94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 10 March 2025

Sec. Cognitive Science

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1495456

Trust is a multidimensional and dynamic social and cognitive construct, considered the glue of society. Gauging someone’s perceived trustworthiness is essential for forming and maintaining healthy relationships across various domains. Humans have become adept at inferring such traits from speech for survival and sustainability. This skill has extended to the technological space, giving rise to humanlike voice technologies. The inclination to assign personality traits to these technologies suggests that machines may be processed along similar social and vocal dimensions as human voices. Given the increasing prevalence of voice technology in everyday tasks, this systematic review examines the factors in the psychology of voice acoustics that influence listeners’ trustworthiness perception of speakers, be they human or machine. Overall, this systematic review has revealed that voice acoustics impact perceptions of trustworthiness in both humans and machines. Specifically, combining multiple acoustic features through multivariate methods enhances interpretability and yields more balanced findings compared to univariate approaches. Focusing solely on isolated features like pitch often yields inconclusive results when viewed collectively across studies without considering other factors. Crucially, situational, or contextual factors should be utilised for enhanced interpretation as they tend to offer more balanced findings across studies. Moreover, this review has highlighted the significance of cross-examining speaker-listener demographic diversity, such as ethnicity and age groups; yet, the scarcity of such efforts accentuates the need for increased attention in this area. Lastly, future work should involve listeners’ own trust predispositions and personality traits with ratings of trustworthiness perceptions.

Digitisation is changing the way modern societies interact and communicate. The use of artificial intelligence and speech synthesis has entered many domains of our daily life, such as autonomous vehicles, automated customer support, telehealth and companion robots, and smart home assistants. Considering that trust is a key factor in the acceptance of technology (Bryant et al., 2020; Large et al., 2019; Seaborn et al., 2022) as well as the healthy functioning of a flourishing society, it makes the multi-disciplinary research area of trustworthy voice acoustics of growing importance and relevance. Overall, existing literature suggests that speech acoustics influence first impressions of speakers’ perceived trustworthiness (Tsantani et al., 2016; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017; Stewart and Ryan, 1982; Nass and Lee, 2000). Nonetheless, when biological, demographic, cultural, and situational factors are not adequately considered, the overall findings often remain inconclusive. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that aims to understand the relationship between voice acoustics and attributions of trustworthiness in humans and machines.

By merely hearing a stranger’s voice, such as a telemarketer, we tend to form instant impressions of their identity, discerning cues like gender, age, accent, emotional state, personality traits (e.g., perceived trustworthiness), and even hints about their health condition (cf. Nass and Brave, 2005; Kreiman and Sidtis, 2011). Voice, the carrier of speech, allows us to perceive human traits through auditory signals generated during speech production. Physiologically, during speech production, airflow from the lungs is transformed into sound waves by vocal fold vibrations in the larynx, and these waves are shaped by the vocal tract’s articulators, producing the diverse sounds of speech, cf. source-filter theory (Lieberman et al., 1992; Kamiloğlu and Sauter, 2021).

Table 1 exhibits certain acoustic features and how speech acoustics shape first impressions during social interactions (Bachorowski and Owren, 1995; Weinstein et al., 2018; Maltezou-Papastylianou et al., 2022; Shen et al., 2020; Cascio Rizzo and Berger, 2023). Voice quality features such as Harmonic-to-noise ratio (HNR), jitter, shimmer, cepstral peak prominence (CPP) and long-term average spectrum (LTAS) tend to be indicative of the perceived roughness, breathiness or hoarseness of a voice, often seen in vocal aging and pathologies research (Da Silva et al., 2011; Linville, 2002; Jalali-najafabadi et al., 2021; Farrús et al., 2007; Chan and Liberman, 2021). Moreover, past studies seem to suggest that each attributed speaker trait may follow a different time course in terms of stimulus duration (McAleer et al., 2014; Mahrholz et al., 2018; Lavan, 2023). For instance, dominance attributions seem to develop as early as 25 milliseconds (ms), while trustworthiness and attractiveness attributions are strengthened gradually over exposure periods ranging from 25 ms to 800 ms (Lavan, 2023).

Trust has been shown to influence perceptions of first impressions (Freitag and Bauer, 2016), personal relationships (Ter Kuile et al., 2017), work performance (Brion et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2014), cooperation and sense of safety within communities (Castelfranchi and Falcone, 2010; Krueger, 2021). While extensive literature discusses trust models, most are theoretical (Harrison McKnight and Chervany, 2001; Mayer et al., 1995), offering varying definitions encompassing expected actions (Gambetta, 2000), task delegation (Mayer et al., 1995), cooperativeness (Yamagishi and Yamagishi, 1994; Yamagishi, 2003; Deutsch, 1960), reciprocity (Ostrom and Walker, 2003), and “encapsulated interest” (Maloy, 2009; Hardin, 2002; Baier, 2014). Current research tends to explore trust as either a single-scale or multi-dimensional concept, often focusing on the three-part relation of “A trusts B to do X,” within specific contexts (cf. Bauer and Freitag, 2018). Intrinsically, trustee B’s perceived trustworthiness to do X is shaped by trustor A’s dispositional, learned and situational trust factors, risk assessment and beliefs towards the trustee, such as gender stereotyping in relation to different occupations and contexts (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2000; Smith, 2010; Seligman, 2000; Freitag and Bauer, 2016; Castelfranchi and Falcone, 2010). Furthermore, social trust formation tends to lean towards a dichotomised view, namely generalised and particularised trust (cf. Freitag and Traunmüller, 2009; Schilke et al., 2021; Uslaner, 2002). Overall, trusting someone or perceiving them as trustworthy can be expressed as the trustor’s reliance on a trustee (e.g., an individual, a community, an organisation or institution), with the belief or expectation of behaving in a manner that contributes to the trustor’s welfare (e.g., by assisting in the completion of a task) or at least not against it (e.g., sharing a secret). In turn, this helps support or induce a sense of mutual benefit between them, all the while, taking into account the situational context and the trustor’s predispositions.

Throughout this review, the terms trustor / listener / participant, and trustee / speaker may be used interchangeably.

Although there are a series of multi-disciplinary variations in past research aimed to capture the true essence of trust, it all boils down to two methods: (a) explicit measures of trust attitudes and behaviours through self-assessments using rating scales. These scales can be dichotomous (e.g., yes/no answers), probabilistic (i.e., ratings from 0 to 100%) or following a Likert scale format (Rotter, 1967; Knack and Keefer, 1997; Soroka et al., 2003); (b) implicit behavioural measures through the use of the prisoner’s dilemma game and the trust game experiment (also known as the investment game) derived from behavioural economics and games theory (Berg et al., 1995; Deutsch, 1960). Explicit measures of trust have also become a standardised practise in assessing one’s propensity to trust and perceived trustworthiness (Glaeser et al., 2000; Bauer and Freitag, 2018; Naef and Schupp, 2009; Kim, 2018).

Previous behavioural and cognitive research, including studies on voice perception and production, has emphasized the significance of sample sizes and research environments. Samples of 24–36 participants per condition tend to reliably yield high agreement between participant ratings (Lavan, 2023; McAleer et al., 2014; Mileva et al., 2020), while both online and lab-based experiments have provided comparable data quality (Del Popolo Cristaldi et al., 2022; Germine et al., 2012; Uittenhove et al., 2023; Honing and Reips, 2008).

Humans naturally attribute social traits to others, including animals and even artificially intelligent entities (i.e., agents) like humanoid robots, virtual assistants, and chatbots. Consequently, research on human-agent interaction (HAI) emphasizes studying human behaviour for designing interactive intelligent agents (IAs), with voice playing a crucial role in attributing social traits, as seen in the “Computers as Social Actors” (CASA) paradigm (Nass et al., 1994; Lee and Nass, 2010; Seaborn et al., 2022). The “uncanny valley” phenomenon further illustrates this, describing the uneasiness felt when an IA looks or sounds almost human but not quite (Mori, 1970; Mori et al., 2012).

Speech production in technological settings tends to refer to either canned speech (i.e., unchangeable pre-recorded speech samples) or synthesised speech, both seen in voice research (Nass and Brave, 2005; Kaur and Singh, 2023; Clark et al., 2019; Cambre and Kulkarni, 2019; Weinschenk and Barker, 2000; Kang and Heide, 1992). Past studies in HAI have revealed a positive relationship between perceptions of trustworthiness, rapport, learning and vocal entrainment (i.e., adapting one’s vocal features to sound more similar to the person they are talking to) (Cambre and Kulkarni, 2019). Further studies supporting the effects of voice acoustics in IAs and trustworthiness have observed (1) a connection between vocal pitch and trustworthiness (Elkins and Derrick, 2013), (2) a preference towards more “natural” humanlike IA voices (Seaborn et al., 2022), and (3) the influence of the similarity-attraction effect. The similarity-attraction effect exhibits a preference and more positive attitudes towards speakers that are perceived to be more similar to the participant (Nass and Brave, 2005; Dahlbäck et al., 2007; Nass and Lee, 2000; Clark et al., 2019). For instance, Dahlbäck et al. (2007) observed a preference towards voice-based IAs that matched the listeners’ own accent regardless of the IA’s actual level of expertise, strengthening the case of people assigning human traits and predispositions to IAs.

Therefore, trustworthiness perceptions in voice-based IAs mirror those in human voices. Accordingly, trustors’ dispositional, learned, and situational trust towards IAs, alongside IAs’ perceived competence and ease of use should also be taken into account. Additional factors affecting trustworthiness attributions like perceived risk, especially regarding security, privacy, and transparency, also hold significance (Razin and Feigh, 2023), often examined through models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and its variations (cf. Riener et al., 2022; Nam and Lyons, 2020).

Finally, trust propensity in HAI is often measured using scales like the Negative Attitudes to Robots (NARS) (Nam and Lyons, 2020; Jessup et al., 2019). Overall, measurements of trustworthiness perceptions in HAI tend to follow the same methods laid out in the previous section with some alterations to match the technological aspect. For instance, sometimes a Wizard of Oz experiment is conducted for implicit measures, where during HAI the researcher either partly or fully operates the agent, while the participant is unaware, thinking the agent acts autonomously (Dahlbäck et al., 1993; Riek, 2012).

Given the above, this systematic review attempts to consolidate the existing multi-disciplinary literature on voice trustworthiness in both human and synthesised voices. Specifically, this review aims to address the question of “how do acoustic features affect the perceived trustworthiness of a speaker?,” while also reviewing participant demographics, voice stimuli characteristics and task(s) involved.

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Page et al., 2021a,b). The search was performed on the 31st of October 2022, and all studies were initially identified by electronic search. Searches were repeated on the 18th January 2024 to identify any additional publications. A pre-registration protocol has been created for this review on the Open Science Framework (OSF1) under the CC-by Attribution 4.0 International license.

This review adopted a narrative synthesis approach, to consolidate findings across studies investigating vocal trustworthiness in human speakers and voice-based IAs. The decision to use narrative synthesis was informed by the research objective, which focused on identifying and summarising acoustic features, demographic characteristics, and task paradigms across studies, rather than deriving effect sizes or pooled estimates. This approach allowed for a comprehensive examination and categorisation of findings into themes to identify trends, gaps, and contextual nuances in the literature, and inform future research directions.

Five bibliographic databases (Scopus, PsycInfo, ACM, ProQuest, PubMed) were searched using tailored search syntax detailed in Table 2, guided by the question: “How do acoustic features affect the perceived trustworthiness of a speaker?.” Queries, developed collaboratively by all authors, have focused on English-language records published until January 18, 2024, using Boolean operators and wildcards for optimal search. Additional records were identified through manual searches, citation chaining, and exploration of Scholar database, books, and conference proceedings.

Full-text papers have been obtained for titles and abstracts deemed relevant, based on specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Papers were independently screened by CMP and SP, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Studies were included if: (a) participants were adults, irrespective of ethnicity, nationality, age and gender; (b) the study design involved a quantitative or mixed-methods approach; and (c) examined variables and reported outcomes focused on the acoustic characteristics of a speaker, with respect to their perceived trustworthiness.

Studies were excluded if: (a) reported outcomes did not focus on acoustic cues in relation to perceptions of trustworthiness of a human or IA; (b) characteristics of participants, stimuli and tasks involved could not be obtained; (c) the study design followed a qualitative-only approach; and (d) only the abstract was written in English, while the main paper was written in a language other than English.

Extracted information was divided into three categories accompanied by the publication’s title and a reference key: (a) study characteristics, containing data such as the author, publication year, country that the study has taken place, number of participants, the aim of the study, vocal cues examined, task(s) involved, analyses and outcome; (b) listener characteristics, relating to the demographics of participants; (c) stimuli characteristics, including details of the stimulus itself and speaker demographics.

The methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies were assessed using a tailored scoring rubric adapted from Leung et al. (2018). The assessment evaluated risk of bias across five domains: conceptual clarity, reliability, internal validity, external validity, and reproducibility. Each domain covers specific criteria, scored from 0 to 2 points (0 = high risk of bias, 1 = moderate risk of bias, 2 = low risk of bias), detailed in Supplementary material. The maximum possible score for a study was 18 points (9 criteria × 2 points). The findings from the risk of bias assessment can be found in the Results section. Note that, such risk-of-bias scales do not necessarily reflect the quality of the evidence collected and used in the respective studies per se, or the reliability or quality of the studies involved more generally. Rather, they reflect “risk” in terms of how and what appears presented in the final publications, as filtered through the present authors’ ability to extract these points from the respective manuscripts in the structured manner dictated by the scoring tool.

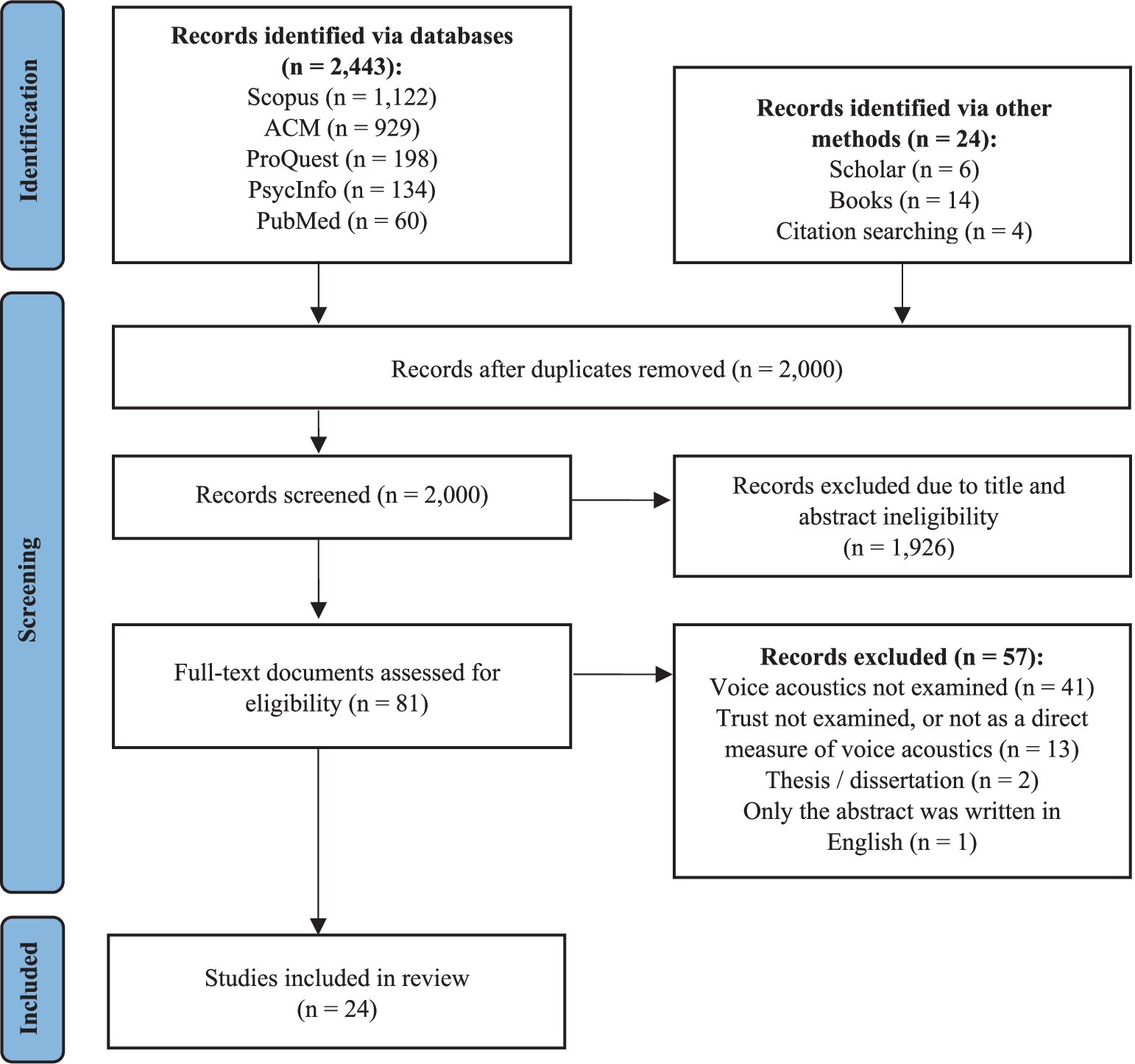

Electronic and hand searches have identified 2,467 citations, of which 2,000 unique ones have been screened via Rayyan software (Ouzzani et al., 2016). Following elimination of duplicates, 81 potentially relevant citations remained. After full-text review and application of inclusion criteria, 57 citations have been excluded, resulting in 24 eligible studies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Identification of included studies in the systematic review, following the PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., 2021a,b).

The 24 studies have been published between 2012 and 2024 and were conducted across Europe, America and Asia—nine in the UK, six in the US, two in Poland and one study each in France, Canada, China, Japan and Singapore, while two remain unclear (see Table 3). Eight of those are conference proceedings (Torre et al., 2016; Tolmeijer et al., 2021; Muralidharan et al., 2014; Maxim et al., 2023; Lim et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2023; Elkins et al., 2012; Klofstad et al., 2012) and the remaining 16 are journal publications. Among them, 14 studies have focused on perceived trustworthiness in terms of human speakers and the remaining 10 in terms of voice-based IAs. Twenty-one studies have focused on the effects of vocal pitch or pitch-related features with 12 of them incorporating the additional properties of pitch range, intonation, glide, formant dispersion, harmonic differences, HNR, jitter, shimmer, MFCCs, alpha ratio, loudness, pause duration and speech rate (see Table 4). Four studies solely focused on either speech duration or speaking rate.

Most studies used Likert scales, typically in the rage of 1–7, to assess perceived trustworthiness (see Table 4). Some employed implicit decision tasks, while others combined explicit and implicit measures. Regression models, including linear mixed models and logistic regression, were common for exploring vocal acoustics and trustworthiness. Pearson’s correlations assessed relationship strength. ANOVA, t-tests, and occasionally PCA or mixed methods were used for analysis.

Only one study examined age-group differences, i.e., adults older and younger than 60 years old (Schirmer et al., 2020). As seen in Tables 3, 5, 11 studies had fewer than 100 participants (Schirmer et al., 2020; Elkins et al., 2012; Mileva et al., 2020; Ponsot et al., 2018; Mileva et al., 2018; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017; O'Connor and Barclay, 2018; Deng et al., 2024; Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023; Muralidharan et al., 2014), six with up to 50 (Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023; Mileva et al., 2018; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017; Muralidharan et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2023; Ponsot et al., 2018). Ten studies had 100–550 participants (Lim et al., 2022; Tolmeijer et al., 2021; Torre et al., 2020; Baus et al., 2019; Mahrholz et al., 2018; McAleer et al., 2014; Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012; Belin et al., 2019; Maxim et al., 2023; Klofstad et al., 2012), while one had over 2,000 (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022). Most used audio-only stimuli, but seven used audio-visual (Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012; Elkins et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2022; Mileva et al., 2020; Maxim et al., 2023; Deng et al., 2024; Mileva et al., 2018). Five studies created over 100 usable stimuli (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022; Mahrholz et al., 2018; Schirmer et al., 2020; Ponsot et al., 2018; Torre et al., 2016) (see Table 6).

As indicated in the “Theme” column of Table 4, all 24 studies have been assigned a thematic (i.e., contextual) category based on shared situational attributes to provide more clarity and relevance during the discussion of their findings. Specifically, during the review stage, the situational factors of each study were examined. These factors were derived from either the study’s inherent task (e.g., customer-barista interaction or fire warden simulation scenarios) or the meaning conveyed by the uttered stimuli (e.g., election speech, or generic greeting). They played a key role in qualitatively grouping studies that shared similar situational contexts. For instance, the “public communication” theme has examined interactions involving public speaking in conferences (Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012), student elections (Mileva et al., 2020), or a political context (Schirmer et al., 2020; Klofstad et al., 2012). This iterative process was aimed to uncover consistent patterns and variations in how vocal acoustic features like pitch, amplitude, and intonation influence trustworthiness perceptions within specific, similar situational contexts.

Ultimately, seven distinct thematic categories were derived from this approach. These categories spanned a spectrum from generic first impressions, such as greetings and factual statements (Baus et al., 2019; Belin et al., 2019; McAleer et al., 2014; Mileva et al., 2018; Ponsot et al., 2018; Tsantani et al., 2016; Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022; Mahrholz et al., 2018; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017), to specific domains such as public communication (Schirmer et al., 2020; Klofstad et al., 2012; Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012; Mileva et al., 2020), social behaviour (O'Connor and Barclay, 2018), customer service (Tolmeijer et al., 2021; Muralidharan et al., 2014; Lim et al., 2022), financial services (Torre et al., 2020; Torre et al., 2016), telehealth advice (Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023; Maxim et al., 2023) and safety procedures (Kim et al., 2023; Deng et al., 2024; Elkins et al., 2012).

The total risk of bias scores for the 24 reviewed studies ranged from 8 to 16 out of a maximum of 18 points, with a mean, median and mode of 12 (SD = 2.5). Eight studies (33%) scored between 14 and 16 points, 12 studies (50%) scored between 9 and 13 points, and four studies (17%) scored 8 points (see Table 4).

Conceptual clarity was a consistent domain of weakness, with only six studies providing a clear and explicit definition of trust or trustworthiness (Deng et al., 2024; Elkins et al., 2012; Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023; Kim et al., 2023; Lim et al., 2022; Muralidharan et al., 2014). The majority relied on implicit or vague conceptualisations, potentially limiting the interpretability and comparability of findings across studies. Reliability demonstrated notable variation, with only nine studies (38%) achieving the maximum score of 4 for using validated tools for measuring acoustic features and reporting intra- or inter-rater reliability (Baus et al., 2019; Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023; Elkins et al., 2012; Klofstad et al., 2012; Mahrholz et al., 2018; Schirmer et al., 2020; McAleer et al., 2014; Mileva et al., 2018; Mileva et al., 2020).

Majority of studies scored highly on internal validity due to clear randomisation or pseudo-randomisation procedures, stimuli quality and justified sample sizes. External validity emerged as a widespread limitation, with only three studies (13%) scoring highly for diverse speaker and listener samples (Baus et al., 2019; Schirmer et al., 2020; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017). Most studies were restricted to narrow demographic groups. Reproducibility was a strength, with 19 studies (75%) earning maximum scores due to detailed methodological descriptions.

Overall, the assessment highlighted strengths in the reproducibility domain and weaknesses in the domains of conceptual clarity and external validity. Greater attention to defining trust and trustworthiness, diversifying speakers and listeners, and improving methodological transparency is needed to strengthen the robustness and applicability of future research. For more information, see Tables 4–6, while the full scoring criteria and explanations for individual study scores are available in Supplementary material.

In this review, vocal pitch has emerged as a predominant focus across all 24 included studies, followed by investigations into amplitude, intonation, HNR, jitter, shimmer, speech duration, and/or speech rate. To facilitate a comprehensive discussion, findings have been categorised into sections on human speakers and voice-based IAs, grouping relevant studies accordingly.

The interpretation of study outcomes has been significantly shaped by contextual factors, leading to the qualitative grouping of studies into thematic (i.e., contextual) categories. Each thematic category summarises findings on acoustic features and their implications for perceptions of trustworthiness within specific contexts or situations, as detailed further in the discussion. For instance, studies within the “telehealth advice” theme have examined trustworthy voice acoustics in scenarios involving medication guidance and mental wellness practices. This thematic approach has facilitated the identification of consistent patterns and variations in how vocal acoustic features contribute to communication dynamics and shape perceptions of trustworthiness within specific contexts. Without these situational considerations, the overall findings across studies seemed to be inconclusive.

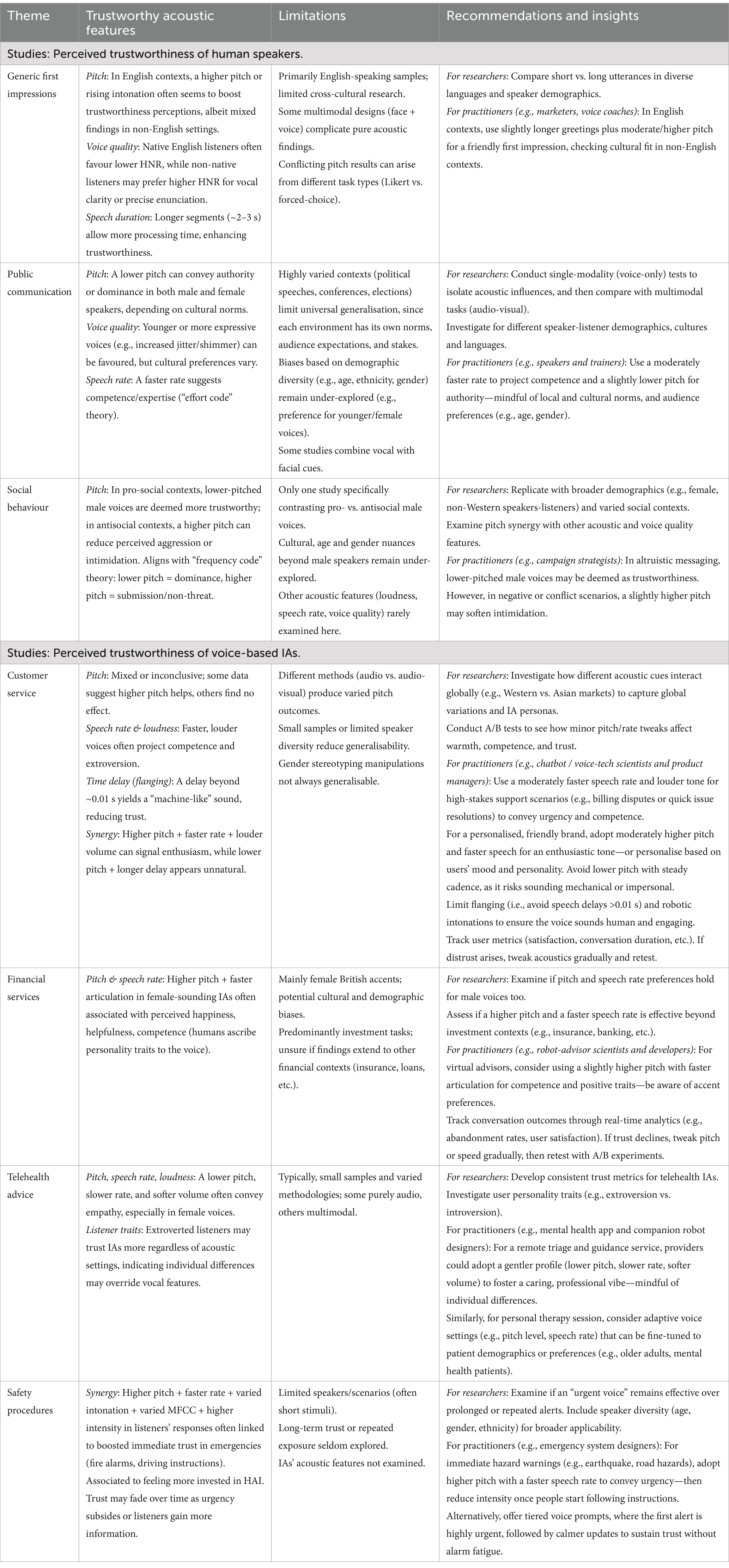

In total, seven contextual themes have been identified (also see Table 4). Three of these themes are evident in human speaker studies: “generic first impressions” (e.g., from greetings to factual statements), “public communication,” and “social behaviour.” The remaining four themes are identified in voice-based IA studies: “customer service,” “financial services,” “telehealth advice,” and “safety procedures.” For a summary of findings see Table 7.

Table 7. Summary of trust-related acoustic features in human and IA studies: Actionable insights for practitioners and recommendations for future research.

Thirteen of the 24 studies have focused on perceived trustworthiness of adult human voices. Six have solely assessed pitch-related measures (Mileva et al., 2018; Tsantani et al., 2016; O'Connor and Barclay, 2018; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017; Belin et al., 2019; Ponsot et al., 2018), four have combined pitch with HNR, jitter, shimmer, loudness, formant dispersion, or speech rate (Baus et al., 2019; McAleer et al., 2014; Schirmer et al., 2020; Mileva et al., 2020), two have focused solely on speech duration (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022; Mahrholz et al., 2018), and one on speaking rate (Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012).

All studies have used explicit measures like rating scales, with 7-point (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022; Schirmer et al., 2020; O'Connor and Barclay, 2018; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017) and 9-point (Baus et al., 2019; McAleer et al., 2014; Mileva et al., 2018; Mileva et al., 2020) Likert scales being common. Analyses have included correlational, inferential, and regression models (details in Table 4). While some studies have linked trustworthiness to lower or higher pitch independent of gender, others have noted gender’s influence. Building on the premise of situational factors, the following part of this subsection presents a discussion on study findings, categorised thematically according to contextual similarities.

Nine of the studies on human voice trustworthiness have focused on generic first impression scenarios, using a variety of audio stimuli (e.g., greetings such as the word “hello,” or snippets from The Rainbow Passage (Fairbanks, 1960)). The main aspects that have been studied under this theme include pitch and related features like intonation and glide (Baus et al., 2019; McAleer et al., 2014; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017), and some have also considered voice quality features (Baus et al., 2019; Belin et al., 2019; McAleer et al., 2014; Mileva et al., 2018; Ponsot et al., 2018; Tsantani et al., 2016). Two studies specifically, have only analysed speech duration (e.g., comparison between shorter and longer sentences or words) (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022; Mahrholz et al., 2018).

Current findings have primarily suggested a positive link between pitch, rising intonation at both ends of a stimulus and trustworthiness attributions in English-speaking contexts (McAleer et al., 2014; Belin et al., 2019). Nevertheless, cultural differences seem to be prevalent, as mixed findings for pitch have been identified for non-English speaking studies (Baus et al., 2019; Ponsot et al., 2018; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017). Multimodal research (i.e., faces and voices) has also yielded inconclusive results regarding pitch’s impact, noting that there may be a stronger influence of faces in such cases (Mileva et al., 2018). Moreover, methodological differences seem to have played a role in the current findings: English-speaking studies using Likert scales have favoured higher pitch for trustworthiness, whereas research utilising a 2AFC task (Tsantani et al., 2016) has deemed lower pitch as more trustworthy. Further research comparing these methodologies is necessary for a clearer understanding.

Significant findings have centered on HNR, revealing cultural disparities based on English-speaking stimuli: native listeners seem to favour lower HNR for trustworthiness (McAleer et al., 2014), whereas non-native listeners seem to prefer higher HNR (Baus et al., 2019), regardless of the speaker’s gender. Voice quality features tend to be sensitive in respect to voice quality pathologies and physiological changes that occur in aging (Farrús et al., 2007; Felippe et al., 2006; Ferrand, 2002; Rojas et al., 2020; Jalali-najafabadi et al., 2021), which may account for these preferences. For instance, native listeners may gravitate more towards youthful-sounding voices, which may promote more positive or upbeat impressions. In contrast, non-native listeners, may prioritise vocal clarity and precision in foreign speech that usually comes with a higher HNR. Considering that cross-cultural vocal trustworthiness studies seem to be scarce, further investigations are warranted for a more comprehensive understanding.

Both studies examining speech duration have indicated that longer stimuli, around 2–3 s, tend to be perceived as more trustworthy than shorter ones, e.g., a vowel or a word (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022; Mahrholz et al., 2018). However, one of them (Mahrholz et al., 2018) has added that even stimuli as short as 0.5 s can convey trustworthiness, consistent with previous research (Lavan, 2023; McAleer et al., 2014). Moreover, these perceptions appear to be consistent across cultures, such as Polish (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022) and Scottish (Mahrholz et al., 2018) speakers. A potential explanation for these findings may relate to longer speech duration potentially allowing for more thorough processing, thus influencing trust perceptions, as well as introducing more opportunities for response variability among listeners (Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022). Having said that, further cross-cultural studies are still needed for definitive conclusions.

Four studies seem to fall under this theme category, which either tackle trustworthiness judgments in terms of public speaking in conferences (Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012) and student elections (Mileva et al., 2020), or in terms of stimuli with a political context (Schirmer et al., 2020; Klofstad et al., 2012).

One of those studies (Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012) has assessed trustworthiness perceptions based solely on the speech rate of a female speaker in Japan, finding a preference for faster speech. Despite using Singaporean English speakers and listeners, a second study has reached similar conclusions (Schirmer et al., 2020). In support of these findings, past research, including the “effort code” theory, suggest that faster speech rates tend to convey greater knowledge and expertise (Smith and Shaffer, 1995; Rodero et al., 2014; Gussenhoven, 2002). Consequently, boosting speakers’ perceived confidence, credibility, and persuasiveness, particularly in public speaking contexts. Additionally, these findings may also be indicative of listeners’ preference towards younger speakers, considering that slower speech rate tends to be more associated with aging (Schirmer et al., 2020).

The aforementioned Singaporean study (Schirmer et al., 2020) has also shown a preference for voices with lower pitch and HNR, but higher jitter, shimmer, and intensity range. This is the only study that has explicitly explored age differences, revealing a preference for younger speakers and a general preference for female speakers across ages. The contradictory lower HNR, higher jitter and shimmer preferences though, may stem from perceived expressiveness or individual and cultural influences on vocal aesthetic preferences. Conversely, a UK study under this theme (Mileva et al., 2020) has yielded inconclusive results, potentially due to their multimodal design (faces and voices). Their multimodality makes it more difficult for a direct comparison with the previous, unimodal (i.e., voice-only) studies, and to interpret their findings.

Lastly, two studies (Schirmer et al., 2020; Klofstad et al., 2012) have exhibited a preference for lower-pitched voices regardless of gender, which may potentially be influenced by individual and cultural norms of vocal aesthetic appeal. An alternative interpretation for lower-pitched female voices may be that they sound more dominant and thus, perceived as more authoritative, confident, and competent (Ohala, 1983; Klofstad et al., 2012).

The only study under this theme has explored male voices in pro-social and anti-social scenarios (O'Connor and Barclay, 2018). Lower-pitched voices have been noted as more trustworthy in positive contexts and higher-pitched voices in negative contexts. These observations were partly explained in terms of higher pitch potentially mitigating the perceived intimidation of antisocial behaviour in men (O'Connor and Barclay, 2018). This seems to align with the “frequency code” theory, where higher-pitched voices tend to signal smaller body sizes, primarily seen in women and children; thus potentially conveying a friendlier or less threatening demeanour (Ohala, 1983; Ohala, 1995).

Altogether, vocal cues in human voices seem to play a significant role in trustworthiness attributions, albeit influenced by contextual factors. It is further suggested that vocal cues may have stronger effects when voice acts as the sole or primary modality for drawing trustworthiness inferences.

The remaining 11 studies in this review focused on assessing the perceived trustworthiness of voice-based Intelligent Agents (IAs), whether using synthesised or pre-recorded human voices. Similar to human speakers, voice-based IAs are often evaluated with human behaviour in mind, with context also playing a significant role. Contextual themes and associated acoustic features for trustworthy speech are discussed further.

Three voice-based IA studies examining trustworthiness attributions fall under this theme category. Contexts vary from barista scenarios (Lim et al., 2022) to task-assistance scenarios (Tolmeijer et al., 2021; Muralidharan et al., 2014).

Findings on pitch have been inconclusive, which may partly stem from differences in study designs; one study used audio-visual stimuli with correlational analyses (Lim et al., 2022), while the other two employed audio-only stimuli with inferential models (Tolmeijer et al., 2021; Muralidharan et al., 2014). Tolmeijer et al. (2021) has also focused extensively on gender-stereotyping, manipulating synthetic voices to sound more masculine, feminine, or gender-ambiguous. The lack of pitch significance in trustworthiness perceptions in these studies, suggests that listeners may not rely solely on pitch for voice-based IAs in assistive roles. These findings challenge the importance of vocal pitch in shaping trustworthiness perceptions of IAs.

Past research (Muralidharan et al., 2014) has suggested that combining pitch and flanging (i.e., speech time delay manipulation) influences trustworthiness perceptions. They have found that a lower pitch range with greater time delay tends to be perceived as more machine-like and less trustworthy compared to natural human speech. They added that human speech typically has a natural time delay of about 0.01 s, and increasing this delay can make it sound less natural. This deviation, along with a less animated voice, may lead to uneasiness in listeners, supporting theories on social inferences from HAI (Mori, 1970; Mori et al., 2012; Nass et al., 1994; Muralidharan et al., 2014).

Furthermore, a louder voice with a faster speech rate and higher pitch tends to be perceived as more trustworthy, supporting theories linking trust formation with positive traits (Lim et al., 2022). Faster speech rate tends to portray speakers’ deeper understanding and passion for the subject. In combination with higher pitch it is usually associated with extroversion and openness (Ohala, 1995; Lim et al., 2022; Maxim et al., 2023), further portraying speakers as competent, persuasive, and credible (Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012; Smith and Shaffer, 1995; Rodero et al., 2014; Gussenhoven, 2002). Only one study has examined listeners’ trust propensity, revealing positive and negative associations with trustworthiness attributions dependent on the scales used (Lim et al., 2022). Overall findings under this theme seem to be appropriate if we interpret them as listeners being more accepting and trusting of speakers’ assistance on a task. Nonetheless, more extensive research is needed in this area before these findings can be deemed as generalisable.

Both studies (Torre et al., 2020; Torre et al., 2016) in this theme employed implicit investment tasks, with one also using a 7-point Likert scale (Torre et al., 2020). Both have assessed female-only voices with various British accents and used regression models for analysis.

Findings have indicated that higher pitch and faster articulation rate seem to be associated with more trustworthiness. Additionally, they have linked higher pitch to positive emotions such as happiness. These findings seem to align with past research linking greater articulatory effort to higher perceptions of knowledge, confidence, and helpfulness (Gussenhoven, 2002). The preference for higher-pitched voices in female IAs strengthens the case of attributing human traits to IAs, as women typically have higher-pitched voices due to physiological factors. Past research has also exhibited a preference for higher-pitched women, linking them with positive traits like attractiveness and trustworthiness (Lavan, 2023; McAleer et al., 2014). The current findings may also strengthen the case for humans assigning gender roles to assistive occupations, even in HAI (Tolmeijer et al., 2021).

Two studies have explored trustworthiness judgments in receiving advice for medication (Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023) and mental wellness (Maxim et al., 2023) contexts.

While one has focused on vocal pitch of male and female IA using audio-only, the other has examined pitch, speech rate, and loudness of a female IA with audio-visual stimulus. Despite no reported acoustic significance for trustworthiness, a trend towards lower pitch, speech rate, and volume in female voices is observed. Additionally, extroverted listeners have offered higher ratings overall, irrespective of speakers’ perceived traits (Maxim et al., 2023).

Authors seem to have attributed these observations to voice similarity with mental health professionals, suggesting softer, empathetic, and confident perceptions (Maxim et al., 2023). Moreover, slower speech rate and lower volume, which are often associated with physiological changes occurring in aging (Lavan et al., 2019; Rojas et al., 2020; Heffernan, 2004; Ferrand, 2002; Baus et al., 2019; McAleer et al., 2014). As such, speakers may have also been perceived as older and probably more knowledgeable. These findings further highlight HAI drawing inferences from human-human interactions and linking trustworthiness to positive traits. Nonetheless, limited stimuli and differing methodologies between the two studies may affect their generalizability. For instance, Maxim et al. (2023) examined the similarity-attraction effect among other aspects and employed a multi-modal design (i.e., faces and voices), which makes it more difficult for a direct comparison with the second, unimodal (i.e., voice-only) study (Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023), and to interpret their findings.

The last three studies on voice-based IAs explored attributions of trustworthiness employing scenarios such as security screening (Elkins et al., 2012), fire warden simulation (Kim et al., 2023) and voice assistance during driving simulation (Deng et al., 2024).

All three studies have associated higher vocal pitch with increased trustworthiness in voice-based IAs, albeit varying in their methodology. Two of them have assessed trustworthiness through participants’ verbal responses during HAI (Elkins et al., 2012; Deng et al., 2024). They have reported that higher-pitched responses with greater pitch and MFCC variability, higher intensity, and longer response time may correspond to higher trustworthiness ratings. These findings may relate to participants developing more positive perceptions of the IA, in terms of dominance, authoritativeness and competence, and feeling more invested during HAIs as per the “effort code” theory (Ohala, 1983; Klofstad et al., 2012; Gussenhoven, 2002). However, these effects seem to diminish with prolonged HAI, possibly due to the accumulation of information and the opportunity to make further inferences over time (Elkins et al., 2012). While these studies provide valuable insights, pre-assessing participants’ trust propensity and personality traits could enhance conclusions. The final study (Kim et al., 2023), which examined the acoustics of voice-based IAs instead, has similarly reported that higher pitch with faster speech rate and variable intonation has prompted higher trustworthiness ratings, labelling that combination of acoustics as an “urgent voice.”

Granted that these three studies have offered limited stimuli, which like previously mentioned, might not be sufficient to draw generalised conclusions to the broader population. Nevertheless, despite methodological variances, all of them have consistently reported similar results. This consistency may be attributed to the heightened vocal urgency observed in speakers during emergency situations, which could also be perceived as more authoritative, eager to assist, and concerned with everyone’s safety (Yokoyama and Daibo, 2012; Smith and Shaffer, 1995; Rodero et al., 2014; Gussenhoven, 2002).

All things considered, vocal cues of voice-based IAs seem to be playing a significant role in attributions of trustworthiness. However, contextual and situational factors are equally prevalent in this section as in research on human voices, enhancing the interpretability of findings. It is further highlighted the influence of human-human interactions and social inferences from human behaviour when studying HAIs. Finally, majority of the HAI studies had less than a hundred participants (Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023; Muralidharan et al., 2014; Elkins et al., 2012; Torre et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2023; Deng et al., 2024), and only one study had more than 5 speakers (Torre et al., 2016) making their findings potentially more difficult to generalise to the wider population, even though they were reported to be well-powered.

The 24 papers identified in this review, represent the body of existing research in relation to speech acoustics and perceptions of trustworthiness. Our conclusions are drawn from a comprehensive synthesis of all available evidence.

Studies varied in participant numbers, with 13 involving less than 100 participants and 6 of those having less than 50 (see Table 5). Regarding speakers, most studies had 5 or fewer speakers, with 8 having 60 or fewer; see Table 6 for a summary of the stimuli and Table 3 for the descriptive statistics of participants and speakers across all reviewed studies. While participant sample sizes may appear limited, past research supports sample sizes of 24–36 per condition (Lavan, 2023; McAleer et al., 2014; Mileva et al., 2020). Most studies have used explicit, self-reported tasks, with some attempting real-life scenario recreation for additional behavioural data. More effort may be needed for capturing a wider range of contexts.

Most studies have relied on convenience sampling from student populations, raising concerns about demographic diversity and external validity. This sampling approach may not represent the broader population, potentially impacting the generalisability of findings. Consequently, variations in sample size and recruitment methods could have contributed to the polarised research outcomes identified, with a potential bias towards younger white generations. Moreover, online experiments have been proposed as viable alternatives to lab-based studies, offering comparable data quality and potentially better generalisability and ecological validity depending on the research question and recruitment characteristics (Del Popolo Cristaldi et al., 2022; Germine et al., 2012; Uittenhove et al., 2023; Honing and Reips, 2008).

Future research should address limitations in sample characteristics of both speakers and listeners to enhance demographic diversity and generalisability. Methodological limitations of existing studies should be acknowledged and addressed to improve the reliability of reported outcomes. Additionally, future research should explore the relationship between perceived trustworthiness based on listeners’ voice ratings and their trust propensity, as well as individual differences in listeners and speakers. Cross-examinations should be expanded to include a wider range of demographic factors such as age, accents, ethnicity, and nationality, while also considering their disposition towards trust. Rigorous mixed-methods study designs should be employed to provide comprehensive insights into the effects of past and current behaviours on trustworthiness perceptions from voice acoustics, ensuring conclusive findings. Moreover, current research lacks studies examining speakers’ own self-perceptions of producing trustworthy speech, which could complement existing literature on listeners’ trustworthiness attributions.

Furthermore, the qualitative thematic categorisation has highlighted disparities in the depth of exploration on voice trustworthiness across different situational contexts. While themes like generic first impressions (Baus et al., 2019; Belin et al., 2019; McAleer et al., 2014; Mileva et al., 2018; Ponsot et al., 2018; Tsantani et al., 2016; Groyecka-Bernard et al., 2022; Mahrholz et al., 2018; Oleszkiewicz et al., 2017) seem to have received substantial attention, others such as telehealth advice (Goodman and Mayhorn, 2023; Maxim et al., 2023), financial services (Torre et al., 2020; Torre et al., 2016) and customer service (Tolmeijer et al., 2021; Muralidharan et al., 2014; Lim et al., 2022) seem to be comparatively under-explored. This highlights the need for future research to address these gaps and expand our understanding of how vocal acoustic features influence trustworthiness perceptions across diverse contexts.

Overall, this systematic review highlights both shared and unique aspects of how trustworthiness is perceived in human voices and voice-based IAs. For human voices, judgements of trustworthiness emerge from a complex blend of acoustic features, social inferences, and interactional context. In contrast, voice-based IAs rely more on engineered acoustic profiles, yet they, too, are often evaluated along human-like social dimensions. As shown in Tables 4, 7, factors such as pitch, speech rate, loudness, and voice quality can be tuned to elicit or reduce trust, with different combinations proving more effective in specific scenarios (e.g., faster, louder delivery for customer service; slower, softer voices for telehealth). Moreover, Table 7 consolidates common acoustic features across both human and IA voices, demonstrating how certain cues, when appropriately balanced, can transcend medium or modality to influence trustworthiness perceptions.

Given these overlapping mechanisms, the need for comparative research on human and IA voices is more pressing than ever. Trust remains central to social cohesion and collaboration; thus, as voice-based IAs increasingly permeate telehealth (e.g., mental health triaging, companion robots or wellbeing apps), customer service (e.g., call centre chatbots, dispute resolution voice-based IAs), financial services (e.g., AI-driven robot advisors, voice-based personal budgeting IAs, automated insurance underwriting), and even self-driving vehicles (e.g., real-time hazard alerts and route guidance), there is a growing need to adapt these technologies so they inspire and sustain user trust—see Table 7 for actionable insights per industry. Moreover, since everyday tasks now blur the boundaries between human and machine interactions, understanding how we attribute trust to non-human voices is both academically significant and practically essential. A dual focus on human and synthesised voices can offer valuable insights into the cognitive processes guiding trust judgements, ultimately shaping the development of more effective, natural-sounding AI voices. By aligning voice design more closely with human-like trust cues, these systems will be better equipped to function ethically and efficiently in an increasingly technological society.

This paper has systematically reviewed 24 studies to explore the impact of vocal acoustics on perceived trustworthiness in both human speakers and voice-based IAs, shedding light on human behaviour and attitudes toward vocal communication.

In summary, acoustic features appear to correlate with trustworthiness judgments in both human and IA voices, albeit they may exert more pronounced effects when the voice serves as the sole or predominant modality for inferring trustworthiness. Moreover, their effects are best understood within their intended contexts for enhanced interpretability. Overall, pitch seems to be influential when assessed in combination with other acoustic features, while as a sole factor it appears to be less reliable. Additionally, HAI seems to draw social inferences from human-human interactions, listeners’ trust propensity and personality traits. Hence, highlighting the importance of studying these factors side by side.

To conclude, a comprehensive approach is needed to advance research on voice trustworthiness for more robust and well-rounded insights, as discussed in more detail in the limitations section of the discussion. Firstly, by considering dispositional and situational trust attitudes alongside current measures. Secondly, by cross-examining individual differences and demographic diversity in speaker-listener samples. Thirdly, there seems to be a gap in existing research regarding studies that explore speakers’ self-perceptions of delivering speech with trustworthy intent, a facet that could complement the existing literature on listeners’ attributions of trustworthiness. Lastly, by expanding the study of voice trustworthiness across diverse situational contexts, researchers can deepen insights into communication nuances and trustworthiness perceptions in contexts that have been less frequently investigated. See Table 7 for a more detailed summary of findings, paired with actionable insights for practitioners and recommendations for future research.

In closing, this review serves as a valuable reference for policymakers, researchers, and other interested parties. It offers insights into the current state of research while highlighting existing gaps and suggesting directions for future multi-disciplinary investigations.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

CM-P: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RS: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1495456/full#supplementary-material

Bachorowski, J.-A., and Owren, M. J. (1995). Vocal expression of emotion: acoustic properties of speech are associated with emotional intensity and context. Psychol. Sci. 6, 219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00596.x

Bauer, P. C., and Freitag, M. (2018). “Measuring trust” in The Oxford handbook of social and political trust. ed. E. M. Uslaner (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 15.

Baus, C., McAleer, P., Marcoux, K., Belin, P., and Costa, A. (2019). Forming social impressions from voices in native and foreign languages. Sci. Rep. 9:414. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36518-6

Belin, P., Boehme, B., and McAleer, P. (2019). Correction: the sound of trustworthiness: acoustic-based modulation of perceived voice personality. PLoS One 14:e0211282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211282

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., and McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games Econ. Behav. 10, 122–142. doi: 10.1006/game.1995.1027

Brion, S., Lount, R. B. Jr., and Doyle, S. P. (2015). Knowing if you are trusted. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6, 823–830. doi: 10.1177/1948550615590200

Bryant, D., Borenstein, J., and Howard, A. (2020). Why should we gender? The effect of robot gendering and occupational stereotypes on human trust and perceived competency. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Cambridge, United Kingdom (pp. 13–21).

Cambre, J., and Kulkarni, C. (2019). One voice fits All? Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 3, 1–19. doi: 10.1145/3359325

Cascio Rizzo, G. L., and Berger, J. A. (2023). The power of speaking slower. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4580994

Castelfranchi, C., and Falcone, R. (2010). Trust theory: A socio-cognitive and computational model. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Chan, M. P., and Liberman, M. (2021). An acoustic analysis of vocal effort and speaking style 45. Seattle, Washington: AIP Publishing.

Clark, L., Doyle, P., Garaialde, D., Gilmartin, E., Schlögl, S., Edlund, J., et al. (2019). The state of speech in HCI: trends, themes and challenges. Interact. Comput. 31, 349–371. doi: 10.1093/iwc/iwz016

Da Silva, P. T., Master, S., Andreoni, S., Pontes, P., and Ramos, L. R. (2011). Acoustic and long-term average spectrum measures to detect vocal aging in women. J. Voice 25, 411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.04.002

Dahlbäck, N., Jönsson, A., and Ahrenberg, L. (1993). Wizard of Oz studies: why and how (pp. 193–200).

Dahlbäck, N., Wang, Q., Nass, C., and Alwin, J. (2007). Similarity is more important than expertise: accent effects in speech interfaces (pp. 1553–1556).

Del Popolo Cristaldi, F., Granziol, U., Bariletti, I., and Mento, G. (2022). Doing experimental psychological research from remote: how alerting differently impacts online vs. lab setting. Brain Sci. 12:1061. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12081061

Deng, M., Chen, J., Wu, Y., Ma, S., Li, H., Yang, Z., et al. (2024). Using voice recognition to measure trust during interactions with automated vehicles. Appl. Ergon. 116:104184. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2023.104184

Deutsch, M. (1960). The effect of motivational orientation upon trust and suspicion. Hum. Relat. 13, 123–139. doi: 10.1177/001872676001300202

Elkins, A. C., and Derrick, D. C. (2013). The sound of trust: voice as a measurement of trust during interactions with embodied conversational agents. Group Decis. Negot. 22, 897–913. doi: 10.1007/s10726-012-9339-x

Elkins, A. C., Derrick, D. C., Burgoon, J. K., and Nunamaker, J. F. Jr. (2012). Predicting users' perceived trust in embodied conversational agents using vocal dynamics. Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pp. 579–588. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2012.483

Farrús, M., Hernando, J., and Ejarque, P. (2007). Jitter and shimmer measurements for speaker recognition. International Speech Communication Association (ISCA).

Felippe, A. C., Grillo, M. H., and Grechi, T. H. (2006). Normatização de medidas acústicas para vozes normais. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringol. 72, 659–664. doi: 10.1590/S0034-72992006000500013

Fernandes, J., Teixeira, F., Guedes, V., Junior, A., and Teixeira, J. P. (2018). Harmonic to noise ratio measurement-selection of window and length. Procedia Comput. Sci. 138, 280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.040

Ferrand, C. T. (2002). Harmonics-to-noise ratio. J. Voice 16, 480–487. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00123-6

Freitag, M., and Bauer, P. C. (2016). Personality traits and the propensity to trust friends and strangers. Soc. Sci. J. 53, 467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2015.12.002

Freitag, M., and Traunmüller, R. (2009). Spheres of trust: an empirical analysis of the foundations of particularised and generalised trust. Eur J Polit Res 48, 782–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.00849.x

Frühholz, S., and Schweinberger, S. R. (2021). Nonverbal auditory communication-evidence for integrated neural systems for voice signal production and perception. Prog. Neurobiol. 199:101948. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101948

Gambetta, D. (2000). “Can we trust trust” in Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations, vol. 13. ed. D. Gambetta (Oxford: Blackwell), 213–237.

Gelfand, S. A. (2017). Hearing: An introduction to psychological and physiological acoustics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Germine, L., Nakayama, K., Duchaine, B. C., Chabris, C. F., Chatterjee, G., and Wilmer, J. B. (2012). Is the web as good as the lab? Comparable performance from web and lab in cognitive/perceptual experiments. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 19, 847–857. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0296-9

Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. I., Scheinkman, J. A., and Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. Q. J. Econ. 115, 811–846. doi: 10.1162/003355300554926

Goodman, K. L., and Mayhorn, C. B. (2023). It's not what you say but how you say it: examining the influence of perceived voice assistant gender and pitch on trust and reliance. Appl. Ergon. 106:103864. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103864

Groyecka-Bernard, A., Pisanski, K., Frąckowiak, T., Kobylarek, A., Kupczyk, P., Oleszkiewicz, A., et al. (2022). Do voice-based judgments of socially relevant speaker traits differ across speech types? J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 65, 3674–3694. doi: 10.1044/2022_JSLHR-21-00690

Gussenhoven, C. (2002). Intonation and interpretation. France: Aix-en-Provence: Phonetics and phonology. 47–57. doi: 10.21437/SpeechProsody.2002-7

Hammarberg, B., Fritzell, B., Gaufin, J., Sundberg, J., and Wedin, L. (1980). Perceptual and acoustic correlates of abnormal voice qualities. Acta Otolaryngol. 90, 441–451. doi: 10.3109/00016488009131746

Harrison McKnight, D., and Chervany, N. L. (2001). Trust and distrust definitions: One bite at a time. © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 27–54.

Heffernan, K. (2004). Evidence from HNR that/s/is a social marker of gender. Toronto working papers in Linguistics, 23

Honing, H., and Reips, U.-D. (2008). Web-based versus lab-based studies: A response to Kendall. Emp. Musicol. Rev. 3, 73–77. doi: 10.18061/1811/31943

Jalali-najafabadi, F., Gadepalli, C., Jarchi, D., and Cheetham, B. M. (2021). Acoustic analysis and digital signal processing for the assessment of voice quality. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 70:103018:103018. doi: 10.1016/j.bspc.2021.103018

Jessup, S. A., Schneider, T. R., Alarcon, G. M., Ryan, T. J., and Capiola, A. (2019). The measurement of the propensity to trust technology. Ohio, USA: Springer International Publishing.

Kamiloğlu, R. G., and Sauter, D. A. (2021). “Voice production and perception” in Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Kang, G. S., and Heide, D. A. (1992). Canned speech for tactical voice message systems. Fort Wayne, IN, USA: IEEE, 47–56.

Kaur, N., and Singh, P. (2023). Conventional and contemporary approaches used in text to speech synthesis: a review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 5837–5880. doi: 10.1007/s10462-022-10315-0

Kim, H. H.-S. (2018). Particularized trust, generalized trust, and immigrant self-rated health: cross-national analysis of world values survey. Public Health 158, 93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.01.039

Kim, J., Gonzalez-Pumariega, G., Park, S., and Fussell, S. R. (2023). Urgency builds trust: a voice agent's emotional expression in an emergency (pp. 343–347).

Klofstad, C. A., Anderson, R. C., and Peters, S. (2012). Sounds like a winner: voice pitch influences perception of leadership capacity in both men and women. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279, 2698–2704. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0311

Knack, S., and Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 112, 1251–1288. doi: 10.1162/003355300555475

Kreiman, J., and Sidtis, D. (2011). Foundations of voice studies: An interdisciplinary approach to voice production and perception. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Large, D. R., Harrington, K., Burnett, G., Luton, J., Thomas, P., and Bennett, P. (2019). To please in a pod: employing an anthropomorphic agent-interlocutor to enhance trust and user experience in an autonomous, self-driving vehicle (pp. 49–59).

Latinus, M., and Belin, P. (2011). Human voice perception. Curr. Biol. 21, R143–R145. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.033

Lau, D. C., Lam, L. W., and Wen, S. S. (2014). Examining the effects of feeling trusted by supervisors in the workplace: a self-evaluative perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 112–127. doi: 10.1002/job.1861

Lavan, N. (2023). The time course of person perception from voices: a behavioral study. Psychol. Sci. 34, 771–783. doi: 10.1177/09567976231161565

Lavan, N., Burton, A. M., Scott, S. K., and McGettigan, C. (2019). Flexible voices: identity perception from variable vocal signals. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 26, 90–102. doi: 10.3758/s13423-018-1497-7

Lee, J.-E. R., and Nass, C. I. (2010). Trust and technology in a ubiquitous modern environment: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Leung, Y., Oates, J., and Chan, S. P. (2018). Voice, articulation, and prosody contribute to listener perceptions of speaker gender: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 61, 266–297. doi: 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-S-17-0067

Lieberman, P., Laitman, J. T., Reidenberg, J. S., and Gannon, P. J. (1992). The anatomy, physiology, acoustics and perception of speech: essential elements in analysis of the evolution of human speech. J. Hum. Evol. 23, 447–467. doi: 10.1016/0047-2484(92)90046-C

Lim, M. Y., Lopes, J. D., Robb, D. A., Wilson, B. W., Moujahid, M., De Pellegrin, E., et al. (2022). We are all individuals: the role of robot personality and human traits in trustworthy interaction, 2022 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 538–545. doi: 10.1109/RO-MAN53752.2022.9900772

Linville, S. E. (2002). Source characteristics of aged voice assessed from long-term average spectra. J. Voice 16, 472–479. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00122-4

Löfqvist, A. (1986). The long-time-average spectrum as a tool in voice research. J. Phon. 14, 471–475. doi: 10.1016/S0095-4470(19)30692-8

Mahendru, H. C. (2014). Quick review of human speech production mechanism. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 9, 48–54.

Mahrholz, G., Belin, P., and McAleer, P. (2018). Judgements of a speaker's personality are correlated across differing content and stimulus type. PLoS One 13:e0204991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204991

Maltezou-Papastylianou, C., Russo, R., Wallace, D., Harmsworth, C., and Paulmann, S. (2022). Different stages of emotional prosody processing in healthy ageing-evidence from behavioural responses, ERPs, tDCS, and tRNS. PLoS One 17:e0270934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270934

Maxim, A., Zalake, M., and Lok, B. (2023). The impact of virtual human vocal personality on establishing rapport: a study on promoting mental wellness through extroversion and vocalics (pp. 1–8).

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 709–734. doi: 10.2307/258792

McAleer, P., Todorov, A., and Belin, P. (2014). How do you say 'hello'? Personality impressions from brief novel voices. PLoS One 9:e90779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090779

Mileva, M., Tompkinson, J., Watt, D., and Burton, A. M. (2018). Audiovisual integration in social evaluation. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 44, 128–138. doi: 10.1037/xhp0000439

Mileva, M., Tompkinson, J., Watt, D., and Burton, A. M. (2020). The role of face and voice cues in predicting the outcome of student representative elections. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 617–625. doi: 10.1177/0146167219867965

Mori, M., MacDorman, K. F., and Kageki, N. (2012). The uncanny valley [from the field]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 19, 98–100. doi: 10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811

Muralidharan, L., de Visser, E. J., and Parasuraman, R. (2014). The effects of pitch contour and flanging on trust in speaking cognitive agents – CHI '14 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems, 2167–2172. doi: 10.1145/2559206.2581231

Naef, M., and Schupp, J. (2009). Measuring trust: Experiments and surveys in contrast and combination, doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1367375

Nass, C. I., and Brave, S. (2005). Wired for speech: How voice activates and advances the human-computer relationship. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nass, C., and Lee, K. M. (2000). Does computer-generated speech manifest personality? An experimental test of similarity-attraction (pp. 329–336).

O'Connor, J. J., and Barclay, P. (2018). High voice pitch mitigates the aversiveness of antisocial cues in men's speech. Br. J. Psychol. 109, 812–829. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12310

Ohala, J. J. (1983). Cross-language use of pitch: an ethological view. Phonetica 40, 1–18. doi: 10.1159/000261678

Ohala, J. J. (1995). The frequency code underlies the sound-symbolic use of voice pitch. Sound Symbolism. 26, 325–347. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511751806.022

Oleszkiewicz, A., Pisanski, K., Lachowicz-Tabaczek, K., and Sorokowska, A. (2017). Voice-based assessments of trustworthiness, competence, and warmth in blind and sighted adults. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24, 856–862. doi: 10.3758/s13423-016-1146-y

Ostrom, E., and Walker, J. (2003). Trust and reciprocity: Interdisciplinary lessons for experimental research. New York, USA: Russell Sage Foundation.

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., and Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan–a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021a). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88:105906:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021b). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160

Ponsot, E., Burred, J. J., Belin, P., and Aucouturier, J.-J. (2018). Cracking the social code of speech prosody using reverse correlation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 3972–3977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716090115

Puts, D. A., Hodges, C. R., Cárdenas, R. A., and Gaulin, S. J. (2007). Men's voices as dominance signals: vocal fundamental and formant frequencies influence dominance attributions among men. Evol. Hum. Behav. 28, 340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.05.002

Razin, Y. S., and Feigh, K. M. (2023). Converging measures and an emergent model: a meta-analysis of human-automation trust questionnaires. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2303.13799.

Reetz, H., and Jongman, A. (2020). Phonetics: Transcription, production, acoustics, and perception. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Rehman, M. U., Shafique, A., Jamal, S. S., Gheraibia, Y., and Usman, A. B. (2024). Voice disorder detection using machine learning algorithms: an application in speech and language pathology. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133:108047:108047. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108047

Riek, L. D. (2012). Wizard of Oz studies in HRI: a systematic review and new reporting guidelines. J. Hum.-Robot Interact. 1, 119–136. doi: 10.5898/JHRI.1.1.Riek

Riener, A., Jeon, M., and Alvarez, I. (2022). User experience design in the era of automated driving. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Rodero, E., Mas, L., and Blanco, M. (2014). The influence of prosody on politicians' credibility. J. Appl. Linguist. Prof. Pract. 11:89. doi: 10.1558/japl.32411

Rojas, S., Kefalianos, E., and Vogel, A. (2020). How does our voice change as we age? A systematic review and meta-analysis of acoustic and perceptual voice data from healthy adults over 50 years of age. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 63, 533–551. doi: 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00099

Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J. Pers. 35, 651–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01454.x

Schilke, O., Reimann, M., and Cook, K. S. (2021). Trust in social relations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 47, 239–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-082120-082850

Schirmer, A., Chiu, M. H., Lo, C., Feng, Y.-J., and Penney, T. B. (2020). Angry, old, male – and trustworthy? How expressive and person voice characteristics shape listener trust. PLoS One 15:e0232431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232431

Schweinberger, S. R., Kawahara, H., Simpson, A. P., Skuk, V. G., and Zäske, R. (2014). Speaker perception. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 5, 15–25. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1261

Seaborn, K., Miyake, N. P., Pennefather, P., and Otake-Matsuura, M. (2022). Voice in human–agent interaction. Comput. Surv. 54, 1–43. doi: 10.1145/3386867

Shen, Z., Elibol, A., and Chong, N. Y. (2020). Understanding nonverbal communication cues of human personality traits in human-robot interaction. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 7, 1465–1477. doi: 10.1109/JAS.2020.1003201

Smith, S. S. (2010). Race and trust. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 36, 453–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102526

Smith, S. M., and Shaffer, D. R. (1995). Speed of speech and persuasion: evidence for multiple effects. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 1051–1060. doi: 10.1177/01461672952110006

Soroka, S., Helliwell, J. F., and Johnston, R. (2003). “Measuring and modelling trust” in Diversity, social capital and the welfare state. Eds. Fiona Kay and Richard Johnston (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press), 279–303.

Stewart, M. A., and Ryan, E. B. (1982). Attitudes toward younger and older adult speakers: effects of varying speech rates. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 1, 91–109. doi: 10.1177/0261927X8200100201

Sundberg, J., Patel, S., Bjorkner, E., and Scherer, K. R. (2011). Interdependencies among voice source parameters in emotional speech. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2, 162–174. doi: 10.1109/T-AFFC.2011.14

Ter Kuile, H., Kluwer, E. S., Finkenauer, C., and Van der Lippe, T. (2017). Predicting adaptation to parenthood: the role of responsiveness, gratitude, and trust. Pers. Relat. 24, 663–682. doi: 10.1111/pere.12202

Tolmeijer, S., Zierau, N., Janson, A., Wahdatehagh, J. S., Leimeister, J. M., and Bernstein, A. (2021). Female by default? – Exploring the effect of voice assistant gender and pitch on trait and trust attribution – extended abstracts of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. doi: 10.1145/3411763.3451623

Torre, I., Goslin, J., and White, L. (2020). If your device could smile: people trust happy-sounding artificial agents more. Comput. Hum. Behav. 105:106215. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.106215

Torre, I., White, L., and Goslin, J. (2016). Behavioural mediation of prosodic cues to implicit judgements of trustworthiness. Speech Prosody 2016.

Tsantani, M. S., Belin, P., Paterson, H. M., and McAleer, P. (2016). Low vocal pitch preference drives first impressions irrespective of context in male voices but not in female voices. Perception 45, 946–963. doi: 10.1177/0301006616643675

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, W. K. (2000). A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Rev. Educ. Res. 70, 547–593. doi: 10.3102/00346543070004547

Uittenhove, K., Jeanneret, S., and Vergauwe, E. (2023). From lab-testing to web-testing in cognitive research: who you test is more important than how you test. J Cogn. 6:13. doi: 10.5334/joc.259

Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The moral foundations of trust. Social Science Electronic Publishing presents Social Science Research Network 824504, doi: 10.2139/ssrn.824504

Weinschenk, S., and Barker, D. T. (2000). Designing effective speech interfaces. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Weinstein, N., Zougkou, K., and Paulmann, S. (2018). You ‘have’ to hear this: using tone of voice to motivate others. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 44:898. doi: 10.1037/xhp0000502

Yamagishi, T. (2003). Cross-societal experimentation on trust: A comparison of the United States and Japan. In E. Ostrom and J. Walker (Eds.), Trust and reciprocity: Interdisciplinary lessons from experimental research. Russell Sage Foundation. 352–370.

Yamagishi, T., and Yamagishi, M. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motiv. Emot. 18, 129–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02249397

Yokoyama, H., and Daibo, I. (2012). Effects of gaze and speech rate on receivers' evaluations of persuasive speech. Psychol. Rep. 110, 663–676. doi: 10.2466/07.11.21.28.PR0.110.2.663-676

Keywords: trust, speech acoustics, trustworthy voice, human-robot interaction, voice assistants, intelligent agents

Citation: Maltezou-Papastylianou C, Scherer R and Paulmann S (2025) How do voice acoustics affect the perceived trustworthiness of a speaker? A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 16:1495456. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1495456

Received: 12 September 2024; Accepted: 10 January 2025;

Published: 10 March 2025.

Edited by:

Simone Di Plinio, University of Studies G. d’Annunzio Chieti and Pescara, ItalyReviewed by:

Xunbing Shen, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Maltezou-Papastylianou, Scherer and Paulmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Constantina Maltezou-Papastylianou, Y20xOTA2NkBlc3NleC5hYy51aw==

†ORCID Constantina Maltezou-Papastylianou, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9443-4226

Reinhold Scherer, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3407-9709

Silke Paulmann, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4148-3806

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.