95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Chem. , 31 March 2022

Sec. Solid State Chemistry

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.729608

The present study discusses comparative structural features of fourteen multicomponent solids of two non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Niflumic and Mefenamic acids, with amine and pyridine-based coformers. All the solids were structurally characterized through PXRD, SCXRD, DSC, and the monophasic nature of some of the solids was established through Rietveld refinement. The solid forms include salt, cocrystal, hydrate, and solvate. Except for two, all the solids reported here showed relatively higher solubility compared to the acids. The difference in pKa and similarity in structural features of both the molecules enabled us to study the effect of ΔpKa on crystallization outcome systematically. The structures of all the solids are described through acid-pyridine synthon perspective.

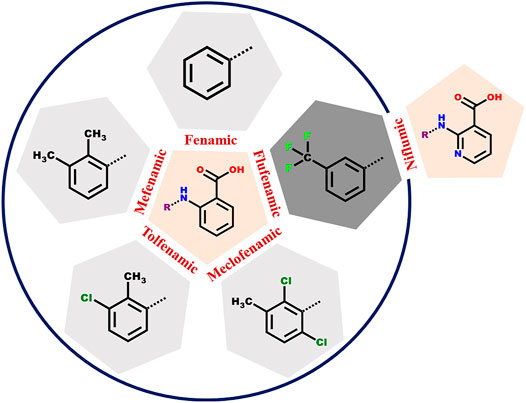

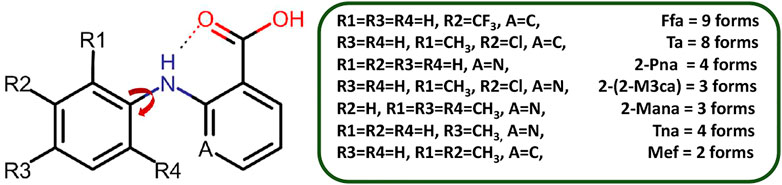

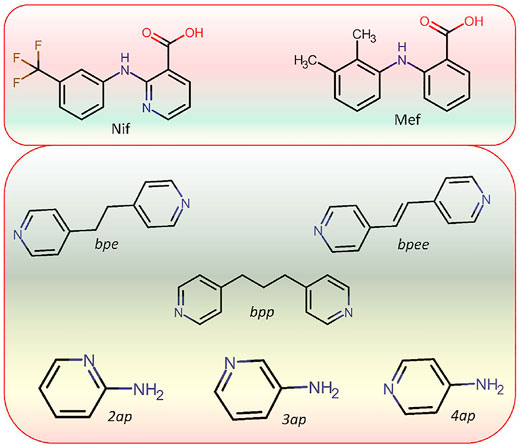

Niflumic acid (Nif) or 2-{[3-(Trifluromethyl)phenyl]amino}nicotinic acid, and Mefenamic acid (Mef) or 2-(2,3-dimethylphenyl) aminobenzoic acid, are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NSAIDs (Uyemura et al., 1997; Sturkenboom, 2005; Khansari and Halliwell, 2009). These NSAIDs are among the most commonly used pharmaceutical molecules, as analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic agents (Dionne and Berthold, 2001; Garg and Azim, 2021). Nif and Mef are used to treat various diseases: Nif is used in rheumatoid arthritis, arthrosis, and joint diseases (Sydnes, 1973), while Mef is prescribed in dental pain, postoperative surgery, premenstrual syndrome, and headache (Bonnar and Sheppard, 1996). Mef has also shown anti-cancer activity (colon and liver cancer) and therapeutic effect in Alzheimer’s disease. Both Nif and Mef (along with Meclofenamic and Tolfenamic acid) belong to a class of NSAIDs called fenamates which are derivatives of anthranilic acid (Scheme 1). Fenamates, generally show poor solubility and high permeability and are classified as Class II drugs as per BCS (Biopharmaceutics Classification System) (SeethaLekshmi and Guru Row, 2012; Bodnár et al., 2017). Radacsi et al. used different crystallization techniques: microwave-assisted evaporation, electrospray, and atmospheric pressure cold plasma to improve the bioavailability of Nif (Radacsi et al., 2012a; Radacsi et al., 2012b; Radacsi et al., 2013). Szunyoghet al. tried nanonization of Niflumic acid by co-grinding to improve dissolution rate (Szunyogh et al., 2013). Wittering et al. employed cocrystallization to prevent polymorphism in fenamates (Wittering et al., 2015). Recently, Bhattacharya et al. improved solubility of fenamates by formation of drug-drug multicomponent solids with another drug trimethoprim (Bhattacharya et al., 2020). Moreover, the extensive use of these drugs regularly worldwide led to their presence in wastewater at higher concentrations than the predicted no effect concentration (Margot et al., 2015; Mila et al., 2019), and removing them can be a challenging task (Greenstein et al., 2018). Based on our earlier experience, robust acid-pyridine synthon can be utilized to tune the solubility of these molecules (Kumar et al., 2018; Goswami et al., 2020). In the first series, we employed 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethane (bpe); 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethylene (bpee), and 1,3-di (4-pyridyl)propane (bpp) with an objective to systematically vary the spacing and flexibility of 4,4-bipyridyl (4,4-bpy), which was earlier used by Wittering et al. as bipyridine are extensively used for the formation of robust material (polymers and membranes), which can further help to remove contaminants from wastewater. In the second series, the three aminopyridines, 2-aminopyridine (2ap), 3-aminopyridine (3ap), and 4-aminopyridine (4ap), were used as coformers to understand the structural chemistry and improve the solubility. Although the amino pyridines do not belong to the GRAS category and out of three 2ap, (LD50 = 200 mg/kg in case of rat when used orally) (Shimizu et al., 2000), 3ap (LD50 = 178 mg/kg in case of quail when used orally) (Shimizu et al., 2000) and 4ap (LD50 = 20 mg/kg in case of rat when used orally) (Schafer, 1973) only the latter is well studied for medicinal use. These commonly used lab chemicals make attractive coformers due to their easy and reliable weak bond formation with a vast range of molecules. A CSD search of Nif showed overall thirty-nine hits, out of which twenty were organic solids. The other NSAID, Mef, showed one hundred and five solids, of which fifty-four were organic solids, of those only 32 and 13 are multicomponent solids, respectively. Fenamates are known to be polymorphic as a consequence of free rotation between the two rings, thus allowing them to have more than one crystal structure (as depicted in Scheme 2); exceptions include a few such as Nif and meclofenamic acid (Delaney et al., 2014; López-Mejías and Matzger, 2015). López-Mejías et al. discovered six new polymorphs for flufenamic acid; the compound is the second most polymorphic molecule (nine polymorphs) after 5-methyl-2-[(2-nitrophenyl)-amino]thiophene-3-carbonitrile or ROY (thirteen polymorphs) (López-Mejías et al., 2012). Uzoh et al. compared crystal energy landscapes of fenamates and showed that conformational flexibility between the two phenyl rings is responsible for this behavior (Uzoh et al., 2012). Though multicomponent solids of Mef are known with bpe, bpee, bpp and 4ap (Nechipadappu and Trivedi, 2017; Zheng et al., 2018), the literature still lacks a comparative study of all these structures and their solubility. A careful analysis of the six selected anthranilic acids with N-based coformers reported in CSD (Supplementary Tables S1, S2) showed acid-pyridine (or N-based co-former) synthon drove the formation of the majority of the multicomponent solids. The table also highlights the need to explore the structural landscape of an acid molecule with a series of structurally related base coformers. Since acid-base interaction is a major driving force, it would be possible to rationalize the composition (A2B, AB or AB2) occurring at the microlevel and how further supramolecular aggregation to a cocrystal, salt or its solvate is facilitated through the functional groups at the periphery of these aggregates. In Scheme 3, we have given the molecular structure of APIs and coformers used in this study. We employed different crystallization techniques and solvent variations to investigate the structural landscape of the system, acid (Nif or Mef)-N-pyridine based conformer-solvent. In Table 1, we have provided the reaction condition for the isolation of the solids reported here.

SCHEME 1. The anthranilic acid derivatives (fenamates) surveyed in this study. The five NSAIDs within the circle have a common anthranilic acid moiety with different substitutions. In case of Flufenamic and Niflumic acids, the difference is the presence of nitrogen instead of carbon in the anthranilic acid ring.

SCHEME 2. Polymorphic forms of fenamate derivatives. The substitutions on the phenyl ring are critical in governing the relative orientation of the two aromatic rings which in turn impacts the number of polymorphic forms as well as how it interacts with a coformer under given conditions. Here, Ffa = Flufenamic Acid, Ta = Tolfenamic Acid, 2-Pna = 2-(phenylamino)nicotinic acid, 2-(2-M3ca) = 2-(2-Methyl-3-chloroanilino)nicotinic acid, 2-Mana = 2-(Mesitylamino)nicotinic acid, Tna = 2-(phynylamino)nicotinic acid, and Mef = Mefenamic Acid.

SCHEME 3. Molecular structure of APIs Niflumic (Nif) and Mefenamic (Mef) acid as well as coformers (bpe, bpee, bpp,2ap,3ap, and 4ap) used in this study.

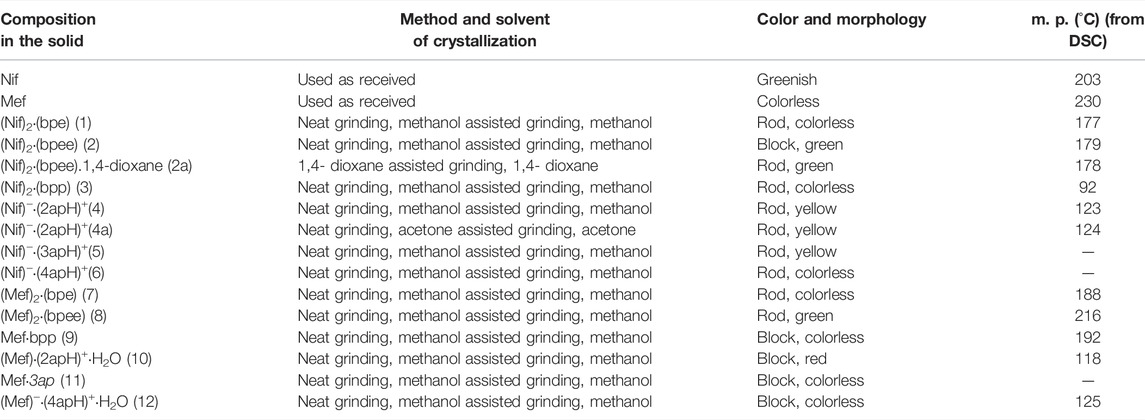

TABLE 1. Crystallization method used for the synthesis of Nif and Mef based multicomponent solids in the present study and their physical properties. Solids 5, 6 and 11 could not be isolated as pure phases.

All the reagents (Nif, Mef, bpe, bpee, bpp, 2ap, 3ap, and 4ap) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were used as received.

The method was used to prepare new solid forms of Nif and Mef based molecules. API and coformer were ground in an agate mortar, either neat or in the presence of two drops of solvent (acetone/methanol/1,4-dioxane). PXRD was used to confirm the formation of the new phase. Good quality crystals suitable for SCXRD were grown by dissolving the powder in a suitable solvent (Table 1).

Both API (1 mM) and conformer (1 mM) was dissolved in an appropriate solvent (2 ml) with gentle stirring till a transparent solution was obtained (usually 10–15 min). The clear solution was kept for crystallization at room temperature. In most cases, good-quality crystals were filtered after seven to 10 days. Ten new and four previously reported multicomponent solids of Nif and Mef were isolated in this study. Crystal data and structure refinement are summarized in Table 2.

X-ray diffraction studies of crystals mounted on a capillary were carried out on a BRUKER AXS SMART-APEX diffractometer with a CCD area detector (MoKα = 0.71073 Å, monochromator: graphite) (Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems, 2000, SMART: Bruker Molecular Analysis Research Tool, Madison, WI, 2000). Frames were collected at T = 298 K by ω, ϕ and 2θ-rotation at 10 s per frame with SAINT (Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems, SAINT-NT., 2001). The measured intensities were reduced to F2 and corrected for absorption with SADABS (Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems, 2001, SAINT-NT., 2001). Structure solution, refinement, and data output were carried out with the SHELXTL program suite on the Olex-2 platform (Dolomanov et al., 2009). Non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. C−H hydrogen atoms were placed in geometrically calculated positions by using a riding model. O−H and N−H hydrogen atoms were localized by difference Fourier maps and refined in subsequent refinement cycles. Images were created with Crystal Impact Diamond software ((Putz et al., nd) Visual Crystal Structure Information, http://www.ccp14.ac.uk/ccp/web-mirrors/crystalimpact/diamond/publ/jac). Hydrogen bonding interactions in the crystal lattice were calculated with SHELXTL.

Solubility of all multicomponent solids reported here was determined using UV-Vis method reported by Choudhury et al. (Karanam and Choudhury, 2013; Joshi and Roy Choudhury, 2018), and Higuchi and Connor in 1965 (Higuchi and Connors, 1965). A measured quantity of each solid was completely dissolved in a large excess of distilled water (pH = 6.8). The stock solutions were suitably diluted to get absorbance values within 1 in the UV-vis spectrum and to prepare standard solutions for generating the calibration curves. The λmax values of Nif/Mef in all the salts were then determined using a PerkinElmer Lambda 1050 UV/Vis/NIR spectrophotometer with a quartz cuvette. The absorbance values of the primary standard solutions were determined at the respective λmax values. The absorbance values were plotted in the y-axis, and the concentrations were plotted in the x-axis, and the points were fitted to a straight line (calibration curve). Simultaneously, a suspension of Nif/Mef in distilled water was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The excess solids were filtered, and the solution was diluted to get the absorbance value within 1 in the UV-vis spectrum. PXRD analysis of the residual solids was carried out to assess the nature of the solid forms. The absorbance of the clear diluted solution was determined at λmax of Nif/Mef for all solids, and the concentration of the salt was determined using the calibration curve, which was generated earlier. The solubility of all the solids was measured at 33°C. The solubility was calculated by multiplying the concentration of the dilute solution by 1,000.

Solubility of all the salts and cocrystals reported in this study was measured and compared with free acids in similar conditions. Crystalline salts of Nif and Mef showed considerable improvement in solubility with aminopyridine coformers compared with bipyridine coformers. In the case of Nif based solids, the salt of Nif with 2ap coformer showed higher solubility while the cocrystals of Nif with bpe and bpee exhibited a decrease in solubility. The salt of 2ap with Mef showed the most remarkable solubility improvement among Mef based solids, while bpe and bpee based solids showed only marginal improvement. We were unsuccessful to correlate the solubility with the percentage of occurrence of various noncovalent interactions. The solubility trends for Nif and Mef based multicomponent solids have been depicted in Supplementary Figure S3. Solubility of the solids 4a, 5, and 11 were not measured due to lack of purity in the samples.

DSC analysis was carried out using a PerkinElmer DSC system on well-ground samples under a nitrogen atmosphere at the rate of 10°C min−1. Room-temperature powder X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer using Ni-filtered CuKα radiation. Data were collected with a step size of 0.05 and at a count time of 1 s per step over the range 10° < 2θ < 50°. A Rietveld treatment of the powder diffraction data of the powder sample was carried out based on single-crystal data using TOPAS 4.2, Bruker to ascertain the homogeneity of the bulk sample (Supplementary Figure S1) (Coelho, 2018, https://www.bruker.com/products/x-ray-diffraction-and-elemental-analysis/x-ray-diffraction/xrd-software/topas.html).

The robust acid-pyridine synthon is the main driving force for the formation of multicomponent solids. In some solids, a proton was transferred from acid to pyridine; in selected cases, solvent/water molecule was included in the crystal. Although π∙∙∙π, C─H∙∙∙π, and C─F∙∙∙H─C interaction played a significant role in the structure formation of all the solids, acid-pyridine synthon remained decisive in dictating the crystal structures. All major synthons involved in this study are shown in Scheme 4. In this system, variation of composition and solvent affected the outcome of crystallization only in two cases. In general, bipyridine coformers, namely, bpe, bpee, and bpp, yielded solids with 2:1 composition as the trimeric acid-pyridine synthon is the main driving force for the supramolecular aggregation. However, solvent variation led to two exceptions: solvated Nifbpee and salt polymorphs Nif·2ap. In the case of aminopyridines as coformers, the outcome of crystallization was a 1:1 salt with Nif based solids. Interestingly, Mef based solids resulted in the form of salt monohydrates.

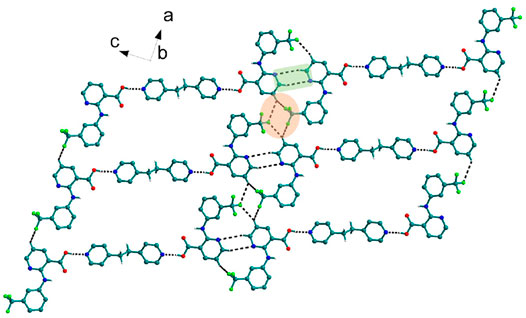

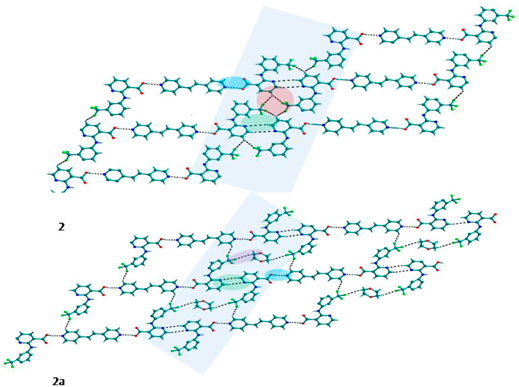

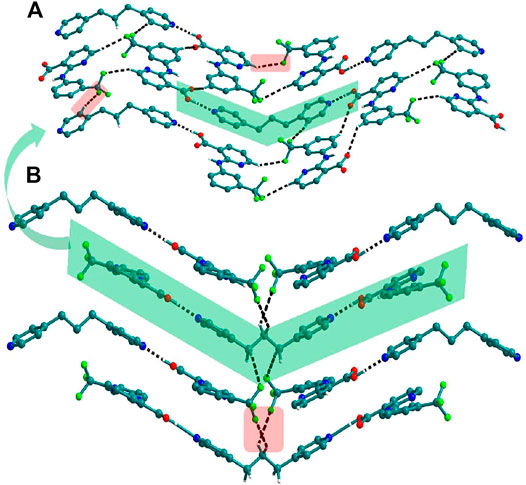

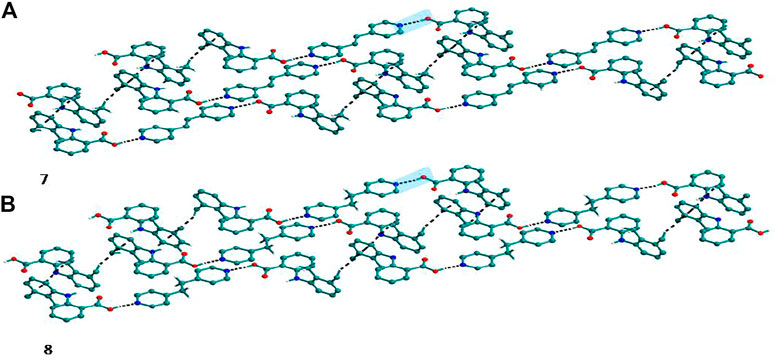

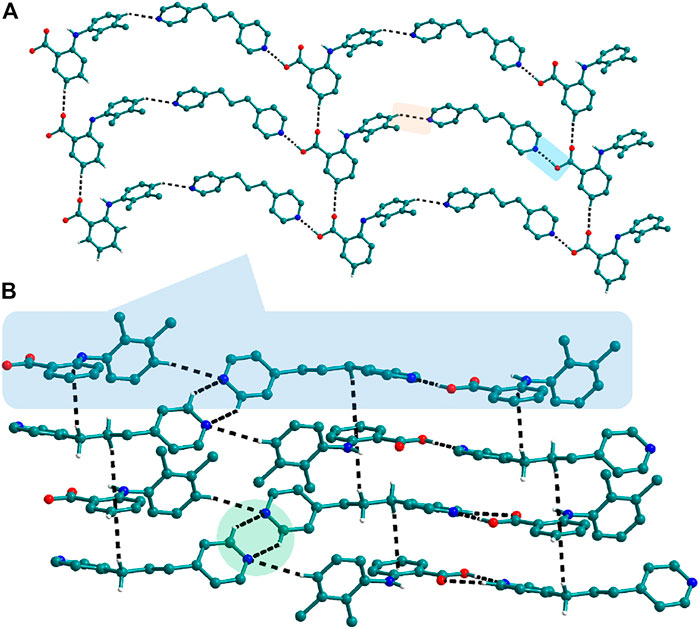

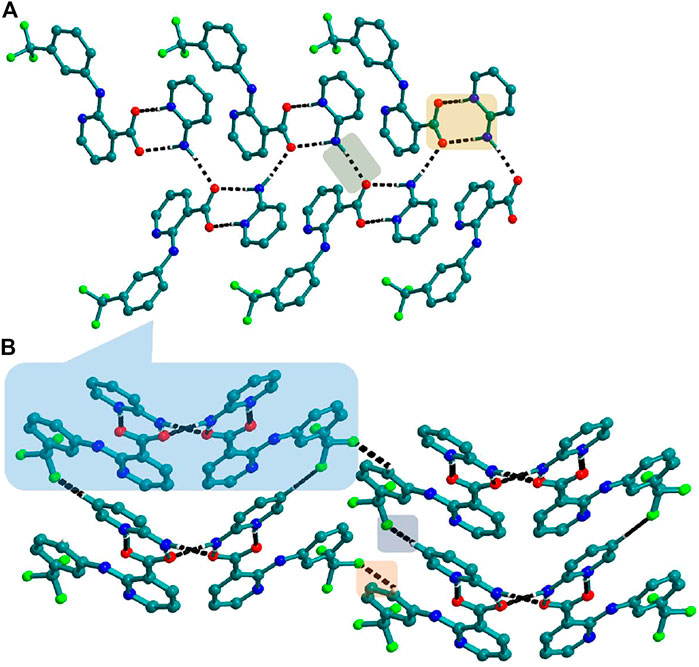

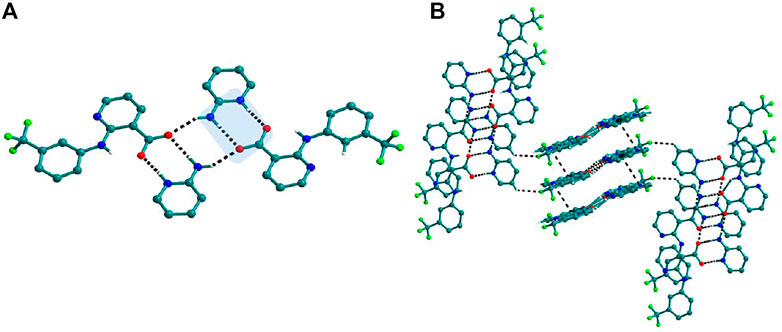

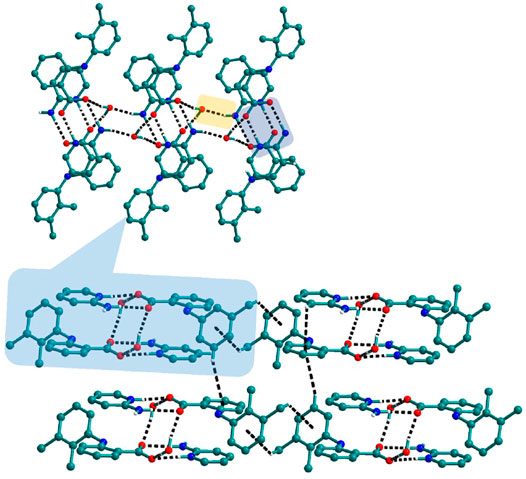

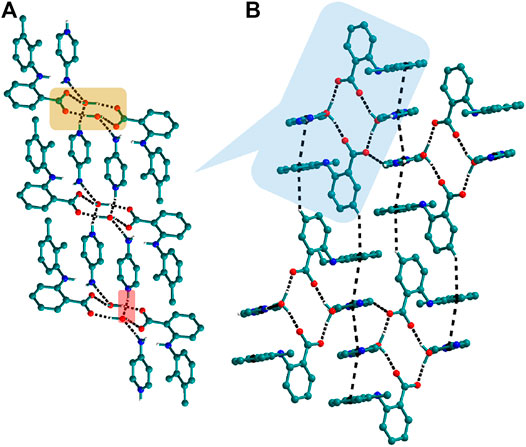

Bipyridine-based coformers like bpe, bpee and bpp formed solids 1, 2, 2a and 3 with Nif and 7, 8, and 9 with Mef. The reaction of Nif and bpe formed a 2:1 cocrystal 1, where two molecules of Nif and one molecule of bpe are present in the asymmetric unit. In 1, the trimer Nif–bpe–Nif, driven by acid-pyridine planar heterosynthon I (Scheme 4), is the main building block. The trimers interact through C─H∙∙∙N (3.08 Å) and C─H∙∙∙F (2.591, 3.022, 2.807, and 3.486 Å), forming a 2D planar sheet (Figure 1). Nif cocrystallized with bpee, forming a 2:1 cocrystal 2, which is isostructural with solid 1. In 2, Nif─bpee─Nif trimers connect with each other through C─H∙∙∙N (3.143 Å) and C─H∙∙∙F (2.653, 3.652, 2.653, and 3.652 Å) interactions (Figure 2). The reaction of Nif with bpee in 1,4-dioxane as solvent formed solid 2a. The only difference between the structure of 2a and the previous two solids is the inclusion of 1,4-dioxane solvent in the crystal structure. In 2a, two trimers are bridged through 1,4-dioxane via C─H-F (2.669 Å) instead of a ring formation (Figure 2). The reaction of Nif with bpp formed a 2:1 cocrystal 3 with one molecule of Nif and half a molecule of bpp in the asymmetric unit. The trimer formed with acid-pyridine synthon again connected through C─H∙∙∙F (2.580 Å and 2.760 Å), resulting in a planar sheet; the sheets are further linked via other C─H∙∙∙F (3.442 Å) interactions (Figure 3). C─H∙∙∙N interactions formed by the nitrogen of the pyridyl group in Nif were also observed in the solids 1, 2 and 2a but were absent in 3. The reaction of Mef with bpe and bpee formed two isostructural solids 7 and 8. The acid∙∙∙pyridine heterosynthon I (Scheme 4) was the major synthon as expected. In both the solids, the trimers are connected through the C─H∙∙∙π bond (3.435 and 3.367 Å) with other trimers on the bc-plane, forming a three-dimensional network (Figure 4). Interestingly, cocrystallization of Mef with bpp yielded 9, wherein a dimer was the building block instead of the usual trimer. The asymmetric unit showed the presence of one molecule of Mef and bpp each. The other pyridine nitrogen of the dimer interacted with the other dimer via C─H∙∙∙N (2.899 Å) interaction, forming a planar sheet (Figure 5A). The sheets are stacked one over the other via C─H∙∙∙π (2.879, 2.933 and 2.897 Å) and C─H∙∙∙N (2.837 Å) interactions (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 1. Nif─bpe─Nif trimers are interacted via C─H∙∙∙N (synthon VII) and C─H∙∙∙F interaction, forming a planar sheet.

FIGURE 2. In 2 and 2a, Nif─bpee─Nif trimers are interconnected via C─H∙∙∙N and C─H∙∙∙F interactions, forming a planar sheet.

FIGURE 3. (A) In 3, Nif─bpp─Nif trimers are connected with other trimers forming a planar sheet via C─H∙∙∙F interaction. (B) Different sheets further connect via other C─H∙∙∙F interactions to form a 3D structure.

FIGURE 4. (A) Mef─bpe─Mef trimers are connected with other trimers via C─H∙∙∙π interaction in 7. (B) Isostructural 8 shows the same types of Mef─bpee─Mef trimers interactions.

FIGURE 5. (A) Nif─bpp dimers interconnected via C─H∙∙∙N forming a planar sheet in 9. (B) Planar sheets via C─H∙∙∙π and C─H∙∙∙N interaction are stacked one over the other, forming a 3D structure.

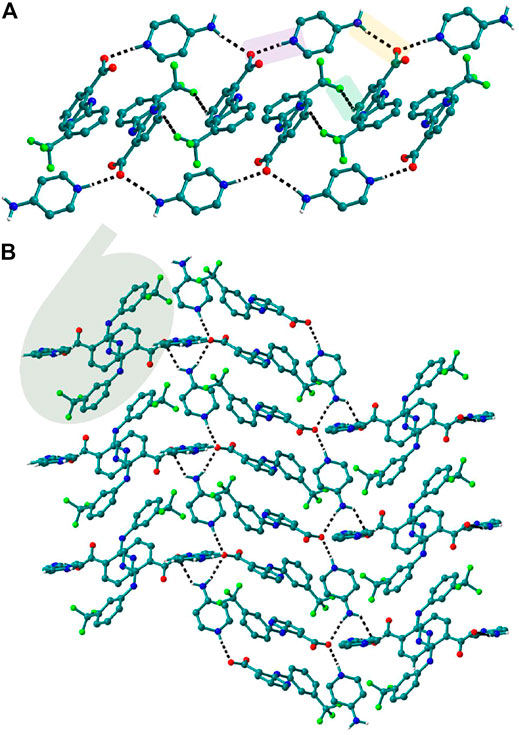

The use of aminopyridine coformers 2ap, 3ap, and 4ap with Nif led to the isolation of the solids 4, 4a, 5, and 6 while Mef yielded the solids 10, 11, and 12. The reaction of Nif and 2ap formed a 1:1 salt 4 and its solvate, 4a. In 4, one molecule each of Nif and 2ap is present in the asymmetric unit. In the dimer formed between Nif and 2ap, the proton transfer from the oxygen of the carboxylate group in Nif to nitrogen of pyridyl group in 2ap ensured the heterosynthon III (Scheme 4) as the main building block. These dimers are connected to each other via N─H∙∙∙O (2.058 Å), where the amino group of 2ap and the other oxygen of carboxylate acting as donor and acceptor, respectively, forming 1D H-bonded chains (Figure 6A); the chains are further interconnected via C─H∙∙∙F (2.669 and 2.586 Å) to form a 3D network (Figure 6B). The salt solvate 4a was isolated when crystallization was carried out in a different solvent (Table 1). In 4a, two molecules, each of Nif and 2ap, are present in the asymmetric unit. The dimer formed through the heterosynthon III (N─H∙∙∙O: 2.647 and 2.857 Å) (Scheme 4) is the main building block. The dimers are further connected via heterosynthon IV (N─H∙∙∙O: 2.871 Å) (Scheme 4), forming a tetramer (Figure 7A). These tetramers are stacked one over the other through C−H∙∙∙π interactions (3.242 and 3.581 Å) forming a layer; these layers cross-link each other via C−H∙∙∙F (3.682 Å) interactions (Figure 7B). Solid 5 contains one molecule each of Nif and 3ap in the asymmetric unit. The solid 6 formed by the reaction of Nif and 4ap, where again dimer formation took place via heterosynthon V (Scheme 4), which are further connected with other dimers through N─H∙∙∙O (2.228 Å), C─H∙∙∙F (2.605 Å), and N─H∙∙∙O (2.228 Å) through the oxygen of the carboxylate moiety of Nif and the amine moiety of 4ap, forming a chain. These chains are further connected with other chains in a perpendicular fashion via C─H∙∙∙O (2.495 Å) and N─H∙∙∙O (2.311 Å) interactions, forming a 3D network (Figure 8). Interestingly, the reaction of Mef with aminopyridine coformers 2ap, 3ap, and 4ap formed two salt hydrates (solids 10 and 12) with the composition 1:1:1 and a cocrystal (solid 11) with the composition 1:1. In 10, Mef and 2ap formed a dimer via synthon III (Scheme 4) like in 4. However, interaction of the dimers was facilitated via water molecules through N─H∙∙∙O (2.007 Å) forming a chain. It should be noted that a similar observation was not found in Nif·2ap, solid 4. These two chains are further mediated by water molecules forming a column involving synthon II via O─H∙∙∙O (1.842 Å and 1.947 Å). These columns further extend through C─H∙∙∙π (3.173 Å and 3.677 Å) to the other two dimensions (Figure 9). The reaction between Mef and 4ap produced a salt hydrate 12, which was recently reported by Trivedi et al. (Nechipadappu and Trivedi, 2017). Surprisingly, there is no acid-pyridine synthon observed in this structure; instead, the nitrogen of the pyridyl group of 4ap interacted with the oxygen of the water molecule. The water mediates a pair of carboxylate dimers from two Mef, forming a tetramer via synthon II (Scheme 4). The tetramers further interact with 4ap through N─H∙∙∙O (1.967 Å and 2.001 Å), forming a column. These columns are further linked to each other through synthon VII, C─H∙∙∙O (2.523 Å), C─H∙∙∙π (3.132 Å), and π∙∙∙π (3.640 Å) interactions (Figure 10).

FIGURE 6. (A) Nif─2ap dimers interacted with other dimers via N─H∙∙∙O to form a 1D Chain in 4. (B) The chains are connected through C─H∙∙∙F in the other two planes forming a 3D network.

FIGURE 7. (A) Interaction of Nif─2ap dimers via N─H∙∙∙O with other dimers to form a tetramer, in 4a. (B) Stacking of tetramer through C−H∙∙∙π interaction one over the other and cross-sects each other via C−H∙∙∙F interaction to form a 3D structure.

FIGURE 8. (A) In 6, Nif─4ap dimers interacted with other dimers via N─H∙∙∙O, forming a 1D Chain. (B) The chains are interconnected via C─H∙∙∙F and C─H∙∙∙O interaction in a perpendicular fashion.

FIGURE 9. In 10, The dimers of Mef─2ap are connected with other dimers through N─H∙∙∙O forming columns. These columns further connect with other columns via C─H∙∙∙π to form a 3D network.

FIGURE 10. (A) In 12, tetramers of Mef─H2O─Mef are formed via synthon II which further connected through N─H∙∙∙O with other tetramers forming columns. (B) These columns, interacting with others via C─H∙∙∙π and π∙∙∙π interactions, form a 3D network.

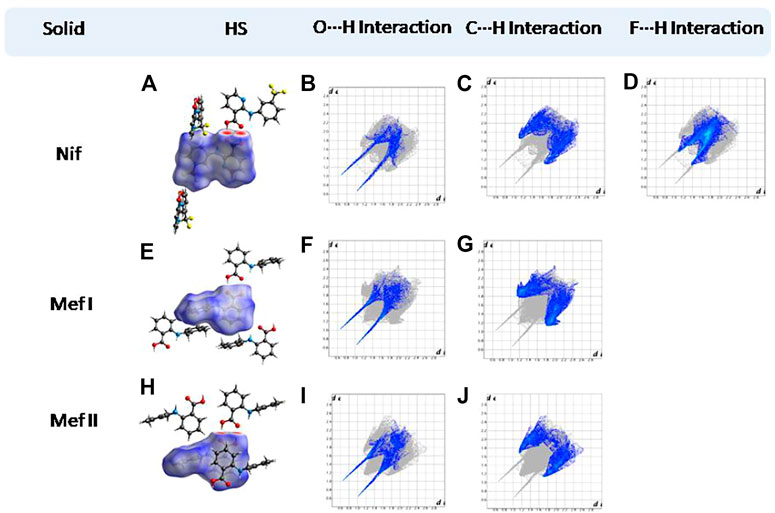

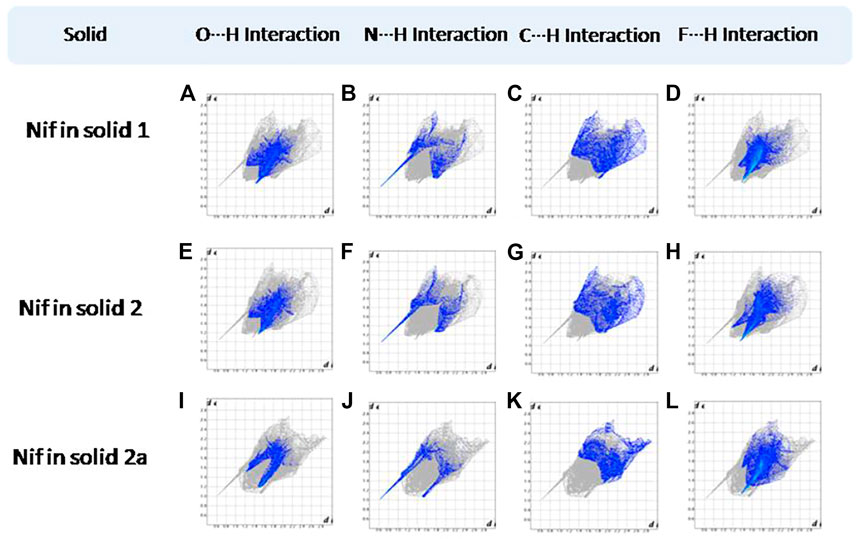

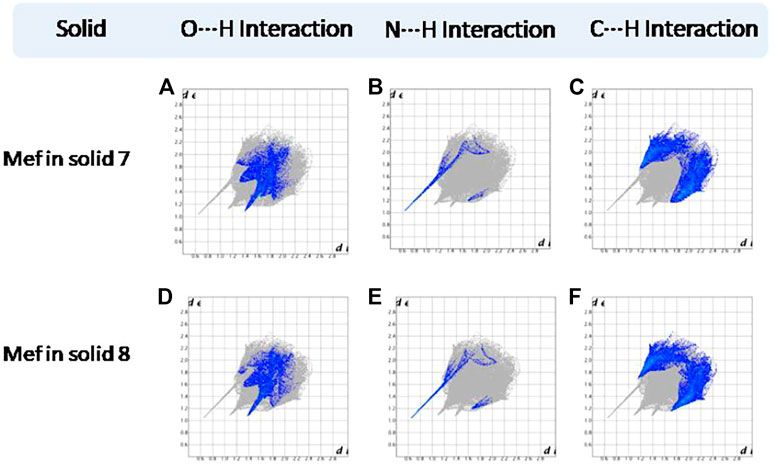

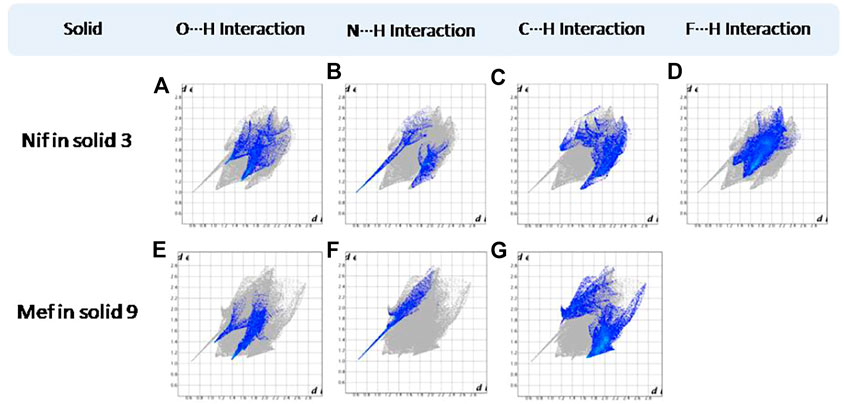

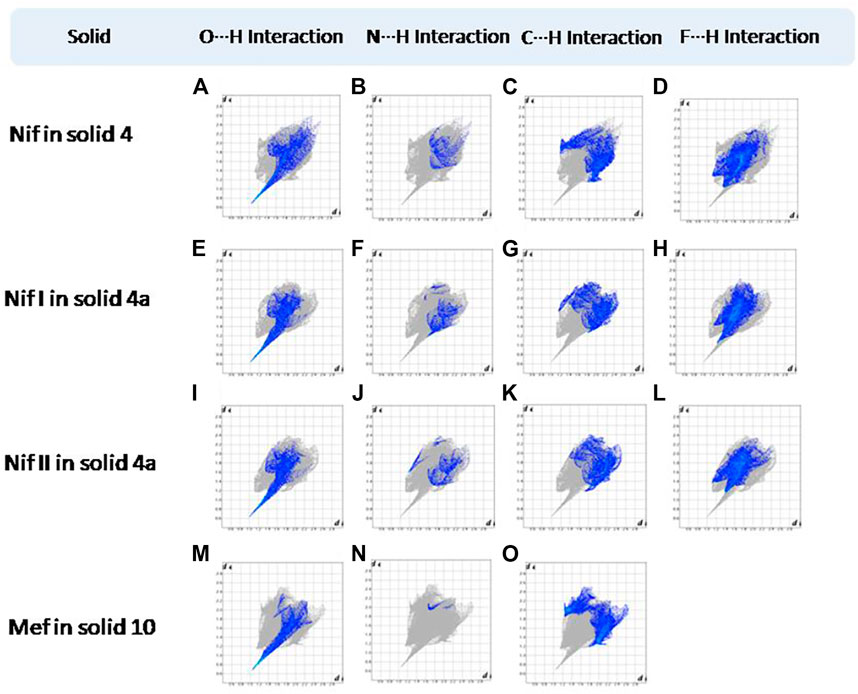

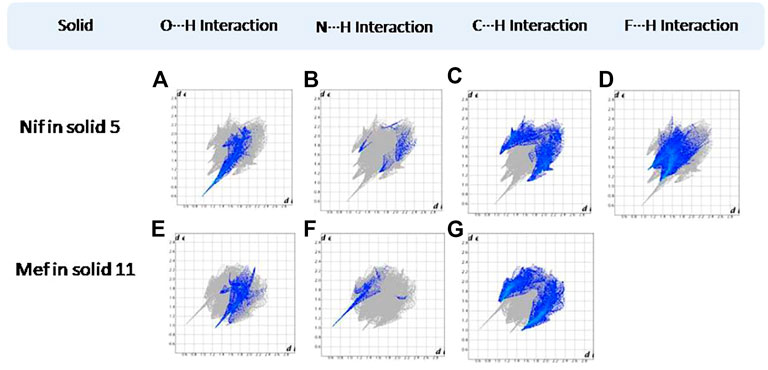

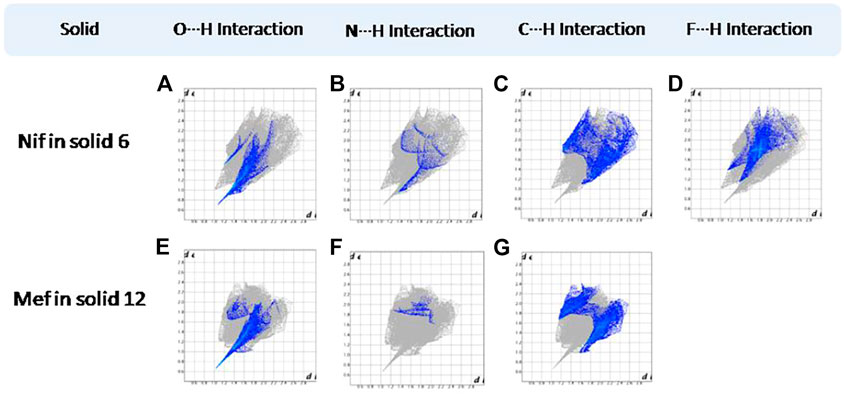

Hirshfeld surfaces (HS) are frequently used to depict various types of interactions in multicomponent solids such as cocrystal, salt, hydrate or solvate and their polymorphs (Spackman and Jayatilaka, 2009). 2D finger plots derived from Hirshfeld surfaces of these solids are particularly helpful to compare intermolecular interactions that are not obvious in structurally similar compounds (Spackman and Jayatilaka, 2009). The fingerprint plots for all the solids prepared in this study were generated using di (distance from the surface to the nearest atom in the molecule) and de (distance from the surface to the nearest atom outside the molecule) as a pair of coordinates in an interval of 0.01 Å, for each surface spot resulting in two-dimensional histograms. The Hirshfeld surface resulted in a 2D plot where different colors (blue to red) indicate different frequencies of the occurrence of interaction. Hirshfeld surfaces and 2D fingerprint plots of the monomorphic Nif (NIFLUM) and dimorphic Mef (XYNAC and XYNAC02) are shown in Figures 11A–J. The HS and fingerprint plots show the variation in the environment of the molecule, which dictates the structural difference. A comparison of Nif and Mef with the coformers bpe and bpee 2D fingerprint plots (1, 2, 2a, 7, and 8) showed similar features (Figures 12, 13). The 2D plots of 1, 2, 2a, 7, and 8 show a single spike corresponding to N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N interaction histogram indicating the disruption of the acid-acid dimer of Nif and Mef via acid-pyridine synthon. Notice the absence of two spikes observed for carboxylic dimer in Figure 11. Both Nif molecules present in the asymmetric unit of 1 showed a similar histogram except for a slight difference in F∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙F interactions. The 2D fingerprint plots of Mef in 7 and 8 (Figure 13) showed exactly similar features due to the isostructural nature of 7 and 8. A comparison of 2D plots of Nif and Mef with the conformer bpp (Figure 14) in 3 and 9 again showed the absence of the characteristic “two spikes” of O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O interaction and the presence of a single spike in N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N interaction due to carboxylic acid dimer disruption and acid-pyridine synthon formation. The difference in N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N histogram in 3 and 9 can be attributed to the difference in composition of acid and base in the solids. Solid 3 is a 2:1 acid-pyridine trimer, while 9 is an acid-pyridine dimer. The second nitrogen of bpp is involved in C−H∙∙∙N interaction, as is inferred by the presence of shoulder in N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N histogram of 9 (Figure 14G). The 2D fingerprint plots of Nif with the conformer 2ap in solids 4 and 4a and Mef in 10 (Figure 15) showed the absence of N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N interaction; the presence of one single spike in O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O interaction histogram specifies the O∙∙∙H interaction, which is due to proton transfer from Nif and Mef to 2ap. The C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C interaction histogram of Nif (Figures 15C,G) is different in 4 and 4a due to the difference in the extent of C−H∙∙∙π bonding in these solids. The fingerprint plots of Nif and Mef in 5 and 11 are depicted in Figure 16 and in 6 and 12 in Figure 17. The latter showed similar features of 4 and 10, indicating the salt formation with 4ap.

FIGURE 11. (A,E,H) Hirshfeld surface analysis and structural environment of Nif, Mef I, and Mef II. (B–D) O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O, C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C, and F∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙F interactions resolved fingerprint plots of Nif. (F,G) and (I,J) O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O and C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C interactions resolved fingerprint plots of both forms of Mef. The two spikes present in the solids are characteristic of the carboxylic acid dimer.

FIGURE 12. (A–D) O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C, and F∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙F interactions Resolved fingerprint plots of Nif in solid 1, respectively. (E–L) O∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙O and N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N interactions resolved fingerprint plots of Nif of solid 2 and 2a, respectively.

FIGURE 13. (A–F) Resolved fingerprint plots of Mef of 7 and 8 in O∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, and C∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙C interactions, respectively.

FIGURE 14. (A–D) Resolved fingerprint plots of Nif of solid 3 in O∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, C∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙C, and F∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙F interactions, respectively. (E–G) Resolved fingerprint plots of Mef of solid 9 in O∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, and C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C interactions, respectively.

FIGURE 15. (A–L) Resolved fingerprint plots of Nif in 4 and Nif I &Nif II in 4a in O∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C, and F∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙F interactions, respectively. (M–O) Resolved fingerprint plots of Mef of 10 in O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, and C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C interactions, respectively.

FIGURE 16. (A–D) Resolved fingerprint plots of Nif in 5 in O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C, and F∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙F interactions, respectively. (E–G) Resolved fingerprint plots of Mef in 11 in O∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, and C∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙C interactions, respectively.

FIGURE 17. (A–D) Resolved fingerprint plots of Nif in 6 in O∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, C∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙C, and F∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙F interactions, respectively. (E–G) Resolved fingerprint plots of Mef in 12 in O∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙O, N∙∙∙H/H∙∙∙N, and C∙∙∙H/ H∙∙∙C interactions, respectively.

Crystallization of acid with a series based on structurally similar basic coformers ΔpKa. The molecular salts for the carboxylic acid–pyridine reaction have a COO∙∙∙provided a platform to explore the structural difference due to H–Narom heterosynthon, while the cocrystals have a COO–H∙∙∙Narom heterosynthon. Formation of a cocrystal or a salt is usually predicted by an empirical indicator, the ΔpKa [ΔpKa (base) − ΔpKa (acid)] rule. (Sarma et al., 2009; Stahl et al., 2011; Lemmerer et al., 2015). As a general rule, ΔpKa< 0 yields a cocrystal, while ΔpKa> 3.75 leads to a salt (Childs et al., 2007; Delori et al., 2013). It is generally believed that the cocrystal or salt, or both, can appear in the domain between 0 and 4, though proton transfer is unpredictable in this region (Cruz-Cabeza, 2012). We validated the ΔpKa rule to all the multicomponent solids reported in this study as these were the products of acid and base. We found good agreement in all the cases. Solids which have ΔpKa ˃ 3.75 (4, 4a, 5, 6, 10 and 12) exclusively formed salts while solids with ΔpKa ˂ 3.75 (1, 2, 2a, 3, 7, 8, 9 and 11), resulted in the formation of a cocrystal. The data has been summarized in (Table 3).

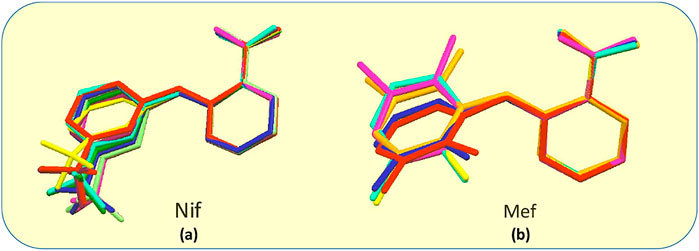

Fenamates, due to their free rotation around the dihedral C‒C‒N‒C bond, showed conformational polymorphs. The flexibility of free Nif/Mef in its salts/cocrystals enables the molecule to show different conformations in the solid-state. Both Nif and Mef are very flexible molecules, as can be seen from Table 4. Their different conformations are depicted in an overlayed fashion in Figure 18. Mef is dimorphic, while Nif is monomorphic. This conformational flexibility enabled Nif/Mef to form multicomponent solids with efficient hydrogen-bonding packing. The difference in torsion angles among all the solids based on Nif is evidence of its conformational flexibility. Two different Nif molecules in the asymmetric unit of 1 have almost equal torsion angles in the opposite direction. The torsion angles in Nif based solids although vary in different forms. In the case of Mef based solids, the torsion angle of 8 is close to Mef II, while in 7, 9, 10, 11, and 12, it is different. To summarize, Nif based solids have torsion angles close to 0° or parallel, while the Mef based solids have torsion angles close to 90° or perpendicular. The ortho substitution in Mef could be the probable reason for this variation.

FIGURE 18. (A) Molecular overlay diagrams of Nif in salts/cocrystals. Color codes: Light blue‒Nif, Red‒1, Orange‒2, Yellow‒2a, Green‒3, Cyan‒4, Blue‒4a, Purple‒5, Magenta‒6. (B) Molecular overlay diagrams of Mef molecule in salts/cocrystals. Color codes: Light blue‒Mef I, Green‒Mef II, Red‒7, Orange‒8, Yellow‒9, Cyan‒10, Blue‒11, Purple‒12.

CSD analysis of the six selected anthranilic acid based NSAIDs (A) with N-containing co-formers (B) solids (Supplementary Scheme S1, Supplementary Tables S1, S2), led to the following conclusions based on the structural features. 4,4′-bipy is the only reported coformer that formed 2:1 cocrystal (A2B) with all the six acids surveyed here. Interestingly the crystal structures of all the six solids were dominated by the trimeric acid pyridine synthon (A٠٠٠B٠٠٠A) as observed in all bipyridine solids (1, 2, 2a, 3, 7 and 8) reported here except solid 9. As expected, 4,4′-azopyridine is also reported to form a cocrystal with composition A2B. In the case of reaction with bpee, we obtained a cocrystal solvate concomitantly. The solid 9 (AFOPAP) showed a rare coformer-coformer homosynthon (synthon VII in Scheme 4) which could be a contributing factor towards its composition of 1:1 (Zheng et al., 2018).

Monopyridine containing solids such as acridine, methyl, chloro or amide substituted pyridine invariably led to anhydrous 1:1 cocrystals. The solvent DMF, sulfamethazine and pyridine-2-one all formed 1:1 solid. An interesting addition the cocrystal 11 formed between Mef (pKa = 5.75) and 3ap. The same coformer, however, yielded a 1:1 salt (solid 5) with Nif. All coformers containing a single amino group formed only 1:1 salt with fenamic acids. Piperazine (more basic one) is the only coformer that showed both 2:1 and 1:1 salts and hydrates with the acids, Mef, Tol and Mec. The two cyclic tetramine and ethylenediamine gets easily diprotonated and hence formed salts of the composition, AB2. Only three salts with refcodes BEBGOH, ZAZGEO, and JUDPUW showed a deviation in composition with the occurrence of AB2 for the first two and A2B for the last one. The three examples suggested that apart from charge balance (e.g. A−B+), microscopic stabilization of the building blocks (dimer, trimer, etc) could lead to inclusion of a neutral coformer as in AB2 or A2B or solvent in the final outcome of the crystallization.

It was observed that, statistically, ortho substituted fenamates, namely, Mefenamic acid (Mef), Tolfenamic acid (Tol), and Meclofenamic acid (Mec), showed higher tendency (39, 41 and 33%, respectively) to form solvates than Flufenamic acid (Flu) and Niflumic Acid (Nif) (18 and 10% respectively). It should be noted that Flu and Nif have higher chance of free rotation around the dihedral angle for better packing efficiency; this conformational rotation is restricted in Mef, Tol and Mec due to ortho substitution. The two acids, a sulfonic and maleic formed 1:1 salt with a protonated Nif with a favorable -COO٠٠٠H−N (py).

The present study demonstrates the robustness of acid∙∙∙pyridine synthon to design new cocrystals, salts, salt-cocrystals, and salt hydrates based on Nif and Mef. The presence of conformational flexibility enables Nif/Mef to form multicomponent solids with efficient hydrogen-bonding packing. The Nif molecules present in the asymmetric unit of 1 showed two confirmations having almost equal torsion angles in the opposite direction. To compare, torsion angles of Nif based solids are close to 0° or parallel, while the Mef based solids have torsion angles close to 90° or perpendicular. This variation can probably be ascribed to the ortho substitution in Mef. The stoichiometry of the resulting solids is governed by conformational flexibility and/or supramolecular aggregation. The structural differences of Nif and Mef based solids are discussed via fingerprint plots generated through Hirshfeld surface analysis. The impact of ΔpKa has been discussed and validated on Nif and Mef based solids. Apart from the two bipyridine based solids (1 and 2), relative solubilities of the solids showed an increase compared to their respective fenamates.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

AR conceived the idea as he has been working in this field for over 25 years. VK has a lead role in designing the synthesis and characterization of the solids. PG supported in synthesis and data collection. Balendra helped in the refinement of crystal structures and supported in data collection and analysis. ST helped in data analysis, carried out the literature analysis and reviewing tasks.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

VK, PG, and Balendra acknowledge UGC for a research fellowship. ST and AR acknowledge DST, Government of India, for financial support and powder and single-crystal X-ray diffraction facility (DST: SR/FST/CSII-07/2014) to the Department of Chemistry, IIT Delhi, India.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2022.729608/full#supplementary-material

Bhattacharya, B., Das, S., Lal, G., Soni, S. R., Ghosh, A., Reddy, C. M., et al. (2020). Screening, crystal Structures and Solubility Studies of a Series of Multidrug Salt Hydrates and Cocrystals of Fenamic Acids with Trimethoprim and Sulfamethazine. J. Mol. Struct. 1199, 127028. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.127028

Bodnár, K., Hudson, S. P., and Rasmuson, Å. C. (2017). Stepwise Use of Additives for Improved Control over Formation and Stability of Mefenamic Acid Nanocrystals Produced by Antisolvent Precipitation. Cryst. Growth Des. 17, 454–466. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.6b01256

Bonnar, J., and Sheppard, B. L. (1996). Treatment of Menorrhagia during Menstruation: Randomised Controlled Trial of Ethamsylate, Mefenamic Acid, and Tranexamic Acid. BMJ 313, 579–582. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7057.579

Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems (2000). SMART: Bruker Molecular Analysis Research Tool. Madison, WI: Bruker AXS.

Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems, SAINT-NT (2001). Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems. SAINT + NT, Version 6.04. Madison, WI. Bruker AXS.

Childs, S. L., Stahly, G. P., and Park, A. (2007). The Salt−Cocrystal Continuum: The Influence of Crystal Structure on Ionization State. Mol. Pharmaceutics 4, 323–338. doi:10.1021/mp0601345

Coelho, A. A. (2018). TOPAS and TOPAS-Academic: An Optimization Program Integrating Computer Algebra And Crystallographic Objects Written in C++. J. Appl. Cryst. 51, 210–218. doi:10.1107/S1600576718000183

Cruz-Cabeza, A. J. (2012). Acid-base Crystalline Complexes and the pKa Rule. CrystEngComm 14, 6362. doi:10.1039/c2ce26055g

Delaney, S. P., Smith, T. M., and Korter, T. M. (2014). Conformational Origins of Polymorphism in Two Forms of Flufenamic Acid. J. Mol. Struct. 1078, 83–89. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.02.001

Delori, A., Galek, P. T. A., Pidcock, E., Patni, M., and Jones, W. (2013). Knowledge-based Hydrogen Bond Prediction and the Synthesis of Salts and Cocrystals of the Anti-malarial Drug Pyrimethamine with Various Drug and GRAS Molecules. CrystEngComm 15, 2916. doi:10.1039/c3ce26765b

Dionne, R. A., and Berthold, C. W. (2001). Therapeutic Uses of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in Dentistry. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 12, 315–330. doi:10.1177/10454411010120040301

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K., and Puschmann, H. (2009). OLEX2: a Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 339–341. doi:10.1107/S0021889808042726

Garg, U., and Azim, Y. (2021). Challenges and Opportunities of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals: a Focused Review on Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. RSC Med. Chem. 12, 705–721. doi:10.1039/D0MD00400F

Goswami, P. K., Kumar, V., and Ramanan, A. (2020). Multicomponent Solids of Diclofenac with Pyridine Based Coformers. J. Mol. Struct. 1210, 128066. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128066

Greenstein, K. E., Lew, J., Dickenson, E. R. V., and Wert, E. C. (2018). Investigation of Biotransformation, Sorption, and Desorption of Multiple Chemical Contaminants in Pilot-Scale Drinking Water Biofilters. Chemosphere 200, 248–256. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.107

Higuchi, T., and Connors, K. A. (1965). Phase Solubility Techniques. Adv. Anal. Chem. Instrumentation 4, 117–212.

Joshi, M., and Roy Choudhury, A. (2018). Salts of Amoxapine with Improved Solubility for Enhanced Pharmaceutical Applicability. ACS Omega 3, 2406–2416. doi:10.1021/acsomega.7b02023

Karanam, M., and Choudhury, A. R. (2013). Structural Landscape of Pure Enrofloxacin and its Novel Salts: Enhanced Solubility for Better Pharmaceutical Applicability. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 1626–1637. doi:10.1021/cg301831s

Khansari, P. S., and Halliwell, R. F. (2009). Evidence for Neuroprotection by the Fenamate NSAID, Mefenamic Acid. Neurochem. Int. 55, 683–688. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2009.06.014

Kumar, V., Goswami, P. K., Thaimattam, R., and Ramanan, A. (2018). Multicomponent Solids of Uracil Derivatives - Orotic and Isoorotic Acids. CrystEngComm 20, 3490–3504. doi:10.1039/C8CE00486B

Lemmerer, A., Govindraju, S., Johnston, M., Motloung, X., and Savig, K. L. (2015). Co-crystals and Molecular Salts of Carboxylic Acid/pyridine Complexes: Can Calculated pKa's Predict Proton Transfer? A Case Study of Nine Complexes. CrystEngComm 17, 3591–3595. doi:10.1039/C5CE00102A

López-Mejías, V., Kampf, J. W., and Matzger, A. J. (2012). Nonamorphism in Flufenamic Acid and a New Record for a Polymorphic Compound with Solved Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9872–9875. doi:10.1021/ja302601f

López-Mejías, V., and Matzger, A. J. (2015). Structure-Polymorphism Study of Fenamates: Toward Developing an Understanding of the Polymorphophore. Cryst. Growth Des. 15, 3955–3962. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00570

Margot, J., Rossi, L., Barry, D. A., and Holliger, C. (2015). A Review of the Fate of Micropollutants in Wastewater Treatment Plants. WIREs Water 2, 457–487. doi:10.1002/wat2.1090

Mila, E., Nika, M.-C., and Thomaidis, N. S. (2019). Identification of First and Second Generation Ozonation Transformation Products of Niflumic Acid by LC-QToF-MS. J. Hazard. Mater. 365, 804–812. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.11.046

Nechipadappu, S. K., and Trivedi, D. R. (2017). Structural and Physicochemical Characterization of Pyridine Derivative Salts of Anti-inflammatory Drugs. J. Mol. Struct. 1141, 64–74. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.03.086

Putz, H., Brandenburg, K., and Kreuzherrenstr, G. R. (nd). Diamond - Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization. Crystal Impact 102, 53227. Available at:https://www.crystalimpact.de/diamond.

Radacsi, N., Ambrus, R., Szabó-Révész, P., van der Heijden, A., and ter Horst, J. H. (2012a). Atmospheric Pressure Cold Plasma Synthesis of Submicrometer-Sized Pharmaceuticals with Improved Physicochemical Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 5090–5095. doi:10.1021/cg301026b

Radacsi, N., Ambrus, R., Szunyogh, T., Szabó-Révész, P., Stankiewicz, A., van der Heijden, A., et al. (2012b). Electrospray Crystallization for Nanosized Pharmaceuticals with Improved Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 3514–3520. doi:10.1021/cg300285w

Radacsi, N., ter Horst, J. H., and Stefanidis, G. D. (2013). Microwave-Assisted Evaporative Crystallization of Niflumic Acid for Particle Size Reduction. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 4186–4189. doi:10.1021/cg4010906

Sarma, B., Nath, N. K., Bhogala, B. R., and Nangia, A. (2009). Synthon Competition and Cooperation in Molecular Salts of Hydroxybenzoic Acids and Aminopyridines. Cryst. Growth Des. 9, 1546–1557. doi:10.1021/cg801145c

Schafer, E. (1973). A Summary of the Acute Toxicity of 4-aminopyridine to Birds and Mammals. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 26, 532–538. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(73)90291-3

SeethaLekshmi, S., and Guru Row, T. N. (2012). Conformational Polymorphism in a Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug, Mefenamic Acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 4283–4289. doi:10.1021/cg300812v

Shimizu, S., Watanabe, N., Kataoka, T., Shoji, T., Abe, N., Morishita, S., et al. (2000). “Pyridine and Pyridine Derivatives,” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA). doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_399

Spackman, M. A., and Jayatilaka, D. (2009). Hirshfeld Surface Analysis. CrystEngComm 11, 19–32. doi:10.1039/B818330A

Stahl, P. H., and Wermuth, C. G.International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2011). Handbook of Pharmaceutical Salts: Properties, Selection, and Use. 2nd rev (Weinheim: Wiley VCH).

Sturkenboom, M., Nicolosi, A., Cantarutti, L., Mannino, S., Picelli, G., Scamarcia, A., et al. (2005). Incidence of Mucocutaneous Reactions in Children Treated with Niflumic Acid, Other Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs, or Nonopioid Analgesics. PEDIATRICS 116, e26–e33. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0040

Sydnes, O. A. (1973). A Clinical Investigation of Niflumic Acid in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2, 8–11. doi:10.3109/03009747309095202

Szunyogh, T., Ambrus, R., and Szabó-Révész, P. (2013). Nanonization of Niflumic Acid by Co-grinding. ANP 02, 329–335. doi:10.4236/anp.2013.24045

Uyemura, S. A., Santos, A. C., Mingatto, F. E., Jordani, M. C., and Curti, C. (1997). Diclofenac Sodium and Mefenamic Acid: Potent Inducers of the Membrane Permeability Transition in Renal Cortex Mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 342, 231–235. doi:10.1006/abbi.1997.9985

Uzoh, O. G., Cruz-Cabeza, A. J., and Price, S. L. (2012). Is the Fenamate Group a Polymorphophore? Contrasting the Crystal Energy Landscapes of Fenamic and Tolfenamic Acids. Cryst. Growth Des. 12, 4230–4239. doi:10.1021/cg3007348

Wittering, K. E., Agnew, L. R., Klapwijk, A. R., Robertson, K., Cousen, A. J. P., Cruickshank, D. L., et al. (2015). Crystallisation and Physicochemical Property Characterisation of Conformationally-Locked Co-crystals of Fenamic Acid Derivatives. CrystEngComm 17, 3610–3618. doi:10.1039/C5CE00297D

Keywords: cocrystallization, acid-pyridine synthon, intermolecular interactions, ΔpKa rule, hirshfeld surface analysis

Citation: Kumar V, Goswami PK, Balendra , Tewari S and Ramanan A (2022) Multicomponent Solids of Niflumic and Mefenamic Acids Based on Acid-Pyridine Synthon. Front. Chem. 10:729608. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.729608

Received: 23 June 2021; Accepted: 25 February 2022;

Published: 31 March 2022.

Edited by:

Venu R. Vangala, University of Bradford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Srinivasulu Aitipamula, Institute of Chemical and Engineering Sciences (A∗STAR), SingaporeCopyright © 2022 Kumar, Goswami, Balendra, Tewari and Ramanan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arunachalam Ramanan, YXJhbWFuYW41N0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.