- Department of Neurology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, China

Stroke (ST), endangering human health due to its high incidence and high mortality, is a global public health problem. There is increasing evidence that there is a link between the gut microbiota (GM) and neuropsychiatric diseases. We aimed to find the GM of ST, post-ST cognitive impairment (PSCI), and post-ST affective disorder (PSTD). GM composition was analyzed, followed by GM identification. Alpha diversity estimation showed microbiota diversity in ST patients. Beta diversity analysis showed that the bacterial community structure segregated differently between different groups. At the genus level, ST patients had a significantly higher proportion of Enterococcus and lower content of Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, and Megamonas. PSCI patients had a significantly higher content of Enterococcus, Bacteroides, and Escherichia-Shigella and a lower proportion of Faecalibacterium compared with patients with ST. Patients with PSTD had a significantly higher content of Bacteroides and Escherichia-Shigella and lower content of Enterococcus and Faecalibacterium. Parabacteroides and Lachnospiraceae were associated with Montreal cognitive assessment score of ST patients. Our study indicated that the characteristic GM, especially Bacteroidetes, could be used as clinical biomarkers of PSCI and PSTD.

Introduction

Stroke (ST) is the leading cause of death worldwide (Bonita et al., 2004). It can cause some neuropsychiatric diseases, including anxiety, depression, fatigue, apathy, personality changes, mania, and cognitive impairment. It is estimated that 1/3 of ST patients will develop neuropsychiatric disorders shortly after ST (Hackett and Pickles, 2014; Hackett et al., 2014). Post-ST cognitive impairment (PSCI) and post-ST affective disorder (PSTD) are the common complications of ST. The prevalence of depression and cognitive impairment within 3 months after ST are 25–31% and 10–47.3%, respectively (Aström et al., 1993; Jacquin et al., 2014). These two diseases usually coexist in ST patients and have a negative impact on the prognosis of the patient. Cognitive dysfunction is closely related to depression and interacts. Previous studies have shown that the cognitive function of ST patients after antidepressant treatment is normal, and vice versa, which suggest that they may have similar causes. In clinical practice, the limited use of scales and the inability to detect early symptoms have led to the failure of some patients with PSCI to receive correct diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, early evaluation and treatment of PSCI are important to prolong survival time after ST.

Gut microbiota (GM) disorders in neuropsychiatric diseases have been found in some studies (Bains et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2019). Recent studies have shown that there are significant differences in fecal microbial diversity in patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Zhuang et al., 2018). Jiang et al. found that the gut microbial structure of patients with active–severe depression has changed, among which, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Enterobacteriaceae significantly increased, Firmicutes and Faecalibacterium decreased significantly (Jiang et al., 2015). The reduced proportion of Faecalibacterium leads to chronic low-grade inflammation of the intestinal blood–brain barrier, and is negatively related to the severity of depressive symptoms (Jiang et al., 2015). Recent studies have shown that compared with healthy controls, the composition of the intestinal flora of AD patients has changed (Liu et al., 2019). These reports suggest that the GM may be a crucial regulator of two-way communication between the gut and the brain.

More and more evidence show that intestinal flora can be used as a non-invasive diagnostic biomarker for schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes. It is worth noting that ST patients show obvious intestinal floral imbalance (characterized by a higher abundance of conditional pathogenic bacteria and a lower level of beneficial bacteria). In addition, in patients with PSCI, the abundance of Fusobacteria increases and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) decrease. However, the composition of the GM in PSCI and PSTD patients has not been evaluated. Therefore, the discovery of the characteristics of the gut microbial composition of PSCI and PSTD patients is of great significance for rehabilitation after ST. Herein, we aimed to investigate the GM composition in ST, PSCI, and PSTD patients. Besides, we also confirmed the characteristic GM of PSCI and PSTD and its potential as a biomarker for the diagnosis of the disease.

Materials and Methods

Study Patients

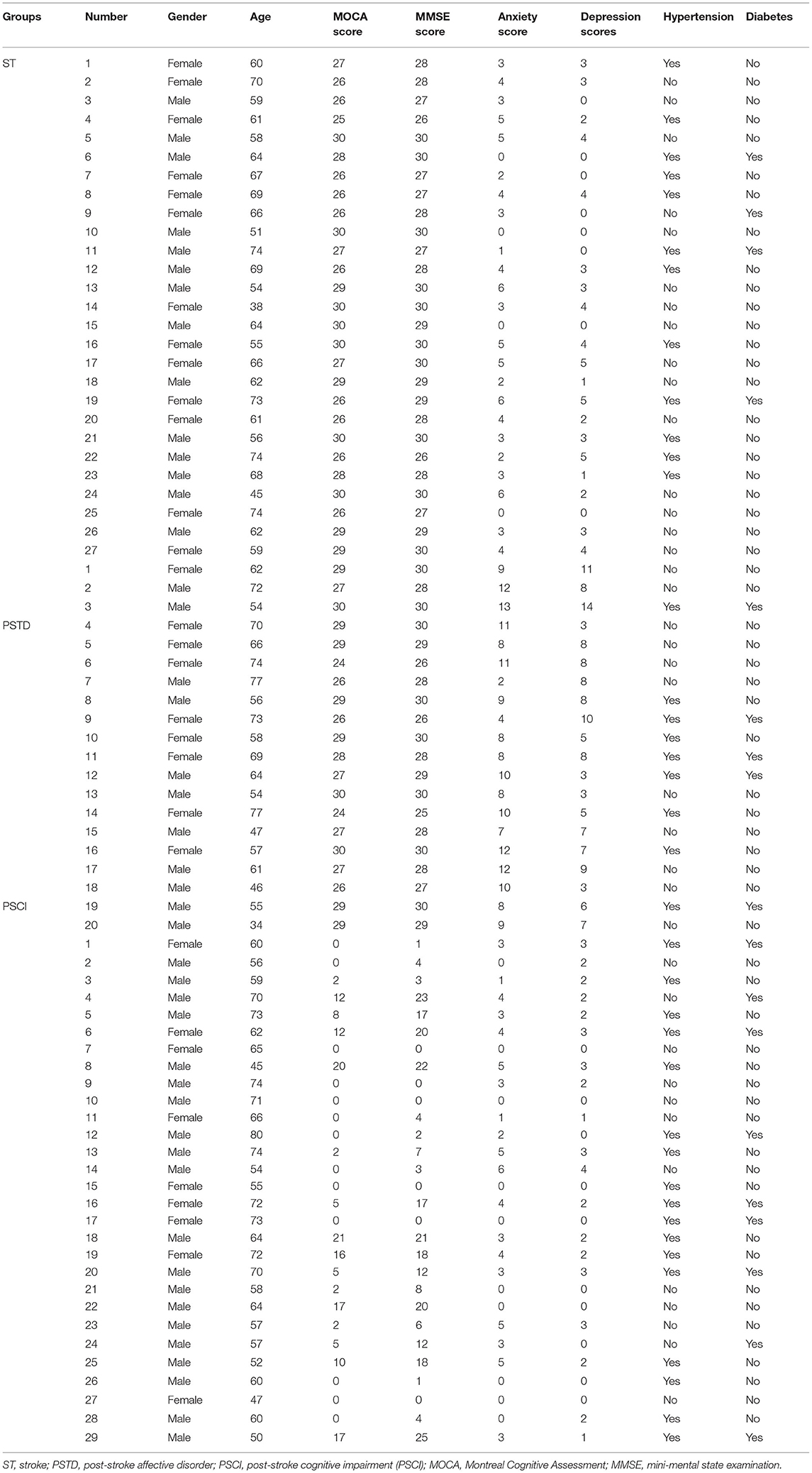

The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) patients were 40–90 years; (2) patients were ischemic ST; and (3) patients were with infarcts in non-strategic brain regions. Exclusion criteria of patients were as follows: (1) patients with preexisting dementia history and infarct of strategic regions; (2) patients took antibiotics or probiotics (within 3 months); (3) patients with a restrictive diet, gastrointestinal surgery, recent infection, psychosis, severe life-threatening illnesses, communication deficits, and pregnancy. A total of 95 ischemic ST patients were enrolled from the first affiliated hospital of Shantou University, Medical College, which included 19 healthy controls (HC), 27 ST patients, 29 PSCI patients, and 20 PSTD patients. Clinical characteristics of studying subjects are shown in Table 1. The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College approved the study protocol (2019), and all patients gave written informed consent.

Sample Collection and Processing

Fresh stool samples from all patients were obtained within 1 week of admission. Stool samples were collected and immediately transferred to the laboratory for repackaging within 15 min. Then 200 mg stool samples were put in a 2-mL sterile centrifuge tubes and labeled. All specimens were processed within 30 min and stored at −80°C. Stool genomic DNA was extracted as described in the previous study (Li et al., 2008; Shkoporov et al., 2018). We put the stool sample in the lysis buffer, added VAHTS DNA cleaning beads, homogenized it in a vortex mixer for 3–5 min, purified with 200 mL of 80% ethanol, and eluted with 24 mL of elution buffer. A 2% agarose gel was used to evaluate the amount of extracted genomic DNA. A NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to determine the DNA purity and concentration. The A260/280 ratio was measured to determine the DNA purity. Then we stored the DNA at −20°C. We amplified the 16S ribosomal RNA gene region of V3–V4 after DNA extraction as described in the previous study (Bu et al., 2018). We performed the high-throughput sequencing on a MiSeq Benchtop Sequencer (Illumina, Singapore, USA).

Bioinformatics Analysis

Bacterial diversity was determined by alpha diversity and beta diversity. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to identify significant differences in the α-diversity indices between the different groups. Beta diversity was analyzed by using Bray Curtis distances. The beta diversity was visualized via principal component analysis, principal coordinates analysis, and non-metric multidimensional analysis. Significant p-values associated with microbial clades and functions were identified by linear discriminant analysis effect size (Lefse; Qian et al., 2018). The Kruskal–Wallis test (alpha value of 0.05) and a linear discriminant analysis score >2 were the thresholds of the Lefse analysis. We used Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) to predict metagenomic functional information according to the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) table (Langille et al., 2013).

Results

Alpha Diversity Analysis in ST vs. HC, PSCI vs. ST, and PSTD vs. ST Groups

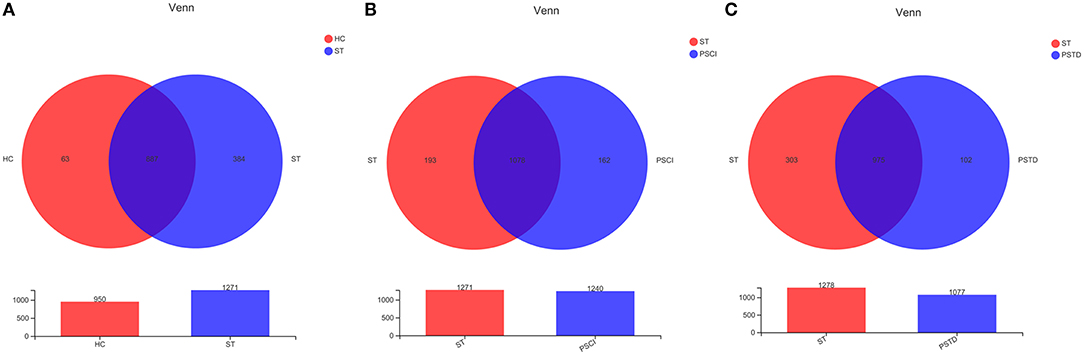

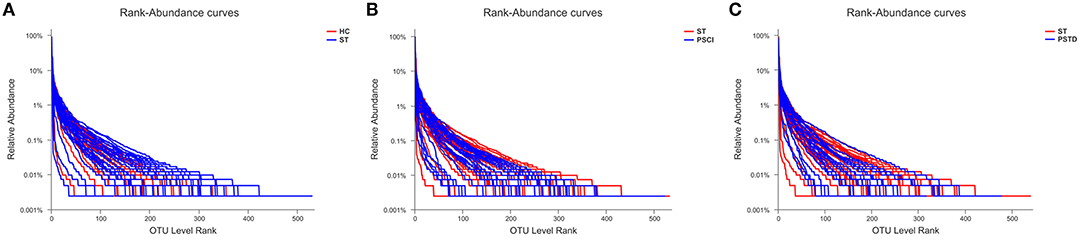

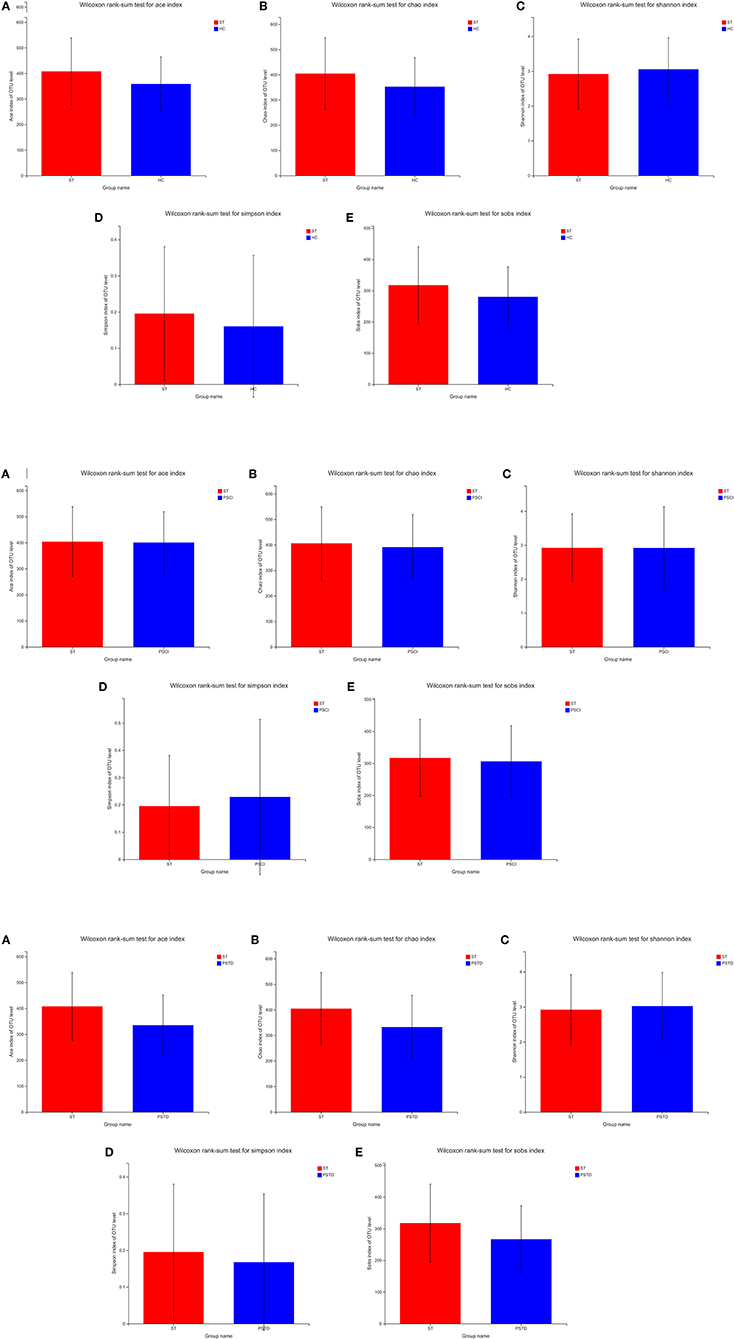

To evaluate core taxonomic characteristics of ST, PSCI, and PSTD patients, we generated profiles of V3–V4 variable region of the 16s rRNA gene. In Figure 1, rank abundance distribution curves suggested increased richness in ST group and decreased richness in PSCI and PSTD groups compared with the ST group. The alpha diversity indices, coverage evenness, and SD values are shown in Figure 2. As seen from the Venn diagram, there were, respectively 887, 975, and 1,078 common OTUs between ST vs. HC, PSTD vs. ST and PSCI vs. ST groups (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Rank-Abundance curve of the single sample in each group. X-axis and Y-axis means OUT from each sample and the relative abundance of OTUs, respectively. (A) ST vs. HC, (B) PSCI vs. ST, (C) PSTD vs. ST.

Figure 2. (A) Alpha diversity indices in ST vs. HC. (B) Alpha diversity indices in PSCI vs. ST. (C) Alpha diversity indices in PSTD vs. ST.

Alterations in the Composition of Stool Microbiota Associated With ST at the Genus Level

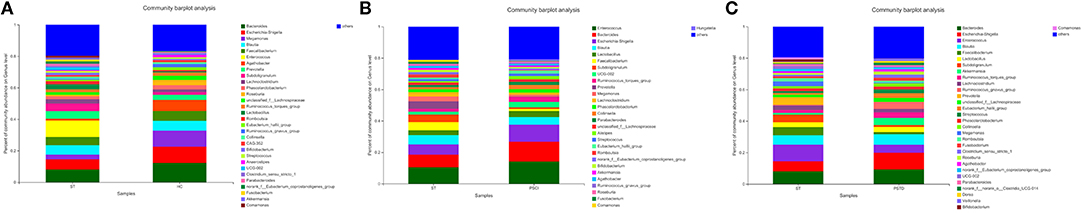

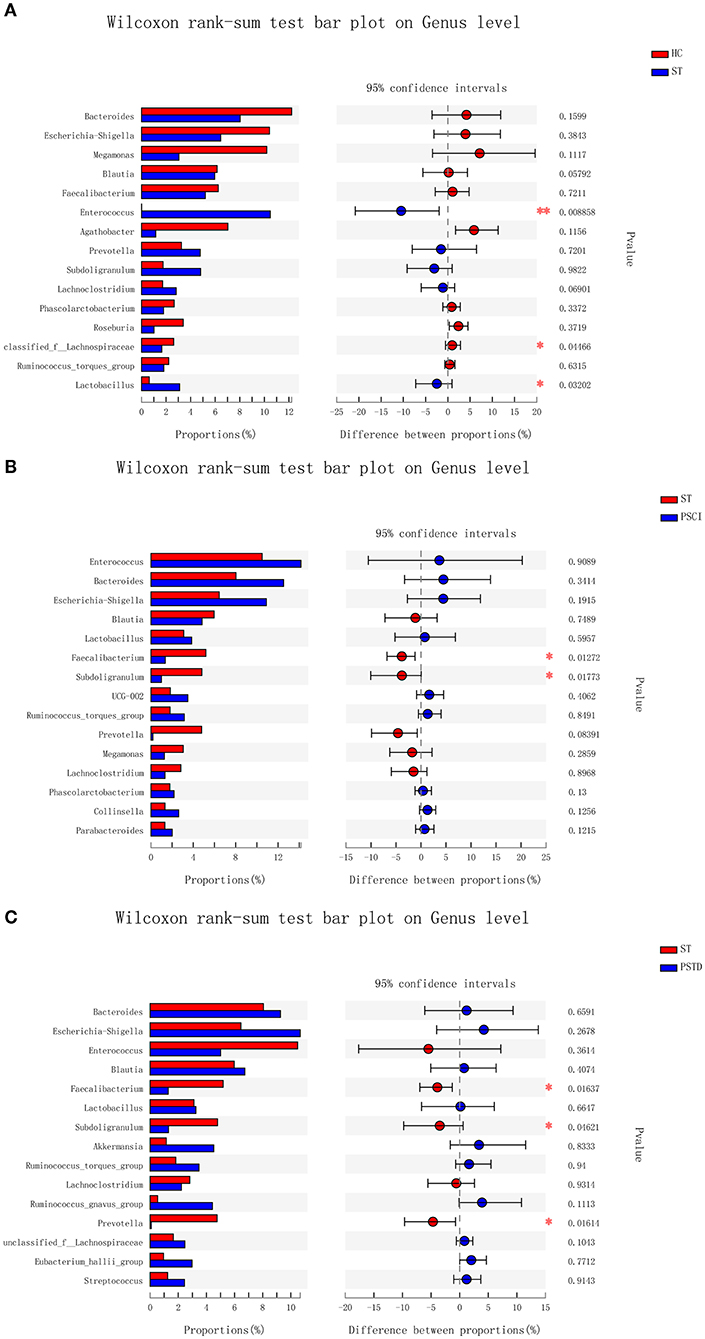

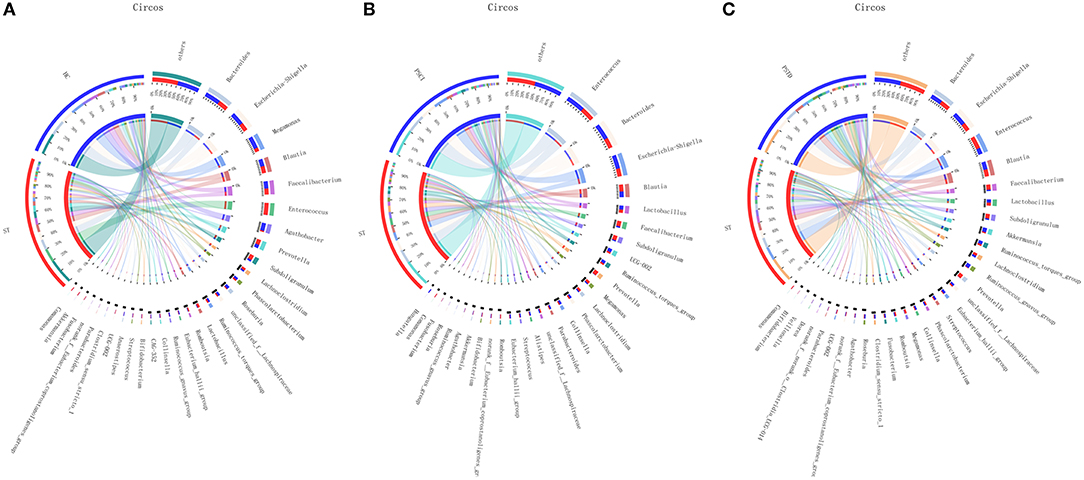

In Figure 4, the relative proportions of dominant taxa at the genus level were assessed. We observed considerable variability in stool microbiota across samples. Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, Megamonas, and Blautia were the most predominant genera in the ST vs. HC group (Figure 4A). Enterococcus, Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, and Blautia were the most predominant genera in the PSCI vs. ST group, whereas Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, Enterococcus, and Blautia were the most predominant genera in PSTD vs. ST group (Figures 4B,C). At the genus level, ST patients had a significantly higher proportion of Enterococcus and a lower content of Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, and Megamonas. By Wilcoxon rank-sum test, there was a significant increase in both the Enterococcus (P < 0.01) and Lactobacillus (P < 0.05) genus in the ST patients compared with the HC (Figure 5A). PSCI patients had a significantly higher proportion of Enterococcus, Bacteroides, and Escherichia-Shigella and lower content of Faecalibacterium compared with patients with ST. By Wilcoxon rank-sum test, there was a significant decrease in both the Faecalibacterium (P < 0.05) and Subdoligranulum (P < 0.05) genus in the PSCI patients compared with the ST patients (Figure 5B). PSTD patients had a significantly higher proportion of Bacteroides and Escherichia-Shigella and a lower content of Enterococcus and Faecalibacterium. By Wilcoxon rank-sum test, there was a significant increase in both the Faecalibacterium (P < 0.05) and Subdoligranulum (P < 0.05) genus in the PSTD patients compared with the ST patients (Figure 5C). From the Circos diagram, we further validated these results (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Distribution of the predominant bacteria at genus level of different groups. (A) ST vs. HC, (B) PSCI vs. ST, (C) PSTD vs. ST. The predominant taxa (>1% relative abundance) in each level are shown.

Figure 5. Bar charts of multi-species difference. (A) ST vs. HC, (B) PSCI vs. ST, (C) PSTD vs. ST. *0.01 < p < 0.05, **0.001 < p < 0.01.

Figure 6. Distribution of the predominant bacteria at genus level in Circos. (A) ST vs. HC, (B) PSCI vs. ST, (C) PSTD vs. ST.

Alterations in the Composition of Stool Microbiota Associated With ST at the Species Level

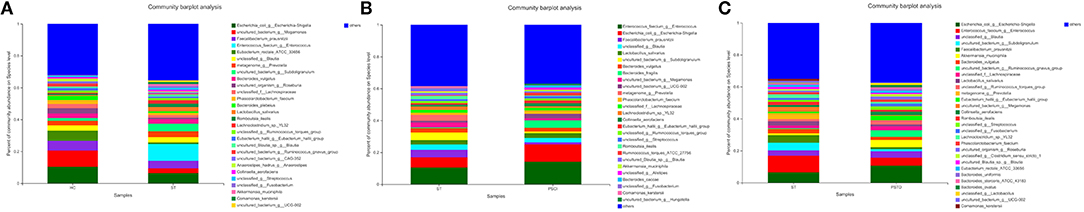

In Figure 7, the relative proportions of dominant taxa at the species level were assessed. We observed considerable variability in stool microbiota across samples. Escherichia_coli_g__Escherichia-Shigella, uncultured_bacterium_g__Megamonas, Faecalibacterium_prausnitzii, and Enterococcus_faecium _g__Enterococcus were the most predominant species in the ST vs. HC group. Enterococcus_faecium_g__Enterococcus, Escherichia_coli_g__Escherichia-Shigella, Faecalibacterium_prausnitzii, and unclassified_g__Blautia were the most predominant species in PSCI vs. ST group, whereas Escherichia_coli_g__Escherichia-Shigella, Enterococcus_faecium_g__Enterococcus, unclassified_g__Blautia, and uncultured_bacterium_g__Subdoligranulum were the most predominant species in PSTD vs. ST group. At the species level, ST patients had a significantly higher proportion of Enterococcus_faecium_g__Enterococcus and a lower content of Escherichia_coli_g__Escherichia-Shigella and uncultured_bacterium_g__Megamonas. PSCI patients had a significantly higher proportion of Enterococcus_faecium_g__Enterococcus, and Escherichia_coli_g__Escherichia-Shigella and a lower content of Faecalibacterium_prausnitzii compared with patients with ST. Patients with PSTD had a significantly higher content of Escherichia_coli_g__Escherichia-Shigella, a lower content of Enterococcus_faecium_g__Enterococcus, and uncultured_bacterium_g__Subdoligranulum.

Figure 7. Distribution of the predominant bacteria at the species level of different groups. (A) ST vs. HC, (B) PSCI vs. ST, (C) PSTD vs. ST. The predominant taxa (>1% relative abundance) in each level are shown.

Characteristics of Beta Diversity Analyses Between ST vs. HC, PSCI vs. ST, and PSTD vs. ST Groups

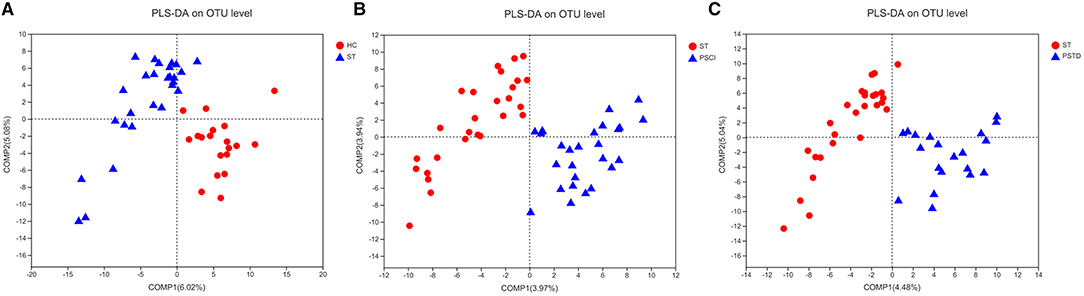

In Figure 8, beta diversity analysis was calculated based on partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). PLS-DA, based on OTUs, showed a separation between the ST vs. HC, PSCI vs. ST, and PSTD vs. ST groups in the first two principal component scores, which accounted for 6.02 and 5.08%, 3.97 and 3.94%, 4.48 and 5.04% of the total variations, respectively. This indicated that ST may be a key factor that accounts for the changes in the structure of the stool microbiota.

Figure 8. PLS-DA based on OTUs revealed a separation between the (A) ST vs. HC, (B) PSCI vs. ST and (C) PSTD vs. ST groups in the first two principal component score.

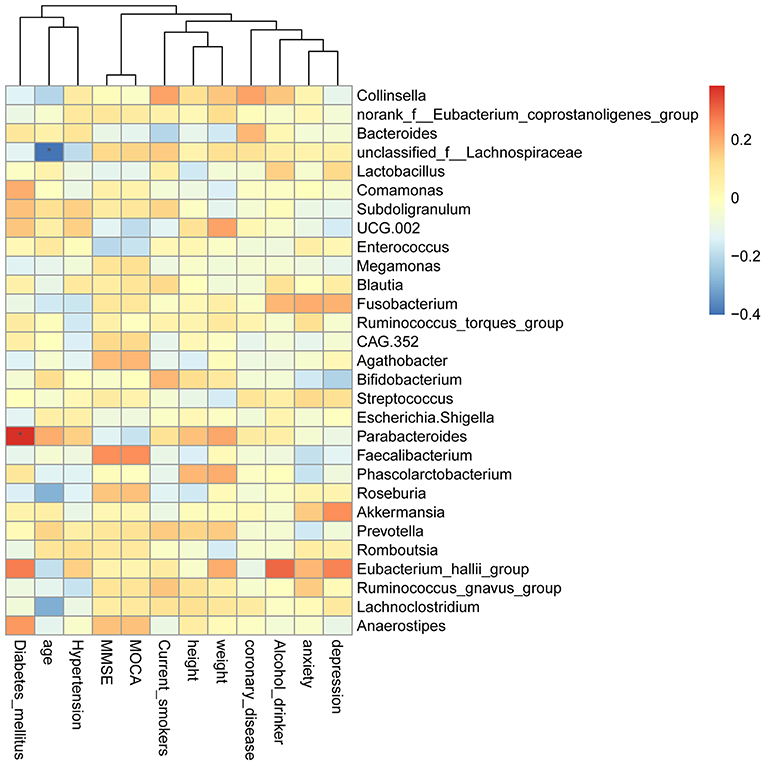

Correlation Between GM Composition and MOCA Score and Its Subvariables

The Spearman rank correlation was used to confirm the correlation between Montreal cognitive assessment (MOCA) score and the GM. As shown in Figure 9, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Anaerostipes, and Agathobacter were positively related to the MOCA score. Parabacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, Enterococcus, UCG.002, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides showed a negative correlation. Furthermore, we also investigated the correlation between GM and the MOCA subitems. Parabacteroides (P < 0.05), Eubacterium_hallii_group and Anaerostipes were found to be positively associated with diabetes_mellitus. Unclassified_f__Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia, and Lachnoclostridium were negatively correlated with age.

Figure 9. Heatmap of spearman rank correlation analysis between GM and MOCA score and its sub-variables.

Discussion

The gut–brain axis (GBA) is a two-way communication network between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract (Tan et al., 2020). GBA is regulated by the central nervous system, autonomic nervous system, enteric nervous system, and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (Carabotti et al., 2015). Acute ischemic ST induces dysbiosis of the microbiome, and these resultant changes in the GM affect neuroinflammatory processes and ST outcomes (bottom-up signaling). After ST, up to 50% of patients will experience dysphagia, constipation, gastrointestinal bleeding, and fecal incontinence (Harari et al., 2004; Schaller et al., 2006; Camara-Lemarroy et al., 2014). Gastrointestinal complications after ST lead to the delayed outcome, increased mortality, and progressive neurological dysfunction. It is shown that impaired intestinal flora could also be a risk factor for ST, which affects the prognosis after ST (Li et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2019).

Differences in microbiota composition are found between models and controls after ST. There are significant differences in the microbiota in all parts of the gastrointestinal tract, even at the phylum level. Growth of Bacteroides phylum after ischemia was confirmed in monkeys (Chen et al., 2019). The abundance of Bacteroides phylum also increased 3 days after the ischemic ST in mice, which is regarded as a feature of post-ST disorders (Singh and Roth, 2016). In contrast, a clinical study of stool samples collected 2 days after admission showed that patients with acute ischemic ST had decreased Bacteroidetes portal protein levels (Yin et al., 2015). In the study of monkeys after focal cerebral ischemia, the relative abundance of Prevotella increased, indicating that this type may be related to the inflammatory response after ST. Herein, we detect the GM composition of ST, PSCI, and PSTD patients. Although the bacterial diversity of GM in PSCI and PSTD patients was similar to that of ST patients, the microbial composition was distinct. At the genus level, ST patients had a significantly higher proportion of Enterococcus and a lower content of Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, and Megamonas. PSCI patients had a significantly higher proportion of Enterococcus, Bacteroides, and Escherichia-Shigella and a lower content of Faecalibacterium compared with patients with ST. PSTD patients had a significantly higher proportion of Bacteroides and Escherichia-Shigella and a lower content of Enterococcus and Faecalibacterium.

Among the population at high risk of ST, the microbiota alpha diversity index did not change significantly. However, conditional pathogens were found to be enriched in people at high risk of ST, and the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria was low (Zeng et al., 2019). Faecalibacterium is considered to be the main source of butyrate (Machiels et al., 2014). Butyric acid is a SCFA, which plays an important role in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier (Bourassa et al., 2016; Gophna et al., 2017). It is considered as a therapeutic target for brain dysfunction. Chronic intestinal dysbiosis may also affect the production of SCFAs (Chen et al., 2019). In our results, patients with PSCI and PSTD had a lower content of Faecalibacterium compared with patients with ST. We speculated that the reduction of Faecalibacterium leads to the reduction of butyrate content, which further damages the intestinal barrier and produces proinflammatory cytokines, thus aggravating the disease progression.

Cerebral ischemic ST also causes GM dysbiosis. Bacteroides plays a crucial role in the health of the host and can trigger endogenous infections or colitis when the normal microecological balance of the host is impaired (Wexler, 2007). Escherichia_Shigella can produce strong endotoxins, increase the intestinal permeability, and cause endotoxemia. Enterococcus is an important pathogen of nosocomial and postoperative infections, including the urinary tract and pelvic cavity infections (Sáez-Llorens et al., 1991; Watt et al., 2009). Our results showed that PSCI patients had a significantly higher content of Enterococcus, Bacteroides, and Escherichia-Shigella compared with ST patients. PSTD patients had a significantly higher content of Bacteroides and Escherichia-Shigella compared with ST patients. These results indicated that these opportunistic pathogens may play crucial roles in the progression of ST into PSCI and PSTD.

In the correlation analysis between MOCA score and the GM, we found that Parabacteroides were significantly positively associated with diabetes_mellitus. Unclassified_f__Lachnospiraceae was remarkably negatively correlated with age. Increased abundance of Parabacteroides is found in patients with ischemic ST compared with healthy individuals (Li et al., 2019). In patients with depression/anxiety, the content of Parabacteroides has changed (Roy et al., 1992; Cheung et al., 2019). In addition, the relative abundance of Parabacteroides is positively correlated with gastrointestinal tract (GI) symptoms in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (Li et al., 2020). Lachnospiraceae plays an important role in modulating GI motility (Yano et al., 2015). It is found that Lachnospiraceae dynamically changed with age and positively correlated with anxiety and cognition levels (Duan et al., 2019; Tengeler et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021). The abundance of Lachnospiraceae is significantly decreased in the age-matched PSCI patients (Ling et al., 2020). Moreover, Lachnospiraceae had a potential diagnostic value for patients with acute ischemic ST (Xiang et al., 2020). This suggested that Parabacteroides and Lachnospiraceae are associated with MOCA score of ST patients. However, there are limitations to our study. Firstly, the sample size in each group is small. More stool samples of patients are further needed. Secondly, the deeper mechanism research is not investigated. Further, the animal model is needed in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of repository and accession number (PRJNA734105) can be found in the SRA dataset (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA734105).

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YH and WH conceived and designed the experiments. YH and ZS performed the experiments and conducted the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by Jiacheng Li Foundation cross-research project in 2020. The continuous medical service management for stroke patients based on miRNA chip research, combined with Internet APP platform and artificial intelligence technology and medical, nursing and pharmaceutical “linkage” mode (2020LKSFG09C) and Trial Implementation Measures for supporting Project Scientific Research Special Plan of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College (Revised) (2019-70) (provided by WH).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aström, M., Adolfsson, R., and Asplund, K. (1993). Major depression in stroke patients. a 3-year longitudinal study. Stroke 24, 976–982. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.7.976

Bains, M., Laney, C., Wolfe, A. E., Orr, M., Waschek, J. A., Ericsson, A. C., et al. (2019). Vasoactive intestinal peptide deficiency is associated with altered gut microbiota communities in male and female C57BL/6 Mice. Front. Microbiol. 10:2689. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02689

Bonita, R., Mendis, S., Truelsen, T., Bogousslavsky, J., Toole, J., and Yatsu, F. (2004). The global stroke initiative. Lancet Neurol. 3, 391–393. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00800-2

Bourassa, M. W., Alim, I., Bultman, S. J., and Ratan, R. R. (2016). Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci. Lett. 625, 56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.009

Bu, X. L., Xiang, Y., Jin, W. S., Wang, J., Shen, L. L., Huang, Z. L., et al. (2018). Blood-derived amyloid-β protein induces Alzheimer's disease pathologies. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1948–1956. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.204

Camara-Lemarroy, C. R., Ibarra-Yruegas, B. E., and Gongora-Rivera, F. (2014). Gastrointestinal complications after ischemic stroke. J. Neurol. Sci. 346, 20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.08.027

Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., and Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann. Gastroentero. 28, 203–209.

Chen, Y., Liang, J., Ouyang, F., Chen, X., Lu, T., Jiang, Z., et al. (2019). Persistence of gut microbiota dysbiosis and chronic systemic inflammation after cerebral infarction in cynomolgus monkeys. Front. Neurol. 10:661. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00661

Cheung, S. G., Goldenthal, A. R., Uhlemann, A. C., Mann, J. J., Miller, J. M., and Sublette, M. E. (2019). Systematic review of gut microbiota and major depression. Front. Psychiatry 10:34. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00034

Duan, J., Yin, B., Li, W., Chai, T., Liang, W., Huang, Y., et al. (2019). Age-related changes in microbial composition and function in cynomolgus macaques. Aging 11, 12080–12096. doi: 10.18632/aging.102541

Gophna, U., Konikoff, T., and Nielsen, H. B. (2017). Oscillospira and related bacteria—from metagenomic species to metabolic features. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 835–841. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13658

Hackett, M. L., Köhler, S., O'brien, J. T., and Mead, G. E. (2014). Neuropsychiatric outcomes of stroke. Lancet Neurol. 13, 525–534. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70016-X

Hackett, M. L., and Pickles, K. (2014). Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Stroke 9, 1017–1025. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12357

Harari, D., Norton, C., Lockwood, L., and Swift, C. (2004). Treatment of constipation and fecal incontinence in stroke patients: randomized controlled trial. Stroke 35, 2549–2555. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000144684.46826.62

Jacquin, A., Binquet, C., Rouaud, O., Graule-Petot, A., Daubail, B., Osseby, G. V., et al. (2014). Post-stroke cognitive impairment: high prevalence and determining factors in a cohort of mild stroke. J. Alzheimers Dis. 40, 1029–1038. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131580

Jiang, H., Ling, Z., Zhang, Y., Mao, H., Ma, Z., Yin, Y., et al. (2015). Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 48, 186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016

Langille, M. G., Zaneveld, J., Caporaso, J. G., Mcdonald, D., Knights, D., Reyes, J. A., et al. (2013). Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 814–821. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676

Li, J., Lu, H., Wu, H., Huang, S., Chen, L., Gui, Q., et al. (2020). Periodontitis in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: impact on gut microbiota and systemic inflammation. Aging 12, 25956–25980. doi: 10.18632/aging.202174

Li, M., Wang, B., Zhang, M., Rantalainen, M., Wang, S., Zhou, H., et al. (2008). Symbiotic gut microbes modulate human metabolic phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 2117–2122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712038105

Li, N., Wang, X., Sun, C., Wu, X., Lu, M., Si, Y., et al. (2019). Change of intestinal microbiota in cerebral ischemic stroke patients. BMC Microbiol. 19:191. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1552-1

Ling, Y., Gong, T., Zhang, J., Gu, Q., Gao, X., Weng, X., et al. (2020). Gut microbiome signatures are biomarkers for cognitive impairment in patients with ischemic stroke. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12:511562. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.511562

Liu, P., Jia, X. Z., Chen, Y., Yu, Y., Zhang, K., Lin, Y. J., et al. (2021). Gut microbiota interacts with intrinsic brain activity of patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. CNS Neurosci. Therap. 27, 163–173. doi: 10.1111/cns.13451

Liu, P., Wu, L., Peng, G., Han, Y., Tang, R., Ge, J., et al. (2019). Altered microbiomes distinguish Alzheimer's disease from amnestic mild cognitive impairment and health in a Chinese cohort. Brain Behav. Immun. 80, 633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.05.008

Machiels, K., Joossens, M., Sabino, J., De Preter, V., Arijs, I., Eeckhaut, V., et al. (2014). A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 63, 1275–1283. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304833

Nguyen, T. T., Kosciolek, T., Maldonado, Y., Daly, R. E., Martin, A. S., Mcdonald, D., et al. (2019). Differences in gut microbiome composition between persons with chronic schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. Schizophr Res. 204, 23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.09.014

Qian, Y., Yang, X., Xu, S., Wu, C., Song, Y., Qin, N., et al. (2018). Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 70, 194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.02.016

Roy, A., Karoum, F., and Pollack, S. (1992). Marked reduction in indexes of dopamine metabolism among patients with depression who attempt suicide. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49, 447–450. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820060027004

Sáez-Llorens, X., Jafari, H. S., Olsen, K. D., Nariuchi, H., Hansen, E. J., and Mccracken, G. H. Jr. (1991). Induction of suppurative arthritis in rabbits by Haemophilus endotoxin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-1 beta. J. Infect Dis. 163, 1267–1272. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.6.1267

Schaller, B. J., Graf, R., and Jacobs, A. H. (2006). Pathophysiological changes of the gastrointestinal tract in ischemic stroke. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101, 1655–1665. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00540.x

Shkoporov, A. N., Ryan, F. J., Draper, L. A., Forde, A., Stockdale, S. R., Daly, K. M., et al. (2018). Reproducible protocols for metagenomic analysis of human faecal phageomes. Microbiome 6:68. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0446-z

Singh, V., and Roth, S. (2016). Microbiota dysbiosis controls the neuroinflammatory response after stroke. J. Neurosci. 36, 7428–7440. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1114-16.2016

Tan, B. Y. Q., Paliwal, P. R., and Sharma, V. K. (2020). Gut microbiota and stroke. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 23, 155–158. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_483_19

Tengeler, A. C., Dam, S. A., Wiesmann, M., Naaijen, J., Van Bodegom, M., Belzer, C., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota from persons with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder affects the brain in mice. Microbiome 8:44. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00816-x

Watt, J. P., Wolfson, L. J., O'brien, K. L., Henkle, E., Deloria-Knoll, M., Mccall, N., et al. (2009). Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 374, 903–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61203-4

Wexler, H. M. (2007). Bacteroides: the good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 593–621. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-07

Xiang, L., Lou, Y., Liu, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, W., Deng, J., et al. (2020). Gut microbiotic features aiding the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke. Fron. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 587284. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.587284

Yano, J. M., Yu, K., Donaldson, G. P., Shastri, G. G., Ann, P., Ma, L., et al. (2015). Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 161, 264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047

Yin, J., Liao, S. X., He, Y., Wang, S., Xia, G. H., Liu, F. T., et al. (2015). dysbiosis of gut microbiota with reduced trimethylamine-N-Oxide level in patients with large-artery atherosclerotic stroke or transient ischemic attack. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4:2699. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002699

Zeng, X., Gao, X., Peng, Y., Wu, Q., Zhu, J., Tan, C., et al. (2019). Higher risk of stroke is correlated with increased opportunistic pathogen load and reduced levels of butyrate-producing bacteria in the gut. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9:4. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00004

Keywords: stroke, 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing, post-stroke cognitive impairment, post-stroke affective disorder, gut microbiota

Citation: Huang Y, Shen Z and He W (2021) Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures in Patients With Post-stroke Cognitive Impairment and Affective Disorder. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13:706765. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.706765

Received: 08 May 2021; Accepted: 09 July 2021;

Published: 19 August 2021.

Edited by:

Gloria Patricia Cardona Gomez, University of Antioquia, ColombiaReviewed by:

Beita Zhao, Northwest A and F University, ChinaXavier Xifró, University of Girona, Spain

Copyright © 2021 Huang, Shen and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenzhen He, d2Vuemhlbl9oZUBzaW5hLmNvbQ==

†These authors contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Yinting Huang†

Yinting Huang† Wenzhen He

Wenzhen He