95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Comput. Sci. , 21 December 2020

Sec. Human-Media Interaction

Volume 2 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2020.600654

This article is part of the Research Topic Urban Play and the Playable City: A Critical Perspective View all 10 articles

Making it work together can be challenging when various stakeholders are involved. Given the context of neighborhoods and cities specifically, stakeholders values and interests are not always aligned. In these settings, to construct long-term and sustaining participatory city-making projects, to make it work together, is demanding. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a design framework for inclusive and participatory city-making. This framework is inspired by the playable city perspective in that it endorses an open, exploratory, and interactive mindset of city actors. An extensive literature review on approaches taken for playful and participatory interventions in local communities provides the foundations for the framework. The review brings forward four pillars on which the framework is grounded and four activities for exploration of the design space for participatory city-making. A case study from The Hague (NL) is used to demonstrate how the framework can be applied to design and analyze processes in which city stakeholders together make it work. The case study analysis complements the framework with various research methods to support researchers, urban planners, and designers to engage with all city stakeholders to create playful and participatory interventions, which are inclusive and meaningful for the local community. The research contributions of this paper are the proposed framework and informed suggestions on how this framework in practice assists city stakeholders to together make it work.

Active citizenship, self-organization, and engagement are high on the agenda of governments worldwide (Kleinhans et al., 2015; Certomà et al., 2017). Engaging citizens in city-making has time and again shown to have positive outcomes on city life in terms of increased trust in government (Cooper et al., 2006) and raised community cohesion (Gaventa, 2004). Citizens are motivated to participate in shaping their environments (Juujärvi and Pesso, 2013; Mulder, 2015) and are more and more included as partners in co-creation of their cities (Dörk and Monteye, 2011; de Lange and de Waal, 2013). Contemporary cities ultimately strive to be designed with contributions of many different city stakeholders (Schroeter, 2012; Fredericks et al., 2015; Golsteijn et al., 2016; Custers et al., 2020; Palacin et al., 2020), often embracing the notion of a smart city with a technology-push in city-making (Nam and Pardo, 2011; Nijholt, 2017).

Although the technology in top-down smart city design regularly focuses on making city life more efficient (Nam and Pardo, 2011), Playable City (Nijholt, 2017) design focuses on the use of smart city technology to engage citizens with their physical space to increase participation in their neighborhood community (Nijholt, 2020). (Serious) Games (Schouten et al., 2017) have successfully been used as a talking tool to facilitate discussion between different stakeholders (Tan and Portugali, 2012) or to include citizens in city-making (Stokes, 2020). Citizens can play an urban planning game to experience decisions and considerations that city planners have to make (Ashtari and de Lange, 2019). Another successful approach has been to place playful interventions in neighborhoods to gather citizen input on city life (Golsteijn et al., 2016; Claes and Moere, 2017; Claes et al., 2017), create discussion on local issues (Schroeter, 2012; Wouters et al., 2014; Hespanhol et al., 2015), or explore alternate designs of the physical space (Fredericks et al., 2015; Golsteijn et al., 2016; Custers et al., 2020). Consideration of the technological, social, and physical structure and networks between people, and of the city, are key to the design of such interventions (Brazier and Nevejan, 2014). These structures and networks define the design space to be considered by all city stakeholders in participatory design of a Playable City.

For people, social and physical, and online and offline realities merge into one experience and understanding of the world (Nevejan, 2007; Nevejan et al., 2018). A clear need exists to include the perspectives of all stakeholders in city-making (Juujärvi and Pesso, 2013; Harding et al., 2015) and the Playable City provides a promising perspective, as it aims to exploit the physical, digital, and social layers of the city to foster citizen engagement (Stokes, 2020). This paper combines insights from these fields to develop a design framework to foster collaboration between stakeholders and integrate digital and physical forms of participation. This framework fills the gap of a city-making design approach in which all stakeholders are able to contribute and their input is equally valued (Harding et al., 2015). Bringing these perspectives together creates a complete picture of a neighborhood with its social and physical structure and networks (Schroeter, 2012; Innocent, 2018). This paper focuses primarily on the physical and social structure of and networks in the neighborhood, as these elements provide starting points for a design that supports presence and trust between city actors (Nevejan and Brazier, 2015a,b). When playful interventions are informed by these social structures and networks, they will better suit the local context and answer the wishes and needs of a neighborhood's inhabitants (Schroeter, 2012; Hespanhol et al., 2015; Cila et al., 2016; Stokes, 2020).

While the importance of including the local community and stakeholders is widely acknowledged, it remains a challenge how to organize such processes (Leminen et al., 2012; Harding et al., 2015; Stokes, 2020). This paper addresses this challenge by developing a framework for inclusive and participatory city-making. The next section further elaborates the gap addressed in this paper: namely the need for a participatory design process in which stakeholders can jointly explore their playable city. A literature review follows and provides the basis for the design framework. This framework distinguishes four types of activities with which to engage all stakeholders in the exploration of the design space of their playable city. Next, the framework is applied to a case-study in Bouwlust, a neighborhood in The Hague (NL), where citizens and professionals are looking for ways to work together to improve liveability and safety. Insights from this case study shed light on the applicability of specific methods for the four types of activities in the framework. The final section of this paper discusses insights from this practical application and directions for future research.

The notion of the Playable City was introduced as a novel perspective on the city: one that is playful, open, exploratory, interactive, and participatory. While several books (e.g., Nijholt, 2017, 2020; Stokes, 2020) and many research articles have been published on this playful perspective, the field is still developing and exploring the notion of a Playable City (Nijholt, 2017, p. 6), its contribution to current thinking (Nijholt, 2017, p. 9), and how the success of Playable Cities can be evaluated (Fisher and Hornecker, 2017; Nijholt, 2017, p. 17). In other words, much work is being (and has still to be) done. Earlier work introduced the notion of playgrounds; physical places in the city where citizens interact on the streets in fun, open, and spontaneous ways (Slingerland et al., 2019a, 2020b). These playful environments, potentially mediated by technology, were designed to create safe spaces for citizens to explore, experience, and reflect on city life (Ferreira et al., 2017). In these spaces, citizens need to trust each other and experience each other's presence (Brazier and Nevejan, 2014; Harding et al., 2015).

To be successful at fostering participation, these spaces need to be designed to embrace the technological, physical, and social aspects of the city (Brazier and Nevejan, 2014). The use of technology in the city seems to become more apparent now that many cities label their city as “smart” (Nijholt, 2017). Technology also plays an important role to mediate the Playable City. Researchers question who should design and use this technology, hence the Playable City (Nijholt, 2017, p. 3). While some research focuses on processes to engage and co-create with city professionals (Tan and Portugali, 2012; Ashtari and de Lange, 2019), other research specifically studies how citizens can be mobilized around local issues to explore possible solutions (Disalvo et al., 2009; Crivellaro et al., 2015; Voida et al., 2015; Innocent, 2018). When local governments design these technologies on their own, citizens have little influence on the design and outcome (Erete, 2015; Le Dantec and Fox, 2015). Technologies created from bottom up, on the other hand, need city resources to scale and sustain (De Koning et al., 2018). Both streams acknowledge that citizens as well as neighborhood professionals, such as community police officers or community workers, possess unique knowledge about the neighborhood and have a solitary perspective on what would be an appropriate intervention (Bowles and Gintis, 2002; Nelson and Baldwin, 2002; Erete, 2015; Cila et al., 2016; Chisholm et al., 2020; Custers et al., 2020). Very few interventions are nevertheless the result of joint efforts between these different neighborhood stakeholders (Harding et al., 2015; De Koning et al., 2018) or focus on a long-term transition (De Koning et al., 2017).

Meanwhile, the whole social, physical, and technological structure of a neighborhood needs to be taken into account to reconsider roles and responsibilities when city actors work together (Nevejan and Brazier, 2015a,b; Golsteijn et al., 2016). Research into living labs provides some insight into how city stakeholders can co-create and which different roles apply (Leminen et al., 2012; Mulder, 2012; Nyström et al., 2014). While this is a good start, living labs are often focused on innovation of public services (Mulder, 2012; Leminen, 2013), not necessarily concerning play or interventions for the urban space. An exception is the work of Juujärvi and Pesso (2013) on urban living labs that takes the neighborhood as the place for developing local solutions. Their work describes how four city actors (civil servants, educational institutions, local firms, and citizens) contribute to urban living labs, and concludes that new methods of co-creation need to be developed (Juujärvi and Pesso, 2013). Research on living labs in general put forward the question of how participation is best facilitated within those labs and how all stakeholders can be included (Leminen et al., 2012; Leminen, 2013; Puerari et al., 2018).

The question remains how a Playable City can be co-created in collaboration with all city stakeholders, resulting in an engaging and empowering participatory place to live. Prior work argues for the need of city actors for increased transparency, influence, and exchange when working together on city-making (De Koning et al., 2018). To our knowledge, current literature lacks overarching guidelines or frameworks for participatory design processes in which multiple stakeholders jointly explore their playable city. Therefore, this paper addresses the following research question: How can all stakeholders be included in exploring the design space of their playable city? The method to answer this question is explained below, after which a framework is presented from literature insights.

The research question is answered by building theory based on a literature study and a case study. The literature study concludes with a design framework that is further grounded by case study research in The Hague (NL).

The literature study was performed by selecting and reviewing papers on urban (playful) interventions from the fields of human–computer interaction and participatory design. The review focuses on generating insights on how multiple stakeholders can jointly explore the design space of their (playable) city. This analysis uses the structure proposed by Hansen et al. (2019), who view participatory design processes through the lens of program theory. For each paper, the following elements are identified: which (co-)design and research activities were used during the research, which actors were included, what was their level of involvement [resonating with mechanisms from Hansen et al. (2019)], and which type of effect the research evoked. The types of effect are categorized as outputs, outcomes, and/or impact. Examples of effects that are categorized as output are design requirements or evaluation results; examples of outcomes are participants gaining new competence or identifying new ways of working; finally, an example of achieved impact is when long-term networks are created or the research results in democratic influence (Hansen et al., 2019). Papers were selected for the review based on the following three criteria: (1) the paper describes an intervention aiming to include citizen opinion; (2) one or multiple actors is involved in the design and/or evaluation of the intervention; (3) the paper describes enough detail of the design and/or evaluation process such that the activities, actors, level of involvement, and effects can be analyzed. The insights of the literature study are integrated in a design framework for participatory city-making presented below in section 5.

To demonstrate and further understand how this framework can guide designing inclusive processes with city stakeholders, the framework is used to analyze a research project that was executed in Bouwlust, a neighborhood in The Hague (NL). The study setup is an embedded, single-case study design, as just one neighborhood is studied and several units of analysis are involved (varying from Bouwlust as a whole to individual citizens) (Yin, 2003). The research in The Hague provides both a unique and representative case. It is unique due to the research setting in which a large variety of methods were used, both digital and face-to-face, to engage different city stakeholders. This unique setting is of interest, even as a single case (Yin, 2003). At the same time, the case is representative because the liveability and safety challenges with which Bouwlust is faced are common for urban socially mixed neighborhoods. Representative cases are relevant to study everyday situations and the resulting insights are assumed to be explanatory for situations in other similar neighborhoods (Yin, 2003). Due to these specific characteristics, this case was selected and found suitable to further inform the theory built from the literature study.

The Bouwlust case was analyzed by first collecting all available documentation and data on the research project. These were reports and slide decks used to present the research to stakeholders, transcripts, and survey data which were collected during the research, and the project website1 that was used to keep local actors informed about the research. The last three authors of this paper were involved in the research project in Bouwlust and hence their experiences also informed the analysis. Each of the research methods used in Bouwlust were described as a first step in the analysis. Following, the first author made an initial analysis by reflecting on the contribution of each of the methods to the aims of the four activities in the framework and determining to which extent the methods fit the four pillars. As a result, the methods were sorted and mapped on each of the activities to which they contributed. This initial outcome was discussed among all authors and further iterated by adding reflections and experiences of the other authors, leading toward the analysis presented in section 6.

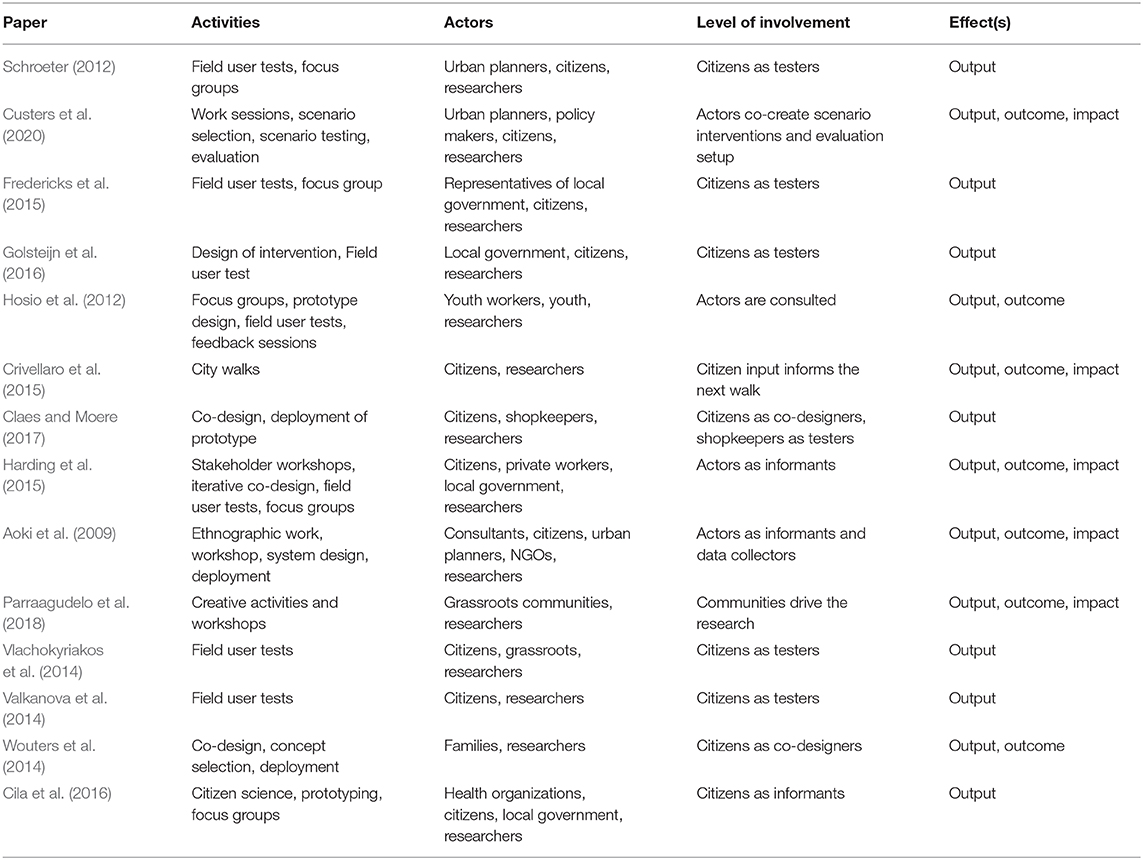

Fourteen papers were selected from the literature search and included in the analysis as shown in Table 1. They are analyzed using the structure explained before, considering which Activities, Actors, Level of involvement, and Effects are described in the papers.

Table 1. Fourteen research projects are analyzed to understand how stakeholders are involved to jointly explore city-making.

A common activity mentioned in all papers is identification of a topic that is of interest to the community involved that is used to mobilize people to participate. In some cases, this so-called matter of concern (Bjögvinsson et al., 2012) is already known to the researchers because of previous engagement with a community (e.g., Vlachokyriakos et al., 2014). In other cases, researchers start with field work to identify a matter of concern for the local community. Researchers explore the area with field visits, desk research, and interviews to discover a topic of concern for the local community and for which they can be mobilized. For example, Crivellaro et al. (2015) started with desk research on the city and then moved into the neighborhoods to contact locals, build relationships, identify issues, and involve professional stakeholders to move forward in addressing those issues. Fieldwork to connect with the context and community is an essential activity in this type of research (Slingerland et al., 2020a).

After the essential fieldwork, different paths unfold depending on the interest and purpose of the research. Four papers test an existing participation tool using the identified matter of concern (e.g., Schroeter, 2012; Valkanova et al., 2014; Fredericks et al., 2015). The main activities then comprise field user tests and focus groups to discuss the results. Other papers (e.g., Hosio et al., 2012; Wouters et al., 2014; Harding et al., 2015; Cila et al., 2016; Claes et al., 2017) deploy co-design activities with city stakeholders before implementing and testing an installation. Playful approaches are introduced as part of the co-design to create an open and creative mindset of the engaged partners. Hespanhol et al. (2015) consider play to be an essential aspect of eliciting community engagement and Brandt (2006) mentions it explicitly as a framework for participation. One step further is to include stakeholders in the evaluation as well (e.g., Aoki et al., 2009; Harding et al., 2015; Parraagudelo et al., 2018; Custers et al., 2020), for them to be able to continue the design process independent of the researchers. Play and games can be used to support these processes, and help stakeholders understand different perspectives (Ashtari and de Lange, 2019).

The extent to which a city community, either citizens or professional, are involved in the research and design varies considerably between papers. In five papers (Schroeter, 2012; Valkanova et al., 2014; Vlachokyriakos et al., 2014; Fredericks et al., 2015; Golsteijn et al., 2016), citizens are only involved as testers and professional actors are consulted for the context and content. In the cases of Fredericks et al. (2015) and Golsteijn et al. (2016), the performance installations were designed by the researchers, and citizens tested them during the field study. The (playful) installations gather citizen input on a specific topic. In some cases, researchers feed these results back to the local organization with whom they partnered (Fredericks et al., 2015; Golsteijn et al., 2016). Citizens often do not receive feedback on what happened with their input, although they do express this need (Vlachokyriakos et al., 2014; Hespanhol et al., 2015).

In five papers (Hosio et al., 2012; Wouters et al., 2014; Harding et al., 2015; Claes and Moere, 2017; Custers et al., 2020), local organizations and citizens are involved as co-designers of a city-making intervention. For example, Hosio et al. (2012) organized several sessions with youngsters to collect requirements for an installation and social networking service to engage youth in city-making. The youth and youth organization were involved in the design process and gave feedback after using the resulting design. Custers et al. (2020) applied a similar approach named “Experimental Evaluation,” in which city stakeholders collectively design, implement, and evaluate improvements for the city. This process not only focuses on co-producing interventions, but also on establishing collective learning with all stakeholders.

The effects these projects can have are categorized into three different levels: output, outcome, and impact. Seven papers remain in the output level, producing insights for designing participation tools. In these cases, the feedback citizens provided in the installation is shared and discussed with the local organization, and in some cases is sometimes visible to citizens themselves. Researchers also reflect with co-design participants on the outcome of the intervention (Hosio et al., 2012). The results are focused on how the installation enabled citizens to participate (Valkanova et al., 2014). Two papers also produce outcomes as a result of the co-design: actors learn new skills and develop competences.

Five paper show examples of participatory processes with effects on the level of impact (Aoki et al., 2009; Crivellaro et al., 2015; Harding et al., 2015; Parraagudelo et al., 2018; Custers et al., 2020). The research of Parraagudelo et al. (2018), for example, has a strong people-centered focus and started with ethnographic work in Colombia to get in contact with community organizations. They slowly built up relationships with formal institutions as well and aimed to help these organizations to co-design on the streets to advance the community. These papers focus on community empowerment and researchers act as facilitators to provide citizens and professionals with the tools and skills to collaborate, identify and discuss local issues, and work toward solutions. Such focus on building capacity and mutual learning is an essential aspect in participatory design work (Bo Andersen et al., 2015; Halskov and Hansen, 2015).

The literature informs the design framework presented in the next section. The first take-away from the literature review is that all papers report on activities to get to know the local context and to connect with key actors. As shown in Table 1 and the analysis, there are significant differences in the extent to which citizens and other stakeholders are involved in city-making processes and the effects these projects have on the local community.

Some papers show examples of participatory processes in which different stakeholders are brought together, treated equally, and given influence on the design process (e.g., Aoki et al., 2009; Crivellaro et al., 2015; Parraagudelo et al., 2018; Custers et al., 2020). These papers affect the community at the level of impact: the local community engages in new relationships and practices, and researchers aim for the community to self-sustain these collaborations. In these cases, the focus of the activities is to facilitate the collaboration process between all actors. This explicitly entails including the stakeholders in the evaluation of these processes and to collectively reflect on the outcomes and next steps.

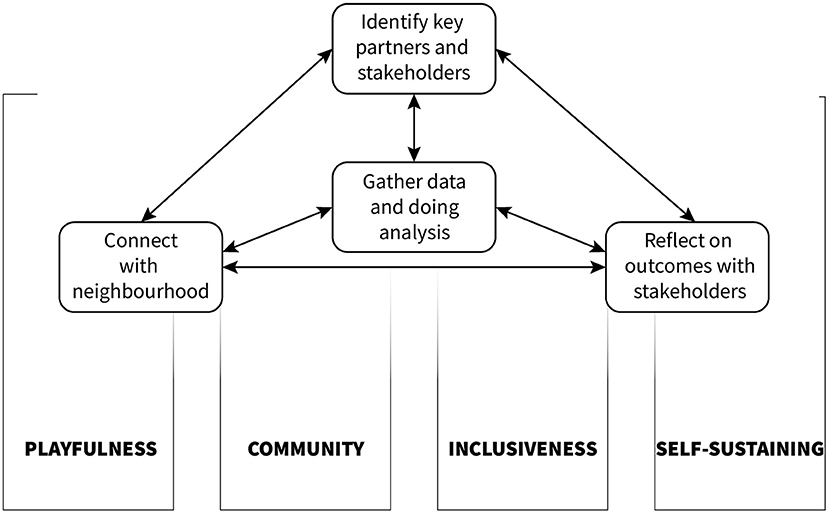

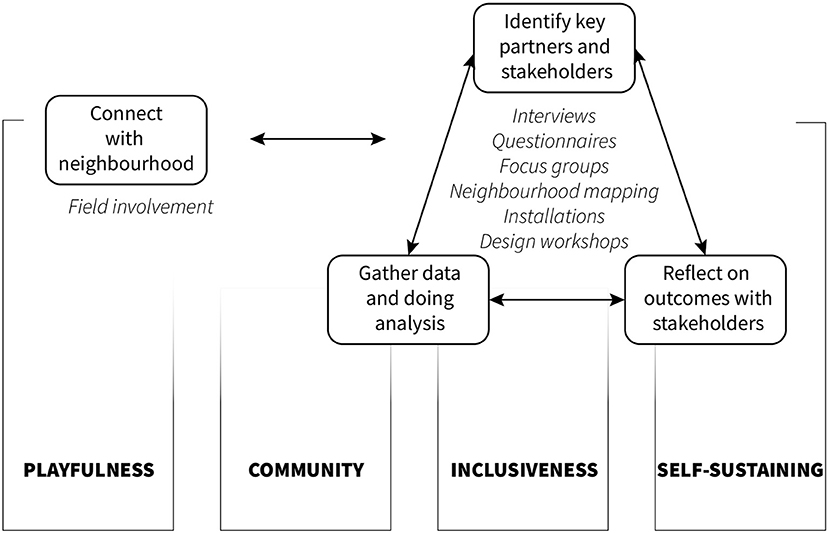

Based on insights from the literature discussed above, the design framework is proposed as depicted in Figure 1. Four types of activities researchers can deploy to explore the design space of a participatory playable city are grounded in four pillars.

Figure 1. The design framework proposed in this paper comprises four activities grounded on four pillars.

The literature review was structured around “activities,” “actors,” “level of involvement,” and “effects,” providing the foundation for the four pillars of the framework. The pillars are presented in a random order, and they are all of equal importance:

• The first pillar is Playfulness, directly related to “Activities.” A playful mindset and setting during (research) activities enable open discussions and exploration between stakeholders.

• The second pillar is Community, directly related to the “Actors” involved, highlighting the central position of local community and context.

• The third pillar is Inclusiveness, directly related to “level of involvement.” Analysis on the “level of involvement” indicated that all actors should be involved and treated equally, and be able to influence the design process.

• The fourth pillar is Self-sustaining, directly related to “Effects.” Analysis of “Effects” showed that a focus on building community capacity enables local actors to continue the initiated design process and related discussions.

The activities analyzed in the literature review are condensed to four activities for inclusive and participatory city-making in the framework (see the boxes in Figure 1):

• Connect with the neighborhood: The purpose of this activity is to understand the social, physical, and technological structure of, and the networks within an area. Becoming familiar with the local context also provides input to identify key partners, build relationships with them, and understand how outcomes of the research can be best brought back to the local community for reflection and evaluation. Methods in this activity include, for example, desk research, observations, neighborhood walks, and interviews.

• Identify key partners and stakeholders: In this activity, key partners and stakeholders are identified in terms of playable city design. Examples of potential partners and stakeholders are local enterprises, police officers, community centers, and grassroots communities because of their perspective on what a playable city should be. Field work is a method to execute this activity: starting by approaching obvious partners and interviewing them to create an overview of social structures and networks within a neighborhood. During such field work, researchers become further acquainted with the area, start to build relationships, and identify opportunities for reflection and discussion on the intermediate outcomes.

• Gather data and doing analysis: This activity is placed in the middle in Figure 1 because it is considered to be the core activity in this framework. Building relationships with all stakeholders is essential to be able to create a fruitful participatory process to design playable cities. The methods used in this activity to collect data should contribute to relationships between city stakeholders and the researchers, but also relationships between the various stakeholders themselves. In this activity, methods include interviews, focus groups, workshops, and prototyping to explore the roles and responsibilities of each stakeholder in the city. The results of this activity are input for the other three.

• Reflect on outcomes with stakeholders: To create a continuous and sustaining participatory practice between city stakeholders, outcomes of the design processes should be made visible and accessible for the community to reflect and discuss. This activity ensures that this happens, making use of physical and digital options to increase accessibility for as many people as possible not only when outcomes are communicated, but also thereafter. Methods and tools used in this activity can be prototypes, interactive installations, digital platforms, and workshops. Communicating the outcomes, making them accessible, and reflecting on them will also contribute to the other activities, possibly triggering new activities.

The order of the activities presented above is not necessarily the order in which they need to be executed: each activity contributes to the other activities and depending on the research aims and resources, multiple iterations of activities may be involved. As shown in Figure 1, these activities are grounded on the four pillars. Communities and inclusiveness play a central role: activities always include stakeholders. Activities should be playful and aim for outcomes that can be self-sustained by the local community. As mentioned before, all activities should consider the technological, social, and physical structures of, and networks within, the local context in design space exploration. This means for the connect with the neighborhood activity, for example, looking at digital platforms the local community uses, such as Facebook groups (technological layer), considering the formal and informal (citizen) groups and initiatives (social layer), and analyzing the physical environment of the local context (physical layer). While these activities in the framework seem to be separate entities, they inform each other as reflected by the arrows between them. As explained below, activities can be fulfilled by multiple methods: interviews can, for example, both be used to become acquainted with a neighborhood as well as to identify key partners and stakeholders.

The next part of this paper uses this framework to analyze the case study presented below. The aim of this analysis is to acquire further understanding of the applicability of the framework, in particular in the applicability of research methods used in each activity. The value of the outcomes of the activities and the extent to which they fulfill the four pillars this framework are evaluated.

The case selected for this paper is a research project that explored the design space for liveability and safety in a participatory process in a neighborhood in The Hague (NL). The local government and police of The Hague identified the neighborhood of Bouwlust as one with a low level of citizen participation for which a new approach was needed. The liveability and safety issues with which citizens are confronted include drug abuse, litter, and youth gangs. Several initiatives have been started in the past by both the local government, the police and citizens to address these issues, often initiated and executed by one of these actors, often for a designated period of time. The research programme this paper analyzes was initiated by these parties to together explore options for inclusive participation to address liveability and safety issues. A research team of Delft University of Technology was invited in this context to, jointly with citizens and other partners, explore the design space of participation in Bouwlust. These methods are outlined in the next section after which the contribution of the methods in each activity is analyzed.

To identify the design space for participation, key actors, their relationships, and their view on participation were explored using eight different methods explained below.

Architect Afaina de Jong2 made an architectural visual analysis of the neighborhood. At different moments during the week she visited Bouwlust and took photographs of the physical environment and the buildings. The architect walked through the neighborhood and explored if and how the physical environment supports social interaction and community building. The architect used the YUTPA framework (Nevejan, 2009) to do her architectural and artistic analyses. YUTPA is the acronym for “being with You in Unity of Time, Place and Action.” The YUTPA framework has been developed to analyze trade-offs in presence design and facilitate discussion about different presence configurations (Nevejan and Brazier, 2015a). To this purpose, each presence design is analyzed along four dimensions: time, place, action, and relation (Nevejan and Brazier, 2011). Different underlying factors are specified for each dimension. The YUTPA dimensions resonate well with the need to acquire insight into the physical (dimensions place and time) and social (dimensions relation and action) structure of and networks within Bouwlust. This framework has also been used in other settings (e.g., Nevejan and Brazier, 2012) to understand the design space for participation. In Bouwlust, the YUTPA analysis, for example, revealed that there are many green areas, such as small parks and playgrounds, but that those are rarely used. Such insights were documented by the architect using photographs taken, and notes made, during the site visits.

For desk research, the team relied highly on municipal documentation, such as urban district plans, safety, and security reports, and neighborhood monitors. The municipality provided reports with evaluations of different participation initiatives that had been performed in the past. The police provided crime reports on, for example, burglaries, robberies, and (domestic) violence. Furthermore, the results of two surveys were provided, one of liveability and safety issues according to the citizens, and one on the digital means available to the citizens. The researchers themselves also analyzed several citizen participation initiatives they found on the internet through, for example, Facebook accounts of the neighborhood and of the community police officer.

Two student groups from three different universities following an MSc programme on Responsible Innovation engaged in a mapping exercise in Bouwlust. They visited Bouwlust for 2 days and asked citizens to map places in the neighborhood where they feel happy. The collected locations and stories of citizens were put on an interactive digital map by the students for everyone to access.

One of the first engagements with the community of Bouwlust were interviews held with five community professionals (four community police officers, one community worker). They played an important role in building up rapport with citizens in Bouwlust. The interviews were semi-structured and focused on three main topics. The first topic was the tasks of the police officer and community worker: their daily routines, which tasks lead to a good feeling (under which circumstances) and which ones cause frustration (under what circumstances). The second topic concerned the interaction and collaboration between professional partners, within the police force and outside with, for example, the Municipality and housing associations with questions, such as How do you negotiate and tune activities? How do you support each other? How do you receive and show appreciation? The third topic was about the way interaction and collaboration with citizens was organized, and its importance with questions, such as How do you interact with citizens? What is important in your work for citizens?

Following the interviews with community professionals, a questionnaire and semi-structured interview guide were developed to address the perspective of citizens. Again, the YUTPA framework (Nevejan, 2009) was used to structure and analyze the interviews with citizens. The questionnaire included one question for each of the factors underlying the four dimensions of the YUTPA framework, resulting in a questionnaire with 16 questions in total. For example, the “duration of engagement” factor was translated to the question “How long do you live here?” The factor “body sense” resulted in the question “Do you feel connected with the people in the neighborhood?” A question about the factor “reciprocity” was rephrased as “Do people help each other in this neighborhood?” As a final example, the “role” factor was translated to the question “Are you as a citizen important for actions that happen in the neighborhood?” The questionnaire addressed the social infrastructure in Bouwlust, to which extent citizens enjoy living in Bouwlust, whether they can take responsibility for the neighborhood, and how much they feel they can collaborate with other citizens or community professionals. Each question required an answer on a scale of 1 (hardly) to 10 (very much).

In a similar vain were questions formulated for the semi-structured interview, using the YUTPA framework, to trigger the respondents to express their experiences of living and participating in the neighborhood. Citizens were informed about the research project and the option to participate, by leaflets that researchers distributed in the neighborhood, in physical mailboxes. These leaflets also offered the option for citizens to go to a website and answer some questions, instead of having a physical interview. The researchers set themselves up in a mobile unit for a few days near the shopping center in Bouwlust and approached citizens on the street inviting them to either fill out the questionnaire on paper or to participate in a more elaborate interview. This setting is shown in Figure 2. In total, 22 citizens participated in the physical interview that resulted in rich qualitative stories and experiences of citizens to complement the questionnaire outcomes. The questionnaire was filled in by 72 citizens.

Figure 2. The researchers invited citizens for an interview or to fill out the questionnaire in the mobile unit.

Participants for the citizen focus groups were recruited by visiting locations where citizens come together and approaching citizens to participate. For the focus groups, primary schools were visited to invite mothers to discuss their situations with the researchers. The researchers also visited the community center to talk to other citizens. In total 11 persons participated in the discussions. The topics addressed, and questions asked, were similar to the semi-structured interviews with citizens in the mobile unit.

To understand which circumstances in Bouwlust (e.g., emerging safety issues) could foster citizens to connect with each other and community professionals, an installation was setup for 2 days in the neighborhood, 1 day close to a mosque, and 1 day near the shopping center. This installation confronted citizens with specific circumstances, for example an increase of burglaries, and researchers asked citizens to respond, in terms of whom they would contact and in what way (face-to-face, email, phone, etc.). The answers provided by citizens gave further insight into the social structure of, and networks within Bouwlust and the possibilities to build and extend relationships between the various stakeholders.

As a final activity, a design workshop was organized in which citizens and community police officers discussed the outcomes of the other activities and explored design options for Bouwlust. Twelve citizens, two community police officers, and a community worker gathered on an evening in the community center to co-design solutions for the three problems most frequently addressed in earlier activities: loiterers, litter, and burglaries. The participants were triggered to think of solutions from three perspectives, from the perspective of the most likely responsible stakeholder, such as the police or city council, from the perspective of social institutions, such as schools, mosques, health care, and shops, and from the perspective of physical and digital installations, such as apps, sensors, and street light. Solutions varied from larger garbage bins, improving locks on houses, via social influencing through school, church and mosque, understanding what loiterers need, to digital apps to report and inform citizens and government, and placing cameras and sensors at crucial places.

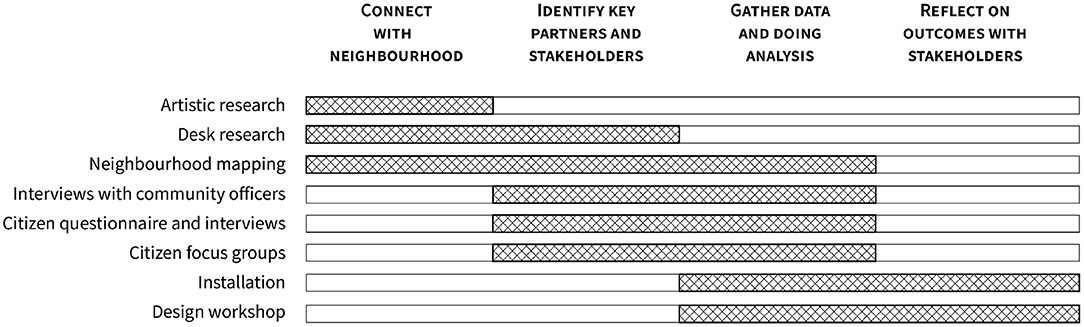

This section analyzes and outlines to what extent the methods helped to fulfill the aim of each of the activities, grounded on the four pillars. An overview of this analysis is shown in Figure 3. It depicts the relation between the research methods used during this case study and the activities of the earlier proposed design framework.

Figure 3. An overview of how the applied methods in Bouwlust fit within the four activities from the proposed framework.

The aim of this activity is to acquire insight into the social, physical, and technological structure of the neighborhood. Initial involvement with the field through the artistic research, desk research, and neighborhood mapping was used in the case study as part of this activity. The artistic research was valuable for the researchers to develop a sense for Bouwlust, mostly in terms of the physical structure. For example, one observation was that many signs and fences restrict how public places are used in the neighborhood and that the community center building itself is visually closed off from the street (see Figure 4). As in the previous activities, the YUTPA framework (Nevejan, 2009) was used to structure the analysis of the observations and to interpret the photographs taken.

The desk research provided insight into demographics of Bouwlust, participation initiatives, and the liveability and safety problems citizens experience. The documents helped to understand the history of the neighborhood; how it has developed over the years into the very diverse and dynamic community it now is. An important insight in terms of social structure was, for example, that citizens, on average, live in Bouwlust for just 3 years. This high turnover of citizens complicates a general neighborhood sense of community. There is, however, a huge variation in the number of years citizens live in Bouwlust: from just 1 year to extremes up to 40 years. In terms of becoming acquainted with Bouwlust, the field visits were useful to get to know the important places in the neighborhood (such as the community center), while the desk research provided insights on what people in Bouwlust care about, which participation initiatives exist(ed), and the way the neighborhood is structured in terms of demographics. The methods helped to paint a rather conceptual picture of Bouwlust as there was limited engagement with the people whom live or work in Bouwlust. The interviews, focus groups, and installation used in the other activities provided much more insight into the social structure of, and networks in the neighborhood.

The aim of this activity is to acquire insight into the main actors in a neighborhood in terms of participation. The desk research contributed to this activity, complemented with the interviews, questionnaires, and focus groups with several of the obvious stakeholders. As in this research programme, the researchers were invited by the local police and government to explore citizen participation, these three stakeholders were an obvious starting point to identify other actors. The four methods used in this activity (see Figure 4) allowed to identify actors from different perspectives. Throughout these four methods, and the ones used beyond this activity, other key actors were identified. Insights in Bouwlust became more detailed and nuanced. This resulted in the notable insight that the notion of a key stakeholder is very dependent on context. For example, in some cases citizens are considered to be a single (type of) stakeholder in this context, while the desk research documents, citizen interviews and questionnaire showed that citizens organize themselves in communities according to cultural or ethnic background. For example, one citizen said: “Everybody is only connected to their own group, their own culture, and not with other people.” Citizens can, in this context, not be considered to be a single stakeholder, but rather as multiple stakeholders who are organized based on culture. People are part of different cultures, around schools, religion, sports, housing blocks for example. Culture is used here in a broad sense and reflects a multiplicity of identities (de Jong, 2020).

The key stakeholders identified by the community police officers included the municipality, local care institutions, and housing corporations. Citizens did not make this distinction: they grouped these various governmental actors together as the community police officer stakeholder. This became clear during the focus groups and citizen interviews, in which citizens indicated that they reach out to their community police officers when they need help, independent of the issue. One of the community police officers stated: “We fill many gaps. We are in contact with schools, shops, care institutions and youth work.” Another one said: “These professional partners come to me, [...] They call me to ask to go by one of their clients from which they haven't heard in a while. In these cases I decide if this is part of my job or if it's the partner's responsibility.” The officer is the first contact point for most citizens when they need help and also for the professional organizations when they want to reach citizens. The three methods in this activity taught that there are different perceptions on key stakeholders and that for Bouwlust, the main interaction is between the community police officer and different groups of citizens. The focus groups stimulated an open and exploratory discussion between different citizens. The discussions were dynamic and interactive, contributing to a playful ambience. The research showed every specific and important social role these community police officers have, according to the interviewed residents.

This activity comprised many methods as shown in Figure 3. The interviews, questionnaires, and focus groups with citizens and community officers contributed to building relationships needed to gather data and analyze Bouwlust. Neighborhood mapping, the installation, and design workshop supported this activity as well. This variation of methods enables city stakeholders to engage at different moments, as it suits them. They were playful in the way data were collected, using traditional methods (interviews, questionnaires, and focus groups) and methods that fostered creativity, openness, and interaction (neighborhood mapping, installation, and design workshop). These methods created an iterative cycle to connect more and more with the neighborhood and deepen the relationships with stakeholders. City stakeholders simultaneously became familiar with the research project, decreasing the effort to convince stakeholders to participate. Strategic locations to attract a variety of citizen groups were selected: visiting schools, shopping areas, mosques, and playgrounds. The fact that these methods were mainly conducted out on the streets, using a visible mobile unit or installation, lowered the barrier for stakeholders to talk to the researchers and thus relaxed the effort to collect data.

On the other hand, this activity aims to invest in the relationships between the city stakeholders themselves. The design workshop brought citizens, police officers, and community workers together to discuss outcomes and collaboratively design solutions for three frequently mentioned problems in the neighborhood. Different stakeholders collaborated on a commonly felt problem, which contributed to their shared feeling and relationship. The design workshop was playful because it fostered an open and exploratory mindset of participants, as they were asked to consider perspectives of other stakeholders, social institutions, and physical/digital installations when coming up with solutions.

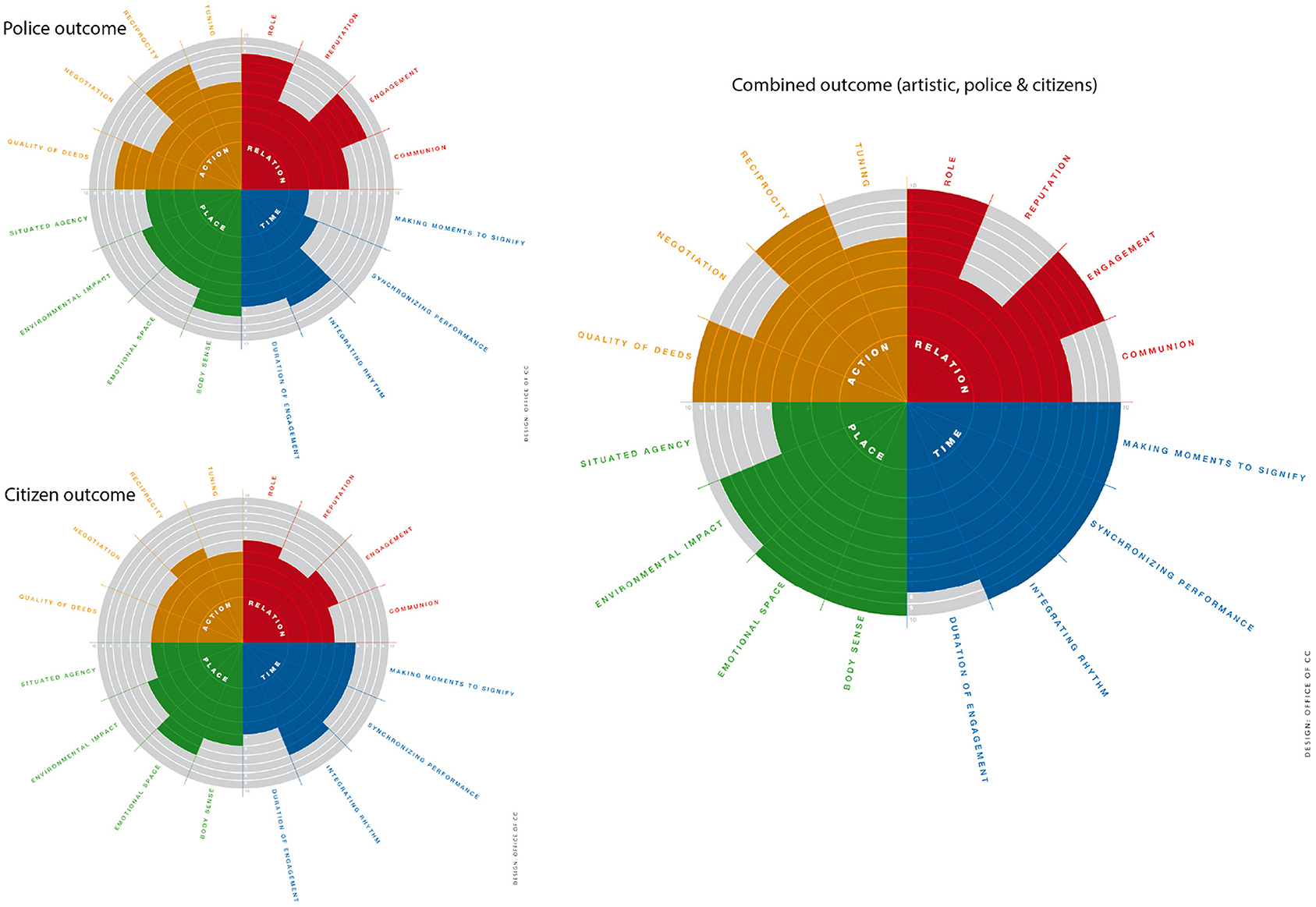

The aim of this activity is to find out where and how outcomes of the other activities can be fed back to the city stakeholders for reflection and discussion. In the design workshop, the results so far were summarized and presented to the participants. The main reason for this is to validate whether the participants recognize these results and are willing to adopt them further on in the process. To this end, the outcomes of the interviews and questionnaires were mapped on the YUTPA framework to understand the relationships between the different actors and how they perceive each other. This is illustrated in Figure 5, showing the YUTPA outcomes for citizens and community police officers. These graphs highlight which factors are supported, for which support is lacking, and how this differs between citizens and community police officers. This tool illuminates which factors have a basis and which relationships between the various city stakeholders can be developed. The right graph shows the YUTPA result when all graphs are combined, visualizing the potential design spaces for participation in Bouwlust. The factors that score higher than 5 on this combined graph are considered to indicate a potential design space.

Figure 5. Left part shows the difference between the YUTPA outcomes for citizens and police officers. Right graph is the result of combing all YUTPA analyses to identify possible design spaces. Scores higher than 5 show potential for design.

In Bouwlust, neighborhood mapping, an installation, and the design workshop were used to fulfill this aim. In addition, a website was made available for citizens and other stakeholders to be informed on the progress of the research and intermediate results3. Asking citizens to indicate which places in Bouwlust make them happy resulted in a list of locations that might be appropriate to disseminate outcomes. The installation provided insight into motivators for citizens to engage with their neighbors and neighborhood and other city stakeholders. The topic of safety in Bouwlust was identified as a topic that motivates citizens to contribute to neighborhood initiatives for a longer period of time.

As result of the research it became apparent that the time dimension of the YUTPA framework offers the best design solution space for enhancing social safety in Bouwlust. The first factor that can be enhanced in the time dimension is integrating rhythm. Many residents have reported that sharing activities like walking the dog, meeting at the school yard, and shopping at the same time make it easier to engage with a basic trust among one another. Rhythms of daily life affect the sense of social safety in a neighborhood. The second factor that many residents agreed upon is the fact that the Bouwlust lost “moments to signify.” In a neighborhood both the history of the place as well as a yearly festival for example, or a monthly newsletter give people a shared sense of where they are. The sharing of meaning, the actively being involved with contributing to this meaning of and in a neighborhood, enhances the sense of social cohesion and the sense of social safety as result. The longing for more meaning and active engagement with neighborhood histories is visible in local social media activities, but is not yet visible in the physical environment.

Analysis of the case study in Bouwlust provides insight into which methods are essential within the design framework proposed in this paper. To untangle participatory design processes and methods is a challenge (Sawhney and Tran, 2020): they are not easily separated because they influence each other constantly. To this end, researchers can move back and forth between the four activities of our framework using methods that can contribute to multiple activities at the same time as depicted in Figure 6. Such an iterative process is needed as the neighborhood is also continually changing. For example, the analysis showed that key partners and stakeholders are fluid, depending on who and when you ask. Going through multiple iterations using various methods also allows to step by step deepen the understanding and connection with the context, and to continuously inform next steps on what was learned. The resulting account to use different types of methods and to iterate within and between the four activities are the two main topics for discussing the analysis.

Figure 6. The design framework suggests a sequence of activities and which methods to be used in them.

Eight different methods were used to explore participation with various stakeholders in Bouwlust. These methods purposefully offered neighborhood actors multiple ways to participate in the research. Citizens could engage in a way that suited their availability and commitment. The benefit of providing different modes or mediums to tailor participation was also highlighted in case studies on grassroots citizen communities (Slingerland et al., 2019b). The findings in Bouwlust show as well that multiple methods should be used in this kind of work to provide actors distinct ways to be involved and provide input to the research.

One activity in which many distinct methods were used was gather data and doing analysis. While the mobile unit for the citizen interviews received a lot of attention because it was placed at a strategic location where many people frequent, digital engagement on the website was considerably lower. Engagement, in this case, was measured in terms of how many citizens responded. These two channels nonetheless enabled different types of citizens to participate: ones whom do not find their way to a website or app and enjoy talking to a researcher, and ones whom prefer to give their feedback at home using their computer at a time that suits them. The YUTPA framework was helpful to integrate the insights from the various methods providing a generic coding scheme for the analysis of the variety of results, enabling comparison needed to identify design spaces for participation in the neighborhood.

The four activities of the proposed framework were initially introduced without a pre-defined order. The case study in Bouwlust, however, suggests a preferred sequence of activities and methods. This sequence suggestion is added to Figure 6. Initial field involvement is an essential first step before any of the other methods can be applied. This initial step informs the researchers on which locations in the neighborhood people can be found and which people or parties should be considered in the furthering research. Interviews with citizens or city officials, for example, will not be less informative to researchers if they do not first engage with desk research and field visits to know which topics to address in the interviews. Interactive installations could also be used to become acquainted with the neighborhood, but researchers first need to know which are crowded locations to strategically place an installation. The prominent presence of such initial field work in seminal literature (e.g., Aoki et al., 2009; Crivellaro et al., 2015; Parraagudelo et al., 2018; Custers et al., 2020) confirms that field involvement as part of connecting with the neighborhood is a critical first step in the proposed framework.

Following the case study analysis, connecting with the neighborhood seems to be the activity that needs to be executed first before the other three activities can be done. In contrast, the other three activities do not presume a specific sequence and continue to inform each other and the first activity as well. In the case of Bouwlust, results were mostly made visible to the community during the final stages of the research. Some methods (e.g., the installation) could have been applied already earlier to visualize intermediate outcomes. At the same time, the installation in Bouwlust was, for example, designed using insights from the interviews and questionnaire. The method sequence needs to be carefully considered, to find an appropriate chain of activities that build on each other's outcomes and disseminates these outcomes to the local community. A method, such as focus groups is also suitable to feed results back and discuss them with the community to inform further research activities (Pickering et al., 2012). Such a process, where directions and outcomes become apparent on the go, requires a lot of flexibility from researchers, participants, and funders, which is not always an option.

The design framework presented in this paper requires all activities to build on the four pillars: community, self-sustaining, inclusiveness, and playfulness. These pillars serve as a checklist when researchers are setting up their research design, selecting their methods for engaging with the various stakeholders. For the community pillar, this requires researchers to keep the local community in mind, even when they do not directly engage with them. When starting with desk research, for example, researchers should not only consider formal documents produced by professional actors, but also check for informal citizen networks and platforms where the local community might meet. In terms of self-sustaining, the methods selected should contribute to the local actors being able to independently continue exploration of participation in the neighborhood. To this end, researchers should not aim to solve problems of the community, but rather support the various stakeholders in collaboratively taking this up. The pillar of inclusiveness is fulfilled when researchers use different kinds of methods for people to participate on their terms and in a way that suits them. Method variety in terms of digital or physical participation as well as required time commitment are ways of achieving this. The playfulness pillar entails the need for researchers to offer creative and open-ended ways of engaging with the local community. This increases pleasure for participants, but also creates an environment for exploration and reflection with stakeholders.

This paper proposes a design framework to support city actors to make it work together, despite their sometimes conflicting values and interests. The framework is inspired by the playable city perspective. Based on insights from literature, the framework enables the construction of long-term and sustaining participatory city-making projects, in which all stakeholders are able to contribute and their input is equally valued. The foundation of the framework ensures an open and exploratory mindset of all actors through four pillars: community, self-sustaining, inclusiveness, and playfulness. Furthermore, the framework suggests to structure an exploration of the design space for participatory city-making around four activities. The value of the framework is demonstrated through a case study, in which further insights are gathered on the four activities and possible corresponding methods. The case study in Bouwlust (a neighborhood in The Hague, NL) was analyzed using the framework to understand which methods support city actors to together make it work.

The case study lasted in Bouwlust for 2 years in collaboration with the police and local government. Eight different methods were part of the study to involve community professionals and citizens in thinking about improving the liveability and safety in Bouwlust. Using the framework to analyze the city-making process in Bouwlust resulted in valuable and relevant insights into how such processes can be best organized. The first insight was that method variety in each of the activities is needed to offer city stakeholders multiple ways to get involved, using digital channels or real-life engagements, with various levels of commitment. The second insight was the activity connect with the neighborhood needs to be done before the other three. The outcome from this activity informs the activities to identify key partners, gather data and doing analysis, and make outcomes visible and accessible. While untangling participatory design processes can be difficult (Sawhney and Tran, 2020), the framework presented in this paper demonstrated its value to do just that, to fill the gap of developing playable city design approaches that are inclusive and meaningful for the local community. Current research extends this research to focus on the development of a data approach to enhance rhythms in neighborhoods (2018–2023) in urban environments (Nevejan et al., 2018). Current research also explores a variety of interfaces in which online local activity becomes visible in the physical environment where the stories and data are gathered in a playful endeavor (Suurenbroek et al., 2019). Further analysis of other playable participatory case studies using this framework is one of the directions of our future work and aims to strengthen the contribution of this promising framework to the field of playable cities.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by HREC TU Delft. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

GS conducted the literature review and together with SL, MH, and FB developed the proposed framework. MH and CN were involved in the field work in Bouwlust in each of the eight methods described. GS, SL, MH, CN, and FB conducted the analysis of the case study using the proposed framework, wrote, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding for the BART project (www.bartportal.nl) was provided by a consortium of partners including the Municipality of the Hague, the National Police, Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, CGI, TNO, TUDelft, and TIGNL.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors were very grateful to all citizens, professional stakeholders of Bouwlust, and the BART consortium for their participation. The authors also thank architect Afaina de Jong for her contribution to several of the participatory design research activities in Bouwlust, and the students for their work on mapping Bouwlust in collaboration with its citizens.

1. ^See http://vital.gingerresearch.net (last accessed October 5, 2020).

2. ^Afaina was part of the research team.

3. ^See http://vital.gingerresearch.net (last accessed October 6, 2020).

Aoki, P. M., Honicky, R. J., Mainwaring, A., Myers, C., Paulos, E., Subramanian, S., et al. (2009). “A vehicle for research: using street sweepers to explore the landscape of environmental community action,” in Proceedings of Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Boston, MA), 375–384. doi: 10.1145/1518701.1518762

Ashtari, D., and de Lange, M. (2019). Playful civic skills: a transdisciplinary approach to analyse participatory civic games. Cities 89, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.01.022

Bjögvinsson, E., Ehn, P., and Hillgren, A. (2012). Design things and design thinking: contemporary participatory design challenges. Des. Issues 28, 101–116. doi: 10.1162/DESI_a_00165

Bo Andersen, L., Danholt, P., Halskov, K., Brodersen Hansen, N., and Lauritsen, P. (2015). Participation as a matter of concern in participatory design. Codesign 11, 250–261. doi: 10.1080/15710882.2015.1081246

Bowles, S., and Gintis, H. (2002). Social capital and community governance. Econ. J. 112, F419–F436. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00077

Brandt, E. (2006). “Designing exploratory design games: a framework for participation in participatory design?” in Proceedings of the Ninth Participatory Design Conference 2006 (Trento), 57–66. doi: 10.1145/1147261.1147271

Brazier, F. M., and Nevejan, C. (2014). “Vision for participatory systems design,” in 4th International Engineering Systems Symposium (CESUN 2014) (Hoboken, NJ).

Certomà, C., Dyer, M., Pocatilu, L., and Rizzi, F. (2017). Citizen Empowerment and Innovation in the Data-Rich City. Cham: Spinger Nature.

Chisholm, C. J., Falk, C. A., and Kozak, L. E. (2020). “Sticks, ropes, land: confronting colonial practices in public space design,” in Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020–Participation(s) Otherwise–Vol 2 (PDC '20: Vol. 2) (Manizales: ACM), 63–67.

Cila, N., Jansen, G., den Broeder, L., Groen, M., Meys, W., and Kröse, B. (2016). “Look! A healthy neighborhood: means to motivate participants in using an app for monitoring community health,” in Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (San Jose, CA: ACM), 889–898. doi: 10.1145/2851581.2851591

Claes, S., Coenen, J., and Moere, A. V. (2017). “Empowering citizens with spatially distributed public visualization displays,” in DIS'17 Companion: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference Companion Publication on Designing Interactive Systems (Edinburgh), 213–217. doi: 10.1145/3064857.3079148

Claes, S., and Moere, A. V. (2017). “The impact of a narrative design strategy for information visualization on a public display,” in DIS'17: Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing Interactive Ssytems (Edinburgh), 833–838. doi: 10.1145/3064663.3064684

Cooper, T., Bryer, T. A., and Meek, J. W. (2006). Citizen-centred collaborative public management. Public Admin. Rev. 66, 76–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00668.x

Crivellaro, C., Comber, R., Dade-Robertson, M., Bowen, S. J., Wright, P., and Olivier, P. (2015). “Contesting the city: enacting the political through digitally supported urban walks,” in Proceedings of Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Seoul), 2853–2862. doi: 10.1145/2702123.2702176

Custers, L., Devisch, O., and Huybrechts, L. (2020). “Experiential evaluation as a way to talk about livability in a neighborhood in transformation,” in Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020–Participation(s) Otherwise–Vol 2 (PDC '20: Vol. 2) (New York, NY: ACM), 114–118. doi: 10.1145/3384772.3385128

de Jong, A. (2020). “Multiplicity of other,” in Values for Survival eds C. Nevejan and H. A. Farè (Rotterdam: Het Nieuwe Institituut), 85–97.

De Koning, J., Puerari, E., Mulder, I., and Loorbach, D. (2017). Ten Types of Emerging City Makers. Oslo: SDA Systemic Design Association.

De Koning, J. I., Puerari, E., Mulder, I. J., and Loorbach, D. A. (2018). “Design-enabled participatory city making,” in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation, ICE/ITMC 2018–Proceedings (Stuttgart), 1–9. doi: 10.1109/ICE.2018.8436356

de Lange, M., and de Waal, M. (2013). Owning the city: new media and citizen engagement in urban design. First Monday 18, 1–13. doi: 10.5210/fm.v18i11.4954

Disalvo, C., Louw, M., Coupland, J., and Steiner, M. (2009). “Local issues, local uses: tools for robotics and sensing in community contexts,” in ACM Conference on Creativity and Cognition (Berkeley, CA), 245–254. doi: 10.1145/1640233.1640271

Dörk, M., and Monteye, D. (2011). “Urban co-creation: envisioning new digital tools for activism and experimentation in the city,” in Proceedings of the CHI Conference (Vancouver, BC).

Erete, S. L. (2015). “Engaging around neighborhood issues,” in Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (Vancouver, BC), 1590–1601. doi: 10.1145/2675133.2675182

Ferreira, V., Anacleto, J., and Bueno, A. (2017). “Designing ICT for thirdplaceness,” in Playable Cities: Gaming Media and Social Effects, ed A. Nijholt (Singapore: Springer), 211–233. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-1962-3_10

Fisher, P. T., and Hornecker, E. (2017). “Creating shared encounters through fixed and movable interfaces,” in Playable Cities: The City as a Digital Playground, ed A. Nijholt (Singapore: Springer), 163–185. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-1962-3_8

Fredericks, J., Tomitsch, M., Hespanhol, L., and McArthur, I. (2015). “Digital pop-up: investigating bespoke community engagement in public spaces,” in OzCHI 2015: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Australian Special Interest Group for Computer Human Interaction (Melbourne, VIC), 634–642. doi: 10.1145/2838739.2838759

Gaventa, J. (2004). Representation, Community Leadership and Participation: Citizen Involvement in Neighbourhood Renewal and Local Governance. Technical Report July, Office of Deputy Prime Minister.

Golsteijn, C., Gallacher, S., Capra, L., and Rogers, Y. (2016). “Sens-Us: designing innovative civic technology for the public good,” in Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (Brisbane, QLD: ACM), 39–49. doi: 10.1145/2901790.2901877

Halskov, K., and Hansen, N. B. (2015). The diversity of participatory design research practice at PDC 2002–2012. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 74, 81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.003

Hansen, N. B., Dindler, C., Halskov, K., and Schouten, B. (2019). “How participatory design works: mechanisms and effects,” in OZCHI'19: Proceedingsof the 31st Australian Conference on Human-Computer-Interaction (Fremantle, WA), 30–41. doi: 10.1145/3369457.3369460

Harding, M., Knowles, B., Davies, N., and Rouncefield, M. (2015). “HCI, civic engagement & trust,” in Proceedings of Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Seoul), 2833–2842. doi: 10.1145/2702123.2702255

Hespanhol, L., Tomitsch, M., McArthur, I., Fredericks, J., Schroeter, R., and Foth, M. (2015). “Vote as you go: blending interfaces for community engagement into the urban space,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Communities and Technologies–C&T '15 (Limerick), 29–38. doi: 10.1145/2768545.2768553

Hosio, S., Kostakos, V., Kukka, H., Jurmu, M., Riekki, J., and Ojala, T. (2012). From school food to skate parks in a few clicks: using public displays to bootstrap civic engagement of the young. Pervasive 7319, 425–442. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-31205-2_26

Innocent, T. (2018). “Play about place: placemaking in location-based game design,” in Proceedings of Media Architecture Biennale 2018 Conference (MAB'18) (Beijing), 7. doi: 10.1145/3284389.3284493

Juujärvi, S., and Pesso, K. (2013). Actor roles in an urban living lab: what can we learn from Suurpelto, Finland? Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 3, 22–27. doi: 10.22215/timreview/742

Kleinhans, R., Van Ham, M., and Evans-Cowley, J. (2015). Using social media and mobile technologies to foster engagement and self-organization in participatory urban planning and neighbourhood governance. Plan. Pract. Res. 30, 237–247. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2015.1051320

Le Dantec, C. A., and Fox, S. (2015). “Strangers at the gate: gaining access, building rapport, and co-constructing community-based research,” in Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (Vancouver, BC: ACM), 1348–1358. doi: 10.1145/2675133.2675147

Leminen, S. (2013). Coordination and participation in living lab networks. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 3, 5–14. doi: 10.22215/timreview/740

Leminen, S., Westerlund, M., and Nyström, A.-G. (2012). Living labs as open-innovation networks. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2, 6–11. doi: 10.22215/timreview/602

Mulder, I. (2012). Living labbing the Rotterdam way: co-creation as an enabler for urban innovation co-creation as an enabler for urban innovation. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2, 39–43. doi: 10.22215/timreview/607

Mulder, I. (2015). “Opening up: towards a sociable smart city,” in Citizen's Right to the Digital City: Urban Interfaces, Activism, and Placemaking, eds M. Foth, M. Brynskov, and T. Ojala (Singapore: Springer), 161–173. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-919-6_9

Nam, T., and Pardo, T. A. (2011). “Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people, and institutions,” in The Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research (College Park, MD), 282–291. doi: 10.1145/2037556.2037602

Nelson, S., and Baldwin, N. (2002). Comprehensive neighbourhood mapping: developing a powerful tool for child protection. Child Abuse Rev. 11, 214–229. doi: 10.1002/car.741

Nevejan, C. (2007). Presence and the design of trust (Ph.D. thesis), University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Nevejan, C. (2009). Witnessed Presence and the YUTPA framework. Psychnol. J. 7, 59–76. Available online at: http://sprouts.aisnet.org/9-21

Nevejan, C., and Brazier, F. (2011). “Witnessed presence in merging realities in healthcare environments,” in Advanced Computational Intelligence Paradigms in Healthcare 5, Volume 326 of Studies in Computational Intelligence, eds S. Brahnam and L. Jain (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg), 201–227. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-16095-0_11

Nevejan, C., and Brazier, F. M. (2012). Granularity in reciprocity. AI Soc. 27, 129–147. doi: 10.1007/s00146-011-0332-8

Nevejan, C., and Brazier, F. M. (2015a). “Design for the value of presence,” in Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design, eds J. van den Hoven, P. Vermaas, and I. van de Poel (Dordrecht: Springer), 403–430.

Nevejan, C., and Brazier, F. M. (2015b). “Presence and participation: values for designing complex systems,” in Handbook of Ethics, Values, and Technological Design, eds J. van den Hoven, P. Vermaas, and I. van de Poel (Dordrecht: Springer), 403–430.

Nevejan, C., Sefkatly, P., and Cunningham, S. (2018). City Rhythm, Logbook of an Exploration. Delft: Delft University of Technology.

Nijholt, A. (2017). Playable Cities: The City as a Digital Playground. Singapore: Springer Science+Business Media.

Nyström, A.-G., Leminen, S., Westerlund, M., and Kortelainen, M. (2014). Actor roles and role patterns influencing innovation in living labs. Ind. Market. Manag. 43, 483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.12.016

Palacin, V., Nelimarkka, M., Reynolds-Cuellar, P., and Becker, C. (2020). “The design of pseudo-participation,” in Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020–Participation(s) Otherwise–Vol 2 (PDC '20: Vol. 2) (Manizales: ACM), 40–44. doi: 10.1145/3384772.3385141

Parraagudelo, L., Choi, J. H., Foth, M., and Estrada, C. (2018). Creativity and design to articulate difference in the conflicted city: collective intelligence in Bogota's grassroots organisations. AI Soc. 33, 147–158. doi: 10.1007/s00146-017-0716-5

Pickering, J., Kintrea, K., and Bannister, J. (2012). Invisible walls and visible youth: territoriality among young people in British cities. Urban Stud. 49, 945–960. doi: 10.1177/0042098011411939

Puerari, E., de Koning, J. I., von Wirth, T., Karré, P. M., Mulder, I. J., and Loorbach, D. A. (2018). Co-creation dynamics in urban living labs. Sustainability 10, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/su10061893

Sawhney, N., and Tran, A.-T. (2020). “Ecologies of contestation in participatory design,” in Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020–Participation(s) Otherwise–Vol 1 (PDC '20: Vol. 1) (Manizales: ACM), 172–181. doi: 10.1145/3385010.3385028

Schouten, B., Ferri, G., De Lange, M., and Millenaar, K. (2017). “Games as strong concepts for city-making,” in Playable Cities: Gaming Media and Social Effects, ed A. Nijholt (Singapore: Springer), 23–45. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-1962-3_2

Schroeter, R. (2012). “Engaging new digital locals with interactive urban screens to collaboratively improve the city,” in Proceedings of the ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW '12) (Seattle, WA), 227–236. doi: 10.1145/2145204.2145239

Slingerland, G., Lukosch, S., and Brazier, F. (2020a). “Engaging children to co-create outdoor play activities for place-making,” in Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020–Participation(s) Otherwise–Vol 1 (PDC '20: Vol. 1) (Manizales: ACM), 44–54. doi: 10.1145/3385010.3385017

Slingerland, G., Lukosch, S., Comes, T., and Brazier, F. (2020b). Exploring design guidelines for fostering citizen engagement through information sharing: Local playgrounds in The Hague. EAI Endorsed Trans. Serious Games 18:e2. doi: 10.4108/eai.13-7-2018.162636

Slingerland, G., Lukosch, S. G., Comes, T., and Brazier, F. M. (2019a). “Exploring requirements for joint information sharing in neighbourhoods: local playgrounds in The Hague,” in Interactivity, Game Creation, Design, Learning and Innovation–7th EAI International Conference, ArtsIT 2018, and 3rd EAI International Conference, DLI 2018, ICTCC2018, Proceedings, eds A. Brooks, E. Brooks, and C. Sylla (Braga: Springer), 306–315. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-06134-0_35

Slingerland, G., Mulder, I., and Jaskiewicz, T. (2019b). “Join the park! Exploring opportunities to lower the participation divide in park communities,” in Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Communities Technologies–Transforming Communities (Milan: ACM), 131–135. doi: 10.1145/3328320.3328382

Stokes, B. (2020). Locally Played: Real-World Games for Stronger Places and Communities, 1st Edn. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Suurenbroek, F., Nio, I., and De Waal, M. (2019). Responsive Public Spaces: Exploring the Use of Interactive Technology in the Design of Public Spaces. Amsterdam: Hogeschool van Amsterdam, Urban Technology.

Tan, E., and Portugali, J. (2012). “The responsive city design game,” in Complexity Theories of Cities Have Come of Age, eds J. Portugali, H. Meyer, E. Stolk, and E. Tan (Berlin: Springer), 369–390. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24544-2_20

Valkanova, N., Walter, R., Moere, A. V., and Müller, J. (2014). “MyPosition: sparking civic discourse by a public interactive poll visualization,” in CSCW'14: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (Baltimore, MD), 1323–1332. doi: 10.1145/2531602.2531639

Vlachokyriakos, V., Comber, R., Ladha, K., Taylor, N., Dunphy, P., McCorry, P., et al. (2014). “PosterVote: expanding the action repertoire for local political activism,” in DIS'14: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (Vancouver, BC: ACM), 795–804. doi: 10.1145/2598510.2598523

Voida, A., Yao, Z., and Korn, M. (2015). “(Infra)structures of volunteering,” in Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (Vancouver, BC: ACM), 1704–1716. doi: 10.1145/2675133.2675153

Wouters, N., Huyghe, J., and Vande Moere, A. (2014). “StreetTalk: participative design of situated public displays for urban neighborhood interaction,” in Proceedings of the NordiCHI 2014: The 8th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Fun, Fast, Foundational (Helsinki), 747–756. doi: 10.1145/2639189.2641211

Keywords: design framework, participatory design, playable city, neighborhoods, design spaces, city-making

Citation: Slingerland G, Lukosch S, Hengst Md, Nevejan C and Brazier F (2020) Together We Can Make It Work! Toward a Design Framework for Inclusive and Participatory City-Making of Playable Cities. Front. Comput. Sci. 2:600654. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2020.600654

Received: 30 August 2020; Accepted: 28 October 2020;

Published: 21 December 2020.

Edited by:

Anton Nijholt, University of Twente, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Micael Silva Sousa, University of Coimbra, PortugalCopyright © 2020 Slingerland, Lukosch, Hengst, Nevejan and Brazier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geertje Slingerland, Zy5zbGluZ2VybGFuZEB0dWRlbGZ0Lm5s