- Global Governance, Balsillie School of International Affairs, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

Moving towards a more sustainable, healthier, and equitable food future requires a significant system transformation. Policies to achieve this transformation are notoriously difficult to achieve, especially where actors with conflicts of interest are involved in governance. In this paper, I analyze how corporate actors frame issues inside a process to develop Front-of-Pack Labelling across the Caribbean. Focusing on three major framing strategies, I show how industry actors argued 1) (falsely) that FOPL would privilege Chilean food suppliers; 2) that FOPL would constitute a major transgression of international trade law; and 3) that a regional public health organization (the Pan-American Health Organization) is an illegitimate influence on the policy. Together, these three framing strategies reconstruct the policy problem as one of trade rather than public health. I argue that the resulting narrative is both a product and a function of the discursive power food companies wield in the standard-setting process and provide empirical detail about how food companies act to prevent policy attempts facilitating food systems transformation.

Introduction

In response to ever-climbing rates of non-communicable diseases, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) Public Health Agency (CARPHA) recommended instituting Front-of-Pack Labelling (FOPL) across the region (CARPHA, 2017; Samuels et al., 2014). FOPL schemes aim to inform consumers of the healthfulness of food products more easily than the traditional “back panel,” thereby improving consumer choices in the retail food environment. Many states have now moved or are moving towards implementation of FOPL (Kanter et al., 2018). Public health advocates in CARICOM encouraged policymakers to implement FOPL to honour the commitments the Heads of Government had made to prevent NCDs in the region.1 As a result, a delegation from CARICOM met with Chilean counterparts in 2017 to learn about and eventually adopt a Warning Label-style FOPL for CARICOM (PAHO, 2019). While the policy had significant regional political support, there is no supranational health body with the power to implement policy across the region and so instead, FOPL moved into the regional standard-setting process to be implemented. In the summer of 2018, FOPL underwent an ideational shift, from a public health policy solving a public health problem, and transformed into a food labelling standard inside a trade-focused venue, ultimately reframing FOPL as a trade problem.

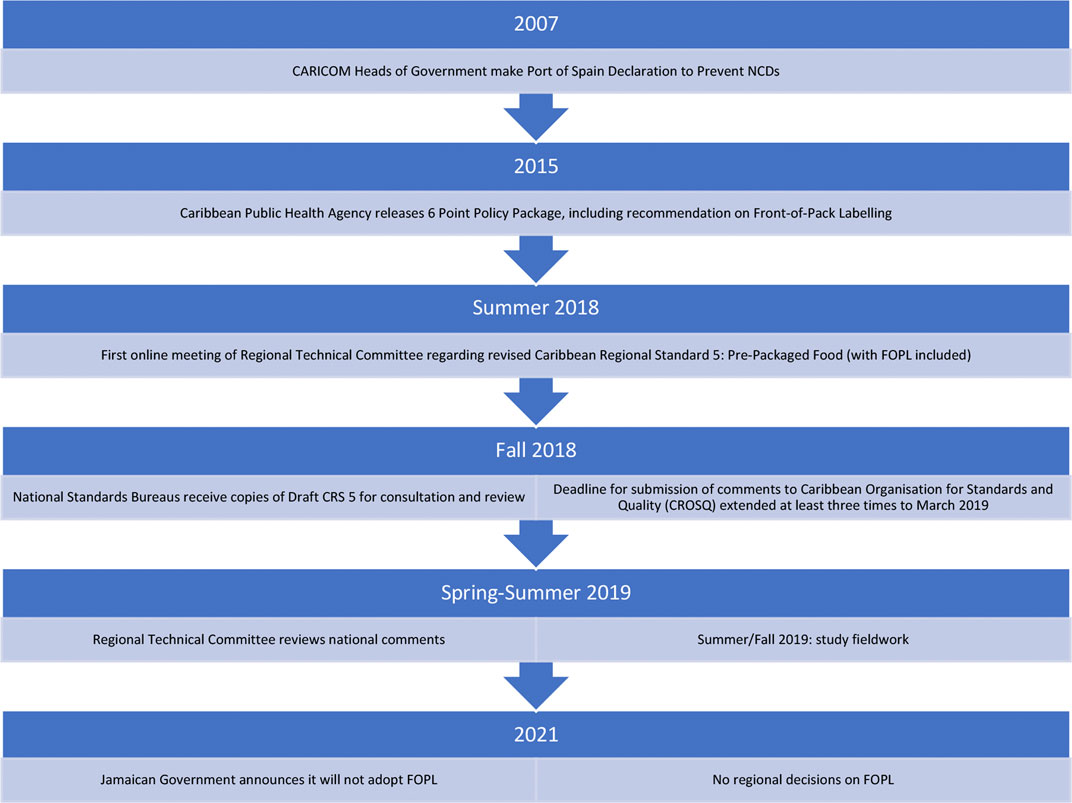

At the time of writing, the outlook of FOPL in CARICOM is uncertain. Since its entry into standard setting, the labelling scheme has been delayed many times, national committees have failed to reach consensus positions in favour of labelling, and, most recently, the Government of Jamaica has signalled it will not adopt FOPL (Chung, 2021)—a major blow to the regionality efforts of the original public health policy (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. PAHO. (n.d.). Front-of-package labeling—PAHO/WHO|Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved October 16, 2021, from https://www.paho.org/en/topics/front-package-labeling.

Standard setting is an internationally recognized process that began with and evolved around industry needs to harmonize technical expectations. Referenced in World Trade Organization articles and agreements, standards are integral to international trade law (Boza et al., 2019; Thow et al., 2019). FOPL was effectively transferred from the authority of public health experts in a “public” venue, into a venue intended for the promulgation of industry interests and trade—a “hybrid” venue (Clapp, 1998)—where the private sector has significant influence. Here, industry actors have detailed knowledge about process rules and operating culture (Murphy, 2015), leading to the successful frame-shift of FOPL from a health solution to a trade problem. FOPL—intended to curb sales of ultra-processed foods—is in direct conflict with the food industry’s profit from the sales of these food products—leading to a significant interest conflict, but one where industry actors have the upper hand.

In this article, I use a frame analysis to describe three overarching arguments used by industry actors to frame FOPL to suit their interests in the national standard-setting committees of the overall regional CARICOM standard-setting process. Together, these arguments suggest a complete reframe of the FOPL policy from a health solution to a trade problem—and demonstrate discursive power exercised by industry actors. In the discussion I try to disentangle the sources and contribution of authority to framing and the resulting effect on the production of discursive power in standard setting for a food systems policy. Finally, I examine why corporate actors have been so much more successful in promoting their vision of reality than health advocates and why a process where this is the case was chosen to develop and adopt FOPL.

Materials and Methods

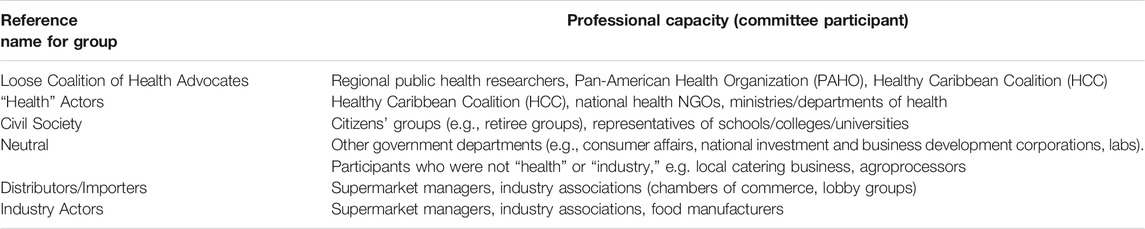

This research project was undertaken at the request of public health researchers in CARICOM. In 2015, researchers began a 36-month project to measure government action on NCD prevention against the regional political commitments (Samuels et al., 2017; IDRC, 2018). Following this research project and the publication of the CARICOM Public Health Agency’s Six-Point Policy Package, public health researchers expressed interest in understanding the next steps—what they described as “the black box of regional policy implementation.” This research project was a response to this request, beginning in 2019 as part of a research award at the Canadian International Development Research Centre. I conducted 32 semi-structured interviews with 31 unique participants involved in national and regional standard setting in-person in St Kitts and Nevis and Barbados in July and August 2019, and via phone with participants mostly from Jamaica from September to November 2019. Participants were either technical officers with standard-setting organizations or committee members. Committee members were categorized into overlapping groups for writing to maintain confidentiality where needed (see Table 1 above).

I conducted three additional interviews with related subject matter experts to further inform the analysis. While 11 member-states of CARICOM were “active” in standard setting for FOPL, three states—St Kitts and Nevis, Barbados, and Jamaica—were chosen as case studies to illustrate the different characteristics of the full CARICOM membership. Jamaica and Trinidad are the two largest food manufacturers and exporters in the region, though Jamaica has the larger population. St Kitts and Nevis is one of the smallest states in CARICOM, has little-to-no food manufacturing and export, and has only recently become integrated into international standard-setting infrastructure. Finally, Barbados represents a good middle-ground case, where there is some small local food manufacturing, little export, and medium-sized (for the Caribbean) population. Barbados is also where the CARICOM Regional Organisation for Standards and Quality (CROSQ) is located.

I use a majority vote at the regional standard setting level as a proxy signal for the intermediate outcomes of success or failure. In the summer of 2019, after a suggestion to delay FOPL indefinitely (see Section 4 for more details) all member states submitted votes. Barbados, highly supportive, voted to keep FOPL. St Kitts and Nevis voted to delay indefinitely. Jamaica’s national committee could not achieve a consensus position to vote and thus abstained from the vote. Since then, Jamaica’s government has announced a national rejection of FOPL in 2021 (Chung, 2021), while Barbados and St Kitts have not announced any decisions.

Interview data was coded in January and February of 2020, using a grounded theory approach (Charmaz, 2006) in Nvivo software. An initial round of coding produced 15 major themes emerge, and in subsequent coding rounds three more higher-level codes were added as well as sub-codes. A second coder also reviewed the data to determine whether codes were consistently applied (Schreier, 2012). The three discursive framing strategies outlined below are taken from the codes from Resistance Strategies > Reframing, which were determined by first coding for participants’ positions on FOPL (positive, negative, neither) and then identifying strategies of resistance or support. Neutral participants who were compelled or persuaded by both resistance strategies and some support strategies are referred to throughout the following analysis. Additional desk research took place in 2020 to fill in remaining questions, including significant document review from relevant international organizations regarding standard setting (WTO, ISO, CROSQ) and health policy making and sharing (PAHO, WHO).

This paper uses frame analysis to help fill the gap that exists around corporate influence in food policymaking: it examines discursive power as it is actioned through a black box of hybrid private-public policymaking. At the time of writing (August 2021), the Government of Jamaica announced that it would not move forward with adoption of FOPL. The paper then also explores a dynamic that is frequently understudied—why do some food systems policies fail? I argue that in this case, the food industry successfully reframed FOPL from being a public health solution to being a trade regime conflict. The sources of the food industry’s discursive power are the significant knowledge of the standard-setting regime and expert authority inside the process itself.

Framing and Discursive Power

In the study of politics, power is both a foundational and debated concept. “A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do” (Dahl, 1957) has been the frequent starting point for discussions around power. Over time, ideas around power have evolved and now often consider more “faces” (Bachrach & Baratz, 1963) or “views” (Lukes, 1977). A growing literature in the study of global governance and international political economy describes the power of transnational corporations (Cutler et al., 1999; Falkner, 2008; Green, 2013; Hall and Biersteker, 2002). Corporate influence in food and agri-food governance has been examined both by political economists (Clapp and Fuchs, 2009; Falkner, 2009; Fuchs, 2005; Fuchs and Kalfagianni, 2009) and by those who address corporate power and conflict of interest from a public health perspective (Baum et al., 2016; Moon, 2019; Thow et al., 2019; Friel, 2020; Milsom et al., 2020). The vast array of spaces and approaches where influence happens means that empirical detail around exact pathways of power operationalization can be lacking.

Clapp and Fuchs (2009) proposed a three-dimensional view of corporate power that focuses on the interplay of instrumental, structural, and discursive facets of power, aiming to consider both the nature of corporate power in the global agri-food governance system and to examine it in various topic areas. This study contributes to this growing body of research on corporate power in food governance by focusing specifically on discursive power and the strategies of framing used by food companies in CARICOM to prevent FOPL adoption. Fuchs (2007) describes discursive power as “the capacity to influence policies and the political process as such through the shaping of norms and ideas” (p. 139). Discursive power helps illustrate the ways that policy decisions are often made as a result of “discursive contests over frames” (Fuchs, 2007) and the ways that actors link designated problems to different categories by associating them with specific fundamental norms and values (Kooiman, 2002).

A component of corporate power in agrifood governance (Clapp, 2009), discursive power is present when policy issues are framed, how actors are framed and how broader political and social norms can be influenced. Fuchs and Kalfagianni (2009) write that some of the discursive activities of businesses include: framing policy issues, framing actors, and the impact of broad societal and political norms (Fuchs and Kalfagianni, 2009; Fuchs 2005). Scientific and technical discourses around biotechnology and genetically modified organisms are existing examples of framing of policy issues in global food governance (Görg and Brand, 2006; Newell and Glover, 2003). I use the tools of frame-analysis, developed in communication studies, to illuminate the empirical pathway of discursive power in standard setting in CARICOM.

From frame-analysis literature, I argue that FOPL in CARICOM was originally “framed” as a public health solution, and that a successful “frame-shift” took place to reframe it as a trade problem. I use Entman’s definition of framing—that “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient … in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (1993, p. 52). While usually referencing communicating texts, Entman’s definition suggests frames as tools with intention to promote specific versions of reality (Vliegenthart and van Zoonen, 2011, p. 107). Emphasizing intentionality and promotion of a particular viewpoint makes framing analytically useful to describe a pathway of discursive power. That is, it helps to answer the question of how discursive power is operationalized.

This analysis takes two assumptions from the international political economy literature on food governance and corporate power. First, I assume that the standard setting process in CARICOM, directed by the CARICOM Organisation for Standards and Quality (CROSQ), like other standards organizations, is a venue for decision making that is a hybridized regime of public and private influence (Clapp, 1998) and second, that interests can be overlapping and reinforcing. Standard setting began, and has always, propelled the interests of private industry (Murphy, 2015). The addition of national governments in standard setting though, as well as standards’ creep into traditionally public domain areas like environmental management, make tracing and delineating whose interests win out challenging. While standard setting for food labelling has been primarily dominated by the Codex Alimentarius—jointly facilitated by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)—which we might consider a public or intergovernmental organization, national interests are still pursued as they are in other intergovernmental spaces. For example, when regional standards on coconut water might serve a wider economic interest to CARICOM. Caribbean states may be more likely to push for an international standard in this arena (see Büthe and Mattli, 2011). Untangling in whose “interest” a standard is pursued is thus difficult, but this study works towards unravelling the pathways that those with power can use to achieve their interests.

Results: Food Industry Framing Strategies

The food industry used three major framing strategies, to different effect in the different case study countries, to contribute to an overall reframe of FOPL from a public health solution to a trade regime conflict. These strategies are the operationalization of discursive corporate power in standard-setting. The strategies are explored below with direct quotes from interview participants.

Framing Strategy 1: Privileged Trading Partners

In all three framing strategies, industry actors and some other “neutral” participants either ignored or were unaware of its underlying roots as a health policy, instead focusing on the ways that FOPL conflicted with trade norms and rules. In this first strategy, both opponents and neutral participants reacted to a belief that Chile would receive preferential trading conditions, since Chile had already implemented a similar style of FOPL (Corvalán et al., 2021).

“… Industry you know, said to us … you are then explicitly saying that we’re going to give preferential treatment to Chilean goods over the goods that we currently import from other places which would then have to be labeled.” Participant 4, Barbados Ministry of Health, (22/08/19).

Implicit in the quote above, and in all three case study countries, participants on the national committees raised a common question: Why should CARICOM member-states privilege Chile as a trading partner? The idea of a trade advantage or privilege is akin to the “first mover advantage” theory common in standard setting literature (Büthe and Mattli, 2011). Since Chilean suppliers had already adopted the “High-In” black octagon format and had therefore adapted to the financial and social costs of this labelling regime, we might expect Chilean exporters to have an advantage over other external suppliers who would only now need to take on the social and financial costs to comply.2 In other words, they would have an advantage as the “first mover” in the market.

While neutral actors usually framed FOPL as a strange, or even baffling position to take, industry actors were more likely to frame it as irresponsible, however both frames rested on the idea that Chile is a relatively minor trading partner with CARICOM.

“… this is why I’m skeptical about the Chile one because we don’t do that much business with Chile.” Elsa Webster, Barbados Association of Retired Persons (Participant 3, Civil Society, 23/08/19).

CARICOM’s small market size was a major reason that non-industry committee members, like Participant 3 and other civil society members, were compelled by the idea that Chile should not be given any trade advantage. Participants described the parallel claim that CARICOM would not represent a large enough market to dictate rules to bigger trading partners, resulting in the risk that trade with Chile would increase while other large-scale international suppliers from the United States and United Kingdom might simply choose to forgo the CARICOM market. In each case study country, at least one representative of domestic food distributors argued that their United States and United Kingdom suppliers would rather exit the market altogether than comply with new labelling requirements. Distributors and their representatives described the loss of imported food products as an assured certainty, in that suppliers would simply not think the CARICOM market was worth the added labelling costs. As such, international suppliers would either 1) forgo the CARICOM market entirely, implying a loss of access to products for customers; or, in some cases, distributors conceded that 2) suppliers would pass the increased costs of labelling onto the distributors and/or consumers. The most extreme framing of the risk of losing overseas suppliers came from one distributor in St Kitts and Nevis. This distributor reframed FOPL as a food security issue by implying the low levels of food production in most Caribbean islands:

“If this was implemented, then every product imported from the US, Great Britain, or Canada, that does not comply, would automatically have to be exempted or else you would die of starvation.” Participant 18, Distributor (12/08/19).

The distributor was adamant that without exempting United States, United Kingdom, and Canadian suppliers’ compliance with FOPL, there would simply not be enough food available, again suggesting that there was no scenario where these suppliers might simply comply with new labelling requirements. Going without food imports from traditional suppliers seemed especially sensitive because of the English-speaking Caribbean’s historical-cultural association with the United Kingdom and the cultural attraction to the United States. In each study country, committee members explicitly discussed consumers’ desires to eat foods from these two regions over foods that may be imported from Chile or other South American countries, which is described in more detail below. In this case, if a trade advantage must be provided (or in other words, if a labelling scheme must be implemented) participants often thought it would be preferable to use a labelling scheme from a more established trade partner.

“And they have to look and see, where do we do our trade business with? Are we doing our trade business with Chile? Are we doing trade business with businesses that subscribe to the Chilean model? Or is our trade partner, our largest trade partner the United States? Where do we get our aid from? Not from Chile.” Participant 18, Distributor (12/08/19).

While importers and distributors were the most outspoken about this issue, emphasizing that FOPL would privilege Chilean suppliers, the framing was also picked up by other, non-industry stakeholders on the national committees as both inconceivable and somewhat baffling. Non-industry committee members were often unclear on why the “Chilean format” (as it was broadly referred to) had been chosen, demonstrating that FOPL had been reframed as a trade problem, without its public health origins, as it entered the standard setting process. Without a clear understanding of the public health policy goals for choosing the Chilean format, the decision was perceived by participants as strange, even amongst those who were supportive of FOPL in general. Even some health advocates on the committees considered choosing a Chilean labelling format to be somewhat peculiar, enabling more space to reinforce industry claims of an unfair trade advantage.

Other committee members, including local manufacturers and cottage industry representatives agreed that a United Kingdom or United States labelling system over Chilean labelling would make the most sense. Participant 29 (24/09/19), a neutral committee member, explained that local Jamaican manufacturers did not want to use a form of labelling that was in use in South America, since their primary exports were going to the United Kingdom and United States. Manufacturers in Jamaica preferred to use the same label that was used in the United Kingdom (currently, the Multiple Traffic Lights3) or the United States (currently no FOPL). At the same time, other participants described industry actors’ concern about the level of trade done with Chile compared to the United Kingdom and United States:

“Right, so the thing about it is that [industry] said that they’re not opposed to a Front of Package labeling system, because there are a number of labeling systems out there in the world. However, what [they] are opposed to is this particular system that we have selected … And why was the Chilean model [chosen when] we have low trade with Chile? [When the] principal trading partners outside of the region, [are the] UK, and the US … ?” Participant 1, Regional Neutral Participant, (23/08/19).

One reason these arguments were especially compelling seemed to come from beyond the strong trade relationships and was related to a perception of both quality and cultural preferences. Foods from the United Kingdom and United States were frequently framed as superior (Participant 18, 12/08/19), reinforcing the argument that Chile should not be the recipient of a trade advantage. In Barbados especially, there is a strong link with United Kingdom products and heritage, including an exclusive relationship between Waitrose (a high-end United Kingdom grocery retail chain) and Massy’s (a local Barbadian grocery chain). This was seen as an advantage for the tourism economy, which is largely dominated by British tourists (Participant 15, 21/08/19).

The appeal of United Kingdom products in Barbados was also intimately tied to a perception of quality and affluence since British products are significantly higher cost than local equivalents.

“… there’s a perception that the quality of the food is different, in terms of the taste and everything else … one may argue, yes, because you’re talking about a developing country versus a developed country, the standards are different in the UK than they are in the Caribbean. The inputs are different, the way the manufacturing processes are different. So, the final products should differ. And that is what is representative of our psyche. We think that something from a developed country, [is] way more better than something from a less developed country.” Participant 15, Neutral Participant (21/08/19)

Products emanating from anglophone countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, and to a lesser extent, Canada, were generally considered more desirable than products from Chile, making the choice of labelling scheme seem ill-considered to most participants. In St Kitts and Nevis, reported preferences for the two anglophone country suppliers were mixed, while in Jamaica, more committee members expressed concern that US suppliers would be disadvantaged to Chilean producers. The idea that Chilean trading partners would receive an advantage over others proved persuasive to both non-industry and non-distributor stakeholders on all national committees though.

A framing strategy that focuses on rejecting labelling based on trade preferences is only effective because of the pre-existing norms and concerns that operate in standard-setting venues and processes. By framing opposition to FOPL around trading preferences, industry actors strategically used both the norms and concerns of standard-setting—particularly around providing an equal playing field for trade; and committee members’ underlying desires for foods associated with different countries, to bolster and legitimize the rejection of FOPL. By focusing on the trade concerns of the committees, industry actors were able to reframe FOPL as FOPL not as a public health policy solution to a major health crisis, but instead as a baffling advantage to an obscure trade partner.

The Chilean trade advantage was perceived as a legitimate frame by all committee members, not simply the members who had trade backgrounds or were from industry. The perception of legitimacy illustrates that this frame carried real weight, or authority. Until the summer of 2018, FOPL was considered a public health policy solution to reduce NCDs in CARICOM. By appealing to preferences for United States and United Kingdom products especially—and suggesting a risk of losing access to these products—the Chilean trade advantage framing persuaded many committee members (who were mostly ambivalent about FOPL otherwise) that it was an unreasonable advantage. Complicating matters, this is both in line with international trade rules of non-discrimination amongst trading partners (Boza et al., 2019), and yet acts against this norm when cultural preferences come into consideration. Importantly, these same committee members were often unaware that FOPL had transferred into standard setting as a public health policy at all. The invisibility of the public health roots of FOPL gave the Chilean trade advantage framing its “baffling” quality, and likely contributed significantly to opposition.

Given the simplicity of the Chilean trade advantage narrative; the appeal and familiarity with major suppliers’ products; and the absence of evidence provided that the chosen “Chilean format” was an effective public health policy tool; it is unsurprising that this framing became the most cited reason for resisting the regional standardization of FOPL in CARICOM. The argument served the overall discursive strategy of reinforcing existing private sector authority by ignoring and therefore erasing the public health (and public authority) origins of FOPL, legitimizing trade concerns as the only concern that should be considered.

Framing Strategy 2: Technical Barriers to Trade

While the Chilean trade advantage narrative frames FOPL rests on the shaky ground that Chile will have a first mover advantage and other major trading partners will simply forgo the market, another more sophisticated narrative also bolstered the legitimacy of trade discourse on FOPL in CARICOM. Industry actors argued that FOPL would, assuredly, constitute a Technical Barrier to Trade (TBT). Importantly, Chile’s legislation, including FOPL, was intensely discussed and ultimately survived at the TBT Committee of the World Trade Organization (WTO), suggesting that CARICOM’s FOPL would also be unlikely to also constitute a TBT.4 Similar to the Chilean trade advantage claim, this framing relies on the pre-existing norms around trade in the national committees. WTO rules form the basis of the standard-setting process itself, providing significant authority and legitimacy to any claims that infer it.

All food industry actors who participated in this study framed FOPL as a certain TBT, but the Chambers of Commerce in (at least) Barbados and St Kitts and Nevis were especially forceful in their portrayal of FOPL as a transgression of the TBT agreement. The claim was also compelling for most non-industry committee members who were familiar with standard setting and therefore accustomed to the WTO’s authority and rules. Food industry actors argued that an FOPL scheme, especially one as stringent as the “High-in” Warning Label model, would certainly constitute a Technical Barrier to Trade and therefore be rejected under WTO rules. Article 2.2 of the Agreement on TBT states that:

“Members shall ensure that technical regulations are not prepared, adopted or applied with a view to or with the effect of creating unnecessary obstacles to international trade. For this purpose, technical regulations shall not be more trade-restrictive than necessary to fulfil a legitimate objective, taking account of the risks of non-fulfilment would create.” (Article 2.2, Preparation, Adoption and Application of Technical Regulations by Central Government Bodies)

Under the Agreement on TBT, the WTO considers standards set by relevant international standards bodies as “standards,” whereas those set by governments, intergovernmental organizations or the UN are considered technical regulations (Boza et al., 2019; Clapp, 1998). Therefore, any variation—in the form of legislation, policy, or rules—from international standards are considered technical regulations (Participant 1, August 23, 2019). Codex Alimentarius, a body jointly facilitated by WHO and FAO, is responsible for phytosanitary and other food safety standards (Henson and Humphrey, 2009). Since it was explicitly recognized by WTO for these standards, Codex is also an approved international standard setter for many food issues, including food labelling standards. The important distinction is that international standards can never be considered a TBT, but technical regulations (legislation, policy, or rules) instituted by non-standard setters (e.g., governments) may be considered a TBT.

The standard investigated here that includes FOPL is a revision to an existing Caribbean Regional Standard (CRS) 5 on Pre-Packaged Food Labelling, which, although existing as a regional standard, has not been adopted uniformly across CARICOM. The existing CRS 5 was introduced in 2010 as a regional standard, however, it is mostly in accordance with the Codex General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Food (CXS 1-1985, revised in 2018). The revision to CRS 5 proposed in 2018 added a “High-In” Warning Label style FOPL similar to Chile’s, which has since become a controversial focal point of the process. Including FOPL in CRS 5 is framed as a transgression of TBT agreement by industry and other stakeholders, since it moves CRS 5 further from the Codex International Standard.

Although many private sector actors in the process vocalised this argument, the representatives of the Chambers of Commerce in Barbados and St Kitts stood out in their framing that FOPL in the “High-In” Warning Label format would, unequivocally, constitute a TBT (see below for an explanation of the counterargument) and therefore be challenged at the WTO. While the Chamber of Commerce was mostly absent from national committee meetings in St Kitts therefore did not make any formal comments or complaints in this regard, their representative did not view FOPL as a legitimate regulation inside the WTO regime. Similarly, the Chamber of Commerce in Barbados was described by other participants as “very loud” (Participant 31, 24/07/19) in meetings using the same framing. Many committee members framed FOPL as a certain TBT, especially those from the food industry, using the weight of the TBT Agreement inside the standard-setting process to legitimize this claim. At times, industry actors went so far as to claim they were being helpful in protecting countries from having to fight a potential WTO challenge:

“They [industry] go into [the] WTO argument. This, this is a WTO problem and Barbados will get in trouble as a country with WTO - if you go in this direction … we just want to help you. We just want to protect you. Thanks.” Participant 4, Barbados Ministry of Health, (22/08/19)

By portraying these efforts as helpful, and given the authority of WTO and TBT inside standard setting, industry actors, particularly in Jamaica and St Kitts, successfully portrayed that there was no ambiguity around FOPL constituting a TBT. Many non-industry committee members also accepted this portrayal. In reality, transgressions are only confirmed through WTO challenges (Foster, 2021), and the evidence of Chilean FOPL points to a low likelihood that CARICOM FOPL would be considered a TBT (Boza et al., 2019). Certainty regarding what is or is not a TBT then, rests with legal experts and ultimately, the results of a WTO challenge. As is described below, the argument put forward by industry has been countered by some legal experts. Since there is no legal consensus as to whether FOPL in this format constitutes a TBT, and since ultimate certainty would only result from a WTO challenge, this argument results in a risk calculation of three possible outcomes for implementation in the current format (as a technical regulation):

1) it could be challenged, deemed a TBT and then dismantled in response;

2) it could be challenged, deemed a legitimate technical regulation and remain standing (see below);

3) or, it might remain unchallenged—leaving it to stand and its TBT status uncertain.

The strategy put forward by private sector representatives that the “High-In” Warning Label is unequivocally a TBT, is therefore, in reality, more ambiguous than industry actors have portrayed, and is perhaps even unlikely given Chile’s experience (Boza et al., 2019). At the same time, the framing was compelling to most members of the committees.5 Government officials in Barbados and Jamaica also remarked that their trade department colleagues’ lens suggested an indisputability around FOPL as a TBT, making it both illegal and unnecessary, and further dismissing it outright. Committee participants from government reported their trade colleagues were indifferent to any potential health rationale, signaling that they understood trade rules as inherently more authoritative than public health policies in this venue. That the FOPL in CRS 5 would be considered a TBT and not be allowed under trade rules was expressed by other non-industry committee members—even those who were supportive of FOPL—demonstrated that this framing strategy was perceived as inherently valid—displaying the way that underlying authority of trade rules and the WTO shaped perceptions of legitimacy in the standard setting space.

Still, while all stakeholders acknowledged the potential validity of the TBT argument, not all were resigned to its purported veto. In Barbados, the Ministry of Health hired an outside and independent consultant with experience in tobacco labelling issues in Australia6 to investigate the TBT argument. Similarly, the Healthy Caribbean Coalition, a health NGO and network in the region, worked with a lawyer and professor based at the University of the West Indies (UWI) Cave Hill. Both came to similar conclusions: the second sentence of Article 2.2 (above) enables governments to create technical regulations that serve legitimate objectives, as long as these are not “more trade-restrictive than necessary.” These experts argue that FOPL is filling a legitimate objective in the Caribbean (by reducing the incidence of NCDs) and would therefore be allowed under the Agreement on TBT. This argument also seems to have been born out by Chile’s experience managing concerns at the TBT Committee meetings at WTO (Boza et al., 2019).

Whether considered legitimate or not, the fear of a WTO challenge is frequently sufficient to steer countries away from action. Just as international environmental management standards can become a ceiling rather than a baseline for progressive action (Clapp, 1998), if no action is taken on FOPL because of the perceived risk of a WTO challenge, international standards can become de facto ceilings constraining domestic policy space (Koivusalo et al., 2009; Labonté, 2019) for individual countries. Advocates for FOPL anticipated the need to prepare for a WTO challenge should FOPL be adopted across CARICOM. Since a reduction in NCDs, a population-level public health goal, is nearly impossible to concretely connect to any one variable and therefore act as the legitimate objective achieved by FOPL, advocates have started to strategize 1) an appropriate “legitimate objective” and 2) the actions required to generate evidence that would justify that objective. There is some question among these circles as to whether evidence generated in Chile (see Correa et al., 2019) would be sufficient to justify similar FOPL in a different regional context, or whether Caribbean-specific (or even country-specific) evidence generation would be required. If this is possible, the “legitimate objective” must be tied to the evidence provided—this means the “legitimate objective” might be a reduction in processed food product purchases (Foster, 2021). The anticipated work involved is onerous and lends some credibility to industry’s claim to help countries avoid an arduous process.

When claiming FOPL is an indisputable TBT, the trade frame nullifies any opportunity for FOPL in CRS 5 or beyond. The underlying cognitive legitimacy (Cashore, 2002) associated with the WTO and the TBT Agreement—a taken-for-grantedness within the standards process—allowed this discursive strategy to be persuasive with all committee members, even those who were supportive of FOPL more generally. Advocates who believed FOPL could win a WTO challenge still viewed TBT as a legitimate line of reasoning and were taking precautions to prepare for that eventuality, signalling the perception of power of the WTO and its rules. By applying the TBT argument and emphasizing the possibility of a WTO challenge, industry members of the national committees were conceptually venue-shifting (Keck and Sikkink, 1998; Baumgartner et al., 2019) by insinuating the inevitable consequences if FOPL moved forward. Taken together, the Chilean trade advantage and the TBT argument both shifted FOPL entirely away from a framing of public health and towards a framing of trade problems—and therefore into a conceptual space where the predominance of the WTO and international trade rules can nullify all opposing arguments.

Framing Strategy 3: Legitimate vs. Illegitimate Standard Setters

“So, one of the industry arguments was PAHO has no legitimacy here. Right? PAHO cannot create an international standard for food or for trade. ‘Because PAHO is not a standard setting body, not established as a standard setting body. So, if you’re going to use thresholds as defined by PAHO, then we can’t accept it.’” Participant 4, Barbados Ministry of Health, (22/08/19)

In the third framing strategy, food industry actors reframed some actors as illegitimate, further reinforcing the authority of the WTO and trade rules and completing the frameshift of FOPL away from public health and towards trade. Incoherence in policy communities can lead to a lack of consensus (Bernstein, 2011): in this case, public health actors were considered exogenous and illegitimate. Whereas in other spaces the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) was viewed as a policy champion, this framing successfully negated PAHO’s influence over FOPL. This discursive strategy went further than simply erasing the public health origins of FOPL, it dismissed their expert authority entirely.

All standards bodies use the Code of Good Practice for the Preparation, Adoption and Application of Standards in Annex 3 of the Agreement on TBT. Since this code is the basis for all standards development, not just the current CRS 5 revision or food labelling, familiarity with the process varies between those stakeholders who have taken part in the process before and those who were consulted strictly because of their technical relevance to FOPL (e.g., health NGOs). As such, stakeholders familiar with the standards process had a different sense of who is or who is not a legitimate actor (or authority) compared with the new participants who were unfamiliar with the process (and also largely supportive of FOPL).

The illegitimacy of some actors in the CRS 5 revision process were portrayed in two ways:

1) Some actors do not have a designated, legitimate role in the process; and/or,

2) Some actors do not have the correct jurisdictional designation to participate in the process.

In the first instance, PAHO was the target of this argument. Committee members who were familiar with standard setting, and particularly familiar with food labelling, were aware of the Code of Good Practice and the processes associated with it. As such, they are accustomed to deferring to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), or, in the specific case of food and food labelling—Codex.7 The revisions to CRS 5 revision that contained the FOPL format taken from a separate country (Chile) and critical nutrient thresholds designated by PAHO, was portrayed as outside of the usual operating norms.

And many of us said, “Well, you know, we’re not understanding the logic here, where PAHO is kind of pushing this edit to the standard—PAHO is part of WHO?” Participant 5, Representative of Jamaican Firm, (18/09/19).

Participants who were not accustomed to the standards process, such as those being consulted for their “health” perspective (e.g., government health departments or local NGOs), usually accepted PAHO as a legitimate actor with expert authority to set nutrient thresholds, while industry groups rejected PAHO as a standard-setter because of its detachment to the standard setting regime.

“So, one of the industry arguments was PAHO has no legitimacy here. Right? PAHO cannot create an international standard for food or for trade. “Because PAHO is not a standard setting body, not established as a standard setting body. So, if you’re going to use thresholds as defined by PAHO, then we can’t accept it.” Participant 4, Barbados Ministry of Health, (22/08/19)

Framing PAHO as exogenous to standard-setting processes usefully negated the expert authority of this organization. By framing their participation in standard-setting as illegitimate, the critical nutrient thresholds set by PAHO also became illegitimate. These thresholds were simply “too tight” according to industry participants (Participant 2, 18/09/19), suggesting the underlying reason behind framing PAHO as an inappropriate standard-setter.

Again, the operating norms and culture of standard setting create the environment where these claims are both relevant and persuasive. As quoted above, industry understood that PAHO is a regional body of the WHO, which, together with the FAO, facilitates the Codex Alimentarius. Codex is deemed legitimate, whereas PAHO is not. From the perspective of industry and neutral participants who are used to being part of the standard-setting community then, the legitimacy of a standard-setter is drawn more from its position in the standard-setting regime, whereas for non-accustomed participants, legitimacy was derived from technical expertise. Framing PAHO as an illegitimate actor was persuasive then because other participants were used to dealing with Codex or other standard-setting bodies, and PAHO seemed outside of this norm.

PAHO was also considered illegitimate because of its regional focus. Industry actors underlined its relationship with the WHO and its global, or regional reach. In contrast, these stakeholders underlined the national relevance of the standard under questions. Although the standard is put forward by the regional standards body, national standards bureaus still have significant control over the consultation process and national governments retain the right to make standards mandatory or leave them as voluntary (through national adoption and legislation). In this case, committees are used to operating as national committees, with less regard for regional harmonization or consideration. This is especially true in the case of Jamaica, which has the most developed standards regime of the three case study countries and whose labelling standards often become a default standard across CARICOM because of their leading manufacturing capacity and population size (products from Jamaica are consumed across CARICOM). As such, industry stakeholders characterized PAHO’s global and regional ties as being pushed through CROSQ and into domestic processes,8 grouping PAHO with other “private influences”.

“So the effectiveness of that [national] subcommittee, and that overall committee in terms of influencing some of these things that CROSQ ended up taking on were, made it more of a regional CARICOM issue before it became a Jamaican issue. And that approach … from my read on the situation was led by some private influences as well as PAHO. Kind of pushed into CROSQ you, you know, the standard development for this particular standard we’re discussing.” Participant 5, Representative of Jamaican Firm, (18/09/19)

While this argument tended to be along health versus industry lines, there was one exception. The Healthy Caribbean Coalition, the transnational advocacy network responsible for alerting members of the Non-Communicable Disease alliance to FOPL as part of the CRS 5 revision, was also challenged for this transgression of jurisdictional lines. Since the Healthy Caribbean Coalition is considered a regional organization, their initial application to sit on the national committee in Barbados, where they are based, was denied (though it was approved after the first introductory meeting). The Healthy Caribbean Coalition’s presence, while successful in pushing the issue forward, was perceived by some other FOPL supporters for its “aggressive” approach (Participant 4, 22/08/19). The Healthy Caribbean Coalition used strategies common in transnational advocacy networks, including bringing together counterparts in other countries in CARICOM, educating partners on the standards process and providing them with common industry arguments and rebuttals. This regional activity was perceived by a few involved as being in contradiction to the ‘national’ process – though interestingly, similar evidence of coordination among national Chambers of Commerce did not seem to garner the same criticism. It is notable however, that industry actors did not target the Healthy Caribbean Coalition as an illegitimate actor in the way they targeted PAHO’s legitimacy. There are two potential reasons for this: 1) because when the Healthy Caribbean Coalition sat on the Barbados committee, they were chosen by Barbadian health organizations to represent all domestic health organizations and so could operate more like a national entity, and 2) in other national committees (outside Barbados) their influence might not have been explicitly known. The Healthy Caribbean Coalition’s legitimacy was questioned not by industry but by other health advocates and the technical officers who facilitated the standards process at different levels, indicating some level of dissonance and fragmentation in the health advocacy side.

In contrast, some organizations have inherent legitimacy in the process. The Codex Alimentarius and relatedly, the WTO or the TBT agreement, were all inferred regularly and framed as inherently legitimate.

“So, when I got to the meeting, and then to learn that it was a matter of a Chilean input, in my mind, I would be saying: “Well, I am accustomed to something coming from Codex, how is it now that I’m hearing about a Chile input?” (Participant 20, neutral participant, 08/21/19)

In the example above, a neutral participant based in Barbados explained that their familiarity providing technical expertise on Codex standards left them uncertain regarding the relevance of a “Chilean” model. These types of comments were common and highlight the association of Codex within the (food) standards process. No respondent in this study questioned the legitimacy of Codex to influence the proceedings, unlike the legitimacy of other bodies such as the Healthy Caribbean Coalition and PAHO. While this is unsurprising, given the central role Codex plays within the international (food) standards regime, it is worth noting again here that FOPL in the Caribbean did not begin as a standard—it began as a public health policy. So, while the respondents interviewed as part of the national and regional standards processes questioned some actors’ interests, motivations and influence, Codex (and other trade-related actors) were exempt from questions of legitimacy.

Community membership and familiarity with process then are relevant conditions as to how participants interpreted and perceived legitimacy of actors. While familiarity induces immediate acceptance and deferral to the authority of Codex, these participants viewed PAHO as an outsider influence without legitimacy. There are both conceptual and instrumental reasons for this: PAHO is not normally a standard-setter and sits outside the standards regime paradigm; and, by framing PAHO as an illegitimate actor and Codex as a legitimate actor, FOPL can be shifted continually further away from a health narrative and further into a venue dominated by authorities relevant and supportive of trade.

Actors also had different reactions to these accusations of legitimacy or illegitimacy. While PAHO was instrumental in the initial stages of getting FOPL on the table, they largely stepped out of facilitating its’ progress once it was delegated into the standard setting process. This caused some frustration for health advocates, who see them as an institutional force with great influential power within the region. But PAHO’s ability to exert influence regionally could be interpreted as crossing jurisdictional boundaries at the national level. PAHO was very careful in attending (only infrequent) meetings as technical experts to present evidence in a neutral and technocratic way, rather than as policy champions. In an even more extreme case, PAHO attended the National Consultation in Barbados, led by the Ministry of Health and BNSI, and yet did not present in this venue, even when asked. While this study was limited by not speaking with a PAHO representative directly, PAHO acted with extremely sensitivity to arguments of sovereignty and intentionally avoided taking a stronger public stance for this reason (Participant 32, 07/16/19). Yet PAHO represented expert authority for many, lending credibility to FOPL as a public health policy, rather than a standard:

“PAHO is the health institution for the region and they’re mandated by their member states to provide advice and recommendations on the best policies for health, you know, and labeling is one of their recommended best interventions...” Participant 23, Health Organization, (05/11/2019)

Losing PAHO’s participation then also helps to erase these roots as a public health policy. The Healthy Caribbean Coalition and other health advocates interpreted the mandate of PAHO as one which is supportive of the region’s health; where health is an important and reasonable priority; and that PAHO is a legitimate standard-setter with expert authority. Health advocates in the region not only saw PAHO as a legitimate actor in the standards process, but also saw a right for PAHO to be a policy champion during the process. The same advocates that were frustrated and disappointed by public silence on the issue from PAHO, were frustrated because they felt PAHO should be a (or the) leader on the issue. Instead of carrying the institutional weight associated with PAHO, individual health advocates, NGOs and health ministries were left countering narratives and arguments put forward by industry, leaving the health advocacy side of the process fragmented and unprepared.

The characterization of PAHO as an illegitimate standard-setter, among those familiar with the standards process, was both unsurprising and informative. The discursive power to frame who is or who is not authoritative within the process, remains with those who are familiar with the process and understand the rules of the game. As such, it allows industry players and familiar government department representatives to defer to authorities that support their desired outcome. Participants versed in these rules dictated the interpretation of the rules, reinforcing standards set by Codex as the only legitimate standards. Characterizing PAHO through lack of official role in the process or through jurisdictional claims of territoriality both contributed to the same outcome: a lack of legitimacy for a major international organization, and the resulting inability to exert influence, provide expertise, or champion FOPL in the process.

The claim of being an illegitimate standard-setter also helped shift FOPL out of the control of public health advocates like PAHO and health ministries. If PAHO is illegitimate actor, then national health ministries barely fare better—they might have appropriate national jurisdiction, but they still have no place in standard-setting architecture. Public actors are generally seen as legitimate in prescribing societal behaviour, as public health actors do, in liberal democratic theories because of their accountability to the public (Cutler, p.33, in Hall and Biersteker, 2002). The displacement of public health actor legitimacy, raises a question of whether the state—or, in this case, the regional governance architecture—is complicit in a delegated authority for public (health) to private authority (Hall & Biersteker, 2002). If PAHO has no legitimate role in the process, and Codex has unwavering authority, an unconscious reckoning between rules motivated to improve public health motivated and rules motivated to appease private industry has taken place. Indeed, Clapp argued in 1998 (p.312) that states adopt international standards partly because of the fit with a “prevailing liberal ideology” and “reduced regulatory role for the state.”

These frames—the Chilean trade advantage, the “inevitable” TBT challenge, and framing some health actors as illegitimate—were persuasive to both industry and non-industry stakeholders. By arguing that FOPL is a transgression of the rules-based trading regime, industry stakeholders used the authority associated with WTO rules to set a foundation where FOPL is a trade conflict and helped to erase public health goals entirely from the discussion by making PAHO an improper influence. Similarly, industry opponents of FOPL falsely argued that Chile would gain an unfair trade advantage in the region, using committee members and consumers’ desire for United Kingdom and US products to bolster the trade argument. Food industry actors and other committee members in all three case study countries used the authority derived from the WTO in standard setting by discursively framing FOPL as being in opposition to the rules and authority of the international trade regime.

Emphasizing the consequences of transgressions of trade rules also then reinforces WTO authority, making trade regime conflicts more important than public health concerns. The result has been an eroded public health authority over FOPL and reinforced private sector authority over it. In summary then, food industry actors have used and reinforced authority from the international trade regime to exert discursive power strategies, reframing FOPL towards a trade conflict narrative. This trade-oriented narrative emphasized that FOPL is subject to the international trading regime, and in doing so, made the original purpose of FOPL invisible to committee members.

Discussion: Framing, Discursive Power and Authority

Taken together, the framing strategies employed by the food industry in the regional FOPL standard-setting process contribute to a frameshift from regional public health policy to trade regime conflict. The successful reframe, and the ensuing commitment by the Government of Jamaica to reject adoption of FOPL, raises two more questions for consideration. First, let us consider why the food industry was so much more capable than health advocates in promoting their vision of reality.

Given that FOPL was proposed by the CARICOM Public Health Agency and adoption was encouraged by public health advocates and experts, it somewhat surprising that the shift into the development and adoption phase of the policy cycle—standard setting, in this case—produced such a monumental shift in power and authority over the policy. Key to this distinction is the fact that upon entry into the standard setting regime, FOPL lost its identity as a public policy measure. While public health experts and advocates followed FOPL into standard setting, the existing participants on food labelling standards committees had no prior knowledge around FOPL as a public health solution. The result was two incoherent communities attempting to make governance decisions on food systems: “health advocates” with no familiarity in standard setting, and everyone else, who had long been involved in standards and therefore had much more experience and familiarity in the standard-setting regime.

In assessing whether global governance is legitimate or not, Bernstein (2011) argued that legitimacy is the result of two or more communities interacting and accepting the authority of an institution. The institution should have broader legitimating norms and discourses (what Bernstein describes as social structures) that are prevalent in the given issue area. In describing political legitimacy in global governance, Bernstein highlights the importance of coherence amongst those communities. Because legitimacy is contingent on shared acceptance of rules, “[t]he coherence or incoherence of that community matters, since incoherence or strong normative contestation among groups within a legitimating community make establishing clear requirements for legitimacy difficult” (Bernstein, 2011, p.21). In this case, the amalgamation of two communities—health and standard-setting participants—have made it impossible for either side to perceive the policy process as legitimate. The communities have contradicting beliefs around the authority of specific institutions, with health advocates ascribing authority to PAHO and standard-setting participants ascribing authority to the WTO and trade regime rules and norms.

While the competing communities value different authorities, these valuations also tell us something about how authority is sourced and attributed. FOPL originated in the public health policy sphere, where public health advocates and researchers had expert authority. Sources of knowledge in this sphere are agreed on, as in any epistemic community, which Haas defines as “a network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area” (Haas, 1992, p.3). Inside this coherent community, public health advocates and researchers were viewed as experts on FOPL and considered to have an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge, but once shifted into standard-setting the incoherence of community and lack of authority of public health actors was evident.

Forum shopping, or venue shifting, is often used by those searching for a friendly audience to their cause (Keck and Sikkink, 1998). In this case though FOPL was shifted into a less friendly venue, with a less coherent community. In standard setting, there is also a foundation of coherent community members. Standard-setting participants view the WTO and its offshoots as the authority institutions, with trade rules and norms as the operating rules and norms of standard setting as a process. Those who have knowledge and familiarity of these rules and norms become experts of process. In the same way that public health experts had an authoritative claim over FOPL, food industry actors had an authoritative claim over the knowledge of standards and standard setting. This version of expert authority equated to knowledge on process that health actors lacked once FOPL shifted into standard setting. Food industry actors had authority inside standard setting, based on process knowledge that formed the source of discursive power. Knowing the rules and norms of standard setting meant that food industry actors could frame FOPL inside this venue as being 1) inconsistent with international trade rules, both in transgressing specific rules (providing an advantage to Chile and a TBT); and 2) inconsistent with international trade norms, by not accepting PAHO and other health actors as legitimate authorities.

Taken together this answers the first question: Why was the food industry so much more capable than health advocates in promoting their vision of reality? The food industry was more capable because this stage of the policy development cycle took place in a venue where industry members possessed more discursive power and shaped committee outcomes accordingly. That is, industry actors had the power to reframe the conversation because they understood the rules and norms of the venue FOPL had been shifted into. Similarly, Kooiman (2002) has pointed to the way that business power influences policies by designating problems to specific categories through specific norms and values.

A subsequent question then is why and how a venue where discursive power and expert authority of businesses was equal or more than that of health advocates was chosen for this stage of the policy development cycle. When this question was put to them, health advocates, policymakers and standard-setting technical officers all agreed this was the only way to achieve uniform FOPL policy across the region. Actors argued that the nature of CARICOM’s regionalization efforts meant that there is no supranational health infrastructure to impose regional policy. While economic and trade-facilitating architecture had been developed from early in CARICOM’s history (Alleyne, 2008a), the structure of CARICOM as a community of sovereign independent states (Grenade, 2008) means must be a high degree of motivation amongst national players for cooperation and coordination in different topic areas to be achieved (Alleyne, 2008a). Whereas economic and trade-oriented cooperation and coordination have been the foundation of CARICOM’s integration and forms the first of its “Pillars,” health instead fell under the catch-all pillar of “functional cooperation,” where all other issues are coordinated (Alleyne, 2008a; 2008b). The pragmatic response then, amongst participants, was that FOPL was shifted into standard setting for the simple reason that it was the only option for a regionally uniform label to be implemented.

The pragmatic decision obfuscates the wider underlying structural power of the food industry to shape the food environment. This study has pointed to the framing that demonstrates corporations’ discursive power to shape the perception of a policy problem and solution, ultimately reframing FOPL as a problem of trade rules rather than a public health policy solution. If the source of this discursive power lies in the chosen venue though, and a venue does not exist to carry on the work of public health policy in the region, the pragmatic answer to our second question is not sufficient. In concluding her 1998 article on the implications of ISO 14000 for environmental management ceilings, Clapp foresaw the underlying structural power of businesses in global environmental governance. National governments were embracing international standards because they fit the “prevailing liberal ideology held by most states, which calls for a reduced regulatory role for the state” and standards fit nicely into the “era of global free trade” (p.312). The fact that regional standard setting was the only venue to produce regional health and food systems policy should tell us what is prioritized in regional governance: trade over health. In other words, in this case we see that institutional arrangements and discursive power are complementary to corporate power over food systems policy.

Conclusion

FOPL has ultimately failed to be adopted in CARICOM. Jamaica’s recent decision to reject FOPL and the regional standard’s continued delay in being approved indicate that the framing of a trade conflict has indeed been a successful one. While non-communicable diseases continue to be a major killer in the Caribbean, health has not been prioritized over trade interests, both in the larger governance structure of CARICOM and in the dynamics of this particular case. While seen as a pragmatic decision given the governance structure of CARICOM, the shift of FOPL into regional standard setting opened the policy up to be reframed as a trade issue rather than a health solution. We can see this as a shift into a “public-private regime” (Clapp, 1998) or even private authority, where private sector interests hold the balance of power.

The consequence of discursive power in regional standard setting was a complete reframe of the food systems and public health policy that began the process. But even this analysis of framing can obfuscate an underlying problem: the prevailing liberal ideology that undergirds decision making about food systems. This study has illuminated the pathways of specific discursive power of the food industry inside the standard setting regime in CARICOM, but it also points to the prioritization of trade and economic regional infrastructure as a source of this power over food systems policymaking. Rather than a pragmatic answer to a governance question, FOPL’s shift into standard setting shows the underlying priorities of the governance system in question. Moving a policy that is based on curbing the sales of ultra-processed food, into a venue dominated by the power and authority of those who create, sell or distribute ultra-processed foods, has proved to be an exercise of futility. The adoption of a universal, warning-label style FOPL in CARICOM has, at this point, failed and this failure demonstrates the institutional and discursive power of the food industry to maintain the status quo.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of Confidentiality Agreements. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bGJoaW50b25AdXdhdGVybG9vLmNh

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Waterloo, University of the West Indies (Mona and Cave Hill Campuses), Chief Medical Officer St Kitts and Nevis, IDRC Advisory Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by the International Development Research Centre and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The author gratefully acknowledges the intellectual support from the Food, Environment and Health team and the George Alleyne Chronic Disease Research Centre for hospitality and office space.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.796425/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1See Samuels et al., 2014 for tracking member-state commitments as a way to hold governments accountable for action on NCDs.

2This line of reasoning is a false representation. Food labels the case study states must be in English (this differs in other language-speaking countries in the Caribbean but remains true for this study). This has been a popular concern in recent years in Caribbean media with the increasing number of Asian grocery stores and increasing presence of pre-packaged food with non-English language labels. The result is that Chilean labels would still need to undergo costly changes, since they are currently manufactured in Spanish, negating at least part of the first mover advantage.

3For an overview of different FOPL schemes and their strengths and weaknesses, see Kanter et al., 2018.

4See Boza et al., 2019 for a detailed examination of the discussion resulting from claims made against Chile’s FOPL at the TBT Committee. Boza and colleagues expertly explain the concerns of other states against FOPL by categorizing them as: “(i) the necessity and restrictiveness of the measure, (ii) the compliance with the principles of: harmonization, non-discrimination and transparency, and (iii) the implementation of the legislation” (p.83). The study describes the ensuing discussion and results, and applies other similar cases as examples.

5Chile and Uruguay’s FOPL have so far gone unchallenged. See Boza et al., 2019 for an excellent review of the concerns raised and discussed at the TBT Committee related to Chile’s Food Law.

6In fact, on behalf of the tobacco companies.

7Codex Alimentarius, the global body responsible for setting food safety and labelling standards, is in fact jointly facilitated by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). PAHO is the regional office of the WHO–suggesting an obfuscation, at best, of the legitimate role of PAHO.

8PAHO seems to be sensitive to these claims. While a partner in the initial policy transfer project and a funder in earlier parts of the process, PAHO has been quiet in terms of advocacy on this issue. Participants reported that PAHO was absent from the national meetings.

References

Cutler, A. C., Haufler, V., and Porter, T. (Editors) (1999). Private Authority and International Affairs. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Alleyne, G. (2008a). “Functional Cooperation in CARICOM: Philisophical Perspective, Conceptual Issues and Relevant Examples,” in The Caribbean Community in Transition. Editors K. Hall, and M. Chuck-A-Sang (Kingston; Miami: Ian Randle Publishers), 11–26.

Alleyne, G. (2008b). “The Silent Challenge of the Chronic Non Communicable Diseases (NCDs) in the Caribbean,” in The Caribbean Community in Transition. Editors K. Hall, and M. Chuck-A-Sang (Kingston; Miami: Ian Randle Publishers), 283–299.

Bachrach, P., and Baratz, M. S. (1963). Decisions and Nondecisions: An Analytical Framework. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 57 (3), 632–642. doi:10.2307/1952568

Baum, F. E., Sanders, D. M., Fisher, M., Anaf, J., Freudenberg, N., Friel, S., et al. (2016). Assessing the Health Impact of Transnational Corporations: Its Importance and a Framework. Glob. Health 12 (1). doi:10.1186/s12992-016-0164-x

Baumgartner, F. R., Breunig, C., and Grossman, E. (2019). Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. Oxford University Press.

Bernstein, S. (2011). Legitimacy in Intergovernmental and Non-state Global Governance. Rev. Int. Polit. Economy 18 (1), 17–51. JSTOR. doi:10.1080/09692290903173087

Boza Martínez, S., Polanco Lazo, R., and Espinoza, M. (2019). Nutritional Regulation and International Trade in APEC Economies: The New Chilean Food Labeling Law. SSRN J. 14, 73–113. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3362184

Büthe, T., and Mattli, W. (2011). The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

CARPHA (2017). Promoting Healthy Diets, Food Security, and Sustainable Development in the Caribbean through Joint Policy Action (Technical Brief High Level Meeting to Develop a Roadmap on Multi-Sectoral Action in Countries to Prevent Childhood Obesity through Improved Food and Nutrition Security). Barbados: CARICOM Technical Brief. Available From: https://carpha.org/Portals/0/Documents/CARPHA_6_Point_Policy_for_Healthier_Food_Environments.pdf.

Cashore, B. (2002). Legitimacy and the Privatization of Environmental Governance: How Non-state Market-Driven (NSMD) Governance Systems Gain Rule-Making Authority. Governance 15 (4), 503–529. doi:10.1111/1468-0491.00199

Chung, A. (2021). Front-of-packaging Labelling – Jamaican Consumers Trumped by Vested Interests. The Jamaican Gleaner. Available From: https://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/focus/20210815/andrene-chung-front-packaging-labelling-jamaican-consumers-trumped-vested.

Clapp, J. (2009). “Corporate Interests in US Food Aid Policy,” in Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance. Editors J. Clapp, and D. A. Fuchs (MIT Press), 125–152.

Clapp, J., and Fuchs, D. (2009). “Agrifood Corporations, Global Governance, and Sustainability: A Framework for Analysis,” in Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance. Editors J. Clapp, and D. A. Fuchs (MIT Press), 1–25. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262012751.003.0001

Clapp, J. (1998). The Privatization of Global Environmental Governance: ISO 14000 and the Developing World. Glob. Governance 4 (3), 295–316. doi:10.1163/19426720-00403004

Corvalán, C., Correa, T., Reyes, M., and Paraje, G. (2021). Impacto de la Ley chilena de etiquetado en el sector productivo alimentario. Santiago de Chile: FAO and INTA. doi:10.4060/cb3298es

Falkner, R. (2008). Business Power and Conflict in International Environmental Politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Falkner, R. (2009). “The Troubled Birth of the “Biotech Century”: Global Corporate Power and its Limits,” in Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance. Editors J. Clapp, and D. A. Fuchs (MIT Press), 225–252.

Foster, N. (2021). Front of Pack Warning Labels – the Human Rights and Trade Dimension. Jamaica Standards Network Presentation on Front-of-Pack Warning Labelling Standards, Faculty of Law, UWI Cave Hill.

Friel, S. (2020). Redressing the Corporate Cultivation of Consumption: Releasing the Weapons of the Structurally Weak. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag 10, 784–792. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2020.205

Fuchs, D. (2005). Commanding Heights? the Strength and Fragility of Business Power in Global Politics. Millennium 33 (3), 771–801. doi:10.1177/03058298050330030501

Fuchs, D., and Kalfagianni, A. (2009). Discursive Power as a Source of Legitimation in Food Retail Governance. Int. Rev. Retail, Distribution Consumer Res. 19 (5), 553–570. doi:10.1080/09593960903445434

Görg, C., and Brand, U. (2006). Contested Regimes in the International Political Economy: Global Regulation of Genetic Resources and the Internationalization of the State. Global Environ. Polit. 6 (4), 101–123. doi:10.1162/glep.2006.6.4.101

Green, J. F. (2013). Rethinking Private Authority: Agents and Entrepreneurs in Global Environmental Governance. Princeton University Press.

Grenade, W. (2008). “Sovereignty, Democracy and Going Regional—Navigating Tensions: The Caribbean Community and the European Union Considered,” in The Caribbean Community in Transition. Editors K. Hall, and M. Chuck-A-Sang (Kingston; Miami: Ian Randle Publishers), 114–135.

Haas, P. M. (1992). Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination. Int. Org. 46 (1), 1–35. doi:10.1017/s0020818300001442

Henson, S., and Humphrey, J. (2009). The Impacts of Private Food Safety Standards on the Food Chain and on Public Standard-Setting Processes. Codex Alimentarius Commission, 59.

IDRC (2018). Evaluating CARICOM’s Political Commitments for Non-communicable Disease Prevention and Control. Ottawa, Canada: IDRC - International Development Research Centre. Available From: https://www.idrc.ca/en/project/evaluating-caricoms-political-commitments-non-communicable-disease-prevention-and-control.

Kanter, R., Vanderlee, L., and Vandevijvere, S. (2018). Front-of-package Nutrition Labelling Policy: Global Progress and Future Directions. Public Health Nutr. 21 (8), 1399–1408. doi:10.1017/S1368980018000010

Keck, M. E., and Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Available From: http://www.oapen.org/download?type=document&docid=642697.

Koivusalo, M., Schrecker, T., and Labonté, R. (2009). “Globalization and Policy Space for Health and Social Determinants of Health,” in Globalization and Health: Pathways, Evidence and Policy. Editors R. Labonté, T. Schrecker, C. Packer, and V. Runnels (Routledge), 105–130.

Kooiman, J. (2002). “Governance: A Social-Political Perspective,” in Participatory Governance. Editors J. R. Grote, and B. Gbikpi (VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 71–98. doi:10.1007/978-3-663-11003-3

Labonté, R. (2019). Trade, Investment and Public Health: Compiling the Evidence, Assembling the Arguments. Globalizat. Health 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s12992-018-0425-y

Milsom, P., Smith, R., and Walls, H. (2020). Expanding Public Health Policy Analysis for Transformative Change: The Importance of Power and Ideas Comment on "What Generates Attention to Health in Trade Policy-Making? Lessons from Success in Tobacco Control and Access to Medicines: A Qualitative Study of Australia and the (Comprehensive and Progressive) Trans-Pacific Partnership". Int. J. Health Pol. Manag 1. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2020.200

Moon, S. (2019). Power in Global Governance: An Expanded Typology from Global Health. Glob. Health 15 (S1), 74. doi:10.1186/s12992-019-0515-5

Murphy, C. N. (2015). Voluntary Standard Setting: Drivers and Consequences. Ethics Int. Aff. 29 (4), 443–454. doi:10.1017/S0892679415000398

Newell, P., and Glover, D. (2003). Business and Biotechnology: Regulation and the Politics of Influence. Institute of Development Studies.