94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 20 February 2025

Sec. Sport Psychology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1430002

This article is part of the Research Topic Psychological Factors in Physical Education and Sport - Volume V View all 16 articles

Introduction: The objective of this study was to explore the viewpoints of parents, teachers, and administrators on the factors influencing adolescent physical activity in China.

Methods: The study employed semi-structured interviews with school teachers, school principals, government officers, and parents. Twenty-five participants were recruited from Jiangsu Province, China, and completed the interview.

Results: The data collected were analysed using grounded theory within the social ecology model framework. The analysis identified 49 concepts across 19 subcategories and five main categories.

Discussion: The resulting theoretical model, constructed using grounded theory, integrated five main categories: individual factors, family environment, school environment, community environment, and policy. This model provides a foundational understanding of the multifaceted influencing factors of adolescent physical activity in China.

Participation in adequate amount of moderate-to-vigorous physical activities (MVPA) has been shown to be able to promote growth and physical fitness and reduce the risk of being overweight and obese in youth (Bull et al., 2020). The World Health Organization (WHO) physical activity guidelines recommend that children and adolescents aged 6–17 years should engage in at least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day, including vigorous physical exercise at least 3 days per week (Bull et al., 2020). However, the current adherence rate to these guidelines among Chinese school-aged children and adolescents stands at a mere 30% (National Health Commission and The Ministry of Education, 2020). Notably, some studies showed a gradual decline in physical activity levels as the children getting older (Hong et al., 2020; Piercy et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2019).

An individual’s health behaviour is influenced by a number of factors, not only at the individual level but also by the external social and physical environment (Sallis et al., 2015). McLeroy et al. proposed a socio-ecological model of health behaviour (McLeroy et al., 1988), which is a comprehensive framework based on multiple theories and helps to analyse the influences at the individual, interpersonal, organisation, community, and policy levels on health behaviour. Although several previous studies have explored the factors influencing physical activity among adolescents in China, most of them have only focused on the middle and proximal levels of the social ecology model (individual, interpersonal and organisation levels) (Hu et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2021; Quan and Lu, 2020). At present, in the context of China, there is a notable absence of studies that thoroughly encompass all five levels of the social ecology model in their analysis. Additionally, while a few studies have indeed utilised the social ecology model as a theoretical underpinning and adopted qualitative methods to examine factors influencing adolescent physical activity (Corr et al., 2019; Martins et al., 2015), qualitative research in this domain, especially within the context of China, remains markedly scarce.

In 1967, Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss introduced the grounded theory and methodological system in their monograph, The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (Glaser et al., 1968). The grounded theory is widely recognised as a rigorous and effective method in qualitative research (Oktay, 2012). The core of the method is the data collection and analysis process. The iterative process of comparative analysis and theoretical sampling ensures the reliability and validity of the resulting theory. Through repeated coding and constant comparison, researchers are able to gradually construct a theoretical model that closely reflects the reality of the studied population. This process not only ensures the scientific rigor of the results but also enhances the replicability and generalizability of the findings (Charmaz and Thornberg, 2021). The aims of this study, with a focus on the adult perspective, were to construct an initial conceptual model of factors influencing physical activity (PA) in China’s youth, and to provide a pool of items for scale development for future studies. A semi-structured interview was performed on school educators, government officers and parents. With the application of the grounded theory the interview transcripts were coded, generalised, refined and extrapolated to identify the influencing factors of PA participation, from which a conceptual model of the factors influencing children and adolescents’ physical activity was constructed.

This study used a semi-structured in-depth interview to collect and analyse qualitative data. In our study, we strategically concentrated on eliciting insights regarding adolescent behaviour from adults, specifically educators and parents, to capture a more encompassing perspective. Furthermore, the perspectives of adults are instrumental in delineating the various environmental and social factors that influence adolescent physical activity. This information is vital in formulating a robust intervention framework. Although this methodology primarily centres on adult viewpoints, it facilitates a thorough understanding of the multifaceted dynamics influencing adolescent physical activity, thereby enriching the depth of findings from our study. During the interviews, different participants’ attitudes, experiences and views about PA among young people were explored, the collected information was categorised, and the relationships between the identified factors were analysed (Mik-Meyer, 2020). The study used ‘theoretical sampling’, one of the core procedures of the grounded theory approach, as opposed to the ‘probability sampling’ approach used in quantitative research. The “theoretical sampling” is an iterative and ongoing process that integrates data collection, coding, and theory building (Glaser et al., 1968).

This study obtained approval by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin University of Sport, China, and the Human Research Ethics Committee of Southern Cross University, Australia (Approval number: Tianjin University of Sport 2020/03, Southern Cross University 2021/109).

Sample size can vary in qualitative research (Baker and Edwards, 2017). According to Quinn Patton (2002), the sample size depends on the study’s purpose and aim, the quality of the data, and the available time and resources. Previous researchers have utilised sample sizes ranging from 10 to 12 participants for their qualitative studies on physical activity (Saligheh et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2016; Warehime et al., 2019; Yüksel and Schoville, 2020), and shown that data saturation can be achieved in as few as 10 interviews (Sugiyama et al., 2010). Data saturation is one method used to determine an adequate sample size in qualitative studies (Francis et al., 2010) that refers to the point when a researcher no longer obtains substantive new information. In the current study, the researcher planned to recruit participants until the point where data saturation occurred, with a minimum of 15 participants.

All study participants signed an informed consent form, and their participation was entirely voluntary without receiving any financial benefit. The researcher contacted school principals and teachers of three local junior to senior high schools (school year 7–12), and asked them to reach students’ parents who met the eligibility criteria. In addition, the researcher contacted the relevant government departments to assist the researcher in recruiting government officers who met the inclusion criteria.

• Parents: (a) living in Nanjing City (China) at the time of the study, (b) with a child attending a junior or senior high school (school year 7–12), and (c) willing to participate in the interview.

• School Teachers: (a) working in a public or private high school during the study period, (b) with more than 4 years of teaching experience in physical education, and (c) willing to participate in the interview.

• School Principals: (a) working in a public or private high school during the study period, (b) with more than 4 years of teaching experience, and (c) willing to participate in the interview.

• Government officers: (a) working in a government education or sports department (e.g., Jiangsu Provincial Education Department, Jiangsu Provincial Sports Bureau), (b) with more than 4 years of work experience in the department, and (c) willing to participate in the interview.

An individual who was (a) unable or unwilling to complete the interview after agreeing to participate, or (b) unable to schedule an interview at a mutually convenient time for both the participant and the researcher.

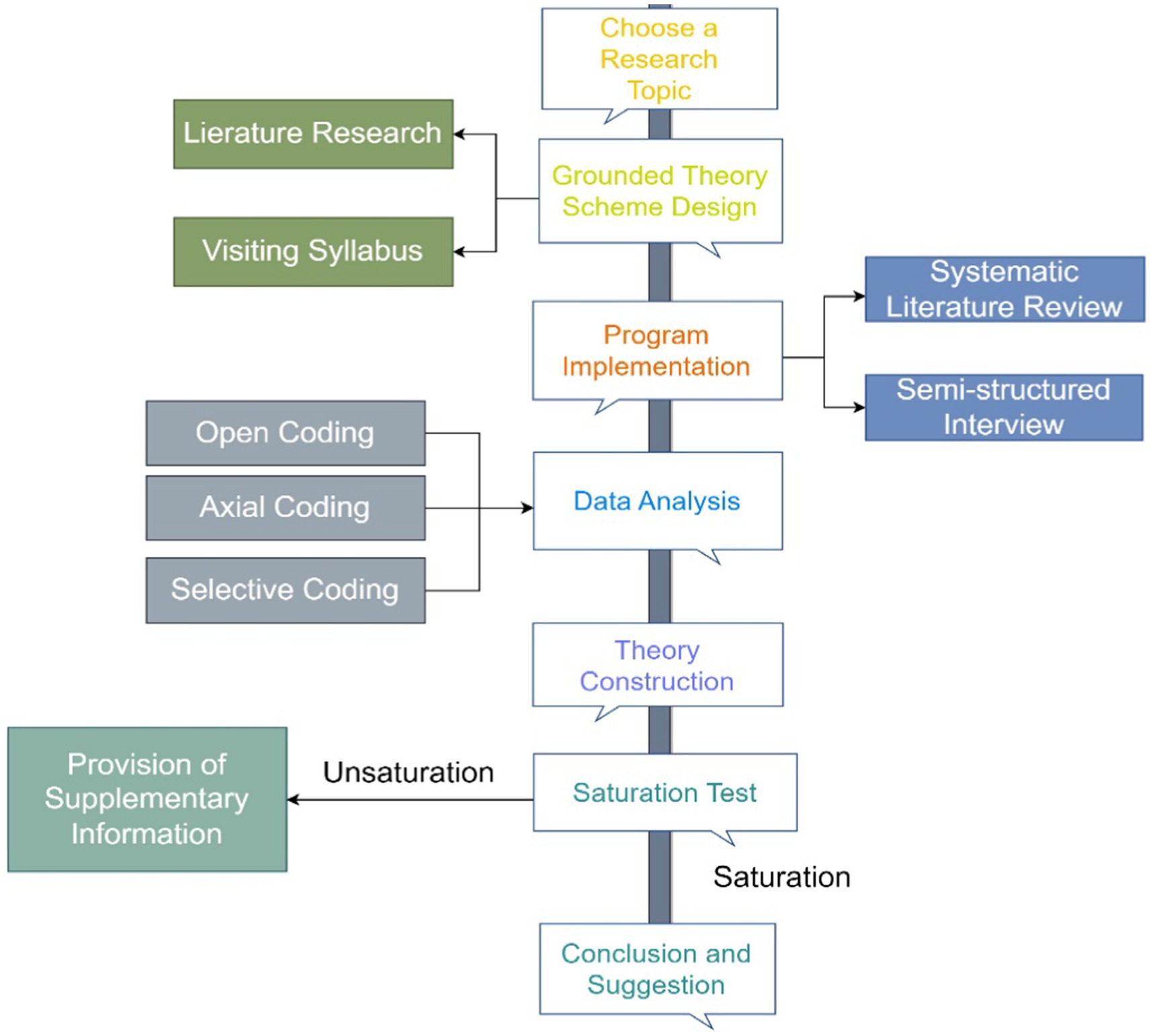

This study aimed to develop a conceptual framework for exploring the factors influencing adolescent physical activity, using a socio-ecological model. The data collected during the exploration process was analysed using grounded theory. The analysis process involved comparative analysis, classification, and conceptualisation of the operational process, aiming to regroup the concepts according to logical relationships to develop a core theory. The theory sampling scheme consists of three methods: open coding analysis, axial coding analysis, and selective coding analysis. In the grounded theory coding process, conceptual categories were iteratively compared and relationships between concepts were established, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the grounded theory research process adapted from Oktay (2012).

In the coding and analysis process, we used the NVivo 12.0 software developed by Qualitative Solutions for Research (QSR) Ltd. as a supplementary analysis tool to conduct the semi-structured in-depth interviews with different groups of participants (parents, teachers, principals and government officers), using the social ecology model proposed by McLeroy et al. (1988) as a theoretical framework to examine the responses at the individual, interpersonal, organisation, community and policy levels, respectively.

First, the data were collected and recorded during the interview with the questions corresponding to the above-mentioned five levels. Secondly, the original interview data was imported into the database and encoded to refine the initial concepts and assigned to the categories and establish the initial nodes. Thirdly, axial coding was carried out to refine the main categories. Finally, the selective coding was carried out to discover the core categories and establish the links between the core categories, using the social ecology model as the theoretical framework to construct a theoretical model of the influencing factors of school students’ physical activity using the grounded theory.

The data sources for this study were from the semi-structured in-depth interviews with parents, teachers, principals and government officers. The interview questions were derived from previous research literature (Hu et al., 2021; Langille and Rodgers, 2010; Webster and Suzuki, 2014). Interviews included explorations on the factors influencing current youth physical activity (both barriers and facilitators were included). Different questions were developed for the various roles (Table 1). Following the recommendations of the qualitative study (Mik-Meyer, 2020), we conducted an initial interview with an expert in the field of students’ physical health promotion (a professor from the Nanjing Normal University) before carrying out the formal interview. Subsequently, we revised the interview questions to improve clarity according to the feedback from the pilot interview.

The researcher informed the interviewees of the purpose of the study and explained the measures to protect privacy of participants’ information before asking the participants to sign the informed consent form. The interviews were completed over 20–40 min, at a mutually agreed location face-to-face or via online video interview (due to the local COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions). All interviews (online or face-to-face) were recorded using audio recording devices and notes were taken during the interview. Interviews were conducted from August to November 2021. The researcher converted the recordings and notes into text files at the end of the discussions and transferred the information into the Nvivo12 software. We employed professional transcribers skilled in handling various accents and speech patterns to ensure accurate transcription of interviews, which were recorded verbatim, including all spoken words and non-verbal cues. We conducted rigorous quality control by reviewing transcripts against audio recordings and, where possible, involved participants in reviewing their transcripts to validate accuracy. The final number of participants who completed the interview included nine parents, seven teachers, four principals and five government officers, with a total of 25.

To ensure the rigor and reliability of the findings, both internal and external validation procedures were applied. Internal validation was conducted through the constant comparison method during the data analysis process, ensuring that emerging themes were grounded in the data. External validation was performed by inviting independent experts to review the coding process and the final conceptual framework. These validation procedures were implemented at different stages of the research, including during the data analysis and after the initial conceptual model was developed.

In the coding and analysis process, we used NVivo 12.0 as a supplementary tool, employing the social ecology model by McLeroy et al. (1988) to analyse semi-structured interviews with parents, teachers, principals, and government officers at individual, interpersonal, organisational, community, and policy levels. First, data was collected and coded based on these five levels. For example, a teacher’s comment, “Over half of the students actively participated in the PE Cultural Festival,” was coded as “Sports atmosphere,” categorized under “School atmosphere.” Similarly, a parent’s response, “We encourage our child to stick with exercise,” was coded as “parental support” under “family support.” Axial coding was then used to refine categories like “family environment “and “school environment,” and selective coding followed to establish core categories and their relationships, forming a theoretical model of the factors influencing students’ physical activity.

The researcher invited a total of 15 parents, and 10 parents of students were willing to be interviewed. Nine parents (four fathers and five mothers) eventually completed the interviews at the agreed interview time and venue. Table 2 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the parents interviewed.

A total of nine teachers and five principals were invited by the researcher, and seven teachers and four principals eventually completed the interviews. Table 3 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the teachers and principals interviewed.

The researcher invited a total of eight government officers and five eventually completed the interview. Table 4 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the government officers interviewed.

The first step in theoretical sampling is open coding, which entails extracting initial concepts from all primary sources and editing and aggregating these concepts. This process requires the researcher to break down the raw data into actionable pieces for analysis, reflect on the data in memos, and summarise the data conceptually to form the initial concepts (Glaser et al., 1968). In this study, the initial ideas (A1–An) were created using Nvivo 12.0 to collate, categorise and summarise the interview recordings and notes, and coding them word by word to make the initial concepts. The initial ideas are refined, and the overlapping images are combined to form sub-categories. In the open coding process, 49 initial images (A1–A49) and 19 sub-categories (B1–B19) were obtained by refining representative statements. Table 5 shows the results of the open-ended coding, with information from some of the interviews listed in the table reflecting the open-ended coding process with representative initial statements.

The second central stage of coding is axial coding, which aims to discover and establish potential logical relationships between the subcategories and to combine the already refined subcategories relationally according to the principle of analogical relationships to form a more directed, selective and conceptual main category (Glaser et al., 1968). Our study used the socio-ecological model proposed by McLeroy et al. (1988) as a theoretical framework to generate 49 category connotations and 19 sub-categories in an open-ended coding process. Based on the results of the open-ended coding, we categorised the 19 sub-categories of the open-ended coding, resulting in five main categories (see Tables 6–10).

At the individual level, interviewees discussed the factors that could have influenced physical activity among young people in terms of individual factors. Gender was the most talked about topic, with parents, teachers, principals and government officers discussing the differences in physical activity between boys and girls. Girls were less active than boys (some girls preferred to be sedentary, while boys preferred to move or play ball games). The differences in physical activity levels due to gender are consistent with the findings of previous quantitative studies, which tend to be the result of pre-deposited biological factors. In addition, most parents interviewed felt that their children were physically active enough. Some parents and teachers responded that they were not satisfied with their children’s use of time as a cause of lack of time for physical activity, given their children’s preference to use electronic devices in their free time and lower efficiency in doing homework.

At the interpersonal level, all respondents indicated that the influence of the family environment significantly influenced children’s physical activity. Parental support was the most discussed topic in the family environment and was seen as the primary facilitator of children’s participation in physical activity. Parents were role models for their children; if they maintained an active lifestyle, their children would also become more active. In addition, parental sports accompaniment and sports supervision were all effective means of promoting physical activity in children.

Some teachers interviewed reported that some parents had a low awareness of PE and a bias towards the subject. They believed PE was not as important as the main subjects and did not bring benefits to the Chinese College Entrance Examination (CCEE). Some parents used ‘no sports time’ as a punishment and forbade their children to participate in physical activity if they did not achieve the desired academic performance. So, parents’ low awareness of the benefits of sports participation can prevent children from participating in physical activity.

Some government officers argued that ‘over-protection’ by parents could also discourage young people from participating in physical activity, as they were overly concerned about their children getting injured in sports and prohibited their children from participating in some highly competitive sports.

Regarding the family atmosphere and finances, some teachers said that children from single-parent families and families with more complex financial situations showed poorer performance in sports and did not participate in sports in general. Children from single-parent or intergenerational families might be more difficult having their parents or guardians accompany and supervise them and to develop exercise habits. The same is true for children from economically challenged families, where family income could limit spending on sports.

Some principals and teachers reported that in children with siblings, especially those of similar age, their physical activity levels were usually higher, and the siblings became more active together. Similarly, parents gave feedback that when children were with their peers, they became more active and often met up with friends to play sports such as football.

At the organisation level of social ecology, the school is the most critical location for adolescents to engage in physical activity. Adolescents spend most of their day at school, and the school environment directly impacts adolescent physical activity (Hou and Liu, 2019). This was confirmed in the research of this chapter, where teachers, principals, and government officers interviewed indicated that physical education facilities in the school environment had a direct impact on adolescents’ physical activity levels, with factors such as sports facilities, activity spaces, and the size of the residential district where the school is located, all affecting physical activity levels. Some parents reported that if the school was well-connected and not too far from home, their children could walk daily to and from school. Therefore, the accessibility and safety of the area around the school also contributed to the children’s physical activity level.

Parents and teachers generally believed that excessive academic pressure prevented young people from engaging in adequate levels of physical activity. The heavy academic load could lead to students being sedentary for long periods and not having enough time to participate in physical activity. Government officers had also stated that this was a common problem in schools today and that there were adverse health consequences for young people who were not physically active during the school days. However, some principals said that academic pressure and physical activity were not incompatible, as academic stress could not be avoided as children had to face secondary and higher education exams shortly. Physical activity is equally important and can be promoted in other ways, such as increasing the number of physical education hours, adjusting the content of physical education classes, and offering physical culture festivals.

Five out of nine parents indicated that the support and assistance of teachers were essential in promoting physical activity among young people. Parents reported that teachers’ supervision and the requirement to check off physical activity assignments in the social media groups, such as QQ and WeChat groups, had improved physical activity levels among young people.

Three out of seven teachers interviewed said that with the support and decision-making of school leaders, it would be much smoother for the campus to conduct sports competitions and sports culture festivals, and that the principal’s concern for sports and sports philosophy could directly drive the sports atmosphere across the campus. In addition, some teachers believed there was a severe shortage of PE teachers in schools and that they were generally too old to keep up with the times in terms of teaching methods, which could affect students’ learning of PE skills.

The richness of the PE curriculum and the variety of teaching methods could affect the students’ perception of psychological value, which indirectly affected physical activity levels. For example, boring running, rope skipping, or specific exercises for PE mid-term exams could make students feel bored and unmotivated, whereas ball games and aerobics were more popular among students. During the interviews, we learned that some schools had adopted an option-based and club-based approach to delivering PE lessons, providing students with various options to stimulate their interest in participating in physical activity. Some teachers interviewed said that the intensity of PE lessons could be reduced for safety reasons. However, on the other side, the reduced intensity and confrontation of PE lessons might result in students not achieving the required amount of exercise in class.

According to the parents interviewed, the lack of fitness equipment, gymnasiums, and sports venues in the communities where they lived had a negative impact on the daily physical activity of young people, and the fact that high costs for using sports venues and gymnasiums in the neighbourhood were also a deterrent for ordinary families. Parents believed building walking and cycling paths as part of urban planning or neighbourhood renewal would be a good idea. The construction of walking and cycling paths would positively impact young people’s physical activity.

Parents reported that “the sporting atmosphere in the community has a direct impact on the physical activity of young people, sometimes children play in the basketball court in the neighbourhood but are often being complained about by older residents who like to keep quiet,” “there are various sports training institutions around the neighbourhood, so parents also enrol their children in training courses in the neighbourhood,” “the fees are too expensive,” and “the fees are too high.” “Posters on exercise and health are often displayed in the community; now and then, community workers come to the neighbourhood to promote scientific fitness methods and free blood pressure and blood sugar tests.” These factors could directly or indirectly influence young people’s physical activity levels.

In addition, parents and teachers believed that weather conditions could also have a significant impact on physical activity when the children were out of school. Especially when it came to rain, snow, or hazy weather, the degree of warm and cold weather also affected their physical activity to some extent.

At the policy level, the school principals interviewed felt that the school sports events organised in recent years had motivated students and promoted physical activity among young people, such as the National School Football League organised by the Ministry of Education, which requires junior and senior secondary schools to participate in football training classes and the schools to participate in the national tournament after a competitive selection process. The abundance of competitions and the in-school selection system contributed to young people’s physical activity.

The parents interviewed said that the current education evaluation system was biased and that the value and significance of PE were not reflected in the educational performance evaluation system, especially in the recent selection tests, where the percentage of PE credits in the secondary school exams was not adequate, and the difference in PE achievements between students was not significant; the high school exams did not include PE scores, and PE classes were reduced to optional. The bias of the current education evaluation system was the root cause of the “emphasis on literature rather than martial arts” phenomenon, which was directly responsible for the low level of physical activity among young people. In addition, the lack of clear rewards and sanctions for PE in schools also affected students’ motivation to participate in activities. The current evaluation system was considered to directly impact young people’s physical activity levels.

Teachers, principals and government officers agreed that a series of physical education reform policy documents had contributed to young people’s physical activity in recent years. While previous policy require 1 h of daily physical activity for students, current documents required 1 h in and 1 h out of the school time. In addition, some principals suggested that implementing the “double reduction” policy (It refers to a policy implemented in China’s education system aimed at reducing the workload of primary and junior high school students in terms of homework and extracurricular training) had significantly reduced students’ school workload, leaving more time for leisure and physical activity. As a result, the policy from the education system directly impacted young people’s physical activity.

The teachers and government officers interviewed felt that the rigorous school monitoring process in Jiangsu Province had ensured that young people were physically active and that the provision of adequate physical education was no longer an issue in Jiangsu, but that the goal for the future was to establish a social monitoring mechanism and that a ‘two-pronged’ inspection policy would promote physical activity among young people.

Finally, some principals said that the (COVID-19) epidemic prevention and control policy could lead to a lack of physical activity among young people, as the closure of schools and public sports venues could have affected their physical activity.

After the open-ended and axial coding, selective coding is the last step in grounded theory analysis, where researchers select a core category and connect all the other categories around that core category. This process results in one unified theory that explains the research findings. Selective coding is a process that aims to extract the essence of the idea, which can be closely linked to other conceptual types to form a generalised theory (Glaser et al., 1968). The goal of selective coding is to extract the core categories from the main categories; and once the core categories were identified, they were linked to other classes through the model, and the links between the types had been hypothesised in the literature (Glaser et al., 1968; Mik-Meyer, 2020).

In the selective coding stage, this study repeatedly compared and analysed in depth the five main categories (individual factors, family environment, school environment, community environment and policy), formed in the axial coding stage, combined with the careful collation of the original interview data, systematically sorted out the relationships between the main categories and the factors influencing adolescents’ physical activity, and finally, after categorisation and refinement, formed 10 relationship structures, as shown in Table 11.

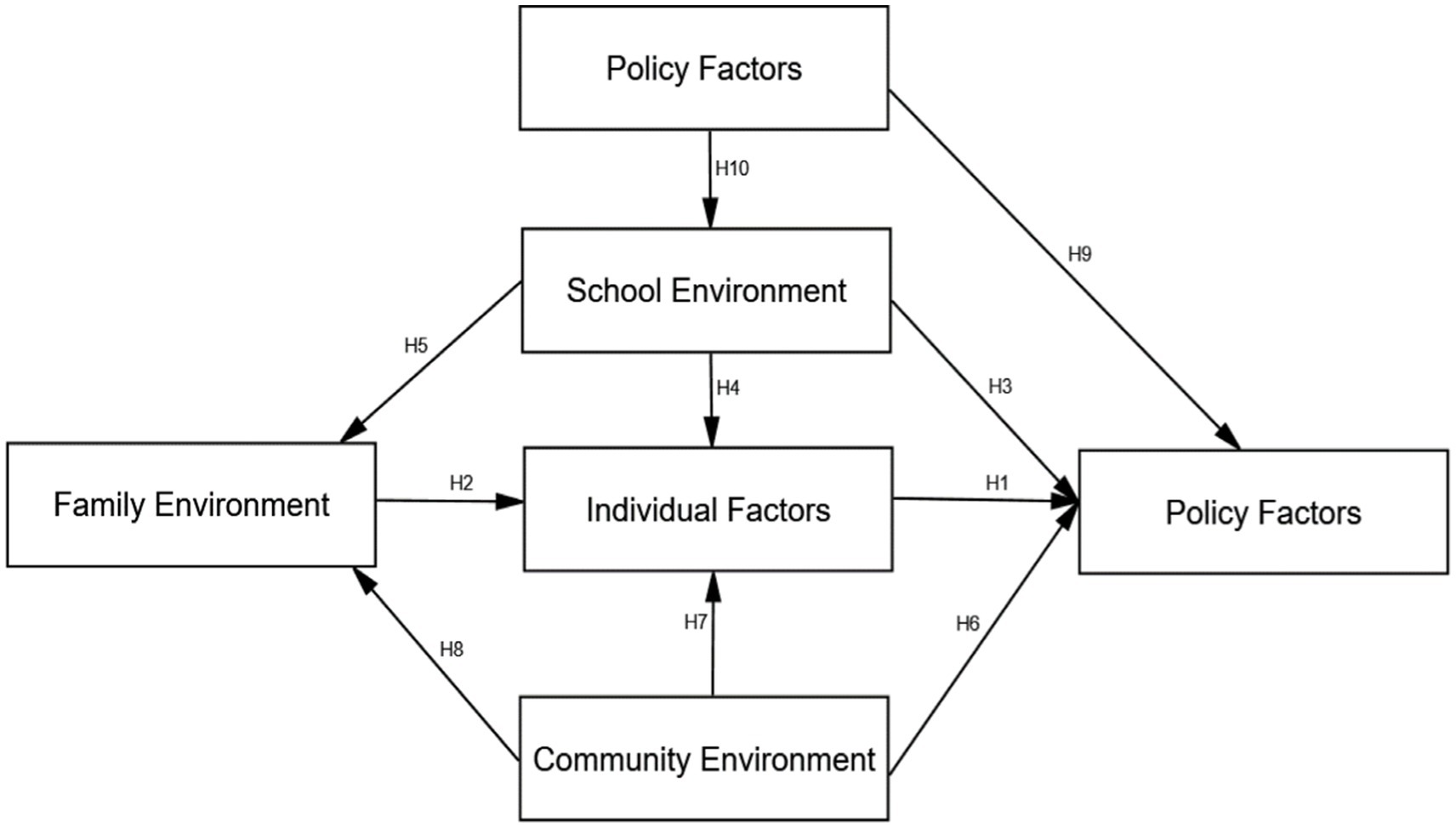

By analysing the linkages between the categories, the core categories that dominated the other major categories were extracted, and a conceptual model was constructed using an ‘unfolding storyline’ approach to describe the overall behavioural phenomena and contextual conditions (Glaser et al., 1968). The final core categories were: individual factors, family environment, school environment, community environment, and policy, and were developed through two storylines: “core category → youth physical activity” and “core category interaction → youth physical activity.” The initial model of the factors influencing adolescent physical activity was finally constructed, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Initial conceptual model of factors influencing physical activity in adolescents. H = hypothesis.

Direct and indirect effects describe the relationships among observed and latent variables in the model (Charmaz and Thornberg, 2021; Oktay, 2012). Direct effects refer to the direct influence of one variable on another, while indirect effects refer to the indirect influence of one variable on another through one or more intermediate variables. Figure 2 shows two pathway relationships of influencing factors: (1) Direct influence: individual factors, school environment, community environment, and policy all directly influence adolescent physical activity levels; (2) Indirect influence: community environment indirectly influences youth physical activity through the family environment and unique environment; policy indirectly influences youth physical activity through the school environment, family environment, and individual factors. Specifically, the following research hypotheses were formed.

H1: Individual factors → physical activity has a positive influence.

H2: The family environment has a positive impact on individual factors.

H3: The school environment has a positive effect on physical activity.

H4: School environment → individual factors have a positive effect.

H5: School environment → family environment has a positive influence.

H6: Community environment → physical activity has a positive effect.

H7: Community environment → individual factors have a positive effect.

H8: Community environment → family environment has a positive influence.

H9: Policy → physical activity has a positive effect.

H10: There is a positive effect of policy → school environment.

In this study, through the semi-structured interviews with parents, teachers, principals and government officers, and using the social ecology model as the theoretical framework, the researcher coded and analysed the interview texts and concluded that the main factors affecting youth physical activity included: individual factors, family environment, school environment, community environment and policy. This led to the construction of the Initial Model of Influencing Factors on Youth Physical Activity (Figure 2), which was structured with the following critical conceptual relationships.

1. Young people’s participation in physical activity was influenced by multiple factors, and the interrelationships were complex.

2. Individual factors included self-perception, self-efficacy, personality, and time efficiency, which were internal situational conditions that influenced adolescents’ physical activity and positively impacted physical activity behaviour.

3. The family environment included five dimensions: parental support, parental perception, family support, family economy, and family atmosphere, which were external situational conditions that influenced adolescents’ physical activity.

4. The school environment included facilities, climate, teachers’ influence, and curriculum. These dimensions were external situational conditions that influenced adolescents’ physical activity. The school environment could either directly and positively impact adolescents’ physical activity levels or indirectly influence physical activity levels through mediating variables.

5. The community environment included facilities, community sporting atmosphere, and natural factors, which were external situational conditions affecting youth physical activity.

6. Policy factors included teaching and competition policies, supervision and management policies, and epidemic prevention and control policies, which could directly and positively influence youth physical activity levels and indirectly influence physical activity levels through mediating variables.

7. Individual factors were the core category of factors influencing youth physical activity; family environment, school environment, and community environment were the keys to participation in physical activity; and policy factors were the guarantee of youth physical activity.

This study followed the principle of theoretical saturation. The purpose of the theoretical saturation test was to verify that the physical activity factors studied for adolescents were comprehensive and that the data collected covered all aspects of the respondents’ concepts, content, and connotations. The theoretical saturation test assesses the adequacy of the coding in the academic sampling process. If new ideas or definitions are identified during the trial, indicating that the theory is not saturated, further additional information needs to be collected to supplement the data. Based on the concepts defined by the open-ended coding, the categories formed, and the naming of the classes for a continuous round-robin examination to ensure the scientific validity of the refinement from concepts to types, we re-coded the remaining one parent interview transcript (P9), one teacher interview transcript (T7), one principal interview transcript (H4) and one government official interview transcript (G5) for analysis according to the above procedure, respectively, in that the coding process did not produce new conceptual connotations or new causal relationships, so it can be argued that the richness of the categories covered in this grounded theoretical model had reached saturation.

In this study, we examined the factors that could influence the physical activity of our youth at five levels using the social ecology model proposed by McLeroy et al. (1988) as a theoretical framework.

The study’s results suggest that the personal factors influencing physical activity include self-perception, self-efficacy, personality temperament, and time efficiency. The path of influence in the model was: individual factors → adolescent physical activity, indicating that adolescent physical activity is directly influenced by individual factors and that individual factors were internally causally related to adolescent physical activity. Consistent with previous findings, scholars have previously suggested that adolescent physical activity levels are directly related to individual factors such as psychological, physiological, and time management (Bengoechea et al., 2013; Stanley et al., 2013).

Psychologically, the levels of self-perception and self-efficacy significantly and positively affected physical activity levels, as found in this study. Self-perception, which indicates an individual’s insight and understanding of themselves, correlates statistically with physical activity levels (Ge et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012). “Self-efficacy,” a concept developed by Bandura in the 1970s, refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to use what they have to perform a behaviour (Bandura, 1977). It has been suggested that people tend to choose actions or tasks that they feel interested in or confident in completing. When individuals have a high level of “self-efficacy,” they are motivated to engage in the task or activity (Zhang et al., 2012). “Hobby,” “competitive striving,” and “athletic confidence” are the same categories in which “self-efficacy” is embedded.

Physiologically, it has been suggested that personality traits are a key factor in adolescent participation in physical activity (Guo and Wang, 2020) and that there are differences in physical activity between boys and girls, both in terms of amount and type of physical activity (Pawlowski et al., 2014). Our interviews also reflected this view, where parents and teachers generally responded that girls preferred a sedentary lifestyle. In contrast, boys preferred more confrontational physical activities, such as various ball sports events. In this study, we found that individual factors such as ‘temperament’ and ‘time efficiency’ had an impact on physical activity participation behaviour, which has rarely been discussed in previous studies.

Our findings suggested that the family environment influenced physical activity in five dimensions: parental support, parental perceptions, family support, family finances and family climate. The path of influence in the model was: family environment → individual factors, → adolescent physical activity, indicating that the family environment indirectly influenced adolescent physical activity levels by using individual factors as mediating variables. Our findings are consistent with previous studies, in which Kahn et al. (2008) and Liu et al. (2021) concluded that support from parents and friends could enhance children and adolescents’ self-efficacy and self-perceptions, thus indirectly contributing to physical activity levels. At the same time, our study suggests that the family environment has a direct and positive effect on individual factors in adolescents. Parental support,” “parental perception” and “family atmosphere” in the family environment have an immediate positive impact on the individual factors of children’s “self-perception” and “self-efficacy.” “The family environment, including ‘parental support’, ‘parental perceptions’ and ‘family atmosphere, can have a significant impact on individual factors such as children’s ‘self-perceptions’, ‘self-efficacy’, ‘personality traits’ and ‘time efficiency. The interviews revealed that parental supervision enhanced children’s time management efficiency; parental exercise habits developed children’s perception of sports; parental encouragement and support enhanced children’s self-efficacy, and a harmonious family atmosphere developed children’s temperament and personality. The results of our study are in line with Dagkas and Quarmby (2012) and Huang et al. (2019), which concluded that the family environment directly impacts individual factors of adolescents.

The results of this study suggested that the school environment influenced physical activity in four dimensions: school facilities, climate, teacher influence, and curriculum. The pathways of power in the initial model suggest that the school environment can influence physical activity levels both directly and indirectly through the home environment and individual factors as mediating variables. Schools are considered the best place to practise wellness programmes and implement physical activity interventions (Hou and Liu, 2019). Some scholars have discussed the influence of the school environment on adolescents’ physical activity levels in terms of school facilities, physical education climate, and teacher influence and concluded that the school environment has significant predictive power for physical activity behaviour in adolescents (Chen et al., 2018; Dai and Chen, 2019; Hou and Liu, 2019). Some scholars have also indicated that increasing the number of physical education classes by adjusting the delivery of school physical education courses is an effective way to promote physical activity among adolescents (Luo et al., 2021; Pawlowski et al., 2014; Stanley et al., 2012). The results of previous studies have shown the importance of the school environment on physical activity, and we have come to the conclusion, consistent with our predecessors, that physical activity can be directly and positively promoted among adolescents in schools by improving school physical education facilities, spreading school physical education culture, optimising the content of physical education courses and enhancing physical education teachers.

The results of this study showed that the community environment influenced physical activity in three dimensions: facility configuration, community sporting atmosphere and natural factors. The influence pathway in the initial model showed that the community environment could influence physical activity levels both directly and indirectly through family environment and individual factors as mediating variables. Regarding the influence of the community environment, our results are consistent with previous studies (D'Angelo et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2014) that describe the impact of community sports facilities and community sporting climate on youth physical activity. For example, lack of fitness equipment and sports fields, and lack of walking greenways and bicycle paths can constrain youth physical activity participation (Wilk et al., 2017). Therefore, improving accessibility, promoting active transportation and enhancing community sports facilities are helpful in increasing youth physical activity levels (D'Angelo et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2021; Stanley et al., 2012). In addition, the current study found that environmental factors such as climatic conditions and air quality could also affect youths’ physical activity participation, in line with studies by scholars such as Li et al. (2021) and Huang et al. (2019).

The results of this study suggested that policy factors affecting physical activity included three dimensions: teaching and competition policy, supervision and management policy, and epidemic prevention and control policy. Previous studies on youth physical activity have rarely addressed policy-level factors, probably because the venues for youth physical activity are mainly in the community or schools, so most previous studies have focused on schools and communities for investigation. In this study, in order to provide a more comprehensive overview of the factors influencing adolescent physical activity, and also to quantify the effect of policy on physical activity, we used the McLeroy et al. (1988)’s social ecology model as a theoretical framework to summarise the policy factors using rooting theory and proposed a pathway for the influence of policy factors on physical activity. The pathways of influence in the initial model showed that policy could affect physical activity levels both directly and indirectly through the school environment as a mediating variable. Our findings are consistent with foreign scholars, as Langille and Rodgers (2010) stated that “physical education policies or health promotion policies developed at the provincial (state) and municipal levels have a top-down, one-way path of influence on schools.” The implementation of the policy relies on the school as a platform and therefore the school environment plays a mediating role in the implementation of the policy.

From the initial conceptual model we can see that individual factors, as a central category in adolescent physical activity, have a direct impact on physical activity behaviour, but that individual factors are themselves subject to influence from the external environment. Bandura argues that “when environmental conditions exert a powerful influence on individual behaviour, they become the overriding determinant (Bandura, 1986). The family environment, school environment and community environment play a key role in adolescent physical activity as extra-individual environmental factors, either directly or indirectly through individual factors. Therefore, the integration of the family, school and community environments is extremely important in promoting physical activity among young people. As one government official (G1) stated, “Promoting physical activity among young people requires the cooperation of home, school and community.” Schools provide the physical education curriculum, while the home and community environment is a useful extension and supplement to the school physical education curriculum. In future, the promotion of youth physical activity will require a shift from the school-led approach to a ‘trinity’ of family, school and community partnerships to effectively improve youth physical activity levels. The policy factor is the outermost and most macroscopic factor in the social ecology model proposed by McLeroy et al. (1988) and its impact on physical activity is most extensive. In recent years, the Chinese government has promulgated various policy documents to support this in order to improve the level of physical activity and promote the physical health of young people, for example, in August 2020, the Opinions on Deepening the Integration of Physical Education and Promoting the Healthy Development of Youth was jointly issued by the Ministry of Education and the General Administration of Sports of China, and in October of the same year, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the Opinions on comprehensively strengthening and improving school physical education work in the new era. These policy documents provide ideas and bases for the reform of school sports development. In the process of implementing the policies, it is necessary to develop a monitoring and inspection system to prevent formalism and laissez-faire in order to guarantee the implementation of physical exercise standards for young people and to ensure that students have 1 h of physical activity both within and outside school during school days.

Despite the valuable insights generated, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size of 25 participants, while sufficient for data saturation in qualitative research, may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study was conducted in Jiangsu Province, and the findings may not fully represent experiences in other regions of China. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating larger samples, including adolescents’ perspectives, and expanding to different geographical areas.

This study utilised semi-structured interviews with teachers, principals, government officers, and parents to assess the factors influencing adolescent physical activity in China. Utilising the grounded theory within the social ecology model framework, the research identified 49 concepts across 19 subcategories and five main categories. The resulting initial model, which integrated the five main categories, provided a foundational understanding of the multifaceted influencing factors of adolescent physical activity in China.

To further promote adolescent physical activity, policies should focus on strengthening physical education programmes and encouraging collaboration between families, schools, and communities, while future research should include adolescents’ perspectives and explore regional differences and long-term policy impacts.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin University of Sport, China, and the Human Research Ethics Committee of Southern Cross University, Australia (Approval number: Tianjin University of Sport 2020/03, Southern Cross University 2021/109). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DH: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Validation. SZ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZC-M: Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was undertaken as part of the Major Research Project in Philosophy and Social Sciences of Jiangsu Province Universities, China [grant number 2023SJZD142]. Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [grant number SKCX2023016].

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Baker, S. E., and Edwards, R. (2017). How many qualitative interviews is enough? Expert voices and early career reflections on sampling and cases in qualitative research. Southampton: National Centre for Research Methods.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 4, 359–373. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Bengoechea, E. G., Fabrigar, L. R., Francisco Ruiz, J., and Paula Louise, B. (2013). Delving into the social ecology of leisure-time physical activity among adolescents from south eastern Spain. J. Phys. Act. Health 10, 1136–1144. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.8.1136

Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., et al. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1451–1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

Charmaz, K., and Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 305–327. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357

Chen, H., Dou, L., and Jiang, Y. (2018). Interpretation and insights of the "comprehensive school physical activity program" in the United States. J. Phys. Educ. 25, 98–104. doi: 10.15882/j.cnki.jsuese.2018.02.021

Corr, M., McSharry, J., and Murtagh, E. M. (2019). Adolescent girls’ perceptions of physical activity: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Am. J. Health Promot. 33, 806–819. doi: 10.1177/0890117118818747

Dagkas, S., and Quarmby, T. (2012). Young people’s embodiment of physical activity: the role of the ‘Pedagogized’ family. Sociol. Sport J. 29, 210–226. doi: 10.1123/ssj.29.2.210

Dai, J., and Chen, H. (2019). Socio-ecological factors and pathways of physical activity behavior promotion in adolescents' schools. J. Shanghai Inst. Phys. Educ. 43, 85–91. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1000-470X.2019.03.017

D'Angelo, H., Fowler, S. L., Nebeling, L. C., and Oh, A. Y. (2017). Adolescent physical activity: moderation of individual factors by neighborhood environment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 52, 888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.013

Francis, J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., et al. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 25, 1229–1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015

Ge, S., Guo, X., and Yan, F. (2015). A study on the self-perception of physical activity behaviors of junior high school students in Tianjin. China School Health 36:1016–1018+1021. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-9817.2015.07.001

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., and Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nurs. Res. 17:364. doi: 10.1097/00006199-196807000-00014

Guo, Q., and Wang, X. (2020). Deconstruction and reconceptualization of children and adolescents' physical activity behaviors - based on a social ecological perspective. J. Shenyang Inst. Phys. Educ. Sports 39:17–22+36.

Hong, J., Chen, S., Tang, Y., Cao, Z., Zhuang, J., Zheng, Z., et al. (2020). Associations between various kinds of parental support and physical activity among children and adolescents in Shanghai, China: gender and age differences. BMC Public Health 20, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09254-8

Hou, X., and Liu, J. (2019). Effects of school-level intervention strategies on adolescents' physical activity levels. School Health in China 40, 1110–1116.

Hu, D., Zhou, S., Crowley-McHattan, Z. J., and Liu, Z. (2021). Factors that influence participation in physical activity in school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic review from the social ecological model perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:3147. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063147

Huang, M., Zhang, Y., and Sun, H. (2019). Research on the promotion mechanism of college students' sports lifestyle in China based on the social ecological model. J. Tianjin Inst. Phys. Educ. 34, 14–22.

Kahn, J. A., Huang, B., Gillman, M. W., Field, A. E., Austin, S. B., Colditz, G. A., et al. (2008). Patterns and determinants of physical activity in us adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 42, 369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.143

Langille, J.-L. D., and Rodgers, W. M. (2010). Exploring the influence of a social ecological model on school-based physical activity. Health Educ. Behav. 37, 879–894. doi: 10.1177/1090198110367877

Li, M., Niu, M., and Zhang, D. (2021). Analysis of the barriers to female sports participation among adolescents aged 14-17 in China: a socio-ecological mode. J. Wuhan Inst. Sports 55, 25–32.

Liu, J., Hou, X., and Guan, J. (2021). Influence of family sports environment characteristics on physical activity levels of adolescents. Chinese Public Health 37, 1556–1561. doi: 10.16606/j.cnki.cjph.2021.10.008

Luo, X., Zhang, X., and Lu, C. (2021). Research on the holistic governance of youth physical activity at home, school and community. J. Wuhan Inst. Phys. Educ. 55, 33–40.

Martins, J., Marques, A., Sarmento, H., and Carreiro da Costa, F. (2015). Adolescents’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of physical activity: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Educ. Res. 30, 742–755. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv042

McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., and Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 15, 351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401

National Health Commission and The Ministry of Education. (2020). China to contain childhood obesity. National Health Commission and the Ministry of Education. Available at: https://govt.chinadaily.com.cn/s/202010/29/WS5f9a6499498eaba5051bc384/china-to-contain-childhood-obesity.html (Accessed Feburary 20, 2021).

Pawlowski, C. S., Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T., Schipperijn, J., and Troelsen, J. (2014). Barriers for recess physical activity: a gender specific qualitative focus group exploration. BMC Public Health 14:639. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-639

Piercy, K. L., Troiano, R. P., Ballard, R. M., Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Galuska, D. A., et al. (2018). The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 320, 2020–2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854

Quan, X., and Lu, C. (2020). Peer effects and gender differences in youth physical activity. J. Shanghai Inst. Phys. Educ. 44, 41–49.

Saligheh, M., McNamara, B., and Rooney, R. (2016). Perceived barriers and enablers of physical activity in postpartum women: a qualitative approach. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0908-x

Sallis, J. F., Owen, N., and Fisher, E. (2015). Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 5, 43–64.

Schmidt, L., Rempel, G., Murray, T. C., McHugh, T.-L., and Vallance, J. K. (2016). Exploring beliefs around physical activity among older adults in rural Canada. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well Being 11:32914. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.32914

Stanley, R. M., Boshoff, K., and Dollman, J. (2012). Voices in the playground: a qualitative exploration of the barriers and facilitators of lunchtime play. J. Sci. Med. Sport 15, 44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.08.002

Stanley, R. M., Boshoff, K., and Dollman, J. (2013). A qualitative exploration of the "critical window": factors affecting Australian children's after-school physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 10, 33–41. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.1.33

Sugiyama, T., Francis, J., Middleton, N. J., Owen, N., and Giles-Corti, B. (2010). Associations between recreational walking and attractiveness, size, and proximity of neighborhood open spaces. Am. J. Public Health 100, 1752–1757. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.182006

Warehime, S., Snyder, K., Schaffer, C. L., Bice, M., Adkins-Bollwit, M., and Dinkel, D. (2019). Exploring secondary science teachers' use of classroom physical activity. Phys. Educ. 76, 197–223. doi: 10.18666/TPE-2019-V76-I1-8361

Webster, C. A., and Suzuki, N. (2014). Land of the rising pulse: a social ecological perspective of physical activity opportunities for schoolchildren in Japan. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 33, 304–325. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2014-0003

Wilk, P., Clark, A. F., Maltby, A., Smith, C., Tucker, P., and Gilliland, J. A. (2017). Examining individual, interpersonal, and environmental influences on children's physical activity levels. SSM Popul. Health 4, 76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.11.004

World Health Organization (2019). Global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Yan, A. F., Voorhees, C. C., Beck, K. H., and Wang, M. Q. (2014). A social ecological assessment of physical activity among urban adolescents. Am. J. Health Behav. 38, 379–391. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.3.7

Yüksel, H., and Schoville, M. (2020). How teachers perceive healthy eating and physical activity of primary school children. Ilkogretim Online 19, 252–268. doi: 10.17051/ilkonline.2020.655802

Keywords: physical activity, children, adolescents, social ecology model, the grounded theory

Citation: Hu D, Zhou S, Crowley-McHattan ZJ and Liu Z (2025) Factors that influence participation in physical activity in Chinese teenagers: perspective of school educators and parents in respect of the social ecology model. Front. Psychol. 16:1430002. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1430002

Received: 09 May 2024; Accepted: 30 January 2025;

Published: 20 February 2025.

Edited by:

Manuel Gómez-López, University of Murcia, SpainReviewed by:

Liliana Ricardo Ramos, Polytechnic Institute of Santarém, PortugalCopyright © 2025 Hu, Zhou, Crowley-McHattan and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Donglin Hu, ZG9uZ2xpbmh1QG5qYXUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.