- 1Department of Biotechnology, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla, India

- 2B.N. College of Engineering and Technology, Lucknow, India

- 3Dr. Y. S. Parmar University of Horticulture and Forestry Nauni, Solan, India

Enzymes play vital roles in all organisms. The enzymatic process is progressively at its peak, mainly for producing biochemical products with a higher value. The immobilization of enzymes can sometimes tremendously improve the outcome of biocatalytic processes, making the product(s) relatively pure and economical. Carrier-free immobilized enzymes can increase the yield of the product and the stability of the enzyme in biocatalysis. Immobilized enzymes are easier to purify. Due to these varied advantages, researchers are tempted to explore carrier-free methods used for the immobilization of enzymes. In this review article, we have discussed various aspects of enzyme immobilization, approaches followed to design a process used for immobilization of an enzyme and the advantages and disadvantages of various common processes used for enzyme immobilization.

Introduction

Enzymes have been the most important part of our day-to-day life. Enzymes can regulate the biochemical and chemical reactions in the organisms as well as in situ biotransformations without being altered in the process (Palmer and Bonner, 2007). These biocatalysts are mostly used in the industries such as pharmaceutical and dairy industries for making food and dairy products, pharmaceutical industries for making medicines, textile industry for texture improvement, and paper and pulp industry (Watanabe et al., 1988; Sheldon and Woodley, 2018). To increase the use of enzymes on an industrial scale as biocatalysts (Zhang et al., 2012; Chapman et al., 2018), it is mandated that the enzyme system must be stable in a reaction system, the enzyme must possess improved operational stability in an aqueous or organic or biphasic system, stable biocatalytic potential, optimal requirement of raw materials, and more, so the enzyme selectivity and specificity should be high (Kricka and Thorpe, 1986). On top of a biocatalytic system, preferably, the enzyme system should be driven into a hygienic and cleaner industrial process.

The goal of enzyme immobilization is to create a strong biocatalyst that can operate under non-native and severe conditions for a longer period. Therefore, instead of using soluble enzyme counterparts, countless efforts have been committed for the improvement of enzyme immobilization techniques, optimizing their catalytic efficiency for a greater yield, stability, and reusability (Cao, 2005; Cao et al., 2021). For instance, it is recommendable to identify a suitable reusable matrix with a better selective absorbent, create a green recyclable process in order to improve the control of the catalysis process, and reduce the manufacturing cost of the desired product. Immobilized enzymes comprise two essential functional units irrespective of their methods of preparation or nature of the enzyme preparation: First, they possess a non-catalytic unit which is essential for their separation with the host environment, recycle process, and overall process management; Second, the functional catalytic unit which converts the substrate into a product (Cao, 2011; Dwevedi, 2016). Non-catalytic units comprise chemical and physical characteristics of the immobilized enzyme system, such as size, shape, and length of the chosen carrier, whereas the catalytic units are more similar to the chemical properties such as selectivity, pH, and activity (Cao et al., 2003). These are the criteria of choice when planning for the immobilization process of an enzyme. Carrier-free enzymes provide a cost-effective, simple, and straightforward method of reusing enzymes while also maintaining their catalytic efficiency and thermostability. This immobilization technology has been thoroughly evaluated upon numerous enzymes, and it has been successfully used in industrial processes (Velasco-Lozano et al., 2016). Thus, this review shows different aspects of enzyme immobilization and various approaches, along with the disadvantages and advantages of common processes used for enzyme immobilization.

Approach Toward Immobilization of Enzymes

Currently, the use of enzymes as a robust immobilized biocatalyst system(s) is experiencing a passage through crucial transition(s). This is supported by the fact that the strategies used for the layout of immobilized enzymes have come to be more and more rational; often, more complex and advanced immobilization strategies are utilized to overcome difficulties of older immobilization strategies involving only a particular immobilization methodology (Cao, 2011). In this context, this article tries not only to summarize the plenty of the artwork in enzyme immobilization techniques but also examines the fashion of improvement of biocatalyst efficacy, the aggregate of numerous immobilization methods, strategies, or disciplines, which have been previously successfully employed to attain the favored.

Immobilization of Enzymes and Old vs. New Strategies

During earlier times, the enzyme immobilization or in-solubilization process was synonymously used (Patel et al., 1969). The term “enzyme immobilization” refers to the physical confinement of the soluble proteinaceous enzyme molecules via different interactions to the carrier’s matrix in a region of space such as cross-linking/embedding, generally an insoluble material that can be easily removed from the medium, using simple basic procedures such as filtration, centrifugation, self-aggregation, or sieving (Mosbach, 1976). The characteristics of immobilized enzymes are largely governed by four important factors in an enzyme immobilization process, which are the nature and type of enzyme employed, the nature of the carrier, and the immobilization conditions (Datta et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2020).

To date, enzyme immobilization techniques have been extensively researched, with more than 6,000 publications and patents over it. Enzymes including amino acylase, PGA, invertase, many lipases, proteases, amylase, and nitrilase have been immobilized and are employed for diverse commercial processes (Heinen et al., 2017; Almeida et al., 2018; Facchini et al., 2018; Monteiro et al., 2019). Although the primary techniques of enzyme immobilization may be classified into some special techniques only, yet covalent bonding, adsorption, entrapment, encapsulation, and cross-linking are all examples of modifications that have been produced in the past, largely based on combinations of authentic techniques (Ahmad and Sardar, 2015). Similarly, numerous carriers of varied physical and chemical natures or occurrences have been developed for a wide range of bio-immobilization and bio-separation media. It is critical to remember that none of the existing immobilization methods can tackle the challenges that will be encountered in a certain process when building the best-suited immobilized enzyme for that process (Cao, 2011). Optimization and stabilization can be additionally carried out with the aid of a chemical change. One of the often used strategies to enhance the enzyme balance is hydrophilization of enzyme molecules through chemical change with hydrophilic practical polymers. The stabilization impact due to hydrophilization of a selected enzyme is manifested because of the creation of a positive hydrophilic microenvironment. The entrapment of the stabilized enzyme frequently results in the formation of an extra strong immobilized biocatalyst in comparison with an entrapped biocatalyst (Cao, 2005).

In the older case, the entrapped enzymes might be in addition subjected to chemical cross-linking to improve the balance or avoidance of enzyme leakage. Remarkably, a β-amylase obtained from Bacillus megaterium, immobilized in a bovine serum albumin gel matrix and covalently cross-connected depicted a 14-fold better thermostability than that of a native enzyme (Ray et al., 1994). Generally, the combination of techniques, including the pre-immobilization strategies, together with imprinting, chemical modification, cross-linking, etc., with the right immobilization method is decided as an essential immobilization technique (Cao, 2011).

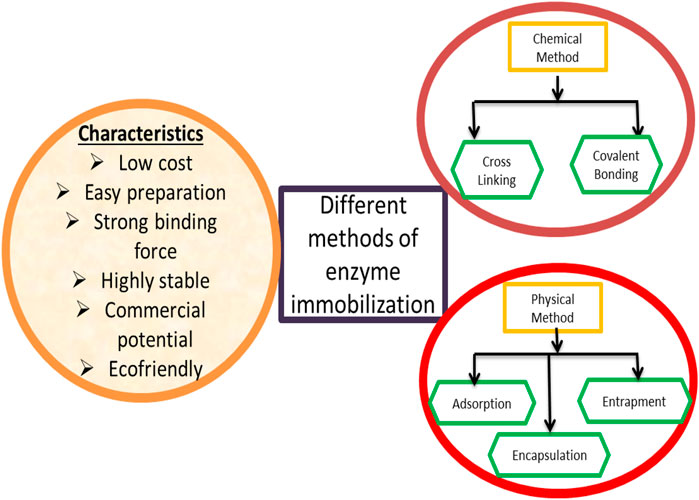

When designing an immobilized enzyme for any biological process, it is far critical to take note of the truth that the selection of the immobilization techniques is very important to get the desired results (Mohamad et al., 2015). The practical method would possibly be the usage of enzyme-immobilization methods, usually divided into numerous critical steps, and discrete optimization procedures of rational designs would possibly result in the introduction of strong and functional immobilized biocatalysts. A diagrammatic representation of the different methods of enzyme immobilization is summarized in Figure 1.

Classification of Immobilized-Enzymes

Immobilized enzymes have been classified into two major groups that are given as follows:

A) Carrier-bound immobilized enzymes: These are the enzymes that are physically or chemically bound to a matrix or support (i.e., carrier).

B) Carrier-free immobilized enzymes do not need supererogatory inactive mass. Carrier-free immobilized enzymes are normally constructed on the basis of their molecular mass via chemical cross-linking (Cao, 2011).

Need for Carrier-Free Immobilized Enzymes

In the past few decades, the use of an immobilized enzyme has become a major priority in industrial processes. The use of non-toxic, biodegradable, renewal, and commercially sustainable carrier-free immobilized enzymes and their physical or chemical property to fit in with its counterpart enzyme (or biocatalyst) makes it insoluble, aids during the separation process, and their continuous reusability in industrial or commercial processes (Sheldon, 2019; Ottone et al., 2020). Thompson et al. (2019a) have defined the parameters that an immobilized enzyme must satisfy in order to be commercially viable: easier recovery, more recyclability (∼above 20 cycles), stable during the reaction process, lower cost, tolerant to harsh solvents, minimum or no leaching, maximum activity recovery (∼above 50%), and maximum loading of the enzyme. Carrier-free immobilization as a cross-linked enzyme(s) and their derivatives is one way to do this. With a wide range of enzymes, particularly carbohydrate-converting enzymes, this technology is proved to be quite successful (Contesini et al., 2013).

The selection of good carriers gives clean control over the non-catalytic units of the acquired immobilized biocatalyst. The physical and the chemical nature of the carrier such as chemical composition, hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance, pore size, and binding chemistries dictates the performance of a carrier-bound immobilized enzyme (i.e., enzyme activity and stability) and a good carrier or suitable binding chemistry for an enzyme is not necessarily the right one for other enzymes or other applications (Sheldon, 2019). Thus, the nature of the selected carrier may be taken into consideration so as to modify the biocatalyst. Correspondingly, a high-quality quantity of artificial or organic/herbal carrier matrix, with unique shapes/sizes, porous/non-porous structures, and binding functionalities are particularly designed for diverse bio-immobilization and bio-separation procedures (Cao, 2011). Regardless of accelerated expertise on carrier-based enzyme immobilization, the layout of the carrier and certain immobilized enzymes nonetheless are based largely on rigorous screening procedures.

Major Types of Carrier-Free Immobilized Enzymes

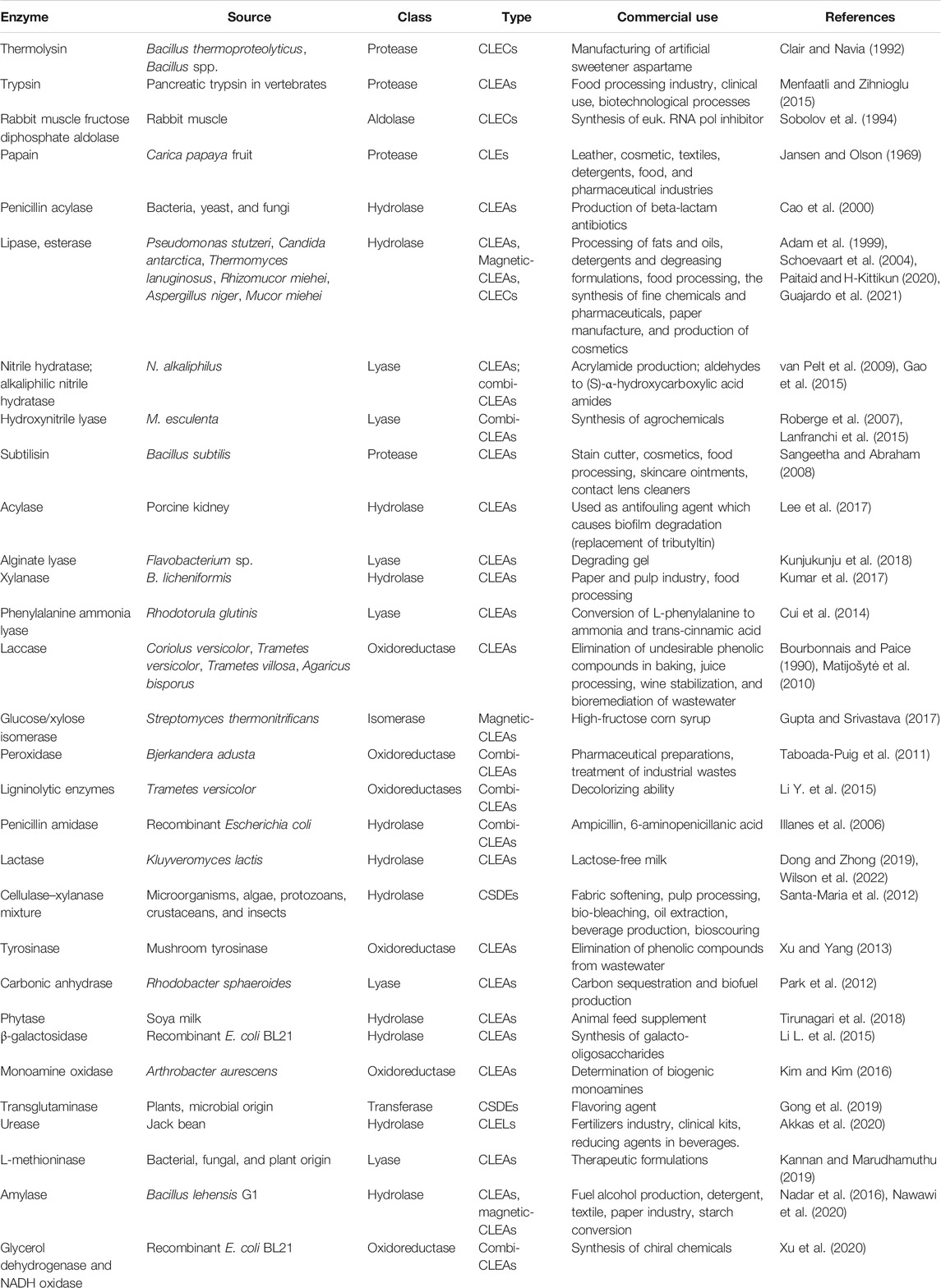

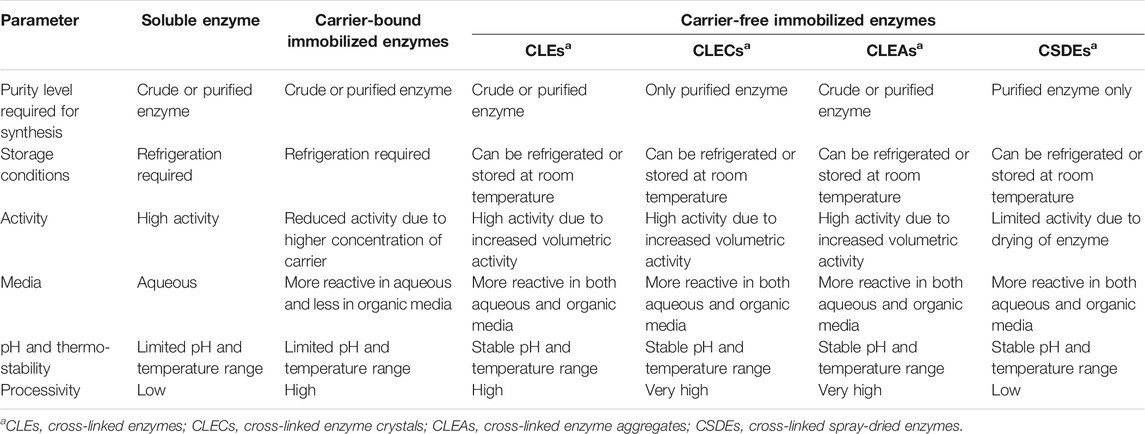

Carrier-free immobilized enzymes do not require additional inactive material or mass, that is, a carrier. At present, the following approaches have been devised for creating a carrier-free immobilized enzyme (Table 1), namely, cross-linked dissolved enzyme: CLEs; cross-linked enzyme crystals (CLECs); cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs); cross-linked enzyme lyophilizates (CLELs); and cross-linked spray-dried enzymes (CSDEs) (Wilson et al., 2004). Thus, utilizing various cross-linking precursors aids in distinguishing between different types of carrier-free immobilized enzymes.

TABLE 1. Comparison of different properties of soluble, carrier-bound immobilized, and carrier-free immobilized enzymes (Jegan Roy and Emilia Abraham, 2004; Cui et al., 2014; Voběrková et al., 2018).

The use of carriers in carrier-bound enzymes could decrease catalytic activity due to dilution of the enzyme due to the inclusion of more than 95 percent non-catalytic unit in the form of carrier (Roessl et al., 2010). For some applications, this might result in unacceptably reduced volumetric and space-time yields, as well as decreased catalyst efficiency. In contrast, carrier-free immobilized enzymes, particularly cross-linked enzyme aggregates and cross-linked enzyme crystals, perform well (DeSantis and Jones, 1999). As a result, significant research has been conducted to train these carrier-free immobilized enzymes, particularly CLEs. More than 20 different enzymes have been directly cross-connected to form many CLEs that were originally adsorbed on inert supports, including membranes cross-connected to shape supported CLEs (Cao, 2011).

Cross-linking Enzymes

A dissolved enzyme may be cross-linked to increase its thermostability; however, additional factors that may influence the stability of such biocatalysts include the amount of cross-linker, temperature, ionic strength, pH, and the amount of dissolved enzyme used (Taylor, 1985).

Despite many improvements, it is very difficult to optimize stronger mechanical balance via CLEs entrapment or dissolved enzyme cross-linking in a gel matrix (Manecke, 1972). The usage of greater mass glaringly decreased the volumetric interest to the extent of a service-sure immobilized enzyme. Consequently, in many biocatalytic studies, scientists switched to carrier-bound enzymes with an extensive variety of carriers. Thus, many companies particularly exploited advanced immobilization techniques (Mosbach, 1971), and numerous reactions for binding enzymes to carriers were established (Cui and Jia, 2015).

Cross-linking Enzymes Crystals

The remarkable discovery that is cross-linking of enzyme crystals of dissolved enzymes with a bifunctional chemical cross-linker, such as glutaraldehyde, could result in the formation of what we now refer to as insoluble CLECs, which was made in the early 1960s by researchers studying solid-phase protein chemistry by synthesizing compact cross-linked crystals of carboxypeptidase A (Quiocho and Richards, 1964). Following this work, a few other enzyme crystals were made using enzymes such as ribonuclease A, lysozyme (Manecke, 1972), subtilisin (Tüchsen and Ottesen, 1977, carboxypeptidase A (Quiocho and Richards, 1966), and alcohol dehydrogenase (Lee et al., 1986).

When compared to non-immobilized equivalents and standard carrier-bound immobilized enzymes (López–Serrano et al., 2002), their excellent stability under severe temperature and wider pH range in solvents made them an appealing prospective biocatalytic tools. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that CLECs could be designed in a reasonably short time because of no requirement of highly purified enzyme (Roessl et al., 2010). It was feasible to preserve comparable activity and selectivity relative to the soluble enzyme in an aqueous medium or relative to the crude enzyme in organic solvents by selecting the correct crystal shape or size or manipulating the crystallization characteristics of medium. The activity would also be affected by the size and characteristics of the substrates, the reaction media, the kind of reaction, and the reaction circumstances (Mehta et al., 2016). The biocatalytic activity could additionally depend upon the scale and residences of the substrates, the response medium, and response conditions (Cao et al., 1999). CLECs were formulated as strong and active immobilized enzymes of a controllable size. Several CLECs, particularly hydrolases consisting of acylases, proteases, and lipase, have been continuously used for chiral biocatalysis. Other uses of CLECs are microporous substances for controlled release of protein/peptide drugs, CLEC-based biosensor, lipase therapy for cystic fibrosis or pancreatitis, etc. (Jegan Roy and Emilia Abraham, 2004).

Cross-Linking Enzyme Aggregates

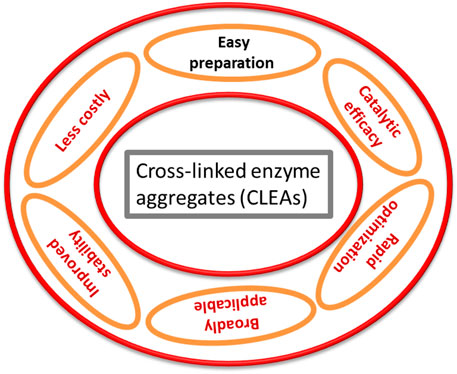

CLEAs have been introduced as one of most effective carrier-free immobilized enzyme systems (Figure 2), and the major advantage of this technique is that a tedious purification step is not required (Thompson et al., 2019b). By altering their properties that affect the proximity of soluble enzyme molecules, they can be used to shape bodily aggregates that, after cross-linking, termed as CLEAs (Cao et al., 2003; Table 2). When distributed in an aqueous media, these solid aggregates are kept together by non-covalent bonding and are easily collapsed and redissolved as a result of the non-covalent bonding. In the case of physical aggregates, chemical cross-linking would result in the formation of cross-linked enzyme aggregates, in which the restructured superstructure of the aggregates and their activity would be preserved (Nadar et al., 2016; Alves et al., 2021). This can partly explain why the enzyme could not consistently be cross-linked, even when 80% of overall lysine residues were changed through glutaraldehyde (Tomimatsu et al., 1971). Interestingly, it determined that the catalytic behavior of CLEAs differs because of the presence of the precipitants. In the case of CLEAs of penicillin G acylase produced through ammonium sulfate precipitation, the biocatalyst displayed similar behavior to the local enzyme for ampicillin synthesis, while CLEAs employed the use of test-butanol as a precipitant (Ling et al., 2016).

In most biological processes, more than one enzyme(s) are included, allowing them to maintain a high level of efficiency during metabolic and anabolic processes. In order to attain this aim during in vitro conditions, multiple-enzyme catalysis is preferred. Hence, combined cross-linked enzyme aggregates (combi-CLEAs) based on the CLEAs were designed and tested in the laboratory. Combi-CLEAs are enzyme complexes that include two or more immobilized enzymes that are capable of catalyzing sequential or simultaneous reactions in the same system (Sheldon, 2019).

Magnetic CLEA(s) of several enzymes has been synthesized by chemically cross-linking enzyme aggregates with magnetic nanoparticles, which can be isolated readily from the process mixture using a magnetic field (Sheldon, 2019). Moreover, wide-range thermostability increased buffering capacity, and varied pH has also been observed (Talekar et al., 2012).

Cross-Linked Enzyme Lyophilizates

The cross-linked enzyme lyophilizates are synthesized from freeze-dried/lyophilized enzyme preparation in presence of lyoprotectants (polymers/sugars) to minimize denaturation during the drying stages, and these lyophilizates are subjected to cross-linkers and precipitants. Organic compounds, carbohydrates, amino acids, etc. and their derivatives can be produced using CLELs through enzymatic processes such as reduction, esterification, and asymmetric conversion processes (Jegan Roy and Emilia Abraham, 2004).

Cross-Linked Spray-Dried Enzymes

Spray-dried enzyme powders are cross-linked to produce CSDEs. In addition, the fact that CSDEs are reversibly deactivated by the spray-drying process has prevented this technique from being widely used, even though it yielded respectable activity. Therefore, when compared to other carrier-free immobilization techniques, CSDEs have lower biocatalytic activity (Zicari et al., 2017).

Process Optimization of Carrier-Free Enzymes

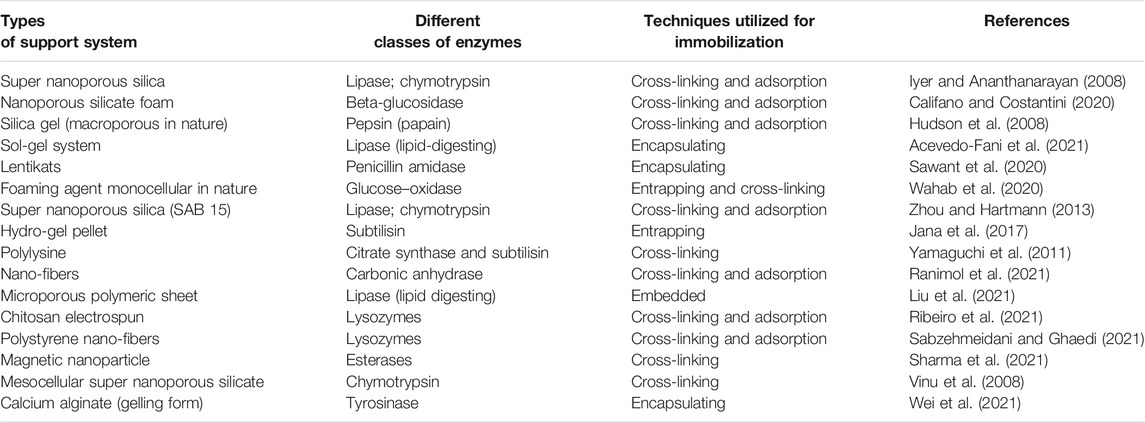

Immobilized enzyme preparations are effective biocatalysts for commercial manufacturing processes (Table 3). The introduction of carrier-free immobilized enzymes for process optimization has tackled major drawbacks of carrier bound immobilized enzymes by reducing the use of expensive carriers and increased catalytic mass with increased yield and reduced costs in the scale-up process (Cao et al., 2003). It is possible to achieve increased thermostability by cross-linking the dissolved enzyme (CLEs), but this needed a precise balance between numerous elements, including the quantity of cross-linkers used, temperature, pH, and ionic strength of the solution. Furthermore, intermolecular cross-linking of these highly solvated enzyme molecules often resulted in a number of undesirable side effects, including decreased activity retention, poor repeatability, and limited mechanical stability.

Cross-linked enzyme crystals (CLECs) were introduced by Quiocho and Richards (1964). When compared to CLEs, it was discovered that CLECs demonstrated improved thermostability, pH, more tolerance to organic solvents, and mechanical forces and showed higher retained activity. But one major drawback to CLECs was the requirement of high purified enzymes and their crystallization, which makes this process costlier. This limitation was overcome by a more promising, commercially utilized technique, that is, CLEAs (Sheldon, 2011). It is synthesized in two different phases: The initial step includes enzyme aggregation by precipitants using methods such as salting out with ammonium sulfate, organic solvents, isoelectric precipitation by TCA, using polyethylenimine, etc. which is then followed by the establishment of chemical linkages between the enzymes via cross-linking agents such as glutaraldehyde to further strengthen the interactions. The aggregation of proteins is exploited by rapid change of their hydration state by the addition of precipitants in the solvent solution. The development of precipitated enzyme aggregates is a necessary step in the preservation of enzyme activity during cross-linking (Arana-Peña et al., 2021). It has been observed that the catalytic activity of CLEAs varies based on the characteristics of the precipitants used in aggregation. In addition, spray drying is a reasonably affordable and readily scaled-up approach that is repeatable, making it a useful method of encapsulation technologies in industrial processes (Cui and Jia, 2015). At present, CSDEs have limited use in the industrial process but are still a robust and emerging technique. The objective is to provide a highly adaptable technological platform for screening and building strong carrier-free enzymes for a wide range of commercial applications.

Future Prospectus

In summary, the carrier-free immobilized enzyme technology has gained interest among researchers and engineers due to its commercial applicability in industrial processes. Many variants of cross-linked enzymes have proven their multiple applications, such as biotransformation processes, water treatment, antibiotic production, food processing, and several other potential applications. Another advantage in commercial use is their primary preference to replace toxic compounds in future chemical industries with more ecofriendly biocatalytic enzymes. Combi-CLEAs and magnetic CLEAs have proven to be more convenient in future production processes due to the presence of multiple catalysts in individual aggregates and easier separation.

Conclusion

Although the selected approach of immobilization may differ from enzyme to enzyme, carrier to carrier, and for a different application, primarily relying upon the peculiarities of every unique process, standards for measuring immobilized enzyme’s robustness remain the same. Commercially applied immobilized enzymes need to be relatively active, relatively selective (to lessen cross-reactions), relatively stable (to lessen value via way of means of efficient reuse), value-intensive (low-value contribution therefore economically viable), secure to use (to satisfy protection regulations), and definitely innovative. The productiveness of almost every immobilized enzyme is relatively lower than that of chemical processes. Due to diffusion constraints, activity retention for porous carriers is regularly underneath 50% at most enzyme loading in a biocatalytic reaction system. Although improvement of carrier-free enzymes, including CLEA or CLEC, can put off the use of the non-catalytic mass provider, the intrinsic drawbacks related to the carrier-free immobilized enzymes. The carrier-free biocatalytic systems appear to be greatly appealing as no scaffold/matrix is required, no matrix modification or activation is needed, little leaching effect is seen, and the complete absence of aldehyde cross-linking chemicals of the benefits of such biocatalytic systems. With the progressive research in the field, the future seems to be bright in creating advanced techniques to immobilize different enzymes, which would result in enhancing the efficiency of the enzyme by many folds.

Author Contributions

VC and DK: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, review, and editing. VivD: methodology, review, and editing. DS: drafting, methodology, conceptualization, review, and editing. VinD and HP: review and editing. SK: conceptualization, methodology, validation, review and editing, project administration, and supervision.

Funding

The study was financially supported by Council for Scientific & Industrial Research, New Delhi, under a CSIR-NET Senior Research Fellowship (File No.09/237(0161)/2017-EMR-1) to one of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors also acknowledge the use of equipment and services supported by UGC-SAP and DST-FIST grants to the Department of Biotechnology, Himachal Pradesh University, Shimla (India).

References

Acevedo-Fani, A., Guo, Q., Nasef, N., and Singh, H. (2021). “Aspects of Food Structure in Digestion and Bioavailability of LCn-3PUFA-Rich Lipids,” in Omega-3 Delivery Systems (Academic Press), 427–448. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-821391-9.00003-x

Adam, W., Lazarus, M., Saha-Möller, C. R., Weichold, O., Hoch, U., Häring, D., et al. (1999). Biotransformations with Peroxidases. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 63, 73–108. doi:10.1007/3-540-69791-8_4

Ahmad, R., and Sardar, M. (2015). Enzyme Immobilization: An Overview on Nanoparticles as Immobilization Matrix. Biochem. Anal. Biochem. 4 (2), 1. doi:10.4172/2161-1009.1000178

Akkas, T., Zakharyuta, A., Taralp, A., and Ow-Yang, C. W. (2020). Cross-Linked Enzyme Lyophilisates (CLELs) of Urease: A New Method to Immobilize Ureases. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 132, 109390. doi:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2019.109390

Almeida, P. Z., Messias, J. M., Pereira, M. G., Pinheiro, V. E., Monteiro, L. M. O., Heinen, P. R., et al. (2018). Mixture Design of Starchy Substrates Hydrolysis by an Immobilized Glucoamylase fromAspergillus Brasiliensis. Biocatal. Biotransform. 36 (5), 389395–395. doi:10.1080/10242422.2017.1423059

Alves, N. R., Pereira, M. M., Giordano, R. L. C., Tardioli, P. W., Lima, Á. S., Soares, C. M. F., et al. (2021). Design for Preparation of More Active Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of Burkholderia Cepacia Lipase Using palm Fiber Residue. Bioproc. Biosyst Eng. 44 (1), 57–66. doi:10.1007/s00449-020-02419-0

Arana-Peña, S., Carballares, D., Morellon-Sterlling, R., Berenguer-Murcia, Á., Alcántara, A. R., Rodrigues, R. C., and Fernandez-Lafuente, R. (2021). Enzyme Co-Immobilization: Always the Biocatalyst Designers’ Choice…or Not? 51. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107584

Bourbonnais, R., and Paice, M. G. (1990). Oxidation of Non-phenolic Substrates: An Expanded Role for Laccase in Lignin Biodegradation. Biotechnol. Adv. 267 (1), 107584–108102. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(90)80298-w

Califano, V., and Costantini, A. (2020). Immobilization of Cellulolytic Enzymes in Mesostructured Silica Materials. Catalysts 10 (6), 706. doi:10.3390/catal10060706

Cao, L. (2011). “Immobilized Enzymes,” in Immobilized Enzymes. Comprehensive Biotechnology. Editor M. Moo-Young. 2nd Edn. (Academic Press), 461–476. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-088504-9.00168-9

Cao, L. (2005). “Introduction: Immobilized Enzymes: Past, Present, and Prospects,” in Carrier-Bound immobilized enzymes: Principles, Application, and Design (Weinheim: Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA), 1–52.

Cao, L., Langen, L. v., and Sheldon, R. A. (2003). Immobilised Enzymes: Carrier-Bound or Carrier-free? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14 (4), 387–394. doi:10.1016/s0958-1669(03)00096-x

Cao, L., Van Langen, L., Janssen, M., and Sheldon, R. (1999). Preparation and Properties of Cross-Linked Aggregates of Penicillin Acylase and Other Enzymes. European Patent EP1088887A1. Munich, Germany: European Patent Office.

Cao, L., van Rantwijk, F., and Sheldon, R. A. (2000). Cross-linked Enzyme Aggregates: A Simple and Effective Method for the Immobilization of Penicillin Acylase. Org. Lett. 2 (10), 1361–1364. doi:10.1021/ol005593x

Cao, Y., Li, X., and Ge, J. (2021). Enzyme Catalyst Engineering toward the Integration of Biocatalysis and Chemocatalysis. Trends Biotechnol. 39 (11), 1173–1183. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2021.01.002

Chapman, J., Ismail, A., and Dinu, C. (2018). Industrial Applications of Enzymes: Recent Advances, Techniques, and Outlooks. Catalysts 8 (6), 238. doi:10.3390/catal8060238

Contesini, F., de Alencar Figueira, J., Kawaguti, H., de Barros Fernandes, P., de Oliveira Carvalho, P., da Graça Nascimento, M., et al. (2013). Potential Applications of Carbohydrases Immobilization in the Food Industry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (1), 1335–1369. doi:10.3390/ijms14011335

Cui, J. d., Cui, L. l., Zhang, S. p., Zhang, Y. f., Su, Z. g., and Ma, G. h. (2014). Hybrid Magnetic Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of Phenylalanine Ammonia Lyase from Rhodotorula Glutinis. PLoS One 9 (5), e97221. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097221

Cui, J. D., and Jia, S. R. (2015). Optimization Protocols and Improved Strategies of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates Technology: Current Development and Future Challenges. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 35 (1), 15–28. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.795516

Datta, S., Christena, L. R., and Rajaram, Y. R. S. (2013). Enzyme Immobilization: An Overview on Techniques and Support Materials. 3 Biotech. 3 (1), 1–9. doi:10.1007/s13205-012-0071-7

DeSantis, G., and Jones, J. B. (1999). Chemical Modification of Enzymes for Enhanced Functionality. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 10 (4), 324–330. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(99)80059-7

Dong, L., and Zhong, Q. (2019). Dispersible Biopolymer Particles Loaded with Lactase as a Potential Delivery System to Control Lactose Hydrolysis in Milk. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67 (23), 6559–6568. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01546

Dwevedi, A. (2016). Enzyme Immobilization: Advances in Industry, Agriculture, Medicine, and the Environment. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Facchini, F., Pereira, M., Vici, A., Filice, M., Pessela, B., Guisan, J., et al. (2018). Immobilization Effects on the Catalytic Properties of Two Fusarium Verticillioides Lipases: Stability, Hydrolysis, Transesterification and Enantioselectivity Improvement. Catalysts 8 (2), 84. doi:10.3390/catal8020084

Gao, J., Wang, Q., Jiang, Y., Gao, J., Liu, Z., Zhou, L., et al. (2015). Formation of Nitrile Hydratase Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates in Mesoporous Onion-like Silica: Preparation and Catalytic Properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54 (1), 83–90. doi:10.1021/ie503018m

Gong, P., Di, W., Yi, H., Sun, J., Zhang, L., and Han, X. (2019). Improved Viability of spray-dried Lactobacillus Bulgaricus sp1.1 Embedded in Acidic-Basic Proteins Treated with Transglutaminase. Food Chem. 281, 204–212. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.095

Guajardo, N., Ahumada, K., and Domínguez de María, P. (2021). Immobilization of Pseudomonas Stutzeri Lipase through Cross-Linking Aggregates (CLEA) for Reactions in Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Biotechnol. 337, 18–23. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2021.06.021

Gupta, A., and Srivastava, S. K. (2017). Study of Cross Linked Enzyme Aggregate of Glucose Isomerase of Streptomyces Thermonitrificans Immoblised on Magnetic Particle. J. Biochem. Technol. 7 (1), 1102–1106.

Heinen, P. R., Pereira, M. G., Rechia, C. G. V., Almeida, P. Z., Monteiro, L. M. O., Pasin, T. M., et al. (2017). Immobilized Endo-Xylanase of Aspergillus tamarii Kita: An Interesting Biological Tool for Production of Xylooligosaccharides at High Temperatures. Process Biochem. 53, 145–152. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2016.11.021

Hudson, S., Cooney, J., and Magner, E. (2008). Proteins in Mesoporous Silicates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (45), 8582–8594. doi:10.1002/anie.200705238

Illanes, A., Wilson, L., Caballero, E., Fernández-Lafuente, R., and Guisán, J. M. (2006). Crosslinked Penicillin Acylase Aggregates for Synthesis of β-Lactam Antibiotics in Organic Medium. Abab 133 (3), 189–202. doi:10.1385/ABAB:133:3:189

Iyer, P. V., and Ananthanarayan, L. (2008). Enzyme Stability and Stabilization-Aqueous and Non-aqueous Environment. Process Biochem. 43 (10), 1019–1032. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2008.06.004

Jana, S., Sen, K., Gandhi, A., Jana, S., and Roy, C. (2017). “Role of Alginate in Drug Delivery Applications,” in Industrial Applications of marine Biopolymers (Florida: CRC Press), 369–399. doi:10.1201/9781315313535-18

Jansen, E. F., and Olson, A. C. (1969). Properties and Enzymatic Activities of Papain Insolubilized with Glutaraldehyde. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 129 (1), 221–227. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(69)90169-6

Jegan Roy, J., and Emilia Abraham, T. (2004). September 8)Strategies in Making Cross-Linked Enzyme Crystals. Chem. Rev. 104 (9), 3705–3722. doi:10.1021/cr0204707

Kannan, S., and Marudhamuthu, M. (2019). Development of Chitin Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of L-Methioninase for Upgraded Activity, Permanence and Application as Efficient Therapeutic Formulations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 141, 218–231. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.246

Kim, Y.-J., and Kim, Y.-W. (2016). Optimizing the Preparation Conditions and Characterization of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of a Monoamine Oxidase. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 25 (5), 1421–1425. doi:10.1007/s10068-016-0221-5

Kricka, L. J., and Thorpe, G. H. G. (1986). Immobilized Enzymes in Analysis. Trends Biotechnol. 4 (10), 253–258. doi:10.1016/0167-7799(86)90188-5

Kumar, S., Haq, I., Prakash, J., and Raj, A. (2017). Improved Enzyme Properties upon Glutaraldehyde Cross-Linking of Alginate Entrapped Xylanase from Bacillus Licheniformis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 98, 24–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.104

Kunjukunju, S., Roy, A., Shekhar, S., and Kumta, P. N. (2018). Cross-linked Enzyme Aggregates of Alginate Lyase: A Systematic Engineered Approach to Controlled Degradation of Alginate Hydrogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 115, 176–184. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.110

Lanfranchi, E., Winkler, M., Pavkov-Keller, T., Köhler, E. M., Diepold, M., Darnhofer, B., et al. (2015). “Hydroxynitrile Lyase from Fern: A Unique Biocatalyst,” in 16th Austrian Chemistry Days 2015 (Innsbruck, Austria).

Lee, J., Lee, I., Nam, J., Hwang, D. S., Yeon, K.-M., and Kim, J. (2017). Immobilization and Stabilization of Acylase on Carboxylated Polyaniline Nanofibers for Highly Effective Antifouling Application via Quorum Quenching. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 9 (18), 15424–15432. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b01528

Lee, K. M., Blaghen, M., Samama, J.-P., and Biellmann, J.-F. (1986). Crosslinked Crystalline Horse Liver Alcohol Dehydrogenase as a Redox Catalyst: Activity and Stability toward Organic Solvent. Bioorg. Chem. 14 (2), 202–210. doi:10.1016/0045-2068(86)90031-3

Li, L., Li, G., Cao, L.-c., Ren, G.-h., Kong, W., Wang, S.-d., et al. (2015). Characterization of the Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of a Novel β-Galactosidase, a Potential Catalyst for the Synthesis of Galacto-Oligosaccharides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63 (3), 894–901. doi:10.1021/jf504473k

Li, Y., Wang, Z., Xu, X., and Jin, L. (2015). A Ca-Alginate Particle Co-immobilized with Phanerochaete Chrysosporium Cells and the Combined Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates from Trametes versicolor. Bioresour. Technol. 198, 464–469. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2015.09.032

Ling, X.-M., Wang, X.-Y., Ma, P., Yang, Y., Qin, J.-M., Zhang, X.-J., et al. (2016). Covalent Immobilization of Penicillin G Acylase onto Fe3O4@Chitosan Magnetic Nanoparticles. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26 (5), 829–836. doi:10.4014/jmb.1511.11052

Liu, J., Ma, R.-T., and Shi, Y.-P. (2020). “Recent Advances on Support Materials for Lipase Immobilization and Applicability as Biocatalysts in Inhibitors Screening Methods”-A Review. Analytica Chim. Acta 1101, 9–22. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2019.11.073

Liu, L.-H., Chiu, R.-Y., So, P. B., Lirio, S., Huang, H.-Y., Liu, W.-L., et al. (2021). Fragmented α-Amylase into Microporous Metal-Organic Frameworks as Bioreactors. Materials 14 (4), 870. doi:10.3390/ma14040870

López-Serrano, P., Cao, L., Van Rantwijk, F., and Sheldon, R. A. (2002). Cross-linked Enzyme Aggregates with Enhanced Activity: Application to Lipases. Biotechnol. Lett. 24 (16), 1379–1383. doi:10.1023/A:1019863314646

Manecke, G. (1972). “Immobilization of Enzymes by Various Synthetic Polymers,” in Biotechnology and Bioengineering Symposium (New York: John Wiley & Sons), Vol. 3.

Matijošytė, I., Arends, I. W. C. E., de Vries, S., and Sheldon, R. A. (2010). Preparation and Use of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) of Laccases. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 62 (2), 142–148. doi:10.1016/j.molcatb.2009.09.019

Mehta, J., Bhardwaj, N., Bhardwaj, S. K., Kim, K.-H., and Deep, A. (2016). Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization Techniques: Metal-Organic Frameworks as Novel Substrates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 322, 30–40. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2016.05.007

Menfaatli, E., and Zihnioglu, F. (2015). Carrier Free Immobilization and Characterization of Trypsin. Artif. Cell Nanomed. Biotechnol. 43 (2), 140–144. doi:10.3109/21691401.2013.853178

Mohamad, N. R., Marzuki, N. H. C., Buang, N. A., Huyop, F., and Wahab, R. A. (2015). An Overview of Technologies for Immobilization of Enzymes and Surface Analysis Techniques for Immobilized Enzymes. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 29 (2), 205–220. doi:10.1080/13102818.2015.1008192

Monteiro, L. M. O., Pereira, M. G., Vici, A. C., Heinen, P. R., Buckeridge, M. S., and Polizeli, M. d. L. T. d. M. (2019). Efficient Hydrolysis of Wine and Grape Juice Anthocyanins by Malbranchea Pulchella β-glucosidase Immobilized on MANAE-Agarose and ConA-Sepharose Supports. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 136, 1133–1141. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.106

Mosbach, K. (1976). Immobilised Enxymes. FEBS Lett. 62 (Suppl), E80–E94. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(76)80856-3

Mosbach, K. (1971). Enzymes Bound to Artificial Matrixes. Sci. Am. 224 (3), 26–33. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0371-26

Nadar, S. S., Muley, A. B., Ladole, M. R., and Joshi, P. U. (2016). Macromolecular Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (M-CLEAs) of α-amylase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 84, 69–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.11.082

Nawawi, N. N., Hashim, Z., Manas, N. H. A., Azelee, N. I. W., and Illias, R. M. (2020). A Porous-Cross Linked Enzyme Aggregates of Maltogenic Amylase from Bacillus Lehensis G1: Robust Biocatalyst with Improved Stability and Substrate Diffusion. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules 148, 1222–1231. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.101

Ottone, C., Romero, O., Aburto, C., Illanes, A., and Wilson, L. (2020). Biocatalysis in the Winemaking Industry: Challenges and Opportunities for Immobilized Enzymes. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 19 (2), 595–621. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12538

Paitaid, P., and H-Kittikun, A. (2020). Magnetic Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of Aspergillus oryzae ST11 Lipase Using Polyacrylonitrile Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Biodiesel Production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 190 (4), 1319–1332. doi:10.1007/s12010-019-03196-7

Palmer, T., and Bonner, P. L. (2007). Enzymes: Biochemistry, Biotechnology, Clinical Chemistry. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science.

Park, J.-M., Kim, M., Lee, H. J., Jang, A., Min, J., and Kim, Y.-H. (2012). Enhancing the Production of Rhodobacter Sphaeroides-Derived Physiologically Active Substances Using Carbonic Anhydrase-Immobilized Electrospun Nanofibers. Biomacromolecules 13 (11), 3780–3786. doi:10.1021/bm3012264

Patel, A. B., Pennington, S. N., and Brown, H. D. (1969). Insoluble Matrix-Supported Apyrase, Deoxyribonuclease and Cholinesterase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Enzymol. 178 (3), 626–629. doi:10.1016/0005-2744(69)90232-0

Quiocho, F. A., and Richards, F. M. (1964). Intermolecular Cross Linking of a Protein in the Crystalline State: Carboxypeptidase-A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 52, 833–839. doi:10.1073/pnas.52.3.833

Quiocho, F. A., and Richards, F. M. (1966). The Enzymic Behavior of Carboxypeptidase-A in the Solid State*. Biochemistry 5 (12), 4062–4076. doi:10.1021/bi00876a041

Ranimol, G., Paul, C., and Sunkar, S. (2021). Optimization and Efficacy Studies of Laccase Immobilized on Zein-Polyvinyl Pyrrolidone Nano Fibrous Membrane in Decolorization of Acid Red 1. Water Sci. Technol. 84 (10–11), 2703–2717. doi:10.2166/wst.2021.200

Ray, R. R., Jana, S. C., and Nanda, G. (1994). Biochemical Approaches of Increasing Thermostability of β-amylase fromBacillus megateriumB6. FEBS Lett. 356 (1), 30–32. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01227-x

Ribeiro, E. S., de Farias, B. S., Sant’Anna Cadaval Junior, T. R., de Almeida Pinto, L. A., and Diaz, P. S. (2021). Chitosan-based Nanofibers for Enzyme Immobilization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 183, 1959–1970. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.214

Roberge, C., Fleitz, F., Pollard, D., and Devine, P. (2007). Asymmetric Synthesis of Cyanohydrin Derived from Pyridine Aldehyde with Cross-Linked Aggregates of Hydroxynitrile Lyases. Tetrahedron Lett. 48 (8), 1473–1477. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.12.053

Roessl, U., Nahálka, J., and Nidetzky, B. (2010). Carrier-free Immobilized Enzymes for Biocatalysis. Biotechnol. Lett. 32 (3), 341–350. doi:10.1007/s10529-009-0173-4

Sabzehmeidani, M. M., and Ghaedi, M. (2021). “Adsorbents Based on Nanofibers,” in Interface Science and Technology (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science), 389–443. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818805-7.00005-9

Sangeetha, K., and Emilia Abraham, T. (2008). Preparation and Characterization of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEA) of Subtilisin for Controlled Release Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 43 (3), 314–319. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2008.07.001

Santa-Maria, M., Scher, H., and Jeoh, T. (2012). Microencapsulation of Bioactives in Cross-Linked Alginate Matrices by spray Drying. J. Microencapsul. 29 (3), 286–295. doi:10.3109/02652048.2011.651494

Sawant, A. M., Sunder, A. V., Vamkudoth, K. R., Ramasamy, S., and Pundle, A. (2020). Process Development for 6-aminopenicillanic Acid Production Using Lentikats-Encapsulated Escherichia coli Cells Expressing Penicillin V Acylase. ACS Omega 5 (45), 28972–28976. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c02813

Schoevaart, R., Wolbers, M. W., Golubovic, M., Ottens, M., Kieboom, A. P. G., Van Rantwijk, F., et al. (2004). Preparation, Optimization, and Structures of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 87 (6), 754–762. doi:10.1002/bit.20184

Sharma, D., Bhardwaj, K. K., and Gupta, R. (2021). Immobilization and Applications of Esterases. Biocatal. Biotransform., 1–16. doi:10.1080/10242422.2021.2013825

Sheldon, R. A. (2011). Cross-linked Enzyme Aggregates as Industrial Biocatalysts. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 15 (1), 213–223. doi:10.1021/op100289f

Sheldon, R. A., and Woodley, J. M. (2018). Role of Biocatalysis in Sustainable Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 118 (2), 801–838. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00203

Sheldon, R. (2019). CLEAs, Combi-CLEAs and 'Smart' Magnetic CLEAs: Biocatalysis in a Bio-Based Economy. Catalysts 9 (3), 261. doi:10.3390/catal9030261

Sobolov, S. B., Bartoszko-Malik, A., Oeschger, T. R., and Montelbano, M. M. (1994). Cross-linked Enzyme Crystals of Fructose Diphosphate Aldolase: Development as a Biocatalyst for Synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 35 (42), 7751–7754. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(94)80109-6

St. Clair, N. L., and Navia, M. A. (1992). Cross-linked Enzyme Crystals as Robust Biocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 (18), 7314–7316. doi:10.1021/ja00044a064

Taboada-Puig, R., Junghanns, C., Demarche, P., Moreira, M. T., Feijoo, G., Lema, J. M., et al. (2011). Combined Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates from Versatile Peroxidase and Glucose Oxidase: Production, Partial Characterization and Application for the Elimination of Endocrine Disruptors. Bioresour. Technol. 102 (11), 6593–6599. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.03.018

Talekar, S., Ghodake, V., Ghotage, T., Rathod, P., Deshmukh, P., Nadar, S., et al. (2012). Novel Magnetic Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (Magnetic CLEAs) of Alpha Amylase. Bioresour. Technol. 123, 542–547. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.044

Taylor, R. F. (1985). A Comparison of Various Commercially-Available Liquid Chromatographic Supports for Immobilization of Enzymes and Immunoglobulins. Analytica Chim. Acta 172, 241–248. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(00)82611-2

Thompson, M. P., Derrington, S. R., Heath, R. S., Porter, J. L., Mangas-Sanchez, J., Devine, P. N., et al. (2019a). A Generic Platform for the Immobilisation of Engineered Biocatalysts. Tetrahedron 75 (3), 327–334. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2018.12.004

Thompson, M. P., Peñafiel, I., Cosgrove, S. C., and Turner, N. J. (2019b). Biocatalysis Using Immobilized Enzymes in Continuous Flow for the Synthesis of fine Chemicals. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 23 (1), 9–18. doi:10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00305

Tirunagari, H., Basetty, S., Rode, H. B., and Fadnavis, N. W. (2018). Crosslinked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEA) of Phytase with Soymilk Proteins. J. Biotechnol. 282, 67–69. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.07.003

Tomimatsu, Y., Jansen, E. F., Gaffield, W., and Olson, A. C. (1971). Physical Chemical Observations on the α-chymotrypsin Glutaraldehyde System during Formation of an Insoluble Derivative. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 36 (1), 51–64. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(71)90239-6

Tüchsen, E., and Ottesen, M. (1977). Kinetic Properties of Subtilisin Type Carlsberg in the Crystalline State. Carlsberg Res. Commun. 42 (5), 407–420. doi:10.1007/BF02906125

van Pelt, S., van Rantwijk, F., and Sheldon, R. A. (2009). Synthesis of Aliphatic (S)-α-Hydroxycarboxylic Amides Using a One-Pot Bienzymatic Cascade of Immobilised Oxynitrilase and Nitrile Hydratase. Adv. Synth. Catal. 351 (3), 397–404. doi:10.1002/adsc.200800625

Velasco-Lozano, S., López-Gallego, F., Mateos-Díaz, J. C., and Favela-Torres, E. (2016). Cross-linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEA) in Enzyme Improvement - A Review. Biocatalysis 1 (1), 166–177. doi:10.1515/boca-2015-0012

Vinu, A., Gokulakrishnan, N., Mori, T., and Ariga, K. (2008). “Bio‐inorganic Hybrid Nanomaterials,” in Structured Materials. Bio-Inorganic Hybrid Nanomaterials: Strategies, Synthesis, Characterization and Applications. doi:10.1002/9783527621446

Voběrková, S., Solčány, V., Vršanská, M., and Adam, V. (2018). Immobilization of Ligninolytic Enzymes from white-rot Fungi in Cross-Linked Aggregates. Chemosphere 202, 694–707. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.088

Wahab, R. A., Elias, N., Abdullah, F., and Ghoshal, S. K. (2020). On the Taught New Tricks of Enzymes Immobilization: An All-Inclusive Overview. Reactive Funct. Polym. 152, 104613. doi:10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2020.104613

Watanabe, S., Shimizu, Y., Teramatsu, T., Murachi, T., and Hino, T. (1988). [48] Application of Immobilized Enzymes for Biomaterials Used in Surgery. Methods Enzymol. 137, 545–551. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(88)37050-3

Wei, C. M., Feng, C. Y., Li, S., Zou, Y., and Yang, Z. (2021). Mushroom Tyrosinase Immobilized in Metal-Organic Frameworks as an Excellent Catalyst for Both Catecholic Product Synthesis and Phenolic Wastewater Treatment. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. doi:10.1002/jctb.6984

Wilson, L., Illanes, A., Ottone, C., and Romero, O. (2022). Co-immobilized Carrier-free Enzymes for Lactose Upgrading. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 33, 100553. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100553

Wilson, L., Illanes, A., Pessela, B. C. C., Abian, O., Fernández-Lafuente, R., and Guisán, J. M. (2004). Encapsulation of Crosslinked Penicillin G Acylase Aggregates in Lentikats: Evaluation of a Novel Biocatalyst in Organic media. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86 (5), 558–562. doi:10.1002/bit.20107

Xu, D.-Y., and Yang, Z. (2013). Cross-linked Tyrosinase Aggregates for Elimination of Phenolic Compounds from Wastewater. Chemosphere 92 (4), 391–398. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.12.076

Xu, M.-Q., Li, F.-L., Yu, W.-Q., Li, R.-F., and Zhang, Y.-W. (2020). Combined Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of Glycerol Dehydrogenase and NADH Oxidase for High Efficiency In Situ NAD+ Regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 144, 1013–1021. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.178

Yamaguchi, H., Miyazaki, M., Asanomi, Y., and Maeda, H. (2011). Poly-lysine Supported Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates with Efficient Enzymatic Activity and High Operational Stability. Catal. Sci. Technol. 1 (7), 1256–1261. doi:10.1039/c1cy00084e

Zhang, B., Weng, Y., Xu, H., and Mao, Z. (2012). Enzyme Immobilization for Biodiesel Production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93 (1), 61–70. doi:10.1007/s00253-011-3672-x

Zhou, Z., and Hartmann, M. (2013). Progress in Enzyme Immobilization in Ordered Mesoporous Materials and Related Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (9), 3894–3912. doi:10.1039/c3cs60059a

Keywords: enzymes, immobilized enzymes, biocatalytic process, carrier-free immobilized enzymes, immobilization

Citation: Chauhan V, Kaushal D, Dhiman VK, Kanwar SS, Singh D, Dhiman VK and Pandey H (2022) An Insight in Developing Carrier-Free Immobilized Enzymes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10:794411. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.794411

Received: 13 October 2021; Accepted: 21 January 2022;

Published: 02 March 2022.

Edited by:

José Cleiton Sousa dos Santos, University of International Integration of Afro-Brazilian Lusophony, BrazilReviewed by:

Lummy Maria Oliveira Monteiro, University of São Paulo, BrazilDolores Reyes-Duarte, Metropolitan Autonomous University, Mexico

Copyright © 2022 Chauhan, Kaushal, Dhiman, Kanwar, Singh, Dhiman and Pandey. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shamsher Singh Kanwar, a2Fud2Fyc3MyMDAwQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Vivek Chauhan1

Vivek Chauhan1 Shamsher Singh Kanwar

Shamsher Singh Kanwar