94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Comput. Sci., 15 April 2021

Sec. Human-Media Interaction

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2021.644054

This article is part of the Research TopicPerspectives on Multisensory Human-Food InteractionView all 13 articles

The coffee drinking experience undoubtedly depends greatly on the quality of the coffee bean and the method of preparation. However, beyond the product-intrinsic qualities of the beverage itself, there are also a host of other product-extrinsic factors that have been shown to influence the coffee-drinking experience. This review summarizes the influence of everything from the multisensory atmosphere through to the sound of coffee preparation, and from the typeface on the coffee packaging through the drinking vessel. Furthermore, the emerging science around sonic seasoning, whereby specific pieces of music or soundscapes, either pre-composed or bespoke, are used to bring out specific aspects in the taste (e.g., sweetness or bitterness) or aroma/flavor (nutty, dark chocolate, dried fruit notes, etc.) of a coffee beverage is also discussed in depth. Relevant related research with other complex drinks such as beer and wine are also mentioned where relevant.

Coffee is one of the oldest of beverages, with the beans first cultivated in Ethiopia many millennia ago (Buffo and Cardelli-Freire, 2004). It is also one of the world's most popular beverages (Lim et al., 2019). By the opening years of the twenty first Century, it was estimated that somewhere in the region of one and a half billion cups of coffee were being consumed every day somewhere around the world (see Luttinger and Dicum, 2006, p. ix), or more than 400 billion cups annually (Illy, 2002). Coffee is considered to be the second biggest export product after oil for many developing countries. Over the years, a rich culture has evolved around the preparation and consumption of coffee (e.g., Robinson, 1893; Schultz and Yang, 1997; Pendergast, 2001; Weinberg and Bealer, 2001; Luttinger and Dicum, 2006; Kleidas and Jolliffe, 2010; Tucker, 2011). The beverage that so many of us enjoy today reflects a complex combination of the genetics of the coffee plant, the roast, grinding, and extraction of the beans (e.g., Sarrazin et al., 2000; Glöss et al., 2013).

Coffee is a very chemically complex beverage, with an estimated 850–1,200 volatile compounds (e.g., Grosch, 1998; Buffo and Cardelli-Freire, 2004; Fisk et al., 2012; Clarke, 2013; Faina, 2013; Yeretzian, 2017)1, as compared to just 600–1,000 in a quality glass of wine (e.g., Rapp, 1990; Tao and Li, 2009), and around 137 natural volatiles in a glass of apple juice (Maarse, 1983). At the same time, however, it is also worth noting that only roughly 25–30 key volatile compounds actually contribute to the aroma/flavor of the final beverage (Buffo and Cardelli-Freire, 2004; Faina, 2013). In fact, according to Grosch, there may only be 13 really important volatiles contributing to the aroma/flavor (e.g., Grosch, 1998; Sarrazin et al., 2000).

While it appears to many of us that we taste primarily with our tongue, all the senses are actually involved in the appreciation of the flavor of food and drink (see Spence, 2015d). In a sense, we really taste with our mind, since that is where the various sensory cues are first combined, along with the influence of mood and emotion (Spence, 2017a; see also Mitenbuler, 2015, p. 6). It is certainly true that the acidity-bitter-sweet nexus is crucial for those wanting to deliver a “well-balanced” cup of coffee (e.g., Seninde and Chambers, 2020; see also Costello, 2009).2 However, matters are soon complicated by the fact that certain smells, like caramel (that one can sometimes find in the aroma of a cup of coffee), are associated with specific taste properties, such as sweetness (Blank and Mattes, 1990; Stevenson and Boakes, 2004; see also Labbe et al., 2006). It is really the volatiles resulting from the fermentation and, perhaps more importantly, the roasting (Yeretzian et al., 2012; Schenker and Rothgeb, 2017), and, thereafter, the grinding of the beans and the extraction of the coffee that turn out to be key to delivering that most desirable of aroma/flavor profiles that so many of us know and love (e.g., Semmelroch and Grosch, 1996; Grosch, 2001; Kerler and Poisson, 2011; Fisk et al., 2012; Charles et al., 2015). The majority of the coffee aroma is carried by the coffee oil that constitutes roughly 10% of the roasted coffee bean (Buffo and Cardelli-Freire, 2004).

A great deal of sensory analysis research has been conducted concerning the volatiles that are given off by different coffee plant cultivars (e.g., Arabica, Robusta) as a function of the specificity of the processing, including the fermentation (Schwan et al., 2012), and, perhaps most importantly, the roasting profile that they undergo (e.g., Calviño et al., 1996; Geel et al., 2005; Bhumiratana et al., 2011; Yeretzian et al., 2012; Caporaso et al., 2018). The coffee grown in different parts of the world tends to be associated with different taste/aroma properties (e.g., Costa Freitas and Mosca, 1999; Pawliszyn et al., 2008). Brazilian coffee, for example, tends to be sweeter than the coffees from Africa, which are often more acidic. The aroma of Coffea canephora (Robusta) tends to have a harsher earthier note due to the higher concentration of phenolic compounds such as guaiacol and vinylguiacol (Faina, 2013).

While the coffee aroma is made up of a complex mix of volatile compounds, the sourness, bitterness, and astringency result from the presence of a variety of non-volatile compounds (Vitzhum, 1999). As Stuckey (2012, p. 197) notes in her book, coffee is one of the world's most widely consumed bitter foods (see also McLagen, 2015). However, it is important to note that the caffeine is responsible for only about 10% of the bitterness that one tastes in a cup of coffee (this is why decaffeinated coffee tastes pretty much as bitter as the caffeinated variety). The majority of the bitterness in coffee is actually derived from the phenolic acids that are generated by the roasting process (see Stuckey, 2012, p. 197). One of the most salient ways in which coffee varies is in terms of its strength or bitterness (Dijksterhuis, 1998; Köster, 2003), with the degree of roasting described as “light,” “medium,” or “dark” (Buffo and Cardelli-Freire, 2004). Over the last decade or so, commentators have noted a general shift toward a preference for a stronger coffee in the west (Lambert, 2009).

The nutty, chocolately, fruity, cereal, and floral aromas that roasting and blending the right combination of beans can help to deliver are all enjoyed (or rather detected) primarily by the olfactory receptors in the nose (Spence, 2015a). In fact, coffee is one of the few drinks that is mentioned as sometimes being even more pleasurable orthonasally as we sniff and inhale the aroma,3 than when we get a retronasal burst of flavourful volatiles pulsed out from the back of the nose (Rozin, 1982; cf. Ge, 2012). “Oral referral” is the name given to the fact that we all tend to mislocalize food aromas that are detected by the olfactory receptors in the nose to the mouth, and hence experience them as tastes (see Spence, 2016; see also Heath, 1988).

Researchers working at NIZO in New Zealand have argued that our mouth makes a different sound when we rub our tongue against the soft palate on the roof of the mouth after having tasted black coffee vs. after drinking coffee with a little cream (van Aken, 2013a,b; see also Nicola, 2013). The sounds that are associated with the consumption of coffee—think here only of the sound of slurping (Youssef et al., 2017; see also Seo and Hummel, 2011)—this something that is a distinctive element of professional coffee cupping (Schoenholt, 1995), is also an important part of the tasting experience (or at least it can be). Even appreciative food sounds (e.g., “Aaaaagh”) have been suggested to influence people's judgments of the healthfulness of a beverage (Arroyo and Arboleda, 2021; see also Winter et al., 2019). In contrast to many other beverages, though, the visual appearance of a freshly-brewed filter coffee tends to be rather less informative than, say, the subtle gradations of shadings that one finds in a glass of wine (see Little et al., 1959; Spence, 2010a,b; Dmowski and Dabrowska, 2014).4 Nevertheless, the coffee-drinking experience is one that can most definitely engage all of the senses, as we will see below (see Spence, 2014c).

A growing body of empirical research now shows that many aspects of the environment influence the coffee-drinking experience in a more-or-less subtle manner (see Spence, 2015b; Samoggia and Riedel, 2018): Everything from the cup to the background music (e.g., North and Croeser, 2006; Gater, 2010) to the softness of the chair that you happen to be sitting on (de Luca and Pegan, 2014; see also Pramudya et al., 2020), and from the brightness of the ambient lighting (e.g., Gal et al., 2007) through to the sound of coffee preparation (see Knöferle, 2012)—not to mention the background smell of the toasted cheese sandwiches as Starbucks found to their cost a few years ago (see Nassauer, 2014). The majority of the research on product-extrinsic influences on the perception of coffee has been conducted amongst those who like coffee. It must therefore remain an open question for future research as to whether or not those who do not like this bitter-tasting drink would be influenced in a similar manner by such product-extrinsic factors.

The cup, or receptacle, that you drink your coffee from has more of a role than you might think: Everything from its size (Van Doorn et al., 2017) through to its shape (Carvalho and Spence, 2018), and from its color (Guéguen and Jacob, 2012; Van Doorn et al., 2014; Carvalho and Spence, 2019; Hansen, 2019; see also Favre and November, 1979 and Labbe et al., 2021) through to its texture (Carvalho et al., 2020) and even its material properties (Carvalho and Spence, 2021). Drinking coffee from a heavier cup is likely to intensify the aroma and perceived quality of whatever you happen to be smelling/drinking (cf. Gatti et al., 2014; Kampfer et al., 2017). The art on top of a latté has also been shown to influence how much people enjoy and, more importantly, are willing to pay for, their coffee too (see Van Doorn et al., 2015).

People sometimes say that hot beverages taste better from their own favorite mug rather than from someone else's too. The limited scientific evidence on this particular score would certainly appear to provide at least tentative support for the claim (Spence, 2017a). It has even been suggested that the quality of the coffee paraphernalia (e.g., the sugar dispenser) can make a difference to judgments of the quality of coffee, though robust data supporting this claim is yet to be forthcoming (Ariely, 2008).

Researchers have known for years now that the atmosphere and environments in which we eat and drink can exert a significant influence over the coffee-drinking experience (e.g., Sester et al., 2013; see Spence and Carvalho, 2020, for a review). Coffee is, of course, not unique in this regard (Kotler, 1974; Bell et al., 1994; see also Keller and Spence, 2017), though, as one of the world's most popular beverages, it has certainly attracted more than its fair share of attention from the research scientists (e.g., Petit and Sieffermann, 2007; Maguire and Hu, 2013; Richelieu and Korai, 2014; Wu, 2017). These days, researchers often experiment with virtual and augmented reality (VR and AR, respectively) environments in order to help study the impact of the atmosphere, in one study comparing people's ratings of various different coffee beverages in the virtual coffee shop—complete with the appropriate visuals, sounds, and even the smell of freshly-baked cinnamon rolls—vs. a standard sensory testing lab in one study (Bangcuyo et al., 2015; see also Wang et al., 2020). The evidence clearly shows that the context, no matter whether real or virtual, really can make a difference to the tasting experience. Bangcuyo et al.'s study, for example, demonstrating that people's discriminative abilities and preferences amongst a range of different coffees could be better predicted by having them evaluate the beverages in the context of a virtual coffee shop, rather than it the traditional sensory testing laboratory.5 Other researchers, meanwhile, have tried to evoke a specific drinking situation by having their participants read a description before tasting, and rating, coffee (e.g., Kim et al., 2016; Spinelli et al., 2017).

This growing understanding of the many product-extrinsic factors that have been shown to influence the multisensory tasting experience have led to an explosion of multisensory testing events where the various environmental cues are specially designed to match and/or to enhance a given taste quality (e.g., Velasco et al., 2013b; Spence et al., 2014a; Wang and Spence, 2015a). What is more, many consumers are becoming increasingly intrigued by the growing wave of interest in “Sensploration” (see Aroche, 2015; Spence, 2019b), this, the name given to the growing interest in exploring the surprising, almost synaesthetic, connections between our senses (see Spence, 2012). The 2015 Tate Sensorium exhibition provided one intriguing and extremely popular example of this, when a series of paintings were accompanied by scents, ultra-haptics, and even a gritty, smoky chocolate to taste (see Davis, 2015; Pursey and Lomas, 2018; Spence, 2020d). However, a number of the coffee exhibitions that have been put on in museums in the last few years have also become increasingly multisensory and immersive, As, for example, in the case of the Cosmos Coffee exhibition at the Deutsches Museum in Germany (https://www.deutsches-museum.de/en/exhibitions/special-exhibitions/archive/2019/cosmos-coffee/).

In one striking recent study, 120 consumers in a coffeehouse in a Dutch university campus rated a coffee as tasting stronger and liked what they were drinking more when exposed to an ad displaying vertically- rather than horizontally-oriented visual cues during a coffee sample test (Van Rompay et al., 2019). The participants in this particular study were told that the new coffee blend that they were rating was linked to a poster shown on the wall (though, in fact, it was actually the coffeehouse's regular blend that they were tasting). When the ad incorporated vertical lines, participants rated the taste intensity of the coffee significantly higher relative to those participants who viewed a poster displaying horizontal elements instead. Mean ratings (on a 7-point scale) were 4.68 vs. 3.88 for taste intensity and 5.41 vs. 4.67 for the taste liking, as a function of the orientation of the background stripes/lines on the coffee ad that they saw.

Even the typeface of the text on coffee packaging has been shown to influence people's perception of specialty coffee, with angular typeface enhancing expectations, and thereafter experienced, acidity in a cup of coffee amongst 146 regular consumers in one recent Brazilian study (de Sousa et al., 2020). The latter study, note, building on a growing body of empirical research showing that shape properties are matched to both tastes and aromas (e.g., Seo et al., 2010; Deroy et al., 2013; Hanson-Vaux et al., 2013; Velasco et al., 2018a). Furthermore, staring at angular (rather than rounded) shapes (Gal et al., 2007; Huisman et al., 2016) or typeface (Velasco et al., 2018b) has been shown to accentuate the acidity (rather than sweetness) in food and drink more generally (though see also Rolschau et al., 2020).

As yet, though, it is unclear the extent to which such shape matches to taste/flavor are based on the hedonics or valence (i.e., matching pleasant shapes with pleasant tastes with round and sweet both being liked, whereas angular and bitter are typically not; Salgado-Montejo et al., 2015) vs. on some kind of spatiotemporal translation of the taste experience that people have (e.g., with sour tastes tending to come and go rapidly, while sweet tastes tend to linger on the palate, coming and going much more gradually; see Deroy and Valentin, 2011; Obrist et al., 2014). Of course, both explanations may play a role in explaining why people match shapes to tastes/flavors in quite the way they do.

Background noise can exert a dramatic impact over our tasting abilities (Woods et al., 2011; Spence, 2014a, 2019a; Yan and Dando, 2015), masking our ability to perceive certain tastes (such as sweet and salt) while, at the same time, enhancing our ability to taste others (e.g., umami; see Spence et al., 2014b). On the downside, however, loud background noise (noise, note, defined as sound that is unpleasant) can interfere with our tasting abilities (e.g., Bravo-Moncayo et al., 2020; see also Alamir et al., 2020, Rahne et al., 2018, Seo et al., 2011, 2012, Stafford et al., 2012, 2013, Trautmann et al., 2017, and Velasco et al., 2014). In a recent study by Bravo-Moncayo et al. (2020), for example, listening to loud background music reduced a range of desirable attributes in a sample of coffee, being especially noticeable for ratings of bitterness and aroma intensity, as well as resulting in a lower willingness to pay. A total of 384 participants tasted and rated the same black coffee (a medium roast green Arabica from Ecuador) while listening to louder or quieter background noise [85 vs. 20 dB(A), respectively]. Given such results, is it any wonder that professional tasters often ask for silence when they taste (e.g., see Peynaud, 1987; see also Crocker, 1950)? At the same time, however, it is important to stress that the latest research also shows that listening to the appropriate music, rather than noise, can help to enhance the multisensory tasting experience (see Spence et al., 2019a, for a recent review of the evidence supporting this claim).

Background music has also been shown to exert a not inconsiderable effect over the multisensory tasting experience. This is an area that has come to be known as “sonic seasoning” (see Spence, 2017b). There has, in fact, been a huge explosion of interest in the crossmodal influence of atmospheric soundscapes and music on multisensory taste/flavor perception over the last decade or so (see Spence et al., 2019a). Indeed, the world-famous chef, Heston Blumenthal (of The Fat Duck fame, https://thefatduck.co.uk/) has described sound as the “forgotten flavor sense” (see Spence et al., 2011). Furthermore, when interviewed on the BBC's Radio 4, Blumenthal said that: “I would consider sound as an ingredient available to the chef.” Other forward-thinking chefs, meanwhile, have even gone so far as to include a musical recommendation for each of the recipes in their cookbooks (e.g., see Pelaccio, 2012). Relevant here, it has been suggested that the emotion evoked by listening to music can influence how we end-up seasoning a dish or making a drink, and hence even perhaps also how strong a coffee we go for (see Spence and Piqueras-Fiszman, 2014; Spence, 2015c). Researchers have demonstrated that listening to specially chosen prerecorded pieces of classical music (chosen, in this case, because they could easily be associated with either a sweet, or sour taste) biased the sweet-sour balance when participants were tasked with making a well-balanced drink given a range of sweet and sour ingredients to blend together (Kontukoski et al., 2015).

Here it also worth bearing in mind the cultural aspects/differences in coffee drinking practices. That is, people drink coffee in many different ways around the world. Hence, even if the music may be the same, its impact on the multisensory coffee tasting experience might be expected to differ. As such, it is worth stressing that the majority of the research that has been reviewed here has been conducted in Western consumers drinking conventional filter or espresso coffees.

The music that is playing when people decide which coffee to choose has been shown to influence their decisions too. In fact, a growing body of empirical research suggests that playing (e.g., ethnic) music can bias our food and drink choices (e.g., North et al., 1997, 1999; Feinstein et al., 2002; Muniz et al., 2017; Zellner et al., 2017; see also de Paula et al., 2020),6 and possibly even our perception of the authenticity/ethnicity of the dish too (Yeoh and North, 2010). Background music has also been shown to bias people's covert visual attention and eye movements (e.g., Padulo et al., 2018; Peng-Li et al., 2020). There is also a literature emerging on the impact of variations in the physical parameters of sounds and music (e.g., high- or low-pitched instrumental sounds or voices) on consumer choice (see Lowe et al., 2018; Biswas et al., 2019). There are, then, likely a number of ways in which what we hear influences both what we taste and what we think about the experience (see Spence et al., 2019b, for a review of the emerging body of literature).7 However, before we take a closer look at the emerging literature on sonic seasoning, it is worth noting that those sounds that are related to the preparation of the coffee itself also help set our coffee-related expectations and hence experiences.

There are, in fact, a number of different ways in which the sonic backdrop can influence our tasting experiences (including noises, atmospheric sounds, and music): The sounds of preparation, think only of the sounds of the coffee machine grinding, dripping, steaming, etc. are undoubtedly important: These sounds, no matter whether we pay attention to them or not, can help set our sensory expectations regarding the drink that we are about to consume (see Knöferle, 2012). Here, it is important to note that very often we taste what we predict, or expect that we are going to taste (see Deliza and MacFie, 1997; Piqueras-Fiszman and Spence, 2015, for reviews). It turns out that it is possible to hear the temperature of a beverage such as the coffee as it is poured into a cup (Velasco et al., 2013a,c), with changes in the temperature of a liquid changing the viscosity which, in turn, changes the pitch of the sound (see Parthasarathy and Chhapgar, 1955). That is, the majority of people can discriminate the sound of hot from cold water when poured at a level that is significantly above chance. Given that the temperature at which beverage, such as coffee, is served, influences the release of aromatic flavor volatiles from the surface of the drink (Steen et al., 2017), the sound of temperature likely helps to subtly set people's aromatic flavor expectations too. The various informative sounds associated with the preparation of coffee can help to set people's (often unconscious) expectations, just like the “sizzle that sells the steak.” This, the famous 1930s strapline from legendary North American marketer Elmer Wheeler (Wheeler, 1938)8.

Jo Burzynska, a professional New Zealand wine judge and sound designer has developed some intriguing soundscapes recorded in the vineyards to be heard while tasting the wine made from the grapes that were harvested in the place that drinkers are listening to Burzynska (2012, 2018). Listening to such soundscapes helps to draw one's attention to the natural origins of the product, and perhaps also emphasizes notions of terroir (see also Brennan, 2020; Unusual Ingredient, https://unusualingredients.co/). Burzynska's work can be seen as building on prior work showing that the sound of the sea can enhance the taste of seafood (Spence et al., 2011; see also Marinetti, 1932/2014). Here, then, one could perhaps think about connecting the coffee drinker to the nature sounds of the coffee plantation where the coffee beans (or rather coffee cherries) fruited. At the same time, however, it is worth stressing that the aromas that so many of us enjoy in a cup of freshly-brewed coffee are perhaps more dependent for their delicious flavor on the processing (including the fermentation, roasting, and thereafter the grinding and extraction) than in the case of wine, hence meaning that the connection with the coffee plantation is a little weaker than in the case of the fruits of the vine for wine. That being said, there is now plenty of evidence to suggest that environmental sounds do indeed influence the tasting experience (e.g., in the case of gelati; Lin et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019a,b).

The music we listen to affect our perception of everything from the sexiness of another's touch (even if that caress happens to be delivered by a robot; see Fritz et al., 2017) through to the softness of the material that we happen to be evaluating (Imschloss and Kuenhl, 2019). Even our rating of the attractiveness of pictures of other people (May and Hamilton, 1980) and paintings can be modified by the background music (see Spence, 2020c, for a review). There is, in other words, extensive evidence of “sensation transference” (see Cheskin, 1972): This is the name given to what happens when what we feel about one stimulus is automatically carried over to what we think about a simultaneously-experienced but independent stimulus (see also Lowe and Haws, 2017). This is presumably one of the mechanisms by which “sonic seasoning” operates in the case of multisensory coffee tasting.

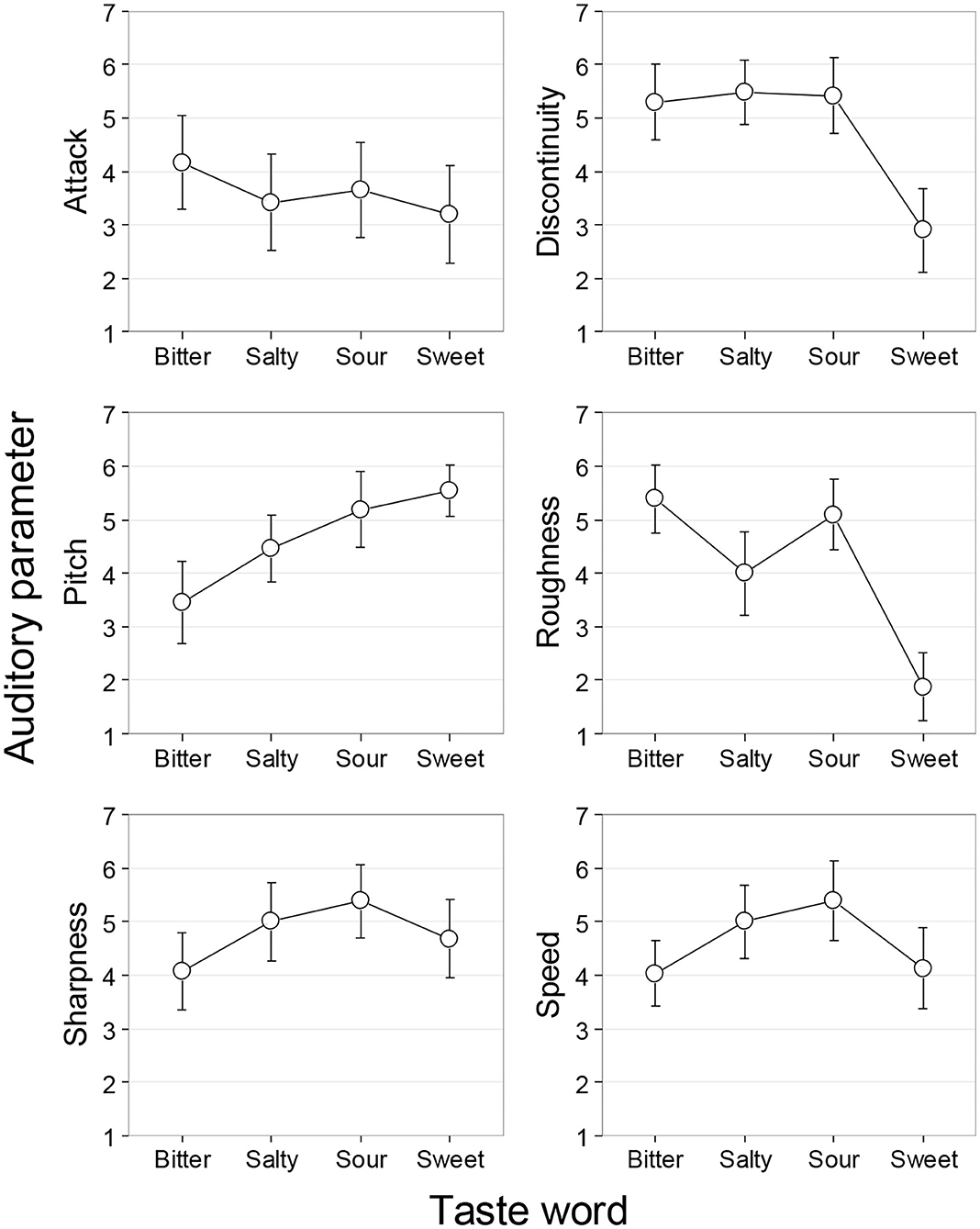

There is now a large and growing body of peer-reviewed empirical research matching sound qualities to specific taste qualities (e.g., see Knöferle and Spence, 2012; Knöferle et al., 2015; and for more recent sonic seasoning research, see only: Mesz et al., 2011, 2012; Guetta and Loui, 2017; Watson and Gunter, 2017; Höchenberger and Ohla, 2019). A summary of the musical properties associated with each of the basic tastes as reported by Knöferle et al. (2015) is shown in Figure 1. Meanwhile, Spence et al. (2019b, Table 1) provide a detailed review of sonic seasoning studies that have been published to date.

Figure 1. Participants' selections for (psycho-)acoustic parameters in response to basic taste words in Knöferle et al. (2015, Experiment 1). Error bars indicate 95% within-subjects confidence intervals (Morey, 2008).

There has, in fact, been an explosion of research on sonic seasoning over the last decade (Spence, 2017b). Contemporary interest in this area builds on the early research demonstrating the “pitch of harmony” for many food flavors (e.g., Holt-Hansen, 1968, 1976; Rudmin and Cappelli, 1983; see also Reinoso Carvalho et al., 2016c). Crucially, recent research has successfully managed to replicate Holt-Hansen's early suggestion that simply by matching the tone to the taste (or flavor) one can actually enhance the subjective enjoyment of the tasting experience (Reinoso Carvalho et al., 2015a). Much of this research has been conducted with bittersweet foods such as chocolate (e.g., Reinoso Carvalho et al., 2015b) and beer (e.g., Reinoso Carvalho et al., 2016a,b). There is therefore every reason to believe that similar crossmodal effect would also be demonstrated with coffee as well. At the same time, changing what people hear has also been shown to influence both sensory discriminative and hedonic response to gelati (Kantono et al., 2016).

Research from a wide range of consumers shows the musical parameters that are matched with specific tastes (Knöferle and Spence, 2012; Knöferle et al., 2015; see also Ngo et al., 2011 and Simner et al., 2010, on the vocal parameters matched with each of the four basic tastes), temperatures (Wang and Spence, 2017a), textures (Reinoso Carvalho et al., 2017), trigeminal attributes (such as spicy, Wang et al., 2017), and olfactory notes (e.g., Crisinel and Spence, 2010, 2012a). Low-pitched music has also been shown to enhance other beverage qualities, such as the body of a red wine (Burzynska et al., 2019). There now exists a reasonably well-worked out musical menu of the sonic characteristics that help bring out the acidity, bitterness, and sweetness in a multisensory tasting experience. Furthermore, given all the sonic seasoning tracks that have been generated to date, it has been possible to compare different compositions in order to then extract the distinctive sonic features of the tastiest of musical tracks (Wang et al., 2015). This kind of analysis has, for instance, revealed that the lower the pitch, the more bitter the sound.

In one of the earliest sonic seasoning studies, Crisinel et al. (2012) demonstrated that a bittersweet cinder toffee could be sonically seasoned to taste either a little sweeter or more bitter. Which sonic manipulation is most appropriate might, then, depend on an individual taster's preferences. Meanwhile, in one marketing-led intervention, the Xin café in Beijing used augmented glassware to play sweet music and so reduce the sugar content in the hot beverages they served to their customers (Blecken, 2017). Note here that the research suggests that the sweetest tracks tend to be higher in pitch and consonant (Wang et al., 2015). The sound of a tinkling piano has also been associated with sweetness in several studies (e.g., see Crisinel and Spence, 2012a).

Septimus Piesse (1891), the British-born French perfumer, published his famous scent scale in the latter half of the nineteenth Century, explicitly matching various olfactory notes with specific musical notes. Meanwhile, contemporary interest in the sound of odor has highlighted the musical translation for the fruity, earthy, and nutty notes that one can find in a specialty coffee (e.g., Belkin et al., 1997; Crisinel and Spence, 2010, 2012a). Indeed, given that 75–95% on what we think we taste, we actually smell (Spence, 2015a, 2016), matching the sonic seasoning to what we smell (whether by the orthonasal or retronasal route) is likely going to be especially important. The typical aromas that the consumer may expect to experience in a cup of freshly-brewed specialty coffee include “nutty,” “almond,” “brown spice,” “floral,” and “jasmine” (see, for example, the coffee lexicon developed by World Coffee Research: https://worldcoffeeresearch.org/work/sensory-lexicon/; Chambers et al., 2016; Croijmans and Majid, 2016, on the language used by the coffee experts).9

There is growing interest in sonically signaling olfactory properties (be it of a drink or other fragranced product; see Deroy et al., 2013, cf. Mahdavi et al., 2020). It has been suggested that such crossmodal influences may build on the various direct connections that have been reported between the nose and the ear (e.g., see Wesson and Wilson, 2010, 2011; Zhou et al., 2019). At the same time, however, there may be more indirect routes to sonic seasoning given that, as has been mentioned already, different olfactory notes can be associated with taste properties such as sweetness (see Blank and Mattes, 1990; Stevenson and Boakes, 2004). So, for example, the aromas of caramel and vanilla are both associated with sweetness (cf. Bronner et al., 2012). Bronner et al. (2012) developed music specifically for the flavor of vanilla and citrus. However, given that these tastes are strongly linked with sweetness and acidity, it remains rather unclear whether the music was actually primarily being matched to the dominant taste that we associate it with.

Another of the ways in which sonic seasoning works, especially for a “complex” tasting experience, is to help draw a taster's attention to something in their tasting experience that they might otherwise overlook (see Spence, 2019c, for a review). Here, it is also worth noting that a carefully-orchestrated piece of music can help to structure a taster's temporally-evolving taste experience (e.g., see Crisinel et al., 2013).10 This was demonstrated in one innovative project were a separate instrumental track was associated with each of the dominant olfactory notes in a cognac (e.g., candied orange, crème brûlée, coffee, violet flower, etc.). Initially, people were encouraged to sniff each distinct aroma while listening to the matching instrument. Thereafter, they were supposed to taste the drink while listening to a musical composition that incorporated elements from each of the individual tracks. The idea was that the temporal structure of the music (with different instruments tied to different aroma notes) would enable the consumer to better pick out the various distinctive elements in their tasting experience. A similar approach was adopted more recently by chef Jozef Youssef (of Kitchen Theory) and sound designer Steve Keller in a project for Chivas whisky (The Sound of Chivas Ultis, 2017). The Godiva: A symphony of taste project from 2018 provides yet another example of how compositions can be created specifically to match the temporally evolving taste/flavor profile of a complex food such as chocolate.11

There are semantic qualities and associations that we may have with particular styles of music. There is, for example, a wide body of research on the association between classical music and quality (e.g., Spence et al., 2013; Wang and Spence, 2015b; see also Zolfagharifard, 2013). In fact, across a range of situations, people have been shown to spend more and to rate taste experiences as higher class (or better quality) when in the presence of classical music, e.g., rather than pop music (see Spence, 2017a, for a review; see also De Luca et al., 2019).12 The semantic associations with different styles of music may, then, be expected to prime certain qualities or attributes that are expressed in the taste of whatever it is that we happen to be tasting, be that a cup of coffee or something else. By systematically pairing music with taste/flavor it is possible to enhance the multisensory tasting experience, as many companies and brands have now started to do (e.g., Victor, 2014; McCarthy, 2015; Sanderson, 2015).

In one unpublished study, Gater (2010) investigated the impact of listening to different musical genres on people's perception of the sensory properties of a commercial coffee sample over a period of 10-min. The participants either tasted in silence, or else while listening to jazz, classical, or rock music genres. The musical selections all had equivalent tempi (≥90 BPM) and volume (70 dB). The seven participants who took part in this study (this sample size, unfortunately likely too small to obtain reliable significance) rated the same standardized coffee beverage on four key characteristics (aroma, flavor, bitterness, and astringency) every minute using a Qualitative Descriptive Analysis (QDA) methodology. Despite the very small sample size, Gater was nevertheless still able to observe some intriguing trends suggesting that exposure to the background music increased the time needed to detect a significant change in the aroma of the coffee. Gater's results also suggested that the association between jazz music and a café-type atmosphere resulted in participants rating the coffee's flavor, bitterness, and astringency as somewhat less intense than in the other conditions (see also Fiegel et al., 2014; Ziv, 2018; De Luca et al., 2019, on the positive effect of background music on the enjoyment of food). There is some evidence of there being a preference for listening to live rather than pre-recorded music while drinking coffee, at least amongst coffee drinkers in South Africa (North and Croeser, 2006; see also Wang and Spence, 2015b). Elsewhere, Brown (2012) has also suggested specific musical matches for different beers, and co-creation of music for coffee shops has also been suggested as a successful strategy (Jeon et al., 2016; see also Unnava et al., 2018, on the more social aspects of caffeine consumption).

It has long been known that listening to music provides an effective means of communicating affect, and possibly also basic emotions (e.g., Konečni, 2008; Reybrouck and Eerola, 2017; though see Cespedes-Guevara and Eerola, 2018). The musical manipulation of our emotional state, then, provides another means by which what we hear can influence what we taste, and how much we enjoy the experience (though there may be some cultural differences to be aware of Athanasopoulos et al., 2021). For instance, illustrating the impact of induced emotion on taste, Noel and Dando (2015) conducted a study in which people had to rate a sweet-sour drink at the end of an ice hockey game. Those who were supporting the winning team rated the drink as tasting sweeter than those whose team lost. Similarly, Wang and Spence (2018) demonstrated that simply looking at pictures showing positive or negative emotions, biased people's taste perception. Looking at a happy smiling child accentuated the sweetness in an unfamiliar sweet-sour blend, while looking at a crying child had the opposite effect (see also Desira et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020). Oftentimes, especially when selecting those crossmodal correspondences involving musical stimuli, emotion seems to mediate the mapping, be it between music and paintings, music and color patches, and hence presumably also between music and coffee (see Wang and Spence, 2017c; Spence, 2020c).

Hedonic/emotional sensation transference effects from music to taste have also been demonstrated (e.g., Reinoso-Carvalho et al., 2019, 2020a). Indeed, some of the most exciting recent research has shown that sonic seasoning and sonic sensation transference can be combined and thus be triggered concurrently (see Reinoso-Carvalho et al., 2020b). In the latter study, for instance, Reinoso-Carvalho et al. chose one pair of musical tracks designed to induce emotion, and another pair of tracks that had been demonstrated to give rise to sonic seasoning. In a large-scale between-participants study, each participant listened to one of the four tracks and tasted a piece of chocolate. The results provideded strong support for the crossmodal effect of music on taste ratings, though the emotional influences were numerically larger than those reported for the sonic seasoning tracks in this case. Ultimately, therefore, one of the aims of sonic seasoning research is to pick, or select, music combining elements of “sonic seasoning” to enhance the desirable taste qualities, and positive “emotional sonic sensation transfer” to enhance the overall multisensory experience.13

What is also worth noting here, sonic seasoning, and sonic sensation transference, have now been demonstrated in a wide variety of populations, from the US to the UK, and from Korea to India, and Japan (e.g., see Knöferle et al., 2015; Reinoso-Carvalho et al., 2020a,b). Such findings therefore hint at the possibly universal underpinnings of sonic seasoning and sonic sensation transfer. That said, it should also be remembered that cultural practices around coffee do differ, and hence the influence/impact of music might also be expected to vary—though, this has not been studied much to date.

At this point, it is perhaps worth addressing those naysayers who are critical of the entire sonic seasoning approach. There are those, primarily in the upper echelons of wine appreciation it has to be said, who are minded to say something of the sort, why bother changing the music to improve the taste of the drink, when you can simply pick a different wine that is more to your taste.14 It would seem legitimate to ask whether the same could also be said when it comes to sonically seasoning one's coffee. Other commentators, meanwhile, worry that a well-balanced wine, or presumably coffee, are more likely to be knocked out of balance if music is played that is overly sweet, bitter, or acidic, say (see Crawshaw, 2012). Then again, there have even been some who, perhaps understandably, have doubted whether what we hear has any impact on what we taste at all. Just take the following, from journalist Alice Jones, writing in The Independent newspaper, when she expressed doubt that the claim that “wine tastes better with music” would “stand up to scientific scrutiny.” (Jones, 2012, p. 51). The critics tend to be especially doubtful that such crossmodal effects would be evidenced in expert tasters (like themselves)—though, once again, the evidence suggests that they are wrong on this score too (e.g., see Beckett, 2017; Wang and Spence, 2017b; see also Spence and Wang, 2015a,b,c).

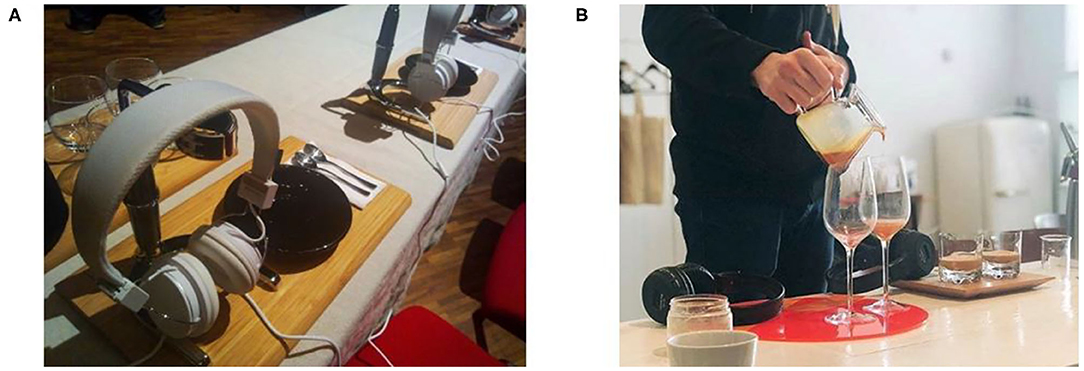

As a sign of the times here though it is worth noting that the growing interest in sonically-seasoning one's coffee beverage has already started to appear at a number of professional barista competitions in recent years (see Figure 2). It all goes to show that the science of enjoying a great cup of coffee isn't only about the liquid in the cup (hugely important though that undoubtedly is), but ultimately involves the optimization of the total experience (Illy and Illy, 2015; Vanharanta et al., 2015), and that undoubtedly includes any music that might happen to be playing in the background. The incorporation of a sonic element can also be seen as hinting at the growing acceptance of the influence that sonic factors have over the multisensory tasting experience.

Figure 2. Multisensory experience designs during barista championships. (A) Rasmus Helgebostad's sonically-enhanced coffee drink served as part of his entry in the 2011 Norwegian barista championships; (B) Matt Winton's multisensory experience of the same signature coffee drink being served in two different setups (including distinct soundtracks) in the 2018 World Barista Championship. This figure reprinted from Spence (2020a, Figure 2).

Ultimately, it is important to note that there is always a sonic backdrop to our coffee tasting experiences. It might be background noise suppressing the tasting experience or else a silence that can itself be uncomfortable/oppressive. Hence, one cannot simply ignore the auditory environment and pretend that it doesn't exist or matter when tasting coffee (see Spence, 2017a). The real question, therefore, is which sounds/musical selections work best to deliver the outcome that the coffee-drinker wants. While some might choose to complement their coffee with matching music, others might prefer more of a contrast (a kind of crossmodal counterpoint if you will). Get the sonic seasoning right, however, and the combination of tastes and tunes can be truly transformative. That, at least, has been the experience of some experienced wine tasters. Just take the following from the late James John (MW—Master of Wine), Director of the Bath Wine School (which is now the Bristol Wine School), as a representative example, when he writes of the combination of Mozart's Laudate Dominum, and Chardonnay: “[…] Just as the sonant complexity is doubled, the gustatory effects of ripe fruit on toasted vanilla explode on the palate and the appreciation of both is taken to an entirely new level” (quoted in Sachse-Weinert, 2012, see also Sachse-Weinert, 2014).15

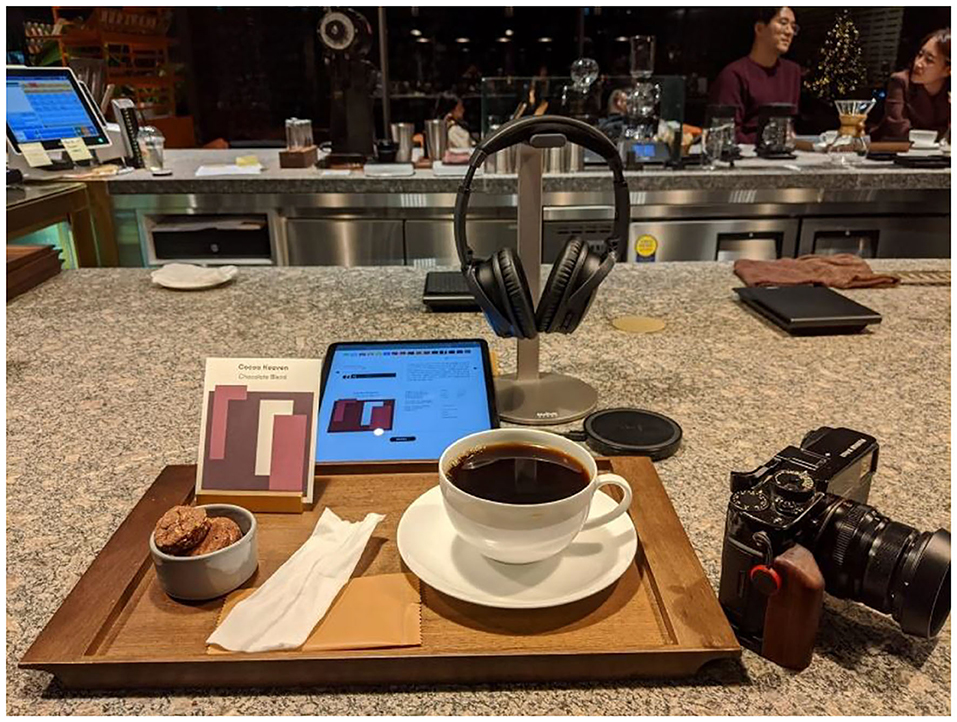

As a taste of things to come, one need only take the example of the speciality coffee shop that opened up recently in Korea where every seat at the counter comes with a pair of headphones so that the music that each customer listens to can be matched to the coffee that they have ordered (see Spence, 2020a) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Korean coffee-shop where music is paired with the choice of coffee designed to match the customer's taste preferences. This figure reprinted from Spence (2020a, Figure 1).

Knowing what we now do about the fascinating world of “sonic seasoning” (Spence, 2017a; Spence et al., 2019a), it can be argued that it makes sense to match the music to the coffee, rather than leaving this opportunity to pair our experience (sensory pleasures) up to chance. This is especially true given that we all live in our own worlds of taste (Bartoshuk, 1980). According to Chaham Yeretzian, one of the foremost coffee chemists out there: “Every coffee drinker is different. What a coffee really tastes like depends on the form of the oral cavity and where the coffee first touches the tongue.” (quoted in Scholl, 2012, p. 30)16. In the same article, Yeretzian also states that: “Different people experience differently too” (quoted in Scholl, 2012, p. 29).

Some of us prefer a slightly sweeter or more acidic finish in our coffee beverages. As such, sonic seasoning can be framed as allowing any one of us to take a great-tasting coffee and season it to our own particular preferences without the need to add sugar or change what we are drinking (Gal et al., 2007; cf. Blecken, 2017). Several individual differences in the worlds of taste that we inhabit are worth mentioning in the context of coffee. These include the fact that there are supertasters (roughly a third of the population) who find coffee more bitter than others—the so-called medium and non-tasters (e.g., Stuckey, 2012, p. 197–198; Masi et al., 2015). There are also sweet-likers and those who are neutral about sweetness in the population (e.g., Bartoshuk, 1991; Looy et al., 1992; Keskitalo et al., 2007; Yeomans et al., 2007; Frayling et al., 2018). At the same time, however, our preference for sweetness in coffee may also be determined, at least in part, by how long we have been drinking it for. Note here only how many people initially start drinking coffee by sweetening it to help mask the bitterness (e.g., Zellner et al., 1983). Once they acquire a liking for the taste of this distinctive bitter beverage, they may then reduce the amount of sugar, or sweetener added.

On top of these genetic differences in gustatory perception, there are also relevant individual differences and selective anosmias that affect smell too (e.g., see Reed and Knaapila, 2010). Such individual differences may also influence people's rating of the best sonic/musical match for a given taste (see Crisinel and Spence, 2012b). Supertasters have, for instance, been shown to match the tastes for which they are especially sensitive to a louder sound than non-tasters (cf. Bartoshuk, 2000).

There is growing commercial awareness of the marketing potential associated with matching-up one's product offering with the more widespread genetic differences in taste/olfaction (in the world of wine, see Blank, 2008; and in the case of beers, see Wu, 2016). There are well-documented individual differences in people's coffee preferences (e.g., Rozin and Cines, 1982; Cristovam et al., 2000). Beyond these genetic differences in the worlds of taste and smell that each and every one of us inhabits, there are also noticeable individual differences in the preferred serving temperature (Borchgrevink et al., 1999), and, as mentioned earlier, this too will likely affect release of volatile aromas from the surface of the coffee beverage.

It is now becoming increasingly common to compose music specifically to match the taste/flavor of a specific food or beverage product, such as, for example, coffee (see Spence, 2013), or any other drink for that matter (e.g., see Howarth, 2014; Birkner, 2016; Spence, 2019b). However, the problem with such bespoke musical compositions is that they are often not widely available (as in the music available on Spotify, say), nor are they necessarily optimized for that feel-good uplifting factor that one associates with so many of the songs one likes to listen to (e.g., Welsh, 2015; Boult, 2016). At the same time, however, one of the key challenges when picking off-the-shelf music is that there can be changes of mode—e.g., from major to minor chord [see Queen's “Bohemian Rhapsody” or in Mozart's Piano Sonata No. 12 in F Major (K332), both examples from Crawshaw (2012); see Spence and Wang (2015a,b,c)]. Indeed, deliberately changing between different pieces of music while people are tasting a drink has been shown to alter the tasting experience dynamically (cf. Wang Q. J. et al., 2019). The evidence clearly shows that even though people know that they may be tasting the same drink, as soon as the music changes, the taste/flavor experience can sometimes change too. Hence, when selecting pre-composed music to sonically season one's coffee drinking experience, one needs to make sure to choose those tracks that are fairly consistent in terms of their mode/instrumentation from start to finish.

People consume coffee for a range of reasons, both hedonic and utilitarian. For example, people sometimes drink in order to help them to stay alert in the morning or give us an uplifting boost during the day (this is the utilitarian cup of coffee). However, at other times the focus is more on enjoying the experience (this is the hedonic cup of coffee). The two key utilitarian aims of drinking coffee are helping people to wake up in the morning, and thereafter giving themselves an uplifting mood boost later in the day. Crucially, specific musical recommendations exist to help the coffee drinker to achieve these goals. What is more, specific emotions can also be triggered when people drink coffee (see Labbe et al., 2015 see also Kanjanakorn and Lee, 2017).

It is worth noting that there has been interest (e.g., with the Marlow vending machine) that was a feature of many public spaces 5 years ago or so, in digitally representing the background noises of the coffee shop, whenever a customer purchased a cup of instant coffee from the machine (Houghton, 2014). I know of other coffee vending machine manufacturers who have been interested in the question of whether having their machines play a particular piece or style of music could be used to bias consumers toward choosing one drink over another. In some of our own research in this space, we actually worked with Starbucks some years ago here in the UK on the design of a downloadable audio track that consumers could listen to at home while drinking the then-new Starbucks Via coffee drink (see Spence, 2017b). The track was designed to contain low notes consistent with the bitter taste of coffee. Unfortunately, however, in this marketing-led intervention, there was no opportunity to determine whether listening to this specially-composed track while tasting coffee had an influence on people's ratings. Meanwhile, Keurig coffee is about to release K-Supreme® Playlists—a set of five Spotify playlists designed to match the distinctive flavor profiles of its coffees (DiPalma, 2021). This, then, hinting at the growing interest in matching music to the coffee tasting experience. The recent launch of various wine apps that allow the consumer to scan a wine bottle label and automatically recommend a putatively matching sound (e.g., see the Wine Listening app; http://winelistening.com/). Meanwhile, Spotify teamed up with the alcohol delivery service Jimmy Brings in 2018 to create the “Songmelier Edition,” pairing a range of wines with the perfect music (Khale, 2018) is also an intriguing development, and may be extended to the world of coffee before too long. There is also emerging interest from the world of HCI in the design of engaging playful gustosonic experiences (Wang Y. et al., 2019).

While this kind of pairing has thus far been established primarily on the basis of empirical studies in which people are given (or asked to imagine in the case of very familiar foods) a range of tastes, aromas, and/or flavors and asked to pitch the best-matching sound from a range of alternatives varying on parameters such as pitch, timbre, roughness, tempo, loudness etc. The results of many such studies have now provided musical menus of sonic features matched to different taste/flavor properties that are then incorporated into the design of new music/soundscapes or else the selection of pre-existing pieces of music with the appropriate properties (see Spence et al., 2019a). However, looking to the future, it is intriguing to consider whether big data analysis and machine-learning approaches might be able to establish connections between music and taste (cf. Caliskan et al., 2017; Chartier and Kitano, 2019). At the same time, analysis of those tracks that have been created to convey specific tastes, and analyzing the sound parameters of the most effective exemplars has also proved to be a fruitful approach (see Wang et al., 2015).

Looking to the future, further research is needed to determine the best musical matches for the various distinctive aromas that are found in coffee (e.g., nutty, dried red fruits, chocolate, grapefruit, hazelnut, etc.)—that is, to go beyond the musical matching of taste properties. Furthermore, it is also unclear whether sonic seasoning may work better when the sounds are presented over headphones, and thus localized intracranially (i.e., in the same place as tastes and flavors), rather than from external loudspeakers. It is also unclear whether sonic seasoning effects are more pronounced when the connection between the music and tasting experiences are made more explicit. Finally, given the fact that complex flavor experiences tend to evolve temporally, then creating music and soundscapes that evolve with the flavors on the palate will likely enhance the beneficial effects of sonic seasoning still further.

Ultimately, the coffee-drinking experience is both complex (Illy, 2002; Spence and Wang, 2018, for a review) and multisensory (Yeretzian et al., 2010; see Spence and Carvalho 2020, for a review). What we taste in a cup of coffee is determined not only by what is in the drinking vessel (i.e., the liquid itself), but also by the sensory properties of the cup from which we happen to be drinking (see Spence and Carvalho, 2019, for a review), not to mention the multisensory attributes of the environment in which we choose to drink (see Bangcuyo et al., 2015; Spence and Carvalho, 2020, for a recent review). In fact, pretty much every aspect of the environment, be it the lighting (Gal et al., 2007), the visual design (Favre and November, 1979; Ly, 2011; Qian, 2014; Van Rompay et al., 2019; de Sousa et al., 2020), the color scheme (Qian, 2014; Spence and Carvalho, 2019), the background music (e.g., Rahner, 2006; Gater, 2010), or any background noise exert a modulatory influence (e.g., Bravo-Moncayo et al., 2020; see Spence, 2014a, for a review). It is all part of the multisensory tasting experience, broadly-defined (Kotler, 1974; Spence, 2017a), as certain famous coffee chains have known for decades (e.g., Pine and Gilmore, 1998, 1999; Carbone, 2004; and see Spence and Carvalho, 2020, for a recent review).

The multisensory aspects of the coffee-drinking experience are, of course, also influenced by branding (e.g., Martin, 1990), typeface, and packaging design (e.g., Henry, 2009; Harith et al., 2014; Sousa et al., 2020), not to mention the sensory-descriptive language (Fenko et al., 2018), and any other information that may be provided about the coffee (e.g., eco-labeling; see Scholl, 2012; Sörqvist et al., 2013; Van Loo et al., 2015; cf. de Pelsmacker et al., 2005). All that before one gets to the influence of celebrity endorsement (Muston, 2012).

During the current Covid-19 pandemic, as more of us are drinking our coffee at home than ever before, it makes more sense than ever to optimize the multisensory atmosphere in our own homes to help get the most out of each and every cup (see Spence, 2020b, 2021). And while, as we have seen, every aspect of the environment is undoubtedly important (see Spence and Carvalho, 2020, for a review), perhaps the simplest element of the atmosphere to change and optimize is the music we listen to while enjoying a cup of coffee (Spence, 2017a). Notice here how sonically-seasoning one's coffee-drinking experience at home to help maximize the desired effect/experience also fits right in with the growing interest that has emerged in optimizing and/or personalizing the multisensory environment in order to deliver the kind of tasting experience that you, the coffee consumer, wishes to have (Spence and Carvalho, 2020; see also Hall, 2012; Walton, 2012).

CS wrote all parts of this review.

This research was supported by a grant from the AHRC-AH/L007053/1.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. ^Though the majority of estimates tend to be toward the lower end of this range.

2. ^Salty and umami are not such dominant taste qualities of ground coffee, though the “smoked ham” note can be a distinctive feature in some instant coffees (Sarrazin et al., 2000).

3. ^Indeed, cross-cultural studies often highlight the smell of coffee as being one of the most pleasant of smells (e.g., Knowles, 1963; Ayabe-Kanamura et al., 1998).

4. ^Though, as noted by Spence and Carvalho (2020), the visual appearance of the crema appears to be an especially salient sensory cue in the marketing of espresso coffees.

5. ^Much of the sensory panel work is done under red lighting in order to mask the visual appearance of the products under consideration (cf. Oberfeld et al., 2009; Spence et al., 2014a). Is it any wonder, one might ask, that so many new food and beverage products fail soon after launch when the environments in which they are tasted are so different from the context in which they are likely to be consumed?

6. ^Music, of course, being but one element of the multisensory atmosphere influencing our coffee choice behavior (e.g., Bawa et al., 1989).

7. ^Here, it is also worth noting that the tempo of the music is also an important factor modulating the speed of consumption (e.g., Mathiesen et al., 2020), though a detailed discussion of the literature in this area falls outside the scope of the present review.

8. ^There are a number of examples, now, of where distinctive liquid pouring sounds have been emphasized in adverts (McMains, 2015). See also Anon. (2012), Garber (2012), Knoeferle and Spence (2021), and Spence (2014b), on the advertising potential of sonic cues.

9. ^LeNez by Jean LeNoir Provides a Selection of Kits Highlighting Specific Coffee Aromas. Available online at: https://www.lenez.com/en/kits/coffee?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI2MbirsGd7QIVRbTtCh3m2Ai0EAMYASAAEgLQafD_BwE.

10. ^Here it is also worth noting the similarity in blending different coffees to deliver a harmonized taste and the process involved in harmonizing musical compositions (see King, 2014a,b).

11. ^See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wvH_fYCoPzs; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rph6oyIEJ9o.

12. ^Traditionally, there was a whole area of music designed specifically to be listened to at mealtimes. This is what is known as Tafel music (i.e., table music; Reimer, 1972; Littler, 1989), and was born in the early seventeenth Century in central Europe. In terms of music linked to coffee, one might also consider JS Bach's Café Cantata (BWV 211; https://parkersymphony.org/coffee-and-classical-music).

13. ^Importantly, given the current replication crisis running through the psychological sciences (especially, it has to be said, social psychology), it is worth stressing that the latter results were based on Bayesian statistics (which many statisticians consider to provide a more robust approach than traditional null hypothesis testing. The sample size (>1,600 participants), was also far greater than in the majority of studies of sonic seasoning that have been published to date (cf. Watson and Gunter, 2017; Höchenberger and Ohla, 2019), thus helping increase the power of this study.

14. ^One might wonder here whether the study of effect sizes might help to provide a more objective means of assessing the magnitude of the effect of changing the coffee/wine vs. changing the musical accompaniment.

15. ^And when thinking of the musical match for latte, one might take the following analogy from Luciano Franchi, MD of several London coffee shops when he suggests that “Latte is to coffee what Stock, Aitken and Waterman is to music” (Lambert, 2009, p. 3).

16. ^Though note that we should perhaps be skeptical of the claim that different tastes are detected on different parts of the tongue (i.e., sweetness on the tip of the tongue, acidity on the sides, and bitterness at the back). This outdated notion, in fact based on a mistranslation of an early German text (Hänig, 1901), also appears in promotional materials from Nespresso. While it might be true that subjectively we experience different tastes differently on different parts of the tongue, the taste buds are all sensitive to exactly the same range of basic tastes. That said, there may be more to say on this topic (Feeney and Hayes, 2014).

Alamir, M. A., AlHares, A., Hansen, K. L., and Elamer, A. (2020). The effect of age, gender and noise sensitivity on the liking of food in the presence of background noise. Food Qual. Prefer. 84:103950. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103950

Anon. (2012). Dunkin' donuts flavor radio: chain releases coffee scent when ads play in South Korea. Huffington Post. Availableonline at: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/dunkin-donuts-flavor-radio_n_1724869 (accessed February 16, 2021).

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape our Decisions. London: Harper Collins Publishers.

Aroche, D. (2015). Never heard of Sensploration? Time to study up on epicure's biggest high-end pattern. JustLux. Available online at: https://www.justluxe.com/lifestyle/dining/feature-1962122.php (accessed February 16, 2021).

Arroyo, C., and Arboleda, A. M. (2021). Sonic food words influence the experience of beverage healthfulness. Food Qual. Prefer. 88:104089. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104089

Athanasopoulos, G., Eerola, T., Lahdelma, I., and Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, M. (2021). Harmonic organisation conveys both universal and culture-specific cues for emotional expression in music. PLoS ONE 16:e0244964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244964

Ayabe-Kanamura, S., Schicker, I., Laska, M., Hudson, R., Distel, H., Kobayakawa, T., et al. (1998). Differences in perception of everyday odors: a Japanese-German cross-cultural study. Chem. Senses 23, 31–38. doi: 10.1093/chemse/23.1.31

Bangcuyo, R. G., Smith, K. J., Zumach, J. L., Pierce, A. M., Guttman, G. A., and Simons, C. T. (2015). The use of immersive technologies to improve consumer testing: the role of ecological validity, context and engagement in evaluating coffee. Food Qual. Prefer. 41, 84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.11.017

Bartoshuk, L. M. (1991). Sweetness: History, preference, and genetic variability. Food Technol. 45, 108–113.

Bartoshuk, L. M. (2000). Comparing sensory experiences across individuals: recent psychophysical advances illuminate genetic variation in taste perception. Chem. Senses 25, 447–460. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.4.447

Bawa, K., Landwehr, J. T., and Krishna, A. (1989). Consumer response to retailers' marketing environments: An analysis of coffee purchase data. J. Retail. 65, 471–495.

Beckett, F. (2017). Wine: Why it makes sense to pair what you drink with music as well as what you eat. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/jan/12/wine-pairing-with-music-not-just-with-food (accessed February 16, 2021).

Belkin, K., Martin, R., Kemp, S. E., and Gilbert, A. N. (1997). Auditory pitch as a perceptual analogue to odor quality. Psychol. Sci. 8, 340–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00450.x

Bell, R., Meiselman, H. L., Pierson, B. J., and Reeve, W. G. (1994). Effects of adding an Italian theme to a restaurant on the perceived ethnicity, acceptability, and selection of foods. Appetite 22, 11–24. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1002

Bhumiratana, N., Adhikari, K., and Chambers, E. IV. (2011). Evolution of sensory aroma attributes from coffee beans to brewed coffee. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 44, 2185–2192. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.07.001

Birkner, C. (2016). Stella Artois and The Roots created a music video you can taste: Sounds enhance the beer's sweet and bitter notes. AdWeek. Available online at: http://www.adweek.com/brand-marketing/stella-artois-and-roots-created-music-video-you-can-taste-173057/ (accessed February 16, 2021).

Biswas, D., Lund, K., and Szocs, C. (2019). Sounds like a healthy retail atmospheric strategy: effects of ambient music and background noise on food sales. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 47, 37–55. doi: 10.1007/s11747-018-0583-8

Blank, D. M., and Mattes, R. D. (1990). Sugar and spice: Similarities and sensory attributes. Nurs. Res. 39, 290–293. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199009000-00009

Blank, J. (2008). Which wine drinker are you? Consultant aims to demystify taste as a simple matter of physiology. The Washington Post. Available online at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/story/2008/03/11/ST2008031102507.html (accessed February 16, 2021).

Blecken, D. (2017). Hold the Sugar: A Chinese Café Brand is Offering Audio Sweeteners, Campaign. Available online at: https://www.campaignasia.com/video/hold-the-sugar-a-chinesecafe-brand-is-offering-audio-sweeteners/433757 (accessed February 16, 2021).

Borchgrevink, C. P., Susskind, A. M., and Tarras, J. M. (1999). Consumer hot beverage temperatures. Food Qual. Pref. 10, 117–121. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(98)00053-6

Boult, A. (2016). The 10 most uplifting songs ever - according to science. The Telegraph. Available online at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/music/what-to-listen-to/the-10-most-uplifting-songs-in-the-world—according-to-science/ (accessed February 16, 2021).

Bravo-Moncayo, L., Reinoso-Carvalho, F., and Velasco, C. (2020). The effects of noise control in coffee tasting experiences. Food Qual. Pref. 86:104020. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104020

Brennan, A. (2020). Unusual Ingredients: New immersive dining night to explore how music affects flavour. The Evening Standard. Available online at: https://www.standard.co.uk/go/london/restaurants/unusual-ingredients-tour-london-food-music-a4365801.html (accessed February 16, 2021).

Bronner, K., Bruhn, H., Hirt, R., and Piper, D. (2012). “What is the sound of citrus? Research on the correspondences between the perception of sound and flavour,” in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of Music Perception and Cognition and the 8th Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music (Thessaloniki).

Buffo, R. A., and Cardelli-Freire, C. (2004). Coffee flavour: an overview. Flavour Fragr. J. 19, 99–104. doi: 10.1002/ffj.1325

Burzynska, J. (2012). The sweet rhythms of Italy's vineyards. The New Zealand Herald. Available online at: http://joburzynska.com/ (accessed February 16, 2021).

Burzynska, J. (2018). Assessing oenosthesia: blending wine and sound. Int. J. Food Design 3, 83–101. doi: 10.1386/ijfd.3.2.83_1

Burzynska, J., Wang, Q. J., Spence, C., and Bastian, S. E. P. (2019). Taste the bass: low frequencies increase the perception of body and aromatic intensity in red wine. Multisens. Res. 32, 429–454. doi: 10.1163/22134808-20191406

Caliskan, A., Bryson, J. J., and Narayanan, A. (2017). Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science 356, 183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.aal4230

Calviño, A. M., Zamora, M. C., and Sarchi, M. I. (1996). Principal components and cluster analysis for descriptive sensory assessment of instant coffee. J. Sens. Stud. 11, 191–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.1996.tb00041.x

Caporaso, N., Whitworth, M. B., Cuic, C., and Fisk, I. D. (2018). Variability of single bean coffee volatile compounds of Arabica and Robusta roasted coffees analysed by SPME-GC-MS. Food Res. Int. 108, 628–640. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.03.077

Carbone, L. P. (2004). Clued in: How to Keep Customers Coming Back Again and Again. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Carvalho, F. M., Moksunova, V., and Spence, C. (2020). Cup texture influences taste and tactile judgments in specialty coffee evaluation. Food Qual. Prefer. 81:103841. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103841

Carvalho, F. M., and Spence, C. (2018). The shape of the cup influences aroma, taste, and hedonic judgements of specialty coffee. Food Qual. Prefer. 68, 315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.04.003

Carvalho, F. M., and Spence, C. (2019). Cup colour influences consumers' expectations and experience on tasting specialty coffee. Food Qual. Prefer. 75, 157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.03.001

Carvalho, F. M., and Spence, C. (2021). Do metallic-coated cups affect the perception of specialty coffees? An exploratory study. Int. J. Gastronom. Food Sci. 23:100285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100285

Cespedes-Guevara, J., and Eerola, T. (2018). Music communicates affects, not basic emotions—A constructionist account of attribution of emotional meanings to music. Front. Psychol. 9:215. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00215

Chambers, E. IV., Sanchez, K., Phan, U. X. T., Miller, R., Civille, G. V., and Di Donfrancesco, B. (2016). Development of a “living” lexicon for descriptive sensory analysis of brewed coffee. J. Sens. Stud. 31, 465–480. doi: 10.1111/joss.12237

Charles, M., Romano, A., Yener, S., Barnabàc, M., Navarini, L., Märk, T. D., et al. (2015). Understanding flavour perception of espresso coffee by the combination of a dynamic sensory method and in-vivo nosespace analysis. Food Res. Int. 69, 9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.11.036

Chartier, F., and Kitano, H. (2019). “The aromatic theory of molecular harmonies and sommelery,” in Paper Presented at the Science & Cooking World Congress (Barcelona).

Costa Freitas, A. M., and Mosca, A. I. (1999). Coffee geographic origin—an aid to coffee differentiation. Food Res. Int. 32, 565–573. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(99)00132-5

Costello, M. (2009). Costa Insures the Tongue That Can Tell Sweet Beans From Sour for £10m. The Times, March 9th, 41.

Crawshaw, A. (2012). How Musical Emotion May Provide Clues for Understanding the Observed Impact of Music on Gustatory and Olfactory Perception in the Context of Wine-Tasting.

Crisinel, A.-S., Cosser, S., King, S., Jones, R., Petrie, J., and Spence, C. (2012). A bittersweet symphony: systematically modulating the taste of food by changing the sonic properties of the soundtrack playing in the background. Food Qual. Prefer. 24, 201–204. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.08.009

Crisinel, A.-S., Jacquier, C., Deroy, O., and Spence, C. (2013). Composing with cross-modal correspondences: Music and smells in concert. Chemosens. Percept. 6, 45–52. doi: 10.1007/s12078-012-9138-4

Crisinel, A.-S., and Spence, C. (2010). As bitter as a trombone: Synesthetic correspondences in non-synesthetes between tastes and flavors and musical instruments and notes. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 72, 1994–2002. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.7.1994

Crisinel, A.-S., and Spence, C. (2012a). A fruity note: Crossmodal associations between odors and musical notes. Chem. Senses 37, 151–158. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr085

Crisinel, A.-S., and Spence, C. (2012b). The impact of pleasantness ratings on crossmodal associations between food samples and musical notes. Food Qual. Prefer. 24, 136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.10.007

Cristovam, E., Russell, C., Patterson, A., and Reid, E. (2000). Gender preference in hedonic ratings for espresso and espresso-milk coffees. Food Qual. Prefer. 11, 437–444. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(00)00015-X

Croijmans, I., and Majid, A. (2016). Not all flavor expertise is equal: the language of wine and coffee experts. PLOS ONE 11:e0155845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155845

Davis, N. (2015). Welcome to the Tate Sensorium, where the paintings come with chocolates. The Guardian. Available online at: http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/video/2015/aug/25/welcome-tate-sensorium-taste-touch-smell-art-video (accessed February 16, 2021).

De Luca, M., Campo, R., and Lee, R. (2019). Mozart or pop music? Effects of background music on wine consumers. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 41, 406–419. doi: 10.1108/IJWBR-01-2018-0001

de Luca, P., and Pegan, G. (2014). “The coffee shop and customer experience: a study of the US market,” in Handbook of Research on Retailer-Consumer Relationship Development, eds F. Musso and E. Druica (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 173–196. doi: 10.4018/978-1-4666-6074-8.ch010

de Paula, S. C. S. E., Zuim, L., de Paula, M. C., Mota, M. F., Filho, T. L., and Della Lucia, S. M. (2020). The influence of musical song and package labeling on the acceptance and purchase intention of craft and industrial beers: a case study. Food Qual. Pref. 86:104139. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104139

de Pelsmacker, P., Janssens, W., Sterckx, E., and Mielants, C. (2005). Consumer preferences for the marketing of ethically labelled coffee. Int. Market. Rev. 22, 512–530. doi: 10.1108/02651330510624363

de Sousa, M. M. M., Carvalho, F. M., and Pereira, R. G. F. A. (2020). Do typefaces of packaging labels influence consumers' perception of specialty coffee? A preliminary study. J. Sens. Stud. 35:e12599. doi: 10.1111/joss.12599

Deliza, R., and MacFie, H. J. H. (1997). The generation of sensory expectation by external cues and its effect on sensory perception and hedonic ratings: a review. J. Sens. Stud. 2, 103–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.1996.tb00036.x

Deroy, O., Crisinel, A.-S., and Spence, C. (2013). Crossmodal correspondences between odors and contingent features: odors, musical notes, and geometrical shapes. Psychonom. Bull. Rev. 20, 878–896. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0397-0

Deroy, O., and Valentin, D. (2011). Tasting shapes: Investigating the sensory basis of cross-modal correspondences. Chemosens. Percept. 4, 80–90. doi: 10.1007/s12078-011-9097-1

Desira, B., Watson, S., Van Doorn, G., Timora, J., and Spence, C. (2020). Happy hour? A preliminary study of the effect of induced joviality and sadness on beer perception. Foods 6:35. doi: 10.3390/beverages6020035

Dijksterhuis, G. (1998). European dimensions of coffee: Rapid inspection of a data set using Q-PCA. Food Qual. Prefer. 9, 95–98. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(97)00037-2

DiPalma, B. (2021). The science behind Keurig crafting Spotify playlists to create a 'unique sensory experience' for coffee drinkers. Yahoo! Finance. Available online at: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/keurig-crafts-spotify-playlists-to-elevate-coffee-drinking-experience-213555068.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAAVvQ1iyY61Nooj_HLxQdtXdIsjXj8wbMAW-w509BWjarOr_W85myx7phRUsrKSUE3DTyFYrJHn3MQyzWI5Y_D_WQvWQey1veqPRSPIql9oSyDMSca9QXtglCt807j5Q8mVucChdvddO7Oj P6UDl8D6CEAMX3iZQ1DSYMlRZndfA

Dmowski, P., and Dabrowska, J. (2014). Comparative study of sensory properties and color in different coffee samples depending on the degree of roasting. Zesz. Nauk. Akad. Mor. Gdyni 84, 28–36.

Feeney, E. M., and Hayes, J. E. (2014). Regional differences in suprathreshold intensity for bitter and umami stimuli. Chemosens. Percept. 7, 147–157. doi: 10.1007/s12078-014-9166-3

Feinstein, A., Hinskton, T., and Erdem, M. (2002). Exploring the effects of music atmospherics on menu item selection. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 5, 3–25. doi: 10.1300/J369v05n04_02

Fenko, A., de Vries, R., and van Rompay, T. (2018). How strong is your coffee? The influence of visual metaphors and textual claims on consumers' flavor perception and product evaluation. Front. Psychol. 9:53. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00053

Fiegel, A., Meullenet, J. F., Harrington, R. J., Humble, R., and Seo, H. S. (2014). Background music genre can modulate flavor pleasantness and overall impression of food stimuli. Appetite 76, 144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.079

Fisk, I. D., Kettle, A., Hofmeister, S., Virdie, A., and Silanes Kenny, J. (2012). Discrimination of roast and ground coffee aroma. Flavour 1:14. doi: 10.1186/2044-7248-1-14

Frayling, T. M., Beaumont, R. N., Jones, S. E., Yaghootkar, H., Tuke, M. A., Ruth, K. S., et al. (2018). A common allele in FGF21 associated with sugar intake is associated with body shape, lower total body-fat percentage, and higher blood pressure. Cell Rep. 23, 327–336. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.070

Fritz, T. H., Brummerloh, B., Urquijo, M., Wegner, K., Reimer, E., Gutekunst, S., et al. (2017). Blame it on the bossa nova: transfer of perceived sexiness from music to touch. J. Exp. Psychol. 146, 1360–1365. doi: 10.1037/xge0000329

Gal, D., Wheeler, S. C., and Shiv, B. (2007). Cross-Modal Influences on Gustatory Perception. Available online at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1030197 (accessed February 16, 2021).

Garber, M. (2012). The future of advertising (will be squirted into your nostrils as you sit on a bus). The Atlantic. Available online at: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/07/the-future-of-advertising-will-be-squirted-into-your-nostrils-as-you-sit-on-a-bus/260283/ (accessed February 16, 2021).

Gatti, E., Spence, C., and Bordegoni, M. (2014). Investigating the influence of colour, weight, & fragrance intensity on the perception of liquid bath soap. Food Qual. Prefer. 31, 56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.08.004

Geel, L., Kinnear, M., and De Kock, H. L. (2005). Relating consumer preferences to sensory attributes of instant coffee. Food Qual. Prefer. 16, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.04.014

Glöss, A. N., Schönbächler, B., Klopprogge, B., D‘Ambrosio, L., Chatelain, K., Bongartz, A., et al. (2013). Comparison of nine common coffee extraction methods: Instrumental and sensory analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 236, 607–627. doi: 10.1007/s00217-013-1917-x

Grosch, W. (1998). Flavour of coffee: A review. Nahrung 42, 344–350. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3803(199812)42:06<344::AID-FOOD344>3.0.CO;2-V

Grosch, W. (2001). “Coffee: Recent developments,” in Chemistry III: Volatile Compounds, eds R. J. Clarke and O. Z. Vitzhum (Oxford: Blackwell Scientific), 68–89. doi: 10.1002/9780470690499.ch3

Guéguen, N., and Jacob, C. (2012). Coffee cup color and evaluation of a beverage's “warmth quality”. Color Res. Appl. 39, 79–81. doi: 10.1002/col.21757

Guetta, R., and Loui, P. (2017). When music is salty: The crossmodal associations between sound and taste. PLoS ONE 12:e0173366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173366

Hall, C. (2012). What's in your daily coffee, and what does your cup say about you? Daily Mail. Available online at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/moslive/article-2135624/Coffee-Whats-daily-grind-does-cup-say-you.html (accessed February 16, 2021).

Hänig, D. P. (1901). Zur Psychophysik des Geschmackssinnes [On the psychophysics of taste]. Philos. Stud. 17, 576–623.

Hansen, J. (2019). Construal level and cross-sensory integration: high-level construal increases the effect of color on drink perception. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 148, 890–904. doi: 10.1037/xge0000548

Hanson-Vaux, G., Crisinel, A.-S., and Spence, C. (2013). Smelling shapes: crossmodal correspondences between odors and shapes. Chem. Senses 38, 161–166. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjs087

Harith, Z. T., Ting, C. H., and Zakaria, N. N. A. (2014). Coffee packaging: consumer perception on appearance, branding and pricing. Int. Food Res. J. 21, 849–853.

Heath, B. (1988). “The physiology of flavour: taste and aroma perception,” in Coffee, Vol. 3, eds R. J. Clarke and R. Macrae (London: Elsevier Applied Science), 141–170.