94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 29 July 2024

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1421412

Despite the recent proliferation of scholarly investigations on servant leadership, clarity remains elusive regarding the specific mechanisms and conditions underpinning employee cognitive processes and their responses to servant leadership. Drawing upon social cognitive theory, proposes a moderated mediation model tested through a time-lagged field data from 489 employees in Study 1 and an experimental data in Study 2. We found that servant leadership indirectly enhances employee voice behavior through increased employee work reflection. Additionally, we considered employee proactive personality as a boundary condition for the positive effect of servant leadership. Our results show that servant leadership prompts employee work reflection only when the level of employee proactive personality is high, which in turn increases employee voice behavior. This study presents significant theoretical and practical implications through the integration of social cognitive theory with servant leadership research.

As organizational environments become more diverse, complex, and dynamic, the importance of upward information flow and multi-source perspectives within organizations has become increasingly vital for effective decision-making and overall organizational health (Morrison and Milliken, 2000; Li and Tangirala, 2022). In this context, employees’ value to enterprises extends beyond their labor contributions to include their ability to generate innovative ideas and viewpoints (Morrison, 2011; Welsh et al., 2022). Consequently, employee voice, defined as the expression of work-related opinions, ideas, and concerns driven by cooperative motivation, has become increasingly important for organizational success (Morrison, 2014; Parke et al., 2022).

However, employees often perceive voicing their opinions as risky (Dutton et al., 1997; Zhao et al., 2023). Publicly expressing views on work-related issues can disrupt organizational harmony and challenge leadership authority (Milliken et al., 2003). This can not only fail to influence management decisions but also potentially have negative repercussions for career development (Parke et al., 2022). Given the importance of employee voice and the ambivalence felt by employees when expressing their opinions, the role of leadership in influencing voice behavior has become a central focus of research (Jiang et al., 2022; Thompson and Klotz, 2022). In particular, servant leadership, characterized by service, altruism, and empowerment (Kauppila et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023), has garnered significant attention from researchers for its potential to promote employee voice behavior (Greenleaf, 1977; Liden et al., 2014). Central to this leadership style is its focus on understanding and fulfilling the individual needs of employees, appreciating their unique values, and fostering their participation in servant behaviors (Greenleaf, 1970). The direct encouragement of voice behavior underlines the unique position of servant leadership in enhancing open communication and driving innovative changes within organizations (Detert and Treviño, 2010; Arain et al., 2019; Liao et al., 2021; Hartnell et al., 2023). Prior research has demonstrated that servant leadership is favorably correlated with followers’ positive extra-role behaviors (Ehrhart, 2004; Lapointe and Vandenberche, 2015; Sun et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2021).

Although it is anticipated that servant leadership will boost employees’ voice behavior by providing a work atmosphere that is relationally friendly, employees engage in complex cognitive processes before deciding to voice their opinions (Bandura, 1986, 1991). These cognitive processes reflect employees’ evaluation of the potential positive and negative outcomes of their voice behavior (Yang et al., 2022). Existing research seldom investigates the mechanisms and conditions under which humble leadership influences voice behavior through cognitive processes (Ong et al., 2023). According to social cognitive theory (SCT), the self-regulatory function is performed by self-evaluative reactions resulting from an individual’s self-cognitive capability and established internal standards. These, in turn, serve to influence both cognition and action (Bandura, 1986, 1991). As a core mechanism of regulation and key predictor of employee behavior (Schippers et al., 2015), employee work reflection has received considerable attention. Employee work reflection refers to the voluntary involvement of an individual in a series of cognitive processes, wherein they contemplate and analyze many aspects that constitute their work and influence their capacity to get favorable work results (Ong et al., 2023). Even though various cognitive factors may impact the consequence of servant leadership, individual work reflection may be the most significant core mechanism and key predictor of leadership effectiveness (Li et al., 2020; Lanaj et al., 2023; Ong et al., 2023). Specifically, employee work reflection is intimately connected to the core attributes of servant leadership: This environment of trust and collaboration, characterized by an emphasis on listening, empathy, and stewardship, is essential, as it brings employee reflection to the fore (Walumbwa et al., 2010). Employee reflection arises from the support and psychological safety provided by the external environment. In addition, servant leadership embodies the management philosophy of being “employee-centered” and shows a high degree of interpersonal acceptance and willingness to serve (Greenleaf, 1977; Liden et al., 2014). This bottom-up leadership approach enhances the employees’ sense of belonging and pride in the organization, which helps them to minimize the risks associated with voice behavior through reflective thinking (Leblanc et al., 2022).

Yet, the effectiveness of servant leadership in influencing individual employee behavior remains uncertain, as these complex cognitive processes can be significantly affected by individual differences. Previous research suggests that employees with a proactive personality, characterized by high self-efficacy and resilience, are more likely to exhibit increased motivation. In contrast, employees with less proactive personalities may not experience the same perceptions (Li et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021). As a result, servant leadership may only materialize into employee work reflection and ultimately employee voice behavior under certain conditions. In SCT, “triadic reciprocity” highlights the interactivity of individual traits with which the organizational environment influences individual cognition and behavior (Bandura, 1986). Specifically, we argue that the effectiveness of servant leadership can vary greatly depending on employee proactive personality. Proactive personality is defined as an individual’s behavioral inclination to proactively adapt to the external environment and to positively change the situation (Crant and Bateman, 2000). Given that an employee with a highly proactive personality is able to make full use of their subjective initiative, they are inclined to exhibit heightened attentiveness toward servant leadership. In effect, they perceive servant leadership to be a means to bring about self-value (Li et al., 2020). In particular, this study proposes and demonstrates that employees who exhibit proactive tendencies are more likely to leverage the work environment fostered by a servant leader in order to engage in work reflection. In contrast, less proactive employees are more inclined to stick to their current work and are unwilling to seek new breakthroughs before engaging in reflection and adapting their objectives and approaches. Therefore, this study suggests that the interaction between employee proactive personality and servant leadership encourages employee work reflection, which in turn encourages employee voice behavior. In summary, the conceptual model is depicted in Figure 1.

This study makes two major contributions to existing literature. First, SCT is applied as a framework to integrate a distinct cognitive construct into the existing bodies of research on servant leadership and voice behavior. Specifically, that construct is employee work reflection. Employee work reflection complements the forward-looking perspective to delineate how employees engage in voice behavior in response to servant leadership through internal self-reflection. By highlighting work reflection, this study provides a deeper understanding of how cognitive processes influence the way employees perceive and react to servant leadership, thereby offering a more comprehensive view of the mechanisms driving voice behavior in the context of servant leadership. Second, by identifying employee proactive personality as a moderating factor, this study underscores the importance of individual differences in shaping the outcomes of servant leadership. It extends the existing servant leadership literature by elucidating how employee-related factors, can influence the effectiveness of servant leadership. Additionally, this study helps develop SCT in the servant leadership domain by recognizing employee personality as a key compositional factor that can modulate the influence of leaders as role models within their organizations.

This study explains the impact of servant leadership on employee voice behavior according to SCT. Founded by Bandura, SCT is the basic theory of individual behavior; SCT refers to the continuous and dynamic interactive relationship between the external environment, cognitive factors, and individual behavior. According to Bandura (2006), a bidirectional relationship exists between any two factors, and they constantly change under different environments, individuals, and behaviors. An individual’s behavior is seen as a product of the combination of individual cognition and external environmental factors. In addition, SCT has been extensively employed to gain insights into and make predictions about individual behavioral choices and behavioral characteristics (Leblanc et al., 2022).

Within the framework of SCT, servant leadership is characterized by a supportive and empowering essence and serves as a distinct environmental stimulus. Its influence manifests by promoting individual cognitive responses (work reflection and voice behavior) among team members regarding their work roles within the organization. Moreover, proactive personality serves a pivotal role in determining how individual employees exploit this supportive environment. Proactive individuals are hypothesized to exhibit more robust responses to servant leadership, given that their innate tendency to actively engage with their environment bolsters their reflective processes and amplifies their vocal expressions. This interaction highlights the complex interplay between personal characteristics and environmental cues in shaping behavior, reflecting the SCT’s perspective that behavior is a product of both personal and environmental factors.

Servant leadership is a style of leadership in which the satisfaction of employees’ needs, desires, and interests are prioritized and used to lead subordinates. The leaders acquire employees’ confidence and exert influence by regularly providing services to them (Ehrhart, 2004; Liden et al., 2008). In essence, servant leaders are primarily motivated by service rather than leadership; they see leadership positions as an opportunity to serve others. Such leaders model the way for subordinates to learn; the ultimate goal of service is to help them grow as servants, thereby benefiting the whole organization (Lemoine et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). Within this novel context, servant leadership has been proven to be actively correlated with both individual positive behaviors (such as pro-social behavior) and job performance (Eva et al., 2019; Hui et al., 2020). This study posits that, within organizations, servant leadership heightens employee voice behavior. Specifically, SCT emphasizes the dynamic interaction between the external environment and an individual’s behavior. An individual observes the exemplary behaviors of others to construct a self-cognitive awareness and in this way either directly or indirectly learns appropriate behaviors (Bandura, 1986). As an extra-role behavior, voice behavior helps the organization to obtain its objectives and also enhances organizational effectiveness. This is the effective outcome of employee modeling and learning form servant leadership (Walumbwa et al., 2010). At the same time, servant leadership tends to empower and promote self-management by employees, while voice behavior allows employees to express their views and provide suggestions regarding problems in organizational decision-making (Hunter et al., 2013). That is, servant leadership provides a channel through which employees can add their voice. In addition, the empowerment of servant leaders’ advice will stimulate employees’ sense of efficacy and self-confidence, keep them enthusiastic in the work process, and make it easier to motivate them to use their voice (Duan et al., 2014). Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 1: Servant leadership is positively related to employee voice behavior.

Drawing upon the framework of social cognitive mechanisms, this study maintains that individuals engage in the process of understanding the external environment in order to adjust their self-cognition and behavior. Ultimately, this adaptive process serves the objective of establishing and maintaining consistency with the external environment (Bandura, 1986). In line with this framework, we propose that servant leadership heightens employee work reflection, acting as a cognitive bridge between leadership influence and employee voice behavior. This reflective process includes examining past actions, considering alternative strategies, and planning future actions, thereby enhancing employees’ cognitive and emotional involvement and commitment to their work (Schippers et al., 2015; Lyubovnikova et al., 2017). Previous studies have examined other mediators of the relationship between servant leadership and employee outcomes. For instance, psychological safety has been identified as a key mediator, explaining how servant leadership fosters an environment where employees feel safe to express their ideas without fear of negative consequences (Edmondson, 1999). Similarly, psychological empowerment has been explored as a mediator, highlighting how servant leadership enhances employees’ sense of autonomy and control over their work (van Dierendonck and Nuijten, 2011).

On the one hand, servant leadership, characterized by its service and empowerment, uniquely stimulates employees’ potential and challenges them to enhance their self-efficacy. This leadership style guides the overall development of employees within an atmosphere of service, fostering an environment where positive cognitive processes are initiated (Ong et al., 2023). Further, servant leadership promotes individual reflection by providing a model for service and behaviors that employees can emulate (Zhang et al., 2012). For example, when leaders demonstrate humility and a commitment to service, employees are more likely to reflect on their own behaviors and strive to align them with these values (Walumbwa et al., 2010). This modeling effect triggers a positive cognitive response, strengthening employees’ sense of responsibility and mission within the organization. Consequently, servant leadership enables employees to get more service, support, and resources, thereby stimulating employee work reflection.

On the other hand, as a cognitive state, employee work reflection will further enable employees to get a deeper comprehension of how they can cognitively contribute functional value to their organizations. Prior research has identified work reflection as key for employee organizational citizenship behavior and prosocial behavior because it integrates diverse experiences and enhances awareness of organizational needs and challenges (Carlson et al., 2016; Thompson and Bolino, 2018). By reflecting, employees can evaluate work processes, identify improvements, and develop actionable suggestions, fostering continuous improvement (Schippers et al., 2015). Moreover, positive outcomes from reflection can motivate employees to set more ambitious and innovative goals, encouraging them to invest resources and effort into voicing ideas (Bandura, 1991; Schaubroeck et al., 2011; Lyubovnikova et al., 2017). Thus, employees can use reflection not only to address challenges but also to propose new initiatives, aligning with organizational objectives (Bandura and Locke, 2003; Parker et al., 2010). Furthermore, work reflection enhances employees’ emotional regulation, which is crucial when engaging in voice behavior, often seen as risky (Liang et al., 2012). Effective emotional regulation can reduce the anxiety associated with voicing concerns and suggestions. Taken together, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 2: Employee work reflection mediates the relationship between servant leadership and employee voice behavior.

Although servant leadership is typically perceived as supportive and empowering, its effectiveness can vary depending on employee personal traits. For instance, servant leadership has been found to be positively related to employees with higher levels of self-interest (Wu et al., 2021) or political skills (Liao et al., 2021). As has been proven, SCT reveals that individuals process information about the external environment through individual factors, such as typical personality traits, which jointly affect individual psychological cognitions and behaviors (Martinko et al., 2002). Thus, it is crucial to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the specific individual characteristics that determine the effectiveness of servant leadership.

As a key aspect of the individual factors (Maloney et al., 2016), this study suggests that the phenomenon of employee proactive personality can moderate the magnitude of servant leadership effectiveness (Chiu et al., 2016; Hu and Judge, 2017). Proactive personality is defined as an inclination toward initiative and perseverance in effecting meaningful change (Crant and Bateman, 2000). Specifically, employees with a high level of proactive personality tend to engage more actively in a servant leadership climate. Such employees are adept at identifying opportunities and are motivated by the servant leader’s behaviors that foster growth and autonomy (Crant et al., 2011; Liang and Gong, 2013). Noticing the servant leader’s dedication to their development and the encouragement of their ideas, proactive employees are likely to use this nurturing environment to engage in work reflection, which can enhance their voice behavior (Kish-Gephart et al., 2009). In contrast, employees with a low level of proactive personality tend be passive recipients of the environment (Chong et al., 2021) and less likely to identify and act on opportunities. Such employees have a preference for maintaining the current state of affairs (Crant and Bateman, 2000), adhering to established work procedures and relying on their supervisor to address problems as they emerge (Crant et al., 2017). Consequently, they may not fully benefit from the inclusive and developmental behaviors of a servant leader and less likely to engage in spontaneous work reflection. Their passive attitude and reliance on external direction can hinder the effectiveness of servant leadership in fostering work reflection and subsequent voice behavior. Hence, this study hypothesizes as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Servant leadership and employee proactive personality will interact to influence employee work reflection, such that the relationship will be positive when there is an elevated level of employee proactive personality.

Hypothesis 4: Employee proactive personality plays a moderating role in the indirect relationship between servant leadership and employee voice behavior through employee work reflection, such that the relationship is positive when the level of employee proactive personality is high.

To observe the proposed impact of servant leadership and to minimize common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012), a three-wave time-lagged design was used to collect data via the Internet. Specifically, a Credamo web-based survey platform was employed. Credamo and other online platforms have been shown to be reliable sources of data, attracting subjects with real work experience, and producing outcomes that are equivalent to those attained by utilizing samples from traditional sources. First, the survey’s purpose was explained to the platform managers, who were able to help contact participants and confirm their participation. Then, participants were invited to voluntarily join the online survey. High sample diversity has been shown to enhance the external validity or generalizability of the relevant study’s results (Demerouti and Rispens, 2014). In this study, 572 employees from different industries, including service, manufacturing, the financial sector, information technology, etc., expressed their willingness to participate.

Second, in order to infer the causal relationships in the hypothesized model, a unique code was generated to ensure the respondents’ anonymity, and three-phase data collection was conducted at one-month intervals, from April to July, 2023. In Phase 1 (T1), the respondents were asked to assess their perceptions of servant leadership and to self-evaluate their proactive personality; they also provided their demographic information. Demographic information collected included age, gender, education level, tenure, team scale and industry type, ensuring a comprehensive profile of the sample was captured. As stated above, 572 responses were received. In Phase 2 (T2, 1 month later), the 572 participants were asked to complete the section relating to employee work reflection; 532 responses were received, yielding a response rate of 93.0%. In Phase 3 (T3, 1 month later), the 532 employees who had participated in Phase 2 were asked to assess their voice behavior experience. At that time, 501 responses were received, yielding a response rate of 87.6%. All respondents who filled out the survey and fully answered the questionnaire received a payment of approximately 5 RMB. After deleting unmatched and incomplete questionnaires, the final and valid sample consisted of 489 participants from different industries, giving a valid response rate of 85.5%.

Of the final 489 employees, 158 (32.3%) were male, and 331 (67.7%) were female, and 364 (74.5%) had received a college or undergraduate education. Most of the respondents were from 31 to 35 (219: 44.8%) or 25–30 years old (120: 24.5%). The organizational tenure for most respondents ranged from 6 to 10 years (218: 44.6%). The manufacturing industry accounted for the largest proportion of the employees (174: 35.6%). The largest proportion of the participants worked in teams that ranged in size from 11 to 20 (210: 42.9%). The demographic profile information is depicted in Table 1.

The commonly used back-translation procedure was used to generate the Chinese measures for the questionnaires in this study (Brislin, 1986). A 5-point Likert scale was adopted, with values ranging from 1 = strongly disagree/worst, to 5 = strongly agree/best.

Each employee was asked to rate his or her perceptions of servant leadership, using a seven-item scale developed by Liden et al. (2015). Example items include, “My leader makes my career development a priority,” and “My leader puts my best interests ahead of his/her own.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.717.

Similar to Leblanc et al. (2022), we measured employee work reflection with eight items from Ong et al. (2023). Example items include, “I reflect on whether I am meeting the project goals,” and “I reflect on the kind of energy I am bringing to the project.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.712.

This was measured using the 10-item scale developed by Liang et al. (2012). Sample items include, “I proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the unit,” and “I speak up honestly with regard to problems that might cause serious loss to the work unit, even when/though dissenting opinions exist.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.725.

This was assessed using a 10-item scale developed by Seibert et al. (1999). A representative item is, “Wherever I have been, I have been a powerful force for constructive change.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.733.

In this paper, gender, age, education level, tenure, team scale, and industry type are used as control variables, following established precedents in the literature. Gender was a dummy variable, coded as 1 for men and 0 for women, as gender differences may influence behavior and perceptions within organizational settings (Eagly and Carli, 2009). The age variable includes six grades, reflecting the potential impact of age on employee attitude and motivation (Truxillo et al., 2015). The education level covers three grades, which correlates with job performance (Ng and Feldman, 2009). Tenure covers five grades, used to control for varying levels of experience which can affect employees’ accumulation of institutional knowledge (Ng and Feldman, 2010). Team scale covers five grades, included as larger teams may experience different dynamics and efficiency levels (Hoegl and Gemuenden, 2001). Finally, industry type covers six grades, as industry-specific factors can significantly impact employee behavior and organizational outcomes (Tabassi et al., 2019).

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and scale reliabilities for the study’s variables. As shown in Table 1, the total Cronbach’s α coefficients of all scales are greater than 0.70, indicating that each scale has good internal consistency. The correlation matrix shows that servant leadership was found to be positively related to employee work reflection (r = 0.634, p < 0.01), and that employee work reflection was found to be positively related to employee voice behavior (r = 0.670, p < 0.01). These findings are is in line with prior theorizing on SCT Furthermore, consistent with our SCT framework, servant leadership was found to be positively related to employee voice behavior (r = 0.710, p < 0.01).

To assess the appropriateness of the measurement model, including the five studied variables, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Mplus 8.3 software was first performed to assess the model fit (Muthén and Muthén, 2012). The fit indices involved a comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square residual (RMSEA). All these methods have been commonly used to evaluate various aspects of model fit and have been reported in related organizational literature (Brown, 2006). As indicated in Table 3, the results show that the hypothesized four-factor model had an adequate fit [χ2 (504) = 836.798, TLI = 0.920 > 0.90, CFI = 0.932 > 0.90, RMSEA = 0.037 < 0.05, SRMR = 0.046 < 0.08] and was better than other alternative models. Therefore, the focal constructs are distinct in this study.

Modeling path analysis and Monte Carlo simulation were conducted through Mplus and R package to test the mediation and moderation hypotheses, with confidence intervals. A total of 20,000 estimation times are recommended when using the Monte Carlo bootstrapping method (Hayes, 2015), and Table 4 presents the result of hypotheses testing and Figure 2 summarizes the hypothesis model. As shown in Figure 2, the direct effects of servant leadership on employee voice behavior is significant (β = 0.349, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Specifically, servant leadership exhibited a significant positive relationship with employee work reflection (β = 0.507, p < 0.001). Furthermore, employee work reflection was positively related to employee voice behavior (β = 0.359, p < 0.001). Referring to Table 4 and Figure 2, the mediating effect of employee work reflection between servant leadership and employee voice behavior was found to be significant (β = 0.228, p < 0.001, SE = 0.027, 95% CI [0.177; 0.281], Model 2). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

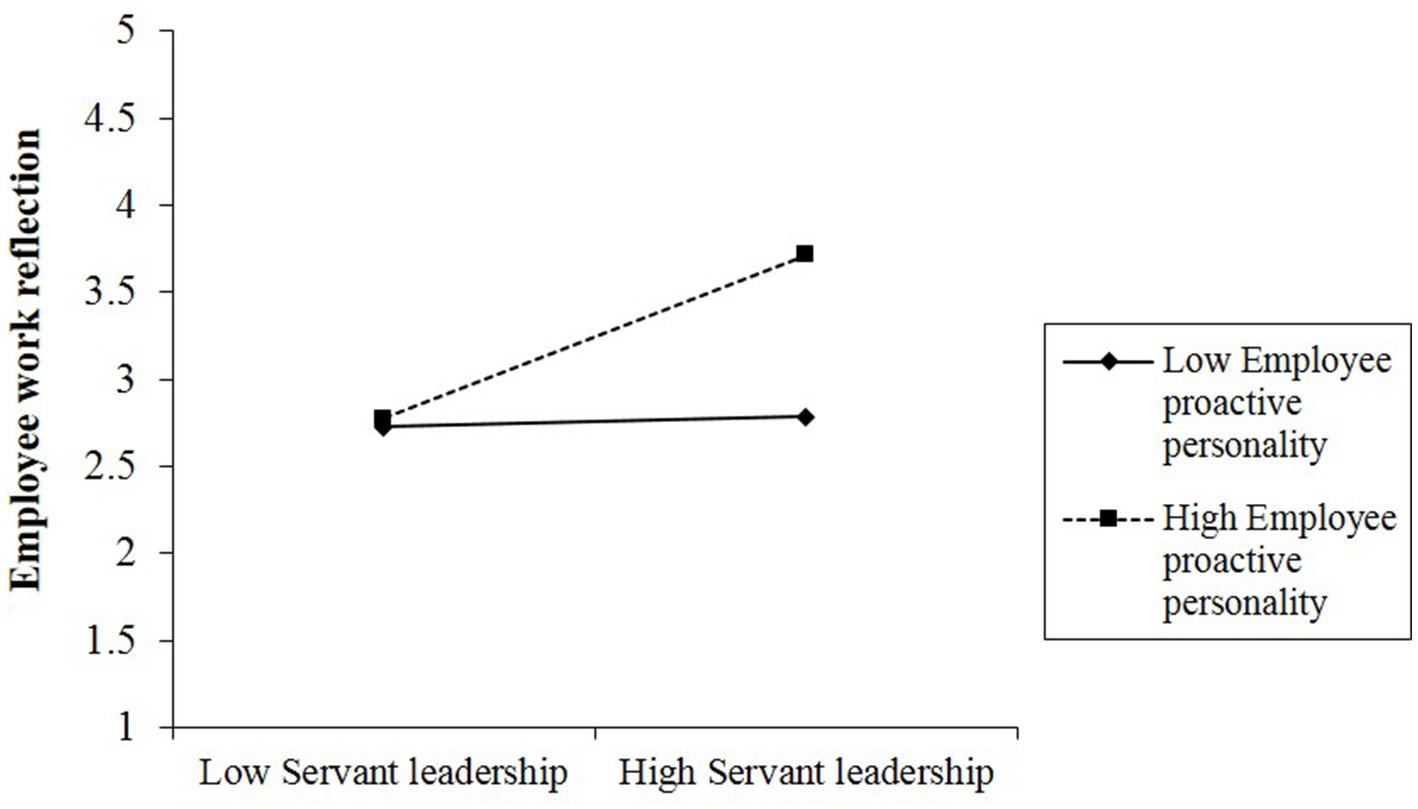

Hypothesis 3 proposes that employee proactive personality accentuates the relationship between servant leadership and employee work reflection. As indicated in Figure 2, the moderating effect of proactive personality was significant (β = 0.221, p < 0.001). According to the method of Aiken and West (1991), the significant moderating effects were plotted in Figure 3 using the moderator at high (one standard deviation above the mean value) and low (one standard deviation below the mean value) levels. Furthermore, the significance of the simple slope at high and low levels was examined using the bootstrapping method with Monte Carlo simulation. When employee proactive personality was high, servant leadership was found to have a significant effect on employee work reflection (effect = 0.768, p < 0.001, SE = 0.040, 95% CI [0.690; 0.846], Model 3). Under the condition of low employee proactive personality, the relationship was also found to be significant (effect = 0.473, p < 0.001, SE =0.039, 95% CI [0.396; 0.551], Model 3). The difference between these two slopes was also significant (Δeffect = 0.295, p < 0.001, SE = 0.029, 95% CI [0.239; 0.351], Model 3). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 3. The interactive effect of servant leadership and employee proactive personality on employee work reflection (Study 1).

The results presented in Table 4 also support the moderated mediation effects. The mediating effect of leader identity between servant leadership and employee voice behavior under the condition of employee proactive personality was found to be significant (Δeffect = 0.108, p < 0.001, SE = 0.015, 95% CI [0.080; 0.140], Model 4). Thus, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Despite the multi-time point design, Study 2 further explored the moderating effect of employee proactive personality in an experiment to establish a clearer causal relationship between servant leadership and employee work reflection. This approach allowed for a focused examination of how servant leadership and proactive personality interact to influence work reflection (Hypothesis 3).

To complete Study 2, we recruited 107 full-time employees from China, all with prior team experience under supervision, via the Credamo platform. The appropriate sample size for Study 2 was estimated using the G*power (Erdfelder et al., 1996). Given the two-factor between-subjects experimental design, the following parameters were specified: an F-test with ANOVA for fixed effects, special, main effects, and interactions, an effect size f of 0.40 (reflecting a medium to large effect size based on Cohen’s conventions), an alpha level (α) of 0.05, and a desired power (1-β) of 0.80. The numerator degrees of freedom were set to 1, and the number of groups was set to 4, corresponding to the 2×2 factorial design (Clemente et al., 2020). The results of G*power show a minimum sample size of 52 participants is required to achieve statistically significant results, which is much smaller than the actual sample size of this study (N = 107).

These employees represented a diverse range of industries including IT, biopharmaceuticals, product manufacturing, engineering, chemical engineering, and procurement. Participants who joined the experiment through Credamo were compensated with 2 RMB. Further details about the sample include 52 (48.6%) were male, and 55 (51.4%) were female, and 90 (84.1%) had received a college or undergraduate education. Most of the respondents were from 26 to 30 (30: 28.0%) or 31–40 years old (35: 32.7%). The organizational tenure for most respondents ranged from 6 to 10 years (27: 25.2%). The information technology industry accounted for the largest proportion of the employees (32: 29.9%).

Both servant leadership and employee proactive personality were manipulated, leading to 2 (servant leadership: high vs. low) × 2 (employee proactive personality: high vs. low) between-subjects design. The participants were randomly allocated to one of the four experimental conditions. Twenty-eight individuals were assigned to the condition of high servant leadership, with high employee proactive personality; 26 participants were assigned to the condition of high servant leadership and high employee proactive personality; 26 participants, and 27 participants, respectively, were assigned to each of the other two conditions. Employee work reflection was the dependent variables. Participants were informed that their task in the experiment involved reading a concise, hypothetical scenario and answering a series of questions related to it.

Across all four experimental conditions, the fundamental scenario description remained consistent. Participants were instructed to assume the role of an employee at a reputable general consulting firm, where the predominant work style involves functioning primarily as a project team. The team comprises the participant’s supervisor, Li Yang, and three other team members (including Participants). Since their appointment, they have encountered the following situations in their work environment.

For parsimony, manipulation of servant leadership and employee proactive personality are demonstrated in Appendix A.

To assess perceptions of Li Yang’s servant leadership, the participants were asked 7 items developed by Liden et al. (2015). A sample item is “Li Yang puts my best interests ahead of his/her own.” The Cronbach’s α = 0.891.

To assess participants’ level of employee proactive personality, they were asked seven items developed by Seibert et al. (1999). Sample items include, “Wherever I have been, I have been a powerful force for constructive change.” The Cronbach’s α = 0.957.

The scale (Ong et al., 2023) adopted in Study 1 was also used to assess employee work reflection. A sample item of fixed mindset is, “I reflect on whether I am meeting the project goals.” The Cronbach’s alpha of coworker malicious envy was 0.951.

The same control variables were used as those of Study 1: gender, age, education level, industry type.

To test whether the manipulation of servant leadership vs. employee proactive personality was successful, participants were asked to “Based on the above scenario, please judge to what extent the supervisor on the team, Li Yang, exhibits servant-leader behaviors?” “Based on the above scenario, please determine the extent to which I on the team exhibit a proactive personality?” Both items were assessed on a 5-point scale (from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much). An analysis of the variance results show that the servant leadership manipulation had a strong effect on the servant leadership check (F = 817.836, p < 0.001, η2 = 1.665). Similarly, the employee proactive personality manipulation had a strong effect on the employee proactive personality check (F = 535.724, p < 0.001, η2 = 2.348). These results indicate that our manipulations were successful.

The calculation of the intercorrelations showed that servant leadership correlated with employee proactive personality; r = 0.225, p < 0.05, and employee proactive personality correlated with employee work reflection, r = 0.799, p < 0.01. The observed correlations suggest that the investigated constructs are correlated, yet they do not demonstrate a high degree of similarity. Consequently, they exhibit adequate discriminant validity. Table 5 displays the correlation coefficients of the variables.

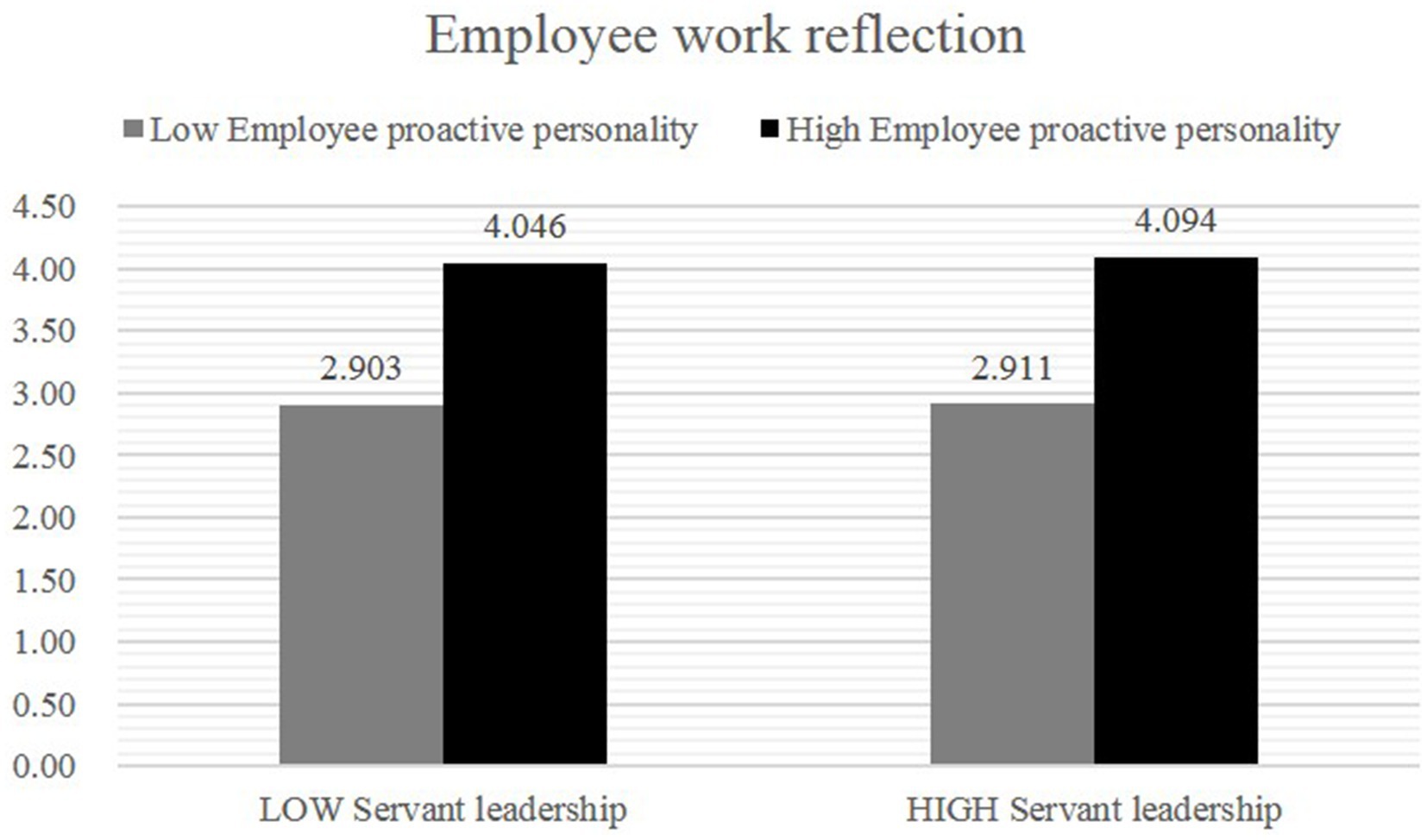

Hypothesis 3 predicts an interactive effect of servant leadership and employee proactive personality on employee work reflection. The analysis of the variance results suggest that the interactive effect of servant leadership and employee proactive personality on employee work reflection was significant, F = 3.249, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.314. The direction of the interaction effect was in the hypothesis direction (Figure 4). Planned comparisons show that, in the low employee proactive personality condition, the levels of employee work reflection were significantly higher in the high servant leadership condition (M = 2.911, SD = 1.03) than in the low servant leadership condition (M = 2.903, SD = 1. 056). Moreover, when participants were in the high employee proactive personality condition, those in the high servant leadership felt a significantly higher level of employee work reflection (M = 4.094, SD = 0.626) than in the low servant leadership condition (M = 4.046, SD = 0.340).

Figure 4. The interactive effect of servant leadership and employee proactive personality on employee work reflection (Study 2).

In sum, through an experimental manipulation, Study 2 provides strong evidence of the interactive effects of servant leadership and employee proactive personality on employee work reflection. Results from the independents samples demonstrate that the relationship between servant leadership and employee work reflection is stronger when employee proactive personality is high than when it is low. Hence, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

This study contributes to servant leadership literature in several ways. Firstly, a novel theoretical framework is presented that integrates the servant leadership and employee voice literatures by introducing employee work reflection as individual cognitive process. While previous research has shown that servant leadership promotes voice behavior through modeling and interaction (Detert and Treviño, 2010; Arain et al., 2019; Liao et al., 2021; Hartnell et al., 2023), the cognitive mechanism linking servant leadership and employee voice behavior has remained unclear. This study highlights how internal employee reflection processes mediate the influence of servant leadership on employee voice behavior, focusing on understanding internal controllable factors and the external environment.

Secondly, this research supports the view that the efficacy of servant leadership depends on individual factors (Hartnell et al., 2023). It highlights the significant moderating role of employee proactive personality, addressing calls for elucidation of individual traits within the servant leadership process (Arain et al., 2019). The findings indicate that servant leadership may not inspire voice behaviors in employees lacking proactive personality. This underscores the importance of considering individual differences when evaluating servant leadership, thus expanding the existing literature by incorporating individual inclinations within the SCT framework.

Finally, this study integrates SCT with existing servant leadership literature. Previously, servant leadership and employee positive extra-role behavior research has leaned largely on social exchange theory (e.g., Mayer, 2010). Based on SCT, this study argues that servant leadership stimulates employee voice behavior by encouraging employees to engage in work reflection. This broadens the scope of servant leadership’s impact by illustrating its indirect effect on employee voice behavior, highlighting the importance of cognitive and personality factors in this dynamic.

The findings of this research provide some practical implications. First, the results highlight the crucial role of employee work reflection in promoting employee voice behaviors. Organizations should encourage work reflection by guiding employees through action reviews or organizing reflection sessions. Inducing work reflection through carefully selected methods can enhance employee voice behavior.

Another key finding is that servant leadership is more salient for employees with a high level of proactive personality. Organizations should consider proactive personality as a significant moderator of employees’ response to servant leadership. For proactive employees, servant leadership enhances motivation to voice. To improve decision-making and organizational learning, organizations should identify proactive individuals and allocate resources to foster their ability to voice.

Finally, this study highlights the value of servant leadership in organizations. Servant leaders encourage high levels of employee voice behavior. Therefore, organizations should implement training initiatives to enhance leaders’ understanding and practice of servant leadership. Additionally, fostering an environment that promotes and incentivizes servant leadership behaviors is recommended.

Despite the significant theoretical and practical implications, this study also has some limitations. First, employee proactive personality was only examined as a moderator, and employee work reflection was only examined as a mediator. Future research should examine other individual moderators (such as political skill) and other potential mediators (such as psychological safety). This is because employees with high levels of political skill are better able to navigate organizational dynamics and build relationships, which can enhance their voice behaviors. Similarly, a psychologically safe environment encourages employees to express their ideas and concerns without fear of negative consequences. Exploring these factors would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the influences on employee behavior.

Second, the specific cultural and organizational context of the sample further limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research should replicate this study in different cultural and organizational settings to determine whether the findings hold across various contexts. This would enhance the external validity of the study and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play in diverse environments.

Third, this study may not fully eliminate common method bias, as all assessments were self-reported by employees. To mitigate this bias, this study employed time-lagged questionnaires and utilized scales that had been previously validated. However, to further address the potential impact of self-reporting bias and enhance the robustness of the conclusions, we suggest that future studies should gather data from additional sources such as peer assessments, supervisory ratings, or objective performance indicators. These measures could help to reduce the reliance on self-reported data and provide a more comprehensive view of the variables involved.

Fourth, in Study 1, more than 50% of the participants were female, gender has been shown to correlate with employee voice behavior. Exploring how gender and other demographic variables influence the effectiveness of servant leadership could provide deeper insights into the dynamics at play. We recommend that future research explore the data associated with participant characteristics such as gender.

This research contributes to servant leadership literature by empirically investigating how and when servant leadership promotes employee voice. Based on a three-wave time survey and one experimental study, the findings of this study indicate that the mediating role of employee work reflection is significant in this particular relationship. In addition, employee proactive personality is found to act as a moderating factor. We anticipate further investigation into the mechanisms by which servant leadership is associated with employee outcomes, as well as the discovery of other factors and contextual limitations that influence the effectiveness of servant leadership.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Jilin University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ZX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. HW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. LL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan Project “Research on the Mechanism and Countermeasures of Digital Empowerment for Dual Innovation in Jilin Province Manufacturing Enterprises”(Grant No.20240701049FG).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1421412/full#supplementary-material

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. India: Sage.

Arain, G. A., Hameed, I., and Crawshaw, J. R. (2019). Servant leadership and follower voice: the roles of follower felt responsibility for constructive change and avoidance-approach motivation. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psy. 28, 555–565. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2019.1609946

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. England: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1991). “Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action” in Handbook of moral behavior and development. eds. W. M. Kurtines and J. L. Gewirtz, (England: Psychology Press). 45–103.

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Bandura, A., and Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 87–99. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.87

Brislin, R. W. (1986). “The wording and translation of research instrument” in Field methods in cross-cultural research. eds. W. J. Lonner and J. W. Berry (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage), 137–164.

Carlson, R. W., Aknin, L. B., and Liotti, M. (2016). When is giving an impulse? An ERP investigation of intuitive prosocial behavior. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11, 1121–1129. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv077

Chiu, C. Y. C., Owens, B. P., and Tesluk, P. E. (2016). Initiating and utilizing shared leadership in teams: the role of leader humility, team proactive personality, and team performance capability. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 1705–1720. doi: 10.1037/apl0000159

Chong, S., Van Dyne, L., Kim, Y. J., and Oh, J. K. (2021). Drive and direction: empathy with intended targets moderates the proactive personality–job performance relationship via work engagement. Appl. Psychol. 70, 575–605. doi: 10.1111/apps.12240

Clemente, F. M., Silva, A. F., Alves, A. R., Nikolaidis, P. T., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Lima, R., et al. (2020). Variations of estimated maximal aerobic speed in children soccer players and its associations with the accumulated training load: comparisons between non, low and high responders. Physiol. Behav. 224:113030. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113030

Crant, J. M., and Bateman, T. S. (2000). Charismatic leadership viewed from above: the impact of proactive personality. J. Organ. Behav. 21, 63–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200002)21:1<63::AID-JOB8>3.0.CO;2-J

Crant, J. M., Hu, J., and Jiang, K. (2017). “Proactive personality” in Proactivity at work. eds. S. K. Parker and U. K. Bindl (Routledge), 193–225.

Crant, J. M., Kim, T.-Y., and Wang, J. (2011). Dispositional antecedents of demonstration and usefulness of voice behavior. J. Bus. Psychol. 26, 285–297. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9197-y

Demerouti, E., and Rispens, S. (2014). Improving the image of student-recruited samples: a commentary. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 87, 34–41. doi: 10.1111/joop.12048

Detert, J. R., and Treviño, L. K. (2010). Speaking up to higher ups: how supervisor and skip-level leaders influence employee voice. Organ. Sci. 21, 249–270. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1080.0405

Duan, J., Kwan, H. K., and Ling, B. (2014). The role of voice efficacy in the formation of voice behaviour: a cross-level examination. J. Manag. Organ. 20, 526–543. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2014.40

Dutton, J. E., Ashford, S. J., O’ Neill, R. M., Hayes, E., and Wierba, E. E. (1997). Reading the wind: how middle managers assess the context for selling issues to top managers. Strateg. Manag. J. 18, 407–423. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199705)18:5<407::AID-SMJ881>3.0.CO;2-J

Eagly, A. H., and Carli, L. L. (2009). Through the labyrinth: the truth about how women become leaders. Gend Manag 24:308. doi: 10.1108/gm.2009.05324aae.001

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44, 350–383. doi: 10.2307/2666999

Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol. 57, 61–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02484.x

Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., and Buchner, A. (1996). GPOWER: a general power analysis program. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 28, 1–11. doi: 10.3758/BF03203630

Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., van Dierendonck, D., and Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: a systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q. 30, 111–132. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: a journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. America: Paulist Press.

Hartnell, C. A., Christensen-Salem, A., Walumbwa, F. O., Stotler, D. J., Chiang, F. F., and Birtch, T. A. (2023). Manufacturing motivation in the mundane: servant Leadership’s influence on employees’ intrinsic motivation and performance. J. Bus. Ethics 188, 533–552. doi: 10.1007/s10551-023-05330-2

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res 50, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

Hoegl, M., and Gemuenden, H. G. (2001). Teamwork quality and the success of innovative projects: a theoretical concept and empirical evidence. Organ. Sci. 12, 435–449. doi: 10.1287/orsc.12.4.435.10635

Hu, J., and Judge, T. A. (2017). Leader–team complementarity: exploring the interactive effects of leader personality traits and team power distance values on team processes and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 935–955. doi: 10.1037/apl0000203

Hui, B. P. H., Ng, J. C. K., Berzaghi, E., Cunningham-Amos, L. A., and Kogan, A. (2020). Rewards of kindness? A meta-analysis of the link between prosociality and well-being. Psychol. Bull. 146, 1084–1116. doi: 10.1037/bul0000298

Hunter, E. M., Neubert, M. J., Perry, S. J., Witt, L. A., Penney, L. M., and Weinberger, E. (2013). Servant leaders inspire servant followers: antecedents and outcomes for employees and the organization. Leadersh. Q. 24, 316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.12.001

Jiang, J., Dong, Y., Hu, H., Liu, Q., and Guan, Y. (2022). Leaders’ response to employee overqualification: an explanation of the curvilinear moderated relationship. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 95, 459–494. doi: 10.1111/joop.12383

Kauppila, O. P., Ehrnrooth, M., Mäkelä, K., Smale, A., Sumelius, J., and Vuorenmaa, H. (2022). Serving to help and helping to serve: using servant leadership to influence beyond supervisory relationships. J. Manag. 48, 764–790. doi: 10.1177/0149206321994173

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Detert, J. R., and Trevino, L. (2009). Silenced by fear: the nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 29, 163–193. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2009.07.002

Lanaj, K., Foulk, T. A., and Jennings, R. E. (2023). Improving the lives of leaders: the beneficial effects of positive leader self-reflection. J Manage 49, 2595–2628. doi: 10.1177/01492063221110205

Leblanc, P. M., Rousseau, V., and Harvey, J. F. (2022). Leader humility and team innovation: the role of team reflexivity and team proactive personality. J. Organ. Behav. 43, 1396–1409. doi: 10.1002/job.2648

Lemoine, G. J., Hartnell, C. A., and Leroy, H. (2019). Taking stock of moral approaches to leadership: an integrative review of ethical, authentic, and servant leadership. Acad. Manag. Ann. 13, 148–187. doi: 10.5465/annals.2016.0121

Li, F., Chen, T., Bai, Y., Liden, R. C., Wong, M. N., and Qiao, Y. (2023). Serving while being energized (strained)? A dual-path model linking servant leadership to leader psychological strain and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 108, 660–675. doi: 10.1037/apl0001041

Li, F., Chen, T., Chen, N. Y. F., Bai, Y., and Crant, J. M. (2020). Proactive yet reflective? Materializing proactive personality into creativity through job reflective learning and activated positive affective states. Pers. Psychol. 73, 459–489. doi: 10.1111/peps.12370

Li, A. N., and Tangirala, S. (2022). How employees’ voice helps teams remain resilient in the face of exogenous change. J. Appl. Psychol. 107, 668–692. doi: 10.1037/apl0000874

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., and Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad. Manag. J. 55, 71–92. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Liang, J., and Gong, Y. (2013). Capitalizing on proactivity for informal mentoring received during early career: the moderating role of core self-evaluations. J. Organ. Behav. 34, 1182–1201. doi: 10.1002/job.1849

Liao, C., Liden, R. C., Liu, Y., and Wu, J. (2021). Blessing or curse: the moderating role of political skill in the relationship between servant leadership, voice, and voice endorsement. J. Organ. Behav. 42, 987–1004. doi: 10.1002/job.2544

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., and Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: influence on individual and unit performance. Acad. Manag. J. 57, 1434–1452. doi: 10.5465/amj.2013.0034

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Meuser, J. D., Hu, J., Wu, J., and Liao, C. (2015). Servant leadership: validation of a short form of the SL-28. Leadersh. Q. 26, 254–269. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., and Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 19, 161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

Lapointe, E., and Vandenberghe, C. (2015). Trust, social capital development behaviors, feedback seeking and emotional exhaustion during entry. In: Academy of Management Proceedings. (Vol. 2015).Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management. doi: 10.5465/ambpp.2015.11494abstract

Lyubovnikova, J., Legood, A., Turner, N., and Mamakouka, A. (2017). How authentic leadership influences team performance: the mediating role of team reflexivity. J. Bus. Ethics 141, 59–70. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2692-3

Maloney, M. M., Bresman, H., Zellmer-Bruhn, M. E., and Beaver, G. R. (2016). Contextualization and context theorizing in teams research: a look back and a path forward. Acad. Manag. Ann. 10, 891–942. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2016.1161964

Martinko, M. J., Gundlach, M. J., and Douglas, S. C. (2002). Toward an integrative theory of counterproductive workplace behavior: a causal reasoning perspective. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 10, 36–50. doi: 10.1111/1468-2389.00192

Mayer, D. (2010). Servant Leadership and Follower Need Satisfaction In: Eds. van Dierendonck, D., Patterson, K. (Palgrave Macmillan, London: Servant Leadership). doi: 10.1057/9780230299184_12

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., and Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. J. Manag. Stud. 40, 1453–1476. doi: 10.1111/1467-6486.00387

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: integration and directions for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 5, 373–412. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2011.574506

Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 1, 173–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

Morrison, E. W., and Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: a barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 706–725. doi: 10.2307/259200

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide. 7th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Ng, T. W., and Feldman, D. C. (2009). How broadly does education contribute to job performance? Pers. Psychol. 62, 89–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.01130.x

Ng, T. W., and Feldman, D. C. (2010). The relationships of age with job attitudes: a meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 63, 677–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01184.x

Ong, M., Ashford, S. J., and Bindl, U. K. (2023). The power of reflection for would-be leaders: investigating individual work reflection and its impact on leadership in teams. J. Organ. Behav. 44, 19–41. doi: 10.1002/job.2662

Parke, M. R., Tangirala, S., Sanaria, A., and Ekkirala, S. (2022). How strategic silence enables employee voice to be valued and rewarded. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 173:104187. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2022.104187

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., and Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: a model of proactive motivation. J. Manag. 36, 827–856. doi: 10.1177/0149206310363732

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S. S., and Peng, A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 863–871. doi: 10.1037/a0022625

Schippers, M. C., West, M. A., and Dawson, J. F. (2015). Team reflexivity and innovation: the moderating role of team context. J. Manag. 41, 769–788. doi: 10.1177/0149206312441210

Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., and Kraimer, M. L. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 416–427. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.416

Sun, J., Liden, R. C., and Ouyang, L. (2019). Are servant leaders appreciated? An investigation of how relational attributions influence employee feelings of gratitude and prosocial behaviors. J Organ Behav. 40, 528–540. doi: 10.1002/job.2354

Tabassi, A. A., Abdullah, A., and Bryde, D. J. (2019). Conflict management, team coordination, and performance within multicultural temporary projects: evidence from the construction industry. Proj. Manag. J. 50, 101–114. doi: 10.1177/8756972818818257

Thompson, P. S., and Bolino, M. C. (2018). Negative beliefs about accepting coworker help: implications for employee attitudes, job performance, and reputation. J. Appl. Psychol. 103, 842–866. doi: 10.1037/apl0000300

Thompson, P. S., and Klotz, A. C. (2022). Led by curiosity and responding with voice: the influence of leader displays of curiosity and leader gender on follower reactions of psychological safety and voice. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 172:104170. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2022.104170

Truxillo, D. M., Cadiz, D. M., and Hammer, L. B. (2015). Supporting the aging workforce: a review and recommendations for workplace intervention research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav 2, 351–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111435

van Dierendonck, D., and Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: development and validation of a multidimensional measure. J. Bus. Psychol. 26, 249–267. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9194-1

Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., and Oke, A. (2010). Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: a cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 95, 517–529. doi: 10.1037/a0018867

Welsh, D. T., Outlaw, R., Newton, D. W., and Baer, M. D. (2022). The social aftershocks of voice: an investigation of employees’ affective and interpersonal reactions after speaking up. Acad. Manag. J. 65, 2034–2057. doi: 10.5465/amj.2019.1187

Wu, J., Liden, R., Liao, C., and Wayne, S. (2021). Does manager servant leadership lead to follower serving behaviors? It depends on follower self-interest. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 152–167. doi: 10.1037/apl0000500

Yang, H., van der Heijden, B., Shipton, H., and Wu, C. (2022). The cross-level moderating effect of team task support on the non-linear relationship between proactive personality and employee reflective learning. J. Organ. Behav. 43, 483–496. doi: 10.1002/job.2572

Zhang, H., Kwan, H. K., Everett, A. M., and Jian, Z. (2012). Servant leadership, organizational identification, and work-to-family enrichment: the moderating role of work climate for sharing family concerns. Hum. Resour. Manag. 51, 747–767. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21498

Keywords: servant leadership, employee voice behavior, employee work reflection, employee proactive personality, social cognitive theory

Citation: Xu Z, Gu Y, Wang H and Liu L (2024) Servant leadership and employee voice behavior: the role of employee work reflection and employee proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 15:1421412. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1421412

Received: 22 April 2024; Accepted: 16 July 2024;

Published: 29 July 2024.

Edited by:

Zhenduo Zhang, Dalian University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Huan Xiao, Nanchang University, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Xu, Gu, Wang and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Gu, Z3V5dWttdXN0QDE2My5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.