94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Coat. Dyes Interface Eng., 06 February 2025

Sec. Engineered Surfaces and Interfaces

Volume 3 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/frcdi.2025.1539792

This article is part of the Research TopicFrontiers in Coatings, Dyes and Interface Engineering: Inaugural CollectionView all 10 articles

Failure in the adhesion between hydroxyapatite and the metallic substrate in commercial biomaterials is one of the significant drawbacks in implantology. The demand for confident analytical methods to characterize these coatings is met through a rigorous research process. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was chosen as the method to characterize hydroxyapatites. A meticulous data analysis from FTIR spectra was conducted, and an FTIR library was constructed from FTIR spectra of different types of hydroxyapatites, considering several chemical environments. The analytical procedure involved the registry of the spectra, localization of the leading absorption bands from the minima of the second derivative spectra, and reconstitution of the original spectra by curve deconvolution. The FTIR library was employed to analyze commercial surgical screws that failed in their use in different implants. Our methodology identified the structural reasons for such failure, caused by the selective removal of non-apatitic environments during adsorption onto the metallic implant. The method identifies the adhesion degree of the apatite coating on the implant before implantation in a biological organism, thereby preventing additional patient interventions and the associated costs.

The development of bone implants evolved into devices that promote the natural growth of the tissue. Research has focused on developing implants with specific morphology and physicochemical characteristics that foster an effective interaction between the tissue and the implant, as most implant-related complications arise at the implant-bone interface. To reach this goal, researchers have coated metals with hydroxyapatite (HA), the biological mineral found in natural bones. However, in many cases, there are issues with the adhesion of the synthetic HA to the metal, leading to coating failures (Shibli and Jayalekshmi, 2008; Ahmed et al., 2011; Beig et al., 2020).

Different methods have been optimized to improve adhesion to metal surfaces (Jaafar et al., 2022; Dudek et al., 2024), varying the substrates (Marchenko et al., 2023), the operating parameters and including pre/post treatment to enhance the bonding strength (Safavi et al., 2021). One variable that enhances adhesion is the deposition of nanostructured HA, which increases adhesion strength by 2–3 times and boosts corrosion resistance by 50–100 times compared to conventional HA coating (Mohseni et al., 2014). Moreover, nano-level modifications promote osseointegration and reduce bacterial adhesion.

Biological apatite, a mineral found in natural bones, exhibits a nanocrystalline structure aligned with the collagen fibers. This apatite is called an impure form of HA because it may contain a substitution of cations such as Na, K, Mg, or other elemental ions in the cation sublattice, Moreover, the anion sublattice includes carbonates, fluorides, and other ions that do not exceed 5% (Antoniac, 2019). Synthesized nanocrystalline apatite materials are considered biomimetic materials due to their formation under low-temperature conditions, physiological pH, and physicomechanical characteristics (non-stoichiometric, crystal size, presence of non-apatite species, hardness, and elastic modulus). Nanoscale topography determines the interfacial phenomena of the coatings related to better adhesion. It has also been seen that specific ions in the hydrated layer of the bones allow for better interaction with the implant (Kligman et al., 2021). However, analytical methods are currently lacking in identifying these ions’ chemical environment.

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), along with Raman spectroscopy, are the most commonly applied techniques to get information about phosphate, carbonate (Fleet, 2009), hydroxyl groups, and water molecules of hydration (Cazalbou et al., 2004; Panda et al., 2003; Lebon et al., 2008; Xian, 2009). The FTIR study of the hydroxyapatite allowed determining the existence of apatitic and non-apatitic environments on the crystal (Cazalbou et al., 2004; Cazalbou et al., 2005; Rey et al., 2009). The non-apatite environments in the bone are formed by labile high-mobility ions belonging to the hydrated layer, such as calcium and phosphate acid (HPO42-). However, the carbonate from the apatite regions has less mobility because they are not found in the outer layer of the material (Cazalbou et al., 2004). The hydrated layer can accept and incorporate trace ions such as Sr(II), Mg(II), Pb(II), and Al(III) before rereleasing to the environment (Cazalbou et al., 2005). They can even adsorb and release proteins and exchange groups of charged proteins by ions, such as albumin, growth factors, etc. (Cazalbou et al., 2004). The apatite regions have a process of exclusion of water molecules and a loss of HPO42− ions during maturation. Moreover, the concentration of Ca(II), OH−, and CO32- ions increases (Eichert et al., 2002), and the HPO42− is replaced by the CO32− (Eichert et al., 2009) given a more stable and higher degree of order, transforming into stoichiometric crystals.

Nanocrystalline and biological apatites show HPO42− ions specific bands. Still, additional bands that are not presented in crystalline apatites are identified. The non-apatitic phosphate environments relate to synthesized nanocrystalline apatites at physiologic pH and exchangeable ions on the surface. Pure environments of type A and type B carbonate ions present specific FTIR bands (Peeters et al., 1997). However, as in the case of phosphate groups, there are additional vibration bands in biological apatites and nanocrystalline apatites synthesized at physiological pH, corresponding to non-apatitic carbonate ions environments (Rey et al., 2009; Penel et al., 1998). A characteristic band shown in the ν2CO3 IR domain can be used for determining non-apatitic carbonate environments.

Miller and Wilkins first reported the phosphate group spectral bands in 1952 (Miller and Wilkins, 1952). Despite many studies identifying and discriminating mostly crystalline apatite bands, allocating non-stoichiometric apatite substituents must be more accurate. The distortion of ionic environments induces a widening of the band, limiting the resolution and partly altering the correlations of vibration related to the theory of factor groups (Cazalbou et al., 2004).

The graphical deconvolution of FTIR spectra is a powerful technique that we have employed to identify apatite and non-apatite regions in synthesized hydroxyapatite coating. This method allows us to predict the degree of adhesion of the coating before implanting the biomaterial, a crucial step in our research. FTIR is particularly useful in distinguishing regions associated with non-apatite domains, aiding in interfacial recognition. The second derivative is a key tool in this process, helping us to identify overlapping absorption bands belonging to phosphate groups. Once these bands are identified, spectral deconvolution can be performed, allowing us to distinguish the signals corresponding to the apatite regions of PO43− groups and non-apatite groups in the regions HPO42- (Eichert et al., 2009).

Due to the overlapping bands in the apatite and non-apatite regions, we propose performing the spectrum deconvolution and analyzing the second derivative of the absorption spectra to identify the hidden bands. The present work allowed us to identify FTIR vibrational bands assigned to phosphate groups between 400–700 cm−1 and 800–1,100 cm−1. We also identified the carbonate band assigned to type A and B environments.

All reagents used were analytic grades, and the solutions were prepared with milli-Rho water. The Hydroxyapatites synthesis used: calcium hydroxide, (Ca(OH)2, E. Merck); phosphoric acid (H3PO4); urea ((NH2)2CO, 99.3%, SIGMA); calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Ca(NO3)2.4H2O, 99%, Mallinckrodt); diammonium hydrogen phosphate ((NH4)2HPO4, 99.5%, Mallinckrodt); sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 97%, Reagent SA, Laboratorios Cicarelli); sodium fluoride (NaF, 99.2%, J.T. Baker); strontium nitrate anhydrous (Sr(NO3)2, 99.0%, SIGMA); calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Ca(NO3)2.4H2O, 99%, Mallinckrodt); diammonium hydrogen phosphate ((NH4)2HPO4, 99.5%, Mallinckrodt); sodium fluoride (NaF, 99.2%, J.T. Baker).

Two samples of biological apatites were obtained. One of them consisted of a bone calcification of the shoulder tendon and was obtained by open surgery (performed at CASMU Hospital in Uruguay and with the patient’s consent). The second sample was a dental piece obtained by a dental professional from an unknown patient.

X-ray diffraction Spectroscopy (XRD) was carried out using a Philips PW3710 diffractometer CuK radiation. All the hydroxyapatites were finely ground in an agate mortar. The FTIR spectra were obtained using an IR Prestige-21 Shimadzu (Japan). The sample mixture was pressed using a Pike Crush IRTM Technologies at 10 tons.

Nanostructured hydroxyapatite was synthesized according to Kumar et al. (2004). An aqueous solution was prepared using 0.2 M calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2, E. Merck) in 250 mL of 0.12 M phosphoric acid (H3PO4), stirring for 2 h at 52°C and pH 5. The suspension was kept at room temperature for approximately 15 h and centrifuged at 40,000 rpm for 15 min. The resulting precipitate was rinsed with milli-Rho water and dried in the oven overnight at 62°C.

Type B carboxyapatite was synthesized according to Wu et al. (2009). A 50 mL solution of urea ((NH2)2CO, 99.3%, SIGMA) 2 M and heated at 80°C for 22 h was added to 50 mL of 0.5 M Ca(NO3)2 solution drop by drop. After that, 50 mL of 0.3 M (NH4)2HPO4 solution was added slowly to the previous solution using a buret. The mixture was made, stirring constantly at 80°C, and the final pH was 5. The final solution rested for 12 h. Then, it was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 min, and the precipitate was rinsed with water. This procedure was repeated four times. The precipitate was dried in the oven at 60°C for 24 h.

The synthesis followed that reported by Manjubala et al. (2001). A calcium nitrate tetrahydrate 1 M Ca(NO3)2 solution was prepared with 5 mol% NaF. The pH was adjusted to 9 with 2 M NaOH. To 50 mL of the resultant solution, 50 mL of 0.6 M H3PO4 was added at room temperature at constant stirring (2 mL per minute). The pH was adjusted to 9 with 2 M NaOH. The resultant solution was rested for 24 h at 80°C. Finally, the solution was centrifuged at 5000 rpm (4 times) for 15 min, and the precipitate was rinsed with milli-Rho water and dried at 90°C for 48 h.

Strontium apatite was synthesized according to Li et al. (2007). A 0.2 M Ca(NO3)2 solution with 1.5% Ca/Sr molar ratio with Sr(NO3)2 was prepared. In parallel, another 0.2 M (NH4)2HPO4 solution was prepared. Both solutions were adjusted at pH 10 with 25% ammonium solution. The (NH4)2HPO4 solution was added to Ca(NO3)2 solution in a constant stirring (1.36 mL/min) at 50°C for 5 h. The final solution was rested for 48 h at room temperature. The solution was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min, and the precipitate was rinsed three times with milli-Rho water and the last with absolute ethanol. Then, it was dried at 120°C in the oven for 12 h.

Following the synthesis of the four species of hydroxyapatites, about ¼ of each powder was finely ground in an agate mortar and mixed with ¾ of KBr for infrared analysis. The resulting mixture was pressed at 10 tons for 5 min t o form a pellet 1 cm in diameter and 0.5 mm in thickness. The FTIR spectra covered the region 1, ν4 phosphate domain (400–700 cm-1), and region 2, ν1 and ν3 domain of phosphate (800–1,400 cm-1). The ASCII data was then analyzed using Origin® software. The spectra were first normalized between 0 and 1, and the second derivative was calculated in the spectral range between 400 and 700 cm−1 (region 1) and between 800 and 1,300 cm−1 (region 2). Finally, the Levemberg - Marquand algorithm was used to identify the hidden spectral bands. The results were used to construct the spectral library.

A Colombian medical materials company’s commercial titanium (Ti, 99%) hydroxyapatite-coated surgical screws were examined. The hydroxyapatites were studied from commercial powder samples and deposits made on the screws given by the company. The screw was coated using an electrophoretic method, widely used to deposit bioceramic coatings in the industry.

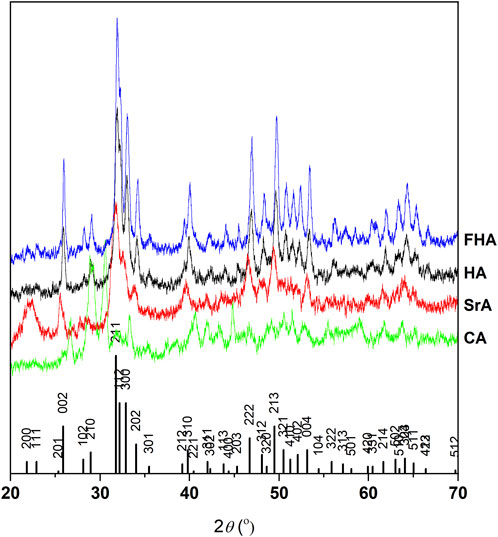

The JCPDSHA spectrum was used as a pattern, and the apatites HA, FHA, and SrA show the same characteristic peaks at 002, 211, 212, 300, 310, 222, 213, 004, and 323 (Figure 1). The spectrum revealed an extra band in SrA at 200 and 111 due to the structural distortion caused by the strontium. This band was also shown by O´Donnell et al. (2008). For CA, several differences can be noted, mainly attributed to the formation of tricalcium phosphate (Durucan and Brown, 2000).

Figure 1. XRD of synthesized hydroxyapatites, compared to the JCPDSHA reference spectrum. Differences in CA are due to the formation of other phosphates, like tricalcium phosphate.

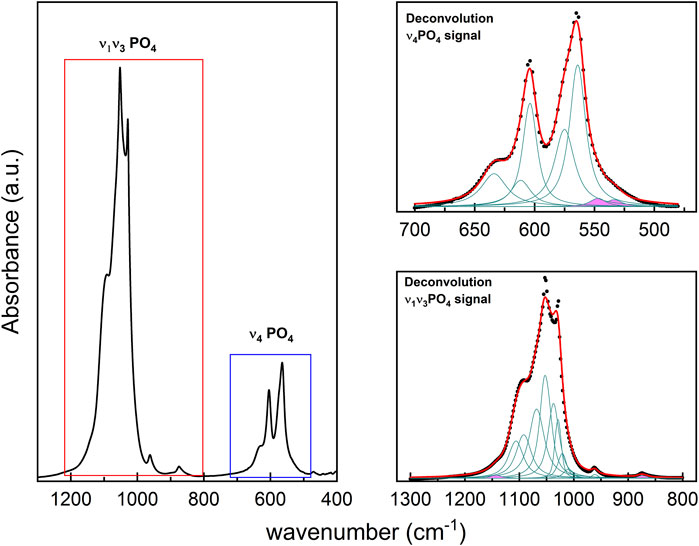

We performed an examination of the spectra bands (400–700 cm−1 and 800–1,300 cm−1 region) to identify vibrational modes corresponding to the non-apatitic environments of phosphate. This involved the second derivative of regions identified in the FTIR spectra. The data obtained from the examination, including the first and second derivative, was then used as the starting point for the deconvolution procedure (Figure 2).

Figure 2. (left panel): FTIR spectrum from synthetic HA with the characteristic's vibrational regions. (upper right panel): HA deconvolution of FTIR spectrum from ν4PO4 region, and (lower right panel): ν1ν3PO4 region. In all cases, the Lorentzian contributions to the absorption bands for the different vibrational modes are identified in green; the contributions' sum curve is indicated in red, which fits the FTIR spectrum (presented in black dots). The bands painted in pink correspond to the vibration modes of HPO42−.

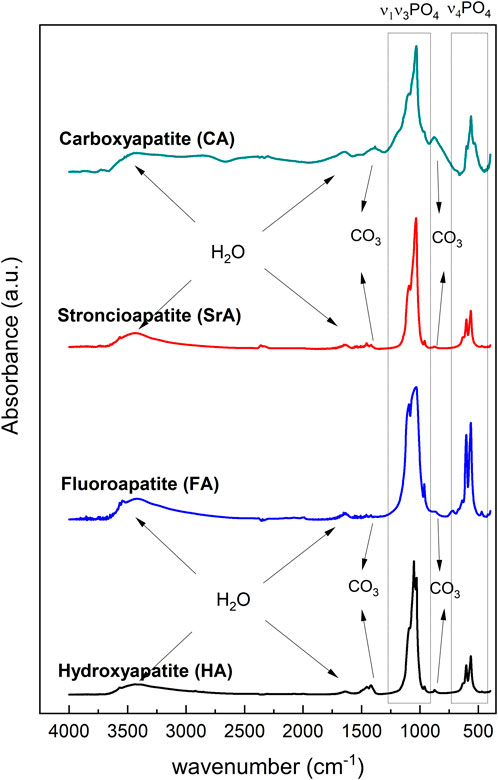

The FTIR spectra of synthesized HA, FHA, SrA, and CA are shown in Figure 3. The spectra show strong absorption bands in two characteristic regions at 450 to 700 cm−1 and 800 to 1,300 cm−1 for HA, FHA, CA, and SrA. The bands at 873 cm−1 and the range between 1,420 cm−1 and 1,457 cm−1 represent the characteristic asymmetric stretching of carbonate group type B (CO32-) in carbonate apatites (Eichert et al., 2009). The bands corresponding to CO32-, both type A and B, and non-apatite were identified in HA, SrA, and FA, indicating carbonate substitution. The peaks were identified at 871 cm−1, 1,429 cm-1, and 1,470 cm−1 for the HA and SrA, and 872 cm−1, 1,420 years 1,457 cm−1 for FHA. The vibration mode of the free hydroxyl bond bending and stretching band was identified at 630 cm-1 and the range 3,565–3,570 cm−1, respectively. The bands at 1,600 cm−1 and the broadband in the 2,500–3,700 cm−1 range correspond to the O–H group stretching vibration of absorbed H2O (Jaafar et al., 2022).

Figure 3. FTIR spectrum of HA, FHA, SrA, and CA with the characteristics PO43− vibrational regions, structural OH− (STLOH), adsorbed H2O, and CO32− vibrational bands.

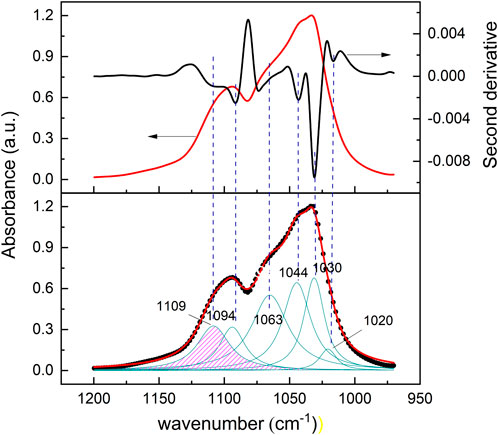

Graphical deconvolution aims to determine the wavenumber of each phosphate band for each region by deconvoluting each curve into n components. This process involves fitting a series of Lorentzian functions using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. The number of bands and the positions of the maximum peaks were identified from the second derivative of each spectral region, resulting in the graphical representation of both the Lorentzian curves of each component and the summed curve of all components (Figure 4).

Figure 4. (upper panel): Second-derivative spectra (black line) calculated from the original spectra (red line). (lower panel): superposed absorption bands are located from the minimum peak position in the derivative spectrum. The region in pink corresponds to HPO42− vibrational absorption modes.

The deconvolution spectra analysis also allowed us to identify hidden bands in the synthesized apatites (Figure 4). The analysis identified that the vibrational modes for the PO43- group are ν1 (960–964 cm−1), ν2 (460–474 cm−1), ν3 (994–1,104 cm−1), and ν4 (562–604 cm−1) located at the fingerprint region of the spectrum. For example, synthesized HA spectral absorbance showed absorption bands in the range of 1,020 cm−1 and 1,094 cm−1 corresponding to PO43- groups and an additional band at 1,109 cm-1 was identified as having HPO42- vibrational modes. FHA showed an absorption band at 864 cm−1, identified as HPO42-. CA showed an intense type B CO32- band at 873 cm−1 due to substituting PO43- for CO32- in type B apatite (Eichert et al., 2009).

We constructed a spectral library with the results obtained by the second derivative, to identify the vibrational modes and chemistry environments of apatitic and non-apatitic regions. Table 1 shows the absorption band characteristics of stoichiometric and non-stoichiometric HA. It also includes the bands corresponding to FHA, SrA, and CA. Biological apatites from teeth and bone were also included. We identified apatitic environment bands in stoichiometric and nanocrystalline HA, extra bands corresponding to non-apatitic phosphate environments, and HPO42−.

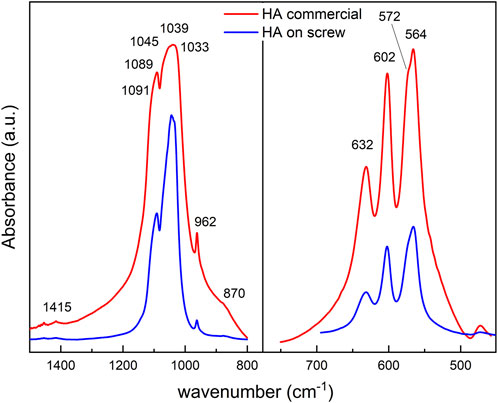

The analysis of commercial HA in powder and deposited on a surgical screw (Figure 5) allows us to identify changes in the chemical environment of the HPO42−, PO43−, and CO32− groups.

The spectrum showed distinct absorption bands that can explain the low adhesion on the surface (Figure 6).

Figure 6. FTIR analysis of HA synthesized (red) and electrophoretic deposited HA on the surgical screw (blue).

The ν4PO4 region between 500–700 cm−1 of commercial HA shows absorption bands at 564 cm−1, 572 cm−1, and 602 cm−1, characteristics of PO43- apatitic environment, and at 632 cm−1 that correspond to structural OH− group. The same bands are identified in HA deposited on the screw spectrum, except for the band at 572 cm−1 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. FTIR spectra of commercial HA (red) and HA deposited on screw (blue). (left panel): Comparative analysis of the ν4PO4 region at 800–1,400 cm−1. (right panel): ν1ν 3PO4 at 500–700 cm−1.

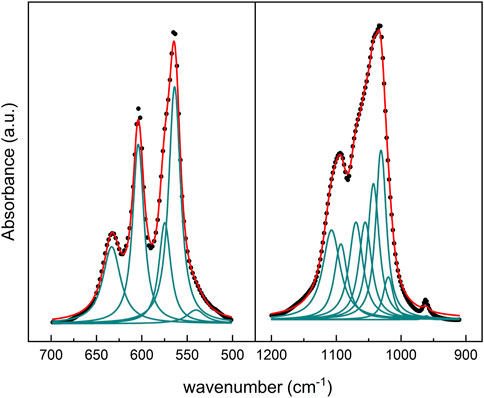

From the deconvoluted graph of the commercial HA in the 500–700 cm−1 range, we identified a band at 533 cm−1 and 551 cm−1 corresponding to the non-apatitic and apatitic regions of HPO42- vibrational group. However, during the deposition, there was a selective loss of non-apatitic regions, and two peaks were observed at 574 cm−1, and 540 cm−1, corresponding to the apatitic environment of ν4PO4 and HPO42-, respectively (Figure 8). In the fingerprint of the non-apatitic phosphate environment in the ν4PO4 domain (Eichert et al., 2009), characteristic bands are not shown in HA on the screw.

Figure 8. Deconvoluted FTIR spectra from HA coating on the surgical screw. (left panel): ν1ν3PO4, and (right panel) ν4PO4 regions.

The deconvolution analysis of the ν1ν3PO4 region between 800 cm−1 and 1,400 cm−1 of commercial HA shows a peak at 962 cm−1 and a complex absorption band that extends between 1,030 and 1,082 cm−1 that includes bands of phosphate groups in apatite environment. In addition, hydroxyapatite deposited on the screw shows an overlapping band between 1,004 and 1,031 cm−1 corresponding to the phosphate apatite environment (Figure 8). Between 1,043 cm−1 and 1,106 cm−1, the bands shown from the deconvolution correspond to the PO43− vibrational band.

Finally, the commercial HA shows a meager absorption band centered at 1,415 cm−1 assigned to the ν3CO3 B and a shoulder at 870 cm−1 corresponding to ν2 CO3 B; both disappeared in the HA on the screw. The ν2CO3 IR domain determines non-apatitic carbonate environments (Eichert et al., 2009). The OH− sharp absorption band at 3,573 cm-1 is observed in commercial HA as well as deposited on the screw.

In the present work, FTIR deconvolutions of the synthesized apatites were performed to identify the allocation of apatite spectrum bands with different chemical environments.

A sample of the commercial HA powder and HA deposited on the screw were analyzed, and the corresponding FTIR bands were assigned using Table 1. Changes in the absorption bands of the HA deposited on the screw were identified compared to the commercial HA, observing a selective loss of the absorption bands corresponding to PO43- groups in non-apatitic environments, ν3CO3 B, and HPO42-. The interaction of the Ti screw with the coating occurs through the hydroxylated oxide of TiO2 (TiO(OH)2) that has an acid-base behavior in an aqueous solution (Pereyra, 2016). This hydroxylated surface can establish interactions with HPO4−2 and Ca(II) ions, allowing stronger adhesion of the HA to the screw (Tengvall and Lundström, 1992). The loss of these environments causes a lower adhesion of the HA; therefore, a coating detachment when in contact with the biological fluids is expected.

We observed that the deposition of HA on the screw causes a rearrangement of the apatite structure, causing a loss of these environments. Non-apatitic environments are associated with nanocrystalline and biological HA (non-stoichiometric) and allow various interactions between the material and ions and molecules in the biological environment (Antoniac, 2019). In particular, ion exchange plays a significant role in surface physiological processes, as well as for maintaining homeostasis and preventing mineral ion toxicity (Cazalbou et al., 2005). Consequently, the loss of these environments in the material reduces its biocompatibility.

This study focuses on a qualitative study of the chemical environments that favor metal-coating interaction using the FTIR technique and, therefore, adhesion. FTIR spectroscopy has proven to be an excellent and straightforward method to analyze the adhesion of biological minerals to metals. Although the commercial HA and the HA deposit on the screw show bands identified as type B carboxyapatite, the deposit corresponds to carboxyapatite with a high degree of stoichiometric components. During the adsorption process, the lost portion of apatite was mainly identified as non-apatitic regions of the synthesized carboxyapatite.

In summary, the HA synthesized while deposited on the screw modified the external region composed of non-apatitic domains, while the apatitic (stoichiometric) structure remained on the screw. This phenomenon helps explain the low adhesion of the HA to the screw and may compromise the future biocompatibility of the implant. One aspect in which the investigation was not deepened was the techniques and conditions (pH, temperature) used during the deposition of HA on the screw. We suggest that future research should focus on analyzing the physicochemical conditions necessary for material deposition, as well as examining its chemical composition following interaction with the metal. In light of the results, it is clear that is crucial for ensuring better biocompatibility of the material.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because A researcher donated his own bone tissue sample after an intervention. We have the consent note. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The human samples used in this study were acquired from gifted from another research group. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. MN: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–original draft. EM: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (ANII) [grant number FCE #220]; PEDECIBA-Química [UN/URU]; MP received and scholarship from ANII (2011).

Ricardo Faccio for XRD analyses, and Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (ANII, Uruguay) and Comisión Sectorial de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC–UdelaR for financial support.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ahmed, R., Faisal, N. H., Paradowska, A. M., Fitzpatrick, M. E., and Khor, K. A. (2011). Neutron diffraction residual strain measurements in nanostructured hydroxyapatite coatings for orthopaedic implants. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 4 (8), 2043–2054. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.07.003

Antoniac, I. (2019). Bioceramics and biocomposites: from research to clinical practice. 1st ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Beig, B., Pishbin, F., Mourino, V., Florencio-Silva, R., Boccaccini, A. R., and Boccaccini, A. R. (2020). Current challenges and innovative developments in hydroxyapatite-based coatings on metallic materials for bone implantation: a review. Coatings 10 (8), 756. doi:10.3390/coatings10121249

Cazalbou, S., Combes, C., Eichert, D., Rey, C., and Glimcher, M. J. (2004). Poorly crystalline apatites: evolution and maturation in vitro and in vivo. J. Bone Mineral Metabolism 22 (4), 310–317. doi:10.1007/s00774-004-0488-0

Cazalbou, S., Eichert, D., Ranz, X., Drouet, C., Combes, C., Harmand, M. F., et al. (2005). Ion exchanges in apatites for biomedical application. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 16 (5), 405–409. doi:10.1007/s10856-005-6979-2

Dudek, K., Strach, A., Wasilkowski, D., Łosiewicz, B., Kubisztal, J., Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz, A., et al. (2024). Comparison of key properties of Ag-TiO2 and hydroxyapatite-Ag-TiO2 coatings on NiTi SMA. J. Funct. Biomaterials 15 (9), 264–275. doi:10.3390/jfb15090264

Durucan, C., and Brown, P. W. (2000). alpha-Tricalcium phosphate hydrolysis to hydroxyapatite at and near physiological temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 11, 365–371. doi:10.1023/a:1008934024440

Eichert, D., Drouet, C., Sfihi, H., Rey, C., and Combes, C. (2009). Nanocrystalline apatite-based biomaterials. New York, USA: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Eichert, D., Sfihi, H., Banu, M., Cazalbou, S., Combes, C., and Rey, C. (2002). “Surface structure of nanocrystalline apatites for bioceramics and coatings,” in 10th International Ceramics Congress and 3rd Forum of New Materials, CIMTEC 2002, Florence, Italy, July, July 7 - 11, 2030, 14–18.

Fleet, M. (2009). Infrared spectra of carbonate apatites: ν2-Region bands. Biomaterials 30 (8), 1473–1481. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.007

Jaafar, A., Schimpf, C., Mandel, M., Hecker, C., Rafaja, D., Krüger, L., et al. (2022). Sol–gel derived hydroxyapatite coating on titanium implants: optimization of sol–gel process and engineering the interface. J. Mater. Res. 37, 2558–2570. doi:10.1557/s43578-022-00550-0

Kligman, S., Ren, Z., Chung, C.-H., Perillo, M. A., Chung, Y.-C., Koo, H., et al. (2021). The impact of dental implant surface modifications on osseointegration and biofilm formation. J. Clin. Med. 10, 1641. doi:10.3390/jcm10081641

Kumar, R., Prakash, K. H., Cheang, P., and Khor, K. A. (2004). Temperature driven morphological changes of chemically precipitated hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Langmuir 20, 5196–5200. doi:10.1021/la049304f

Kunze, J., Muller, L., Macak, J. M., Greil, P., Schmuki, P., and Muller, F. A. (2008). Time-dependent growth of biomimetic apatite on anodic TiO2 nanotubes. Electrochimica Acta 53, 6995–7003. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2008.01.027

Lebon, M., Reiche, I., Frohlich, F., Bahain, J. J., and Falgueres, C. (2008). Characterization of archaeological burnt bones: contribution of a new analytical protocol based on derivative FTIR spectroscopy and curve fitting of the ν1ν3 PO4 domain. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 392 (7-8), 1479–1488. doi:10.1007/s00216-008-2469-y

Li, Z. Y., Lam, W. M., Yang, C., Xu, B., Ni, G., Abbah, S., et al. (2007). Chemical composition, crystal size and lattice structural changes after incorporation of strontium into biomimetic apatite. Biomaterials 28 (7), 1452–1460. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.001

Manjubala, I., Sivakumar, M., and Nikkath, S. N. (2001). Synthesis and characterisation of hydroxy/fluoroapatite solid solution. J. Mater. Sci. 36 (22), 5481–5486. doi:10.1023/a:1012446001528

Marchenko, E. S., Dubovikov, K. M., Baigonakova, G. A., Gordienko, I. I., and Volinsky, A. A. (2023). Surface structure and properties of hydroxyapatite coatings on NiTi substrates. Coatings 13 (4), 722. doi:10.3390/coatings13040722

Mohseni, E., Zalnezhad, E., and Bushroa, A. R. (2014). Comparative investigation on the adhesion of hydroxyapatite coating on Ti-6Al-4V implant: a review paper. Int. J. Adhesion Adhesives 48, 238–257. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2013.09.030

O’Donnell, M. D., Fredholm, Y., De Rouffignac, A., and Hill, R. G. (2008). Structural analysis of a series of strontium-substituted apatites. Acta Biomater. 4 (5), 1455–1464. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2008.04.018

Panda, R. N., Hsieh, M. F., Chung, R. J., and Chin, T. S. (2003). FTIR, XRD, SEM and solid-state NMR investigations of carbonate-containing hydroxyapatite nano-particles synthesized by hydroxide-gel technique. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 64 (2), 193–199. doi:10.1016/s0022-3697(02)00257-3

Peeters, A., De Maeyer, E. A. P., Van Alsenoy, C., and Verbeeck, R. M. H. (1997). Solids modeled by ab initio crystal-field methods. 12. Structure, orientation, and position of A-type carbonate in a hydroxyapatite lattice. J. Phys. Chem. B 101 (20), 3995–3998. doi:10.1021/jp964041m

Penel, G., Leroy, G., Rey, C., and Bres, E. (1998). MicroRaman spectral study of the PO4 and CO3 vibrational modes in synthetic and biological apatites. Calcif. Tissue Int. 63 (6), 475–481. doi:10.1007/s002239900561

Pereyra, M. (2016). Efecto de la nanoestructuración de superficies de titanio para el desarrollo de superficies biocompatibles [dissertation/Ph.D. thesis]. Univ. República, Urug. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12008/32211.

Rey, C., Combes, C., Drouet, C., and Glimcher, M. J. (2009). Bone mineral: update on chemical composition and structure. Osteoporos. Int. 20 (6), 1013–1021. doi:10.1007/s00198-009-0860-y

Safavi, M. S., Walsh, F. C., Surmeneva, M. A., Surmenev, R. A., and Khalil-Allafi, J. (2021). Electrodeposited hydroxyapatite-based biocoatings: recent progress and future challenges. Coatings 11, 110. doi:10.3390/coatings11010110

Shibli, S. M. A., and Jayalekshmi, A. C. (2008). Development of phosphate interlayered hydroxyapatite coating for stainless steel implants. Appl. Surf. Sci. 254 (13), 4103–4110. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.12.051

Tengvall, P., and Lundström, I. (1992). Physico-chemical considerations of titanium as a biomaterial. Clin. Mater. 9, 115–134. doi:10.1016/0267-6605(92)90056-y

Wu, Y. S., Lee, Y. H., and Chang, H. C. (2009). Preparation and characteristics of nanosized carbonated apatite by urea addition with coprecipitation method. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 29 (1), 237–241. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2008.06.018

Keywords: fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, hydroxyapatite coating, implant, second-derivative spectrum, biomaterials

Citation: Pereyra M, Navatta M and Méndez E (2025) Failure in the adhesion of hydroxyapatite coatings to surgical screws: a fourier transform infrared spectroscopy qualitative study. Front. Coat. Dyes Interface Eng. 3:1539792. doi: 10.3389/frcdi.2025.1539792

Received: 04 December 2024; Accepted: 20 January 2025;

Published: 06 February 2025.

Edited by:

Jose L. Endrino, Loyola Andalusia University, SpainReviewed by:

Huatang Cao, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Pereyra, Navatta and Méndez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariana Pereyra, bXBlcmV5cmEucGVyZXpAZmNpZW4uZWR1LnV5

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.