- 1Neat Meatt Biotech Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, India

- 2Department of Basic Medical Science, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Khamis Mushayt Campus, King Khalid University (KKU), Abha, Saudi Arabia

- 3Atal Incubation Center, Center for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India

- 4National Research Centre on Mithun, Dimapur, Nagaland, India

- 5Department of Public Health, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Khamis Mushayt Campus, King Khalid University (KKU), Abha, Saudi Arabia

Cellular agriculture is one of the evolving fields of translational biotechnology. The emerging science aims to improve the issues related to sustainable food products and food security, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and provide animal wellbeing by circumventing livestock farming through cell-based meat (CBM) production. CBM exploits cell culture techniques and biomanufacturing methods by manipulating mammalian, avian, and fish cell lines. The cell-based products ought to successfully meet the demand for nutritional protein products for human consumption and pet animals. However, substantial advancement and modification are required for manufacturing CBM and related products in terms of cost, palatability, consumer acceptance, and safety. In order to achieve high-quality CBM and its production with high yield, the molecular aspect needs a thorough inspection to achieve good laboratory practices for commercial production. The current review discusses various aspects of molecular biology involved in establishing cell lines, myogenesis, regulation, scaffold, and bioreactor-related approaches to achieve the target of CBM.

1 Introduction

Proof-of-concept for large-scale production of cell-based meat (CBM) came into existence on live TV in 2013 when Prof Mark Post introduced the first-ever meat for consumption originated in the lab. The expansion of this technology, in combination with tissue engineering, has opened an avenue for the sustainable production of meat and meat products worldwide. In the coming decade, cellular agriculture is perceived as one of the important fields of biotechnology that may foster the world’s growing population by exploiting stem cell and tissue engineering without sacrificing an animal (Post et al., 2020). Global meat consumption continues to increase owing to upward population growth, a rise in economic status, and urbanization. Recently, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations anticipated the global demand for meat may extend to 455 million metric tons by 2050, while in 2005–06, it was 258 million tons (Alexandratos, 2012; Feeding the world in 2050 and beyond – Part 1: Productivity challenges, 2022).

Similarly, the consumption of fish is proposed to reach 140 million metric tons by 2050. Fish and seafood (crustaceans, mollusks, and other aquatic animals) support more than 20% of the global demand for the consumption of animal protein (Costello et al., 2020). Globally, more than 100 firms are developing their fish cell line or end product derived from fish line to manufacture CBM.

The majority of this increase is attributed to middle-income countries like India and China (FoodNavigator ASIA, 2022). The rising demand is challenging as the current livestock farming methods and aquaculture practices are linked to public health issues, environmental dilapidation, and animal welfare concerns. In the present review article, we mainly focus on molecular aspects of CBM which are currently being employed to establish cell lines and other molecular parameters such as transcription factors and muscle regulation.

2 Cell-based meat (CBM)

CBM has been recognized by many names, like cellular meat, cell culture meat, engineered meat, factory-grown meat, in vitro meat, fake meat, clean meat, neat meat, synthetic meat, lab-grown meat, and artificial meat. CBM is an emerging field of biotechnology that aspire to solve the greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), depletion of water bodies, cutting down grassland and forest land, and antibiotics misuse. A report from the FAO claims that the livestock segment is responsible for 14.5% of GHG emissions, blows out the earth’s terrain (approximately 30%), and 8% of global freshwater (Gerber, 2013). From a source published by Our World in Data, India is the third largest country in GHG emissions. GHG emissions arise from electricity generation, infrastructure expansion, and animal agriculture. With the worldwide population probably double by 2050, the quest to reduce GHG emissions and augment a cheap source of protein in the form of livestock meat will be a daunting task and unable to support the growing demand. It is imperative to look for a sustainable system that emits minimum GHG, needs less water, requires minimum land space, and has minimum antibiotic use. In the United States, livestock animals mainly use 70%–80% of antibiotics (mainly used directly or indirectly by livestock animals to produce meat (CGDEV, 2022). Conventional livestock farming has led to regular misuse of antibiotics and, thereby, the selection of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) strains, posing significant health issues (Avesar et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2017). In 2015, colistin AMR originated in farms of pigs and was subsequently detected in chickens and other farm animals in South America (Nguyen et al., 2016; Monte et al., 2017; Reardon, 2017). Recent research predicted, AMR will be more accountable for deaths than cancer by the year 2050 (The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2012).

Excessive livestock farming and growing animal welfare ethics have recently pushed traditional meat production into the back seat. Another primary concern of livestock farming is a foodborne disease from swine and avian influenza (Greger, 2007). Some common microorganisms found in the meat are Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Campylobacter (Anomaly, 2015). CBM production in a sterile condition may check these troubles and improve food safety and security. Animal ethics and slaughtering animals are other aspects that drive toward CBM (van der Weele and Driessen, 2013; Sharma et al., 2015). The scientific community respects farm animals and their sentient beings with physical and psychological needs (Egg-Truth, 2022).

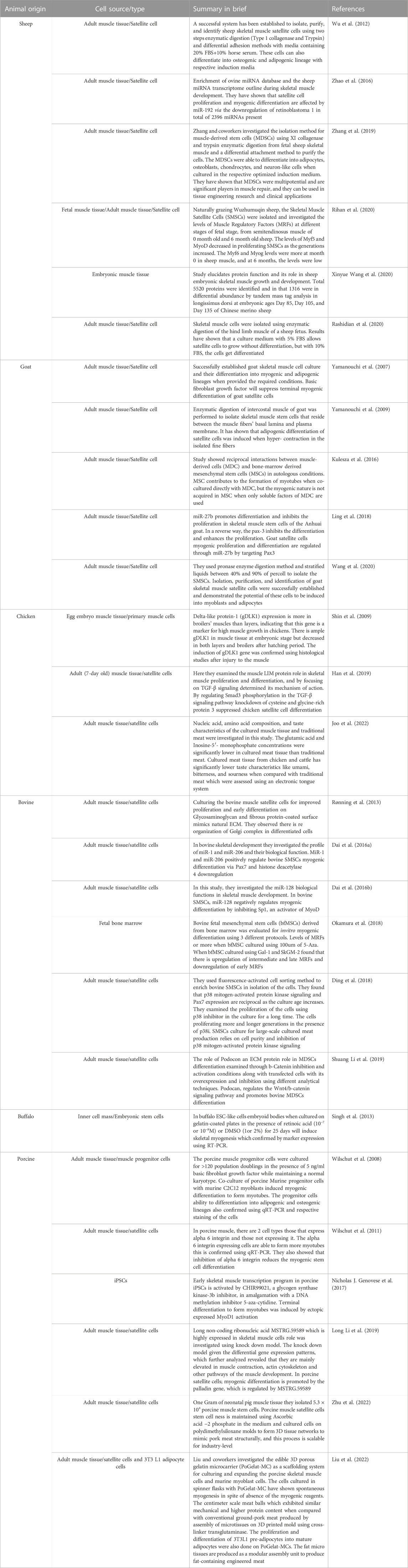

In the present review article, we aim to discuss various parameters of CBM, starting from the cell line establishment, feasibility, scaffolding, safety of CBM, regulatory framework, affordability, acceptability, and other aspects in detail. Figure 1 describes the general concept and methodology utilize to manufacture CBM of different species (chicken, fish, and mammals).

FIGURE 1. Schematic diagram showing the methodology of CBM production exploiting cells of chicken, fish, and mammalian species.

2.1 Stem cell

Stem cells are unspecialized cells possessing self-renewal capacity, and the discovery of stem cells paved the way for in vitro cell production and the concept of cultured meat. These cells have the potential to divide through mitosis to renew to other cell types throughout the life span of the multicellular organism. Subsequently, stem cell divides to create a cell population that can either stay as stem cells or separate lineage with more characterized capabilities such as blood, muscle, and neuronal cells. Usually, there are two types of stem cells, i) embryonic stem cells and ii) undifferentiated/substantial/grown-up stem cells. The embryonic stem cell is determined from the embryos, while undifferentiated cells reside in a tissue or organ at the side of other divided cells. The basic three properties of the stem are i) capable of dividing and renewing, ii) unspecialized, and iii) differentiate to other cell types. The cell typically passes through various stages during differentiation and specializes at each step. The signals that trigger the differentiation process inside and outside stem cells are still to be deciphered. The epigenetic regulation of genes typically controls the internal signal, while external signals such as physical contact with neighboring cells, growth factors or chemicals (specific to various receptors of stem cell) secreted by other cells, and the microenvironment are the main driving force for stem cell differentiation.

Pluripotent stem cells are difficult to handle and culture for CBM research as they require more time and resources to proliferate and differentiate into mature cell types compared to primary adult stem cells. Nevertheless, a pluripotent stem cell has the inherent capability to increase in large numbers and become immortal. Pluripotent stem cells derived from non-muscle sources can be isolated from diverse domesticated animals and expanded as a myogenic cell source for CBM. Recently, chemically and genetically modified porcine pluripotent stem cells have been transformed into myogenic cells possessing the ability to differentiate into embryonic muscle fibers (Genovese N. J. et al., 2017). Pluripotent muscle stem cells are attractive possible source cells; any CBM produced from these pluripotent cells must be appropriately screened for safety before consumption.

On the other hand, primary adult stem cells offer the benefit of being simply achieved from a biopsy of any animal species, such as sheep, buffalo, or cow, to acquire a cell population for any meat product; however, their proliferative potential is limited (Ding, 2019). Depending on the stem cell types, these cells can be stimulated to differentiate into muscle or fat cells. MSCs are considered reliable cells for skeletal muscle recovery in vivo, and their self-renewal capability maintains the population of stem cells and the generation of enormous numbers of myogenic cells. These myogenic cells proliferate, divide, fuse, and help produce new myogenic fibers (Brack and Rando, 2012; Yin et al., 2013). Mark post presented the meat hamburger prototype that amplifies the myoblast progeny of MSCs (Post, 2014). Multipotent progenitor cells deriving from porcine skeletal muscle exhibit higher doubling capacity than MSCs, presenting them as better source cells for CBM production. However, these cells require additional growth factors and are not able to differentiate into skeletal muscle fibers as proficiently as MSCs can perform (Wilschut et al., 2008).

2.2 Starting material for CBM

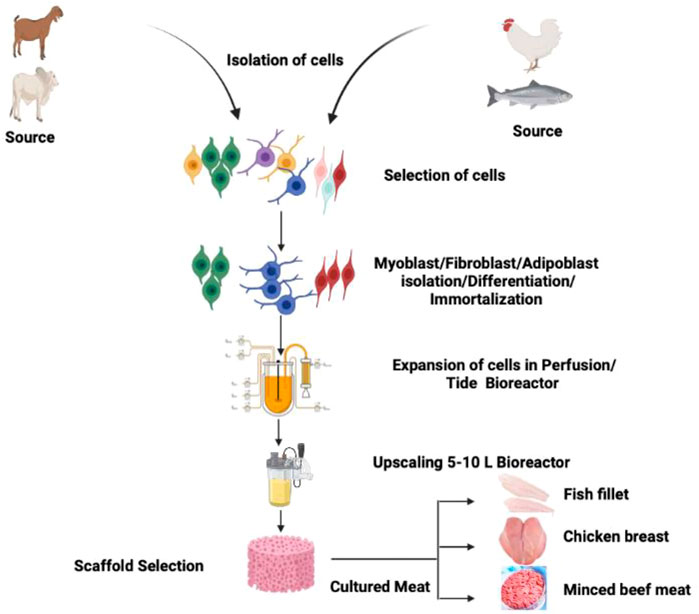

In 1961, Mauro first identified the bona fide satellite cells in frogs (Mauro, 1961). On appearance, satellite cells differ from muscle fiber in exhibiting chromatin-dense nuclei with minute cytoplasmic value. Satellite cells derive from the dermomyotome’s cell population and are between the basal membrane and sarcolemma (Gros et al., 2005). Satellite cells add new nuclei in the growing muscle fibers by fusing with adjacent fibers during peri- and postnatal development (Relaix et al., 2005; Biressi et al., 2007). Afterward, satellite cells may acquire a quiescent stage. Upon muscle injury, they are activated for further muscle growth and development (Biressi et al., 2007; Fu et al., 2015; Almada and Wagers, 2016). A preplating procedure usually isolates bovine satellite cells (Li et al., 2011; Will et al., 2015). The purity of isolated satellite cells through the preplating method without further purification steps can lead to 31% of cells (depending upon the fusion index) and 95% by DESMIN staining (Coles et al., 2015; Will et al., 2015). The purification of satellite cells may be improved by FACS/MACS and in combination with positive selection (CD29 and CD56) and negative selection (CD31 and CD45) (Figure 2). However, the degree of high positivity may be deduced by their PAX7 positivity (Ding et al., 2018).

FIGURE 2. Isolation and purification of muscle stem cells. FACS and MACS methods can isolate muscle stem cells from the mixed population of cells exploiting cell-surface specific markers (Guan et al., 2022).

The mainstay material for producing CBM is myoblasts (satellite cells), which are challenging to grow in vitro. However, myoblasts can readily differentiate into myotubes (immature muscle cells) and myofibrils under specific environments. To expedite the replication of skeletal muscle satellite cells in a lab, cells are attached to an immobile substratum, for example, scaffold or microbeads, which may be coated with protein (collagen, chitosan, and laminin) to imitate the natural tissue. The scaffolds are usually biodegradable, edible, and re-usable during the culture method (Stephens et al., 2018).

Nutrient-rich medium is essential for growing satellite cells to provide a unique proliferation and differentiation phase, comprising antibiotics, antimicrobial agents, antifungal agents, and other chemicals to prevent contamination. Culture media is typically optimized with varying amounts of fetal bovine serum (5%–10%) to optimize the growth and differentiation of satellite cells in vitro. Some laboratories designed serum-free media or chemically-defined media for culturing the satellite cells; however, these media components are expensive and possess proprietary issues (Edelman et al., 2005).

Muscle cell culture implicates significant challenges on an industrial scale in a large bioreactor. Stephens et al. reported that roughly eight trillion muscle cells are required to produce 1 kg of protein from a traditional bioreactor possessing a capacity of 5000 L (Stephens et al., 2018). Cultured muscle cells may reach a thickness of around 200 μm. In the thick muscle layer, oxygen and essential nutrients may not be able to penetrate the inner layer of cells, and due to an insufficient supply of oxygen and nutrients, cells may begin to die (Jones, 2010). Muscle strips are harvested and processed at this stage, and several supplementary chemical compounds are added to augment nutritional value, color, texture, and flavor. The production of a particular cut of meat, like chops, steaks, or roasts, needs additional technology to give the correct shape and structure to the muscle cells.

The paraxial mesodermal progenitor cells during fetal development give rise to muscle tissue. Upon sequential development process, paraxial mesoderm differentiates into myoblast, and the ensuing process is regulated by numerous growth factors (Chal and Pourquié, 2017). Through cell-to-cell fusion, myoblast generates muscle tissue, and part of them inhabits underneath the basal lamina of myofiber, which converts into quiescent satellite cells during the postnatal period. During muscle injury, the quiescent muscle cells are activated to differentiate into myoblast, leading to muscle regeneration. The quiescent satellite cells are characterized by the expression of Pax7, while Myf5 and MyoD are absent (Kuang et al., 2007). Upregulation of Myf5 and MyoD and downregulation of Pax7 occur by myogenic satellite muscle cells and make them proliferating myoblast during muscle injury. Myf5 plays a significant role in myoblast proliferation, while MyoD has a principal function in differentiation (Asakura et al., 2007; Gayraud-Morel et al., 2007). These intrinsic factors can be exploited as muscle stem cell markers to explore the cellular states of the cell. Muscle stem cells possess surface and cytoskeletal proteins, for example, vascular cell adhesion molecule, neural cell adhesion molecule (also known as CD56), integrin α7, β1 (CD29), CD34, desmin, and SM/C-2.6 (Wang et al., 2014). The synchronization of intrinsic and extrinsic factors plays a significant role in the fate of muscle stem cells. Hence, to maintain the functioning of muscle stem cells in the lab, the physiological conditions of muscle stem cells should be provided by mimicking the in vivo stem cell niche in the form of extracellular matrix (ECM) and paracrine factors.

2.3 Composition of muscle tissue

Skeletal muscle tissue comprises muscle fibers, connective tissues, and stem cell populations. Muscle stem cells usually reside on muscle fibers, and their isolation is a mainstay in upscaling in cellular agriculture, as described in the previous sections. Commonly used proteases for the purification of muscle stem cells are from muscle biopsy following physical dissociation, and meat mincing are trypsin, collagenase, pronase, and dispase. Numerous digestive enzymes with multiple combinations can be applied to digest muscle tissues. Collagenase and dispase have been extensively used as these enzymes specifically target ECM-containing collagen and fibronectin (Stenn et al., 1989).

2.3.1 Muscle fibers

The hallmark of any muscle fibers are due to their contractile properties (Klont et al., 1998; Lefaucheur, 2010). The contractility mainly depends on the amount of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms embedded within the thick filaments. Generally, mammalian skeletal striated muscles contain four types of MyHCs: I, IIa, IIx, and IIb. The speed and level of contraction of MyHCs depend on the ATPase activity, i.e., type I is slow while type IIa, IIx, and IIb are fast. Muscle fibers are dynamic in nature and can switch from one type to another and follow the pathway: I↔IIa↔IIx↔IIb (Meunier et al., 2010). Type I fibers show low-intensity contraction, are resistant to fatigue, and are found in respiratory and postural function muscles.

Strong expression of MyHC IIb was found in the skeletal muscle of pig breeds while absent in sheep horses (Lefaucheur et al., 1998; Picard and Cassar-Malek, 2009). Depending upon the species, muscle fiber composition determines one of the critical factors of meat quality. The fiber composition varies from species to species; for example, pig Longissimus muscle possesses roughly 10% type I fibers, 10% type IIa, 25% IIx, and 55% IIb. Longissimus of bovine contains approximately 30% type I, 18% IIA, and 52% IIx. The factors determining muscle fibers’ composition are breed, gender, age, physical activity, environmental condition (temperature), and feeding practices.

2.3.2 Connective tissue

The connective tissue primarily surrounds muscle fibers and fiber bundles and consists of cells and ECM comprising a composite network of collagen fibers enveloped in a matrix of proteoglycans (Abbott et al., 1977; Lawrie, 1989; Lefaucheur et al., 1998). Based on collagen type, the basic structural unit of collagen, tropocollagen, is a helical structure comprising three polypeptide chains coiled around one another to give a spiral structure. Interchain bonds stabilize the tropocollagen and form a fibril-like structure of 50 nm diameter. These fibrils are again stabilized by hydrogen and disulfide (intramolecular) or intermolecular bonds such as pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline. These pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline are known as crosslinkers. Various types of collagen found in skeletal muscles are fibrillar collagen I and III, abundant in mammals. While in fish, collagen I and IV predominate (Sato et al., 1991). Apart from collagen, the other components found in connective tissue are proteoglycans (PGs) (Nishimura, 2015). PGs are multifarious molecules consisting of core proteins in the range of 40–350 kDa. PGs are joined by covalent bonds to numerous dozen glycosaminoglycan chains, forming large complexes by attaching to other PGs and fibrous proteins. Glycosaminoglycans are negatively charged and bind with cations such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, and water (Iozzo and Schaefer, 2015). The degree of intramuscular collagen crosslinking varies according to species, muscle types, genotypes, age, sex, and extent of physical exercise (Purslow, 2005). Collagen content differs from 1% to 15% of the muscle dry weight in adult cattle, 1.3 (Posa major) to 3.3% (Latissimus dorsi) of dry weight muscle in large while pigs for commercial slaughter stage. In the dry weight of poultry, only 0.75%–2% of the collagen was found (Liu et al., 1996), while variable content of collagen is reported in fish, depending upon the species (1%–10% between sardines and congers) (Sikorski et al., 1984; Sato et al., 1986).

2.3.3 Intramuscular fat

In fish, fat is present in subcutaneous positions and within the perimysium, myosepta. Myosepta contribute to the significant part of flesh and determine the quality of flesh. Intramuscular fat predominantly consists of structural lipids, phospholipids, and storage lipids (triglycerides). Approximately 80% of the triglycerides are stored in the muscle adipocytes between fibers and bundle fibers, and 5%–20% is stored as lipid droplets inside myofibers in the cytoplasm (Essén-Gustavsson and Fjelkner-Modig, 1985). The content of phospholipid is relatively constant at 0.5%–1% of the fresh muscle of pigs; however, muscle triglyceride content is highly variable depending upon the species (Wood et al., 2008; Shingfield et al., 2013). The size and number of intramuscular adipocytes determine the intramuscular fat content. The interindividual disparity in intramuscular fat content of a particular muscle between animals of comparable genetic makeup has been connected with variation in the intramuscular adipocyte in pigs and cattle. On the other hand, variation in the intramuscular fat content of a particular muscle of the same genetic origin in animals raised in different dietary components has shown differences in the size of adipocytes (Gondret and Lebret, 2002). In fish, the upsurge in myosepta width is possibly associated with an increase in the size and number of adipocytes (Weil et al., 2013). The intramuscular fat content also fluctuates depending upon the muscle origin, genotype, age, breed, diet, and the rearing conditions of the livestock (Mourot and Hermier, 2001; Lebret, 2008; Bonnet et al., 2010; Hocquette et al., 2010; Shingfield et al., 2013). Chinese pigs (Meishan), American pigs (Duroc), and European local pig breeds (Iberian and Basque) possess higher contents of intramuscular fat as compared to European conventional genotypes, for example, Large White, Pietrain, and Laandrace (Bonneau and Lebret, 2010). Fresh Longissimus muscle of conventional genotypes of pigs slaughtered at commercial slaughterhouses have intramuscular fat in the range of 1%–6% and sometimes up to 10% in certain breeds (Lebret, 2008). Longissimus muscle of cattle, the intramuscular fat content varies from 0.6% in Belgian Blue to 23.3% in Black Japanese at 24 months of age (Gotoh et al., 2009). It has been noticed in French cattle breeds that selection on muscle mass is strongly connected with a decrease in collagen and intramuscular fat content. Popular breeds such as Charolaise and Blonde d’Aquaintaine possess less intramuscular fat content compared with a hardy breeds such as Aubrac and Salers (Schreurs et al., 2008). The intramuscular fat content also varies in fish between species, such as ‘lean’ species carrying 3% (cod), while fatty species contain more than 10% (Atlantic salmon) (Hocquette et al., 2010).

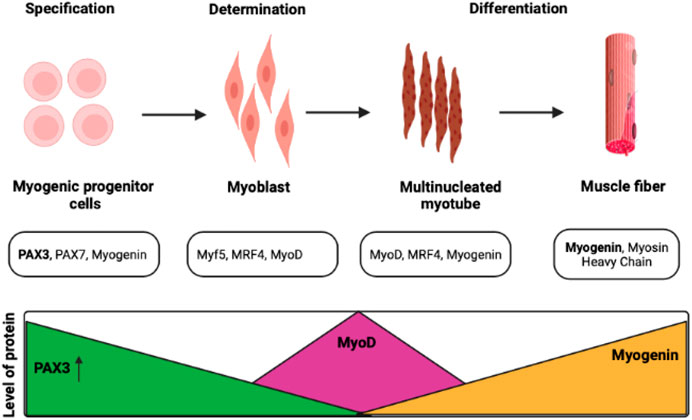

2.4 Myogenesis and regulation

Myogenesis is a highly ordered and complex process of MSCs. The process is regulated by the co-expression of paired box transcription factors (Pax3/Pax7) and myogenic regulatory factors (such as Myf5, Mrf4, MyoD, and myogenin) (Zammit and Beauchamp, 2001; Relaix et al., 2005; Baig et al., 2019). Myogenesis is illustrated by various factors such as cell cycle arrest, increased nuclear sizes, cell alignment, myogenic activation, multiple cell fusion, and peripheral localization (Chargé and Rudnicki, 2004). However, skeletal muscle regeneration depends on interactions between MSCs and their microenvironment composed of basal lamina and sarcolemma (Kuang et al., 2008).

Animal meat is composed of skeletal muscle tissues, so tissue engineering of skeletal muscle tissues has been exploited to produce CBM. Due to the non-proliferating capability of adult skeletal muscle cells, MSCs are utilized as a precursor for replication. MSCs exhibit high responsiveness and migratory abilities; MSCs are precarious for preserving skeletal muscle’s functional and structural integrities and are also accountable for muscle regeneration through a coordinated myogenic program (Lee et al., 2018). The discoveries of MSCs led to the production of cells in vitro and the development of CBM. Therefore, MSCs provide a viable source of cells for skeletal muscle recovery (in vivo). The ability of MSCs to self-renew and self-sustain the stem cell population and the production of an enormous number of myogenic cells, which again proliferate, multiply, and fuse to form new myofibers (Shaikh et al., 2021). MSCs are typically located between the basal lamina and sarcolemma and are active in regulating myofiber growth and development under the influence of myogenic regulatory factors (Ahmad et al., 2020; Shaikh et al., 2021). The first CBM production model was established on bovine MSC, and the principle is still applied in bioreactor-based cultured meat production (Verbruggen et al., 2018). In the following sub-section, we discussed the molecular parameters involved in the regulation of muscle and development.

2.4.1 Pax3

Paraxial mesoderm gives rise to skeletal muscle in the trunk and limbs and subsequently segments into repetitive epithelial structures termed somites. Pax3 has already been transcribed in the pre-somitic mesoderm stage adjoining the first somite and afterward newly formed somites (Schubert et al., 2001). As time progresses, somite matures, and the ventral domain endures an epithelial to mesenchymal transition, subsequently down-regulating Pax3 and activating pax1/9 to form the sclerotome. The sclerotome forms the cartilage and bone of the vertebral column and ribs, while the neighboring subdomain forms the tendon. The dorsal domain of somite maintained its epithelial structure and termed it a dermomyotome. Pax3 expression is now limited to dermomyotome and remains present in myogenic progenitor cells, which delaminate and travel from the somite to other distant parts, such as the limb, during the myogenesis (Goulding et al., 1991; Buckingham and Relaix, 2007). Myotome, the first differentiated skeletal muscle, forms within the central domain of the somite (under the dermomyotome) and functions as a scaffold for successive waves of cells of myogenic origin. Subsequently, myogenic cells activate the myogenic determination genes, such as Myf5, MRF4, and MyoD, and delaminate from the edges of the dermomyotome. At the same time, there is a downregulation of Pax3. The epaxial part of the myotome forms a deep back muscle, and the hypaxial myotome gives rise to the muscle of the body wall and trunk. The level of Pax3 expression is high in the hypaxial domain of the dermomyotome (Bober et al., 1994; Relaix et al., 2004).

The Pax3 gene codes for the Pax3 protein and is characterized by a highly conserved paired box motif. The Pax3 gene is also known as WS1, WS3, CDHS (Craniofacial-deafness-hand syndrome), and HUP2). The PAX family of transcription factors is characterized by a highly conserved pair of DNA binding domains, and it was first identified in Drosophila segmentation genes (Tremblay and Gruss, 1994). Based on the similar functional organization and degree of sequence homology, humans and murine possess nine Pax members (Pax1-Pax9) and comprise a subfamily called group III (Stuart et al., 1994).

Transcriptome study ascertains the related developmental gene expression pattern between cattle and mice. Just after the commencement of gastrulation (day 14 of the embryonic stage), Pax3 mRNA is identified in the bovine conceptus, indicating the initial stages of mesoderm formation (Pfeffer et al., 2017). In this stage, only Pax3 is visible and detected, while Myf5 (myogenic factor 5), MyoD (myogenic differentiation factor D), MRF4 (myogenic regulatory factor 4), and Pax7 are not detected. Somites are visible by day 21 of the embryonic stage and evident with 5 and 14 somite pairs (Maddox-Hyttel et al., 2003; Richard et al., 2015). On day 23 of gestation, at least 24 pairs of somite pairs are visible, comprising presumptive forelimb bud, otic and optic placodes as well as five visible branchial arches (Gonzalez et al., 2020).

2.4.2 Pax7

Pax7 (paired box 7) is one of the satellite cell’s mainstay homeobox-containing transcription factors and lineage markers (Seale et al., 2000). Proliferating mouse satellite cells exhibit the expression of Pax7 and are typically absent in myotubes. Pax7 is also expressed in the dermomyotome and presumptive myoblast with a partially overlapping expression pattern of Pax3 in the mouse embryo (Relaix et al., 2004; Horst et al., 2006). The subpopulation of satellite cells also expresses Pax3; however, Pax3 is unable to substitute for Pax7 either in adult muscle precursor cells or embryonic stage (Conboy and Rando, 2002; Relaix et al., 2004; Kuang et al., 2006). Transcriptome studies reveal that similar gene expression patterns exist between mice and cattle. On an embryonic day 14, Pax3 mRNA is identified in the bovine conceptus indicating the initial stages of mesoderm formation, while Myf5, MyoD, MRF4, myogenin, and Pax7 are not expressed (Pfeffer et al., 2017). By embryonic day 21, somites are apparent (5–14 pairs) (Maddox-Hyttel et al., 2003; Richard et al., 2015) and near gestation day 23, at least 24 pairs of somites are visible, including a presumptive forelimb bud, five visible branchial arches, otic and optic placodes. These developmental and morphological characteristics are equivalent to a Hamburger Hamilton (HH) stage 21 chick embryo and embryonic 9.5 days in the mouse (Hamburger and Hamilton, 1951). The presence of MyHC myotome suggests MRF expression within the dermomyotome at the time of the developmental window covering days 14–23 of the gestation period. Demonstration of cryosection and their analysis indicates the presence of Pax7 immunopositive cells within the dermomyotome. As the gestation time increases, the number of Pax7 continues to decline (Gonzalez et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015). Satellite cells isolated from the semitendinosus muscle of neonatal calves express the combination of Pax7 and Myf5 (Li et al., 2011). Satellite cells isolated from longissimus 4–6 week-old pigs possess a large amount of Pax3 immunopositive cells (Sebastian et al., 2015). It is still not known why satellite cells have such a diverse population of cells. Scientists are pondering and tempted to speculate that the total number of muscle fiber increase during the development process (Bérard et al., 2011).

2.4.3 Presence of Pax3 and Pax7 in adult skeletal muscles

Pax3 and Pax7 are two closely related transcription factors in the maintenance of progenitors of skeletal muscle lineage (Chi and Epstein, 2002; Robson et al., 2006). In the late fetal stage, myogenic progenitor cells comprising Pax3/7-positive cells start taking a position on the muscle fibers beneath a basal lamina (Gros et al., 2005; Kassar-Duchossoy et al., 2005; Relaix et al., 2005). This is the hallmark niche of myogenic progenitor cells (so-called satellite cells) of adult muscle which determine muscle regeneration (Montarras et al., 2013). Adult satellite cells are quiescent, while fetal and postnatal myogenic progenitor cells divide actively. The quiescent satellite cells undergo quick activation on account of injury or in tissue culture experiments. Under these circumstances, there is marked upregulation of the myogenic determination factor (MyoD), downregulation of Pax7, activation of myogenin, and muscle fiber differentiation.

Previously, satellite cells have been isolated from single fiber and exploiting flow cytometry of Pax3-positive satellite cells from the trunk muscle of Pax3GFP/+ mice (Collins et al., 2005; Montarras et al., 2005). The capacity of these cells was found to be efficient in self-renewal in vivo. Satellite cells marked by Pax7 expression are necessary for the regeneration of muscle (Tedesco et al., 2010).

Pax3 and Pax7 have also been investigated for promoting cell survival, proliferation, and regulating the skeletal muscle program in various time intervals, such as during embryogenesis, postnatal development, and adulthood (Buckingham and Relaix, 2015). During embryogenesis, Pax3 functions as an antiapoptotic, preferably in the hypaxial somite (Borycki et al., 1999). Double mutant of Pax3/Pax7 exhibited the importance of these transcription factors, and most of the myogenic cells in the somite lost, and at the same time, muscle failed to form (Relaix et al., 2005). After parturition, satellite cell experience apoptosis in the Pax7, even in the diaphragm muscles where Pax3 is expressed (Relaix et al., 2006).

2.4.4 MyoD

The transcription factors of MRFs have a role to play in the progression of muscle in vertebrates and are expressed temporally in muscle tissue in a regulated way. This is due to the presence of the E box, which is a DNA consensus sequence “CANNTG” (Dechesne et al., 1994). The MRFs such as MyoD, MRF4, Myf5, and Myogenin work in an interdependent regulatory and cascading manner (Liu et al., 2010).

The very first MRF to be discovered was myoblast determination protein 1 (MyoD). This discovery used in the differentiation of myocytes as MyoD during the differentiation process showed sequence regulatory gene expression (Hernández-Hernández et al., 2017). MyoD and myogenin are widely used as a marker of differentiation in myogenic development. MyoD is the well-known and verified transcription factor in the development of the myogenic cell-lineage specification. In small vertebrates, the phylogenetic study on amino acids showed more than 50% similarity between MyoD and Myf5 before differentiation (Megeney and Rudnicki, 1995). Among these regulators, MRF4 was highly expressed in mature myofibers (Zammit, 2017). MyoD is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that plays a significant role in skeletal muscle development.

The activation, differentiation, and proliferation mechanisms are regulated in an orchestral manner. This activation depends on the consensus sequence E-box and E proteins such as E47. A higher binding affinity of MyoD-E47 to the dsDNA bHLH domain was observed during the mammalian muscle cell activation (Zhong et al., 2022). As discussed, the Pax7 shows positive expression during the cell cycle’s G0 phase (quiescent stage) in the myogenic stem cells or satellite cells (SCs). At this stage, along with Pax7, 90% of these cells express Myf5 and are therefore selected to form myogenic cells. After the activation of these SCs with various growth factors and signaling pathways, such as Ras-Erk, TGF-β, Notch, JAK-STAT, and HGF, the expression of MyoD can be detected. In the proliferation stage, the MRFs, myogenin, and MRF4 showed their expression (Asfour et al., 2018). Although the muscle tissue-specific genes reside in different chromosomal loci, they work in a much-regulated manner both during embryogenesis and in culture cells. Therefore in this regulated mechanism, the chromatin remodeling enzymes, a subunit of SW1/SNF, activated Brg1 and MyoD play an essential role in making inter-chromosomal interactions (Harada et al., 2015). As mentioned before, these MRFs are regulated through various factors. One such study by Latimer and coworkers revealed that the lack of methionine downregulated the MyoD and myogenin expression and obstructed the differentiation of fish muscle cells (Latimer et al., 2017). Another transfection study revealed that the MRFs, after introducing into the cells, fibroblast expressed muscle-specific genes compared with hepatocytes (Schäfer et al., 1990). In a mouse model, scientists have proved that MyoD also functions as a genome organizer in muscle cell development (Wang et al., 2022). In bovine skeletal muscle development, the transcriptional regulation is different, which includes additional genes such as Myoz2, confirmed by siRNA interference techniques (Wei et al., 2022).

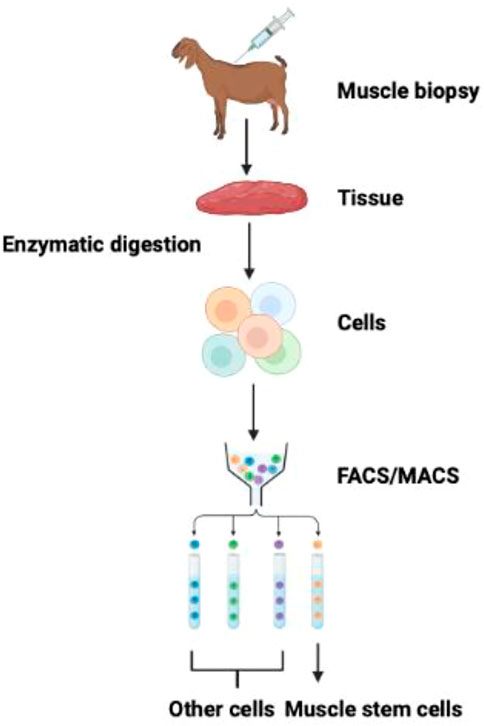

2.4.5 Myogenin

Myog is also a crucial gene during the terminal differentiation of muscle development. The regulation of differentiation in pluripotent P19 cell lines was observed with the association of the MEF2C (myocyte enhancer factor 2C) gene. This gene triggers the increment of expression of Myog more than 20 folds and takes part in the positive regulation of these cells (Ridgeway et al., 2000). Along with muscle development, Myog also regulates neurogenic atrophy with the help of other associated TFs such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) 4 and 5 (Moresi et al., 2010). The epigenetic regulation of Myog has also been observed during muscle development at the larval stage in Atlantic salmon (Burgerhout et al., 2017). In general, the histone modification enzymes, chromatin remodelers, cofactors, and other specific TFs have a role to play in the regulation of muscle proliferation to differentiation from the quiescent stage. In the mouse model, the development of the sternum and rib was also visible other than muscle development, and the deletion of the Myog gene exhibits muscle scarcity and lethality (Vivian et al., 1999; Meadows et al., 2008). This observation supports a study that revealed the critical function of Myog in skeletal muscle development. The mutation in Myog in mice showed muscle scarcity and death instantly after birth; however, the mutation in other MRFs does not show such results (Hasty et al., 1993). Figure 3 depicts the comparative roles of various myogenic factors during myogenesis.

FIGURE 3. Transcription factors control myogenesis at various stages. Satellite cells proliferate, differentiate, and renew the population of progenitor cells to maintain muscle function (Darabi and Perlingeiro, 2008; Olguín and Pisconti, 2012).

2.4.6 Myogenic factor 5

Myf5 is considered the early expressed gene with MyoD, and its crucial function in the commitment and proliferation of the cells that direct the myogenic process (Giordani et al., 2007). Myf5 is vital for the satellite cells in the initialization of the myogenesis process. The double mutant of the MYF5 study confirms its importance in the formation of muscle dystrophy, although the mice were not lethal (Ustanina et al., 2007). Myf5 has a role to play in chromatic remodeling, which provides access to other associated TF factors to be activated (Gerber et al., 1997). At least six distinct sequences control myf5 expression in the somite, and even within a presumably uniform structure like the myotome, more than one regulatory module is necessary (Hadchouel et al., 2003). From a gene homology point of view, the Myf5 gene is well conserved between fish and mammals (Ustanina et al., 2007). In recent research on rat skeletal muscle cells, compressive stress has a time-dependent effect on how Myf5 expression is regulated. They found that on prolonged stress stimulation, the expression of Myf5 and MyoD genes was downregulated (Lu et al., 2020). The course of feeding pattern (under-feeding, long-term under-feeding, and re-feeding) in sheep provided a differential expression pattern of myokines, MRFs, and TFs, where Myf5 transcript showed an overexpression (Jeanplong et al., 2003). A study concluded that the factors governing adult Myf5 expression can be genetically distinguished from those governing Myf5 during development and may even be different (Zammit et al., 2004).

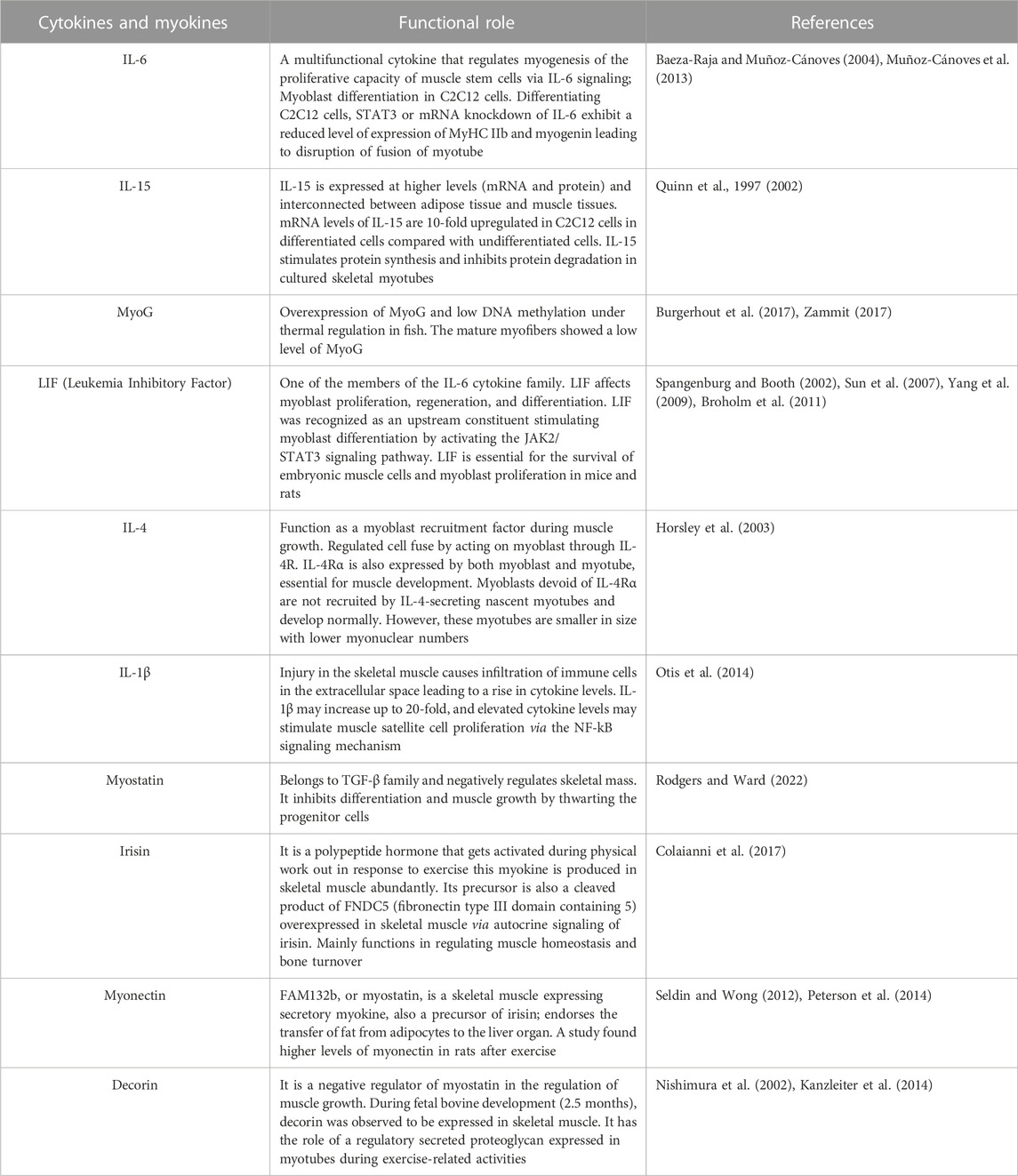

2.5 Functions of myokines in skeletal muscles

Myokine is a cytokine comprising a molecular weight in the range of 5–20 kDa. During muscle contraction, skeletal muscle cell produce and release myokines. Table 1 briefly describes the function of myokines and cytokines implicated in myogenesis.

3.1 In vitro culture of muscle cells

In vitro stem cells need a culture environment like growth media, cell substrates, antibiotics, antimycotic agents, and incubators. The culture environment provides optimum in vitro niche conditions to grow cells, mimicking in vivo (ECM, hormones, and cytokines). Recapitulations of media components are performed by exploiting synthetic chemicals and artificial devices. In the next section, we will discuss i) media, ii) cell substrates, iii) serum and their replacements, iv) antibiotics, and v) additional nutrients and supplements.

3.2 Extracellular matrix (ECM)

ECM is a multilayered environment that provides structural support, signals responses to injuries, helps cellular communication, and presents architectural preservation of skeletal muscle cells. During myogenesis, ECM interacts with, adheres to, safeguards muscle cell, assist in biochemical signaling, and offers structural support (Lee et al., 2018). Some of the ECM proteins assist in cell-matrix interactions and matrix assembly regulation (Gillies and Lieber, 2011). Besides its biological function, ECM comprises nutrients such as proteins (collagen) and glycosaminoglycans that impact the texture of tissue and overall meat quality (Table 2) (The Good Food Institute, 2022).

In myotubes’ developmental regulation during myogenic differentiation’s early stages, ECM is essential in regulating MSC’s phenotypic expression (Zhang et al., 2021). The basal lamina comprises a three-dimensional ECM network and is directly linked to MSC (Kuang et al., 2008). The majority of ECM comprises collagen fibers and proteoglycan matrix; however, ECM also contains elastin, fibronectin, and laminins (Thorsteinsdóttir et al., 2011). Three-dimensional scaffolds are critical to stabilize cells and impersonate the ECM during tissue formation. To augment the quality, taste, and tenderness of CBM, it may be advisable to co-culture preadipocytes with myoblast, owing to their effective increase in intramuscular fat content of cultures meat.

Collagen forms an intramuscular connective tissue network, and it is the most abundant fibrous protein in skeletal muscle (10% by weight) (Gillies and Lieber, 2011). Collagen provides elasticity, tensile strength, strengthens bones, regulates cell attachment, and role in differentiation (Ahmad et al., 2020). Collagens are necessary for the self-renewal of MSC and differentiation in vivo in mice. For example, the knockout of collagen VI impaired regenerating capacity of MSC following muscle injury (Urciuolo et al., 2013).

Collagens are found in numerous forms, and several of them have been revealed in skeletal muscles, such as fibrillar collagens I, III, V, IX, and XI. Collagen I and III account for more than 75% of total skeletal muscle collagen (McKee et al., 2019). Collagen and gelatins are widely applied in the pharmaceutical and food industries owing to their biodegradability, biocompatibility, and low antigenicity (Liu et al., 2015).

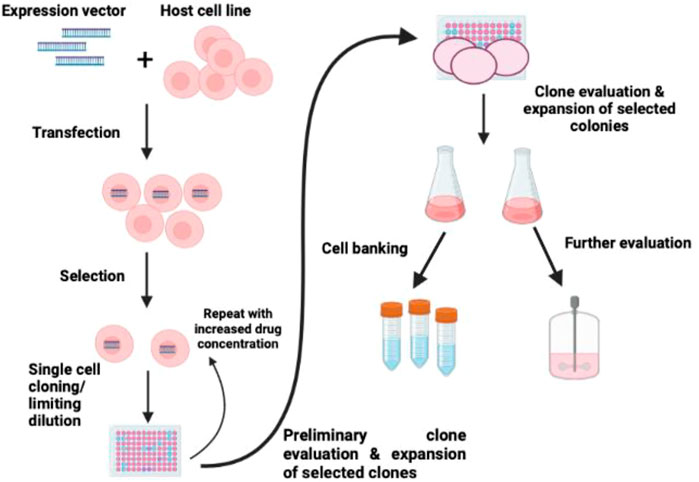

4 Immortalization

Efforts are being made to develop cell lines for CBM to cultivate and facilitate the research and development of novel food products. Recently, the Good Food Institute, in collaboration with Kerafast, has standardized and developed terrestrial as well as aquatic cell lines suitable for CBM (The Good Food Institute, 2019). The main objective of any firm is to develop a novel cell line that is immortal, loses its cell cycle checkpoint pathways, and bypasses the senescence process. There are at least three approaches in establishing cell lines, i) expression of the catalytic subunit of telomerase, ii) introduction of viral genes that inactivate p53/p14/Rb, and iii) serendipitous discovery of immortalized cell lines. Every approach exploits either the expression of telomerase, the circumventing/inactivation of cell cycle checkpoint, or a combination of both (Maqsood et al., 2013).

The insertion of telomerase in immortalizing cell lines has been utilized since 1999 (Ouellette, 2000). The telomere extension helps cells escape cell death triggered by telomere shortening. This can be achieved by ectopic telomerase expression encouraging immortalization of human esophageal keratinocytes (normal) without deactivating the p53 pathway (Harada et al., 2003). Immortalized fibroblast cell lines are also generated from human embryonic stem cells under undifferentiated cell growth conditions, thus creating a system for the culture of hESCs (Xu et al., 2004).

DNA damage and other stress activate transcription factor p53 causing cell cycle arrest until the cell establishes that DNA can be repaired. If the DNA damage is irreversible, p53 plays a role in activating and triggering apoptosis and cell cycle arrest (Chen, 2016). Consequently, activation of p16 and Rb halts other proteins from initiating DNA replication, resulting in apoptosis (Takahashi et al., 2007). Mutating the p16 or Rb gene may allow cells to continue DNA replication leading to immortalization (Maqsood et al., 2013).

Previously, the immortalized cell line was established through inactivation or bypassing the p53/p16/Rb stress response by transforming viral genes (Figure 4). Here in this method, simian virus 40 (SV40) large T-antigen were planned to bind and inactivate p53/Rb and other tumor suppressor factors in a variety of species and organ types (Jin et al., 2006; Yamada et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). Customarily, T-antigen reactivates the host cell to stimulate the replicate SV40 virion (Ahuja et al., 2005). However, in most mammalian systems, the T-antigen can transform the host cell without viral assembly and cell death leading to stable transformation and immortalization in the host cell (Chou, 1989). Apart from SV40 T-antigen, a few other viruses and viral proteins, such as E1A and E1b protein of adenovirus, E6 and E7 ORFs of human papillomavirus, and Epstein-Barr virus, have been employed to produce immortal cell lines through inactivation of cell cycle checkpoints (Shay et al., 1991; Counter et al., 1992; Klingelhutz et al., 1994; Oh et al., 2003).

FIGURE 4. Schematic diagram of immortalization of cells. The strategy of immortalization can be achieved by the induction of telomerase expression and inactivating p53/p16/Rb (Maqsood et al., 2013).

Recently, Upside Foods, a United States-based cultured meat firm, submitted a patent employing telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) overexpression utilizing CRISPR to knock out the expression of p16 and p16 in chicken skeletal muscle cells (Thorley et al., 2016). The proliferative capacity of cells increases owing to the knockout of p15 and p16 alone; however, adding the ectopic TERT gene has augmented the overexpression of TERT indefinitely. Some approaches to immortalizing the myogenic cell lines may evade telomere shortening and the p16 stress pathway by ectopic expression of TERT and the Rb inhibitors cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (Stadler et al., 2011; Genovese N. et al., 2017).

4.1 Challenges in establishing a unique cell line

CBM needs unique cell lines prepared from agriculturally effective systems to scale up on an industrial scale. One of the first daunting tasks in CBM is establishing its cell line, which can be used in each cycle to produce meat. Few firms (Kerafast, United States and ESCO ASTER, Singapore) manufacture cell lines of various species for commercial purposes. MACK1 (myoblast) adherent cell line derived from the mature muscle of Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) for useful cellular agriculture (Saad et al., 2022). ICAR-National Bureau of Fish Genetic Resources, India, has a repository of about a cell line of 50 fishes, especially Catla. Freshwater fish species of Bluegill fry cell line (adherent fibroblast), Rainbow trout, and embryonic cell line of Nile tilapia have already been established (NRFC, 2023). Researchers are manipulating the stem cell expression markers in a suitable culture medium to develop unique methods for myogenesis induction in the cell lines (Thorley et al., 2016). Presently, few labs are working on establishing particular cell lines for various organisms like bovine, seafood, and aquatic species (Better ways to start cultivating meat | Research (2020-2022) | GFI, 2021). One of the main obstacles in developing a cell line is the limited knowledge of surface genetic markers and the non-availability of species-specific antibodies to assist in identifying a suitable cell line. However, few firms have developed the cell lines of various species like chicken, fish and turkey, and are commercially available (Kerafast) (Kerafast, 2023). Due to limited growth of the primary existing cells (not growing beyond 30–40 passages) in the defined media, is the main reason for developing the cell lines. In November 2022, UPSIDE Foods reported the establishment of myoblast and fibroblast cell lines with demonstrated differentiation capacity in the suspension culture (Ding et al., 2018). Immortalization has been carried out through the introduction of a cis gene expressing chTERT. Based on their presented data, US FDA gave the green light to conduct further research to develop CBM.

Developing a cell-based fish cell line to meet the growing demand for alternative proteins has several advantages over mammalian and avian CBM approaches. Firstly, fish cells may undergo less senescence and have more doubling with regard to mammalian and avian species (excluding embryonic stem cells) (Klapper et al., 1998; Strecker et al., 2010; Graf et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2018). Secondly, fish cell lines are known for maintaining karyotypic stability with respect to mammalian and avian species (Barman et al., 2014; Fan et al., 2017). Thirdly, a fish cell may easily grow under atmospheric air and possess high intracellular buffering capacity (Bols and Lee, 1991; Rubio et al., 2019). In cell culture bioreactor avian and mammalian cells require carbon dioxide and bicarbonate to control the pH in addition to air, oxygen, and nitrogen (Warner et al., 2015). Managing only three gases (air, oxygen, and nitrogen) is an advantage of fish cells over mammalian cells as it simplifies scale-up challenges and mitigates the issue of CO2 stripping (Sieblist et al., 2016).

5 Culture media components

Culture media is one of the crucial parameters of the final cultured meat product that maintains cells in ex vivo (Post et al., 2020). Depending upon media components, the taste and texture of the cultured meat are decided. The following section discusses various media types commonly used in CBM. Basal media formulations are sufficient to keep the cell alive for a limited period; however, various media are used to proliferate for extended periods. Minimal essential medium (MEM) is frequently used to maintain cells in tissue culture comprising amino acids, vitamins, glucose, and salts (Eagle, 1959). Minute variations in MEM have created a new media commonly used for mammalian cell cultures, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (van der Valk et al., 2010)

In cell culture, 70% of the glucose is converted into lactate by highly proliferating cells; however, 20%–30% of the remaining glucose is available for tricarboxylic acid (Ryan et al., 1987). The lack of nutritional components like vitamins D, E, and selenium may cause degenerative changes in muscle (Braga et al., 2017).

The proliferating cells require a special type of media compared to differentiating cells. Energy requirement changes from general nutrient usage to highly specialized protein production depending on cell types. Cell culture media poses a challenge to sustainable cellular agriculture.

Fetal bovine serum (FBS) is an animal-derived component commonly used as media; the possibility of contamination violates ethics and is unsustainable for CBM. FBS is perceived as a universal supplement comprising 200–400 kinds of proteins and numerous small molecules with undefined concentrations.

Chemically defined media components such as proteins, sugars, growth factors, and fatty acids can replace FBS with previously established procedures (van der Valk et al., 2010).

Growth factors regulate cellular activities like proliferation, differentiation, and stimulation as they activate signaling pathways. The commonly employed growth factors for stem cell research are fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epithelial growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), vascular endothelial growth factor, bone morphogenic proteins, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). For proper muscle development, hepatocyte growth factors, FGF, IGF, and PDGF are also pertinent (Goonoo and Bhaw-Luximon, 2019).

Some commercially available growth factors for bioactive compound production or therapeutic application are mainly produced with research-grade or cGMP benchmarks. To meet the quality of the food industry especially concerned with cell culture expression, the growth factors require cost-effective management on an industrial scale.

Glucose and amino acids are major components in high concentrations and strongly affect the environmental footprint. Glucose as a substrate gives rise to amino acids through fermentation (Ikeda and Nakagawa, 2003). The production of glucose on an industrial scale has been well-established since centuries ago, with modest waste production and a high level of integration (An and Katrien, 2015). The approach is based on the hydrolysis of starch which is naturally produced by photosynthesis. Scientists are utilizing an alternative source of peptides, amino acids that are usually obtained from the bacterial, fungal, and algal biomass that is enriched with fats, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals (Xu et al., 2006; Ramos Tercero et al., 2014; Matassa et al., 2016). Recycling culture media is one of the vital aspects of CBM with a promising results concerning cost-effective and extended batch duration (Yang et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018). In perfusion systems, this method may appreciably curtail the use of sterile water; however, media recycling in mammalian systems is still in its infancy.

The investigations done by Kolkmann et al. on serum-amended DMEM to culture bovine myoblasts have shown the potential of FBM (Fibroblast Basal Medium), FBM/DMEM, and Essential 8™ Medium to become alternative (Kolkmann et al., 2020). This group recently developed chemically defined media which supports 97% of the growth of the primary bovine myoblast cells compared with golden standard culture medium. The composition of the media is DMEM/F12 as a basal medium, supplemented with L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, fibronectin, hydrocortisone, GlutaMAX™, albumin, ITSX, hIL-6, α-linolenic acid, and growth factors such as FGF-2, vascular endothelial growth factor, IGF-1, HGF, and PDGF-BB (Kolkmann et al., 2022). Insulin or IGF1, FGF2, and TGF-β1 are the three key signaling components in nutritionally rich E8 serum-free media (Amit et al., 2004; Kuo et al., 2020). Novel media formula (B8) was introduced by Chen Y et al. to support a high growth rate under low seeding density conditions and to grow iPSCs for more than 100 passages (Chen et al., 2021). Research studies are developing small molecule cocktail (chroman 1, emricasan, polyamines, and trans-ISRIB—CEPT) patents and Rho Kinase inhibitors—ROCKi to increase the cell yield cellular survival during differentiation (Watanabe et al., 2007).

6 Scaffolding

It is an agent that mimics the in vivo system (biomechanical and biophysical) and enables the final product’s potential vascularization and spatial heterogeneity. Scaffolding provides structural and mechanical support to the cell types, ensuring their proper growth and adherence to the flasks. Most current scaffolds are based on mammalian-derived biomaterials; other than that, non-mammalian sources, namely, salmon gelatin, alginate, and additives, including gelling agents and plasticizers, are also being used. The mechanical strength arises from the network structure rather than the properties of individual collagen fibers. To achieve the texture of conventional meat, either by using mechanically similar scaffolding materials or by inducing cells to secrete their own ECM is necessary (Bomkamp et al., 2022). For CBM production, biomaterials, such as biopolymers, growth factors, enzymes, and various additives, are considerably used on a commercial scale. These biomaterials should be inexpensive, environment friendly, and cost-effective. The porous biomaterial allows the exchange of oxygen, nutrient inflow, and waste product removal to continue the cell’s metabolic function and avoid necrotic formation during the process. A complete balance of morphology, structure, and chemistry is needed. Customarily, scaffolding was established for medical purposes in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (Owen and Shoichet, 2010; Garg and Goyal, 2014; Aamodt and Grainger, 2016). Here CBM requires different standards such as degradable, safe for consumption, palatable, texture, taste, and nutritional values. Essentially, the scaffold should be safe, readily available, and cost-effective for industrial production.

Manipulating the biologically sourced material such as collagen and ECM should be kept at a minimum as they are non-replicative and need livestock for their generation. Few promising materials such as cellulose, starch (amylose and amylopectin), chitin, chitosan, alginates, and hyaluronic acid are commonly used (Cunha and Gandini, 2010; Ben-Arye et al., 2020). Protein-based systems, for example, fibrin, collagen, keratin, gelatin, or silk, are also preferred. Other types of material, for instance, the derivatives of polyester, polyhydroxyalkanoates, and proteins expressed in the bacterial system, are currently being utilized (Bugnicourt et al., 2014). Plant-based proteins (lignin), decellularized leaves, and fungal mycelia are also actively pursued (Modulevsky et al., 2014). Apart from biopolymers, various synthetic polymers, including a range of polyesters, are favored owing to their tailored degradation through chemical hydrolysis in the human body (Woodard and Grunlan, 2018).

Biopolymers extracted from a non-mammalian source such as algae (alginate or agar) and fish species (gelatin) have been commercially used in tissue engineering (Nagai et al., 2008; Yamada et al., 2014). Alginate and agar allow the cultures of mammalian cells due to the non-availability of cell recognition sites the-Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), which stimulate cell adhesion and migration (Bedian et al., 2017; Schuster et al., 2017). However, gelatin possesses RGD sequences, and a promising approach is to blend algae-derived polymers having fish-derived gelatin. One prominent and attractive ingredient to produce edible and biodegradable scaffolds is salmon gelatin (Enrione et al., 2012). The physical properties of salmon gelatin allow blending with other biopolymers to form copolymers and stable polyelectrolyte complexes owing to lower melting temperatures than other mammalian gelatin (Acevedo et al., 2015).

6.1 Microcarriers

Microcarriers are beads comprising various materials, porosities, and topographies that provide a surface for anchorage to the cells to hold (McKee and Chaudhry, 2017). Microcarriers offer a large surface-to-volume ratio and are perceived as critical for upscaling in CBM. Microcarriers suspended in a medium provide a 3D culture environment.

Since the inception of the microcarrier concept for the culture of adherent cells in 1967, numerous microcarriers have been established and commercialized (Van Wezel, 1967). Generally, microcarriers have been used for the expansion of cells fabricating molecules of interest, such as monoclonal antibodies, vaccines, and proteins (Phillips et al., 2008). In a recent development in the field of cell and gene therapy, emphasis has been given to developing microcarriers for the culture of human stem cells for therapeutic purposes (Cui et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2013; Gümüşderelioğlu et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016).

Microcarriers exploited for CBM production should fulfill the food regulation of the country while proposing optimal topography and surface chemical properties for target cell types. Preferably, microcarriers should be animal-free components to prevent the use of animal products throughout the production of CBM.

Microcarriers may also work as nutrient carriers, such as essential growth factors, amino acids, etc., to meet the satellite cell’s nutrient demand. This can help minimize the number of medium exchange steps and reduce the risk of contamination and cell loss. Successful loading of sol-gel-derived bioactive glass microcarriers in combination with basic FGF-2 and cytochrome c were sustainably released spanning several weeks (Perez et al., 2014). Sustained release and microencapsulation of bioactive molecules are currently given the utmost importance in the food industry (O’Neill et al., 2014; Shishir et al., 2018). The principle may also apply to microcarriers-based cell culture in meat production. Physical parameters like temperature and pH can be tuned to control in vitro release kinetics from loaded microcarriers (Zhou et al., 2018; Matsumoto et al., 2019).

Satellite cells are anchorage-dependent; thereby, these cells require microcarriers surface for the attachment. The attachment of cells is a critical parameter that affects the entire process of yield (Bock et al., 2009). Cell attachment encompasses the association between cell adhesion molecules and substrates on the surface of the microcarriers (Goldmann, 2012). The integrin protein regulates cell adherence (Derakhti et al., 2019). These are heterodimeric glycoproteins comprising a and b subunits, each with various isoforms depending on the expression of isoforms (Rowley et al., 1999). Integrins bind to a diverse class of proteins with different combinations like α1β1 has a specific affinity to collagen, α5β1 to fibronectin, and αvβ3 to vitronectin (Barczyk et al., 2010).

Recently, Norris et al. developed edible microcarriers possessing tunable mechanics as well as a surface topology for CBM (Norris et al., 2022). They are made-up microcarriers employing gelatin and food-grade crosslinking enzyme (transglutaminase). The inexpensive method does not require the application of any synthetic polymeric materials, instead needs small crosslinking agents or modified chemical groups. The scalable process to produce edible microcarriers by exploiting water-in-oil emulsions enables readily fabricating hydrogel microparticles with a spherical shape and smooth surface.

6.2 Bioreactors (scale-up)

The crucial aspects of the scale-up are bioprocess modeling and optimization, for which spinner flasks act as small-scale systems, especially in defining mass and energy transfer models. Because of this, attempts were made to mimic the 3D environment in the spinner flasks for the animal cell culture by internal mixing (Verbruggen et al., 2018). There are different lab-scale reactors for use in tissue engineering. Biopharmaceuticals are stirred-tank, hollow fiber, roller bottles, rocking bed, fluidized-bed and fixed (packed) bed systems (Odeleye et al., 2020). Vijay Singh first described the rocking bed bioreactor or wave reactor intended for the cultivation of animal cells (Singh, 1999). Wave bioreactor contains a flexible polymeric bag with special ports for allowing us to introduce air, oxygen, or medium or to withdraw samples under sterile conditions. Fluidized bed reactors (FBRs) are rarely applied in tissue culture, but homogenous bed expansion behavior, related to good mass transfer characteristics, as well as lower shear stress, compared to stirred tank reactors and simpler scale-up procedures, makes them advantageous to others in the production of the cultured meat (Ellis et al., 2005). In hollow fiber bioreactors, hollow fibers act as a semi-permeable membrane by allowing the water and nutrients for cell growth while removing metabolic products and serve as a cell immobilization base by not allowing cells to pass through it (Baba and Sankai, 2017).

The large-scale production of cultured meat requires bioreactors. The ultimate bioreactor will have properties like mass transfer, oxygen level, shear stress, and medium flow at optimum levels to produce high output and support the cells with the scaffold. Bioreactors with specific functions are available. Studies have been carried out on bioreactors, like rotating wall vessel bioreactors, direct perfusion bioreactors, and microcarrier-based bioreactors for producing cultured meat. Porous scaffolds that allow media flow through it are used in direct perfusion reactors, and gas exchange will happen in a fluid loop located externally. These reactors maintain the scaffolds-based culture with high mass transfer and great shear stress (Carrier et al., 2002). For the differentiation phase, animal cell immobilization on an edible scaffold or MCs with perfusion mode operation method is a promising approach for the production of CM (Allan et al., 2019; Bellani et al., 2020; Letti et al., 2021). The limitations of these bioreactors are membrane fouling which leads to heterogeneous cell growth, mass transport limitations, and non-uniform nutrient and inhibitor gradients (Yang et al., 2006; Detzel et al., 2010).

In vivo-like conditions are maintained in rotating wall vessel bioreactors by regulating the rotating speed in a row, balances the centrifugal force, drag force, and gravitational force, and finally allowing the 3D culture to be submerged in the medium (van der Weele and Tramper, 2014). This type of reactor bears high mass transfer with reduced shear stress. A well-mixed environment that controls bioprocess conditions precisely, such as pH value, dissolved oxygen concentration, and concentration of nutrients in the cell culture broth, will be provided in Stirred tank reactors (Badenes et al., 2016; Bellani et al., 2020; Hanga et al., 2021). Bovine adipose-derived stem cells are used as precursor cells for both adipose and muscle cells in a single-use, disposable STR vessel (Mobius CellReady 3 L, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, United States) to expand the cells in 100 mL-spinner flask to 3 L-STR resulted in a notable fold increase of 114.19 ± 1.07 for bovine adipose-derived stem cell number (Hanga et al., 2021).

Microcarrier-based reactors support the cells in 3D environments. Microcarriers are used in two ways one is suspension, and the other is packed bed reactors. In the case of packed bed reactors, the medium flow should be continuous and oxygenated before entering the reactor; the limitation of this type of reactor is it is only useful for up to 30 L of volume. In the case of suspension-based microcarriers, the cells should grow on them, and the characteristics of the cell will vary according to the seeding density. The formation of aggregates and shear stress due to agitation are the major problems with these reactors (Moritz et al., 2015).

7 Conclusion

CBM is an emerging field of cellular agriculture. The biotechnological advancement utilized skeletal muscle tissue engineering technology to bypass livestock farming. CBM came into existence after growing concerns of animal welfare, ethical approval, and sustainable livestock management. Technological advancements like bioprocessing engineering and tissue engineering lead to the isolation and propagation of stem cells, identification and modification of suitable biomaterials, and designing culture systems with different cell types like muscle and fat cells. Specialized industrial bioreactors equipped with state-of-the-art technology utilizing serum-free media components are prerequisites for commercial CBM production. Shortly cultured meat or the food industry will be one of the essential parameters in food security in developing countries like India and Southeast Asia. The research and development in cellular agriculture are in the right direction. Still, we need robust scientific, industrial, and commercial connecting links to create a full spectrum of CBM industries to flourish.

Author contributions

AA initiated the concept, wrote checked the draft and finalized the manuscript. SB helped in writing. SK prepared the tables and wrote few sub-section. SS edited the manuscript. GP edited, checked and finalized the draft version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Neat Meatt Biotech Pvt. Ltd. Is highly thankful to the Startup SEED FUND SCHEME of India (Atal Incubation Center-CCMB Hyderabad) for providing a grant to support the CBM project. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, KSA, for funding this work through a research group program under grant number RGP. 2/181/43.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Mairaj Ansari, Department of Biotechnology, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, for the proofreading of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Authors AA, SB and SS were employed by company Neat Meatt Biotech Pvt. Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AMR, Antimicrobial resistance; CDK, Cyclin-dependent kinase; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; EGF, Epithelial growth factor; ECM, Extracellular matrix; FBS, Fetal bovine serum; FGF, Fibroblast growth factor; GHG, Greenhouse gas; HH stage, Hamburger Hamilton stage; IGF, Insulin-like growth factor; LIF, Leukemia inhibitory factor; MSC, Mesenchymal stem cell; MDC, Muscle derived cell; MDSC, Muscle-derived stem cell; MyHC, Myosin heavy chain; PDGF, Platelet-derived growth factor; SMSC, Skeletal muscle satellite cell; TERT, Telomerase reverse transcriptase.

References

Aamodt, J. M., and Grainger, D. W. (2016). Extracellular matrix-based biomaterial scaffolds and the host response. Biomaterials 86, 68–82. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.003

Abbott, M. T., Pearson, A. M., Price, J. F., and Hooper, G. R. (1977). Ultrastructural changes during autolysis of red and white porcine muscle. J. Food Sci. 42, 1185–1188. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1977.tb14456.x

Acevedo, C. A., Díaz-Calderón, P., López, D., and Enrione, J. (2015). Assessment of gelatin–chitosan interactions in films by a chemometrics approach. CyTA - J. Food 13, 227–234. doi:10.1080/19476337.2014.944570

Ahmad, K., Shaikh, S., Ahmad, S. S., Lee, E. J., and Choi, I. (2020). Cross-talk between extracellular matrix and skeletal muscle: Implications for myopathies. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 142. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00142

Ahuja, D., Sáenz-Robles, M. T., and Pipas, J. M. (2005). SV40 large T antigen targets multiple cellular pathways to elicit cellular transformation. Oncogene 24, 7729–7745. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209046

Allan, S. J., De Bank, P. A., and Ellis, M. J. (2019). Bioprocess design considerations for cultured meat production with a focus on the expansion bioreactor. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 3, 44. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2019.00044

Almada, A. E., and Wagers, A. J. (2016). Molecular circuitry of stem cell fate in skeletal muscle regeneration, ageing and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 267–279. doi:10.1038/nrm.2016.7

Amit, M., Shariki, C., Margulets, V., and Itskovitz-Eldor, J. (2004). Feeder layer- and serum-free culture of human embryonic stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 70, 837–845. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.103.021147

An, V., and Katrien, B. (2015). Life cycle assessment study of starch products for the European starch industry association (starch europe): Sector study, 30.

Anomaly, J. (2015). What’s wrong with factory farming? Public Health Ethics 8, 246–254. doi:10.1093/phe/phu001

Asakura, A., Hirai, H., Kablar, B., Morita, S., Ishibashi, J., Piras, B. A., et al. (2007). Increased survival of muscle stem cells lacking the MyoD gene after transplantation into regenerating skeletal muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 16552–16557. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708145104

Asfour, H. A., Allouh, M. Z., and Said, R. S. (2018). Myogenic regulatory factors: The orchestrators of myogenesis after 30 years of discovery. Exp. Biol. Med. Maywood NJ 243, 118–128. doi:10.1177/1535370217749494

Avesar, J., Rosenfeld, D., Truman-Rosentsvit, M., Ben-Arye, T., Geffen, Y., Bercovici, M., et al. (2017). Rapid phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing using nanoliter arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, E5787–E5795. doi:10.1073/pnas.1703736114

Baba, K., and Sankai, Y. (2017). Development of biomimetic system for scale up of cell spheroids - building blocks for cell transplantation. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. Annu. Int. Conf. 2017, 1611–1616. doi:10.1109/EMBC.2017.8037147

Badenes, S. M., Fernandes, T. G., Rodrigues, C. A. V., Diogo, M. M., and Cabral, J. M. S. (2016). Microcarrier-based platforms for in vitro expansion and differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells in bioreactor culture systems. J. Biotechnol. 234, 71–82. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.07.023

Baeza-Raja, B., and Muñoz-Cánoves, P. (2004). p38 MAPK-induced nuclear factor-kappaB activity is required for skeletal muscle differentiation: role of interleukin-6. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2013–2026. doi:10.1091/mbc.e03-08-0585

Baig, M. H., Rashid, I., Srivastava, P., Ahmad, K., Jan, A. T., Rabbani, G., et al. (2019). NeuroMuscleDB: A database of genes associated with muscle development, neuromuscular diseases, ageing, and neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 5835–5843. doi:10.1007/s12035-019-1478-5

Barczyk, M., Carracedo, S., and Gullberg, D. (2010). Integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 339, 269–280. doi:10.1007/s00441-009-0834-6

Barman, A. S., Lal, K. K., Rathore, G., Mohindra, V., Singh, R. K., Singh, A., et al. (2014). Derivation and characterization of a ES-like cell line from Indian catfish Heteropneustes fossilis blastulas. Sci. World J. 2014, 427497–427499. doi:10.1155/2014/427497

Bedian, L., Villalba-Rodríguez, A. M., Hernández-Vargas, G., Parra-Saldivar, R., and Iqbal, H. M. N. (2017). Bio-based materials with novel characteristics for tissue engineering applications - a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 98, 837–846. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.02.048

Bellani, C. F., Ajeian, J., Duffy, L., Miotto, M., Groenewegen, L., and Connon, C. J. (2020). Scale-up technologies for the manufacture of adherent cells. Front. Nutr. 7, 575146. doi:10.3389/fnut.2020.575146

Ben-Arye, T., Shandalov, Y., Ben-Shaul, S., Landau, S., Zagury, Y., Ianovici, I., et al. (2020). Textured soy protein scaffolds enable the generation of three-dimensional bovine skeletal muscle tissue for cell-based meat. Nat. Food 1, 210–220. doi:10.1038/s43016-020-0046-5

Bérard, J., Kalbe, C., Lösel, D., Tuchscherer, A., and Rehfeldt, C. (2011). Potential sources of early-postnatal increase in myofibre number in pig skeletal muscle. Histochem. Cell Biol. 136, 217–225. doi:10.1007/s00418-011-0833-z

Better ways to start cultivating meat | Research (2020-2022) |GFI (2021). Grantee page cell lines making muscle cells eth zurich. Available at: https://gfi.org/researchgrants/grantee-page-cell-lines-making-muscle-cells-eth-zurich/(Accessed June 29, 2022).

Biressi, S., Molinaro, M., and Cossu, G. (2007). Cellular heterogeneity during vertebrate skeletal muscle development. Dev. Biol. 308, 281–293. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.006

Bober, E., Franz, T., Arnold, H. H., Gruss, P., and Tremblay, P. (1994). Pax-3 is required for the development of limb muscles: A possible role for the migration of dermomyotomal muscle progenitor cells. Dev. Camb. Engl. 120, 603–612. doi:10.1242/dev.120.3.603

Bock, A., Sann, H., Schulze-Horsel, J., Genzel, Y., Reichl, U., and Mã¶hler, L. (2009). Growth behavior of number distributed adherent MDCK cells for optimization in microcarrier cultures. Biotechnol. Prog. 25, 1717–1731. doi:10.1002/btpr.262btpr.262

Bols, N. C., and Lee, L. E. (1991). Technology and uses of cell cultures from the tissues and organs of bony fish. Cytotechnology 6, 163–187. doi:10.1007/BF00624756

Bomkamp, C., Skaalure, S. C., Fernando, G. F., Ben-Arye, T., Swartz, E. W., and Specht, E. A. (2022). Scaffolding biomaterials for 3D cultivated meat: Prospects and challenges. Adv. Sci. Weinh. Baden-Wurtt. Ger. 9, e2102908. doi:10.1002/advs.202102908

Bonneau, M., and Lebret, B. (2010). Production systems and influence on eating quality of pork. Meat Sci. 84, 293–300. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.03.013

Bonnet, M., Cassar-Malek, I., Chilliard, Y., and Picard, B. (2010). Ontogenesis of muscle and adipose tissues and their interactions in ruminants and other species. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci. 4, 1093–1109. doi:10.1017/S1751731110000601

Borycki, A. G., Li, J., Jin, F., Emerson, C. P., and Epstein, J. A. (1999). Pax3 functions in cell survival and in pax7 regulation. Dev. Camb. Engl. 126, 1665–1674. doi:10.1242/dev.126.8.1665

Brack, A. S., and Rando, T. A. (2012). Tissue-specific stem cells: Lessons from the skeletal muscle satellite cell. Cell Stem Cell 10, 504–514. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.001

Braga, M., Simmons, Z., Norris, K. C., Ferrini, M. G., and Artaza, J. N. (2017). Vitamin D induces myogenic differentiation in skeletal muscle derived stem cells. Endocr. Connect. 6, 139–150. doi:10.1530/EC-17-0008

Broholm, C., Laye, M. J., Brandt, C., Vadalasetty, R., Pilegaard, H., Pedersen, B. K., et al. (2011). LIF is a contraction-induced myokine stimulating human myocyte proliferation. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md 111, 251–259. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01399.2010

Buckingham, M., and Relaix, F. (2015). PAX3 and PAX7 as upstream regulators of myogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 44, 115–125. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.09.017

Buckingham, M., and Relaix, F. (2007). The role of Pax genes in the development of tissues and organs: Pax3 and Pax7 regulate muscle progenitor cell functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 645–673. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123438

Bugnicourt, E., Cinelli, P., Lazzeri, A., and Alvarez, V. (2014). Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): Review of synthesis, characteristics, processing and potential applications in packaging. Express Polym. Lett. 8, 791–808. doi:10.3144/expresspolymlett.2014.82

Burgerhout, E., Mommens, M., Johnsen, H., Aunsmo, A., Santi, N., and Andersen, Ø. (2017). Genetic background and embryonic temperature affect DNA methylation and expression of myogenin and muscle development in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). PloS One 12, e0179918. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0179918

Carrier, R. L., Rupnick, M., Langer, R., Schoen, F. J., Freed, L. E., and Vunjak-Novakovic, G. (2002). Perfusion improves tissue architecture of engineered cardiac muscle. Tissue Eng. 8, 175–188. doi:10.1089/107632702753724950

CGDEV (2022). CGD-Policy-Paper-59-Elliott-Antibiotics-Farm-Agriculture-Drug-Resistance. Available at: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/CGD-Policy-Paper-59-Elliott-Antibiotics-Farm-Agriculture-Drug-Resistance.pdf (Accessed June 24, 2022).

Chal, J., and Pourquié, O. (2017). Making muscle: Skeletal myogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Development 144, 2104–2122. doi:10.1242/dev.151035

Chargé, S. B. P., and Rudnicki, M. A. (2004). Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 84, 209–238. doi:10.1152/physrev.00019.2003