and Maiya, 2019); reliabilities (Cronbach's alphas) consistent with past research were demonstrated in this sample.

Analytic plan

Path analyses were conducted using maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus, version 7 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017) to examine the direct and indirect associations between maternal and paternal use of social and material rewards at Time 1 and prosocial behaviors at Time 6 via familism values at Time 3 and ethnic identity at Time 5. To avoid multicollinearity issues, we conducted two path models (the first model examined maternal rewards and the second model examined paternal rewards; see Figures 1, 2, respectively). The first model included maternal social and material rewards as exogenous variables, which were allowed to predict familism values at Time 3, ethnic identity at Time 5, and well as each of the prosocial behaviors at Time 6. Familism values and ethnic identity were also set to predict the prosocial behavior outcomes, and familism values were set to predict ethnic identity. We controlled for site (Miami vs. Los Angeles) and for Time 1 levels of all mediating and outcome variables. The predictor variables were allowed to correlate, initial levels of familism values and ethnic identity were allowed to correlate, and the outcomes variables were allowed to correlate. Site was also correlated with the exogenous variables in the model. The second model was set up identically to the first model, except with paternal rewards instead of maternal rewards. Model fit is considered good in path analysis if the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) is 0.95 or greater (fit is adequate at 0.90 or greater), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is ≤ 0.06 (values of 0.08 or less indicate adequate fit; Byrne, 2010; Hu and Bentler, 1999).

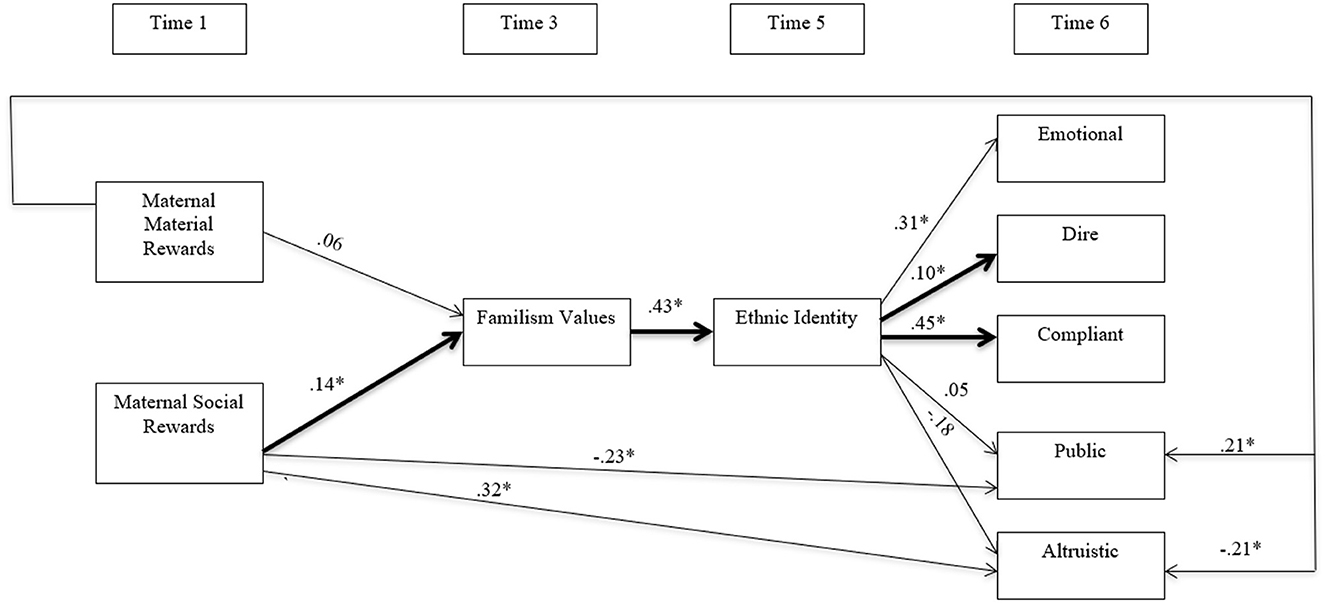

Figure 1. Standardized coefficients for the associations between maternal rewards, familism values, ethnic identity, and prosocial behaviors. All direct paths were included, but only significant direct paths from rewards to prosocial behaviors are depicted. *p < 0.05. Significant indirect effects are bolded.

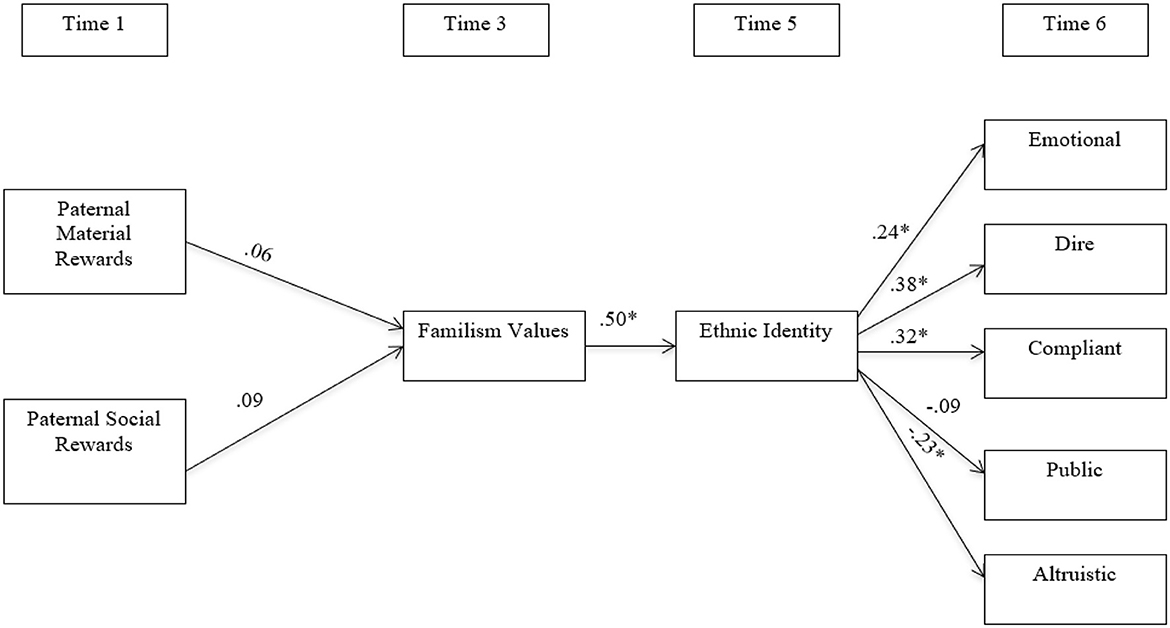

Figure 2. Standardized coefficients for the associations between paternal rewards, familism values, ethnic identity, and prosocial behaviors. All direct paths were included, but only significant direct paths from rewards to prosocial behaviors are depicted. *p < 0.05. Significant indirect effects are bolded.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Of the 302 participants who initially participated at Time 1, 278 (92% of the original sample) participated at Time 2, and 256 (85% of the original sample) participated from Time 3 to Time 6 (see Davis et al., 2021). Attrition analyses yielded no significant differences by missingness in parents' use of rewards, ethnic identity, familism, or prosocial behaviors from Time 1 to Time 3, Time 5, and Time 6.

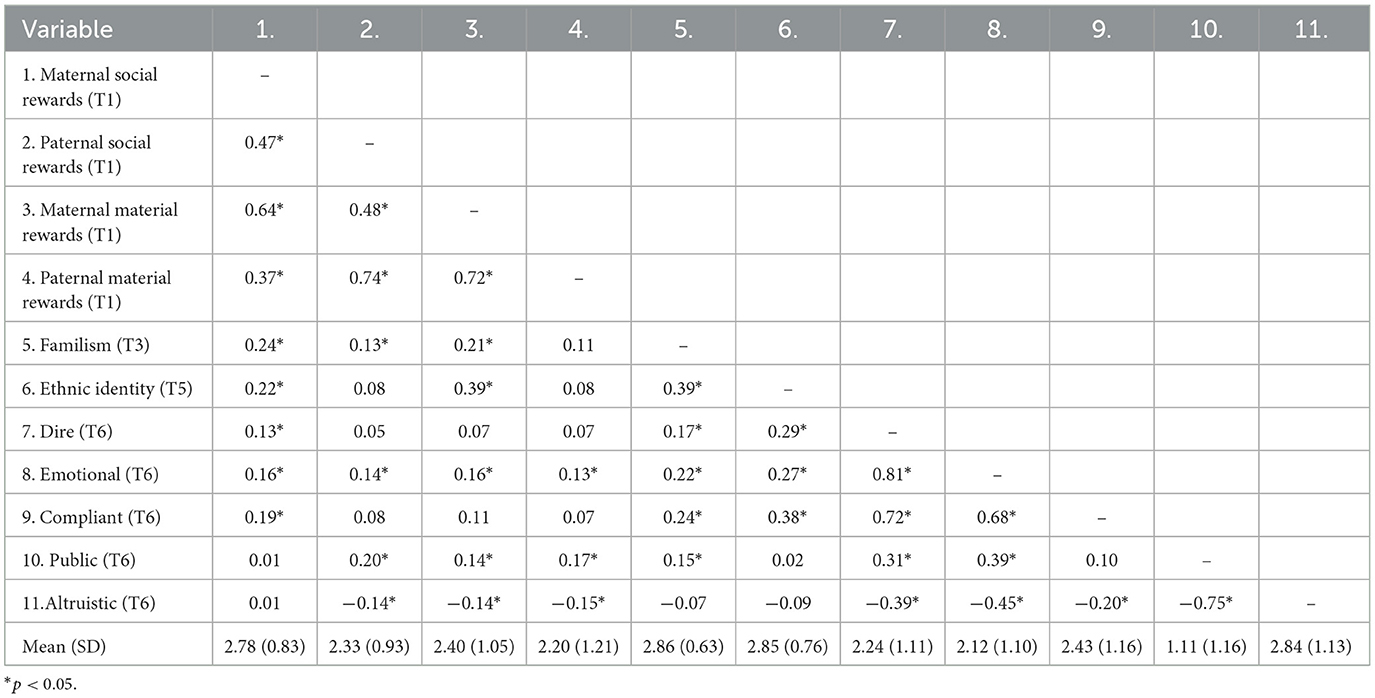

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the main study variables were estimated in SPSS. The data were approximately normally distributed. All means with standard deviations and bivariate correlations are reported in Table 1. Mothers' social and material rewards (Time 1) were positively correlated with adolescents' familism (Time 3) and ethnic identity (Time 5); fathers' social rewards (Time 1) were positively correlated with adolescents' familism (Time 3) with no significant correlations between fathers' social rewards to ethnic identity or fathers' material rewards to ethnic identity or familism values. Mothers' social rewards (Time 1) were positively related to emotional, compliant, and dire prosocial behaviors (Time 6), and their material rewards (Time 1) were positively related to emotional and public prosocial behaviors but negatively related to adolescents' later altruistic prosocial behaviors (Time 6). Fathers' use of social and material rewards was positively linked to emotional and public prosocial behaviors but negatively linked to adolescents' later altruistic prosocial behaviors.

Table 1. Intercorrelations among parents' use of material and social rewards, familism, ethnic identity, and prosocial behaviors.

Path analysis

Using maximum likelihood estimation, two separate path models were specified with one model for maternal rewards and one model for paternal rewards. In the path models, parents' (mothers/fathers) use of social rewards and material rewards were specified as correlated predictors, familism was the first-order mediator, ethnic identity was the second-order mediator, and five types of prosocial behaviors were correlated outcomes (site and Time 1 levels of all variables were entered as covariates).

Model fit for the maternal rewards model (see Figure 1) was good: = 7.86, p = 0.10; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.06. The results demonstrated that maternal material rewards were not associated with familism values or ethnic identity, but were directly, positively associated with public and directly, negatively associated with altruistic prosocial behaviors. Maternal social rewards were positively associated with familism values and were directly, positively associated with altruistic prosocial behaviors and directly, negatively associated with public prosocial behaviors. Familism values were positively associated with ethnic identity, and ethnic identity was positively associated with emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial behaviors.

Model fit for the paternal rewards model (see Figure 2) was acceptable: = 41.40, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.08. The results demonstrated that paternal rewards were not associated with familism values or ethnic identity, and there were no direct links between rewards and prosocial behaviors. Familism values were positively associated with ethnic identity. Ethnic identity was positively associated with emotional, dire, and compliant prosocial behaviors and negatively associated with altruistic prosocial behaviors.

We also estimated each model controlling for initial levels of each of the study variables. For the maternal rewards model, the only differences when estimated ran the model controlling for initial levels of all variables at Time 1 were the direct paths from material rewards to prosocial behaviors were no longer significant. Additionally, the paths from social rewards to public prosocial behaviors and familism values were no longer significant. For the paternal rewards model, the path from ethnic identity to altruistic prosocial behaviors was no longer significant. Because the main model findings are similar, we present the model without controlling for Time 1 variables in the figures.

To examine gender differences in the models, each path was constrained to be equal across the two groups (adolescent males and females). A chi-square difference test was conducted to examine whether the constrained and unconstrained models were significantly different. The results for the maternal rewards model demonstrated that the constrained model [CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00; = 31.92, p = 0.52] and the unconstrained model [CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.04; = 11.67, p = 0.29] were not significantly different [ = 22.27, p = 0.62]. For the paternal rewards model, the results demonstrated that the constrained model [CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.03; = 36.13, p = 0.32] and the unconstrained model [CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.06; = 11.67, p = 0.17] were not significantly different [ = 24.6, p = 0.49]. Therefore, the results are reported for the whole sample for both models.

Mediation analyses

Indirect effects were examined in Mplus using maximum likelihood estimation. For the maternal rewards model, the results demonstrated two significant indirect effects: social rewards to dire prosocial behaviors via familism values and ethnic identity (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = 0.05) and social rewards to compliant prosocial behaviors via familism values and ethnic identity (β = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = 0.05). For the paternal rewards model, there were no significant indirect effects.

Discussion

Overall, we found supportive evidence that parents' use of rewards represents a central prosocial parenting practice linked to recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth's familism values, ethnic identity, and prosocial behaviors. More specifically, mothers' use of material rewards encouraged higher selfish forms of helping (i.e., public) and lower selfless forms of helping (i.e., altruistic) directly, but there were no significant indirect relations. In contrast, mothers' use of social rewards was not only directly related to greater altruistic (or selfless) helping and lower public (or selfish) helping, but was also indirectly related (via familism and ethnic identity) to everyday helping behaviors (e.g., compliant and dire). Interestingly, fathers' use of material or social rewards was unrelated to any of the helping behaviors. This set of findings is largely consistent with cultural-strength based models (Carlo and Conejo, 2019; Knight et al., 1993) that integrate culture-group (e.g., ethnic identity, familism) and non-culture group (e.g., parenting) specific mechanisms in better accounting for U.S. Latino/a youth prosocial and moral development. These findings also extend socialization, socio-cognitive, and motivational perspectives of prosocial development (Eisenberg et al., 2006; Grusec and Goodnow, 1994; Henderlong and Lepper, 2002) by considering multicultural processes and multidimensional conceptualizations of prosocial behaviors (see Carlo and Padilla-Walker, 2020).

In support of our direct relations hypothesis, mothers' use of social rewards encouraged altruistic helping but discouraged public helping in recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a adolescents, while mothers' use of material rewards was inversely related to these motive-based forms of helping. These findings imply that maternal social rewards support youth's intrinsic motivation to act prosocially, and this intrinsic motivation is reflected in the selflessly driven, altruistic prosocial behaviors instead of selfishly driven, public prosocial behaviors displayed by youth over time. Maternal material rewards, on the other hand, appeared to thwart youth's intrinsic motivation, making them less likely to engage in altruistic helping. In line with our hypothesis, maternal material rewards also seemed to promote youth's extrinsic motivation (e.g., to gain money and approval), making them more likely to engage in later public helping. Comparing social and material rewards, social rewards might be more effective as a prosocial parenting practice in promoting intrinsically motivated prosocial tendencies (i.e., altruistic helping). This pattern of findings is generally consistent with prior, albeit limited, research on social and material rewards and motive-based forms of helping conducted with cultural samples other than recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth (Davis and Carlo, 2018; Richaud et al., 2013). Our findings extend this previous research on mothers' use of social and material rewards and prosocial behaviors and help generalize this work to recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth.

Importantly, we also found partial support for our indirect relations hypothesis with both familism values and ethnic identity serving as culturally salient processes connecting immigrant U.S. Latino/a youth's perceptions of maternal social rewards to some types of their prosocial behaviors. Mothers' social rewards were related to higher levels of familism values experienced by youth. In turn, familism values predicted a stronger sense of ethnic identity, which was subsequently linked to youth's greater compliant, dire, and emotional forms of helping (only indirect effects to compliant and dire prosocial behaviors were significant). Because compliant, dire, and emotional behaviors represent everyday helping behaviors displayed typically in family settings (Carlo, 2014; Maiya et al., 2023), family-oriented cultural values such as familism (and the internalization of these values to youth's ethnic identity) might be especially relevant for these forms of helping. Further, social rewards are often shared in positive social contexts, which can help adolescents to better reflect upon their mothers' messages about cultural values, identity, and prosocial behaviors. This set of findings is generally in accord with extant research literature on mothers' social rewards and prosocial behaviors (see Carlo et al., 2007). We also present the first evidence for familism and ethnic identity as mediating mechanisms by expanding our investigation to cultural assets and strengths instead of the moral developmental mechanisms addressed in past research (Davis and Carlo, 2018; Carlo et al., 2018).

In the maternal and paternal rewards models, youth's familism was associated with greater ethnic identity, and ethnic identity was associated with higher emotional, compliant, and dire helping. Ethnic identity was significantly associated with youth's lower altruistic helping only in the paternal rewards and prosocial behaviors model. Prior work has highlighted ethnic identity as a protective mechanism for U.S. Latinx youth and young adults (Maiya et al., 2023), which is linked to some (e.g., emotional, compliant, dire; see Streit et al., 2018) but not all forms of prosocial behaviors (e.g., altruistic). It is likely that the mixed findings connecting ethnic identity with global prosocial behaviors in the extant literature are due to the multidimensionality of prosocial behaviors. For instance, a strong ethnic identity may discourage high-cost, low-reward prosocial behaviors and emphasize in-group helping; different intervening mechanisms like prosocial moral reasoning, perspective taking, and self-regulation may be relevant for altruistic prosocial behaviors (Carlo, 2014). Nevertheless, ethnic identity continued to serve as an important cultural asset, which encouraged several, everyday forms of prosocial behaviors like comforting someone upset, complying with a request, and helping during emergencies.

Surprisingly, we found several null effects in the paternal use of rewards and youth's prosocial behaviors model, such that fathers' use of material or social rewards did not predict youth's later familism or prosocial behaviors. In other words, there were no significant direct or indirect relations (via familism and ethnic identity) from youth perceptions of their fathers' use of rewards to youth's prosocial behaviors. This finding is inconsistent with prior scholarship which indicates that U.S. Latino/a fathers serve as central socialization agents of their children's prosociality (e.g., paternal involvement and acceptance; Davis et al., 2021; Streit et al., 2018). However, given that this is to our knowledge the first study on Latino fathers' use of rewards, it is plausible that fathers utilize different prosocial parenting strategies such as experiential learning (e.g., hands-on volunteering) and moral conversations (e.g., discussing moral themes and values) instead of using social and material rewards. Additionally, fathers might encourage forms of prosocial behaviors (e.g., high-risk forms of helping, instrumental) that were not assessed in the present study. Recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a fathers and their parenting practices may also be different (compared to other U.S. samples) because of their high work demands and low work-life balance to support their families. Future research examining the links between Latino fathers' prosocial parenting practices and other specific forms of prosocial behaviors would be desirable to further examine this topic.

It is worth noting that associations among parents' use of rewards, familism, ethnic identity, and multiple types of prosocial behaviors operated similarly across recent immigrant adolescent females and males. Although there is preliminary research evidence on gender differences in associations between parenting and prosocial behaviors among U.S. Latino/a youth (e.g., Sanchez et al., 2017; Streit et al., 2020a,b), gender-moderated effect sizes tend to be generally small in the literature on the socialization of prosocial behaviors. In fact, scholars have noted that gender differences in prosocial development might be an artifact of the study design (e.g., treatment effects in experiments; Espinosa and Kovárík, 2015) or somewhat overstated. In the context of our study, recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a parents may encourage a range of prosocial behaviors in both their male and female youth as an extension of behaviors consistent with their core cultural values (e.g., familism) and as a means to socially integrate with peers in a new cultural setting.

Limitations and future directions

The present findings should be considered in light of the study limitations. First, the generalizability of our study findings is restricted to recent immigrant U.S. Latino/a immigrant adolescents (time in the U.S. = 1–5 years), primarily of Mexican- and Cuban-origins and residing in urban cities. Owing to within-cultural variability patterns, future research on adolescent prosocial development in diverse U.S. Latino/a samples should consider making explicit comparisons by time lived in the U.S. (e.g., 1 vs. 7 years), country-of-origin (e.g., Mexico vs. Central America), and the receiving community context (e.g., urban vs. rural). Second, we relied on a single-reporter and questionnaire assessment procedure in which adolescents were asked to recall their parents' past behaviors, which presents shared method variance and accuracy-related concerns. Future studies using multiple assessment methods (e.g., multiple reporters, observational measures) can address these concerns by including parent reports in surveys and parent-adolescent interaction in a real-time observational task. And third, although the study utilized a longitudinal study design, strong inferences regarding causation and direction of effects must be tempered, particularly because we presented our findings with and without controlling for initial levels of all study variables. To address this issue, researchers should conduct research using study designs (e.g., experimental, ecological momentary study designs) better suited to address concerns about directionality inferences in future research on this topic.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, the present study makes important contributions to research, theory, and practice on prosocial development in immigrant U.S. Latino/a adolescent populations. Specifically, we found that mothers' social rewards were directly and indirectly associated (via familism values and ethnic identity) with greater everyday helping behaviors (i.e., emotional, compliant, dire); mothers' material rewards were only directly related to motive-based helping behaviors (i.e., public and altruistic). These study findings advance the scant research literature on prosocial development in recent U.S. Latinx immigrant youth by presenting nuanced longitudinal links between parents' use of social and material rewards, and youth's multiple types of prosocial behaviors. In addition to moral socialization perspectives, our findings extend culturally-grounded theoretical frameworks of prosocial development (Carlo and Conejo, 2019; Carlo and Padilla-Walker, 2020) by highlighting the mediating roles of culturally relevant processes such as ethnic identity and familism values for U.S Latinx adolescents. Finally, family-based interventions (e.g., parent education programs) may benefit from targeting prosocial parenting practices (e.g., social rewards) and cultural assets (e.g., ethnic identity, familism values) in order to facilitate a range of helping behaviors in their youth.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because this manuscript's data will not be deposited. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Seth Schwartz, c2V0aC5zY2h3YXJ0ekBhdXN0aW4udXRleGFzLmVkdQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Miami and the University of Southern California. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AD: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SS: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. JU: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. BZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. LB-G: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. DS: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. EL-B: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research presented here was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA026594 (Seth Schwartz and Jennifer Unger, Principal Investigators).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Armenta, B. E., Knight, G. P., Carlo, G., and Jacobson, R. P. (2011). The relation between ethnic group attachment and prosocial tendencies: The mediating role of cultural values. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 41, 107–115. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.742

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Hoboken: Prentice Hall.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Cahill, K. M., Updegraff, K. A., Causadias, J. M., and Korous, K. M. (2021). Familism values and adjustment among Hispanic/Latino individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 147, 947–985. doi: 10.1037/bul0000336

Calderón-Tena, C. O., Knight, G. P., and Carlo, G. (2011). The socialization of prosocial behavioral tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: the role of familism values. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 17, 98–106. doi: 10.1037/a0021825

Calzada, E. J., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., and Yoshikawa, H. (2013). Familismo in Mexican and Dominican Families from low-income, urban communities. J. Fam. Issues 34, 1696–1724. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12460218

Carlo, G. (2014). “The development and correlates of prosocial moral behaviors,” in Handbook of Moral Development, eds. M. Killen and J. G. Smetana (London: Psychology Press), 208–234.

Carlo, G., and Conejo, L. D. (2019). “Traditional and culture-specific parenting of prosociality in U.S. Latino/as,” in Oxford Handbook of Parenting and Moral Development, eds. D. Laible, L. Padilla-Walker and G. Carlo (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 247–266.

Carlo, G., Knight, G., McGinley, M., Zamboanga, B., and Jarvis, L. (2010). The multidimensionality of prosocial behaviors and evidence of measurement equivalence in Mexican American and European American early adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 20, 334–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00637.x

Carlo, G., and Maiya, S. (2019). “Methodological issues in cross-cultural research on prosocial and moral development,” in Developmental Research: A Guide for Conducting Research Across the Life Span, eds. N. A. Jones, M. Platt, K. D. Mize, and J. Hardin (London: Routledge/Taylor-Francis Publishers), 171–188.

Carlo, G., McGinley, M., Hayes, R., Batenhorst, C., and Wilkinson, J. (2007). Parenting styles or practices? Parenting, sympathy, and prosocial behaviors among adolescents. J. Genetic Psychol. 168, 147–176. doi: 10.3200/GNTP.168.2.147-176

Carlo, G., and Padilla-Walker, L. (2020). Adolescents' prosocial behaviors through a multidimensional and multicultural lens. Child Dev. Perspect. 14, 265–272. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12391

Carlo, G., and Randall, B. A. (2002). The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 31, 31–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1014033032440

Carlo, G., Samper, P., Malonda, E., Mestre, A. L., Tur-Porcar, A. M., and Mestre, M. V. (2022). Longitudinal paths between parents' use of rewards and young adolescents' moral traits and prosocial behaviors. J. Adolesc. 94, 1096–1107. doi: 10.1002/jad.12086

Carlo, G., Samper, P., Malonda, E., Tur-Porcar, A. M., and Davis, A. (2018). The effects of perceptions of parents' use of social and material rewards on prosocial behaviors in Spanish and US youth. J. Early Adolesc. 38, 265–287. doi: 10.1177/0272431616665210

Davis, A. N., and Carlo, G. (2018). The roles of parenting practices, sociocognitive/emotive traits, and prosocial behaviors in low-income adolescents. J. Adolesc. 62, 140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.11.011

Davis, A. N., Carlo, G., Maiya, S., Schwartz, S. J., Szapocznik, J., and Des Rosiers, S. (2021). A longitudinal study of paternal and maternal involvement and neighborhood risk on recent immigrant Latino/a youth prosocial behaviors. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 177, 13–30. doi: 10.1002/cad.20417

Davis, A. N., Carlo, G., Streit, C., Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., et al. (2018). Longitudinal associations between maternal involvement, cultural orientations, and prosocial behaviors among recent immigrant Latino adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 47, 460–472. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0792-3

Davis, A. N., Clark, E. S., Streit, C., Kelly, R. J., and Lardier Jr, D. T. (2022). The buffering role of community self-efficacy in the links between family economic stress and young adults' prosocial behaviors and civic engagement. J. Genet. Psychol. 183, 527–536. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2022.2094212

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., and Spinrad, T. L. (2006). “Prosocial development,” in Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3. Social, Emotional, and Personality Development, eds. N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, and R. M. Lerner (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 646–718.

Eisenberg, N., and Valiente, C. (2002). “Parenting and children's prosocial and moral development,” in Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 5. Practical Issues in Parenting, 2nd Edn, ed. M. H. Bornstein (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 111–142.

Espinosa, M. P., and Kovárík, J. (2015). Prosocial behavior and gender. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 9:88. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00088

Fabes, R. A., Fultz, J., Eisenberg, N., May-Plumlee, T., and Christopher, F. S. (1989). Effects of rewards on children's prosocial motivation: a socialization study. Dev. Psychol. 25, 509–515. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.4.509

Forster, M., Grigsby, T., Soto, D. W., Schwartz, S. J., and Unger, J. B. (2015). The role of bicultural stress and perceived context of reception in the expression of aggression and rule breaking behaviors among recent-immigrant Hispanic youth. J. Interpers. Violence 30, 1807–1827. doi: 10.1177/0886260514549052

Gorman-Smith, D., Tolan, P. H., Zelli, A., and Huesmann, L. R. (1996). The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. J. Family Psychol. 10, 115–129. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115

Grusec, J. E., and Goodnow, J. J. (1994). Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: a reconceptualization of current points of view. Dev. Psychol. 30, 4–19. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4

Grusec, J. E., Goodnow, J. J., and Kuczynski, L. (2000). New directions in analyses of parenting contributions to children's acquisition of values. Child Dev. 71, 205–211. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00135

Grusec, J. E., and Redler, E. (1980). Attribution, reinforcement, and altruism: A developmental analysis. Dev. Psychol. 16, 525–534. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.16.5.525

Henderlong, J., and Lepper, M. R. (2002). The effects of praise on children's intrinsic motivation: a review and synthesis. Psychol. Bullet. 128, 774–795. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.774

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Knight, G. P., Berkel, C., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Gonzales, N. A., Ettekal, I., Jaconis, M., et al. (2011). The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. J. Marriage Family 73, 913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x

Knight, G. P., Bernal, M. E., Garza, C. A., and Cota, M. K. (1993). “A social cognitive model of ethnic identity and ethnically-based behaviors,” in Ethnic identity: Formation and Transmission among Hispanics and Other Minorities (New York: State University of New York Press), 213–234.

Knight, G. P., and Carlo, G. (2012). Prosocial development among Mexican American youth. Child Dev. Perspect. 6, 258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00233.x

Knight, G. P., Carlo, G., Basilio, C. D., and Jacobson, R. P. (2015). Familism values, perspective taking, and prosocial moral reasoning: predicting prosocial tendencies among Mexican American adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 25, 717–727. doi: 10.1111/jora.12164

Knight, G. P., Carlo, G., Mahrer, N. E., and Davis, A. N. (2016). The socialization of culturally related values and prosocial tendencies among Mexican-American adolescents. Child Dev. 87, 1758–1771. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12634

Lugo Steidel, A. G., and Contreras, J. M. (2003). A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 25, 312–330. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256912

Maiya, S., Gülseven, Z., Killoren, S. E., Carlo, G., and Streit, C. (2023). The intervening role of anxiety symptoms in associations between Self-Regulation and prosocial behaviors in US Latino/a college students. J.Am. College Health 71, 584–592. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1899187

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user's guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Pabón Gautier, M. C. (2016). Ethnic identity and Latino youth: the current state of the research. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 1, 329–340. doi: 10.1007/s40894-016-0034-z

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Carlo, G., and Memmott-Elison, M. K. (2018). Longitudinal change in adolescents' prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family. J. Res. Adolesc. 28, 698–710. doi: 10.1111/jora.12362

Pew Research Center (2023a). 8 Facts About Recent Latino Immigrants to the U.S. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/09/28/8-facts-about-recent-latino-immigrants-to-the-us/ (accessed July 14, 2024).

Pew Research Center (2023b). 11 Facts About Hispanic Origin Groups in the U.S. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/08/16/11-facts-about-hispanic-origin-groups-in-the~us/ (accessed July 14, 2024).

Phinney, J. S., and Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. J. Counsel. Psychol. 54, 271–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271

Portes, A., and Runbaut, R. G. (2006). Immigrant America: A Portrait, 3rd Edn. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

Raffaelli, M., and Ontai, L. L. (2004). Gender socialization in Latino/a families: results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles 50, 287–299. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000018886.58945.06

Richaud, M. C., Mesurado, B., and Lemos, V. (2013). Links between perception of parental actions and prosocial behavior in early adolescence. J. Child Fam. Stud. 22, 637–646. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9617-x

Roberts, R. E., Phinney, J. S., Masse, L. C., Chen, Y. R., Roberts, C. R., and Romero, A. (1999). The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. J. Early Adolesc. 19, 301–322. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019003001

Rodriguez, M. C., and Morrobel, D. (2004). A review of Latino youth development research and a call for an asset orientation. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 26, 107–127. doi: 10.1177/0739986304264268

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sabogal, F., Marín, G., Otero-Sabogal, R., Marín, B. V., and Perez-Stable, E. J. (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: what changes and what doesn't? Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 9, 397–412. doi: 10.1177/07399863870094003

Sanchez, D., Whittaker, T. A., Hamilton, E., and Arango, S. (2017). Familial ethnic socialization, gender role attitudes, and ethnic identity development in Mexican-origin early adolescents. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 23, 335–347. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000142

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., and Jarvis, L. H. (2007). Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 13, 364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364

Smith, E. J. (2006). The strength-based counseling model. Couns. Psychol. 34, 1379. doi: 10.1177/0011000005277018

Soto, D. W., Unger, J. B., Pattarroyo, M., Meca, A., Villamar, J. A., Garcia, M. F., et al. (2022). ¡Pásale!: gaining entrance to conduct research and practice with recent hispanic immigrants: lessons learned from the COPAL study. Front. Public Health 10, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.879101

Stein, G. L., Rivas-Drake, D., and Camacho, T. C. (2016). Ethnic identity and familism among Latino college students: a test of prospective associations. Emerging Adulthood 5, 106–115. doi: 10.1177/2167696816657234

Streit, C., Carlo, G., and Killoren, S. E. (2020a). Family support, respect, and empathy as correlates of US Latino/Latina college students' prosocial behaviors toward different recipients. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 37, 1513–1533. doi: 10.1177/0265407520903805

Streit, C., Carlo, G., and Killoren, S. E. (2020b). Ethnic socialization, identity, and values associated with US Latino/a young adults' prosocial behaviors. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 26, 102–111. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000280

Streit, C., Carlo, G., Killoren, S. E., and Alfaro, E. C. (2018). Family members' relationship qualities and prosocial behaviors in US Mexican young adults: the roles of familism and ethnic identity resolution. J. Fam. Issues 39, 1056–1084. doi: 10.1177/0192513X16686134

Super, C. M., and Harkness, S. (1986). The developmental niche: A conceptualization at the interface of child and culture. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 9, 545–569. doi: 10.1177/016502548600900409

Super, C. M., and Harkness, S. (2002). Culture structures the environment for development. Hum. Dev. 45, 270–274. doi: 10.1159/000064988

Keywords: parenting, rewards, familism, ethnic identity, prosocial behaviors

Citation: Maiya S, Carlo G, Davis AN, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Soto DW and Lorenzo-Blanco EI (2024) Longitudinal relations between parenting practices and prosocial behaviors in recent immigrant Latino/a adolescents: Familism values and ethnic identity as mediators. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2:1464687. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2024.1464687

Received: 14 July 2024; Accepted: 10 September 2024;

Published: 30 September 2024.

Edited by:

Jordan Ashton Booker, University of Missouri, United StatesReviewed by:

Rob Weisskirch, California State University, Monterey Bay, United StatesDaiki Nagaoka, The University of Tokyo, Japan

Chang Zhao, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United States

Copyright © 2024 Maiya, Carlo, Davis, Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, Baezconde-Garbanati, Soto and Lorenzo-Blanco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sahitya Maiya, c2FoaXR5YS5tYWl5YUB1bmguZWR1

Sahitya Maiya

Sahitya Maiya Gustavo Carlo

Gustavo Carlo Alexandra N. Davis

Alexandra N. Davis Seth J. Schwartz

Seth J. Schwartz Jennifer B. Unger

Jennifer B. Unger Byron L. Zamboanga6

Byron L. Zamboanga6 Daniel W. Soto

Daniel W. Soto