- 1School of Mechanical Science & Engineering, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, China

- 2Department of Physics and Astronomy, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA

- 3State Key Laboratory of Material Processing and Die & Mound Technology, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, China

Nanocomposites are becoming a new paradigm in thermoelectric study: by incorporating nanophase(s) into a bulk matrix, a nanocomposite often exhibits unusual thermoelectric properties beyond its constituent phases. To date most nanophases are binary, while reports on ternary nanoinclusions are scarce. In this work, we conducted an exploratory study of introducing ternary (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x inclusions in the host matrix of Yb0.25Co4Sb12. Yb0.25Co4Sb12-4wt% (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x nanocomposites were prepared by a melting-milling-hot-pressing process. Microstructural analysis showed that poly-dispersed nanosized Ag-Sb-Te inclusions are distributed on the grain boundaries of Yb0.25Co4Sb12 coarse grains. Compared to the pristine nanoinclusion-free sample, the electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, and thermal conductivity were optimized simultaneously upon nanocompositing, while the carrier mobility was largely remained. A maximum ZT of 1.3 was obtained in Yb0.25Co4Sb12-4wt% (Ag2Te)0.42(Sb2Te3)0.58 at 773 K, a ~ 40% increase compared to the pristine sample. The electron and phonon mean-free-path were estimated to help quantify the observed changes in the carrier mobility and lattice thermal conductivity.

Introduction

In the wake of severe environmental and energy crisis, thermoelectric (TE) materials, which can convert heat to electricity directly, have attracted much attention (Dresselhaus et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012; Alam and Ramakrishna, 2013). The conversion efficiency of a TE material is determined by its dimensionless figure of merit ZT = α2T∕ρκ, where α, ρ, κ, T are Seebeck coefficient, electrical resistivity, total thermal conductivity, and absolute temperature, respectively. The term α2∕ρ is called power factor. The total thermal conductivity κ is composed of electronic component κe and lattice component κL.

A general challenge in single-phased bulk TE material is that all three TE properties, the electrical conductivity, the Seebeck coefficient, and the electronic thermal conductivity, are intimately but adversely inter-dependent, optimizing one often degrades others. In this regard, nanostructuring has provided a new route to partially decouple the TE properties, as evidenced in supperlattice (Venkatasubramanian et al., 2001; Harman et al., 2002; Zeng et al., 2009) and nanocomposites (Hsu et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2005; Poudel et al., 2008; Fan et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012; Alam and Ramakrishna, 2013), by enhancing the power factor and/or lowering the κL. Nanostructuring in bulk materials can be realized by directly incorporating nanoparticles in the host matrix (Fan et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012), or creating nanoparticles in situ (Hsu et al., 2004), or reducing the host matrix particle size down to nanometer scale (Poudel et al., 2008). A number of approaches have been proposed to enhance the power factor, mostly via enhancing the Seebeck coefficient by (i) creating sharp features in the density-of-states, for instance, by introducing resonant states (Heremans et al., 2008; Ahn et al., 2010), and (ii) increasing the energy dependence in the relaxation times, for instance, by energy filtering effect at the interface (Heremans et al., 2005; Shakouri and Zebarjadi, 2009). Recently, a modulation-doping mechanism has been proposed to enhance the mobility therefore the electrical conductivity as compared to its uniform-doping counterpart (Zebarjadi et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2012). In the mean time, many ZT enhancements in nanocomposites are owing to the significant reduction of κL, via strong interface scattering of heat-carrying phonons.

CoSb3-based filled-skutterudites have been known as promising TE materials for medium-temperature power generation applications (Yang et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2011; Peng et al., 2012a; Rogl et al., 2014). Despite the tremendous progress in developing high performance filled-skutterudites, there is still room for further reduction of κL, especially in n-type filled-skutterudites, as compared to other state-of-the-art TE materials. The future of CoSb3-based filled-skutterudites is largely hinged upon further reduction of κL while remaining or even increasing the power factor.

To this end, introducing AgSbTe2 nanoinclusions in the host matrix of Yb0.2Co4Sb12 proved to be an effective approach. AgSbTe2 is by itself a promising TE material (Xu et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2013). Its extremely low κL (~0.6 W/m-K at room temperature; Rosi et al., 1961) has been attributed to strong anharmonicity (Morelli et al., 2008; Nielsen et al., 2013), cation force-constant disorder (Ye et al., 2008), and also prominent nanostructural features including naturally formed nanoscale modulations and nanodomains with Ag and Sb ordering (Ma et al., 2013; Carlton et al., 2014). In our previous study, we chose AgSbTe2 as the nanoinclusion in the host matrix of micro-grained Yb0.2Co4Sb12 skutterudite. We found that the addition of AgSbTe2 nanoinclusions simultaneously optimized {ρ, α, κ} and attained much improved ZT values when the nanoinclusion weight percentage was between 4 and 6 wt% (Fu et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2014). Importantly, there is a topological crossover for the AgSbTe2 inclusions from isolated nanoparticles to nano-coating between 6 and 8 wt%. Above this crossover, the composite with high AgSbTe2 content turned to behave like a conventional two-phase composite that can be described by an effective-medium model, and the ρ and α were degraded (Peng et al., 2014).

Building on these results, we intend to further optimize the TE performance of filled-skutterudite nanocomposite. Note that AgSbTe2 can be regarded as a solid solution between Ag2Te and Sb2Te3 from the metallurgical viewpoint, multi-phase nanocomposites, and complicated nanostructures can be formed by varying Ag2Te:Sb2Te3 ratios in AgSbTe2-based materials (Wang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2010a,b). Hence, in the present work we extend the study into a more complicated phase space by varying the Ag2Te:Sb2Te3 ratio but fixing the overall weight percentage of (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x at 4 wt%, in the hopes that the increased phase interfaces may enhance the α via energy filtering effect and reduce the κL via interface scattering.

Experimental Procedures

Yb0.25Co4Sb12 and (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x (x = 0.36, 0.40, 0.42, 0.46) were separately synthesized. For Yb0.25Co4Sb12, stoichiometric amounts of Co powder (99.5%), Sb shot (99.99%), and Yb ingot (99.9%) were mixed and sealed in evacuated quartz tubes, which were slowly heated to 1323 K and held for 24 h, then cooled to 923 K and held for another 4 days, before furnace-cooled to room temperature. For (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x, appropriate amounts of Ag powder (99.9%), Sb shot (99.99%), and Te powder (99.99%) were mixed and sealed in evacuated quartz tubes, heated to 1273 K and held for 10 h, after that cooled to 923 K and then quenched in liquid-nitrogen. To obtain Yb0.25Co4Sb12-4 wt% (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x composites (which will be denoted by matrix-100x hereafter), the Yb0.25Co4Sb12 ingot was pulverized manually in an agate mortar, and the (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x ingot was milled in a planetary mill at 400 rmp for 5 h in vacuum. The Yb0.25Co4Sb12 coarse grains and (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x particles were then mixed in a planetary mill at 300 rpm for 40 min in vacuum, and finally hot pressed into circular pellets at 873 K and 100 MPa for 2 h in argon atmosphere.

Phase characterization was performed by powder X-ray diffraction (PANalytical X'pert PRO diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation). Scanning electron microscopy (FEI: Quanta 200, FEI: Sirion 200), and field–emission transmission electron microscopy (FEI: Tecnai G2 F30) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) were used to inspect the microstructure. For high temperature thermoelectric property measurements, the samples were cut by diamond saw into 8 × 8 × 2 mm3 square for the thermal conductivity measurement and 12 × 2 × 3 mm3 bar for the electrical resistivity and Seebeck coefficient measurements. All the TE property measurements were carried out from 300 to 773 K. The Seebeck coefficient-electrical resistivity measurements were performed simultaneously on an Ulvac-Riko ZEM-2 system. The thermal conductivity κ was calculated via the relation κ = DCd, where the thermal diffusivity D, specific heat C were measured on a laser-flash apparatus (Shinkuriko: TC-7000H) in vacuum. The density was obtained from the measured weight and dimensions. Room temperature Hall coefficient measurement was performed on a Hall effect measurement system (Ecopia: HMS 5500) via Van der Pauw method under an applied magnetic field of 0.55 T. The carrier concentration n and Hall mobility μH were estimated from the measured Hall coefficient RH and the electrical resistivity ρ via the relations, n = 1∕eRH and μH = RH∕ρ, where e is the electron charge.

Results and Discussion

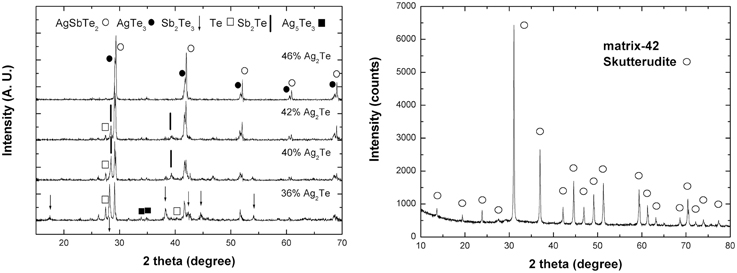

The powder X-ray diffraction pattern of Yb0.25Co4Sb12 agrees well with a skutterudite structure, with the calculated lattice parameter to be 9.0438(2) Å. The enlargement of the lattice parameter compared to CoSb3 (JCPDS: 03-065-3144, 9.0347 Å) is consistent with the Yb-filling scenario. The powder X-ray diffraction patterns of (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x ingots are shown in the left panel of Figure 1. As known, there is some disagreement in the literature about the pseudo-binary Ag2Te-Sb2Te3 slice of the Ag-Sb-Te phase diagram (Maier, 1963; Marin et al., 1985; Matsushita et al., 2004), indicating the phase complexity of this Ag-Sb-Te system. According to the pseudo-binary phase diagram, proposed by Marin et al. (1985), single-phase rock-salt structured AgSbTe2 falls in the range of x = 0.42–0.45 in (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x; when x > 0.45 Ag2Te forms in addition to the rock salt phase; and when x < 0.42 Sb2Te3 forms in addition to the rock salt phase. What we observed in the present work is somewhat different: the sample x = 0.46 is composed of rock-salt structured AgSbTe2 (JCPDS: 00-015-0540), rhombohedral AgTe3 (JCPDS: 01-076-2328), and barely discernible Ag5Te3 (JCPDS: 01-086-1168). It should be noted that the characteristic peaks of AgTe3 are very close to those of AgSbTe2. With decreasing x, the peak intensity of AgSbTe2 decreases while the characteristic peaks of single elemental Te and Sb-Te compound emerge. In the work reported by Wang et al. on (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x (x = 0.44-0.50) synthesized via mechanical alloying—spark plasma sintering process (Wang et al., 2008), Ag5Te3 emerged instead of Ag2Te in addition to the primary rock salt phase in (Ag2Te)0.48(Sb2Te3)0.52 and (Ag2Te)0.46(Sb2Te3)0.54. These results indicate that the phase components of ternary (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x system intimately depend on the synthesis process. Also shown in the right panel of Figure 1 is the XRD pattern of hot-pressed matrix-42 composite, and the other composites show similar results. The pattern indicates only the host matrix structure and no second phases associated with (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x are detected, which is ascribed to the low content as well as the peak broadening effect of nano-phases.

Figure 1. (Left) The powder X-ray diffraction patterns of Ag2xSb2−2xTe3−2x ingots; (Right) The X-ray diffraction pattern of hot-pressed matrix-42 composite.

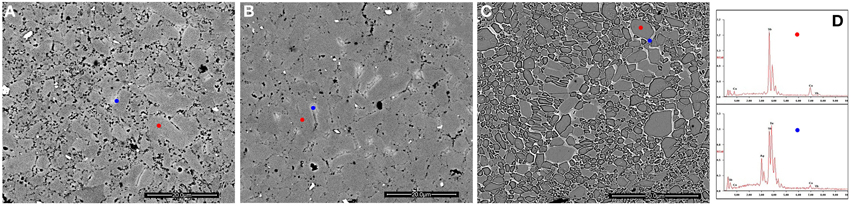

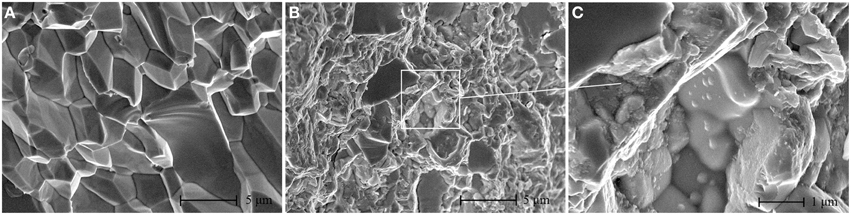

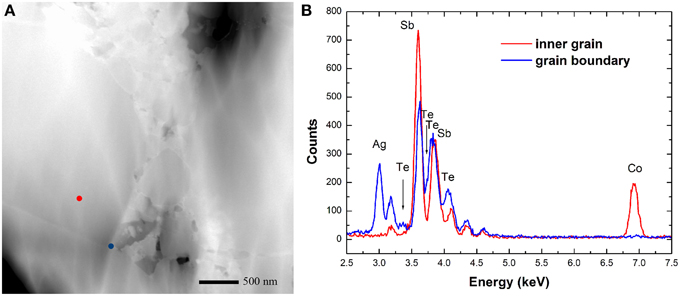

Mechanically polished and fractured surfaces were both prepared for microstructural analysis. Figure 2 shows the back scattered electron (BSE) SEM images and EDS result of the polished samples. The secondary phases show different contrast with the matrix, as verified by EDS result, and are distributed on the grain boundaries of Yb0.25Co4Sb12 host matrix. The calculated average grain size of the host matrix by line transection method is 3 μm, consistent with the result obtained on the laser particle size analyzer. Figure 3 presents some representative fractured surface SEM images. The micro-morphology of the composites is different from that of the matrix especially on the grain boundary. A high-magnification image in Figure 3C shows nanoparticles with size of about 200 nm distributed on the grain boundaries. Furthermore, TEM observations and EDS analysis were performed on the sample matrix-42. No Ag or Te were detected inside the coarse grain but were rich on the grain boundaries (Figure 4).

Figure 2. (A) BSE image of polished matrix-42 composite; (B) BSE image of polished matrix-40 composite; the red and blue points in (A,B) correspond to the host matrix and Ag-Sb-Te secondary phase respectively, as evidenced by EDS; (C) BSE image of polished and etched matrix-40 composite; (D) EDS results corresponding to the red and blue points in (C).

Figure 3. The fractured surface SEM images of the studied composites: (A) Yb0.25Co4Sb12 matrix; (B) matrix-40; (C) a high-magnification image of the marked range in (B).

Figure 4. (A) Bright-field TEM image of sample matrix-42 and (B) the EDS results corresponding to the red and blue points in (A).

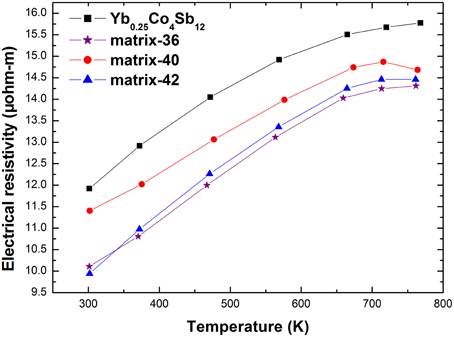

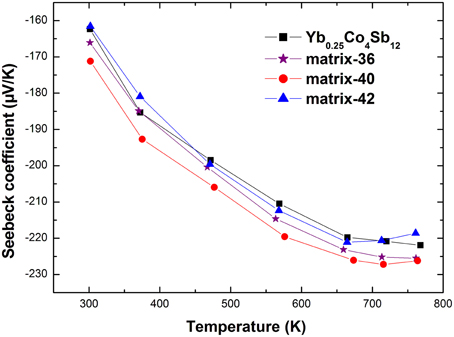

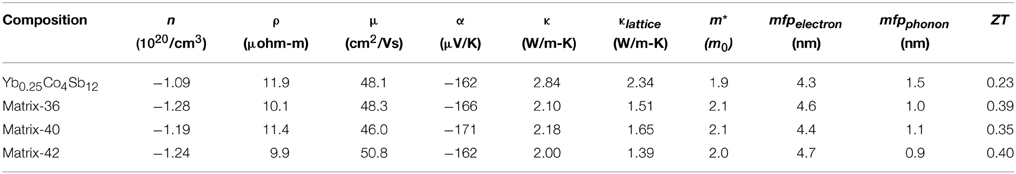

Figures 5, 6 present the electrical resistivity and the Seebeck coefficient of the samples from 300 to 773 K, respectively. Consistent with the previous reports (Fu et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2014), the electrical resistivity of the composites was lowered while the absolute Seebeck coefficient was enhanced upon the addition of Ag-Sb-Te second phases, which is hard to achieve in conventional single-phased bulk material. The electrical resistivity of all materials increases with increasing temperature until it reaches a maximum, typical of heavily-doped semiconductor. Table 1 lists some room temperature physical properties of the samples studied. The carrier concentration, n, of the composites is slightly increased in relative to that of the pristine sample, presumably due to Te from the (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x doping the Sb-site of the host matrix through diffusion in the hot pressing process. Notably, the carrier mobility μH is retained despite an increased n. This observation is somewhat unexpected because the carrier mobility is usually degraded upon nanocompositing since the interfaces scatter charge carriers (Clinger et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2012). In conjunction with the results of microstructure analysis, one possible scenario is that the Ag-Te-Sb second phases on the grain boundaries have improved the inter-grain electrical conductivity. Similar phenomena have been reported in Ba0.3Co4Sb12/Ag (Zhou et al., 2012) and also in our previously reported Yb0.2Co4Sb12-AgSbTe2 nanocomposites (Peng et al., 2014).

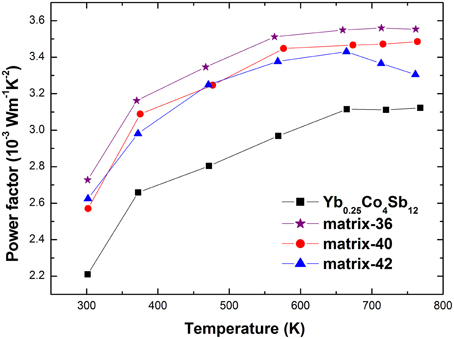

Another interesting observation is the increased absolute Seebeck coefficient. For a series of samples that possess the same scattering mechanism and approximately the same effective mass, the absolute Seebeck coefficient is expected to be inversely correlated with the carrier concentration (Ganguly et al., 2011). However, as shown in Figure 6 the absolute Seebeck coefficient is increased compared with the pristine sample despite of an increased carrier concentration. Since, Ag-Sb-Te phases are distributed on the grain boundaries of the host matrix, energy filtering mechanism is expected to contribute to the enhanced Seebeck coefficient which preferentially scatters the low energy charge carriers (Xu et al., 2010). In addition, the increment is less than in the Yb0.2Co4Sb12-AgSbTe2 system (Peng et al., 2014). For example, the absolute Seebeck coefficient of matrix-40 is increased to 171 μV/K as compared to 162 μV/K of Yb0.25Co4Sb12 at 300 K, while that of Yb0.2Co4Sb12-4wt% (Ag2Te)0.5(Sb2Te3)0.5 is increased to 202 μV/K as compared to 152 μV/K of Yb0.2Co4Sb12 (Peng et al., 2014). This is ascribed to the different structure component of Ag-Sb-Te inclusion due to Ag/Sb ratio variation. Considering the structure component of Ag-Sb-Te inclusion is different from the pseudo-binary Ag2Te-Sb2Te3 phase diagram, further investigation of the synthesis process may be required to obtain the phase diagram consistent structure component. The lowered electrical resistivity in addition to the increased absolute Seebeck coefficient gives rise to an enhancement of the power factor (Figure 7).

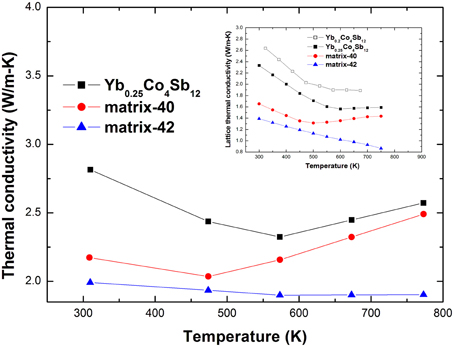

Figure 8 presents the κ and κL of the studied materials from 300 to 773 K. The κL is estimated by subtracting the κe from the κ using the Wiedemann–Franz relation κe = L0T∕ρ, with the Lorentz constant given by L0 = 2 × 10−8 V2K−2, which is suitable for heavily doped semiconductors (Goldsmid, 1986). The κ and κL were decreased systematically upon the addition of Ag-Sb-Te inclusions, and the κL decrease was more significant than that of Yb0.2Co4Sb12-AgSbTe2 system (Peng et al., 2014). For example, κL of matrix-42 shows a 39% decrease compared with Yb0.25Co4Sb12 matrix at 300 K, while that of Yb0.2Co4Sb12-4wt% (Ag2Te)0.5(Sb2Te3)0.5 shows a 27% decrease compared with Yb0.2Co4Sb12 matrix (Peng et al., 2014). Since, the detailed interactions between heat-carrying phonons and interfaces can be complex and material dependent (Cahill et al., 2003; Medlin and Snyder, 2009), it appears that perhaps the most important material parameter underlying the lattice thermal conductivity reduction is the interfacial area per unit volume (interface density) (Dresselhaus et al., 2007). From the XRD results, it is known that the (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x series have complicated phase components, which will generally increase phase interface density and then decrease the κL. Similar phenomena had been observed in our previously investigated In0.2+xCo4Sb12+x composites, where the high interface density via the formation of InSb/Sb eutectic mixture on the grain boundaries considerably decreased the κL (Peng et al., 2012b).

Figure 8. High temperature thermal conductivity and lattice thermal conductivity of the studied materials, the lattice thermal conductivity of Yb0.2Co4Sb12 from literature (Fu et al., 2013) is present for comparison.

To help quantify the impact of Ag-Sb-Te nanoinclusions on the carrier mobility and the phonon scattering, the room temperature electron mean-free-path and phonon mean-free-path have been estimated. In degenerate semiconductors with a parabolic band and acoustic phonon scattering, the Seebeck coefficient (Jeffrey Snyder and Toberer, 2008), the carrier mobility and the electron mean-free-path can be expressed by:

Where κB, h, m*, τc, vth, and ln are the Boltzmann constant, the Planck constant, effective mass, relaxation time, average thermal velocity, and mean-free-path, respectively. Per Equation (1), the effective mass was estimated to be in the range of 1.9 to 2.1m0. Incorporating Equations (2) and (3) to (4), the electron mean-free-path was estimated and listed in Table 1. Furthermore, the phonon mean-free-path can be estimated by the following relation:

Where Cv, υs, lp are the constant volume heat capacity, sound velocity, and phonon mean-free-path, respectively. We choose υs = 3400m∕s from literature (Sales et al., 1997). The calculated phonon mean-free-path is listed in Table 1. It can be seen that the phonon mean-free-path decreases substantially while the electron counterpart slightly increases. Though the theoretical analysis of thermal conductivity (electronic conductivity) is difficult for nanocomposite with varying-size inclusions, since the wave length and mean-free-path for phonons (or electrons) at certain energy are unknown for most materials system (Liu et al., 2012), it is necessary to note a fundamental difference between the electrical and heat transport. While those electrons near the Fermi level contribute to the electrical transport, phonon modes in the entire Brillouin zone generally contribute to the heat transport. As such, a multiple length scale microstructure is generally beneficial to effectively scatter heat-carrying phonons over a wider wavelength range and also over a wide temperature range, while imposing less influence on electron transport. Even, when the average wavelength of heat-carrying phonons is getting shorter at elevated temperatures, in which case the short-range defects are more effective in scattering phonons, the presence of long-range defects such as nanoinclusions and interfaces is indispensable to effectively suppress the lattice thermal conductivity. In this context, the microstructure characteristic of the multi-phase nanocomposites distributed on the grain boundaries of micro-grained matrix in the studied composites allows for a greater tunability of {ρ, α, κ} as a group.

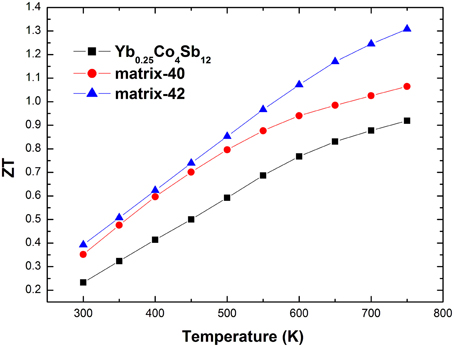

Finally, Figure 9 presents the dimensionless figure of merit ZT of the studied materials from 300 to 773 K. The ZT values of the composites are enhanced in the entire temperature range, due to the simultaneous enhancement of the power factor and the reduction of the κL. A maximum ZT of 1.3 was obtained in matrix-42 at 773 K, a 42% increase compared with that of the matrix.

Conclusions

Yb0.25Co4Sb12-4wt% (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x composites have been prepared via an ex situ melting-milling-hot-pressing process. The microstructure and high temperature thermoelectric properties have been investigated and correlated. Powder XRD analysis reveals the (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x series have complicated phase components, which closely depend on the conditions of synthesis process. In the composites, the Ag-Sb-Te inclusions are distributed on the grain boundaries of Yb0.25Co4Sb12 coarse grains. Compared to pristine sample, the electrical conductivity and absolute Seebeck coefficient of the composites are enhanced simultaneously. In the meantime the thermal conductivity and the lattice thermal conductivity are lowered substantially upon the addition of Ag-Sb-Te inclusions. Hence we have present a case study that multi-phase nanocomposites and complicated nanostructures formed by varying Ag2Te/Sb2Te3 ratios within (Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x materials allows for a greater tunability of {ρ, α, κ} as a group. A maximum ZT of 1.3 was obtained in matrix-42 at 773 K, a 42% increase compared with the pristine sample. The present work reveals that the three thermoelectric parameters can be optimized simultaneously in CoSb3-based nanocomposites. Further investigation to clarify the underlying mechanisms is ongoing.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work is co-supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51271084 and 51272080) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei province (2012FFB02215). The work at Clemson University is supported by National Science Foundation of the United States (DMR-1307740). The technical assistance from the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science & Technology is also gratefully acknowledged.

References

Ahn, K., Han, M. K., He, J. Q., Androulakis, J., Ballikaya, S., Uher, C., et al. (2010). Exploring resonance levels and nanostructuring in the PbTe-CdTe System and enhancement of the thermoelectric figure of merit. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5227. doi: 10.1021/ja910762q

Alam, H., and Ramakrishna, S. (2013). A review on the enhancement of figure of merit from bulk to nano-thermoelectric materials. Nano Energy 2, 190. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2012.10.005

Cahill, D. G., Ford, W. K., Goodson, K. E., Mahan, G. D., Majumdar, A., Maris, H. J., et al. (2003). Nanoscale thermal transport. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 793. doi: 10.1063/1.1524305

Carlton, C. E., Armas, R. D., Ma, J., May, A. F., Delaire, O., and Shao-Horn, Y. (2014). Natural nanostructure and superlattice nanodomains in AgSbTe2. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 144903. doi: 10.1063/1.4870576

Clinger, L. E., Pernot, G., and Buehl, T. E. (2012). Thermoelectric properties of epitaxial TbAs:InGaAs nanocomposites. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 094312. doi: 10.1063/1.4711095

Dresselhaus, M. S., Chen, G., Tang, M. Y., Yang, R., Lee, H., Wang, D., et al. (2007). New directions for low-dimensional thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mater. 19, 1043. doi: 10.1002/adma.200600527

Fan, S. F., Zhao, J. N., Yan, Q. Y., Ma, J., and Hng, H. H. (2011). Influence of nanoinclusions on thermoelectric properties of n-Type Bi2Te3 nanocomposites. J. Electron Mater. 40, 1018. doi: 10.1007/s11664-010-1487-7

Fu, L. W., Yang, J. Y., Xiao, Y., Peng, J. Y., Liu, M., Luo, Y. B., et al. (2013). AgSbTe2 nanoinclusion in Yb0.2Co4Sb12 for high performance thermoelectrics. Intermetallics 43, 79. doi: 10.1016/j.intermet.2013.07.009

Ganguly, S., Zhou, C., Morelli, D., Sakamoto, J., Uher, C., and Brock, S. L. (2011). Synthesis and evaluation of lead telluride/bismuth antimony telluride nanocomposites for thermoelectric applications. J. Solid State Chem. 184, 3195. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2011.09.031

Harman, T. C., Taylor, P. J., Walsh, M. P., and LaForge, B. E. (2002). Quantum dot superlattice thermoelectric materials and devices. Science 297, 2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1072886

Heremans, J. P., Jovovic, V., Toberer, E. S., Saramat, A., Kurosaki, K., Charoenphakdee, A., et al. (2008). Enhancement of thermoelectric efficiency in PbTe by distortion of the electronic density of states. Science 321, 554. doi: 10.1126/science.1159725

Heremans, J. P., Thrush, C. M., and Morelli, D. T. (2005). Thermopower enhancement in PbTe with Pb precipitates. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 063703. doi: 10.1063/1.2037209

Hsu, K. F., Loo, S., Guo, F., Chen, W., Dyck, J. S., Uher, C., et al. (2004). Cubic AgPbmSbTe2+m: bulk thermoelectric materials with high figure of merit. Science 303, 818. doi: 10.1126/science.1092963

Jeffrey Snyder, G., and Toberer, E. S. (2008). Complex thermoelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 7, 105. doi: 10.1038/nmat2090

Lee, K. H., Kim, H. S., Kim, S. I., Lee, E. S., Lee, S. M., Rhyee, J. S., et al. (2012). Enhancement of thermoelectric figure of merit for Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3 by metal nanoparticle decoration. J. Electron. Mater. 41, 1165. doi: 10.1007/s11664-012-1913-0

Liu, W. S., Yan, X., Chen, G., and Ren, Z. F. (2012). Recent advances in thermoelectric nanocomposites. Nano Energy 1, 42. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2011.10.001

Ma, J., Delaire, O., May, A. F., Carlton, C. E., McGuire, M., VanBebber, L. H., et al. (2013). Glass-like phonon scattering from a spontaneous nanostructure in AgSbTe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 445. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.95

Marin, R. M., Brun, G., and Tedenac, J. C. (1985). Phase equilibria in the Sb2Te3-Ag2Te system. J. Mater. Sci. 20, 730. doi: 10.1007/BF01026548

Matsushita, H., Hagiwara, E., and Katsui, A. (2004). Phase diagram and thermoelectric properties of Ag3−xSb1+xTe4 system. J. Mater. Sci. 39, 6299. doi: 10.1023/B:JMSC.0000043599.86325.ba

Medlin, D. L., and Snyder, G. J. (2009). Interfaces in bulk thermoelectric materials: a review for current opinion in colloid and interface science. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 14, 226. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2009.05.001

Morelli, D. T., Jovovic, V., and Heremans, J. P. (2008). Intrinsically minimal thermal conductivity in cubic I-V-VI2 semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 035901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.035901

Nielsen, M. D., Ozolins, V., and Heremans, J. P. (2013). Lone pair electrons minimize lattice thermal conductivity. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 570. doi: 10.1039/C2EE23391F

Peng, J. Y., Fu, L. W., Liu, Q. Z., Liu, M., Yang, J. Y., Hitchcock, D., et al. (2014). A study of Yb0.2Co4Sb12-AgSbTe2 nanocomposites: simultaneous enhancement of all three thermoelectric properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 73. doi: 10.1039/C3TA13729E

Peng, J. Y., Liu, X. Y., Fu, L. W., Xu, W., Liu, Q. Z., and Yang, J. Y. (2012b). Synthesis and thermoelectric properties of In0.2+xCo4Sb12+x composite. J. Alloys Comp. 521, 141. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.01.093

Peng, J. Y., Xu, W., Yan, Y. G., Yang, J. Y., Fu, L. W., Kang, H., et al. (2012a). Study on lattice dynamics of filled skutterudites InxYbyCo4Sb12. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 024909. doi: 10.1063/1.4739762

Poudel, B., Hao, Q., Ma, Y., Lan, Y. C., Minnich, A., Yu, B., et al. (2008). High-thermoelectric performance of nanostructured bismuth antimony telluride bulk alloys. Science 320, 634. doi: 10.1126/science.1156446

Rogl, G., Grytsiva, A., Rogl, P., Bauer, E., Hochenhofer, M., Anbalagan, R., et al. (2014). Nanostructuring of p- and n-type skutterudites reaching figures of merit of approximately 1.3 and 1.6, respectively. Acta Mater. 76, 434. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2014.05.051

Rosi, F. D., Hockings, E. F., and Lindenblad, N. E. (1961). Semiconducting materials for thermoelectric power generation. RCA Rev. 22, 82.

Sales, B. C., Mandrus, D., Chakoumakos, B. C., Keppens, V., and Thompson, J. R. (1997). Filled skutterudite antimonides: electron crystals and phonon glasses. Phys. Rev. B 56, 15081. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.56.15081

Shakouri, A., and Zebarjadi, M. (2009). “Nanoengineered materials for thermoelectric energy conversion,” in Thermal Nanosystems and Nanomaterials, Vol. 118, ed S. Volz (Berlin: Springer), 225.

Shi, X., Yang, J., Salvador, J. R., Chi, M. F., Cho, J. Y., Wang, H., et al. (2011). Multiple-filled skutterudites: high thermoelectric figure of merit through separately optimizing electrical and thermal transports. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 7837. doi: 10.1021/ja111199y

Venkatasubramanian, R., Siivola, E., Colpitts, T., and O'Quinn, B. (2001). Thin-film thermoelectric devices with high room-temperature figures of merit. Nature 413, 597. doi: 10.1038/35098012

Wang, H., Li, J. F., Zou, M. M., and Sui, T. (2008). Synthesis and transport property of AgSbTe2 as a promising thermoelectric compound. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 202106. doi: 10.1063/1.3029774

Xu, J. J., Li, H., Du, B. L., Tang, X. F., Zhang, Q. J., and Uher, C. (2010). High thermoelectric figure of merit and nanostructuring in bulk AgSbTe2. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 6138. doi: 10.1039/c0jm00138d

Yang, J., Zhang, W., Bai, S. Q., Mei, Z., and Chen, L. D. (2007). Dual-frequency resonant phonon scattering in BaxRyCo4Sb12 (R=La, Ce, and Sr). Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 192111. doi: 10.1063/1.2737422

Ye, L.-H., Hoang, K., Freeman, A. J., Mahanti, S. D., He, J., Kanatzidis, M. G., et al. (2008). First-principles study of the electronic, optical, and lattice vibrational properties of AgSbTe2. Phys. Rev. B 77:245203. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.77.245203

Yu, B., Zebarjadi, M., Wang, H., Lukas, K., Wang, H., Wang, D., et al. (2012). Enhancement of thermoelectric properties by modulation-doping in silicon germanium alloy nanocomposites. Nano Lett. 12, 2077. doi: 10.1021/nl3003045

Zebarjadi, M., Joshi, G., Zhu, G., Yu, B., Minnich, A., Lan, Y., et al. (2011). Power factor enhancement by modulation doping in bulk nanocomposites. Nano Lett. 11, 2225. doi: 10.1021/nl201206d

Zeng, G. H., Bahk, J. H., Bowers, J. E., Lu, H., Gossard, A. C., Singer, S. L., et al. (2009). Thermoelectric power generator module of 16×16 Bi2Te3 and 0.6% ErAs:(InGaAs)1−x(InAlAs)x segmented elements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 083503. doi: 10.1063/1.3213347

Zhang, S. N., Zhu, T. J., Yang, S. H., Yu, C., and Zhao, X. B. (2010a). Phase compositions, nanoscale microstructures and thermoelectric properties in Ag2−ySbyTe1+y alloys with precipitated Sb2Te3 plates. Acta Mater. 58, 4160. doi: 10.1016/j.actamat.2010.04.007

Zhang, S. N., Zhu, T. J., Yang, S. H., Yu, C., and Zhao, X. B. (2010b). Improved thermoelectric properties of AgSbTe2 based compounds with nanoscale Ag2Te in situ precipitates. J. Alloys Compd. 499, 215. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.03.170

Zhao, X. B., Ji, X. H., Zhang, Y. H., Zhu, T. J., Tu, J. P., Zhang, X. B., et al. (2005). Bismuth telluride nanotubes and the effects on the thermoelectric properties of nanotube-containing nanocomposites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 062111. doi: 10.1063/1.1863440

Keywords: thermoelectric, nanocomposite, skutterudite, AgSbTe2, figure of merit

Citation: Zheng J, Peng J, Zheng Z, Zhou M, Thompson E, Yang J and Xiao W (2015) Synthesis and high temperature thermoelectric properties of Yb0.25Co4Sb12-(Ag2Te)x(Sb2Te3)1−x nanocomposites. Front. Chem. 3:53. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2015.00053

Received: 17 July 2015; Accepted: 06 August 2015;

Published: 03 September 2015.

Edited by:

Chia-Jyi Liu, National Changhau University of Education, TaiwanCopyright © 2015 Zheng, Peng, Zheng, Zhou, Thompson, Yang and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiangying Peng, School of Mechanical Science & Engineering, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, 1037 Luoyu Road, Wuhan 430074, China,amlhbmd5aW5ncGVuZ0BtYWlsLmh1c3QuZWR1LmNu

Jin Zheng1

Jin Zheng1 Jiangying Peng

Jiangying Peng Emily Thompson

Emily Thompson