- Cambridge Institute for Music Therapy Research, Faculty of Arts, Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Creative Industries, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Introduction: Eating disorders (ED) are characterized by serious and persistent disturbances with eating, weightcontrol, and body image. Symptoms impact physical health, psychosocial functioning, and can be life-threatening. Individuals diagnosed with an ED experience numerous medical and psychiatric comorbidities due to issues caused by or underlying the ED. Therefore, it is vital to address the complex nature of an ED, as well as the comorbid and underlying issues. This necessitates a psychotherapeutic approach that can help to uncover, explore, and support working through unresolved emotions and experiences. Guided Imagery and Music (GIM) is an in-depth music psychotherapy approach utilizing therapist-programmed music to support the client in uncovering and examining underlying and unresolved issues. The literature surrounding the use of GIM with clients in ED treatment is anecdotal and comprised primarily of clinical case studies.

Method: This secondary analysis, based on a descriptive feasibility study that integrated GIM sessions into the client’s regular ED treatment and examined 116 transcripts from a series of sessions of eight clients.

Results: Thematic analysis of the transcripts identified nine subthemes and three themes that emerged. These themes include emotional landscape (feeling stuck, acknowledging emotions, and working through unresolved emotions), relationships (self, others, and eating disorders), and transformation and growth (finding strength, change, and empowerment). A short series of GIM sessions helped ED clients identify and address issues underlying the ED and to gain or reclaim a sense of self that enabled them to make choices for their life that support their recovery and sense of empowerment. Intertextual analysis revealed imagery indicative of the Hero’s Journey.

Discussion: Further, how engagement in this embodied aesthetic experience stimulates perceptual, cognitive, and affective brain functions which are key in fostering behavioural and psychological change is explicated as it relates to ED treatment and recovery.

1 Background

The hallmark characteristics of eating disorders (EDs) include the persistent disturbance of eating behaviors, weight control, and body image. These behaviors significantly impact one’s relationship with their body and weight, as well as their physical health and psychosocial functioning (American Psychological Association, 2013). Accurate estimates regarding how many individuals worldwide struggle with an ED are challenging, as many do not seek treatment due to feeling embarrassed to report symptoms or being in denial of symptoms (Smink et al., 2012; Steward and Robinson, 2018). Projections indicate that 70 million people worldwide are diagnosed with an ED and incidence rates have been increasing since early 2000, including increases in severe ED cases and a 66% increase in hospital admissions in 2020 (Beat Eating Disorders, 2021; Hott et al., 2015; Keel, 2018; Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007; Rikani et al., 2013; Steinhausen and Jensen, 2015; STRIPED Harvard, 2020).

While EDs are characterized by a range of behaviors related to eating, weight, and body image, these manifest differently with each diagnosis. Individuals diagnosed with anorexia nervosa (AN) experience low body weight and an intense fear of gaining weight, while those with Bulimia nervosa (BN) experience episodes of bingeing and purging. Individuals with binge eating disorders (BED) demonstrate a lack of control related to eating and engage in overeating food in a short period of time (American Psychological Association, 2013). EDs are not characterized by a single risk factor or cause. The growing body of literature indicates there are multiple risk factors that impact the development of an ED (Ely and Kaye, 2018). These include three distinctive areas: (1) genetic, (2) psycho-developmental, and (3) sociocultural factors (Anderson-Fye, 2018; Jacobi et al., 2018; Stice and Shaw, 2018; Vögele et al., 2018; Wade and Bulik, 2018; Wade et al., 2006). Researchers and clinicians recognize that the entangled nature of these risk factors along with comorbid health issues and mental health diagnoses can prolong ED symptoms (Rikani et al., 2013). This type of complex constellation suggests that attention be given to understanding if a risk factor is an integral part of the ED (i.e., body dissatisfaction) or the effect of the prolonged disordered eating or symptom use (i.e., mood disturbances or changes in serotonin) (Abbate-Daga et al., 2014; Backholm et al., 2013; Biffl et al., 2010; Braun et al., 1994; Bulik et al., 2004; Costello and Angold, 1995; Faje et al., 2014; Fairburn et al., 1999; Halmi et al., 2000; Wade and Bulik, 2018). This broaden perspective recognizes that one’s overall health is impacted by contextual and interactive factors, as well as an understanding of the unique characteristic of their illness (Martin and Felix-Bortolotti, 2010).

2 Eating disorders: a complex clinical profile

The concept of a complex clinical profile is a broad way of understanding that health and various aspects that contribute to one’s health are impacted and complicated by one’s unique circumstances (Manning and Gagnon, 2017; Martin and Felix-Bortolotti, 2010). In the context of an individual diagnosed with an ED, psychological and medical comorbidities, as well as social and cultural factors impact the treatment and recovery process (Anderson-Fye, 2018; Halmi, 2018; Mehler, 2018). This acknowledges the interactive nature of these comorbidities and sociocultural factors and their collective impact on ED treatment and recovery.

Individuals diagnosed with an ED experience a significant incidence of psychiatric comorbidities, specifically anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, personality disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Braun et al., 1994; Costello and Angold, 1995; Faje et al., 2014; Halmi et al., 2000; Herzog et al., 1992; Hudson et al., 2007; Kaye et al., 2004; Tagay et al., 2014). Medical complications are common due to weight loss, malnutrition, purging, and overeating (Mehler, 2018). The frequency and severity of ED behaviors impacts every system of the body causing cardiac complications, pulmonary abnormalities, gastrointestinal issues, hematologic disorders (i.e., leukopenia and anemia), diminished neurological functioning, impaired endocrine processing, dermatological issues (i.e., thinning hair, brittle nails, cyanotic extremities, and lanugo hair growth on the face), and reduced bone metabolism (leading to osteopenia and osteoporosis) (Biffl et al., 2010; Faje et al., 2014; Kaplan and Nobel, 2018; Kraeft et al., 2013; Lamzabi et al., 2015; Mascolo et al., 2015; Mehler, 2018; Miller et al., 2004; Roberto et al., 2011; Sabel et al., 2013; Strumia, 2012; Westermoreland et al., 2016). There are also personality traits (i.e., perfectionism) that are intertwined with and impact the ED (Burke et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018; Keel and Brown, 2010; LaMarre and Rice, 2021; Le Grange and Rienecke, 2018; Lester, 2019; Silber et al., 2011; Steward and Robinson, 2018; Wonderlich et al., 2012; Zander and Young, 2014).

This complex collection of symptoms also impacts an individual’s thought patterns, affective processing, and mood states and while these can be common issues to address, ED diagnoses differ regarding their symptomatologic constellation and clinical presentation. A growing body of literature indicates that neural activity and neurofunctional correlates distinct to each disorder occur in different areas of the brain (Celeghin et al., 2023; Wonderlich et al., 2021). Individuals with AN demonstrate a hyperactivity in the amygdala (AMG), insula (INS), and hypothalamus that is associated with control and emotion dysregulation (Carlèn, 2017; Celeghin et al., 2023; Wonderlich et al., 2021). Clients with BN struggle with impulsivity and emotion regulation, which is a result of hyperactivity in the INS and striatum (STR); whereas individuals with BED display dissociative and addictive behaviors which are indicated in the temporal cortex and STR (Celeghin et al., 2023; Wonderlich et al., 2021).

Individuals diagnosed with EDs also report a high incidence of childhood maltreatment and having experienced traumatic events (Brewerton, 2019). Addressing these diverse and myriad needs warrants treating the client wholistically by understanding their clinical manifestation, recognizing that EDs develop through a multi-causal process, and that the interaction of these different factors necessitate tailoring treatment (Hester and Sheehy, 1990; Heiderscheit, 2008; Le Grange and Eisler, 2009; Linehan, 2014; Le Lock et al., 2001; McFerran and Heiderscheit, 2015; McNeece and DiNitto, 2011; Trondalen, 2016b; Celeghin et al., 2023). Further, the psychotherapeutic therapeutic process requires structure and pacing to foster safety to avoid triggering ED behaviors or trauma (Burke et al., 2018; Dyer and Corrigan, 2021; Favaro et al., 2003; Guarda et al., 2018; Heiderscheit and Madson, 2015; Heiderscheit and Murphy, 2021; Ogden et al., 2006; van der Kolk, 2014; Wilson, 2018).

2.1 Eating disorder treatment

There are several therapeutic approaches commonly implemented in ED treatment which include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), family-based therapy (FBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) (Agras and Robinson, 2018). Each therapeutic approach has a unique focus, with CBT targeting thoughts and feelings related dysfunctional evaluation of one’s weight and body, DBT aimed at addressing affect regulation, FBT utilizing the family as a resource to reduce and eliminate ED behaviors, and IPT striving to develop awareness of how interpersonal relationships impact the ED (Burke et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018; Le Grange and Rienecke, 2018; Wilson, 2018). While each approach addresses different therapeutic needs, research indicates ED treatment is effective for 50% of clients (Levinson et al., 2021).

There is limited research of the use of creative arts therapies (CATs) in ED treatment (Heiderscheit, 2015a), yet emerging evidence the field of neuroaesthetics indicates that the aesthetic experience is a necessary and instrumental, as it stimulates perceptual, cognitive, and affective brain functions that are key in fostering behavioral and psychological change (Vaisvaser et al., 2024). It is postulated that the complex interplay of therapeutic factors in the aesthetic experience, create space for the client’s context and subjective experiences to be key elements in making meaning and fostering change in the therapeutic process (Jacobsen, 2006; Vaisvaser et al., 2024). The aesthetic experience fosters clients experience of therapeutic factors including externalization, embodiment, and symbolization (Kushnir and Orkibi, 2021; Kirsch et al., 2016; de Witte et al., 2021).

In the CATs, the externalization process allows an individual to cognitively shape the therapeutic issue in a manner that provides a sense of safety and to exert control over their engagement with it. Their ability to create this distance allows them to feel the intensity of the emotions, to be immersed in the moment and to feel safe (Vaisvaser et al., 2024). Processing these emotions fosters embodiment which facilitates the brain–body–mind connection, changing one’s perception and awareness as they access body memories (Vaisvaser, 2021; Vaisvaser et al., 2024). Lastly, in CATs, symbolic and metaphoric representations of the client’s inner experiences are expressed by bringing the subconscious into conscious awareness, thus offering opportunity for meaning making (Imus, 2021; Vaisvaser et al., 2024).

Aesthetic experiences that are inherent in CATs support increased connectivity and activity in various neural networks, including motor, reward, and sensory networks, as well as salience network, which is integral to interoceptive inference and awareness (Kennett et al., 2023; Vaisvaser et al., 2024). Engaging multisensory experiences fosters an integration of interoceptive, proprioceptive, and exteroceptive input that supports as a client’s sense of agency, as they can direct and control the ways they engage (Salvato et al., 2019). One such CATs method that provides this aesthetic experience and fosters the brain–body–mind connection is the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (GIM).

2.2 GIM in ED treatment

GIM is an in-depth music psychotherapy approach integrating listening to sequenced classical music to elicit and explore feelings, images, experiences, and memories. GIM helps to foster insights, develop awareness and self-understanding, as well as support personal growth and development (Bonny, 1994; Bonny and Savary, 1990; Grocke, 2019). This receptive method utilizes therapist-selected and programmed music specifically designed to meet the individual where they are in their therapeutic process and adapted to meet their needs moment to moment (Heiderscheit, 2023). GIM is designed to uncover unexpressed emotions and unresolved issues from the subconscious to allow the client to bring them into their conscious awareness (Ahonen, 2019; Beck et al., 2018; Bonny, 1994; Bonny and Savary, 1990; Clark and Keiser, 1986; Grocke, 2019; Goldberg, 1995; Goldberg, 2019; Heiderscheit, 2017). As clients listen to music in a relaxed state, they can access unresolved and repressed thoughts, feelings, and experiences, projecting them onto the music and imagery to bring them into their conscious awareness for exploration and discovery (Pickett, 1991).

The literature surrounding the use of GIM in ED treatment is limited to anecdotal evidence and clinical cases. This body of literature indicates that GIM has assisted clients in exploring and addressing unresolved feelings, confronting perfectionistic tendencies, working through body image issues, address anxiety, depression, and self-harm, work through trauma, explore origins of the ED, and discover inner resources (Barmore, 2017; Gargaro et al., 2016; Heiderscheit, 2016a, 2016b; Heiderscheit, 2015b; Heiderscheit, 2013; Noer, 2015; Papanikolaou, 2015; Pickett, 1991; Trondalen, 2016a; Trondalen, 2011). This clinical and anecdotal evidence indicates a need for more rigorous quantitative and qualitative research.

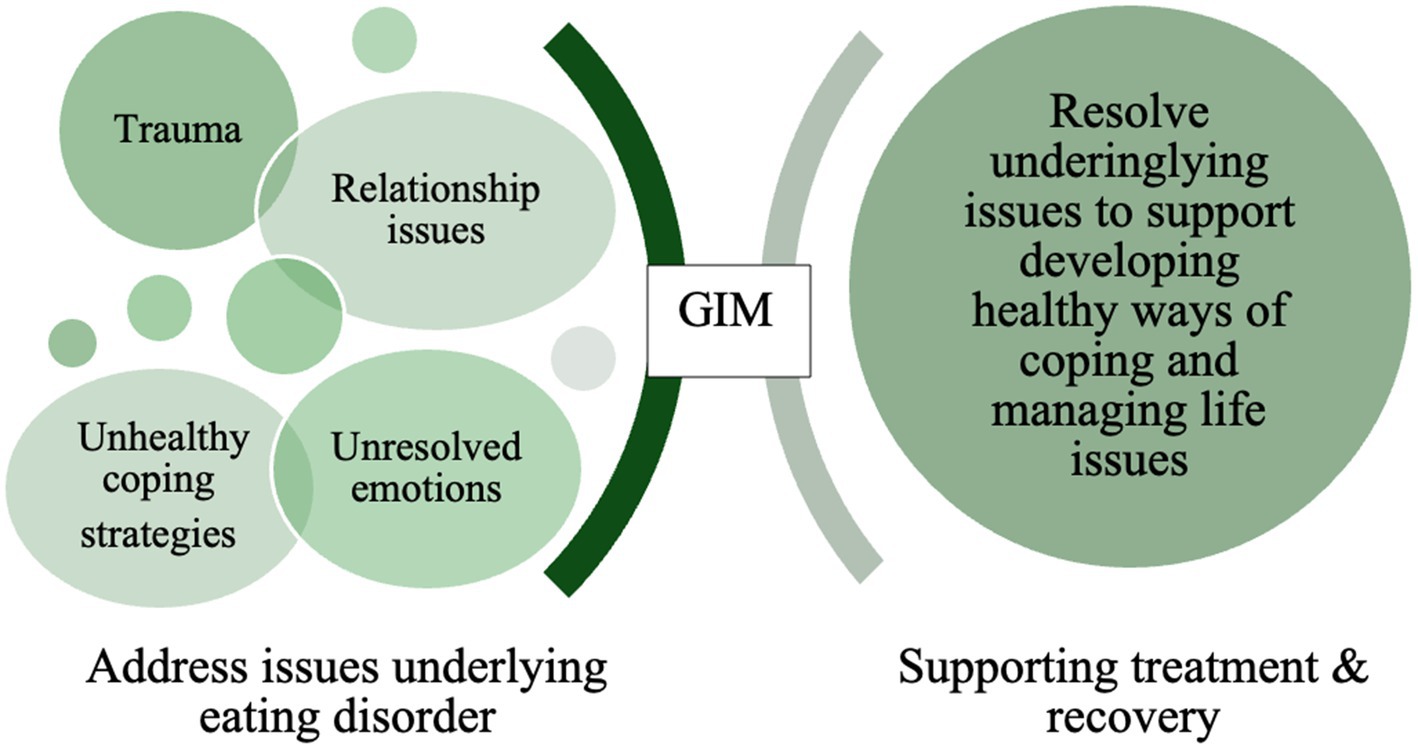

This study is a secondary analysis of a parent study that was the first feasibility study that explored the use of GIM with individuals in ED treatment. The parent study was based on the conceptual framework included in Figure 1, that focuses on addressing issues underlying the ED to support the client in identifying and addressing these issues through a music psychotherapy method (GIM), designed to bring these unresolved issues/emotions into their conscious awareness. Developing awareness of these issues allows individuals access to explore and work through these issues, which helps to support their treatment process and recovery (Heiderscheit, 2017). Primary results from the parent study included participants reporting perceived benefits of engaging in a series of GIM sessions, in which they indicated GIM helped them develop insights related to feeling stuck, their fears, and needing to change. They also reported exploring emotional processes in GIM including identifying, experiencing, and processing their emotions. Additionally, they reported experiencing growth, which included discovering their inner strength, developing a belief in self, and learning to let go of their ED (Heiderscheit, 2023). While participant’s identified perceived benefits of GIM is valuable information for researchers and clinicians, it is also helpful to understand this in tandem with data that explores their therapeutic experiences via analysis of their music and imagery transcripts.

3 Methods

This secondary analysis was based on a descriptive feasibility parent study that explored the integration GIM in ED treatment. The aim of this secondary analysis was to understand participant’s experiences in GIM by identifying imagery themes and exploring the contextual nature of their therapeutic process. The aim for phase one (thematic analysis) was to understand the therapeutic issues that clients address in GIM, while the aim for phase two (intertextual analysis) was to understand these issues within the context of their therapeutic process and ED treatment. Thematic and intertextual methods of analysis were utilized to examine participant’s music and imagery experiences, how they describe their experiences, and to understand these experiences in the context of ED treatment. To explore participant’s experiences, transcripts from each GIM session were analyzed. All GIM sessions were facilitated by a board-certified music therapist (MT-BC), who is also licensed as a marriage and family therapist (LMFT) and certified in the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (GIM fellow).

3.1 Setting and participants

Participants in this study included clients engaged in an ED treatment program in a Midwest metropolitan area. Eligible clients were invited to participate in the study if they were actively engaged in ED treatment (including residential, intensive day treatment, intensive outpatient, and outpatient) and their treatment team determined that GIM was an appropriate therapeutic modality for their treatment process.

Approval for the study was obtained through the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Minnesota. Exclusion criteria included: (a) non-English speaking, (b) medically unstable, and (c) GIM was contraindicated due to dissociative tendencies or dissociation. Informational flyers were posted at the ED treatment program and clients interested in participating in the study needed to obtain approval from their primary therapist to confirm that the treatment team deemed GIM appropriate. After this confirmation, the research assistant met with participants to complete informed consent which specified written consent for the use of quotes from session transcripts and to publish study outcomes. Following the completion of the informed consent, the research assistant scheduled them for their initial session with the MT-BC. Participants continued their regular, which included transitioning to different levels of care when appropriate and necessary. Eight clients were approached to participate in the study, completed informed consent, and received a series of GIM sessions during their ED treatment.

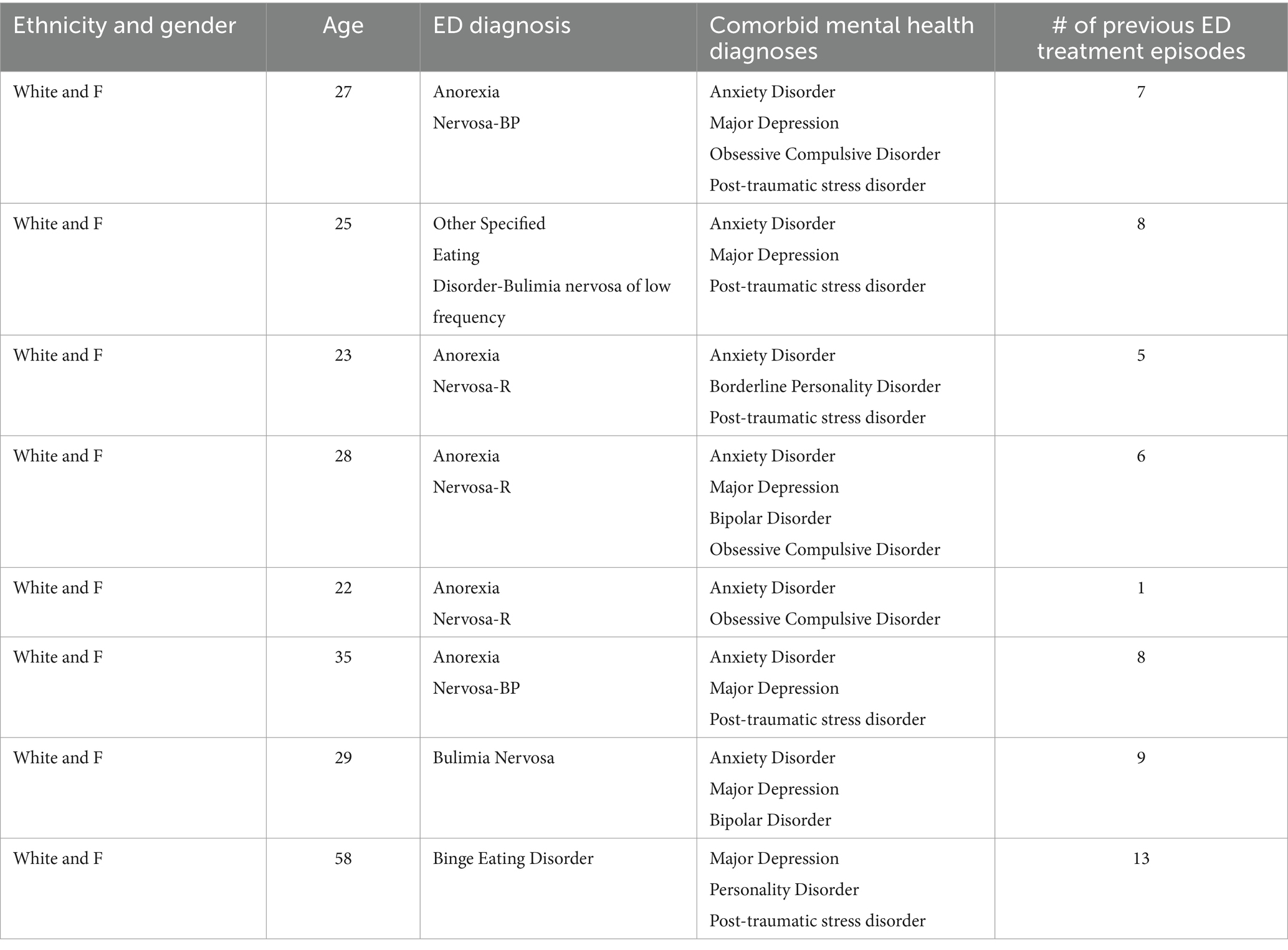

Study participants included eight individuals who identified as female and were between 23 and 58 years of age and a mean age of 35.5 years. Participants had been living with their EDs between 2 and 32 years and for an average of 15 years. They had experienced between 1 and 15 previous ED treatment episodes, with a mean of 8 overall episodes. Their ED diagnoses include AN-Binge Purge (n = 2) Type, AN-Restrictive Type (n = 3), OSFD-BN (n = 1), and BN (n = 1) and BED (n = 1). Table 1 provides participant demographic data including gender, ethnicity, age, ED diagnosis, comorbid mental health diagnoses, and number of previous ED treatment episodes. Participants were also diagnosed with multiple co-morbid mental health diagnoses: 86% with anxiety disorder, 75% with major depression, 63% with post-traumatic stress disorder, 38% with obsessive-compulsive disorder, 25% with borderline personality disorder, and 25% with bipolar disorder.

3.2 Materials

GIM sessions occurred over a 12-month period as participants engaged in ED treatment and transitioned through levels of care. The frequency of GIM sessions was determined based on individual therapeutic needs and pacing appropriate for each participant. This resulted in sessions occurring either weekly or every other week. Sessions were tailored to accommodate a 50-min therapeutic hour due to the schedule and structure of the treatment program. Tailoring sessions for the therapeutic hour required shortening the music portion of sessions when longer programs were selected for use (Heiderscheit, 2015b). Treatment fidelity was maintained by including the following components in each GIM session and tracking these on session transcripts: 10–12 min of check-in and prelude, 25–30 min of music and imaging, and a 10–12-min postlude (Heiderscheit, 2023). All sessions were conducted in a private therapy office with a sofa and recliner to allow participants to choose whether they wanted to lay down or sit in a reclining position during sessions. Pillows and blankets were also available for participants’ comfort. The music utilized was the Music for Imagination® (Bruscia, 1998) and was played from an Apple iPad Mini™ and through a Bose™ Bluetooth speaker.

Each session began with a check-in to allow the MT-BC to gather information, provide an update, and understand how the participant was doing, as well as to be updated about any changes in their life, and discuss any questions or insights from the previous session. This check-in allowed the MT-BC to assess the participant’s needs, including new developments in their treatment process, mood, energy level, as well as insights from previous session(s). This information was integrated with the GIM therapist’s knowledge of the individual’s previous session work to inform clinical decisions about the selection of music to tailor the session. Once the music was selected the participant was invited to lay down or move to a reclining position. The MT-BC then guided the participant through a brief relaxation experience (3–5 min) to shift their attention away from external and distracting thoughts and begin to focus inward. Then a starting image was introduced, which was informed by what the participant shared during the check-in discussion, as well as by their therapeutic work in the previous session. After the brief relaxation experience, music listening began. As the participant listened to the music, they are described aloud what they were imagining. Imagery includes what the participant was seeing, hearing, feeling, sensing, and experiencing. Throughout the process, the MT-BC asked questions to clarify and deepen the participant’s music and imagery experience. As the participant described their experiences, the MT-BC wrote down in a session transcript what they said, as well as the questions asked throughout the process. When the music ended the MT-BC directed the participant to bring their image to a close and guided them to focus their awareness on their breathing and the space around them. Following the music and imagery experience, the MT-BC engaged participants in a discussion identifying significant moments, sharing their feelings and any insights from their experience.

Participants were provided a copy of each session transcript, and the MT-BC maintained a transcript of each session as well. Participants were engaged in their current treatment episode between 12 and 40 weeks for a mean of 25.5 weeks when they began GIM sessions and transitioned to different levels of care as a part of their overall treatment process when necessary. Participants received between 11 and 17 GIM sessions with a mean of 14.5, which resulted in 116 GIM sessions overall. Throughout the study some sessions needed to be rescheduled, and a few sessions were missed due to outside appointments, work or family commitments, illness, and treatment programming changes or outings.

3.3 Data analysis

The review of 116 GIM transcripts was completed independently by two reviewers, including the MT-BC/researcher and an outside reviewer who was an experienced GIM therapist. Duplicates of the session transcripts were provided to the outside reviewer to complete their independent review. Phase one utilized a reflexive thematic analysis approach to embrace the GIM therapist/researcher’s subjectivity as a resource to understanding the client and their therapeutic process (Braun and Clarke, 2023a). This approach acknowledges the interpretive nature of the analysis, so to work on keeping researcher bias in check, coding reliability was implemented with the outside reviewer. The reflexive analysis process included reviewing and coding of all transcripts manually following the six-step process (Braun and Clarke, 2023a, 2023b). Emergent themes were identified based on clients’ words and descriptions of their music and imagery experiences, as well as any explanatory comments they made during prelude and postlude discussions. The inclusion of the prelude and postlude dialogue and comments on the transcripts helped to ensure the themes reflected and remained close to participant’s description of their experiences and informed reviewers’ understanding. This iterative process included clustering and grouping these themes into categories of a similar orientation. These categories were then examined to identifying patterns and points of connection, which led to the development of subordinate themes. Subordinate themes were defined by the reviewers collaboratively and then categorized with related emergent themes. This process helped to ensure the subordinate themes were reflective of participants’ descriptions of their experiences and the reviewers’ interpretation and understanding of their experiences. These themes and subordinate themes were reviewed together by both reviewers. When discrepancies emerged, the reviewers returned to session transcripts and/or discussed their understanding of the theme until they reached mutually agreeable decision. Additionally, study participants reviewed the themes to provide feedback, to ensure the themes and subordinate themes were reflective of their music and imagery experiences. This analytic process is designed to hold close to the experiences of the participants and maintain balance and integrate the reviewers’ understanding of their experience (Braun and Clarke, 2023a, 2023b).

Following the completion of the thematic analysis, phase two included an intertextual analysis. Intertextual analysis is a humanistic and conceptual framework that places the emphasis on understanding and viewing the text with the individual at the center and explores links on different interpretive levels (complexity, ideas, etc.) and considers the macro context of the narrative (Eliezer and Peled, 2023). This process recognizes that the text does not and cannot stand alone as a separate object, rather it is embedded in the context of the client (Eliezer and Peled, 2023; Elkad-Lehman and Greenfeld, 2011; Moseholm and Fetters, 2017). The themes and additional text were explored in the context of understanding the arc of the therapeutic process. This included examining the nine themes, and how they indicate and represent participants’ therapeutic process. Transcript excerpts that represented the nine themes were re-examined and entire transcripts were reviewed again to identify additional excerpts that may be relevant to the intertextual analysis.

4 Results

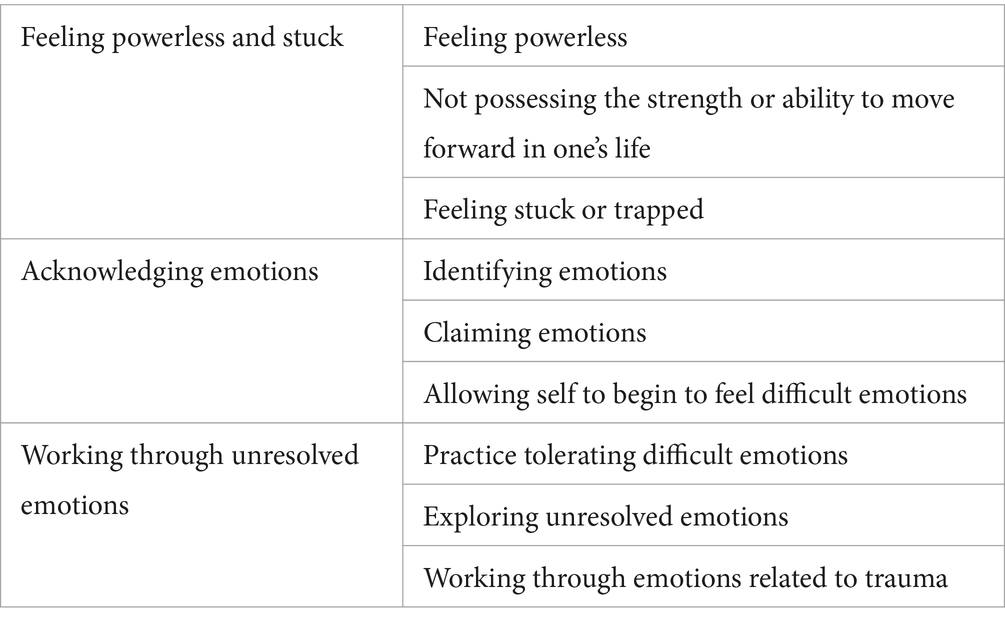

Over the 12-month time frame of the study, 6 sessions were missed, and 8 sessions had to be rescheduled, resulting in 122 sessions, of which 116 were facilitated. Analysis of session transcripts resulted in nine imagery subthemes with three main emergent themes: emotional landscape, relationships, and transformation and growth. Table 2 includes the subthemes of emotional landscape which include: feeling stuck, acknowledging emotions, and working through unresolved emotions. The subthemes indicate participants’ process in navigating aspects of their emotions from feeling stuck in their life to beginning to connect with and learning to express and regulate their emotions, as well as working through difficult and unresolved emotions.

The next theme that emerged focused on relationships. Table 3 describes the various relationships represented in participants’ music and imagery sessions including self, others, and the eating disorder. In each of these subordinate themes, participants explored various aspects of each of these relationships including exploring and working through related challenges. Participants’ imagery also focused on the intersection of these relationships, such as experiencing the impact of their eating disorder on their relationship with self and others.

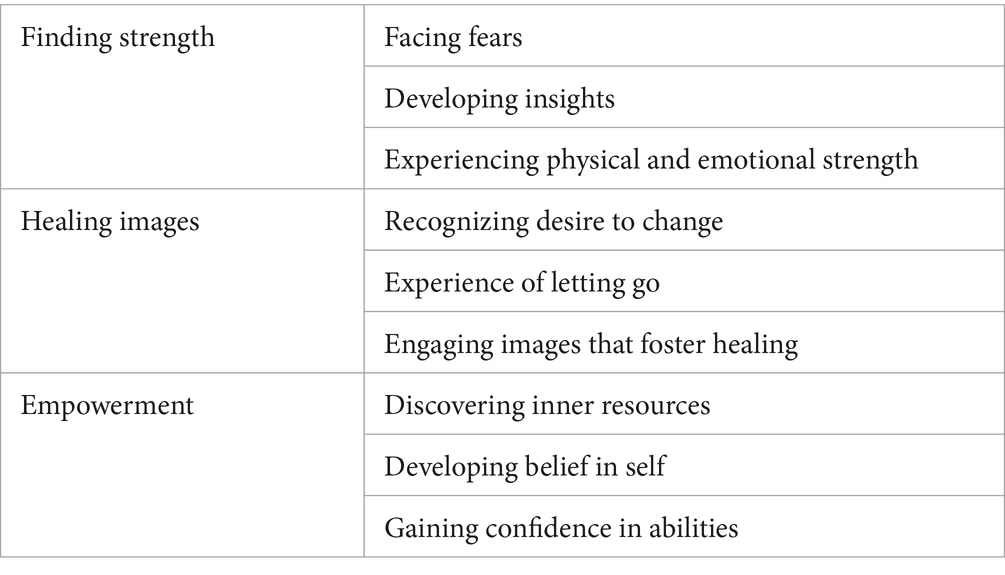

The subthemes of transformation and growth are explicated in Table 4 and include finding strength, change, and empowerment. These represent their process of discovering their strengths as they faced fears, finding a desire to change and to live differently, engaging in a healing process, and building inner resources and self-confidence. These subthemes indicate finding the strength and capacity to confront their fears, make a conscious choice to change, and experience a sense of transformation and growth as a result.

The intertextual analysis of imagery themes illustrates an arc of participants’ therapeutic process. This arc begins with identifying one’s current circumstance of feeling stuck, then the need to work through difficult and unresolved emotions, which transitions to exploring and addressing relationships (self, others, and ED), and then discovering and integrating insights that foster change, growth, transformation, and sense of empowerment. In the process of reviewing these subthemes, what emerged is an arc of a process reminiscent of the Hero’s Journey (Campbell, 1993). These emergent themes were reviewed and compared to the stages of the Hero’s Journey. Table 5 explicates the emergent themes relative to the Hero’s Journey stages, and imagery excerpts that illustrate each. Comments and questions in parentheses in the imagery theme excerpts are statements or questions from the MT-BC during the music and imagery session. These statements and questions are focused on supporting the participants’ music and imagery experience to deepen their exploration, working to engage other senses, or offering encouragement and support.

5 Discussion

The aim of this secondary analysis was to understand participant’s experiences of GIM through a thematic analysis of their imagery and exploring their overall therapeutic process through intertextual analysis. Research to date on the use of GIM with individuals in ED treatment is limited to clinical case studies and a descriptive feasibility study that examined participants perceived benefits and challenges (Heiderscheit, 2015a, 2015b, 2023; Trondalen, 2016a). Comparatively, research on the use of GIM with other client populations has explored how the music supports the imagery experience, fosters different types of imagery, and has examined imagery themes that emerged from a brief series of GIM sessions (Beck, 2015, 2019; Heiderscheit, 2017, 2022; McKinney and Honig, 2017; Honig et al., 2021; Short, 2021; Testa et al., 2020). While this study strives to understand individual’s experiences of GIM, it is limited in scope by the inclusion of eight participants engaged in ED treatment. Therefore, the results are limited as to how they may be generalized more broadly to clients in ED treatment.

5.1 Addressing complexity: a neuroaesthetic process

Participants in this study had complex profiles due to their ED diagnosis, impact of physiological and neurological ED symptoms, multiple co-morbid mental health diagnoses, physical impact of ED trauma, and numerous previous treatment episodes. The imagery themes that emerged indicate that as participants engaged in this series of embodied aesthetic experiences, that fostered a complex interplay allowing them to project their unique and subjective thoughts, feelings, and memories onto the music and imagery. Their engagement in GIM sessions fostered exploration and externalization of their inner experiences they previously struggled to make meaning of and comprehend. In the context of this supportive and aesthetic psychotherapeutic process participants engaged in tolerating, exploring, learning to manage/regulate, and work through difficult emotions that they had avoided or repressed. Participants embodied engagement with their emotions and memories in image form fostered deeper exploration through various sensory modalities integrating interoception, proprioception, and exteroception signals (Vaisvaser et al., 2024).

Through their GIM sessions, participants were able bring these repressed emotions and memories from the subconscious into their conscious awareness, framing them in image form, allowing them to exert control over how long and the ways they engaged with them. This externalization process helped them build and develop their emotional capacity and agility, as well as foster their motivation to address other therapeutic issues and explore other aspects of their life (David, 2017; Patching and Lawler, 2009; Vaisvaser et al., 2024). Building their emotional regulation skills facilitated exploration of intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships. Exploring relationships included experiencing their ED in symbolic form which provided opportunities to distance themselves from their ED, begin to see its destructive nature, and gain awareness and insight into the negative impact of the ED on their body, health, and interpersonal relationships. This symbolization and metaphoric representation of the ED engaged cognitive and emotional processes that served as a pivotal turning point in helping participants understand the severity and impact of their ED (D’Abundo and Chally, 2004; de Witte et al., 2021; Gargaro et al., 2016; Heiderscheit, 2017). Addressing emotionally challenging and underlying issues was a key element in supporting participants’ process of change. This suggests that while an ED is a collection of symptomatology, there are underlying issues impact these symptoms and that need to be addressed (Cockell et al., 2004; Heiderscheit and Madson, 2015; LaMarre and Rice, 2021; Patching and Lawler, 2009; Strober, 2010; Wonderlich et al., 2012). In the GIM sessions participants were able to address underlying issues that helped facilitate transformation and growth. As participants explored images as they unfolded, it helped them reframe and recognize that they could face their fears, discover their strengths, and find their inner resources. The embodied nature of this experiential work in GIM fostered healing images that served as the impetus of change and supported participants decision to work on letting go of the ED. The series of GIM sessions helped participants discover and develop a desire to live their life differently and to see themselves in a new way (Gargaro et al., 2016).

Addressing unresolved and underlying emotions also included working through feelings, memories, and experiences related to childhood and past trauma. A participant shared, “I was so afraid to approach working through my trauma. I found in the GIM sessions that I did not approach my trauma work until I felt I had the resources to do so. It was still uncomfortable, painful, and difficult, and I was able to work through it at my own pace.” (Heiderscheit, 2023, p. 6). The externalization process provided participants the psychological distance to process their trauma in their own way and at their own pace. Additionally, the symbolic and metaphoric nature of the music imagery allowed participants to explore their inner experiences and making meaning of them through engagement with embodied cognitive and affective processes (Vaisvaser et al., 2024). Another participant reported, “I was having a difficult time dealing with the trauma. EMDR, CBT & DBT were somewhat helpful, but I kept getting stuck in the trauma again and again. GIM helped me work through the trauma in my own way, my own time and in a way that allowed me to feel safe.” (Heiderscheit, 2023, p. 6). This indicates their ability to exert psychological control and pace their process in their GIM experiences, fostered their safety throughout the process. Stimulating and engaging the perceptual, cognitive and affective brain functions were key in beginning to explore behavioral and psychological change.

5.2 Process of change and transformation

The intertextual analysis of imagery themes represent a therapeutic arc that indicative of a process of change that is evident in the Hero’s Journey, which is a metaphoric story about a traveler facing challenges on their adventure, which tests, pushes and requires them to learn new skills to emerge from the experience transformed, and empowered to bring what they have discovered into their life (Campbell, 1993; Williams, 2016, 2017). The Hero’s Journey is utilized to create an arc in a story, and it is also representative of transformation and change which is reminiscent of the therapeutic process (Campbell, 1993; Vogler, 2020).

When the nine imagery themes that emerged from the thematic analysis were analyzed in the context of participants therapeutic process (intertextual analysis), it became evident that they follow the arc of the stages of the Hero’s Journey. Evidence of this mythic journey being represented in their series of GIM sessions, suggests participants engagement with a shred symbolism and metaphor across the arc of their therapeutic process, as well as the engagement cognitive and affective processes that supports a client’s transformation (Coutinho Cortes et al., 2024; Vaisvaser et al., 2024). Transformation in the therapeutic process aligns with the Hero’s Journey in which the hero is transformed after overcoming challenges through determination of developing awareness, new insights, and skills (Williams, 2016, 2017). The findings from this intertextual analysis and metaphoric representation of the Hero’s Journey has appeared in the imagery in the GIM process with patients facing other mental health and medical crises (Heiderscheit, 2022; Short et al., 2011). The representation of Hero’s Journey across psychological and physical health journeys, indicates both present struggles and challenges for an individual to work through to experience transformation and change.

5.3 Implications of the study

These findings along with previous research indicate that whether an individual is facing physical health crises, mental health issues, or a combination, there is a similar process of self-exploration and discovery that is key to foster healing and recovery as a part of one’s health journey (Heiderscheit et al., 2022). Given EDs include psychological and physical health issues, GIM offers a wholistic psychotherapeutic approach treatment to address individual’s complex needs. Engaging individuals diagnosed with an ED an aesthetic, supportive psychotherapy process is key to accessing perceptual, cognitive, and affective brain functions which are vital to their treatment and recovery (Vaisvaser et al., 2024). Further, the process of discovering and reclaiming their inner resources allowed participants to gain a sense of mastery and self-efficacy which helped them to build a sense of internal safety and empowerment to make healthy choices and decisions for their life through a short series of between 11 and 17 GIM sessions (Heiderscheit, 2023; Malchiodi, 2018; Ogden et al., 2006; Short et al., 2011; van der Kolk, 2014).

6 Conclusion

EDs are complex and have multiple factors that influence their development, as well as a myriad of mental and physical comorbidities that impact and complicate the treatment and recovery process. ED treatment needs to integrate a wholistic approach that is tailored to the ED symptomology, the unique context of the individual, and holds the capacity to access the subconscious to address underlying issues. A focus on engaging clients in identifying and working through these issues in experiential and embodied ways integrates neurobiological and psychological process that fosters meaning making, mastery, and empowerment (Kaufman, 2022; Coutinho Cortes et al., 2024; van der Kolk, 2014; Vaisvaser et al., 2024). While empirically based and manualized treatment ED approaches have been most researched, the body of evidence exploring and examining the use of CATs in ED treatment is growing (Agras and Robinson, 2018; Testa et al., 2020; Heiderscheit, 2023). Further exploration of embodied aesthetic approaches is needed to expand the neuroscientific understanding of the process with individuals in ED treatment.

Valuing and integrating the lived experiences and wisdom of client’s, provides the opportunity to inform and tailor experiential methods and approaches for ED treatment (Guarda et al., 2018; Lotter and van Staden, 2022; Silber et al., 2011). Further, understanding client’s experiences in GIM provides insight into areas of therapeutic change which helps to inform the choice of outcome measures for future research. Additionally, recommendations for future research include the integration mobile brain imaging (MoBI) data to gain insight into neurodynamic engagement and therapeutic interactions across a series of sessions. Future research could also focus on implementing outcome-based research targeted and addressing the unique needs of different ED diagnoses. Indepth aesthetic and experiential methods like GIM engage clients in a therapeutic process that fosters their discovery, paced to meet their unique needs, and engaging them in meaning making experiences that support their treatment and recovery. Finally, the body of existing evidence can be used to inform implementing more rigorous research exploring the use of the CATs with clients in ED treatment.

The high economic costs of ED treatment and disease burden of EDs indicate an urgency to reduce their impact and identify effective treatment protocols (Streatfeild et al., 2021). ED treatment programs integrate CATS and experiential modalities into their regular programming to provide clients and their families with an integrative approach to treatment and recovery. Individuals trained and credentialed in the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (GIM) can provide individual or group sessions to support clients in addressing the issues underlying the ED and discovering and developing strengths needed for recovery. A holistic approach to ED treatment can address the complex needs of clients and may hold the potential to reduce recidivism and decrease overall costs of treatment.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because datasets include full session guided imagery and music transcripts. Clients did not consent for full session transcripts to be shared. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to QW5uaWUuSGVpZGVyc2NoZWl0QGFydS5hYy51aw==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Minnesota Institution Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the clients for their participation in the study and the colleagues at The Emily Program that supported this research project.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbate-Daga, G., Buzzichelli, S., Marzola, E., Amianto, F., and Fassino, S. (2014). Clinical investigation of set-sifting sub-types in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 219, 592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.024

Agras,, and Robinson,. (2018). The Oxford handbook of eating disorders. 2nd Edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ahonen, H. (2019). “Putting the lights on in the room: guided imagery and music (GIM) with trauma survivors” in Guided Imagery & Music (GIM) and music imagery methods for individuals and group therapy. eds. D. Grocke and T. Moe (Dallas, Texas: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 131–140.

American Psychological Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th Edn. Washington, D. C.: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anderson-Fye, A. (2018). “Appetitive regulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 187–208.

Backholm, K. I., Isomaa, R., and Birgegård, A. (2013). The prevalence and impact of trauma history in eating disorder patients. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 4:22482. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.22482

Barmore, L. (2017). The Bonny method of guided imagery and music (GIM) and eating disorders: learning from therapist, trainer, and client experiences. Master’s Thesis. Boone, North Carolina: Appalachian State University.

Beat Eating Disorders (2021). How many people of eating disorders in the UK. Available at: https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/ (Accessed April 8, 2024).

Beck, B. (2015). “Guided imagery and music with clients on stress leave” in Guided Imagery & Music (GIM) and music imagery methods for individual and group therapy. eds. D. Grocke and T. Moe (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 131–140.

Beck, B. (2019). “Guided imagery and music in mental illness and mental health conditions” in Guided imagery and music: the Bonny method and beyond, (2nd edition). ed. D. Grocke (Dallas, Texas: Barcelona Publishers), 131–147.

Beck, B. M., Messel, C., Meyer, S. L., Cordtz, T. O., Søgaard, U., Simonsen, E., et al. (2018). Feasibility of trauma focused guided imagery and music with adult refugees diagnosed with PTSD: a pilot study. Nord. J. Music. Ther. 27, 67–86. doi: 10.1080/08098131.2017.1286368

Biffl, W., Narayanan, V., Gaudiani, J., and Mehler, P. (2010). The management of pneumothorax in patients with anorexia nervosa. Patient Safety Survey 4, 1–4. doi: 10.1186/1754-9493-4-1

Bonny, H. (1994). Twenty-one years later: a GIM update. Music. Ther. Perspect. 12, 70–74. doi: 10.1093/mtp/12.2.70

Bonny, H., and Savary, L. (1990). Music and your mind: listening with a new consciousness. Dallas, Texas.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2023a). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 24, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

Braun, D., Sunday, S., and Halmi, K. (1994). Psychiatric comorbidity in patients with eating disorders. Psychol. Med. 24, 859–867. doi: 10.1017/S003329170028956

Brewerton, T. (2019). An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 28, 445–462. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940

Bulik, C., Klump, K., Thornton, L., Kaplan, A., Devlin, B. F., Fichter, M. M., et al. (2004). Alcohol abuse disorder comorbidity in eating disorders: a multicenter study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65, 1000–1006. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0718

Burke, N., Karam, A., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., and Wilfley, D. (2018). “Interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders. eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson. 2nd ed (New York: Oxford University Press), 287–318.

Campbell, J. (1993). The hero with a thousand faces. 3rd Edn. Novato, California: New World Library.

Carlèn, M. (2017). What constitutes the prefrontal cortex? Science 358, 478–482. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8868

Celeghin, A., Palermo, S., Di Giampaolo, R., Fini, G., Gandino, G., and Civilotti, C. (2023). Brain correlates of eating disorders in response to food visual stimuli: a systematic narrative review of FMRI studies. Brain Sci. 13, 1–39. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13030465

Chen, E., Yiu, A., and Safer, D. (2018). “Dialectical behavior therapy and emotion-focused therapies for eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders. eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson. 2nd ed (New York: Oxford University Press), 334–350.

Clark, M., and Keiser, L. (1986). Guided imagery and music. Rockville, Maryland: Institute for Music and Imagery.

Cockell, S., Zaitsoff, S., and Geller, J. (2004). Maintaining change following eating disorder treatment. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 35, 527–534. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.35.5.527

Costello, E., and Angold, A. (1995). “Epidemiology” in Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. ed. S. March (New York: Guilford Press), 1–124.

Coutinho Cortes, B., Pariz, C., Krahe, T., and Mograbi, C. (2024). Are you how you eat? Aspects of self-awareness in eating disorders. Pers. Neurosci. 7, 1–12. doi: 10.1017/pen.2024.2

D’Abundo, M., and Chally, P. (2004). Struggling with recovery: participants perspectives on battling an eating disorder. Qual. Health Res. 14, 1094–1106. doi: 10.1177/1049732304267753

David, S. (2017). Emotional agility: get unstuck, embrace change and thrive in work and life. London: Penguin.

de Witte, M., Orkibi, H., Zarate, R., Karkou, V., Sajnani, N., Malhotra, B., et al. (2021). From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: a scoping review. Front. Psychol. 12:678397. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397

Dyer, K., and Corrigan, J. (2021). Psychological treatments for complex PTSD: a commentary on the clinical and empirical impasse dividing unimodal and phase-oriented therapy positions. Psychol Trauma 13, 869–876. doi: 10.1037/tra0001080

Eliezer, K., and Peled, E. (2023). Intertextual psychoanalytic-intersubjective analysis in qualitative research: ‘can two walk together, except they agreed?’. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 26, 425–437. doi: 10.1080/113645579.2021.2011118

Elkad-Lehman, I., and Greenfeld, H. (2011). Intertextuality as an interpretative method in qualitative research. Narrat. Inq. 21, 258–275. doi: 10.1075/ni.21.2.05elk

Ely, A., and Kaye, W. (2018). “Appetite regulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 47–79.

Fairburn, C., Cooper, Z., Dell, H., and Welch, S. (1999). Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: three integrated case-control comparison. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56, 468–476. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.468

Faje, A., Fazeli, P., Miller, K., Katzman, D., Ebrahimi, S., Lee, H., et al. (2014). Fracture risk and areal bone mineral density in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 49, 249–259. doi: 10.1002/eat.22248

Favaro, A., Ferrara, S., and Santanastaso, P. (2003). The spectrum of eating disorders in young women: a prevalence study in a general population. Psychosom. Med. 65, 701–708. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000073871.67679.D8

Gargaro, E., Guertin, R., and Heiderscheit, A. (2016). “Client perspectives on the use of the creative arts in eating disorder treatment” in Creative arts therapies in eating disorder treatment. ed. A. Heiderscheit (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 27–48.

Goldberg, F. (1995). “The Bonny method of guided imagery and music” in The art and science of music therapy: A handbook. eds. T. Wigram, B. Saperston, and R. West (Reading, United Kingdom: Harwood Academic Publishers), 112–128.

Goldberg, F. (2019). “A holographic field theory model of the Bonny method of guided imagery and music (GIM): a psychospiritual approach” in Guided imagery and music: The Bonny method and beyond. ed. D. Grocke. 2nd ed (Dallas, Texas: Barcelona Publishers), 83–496.

Grocke, D. (2019). Guided imagery and music: the Bonny method and beyond. 2nd Edn. Dallas Texas: Barcelona Publishers.

Guarda, A., Wonderlich, S., Kaye, W., and Attia, E. (2018). A path to defining excellence in intensive treatment for eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 51, 1051–1055. doi: 10.1002/eat.22899

Halmi, K. (2018). “Psychological comorbidities of eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 229–243.

Halmi, K., Sunday, S., Strober, M., Kaplan, A., Woodside, D., Fichter, M., et al. (2000). Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa: variation by clinical subtype, obsessionality, and pathological eating behavior. Am. J. Psychiatry 1157, 1799–1805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1799

Heiderscheit, A. (2008). “Discovery and recovery through music: an overview of music therapy in eating disorder treatment” in The creative arts therapies and eating disorders. ed. S. Brooke (Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publisher), 122–141.

Heiderscheit, A. (2013). “GIM: deprivation and its contribution to pain in eating disorders” in Music and medicine: integrative models in the treatment of pain. eds. J. Mondanaro and G. Sara (New York: Satchnote Press), 147–171.

Heiderscheit, A. (2015a). Creative arts therapies in eating disorder treatment. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Heiderscheit, A. (2015b). “GIM in the therapeutic hour and case illustration of an adult client in eating disorder treatment” in Guided imagery and music (GIM) and imagery methods for individual and group therapy. eds. D. Grocke and T. Moe (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 99–107.

Heiderscheit, A. (2016a). Creative arts therapies with clients in eating disorder treatment. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Heiderscheit, A. (2016b). “The use of the creative arts therapies in eating disorder treatment” in Creative arts therapies in eating disorder treatment. ed. A. Heiderscheit (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 9–26.

Heiderscheit, A. (2017). The effects of the Bonny method of guided imagery and music (GIM) on interpersonal problems, sense of coherence, and salivary immunoglobulin a of adults in chemical dependency treatment. Music Med. 9, 24–36. doi: 10.47513/mmd.v9i1.521

Heiderscheit, A. (2022). Analysis of type of imagery and imagery themes from Bonny method of guided imagery and music (GIM) sessions with adults in chemical dependency treatment. Arts Psychother. 80, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2022.101933

Heiderscheit, A. (2023). Feasibility of the Bonny method of guided imagery and music in eating disorder treatment: clients perceived benefits and challenges. Arts Psychother. 86, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aip/2023/102086

Heiderscheit, A., and Madson, A. (2015). Use of the iso principle as a central method in mood management: a music psychotherapy clinical case study. Music. Ther. Perspect. 33, 45–52. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miu042

Heiderscheit, A., and Murphy, K. (2021). Trauma-informed care in music therapy: principles, guidelines and a clinical case illustration. Music. Ther. Perspect. 39, 142–151. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miab011

Heiderscheit, A., Young, L., Trondalen, G., and Short, A. (2022). GIM: Unexpected integrative connection between emotion and physical health (conference presentation). 12th European music therapy conference, Edinburgh, UK.

Herzog, D., Keller, M., Lavori, P., Kenny, G., and Sak, S. (1992). The prevalence of personality disorders in 210 women with eating disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 53, 147–152. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199209000-00006

Hester, R., and Sheehy, N. (1990). “The grand unification theory of alcohol abuse: it’s time to stop fighting each other and start working together” in Controversies in the addictions field. ed. R. Engs, vol. 1 (Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt), 2–9.

Honig, T., McKinney, C., and Hannibal, N. (2021). The Bonny method of guided imagery and music (GIM) in the treatment of depression: a multi-site randomized controlled trial. J. Assoc. Music Imagery 18, 27–54.

Hott, M., Horikawa, R., Mabe, H., Yokoyama, S., Sugiyama, E., Yonekawa, T., et al. (2015). Epidemiology of anorexia nervosa in Japanese adolescents. Biopsychical Med. 14:17. doi: 10.1186/s13030-015-0044-2

Hudson, J., Hiripi, E., Pope, H., and Kessler, R. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 61, 348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

Imus, S. (2021). “Creating breeds creating” in Dance and creativity within dance movement therapy: international perspectives (pp. 124–140). eds. H. Wengower and S. Chaiklin (New York: Routledge).

Jacobi, C., Hutter, K., and Fittig, E. (2018). “Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders. eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson. 2nd ed (New York: Oxford University Press), 106–125.

Jacobsen, T. (2006). Bridging the arts and sciences: a framework for the psychology of aesthetics. Leonardo 39, 155–162. doi: 10.1162/leon.2006.39.2.155

Kaplan, A., and Nobel, S. (2018). “Medical complication of eating disorders” in Annual review of eating disorders – Part I. eds. S. Wonderlich, J. Mitchell, L. Boath, H. Steiger, and S. Crow (Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press), 101–114.

Kaye, W., Bulik, C., Thorton, L., Barbarich, N., and Master, K. (2004). Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 2215–2221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215

Keel, P. (2018). “Epidemiology and course of eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 34–46.

Keel, P., and Brown, T. (2010). Update on course and outcome in eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 43, 195–204. doi: 10.1002/eat.20810

Kennett, Y. N., Humphries, S., and Chatterjee, A. (2023). A thirst for knowledge: grounding curiosity, creativity, and aesthetics in memory and reward neural systems. Creat. Res. J. 35, 412–426. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2023.2165748

Keski-Rahkonen, A., Hoek, H. W., Susser, E. S., Linna, M. S., Sihvola, E., Raevuori, A., et al. (2007). Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 1259–1265. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081388

Kirsch, L., Urgesi, C., and Cross, E. (2016). Shaping and re- shaping the aesthetic brain: emerging perspectives on the neurobiology of embodied aesthetics. Neurosci. Bio Behav. Rev. 62, 56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.12.005

Kraeft, J., Uppot, R., and Heffess, A. (2013). Imaging findings in anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Roentgenol. 200, 328–334. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9641

Kushnir, A., and Orkibi, H. (2021). Concretization as a mechanism of change in psychodrama: procedures and benefits. Front. Psychol. 12:633069. doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2021.633069

LaMarre, A., and Rice, C. (2021). Recovering uncertainty: exploring eating recovery in context. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 45, 706–726. doi: 10.1007/s11013-020-09700-7

Lamzabi, I., Syed, S., Reddy, V., Jain, R., Harbhanjanka, A., and Arunkumar, P. (2015). Myocardial changes in a patient with anorexia nervosa: a case report and review of literature. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 143, 734–737. doi: 10.1309/AJCP4PLFF1TTKENT

Le Grange, D., and Eisler, I. (2009). Family interventions in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Child Adolescent Psychiatric Clin. North America 18, 159–173. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.07.004

Le Grange, D., and Rienecke, R. (2018). “Family therapy for eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 319–333.

Le Lock, J., Grange, D., Agras, W., and Dare, C. (2001). Treatment manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford.

Lester, R. (2019). Famished: Eating disorders and failed care in America. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

Levinson, C., Hunt, R., Keshishian, A., Brown, M., Vanzhula, I., Christian, C., et al. (2021). Using individual networks to identify treatment targets for eating disorder treatment: a proof-0f-concept study and initial data. J. Eat. Disord. 9:147. doi: 10.1186/s40337-021-00504-7

Lotter, C., and van Staden, W. (2022). Patient’s voices from music therapy at a South African psychiatric hospital. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 28:a1884. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v.2810.1884

Malchiodi, C. (2018). Trauma and expressive arts therapies: brain, body, & imagination in the healing process. New York: Guilford Press.

Manning, E., and Gagnon, M. (2017). The complex patient: a concept clarification. Nurs. Health Sci. 19, 13–21. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12320

Martin, C., and Felix-Bortolotti, M. (2010). W(h)ither complexity? The emperor’s new toolkit? Or elucidating the evolution of healthcare systems knowledge? J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 16, 416–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01461.x

Mascolo, M., Dee, E., Townsend, R., Brinton, J., and Mehler, P. (2015). Severe gastric dilation due to superior mesenteric artery syndrome in anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 48, 532–540. doi: 10.1002/eat.22385

McFerran, K., and Heiderscheit, A. (2015). “A multi-theoretical approach for music therapy in disorder treatment” in Creative arts therapies in eating disorder treatment. ed. A. Heiderscheit (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 49–70.

McKinney, C., and Honig, T. (2017). Health outcomes of a series of Bonny method of guided imagery and music sessions. A systematic review. J. Music. Ther. 54, 1–34. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thw016

McNeece, C., and DiNitto, D. (2011). Chemical dependency: a systems approach. 4th Edn. London: Pearson Publishers.

Mehler, P. (2018). “Medical complications of anorexia and bulimia nervosa” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 222–228.

Miller, K., Grinspoon, S., and Gleysreen, S. (2004). Preservation of neuroendocrine control of reproductive function despite under nutrition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism 89, 4434–4438. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0720

Moseholm, E., and Fetters, M. (2017). Conceptual models to guide integration during analysis in convergent mixed methods studies. Methodol. Innov. 10, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/2059799117703118

Noer,. (2015). “Breathing space in music: guided imagery and music for adolescents with eating disordersin a family-focused program” in Guided Imagery & Music (GIM) and music imagery methods for individual and group therapy. eds. D. Grocke and T. Moe (New York: Jessica Kingsley), 73–86.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., and Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: a sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York: Norton.

Papanikolaou,. (2015). “Short guided imagery and music (GIM) session in the treatment of adolescents with eating disorders” in Guided Imagery & Music (GIM) and music imagery methods for individual and group therapy. eds. D. Grocke and T. Moe (New York: Jessica Kingsley), 63–72.

Patching, J., and Lawler, J. (2009). Understanding women’s experiences of developing an eating disorder and recovering: a life history approach. Nurs. Inq. 16, 10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2009.00436.x

Pickett, E. (1991). “Guided imagery and music (GIM) with a dually diagnosed woman with multiple addictions” in Cases studies in music therapy. ed. K. Bruscia (Dallas, Texas: Barcelona Publishers), 497–512.

Rikani, A., Choudhry, Z., Choudhry, A., Ikram, H., Asghar, M., Kajal, D., et al. (2013). A critique of the literature on etiology of eating disorders. Ann. Neurosci. 20, 157–161. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.200409

Roberto, C., Mayer, L., Brickman, A., Barnes, A., Muraskin, J., Yeung, L., et al. (2011). Brain tissue volume changes following weight gain in anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 44, 406–410. doi: 10.1002/eat.20840

Sabel, A., Gaudiani, J., Statland, B., and Mehler, P. (2013). Hematological abnormalities in severe anorexia nervosa. Ann. Hematol. 92, 605–613. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1672-x

Salvato, G., Richter, F., Sedeño, L., Bottini, G., and Paulesu, E. (2019). Building the bodily self-awareness: evidence for the convergence between interoceptive and exteroceptive information in a multilevel kernel density analysis study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 401–418. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24810

Short, A. (2021). Sounding the changes: clients report on GIM music used in cardiac rehabilitation. Arts Psychotherapy 76, 3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2021.101852

Short, A., Gibb, H., and Holmes, C. (2011). Integrating words, images and text in BMGIM: finding connections through semiotic intertextuality. Nord. J. Music. Ther. 20, 3–21. doi: 10.1080/08098131003764031

Silber, T., Lyster-Mensh, L., and Duval, J. (2011). Anorexia nervosa: patient and family centered care. Pediatr. Nurs. 37, 331–333

Smink, F., van Hoeken, D., and Hoek, H. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: incident, prevalence, mortality rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 14, 406–414. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

Steinhausen, H., and Jensen, C. (2015). Time trends in life-time incidence rates of first-time diagnosed anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa 16 years in a Danish nationwide psychiatric registry study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 48, 845–850. doi: 10.1002/eat.22402

Steward, W., and Robinson, A. (2018). The Oxford handbook of eating disorders. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stice, E., and Shaw, H. (2018). “Dieting and the eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 126–154.

Streatfeild, J., Hickson, J., Austin, S., Hutcheson, R., Kandel, J., Lampert, J., et al. (2021). Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States: evidence to inform policy action. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 54, 851–868. doi: 10.1002/eat.23486

STRIPED Harvard (2020). Report: economic costs of eating disorders. Available at: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/striped/report-economic-costs-of-eating-disorders/ (Accessed April 28, 2024).

Strober, M. (2010). “The chronically ill patient with anorexia nervosa” in The treatment of eating disorders. eds. C. Grilo and J. Mitchell (New York: Guilford Press), 225–237.

Tagay, S., Schlottbohm, E., Reyes-Rodriguez, M., Repic, N., and Senf, W. (2014). Eating disorders, trauma, PTSD, and psychological resources. J. Treatment Preven. 22, 33–49. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.857517

Testa, F., Arunachalam, S., Heiderscheit, A., and Himmerich, H. (2020). A systematic review of scientific studies on the effects of music in people with or at-risk for eating disorders. Psychiatr. Danub. 32, 334–345. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2020.334

Trondalen, G. (2011). “Music is about feelings: music therapy with a young man suffering from anorexia nervosa” in Developments in music therapy practice: case examples. ed. T. Meadows (Dallas, Texas: Barcelona Publishers), 434–452.

Trondalen, G. (2016a). “Expressive and receptive music therapy in eating disorder treatment” in Creative arts therapies in eating disorder treatment. ed. A. Heiderscheit (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 99–119.

Trondalen, G. (2016b). “The future of music therapy for persons with eating disorders” in Envisioning the future of music therapy. ed. C. Dileo (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press), 31–44.

Vaisvaser, S. (2021). The embodied-enactive-interactive brain: bridging neuroscience and creative arts therapies. Front. Psychol. 12:634079. doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2021.634079

Vaisvaser, S., King, J., Orkibi, H., and Aleem, H. (2024). Neurodynamics of relational aesthetic engagement in creative arts therapies. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 28, 203–218. doi: 10.1177/10892680241260840

Vögele, C., Lutz, A., and Leigh Gibson, E. (2018). “Mood, emotions, and eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 155–186.

Vogler, C. (2020). The writer's journey: Mythic structure for writers. 25th Anniversary Edn. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions.

Wade, T., Bergin, J., Tiggeman, M., Bulik, C., and Fairburn, C. (2006). Prevalence and long-term course of lifetime eating disorders in an adult Australian twin cohort. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 40, 121–128. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01758.x

Wade, T., and Bulik, C. (2018). “Genetic influences on eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders (2nd edition). eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson (New York: Oxford University Press), 80–105.

Westermoreland, P., Krantz, M., and Mehler, P. (2016). Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Am. J. Med. 129, 30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.06.031

Williams, C. (2016). A mudmap for living: a practical guide to daily living based on Joseph Campbell’s the hero’s journey. Available at: http://amudmapforliving.com.au/.

Williams, C. (2017). The hero’s journey: a Mudmap for change. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1–18. doi: 10.1177/0022167817705499journals.sagepub.com/home/jhp

Wilson, G. (2018). “Cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders” in The Oxford handbook of eating disorders. eds. W. Agras and A. Robinson. 2nd ed (New York: Oxford University Press), 271–286.

Wonderlich, J., Bershad, M., and Steinglass, J. (2021). Exploring neural mechanisms related to cognitive control, reward, and affect in eating disorders: a narrative review of FMRI studies. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 17, 2053–2062. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S282554

Wonderlich, S., Mitchell, J., Crosby, R., Myers, T., Kaldec, K., LaHaise, K., et al. (2012). Minimizing and treating chronicity in the eating disorders: a clinical review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 45, 467–475. doi: 10.1002/eat.20978

Keywords: GIM, music therapy, eating disorders, imagery themes, neuroaesthetics

Citation: Heiderscheit A (2024) Thematic and intertextual analysis from a feasibility study of the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music with clients in eating disorder treatment. Front. Psychol. 15:1456033. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1456033

Edited by:

Rebecca Bokoch, Alliant International University-San Diego, United StatesReviewed by:

Varvara Pasiali, Queens University of Charlotte, United StatesKimberly Sena Moore, University of Miami, United States

Copyright © 2024 Heiderscheit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Annie Heiderscheit, QW5uaWUuSGVpZGVyc2NoZWl0QGFydS5hYy51aw==

Annie Heiderscheit

Annie Heiderscheit