95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 02 April 2025

Sec. Health Psychology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1462072

This article is part of the Research Topic Medical Cybernics View all 7 articles

Background: The medical effectiveness of Cybernics Treatment with the Wearable Cyborg HAL (Hybrid Assistive Limb) has been verified, and its treatment method has started to be used in many countries around the world. However, the focus of medical evaluations has predominantly been on simple measurement evaluation of physical function, while Patient Reported Outcome (PRO), which encompass various evaluation axes of patients, remain largely unexplored. The mental/psychological field has the potential to develop cutting-edge fields targeting individuals. As the social implementation of HAL progresses, it is important to capture how the physical intervention by HAL affects not only the physical function but also the mental state and social activities of individual users. This approach will help us understand the various aspects of the effects of Cybernics Treatment using HAL.

Objective: In order to elicit deeper narratives of HAL users, this study aims to capture how HAL users with limited physical functionality have changed physically, mentally and socially due to using HAL, through a narrative analysis utilizing counseling methods. Based on the results, the significance of using HAL will also be discussed.

Methods: We analyzed the narratives of nine HAL users who received the services of “Neuro HALFIT.” During the interview survey, we also visualized the narratives using mathematical engineering methods (cluster analysis, dendrogram) based on the similarity distance matrix between the association items and elicited them by deepening the narratives through counseling methods and captured the state of change in the physical, mental, and social aspects of the subjects.

Results: The results suggested that “Neuro HALFIT” improved physical function and provided mental and social improvements. These three aspects influenced and circulated each other, advancing toward improvement and enhancement, and the “Mutual feedback structure model in physical, mental, and social aspects of patients” was proposed and presented. Based on the above analysis, it was considered that the greatest significance of using HAL was to help many people with fixed disabilities or those who were considered to have no treatment to turn the process of this model without losing hope and to participate in society with a sense of fulfillment in their lives.

Cybernics Treatment with Wearable Cyborg HAL (Figure 1) was created as a new treatment method for patients with diseases of the body and nervous system (intractable neuromuscular diseases for which no treatment had previously been available; Sankai and Sakurai, 2018; Nakajima et al., 2021), and after clinical evaluation and clinical trials, HAL is now being used in 20 countries around the world. In Germany, Cybernics Treatment was the world's first treatment for spinal cord injury to be covered by public workers' compensation insurance (2013), and in Japan, it has been covered by public medical insurance for 8 progressive intractable neuromuscular diseases (2016) after randomized controlled crossover trial (NCY-3001 trial; Nakajima et al., 2021) and 10 diseases (2023) with the addition of 2 more diseases, including intractable spastic paraplegia (CYBERDYNE Inc., 2025).

When evaluating the efficacy of the HAL treatments, physical function is currently the primary endpoint (clinical trials for neuromuscular diseases), which is a traditional endpoint. Distance for 2 min (or 6 min), 10 m walking speed, etc. are measured and statistically analyzed. In this way, the statistical properties of the effect of a treatment on a patient population can be clarified. However, individual patients have diverse backgrounds, and there is a limit to capturing diverse patient information from the perspective of medical statistics for a group. In recent years, in addition to conventional statistical and average medicine for populations, precision medicine that takes genetic and other characteristics into account has emerged, and it is necessary to connect this to individualized medicine and health from the diverse perspectives of individual patients in the future. The mental/psychological field including mental health has the potential to develop as a cutting-edge pioneering area for the individual. In recent years, there has been an increasing emphasis on the important role of patient motivation in determining outcomes in traditional rehabilitation and new medical technologies (Maclean et al., 2000; Kitajima et al., 2014a), as well as the perspective of looking at single person from multiple perspectives (Kitajima et al., 2014b). In particular, Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) studies on the patient side have become increasingly important in recent years, and the U.S. FDA issued guidance in 2009 indicating PRO measurement (US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, 2009).

Functional improvement therapy with HAL, which has emerged as one of the most advanced scientific technologies mentioned above, focuses on improving physical function (walking function). Through the efforts to promote functional improvement with HAL to date, interestingly, we have noticed a mental change in the users. As social implementation of HAL progresses worldwide, it is very important to understand how interventions on the user/patient's physical body affect their mental health on an individual level, and furthermore, social aspects should also be taken into consideration.

Therefore, we have begun the challenge of proposing a method and applying it to actual situations to capture the possibility that physical interventions using HAL for individual users will improve their “physical functions,” which in turn will lead to improvements in their “mental health,” and then to improvements in their “social activities” (Ikemoto et al., 2022). This is different from the conventional evaluation based on simple walking distance and time alone to capture changes in physical condition as patient information.

There is an increasing number of reports on physical changes in HAL users from the viewpoint of providers of treatment programs. However, very few PRO studies have focused on the psychological aspects of HAL users. One study used FAC (Functional Ambulatory Categories) as the primary endpoint, with PRO evaluation SF-8 (Health-related Quality of Life) and POMS (Profile of Mood States) as secondary endpoints (Watanabe et al., 2016). Another study has investigated and analyzed the PROs of HAL users quantitatively and qualitatively (Ikemoto et al., 2022). But those are very few in number. We believe that clarifying how HAL users experience HAL and how they feel its effects will have important significance from the perspective of disseminating information toward the realization of a “Techno Peer Support” society where technology like HAL and people coexist and support each other (CYBERDYNE Inc., 2024).

Narrative analysis is a method of revealing the inner world of an individual generated through the subject's narratives. It is sometimes pointed out that narratives are only one case study because they are individual narratives, but when focusing on individual patients, it is possible to capture information that cannot be captured by medical statistical methods targeting groups. This information can be used to provide better treatment and mental support for patients with a variety of problems.

In this study, narrative analysis will be conducted by psychological professional utilizing counseling methods with the aid of PAC analysis (Analysis of Personal Attitude Construct; Naito, 2024) for HAL users. Narratives will be elicited by looking at the visualized dendrogram and the process of cluster cohesion will also be textualized, and the counseling method will be used to generate deeper narratives and devise a way to recall response shifts (Ito, 2008) due to awareness in real time. These features will be used to construct a method that allows psychological professionals and individual HAL users to share information that has been analyzed and organized to understand what is happening during the ongoing period of treatment intervention and daily life.

In addition, by investigating, analyzing, and visualizing the narratives of HAL users over the medium to long term from the viewpoint of time using the above approach, the purpose of this study is to clarify how HAL users with limited physical functions have physically changed, and what kind of mental and social changes have occurred as a result, as intervention effect of HAL, and to consider the significance of using HAL through these.

Medical HAL is currently used in the medical field for “Cybernics Treatment” to improve the functions of the cranial nerve and muscle systems. By going through a program using HAL, an interactive BioFeedback (iBF) loop [brain → spinal cord → motor neurons/motor nerves → muscles → HAL] and [HAL → proprioceptors → sensory nerves → spinal cord → brain] is formed between the body and HAL (Standring, 2016). In other words, the musculoskeletal system is moved by HAL operating in synchrony with the wearer's motion intention. During this process, proprioceptors, including muscle spindles among others, are activated through muscle extension. In voluntary movements assisted by HAL, with almost no muscle load, the signal loop of the mechanism of action is continuously engaged, thereby promoting functional recovery and regeneration (Sankai and Sakurai, 2017; Saotome et al., 2022).

“Neuro HALFIT” is a neuromuscular functional improvement program using non-medical HAL systems, including the lower limb type [dual-leg (Ezaki et al., 2021; Kadone et al., 2020), single-leg (Watanabe et al., 2020)], single-joint type (Shimizu et al., 2019), and lumbar type (Yasunaga et al., 2021; Kato et al., 2022). It is delivered by specialized staff, such as physical therapists, occupational therapists, and certified health exercise instructors, who customize the program to meet individual needs (ROBOCARE CENTER Group, Neuro HALFIT, 2024). This program serves individuals with cerebrovascular disorders, spinal cord injuries, and neuromuscular diseases, for which no fundamental treatment exists, as well as those seeking to prevent frailty. Each session lasts either 70 min (16,600 JPY) or 90 min (17,600 JPY). Users have the option to combine multiple HAL types within each session. As of July 2024, this service is available at 18 locations across Japan, including the Tsukuba Robocare Center, operated by CYBERDYNE (ROBOCARE CENTER Group, Robocare Center Locations and Fees, 2024). These Robocare Centers do not offer the standard rehabilitation services typically available in hospitals. Instead, they focus exclusively on HAL-based neuromuscular functional improvement programs tailored for individuals in the maintenance phase of rehabilitation.

The authors, in consultation with HALFIT's specialized staff, identified potential research participants. Participants were selected from HAL users enrolled in the “Neuro HALFIT” program at the Tsukuba Robocare Center based on the following inclusion criteria. We decided to include those who were able to cooperate with and physically endure a lengthy interview survey, those who communicate well, and those who had been continuing the “Neuro HALFIT” program for several months or longer, thus ensuring to exclude those who had not yet experienced any changes because they had only been coming for a short period of time. The nine participants who were selected were diverse in age, gender, diagnosis, physical condition, length of time since the onset of their illness, and duration of HAL use. Consent was obtained from all nine participants, and all nine were included without exclusion to avoid bias. In psychological research where narrative interviews are conducted, nine participants are considered sufficient.

The survey period was from October to December 2015 (2 cases) and from September 2020 to January 2021 (7 cases). When participants came to the Tsukuba Robocare Center, we conducted the survey and asked them to cooperate for research in two sessions (Sessions 1 and 2).

Before the survey, we provided the participants with a document that stated: “The purpose and content of the survey would be used for research purposes, the conversation will be recorded, the participation is voluntary, no disadvantages would result from participation or non-participation, data would be anonymized, data would be stored for a certain period until it is disposed of, the survey could be discontinued even in the process if the participants felt burdened, and if the participants have difficulty writing or reading the researcher will provide necessary support.” Since ethical review is required at the site where the research is conducted, this study underwent research ethics review by CYBERDYNE Inc., which manages and operates the Tsukuba Robocare Center (however, the ethics review committee member of the University of Tsukuba, the joint research partner, serves as the ethics review committee chairman). This study conforms to the guidelines of the Japanese Psychological Association, was approved by CYBERDYNE's internal Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 150003), and is being conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki.

The interviews were conducted by one of the authors, a clinical psychologist involved in the study. By carefully listening to each individual's narrative using counseling techniques, the researcher was able to deeply explore the individual's inner world. An interview survey was conducted with the aid of the PAC analysis (Analysis of Personal Attitude Construct) method (Naito, 2024). This method allows the researcher to obtain the overall vital variables and factors recalled from the informants' long-term memory and interpret the data phenomenologically through conversation to learn about an individual's inner world.

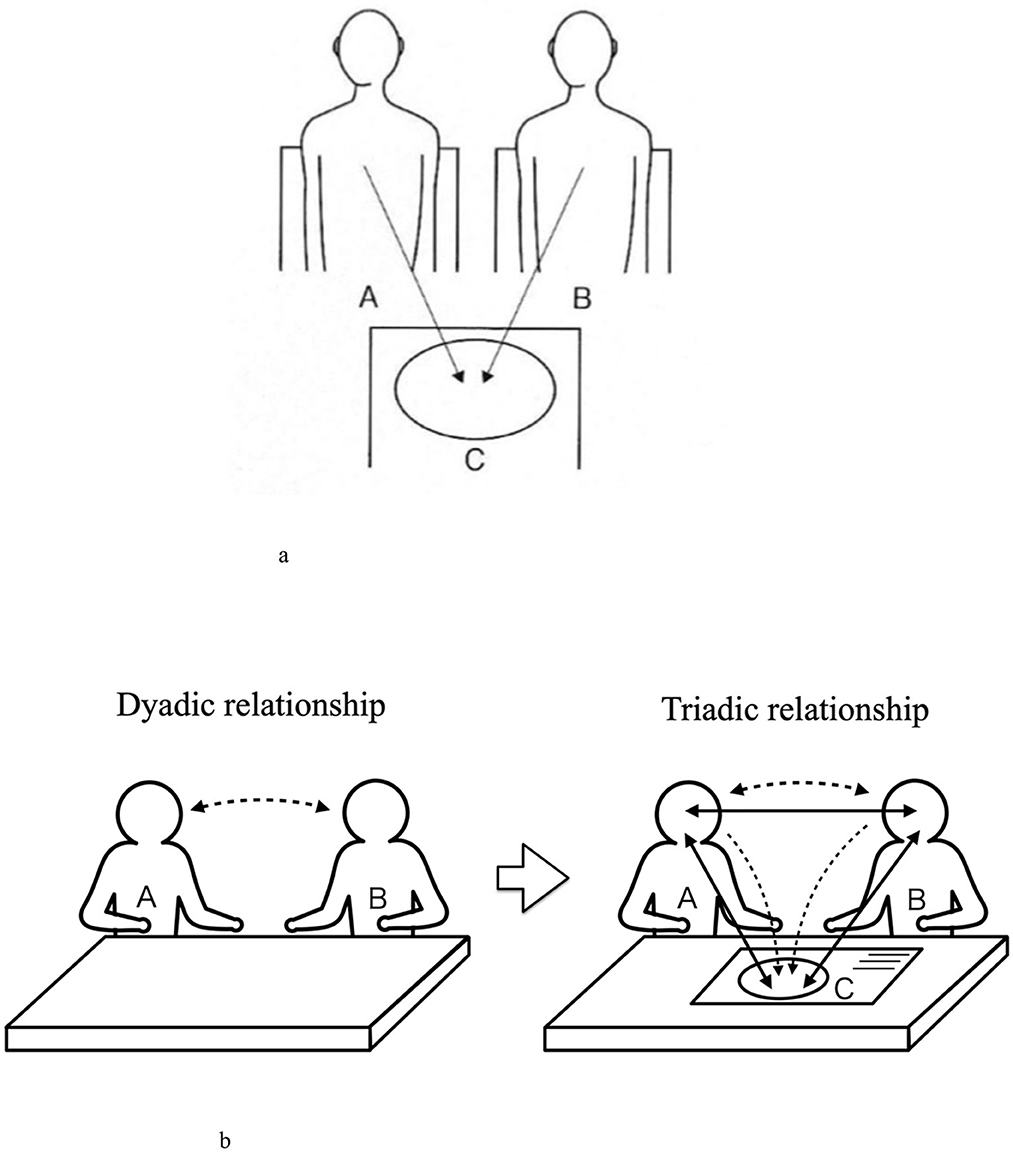

Narrative refers to “the act of speaking through words and what was spoken,” whereas visual narrative is conversing through visual images or visual images and words. While face-to-face dialogue could sometimes be confronting, in a visually mediated triadic relationship, two persons are next to each other and see the same thing. The latter is more likely to create a sympathetic and empathic atmosphere (Yamada, 2019). A triadic relationship is a relational theory emphasizing the mediating function [mediator or medium] that connects people. Yamada describes three models of Triadic relationships: Model I (communication in line relationships; Figure 2a), Model II (communication in matchmaker relationships), and Model III (communication in watchful waiting relationships; Yamada, 2021). This paper shows a “Visual narrative that makes up the Triadic relationship” (Figure 2b) to assist in understanding.

Figure 2. (a) Triadic relationships Model I. (b) Visual narrative that makes up Triadic relationship.

Since seven of the nine research participants in this study had difficulty writing due to disabilities related to their diseases and requested that the researcher write on their behalf, the participant and the researcher were positioned side by side. The same position was also chosen for the two who did not request to write instead of them. This corresponds to the “Triadic Relationship Model I,” which co-generates the narratives.

This study was conducted with the aid of the PAC analysis method (Naito, 2024). The researcher proceeded with the interview in a counseling approach, such as sympathizing with the narratives told by the participants. At times, the researcher promoted the narrative or asked questions to deepen the conversation, but the researcher ensured that such responses aligned with the flow of the narrative. The study took an original approach by conducting the interviews in a counseling style while taking the Triadic Relationship Model I position.

The interview questions were: “What physical and mental changes have you experienced through using HAL? Did those changes cause any difference in your behaviors or lifestyle?”. The phrase “social changes” is difficult to understand, so the researcher replaced it with “behavioral and lifestyle changes.” During the interview survey, the participants kept a printed copy of the question on hand so they could check it at any time.

The following (1) to (6) are tasks to be performed proactively by the participants. The researcher will guide them through the process, but will not guide them in the content of their responses.

<Interview Survey: Session 1>

1) Writing out association items: After hearing the question, the participant wrote down any answers that came into his/her mind one by one on a card as “association items.” This process continued until the participant no longer found something to write about the question. If the participant had difficulty writing, the researcher provided assistance by transcribing participants' responses on his/her behalf.

2) Sort association items by importance: The participant looked at all the association items written down and arranged the cards in order from the most important (smaller number) to the least important (larger number).

3) Similarity ratings between association items and creation of similarity distance matrices: The participant was asked to judge how similar or different association items are from other association items based on their intuitive images. The researcher asked participants to answer this on a 7-point scale: very close = 1, reasonably close = 2, somewhat close = 3, neither close nor far = 4, somewhat far = 5, relatively far = 6, and very far = 7. The researcher then created a similarity distance matrix table based on those numbers.

4) Generating a dendrogram by cluster analysis: The researcher performed a cluster analysis of the similarity distance matrix using the Ward method with statistical software (SPSS Ver25) and generated a dendrogram (tree diagram).

<Interview Survey: Session 2>

5) Interviews by clusters (collection of narratives) and naming of clusters: The researcher, together with the participant, examines the calculated dendrogram, a tree diagram that visually represents the relationships between association items based on their similarity distances. In this structure, association items that are close in distance are grouped into the same cluster, clusters that are close to each other are merged into larger clusters, and ultimately, all items are consolidated into a single large cluster. While reviewing the dendrogram, the researcher interviews the participant cluster by cluster regarding the content of the association items. To elicit deep narratives, the researcher responds using counseling techniques, actively engaging in the conversation to encourage reflection and insight. The participant conceptualizes the meaning of each cluster and assigns a cluster name accordingly. As smaller clusters merge into larger clusters, the participant also names these newly formed larger clusters. This iterative process continues until all clusters are fully integrated into a single, overarching cluster. After the clustering process is complete, the researcher conducts supplementary questioning to further explore and collect even deeper narratives.

6) Images of association items: For each association item, the researcher asked the participant whether it sparks positive (+) images, negative (–) images, or somewhere in between (+/–), and the researcher or the participant wrote down those evaluations on each card.

<Converting narratives into texts>

7) Converting narratives into texts by the researcher: The researcher converted the participant's narratives obtained from the interview into text, following the order of the narratives. In this step, the researcher also recorded the process of turning each item into clusters and deepening the narratives. The researcher then turned both processes into texts.

<Grouping of all association items>

8) Grouping of all association items by the researcher: All association items obtained from the participant were grouped by the researcher into three perspectives: physical, mental and social. A list of association items and a classification table for each of the three perspectives were created.

The participants were nine HAL users visiting Tsukuba Robocare Center. “Age,” “Gender,” “Diagnosis,” “FAC (Functional Ambulation Categories),” “WISCI II (Walking index for spinal cord injury II),” “Period after onset,” and “HAL usage period” are shown in Table 1.

This study used counseling approaches and mathematical engineering methods for narrative analysis that involves a large number of descriptions, and in the interest of brevity, we decided to describe only one case in detail to illustrate the analysis procedure that was implemented. As described in “Section 1”, a randomized controlled crossover trial that included eight diseases: spinal muscular atrophy, bulbospinal muscular atrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, distal myopathy, inclusion body myositis, congenital myopathy, and muscular dystrophy (Nakajima et al., 2021) was conducted to demonstrate the effects of HAL on the physical function of its users. Since participant G had Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and was the only participant with a neuromuscular disease included in the HAL NCY-3001 RCT, we thought it would be meaningful to report in detail how she was changing with the use of the HAL, in terms of research from a different perspective than the RCT. As such, we describe the details of G's case study.

Participant G is a female participant in her 30s. When she was seven, a doctor gave her a final diagnosis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Her physical disability level in her certificate is grade three in the upper limb and grade five in the lower limb. Twenty-seven years have passed since she first realized her symptoms, and she has been using HAL for 3 years. She is capable of walking without a cane, but 4 years ago, she felt the disease was progressing, as she found it challenging to continue her work that requires tasks in a standing position. When thinking about quitting her job, she learned about HAL and visited the Robocare Center for the first time. She conducts gait training with HAL Lower Limb Type, arm, hand, and ankle movement training using HAL Single Joint Type to continue her work. She visits the center once every 1 to 2 weeks.

Participant G came up with 27 association items. In the interview conducted while the researcher and Participant G were looking together at the dendrogram generated through cluster analysis, the researcher asked Participant G to talk about the contents of each cluster. The researcher then requested that Participant G consider the similarities of items in the same cluster and write a name that suited that cluster. The researcher numbered those clusters from the top to bottom by CL1-CL7. The researcher carefully listened to the narratives and asked questions as appropriate. The_researcher and Participant G repeated the process as the researcher connected the clusters with Participant G. After naming a word to summarize the one cluster that the_researcher and Participant G formed at the end, the researcher asked what Participant G thought about the interview survey.

Figure 3, “Participant G's Dendrogram,” is composed of the “association items,” “order of importance (1–27),” and “image of association items (+/–/±)” overlapped on a dendrogram that was generated. The researcher started the interview sequentially from Cluster 1 to Cluster 7. The narratives generated while linking each cluster are shown in Table 2, “Participant G's Narrative results.” The questions that the researcher asked research participant to elicit deep narratives in a counseling manner are shown in < > in Table 2. These questions show how they were able to collect deep narratives.

The following is a Cluster-by-Cluster Interpretation of the results in Table 2.

Of the 27 association items, Participant G classified two items labeled with negative images into CL1. Hence, this cluster was named “Negative Influence.” However, regarding time and financial burdens, the participants felt it is “drowned out compared to the benefits.” As such, we presume that the participant considers these items as self-investment to achieve her targets.

Participant G's motivation for visiting Robocare Center was a sense of anxiety that she might not be able to continue her job, which involves a lot of standing work. The association item that was ranked to be most important was “No longer feeling anxious,” and the second was “Not having to quit my job.” She stated that her job is not only the foundation of her life but also a reason to live, her identity, and something that keeps her going. It is significant that she was able to avoid the loss of such vital things and that her sense of anxiety was eliminated through the use of HAL, and we anticipate that the event could have a significant impact on Participant G's future life.

Participant G's first experience of “giving up because of disease” was when she had to give up playing the piano, which she had loved in her childhood. After almost 30 years of distancing herself from the piano, her turning point may have been “becoming easier to open my fingers” and “the change in my mind that I don't have to play like others.” Her words, “I loved it after all,” conveyed her great joy at being able to resume playing the piano.

She described in detail how she had been dominated by vague anxiety because she was suffering from an intractable disease. She compared this to how she felt her body temperature. She gradually freed herself from being preoccupied with her disease to a state of mind in which she wanted to do something positively and actively. As she said in her self-insight, “It may be due to my age,” we analyzed that as she has gotten older, she has become better at dealing with disease and has become more flexible in her thinking.

CL5 is the largest cluster with nine association items. She reported heartfelt reports of improvements in gait, trunk, and balance and that she started to enjoy walking more as she improved. We also interpreted it as an endorsement of not having to quit her job from the physical perspective.

Participant G mentioned improvements related to feet and shoes and changes in life, such as going to the gym and using the stairs. Her statement that she was “naturally very active personality, but the disease has restricted me and balanced me” could be interpreted as a positive sense of her life living with the disease, which she shared with laughter. We felt that it was the new frontier of Participant G that she had reached after years of struggle.

We interpreted this as an episode of further adaptation to the world surrounding her.

Participate G mentioned that she has the mentality of her “original self” and “self who has become restricted and withdrawn after being diagnosed with the disease.” But in the end, the whole story was summarized as “Release from my diseased self.” These words may be a voice of joy that Participant G has steadily achieved her primary goal of improving her physical condition after years of suffering, or they may be words of prayer that express her strong desire for an ideal condition even though she knows that the disease is incurable.

Each of the nine participants' interviews lasted ranging from 3.5 to 5.5 h for the two sessions combined. No adverse physical or psychological effects were observed. Table 3, “List of Association Items of Nine Participants,” shows the results categorized by the three aspects (physical, mental, and social). Seven participants reported the most on the “physical” aspect, while two reported the most on the “mental” aspect. None of the participants wrote down the most numbers of “social” aspects. Table 4, “Classification of Association Items by three aspects,” classifies the association items into three aspects. We organized 67 items as “physical,” 56 items as “mental,” and 40 items as “social.” The following three conducted the classification: the researcher and two expert staff members (physical therapist, certified health exercise instructor) of the Tsukuba Robocare Center.

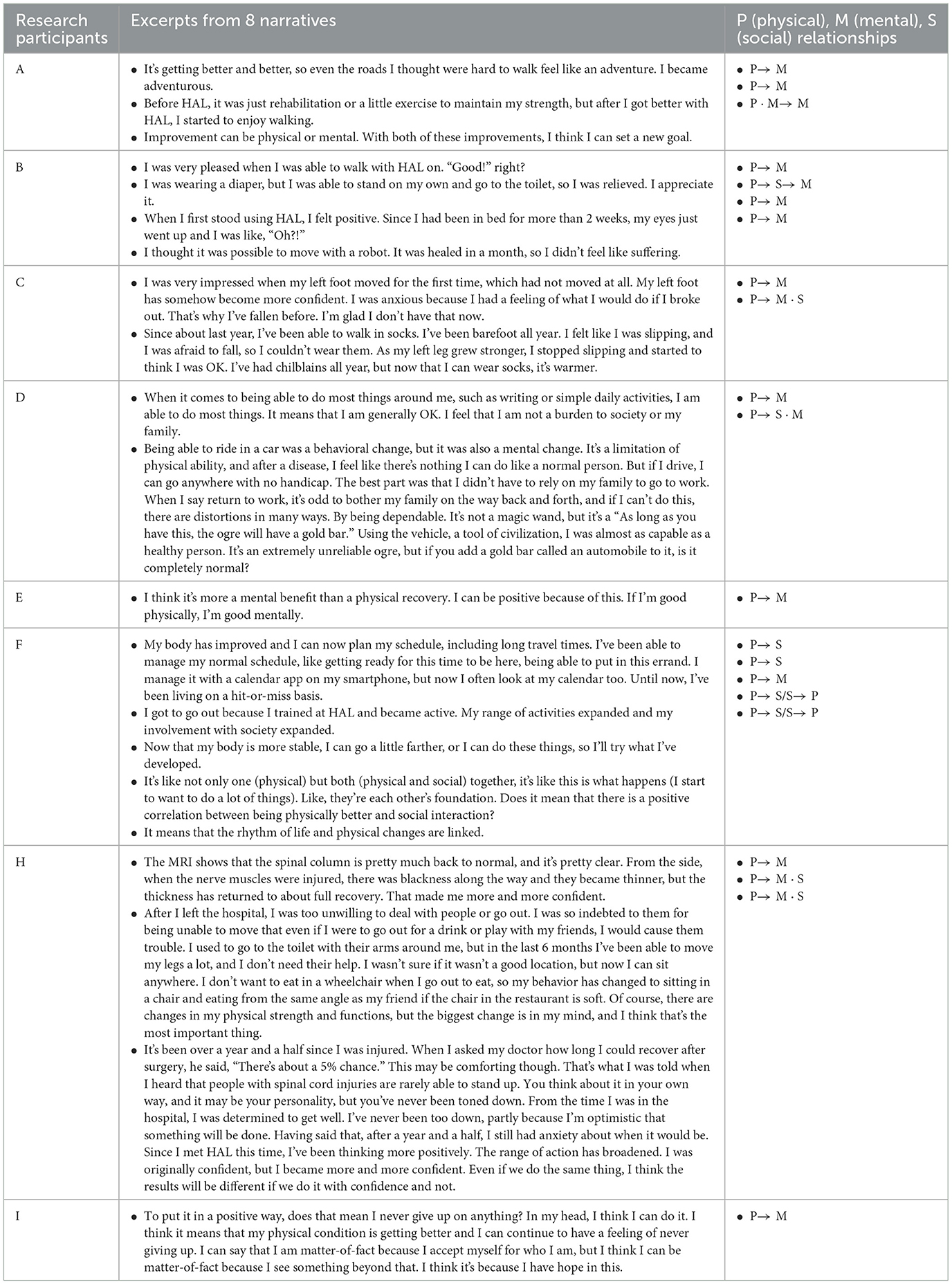

Narrative summaries for each of the eight participants except for G, are shown in Table 5.

Since “Neuro HALFIT” is a program to support functional improvement, HAL users use the service primarily to improve or enhance their physical aspects. All nine individuals, including the seven with disability certificates, as shown in Table 1, reported “improvements in body parts,” such as legs, hands, and trunk, and “improvements in physical abilities,” such as walking, mobility, balance, and sitting. Some also reported improvements in their “overall physical feeling,” such as “feeling more comfortable,” “better endurance,” and “less stiffness.”

Participants also showed improvement in their mental health. The content (of functional improvement) varied from “I am happy/impressed,” “I want to get better,” “I feel more positive,” and “Walking has become more enjoyable.” There were also reports of a solid response to the recovery: “My desire to move has changed to my conviction that I can move (B)” and “There is hope for recovery. Changed into a conviction that I could recover (H).”

In addition, some participants listed more mental improvement than physical improvements in their association item (A, C) or written association item that “The mental effect was greater than the physical recovery (E).” These cases have one thing in common: The participants who felt more mental improvement tended to continue using HAL for a long time. Once they achieve a certain degree of improvement, they work to maintain their physical condition, which seems to be the time they experience mental enrichment (C: “Meeting HAL makes me motivated”/E: “I feel refreshed when I come here”).

In terms of social aspects, various changes (positive changes) can be seen in their lives, such as improvement in ADL (activities of daily living, housework, going out, driving a car) and improvement in QOL (hobbies, return to work, return to school, conversation). To give some examples from reports in this aspect, “(because my trunk has become stronger, my balance has improved, and I have stopped slipping),” I am now able to walk in socks (C), “Resumed playing the piano (G),” and “I started hand-cycling (H).” In addition, there are also cases that led to significant life events, such as returning to school and graduating while using HAL after becoming a wheelchair user due to an accident when the participant was in college (F) and being able to return to work (D).

Reports such as “Using HAL has become a habit in itself, creating a rhythm of life (I)” and “I started to look more closely at my calendar (F)” were common narratives of people who came to the center, as they tend to come in on fixed days and times, which became the center of their entire lives. Others reported that their recovery had helped reduce the burden on their families. Such as, “No more trouble for my family, more pious (D)” and “Healthy and absent husband is nice. My family is liberated (E).”

Tsukuba Robocare Center is located in a large shopping center, and some participants (F, G, I) reported that they enjoy shopping and eating before or after using HAL, which is one of the motivations for continuing “Neuro HALFIT.”

On the other hand, some pointed out that the price to use HAL is high (F, G) and want to come more often if “Neuro HALFIT” is cheaper (E).

Tracing Participant G's narrative with the keywords “give up/don't give up” reveals the following narrative. “Struggling with disease and loneliness, I lived on while giving up many things. I had given up on curing the disease as there was no cure. My body has gradually improved in the 3 years since I started HAL. I did not have to give up my job that I was about to give up. I can once again play the piano that I once gave up. I also gave up marriage, but I am starting to think it is possible as I get more mature according to my age.” We felt that she is now at a turning point where she is changing from “a life of giving up” to “a life of trying as hard as she can without giving up.” We analyzed that these turning points were mainly brought about by “improvement and enhancement in physical, mental, and social aspects” and “becoming more mature as a person.” We will discuss these two points further.

Participant G's disease is a rare hereditary neurological disease, and modern medicine has not found a cure or treatment to slow its progression. However, functional improvement with HAL (Lower Limb Type/Single Joint Type) has resulted in improvement of the legs and hands themselves, stability of the trunk, and physical improvements such as reduced lateral sway, easier walking, and less fatigue. The results showed a wide range of mental changes, from “no longer feel anxious, started to enjoy walking” to “becoming more accepting, more positive, more flexible” to being able to keep “reason to live, identity and the energy keep on going.” Then there were social changes such as “I didn't have to quit my job, I started playing the piano again, I started going to the gym, I started to use stairs, it became easier to go out.”

In Participant G's narrative, there were several places where she plainly stated that mental and social changes (including behavioral and lifestyle changes) occurred after the physical improvement. The following are those extracted comments.

• I had difficulty going outside when moving was difficult, but now I am more outgoing and can think more positively (physical → mental).

• Now that I am better after using HAL, It's almost like I am coming down a little from the peak of my fever. As mentioned in the association item, my feelings have become more flexible. It may be due to my age, but I don't need perfection (physical → mental). It has become easier to accept invitations from friends (physical → mental → social).

• The condition of my legs is improving, and I feel like I should walk instead of drive (physical → mental → social).

• I am starting to enjoy walking and feel a change in walking (physical → mental → social).

• I feel more positive and want to try something, so I started playing the piano again (physical → mental → social).

• My feet were deformed, and there was a difference between my left and right foot, so I had difficulty wearing shoes. The deformity is starting to be removed, and wearing shoes is now easier. Moving and doing something became easier, so I started going to the gym (physical → social).

The comments above suggest that the improvement of the physical aspect triggered a virtuous cycle of “improvement and enhancement” in which the three aspects are interconnected and influence each other, spiraling up to the next step.

In addition, there were changes in her mind, such as “I don't have to play the piano like others,” “I don't have to be perfect,” and “the disease has restricted me to make me balanced,” suggesting that there has been a positive sense of living with the disease while accepting it. These mental changes may be a new frontier brought about by her maturity as a person, as she has become better able to deal with her disease as she has gotten older, and with that, she has acquired a new sense of values to reassess her life in a positive and affirmative sense.

The findings above suggest that the alignment of both “improvement and enhancement in physical, mental, and social aspects” and “maturity as a person” has brought about a change from a “goal-oriented” mentality that aims for an ideal goal to a “process-oriented” mentality.

The narrative, in line with the dendrogram and those about what she had given up in her life, drawn out by questions, vividly represented a part of Participant G's journey so far and revealed the painful feelings that she had not been able to talk about due to her hereditary and rare disease. The interview facilitated a natural form of self-disclosure, as Participant G commented, “This is the first time I have talked about something like this,” and “I'm surprised myself.”

In Participant G's case, we saw a positive “improvement and enhancement cycle,” which was triggered by physical improvement followed by mental and social improvement. In this cycle, the three aspects are interrelated and affect each other to form an upward spiral toward the next step. Similarly to the previous Section (4.2), when examining the other eight participants, we observed a similar trend in the narratives of the other eight participants. We listed the excerpts of this trend in Table 6, “Excerpts of narratives in which the physical, mental, and social aspects are interrelated (8 cases).” These narratives suggest that mental and social changes (including behavioral and life changes) have occurred because of physical improvements caused by HAL.

Table 6. Excerpts of narratives in which the physical, mental, and social aspects are interrelated (8 cases/excluding G).

Narratives such as “Improvement can be physical or mental. I think both improvements lead to the creation of a new goal (A)” “If my body improves, my mind improves (E)” and “Not just one (physical aspect) but both (physical aspect and social aspect) come together to be like this (I want to do various things). Each of them will become a foundation for the other. I suppose it means a positive correlation between physical improvement and social involvement (F),” which tells us plainly that physical, mental, and social aspects will improve and enhance each other rather than develop independently.

Narratives like “I think the mental effect is greater than the physical recovery (E)” and “Of course, there are changes in my physical strength and functions, but I think the biggest change is in my mind, and that's the most important thing (H)” are notable for emphasizing the importance of mental over physical changes.

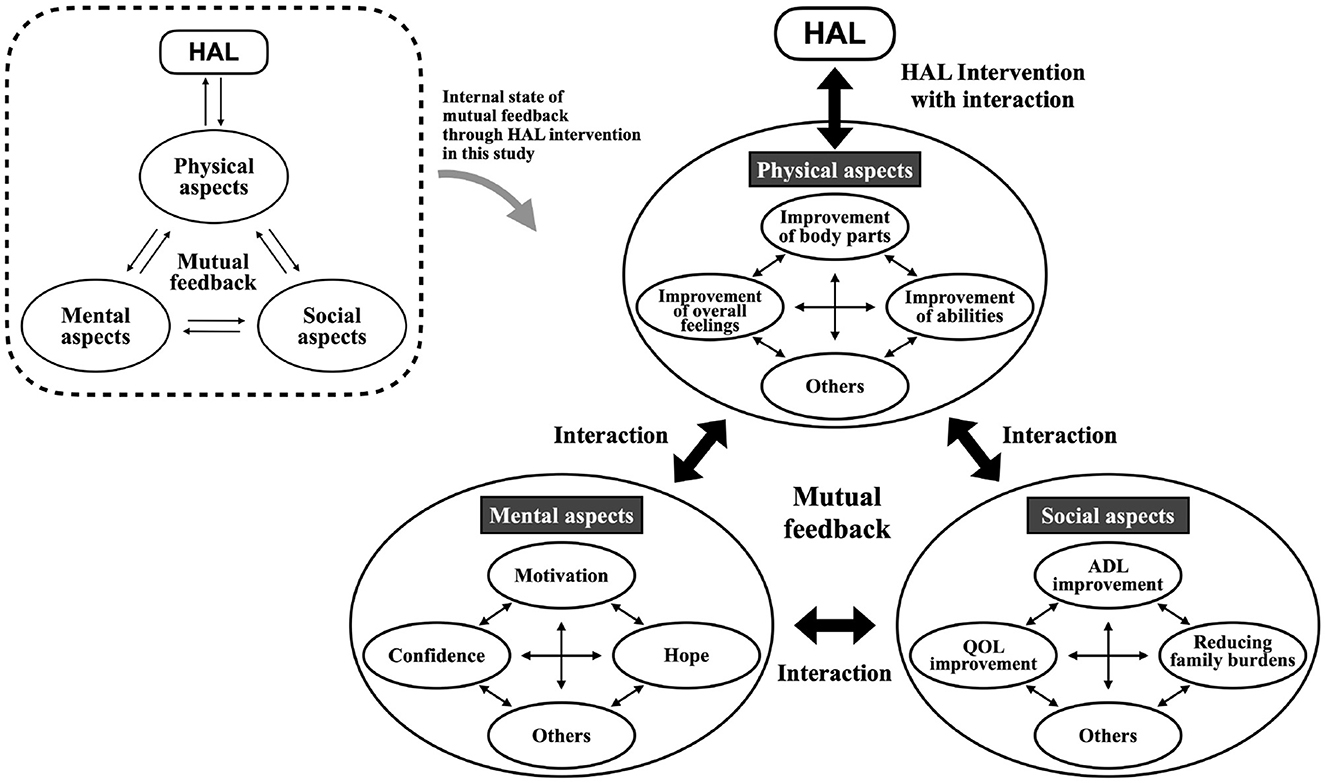

The positive cycle of “improvement and enhancement,” in which the physical, mental, and social aspects are interconnected and influence each other and form an upward spiral toward the next step, was seen in everyone's narratives, including Participant G. This is shown in a conceptual diagram as a “Mutual feedback structural model in physical, mental, and social aspects” using keywords in Table 4 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Mutual feedback structure model in physical, mental, and social aspects through HAL intervention.

HAL users are considered to have achieved the primary purpose of using the service to improve their physical condition to some extent and continue to improve their physical condition. Improvement in physical condition led to mental progress, such as gaining motivation, hope, and self-confidence. In addition, ADL and QOL were improved, and it was shown that life improved and positive behavioral changes occurred. These three aspects are thought to influence each other and circulate mutually, leading to the next step toward improvement and enhancement.

The mutual feedback structure model revealed in this study suggests the universal possibility of cyclical continuous improvement of physical, mental, and social function through the utilization of technology such as HAL that breaks through the commonly accepted limit of improvement from standard-of-care treatment and other means of care. The interactions between the physical improvements and mental and social changes form a virtuous cycle that feeds into itself, promoting even further positive change that is vital to these patients.

The narratives of the participants, which were analyzed and visualized through the interview survey, are not intended to measure the HAL users' impressions at a certain point in time or changes before and after the use of HAL but rather to provide valuable data for understanding how they have changed over time using HAL. It became clear that “Neuro HALFIT,” which was initially intended to improve physical function, also brought about mental and social improvements.

It is challenging to determine the extent to which patients who have been disabled due to accidents or diseases can return to their original physical condition. Many who come to “Neuro HALFIT” have completed regular hospital rehabilitation. They also tend to be those who doctors told that they could not be expected to recover further, diagnosed with neuromuscular diseases for which there is no treatment, or use wheelchairs due to difficulty in walking. The nine participants in this study all fell into one of these categories. It is vital for such people to participate in society in a way that fits their needs by turning the process of the “Mutual feedback structure model” without losing hope while enjoying their daily lives and feeling a sense of purpose. The most critical significance of using HAL is to support this process. Although the narratives of the nine participants are diverse, they all share this point in common.

In this study, during the interview survey, we also visualized the narratives using mathematical engineering methods (cluster analysis, dendrogram) based on the similarity distance matrix between the association items, and elicited them by deepening the narratives through counseling methods and captured the state of change in the physical, mental, and social aspects of the subjects. This proposed a new method, but at the same time, it has the limitation that it requires the level of counseling at the level of a clinical psychologist and that it takes a long time.

Another limitation of this study is that it cannot be said to reflect the reality of all HAL users because it only included those who continued with HAL and did not include those who improved their function with HAL and completed it, or those who discontinued HAL because it was not a good fit, thus causing a selection bias.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by CYBERDYNE Inc. Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

SI: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YS: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

We want to express our deepest gratitude to the nine participants who cooperated in our lengthy interview survey and shared their valuable narratives. We would also like to thank Mr. Yudai Katami of CYBERDYNE and Mr. Hiroki Kimura of CYBERDYNE (RISE Healthcare Group, USA) for their invaluable support in English language editing. This research partially includes the results of Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP), “Expansion of fundamental technologies and development of rules promoting social implementation to expand HCPS Human-Collaborative Robotics” promoted by Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI), Cabinet Office, Government of Japan [Project Management Agency: New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO; Project Code JPNP23024), HCPS: Human-Cyber-Physical Space].

SI is a researcher at CYBERDYNE Inc., a University startup company, the manufacturer of Wearable Cyborg HAL, Ibaraki, Japan. YS is a professor of University of Tsukuba, a founder, a shareholder, and the chief executive officer of CYBERDYNE. YS's COI is managed by University of Tsukuba according to National university rules and guidelines and by board of directors of CYBERDYNE. As relevant financial activities outside the submitted work, the patent royalty is paid to University of Tsukuba from CYBERDYNE, and processed suitably according to National university rules. TS is a researcher of CYBERDYNE. The present study was proposed by the authors.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

CYBERDYNE Inc. (2024). C-Startup Innovation ecosystem to create the Cybernics Industry. Available online at: https://www.cyberdyne.jp/english/company/cej.html (accessed July 7, 2024).

CYBERDYNE Inc. (2025). Treatment of HAM and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia approved for Medical HAL. Available online at: https://www.cyberdyne.jp/english/company/PressReleases_detail.html?id=12909 (accessed February 27, 2025).

Ezaki, S., Kadone, H., Kubota, S., Abe, T., Shimizu, Y., Tan, C. K., et al. (2021). Analysis of gait motion changes by intervention using robot suit hybrid assistive limb (HAL) in myelopathy patients after decompression surgery for ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament. Front. Neurorobot. 15:650118. doi: 10.3389/fnbot.2021.650118

Ikemoto, S., Saito, T., Ogai, Y., and Sankai, Y. (2022). A study on physical and mental changes and behavioral transformation of wearable cyborg HAL users. Life Care J. 13, 13–24.

Ito, N. (2008). Response shift in quality of life research. J. Famil. Tumors. 8, 49–54. doi: 10.18976/jsft.8.2_49

Kadone, H., Kubota, S., Abe, T., Noguchi, H., Miura, K., Koda, M., et al. (2020). Muscular activity modulation during post-operative walking with hybrid assistive limb (HAL) in a patient with thoracic myelopathy due to ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament; a case report. Front. Neurol. 11:102. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00102

Kato, H., Watanabe, H., Koike, A., Wu, L., Hayashi, K., Konno, H., et al. (2022). Effects of cardiac rehabilitation with lumbar-type hybrid assistive limb on muscle strength in patients with chronic heart failure –a randomized controlled trial. Circ. J. 86, 60–67. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-21-0381

Kitajima, Y., Suzuki, A., Harashima, H., and Miyano, S. (2014a). Relationships with quality of life, physical function, and psychological, mental, and social states of stroke patients in a recovery ward. Part III: motivation for rehabilitation. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 29, 1023–1026. doi: 10.1589/rika.29.1023

Kitajima, Y., Suzuki, A., Harashima, H., and Miyano, S. (2014b). Relationships with quality of life, physical function, and psychological, mental, and social states of stroke patients in a recovery ward. Part II: quality of life. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 29, 1017–1022. doi: 10.1589/rika.29.1017

Maclean, N., Pound, P., Wolfe, C., and Rudd, A. (2000). Qualitative analysis of stroke patients' motivation for rehabilitation. BMJ 321, 1051–1054. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7268.1051

Naito, T. (2024). Analysis of personal attitude construct for diagnosing single cases operationally, qualitatively and quantitatively. J. PAC Anal. 1, 2–10.

Nakajima, T., Sankai, Y., Takata, S., Kobayashi, Y., Ando, Y., Nakagawa, M., et al. (2021). Cybernic treatment with wearable cyborg Hybrid Assistive Limb (HAL) improves ambulatory function in patients with slowly progressive rare neuromuscular diseases: a multicentre, randomised, controlled crossover trial for efficacy and safety (NCY-3001). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 16, 304. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01928-9

ROBOCARE CENTER Group, Neuro HALFIT. (2024). Available online at: https://robocare.jp/services/hal-fit/ (accessed July 4, 2024).

ROBOCARE CENTER Group, Robocare Center Locations and Fees. (2024). Available online at: https://robocare.jp/neuro-halfit-price/ (accessed July 4, 2024).

Sankai, Y., and Sakurai, T. (2017). Future of Cybernics and treatment of neurological disorders -Functional regenerative treatment with HAL. Neurol. Med. 86, 596–603.

Sankai, Y., and Sakurai, T. (2018). Exoskeletal cyborg-type robot. Sci. Robot 3:17. doi: 10.1126/scirobotics.aat3912

Saotome, K., Matsushita, A., Eto, F., Shimizu, Y., Kubota, S., Kadone, H., et al. (2022). Functional magnetic resonance imaging of brain activity during hybrid assistive limb intervention in a chronic spinal cord injury patient with C4 quadriplegia. J. Clin. Neurosci. 99, 17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2022.02.027

Shimizu, Y., Kadone, H., Kubota, S., Ueno, T., Sankai, Y., Hada, Y., et al. (2019). Voluntary elbow extension-flexion using single joint hybrid assistive limb (HAL) for patients of spastic cerebral palsy; two cases report. Front. Neurol. 10:2. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00002

Standring, S. (2016). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (41st ed.). London: Elsevier, 62–63.

US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration (2009). Guidance for Industry “Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims” (Silver Spring, MD), 1–39.

Watanabe, H., Goto, R., Tanaka, N., Kanamori, T., and Yanagi, H. (2016). Effects of Gait Training using a hybrid assistive limb® (HAL®) on quality of life and mood states and suitability of HAL for recovery phase stroke patients; a randomized controlled study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 31, 733–742. doi: 10.1589/rika.31.733

Watanabe, H., Marushima, A., Kadone, H., Ueno, T., Shimizu, Y., Kubota, S., et al. (2020). Effects of gait treatment with a single-leg hybrid assistive limb system after acute stroke; a non-randomized clinical trial. Front. Neurosci. 13:1389. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01389

Yamada, Y. (2019). “Visual narrative,” in Qualitative Research Methods Mapping, eds. S. Tatsuya, H. Kasuga, and M. Kanzaki (Shinyosya. In Japanese), 136–142.

Yamada, Y. (2021). Narrative Research - Co-emergence of Narratives. The Collected Writings of Yoko Yamada. Shinyosya. (in Japanese), 231–234.

Yasunaga, Y., Miura, K., Koda, M., Funayama, T., Takahashi, H., Noguchi, H., et al. (2021). Exercise therapy using the lumbar-type hybrid assistive limb ameliorates locomotive function after lumbar fusion surgery in an elderly patient. Case reports in orthopedics 2021:1996509. doi: 10.1155/2021/1996509

Keywords: Wearable Cyborg HAL, Cybernics Treatment, Techno Peer Support, Neuro HALFIT, patient reported outcome, narrative analysis, mutual feedback structure model in physical, mental, and social aspects

Citation: Ikemoto S, Sankai Y and Sakurai T (2025) Study on intervention effect of Wearable Cyborg HAL through narrative analysis. Front. Psychol. 16:1462072. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1462072

Received: 09 July 2024; Accepted: 10 March 2025;

Published: 02 April 2025.

Edited by:

Kenji Suzuki, University of Tsukuba, JapanReviewed by:

Takashi Nakajima, National Hospital Organization Niigata National Hospital, JapanCopyright © 2025 Ikemoto, Sankai and Sakurai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shiori Ikemoto, aWtlbW90b19zaGlvcmlAY3liZXJkeW5lLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.