- 1Department of Police Science, University of Ulsan, Ulsan, Republic of Korea

- 2College of Business, University of Ulsan, Ulsan, Republic of Korea

- 3Department of Psychology, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 4School of Industrial Management, Korea University of Technology and Education, Cheonan, South Chungcheong, Republic of Korea

Swift social and economic environmental changes such as COVID-19 pandemic have led to increased job insecurity. The current study examines the intermediating mechanism (i.e., mediator) and its contingent factor (i.e., moderator) in the association between job insecurity and employee's turnover intention, especially from the perspective of positive psychology. By establishing a moderated mediation model, this research hypothesizes that the degree of employee meaningfulness in work may mediate the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention. In addition, coaching leadership may play a buffering role to positively moderate the harmful impact of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work. With three-wave time-lagged data that was collected from 372 employees in South Korean organizations, the current study not only demonstrated that meaningfulness of work mediates the job insecurity–turnover intention relationship, but also that coaching leadership functions as a buffering factor in reducing the harmful influence of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work. The results of this research suggest that the level of meaningfulness of work (as a mediator) as well as coaching leadership (as a moderator) are the underlying processes and the contingent factor in the job insecurity–turnover intention link.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant global shock that has potentially resulted in recession and economic crisis, leading to many employees around the globe losing their jobs (1). To survive this unexpected crisis, many companies have implemented massive restructuring and downsizing. As a result, employees have suffered from an increased sense of job insecurity (2–4). Job insecurity can be defined as “the perceived threat of losing the current job in the near future” [(5), p. 65].

Previous studies have demonstrated that job insecurity is closely associated with organizational outcomes. By functioning as a severe job stressor, job insecurity has been known to significantly predict employee's poor mental/physical health, burnout, job stress, turnover intention, decreased organizational commitment/identification/trust, work engagement, creativity, and organizational citizenship behavior (3, 6–15).

Although a number of studies on job insecurity have revealed the influence of job insecurity on several important organizational outcomes, we believe that there may still be some research gaps to be examined (8, 12).

First, previous scholars have suggested there is an inconclusive link between job insecurity and organizational outcomes (8, 12, 16). Specifically, several review papers (8, 12, 16) reported that job insecurity significantly diminishes the quality of individual-level, team-level, and organizational-level outcomes. The detrimental influences are because job insecurity tends to significantly elevate the degree of employee stress and negative responses such as perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors (6, 11, 16). By contrast, other scholars have demonstrated that job insecurity is likely to promote the quality of various outcomes or performances (13, 17, 18). Based on the job-preservation motivation perspective (13, 18), These results are derived from the understanding that an unstable job would urge employees to do their best to survive in their role by achieving high levels of performance. In addition, other research has reported that job insecurity is not associated with their outcomes in an organization (19). These varied and inconclusive results are due to a lack of research on intermediating processes (i.e., mediators) and contingent/contextual factors (i.e., moderators) in the association (12, 16). Therefore, our attempt to investigate various mediators and moderators is meaningful.

Second, extant works have paid relatively less attention to employee's positive psychology–associated mediators or moderators (including meaningfulness of work, forgiveness, gratitude, and coaching leadership) when explaining the underlying processes and contextual factors between job insecurity and organizational outcomes (8, 12, 20). In other words, those studies have mainly focused on “negative” aspects of organizational life.

Positive psychology has tried to explain a variety of organizational phenomena from the perspective of positive processes, attributes, and outcomes instead of negative ones (20). For example, previous scholars have reported that various negative variables such as threat to manifest/latent benefits of work (5), frustration of psychological needs (15), psychological contract breach (5), and injustice (21) function as critical mediators in the job insecurity–organizational outcomes relationship (8, 12). We acknowledge that negative mediators and moderators can meaningfully explain the influence of job insecurity in an organization. However, given that “real” organizational life includes both positive and negative aspects, examining the underlying mechanisms and its contingent factors from the perspective of positive psychology is required (8, 12, 22). This is the reason why the positive psychological approach has been acknowledged to possess theoretical and practical value (20).

Third, existing studies on job insecurity have underexplored the important role of leadership in the context of unstable job (8, 12, 16). Although scholars have reported a variety of boundary conditions (or contextual factors) that buffer the negative influence of job insecurity, they have mainly focused on individual-level variables including self-esteem, self-efficacy, internal locus of control, proactive personality, psychological capital, resilience, job control, and emotional intelligence; or macro-level factors including labor market insecurity, social safety networks, and macro-economic conditions (23–32). Thus, few studies have examined the moderating role of leadership (8, 12, 16). Leaders significantly influence employees' perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors by assigning tasks, evaluating them, establishing (explicit and implicit) norms within an organization (33, 34). They are also regarded as a main actor symbolizing the organization itself from the perspective of employees (35). Thus, investigating the moderating role of leadership is meaningful.

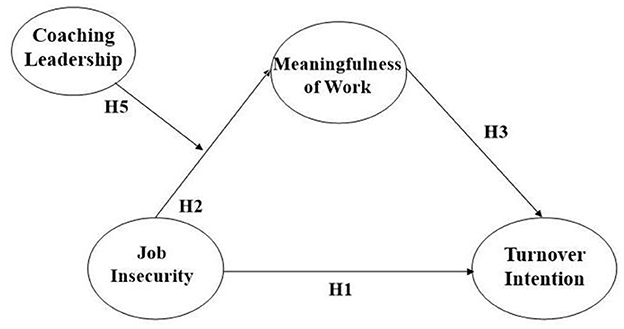

To address the described research gaps, we explore the intermediating mechanism and its contextual factor in the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention. This concept is defined as the degree to which a member wants to leave their current job or organization to seek another one (36, 37). More specifically, this research suggests that employee's meaningfulness of work mediates the association between job insecurity and turnover intention. Furthermore, coaching leadership may buffer the harmful impact of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work by positively moderating the relationship.

To empirically test our hypotheses, we present a moderated mediation model in this paper that uses structural equation modeling (SEM) with 3-wave time-lagged data from 372 Korean workers. We expect the findings of this study will contribute to both job insecurity and turnover intention literature as follows. First, in the current paper, we try to elucidate the inconclusive relationship between job insecurity and organizational outcomes by exploring the intermediating mechanism (i.e., a mediator) and its contextual factor (i.e., a moderator) of the relationship. Second, we explore the intermediating process and its contingent variable from the perspective of positive psychology (i.e., meaningfulness of work and coaching leadership). Third, the research emphasizes the important role of leadership by demonstrating that coaching leadership, as one of the emerging leadership styles, functions as a buffering factor that diminishes the harmful effect of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work. Lastly, from a methodological point of view, this study complements the limitations of cross-sectional data by applying a longitudinal approach (i.e., 3-wave time-lagged research design).

Theories and hypotheses

Job insecurity and turnover intention

In the current research, we propose that job insecurity would functions as a critical antecedent of employee turnover intention (8, 36, 38). According to the conservation of resources theory (38), when an individual copes with the threat of resource loss, they may seek to replace resources. Thus, when an employee feels a sense of threat of resource due to instability in their job, they are likely to redirect their energies and resources away from their current role to search for new and more stable employment (8, 38). Based on this argument, this research anticipates that job insecurity will be shown to increase employee turnover intention.

Hypothesis 1: An employee's job insecurity may increase their turnover intention.

Job insecurity and meaningfulness of work

We suggest that job insecurity will reduce the degree of employee's meaningfulness of the work. Meaningfulness of work is defined as the general beliefs, values, and attitudes that employees have about their work (39) as well as the degree to which employees consider their work to be valuable and important (40). Existing studies have considered that the perception of meaningfulness of work is rooted in the subjective interpretation of each employee's experiences and interactions at work (40–42). Being based on self-efficacy perspective (43, 44), those studies reveal that employees' self-efficacy, self-esteem, and competence are the essential antecedents of their meaningfulness of work (41, 45, 46). An employee who not only successfully completes assigned tasks but also effectively makes positive changes in an organization would feel a sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem. Then, they are likely to experience a high level of meaningfulness of work (46, 47). However, in a state of job insecurity, employees feel great psychological stress, anxiety, and exhaustion, which significantly diminishes their self-esteem, self-confidence, and self-efficacy (48–51). Those negative psychological effects substantially reduce their sense of meaningfulness of work. Based on the arguments, we suggest this hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: An employee's job insecurity may reduce their meaningfulness of work.

Meaningfulness of work and turnover intention

In the current study, we propose that diminished employee meaningfulness of work will increase their turnover intention. An employee tends to want their work to be more than just a means of making money; thus, they attempt to search for meaning in the workplace (41, 52). Extant studies have reported that employees' meaningfulness of work is likely to enhance their positive perceptions and attitudes, such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intrinsic motivation (40, 46, 53–55), eventually enhancing positive emotions and their psychological states (56).

To be specific, the influence of meaningfulness of work on turnover intention can be explained by social exchange theory (57, 58). According to the social exchange approach, an individual or a group is likely to keep balance in relationships, that is called “the rule of reciprocity” (58, 59). When an individual or a group is provided something by someone or group, the beneficiary would perceive a sense of duty to repay it similarly (57, 59). For example, from the perspective of employees, the aforementioned positive or negative psychological states which are originated in meaningfulness of work may be perceived as “additional rewards” beyond an official contract (46, 54) since the employees receive a monetary reward for their labor. Then, the employees are likely to perceive a sense of obligation to repay the additional rewards to their organization. To repay it, the employees are likely to show positive attitudes toward their organization. Then, those positive inner states and experiences reduce the employee's degree of intention to leave their organization. However, if the employee feels a sense of job insecurity, they do not experience positive psychological states, even suffering from negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and anger. Then, their turnover intention is increased. Taken together, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: Decreased employees' meaningfulness of work may increase their turnover intention.

The mediating role of meaningfulness of work

Based on the above arguments, and to integrate the relationships between the research variables in the mediation structure (i.e., job insecurity, meaningfulness of work, and turnover intention), we suggest that meaningfulness of work will mediate the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention. From the perspective of positive psychology, an employee's positivity (such as meaningfulness of work) may not only reduce due to negative perceptions such as job insecurity but may also directly reduce their negativity, such as turnover intention.

Hypothesis 4: Employees' meaningfulness of work may mediate the relationship between job insecurity and turnover intention.

The moderating role of coaching leadership

Furthermore, and more importantly, this research suggests that coaching leadership functions as a critical moderator to buffer the negative impact of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work. As already stated, our argument that job insecurity diminishes the level of employee meaningfulness of work may be reasonable and acceptable. However, the impact of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work may not always be valid in all situations or contexts in the same way because there are several contextual/contingent factors (such as personality, gender, age, leadership style, organizational climate, rule, and systems) that positively/negatively moderate the job insecurity–meaningfulness of work relationship in a real organization. Among several potential moderators, we focus on the role of leadership as a leader not only significantly influences employees' perceptions and attitudes by assigning tasks, evaluating the results, and establishing rules (34), but is also regarded as the main actor who symbolizes the organization itself from the employees' point of view (35).

Among various leadership styles, this paper focuses on coaching leadership. This concept can be defined as a leaders' behaviors that help followers effectively solve and cope with problems, difficulties, and conflicts in an organization, thereby enhancing their performance and helping them fully realize their potential and growth (60, 61). According to Heslin et al. (62), coaching leadership consists of three factors: (1) guidance, (2) facilitation, and (3) inspiration. First, guidance means providing constructive and positive feedback to followers on specific organizational expectations and goals and how to achieve them. Second, facilitation refers to helping followers analyze and explore how to solve job-related problems and improve their performance on their own. Third, inspiration means helping followers recognize their potential and value, motivating them to achieve better performance. Through these three factors, followers can develop their potential and capabilities to achieve greater self-efficacy and competence (60, 61). With increased coaching leadership, employees feel more respect and support from their leader (62, 63). This enables followers to develop a positive self-concept within the organization, feeling respected by the organization. Previous studies have reported that coaching leadership is closely and positively associated with employees' psychological wellbeing, job satisfaction, work performance, and organizational citizenship behavior (61–67).

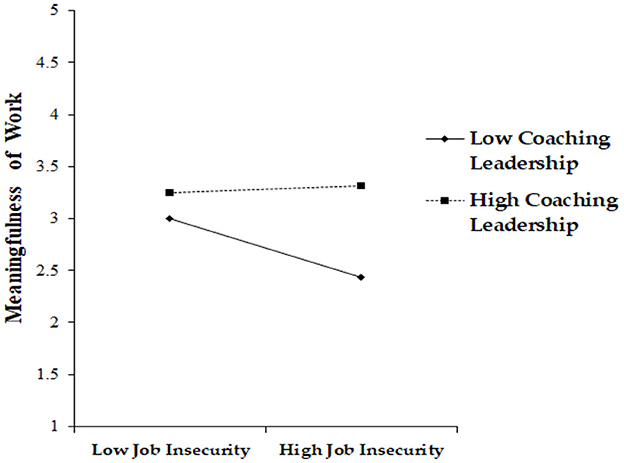

In this paper, we propose that coaching leadership mitigates the detrimental influence of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work. A leader's coaching behaviors provide effective guidance for their followers to adequately deal with negative emotional states, personal problems, and crises that originate from job instability (62). This leadership enables followers to feel a sense of respect, mutual trust, support, and self-worth within the organization, eventually reducing the negative effects of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work (60, 68). For example, when the level of coaching leadership is high, a leader's coaching behaviors guide employees to effectively cope with anxiety and fear from unstable employment, even if they feel a high degree of job insecurity. As a result, followers are less likely to feel diminished levels of meaningfulness of work.

By contrast, when the level of coaching leadership is low, followers may experience difficulty dealing with negative emotions, personal problems, and crises that are derived from unstable employment, making them feel less respected and supported by the organization (62, 64). Therefore, less coaching leadership will make employees who suffer from job insecurity perceive that they cannot adequately address the problem and are isolated from the organization. As a result, the negative impact of job insecurity may not be properly resolved and may even be amplified. Thus, we suggest the following hypothesis (please see Figure 1).

Hypothesis 5: Coaching leadership may positively moderate the relationship between job insecurity and meaningfulness of work by reducing the negative effect of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The sample consisted of currently working employees over 19 years old in various organizations in South Korea across three different time points. They were recruited through an online survey company which has an online survey system with the largest population of research panelists of ~3,450,000. The participants reported their occupational status when they registered for online membership via a user authentication system (i.e., cellular phone number or email address). Such online survey systems are considered a reliable method for accessing various samples (69).

Data was collected from employees of South Korean firms at three different time points. This was done in an effort to complement the fundamental issue embedded in cross-sectional research design. The research company randomly provided an identification number for each respondent. And the identification number was managed through the online surveying system of the company. Based on this method, we could match the questionnaires at the 3 time points. The operating function of the online system allowed us to track who responded to our survey, confirming that participants from time point 1 to time point 3 were the same. The interval between each stage was 4–5 weeks. Our survey system was open for 2 or 3 days each at each time point to provide enough time for participants to respond. When the system was open, participants could access it at any time. The company monitored the integrity of data by using traps for geo-IP violators and timestamps to flag efficient response time, which restricted participants from logging into the survey site and filling out the surveys multiple times.

The research firm contacted the participants directly to establish consent to participate in the survey, ensuring not only that their participation would be voluntary but also that their responses would be confidential and only used for research purposes. The company also reported and obtained informed consent and compliance with ethical requirements from those who agreed with the participation and reporting. The company provided the participants with a reward for their participation in the form of cash (US $8). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of a representative university in South Korea.

The research company selected the participants with a random stratified selection process to reduce the possibility of sampling bias. In stratified sampling, a random sample is drawn from each of the requisite strata. Through this sampling method, the possibility of bias from various employee characteristics that may influence the results of this research (e.g., gender, age, position, education, and industry type) is reduced. Due to its various operating functions in the online systems, this paper was able to track down who responded to it, implying that respondents from time point one to time point three are the same.

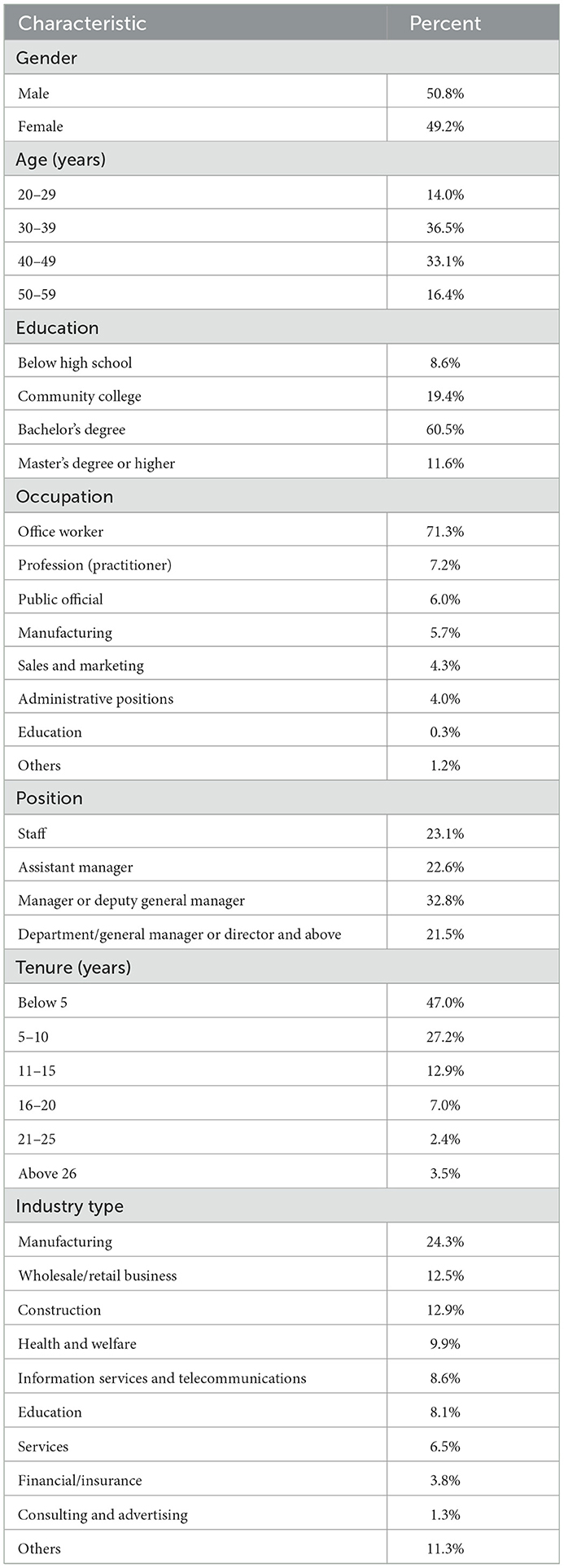

During time point 1, 512 employees participated in our survey, with 421 taking part at time point 2, and 379 at time point 3. After collecting the data, we eliminated responses with missing data. Finally, the study utilized data from 372 employees who provided complete answers to all three waves of the survey (response rate: 72.66%). To determine the sample size, we utilized various suggestions from previous research. First, we checked whether our sample size was appropriate by calculating the minimum sample size with G*Power version 3.1.9.7. Power analysis demonstrated that a sample size of 372 provided sufficient power (≥0.80) to detect a medium effect with an alpha level of p = 0.05 (70). In addition, Barclay et al. (71) suggest that one observable variable needs at least 10 cases (i.e., the rule of 10) when conducting SEM. Because the research model in this study comprised 22 observable variables, our final sample of 372 cases was considered an adequate sample. The characteristics of the respondents are described in Table 1.

Measures

At each time point, the survey measured distinct variables in our research model. At time point 1, the respondents were asked about the level of job insecurity and coaching leadership. At time point 2, participants' data were collected to measure their degree of meaningfulness of work. At time point 3, data were collected on participants' turnover intention. These variables were assessed through multi-item scales on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Moreover, through Cronbach alpha values, the internal consistency of each variable was computed.

Job insecurity (time point 1, collected from members in an organization)

We used four items for the job insecurity scale (72). Sample items were: “If my current organization were facing economic problems, my job would be the first to go,” “I will not be able to keep my present job as long as I wish,” and “My job is not a secure one.” The Cronbach's alpha value was 0.90.

Coaching leadership (time point 1, collected from employees)

To measure the degree of coaching leadership, we utilized 12 items from previous studies on coaching leadership (60, 61). Sample items were: “My leader believes in my potential for growth,” and “My leader asks questions that make me reflect on my thoughts and perspectives.” The Cronbach's alpha value was 0.94.

Meaningfulness of work (time point 2, collected from employees)

To measure the level of employee meaningfulness of work, the current study used five items of the meaningfulness of work scale from extant works (73, 74). Sample items were: (a) “The work that I do is meaningful”; (b) “The work that I do makes the world a better place”; and (c) “My work is one of the most important things in my life.” The Cronbach's alpha value was 0.88.

Turnover intention (time point 3, collected from employees)

The degree of turnover intention was measured through three items from existing studies (36, 37). The items were: (a) “How likely is it that you will look for a job outside of this organization during the next year?” (b) “How often do you think about quitting your job at this organization?” and (c) “If it were possible, how much would you like to get a new job?” The Cronbach's alpha value was 0.89.

Control variables

Based on extant studies (36, 37), the dependent variable of this research—turnover intention—was controlled by various factors such as tenure, gender, position, and education of an employee. The control variables were collected at time point 2.

Statistical analysis

First, frequency analysis was performed to check the participants' demographic features. We conducted Pearson correlation analysis using the SPSS 26 program to assess the relationships between our research variables. Then, following the suggestion of Anderson and Gerbing (75), we took a two-step approach that consists first of measurement and then the structural model. To test the validity of the measurement model, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Next, based on SEM, a moderated mediation model analysis with the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator was performed using the AMOS 23 program to test the structural model.

To test whether various model fit indexes are acceptable, this study utilized a variety of goodness-of-fit indices including the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Extant research has reported that the CFI and TLI values >0.90 and an RMSEA value of < 0.06 are appropriate (76). Finally, bootstrapping analysis was implemented to test whether the indirect effect was significant (77). Lastly, to check whether our mediation hypothesis was supported, we conducted bootstrapping analysis with a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (CI). This analysis can check the significance of the indirect mediation effect. If the CI does not include zero (0), this result indicates that the indirect effect is statistically significant with a 0.05 level (77).

Results

Descriptive statistics

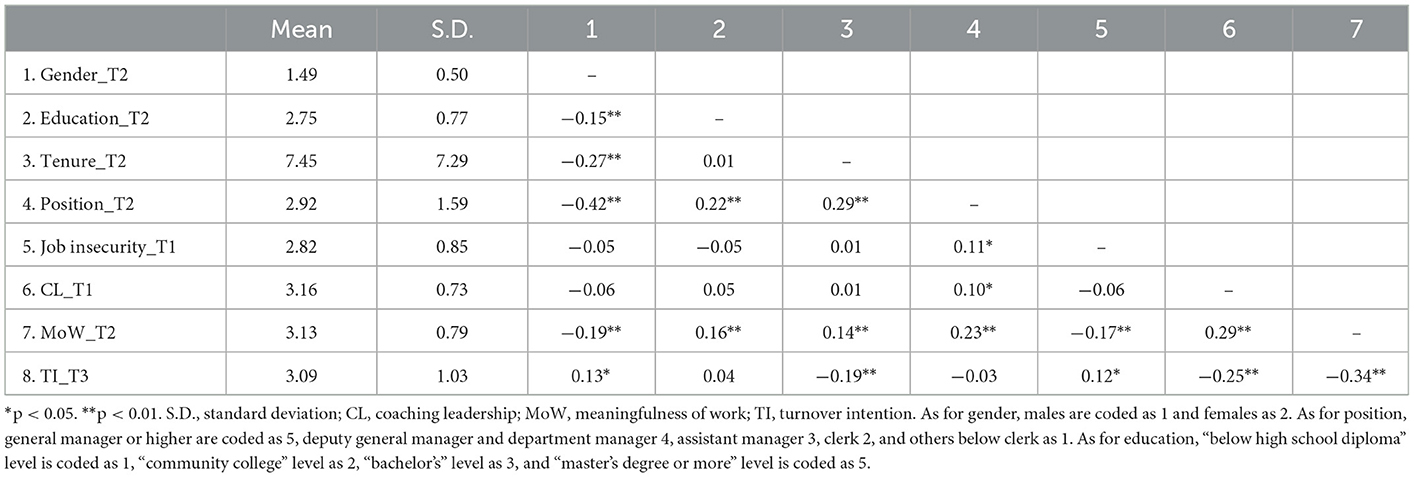

Research variables (job insecurity, coaching leadership, meaningfulness of work, and turnover intention) were significantly related. The correlation analysis results are shown in Table 2.

Measurement model

To test the discriminant validity of the main research variables (job insecurity, coaching leadership, meaningfulness of work, and turnover intention), we performed CFA for all items by checking the measurement model's goodness-of-fit. To be specific, we compared our hypothesized model, a 4-factor model (job insecurity, coaching leadership, meaningfulness of work, and turnover intention), to other alternative models, such as 3-, 2-, and 1-factor models, by conducting a series of chi-square difference tests.

First, the hypothesized 4-factor model had a good and acceptable fit [ = 212.224; CFI = 0.974; TLI = 0.967; RMSEA = 0.051]. Then, we conducted a series of chi-square difference tests by comparing the 4-factor model with a 3-factor model [ = 1239.387; CFI = 0.715; TLI = 0.655; RMSEA = 0.165], a 2-factor model [ = 1699.100; CFI = 0.600; TLI = 0.523; RMSEA = 0.194], and a 1-factor model [ = 1763.298; CFI = 0.584; TLI = 0.508; RMSEA = 0.197]. The results of the chi-square difference tests showed that the 4-factor model was better than others. Thus, this result means that our four research variables have an appropriate degree of discriminant validity.

Structural model

In this study, we built a moderated mediation model including both mediation and moderation structures in the job insecurity–turnover intention relationship. In the mediation structure, the job insecurity–turnover intention relationship is mediated by the degree of employee meaningfulness of work. In the moderation structure, coaching leadership functions as a buffering factor that positively moderates the harmful impact of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work.

Next, in the moderation structure, we multiplied the two variables (i.e., job insecurity and coaching leadership) to make an interaction term between the variables. Before the multiplication, the two variables were centered on their means to decrease the harmful impact of multicollinearity. Such a centering method increases the validity of the moderation analysis by diminishing the degree of multi-collinearity between the variables and minimizing the loss of correlations (78).

To test the impact of the multicollinearity bias, we measured the value of variance inflation factors (VIF) and tolerances (78). The VIF values for job insecurity and coaching leadership were 1.003 and 1.003, respectively. Moreover, the values of tolerance were 0.997 and 0.997, respectively. The results with VIF values smaller than 10 with the tolerance values above 0.2 indicate that job insecurity and coaching leadership are relatively free from the multi-collinearity issue.

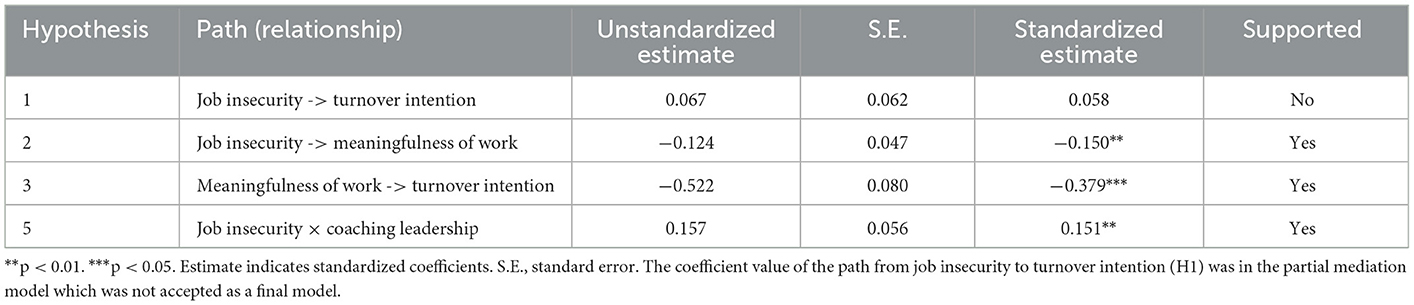

Results of mediation analysis

To find the best mediation model, we compared a full mediation model to a partial mediation model by performing a chi-square difference test. The full mediation model is identical to the partial mediation model except for the direct path from job insecurity to turnover intention. The fit indices of both the full mediation model [χ2 = 254.539 (df = 136), CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.952, and RMSEA = 0.048] and the partial mediation model [χ2 = 253.441 (df = 135), CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.952, and RMSEA = 0.049] were acceptable. However, the chi-square difference test between the models [Δ = 1.098, non-significant] demonstrated that the full mediation model was superior. This result indicates that job insecurity is likely to indirectly influence (e.g., via mediating effect of meaningfulness of work) turnover intention, rather than having a direct impact.

The control variables (tenure, gender, education, and position) were included in the research model to control for the dependent variable, turnover intention. The result showed that only position (β = 0.11, p < 0.05) and tenure (β = −0.18, p < 0.05) were statistically significant.

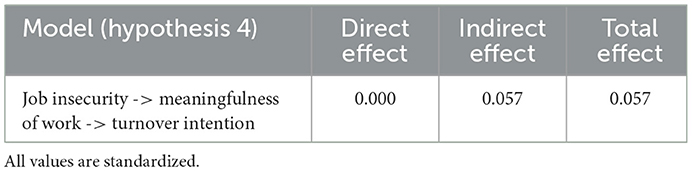

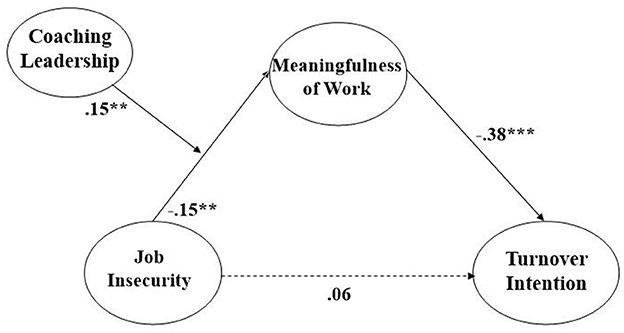

Including the control variables, our research model showed that job insecurity was non-significantly associated with employee's turnover intention (β = 0.06, p > 0.05), which does not support Hypothesis 1. For Hypothesis 1, the coefficient value of the path from job insecurity to turnover intention was in the “partial” mediation model (which was inferior to the full mediation model), not the full mediation model that was finally accepted. This result is consistent with the fact that the model fit indices of full mediation are better than partial mediation. Based on the results of the chi-square difference test between full and partial mediation models as well as the non-significant value of the path coefficient, we conclude that Hypothesis 1 was not supported. In other words, job insecurity is likely to influence turnover intention in an “indirect” way through the mediating effect of various mediators (e.g., meaningfulness of work) rather than in a direct way.

Job insecurity was significantly and negatively associated with employee's meaningfulness of work (β = −0.15, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 2, and that meaningfulness of work is significantly and negatively associated with turnover intention (β = −0.38, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 3 (please see Table 3 and Figure 2).

Figure 2. Coefficient values of our research model (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. All values are standardized).

Bootstrapping

To test the mediation effect of meaningfulness of work in the job insecurity–turnover intention relationship (Hypothesis 4), we conducted bootstrapping analysis with a sample of 10,000 (77). The indirect mediation effect would be significant at a 5% level if the 95% bias-corrected CI for the effect of mean indirect mediation excluded 0 (77).

The results showed that the bias-corrected CI for the mean indirect effect did not include 0 [95% CI = (0.014, 0.109)]. This means that that the indirect mediation effect of meaningfulness of work was statistically significant, supporting Hypothesis 4. The direct, indirect, and total effects of the paths from job insecurity to turnover intention are shown in Table 4.

Result of moderation analysis

We tested the moderation effect of coaching leadership on the relationship between job insecurity and meaningfulness of work. To do so, we conducted a mean-centering process by making an interaction term. The coefficient value of the interaction term (β = 0.18, p < 0.001) was statistically significant. This result means that coaching leadership positively moderates the relationship between job insecurity and job stress by playing a buffering role. Moreover, it indicates that when the level of coaching leadership is high, the decreasing impact of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work is reduced, supporting Hypothesis 5 (please see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Moderating effect of coaching leadership in the job insecurity–meaningfulness of work link.

Discussion

Utilizing 3-wave time-lagged data from 372 employees in South Korea, the current study demonstrated that an employee's meaningfulness of work functions as an important intermediating process (i.e., mediator) in the job insecurity–turnover intention relationship. Moreover, this research empirically determined that coaching leadership plays a buffering role that reduces the harmful influence of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work (i.e., moderator). These results are consistent with the arguments of previous works on job insecurity, meaningfulness of work, turnover intention, and coaching leadership. To be specific, our result that job insecurity functions as a critical antecedent of employee turnover intention is consistent with the extant studies [please see Jiang and Lavaysse (8)]. And our result that job insecurity decreases the degree of meaningfulness of work corresponds with the existing works (45, 46). Also, the result that the diminished meaningfulness of work increases the degree if turnover intention is also consistent with the previous works (52, 59). Lastly, the moderating effect of coaching leadership is consistent with the recent works (63, 67). The reason why the results are consistent with the previous work is that our arguments are based on the proper and validated theoretical background.

This paper may contribute to the literature on job insecurity, meaningfulness of work, turnover intention, and coaching leadership by revealing why (i.e., mediator) and when (i.e., moderator) job insecurity influences turnover intention. In the following sections, we describe the theoretical/practical implications and limitations of the study, also providing suggestions for future research.

Theoretical implications

We believe that the current study may contribute to job insecurity literature from a theoretical perspective. First, the current paper may contribute to job insecurity literature by resolving the inconclusive relationship between job insecurity and organizational outcomes. To address the issue of inclusive results in the job insecurity-organizational outcomes link, we explored the intermediating process (i.e., mediators) and its contingent factor (i.e., moderator) of the relationship (12). As a result, we found and suggest that job insecurity negatively affects organizational outcomes via deteriorating employees' perceptions or attitudes at work (i.e., meaningfulness of work). To be specific, we unveiled the mediating role of employees' meaningfulness of work in the job insecurity–turnover intention link. Furthermore, by empirically validating that coaching leadership plays a buffering role in the relationship between job insecurity and meaningfulness of work, this research can shed light on a contextual or contingent factor which moderate the influence of job insecurity in an organization. We believe that this research can contribute to resolving the inconclusive results of job insecurity by bolstering existing studies that show a detrimental influence of job insecurity on organizational outcomes.

Second, this study attempts to interpret job insecurity from the perspective of positive psychology, by emphasizing the importance of a positive psychological intermediating mechanism (i.e., meaningfulness of work) and its contextual factor (i.e., coaching leadership). In other words, we believe that the current paper may contribute to expanding the scope of job insecurity literature by integrating job insecurity literature with positive psychology literature. In this paper, we demonstrated that an employee's meaningfulness of work, as a representative variable of positive psychology, plays a mediating role in explaining the impact of job insecurity on turnover intention. Thus, this paper reveals that job insecurity significantly diminishes employee positivity (i.e., meaningfulness of work), eventually leading to them leaving the organization. However, this paper also suggests that an employee's positivity in an organization can be recovered and protected through the positivity of the leader, for example, through coaching leadership. Positive leadership behavior can function as a buffering factor, which positively moderates the harmful effect of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work.

Third, the current study demonstrates that leadership plays a critical buffering role in explaining the negative impact of job insecurity. Considering that members in an organization tend to be influenced by their leaders' thoughts, feelings, words, and behaviors when they interpret the meaning of various events, systems, and situations around them (34, 35), leaders can substantially affect employees' perceptions and attitudes toward an important event or situation, such as job insecurity. In other words, leadership will significantly moderate the impact of job insecurity in an organization. Specifically, we show that the harmful influence of job insecurity on meaningfulness of work would be reduced by a high level of coaching leadership. When the level of coaching leadership is high, employees are likely to perceive that they are not alone and separated from their organization. Then, the negative impact of job insecurity can be alleviated. This result indicates that the coaching behaviors of a leader can be an important contingent variable in mitigating the harmful influences of job insecurity.

Practical implications

The current study can provide practical contributions for top management teams who want to understand the influence of job insecurity. First, the result of this paper suggests that top management teams should understand the seriously harmful impact of job insecurity on employees' turnover intention. We empirically demonstrate that job insecurity significantly boosts employees' turnover intention. Given that an employee's turnover is likely to be closely associated with several organizational outcomes, job insecurity substantially diminishes the level of an organization's competitive advantage and sustainability. Therefore, in this paper, we propose that top management teams are required to address and resolve this critical issue carefully by establishing effective and efficient human resource management systems.

Second, we provide useful indicators or criteria (i.e., meaningfulness of work as a mediator in the research model) for top management teams in monitoring and checking the harmful influences of job insecurity as well as the effectiveness of several buffering variables (e.g., coaching leadership, and several practices for decreasing the harmful impacts of job insecurity). Our results empirically demonstrate that the degree of an employee's meaningfulness of work plays the role of mediator in the job insecurity–turnover intention relationship. This indicates that the degree of an employee's meaningfulness of work can be utilized as an important measure or criteria to evaluate how severely job insecurity affects employee turnover intention.

The buffering effect of coaching leadership can also be measured or evaluated by the change of employees' meaningfulness of work. For example, when the level of meaningfulness of work does not change after implementing coaching leadership in an organization, the top management teams may interpret that the buffering influence of coaching leadership will not work adequately. In summary, we propose in this paper that top management teams should monitor the degree of employee meaningfulness of work to check the influences of both job insecurity and its moderating variable (i.e., coaching leadership).

Third, the current study also provides direction for top management teams who attempt to diminish the negative influence of job insecurity in an organization. We suggest that top management teams should understand and properly utilize the positive and buffering effects of coaching leadership. To alleviate the harmful influence of job insecurity, top management teams should apply coaching leadership in their organization. By providing training for coaching leadership behaviors, top management teams can cultivate effective coaching leaders and a coaching culture within an organization. This would significantly contribute to addressing the negative influence of job insecurity.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Although we believe the current study may meaningfully contribute to job insecurity and turnover intention literature, there are still some limitations to be addressed. First, this research could not measure the level of job insecurity in an objective manner as the current study only utilized survey data relying on respondent's self-reporting, which would most likely be subjective. While we acknowledge that the objective phenomena (such as downsizing rate) may not directly influence employees' perceptions and attitudes because the objective characteristic (e.g., downsizing rate) tends to be interpreted through their sense-making processes, the objective measure would be unconsciously reflected in employees' responses. Thus, we suggest that future research needs to utilize both the subjective and objective measures and compare the differential effects of the different measures. Second, this research could not properly consider a number of external factors that substantially affect the degree of job insecurity. There are numerous objective factors that pervade an employee's perception of their subjective job insecurity, such as downsizing rates, the quality or characteristics of human resource management systems, and features of the social security system at the country level (9). Therefore, we suggest that future research should more fully consider the issue by elaborately controlling the objective variables.

Third, although the fundamental values and spirit of coaching leadership may be universal in Western and Eastern societies (79, 80), a number of cultural differences may exist with regard to understanding the role of leadership. These will eventually influence employees' responses toward leadership style. Given that South Korea has been affected by Confucian hierarchy for many centuries, Korean employees may be more familiar with the culture of command and discipline compared to the Western employees (79). As a result, Korean employees are likely to feel that a leader's coaching behaviors are not natural and effective in a real organization. Therefore, the results of the this study should be carefully interpreted.

Conclusion

This research investigated the impact of job insecurity on employees' turnover intention. The results showed that job insecurity promotes the extent of employee turnover intention via the mediating role of meaningfulness of work. Moreover, coaching leadership functions as a positive moderator in the job insecurity–meaningfulness of work relationship. The results indicate that the level of employees' meaningfulness of work is an underlying mechanism in translating job insecurity into turnover intention. In addition, the degree of coaching leadership provides a buffering factor that decreases the negative influence of job insecurity. Although this research has some limitations, we anticipate that the findings will offer a positive contribution to expanding the literature on job insecurity.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Macromill Embrain Group of Ethics Committee. Macromill Embrain Group is the company providing market research service and their approval is sufficient according to the local requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JJ and B-JK contributed by writing the original draft of the manuscript and in the conceptualization, data collection, formal analysis, and methodology. M-JK contributed in the conceptualization, analysis, revision, and in editing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Education and Research promotion program of KOREATECH in 2023.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Julak Lee substantially contributed to developing this paper. We appreciate his great help.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1068293/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sergent K, Stajkovic AD. Women's leadership is associated with fewer deaths during the COVID-19 crisis: quantitative and qualitative analyses of United States governors. J Appl Psychol. (2020) 105:771. doi: 10.1037/apl0000577

2. Spurk D, Straub C. Flexible employment relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Vocat Behav. (2020) 119:103435. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103435

3. Lin W, Shao Y, Li G, Guo Y, Zhan X. The psychological implications of COVID-19 on employee job insecurity and its consequences: the mitigating role of organization adaptive practices. J Appl Psychol. (2021) 106:317. doi: 10.1037/apl0000896

4. Grote G, Pfrombeck J. Uncertainty in aging and lifespan research: Covid-19 as catalyst for addressing the elephant in the room. Work Aging Retire. (2020) 6:246–50.

5. Vander Elst T, Näswall K, Bernhard-Oettel C, De Witte H, Sverke M. The effect of job insecurity on employee health complaints: a within-person analysis of the explanatory role of threats to the manifest and latent benefits of work. J Occup Health Psychol. (2016) 21:65. doi: 10.1037/a0039140

6. De Witte H, Pienaar J, De Cuyper N. Review of 30 years of longitudinal studies on the association between job insecurity and health and well-being: is there causal evidence? Aust Psychol. (2016) 51:18–31. doi: 10.1111/ap.12176

7. Gilboa S, Shirom A, Fried Y, Cooper C. A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: examining main and moderating effects. Pers Psychol. (2008) 61:227–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00113.x

8. Jiang L, Lavaysse LM. Cognitive and affective job insecurity: a meta-analysis and a primary study. J Manag. (2018) 44:2307–42. doi: 10.1177/0149206318773853

9. Kim MJ, Kim BJ. The performance implication of corporate social responsibility: the moderating role of employee's prosocial motivation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3128. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063128

10. Lee C, Huang GH, Ashford SJ. Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. (2018) 5:335–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104651

11. Richter A, Näswall K. Job insecurity and trust: uncovering a mechanism linking job insecurity to well-being. Work Stress. (2019) 33:22–40. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2018.1461709

12. Shoss MK. Job insecurity: an integrative review and agenda for future research. J Manag. (2017) 43:1911–39. doi: 10.1177/0149206317691574

13. Staufenbiel T, König CJ. A model for the effects of job insecurity on performance, turnover intention, and absenteeism. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2010) 83:101–17. doi: 10.1348/096317908X401912

14. Vander Elst T, De Cuyper N, Baillien E, Niesen W, De Witte H. Perceived control and psychological contract breach as explanations of the relationships between job insecurity, job strain and coping reactions: Towards a theoretical integration. Stress Health. (2016) 32:100–16. doi: 10.1002/smi.2584

15. Vander Elst T, Van den Broeck A, De Witte H, De Cuyper N. The mediating role of frustration of psychological needs in the relationship between job insecurity and work-related well-being. Work Stress. (2012) 26:252–71. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2012.703900

16. Sverke M, Låstad L, Hellgren J, Richter A, Näswall K. A meta-analysis of job insecurity and employee performance: testing temporal aspects, rating source, welfare regime, and union density as moderators. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2536. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142536

17. Cheng GH-L, Chan DK-S. Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Appl Psychol Int Rev. (2008) 57:272–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00312.x

18. Stynen D, Forrier A, Sels L, De Witte H. The relationship between qualitative job insecurity and OCB: differences across age groups. Econ Ind Democr. (2015) 36:383–405. doi: 10.1177/0143831X13510326

19. Loi R, Ngo H, Zhang L, Lau VP. The interaction between leader-member exchange and perceived job security in predicting employee altruism and work performance. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2011) 84:669–85. doi: 10.1348/096317910X510468

20. Cameron K, Winn B. Virtuousness. In:Cameron KS, Spreitzer GM, , editors. The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship. Oxford University Press (2012). p. 231–43.

21. Piccoli B, De Witte H. Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: testing psychological contract breach versus distributive injustice as indicators of lack of reciprocity. Work Stress. (2015) 29:246–63. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2015.1075624

22. Gond J-P, El Akremi A, Swaen V, Babu N. The psychological micro-foundations of corporate social responsibility: a person-centric systematic review. J Organ Behav. (2017) 38:225–46. doi: 10.1002/job.2170

23. Jiang L, Probst TM. Organizational communication: a buffer in times of job insecurity? Econ Ind Democr. (2014) 35:557–79. doi: 10.1177/0143831X13489356

24. Lin XS, Chen ZX, Ashford SJ, Lee C, Qian J. A self-consistency motivation analysis of employee reactions to job insecurity: the roles of organization-based self-esteem and proactive personality. J Bus Res. (2018) 92:168–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.028

25. Aguiar-Quintana T, Nguyen THH, Araujo-Cabrera Y, Sanabria-Díaz JM. Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees' self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. Int J Hosp Manag. (2021) 94:102868.

26. Blom V, Richter A, Hallsten L, Svedberg P. The associations between job insecurity, depressive symptoms and burnout: The role of performance-based self-esteem. Econom Indust Democracy. (2018) 39:48–63.

27. Berglund T, Furåker B, Vulkan P. Is job insecurity compensated for by employment and income security? Econom Indust Democracy. (2014) 35:165–84.

28. Cheng T, Huang GH, Lee C, Ren X. Longitudinal effects of job insecurity on employee outcomes: The moderating role of emotional intelligence and the leader-member exchange. Asia Pacific J Manag. (2012) 29:709–28.

29. Darvishmotevali M, Ali F. Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. Int J Hosp Manag. (2020) 87:102462.

30. Schreurs BH, Hetty van Emmerik IJ, Günter H, Germeys F. A weekly diary study on the buffering role of social support in the relationship between job insecurity and employee performance. Hum Resour Manag. (2012) 51:259–79. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21465

31. Sora B, Caballer A, Peiró JM, Silla I, Gracia FJ. Moderating influence of organizational justice on the relationship between job insecurity and its outcomes: A multilevel analysis. Econom Indust Democracy. (2010) 31:613–37.

32. Xiao Z, Wu D, Liao Z. Job insecurity and workplace deviance: the moderating role of locus of control. Soc Behav Pers Int J. (2018) 46:1673–86.

33. Kim MJ, Kim BJ. The performance implications of job insecurity: the sequential mediating effect of job stress and organizational commitment, and the buffering role of ethical leadership. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7837. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217837

34. Lowe KB, Kroeck KG, Sivasubramaniam N. Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature. Leadership Quart. (1996) 7:385–425. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(96)90027-2

35. Schein EH. Organizational Culture and Leadership. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass (2004).

36. Tett RP, Meyer JP. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers Psychol. (1993) 46:259–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00874.x

37. Wright TA, Cropanzano R. Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. J Appl Psychol. (1998) 83:486–93. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.486

38. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. (1989) 44:513–24.

39. Nord WR, Brief AP, Atieh JM, Doherty EM. Work values and the conduct of organizational-behavior. Res Organiz Behav. (1988) 10:1–42.

40. Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE, Debebe G. Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Res Organiz Behav. (2003) 25:93–135. doi: 10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25003-6

41. Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In:Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, , editors. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press (2002). p. 608–18.

42. Brief AP, Nord WR. Work and meaning: Definitions and interpretations. In:Brief AP, Nord WR, , editors. Meanings of Occupational Work: A Collection of Essays. Lexington Books/D. C. Heath and Com (1990). p. 1–19.

43. Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. (1982) 37:122. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

44. Bandura A. Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Dev Psychol. (1989) 25:729. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.729

45. Grant AM, Campbell EM, Chen G, Cottone K, Lapedis D, Lee K. Impact and the art of motivation maintenance: the effects of contact with beneficiaries on persistence behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. (2007) 103:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.05.004

46. Rosso BD, Dekas KH, Wrzesniewski A. On the meaning of work: a theoretical integration and review. Res Organiz Behav. (2010) 30:91–127. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

47. Spreitzer G, Sutcliffe K, Dutton J, Sonenshein S, Grant AM. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organiz Sci. (2005) 16:537–49. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0153

48. Ahmad A. Work-family conflict among junior physicians: its mediating role in the relationship between role overload and emotional exhaustion. J Soc Sci. (2010) 6:265–71. doi: 10.3844/jssp.2010.265.271

49. Gurbuz S, Turunc O, Celik M. The impact of perceived organizational support on work–family conflict: does role overload have a mediating role? Econ Ind Democr. (2013) 34:145–60. doi: 10.1177/0143831X12438234

50. Lee WR, Choi SB, Kang SW. How leaders' positive feedback influences employees' innovative behavior: the mediating role of voice behavior and job autonomy. Sustainability. (2021) 13:1901. doi: 10.3390/su13041901

51. Pearson QM. Role overload, job satisfaction, leisure satisfaction, and psychological health among employed women. J Counsel Dev. (2008) 86:57–63. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2008.tb00626.x

52. Steger MF, Dik BJ, Duffy RD. Measuring meaningful work: the work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J Career Assess. (2012) 20:322–37. doi: 10.1177/1069072711436160

53. Khusanova R, Kang SW, Choi SB. Work engagement among public employees: antecedents and consequences. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:684495. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.684495

54. May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2004) 77:11–37. doi: 10.1348/096317904322915892

55. Thomas KW, Velthouse BA. Cognitive elements of empowerment: an “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad Manag Rev. (1990) 15:666–81. doi: 10.5465/amr.1990.4310926

56. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. (2000) 55:68. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

57. Eisenberger R, Cotterell N, Marvel J. Reciprocation ideology. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1987) 53:743. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.4.743

58. Whitener EM, Brodt SE, Korsgaard MA, Werner JM. Managers as initiators of trust: an exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Acad Manag Rev. (1998) 23:513–30. doi: 10.2307/259292

59. Cropanzano R, Anthony EL, Daniels SR, Hall AV. Social exchange theory: a critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad Manag Ann. (2017) 11:479–516. doi: 10.5465/annals.2015.0099

60. Ellinger AD, Ellinger AE, Keller SB. Supervisory coaching behavior, employee satisfaction, and warehouse employee performance: a dyadic perspective in the distribution industry. Hum Resour Dev Quart. (2003) 14:435–58. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1078

61. Huang JT, Hsieh HH. Supervisors as good coaches: influences of coaching on employees' in-role behaviors and proactive career behaviors. Int JHum Resour Manag. (2015) 26:42–58. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.940993

62. Heslin PA, Vandewalle DON, Latham GP. Keen to help? Managers' implicit person theories and their subsequent employee coaching. Pers Psychol. (2006) 59:871–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00057.x

63. Wang W, Kang SW, Choi SB. Effects of employee well-being and self-efficacy on the relationship between coaching leadership and knowledge sharing intention: a study of UK and US employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:10638. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010638

64. Green LS, Oades LG, Grant AM. Cognitive-behavioral, solution-focused life coaching: enhancing goal striving, well-being, and hope. J Posit Psychol. (2006) 1:142–9. doi: 10.1080/17439760600619849

65. Kim B-J. The influence of coaching leadership on safety behavior: the mediating effect of psychological safety and moderating effect of perspective taking. J Digital Converg. (2022) 20:443–51. doi: 10.14400/JDC.2022.20.5.443

66. Ribeiro N, Nguyen T, Duarte AP, de Oliveira RT, Faustino C. How managerial coaching promotes employees' affective commitment and individual performance. Int J Product Perform Manag. (2020) 70:2163–81. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-10-2018-0373

67. Romão S, Ribeiro N, Gomes DR, Singh S. The impact of leaders' coaching skills on employees' happiness and turnover intention. Administr Sci. (2022) 12:84. doi: 10.3390/admsci12030084

68. Fuller JB, Marler LE, Hester K. Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: Exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. J Organ Behav Int J Indust Occup Organ Psychol Behav. (2006) 27:1089–120. doi: 10.1002/job.408

69. Landers RN, Behrend TS. An inconvenient truth: arbitrary distinctions between organizational, Mechanical Turk, and other convenience samples. Ind Organ Psychol. (2015) 8:142–64. doi: 10.1017/iop.2015.13

70. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Method. (2009) 41:1149–60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

71. Barclay DW, Higgins C, Thompson R. The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adaptation and use as an illustration. Technol Stud. (1995) 2:285–309.

72. Kraimer ML, Wayne SJ, Liden RC, Sparrowe RT. The role of job security in understanding the relationship between employees' perceptions of temporary workers and employees' performance. J Appl Psychol. (2005) 90:389–98. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.389

73. Bunderson JS, Thompson JA. The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Administr Sci Quart. (2009) 54:32–57. doi: 10.2189/asqu.2009.54.1.32

74. Wrzesniewski A, McCauley C, Rozin P, Schwartz B. Jobs, careers, and callings: People's relations to their work. J Res Pers. (1997) 31:21–33.

75. Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. (1988) 103:411–23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

76. Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In:Bollen KA, Long JS, , editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage (1993). p. 136–62.

77. Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. (2002) 7:422–45. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

78. Brace N, Kemp R, Snelgar R. SPSS for Psychologists: A Guide to Data Analysis using SPSS for Windows. 2nd ed. London: Palgrave (2003).

79. Chun JS, Shin Y, Choi JN, Kim MS. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J Manag. (2013) 39:853–77. doi: 10.1177/0149206311419662

Keywords: job insecurity, turnover intention, meaningfulness of work, coaching leadership, moderated mediation model

Citation: Jung J, Kim B-J and Kim M-J (2023) The effect of unstable job on employee's turnover intention: The importance of coaching leadership. Front. Public Health 11:1068293. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1068293

Received: 12 October 2022; Accepted: 13 January 2023;

Published: 16 March 2023.

Edited by:

Evangelos C. Fradelos, University of Thessaly, GreeceReviewed by:

Neuza Ribeiro, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, PortugalSeung-Wan Kang, Gachon University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2023 Jung, Kim and Kim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Byung-Jik Kim, a2ltYmo4MkBidXNpbmVzcy5rYWlzdC5lZHU=; Min-Jik Kim, bWtpbUBrb3JlYXRlY2guYWMua3I=

Jeyong Jung1

Jeyong Jung1 Byung-Jik Kim

Byung-Jik Kim Min-Jik Kim

Min-Jik Kim