- 1Department of Botany, Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan

- 2Department of Botany, Pir Mehr Ali Shah Arid Agriculture University, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

- 3William L. Brown Center, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, United States

- 4Department of Botany, University of Swat, Swat, Pakistan

- 5Department of Botany, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal, Pakistan

- 6Botany and Microbiology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 7Department of Plant Production, College of Food and Agriculture Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Domestic animals play a vital role in the development of human civilization. Plants are utilized as remedies for a variety of domestic animals, in addition to humans. The tribes of North Waziristan are extremely familiar with the therapeutic potential of medicinal plants as ethnoveterinary medicines. The present study was carried out during 2018–2019 to record ethnoveterinary knowledge of the local plants that are being used by the tribal communities of North Waziristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. In all, 56 medicinal plant species belonging to 42 families were identified, which were reported to treat 45 different animal diseases. These included 32 herbs, 12 shrubs, and 12 trees. Among the plant families, Asteraceae contributed the most species (5 spp.), followed by Amaranthaceae (4 spp.), Solanaceae (4 species), and Alliaceae, Araceae, and Lamiaceae (2 spp. each). The most common ethnoveterinary applications were documented for the treatment of blood in urine, bone injury, colic, indigestion, postpartum retention, skin diseases, constipation, increased milk production, mastitis, foot, and mouth diseases.

Introduction

Plants have long been used as food (1), feed (2, 3), fiber (4), and shelter (5) by humans (6) and animals, as well as to control and alleviate diseases (7–9). Ethnoveterinary medicine (EVM) plays an essential role in animal production and livelihood development in many poor rural areas (10, 11) and is frequently the only option for farmers to treat their sick animals (12–14). The term “ethnoveterinary” is defined as “local people's beliefs and aboriginal knowledge and practice used for the treatment of animal diseases” (15–17). According to McCorkle and Schilihorn-van-Veen (7), it is a systematic study and application of indigenous knowledge for theory and practice in ethnoveterinary medicine (EVM). The information and ability of ethnoveterinary practices (EVPs) are recognized by means of experience and passed on verbally from one generation to the next (18, 19). Due to industrial and technological development, this local information remains in some parts of developed countries (20). Such knowledge and practices are passed down and retained from generation to generation (21), particularly by livestock owners. So, EVM is playing an important role in viable livestock farming in various parts of the world (22–24).

Pakistan is an agricultural country, with agriculture and livestock supporting up to 80% of the population (25, 26). Pakistan is the world's third largest milk producer, demonstrating the importance of cattle (27). Many Pakistani livestock producers are impoverished, and owing to financial restrictions (28), the majority of these farmers are unable to buy current allopathic medications, resulting in poor animal productivity and health. In such circumstances, ethnoveterinary medicine may be advocated as an alternative to contemporary pharmaceuticals (29), and it can aid in poverty reduction by enabling people to cure their animals using their own resources. Traditional indigenous medicine is still used in rural regions for human (30) and cattle diseases (31) and for the maintenance of excellent animal health in emerging nations, despite advances in the pharmaceutical industry and the creation of therapeutic agents (32–34). EVM knowledge, like all other traditional knowledge systems (35), is passed down orally from generation to generation and may become extinct (36) as a result of fast social, environmental, and technological changes (20, 37), as well as the loss of cultural legacy disguised as civilization (34). Traditional knowledge must be documented via systematic investigations (38–40) in order to be preserved before it is lost forever (21).

According to the literature, tremendous work has been done worldwide on the documentation of ethnoveterinary practices (8, 10, 18, 19, 41–43), but in Pakistan very little attention has been given to the documentation of EVM, resulting in limited reports on this important ethnoveterinary knowledge (12, 21, 44), revealing a significant gap in knowledge. For instance, Farooq et al. (45) reported 18 plant species representing 14 families to cure parasite disorders of livestock from the Cholistan desert of Pakistan, while Dilshad et al. (46) reported 66 plant species from Sargodha, Pakistan. Zia-ud-Din et al. (47) identified 35 plant species belonging to 25 families in a similar survey from the hilly area of Pakistan. Shoaib et al. (48) reported 41 medicinal plants belonging to 30 families to treat various livestock ailments from the Kaghan Valley, Western Himalayas–Pakistan. Siddique et al. (49) documented 80 medicinal plants belonging to 50 families to treat various livestock diseases from Haripur District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Various ethnoveterinary studies have been conducted in the allied areas of the study area (50–52), but no single ethnoveterinary documentation has been carried out in this unexplored, remote region of the tribal district of North Waziristan, Pakistan, highlighting the dire need to report this important knowledge. As a result, the current study is the first to investigate the entire ethnoveterinary practices of North Waziristan, Pakistan, where indigenous people have extensive traditional knowledge and rely heavily on medicinal plants to treat livestock ailments and supplement their income. This study might be beneficial to fill the gap that might have not been covered due to the negligence in documentation of ethnoveterinary practices. Therefore, it is extremely necessary to document and disseminate indigenous knowledge to help and share the different uses of plants as animal healthcare and to promote different conservation measures. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate and record the precious ethnoveterinary information of North Waziristan that is used by the area's indigenous inhabitants to treat domestic animals' diseases and disorders.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

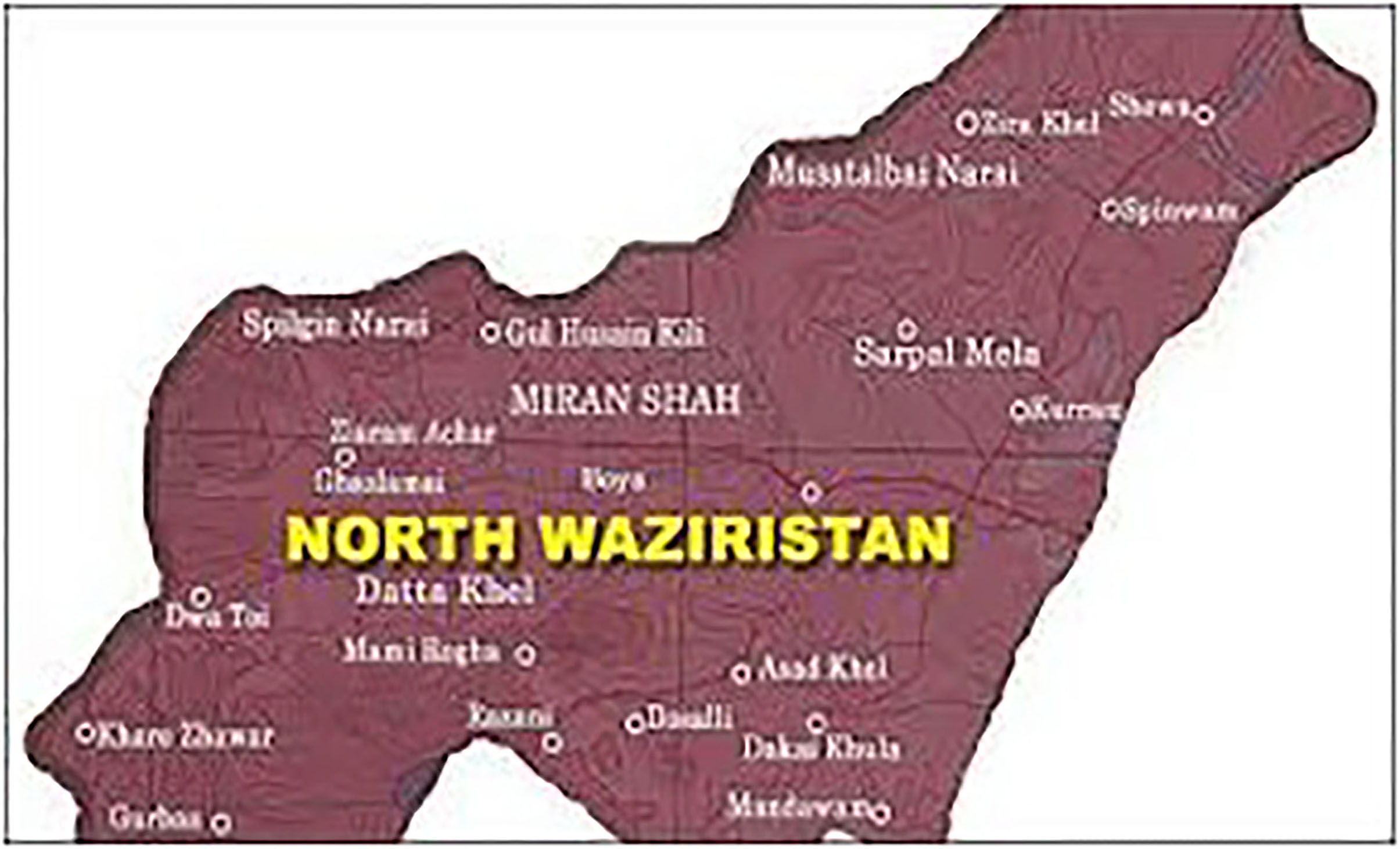

The tribal district of North Waziristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, is a hilly region that lies between 32–35° and 33–20° north latitudes and 69–25° and 70–40° east longitudes with an altitude of 2143–7717 feet (Figure 1). North Waziristan is bounded on the south by the district of South Waziristan; on the north by Kurram Agency, Hangu District, and Afghanistan; on the east by the district of Bannu; and on the west also by Afghanistan. North Waziristan falls under the Irano-Turanian Region. The area is bounded by mountains, which are connected with Koh-e-Sulaiman in the south and Koh-e-Sufaid in the north. The tribal district is well-populated with various small dynamized villages. The main hills are Alexandra, Larema, Kalenjer Ser, Vezda, Ebulnki, and Sedgai Gher. The area is divided into three sub-divisions and nine tehsils. The Tochi Valley is 101 km long. The annual rainfall is 10“−13.” The summer period starts from May to September. The hottest month is June. The winter season starts from October to March. The coldest months are December, January, and February.

According to the census report of 2017, the total population of North Waziristan is 543,254. The total forest area is 475,000 acres. Wazir and Dawar are the major tribes in the research area. Pashto is the major language. The joint family system is practiced in the study area. The funeral and death ceremonies are mutually attended by the relatives and friends. The citizens of the area follow the jirga to determine their administrative and social problems. This is one of the strongest and most active common institutions in the area. The people in the area are mostly poor and earn their income from basic jobs. These include wood sellers, farmers, shopkeepers, horticulturists, local health healers, pastoralists, and government employees. In the study area, the domestic animals kept by the pastoralists are considered a better source of income.

Field Survey and Data Collection

The area of the study was visited during March and October 2018–2019 in order to collect ethnoveterinary data. The assessment was organized to collect data by using a semi-structured interview based on folk knowledge (35, 53) about plants that are used for the curing of various animal ailments (21, 54). The local people have valuable information about ethnoveterinary uses of the plants. All the collected plant species were photographed (Figure 2). During the study period, different types of herbal medicine were sold on the market, and the multi-use roles of some ethnoveterinary herbal plants were noted. Moreover, herbal remedy suppliers were interviewed. During the survey, every care was taken to note the vernacular names, dosage, parts used, mode of application, drug preparation method, and uses. Overall, 130 informants, 92 men and 38 women, were interviewed during the survey.

Herbarium Work

Plant specimens were collected, pressed, dried, poisoned, and mounted on standard herbarium sheets (55, 56). The mounted specimens were then identified using published literature (57–59). For authentication purposes, Quaid-e-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan, was also consulted. The identified specimens were deposited for future records in the Department of Botany at Hazara University, Mansehra, Pakistan.

Statistical Data Analysis

The indigenous knowledge data were collected and analyzed statistically (36, 60, 61) using different quantitative indices: fidelity level (FL%) and informant consensus factor (ICF).

Fidelity Level (FL%)

The fidelity level (FL%) was the percentage of informants who reported the uses of certain plant species to cure a specific disease reported from the area of study. The fidelity level was calculated as follows (62, 63):

where Np is the number of informants that mention a use of a plant species to cure a specific disease and N is the number of informants that use the plant species to cure any other disease.

Informant Consensus Factor

The informant consensus factor (ICF) was used to seek agreement among the informants on the documented cures for each ailment category (64).

where Nur is the number of use reports from informers in each disease category and Nt is the number of taxa used.

Results

Demographic Data

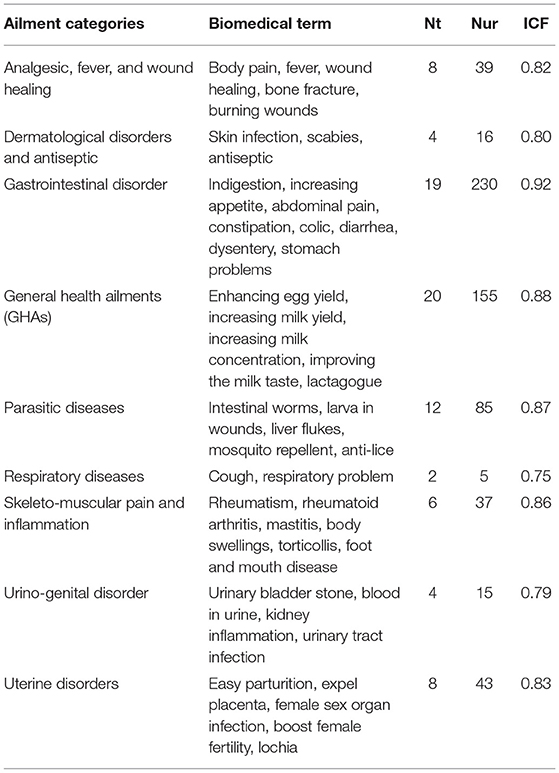

A total of 130 informants were interviewed. Most informants were men (83.85%) rather than women (16.15%). Many of them were over 60 years old (46.79%), 51–60 years old (39.23%), and 35–50 years old (23.88%). Due to the lack of educational facilities in that area, most of the informants were illiterate (45.38%; Table 1). But some were educated, showing that they had an awareness of education (8.46%). Many informants had completed primary (31.54%) and middle-level education (14.62%). All the informants spoke Pashto.

Table 1. Demographic details of the informants interviewed during ethnoveterinary survey in the study area.

Ethnoveterinary Plant Species

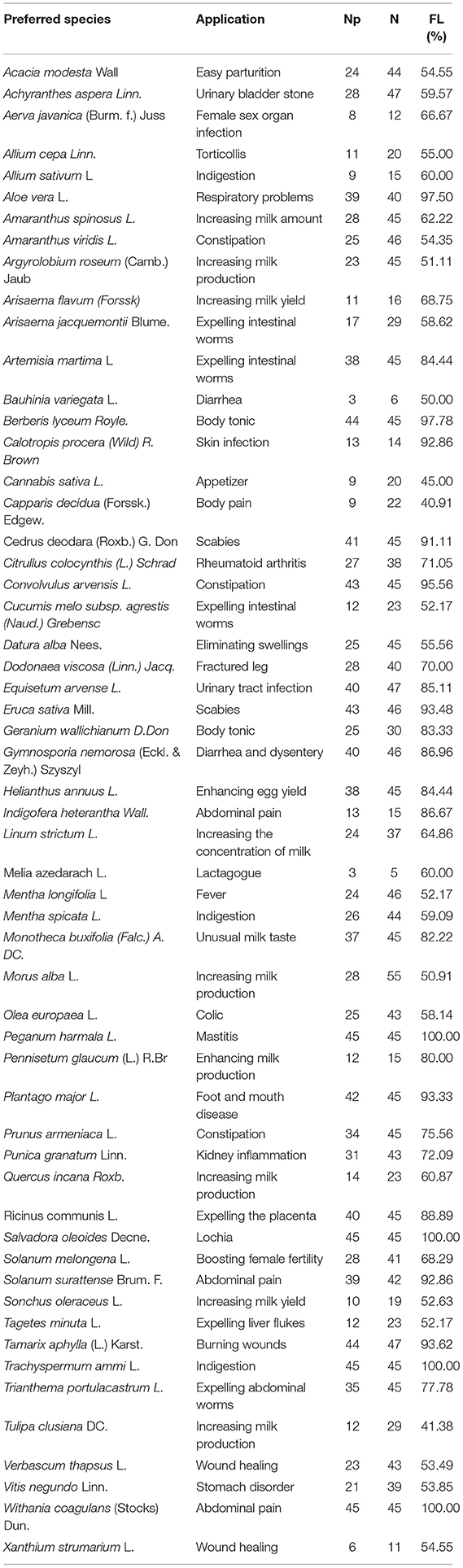

During the present study, a total of 56 plant species belonging to 42 families were documented to be used in the treatment of 45 different ailments by the local herders, farmers, and shepherds in the tribes of North Waziristan, Pakistan. The results collected during the study are summarized, which provide the following knowledge for each plant species: botanical name, family name, vernacular name, habitat, part used, and disease treated (Table 2).

Table 2. List of ethnoveterinary plants (EVPs) used by tribes for healing of different ailments in North Waziristan, Pakistan.

Habitat of Medicinal Plants

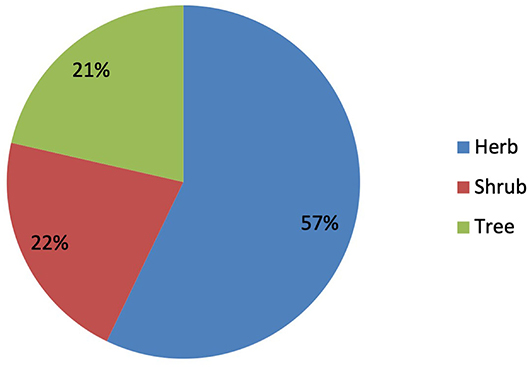

In the present study, it was revealed that the herbs were the most commonly used life form by the inhabitants, with 32 species (57.14%; Figure 3). It was followed by shrubs and trees (12 spp., 21.43% each). The dominant use of herbaceous plants in the study area in the preparation of remedies is due to profuse growth and easy availability in the wild as compared to other life forms.

Medicinal Plant Families

The families that represented the highest number of plant species for the indigenous ethnoveterinary medicines were Asteraceae (5 spp., 8.93%), followed by Amaranthaceae and Solanaceae (4 spp., 7.14% each), Alliaceae, Araceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Lamiaceae (2 spp., 3.57% each), while the remaining families were represented by 1 species (1.79% each) in Table 2.

Diseases Cured

Among all the 45 diseases in the study area, the indigenous healers and other local informants reported milk production (increased milk yield) as the most common problem treated through 12 plant species. It is followed by intestinal worms with 6 species each; abdominal pain with 5 species; constipation, diarrhea, and expulsion of placenta with 4 species each; and fever and indigestion with 3 species each. However, all the remaining 37 diseases were treated by <3 species each (Table 2).

Plant Parts Used as Indigenous Medicine

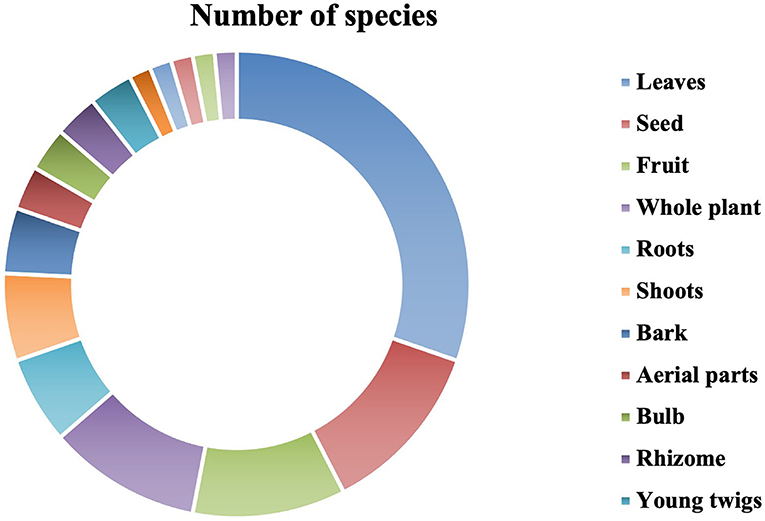

Different parts of the plant were used to prepare ethnoveterinary medicine recipes to treat various ailments and are summarized in Figure 4 and Table 2. Out of 16 plant parts, leaves were heavily used to prepare medication (20 spp., 30.30%), followed by seeds (8 spp., 12.12%); fruits and whole plants (7 spp., 10.61%); roots and shoots (4 spp., 6.06%); bark (3 spp., 4.55%); aerial parts, bulbs, rhizomes, and young twigs (2 spp., 3.03% each); and flowers, latex, husk, stems, and wood oil (1 spp., 1.520% each). The collection of leaves and recipes for preparation from the leaves is much easier. So, leaves were the most used plant part in the preparation of remedies for the treatment of livestock ailments.

Mode of Preparation in Indigenous Medicine

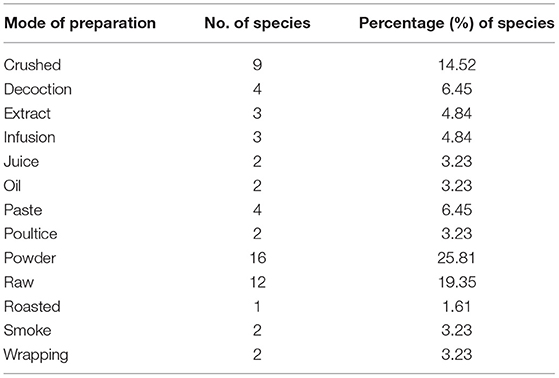

For treating 45 different diseases and ailments, about 11 different types of formulations were prepared from different plants (Table 3), in which most of the ethnoveterinary remedies were prepared as powders (16 spp., 25.81%), followed by raw (12 spp., 19.35%), crushed (9 spp., 14.52%), decoction and paste (4 spp., 6.45% each), and extract and infusion (3 spp., 4.84% each). Nonetheless, juice, oil, poultice, smoke, and wrapping (2 spp., 3.23% each), followed by the roasted mode of preparation for treating diseases, were recorded with the smallest number of species (1 spp., 1.61%). The most dominant method for the preparation of remedies was powder, which was used in the treatment of animals' diseases.

Mode of Administration

In the current study, the most common mode of application/administration is oral application (48 spp., 81.36%), followed by topical application (9 spp., 15.25%) and inhalation (2 spp., 3.39%) (Figure 4). The majority of remedies were administered orally in the study area for the treatment of different ailments.

Quantitative Analysis

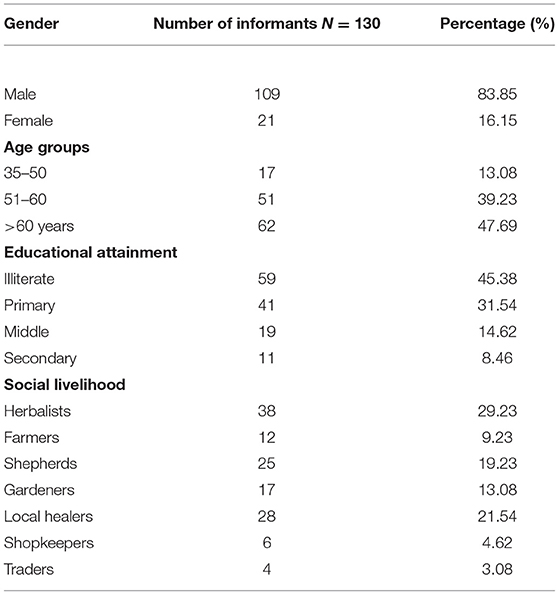

Informant Consensus Factor

In the present study, we recorded ICF values ranging from 0.75 to 0.92 (Table 4). With 230 use reports, gastrointestinal disorder had the highest ICF value (0.92), followed by general health ailments (0.88); parasitic diseases (0.87); skeleto-muscular pain and inflammation (0.86); uterine disorders (0.83); analgesic, fever, and wound healing (0.82); dermatological disorders and antiseptic (0.80); urino-genital disorder (0.79); and respiratory diseases (0.75).

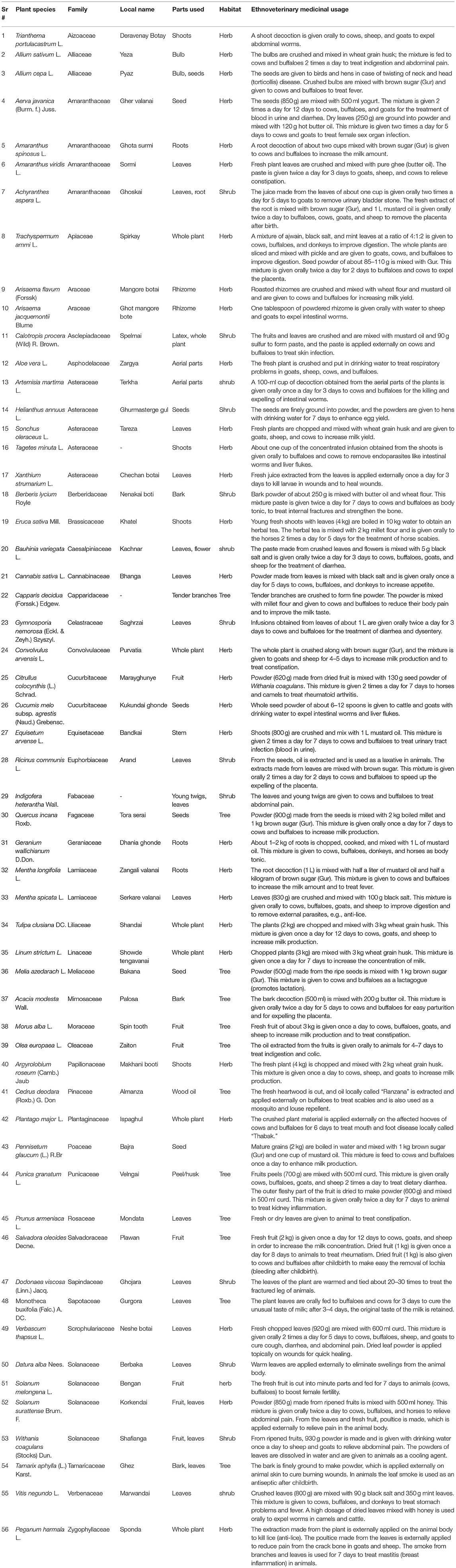

Fidelity Level (FL%) of the Reported Ethnoveterinary Plants

In the present survey, the FL of medicinal plants varied between 40.91 and 100%. Four medicinal plants, viz., Trachyspermum ammi, Salvadora oleoides, Peganum harmala, and Withania coagulans, were the most important medicinal plants in the study area, which were particularly used to treat indigestion, lochia, mastitis, and abdominal pain, determined by 45 interviewers with 100% fidelity (Table 5), followed by Berberis lycium, which was the 2nd most important ethnoveterinary plant, having a fidelity level of 97.78% used in body tonic. Aloe vera was the third most important medicinal plant, having a fidelity level of 97.50% FL and used in respiratory problems, while Capparis decidua had the lowest fidelity level (40.91%) and is used in body pain. However, the rest of the medicinal plants were within the fidelity range of 41.38–95.56%.

Discussion

One of the most important income sources for rural populations in the tribal district (North Waziristan) is livestock raising. According to the findings of the present study, farmers in the region rely on plants not only for food for their livestock but also for usage as medications to treat livestock diseases. In the present study, we have documented 56 plant species belonging to 42 families. Khan et al. (65) documented various animal diseases that were cured using indigenous herbal medicines. Similarly, Hassan et al. (34) reported 28 medicinal plants belonging to 23 families for treating various livestock diseases from Lower Dir District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Badar et al. (66) recorded 46 medicinal plants belonging to 31 families for treating 26 various livestock ailments from the district of Jhang, Pakistan. Traditional remedies were little known to the younger generation, but the elders knew a lot more about how to cure livestock problems. These results are in accordance with Zerabruk and Yirga (67) and Khattak et al. (36). They found that the majority of respondents were elderly, with very few youngsters engaging in traditional livestock treatment.

The families that represented the highest number of plant species for the indigenous ethnoveterinary medicines were the Asteraceae (5 spp., 8.93%), followed by Amaranthaceae and Solanaceae (4 spp., 7.14% each). The higher distribution and richness of medicinal plant species from the aforementioned families might be linked to their dominance in the area (68). Furthermore, the widespread use of species from these groups might be linked to the existence of beneficial bioactive chemicals (69, 70) that protect livestock against diseases (71). Moreover, it was revealed that herbs were the most used growth form by the inhabitants, with 32 species (57.14%). They were followed by shrubs and trees (12 spp., 21.43% each). Herbaceous plants are also widely used in other parts of the world (72). The dominant use of herbs was also documented in other ethnoveterinary studies carried out by various researchers around the world (20, 21, 36, 37, 54, 73, 74). Indigenous healers used herbs most often as medication due to their availability in nature (75, 76), which are used by local people for the treatment of 45 animal diseases (blood in urine, bone injury, colic, indigestion, after-birth retention, constipation, milk production, foot and mouth disease, mastitis, and diarrhea, etc.). These diseases are usually observed in various animals, i.e., sheep, cows, goats, buffaloes, and horses.

The aboriginal people were collecting various plant parts (i.e., fruit, seeds, roots, bark, leaves, stems, aerial parts, and whole plants) used in the preparation of various remedies. Some important plants that are present but not in abundance are severely threatened due to maximum collection, trading, and grazing. The most frequently used plant parts are leaves (18, or 18.4% each), followed by seeds (6, or 6.1% each), fruits (6, or 6.1% each), whole plants (4, or 4.1% each), and roots and bark (2, or 2.0% each). Throughout the world, ethnic communities use leaves for the preparation of herbal ethnoveterinary medicine (77, 78). Similar findings were reported by Erarslan and Kultur (79); they reported that the local inhabitants of Turkey used leaves for most ethnoveterinary remedies. Poffenberger et al. (80) found that collecting leaves does not constitute a major threat to plant species' survival as compared to collecting underground parts such as stems, bark, or the entire plant. The usage of certain plant parts implies that these portions have the most therapeutic potential, although biochemical testing is required as well as pharmaceutical screening to double-check the location information (34). Traditional knowledge about indigenous ethnomedicine is mainly transmitted by oral tradition from generation to generation without any written record. Such practices are still common among rural and tribal communities in many parts of the world. Aged and uneducated people were more familiar with the preparation and use of remedies. The addition of scientifically validated ethnoveterinary applications in rural areas helps in poor quality improvement and raises livestock production (15, 81).

The common mode of application/administration is oral application (48 spp., 81.36%). The majority of remedies were administered orally in the study area for the treatment of different ailments. Similar results were also documented in previously reported literature (82). In the present work, some of the therapeutic properties of the plant species mentioned have already been validated based on pharmacology. For example, Kumar and Roy (83) prove practically that C. procera latex is used against inflammation. But the administration of ethnoveterinary recipes is a huge problem in the area because there is no standardized measurement unit for the plant remedies. Although the dosage was determined by using glass, cups, and plant parts like seeds and bulbs, the amount of dosage is usually dependent on the age, intensity of disease, and size of the animal. This type of dose measurement method is not appropriate. That is why veterinarians are dissatisfied with EVMs (84–86). The most dominant method for the preparation of remedies was powder, which was used in the treatment of animal diseases and showed similar results to the previously documented literature (87). However, the most common procedure of drug preparation, according to Deeba et al. (88) is grinding or crushing followed by soaking or boiling. In many cases, the procedure of medicine preparation differs from individual to individual person to the next. Traditional veterinary therapists preferred the same plant for treating the same disease in different ways (34).

In the present study, with 230 use reports, gastrointestinal disorder had the highest ICF value (0.92), followed by general health ailments (0.88) and parasitic diseases (0.87). The maximum number of informant citations for these infections indicates a high frequency of these ailments in the area. It has previously been reported that stomach disorders are more prevalent in lactating livestock, possibly as a result of poor feed and drinking water quality (89, 90). Medicinal plants utilized to treat disease categories with high ICF values are likely to have high potency, making them potential candidates for pharmacological and phytochemical research (91). The fidelity value of a medicinal plant species determines whether it is preferred for the treatment of a specific ailment (63). In the present survey, four medicinal plants, viz., Trachyspermum ammi, Salvadora oleoides, Peganum harmala, and Withania coagulans, were the most important medicinal plants that were particularly used to treat indigestion, lochia, mastitis, and abdominal pain, as determined by 45 interviewers with 100% fidelity. Moreover, Berberis lycium was found as the 2nd most important ethnoveterinary plant, having 97.78% FL and was reported as a body tonic, and Aloe vera was the 3rd most important medicinal plant, with 97.50% FL, used for respiratory problems. The maximum level of fidelity is always gained by widely utilized medicinal plants for specific ailments (90).

Conclusion

This is the first ever study to document medicinal plants that are being used by the shepherds of North Waziristan, Pakistan, to treat livestock diseases. Due to modernization, the younger generations do not pay attention to the traditional knowledge of plants, and this knowledge was restricted only to shepherds, herders, farmers, and the elderly. Therefore, the present study is an important contribution to preserving the botanical wisdom of the local communities in treating animal diseases. The results showed that 56 medicinal plants are used in treating 45 diseases, of which 12 plant species are used in enhancing milk production. Among the highest uses of plants, five species, viz., Trachyspermum ammi, Salvadora oleoides, Peganum harmala, and Withania coagulans, were particularly used to treat indigestion, lochia, mastitis, and abdominal pain. Based on the results, it can be concluded that phytochemical and pharmacological screening of these plants is required to isolate the bioactive compounds, coupled with in vitro and in vivo studies for the reported veterinary diseases.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the first author.

Author Contributions

SR collected the data. SR, RQ, and IR analyzed and interpreted the data and results. IR and SR wrote first draft of the manuscript. SS, IK, AH, A-BA-A, KA, EA, NA, MK, and FI helped in gathering literature and discussion section. AH, A-BA-A, EA, and FI helped in revising the manuscript. ZI and RQ supervised the work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to Researchers Supporting Project Number RSP-2021/356, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the local community members of the study area for sharing their valuable information. This manuscript is part of the PhD dissertation of the first author. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to Researchers Supporting Project Number RSP-2021/356, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

1. Bussmann RW, Paniagua Zambrana NY, Ur Rahman I, Kikvidze Z, Sikharulidze S, Kikodze D, et al. Unity in diversity—food plants and fungi of Sakartvelo (Republic of Georgia), Caucasus. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2021) 17:1–46. doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00490-9

2. Oliveira M, Hoste H, Custodio L. A systematic review on the ethnoveterinary uses of Mediterranean salt-tolerant plants: exploring its potential use as fodder, nutraceuticals or phytotherapeutics in ruminant production. J Ethnopharmacol. (2021) 267:113464. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113464

3. Shaheen H, Qureshi R, Qaseem MF, Bruschi P. The fodder grass resources for ruminants: a indigenous treasure of local communities of Thal desert Punjab, Pakistan. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0224061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224061

4. Rahman IU, Afzal A, Iqbal Z, Ijaz F, Ali N, Shah M, et al. Historical perspectives of ethnobotany. Clin Dermatol. (2019), 37: 382–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.03.018

5. Scheel-Ybert R, Bachelet C. A good place to live: plants and people at the Santa Elina rock shelter (Central Brazil) from Late Pleistocene to the Holocene. Lat Am Antiq. (2020) 31:273–91. doi: 10.1017/laq.2020.3

6. Ahmed J, Rahman IU, AbdAllah EF, Ali N, Shah AH, Ijaz F, et al. Multivariate approaches evaluated in the ethnoecological investigation of Tehsil Oghi, Mansehra, Pakistan. Acta Ecol Sin. (2019) 39: 443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chnaes.2018.11.006

7. McCorkle CM, Schilihorn-van-Veen TW. Ethnoveterinary research & development. (Studies in Indigenous Knowledge and Development). Intermediate Technology Publications. (1996). p. 450.

8. Güler O, Polat R, Karaköse M, Çakilcioglu U, Akbulut S. An ethnoveterinary study on plants used for the treatment of livestock diseases in the province of Giresun (Turkey). South African J Bot. (2021) 142:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.06.003

9. Prakash P, Kumar M, Pundir A, Puri S, Prakash S, Kumari N, et al. Documentation of commonly used ethnoveterinary medicines from wild plants of the high mountains in Shimla District, Himachal Pradesh, India. Horticulturae. (2021) 7:351. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae7100351

10. Chaachouay N, Azeroual A, Bencharki B, Douira A, Zidane L. Ethnoveterinary medicines plants for animal therapy in the Rif, North of Morocco. South African J Bot. (2022) 147:176–91. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.12.037

11. Scialabba NE-H. “Full-cost accounting for decision-making related to livestock systems,” in Managing Health Livestock Production and Consumption (Academic Press), p. 223–44. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-823019-0.00026-X

12. Akhtar MS, Iqbal Z, Khan MN, Lateef M. Anthelmintic activity of medicinal plants with particular reference to their use in animals in the Indo–Pakistan subcontinent. Small Rumin Res. (2000) 38:99–107. doi: 10.1016/S0921-4488(00)00163-2

13. Hassen A, Muche M, Muasya AM, Tsegay BA. Exploration of traditional plant-based medicines used for livestock ailments in northeastern Ethiopia. South African J Bot. (2022) 146:230–42. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.10.018

14. Agani ZA, Boko C, Orou DB, Dossou J, Babatounde S. Ethnoveterinary study of galactogenic recipes used by ruminant breeders to improve milk production of local cows in Benin Republic. J Ethnopharmacol. (2022) 285:114869. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114869

15. Mathias E. Ethnoveterinary medicine in the era of evidence-based medicine: mumbo-jumbo, or a valuable resource? Vet J. (2006) 173:241–2. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.12.005

16. Oyda S. Review on traditional ethno-veterinary medicine and medicinal plants used by indigenous people in Ethiopia: practice and application system. Int J Res. (2017) 5:109–19. doi: 10.29121/granthaalayah.v5.i8.2017.2193

17. Wanzala W, Zessin KH, Kyule NM, Baumann MPO, Mathia E, Hassanali A. Ethnoveterinary medicine: a critical review of its evolution, perception, understanding and the way forward. Livestock Research for Rural Development (2005).

18. Stucki K, Cero MD, Vogl CR, Ivemeyer S, Meier B, Maeschli A, et al. Ethnoveterinary contemporary knowledge of farmers in pre-alpine and alpine regions of the Swiss cantons of Bern and Lucerne compared to ancient and recent literature – Is there a tradition? J Ethnopharmacol. (2019) 234:225–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.12.022

19. McGaw LJ, Famuyide IM, Khunoana ET, Aremu AO. Ethnoveterinary botanical medicine in South Africa: a review of research from the last decade (2009 to 2019). J Ethnopharmacol. (2020) 257:112864. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112864

20. Tabuti JRS, Dhillion SS, Lye KA. Ethnoveterinary medicines for cattle (Bos indicus) in Bulamogi county, Uganda: plant species and mode of use. J Ethnopharmacol. (2003) 88:279–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00265-4

21. Khan K, Rahman IU, Soares EC, Ali N, Ijaz F, Calixto ES, et al. Ethnoveterinary therapeutic practices and conservation status of the medicinal flora of Chamla Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Front Vet Sci. (2019) 6:122. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00122

22. Lin JH, Kaphle K, Wu LS, Yang NYJ, Lu G, Yu C, et al. Sustainable veterinary medicine for the new era. Rev Sci Tech Int des épizooties. (2003) 22:949–64. doi: 10.20506/rst.22.3.1451

23. Mwale M, Masika PJ. Ethno-veterinary control of parasites, management and role of village chickens in rural households of Centane district in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod. (2009) 41:1685–93. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9366-z

24. Adekunmi AO, Ajiboye A, Awoyemi AO, Osundare FO, Oluwatusin FM, Toluwase SOW, et al. Assessment of ethno-veterinary management practices among sheep and goat farmers in Southwest Nigeria. Annu Res Rev Biol. (2020) 35:42–51. doi: 10.9734/arrb/2020/v35i330199

25. Raheem A, Hassan MY, Shakoor R. Bioenergy from anaerobic digestion in Pakistan: Potential, development and prospects. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. (2016) 59:264–75. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.01.010

26. Nanda AS, Nakao T. Role of buffalo in the socioeconomic development of rural Asia: current status and future prospectus. Anim Sci J. (2003) 74:443–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1344-3941.2003.00138.x

27. Akbar N, Nasir M, Naeem N, Ahmad M-D, Iqbal S, Rashid A, et al. Occurrence and seasonal variations of aflatoxin M1 in milk from Punjab, Pakistan. Toxins. (2019) 11:574. doi: 10.3390/toxins11100574

28. Hashmi HA, Belgacem AO, Behnassi M, Javed K, Baig MB. “Impacts of Climate Change on Livestock and Related Food Security Implications—Overview of the Situation in Pakistan and Policy Recommendations,” In; Emerging Challenges to Food Production and Security in Asia, Middle East, and Africa (Springer).

29. Ganesan S, Chandhirasekaran M, Selvaraj A. Ethnoveterinary healthcare practices in southern districts of Tamil Nadu. Ind. J. Tradition. Knowl. (2008) 7:347–54.

30. Rahman IU, Hart R, Afzal A, Iqbal Z, Ijaz F, Abd_Allah EF, et al. A new ethnobiological similarity index for the evaluation of novel use reports. Appl Ecol Environ Res. (2019) 17:2765–77. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1702_27652777

31. Xiong Y, Long C. An ethnoveterinary study on medicinal plants used by the Buyi people in Southwest Guizhou, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2020) 16:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s13002-020-00396-y

32. Pandey AK, Kumar P, Saxena MJ. “Feed Additives in Animal Health,” In Nutraceuticals In Veterinary Medicine (Cham: Springer). p. 345–62.

33. Leeflang P. Some observations on ethnoveterinary medicine in Northern Nigeria. Vet Q. (1993) 15:72–4. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1993.9694376

34. Hassan HU, Murad W, Tariq A, Ahmad A. Ethnoveterinary study of medicinal plants in Malakand Valley, district Dir (lower), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Ir Vet J. (2014) 67:1–6. doi: 10.1186/2046-0481-67-6

35. Rahman IU, Afzal A, Iqbal Z, Hart R, Abd_Allah EF, Hashem A, et al. Herbal teas and drinks: folk medicine of the Manoor valley, Lesser Himalaya, Pakistan. Plants. (2019) 8:1–18. doi: 10.3390/plants8120581

36. Khattak NS, Nouroz F, Rahman IU, Noreen S. Ethno veterinary uses of medicinal plants of district Karak, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. (2015) 171:273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.048

37. Bhardwaj AK, Lone PA, Dar M, Parray JA, Shah KW. Ethnoveterinary medicinal uses of plants of district Bandipora of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Int J Trad Nat Med. (2013) 2:164–78.

38. Kumar M, Rawat S, Nagar B, Kumar A, Pala NA, Bhat JA, et al. Implementation of the use of ethnomedicinal plants for curing diseases in the Indian Himalayas and its role in sustainability of livelihoods and socioeconomic development. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1509. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041509

39. Haq SM, Yaqoob U, Calixto ES, Rahman IU, Hashem A, Abd_Allah EF, et al. Plant resources utilization among different ethnic groups of Ladakh in trans-Himalayan region. Biology. (2021) 10:827. doi: 10.3390/biology10090827

40. Khan KU, Shah M, Ahmad H, Khan SM, Rahman IU, Iqbal Z, et al. Exploration and local utilization of medicinal vegetation naturally grown in the Deusai plateau of Gilgit, Pakistan. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2018) 25:326–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.07.012

41. Kulkarni S, Kulkarni DK, Deo AD, Pande AB, Bhagat RL. Use of ethno-veterinary medicines (EVM) from Vidarbha region (MS) India. Biosci Discov. (2014) 5:180–6.

42. Lans C, Turner N, Khan T, Brauer G, Boepple W. Ethnoveterinary medicines used for ruminants in British Columbia, Canada. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2007) 3:11. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-11

43. Mayer M, Vogl CR, Amorena M, Hamburger M, Walkenhorst M. Treatment of organic livestock with medicinal plants: a systematic review of European ethnoveterinary research. Complement Med Res. (2014) 21:375–86. doi: 10.1159/000370216

44. Hammond JA, Fielding D, Bishop SC. Prospects for plant anthelmintics in tropical veterinary medicine. Vet Res Commun. (1997) 21:213–28. doi: 10.1023/A:1005884429253

45. Farooq Z, Iqbal Z, Mushtaq S, Muhammad G, Iqbal MZ, Arshad M. Ethnoveterinary practices for the treatment of parasitic diseases in livestock in Cholistan desert (Pakistan). J Ethnopharmacol. (2008) 118:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.03.015

46. Dilshad SMR, Rehman NU, Ahmad N, Iqbal A. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices for mastitis in dairy animals in Pakistan. Pak Vet J. (2010) 30:167–71.

47. Zia-ud-Din S, Zafar I, Khan MN, Jonsson NN, Muhammad S. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices used for treatment of different ailments in a selected hilly area of Pakistan. Int J Agric Biol. (2010) 12:353–8.

48. Shoaib G, Shah G-M, Shad N, Dogan Y, Siddique Z, Shah A-H, et al. Traditional practices of the ethnoveterinary plants in the Kaghan Valley, Western Himalayas-Pakistan. Rev Biol Trop. (2021) 69:1–11. doi: 10.15517/rbt.v69i1.42021

49. Siddique Z, Shad N, Shah GM, Naeem A, Yali L, Hasnain M, et al. Exploration of ethnomedicinal plants and their practices in human and livestock healthcare in Haripur District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2021) 17:1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00480-x

50. Adnan M, Ullah I, Tariq A, Murad W, Azizullah A, Khan AL, et al. Ethnomedicine use in the war affected region of northwest Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2014) 10:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-16

51. Aziz MA, Adnan M, Khan AH, Sufyan M, Khan SN. Cross-cultural analysis of medicinal plants commonly used in ethnoveterinary practices at South Waziristan Agency and Bajaur agency, federally administrated tribal areas (FATA), Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. (2018) 210:443–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.09.007

52. Ali M, Aldosari A, Tng DYP, Ullah M, Hussain W, Ahmad M, et al. Traditional uses of plants by indigenous communities for veterinary practices at Kurram District, Pakistan. Ethnobot Res Appl. (2019) 18:1–19. doi: 10.32859/era.18.24.1-19

53. Rahman IU, Afzal A, Iqbal Z, Ijaz F, Ali N, Bussmann RW. Traditional and ethnomedicinal dermatology practices in Pakistan. Clin Dermatol. (2018) 36:310–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.03.016

54. Monteiro MVB, Bevilaqua CML, Palha M das DC, Braga RR, Schwanke K, Rodrigues ST, et al. Ethnoveterinary knowledge of the inhabitants of Marajó Island, Eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Acta Amaz. (2011) 41:233–42. doi: 10.1590/S0044-59672011000200007

56. Ijaz F, Rahman I, Iqbal Z, Alam J, Ali N, Khan S. “Ethno-ecology of the healing forests of Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, Pakistan: an economic and medicinal appraisal,” In; Plant and Human Health. Ozturk M, Hakeem KR, editors. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer International Publishing AG.

57. Nasir E, Ali SI. Flora West of Pakistan. University of Karachi, Karachi and National Herbarium, Islamabad (1971).

58. Ali SI, Qaiser M. Flora of Pakistan. Karachi: Department of Botany, University of Karachi (1995).

59. Ali SI, Nasir YJ. Flora of Pakistan. Islamabad: Department of Botany, University of Karachi, Karachi and National Herbarium (1989).

60. Ijaz F, Iqbal Z, Rahman IU, Alam J, Khan SM, Shah GM, et al. Investigation of traditional medicinal floral knowledge of Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, KP, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. (2016) 179:208–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.050

61. Rahman IU, Ijaz F, Afzal A, Iqbal Z, Ali N, Khan SM. Contributions to the phytotherapies of digestive disorders: traditional knowledge and cultural drivers of Manoor Valley, Northern Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. (2016) 192:30–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.049

62. Rahman IU, Ijaz F, Iqbal Z, Afzal A, Ali N, Afzal M, et al. Novel survey of the ethno medicinal knowledge of dental problems in Manoor Valley (Northern Himalaya), Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. (2016) 194:877–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.068

63. Friedman J, Yaniv Z, Dafni A, Palewitch D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J Ethnopharmacol. (1986) 16:275–87. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90094-2

64. Heinrich M, Ankli A, Frei B, Weimann C, Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers' consensus and cultural importance. Soc Sci Med. (1998) 47:1859–71. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00181-6

65. Khan MA, Ullah A, Rashid A. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants practices in district Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. Pak J Bot. (2015) 47:105–14.

66. Badar N, Iqbal Z, Sajid MS, Rizwan HM, Jabbar A, Babar W, et al. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices in district Jhang, Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci. (2017) 27:398–406.

67. Zerabruk S, Yirga G. Traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in Gindeberet district, Western Ethiopia. South African J Bot. (2012) 78:165–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2011.06.006

68. Rahman IU. Ecophysiological Plasticity and Ethnobotanical Studies in Manoor Area, Kaghan Valley, Pakistan (2020)

69. El-Saadony MT, Zabermawi NM, Zabermawi NM, Burollus MA, Shafi ME, Alagawany M, et al. Nutritional aspects and health benefits of bioactive plant compounds against infectious diseases: a review. Food Rev Int. (2021) 1–23. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2021.1944183

70. Rahman IU, Bussmann RW, Afzal A, Iqbal Z, Ali N, Ijaz F. “Folk Formulations of Asteraceae Species as Remedy for Different Ailments in Lesser Himalayas, Pakistan,” In; Ethnobiology of Mountain Communities in Asia. Abbasi AM, Bussmann RW, editors. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer International Publishing AG.

71. Gazzaneo LRS, de Lucena RFP, de Albuquerque UP. Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by local specialists in an region of Atlantic Forest in the state of Pernambuco (Northeastern Brazil). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2005) 1:9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-9

72. Addo-Fordjour P, Belford EJD, Akonnor D. Diversity and conservation of medicinal plants in the Bomaa community of the Brong Ahafo region, Ghana. J Med plants Res. (2013) 2:226–33.

73. Tadesse B, Mulugeta G, Fikadu G, Sultan A, Nekemte E. Survey on ethno-veterinary medicinal plants in selected Woredas of east Wollega zone, western Ethiopia. J Biol Agric Healthc. (2014) 4:97–105.

74. Birhanu T, Abera D. Survey of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants at selected Horro Gudurru Districts, Western Ethiopia. African J Plant Sci. (2015) 9:185–92. doi: 10.5897/AJPS2014.1229

75. Uniyal SK, Singh KN, Jamwal P, Lal B. Traditional use of medicinal plants among the tribal communities of Chhota Bhangal, Western Himalaya. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2006) 2:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-14

76. Sanz-Biset J, Campos-de-la-Cruz J, Epiquién-Rivera MA, Canigueral S. A first survey on the medicinal plants of the Chazuta valley (Peruvian Amazon). J Ethnopharmacol. (2009) 122:333–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.009

77. Ullah M, Khan MU, Mahmood A, Malik RN, Hussain M, Wazir SM, et al. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Wana district south Waziristan agency, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. (2013) 150:918–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.032

78. Vijayakumar S, Yabesh JEM, Prabhu S, Manikandan R, Muralidharan B. Quantitative ethnomedicinal study of plants used in the Nelliyampathy hills of Kerala, India. J Ethnopharmacol. (2015) 161:238–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.006

79. Erarslan ZB, Kultur S. Ethnoveterinary medicine in Turkey: a comprehensive review. Turkish J Vet Anim Sci. (2019) 43:55–582. doi: 10.3906/vet-1904-8

80. Poffenberger M, McGean B, Khare A, Campbell J. Community Forest Economy and Use Patterns: Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) Methods in South Gujarat, India, Volumes 1 and 2. Jt For Manag Support Program, Ford Found New Delhi (1992).

81. Iqbal Z, Jabbar A, Akhtar MS, Muhammad G, Lateef M. Possible role of ethnoveterinary medicine in poverty reduction in Pakistan: use of botanical anthelmintics as an example. J Agric Soc Sci. (2005) 1:187–95.

82. Chermat S, Gharzouli R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in the North East of Algeria-an empirical knowledge in Djebel Zdimm (Setif). J Mater Sci Eng. (2015) 5:50–9. doi: 10.17265/2161-6213/2015.1-2.007

83. Kumar VL, Roy S. Calotropis procera latex extract affords protection against inflammation and oxidative stress in Freund's complete adjuvant-induced monoarthritis in rats. Mediators Inflamm. (2007) 2007:047523. doi: 10.1155/2007/47523

84. Niwa Y, Miyachi Y, Ishimoto K, Kanoh T. Why are natural plant medicinal products effective in some patients and not in others with the same disease? Planta Med. (1991) 57:299–304. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960102

85. Bakhiet AO, Adam SE. Therapeutic utility, constituents and toxicity of some medicinal plants: a review. Vet Hum Toxicol. (1995) 37:255–8.

86. Longuefosse J-L, Nossin E. Medical ethnobotany survey in Martinique. J Ethnopharmacol. (1996) 53:117–42. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)01425-0

87. Aziz MA, Khan AH, Pieroni A. Ethnoveterinary plants of Pakistan: a review. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2020) 16:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13002-020-00369-1

88. Deeba F, Muhammad G, Iqbal Z, Hussain I. Appraisal of ethno-veterinary practices used for different ailments in dairy animals in peri-urban areas of Faisalabad (Pakistan). Int J Agric Biol. (2009) 11:535–41.

89. Luseba D, Van der Merwe D. Ethnoveterinary medicine practices among Tsonga speaking people of South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. (2006) 73:115–22. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v73i2.156

90. Meen ML, Dudi A, Singh D. Ethnoveterinary study of medicinal plants in a tribal society of Marwar region of Rajasthan, India. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. (2020) 9:549–54.

Keywords: ethnoveterinary practices, livestock, traditional medicine, Tribal Area, traditional knowledge, North Waziristan

Citation: Rehman S, Iqbal Z, Qureshi R, Rahman IU, Sakhi S, Khan I, Hashem A, Al-Arjani A-BF, Almutairi KF, Abd_Allah EF, Ali N, Khan MA and Ijaz F (2022) Ethnoveterinary Practices of Medicinal Plants Among Tribes of Tribal District of North Waziristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Front. Vet. Sci. 9:815294. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.815294

Received: 15 November 2021; Accepted: 04 February 2022;

Published: 25 March 2022.

Edited by:

Nora Mestorino, National University of La Plata, ArgentinaReviewed by:

Muhammad Zafar, Quaid-i-Azam University, PakistanKhalid Mehmood, Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan

Copyright © 2022 Rehman, Iqbal, Qureshi, Rahman, Sakhi, Khan, Hashem, Al-Arjani, Almutairi, Abd_Allah, Ali, Khan and Ijaz. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Inayat Ur Rahman, aGFqaWJvdGFuaXN0QG91dGxvb2suY29t

Sabith Rehman1

Sabith Rehman1 Rahmatullah Qureshi

Rahmatullah Qureshi Inayat Ur Rahman

Inayat Ur Rahman Niaz Ali

Niaz Ali Farhana Ijaz

Farhana Ijaz