- 1Department of Education, Concordia University, Montréal, QC, Canada

- 2Department of English, Universidad Andrés Bello, Santiago, Chile

Metaperceptions (or the impressions people believe to make on others) are a potential source of misconception in conversations involving members of the same ethnic community. We investigated whether speakers’ tendency to underestimate how they are perceived by others has consequences for future interaction. In this quantitative study, we paired 46 previously unacquainted speakers of Vietnamese as a heritage language (23 second-generation speakers, 23 recent immigrants) for two conversations. The speakers in each pair, recruited through convenience sampling, were similar in age (all young adults, with a range of 18–39 years). Each pair included one second-generation speaker born in Canada, age-matched with one immigrant, with a balanced distribution of speakers’ gender (eight pairs of women, seven pairs of men, and eight mixed pairs). After each conversation, the speakers used a 100-point scale to assess each other’s interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language ability, provided their metaperceptions for their partner’s ratings, and assessed their willingness to engage in future interaction. Results of statistical comparisons (ANOVAs, correlations) indicated that all speakers underestimated how their partner perceived their interpersonal liking and heritage language (but not cultural belonging), but all ratings improved over time. However, only Vietnam-born speakers seemed to factor their perceived cultural belonging into their willingness to engage in future communication. We discuss implications of these findings for intragroup cohesion and contact.

1 Introduction

Common ethnic ties bind immigrants and their families together, potentially providing them with numerous social and economic benefits (Cohen, 1997). Through stronger ties to their ethnic community, immigrants typically have better mental health and greater job prospects (Kuo and Tsai, 1986; Sanders et al., 2002) and also maintain their heritage language and culture (Li, 1994; Le and Trofimovich, 2024). In Canada, the context of our study, the language spoken by immigrants and their children which is neither the country’s official language (French or English) nor an indigenous language spoken by one or more First Nations (McIvor, 2020) is typically referred to as a heritage language (Nagy, 2021). Despite sharing a heritage language and culture, some immigrant communities can experience tensions, misunderstandings, and conflict (Liu, 2014; Seol and Skrentny, 2009). Previous work exploring heritage language speakers’ within-group relationships has generally investigated their attitudes toward undifferentiated samples or anonymous guises (e.g., Denney et al., 2022). In this study, instead, we investigated paired interactions between age-matched members of the same ethnic group and focused on their metaperceptions, that is, the impressions they believe they make on each other (Kenny and DePaulo, 1993). More specifically, we examined (a) whether interlocutors underestimated how much they believe others like them and how highly others assessed whether they belonged to their shared heritage culture (Gatbonton et al., 2005) and spoke their heritage language (Montrul, 2023), and (b) whether these perceptions were associated with interlocutors’ desire to engage in future interaction. Theoretically, our goal was to highlight metaperception as a construct relevant to heritage language use. Practically, our intent was to understand which aspects of co-ethnic interaction promote cultural cohesion and co-ethnic solidarity, both of which are broadly understood as the willingness of individuals to support others because they share the same heritage background (Grancea, 2010).

2 Background literature

To adapt to and survive in a new environment, immigrants tend to prioritize cohesion and solidarity in their relationships with members of their ethnic community. This can lead to better social adjustment of immigrants (Kuo and Tsai, 1986; Sanders et al., 2002) and greater language and cultural knowledge in subsequent generations of heritage language speakers (Le and Trofimovich, 2024; Li, 1994). For ethnic South Koreans in Canada, for example, community-focused church activities often provide opportunities for members of the local diaspora to develop social bonds with recent immigrants, including international students and skilled workers and their children (Park and Sarkar, 2007). In addition to interpersonal and cultural benefits, strong ethnic ties offer immigrants various economic advantages such as increased job opportunities, improved financial wellbeing, and enhanced social mobility (Tran, 2016). For instance, local businesses tend to enjoy greatest success when they not only target immigrants as customers but also hire them through tailored employment programs (Zonta, 2012). Thus, positive relationships can benefit all members of an ethnic diaspora on multiple social, cultural, and economic levels.

Even though immigrant groups often enjoy close-knit, cohesive links as they develop and maintain synergy among their members, a harmonious relationship between members of those groups is not always attainable, especially in the presence of geographic and temporal differences in immigration patterns. For example, ethnically Chinese youths from the established Chinese community in Singapore tend to accentuate many of their differences from peers representing recent immigrants from China (Liu, 2014). These groups feel mutual resentment about various issues, including sociopolitical views, work ethic, daily habits, and accents. In South Korea, similar tensions have been reported for South Koreans and ethnically Korean migrants from China despite many similarities between these groups (Seol and Skrentny, 2009). In the United Kingdom, Vietnamese youths appear to be highly sensitive to cultural and linguistic differences between immigrant families from North and South Vietnam (Bloch and Hirsch, 2017). In Canada, immigrants from South and North Vietnam, who represent different waves of immigration, tend to harbor negative perceptions of each other, primarily regarding each other’s sociopolitical views and accents (Le and Trofimovich, 2024). As noted by Clammer (1999) in relation to Chinese immigrants in Singapore, “there is no simple thing called ‘Chinese identity’” (pp. 19–20), or any ethnic identity for that matter around the world. Indeed, many groups are heterogeneous, divided by accent, religion, class, and politics (Bloch and Hirsch, 2017; Denney et al., 2022; Perera, 2015; Smolicz et al., 2001). As a result, some group members might feel misunderstood or mistreated by those they consider to be their compatriots with rifts in co-ethnic relations emerging over generations or across waves of immigration (Liu, 2014).

Because various conflicts can arise among ethnic community members, such tensions might erode some of the community’s core cultural and linguistic values (Kumar et al., 2008; Sachdev and Bourhis, 2005). In terms of cultural belonging, immigrants first tend to establish relationships with ethnic peers before they attempt to integrate themselves into a host society (Salami et al., 2019). Ethnic peer relationships are developed through interpersonal contacts such as in sports clubs for Turkish immigrants in Germany (Burrmann et al., 2017) or common social networks for Japanese immigrants in Scotland and Spain (Martinez-Callaghan and Gil-Lacruz, 2017), and they tend to decrease loneliness, improve self-worth, and foster emotional attachment (Krause, 2011). Immigrants’ heritage language use can contribute to a sense of social engagement and community belonging (Craith, 2012), such as for young adults in social organizations at an American university (Ibe, 2020) and children learning their heritage language in Canada (Park and Sarkar, 2007). Clearly, interpersonal communication is at the core of an immigrant’s experience in the sense that their belonging to their community is established through contact and strengthened through heritage language use (AhnAllen et al., 2006; Sachdev and Bourhis, 2005). However, even a single unpleasant experience might have a disproportionately negative effect leaving people uneasy about themselves or their heritage language (Baumeister et al., 2001). In the words of a service provider working with newcomers, unpleasant experiences make it challenging for new immigrants to “get into [their] ethno-cultural society… to build up [a] new network,” particularly a network with local-born peers (Salami et al., 2019, p. 30).

Considering that many immigrants might have false impressions, misconceptions, or conflict with other members of their ethnic community that impact their cultural belonging and language practices (Liu, 2014; Seol and Skrentny, 2009), it is important to understand possible reasons for these perceptions. One possible reason relates to people’s metaperceptions, which refer to the impressions that people believe they make on others. Metaperceptions are central to people’s understanding of themselves and their view of society because they shape people’s identities, relationships, and behaviors (Carlson and Barranti, 2016; Kenny and DePaulo, 1993). Some metaperceptions are fairly accurate (Carlson et al., 2010; Carlson and Kenny, 2012) in that people have good insight into how others view their personality (e.g., open-mindedness), competence (e.g., leadership), and affect (e.g., happiness). However, people are often off-target in how others perceive their social attributes, including interpersonal liking. In fact, people consistently show a liking gap, whereby they underestimate how much they are liked by others, and this negative perception influences their behavior (Boothby et al., 2018; Mastroianni et al., 2021).

The liking gap, evident from age 5 through adulthood, occurs in conversations as short as 5 min among family members, friends, coworkers, and previously unacquainted individuals who are speaking their first or second languages (Mastroianni et al., 2021; Trofimovich et al., 2023; Wolf et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2024). More importantly, the tendency to underestimate liking appears to have real-life consequences (Byron and Landis, 2020). For instance, for workplace employees collaborating in small teams and university students interacting in an academic discussion task, their reported willingness to ask for help, give feedback, collaborate on future projects, and communicate with the same interlocutor were impacted by how much they believed their interlocutors liked them (Mastroianni et al., 2021; Trofimovich et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2024). For immigrants, a metaperception bias may explain why speakers belonging to the same ethnic community are hesitant to interact with each other. For instance, speakers might believe that their interlocutors like them less than these interlocutors actually do, and speakers might also worry that their language skills or their belonging to the shared community might be questioned or underappreciated. Clearly, such metaconcerns, which might not be rooted in reality, could prevent speakers from fully enjoying various advantages of co-ethnic relationships. In sum, metaperception biases can be a source of misunderstanding with tangible consequences for interlocutors.

3 The present study

Broadly motivated by previous calls for more work that gives voice to immigrants (Sammut, 2012), we sought to extend previous work on interpersonal liking to focus on conversations between interlocutors from the same immigrant community (i.e., the Vietnamese diaspora in Montréal, Canada) with different immigration backgrounds: second-generation Vietnamese Canadians (i.e., individuals raised in Canada by Vietnamese immigrants) and age-matched recent immigrants from Vietnam (i.e., skilled workers and international students who have presumably qualified for permanent residency or citizenship). We focused on these two age-matched groups because they belong to the same generation and thus (at least hypothetically) share common interests and experiences. However, despite these similarities, the two groups remain essentially distinct, consistent with prior work on the Vietnamese diaspora (Bloch and Hirsch, 2017) and other ethnic communities (Liu, 2014), which raises questions as to why there is often little meaningful contact between them. We suspected that these two cohorts of ethnically Vietnamese individuals might experience some misperception in their communication on the basis of their divergent lived experiences. Whereas local second-generation participants have intimate knowledge of Canada and strong skills in its two official languages (English and French), recent immigrants have greater heritage language proficiency and more in-depth cultural knowledge of present-day Vietnam. We suspected that these differences between the participant cohorts provided fertile ground for potential interpersonal, linguistic, and communicative insecurity. We aimed to capture this insecurity through metaperceptions and explore their consequences for speakers’ future interaction with each other.

To understand the role of metaperceptions (i.e., impressions that speakers believe they make on others) in interaction between heritage language speakers of Vietnamese, we focused on three sets of judgments. In addition to interpersonal liking, which has been examined in prior work (Boothby et al., 2018; Mastroianni et al., 2021; Wolf et al., 2021), we explored two additional measures which, to the best of our knowledge, had not been investigated previously. One new measure involved speakers’ metaperception of cultural belonging, which included beliefs about how their partners evaluated their belonging to shared Vietnamese culture and values. The other new measure involved speakers’ metaperception of their heritage language skills, which was operationalized as beliefs about how their partners evaluated their Vietnamese language accuracy, fluency, and comprehensibility. We reasoned that these new dimensions could capture potential sources of insecurity beyond interpersonal liking. For instance, speakers might underestimate how much they are liked or accepted as members of a given ethnic community (Sachdev and Bourhis, 2005). Similarly, considering that loyalty to an ethnic group may be interpreted based on a speaker’s language skill (Gatbonton et al., 2005), speakers might feel insecure about their language use. We elicited speakers’ judgments twice (after an introductory conversation and then again after a longer discussion) to determine if their metaperceptions of interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language skill changed as their conversations unfolded, and we examined these perceptions in relation to speakers’ desire to communicate with each other in the future. In essence, the three measures of metaperception were meant to capture various ways in which heritage language speakers might see themselves through the eyes of their interlocutors and to determine if their perceptions predict their desire to communicate with those interlocutors in the future. Again, our goal was not to examine heritage speakers’ likability, cultural belonging, and heritage language skills, but rather to determine how they believed they are perceived by their interlocutor and whether these perceptions guide these speakers’ potential future behavior.

This study was carried out in the Vietnamese diaspora of Montréal, Canada. In the 1970s and 1980s, approximately 120,000 refugees, mostly from South Vietnam, settled in Canada’s large metropolitan areas such as Montréal, Vancouver, and Toronto in the aftermath of the Vietnam war (Lambert, 2017). Montreal’s Vietnamese community consists of over 40,000 individuals who reside in a French–English bilingual context, which ensures that most of its members have some knowledge of English and French in addition to Vietnamese (Statistics Canada, 2023). In other respects, the experiences of Montréal’s Vietnamese community are largely similar to those of Vietnamese immigrants in other locations such as the United States (Maloof et al., 2006), the United Kingdom (Bloch and Hirsch, 2017), and Australia (Tran et al., 2022), in the sense that most refugees fled the economic hardship and wartime trauma in their homeland (Dorais, 2004; Dorais and Richard, 2007). Like other (South) Vietnamese diasporas (Bloch and Hirsch, 2017), the Vietnamese community of Montréal also demonstrates strong aspirations to differentiate themselves from present-day Vietnam. For example, the local organization representing Vietnamese Canadians continues to endorse the flag of South Vietnam (Communauté Vietnamienne au Canada, région de Montréal, 2021), highlighting this important aspect of the community’s cultural identity to their members. Additionally, Montréal-area Vietnamese heritage language schools adhere to the teaching methods predating 1975, rather than using current textbooks from Vietnam (Le and Trofimovich, 2024). In this sense, if second-generation speakers of Vietnamese raised in Montréal are inclined to embrace their community’s strong support for South Vietnam, these social views might lead to potential tensions when local-born second-generation speakers meet and interact with age-matched recent immigrants from contemporary Vietnam. We did not explore or capture these cross-context tensions directly; nevertheless, we believed that, if present, they would play into the dynamics of an initial interaction between Canada-born and Vietnam-born heritage speakers of Vietnamese, with potential consequences for their metaperceptions.

Considering the reliable liking gaps reported in prior research (Boothby et al., 2018; Carlson and Kenny, 2012; Elsaadawy and Carlson, 2022), we predicted that all speakers, regardless of where they were born, would underestimate the extent to which they are liked by their interlocutors and that this bias would be evident after both conversations. However, we anticipated that the liking gap might be greater for Vietnam-born recent immigrants because they might feel insecure communicating with an interlocutor who has greater knowledge of the local Montréal context and its Vietnamese diaspora. As for metaperceptions of cultural belonging and heritage language, we had little basis for formulating specific predictions because these dimensions were new and developed specifically for this study. However, we did speculate that second-generation participants would have a greater tendency to underestimate their heritage language ability because they might feel insecure communicating in Vietnamese with recent immigrants who have superior Vietnamese language knowledge. And in terms of the potential consequences of metaperceptions, we expected that at least some metajudgments (and especially interpersonal liking) would be associated with speakers’ interest in participating in future interactions, in line with evidence from previous research (Mastroianni et al., 2021; Trofimovich et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2024). Our study was guided by two research questions:

1. Do Canada- and Vietnam-born heritage language speakers’ metaperceptions of interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language (perceived ratings) differ from how they are evaluated by their interlocutors (actual ratings)?

2. Are heritage language speakers’ metaperceptions of interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language associated with their desire to engage in future interaction with their interlocutors?

4 Method

4.1 Participants

Participants included 46 heritage speakers of Vietnamese, all residents of Montréal, Canada, recruited through convenience sampling using Vietnamese social media and community cultural events. Half of the participants (10 women, 13 men) were second-generation Vietnamese Canadians (henceforth, Canada-born speakers) with a mean age of 24.09 years (SD = 4.61). They were children of families who emigrated from Vietnam in the 1970s (3 families), 1980s (9 families), 1990s (9 families), and the early 2000s (1 family), where both parents are ethnically Vietnamese (i.e., no parent represented other common ethnic groups in Vietnam such as Chinese or Khmer). Nineteen of these participants were born in Québec, while four arrived between the ages of one and three. They received formal primary and secondary education in Québec in French (16), English (4), or both (3). At the time of the study, they were university students (15) or early-career professionals (8). Using a 100-point scale (100 = “fluent”), they self-rated their speaking ability in Vietnamese as intermediate, with much variation across participants (M = 50.83, SD = 27.86, range = 2–100), but they provided high estimates for their speaking ability in English (M = 94.26, SD = 8.50, range = 73–100) and French (M = 93.39, SD = 9.38, range = 75–100).

The other 23 participants were Vietnam nationals (13 women, 10 men) who recently moved to Canada from Vietnam (henceforth, Vietnam-born speakers). They were international university students (18) or professionals on a post-graduation work visa (5), with a mean age of 23.91 years (SD = 4.99) and a mean length of residence in Montréal of four years (SD = 2.85, range = 1–9 years). They were born and raised in monolingual households in Vietnam and educated through primary and secondary schooling in Vietnamese before their arrival. Using the same scale, they self-rated their Vietnamese speaking ability as high (M = 97.35, SD = 9.09, range = 57–100), with a lower self-rating in English (M = 89.52, SD = 9.15, range = 64–100) and an even lower estimate for French (M = 24.09, SD = 25.48, range = 0–100).

To collect interaction data, we paired one Canada-born speaker with one Vietnam-born speaker who were roughly the same age and had not previously met. We balanced self-reported genders across pairs: eight pairs of women, seven pairs of men, and eight mixed pairs. Because members of the Vietnamese diaspora frequently associate a family’s geographic origin from North or South Vietnam with a different political ideology (Bloch and Hirsch, 2017; Le and Trofimovich, 2024), we also considered participants’ family origins in Vietnam, with 11 matched (South–South, North–North) and 12 mismatched (North–South) pairs, although southern families were overrepresented among the matched pairs (10:1). This imbalance in favor of immigrants from South Vietnam is not unique to Montréal, reflecting the general composition of other Vietnamese communities in North America (Barnes and Bennett, 2002). Nevertheless, even though participants’ family origin or their specific social and political views, including their ethnocultural and ethnolinguistic identity, are a fruitful research target, our primary focus remained with age-matched interlocutors who belonged to the same ethnic group but were born in either Canada or Vietnam.

4.2 Materials

The materials included several discussion prompts, a questionnaire eliciting the speakers’ perceptions of each other, and a language background survey.1 During the conversation, we provided them with (a) introduction prompts focusing on personal information such as field of work or study, hobbies, and favorite foods, and (b) questions to guide their further discussion about themselves (e.g., Where do you or your family come from in Vietnam?), their work and life challenges (e.g., What challenges do newcomers from Vietnam often face in Québec? What challenges do Canada-born Vietnamese have?), and potential differences between those challenges (e.g., Are these challenges better or worse?). These prompts, which did not explicitly target any cultural or linguistic stereotypes, were purposely designed for this study to facilitate a naturalistic conversation between two previously unacquainted interlocutors who first get to know each other before sharing personal challenges and comparing them. All prompts, which were provided on a handout distributed to each participant, were available in both Vietnamese and English to foster inclusivity and avoid disadvantaging any speakers due to an imbalance in language proficiency. To highlight the importance of Vietnamese, the Vietnamese text of the prompts was bolded, while the English translation of the same prompt followed in parentheses. Even though all participants resided in Québec, a majority French-speaking province of Canada, discussion prompts were not available in French because participant recruitment and testing took place at an English-medium university and because all participants had high proficiency in English but more variable self-rated ability in French.

We used a questionnaire to probe the speakers’ impressions about their conversations. The first part of the questionnaire elicited each speaker’s impression of their partner along three dimensions, with four statements per dimension for a total of 12 items. The first dimension (adopted directly from Boothby et al., 2018) was interpersonal liking, which captured how much each speaker liked their partner: (a) “I liked this person”; (b) “I would like to get to know this person better”; (c) “I would like to interact with this person again”; and (d) “I could see myself becoming friends with this person.” The next two dimensions (cultural belonging and heritage language) were developed specifically for this study; the statements targeting these dimensions were created by the research team following the format of those targeting interpersonal liking (Boothby et al., 2018) and were refined through iterative discussion and informal piloting. Cultural belonging captured how much each speaker believed that their partner belonged to the Vietnamese culture: (a) “I accepted this person as a member of the Vietnamese community”; (b) “I liked how this person understands the Vietnamese culture”; (c) “I liked that this person knows Vietnamese”; and (d) “I liked how this person shares the Vietnamese values.” Heritage language targeted how each speaker evaluated their partner’s Vietnamese speaking ability: (a) “I liked how well this person spoke Vietnamese”; (b) “I liked how fluently this person spoke Vietnamese”; (c) “I liked how easy this person was to understand in Vietnamese”; and (d) “I liked this person’s Vietnamese pronunciation.” For all statements, the speakers expressed their opinion using a 0–100 sliding scale, with endpoints labeled as “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.”

In the second part of the questionnaire, each speaker used similar 12 statements with the same scale and endpoints. These statements targeted the same three dimensions but elicited the speakers’ metaperceptions by asking them to rate how they believed their partner felt about them. For interpersonal liking, the statements (again, adopted directly from Boothby et al., 2018) included: (a) “I think the person liked me”; (b) “I think this person would like to get to know me better”; (c) “I think this person would want to interact with me again”; and (d) “I think this person could see themselves becoming friends with me.” All remaining metaperception statements were purposely designed for this study and piloted by the research team, as described above. For cultural belonging, the statements were: (a) “I think this person accepted me as a member of the Vietnamese community”; (b) “I think this person liked how I understand the Vietnamese culture”; (c) “I think this person liked that I know Vietnamese”; and (d) “I think this person liked that I share the Vietnamese values.” For heritage language, the statements were: (a) “I think this person liked how well I spoke Vietnamese”; (b) “I think this person liked how fluently I spoke Vietnamese”; (c) “I think this person liked how easy I was to understand in Vietnamese”; and (d) “I think this person liked my Vietnamese pronunciation.” The statements about each speaker’s perceptions of their partner and their metaperceptions were elicited twice: after a 5-min introductory conversation and after a 10-min discussion of challenges.

The last part of the questionnaire focused on potential future consequences of interaction from the perspective of each speaker. There were six statements, each accompanied by a 0–100 sliding scale, with endpoints labeled “never” and “definitely” asking the speakers to estimate whether they would want to engage in several social activities with their conversation partner. These statements were inspired by Mastroianni et al.’s (2021) items targeting the consequences of metaperception and were developed purposely for this study by the research team, following the same procedures as above. The activities involved joining a community event together (i.e., working in a community project, texting each other about a social/cultural activity), interacting socially (i.e., eating out together), and interacting privately (i.e., discussing personal issues, discussing political topics, giving open and honest feedback). Finally, we used a background survey to obtain language and demographic information from all speakers, including self-ratings of their Vietnamese, English, and French speaking skills. Before data collection, all conversation prompts and questionnaires, along with all testing procedures, were piloted with an additional pair of interlocutors of a similar age.

4.3 Procedure

All data collection was conducted in accordance with an approved ethics certificate (30017638) from the researchers’ university. The data collection took place in a quiet research space with multiple rooms on campus, with one of two researchers assigned to each pair. The researchers first ensured (to the best of their ability) that the two speakers did not meet and greet each other before data collection, by inviting them to separate rooms upon arrival when they reviewed and signed the consent form (2 min). Both speakers were then brought to another room where they were seated at a table across from each other. At this point, one of the two researchers (a first-language speaker of Vietnamese with advanced proficiency in English and French) provided the instructions to both participants in English and Vietnamese (e.g., please talk to each other using the prompts in front of you), encouraging them to use as much Vietnamese as they could, with the understanding that they could switch to English or French for words or phrases they were unable to describe in Vietnamese. The researcher then left the room, allowing the speakers to complete the task unobserved. The discussion was audio-recorded through a microphone outside the speakers’ direct view so as not to distract them. All speakers were made aware of the recording through the consent form and instructions provided before the task. After the maximum time for the introductory discussion elapsed (5 min), the researcher re-entered the room and invited the speakers to go to their original individual rooms where they used the LimeSurvey platform2 on a laptop to provide their perceptions of the interaction (10–15 min). The speakers then returned to the common room where they received the next set of discussion questions prompting them to share their family backgrounds and to discuss various challenges. After the 10-min mark for each conversation, the speakers returned to the same individual rooms to answer the second set of questionnaires, followed by the statements about their desire to engage in future interaction with their partner and the background survey. Each participant remained alone while completing the online questionnaires in their designated room until they left the research space (20–25 min).

4.4 Data analysis

In terms of the speakers’ perceptions of each other, there were two sets of ratings per speaker: their actual ratings (i.e., assessments by their partner) and their perceived ratings (i.e., metaperceptions, or how they believed their partner assessed them), recorded after the 5-min introductory conversation and then again after the 10-min discussion. The speakers’ responses to the four statements per rated dimension demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for actual interpersonal liking (0.92–0.95), actual cultural belonging (0.91–0.93), actual heritage language (0.92–0.94), perceived interpersonal liking (0.95–0.97), perceived cultural belonging (0.92–0.96), and perceived heritage language (0.94–0.95). Therefore, each speaker’s evaluations were averaged across the four relevant statements (i.e., across items a through d, as described above) to derive a single actual and a single perceived score per dimension (i.e., interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language), separately for the introductory conversation and the discussion. In terms of the desire to engage in future interaction, there was high consistency across the six items (0.87), so a single mean composite score was computed per speaker. Because each conversation was stopped at the allotted 5-min mark for the initial conversation and the 10-min mark for the discussion, interaction length was identical across all pairs so it did not need to be controlled.

We then examined the language dynamics of each conversation by quantifying each speaker’s use of Vietnamese versus English or French in their conversations. Because the use of French was minimal (identified in only six of the 23 pairs and involving between 1 and 4 words), this analysis focused only on Vietnamese. We calculated the amount of time (in seconds) each participant spent speaking Vietnamese and subsequently determined the proportion of Vietnamese use relative to the total duration of the conversation. This means that the remaining proportion was carried out in English. On average, Canada-born speakers used Vietnamese 34.54% of the time (SD = 18.02, range = 0–57) in the introductory conversation and 32.31% (SD = 20.34, range = 2–63) in the discussion. Vietnam-born speakers used Vietnamese to a similar degree, on average, 37.83% of the time (SD = 17.64, range = 0–68) in the introductory conversation and 35.18% (SD = 17.28, range = 3–62) in the discussion. Whereas the speakers’ use of Vietnamese was low, this was not unexpected. Canada-born speakers may have felt insecure about their heritage language skills when communicating with Vietnam-born speakers, who in turn may have accommodated their partner’s linguistic needs by switching to English. Because individual speakers showed varying levels of Vietnamese use, we examined this variable in relation to our research questions (see below).

All data were first checked for the assumptions of homogeneity of variance and sphericity. For interpersonal liking, skew values ranged between −0.74 and − 0.06, and kurtosis values ranged between −0.40 and 0.16; Levene’s tests of equality of error variances yielded nonsignificant statistics, Fs(1, 44) < 4.78, ps > 0.132. For cultural belonging, skew values ranged between −1.25 and − 0.43, and kurtosis values ranged between −1.01 and 0.92; Levene’s tests also yielded nonsignificant statistics, Fs(1, 44) < 4.32, ps > 0.172. For heritage language, skew values ranged between −0.95 and − 0.66, and kurtosis values ranged between −0.23 and 0.09; Levene’s tests similarly yielded nonsignificant statistics, Fs(1, 44) < 6.28, ps > 0.064. According to Mauchly’s tests, with only two levels of each repeated-measures factor, sphericity was not an issue for any analysis (Field, 2009). Therefore, all data were analyzed through parametric procedures: analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Pearson (two-tailed) correlation tests. To address the first research question, which asked whether the speakers differed in their actual versus perceived assessments, we carried out mixed ANOVAs to compare the speakers’ ratings of interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language as a function of speaker background (Canada-born vs. Vietnam-born), which was a between-participants variable, with repeated measurements for rating type (actual vs. perceived) and time (after introductory conversation vs. after discussion). A statistically significant main or interaction effect for rating type would suggest that there is a metaperception bias (i.e., a gap between the actual and perceived ratings), whereas any statistically significant main or interaction effect involving speaker background and time would imply that the speakers’ ratings differ as a function of these variables.

To address the second research question about potential consequences of speaker perceptions, we computed Pearson correlations to explore the associations between the speakers’ perceived ratings in terms of interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language (i.e., metaperceptions or how they believed they were perceived) and their desire to engage in future interaction, using the composite score of predicted future interaction. To provide a baseline for examining the role of metaperceptions in future behavior, we also computed similar associations involving their actual ratings for the same dimensions (i.e., how they were actually perceived by their partners). For all statistical analyses, the alpha level for significance was set at 0.05. Effect sizes for main and interaction effects were reported as r, which is a frequently used and intuitive measure of the practical significance of contrast-specific statistical differences (Field, 2009), where the values of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 correspond to small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Cohen, 1992). Correlation strength was interpreted using field-specific guidelines for language-focused research, where the values of 0.25, 0.40, and 0.60 correspond to small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Plonsky and Oswald, 2014).

5 Results

5.1 Perceived and actual assessments

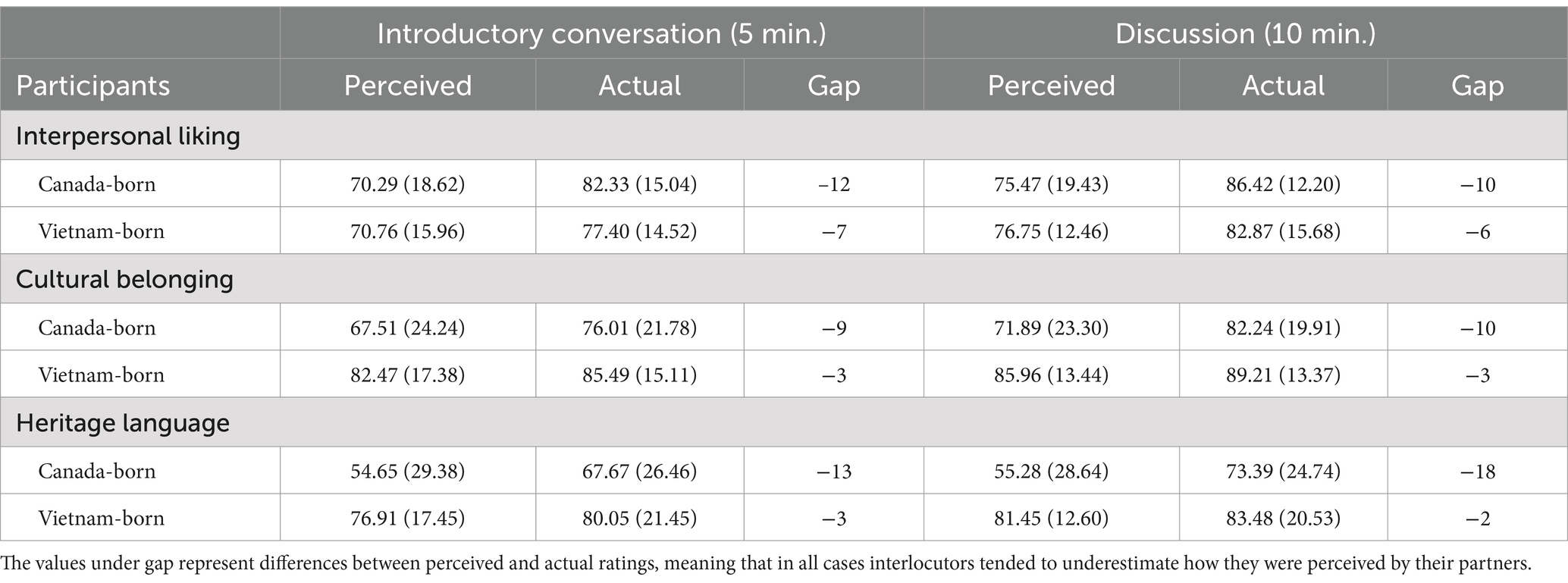

As summarized in Table 1, the speakers’ actual ratings (assessments by their partner) were generally higher (67–89 on a 100-point scale) than their perceived ratings (metaperceptions or how they believed they were perceived) (54–85). The ratings also varied over time, with speakers providing higher ratings after the discussion than the introductory conversation.

To compare the ratings of interpersonal liking, we carried out a three-way mixed ANOVA with speaker background as a between-participants variable and rating type and time as within-participants variables. This analysis revealed statistically significant main effects for rating type, F(1, 44) = 6.24, p = 0.016, r = 0.35 (medium effect), and time, F(1, 44) = 28.64, p < 0.001, r = 0.63 (strong effect), but no significant main effect for speaker background, F(1, 44) = 0.41, p = 0.524, r = 0.10, and no significant two-way or three-way interactions, Fs(1, 44) < 0.51, ps > 0.479, rs < 0.11. Thus, all speakers, regardless of background and time, considered that they were liked by their partners less than they were actually liked. Even though both perceived and actual ratings of liking increased significantly between the first and the second evaluation time, the magnitude of the gap did not change.

For the ratings of cultural belonging, the ANOVA yielded statistically significant main effects for speaker background, F(1, 44) = 8.64, p = 0.005, r = 0.41 (medium effect), and time, F(1, 44) = 17.23, p < 0.001, r = 0.53 (strong effect), but no significant main effect for rating type, F(1, 44) = 2.72, p = 0.106, r = 0.24, and no significant two-way or three-way interactions, Fs(1, 44) < 0.68, ps > 0.414, rs < 0.12. Thus, the speakers showed no gap in how their cultural belonging was seen by their partner. However, cultural belonging was rated higher for Vietnam- than Canada-born speakers, and these ratings also increased from the first to the second evaluation.

The ANOVA comparing the ratings of heritage language revealed statistically significant main effects for rating type, F(1, 44) = 4.48, p = 0.040, r = 0.30 (medium effect), time, F(1, 44) = 5.04, p = 0.030, r = 0.32 (medium effect), and speaker background, F(1, 44) = 12.89, p < 0.001, r = 0.48 (medium effect), but no significant two-way or three-way interactions, Fs (1, 44) < 2.29, ps > 0.137, rs < 0.22. Therefore, regardless of their background, the speakers underestimated the extent to which their heritage language was assessed by their partners. Heritage language ratings were also higher for Vietnam-born than for Canada-born speakers, and these ratings increased from the first to the second evaluation, but the magnitude of the gap between perceived and actual ratings did not change.

Because the speakers varied in their Vietnamese use during interaction, we additionally explored associations between their ratings and Vietnamese use. For Vietnam-born participants, the amount of their Vietnamese use was unrelated to their ratings of any dimension (r < |0.23|). However, for Canada-born participants, there was a positive association with their perceived ratings of cultural belonging (r = 0.53 in the introductory conversation, r = 0.59 in the discussion) and their perceived ratings of heritage language (r = 0.49 in the introductory conversation, r = 0.67 in the discussion), with most associations approaching large effects. In all cases, the more the speakers used Vietnamese, the more they believed that they were accepted by their partner as a member of their cultural group and were appreciated for their heritage language ability.

5.2 Willingness to engage in future interaction

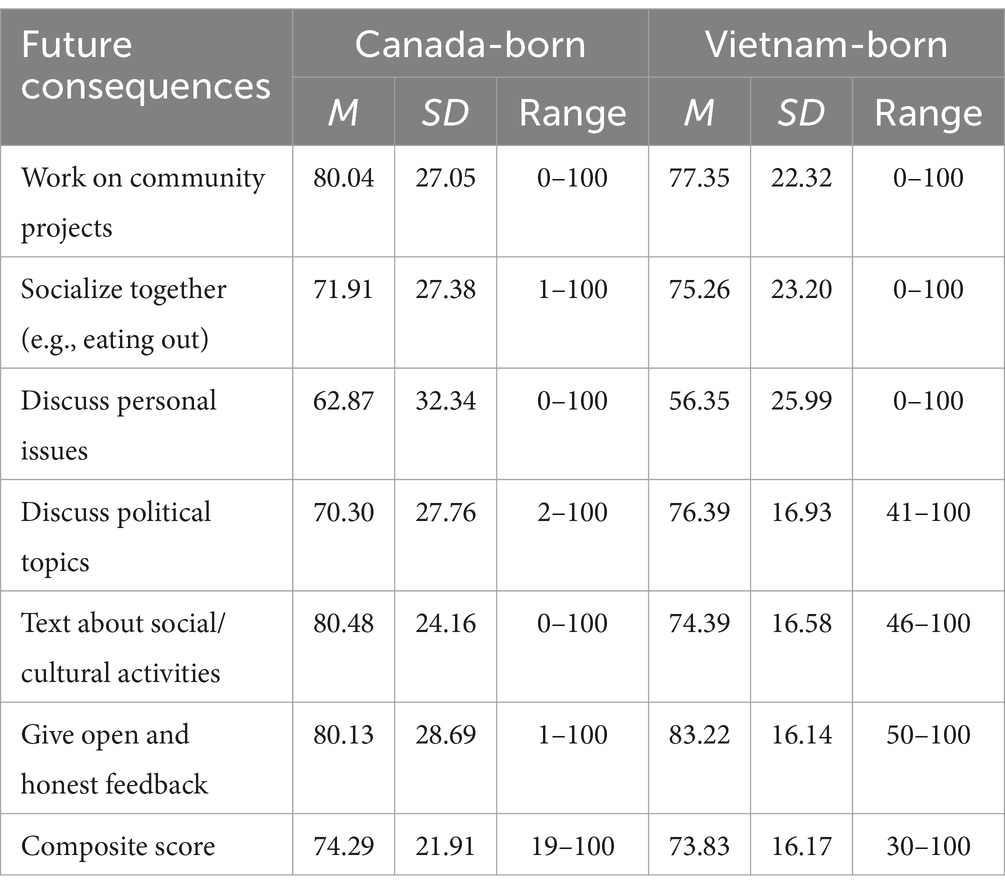

The second research question asked whether the speakers’ perceived scores (i.e., metaperceptions or how they thought their partner evaluated them) were associated with potential future consequences. As summarized in Table 2, the speakers expressed strong desire to interact with each other: Canada-born participants’ mean composite score was 74.29 on a 100-point scale, and Vietnam-born participants’ mean score was 73.83. However, as shown through substantial variability in these values, and in the individual scores contributing to the composite measure, individual speakers expressed different opinions.

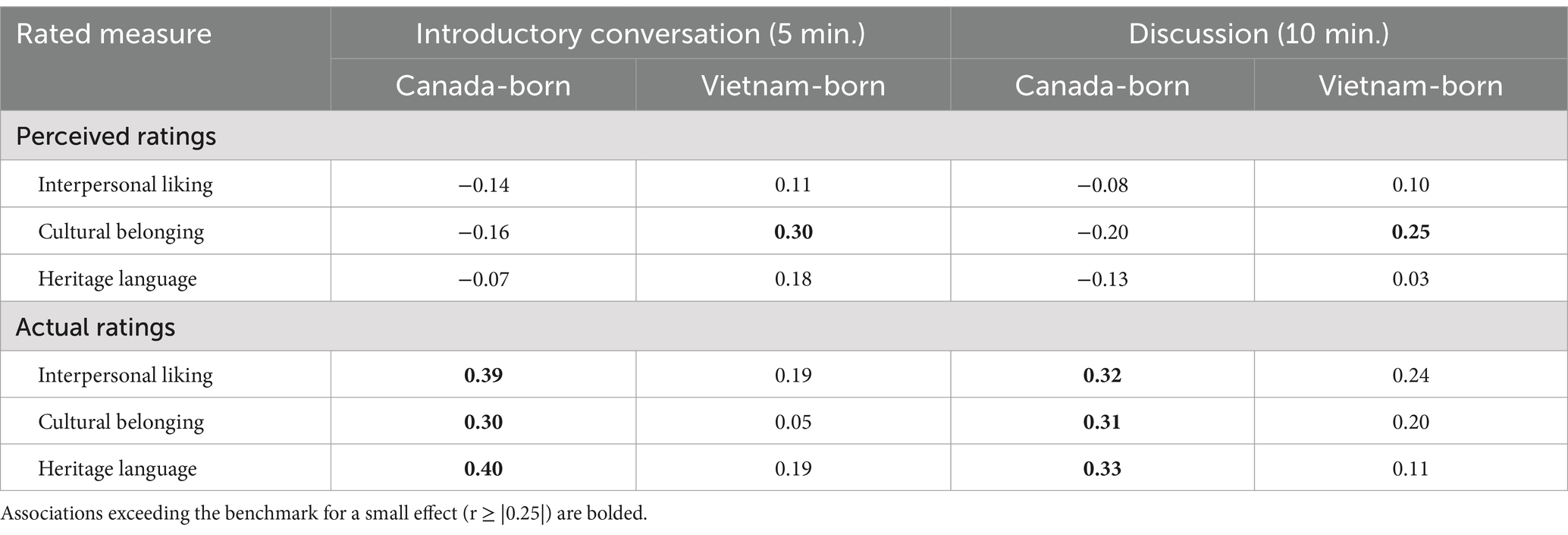

To address the second research question, we computed correlations between the speakers’ composite measure of predicted future interaction and their perceived ratings (i.e., metaperceptions or how they believed they were perceived). To provide a baseline for understanding the role of metaperceptions, we computed similar associations for their actual ratings (i.e., how they were actually perceived by their partners). As shown in Table 3, for Canada-born participants, their desire to interact with their partner was associated only with actual ratings (r = 0.30–0.40, weak-to-medium effects), not with perceived ratings (r = 0.05–0.24), meaning that their desire for potential future interaction was associated with how they were actually perceived by their partners, where higher ratings meant greater interest in future interaction. For Vietnam-born participants, however, no actual ratings were correlated with their desire for future interaction; instead, it was associated with their perceived ratings of cultural belonging both after the introductory conversation (r = 0.30, weak effect) and after the discussion (r = 0.25, weak effect). Thus, how much Vietnam-born speakers perceived that their partners accepted them as members of their cultural group was associated with their desire to interact with those partners, where lower metaperceptions (i.e., greater insecurity as to whether their partner considered them as a member of their cultural group) meant less interest in future interaction.

Again, because the speakers varied in their Vietnamese use during interaction, we explored associations between their own and partners’ language use and the composite score of their desire for future interaction. There were no associations that reached the benchmark for a small effect, either for Canada-born participants, rs < |0.13|, ps > 0.570, or for Vietnam-born participants, rs < |0.24|, ps > 0.247, suggesting that the speakers’ predicted future interaction behavior was generally unrelated to their own or their partners’ use of Vietnamese during interaction.

6 Discussion

6.1 Metaperception in heritage language communication

Our findings extend prior work on interpersonal liking by showing that reliable liking gaps persist over time during conversations between heritage language speakers (Boothby et al., 2018; Mastroianni et al., 2021; Wolf et al., 2021). The mean liking gaps reported here (6 − 12 points on a 100-point scale) were smaller in magnitude than those reported in previous research (14–16 points) for speakers communicating in their first and second language (Boothby et al., 2018; Trofimovich et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2024). However, the proportion of speakers showing underestimated interpersonal liking (63% of Canada-born speakers, 54% of Vietnam-born speakers) was nearly identical to the 59% of participants reporting a negative liking bias in Elsaadawy and Carlson’s (2022) database of over 2,500 observations. In fact, we found a reliable liking gap for both Canada-born and Vietnam-born speakers who presumably brought different experiential toolkits to their conversation, in terms of their familiarity with a local ethnic diaspora, heritage language ability, and knowledge of ethnic culture. Additionally, these speakers’ bias to underestimate their liking seemed unrelated to their heritage language use in conversation (or the use of English as an alternative means of communication), meaning that speakers’ tendency to feel insecure about how much they are liked might be independent from which language is being used and to what extent. Thus, at least in this study, a bias to underestimate one’s liking tended to cut across ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and experiential lines.

In addition to interpersonal liking, we similarly showed a reliable gap for heritage language, where both Canada-born and Vietnam-born speakers underestimated how their partner assessed their Vietnamese in terms of accuracy, fluency, and comprehensibility. Although the gap appeared larger for Canada-born participants, compared to those born in Vietnam (see Table 1), there were no statistically significant interactions involving the speaker background. A reliable language gap for all speakers is noteworthy considering that the two speaker groups elicited the expected ratings from their partners, where Vietnamese was assessed higher for Vietnam-born speakers (76–83) than for Canada-born participants (54–73), so the speakers were aware of their relative standing yet still underestimated how their language was perceived. From the Canada-born participants’ perspective, their insecurity might have stemmed from the need to negotiate a preferred identity while using their weaker language (Skinner et al., 2001), which is supported by strong positive associations between their metaperceptions and use of Vietnamese. For Vietnam-born participants, their language experience was likely not without concerns either. Whereas it is challenging to identify a specific reason for why first-language Vietnamese speakers might underestimate how well their language skills are perceived by someone with a lower language ability, we speculate that they might have struggled to accommodate to a less proficient speaker of Vietnamese or to show themselves as an effective communicator when their conversation switched to English. For Vietnam-born participants, their linguistic insecurities may have also been heightened by their recent experience of settling in Québec, where language issues are highly politicized. For example, media reports around the time of data collection had detailed the policing of heritage language use in ethnically owned businesses (Freed, 2023). At a broader level, the obtained negative metaperception bias for heritage language is akin to the general tendency for language users to underestimate how their interlocutors perceive their conversational ability such as knowing how to start or end a conversation (Sandstrom and Boothby, 2021) and to attribute negative aspects of interaction to their own conversational shortcomings (Welker et al., 2023). Thus, it is not entirely unexpected that at least some speakers may have felt uncertain about their language skills (in Vietnamese or English) or their general conversational ability (regardless of the language) so they underestimated how their language use was perceived by their partner.

Unlike interpersonal liking and heritage language, cultural belonging was not subject to a metaperception bias. The two speaker cohorts were quite accurate at judging how strongly their partner accepted them as members of the Vietnamese community, but the ratings of cultural belonging were generally higher for Vietnam-born speakers (82–89) than for Canada-born speakers (67–82). One potential reason for the lower ratings of cultural belonging among Canada-born participants could be their gradual shift away from their ethnic culture. Just as the children of Hindi-speaking immigrants in Montréal experienced a cultural shift away from their parents’ generation toward the Canadian cultural values (Kumar et al., 2008), the second-generation Vietnamese speakers raised and educated in Canada may have also shifted in their cultural preferences. More strikingly, this shift was perceptible not only to the second-generation speakers themselves but also to their age-matched Vietnam-born peers. Considering that the conversation prompts elicited the speakers’ cultural knowledge (e.g., in terms of foods, traditions), it is likely that various gaps of Canada-born speakers in their knowledge of and experience with the Vietnamese culture were fairly obvious to both interlocutors. One finding of particular significance for second-generation heritage language speakers is that there was a strong positive relationship between Vietnamese use and perceived ratings of their cultural belonging, which implies that language is a symbol of cultural identity for speakers of Vietnamese (Sachdev and Bourhis, 2005). More extensive use of one’s heritage language thus emerges as an indicator of (and potentially a pathway for) greater confidence in how one’s cultural belonging is perceived by others.

6.2 The importance of conversation

A consistent finding of this study is that all ratings demonstrated a significant upward trend over time regardless of a metaperception gap. Put simply, even though the speakers may have persisted in showing insecurity in how they were seen in the eyes of their partners (at least in terms of interpersonal liking and heritage language), as time progressed, they felt increasingly more positive toward each other. The speakers’ increased positivity is likely a reflection of deeper, more personal contact as they discussed their individual challenges. Previous work on intra-ethnic relationships has revealed various instances of the “us-versus-them” mentality, for instance, where community members refuse to socialize outside their in-group (Zhang, 2012), propagate stereotyped views of other groups within the same diaspora (Bloch and Hirsch, 2017; Le and Trofimovich, 2024), and pass negative beliefs on to their children (Liu, 2014), thus continuing to deepen and broaden community rifts. Thus, the additional time spent together beyond the initial conversation was most likely conducive to improving mutual understanding and interpersonal cohesion between the two interlocutors and a potential pathway for minimizing the “us-versus-them” stance in interpersonal exchanges. Additionally, the observed positivity between the two speakers may have emerged because the discussion topics promoted empathy, perspective-taking, and understanding between the two interlocutors, particularly as they shared their lived experiences as ethnic Vietnamese speakers in Canada. Nevertheless, a conclusion emerging from our findings is that one way to improve mutual understanding and potentially to contribute to interpersonal cohesion is by facilitating interaction between different members of the same ethnic community so that they can get to know each other and share cultural and practical knowledge as part of structured and unstructured communication activities (Clyne, 2003; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006).

6.3 Potential consequences of metaperception

An additional goal of this study was to document whether a metaperception bias, such as people’s tendency to underestimate or overestimate how they are perceived by others, might have potential consequences for their future interaction. In our sample, only Vietnam-born participants showed an association between metaperceptions and their predicted interest in future interaction. The speakers who were feeling especially uncertain as to how their conversation partners assessed their belonging to the Vietnamese community expressed less desire to communicate with those partners. In previous metaperception research, individuals who underestimated how they were perceived by their interlocutors similarly tended to avoid various prosocial behaviors, including asking for help, providing feedback, and engaging in future interaction with peers (Mastroianni et al., 2021; Trofimovich et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2024). However, for Vietnam-born participants, this is an especially striking finding which warrants future investigation, considering that these speakers had substantial knowledge of their ethnic culture and language, as revealed through both self and partner ratings. Vietnam-born participants might have been especially prone to a metaperception bias in their desire for future interaction because of various hardships they had experienced when settling in Canada (e.g., obtaining post-graduation visa, finding employment, securing accommodation). In these circumstances, having ethnocultural approval from a local peer with direct community-based knowledge about dealing with these hardships might have been important for them. Incidentally, the social and cultural support afforded to Canada-born participants through their community likely provided them with sufficient security not to rely on metaperceptions when predicting future behavior, since their desire for future interaction was guided by their actual perceptions (see Table 3).

Another noteworthy aspect of our results concerns the finding that only metaperceptions of speakers’ cultural belonging, rather than interpersonal liking or heritage language, patterned with their predicted future behavior. Compared to interpersonal affect and language ability, cultural belonging likely taps into a deeper sense of a person’s identity, especially for recent immigrants who are yet to establish themselves in a new context, so it has a stronger foundation to catalyze their potential future behavior. As it is common for immigrants to first seek membership among the networks of their ethnic peers in the local society, before attempting to integrate themselves into a broader host society (Salami et al., 2019), Vietnam-born participants might have desired ethnocultural approval from their local-born peers, and the perceived success of this validation carried behavioral consequences. Despite having considerable linguistic and cultural capital, these recent immigrants likely saw their local-born peers as a cultural authority, thereby placing particular importance on their perceived approval to continue a social relationship with them. If this finding is confirmed in future work, it would be essential to implement intervention and awareness-raising activities such as the one reported by Sandstrom et al. (2022), where participants who engaged in a week-long intervention involving repeated conversations with strangers demonstrated enhanced positivity about their potential future interaction and increased confidence in their conversational ability. Such communication-focused activities should ideally involve both recent immigrants and local-born members of the same ethnic community and should focus on promoting interpersonal cohesion, confidence, and understanding.

Our final comment here pertains to the distinction between the role of actual and perceived ratings in speakers’ desire for potential future interaction. Unlike Vietnam-born speakers, who may have relied on their metaperception in their decision to engage in future interaction, Canada-born speakers appeared to associate their interest in future interaction with their partner’s actual ratings of them. One explanation for underconfident metaperception centers on the idea that speakers show excessive worry about their own conversational shortcomings, focus disproportionately on the negative aspects of their interactive performance, and fail to notice verbal and nonverbal signals that their interlocutor actually likes them (Boothby et al., 2018; Sandstrom and Boothby, 2021; Welker et al., 2023). It is possible, then, that Canada-born versus Vietnam-born speakers differed in how they approached their conversations. As discussed previously, the social and cultural support afforded to Canada-born participants through their community likely provided them with sufficient security not to rely on metaperceptions, allowing them to observe, detect, and potentially use any verbal or nonverbal cues of interpersonal liking or cohesion from their interactive partners (e.g., smiling and laughter, backchannels signaling agreement or approval), which they could use in their decision-making to engage in future interaction. In contrast, Vietnam-born speakers might have been excessively preoccupied with the impressions they were making on their interlocutor (at least in terms of their cultural belonging) and as shown in previous work (Boothby et al., 2018; Welker et al., 2023) may have overlooked any potential positivity in their interlocutor’s feedback, relying on (underconfident) metaperception to guide their decision-making. Needless to say, this explanation must be revisited in future work; until then, a tentative conclusion that emerges from these data is that recent immigrants, as individuals who likely experience social and cultural adjustment issues, are particularly prone to factor biased metaperception in their decisions to pursue future interaction.

7 Limitations, implications, and future work

We acknowledge several issues limiting the interpretation of our work. One limitation is the lack of qualitative evidence to clarify and interpret participants’ scale-based judgments. Rather than relying solely on participants’ scalar ratings, future research on metaperception should include individual interviews with participants to capture various reasons for why they might feel more versus less confident in how they are being perceived by their interaction partner. Think-aloud or retrospective-recall protocols might be particularly useful in providing qualitative support for scalar-based assessments. Another issue is a relatively small sample size, which reflected our challenge in locating age-matched members of two distinct cohorts of heritage speakers having similar ethnocultural experiences. Our study also took place in a lab, and all conversations were prompted by guiding questions and were audio-recorded, so interlocutors’ perceptions of each other may have been influenced by our methodological choices. Needless to say, it is important to explore the role of metaperception in naturalistic, unscripted conversations, preferably that are longer than a few minutes to allow speakers to establish trust and to get to know each other better. Our data were collected in Québec where language is the focus of fierce social and political debate (Busque, 2021), which may have impacted participants’ communicative behaviors and their assessments, especially for recent immigrants adapting to their new, highly political environment. Additionally, we explored metaperception for only two broadly-construed cohorts of heritage language speakers, without considering various deeper layers of speakers’ ethnocultural and ethnolinguistic identity, such as the sociopolitical reasons for their immigration, their family origin, or their personal histories. As shown previously by Bloch and Hirsch (2017), young Vietnamese adults in the United Kingdom tend to associate South and North Vietnam with different political ideologies due to the historical context of the Vietnam war and diverse patterns of immigration from these regions. Even though none of the discussion prompts explicitly encouraged the speakers to discuss sociopolitical issues, including historic tensions between North and South Vietnam, at least some conversations may have touched upon these topics, which may have increased or decreased interpersonal cohesion across different conversations. Unfortunately, although our sample of speakers from South versus North Vietnam generally reflected the geographic makeup of Vietnamese diasporas in North America, this sample was imbalanced, and a small cell size for specific conversational pairs did not allow us to confidently examine potential response patterns, so various sociopolitical tensions stemming from interlocutors’ backgrounds may have affected their perceptions. Similarly, various social and political tensions, with consequences for metaperception bias and its impact on future interaction, might be amplified in conversations involving interlocutors from different generations such as war-time Vietnamese refugees (i.e., parents of our second-generation participants) and present-day immigrants from Vietnam. These participant groups and other variables of significance to an immigrant’s identity must be targeted in future work.

Our findings are also specific to the conversational prompts used to facilitate communication. For instance, the prompt about sharing cultural knowledge was designed to create a sense of common identity between speakers while exposing potential gaps in their knowledge. In contrast, the personal challenges discussion allowed each speaker to act as an expert (providing advice) and a novice (seeking information). Our findings, therefore, might reflect not only the specific conversational topics but also particular interactional dynamics, where some conversations featured more equal distributions of participant roles than other conversations. As an initial study exploring the role of metaperception in heritage language communication, this work needs to be replicated to confirm that speakers indeed act on their metaperceptions in avoiding some or engaging in certain other behaviors. In the interim, our findings could be of consequence for research, in the sense that they reveal potential sources of misunderstanding and tension stemming from within an ethnic community. Unlike well-documented cross-cultural differences, particularly between members of ethnocultural minority and majority groups, community-internal tensions remain under-researched. In terms of practice, our study’s findings have implications for interventions aimed at enhancing both the cohesiveness and understanding within ethnic groups (Clyne, 2003), especially for individuals belonging to different waves of immigration. Considering that our participants grew to appreciate each other more as conversations progressed, future research could focus on investigating the effectiveness of communication-focused interventions in heterogenous ethnic communities with multiple immigration paths. For example, these interventions could be designed to foster meaningful interactions between recent and second-generation immigrants and tested in longitudinal studies to assess their effectiveness in developing or strengthening co-ethnic bonds.

8 Conclusion

Our work targeted metaperception as a source of misconception arising in communication between two members of the same ethnic community interacting in a shared heritage language. We engaged previously unacquainted speakers of Vietnamese as a heritage language in paired conversations and elicited their perceptions of each other focusing on the ratings of interpersonal liking, cultural belonging, and heritage language ability. Both Canada-born and Vietnam-born speakers demonstrated reliable metaperception gaps for interpersonal liking and heritage language, meaning that they underestimated how their interlocutor viewed them, but not for cultural belonging. These gaps were similar after the initial 5-min conversation and the entire 15-min interaction. Compared to Canada-born participants, Vietnam-born speakers generally received higher ratings of cultural belonging and heritage language from their partners, and all ratings for all speakers improved over time. In terms of potential consequences of metaperception, only Vietnam-born speakers showed a link between their perceived ratings of cultural belonging and their desire to engage in future interaction. How much these speakers believed that their partners accepted them as members of the Vietnamese community was associated with their interest in participating in future social activities with those partners.

Taken together, our findings shed light on the dynamics of co-ethnic interaction between immigrants, highlighting the role of metaperception bias (reflecting insecurity or even some anxiety) in how speakers believe their interpersonal liking and how their heritage language skills are perceived in the eyes of their interlocutors. Whereas our participants did not demonstrate a similar bias in their assessments of cultural belonging, one cohort in our sample (recent Vietnam-born immigrants to Canada) appeared to factor their judgments of how their cultural belonging was perceived into their desire for future communication, which implies that metaperceptions might determine whether or not individuals choose to communicate with each other. Finally, our findings highlighted the importance of fostering stronger co-ethnic ties through personal, extended interactions which might contribute to greater acceptance of immigrants as community members and greater appreciation of their heritage language skills. We hope that this initial exploratory study can serve as a springboard for future work examining diverse perspectives on co-ethnic interaction, with the overarching goal of fostering the cultural preservation of second generations of immigrants and the sociocultural wellbeing of new immigrants.

Data availability statement

All data and materials for this study are publicly available via the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/rby2j.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Human Research Ethics Committee, Concordia University (certificate 30017638). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

T-NNL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PT: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Insight grants awarded to the second and third authors by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (430-2020-1134 and 435-2024-1488).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1468943/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Available at: https://osf.io/ud3e6.

References

AhnAllen, J. M., Suyemoto, K. L., and Carter, A. S. (2006). Relationship between physical appearance, sense of belonging and exclusion, and racial/ethnic self-identification among multiracial Japanese European Americans. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 12, 673–686. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.673

Barnes, J. S., and Bennett, C. E. (2002). The Asian population: Census 2000 brief. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., and Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5, 323–370. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

Bloch, A., and Hirsch, S. (2017). “Second generation” refugees and multilingualism: identity, race and language transmission. Ethn. Racial Stud. 40, 2444–2462. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1252461

Boothby, E. J., Cooney, G., Sandstrom, G. M., and Clark, M. S. (2018). The liking gap in conversations: do people like us more than we think? Psychol. Sci. 29, 1742–1756. doi: 10.1177/0956797618783714

Burrmann, U., Brandmann, K., Mutz, M., and Zender, U. (2017). Ethnic identities, sense of belonging and the significance of sport: stories from immigrant youths in Germany. European J. Sport Soc. 14, 186–204. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2017.1349643

Busque, A.-M. (2021). Quebec language policy. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online at: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/quebec-language-policy (Accessed September 1, 2023).

Byron, K., and Landis, B. (2020). Relational misperceptions in the workplace: new frontiers and challenges. Organ. Sci. 31, 223–242. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2019.1285

Carlson, E. N., and Barranti, M. (2016). “Metaperceptions: do people know how others perceive them?” in The social psychology of perceiving others accurately. eds. J. A. Hall, M. Schmid Mast, and T. V. West (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 165–182.

Carlson, E. N., Furr, R. M., and Vazire, S. (2010). Do we know the first impressions we make? Evidence for idiographic meta-accuracy and calibration of first impressions. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 1, 94–98. doi: 10.1177/1948550609356028

Carlson, E. N., and Kenny, D. A. (2012). “Meta-accuracy: do we know how others see us?” in Handbook of self-knowledge. eds. S. Vazire and T. D. Wilson (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 242–257.

Clammer, J. (1999). Race and state in independent Singapore, 1965–1990: The cultural politics of pluralism in a multiethnic society. Aldershot: Ashgate Press.

Clyne, M. G. (2003). Dynamics of language contact: English and immigrant languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Communauté Vietnamienne au Canada, région de Montréal (2021). Qui sommes nous? Available online at: https://communautevietmontreal.com/histoire-de-la-communaute (Accessed December 12, 2023).

Denney, S., Ward, P., and Green, C. (2022). The limits of ethnic capital: impacts of social desirability on Korean views of co-ethnic immigration. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 1669–1689. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1797477

Dorais, L.-J. (2004). À propos de migrations transnationales: l’exemple de Canadiens d’origine vietnamienne. Rev. Eur. Migr. Int. 20, 49–73. doi: 10.4000/remi.2019

Dorais, L.-J., and Richard, E. (2007). Les vietnamiens de Montréal. Montreal, QC: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

Elsaadawy, N., and Carlson, E. N. (2022). Do you make a better or worse impression than you think? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 123, 1407–1420. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000434

Freed, J. (2023). Quebec’s language cops stripped character from my favourite Chinese eatery. The Montreal gazette. Available online at: https://montrealgazette.com/opinion/columnists/freed-un-soir-dhiver-dans-le-chinatown (Accessed September 1, 2023).

Gatbonton, E., Trofimovich, P., and Magid, M. (2005). Learners’ ethnic group affiliation and L2 pronunciation accuracy: a sociolinguistic investigation. TESOL Q. 39, 489–511. doi: 10.2307/3588491

Grancea, L. (2010). Ethnic solidarity as interactional accomplishment: an analysis of interethnic complaints in Romanian and Hungarian focus groups. Discourse Soc. 21, 161–188. doi: 10.1177/0957926509355366

Ibe, L. (2020). The languages of belonging: heritage language and sense of belonging in clubs and organizations. World Lang. Cultures 51, 1–35.

Kenny, D. A., and DePaulo, B. M. (1993). Do people know how others view them? An empirical and theoretical account. Psychol. Bull. 114, 145–161. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.145

Krause, C. (2011). Developing sense of coherence in educational contexts: making progress in promoting mental health in children. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 23, 525–532. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2011.637907

Kumar, N., Trofimovich, P., and Gatbonton, E. (2008). Investigate heritage language and cultural links: an indo-Canadian Hindu perspective. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 29, 49–65. doi: 10.2167/jmmd524.0

Kuo, W. H., and Tsai, Y.-M. (1986). Social networking, hardiness and immigrant’s mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 27, 133–149. doi: 10.2307/2136312

Lambert, M.-E. (2017). “Canada response to the ‘boat people’ refugee crisis,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online at: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-response-to-boat-people-refugee-crisis (Accessed December 12, 2023).

Le, T.-N. N., and Trofimovich, P. (2024). Exploring sociopolitical dimensions of heritage language maintenance: the case of Vietnamese speakers in Montréal. Canadian Modern Lang. Rev. 80, 22–49. doi: 10.3138/cmlr-2022-0078

Liu, H. (2014). Beyond co-ethnicity: the politics of differentiating and integrating new immigrants in Singapore. Ethn. Racial Stud. 37, 1225–1238. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2014.892630

Maloof, V. M., Rubin, D. L., and Miller, A. N. (2006). Cultural competence and identity in cross-cultural adaptation: the role of a Vietnamese heritage language school. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 9, 255–273. doi: 10.1080/13670050608668644

Martinez-Callaghan, J., and Gil-Lacruz, M. (2017). Developing identity, sense of belonging and social networks among Japanese immigrants in Scotland and Spain. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 26, 241–261. doi: 10.1177/0117196817706034

Mastroianni, A. M., Cooney, G., Boothby, E. J., and Reece, A. G. (2021). The liking gap in groups and teams. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 162, 109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.10.013

McIvor, O. (2020). Indigenous language revitalization and applied linguistics: parallel histories, shared futures? Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 40, 78–96. doi: 10.1017/S0267190520000094

Montrul, S. (2023). Heritage languages: language acquired, language lost, language regained. Ann. Rev. Linguist. 9, 399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev-linguistics-030521-050236

Nagy, N. (2021). “Heritage languages in Canada” in The Cambridge handbook of heritage languages and linguistics. eds. S. Montrul and M. Polinsky (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 178–204.

Park, S. M., and Sarkar, M. (2007). Parents’ attitudes toward heritage language maintenance for their children and their efforts to help their children maintain the heritage language: a case study of Korean-Canadian immigrants. Lang. Cult. Curric. 20, 223–235. doi: 10.2167/lcc337.0

Perera, N. (2015). The maintenance of Sri Lankan languages in Australia: comparing the experience of the Sinhalese and Tamils in the homeland. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 36, 297–312. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2014.921185

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Plonsky, L., and Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big?” interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Lang. Learn. 64, 878–912. doi: 10.1111/lang.12079

Sachdev, I., and Bourhis, R. (2005). “Multilingual communication and social identification” in Intergroup communication: Multiple perspectives. eds. J. Harwood and H. Giles (Berlin: Peter Lang), 65–90.

Salami, B., Salma, J., Hegadoren, K., Meherali, S., Kolawole, T., and Diaz, E. (2019). Sense of community belonging among immigrants: perspective of immigrant service providers. Public Health 167, 28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.10.017

Sammut, G. (2012). The immigrants’ point of view: acculturation, social judgment, and the relative propensity to take the perspective of the other. Cult. Psychol. 18, 184–197. doi: 10.1177/1354067X11434837

Sanders, J., Nee, V., and Sernau, S. (2002). Asian immigrants’ reliance on social ties in a multiethnic labor market. Soc. Forces 81, 281–314. doi: 10.1353/sof.2002.0058

Sandstrom, G. M., and Boothby, E. J. (2021). Why do people avoid talking to strangers? A mini meta-analysis of predicted fears and actual experiences talking to a stranger. Self Identity 20, 47–71. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2020.1816568

Sandstrom, G. M., Boothby, E. J., and Cooney, G. (2022). Talking to strangers: a week-long intervention reduces psychological barriers to social connection. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 102:104356. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104356

Seol, D.-H., and Skrentny, J. (2009). Ethnic return migration and hierarchical nationhood: Korean Chinese foreign workers in South Korea. Ethnicities 9, 147–174. doi: 10.1177/1468796808099901

Skinner, D., Valsiner, J., and Holland, D. (2001). Discerning the dialogical self: a theoretical and methodological examination of a Nepali adolescent’s narrative. Forum: qualitative. Soc. Res. 2:913. doi: 10.17169/fqs-2.3.913

Smolicz, J. J., Secombe, J. M., and Hudson, M. D. (2001). Family collectivism and minority languages as core values of culture among ethnic groups in Australia. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 22, 152–172. doi: 10.1080/01434630108666430

Statistics Canada (2023). Census profile, 2021 census of population (updated on March 29, 2023). Retrieved from Statistics Canada website. Available online at: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (Accessed December 12, 2023).

Tran, V. C. (2016). Ethnic culture and social mobility among second-generation Asian Americans. Ethn. Racial Stud. 39, 2398–2403. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1200740

Tran, V. H., Verdon, S., and McLeod, S. (2022). Consistent and persistent: successful home language maintenance among Vietnamese-Australian families. J. Home Lang. Res. 5, 1–19. doi: 10.16993/jhlr.43

Trofimovich, P., Lindberg, R., Bodea, A., Le, T.-N. N., Zheng, C., and McDonough, K. (2023). I don’t think you like me: examining metaperceptions of interpersonal liking in second language academic interaction. Languages 8:200. doi: 10.3390/languages8030200

Welker, C., Walker, J., Boothby, E., and Gilovich, T. (2023). Pessimistic assessments of ability in informal conversation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 53, 555–569. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12957