- 1Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3University Administrative Office, Guangzhou Huashang College, Guangzhou, China

- 4Department of Sports Training, Xi'an Physical Education University, Xi'an, China

- 5Society Hub, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou), Guangzhou, China

- 6School of Economics and Trade, Guangzhou Huashang College, Guangzhou, China

- 7School of Data Sciences, Guangzhou Huashang College, Guangzhou, China

- 8Managing Director Office, Global Business College of Australia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 9General Manager Office, Edvantage Institute Australia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Aims: This article evaluates the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the 5-item WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) in mainland China.

Methods: Two cross-sectional studies with 1,414 participants from a university in China were conducted. The Chinese version of the WHO-5 was assessed to determine its internal consistency, concurrent validity, factorial validity, and construct validity.

Results: The results indicate that the WHO-5 is unidimensional and has good internal consistency, with Cronbach's a = 0.85 and 0.81 in Study 1 (n = 903) and Study 2 (n = 511), respectively. The findings also demonstrate that the WHO-5 has good concurrent validity with other well-established measures of wellbeing, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and mental wellbeing. The results of confirmatory factor analysis also suggest that the scale has a good model fit.

Conclusions: This study provides empirical data demonstrating that the Chinese version of the WHO-5 has good psychometric properties. The scale can be a useful measure in epistemological studies and clinical research related to wellbeing in Chinese populations.

Introduction

The WHO 5-item Well-Being Index (WHO-5) is a well-known psychological measurement scale that assesses subjective wellbeing through a non-symptomatic and positively worded self-report instrument for a 14-day period (1, 2). The development of the scale began with its longer versions, the WHO-28 and WHO-10 (3–5). By 1998, researchers had successful reduced the instrument to a more user-friendly 5-item scale using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (at no time) to 5 (all of the time) (6). Since then, it has gained worldwide popularity as a screening tool in epidemiological research on areas such as depression, suicidal ideation, infertility, and diabetes (7–9). Recently, numerous studies have applied the WHO-5 to measure comprehensive bio-psychosocial wellbeing (10, 11), indicating an attempt at wider application.

The wider application of the scale depends on its continuous improvement in work by scholars and clinical researchers translating and validating its applicability in Western, Asian, and Latin American countries (6, 11–13). However, in its positive application in various cultures, the construct validity of the WHO-5 has been overlooked (14, 15), with researchers focusing on exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to evaluate the unidimensional latent construct of the scale (16). As such, there are various validation studies on WHO-5 only evaluated the factorial validity of the measure with EFA (9, 17). EFA cannot constrain data, whilst confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) imposes meaningful constraints in assessing the validity of a measure (15). The development and use of CFA was a crucial step in scale validation (18). Yet, surprisingly, WHO-5 assessments using CFA are scarce (1). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first validation study on the Chinese version of WHO-5 with empirical data from two cross-sectional studies using both EFA and CFA to evaluate its construct validity.

This study aimed to fill this gap by conducted two studies. One study evaluated the Chinese version of the WHO-5 with Chinese university students to reveal its psychometric properties. The second study was aimed at validating and confirming the factors in the WHO-5 to reveal its robustness in CFA. Last, the concurrent validity of the WHO-5 with several well-established construct-related concepts related to mental wellbeing (6, 8, 9, 12, 19), life satisfaction, self-esteem, and self-efficacy (1, 20, 21) was also investigated.

Overall, this study provides empirical evidence of the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the WHO-5, as well as evidence confirming its academic development and application. The validation should be beneficial for comprehensive psychological measurements of other student populations in China. The wider application of this validated scale should help practitioners monitor the mental health and wellbeing of Chinese university students.

Materials and Methods

Participants

To evaluate the psychometric properties of the WHO-5, two cross-sectional studies were conducted in a university in Guangdong, China with 1,414 valid participants. We have set 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error when determining the sampling size. The minimum sample size was 377 in the research setting (22). Study 1 took place between June and July 2018 with 903 undergraduate students with an average age of 20.56 years (SD = 2.75 years) who voluntarily participated. The sample comprised 111 male and 792 female participants. In addition, 511 students participated in Study 2 from April to May 2019. The margin of error for the above samples was 3.12% (n = 903) in Study 1 and 4.19% (n = 511) in Study 2. The sample comprised 85.5% female and 14.5% male participants with an average age of 20.41 years (SD = 2.49 years). The gender ratio reflected the overall student demographic profile of the setting.

Both studies used the university's student intranet system to recruit participants and distribute the questionnaire. The collected data stored on the system were completely anonymous. The participants were invited to participate on a voluntary basis. Informed consented was obtained from all of the participants. Parental consent was not required as the participants are all over 18 years old. The participants were allowed to withdraw at any time during the data collection process. The studies were approved by the university's research ethics committee. The entire research process strictly adhered to relevant national and international ethical standards.

Measures

The WHO-5 consists of five items with a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (at no time) to 5 (all of the time) that measure wellbeing. A higher score indicates a higher level of wellbeing (5, 16, 23). The development of the Chinese WHO-5 used standard translation and back-translation procedures by two translators with proficiency in both English and Simplified Chinese (24). To avoid geographical and cross-cultural differences within China, two pilot studies were conducted in Xi'an, Shaanxi and in Guangzhou, Guangdong with 10 pilot participants with at least a degree qualification (25, 26). None of the participants reported any difficulty understanding the questions. The data collected from the pilot studies were excluded from subsequent analysis.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is made up of five items with a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (27–30). The Chinese version of the SWLS was validated by Bai et al. (31) with a nationally representative sample. The Cronbach's alpha in Study 1 and Study 2 are 0.883 and 0.819, respectively.

The Personal Well-Being Index (PWI) is evaluated on an 11-point Likert-type scale (0 = no satisfaction at all to 10 = completely satisfied) with seven questions related to various quality of life domains, including standard of living, health, achieving in life, relationships, safety, community-connectedness, and future security (a = 0.902 in Study 1; 0.916 in Study 2). The original scale developer validated the Chinese version (32). The Cronbach's alpha of PWI in both Study 1 and Study 2 are above the acceptable range with 0.902 and 0.916.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem (RSE) Scale comprises 10 statements (with five items reverse-coded) evaluated using a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree) (33, 34). Wu et al. (34) validated the Chinese version of the RSE with 982 adolescents. The current study also reported the acceptable alpha coefficient (Study 1 = 0.830; Study 2 = 0.755).

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) consists of 10 items on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all true to 4 = exactly true) (35–37). The Chinese version of the GSE has recently been validated (34, 38). The GSE in Study 1 and Study 2 with Cronbach's alpha 0.903 and 0.884, respectively.

The Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS) evaluates hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing with a 5-point scale (1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time) with seven positively worded questions (14, 39). The Chinese version has been validated in both school and clinical settings (40–43). The Cronbach's alpha in Study 1 = 0.884 and Study 2 = 0.824.

Last, the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) contains 12 items to evaluate the severity of health-related problems with a 4-point scale (44). Higher scores indicate worse health. The Chinese version has been validated in various contexts (45, 46). The Cronbach's alpha in Study 1 and Study 2 are 0.773 and 0.751, respectively.

Ethical Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of City University of Hong Kong and Guangzhou Huashang College research ethics committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Procedure

Using data from Study 1 (n = 903) and Study 2 (n = 511), the internal consistency of the WHO-5 was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha (47) and McDonald's omega (48–50), and the corrected item-total correlations between the five items were examined (51, 52).

EFA with principal component analysis was used to evaluate the factorial validity of the WHO-5 (1, 18, 53). To avoid the potential problem of overfitting when conducting EFA and CFA on the same dataset (54), EFA was only conducted on the sample from Study 2 (n = 511). EFA adopted the cut-off values of the Kaiser–Mayer–Olkin (KMO) test (>0.70) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (p < 0.01). In addition, the identified factors should have eigenvalues >1 and their loadings should be >0.350 (51, 55).

The construct validity of the WHO-5 was further evaluated with CFA based on the sample obtained from Study 1 (n = 903) (56). Recent studies on CFA have suggested that the maximum likelihood estimator is inappropriate for a scale measured with ordinal items (57); hence, a diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator was used (58–60) in Model 1 and 2. The recent simulate study recommended that maximum likelihood with mean- and variance-adjusted likelihood ratio test (MLMV) yields better results. Hence, we adopted this estimator in Model 3 (61, 62). The following well-established fit indices were used to evaluate the model fit: comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, and root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08 (51, 63–65). In addition, the ratio of the chi-square test statistic to degrees of freedom, χ2/df ≤ 3, was used to determine an acceptable model fit (66–69) with the exception of Model 3, as the chi-square value of MLMV cannot be used for regular way (70).

Concurrent validity was assessed using the data from both Study 1 (n = 903) and Study 2 (n = 511) along with other validation constructs or measures reported in relevant studies on the WHO-5 (18, 71). Specifically, the WHO-5 has been shown to be significantly positively correlated with life satisfaction, self-esteem, and self-efficacy (1, 20, 21) and negatively correlated with mental health and psychiatric morbidity (6, 8, 12, 19). Hence, the following scales were used to evaluate the concurrent validity of the WHO-5: SWLS, PWI, RSE, GSE, SWEMWBS, and GHQ-12.

The above analyses were conducted using the R (3.6.3) computing environment with the lavaan package 0.6-5 (72), Mplus 8.5 (70), and IBM SPSS 26.0.

Results

Internal Consistency

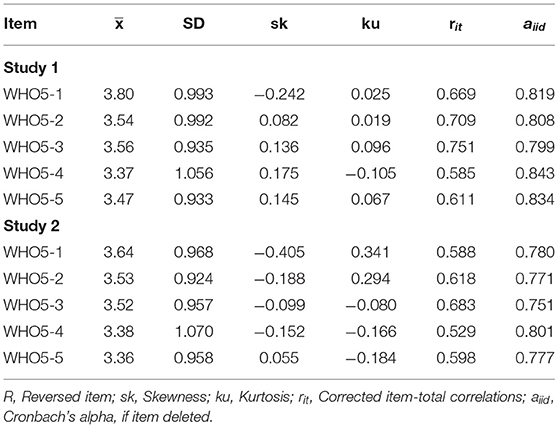

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, corrected item-total correlations, and Cronbach's alpha (if an item was deleted) for the five items of the WHO-5, based on the data from Study 1 (n = 903) and Study 2 (n = 511). The results showed that the WHO-5 had good internal consistency. The corrected item-total correlations for the WHO-5 ranged from 0.585 to 0.751 in Study 1 and from 0.529 to 0.618 in Study 2. The Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega values were above the acceptable range, with a = 0.85 and ω = 0.86 in Study 1 and a = 0.81 and ω = 0.82 in Study 2. There were no significant differences, and relationships were observed in the scale scores by gender, based on the independent-sample t-test and correlation results.

Factorial Validity

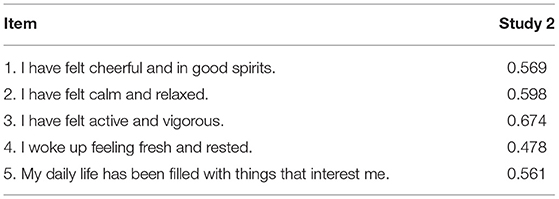

Table 2 illustrates the EFA results using principal component analysis for Study 2 (n = 511). The results of the KMO and Bartlett's test of sphericity for the WHO-5 were 0.804 (χ2 = 833.749, p < 0.001), indicating appropriate scale construction. The scale was unidimensional with only one factor with an eigenvalue >1. The factor loadings ranged from 0.478 to 0.674, explaining 57.593% of the total variance.

Construct Validity

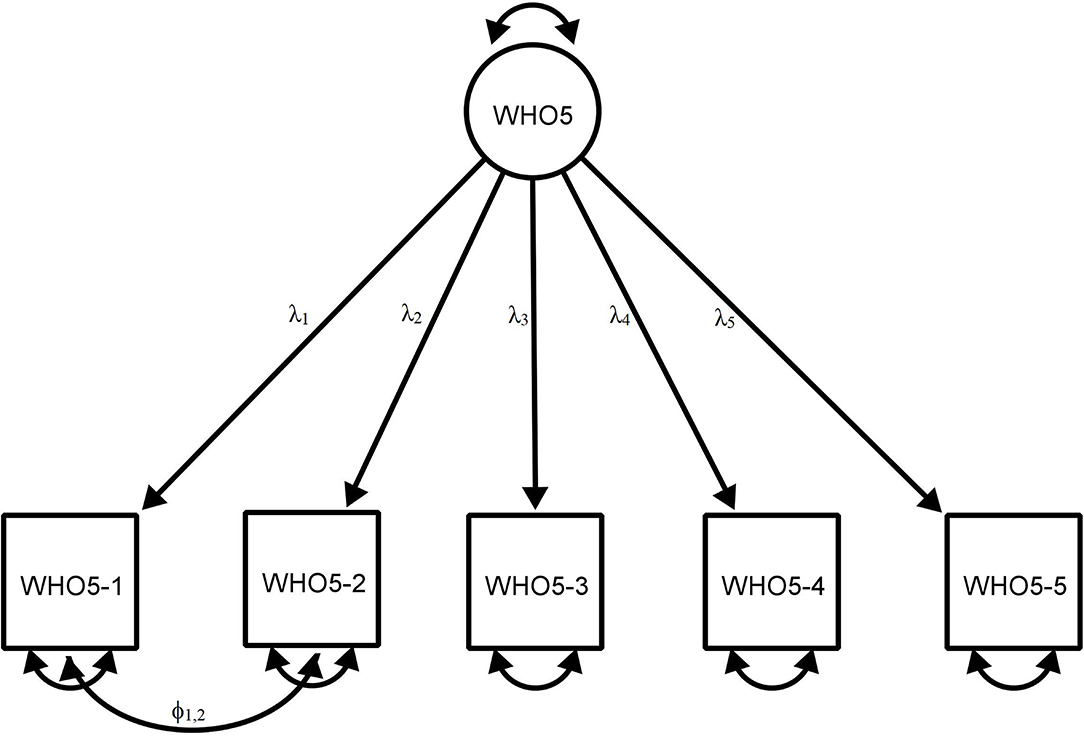

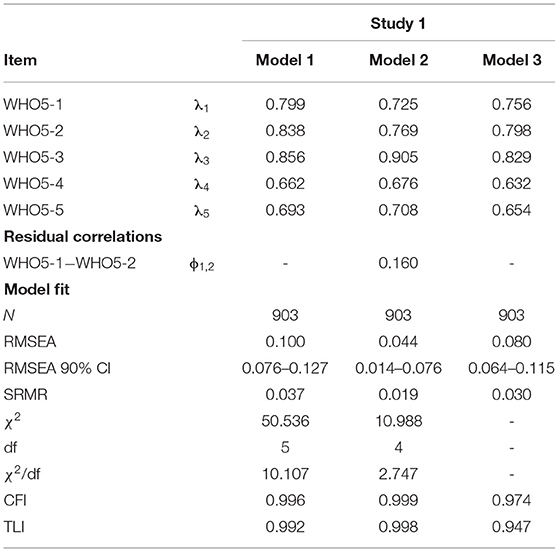

Table 3 and Figure 1 show the CFA results for the WHO-5 based on Study 1 (n = 903). Model 1 evaluated the WHO-5 based on a single factor, without correlating the error terms. The results generally satisfied the criteria for an adequate model fit, with CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.992, and SRMR = 0.037. However, the following two indices failed to fit the model: χ2 (50.536)/5 = 10.107 and RMSEA = 0.100. Following recent studies on the WHO-5 (73), Model 2 re-evaluated the scale, with the error correlations based on the modification indices. It included one covariance factor between the error terms for the WHO5-1 and WHO5-2. The CFA results indicated a good fit of the model, with χ2 (10.988)/4 = 2.747, p < 0.05, SRMR = 0.019, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.998, and RMSEA = 0.044. Model 3 further evaluated the WHO-5 with MLMV estimator without correlated errors. The results indicated that the WHO-5 generally had an adequate fit with a unidimensional factor structure without any post-hoc modifications, with SRMR = 0.030, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.947, and RMSEA = 0.080 (Model 3).

Table 3. Factor loadings and fit indices in confirmatory factor analysis for the WHO-5 (see Figure 1 for estimated model).

Concurrent Validity

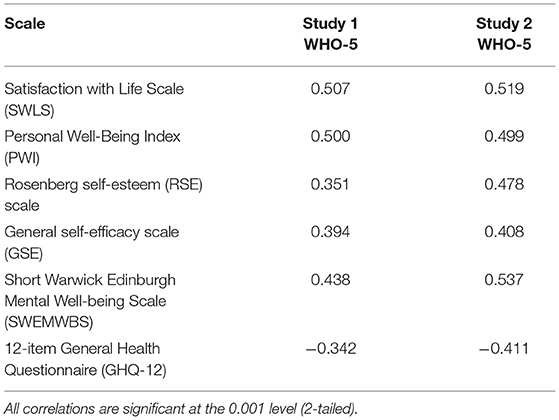

The results of Study 1 (n = 903) replicated the relationships between the WHO-5 and the other construct-related scales suggested in the wellbeing literature (Table 4). In particular, the WHO-5 had significant and strong positive relationships with the SWLS (r = 0.507, p < 0.001) and PWI (r = 0.500, p < 0.001). The RSE (r = 0.351, p < 0.001) and GSE (r = 0.394, p < 0.001) also had a moderate positive relationship with the WHO-5. In general, these results were similar in Study 2 (n = 511).

Regarding the concurrent validity of the WHO-5, the scale was expected to demonstrate a negative relationship with the psychological symptom-related scales. As predicted, the WHO-5 was positively related to the SWEMWBS, a scale in which a lower score indicates psychiatric morbidity, with r = 0.438 (p < 0.001) in Study 1 and r = 0.537 (p < 0.001) in Study 2 (n = 511). The results also demonstrated that the Chinese version of the WHO-5 had a significant moderate negative relationship with the GHQ-12 in Study 1 (r = −0.342, p < 0.001) and Study 2 (r = −0.411, p < 0.001). In summary, the WHO-5 showed good concurrent validity based on Pearson's correlation coefficients.

Discussion

Subjective wellbeing is an important denominator in various mental health issues. The WHO-5 offers a set list for evaluating the effectiveness of treatment with a friendly, easy to understand, and non-invasive assessment. Its wider application to assess psychological responses to various types of disease is apparent in its capacity for early and effective identification. By validating the Chinese version of the WHO-5, this study opens its wider application to investigate the wellbeing of Chinese undergraduate students, such as stress-related issues in work and education settings (2). Specifically, the results of this study showed that the Chinese version of the WHO-5 has good psychometric properties. Indeed, the results indicated that the scale has good internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha values of 0.85 and 0.81 in Study 1 and Study 2, respectively, similar to the values reported in recent WHO-5 studies (ranging from 0.78 to 0.85) based on adolescents and adults in various settings (8, 11, 12, 19, 73). The unidimensional factor structure of the Chinese version of the WHO-5 replicated that of the original WHO-5 (5, 16, 23). The results in this study also showed that the WHO-5 has good concurrent validity with well-established measures related to wellbeing, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and mental wellbeing. In short, the Chinese version of the WHO-5 is suitable for studying the wellbeing of Chinese university students.

This study contributes to the measurement of wellbeing in the following ways. First, this study is one of the first to validate the Chinese version of the WHO-5 for the student population. Although many epistemological studies have used the WHO-5 in Chinese contexts (74–80), there is a paucity of studies validating the Chinese version of the scale. In addition, most of the WHO-5 studies conducted in other countries have focused on clinical populations (1, 9, 12). As such, many existing studies reported that the WHO-5 has been used as outcome measure for the clinical trials amongst the patients with medical conditions related to oncology, endocrinology, otolaryngology, etc. (2). The findings of this study indicated that the WHO-5 is a reliable tool to address mental health challenges in a non-clinical sample, which can contribute to the field of public health.

The second contribution of this study is to provide empirical data to evaluate the construct validity of the WHO-5 through CFA. Validation studies have mainly evaluated construct validity using only EFA (4, 6, 12, 19). However, validation scholars have advocated the use of CFA (18, 38, 81). Many recent studies have demonstrated that scales developed and validated using only EFA may suffer from various methodological issues, such as poor factorial validity and difficulty replicating the factor structure (82, 83). This study conducted two cross-sectional studies to evaluate the scale through both EFA (Study 2) and CFA (Study 1) to avoid the above issues.

This study may have the following limitations. First, the results of this study were based on two cross-sectional studies conducted in a Chinese university located in Guangdong Province in southern China. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to Chinese society or to the Chinese diaspora as a whole. Second, the construct-related measures used in this study are limited by the availability of validated Chinese versions of the scales related to wellbeing, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and mental wellbeing, which may be slightly different from the measures used by the original developers. To overcome this potential limitation, we adopted measures and concepts that have been frequently discussed and applied in WHO-5 studies (1, 6, 8, 9, 12, 19–21). The last potential limitation is related to the post-hoc modifications in CFA to meet all of the criteria for a good model fit. Model 1 (Table 3) reported that SRMR, CFI, and TLI met the criteria for a good model fit and that χ2/df and RMSEA did not. We are fully aware of the discussion about avoiding the use of correlated error terms in CFA without strong justifications (84, 85). Recent WHO-5 validation studies that used CFA have also correlated the error terms (8, 15, 73). This practice has been justified in the literature (86–90). Hence, after correlating the error terms for items 1 and 2, Model 2 showed that the WHO-5 met all of the stringent indices for a good model fit [χ2 (10.988)/4 = 2.747, p < 0.05, SRMR = 0.019, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.044], indicating that the Chinese version has good construct validity. To overcome this limitation, we computed additional CFA analysis with MLMV estimator in Model 3 without correlating any error terms between the items. The results fulfilled the requirement of adequate model fit, with SRMR = 0.030, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.947, and RMSEA = 0.080 (Table 3).

Future studies should include wider population samples, such as young working adults, and non-university youth populations, such as primary and secondary Chinese students. By establishing the broader applicability of the WHO-5 to social work and counseling interventions, the rapid screening enabled by this instrument will provide a viable means of detecting the emotional and psychological wellbeing of young people, making early intervention possible, especially for stress-related issues at work or school. If longitudinal research were conducted, the scale would be available to examine the psychosocial wellbeing of Chinese primary and secondary students. The important data obtained would provide teachers, parents, and students themselves with insight into their psychosocial and emotional health. Another direction could be to compare the subjective wellbeing of primary, secondary, university, and working youth populations at these important stages of development.

Conclusions

In summary, this study validated the Chinese version of the WHO-5. The findings indicate that the scale has good internal consistency, concurrent validity, factorial validity, and construct validity. The results suggest that the Chinese version of the WHO-5 is a valid measure of the mental wellbeing of Chinese university students. The findings may encourage researchers and practitioners to use this scale in epidemiological research. However, additional work is needed to confirm the psychometric properties of the WHO-5 with more generalizable samples in other contexts.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Committee of the Guangzhou Huashang College. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

S-fF has worked in the conception and design of the study. Y-mL, QH, ZX, ZJ, FZ, ZC, KS, HZ, and PY have worked on data collection. S-fF and CK have performed statistical data analyses, interpretation, and have written the article. All authors have critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its last version for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. De Wit M, Pouwer F, Gemke R, Delemarre-Van De Waal HA, Snoek FJ. Validation of the WHO-5 well-being index in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. (2007) 30:2003–6. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0447

2. Topp CW, Ostergaard SD, Sondergaard S, Bech P. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. (2015) 84:10. doi: 10.1159/000376585

3. Bradley C, Lewis KS. Measures of psychological well-being and treatment satisfaction developed from the responses of people with tablet-treated diabetes. Diab Med. (1990) 7:445–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1990.tb01421.x

4. Awata S, Bech P, Koizum Y, Seki T, Kuriyama S, Hozawa A, et al. Validity and utility of the Japanese version of the WHO-Five Well-Being Index in the context of detecting suicidal ideation in elderly community residents. Int Psychoger. (2007) 19:77–88. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004212

6. Love J, Andersson L, Moore CD, Hensing G. Psychometric analysis of the Swedish translation of the WHO well-being index. Qual Life Res. (2014) 23:293–7. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0447-0

7. Bonsignore M, Barkow K, Jessen F, Heun R. Validity of the five-item WHO Well-Being Index (WHO-5) in an elderly population. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2001) 251:27–31. doi: 10.1007/BF03035123

8. Omani-Samani R, Maroufizadeh S, Almasi-Hashiani A, Sepidarkish M, Amini P. The WHO-5 well-being index: a validation study in people with infertility. Iran J Public Health. (2019) 48:2058–64. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v48i11.3525

9. Cichon E, Kiejna A, Kokoszka A, Gondek T, Rajba B, Lloyd CE, et al. Validation of the Polish version of WHO-5 as a screening instrument for depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2020) 159:10. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107970

11. Eser E, Cevik C, Baydur H, Gunes S, Esgin TA, Oztekin CS, et al. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the WHO-5, in adults and older adults for its use in primary care settings. Primary Health Care Res Dev. (2019) 20:7. doi: 10.1017/S1463423619000343

12. Bonnin CM, Yatham LN, Michalak EE, Martinez-Aran A, Dhanoa T, Torres I, et al. Psychometric properties of the well-being index (WHO-5) spanish version in a sample of euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. (2018) 228:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.006

13. Schougaard LMV, De Thurah A, Bech P, Hjollund NH, Christiansen DH. Test-retest reliability and measurement error of the Danish WHO-5 Well-being Index in outpatients with epilepsy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2018) 16:6. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-1001-0

14. Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The warwick-edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2007) 5:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

15. Gudmundsdottir HB, Olason DP, Gudmundsdottir DG, Sigurdsson JF. A psychometric evaluation of the Icelandic version of the WHO-5. Scand J Psychol. (2014) 55:567–72. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12156

16. Bech P, Olsen LR, Kjoller M, Rasmussen NK. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: a comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five Well-Being Scale. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2003) 12:85–91. doi: 10.1002/mpr.145

17. Hochberg G, Pucheu S, Kleinebreil L, Halimi S, Fructuoso-Voisin C. WHO-5, a tool focusing on psychological needs in patients with diabetes: the French contribution to the DAWN study. Diab Metab. (2012) 38:515–22. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.06.002

18. Loewenthal KM. An Introduction to Psychological Tests and Scales. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press (2001).

19. Allgaier AK, Pietsch K, Fruhe B, Prast E, Sigl-Glockner J, Schulte-Korne G. Depression in pediatric care: is the WHO-Five Well-Being Index a valid screening instrument for children and adolescents? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2012) 34:234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.01.007

20. Carrozzino D, Costabile A, Patierno C, Settineri S, Fulcheri M. Clinical psychology in school and educational settings: emerging trends. Mediter J Clin Psychol. (2019) 7:10. doi: 10.6092/2282-1619/2019.7.2138

21. Clarke R, Farina N, Chen HL, Rusted JM, Team IP. Quality of life and well-being of carers of people with dementia: are there differences between working and nonworking carers? Results from the IDEAL program. J Appl Gerontol. (2021) 40:752–62. doi: 10.1177/0733464820917861

22. Maccallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. (1996) 1:130–49. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

23. Bech P. Measuring the dimensions of psychological general well-being by the WHO-5. QoL Newsletter. (2004) 32:15–6. Available online at: https://ogg.osu.edu/media/documents/MB%20Stream/who5.pdf

24. Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. (1970) 1:185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

25. Chang AM, Chau JPC, Holroyd E. Translation of questionnaires and issues of equivalence. J Adv Nurs. (1999) 29:316–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00891.x

26. Cha ES, Kim KH, Erlen JA. Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: issues and techniques. J Adv Nurs. (2007) 58:386–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04242.x

27. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. (1985) 49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

28. Pavot W, Diener E, Colvin CR, Sandvik E. Further validation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. J Pers Assess. (1991) 57:149–61. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_17

29. Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. (1993) 5:164–72. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

30. Pavot W, Diener E. The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. J Posit Psychol. (2008) 3:137–52. doi: 10.1080/17439760701756946

31. Bai XW, Wu CH, Zheng R, Ren XP. The psychometric evaluation of the satisfaction with life scale using a nationally representative sample of China. J Happiness Stud. (2011) 12:183–97. doi: 10.1007/s10902-010-9186-x

32. The International Wellbeing Group. Personal Wellbeing Index. 5th ed. Melbourne, VIC: Australia Center on Quality of Life, Deakin University (2013).

33. Rosenberg M, Schooler C, Schoenbach C. Self-esteem and adolescent problems: modeling reciprocal effects. Am Sociol Rev. (1989) 54:1004–18. doi: 10.2307/2095720

34. Wu Y, Zuo B, Wen FF, Yan L. Rosenberg self-esteem scale: method effects, factorial structure and scale invariance across migrant child and urban child populations in China. J Pers Assess. (2017) 99:83–93. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2016.1217420

35. Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. (1982) 37:122–47. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

36. Schwarzer R, Bäßler J, Kwiatek P, Schröder K, Zhang JX. The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: comparison of the german, spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Appl Psychol. (1997) 46:69–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01096.x

37. Scholz U, Dona BG, Sud S, Schwarzer R. Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. (2002) 18:242–51. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.18.3.242

38. Zeng G, Fung S, Li JW, Hussain N, Yu P. Evaluating the psychometric properties and factor structure of the general self-efficacy scale in China. Curr Psychol. (2020) 11. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00924-9. [Epub ahead of print].

39. Stewart-Brown S, Tennant A, Tennant R, Platt S, Parkinson J, Weich S. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2009) 7:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-15

40. Dong A, Chen X, Zhu L, Shi L, Cai Y, Shi B, et al. Translation and validation of a Chinese version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale with undergraduate nursing trainees. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2016) 23:554–60. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12344

41. Dong A, Zhang XX, Zhou HT, Chen SY, Zhao W, Wu MM, et al. Applicability and cross-cultural validation of the Chinese version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale in patients with chronic heart failure. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2019) 17:11. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1120-2

42. Fung S. Psychometric evaluation of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS) with Chinese University Students. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2019) 17:46. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1113-1

43. Sun YY, Luk TT, Wang MP, Shen C, Ho SY, Viswanath K, et al. The reliability and validity of the Chinese Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale in the general population of Hong Kong. Qual Life Rese. (2019) 28:2813–20. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02218-5

44. Goldberg DP, Williams P. A User's Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-NELSON (1988).

45. Ye SQ. Factor structure of the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): the role of wording effects. Pers Individ Dif. (2009) 46:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.027

46. Liang Y, Wang L, Yin XC. The factor structure of the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) in young Chinese civil servants. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2016) 14:9. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0539-y

47. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. (1951) 16:297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555

49. Zinbarg RE, Revelle W, Yovel I, Li W. Cronbach's alpha, Revelle's beta, and McDonald's (omega H): their relations with each other and two alternative conceptualizations of reliability. Psychometrika. (2005) 70:123–33. doi: 10.1007/s11336-003-0974-7

50. Revelle W, Zinbarg RE. Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the glb: comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika. (2009) 74:145–54. doi: 10.1007/s11336-008-9102-z

53. Jennrich RI, Sampson PF. Rotation for simple loadings. Psychometrika. (1966) 31:313–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02289465

54. Fokkema M, Greiff S. How performing PCA and CFA on the same data equals trouble overfitting in the assessment of internal structure and some editorial thoughts on it. Eur J Psychol Assess. (2017) 33:399–402. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000460

55. Field AP. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications (2018).

56. Jöreskog KG. A general approach to confirmatory maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. (1969) 34:183–202. doi: 10.1007/BF02289343

57. Lionetti F, Keijsers L, Dellagiulia A, Pastore M. Evidence of factorial validity of parental knowledge, control and solicitation, and adolescent disclosure scales: When the ordered nature of Likert scales matters. Front Psychol. (2016) 7:941. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00941

58. Distefano C, Morgan GB. A comparison of diagonal weighted least squares robust estimation techniques for ordinal data. Struct Eq Model A Multidiscip J. (2014) 21:425–38. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.915373

59. Li C-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods. (2016) 48:936–49. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

60. Wong DSW, Fung S. Development of the cybercrime rapid identification tool for adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134691

61. Maydeu-Olivares A. Maximum likelihood estimation of structural equation models for continuous data: standard errors and goodness of fit. Struct Eq Model Multidiscip J. (2017) 24:383–94. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2016.1269606

62. Gao CJ, Shi DX, Maydeu-Olivares A. Estimating the maximum likelihood root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with non-normal data: a monte-carlo study. Struct Eq Model Multidiscip J. (2020) 27:192–201. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2019.1637741

63. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model Multidiscip J. (1999) 6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

64. Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. J Educ Res. (2006) 99:323–38. doi: 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

65. Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. 2nd Ed. New York, NY: Guilford Publications (2014).

66. Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull. (1980) 88:588–606. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

67. Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates (1998).

68. Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. (2001) 66:507–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02296192

69. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press (2005).

71. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. (2000) 25:3186–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

72. Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. (2012) 48:36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

73. Perera BPR, Jayasuriya R, Caldera A, Wickremasinghe AR. Assessing mental well-being in a Sinhala speaking Sri Lankan population: validation of the WHO-5 well-being index. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2020) 18:9. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01532-8

74. Chow KM, Tang WKF, Chan WHC, Sit WHJ, Choi KC, Chan S. Resilience and well-being of university nursing students in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Educ. (2018) 18:8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1119-0

75. Liu L, Li SP, Zhao Y, Zhang JL, Chen G. Health state utilities and subjective well-being among psoriasis vulgaris patients in mainland China. Qual Life Res. (2018) 27:1323–33. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1819-2

76. Li Z, Dai JM, Wu N, Gao JL, Fu H. The mental health and depression of rural-to-urban migrant workers compared to non-migrant workers in Shanghai: a cross-sectional study. Int Health. (2019) 11:S55–63. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihz081

77. Gao JL, Zheng PP, Jia YN, Chen H, Mao YM, Chen SH, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:10. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3541120

78. Liu SY, Huang J, Dong QL, Li B, Zhao X, Xu R, et al. Diabetes distress, happiness, and its associated factors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with different therapies. Medicine. (2020) 99:8. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018831

79. Li X, Li Y, Xia B, Han Y. Pathways between neighbourhood walkability and mental wellbeing: a case from Hankow, China. J Trans Health. (2021) 20:18. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2021.101012

80. Wang CP, Lu YC, Hung WC, Tsai IT, Chang YH, Hu DW, et al. Inter-relationship of risk factors and pathways associated with chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a structural equation modelling analysis. Public Health. (2021) 190:135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.02.007

81. Fung S, Fung ALC. Development and evaluation of the psychometric properties of a brief parenting scale (PS-7) for the parents of adolescents. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228287

82. Fung S, Chow EOW, Cheung CK. Development and validation of a brief self-assessed wisdom scale. BMC Geriatr. (2020) 20:8. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1456-9

83. Leeman TM, Knight BG, Fein EC, Winterbotham S, Webster JD. An evaluation of the factor structure of the Self-Assessed Wisdom Scale (SAWS) and the creation of the SAWS-15 as a short measure for personal wisdom. Int Psychoger. (2021) 1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220004202. [Epub ahead of print].

84. Hermida R. The problem of allowing correlated errors in structural equation modeling: concerns and considerations. Comput Methods Soc Sci. (2015) 3:5–17. Avilable online at: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/ntuntcmss/vol3-iss1-15-005.htm

85. Van Den Eijnden RJJM, Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM. The social media disorder scale. Comput Human Behav. (2016) 61:478–87. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038

86. Shah R, Goldstein SM. Use of structural equation modeling in operations management research: looking back and forward. J Operat Manag. (2006) 24:148–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2005.05.001

87. Cole DA, Ciesla J, Steiger J. The insidious effects of failing to include design-driven residuals in latent-variable covariance structure analysis. Psychol Methods. (2008) 12:381–98. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.4.381

88. Fung S. Revisiting the dimensionality of the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale in Mainland China. Soc Behav Pers. (2020) 48:12. doi: 10.2224/sbp.8619

89. Fung S, Chow EOW, Cheung CK. Development and evaluation of the psychometric properties of a brief wisdom development scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082717

Keywords: wellbeing, WHO-5, CFA, Chinese, validation, student

Citation: Fung S-f, Kong CYW, Liu Y-m, Huang Q, Xiong Z, Jiang Z, Zhu F, Chen Z, Sun K, Zhao H and Yu P (2022) Validity and Psychometric Evaluation of the Chinese Version of the 5-Item WHO Well-Being Index. Front. Public Health 10:872436. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.872436

Received: 09 February 2022; Accepted: 08 March 2022;

Published: 30 March 2022.

Edited by:

Wing Fai Yeung, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Makoto Kyougoku, Kibi International University, JapanTomás Caycho-Rodríguez, Universidad Privada del Norte, Peru

Copyright © 2022 Fung, Kong, Liu, Huang, Xiong, Jiang, Zhu, Chen, Sun, Zhao and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sai-fu Fung, c2ZmdW5nQGNpdHl1LmVkdS5oaw==; orcid.org/0000-0002-3526-6568

Sai-fu Fung

Sai-fu Fung Chris Yiu Wah Kong

Chris Yiu Wah Kong Yi-man Liu2,3

Yi-man Liu2,3 Qian Huang

Qian Huang