94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Cardiovasc. Med. , 24 March 2025

Sec. Cardioneurology

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1457899

Md. Moneruzzaman1,2,3,4

Md. Moneruzzaman1,2,3,4 Zhiqing Tang1,2

Zhiqing Tang1,2 Xiaohe Li4

Xiaohe Li4 Weizhen Sun4

Weizhen Sun4 Kellina Maduray5

Kellina Maduray5 Meiling Luo4

Meiling Luo4 Manzur Kader6

Manzur Kader6 Yonghui Wang4

Yonghui Wang4 Hao Zhang1,2,3*

Hao Zhang1,2,3*

Objectives: This systematic review aimed to evaluate the impact of post-stroke exercise-based rehabilitation programs on blood pressure, lipid profile, and exercise capacity.

Methods: Through a systemic search of literature from inception to 2024 using five databases, we analyzed data on the mean difference (MD) using a meta-analysis method to estimate effectiveness.

Results: Thirty-seven randomized control trials were included encompassing various exercises such as aerobic, resistance, stretching, exergaming, robot-assisted training, and community-based training. Significant improvement was illustrated at discharge in systolic [MD 2.76 mmHg; 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.58 to 3.92, P < 0.05] and diastolic (MD 1.28 mmHg; 95% CI 0.54–2.12, P < 0.05) blood pressure and peak oxygen volume (MD −0.29 ml/kg/min; 95% CI −0.53 to 0.05, P < 0.05). We also observed significant improvement at discharge in high-density lipoprotein only after resistance exercise from two articles and low-density lipoprotein only in the intervention groups compared to the control groups from ten articles.

Conclusion: Overall, current exercise-based rehabilitation programs significantly improve blood pressure and exercise capacity in patients with stroke at discharge. However, lipoprotein changes remained inconclusive. Although ameliorative changes were noted in most variables, more research is needed to determine optimum exercise intensity, type combination, and health education to reduce post-stroke complications and mortality.

Systematic Review Registration: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/X89FW.

After a stroke, 75% of patients develop cardiac diseases such as coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction (MI), atrial fibrillation (AF), heart failure (HF), and cardiac dysrhythmias (1–3). Schneck (4) stated that 19% of patients complained of heart problems just 3 months after a stroke, even though they had no history of heart disease. Several studies also illustrated that cardiovascular disease increased the risk of death after a cerebrovascular accident (4, 5). Among other cardiac cases, coronary stenosis (50%) and MI (3%) were more frequent after stroke (6). Moreover, ventricular arrhythmias, acute MI, HF, and cardiac death can be found among 4.1% of hospitalized patients with intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke, while it increases to 9% among subarachnoid hemorrhagic stroke patients (1). These post-stroke cardiac episodes are caused by stroke-induced heart damage, often known as stroke heart syndrome (7). Therefore, cardiac problems can also occur as a compensatory mechanism for stroke, known as neurogenic stress cardiomyopathy (NSC). Common manifestations of NSC are abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG) waves, ventricular wall abnormalities, and the release of troponin, a cardiac muscle regulator protein (8). Besides NSC, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is another factor that impairs psychological stress by weakening the heart muscle after a stroke (9). However, cardiac diseases can also develop due to long-term physical inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle (5).

Consequently, 20% of ischemic strokes occur due to several cardiac complications, making cardiac diseases the most common risk factor for stroke (7, 10). When other risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, are taken into account, people with AF increase their risk of stroke by approximately 5% (10). Moreover, recent studies indicate that approximately 25% of stroke patients without a prior history of AF may develop asymptomatic AF due to cardio-neurogenic mechanisms, increasing stroke recurrence risk and raising mortality by 60% (11). Fortunately, serial 12-lead ECG monitoring within the first month of post-stroke can significantly improve AF detection. However, focusing on persistent sinus rhythm and precise differentiation between AF and ventricular tachycardia are crucial to avoid further risk (12, 13). Evidence from a cohort study demonstrated that after rheumatoid heart disease, 5.2% of the patients had an incidence of stroke (14). Lackland and colleagues (15) found that cardiovascular risk factor prevention was one of the main reasons behind the decline of stroke mortality from third to fourth in the United States. Thus, cardiovascular risk factors prevention after a stroke event is inevitable.

Meanwhile, post-stroke rehabilitation comprises a variety of exercises (muscle strengthening and stretching, mobility training) and education (health education, personal grooming) to improve patients’ physical, cardiorespiratory, and cognitive performance (16, 17). Post-stroke blood pressure (BP), cardiac output (CO), heart rate (HR), and heart rate variability (HRV)—the fluctuation between two R waves—levels are essential to determine overall cardiac health and risk of stroke recurrence after rehabilitation (18, 19). Patients with depressed HVR have a lower performance rate, influencing overall recovery (20). A study on 103 subacute stroke patients found an adverse functional outcome following low HRV (18). Studies found that post-stroke cardiorespiratory fitness is not related to the factors causing stroke but to cardiovascular and pulmonary disease (21). The volume of oxygen peak (VO2peak), a measure of cardiorespiratory fitness, drops nearly 50% within a week of a stroke event compared to healthy individuals; although, stroke survivors’ often require a higher aerobic capacity to do routine work because of disability (22, 23). The walking ability of stroke survivors also declines due to low VO2peak (22).

Previous meta-analysis studies mainly focus on the impact of aerobic exercise on post-stroke peak oxygen uptake and walking distance; evidence on the effects of post-stroke rehabilitation on cardiac variables and lipid profile was less explored (23, 24). Some meta-analyses illustrated the impact of aerobic exercise on BP and cholesterol levels, but the overall findings were inconclusive due to methodological errors among included studies and outcome measures (20, 25). Furthermore, a meta-analysis conducted by Boulouis and colleagues (26) demonstrated that lowering blood pressure after intracerebral hemorrhage was safe but unrelated to patients’ functional outcomes, which debriefed the relation between functional outcomes and cardiac variables after stroke. However, the impact of all types of rehabilitation protocols in intra- and inter-groups and comparing baseline and post-intervention changes on blood pressure, lipid profile, and functional and exercise capacity may provide insight into post-stroke rehabilitation and suggest guidelines to reduce post-stroke complications and mortality.

Therefore, our study aimed to summarize the available evidence on the effect of post-stroke rehabilitation on BP, HR, and CO, lipid profile such as HDL, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by comparing post-treatment changes from baseline, as well as changes between control and intervention group. The primary outcomes of our study are BP, lipid profile variables, and exercise capacity (VO2peak), and the secondary outcome is functional capacity (walking).

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (27). The protocol of this review is registered and made public in the open science forum (OSF) platform (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/X89FW).

Following PICOS (28, 29) (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design) methodology, a search was conducted in five online databases (Web of Science, PubMed Central, PEDro, Cochrane Library, and Scopus) for studies that reported any of our study variables such as hemodynamic changes, physical function, and cardiorespiratory properties after post-stroke rehabilitation published from inception to June 2024. For PICOS, the population consisted of all patients participating in the post-stroke rehabilitation program. Interventions included any post-stroke rehabilitation program, including exercise and health education. Studies compared the intervention effects on any variables related to cardiovascular or cardiorespiratory and functional changes after the intervention, comparing baseline and post-intervention changes. The reported study outcomes were any of our study variables such as hemodynamics (BP, HR, and CO), lipid profile variables (HDL and LDL), exercise capacity measured by VO2peak, and functional capacity measured by the 6 min walk test (6MWT). The study design was a randomized control trial (RCT). There was no language restriction on search engines.

The following keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH), and an asterisk (*), to identify associated keywords were utilized for a wide range of search results, such as “Cardi*,” “rehab*,” “Cerebr*,” “Heart (MeSH),” “Brain (MeSH),” “Stroke (MeSH),” “Hemorrhagic (MeSH),” “Exercise (MeSH),” “training,” “ischemic,” “embolic,” “thrombotic,” and Boolean/phrase “AND” and “OR.” In addition, all relevant article reference lists, previous systematic reviews, and guidelines were screened for selection (shown in Supplementary File 1).

One author (MM) operated the search. Three authors (MM, LX-H, M-LL) screened all articles independently, limiting studies to the following inclusion criteria: (1) study subjects are from post-stroke rehabilitation, including both genders as participants; (2) studies wherein exercise or therapy or training program was performed (such as aerobic exercise, resistance training, community-based rehabilitation program, telerehabilitation, yoga, preventive education); (3) interventional studies, which evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention, with outcomes measured at baseline and post-intervention, with or without follow-up; (4) studies wherein outcome measurement was focused on hemodynamics, lipid profile, and functional and exercise capacity as a primary or secondary outcome, respectively. The exclusion criteria of studies were as follows: (1) studies on subjects having a stroke with other neurological commodities such as Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer's disease, cardiac disease and surgeries such as bypass surgery, and musculoskeletal or traumatic brain injury; (2) studies only focused on stroke without rehabilitation; (3) observational studies (e.g., cross-sectional association or correlation study), case reports, review articles, experimental or animal studies, abstracts, editors or experts’ opinions, and letters to editors; (4) unpublished study data or studies that failed to provide outcome data after contact with the author(s). Discussions with the supervising author (HZ) resolved any disputes regarding study selection.

We utilized reference manager software “Zotero” (30) and “Rayyan” (31) for study screening and finding duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened for primary selection, and full text and data availability were assessed for final study selection. The author (MM) contacted the respective authors for data availability. Any disagreement was solved through discussion.

For the quality of the study and the risk of bias assessment, two authors (MM and W-ZS) utilized “PEDro” (32) and the Cochrane Handbook for risk of bias assessment tool “ROB 2.0” (33). Regarding PEDro scores, studies were categorized as fair (>4), good (6–8), and excellent (9–10). The ROB 2.0 was assessed for the randomization process, deviation from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result and categorized as low risk, some concern, and high risk. The leave-one-out forest plot checked for any ambiguity in the study data.

Two authors (MM and KM) extracted all available data independently from included studies, including first author, year, country, sample size, age, gender, inclusion criteria of participants, type of stroke and disability, rehabilitation programs (such as aerobic exercise, balance training, upper and lower limb exercise, resistance training, health education), standard rehabilitation protocol, treatment duration and intensity, treatment outcomes [BP, CO, HR, HDL, LDL, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), FBG, VO2peak, time up and go (TUG), Berg balance score (BBS), 6MWT], follow-up, and summary of all findings (shown in Tables 1, 2).

We analyzed baseline and post-intervention effect data from included studies’ hemodynamic changes (BP, CO, HR), lipid profile (HDL, LDL, TC, TG), FBG, functional capacity (6MWT, TUG, BBS), and exercise capacity by VO2peak. We considered each rehabilitation program from a single study as a distinct entry for analysis; we validated the final results of each variable with changes at post-intervention of each study's control and intervention group illustrated by the study's author, followed by the published methodology (34). We used the random effects model of meta-analysis, converted standard error data to standard deviation, and estimated the mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We utilized the software “RevMan” (35) version 5.3 and STATA version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) for data analysis. We assessed heterogeneity by the I2 value (inconsiderable heterogeneity, I2 < 0%–30%) and the funnel plot to identify potential outliers (36).

A total of 9,484 articles were retrieved, and all duplicate articles were removed. A thorough screening of titles and abstracts excluded 4,855 articles, and 265 articles were assessed for eligibility through full-text analysis. Finally, 37 articles satisfied all the inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the overall search strategy (Figure 1), and the findings of all keywords from electronic databases were tabulated (Supplementary File 1). PRISMA checklist for the abstract, full text, and other information are available in Supplementary File 2.

The characteristics and rehabilitation programs of the included articles were compiled in Tables 1 and 2. The data from 37 trials (37–73), all intervention and control groups, were illustrated separately in Table 2. In total, 2,337 stroke patients [minimum age of (mean ± SD) 54 ± 8.98 years and a maximum of (mean ± SD) 74.7 ± 9.3 years] who participated in various rehabilitation programs (minimum duration of 4 weeks and maximum of 24 weeks). The inclusion criteria among articles on stroke incidence among included participants was a minimum of one week to a maximum of a year post-stroke. Ischemic stroke cases comprised 52.11% (n = 1,218) of all stroke events (Table 1). Moore et al. used the same subjects but reported different variables in two (45, 46) studies in different periods.

Additionally, sixteen articles (37, 38, 40, 41, 43, 44, 49, 53, 55, 57, 63–65, 67, 69, 72) investigated aerobic exercise (such as walking and cycling); six articles (40, 45, 48, 54, 59, 62) compared the effect of health education training; one article (50) included exergaming exercises; one article (70) involved robot-assisted walking training; and three articles (39, 42, 73) involved dynamic and resistance training. Exercise sessions lasted no more than 60 min, were performed three times/week, and were of varying intensity based on ratings of perceived exertion (14–16) and maximum heart rate (40%–95%). Exercise-based rehabilitation programs of all included articles are tabulated in Table 2.

All included articles were evaluated using the “PEDro” and the ROB 2.0 tool. According to the PEDro score, 26 articles (37–41, 45, 46, 48–50, 53–56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 65, 66, 68–73) scored between 6 and 8, which is considered significantly good quality, and the remaining articles were regarded as fair quality (Table 1). None of the articles was excluded due to low quality. Furthermore, only three articles (39, 55, 57) had a high risk, and nineteen articles (42, 46, 48, 49, 53–56, 58, 59, 61, 63, 65, 67–71, 73) had a low risk of bias according to the results of the ROB 2.0 tool. Some concerns were noted in other articles due to the selection of reported results and the randomization process (Supplementary File 3).

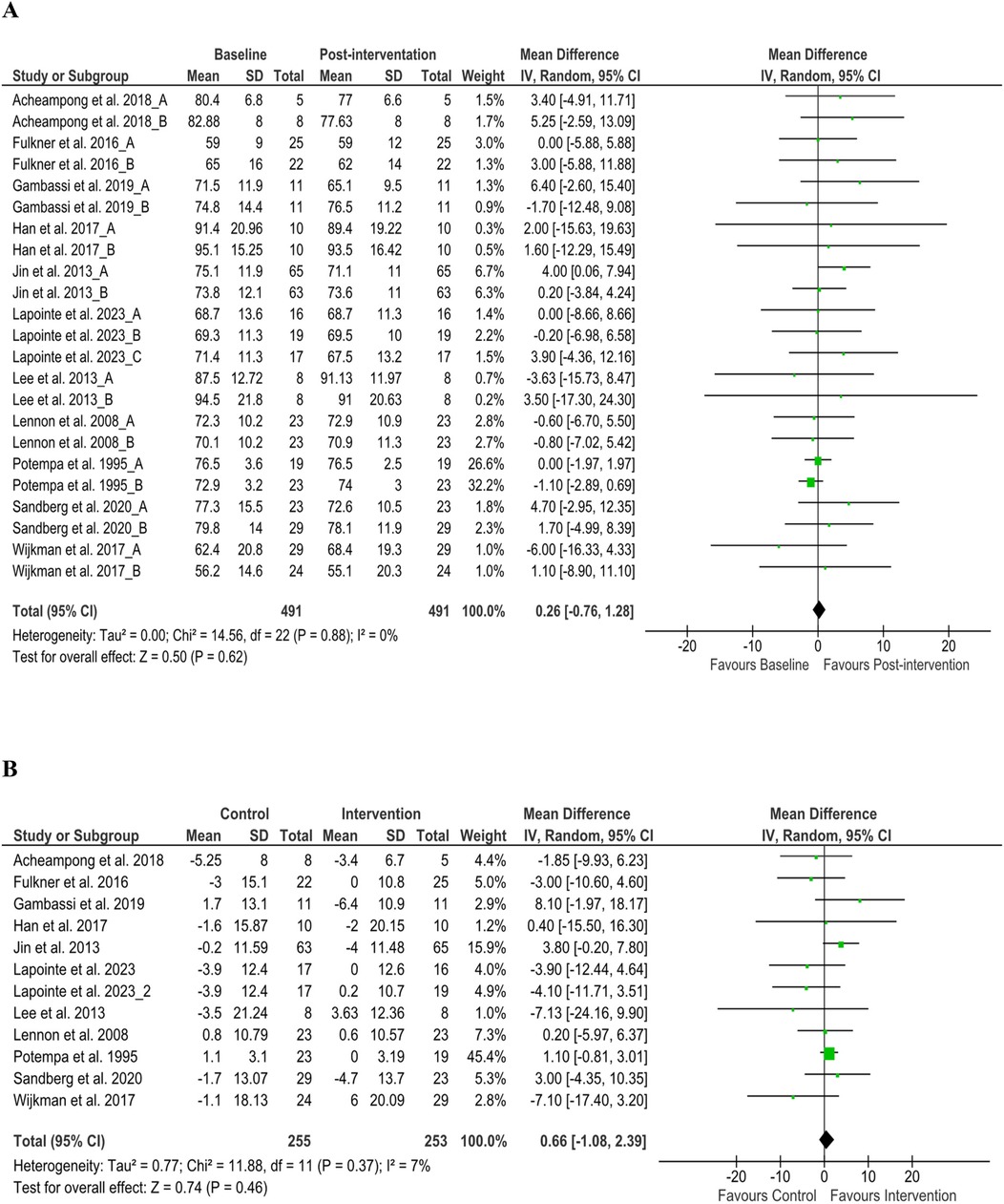

From 19 articles (37–40, 44, 45, 48, 52, 54, 57–62, 64, 68, 69, 72), we analyzed stroke patients’ SBP from baseline (number of patients, n = 1,146) and after discharge (n = 1,144). Cumulative results showed that the reduction of SBP after discharge was significant (MD 2.75 mmHg; 95% CI 1.58–3.92; P < 0.05, I2 = 0%), similar results were found in the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between control and intervention group (P < 0.05) (Figure 2), but the subgroup analysis of aerobic exercise, resistance training, and standard care from baseline to discharge shows insignificant reduction but tends to be positive effect (Supplementary File 4A). Notably, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) from baseline (n = 1,173) and after discharge (n = 1,168) from 18 articles (37–40, 44, 45, 48, 52, 54, 57–62, 68, 69, 72) showed significant declination (MD 1.28 mmHg; 95% CI 0.45–2.12 mmHg; P < 0.05, I2 = 0%), but in the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between control and intervention group, this improvement was insignificant (P > 0.05, I2 = 0%) as well as from all subgroup analysis (Supplementary File 4B). We analyzed stroke patients’ physiological variables (such as HR and CO) to find insightful explanations for these challenges. We found post-rehabilitation HR changes from eleven articles (38, 39, 44, 52, 56, 57, 60, 61, 64, 68, 72) (Figure 3) and CO changes from three articles (41, 45, 46) (Supplementary File 5) at discharge, and the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group was insignificant (P > 0.05) but ameliorative. However, concerning the positive impact of rehabilitation, our study recommends modification of post-stroke rehabilitation protocol in terms of exercise intensity, duration, and frequency to have a significant outcome.

Figure 2. Blood pressure changes (A) baseline to post-intervention and (B) difference in pre- and post-intervention at the control and intervention groups after post-stroke rehabilitation programs. SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval; df, degree of freedom.

Figure 3. Heart rate changes (A) baseline to post-intervention and (B) difference in pre- and post-intervention at the control and intervention groups after post-stroke rehabilitation programs. SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval; df, degree of freedom.

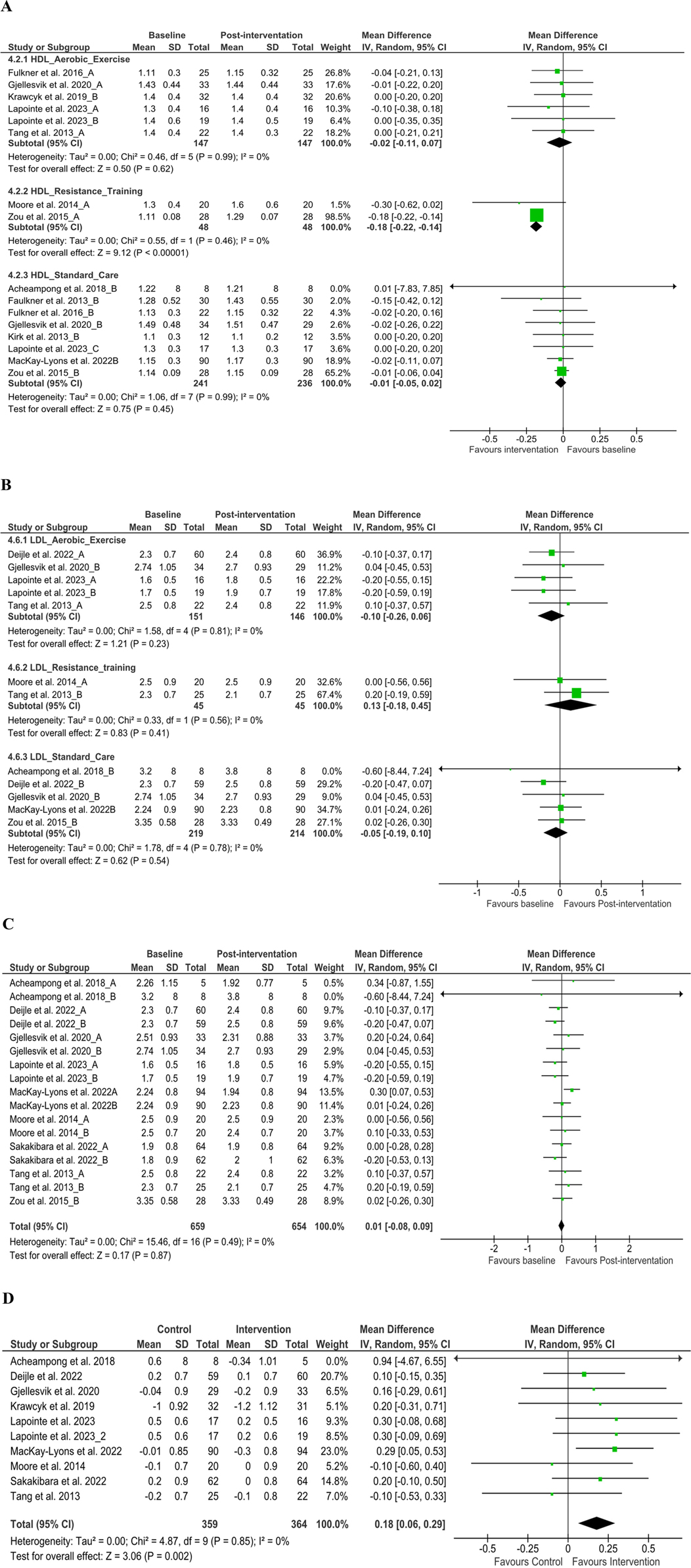

We analyzed HDL from 12 articles (38, 40, 44, 45, 48, 49, 52, 54, 58, 62, 69, 73) (n = 750) at discharge [MD −0.02 (95% CI −0.05 to 0.01), P > 0.05, I2 = 0%], and the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group [MD −0.04 (95% CI −0.10 to 0.02), P > 0.05, I2 = 0%] was insignificant (Supplementary File 6A). However, subgroup analysis at discharge on resistance training found significant changes [MD −0.18 (95% CI −0.22 to 0.14), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%] (Figure 4A). LDL from nine articles (37, 40, 44, 45, 48, 49, 52, 62, 73) (n = 659) at discharge [MD 0.01 (95% CI −0.08 to 0.09), P > 0.05, I2 = 0%] and subgroup analysis at discharge was insignificant (Figures 4B,C). Further, the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group found significant changes [MD 0.18 (95% CI 0.06–0.29), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%] (Figure 4D). These changes suggest that all intervention groups’ exercise may have had a higher impact due to the type of exercise combination than those of control groups at discharge, which requires further validation using cross-over control trial methods. TC from 10 articles (37, 38, 40, 45, 49, 52, 54, 58, 61, 73) (n = 491) found insignificant improvement at discharge and between groups (P > 0.05) (Supplementary File 7). Nonetheless, TG from six articles (37, 49, 52, 62, 69, 73) (n = 399) found significant improvement at discharge [MD 0.10 (95% CI 0.01–0.18), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%] (Supplementary File 8A). Furthermore, the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group found insignificant changes [MD 0.10 (95% CI −0.04 to 0.24), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%] (Supplementary File 8B).

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis from baseline to post-intervention changes. (A) High-density lipoprotein and (B) low-density lipoprotein, (C) low-density lipoprotein difference on baseline and post-intervention, (D) low-density lipoprotein changes in the control and intervention groups after post-stroke rehabilitation programs. SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval; df, degree of freedom.

Post-rehabilitation exercise capacity was assessed via VO2peak after exercise from nineteen articles (37, 40–42, 44, 45, 49, 53, 55, 56, 60–66, 70, 71) (n = 710) and found significant changes at discharge [MD −0.29 ml/kg/min (95% CI −0.53 to −0.05), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%], although insignificant changes only after health education (P > 0.05), but the inclusion of health education with standard care and exercise-based rehabilitation was found to have a positive effect. However, a significant improvement was found in the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group [MD −2.27 ml/kg/min (95% CI −3.01 to −1.54), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%] (Figure 5).

Figure 5. (A) VO2 changes baseline to post-intervention and (B) difference in pre- and post-intervention at the control and intervention groups. SD, standard deviation; IV, inverse variance; CI, confidence interval; df, degree of freedom.

Post-stroke rehabilitation significantly improved functional capacity measured in 6MWT from 12 articles (42, 43, 45, 49, 50, 53, 55–57, 60, 63, 66) (n = 448) and found significant changes at discharge [MD −27.15 m (95% CI −45.11 to −9.18), P < 0.05, I2 = 49%], but the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group found insignificant changes [MD −13.61 m (95% CI −39.95 to 12.73), P < 0.05, I2 = 31%] (Supplementary File 9). Furthermore, BBS (n = 123) improved significantly at discharge than baseline [MD −3.39 (95% CI −5.04 to −1.75), P < 0.05, I2 = 52%], as well as changes between control and intervention groups from one article (45) (n = 40) (P < 0.05) (Supplementary File 10). Contrarily, TUG (39, 46) (n = 62) test has an insignificant change after post-stroke rehabilitation at discharge [MD 1.76 (−0.49 to 4.01), P > 0.05, I2 = 0%] and the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention groups [MD 2.67 (−0.81 to 6.14), P > 0.05, I2 = 0%] (Supplementary File 11). These results suggest an overall deterioration in functional outcomes in different measures. In line with previous studies, our study also emphasizes that standardized and personalized measurement tools must be developed to prescribe exercise for people with stroke, concerning exercise principles such as specificity, overload, and reversibility for better outcomes (74).

Furthermore, FBG from seven articles (38, 48, 49, 54, 58, 62, 73) (n = 544) found significant changes at discharge [MD 0.15 (95% CI 0.04–0.26), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%] and the comparison of baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group [MD 0.17 (95% CI 0.03–0.30), P < 0.05, I2 = 0%] (Supplementary File 12). Moreover, homocysteine level changes from two articles (48, 49) (n = 87) found an insignificant (P > 0.05) improvement after the post-stroke rehabilitation program (Supplementary File 13).

We analyzed publication bias (75) using the funnel plot for variables, which included over ten studies; none of our results presented potential bias (shown in Supplementary Files 4, 6, 8, 10, 11). Sensitivity analysis (76) was done using the leave-one-out method. If any studies significantly impact overall results on any variables, we excluded that study from the analysis. Moreover, our findings suggest that all post-rehabilitation interventions enact no potential risk on outcomes.

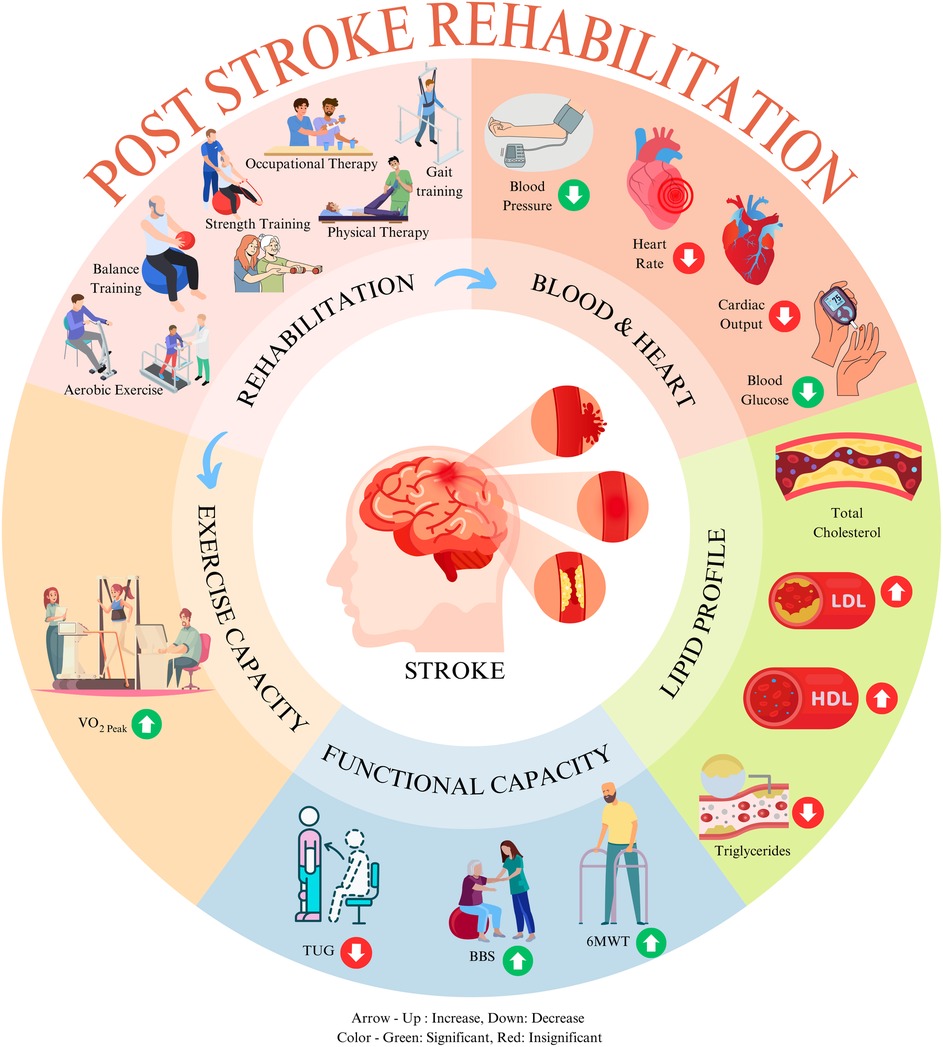

This systematic review and meta-analysis sought to evaluate the extent to which a rehabilitation program impacts cardiac health (BP, HR, and CO), lipid profile variables (HDL and LDL), exercise capacity (VO2peak), and functional capacity (6MWT) in patients after stroke. We included all RCTs that evaluated these changes among stroke survivors at any stage. Using the meta-analysis method, we analyzed the outcome data for the mean difference at discharge from baseline from all groups and changes (baseline to post-intervention) at discharge between control and intervention groups. The results of all variables at discharge are graphically presented in Figure 6. This result provides a comprehensive conclusion on the overall exercise-based rehabilitation programs practiced for patients with stroke. Notably, our study indicated that, whereas BP, functional, and exercise capacity improved significantly following rehabilitation programs, lipid level control was insignificant but ameliorative. These findings support modifying the post-stroke rehabilitation protocol and prioritizing cardiac health as a surrogate measure of rehabilitation outcome.

Figure 6. Effect of exercise-based rehabilitation among post-stroke patients at discharge. This image was created using elements from Canva, licensed under Free Content License.

BP reduction is vital to controlling stroke risk factors (26). Numerous pieces of evidence stated that >5.2 mmHg reduction of SBP can reduce the odds of having a recurrent stroke by up to 22% (77). Among combined exercise training groups, SBP and DBP reduction was significant. However, subgroup analysis showed an inconsistent effect, supporting both findings from a Cochrane review among 2,797 patients and a meta-analysis, which compared only aerobic exercise effects after rehabilitation and found an inconsistent effect on SBP and DBP (77, 78). Our analysis indicates that the underlying reason for this inconsistency could be the effect of exercise intensity. A recent RCT study emphasized that the intensity of training programs during stroke rehabilitation is pivotal to improving cardiac health and functional capacity (79). High-intensity treadmill training at a peak heart rate of 85%–95% (40) and high-intensity aerobic exercise training (brisk walking, cycling, marching) among 50 stroke patients showed significantly improved functional capacity (49). Nevertheless, growing evidence suggests that exercise intensity and exercise-induced fatigue burden patient recovery during rehabilitation (20).

HR is a precursory variable for assessing and reducing cardiovascular risk factors (80). After ischemic stroke, a higher HR at baseline correlated to higher cardiovascular risk and mortality (81). Mean HR increased to 10 beats/minute (bpm) from baseline (60 bpm), increasing the cardiovascular risk hazard ratio to approximately 0.39 (82, 83). Thirty-day mortality increases by 2.5% in ischemic stroke patients with atrial fibrillation for mean HR increases each one bpm over 80 bpm (81). HR and HRV changes occur inversely (84). Nozoe et al. illustrated that early mobilization after an ischemic stroke would cause neurological deterioration, which diverges the sympathetic nervous activity to affect HRV, identified by the fraction of low frequency and high frequency (19). In clinical practice, to identify and adjust the HRV to find the best possible training program for a stroke patient, a new training method called “the self-generate physiological coherence system” was designed based on the brain–heart interaction and pressure concept, demonstrating higher recovery and patient satisfaction (20). Our findings, backed by other studies, found that after a rehabilitation program, the resting HR of stroke patients decreased insignificantly (18, 80). These findings suggest that to develop a personalized rehabilitation program, one needs to focus on HRV and plan to decrease resting HR.

Furthermore, increased HDL reduces the risk of ischemic stroke (85). Conversely, an LDL level of <3.9 mmol/L after stroke can minimize cardiovascular risk (86). Our study is in line with previous findings that the reduction of LDL and TC and improvement of HDL are insignificant after post-stroke rehabilitation (25, 77). However, we found that after resistance exercise, HDL improvement was significant. Yang and colleagues (87) found a robust correlation between a decrease in total cholesterol/HDL ratio and an increase in VO2peak, although the level of evidence was reported as low. Our meta-analysis of four RCTs on post-stroke rehabilitation reported an improvement in VO2peak in comparing baseline and discharge changes between the control and intervention group in MD −2.97 ml/kg/min (95% CI −3.01 to −1.54). This finding is similar to two other meta-analyses, 1 of 13 RCTs in MD 2.53 ml/kg/min (95% CI 1.78–3.29) and another of 12 RCTs in MD 2.27 ml/kg/min (95% CI 1.58–2.95) on cardiorespiratory fitness in stroke patients’ after exercise (88, 89). Therefore, 1 ml/kg/min of VO2peak improvement reduces 15% of mortality risk among coronary artery patients (90). However, mortality risk after stroke increases by elevated HR rather than the level of VO2peak of patients with stroke (81). Furthermore, a Cochrane review stated that cardiorespiratory fitness training is feasible for the stroke population and improves walking capability and balance (78). Our findings also showed that stroke survivors covered significantly greater walking distances in 6MWT and BBS scores improved after rehabilitation.

Improving health-related knowledge among stroke patients can also improve their cardiac health (91). One of our included studies used an Android health application among 1,299 stroke patients to remind them about a healthy lifestyle through voice and text message services. Significant improvements in their cardiac health, such as BP and lipid profile, were found (51). A nurse-led health education study, including 268 patients, showed similar findings (47). Furthermore, In line with previous studies, specific exercise-based rehabilitation (aerobic, resistance) can sufficiently improve post-stroke blood pressure and functional or exercise capacity; yet, the improvement on some cardiac variables (HR, CO) or lipid profile variables (LDL, TC) is still inconclusive (55, 57, 64, 73). A growing number of RCT studies compared the effects of exercise-based rehabilitation with sham groups, while the intervention group exhibits a higher impact due to program design (55, 65, 72). To alleviate these, we recommend more cross-over randomized control trials on our study variables among post-stroke patients. However, answering the root cause of this decline is beyond our study objectives; more fundamental studies on the mechanism of NSC are recommended, as mentioned before. Thus, our study, in line with other meta-analyses, suggests that aerobic exercise has higher benefits than other exercise training and should be included as a fundamental exercise program for stroke survivors (23, 25).

Moreover, Stoller and colleagues (70) experimented with robot-assisted training and illustrated that the recommended intensity is not consistently achievable among stroke patients. Increasing exercise repetition might positively impact stroke patients’ exercise outcomes (92), which requires robust evidence from clinical studies. Some studies mentioned that the HRR was at a high-intensity level (70%–85%); the evidence is still disseminated to determine the optimal exercise intensity level for stroke patients (54–56, 62). Nonetheless, during follow-up, the impact of exercise was found to have a deterioration than at the discharge level (54, 62), which may hinder overall health among stroke survivors; practicing health education (40, 59, 62) and home-based (38, 48, 69) and community-based (42) exercise programs might be beneficial and improve post-stroke QoL and mortality.

Eventually, we recommend further studies in a large cohort in a randomized and cross-over control trial setting using modern technology such as a smartwatch and functional near-infrared spectroscopy to compare exercise with different intensities and repetition with health education with long-term follow-up to find the rehabilitation effects on cardiac health. A meta-analysis is required to find different exercises that impact blood pressure changes and report the risk of fatigue, syncope, and mortality rate.

Post-stroke rehabilitation intensely focused on the functional outcome rather than cardiac health, which led to the inclusion of fewer articles on our study topic. Our study selection criteria were not limited to treatment methods, intensity, or the stroke timeline, which generalizes our findings on rehabilitation practice. Due to data unavailability, we could not include all studies in all variables during the meta-analysis; a subgroup analysis on the time of stroke incidence and the impact of exercise was also unattainable. Considering the significance of hemodynamic changes among this population, we suggest that future research on the effect of post-stroke rehabilitation should report changes in the hemodynamic variables as reciprocal measures.

Our study revealed that current exercise-based rehabilitation programs significantly improve blood pressure and exercise capacity in patients with stroke at discharge. However, lipoprotein changes remained inconclusive. Although ameliorative changes were noted in most variables, more research is needed to determine optimum exercise intensity, type combination, and health education to reduce post-stroke complications and mortality.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZT: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. WS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Key Project of China Rehabilitation Research Center, grant number 2023ZX-02.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1457899/full#supplementary-material

1. Sposato LA, Hilz MJ, Aspberg S, Murthy SB, Bahit MC, Hsieh C-Y, et al. Post-stroke cardiovascular complications and neurogenic cardiac injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:2768–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.009

2. Towfighi A, Cheng EM, Ayala-Rivera M, McCreath H, Sanossian N, Dutta T, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a coordinated care intervention to improve risk factor control after stroke or transient ischemic attack in the safety net: secondary stroke prevention by uniting community and chronic care model teams early to end disparities (SUCCEED). BMC Neurol. (2017) 17:24. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0792-7

3. Roth EJ. Heart disease in patients with stroke: incidence, impact, and implications for rehabilitation part 1: classification and prevalence. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (1993) 74:752–60. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90038-C

4. Schneck MJ. Chapter 143—cardiac complications and ECG abnormalities after stroke. In: Caplan LR, Biller J, Leary MC, Lo EH, Thomas AJ, Yenari M, et al. editors. Primer on Cerebrovascular Diseases (Second Edition). San Diego: Academic Press (2017). p. 749–53.

5. Sjöholm A, Skarin M, Churilov L, Nilsson M, Bernhardt J, Lindén T. Sedentary behaviour and physical activity of people with stroke in rehabilitation hospitals. Stroke Res Treat. (2014) 2014:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2014/591897

6. Gunnoo T, Hasan N, Khan MS, Slark J, Bentley P, Sharma P. Quantifying the risk of heart disease following acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of over 50 000 participants. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e009535. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009535

7. Scheitz JF, Nolte CH, Doehner W, Hachinski V, Endres M. Stroke–heart syndrome: clinical presentation and underlying mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. (2018) 17:1109–20. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30336-3

8. Gopinath R, Ayya SS. Neurogenic stress cardiomyopathy: what do we need to know. Ann Card Anaesth. (2018) 21:228–34. doi: 10.4103/aca.ACA_176_17

9. Chen Z, Venkat P, Seyfried D, Chopp M, Yan T, Chen J. Brain-heart interaction: cardiac complications after stroke. Circ Res. (2017) 121:451–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311170

10. Escudero-Martínez I, Morales-Caba L, Segura T. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: a review and new insights. Trends Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 33(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2021.12.001

11. Sposato LA, Chaturvedi S, Hsieh C-Y, Morillo CA, Kamel H. Atrial fibrillation detected after stroke and transient ischemic attack: a novel clinical concept challenging current views. Stroke. (2022) 53:e94–103. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034777

12. Efremidis M, Vlachos K, Kyriakopoulou M, Mililis P, Martin CA, Bazoukis G, et al. The RV1-V3 transition ratio: a novel electrocardiographic criterion for the differentiation of right versus left outflow tract premature ventricular complexes. Heart Rhythm O2. (2021) 2:521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2021.07.009

13. Abdul-Rahim AH, Lees KR. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke: how should we hunt for it? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. (2013) 11:485–94. doi: 10.1586/erc.13.21

14. Vasconcelos M, Vasconcelos L, Ribeiro V, Campos C, Di-Flora F, Abreu L, et al. Incidence and predictors of stroke in patients with rheumatic heart disease. Heart. (2021) 107:748–54. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-318054

15. Lackland DT, Roccella EJ, Deutsch AF, Fornage M, George MG, Howard G, et al. Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke. (2014) 45:315–53. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000437068.30550.cf

16. Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery. Stroke. (2016) 47:e98–169. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098

17. Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, Eng JJ, Franklin BA, Johnson CM, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors. Stroke. (2014) 45:2532–53. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000022

18. Scherbakov N, Barkhudaryan A, Ebner N, von Haehling S, Anker SD, Joebges M, et al. Early rehabilitation after stroke: relationship between the heart rate variability and functional outcome. ESC Heart Fail. (2020) 7:2983–91. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12917

19. Nozoe M, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi M, Kanai M, Kubo H, Shimada S, et al. Heart rate variability during early mobilization in patients with acute ischemic stroke. ENE. (2018) 80:50–4. doi: 10.1159/000492794

20. Wang Y, Xiao G, Zeng Q, He M, Li F, Lin J, et al. Effects of focus training on heart rate variability in post-stroke fatigue patients. J Transl Med. (2022) 20:59. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03239-4

21. Boss HM, Van Schaik SM, Witkamp TD, Geerlings MI, Weinstein HC, Van den Berg-Vos RM. Cardiorespiratory fitness, cognition and brain structure after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. (2017) 12:724–31. doi: 10.1177/1747493017702666

22. Kelly JO, Kilbreath SL, Davis GM, Zeman B, Raymond J. Cardiorespiratory fitness and walking ability in subacute stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2003) 84:1780–5. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(03)00376-9

23. Stoller O, de Bruin ED, Knols RH, Hunt KJ. Effects of cardiovascular exercise early after stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. (2012) 12:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-45

24. Ghai S, Ghai I, Lamontagne A. Virtual reality training enhances gait poststroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2020) 1478:18–42. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14420

25. D'Isabella NT, Shkredova DA, Richardson JA, Tang A. Effects of exercise on cardiovascular risk factors following stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. (2017) 31:1561–72. doi: 10.1177/0269215517709051

26. Boulouis G, Morotti A, Goldstein JN, Charidimou A. Intensive blood pressure lowering in patients with acute intracerebral haemorrhage: clinical outcomes and haemorrhage expansion. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2017) 88:339–45. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315346

27. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

28. Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. (2014) 14:579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

29. Amir-Behghadami M, Janati A. Population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study (PICOS) design as a framework to formulate eligibility criteria in systematic reviews. Emerg Med J. (2020) 37:387–387. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209567

31. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

32. Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. (2003) 83:713–21. doi: 10.1093/ptj/83.8.713

33. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

34. Wang C, Redgrave J, Shafizadeh M, Majid A, Kilner K, Ali AN. Aerobic exercise interventions reduce blood pressure in patients after stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. (2019) 53:1515–25. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098903

36. Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. (2011) 343:d4002–d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002

37. Deijle IA, Hemmes R, Boss HM, De Melker EC, Van Den Berg BTJ, Kwakkel G, et al. Effect of an exercise intervention on global cognition after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke: the MoveIT randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. (2022) 22:289. doi: 10.1186/s12883-022-02805-z

38. Faulkner J, Tzeng Y-C, Lambrick D, Woolley B, Allan PD, O'Donnell T, et al. A randomized controlled trial to assess the central hemodynamic response to exercise in patients with transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke. J Hum Hypertens. (2017) 31:172–7. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2016.72

39. Gambassi BB, Coelho-Junior HJ, Paixão dos Santos C, de Oliveira Gonçalves I, Mostarda CT, Marzetti E, et al. Dynamic resistance training improves cardiac autonomic modulation and oxidative stress parameters in chronic stroke survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Oxid Med Cell Longevity. (2019) 2019:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2019/5382843

40. Gjellesvik TI, Becker F, Tjønna AE, Indredavik B, Nilsen H, Brurok B, et al. Effects of high-intensity interval training after stroke (the HIIT-stroke study): a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2020) 101:939–47. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.02.006

41. Hsu C-C, Fu T-C, Huang S-C, Chen CP-C, Wang J-S. Increased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor with high-intensity interval training in stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2021) 64:101385. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.03.010

42. Kang D, Park J, Eun S-D. The efficacy of community-based exercise programs on circulating irisin level, muscle strength, cardiorespiratory endurance, and body composition for ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. (2023) 14:1187666. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1187666

43. Kim J, Jun HP, Yim J. Effects of respiratory muscle and endurance training using an individualized training device on the pulmonary function and exercise capacity in stroke patients. Med Sci Monit. (2014) 20:2543–9. doi: 10.12659/MSM.891112

44. Lapointe T, Houle J, Sia YT, Payette M, Trudeau F. Addition of high-intensity interval training to a moderate intensity continuous training cardiovascular rehabilitation program after ischemic cerebrovascular disease: a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. (2023) 13:963950. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.963950

45. Moore SA, Hallsworth K, Jakovljevic DG, Blamire AM, He J, Ford GA, et al. Effects of community exercise therapy on metabolic, brain, physical, and cognitive function following stroke: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2015) 29:623–35. doi: 10.1177/1545968314562116

46. Moore SA, Jakovljevic DG, Ford GA, Rochester L, Trenell MI. Exercise induces peripheral muscle but not cardiac adaptations after stroke: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2016) 97:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.12.018

47. Olaiya MT, Cadilhac DA, Kim J, Ung D, Nelson MR, Srikanth VK, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to improve risk factor knowledge in patients with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. (2017) 48:1101–3. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016229

48. Sakakibara BM, Lear SA, Barr SI, Goldsmith CH, Schneeberg A, Silverberg ND, et al. Telehealth coaching to improve self-management for secondary prevention after stroke: a randomized controlled trial of stroke coach. Int J Stroke. (2022) 17:455–64. doi: 10.1177/17474930211017699

49. Tang A, Eng JJ, Krassioukov AV, Madden KM, Mohammadi A, Tsang MYC, et al. Exercise-induced changes in cardiovascular function after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Stroke. (2014) 9:883–9. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12156

50. Tollár J, Nagy F, Csutorás B, Prontvai N, Nagy Z, Török K, et al. High frequency and intensity rehabilitation in 641 subacute ischemic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2021) 102:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.07.012

51. Yan LL, Gong E, Gu W, Turner EL, Gallis JA, Zhou Y, et al. Effectiveness of a primary care-based integrated mobile health intervention for stroke management in rural China (SINEMA): a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. (2021) 18:e1003582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003582

52. Acheampong IK, Moses MO, Baffour-Awuah B, Essaw E, Mensah W, Afrifa D, et al. Effectiveness of combined and conventional exercise trainings on the biochemical responses of stroke patients. J Exerc Rehabil. (2018) 14:473–80. doi: 10.12965/jer.1836200.100

53. Aguiar LT, Nadeau S, Britto RR, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Martins JC, Samora GAR, et al. Effects of aerobic training on physical activity in people with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. NRE. (2020) 46:391–401. doi: 10.3233/NRE-193013

54. Faulkner J, Lambrick D, Woolley B, Stoner L, Wong L-K, McGonigal G. Effects of early exercise engagement on vascular risk in patients with transient ischemic attack and nondisabling stroke. Journal of Stroke & Cerebrovascular Diseases. (2013) 22(8):e388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.04.014

55. Globas C, Becker C, Cerny J, Lam JM, Lindemann U, Forrester LW, et al. Chronic stroke survivors benefit from high-intensity aerobic treadmill exercise: a randomized control trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2012) 26:85–95. doi: 10.1177/1545968311418675

56. Han EY, Im SH. Effects of a 6-week aquatic treadmill exercise program on cardiorespiratory fitness and walking endurance in subacute stroke patients: a PILOT TRIAL. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. (2018) 38:314–9. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000243

57. Jin H, Jiang Y, Wei Q, Chen L, Ma G. Effects of aerobic cycling training on cardiovascular fitness and heart rate recovery in patients with chronic stroke. NRE. (2013) 32:327–35. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130852

58. Kirk H, Kersten P, Crawford P, Keens A, Ashburn A, Conway J. The cardiac model of rehabilitation for reducing cardiovascular risk factors post transient ischaemic attack and stroke: a randomized controlled trial [with consumer summary]. Clin Rehabil. (2014) 28(4):339–49. doi: 10.1177/0269215513502211

59. Kono Y, Yamada S, Yamaguchi J, Hagiwara Y, Iritani N, Ishida S, et al. Secondary prevention of new vascular events with lifestyle intervention in patients with noncardioembolic mild ischemic stroke: a single-center randomized controlled trial. Cerebrovascular Diseases. (2013) 36(2):88–97. doi: 10.1159/000352052

60. Lee SY, Kang S-Y, Im SH, Kim BR, Kim SM, Yoon HM, et al. The effects of assisted ergometer training with a functional electrical stimulation on exercise capacity and functional ability in subacute stroke patients. Ann Rehabil Med. (2013) 37:619. doi: 10.5535/arm.2013.37.5.619

61. Lennon O, Carey A, Gaffney N, Stephenson J, Blake C. A pilot randomized controlled trial to evaluate the benefit of the cardiac rehabilitation paradigm for the non-acute ischaemic stroke population [with consumer summary]. Clin Rehabil. (2008) 22(2):125–33. doi: 10.1177/0269215507081580

62. MacKay-Lyons M, Gubitz G, Phillips S, Giacomantonio N, Firth W, Thompson K, et al. Program of rehabilitative exercise and education to avert vascular events after non-disabling stroke or transient ischemic attack (PREVENT trial): a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2022) 36:119–30. doi: 10.1177/15459683211060345

63. Macko RF, Ivey FM, Forrester LW, Hanley D, Sorkin JD, Katzel LI, et al. Treadmill exercise rehabilitation improves ambulatory function and cardiovascular fitness in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. (2005) 36:2206–11. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000181076.91805.89

64. Potempa K, Lopez M, Braun LT, Szidon JP, Fogg L, Tincknell T. Physiological outcomes of aerobic exercise training in hemiparetic stroke patients. Stroke. (1995) 26(1):101–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.26.1.101

65. Quaney BM, Boyd LA, McDowd JM, Zahner LH, Jianghua He, Mayo MS, et al. Aerobic exercise improves cognition and motor function poststroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2009) 23:879–85. doi: 10.1177/1545968309338193

66. Reynolds H, Steinfort S, Tillyard J, Ellis S, Hayes A, Hanson ED, et al. Feasibility and adherence to moderate intensity cardiovascular fitness training following stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol. (2021) 21:132. doi: 10.1186/s12883-021-02052-8

67. Ribeiro TS, Chaves Da Silva TC, Carlos R, De Souza E Silva EMG, Lacerda MO, Spaniol AP, et al. Is there influence of the load addition during treadmill training on cardiovascular parameters and gait performance in patients with stroke? A randomized clinical trial. NRE. (2017) 40:345–54. doi: 10.3233/NRE-161422

68. Sandberg K, Kleist M, Enthoven P, Wijkman M. Hemodynamic responses to in-bed cycle exercise in the acute phase after moderate to severe stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Hypertens. (2021) 23:1077–84. doi: 10.1111/jch.14232

69. Steen Krawcyk R, Vinther A, Petersen NC, Faber J, Iversen HK, Christensen T, et al. Effect of home-based high-intensity interval training in patients with lacunar stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol. (2019) 10:664. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00664

70. Stoller O, De Bruin ED, Schindelholz M, Schuster-Amft C, De Bie RA, Hunt KJ. Efficacy of feedback-controlled robotics-assisted treadmill exercise to improve cardiovascular fitness early after stroke: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Neurol Phys Ther. (2015) 39:156–65. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000095

71. Sutbeyaz ST, Koseoglu F, Inan L, Coskun O. Respiratory muscle training improves cardiopulmonary function and exercise tolerance in subjects with subacute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2010) 24:240–50. doi: 10.1177/0269215509358932

72. Wijkman MO, Sandberg K, Kleist M, Falk L, Enthoven P. The exaggerated blood pressure response to exercise in the sub-acute phase after stroke is not affected by aerobic exercise. J Clin Hypertens. (2018) 20:56–64. doi: 10.1111/jch.13157

73. Zou J, Wang Z, Qu Q, Wang L. Resistance training improves hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, highly prevalent among nonelderly, nondiabetic, chronically disabled stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2015) 96:1291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.008

74. Levy T, Laver K, Killington M, Lannin N, Crotty M. A systematic review of measures of adherence to physical exercise recommendations in people with stroke. Clin Rehabil. (2019) 33:535–45. doi: 10.1177/0269215518811903

75. Song F, Hooper L, Loke YK. Publication bias: what is it? How do we measure it? How do we avoid it? OAJCT. (2013) 71:71–81. doi: 10.2147/OAJCT.S34419

76. Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (2022). Available online at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

77. Brouwer R, Wondergem R, Otten C, Pisters MF. Effect of aerobic training on vascular and metabolic risk factors for recurrent stroke: a meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. (2021) 43:2084–91. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1692251

78. Saunders DH, Sanderson M, Hayes S, Kilrane M, Greig CA, Brazzelli M, et al. Physical fitness training for stroke patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2016) 3:CD003316. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003316.pub6

79. Rodrigues L, Moncion K, Eng JJ, Noguchi KS, Wiley E, de Las Heras B, et al. Intensity matters: protocol for a randomized controlled trial exercise intervention for individuals with chronic stroke. Trials. (2022) 23:442. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06359-w

80. Tang S, Xiong L, Fan Y, Mok VCT, Wong KS, Leung TW. Stroke outcome prediction by blood pressure variability, heart rate variability, and baroreflex sensitivity. Stroke. (2020) 51:1317–20. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027981

81. Yao S, Chen X, Liu J, Chen X, Zhou Y. Effect of mean heart rate on 30-day mortality in ischemic stroke with atrial fibrillation: data from the MIMIC-IV database. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:1017849. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1017849

82. Aboyans V, Criqui MH. Can we improve cardiovascular risk prediction beyond risk equations in the physician’s Office? J Clin Epidemiol. (2006) 59:547–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.11.002

83. Lee J-D, Kuo Y-W, Lee C-P, Huang Y-C, Lee M, Lee T-H. Initial in-hospital heart rate is associated with long-term survival in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Clin Res Cardiol. (2022) 111:651–62. doi: 10.1007/s00392-021-01953-5

84. Kazmi SZH, Zhang H, Aziz W, Monfredi O, Abbas SA, Shah SA, et al. Inverse correlation between heart rate variability and heart rate demonstrated by linear and nonlinear analysis. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0157557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157557

85. Sacco RL, Benson RT, Kargman DE, Boden-Albala B, Tuck C, Lin I-F, et al. High-Density lipoprotein cholesterol and ischemic stroke in the ElderlyThe northern Manhattan stroke study. JAMA. (2001) 285:2729–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2729

86. Amarenco P, Kim JS, Labreuche J, Charles H, Abtan J, Béjot Y, et al. A comparison of two LDL cholesterol targets after ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910355

87. Yang A-L, Lee S-D, Su C-T, Wang J-L, Lin K-L. Effects of exercise intervention on patients with stroke with prior coronary artery disease: aerobic capacity, functional ability, and lipid profile: a pilot study. J Rehabil Med. (2007) 39:88–90. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0021

88. Marsden DL, Dunn A, Callister R, Levi CR, Spratt NJ. Characteristics of exercise training interventions to improve cardiorespiratory fitness after stroke: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2013) 27:775–88. doi: 10.1177/1545968313496329

89. Luo L, Meng H, Wang Z, Zhu S, Yuan S, Wang Y, et al. Effect of high-intensity exercise on cardiorespiratory fitness in stroke survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 63:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.07.006

90. Keteyian SJ, Brawner CA, Savage PD, Ehrman JK, Schairer J, Divine G, et al. Peak aerobic capacity predicts prognosis in patients with coronary heart disease. Am Heart J. (2008) 156:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.03.017

91. Sanders K, Schnepel L, Smotherman C, Livingood W, Dodani S, Antonios N, et al. Assessing the impact of health literacy on education retention of stroke patients. Prev Chronic Dis. (2014) 11:E55. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130259

Keywords: stroke, exercise, blood pressure, lipid profile, neurocardiology

Citation: Moneruzzaman Md, Tang Z, Li X, Sun W, Maduray K, Luo M, Kader M, Wang Y and Zhang H (2025) Current exercise-based rehabilitation impacts on poststroke exercise capacity, blood pressure, and lipid control: a meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1457899. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1457899

Received: 1 July 2024; Accepted: 24 February 2025;

Published: 24 March 2025.

Edited by:

Carole Sudre, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Giuseppe Caminiti, Università telematica San Raffaele, ItalyCopyright: © 2025 Moneruzzaman, Tang, Li, Sun, Maduray, Luo, Kader, Wang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hao Zhang, Y3JyY3poMjAyMEAxNjMuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.