- 1Illedi HNP Srl, Giulianova, Italy

- 2Department of Psychology, Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany

- 3Associazione Nazionale Professionale di Antropologia (ANPIA), Bologna, Italy

- 4Department of Agricultural Economic, Agrarian University of Ecuador, Guayaquil, Ecuador

- 5Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy

- 6Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

- 7Department of Built Environment, Oslo Metropolitan University OsloMet, Oslo, Norway

- 8Centro Armonico Terapeutico (CAT), Campogalliano, Italy

Background: In a short time, the COVID-19 pandemic has exerted a huge impact on many aspects of people’s lives with a number of consequences, an increase in the risks of psychological diseases being one of them. The aim of this experimental study, based on an eighteen-month follow-up survey, is to assess the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, changes in stress, anxiety and depression levels, and the risks of developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Methods: A follow-up survey was performed on a sample of 184 Italian individuals to collect relevant information about the psychological impact of COVID-19. Predictors of the components of the psychological impact were calculated based on the ANCOVA model.

Results: The analysis of the online questionnaires led to the conclusion that a high percentage of the participants suffer from levels of stress, anxiety and depression higher than normal as well as an increased risk of PTSD. The severity of such disorders significantly depends on gender, the loss of family members or acquaintances due to the pandemic, the amount of time spent searching for COVID-19 related information, the type of information sources and, in part, on the level of education and income. The time factor had a more severe effect on the low-income population.

Conclusion: COVID-19 has entailed a very strong psychological impact on the Italian population also depending on the coping strategies adopted, the level of mindful awareness, socio-demographic variables, people’s habits and the way individuals use the available means of communication and information.

1 Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first identified in December 2019. In January 2020, a new type of virus from the coronavirus family, SARS-CoV-2, was clearly identified (Huang et al., 2020). After the initial spreading, COVID-19 quickly evolved into a global pandemic, with the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring it a global health emergency on January 30, 2020 (Sohrabi et al., 2020).

As of December 27, 2021, there were over 276 million confirmed cases and more than 5 million reported deaths from COVID-19 worldwide and there were approximately 6 million confirmed cases and nearly 140,000 deaths in Italy (WHO, 2021). The spread of COVID-19 was facilitated by contemporary travel and transportatsystems (Bielecki et al., 2021; Sharun et al., 2021).

Government responses included lockdowns, with Italy experiencing its first outbreak in Lombardy region in February 2020 (Romagnani et al., 2020).

The first period of total lockdown, the following partial reopening as well as the changing regulations enacted by different government policies regarding containment measures necessarily had important implications and impacts on people’s psyche (Xiong et al., 2020; Passavanti et al., 2021). Such effects were predominantly negative, increasing problems related to a wide range of mental disorders such as generalized stress, anxiety, depression, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), insomnia, and increased suicidal tendencies in people already suffering from psychological issues (Tee et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020).

Isolation and quarantine measures, which are commonly implemented during epidemics, generate separation and restriction of movement between human beings imposing, as a consequence, drastic changes in daily routines and requiring a psychic adaptation to the new living condition in a context of great physical, social, economic and psychological vulnerability (Passavanti et al., 2021; Gonçalves et al., 2022).

During the COVID-19 epidemic, scientists around the world performed surveys and questionnaires to understand the effects of the pandemic to provide useful answers and critical insights as quickly as possible to the population and governments (Pakenham et al., 2020; Akintunde et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2021).

Analyses of many studies have also revealed a tight correlation between the use of social networks, and digital tools in general, and the increase or decrease in people’s psychological distress, especially during periods of total lockdown (Planchuelo-Gómez et al., 2020; Tee et al., 2020; Himelein-Wachowiak et al., 2021; Passavanti et al., 2021). Furthermore, a clear correlation was found between the increase or decrease in disorders based on the type of use of social platforms used to obtain information and news about the ongoing pandemic and the evolution of the situation (Chand, 2021; Passavanti et al., 2021).

In accordance with the scientific literature reviewed, there are other factors that weigh on people’s mental health: the economic consequences on household incomes, the increasing uncertainty about pandemic development especially among young people, the greater psychological impact in some social categories such as doctors, nurses, university students, pregnant women, unemployed individuals (Cao et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020; Dean et al., 2021).

Previous studies suggest that lower levels of social and mental support, coupled with a heightened perception of risk, tend to correlate with the development of psychological symptoms (Bentenuto et al., 2021).

Moreover, research in the scientific literature suggests that various factors could contribute to psychological symptoms. These include coping mechanisms (Ho et al., 2020), individual temperament and attachment style (Moccia et al., 2020), insufficient information or rumours circulated on social media (Brooks et al., 2020; Roy et al., 2020), awareness and mindfulness abilities (Moccia et al., 2020; Wang C. et al., 2020; Wang H. et al., 2020; Passavanti et al., 2021).

Finally, lockdowns implemented to control the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have had profound effects on daily life worldwide. However, their impact on mental health remains unclear as available meta-analyses and reviews are primarily based on cross-sectional studies, despite some attempts to analyse its longitudinal effects (Prati and Mancini, 2021; Reagu et al., 2021).

This longitudinal study on an Italian sample concerns a second phase of a previously published international research effort in 2020 and enables to understand the evolution of the pandemic from both a social and a psychological perspective over an eighteen-month time span following the COVID-19 breakout in Italy (Passavanti et al., 2021).

Therefore, this study aims to investigate how variables may be impactful over a longer period: sociodemographic differences (gender, education, income), personality traits (coping strategies and mindfulness), situational factors (experiencing contagion or loss of family members), behavioral aspects (internet and social media usage, access to information).

By integrating these hypotheses into the study design, it is possible to obtain richer and contextualized data on the psychological impact of the pandemic, allowing for a better understanding of the factors influencing the mental health and well-being of those involved.

2 Methods

2.1 Setting, participants and procedure

The study was conducted by means of an online follow-up survey to Italian respondents who had participated in the first phase of this research performed in the spring of 2020 (Passavanti et al., 2021).

The follow-up survey questionnaire involved an exclusively Italian sample thus differing from the previous research which also included participants from six other countries. Google Forms was the online platform chosen for the administration of the questionnaires. Out of the initial 420 Italian survey population (Passavanti et al., 2021), a sample of 184 responded to the second survey between December 15, 2021 and December 30, 2021.

The personal data were collected, aggregated, and analysed anonymously, in observance of the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research on human subjects.

Only adult participants were allowed to join the survey, and informed written consent was obtained from each of them. Participants were given the freedom to choose whether or not to participate in the questionnaire posed minimal risk and could withdraw at any time.

The survey study underwent review and was approved by a major institutional board, namely the Norwegian Centre for Research Data.

2.2 Variables and metrics

Administered to participants from various Italian regions, the questionnaire explored different psychological aspects and consisted of three main sections:

1. Socio-demographic information: this section collected data on participants’ gender, nationality, age, education, knowledge of infected individuals, and their relationship with technology.

2. Relationship with social networks and leisure time: this part delved into participants’ engagement with social networks and their leisure activities.

3. Specific use of media and technologies during the pandemic period: the final section focused on participants’ utilization of media and technology during the pandemic, shedding light on their relationship with digital tools, especially during quarantine and lockdowns.

The survey was entirely written and administered in Italian. Anyway, the questions are translated into English in Tables 1, 2.

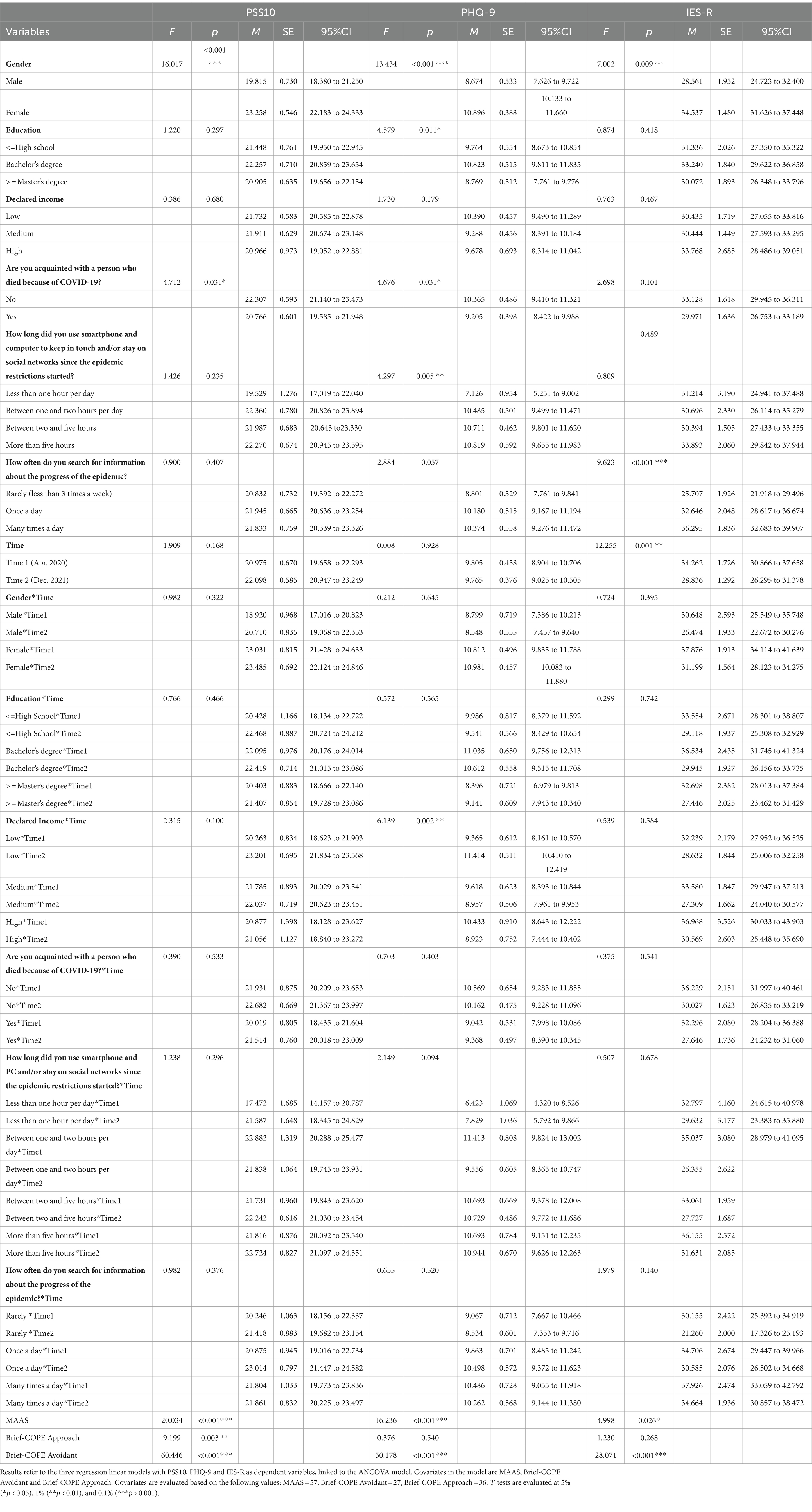

Table 1. Association between social demographics characteristics and the psychological impact of pandemic on the PSS10, PHQ-9 and IES-R.

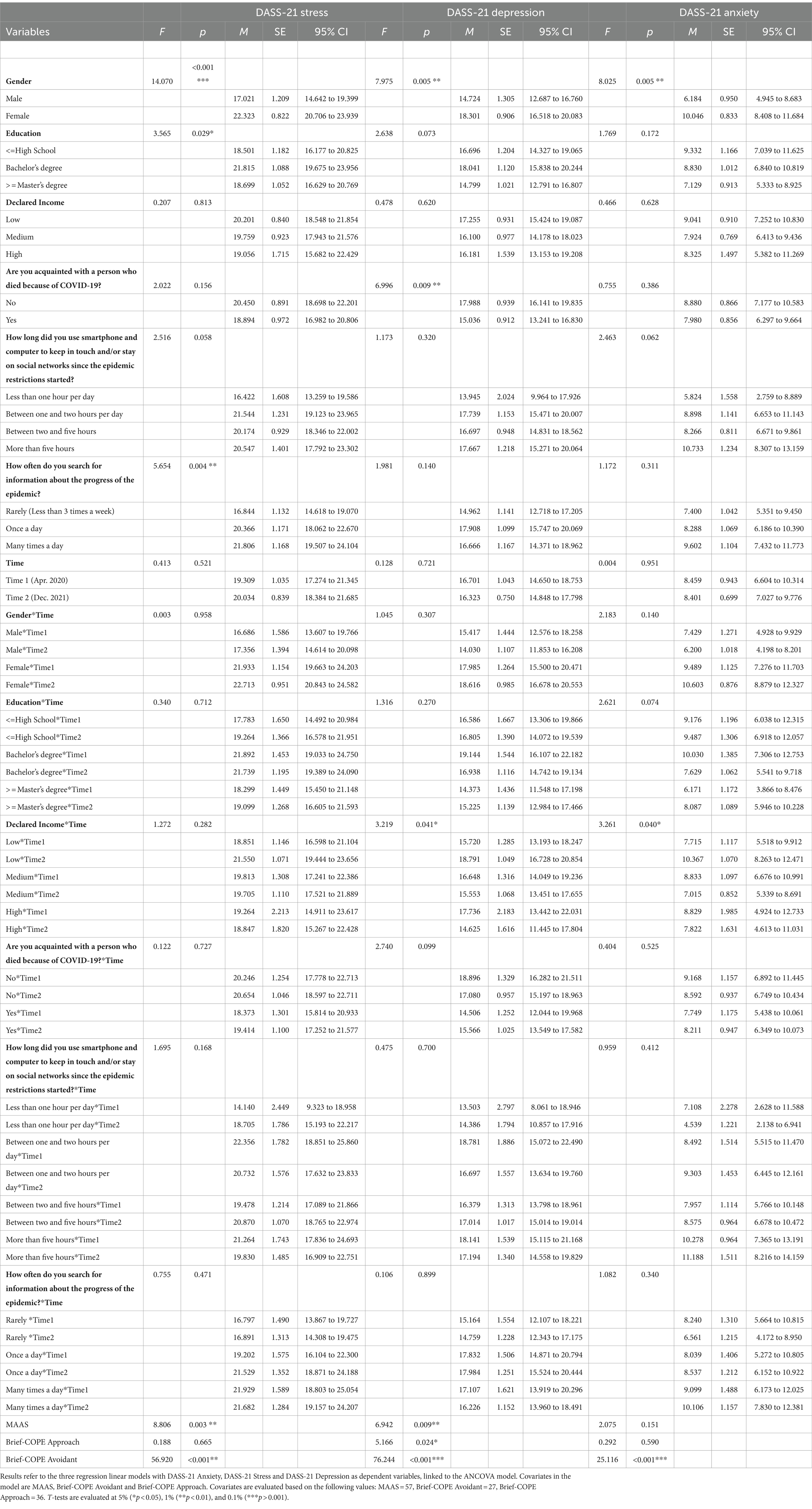

Table 2. Association between social demographics characteristics and the psychological impact of the pandemic on the DASS-21 subscales.

The overarching goal of the survey was to investigate COVID-19 awareness, coping strategies, the psychological implications as well as the role of technology as a vital source of communication and information during lockdowns (Luo et al., 2020).

To measure these aspects, self-administered psycho-diagnostic tests were used. These tests were previously validated in the international and Italian research (Moccia et al., 2020; Wang C. et al., 2020; Wang H. et al., 2020; Passavanti et al., 2021) and served the dual purpose of assessing individual characteristics and identifying the presence of psychopathologies.

This study utilized a range of established psychometric tools to assess various psychological aspects influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Mindfulness Awareness Attention Scale (MAAS), a 15-item questionnaire, evaluated attention and mindfulness, recognized for its reliability and strong associations with meditation and self-awareness, where higher scores indicate increased mindfulness (Brown and Ryan, 2003).

The Impact or Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), comprising 22 items on a 5-point Likert scale, measured PTSD, encompassing sub-dimensions of intrusiveness, hyper-arousal, and avoidance. A total score of 33 suggested potential PTSD, with the option to categorize psychological impact as normal, mild, moderate or severe (Creamer et al., 2003; Wang C. et al., 2020; Wang H. et al., 2020).

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) assessed psychological constructs such as depression, anxiety, and stress using a 21-item self-report scale on a 4-point Likert scale. While it did not provide clinical diagnoses, it gauged severity, with scores multiplied by 2 to indicate levels from normal to extremely severe (Henry and Crawford, 2005).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) employed a brief 4-point Likert scale to screen for mental health conditions, primarily depression, and considered functional impairment in daily activities. Scores ranged from 0 to 27, reflecting varying degrees of depression (Kroenke et al., 2001).

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS10) was used to ascertain perceived stress, utilizing a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4. The total score categorized stress levels as low, moderate, or high (Cohen et al., 1983).

The Brief-COPE, a concise version of the COPE, identified common coping strategies, categorizing them into avoidance (denial, substance use, venting, behavioral disengagement, self-distraction, guilt) and approach (active coping, positive reframing, planning, acceptance, seeking emotional support, seeking informational support) (Carver, 1997; Meyer, 2001).

These assessments were validated versions drawn from prior international research (Chew et al., 2020; Conversano et al., 2020; Dawson and Golijani-Moghaddam, 2020; Tee et al., 2020; Umucu and Lee, 2020; Yao, 2020; Yan et al., 2021). This approach enhances the study’s applicability and offers a comprehensive understanding of the psychological repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic across diverse cultural contexts, Italy included.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using the software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 26. The method applied was the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), which combines the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and linear regression covariates. The psychological effects of the pandemic (anxiety, stress, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder) during spring 2020 and spring 2021 were compared using a generalized linear model for repeated measurement. The model assumptions were found to be fulfilled with correlation between dependent and covariate variables and non-correlation between independent and covariate (Tables 1, 2).

In this research, the statistical analysis involved a sample of 184 Italian respondents, identifying the results related to the main psychological constructs considered.

The analysis was performed six times to elaborate the averages of the dependent variables related to the onset of psychopathological symptoms. Considering the previously cited existing literature and the follow-up nature of this research, variables related to coping strategies (Brief-COPE) and mindfulness (MAAS) were identified as covariates.

3 Results

3.1 Sociodemographic characteristics

In 2021, this study examines the psychological impact of COVID-19. Unlike the previous survey, which included participants from seven countries (Australia, China, Ecuador, Iran, Italy, Norway and the United States), this follow-up specifically targets Italian individuals.

The sample comprises 184 participants, consisting of 56 males (30.4%) and 128 females (69.6%). The average age is 27.22 (SD = 7.60). In a preliminary analysis, age did not appear to be a determining factor for stress, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Among the interviewees, 173 (94%) do not have children, while 11 (6%) have one child or more.

The survey also collects data on cultural and economic factors, including family income, occupation (study, work, or neither) and education. Within the interviewed sample, 35.3% of respondents (65) identify themselves as low-income, 47.3% (87) as medium-income, and 17.4% (32) as high-income. In terms of occupation, 7.1% are unemployed, 55.4% are students, 24.4% are workers, and 2.2% are both students and workers. Regarding education, 53 interviewees (28.7%) have a middle school education, 68 (37%) hold a bachelor’s degree and 63 (34.3%) have at least a master’s degree.

3.2 Psychological impact

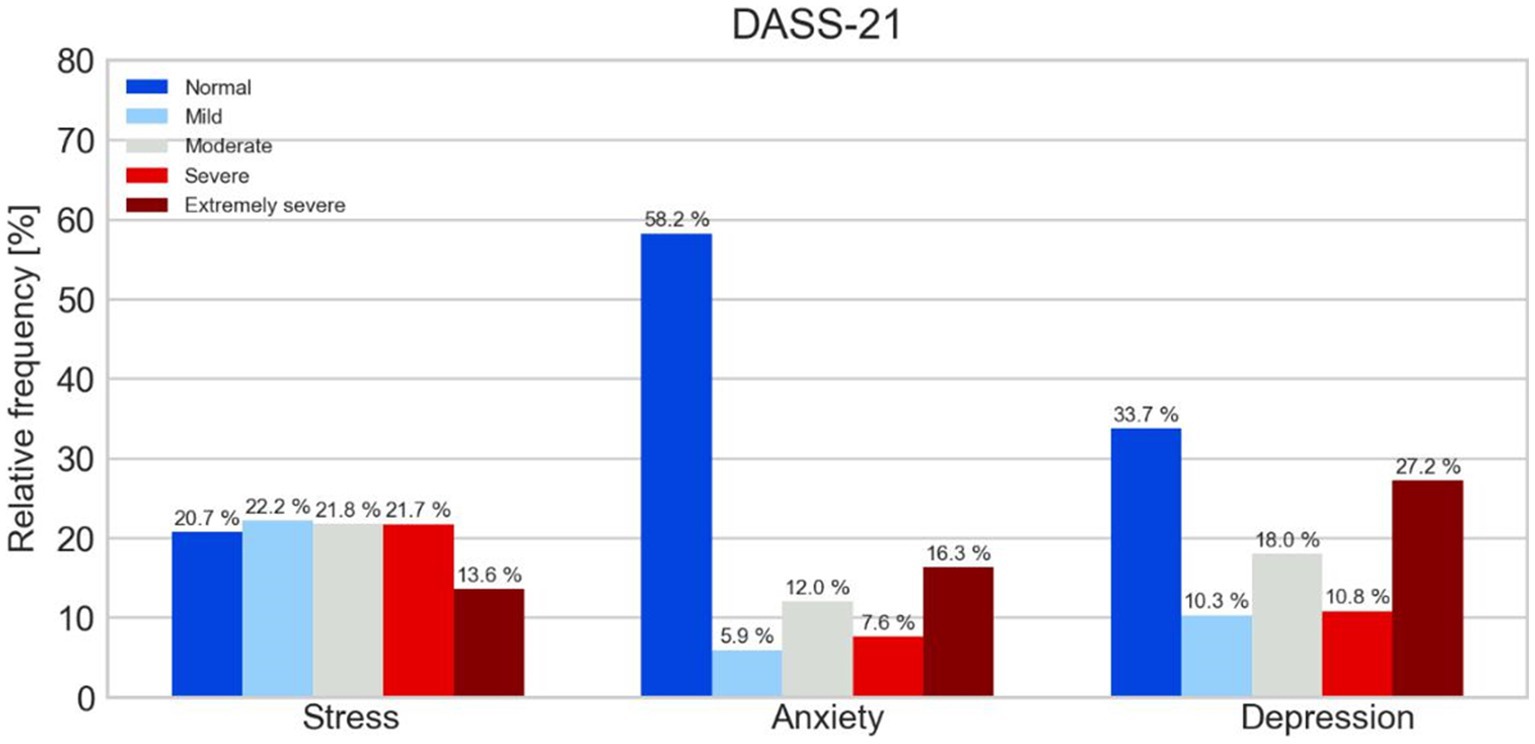

In Figure 1, the DASS-21 Stress subscale indicates 76 respondents (20.7%) with normal scores, 41 (22.2%) with mild stress, 40 (21.8%) with moderate stress, 40 (21.7%) with severe stress and 25 (13.6%) with extremely severe stress.

For the DASS-21 Anxiety subscale, 107 participants (58.2%) have normal scores, 11 (5.9%) mild anxiety, 22 (12%) moderate anxiety, 14 (7.6%) severe anxiety and 30 (16.3%) extremely severe anxiety.

Regarding the DASS-21 Depression subscale, 62 respondents (33.7%) are related to normal scores, 19 (10.3%) mild depression, 33 (18%) moderate, 20 (10.8%) severe and 50 (27.2%) extremely severe.

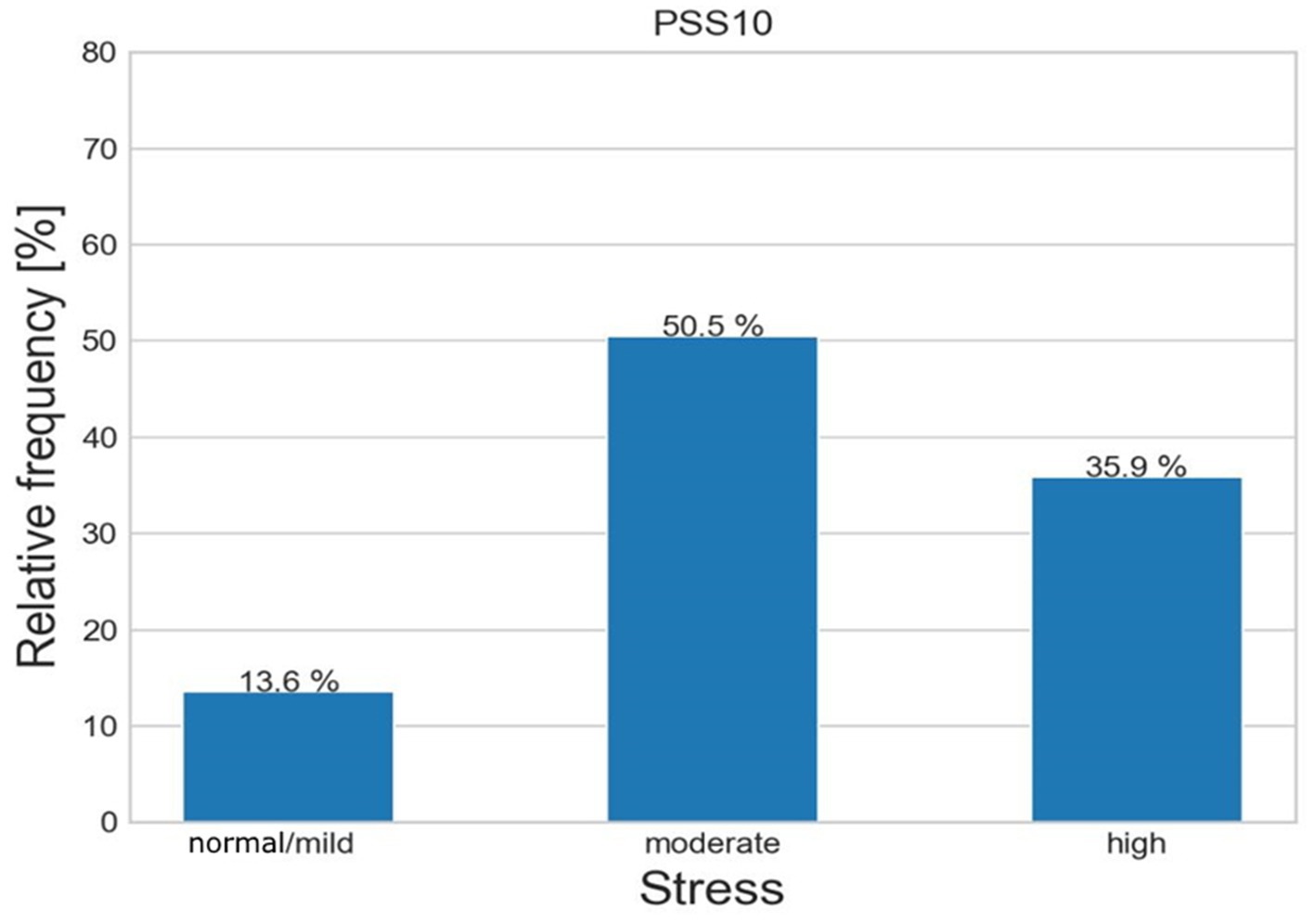

In Figure 2, PSS10 results show mild or absent stress in 25 individuals (13.6%), moderate in 93 (50.5%) and high in 66 (35.9%).

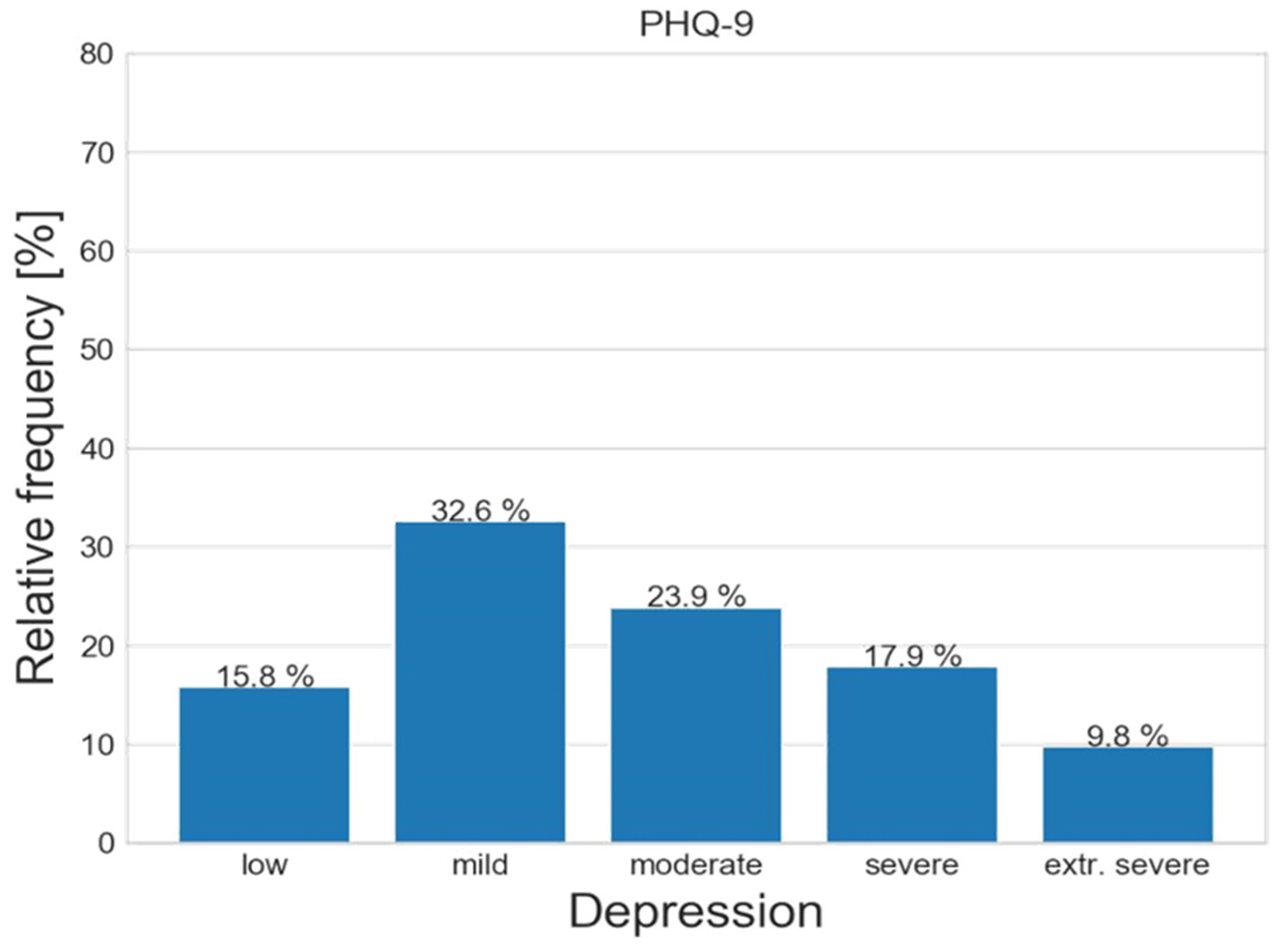

Figure 3 displays PHQ-9 scores: 29 respondents (15.8%) do not display depression, 60 (32.6%) mild depression, 44 (23.9%) moderate, 33 (17.9%) moderately severe and 18 (9.8%) severe.

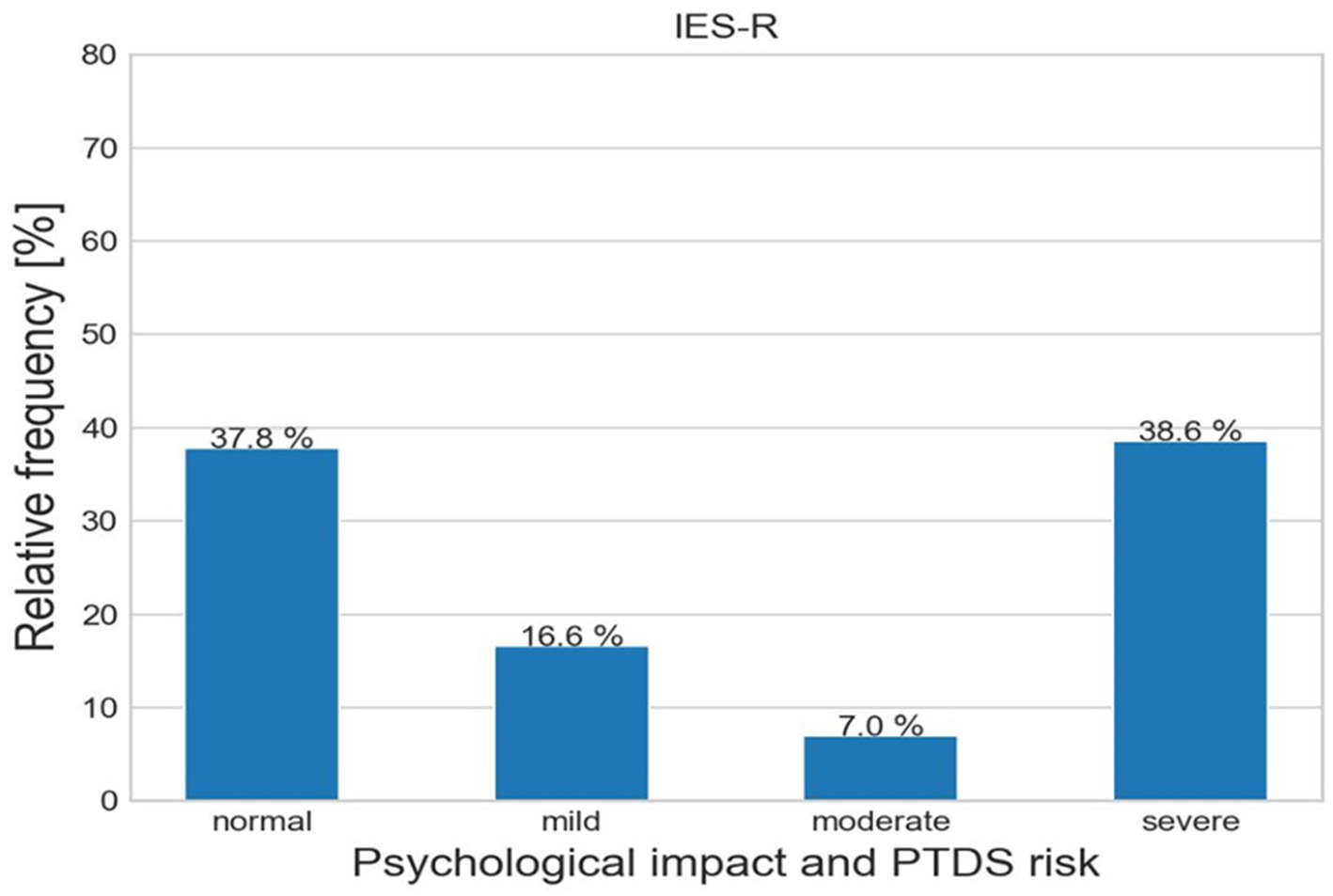

On the IES-R scale (Figure 4), 139 participants (37.8%) are characterized by normal scores, 31 (16.6%) mild psychological impact, 13 (7%) moderate psychological impact and 71 (45.5%) severe psychological impact.

On the MAAS scale, the average score is M = 56.68, SD = 13.82.

For the Brief-COPE Approach scale, the average value is M = 35.89, SD = 5.41, while on the Brief-COPE Avoidant scale the outcome is M = 26.56, SD = 4.51.

3.3 Model results

In line with the previous study, gender significantly affects scores across all six tests (Table 1). The PHQ-9 shows a significant gender difference (F (1,341) = 13.434, p < 0.001), with females scoring higher (M = 10.896, SE = 0.388) than males (M = 8.674, SE = 0.533).

Similarly, the IES-R test reveals gender disparities (F (1,341) = 7.002, p = 0.009), with females scoring higher (M = 34.537, SE = 1.480) than males (M = 28.561, SE = 1.952). In the PSS10, females (M = 23.258, SE = 0.546) outscore males (M = 19.815, SE = 0.730) significantly (F (1,341) = 16.017, p < 0.001).

On the DASS-21 subscales (Table 2), females exhibit higher average scores for Stress (M = 22.323, SE = 0.822), Anxiety (M = 10.046, SE = 0.833), and Depression (M = 18.301, SE = 0.906), with significant differences in groups means (MD = −5.302, p < 0.001; MD = −3.232, p = 0.005; MD = −3.577, p = 0.005), respectively.

Education does not significantly affect IES-R, PSS10, Stress, Anxiety, or Depression DASS-21 scales. However, in the PHQ-9, individuals with a master’s degree or Ph.D. (M = 8.769, SE = 0.512) score lower than those with a bachelor’s degree (M = 10.823, SE = 0.515), showing a significant difference (F (2,341) = 4.579, p = 0.011, MD = 2.055, p = 0.008).

Knowing someone who died from COVID-19 reveals significant differences in PHQ-9 (F (3,341) = 4.676, p = 0.031) and PSS10 (F (1,341) = 4.712, p = 0.031) scores, with lower scores among those acquainted with COVID-19-related deaths. Similarly, on the DASS-21 Depression subscale, a notable difference (F (1,341) = 6.996, p = 0.009; MD = 2.952, p = 0.009) is observed between those acquainted with COVID-19 deaths and those who are not, with lower scores for the former ones. No significant differences are found on the Stress, Anxiety DASS-21 subscales, or the IES-R subscale.

3.4 Use of means of information and communication

Regarding time spent on social networks, no significant differences were observed in the three DASS-21 subscales, IES-, and PSS10 scales. However, on the PHQ-9 scale, individuals spending less than one hour per day (M = 7.126, SE = 0.954) scored significantly lower than those spending one to two hours (MD = −3.359, p = 0.005), two to five hours (MD = −3.585, p = 0.005), and over five hours (MD = −3.693, p = 0.005).

Concerning the time spent on gathering pandemic-related information, a significant difference emerges on the IES-R scale (F (2,341) = 9.623, p < 0.001) and DASS-21 Stress subscale (F (2,341) = 5.654, p = 0.004). Survey participants who spent less time searching for information scored lower on the IES-R scale (M = 25.707, SE = 1.926) compared to those with moderate (MD = −6.938, p = 0.008) and high (MD = −10.588, p < 0.001) information research frequency. Similarly, on the DASS-21 Stress subscale, respondents with a low information-seeking frequency display a lower score (M = 16.844, SE = 1.132) than those with moderate (MD = −3.522, p = 0.026) and high frequency (MD = −4.961, p = 0.006).

3.5 Awareness and coping strategies

Covariances in the model link coping mindful awareness strategies to variations in dependent variables. Low MAAS scores, indicating reduced awareness, significantly associate with high values of PHQ-9, IES-R, PSS10, and DASS-21 Stress and Depression subscales. Further, higher avoidance strategy attitudes (Brief-COPE Avoidant) are related to elevated scores on all scales. Eventually, higher Approach Strategy scores (Brief-COPE Approach) correspond to significantly lower PSS10 and DASS-21 Depression subscale values. These results are reported in Tables 1, 2.

3.6 Comparison of the psychological impact on the survey population in 2020 and 2021

This subsection compares the findings from the initial survey conducted in spring 2020 with those from the follow-up in 2021 using a repeated measures ANCOVA. No significant differences are found between the scores on the three DASS-21 subscales as well as in the PHQ-9 and PSS10 tests for both years.

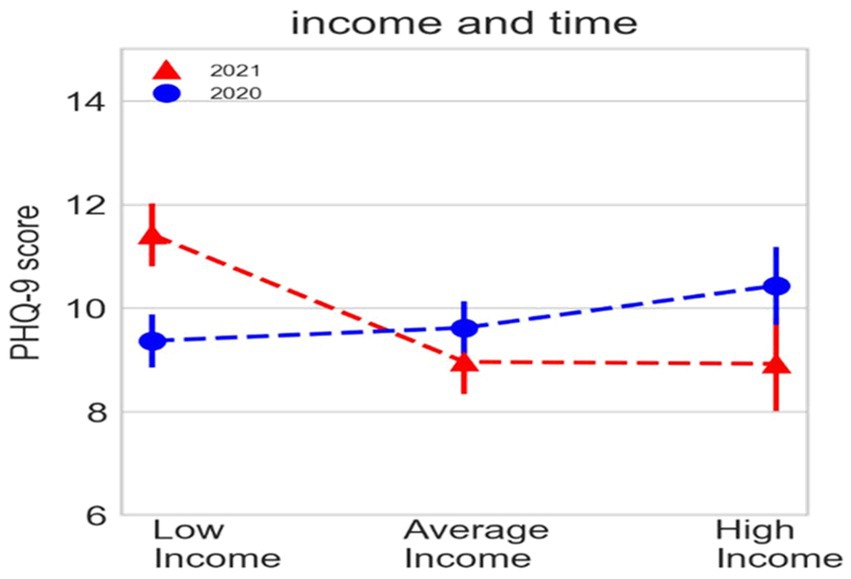

However, a notable difference emerges on the IES-R scale (F (1,341) = 12.255, p = 0.001) as in 2021, participants scored lower (M = 28.836, SE = 1.292) compared to 2020 (M = 34.262, SE = 1.726). Furthermore, a temporal effect is observed in relation to other variables. For example, the PHQ-9 scores are influenced by income in both 2020 and 2021 (Figure 5). In 2020, scores are (M = 9.365, SE = 0.612) for low income, (M = 9.618, SE = 0.623) for medium income, and (M = 10.433, SE = 0.910) for high income, with no significant difference. However, in 2021, the low-income group shows an increase in scores (M = 11.414, SE = 0.511) indicating a significant difference F (2,341) = 6.139, p = 0.002 compared to the average (MD = −2.458, p = 0.001) and high-income (MD = −2.491, p = 0.010) groups, whose scores slightly decrease.

4 Discussion

While limited to Italian respondents, this study underscores the impact of COVID-19 and government containment measures on psychological well-being. The analysis of online questionnaires reveals heightened stress levels in 80 to 86% of the population, while depression rates range from 66 to 85% while anxiety affects around 42% of participants. Furthermore, 62% of the population is at risk of developing PTSD.

It is interesting to note that these results both tend to confirm and provide some additional indications compared to broader systematic reviews conducted in the meantime.

For instance, literature has highlighted an increase in anxiety and depression, particularly in the presence of pre-existing conditions or COVID-19 infections, as well as certain risk factors including female gender, being a nurse/healthcare worker, lower socio-economic status and social isolation. Meanwhile, some protective factors would include the presence of sufficient medical resources as well as up-to-date and accurate information (Luo et al., 2020; Khoodoruth et al., 2021).

Despite some recent long-term studies, it appears that the psychological impact of COVID-19 lockdowns is not as severe and uniform as previously thought, with significant yet relatively small effect sizes for anxiety and depression. Furthermore, some meta-regression analyses did not find significant moderation effects for average age, gender, continent, COVID-19 death rate or days of lockdown. This suggests that the restrictions do not affect everyone’s mental health in the same way, as many individuals seem to display psychological resilience to these impacts (Prati and Mancini, 2021). It appears necessary to delve further into this matter to increase the available data, as current findings sometimes seem contradictory.

Equally, these results align with prior research, highlighting the connection between awareness, coping strategies and psychological outcomes (Main et al., 2011; Passavanti et al., 2021; Smida et al., 2021). Lower scores on the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) correlate with increased stress, anxiety, depression and PTSD risk. Strategic coping approaches correspond to reduced PTSD risk and lower DASS-21 depression subscale scores, whereas avoidance strategies heighten psychopathological risk across various scales.

Gender differences exert a significant role, with females displaying significantly higher scores on subscales, indicating greater exposure to pandemic effects. These findings align with other studies (Li et al., 2020; Wang C. et al., 2020; Wang H. et al., 2020; Khoodoruth et al., 2021) highlighting that the female population is more susceptible to pandemic-related impacts.

Regarding education, a notable difference is observed on the PHQ-9, indicating that individuals with a bachelor’s degree experience higher stress levels than those holding a master’s degree or PhD.

Interestingly, respondents acquainted with someone who died due to COVID-19 exhibit lower scores on both the DASS-21 depression subscale and the PHQ-9 scale, possibly suggesting a degree of acceptance of the global situation. However, those with positive acquaintances displayed higher stress and anxiety levels.

The study also delved into the psychological effects of social media exposure and information retrieval frequency during the pandemic. The results show that individuals spending less than an hour per day on social networks have lower stress levels than those with greater exposure. The same consideration applies to those devoting less free time to pandemic-related information. These results corroborate existing literature emphasizing the psychological impact related to communication and information during crises (Neria and Sullivan, 2011; Roy et al., 2020; Shuja et al., 2020). In this regard, the intervention of institutions and media should aim to inform the general public in a fair and unbiased manner (Chand, 2021; Himelein-Wachowiak et al., 2021).

Throughout the pandemic period, no significant increase in stress, anxiety, or depression is observed among the participants over the eighteen-month timeframe following the outbreak in Italy. However, an elevated risk of PTSD is identified.

Regarding socioeconomic variables and exposure to social media and information, no significant changes are noted, except for a rise in stress levels among the low-income survey population during the second follow-up research. This outcome could be attributed to the Italian government countermeasures, resulting in income and job losses that disproportionately affected the low-income segment of the population. Despite this data being significant in line with what is found in the literature, it is equally important to emphasize how it may be biased due to self-categorization by individuals and their self-perception. For these reasons, it is important to consider it only within the broader context of the research and its limitations.

A worsening of the living standards, unemployment and the lack of career prospects have long been associated to higher stress levels. Similar results were found also in other countries, amongst them the UK (Shevlin et al., 2020) and the USA (Wolfson et al., 2021).

In general, many of the findings of this research echo a good portion of the considerations and outcomes valid for the previous study performed in 2020. In this regard, the time factor seems to exert a very limited impact on psychological distress, although specific results may be affected by the small sample size and various country-specific circumstances. Furthermore, it has been observed in the literature how organizational aspects related to lockdown policies and some precautionary measures, such as hand hygiene and mask-wearing, have an impact on psychopathological symptoms (Wang C. et al., 2020; Wang H. et al., 2020).

Finally, it is important to consider how some variables not considered in this research could be important mediators regarding the reported correlations, for example, the role that the presence of psychological support may have in such a timeframe. Similarly, it is important to note that a significant number of the initial 420 participants dropped out during the follow-up study in this phase, constituting an additional limiting factor that could partially impact the results.

5 Conclusion

This study has delved into the profound psychological distress induced by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures in Italy. Focusing on 184 individuals who participated in two online surveys (one in spring 2020 and a follow-up in winter 2021), this research has pivoted on a longitudinal analysis over eighteen months. The findings have revealed a significant prevalence of heightened stress, depression and anxiety levels, with around 62% of the population at risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), particularly affecting women.

The study has highlighted the interplay between awareness levels, coping strategies and psychological impact. Lower scores on the Mindfulness Awareness Attention Scale (MAAS) correlate with increased stress, anxiety, depression and higher PTSD risk. Likewise, avoidance coping strategies worsen psychopathological risks.

Moreover, continuous exposure to traumatic media content and misinformation has negatively impacted mental well-being. Conversely, individuals who have limited their social media usage to less than an hour per day report lower stress levels.

An increased psychological risk has been observed among low-income participants during the second year of the pandemic. Economic repercussions, income loss and job displacement have contributed to this increment, mirroring similar findings in other countries. Therefore, the findings of this research hold significant implications for mental health interventions and policy development in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Broadly speaking, this investigation has underscored the critical need for tailored mental health interventions aimed at addressing heightened levels of stress, anxiety, depression and the risk of developing PTSD among the population. The prevalence of these psychological challenges, particularly among certain demographic groups such as women and individuals with lower socioeconomic status, has highlighted the importance of targeted intervention strategies.

Furthermore, the findings emphasize the crucial role of coping mechanisms and mindful awareness in mitigating the psychological impact of the pandemic. Interventions that promote effective resilient strategies and mindfulness practices could serve as protective factors against adverse mental health outcomes.

In terms of policy development, the results indicate the importance of ensuring access to accurate and up-to-date information, as well as the responsible use of social media platforms. Regulations aimed at disseminating reliable news and combating misinformation could help alleviate unnecessary stress and anxiety among the population.

Moreover, the outcomes have highlighted the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the most vulnerable groups of the population, such as those with lower income levels. Policy initiatives aimed at addressing socioeconomic disparities and providing support to marginalized communities are crucial for promoting mental well-being and resilience.

This study has underscored the urgent need for comprehensive interventions and evidence-based policy measures to address the psychological toll of COVID-19. By prioritizing mental health support and implementing targeted policies, it is possible to effectively mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic and promote resilience within our societal communities.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Norwegian Centre for Research Data. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

IR: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ML: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. MM: Resources, Writing – original draft. AA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. DB: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

IR was employed by Illedi HNP Srl.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akintunde, T. Y., Musa, T. H., Musa, H. H., Musa, I. H., Chen, S., Ibrahim, E., et al. (2021). Bibliometric analysis of global scientific literature on effects of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. Asian J. Psychiatr. 63:102753. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102753

Bentenuto, A., Mazzoni, N., Giannotti, M., Venuti, P., and de Falco, S. (2021). Psychological impact of Covid-19 pandemic in Italian families of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 109:103840. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103840

Bielecki, M., Patel, D., Hinkelbein, J., Komorowski, M., Kester, J., Ebrahim, S., et al. (2021). Air travel and COVID-19 prevention in the pandemic and peri-pandemic period: a narrative review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 39:101915. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101915

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al., (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Brown, K. W., and Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 822–848. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 4, 92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Chand, A. A. (2021). Abuse of social media during COVID-19 pandemic in Fiji. Int. J. Surg. (London, England) 92:106012. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106012

Chen, Y., Zhang, X., Chen, S., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Lu, Q., et al. (2021). Bibliometric analysis of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 65:102846. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102846

Chew, N., Lee, G., Tan, B., Jing, M., Goh, Y., NJH, N., et al. (2020). A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., and Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24, 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404

Conversano, C., Di Giuseppe, M., Miccoli, M., Ciacchini, R., Gemignani, A., and Orrù, G. (2020). Mindfulness, age and gender as protective factors against psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11:1900. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01900

Creamer, M., Bell, R., and Failla, S. (2003). Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale—revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 41, 1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010

Dawson, D. L., and Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 17, 126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

Dean, D. J., Tso, I. F., Giersch, A., Lee, H. S., Baxter, T., Griffith, T., et al. (2021). Cross-cultural comparisons of psychosocial distress in the USA, South Korea, France, and Hong Kong during the initial phase of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 295:113593. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113593

Gonçalves, A. R., Barcelos, J., Duarte, A. P., Lucchetti, G., Gonçalves, D. R., Silva, E., et al. (2022). Perceptions, feelings, and the routine of older adults during the isolation period caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study in four countries. Aging Ment. Health 26, 911–918. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1891198

Henry, J. D., and Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 44, 227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657

Himelein-Wachowiak, M., Giorgi, S., Devoto, A., Rahman, M., Ungar, L., Schwartz, H. A., et al. (2021). Bots and misinformation spread on social media: implications for COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e26933. doi: 10.2196/26933

Ho, C. S., Chee, C. Y., and Ho, R. C. (2020). Mental Health Strategies to Combat the Psychological Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Beyond Paranoia and Panic. Annals Acad Med. Singapore 49, 155–160

Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Zhao, J., Hu, Y., et al. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

Khoodoruth, M. A. S., Al-Nuaimi, S. K., Al-Salihy, Z., Ghaffar, A., Khoodoruth, W. N. C., and Ouanes, S. (2021). Factors associated with mental health outcomes among medical residents exposed to COVID-19. BJPsych open 7:e52. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.12

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., and Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Li, S., Wang, Y., Xue, J., Zhao, N., and Zhu, T., (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 Epidemic Declaration on Psychological Consequences: a Study on Active Weibo Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 2032. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062032

Luo, M., Guo, L., Yu, M., Jiang, W., and Wang, H. (2020). The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190

Main, A., Zhou, Q., Ma, Y., Luecken, L. J., and Liu, X. (2011). Relations of SARS-related stressors and coping to Chinese college students’ psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic. J. Couns. Psychol. 58, 410–423. doi: 10.1037/a0023632

Meyer, B. (2001). Coping with severe mental illness: relations of the brief COPE with symptoms, functioning, and well-being. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 23, 265–277. doi: 10.1023/A:1012731520781

Moccia, L., Janiri, D., Pepe, M., Dattoli, L., Molinaro, M., De Martin, V., et al. (2020). Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048

Neria, Y., and Sullivan, G. M. (2011). Understanding the mental health effects of indirect exposure to mass trauma through the media. JAMA 306, 1374–1375. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1358

Pakenham, K. I., Landi, G., Boccolini, G., Furlani, A., Grandi, S., and Tossani, E. (2020). The moderating roles of psychological flexibility and inflexibility on the mental health impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Italy. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 17, 109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.003

Passavanti, M., Argentieri, A., Barbieri, D. M., Lou, B., Wijayaratna, K., Foroutan Mirhosseini, A. S., et al. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 and restrictive measures in the world. J. Affect. Disord. 283, 36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.020

Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Odriozola-González, P., Irurtia, M. J., and de Luis-García, R. (2020). Longitudinal evaluation of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 crisis in Spain. J. Affect. Dis. 277, 842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.018

Prati, G., and Mancini, A. D. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 51, 201–211. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000015

Reagu, S., Wadoo, O., Latoo, J., Nelson, D., Ouanes, S., Masoodi, N., et al. (2021). Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic within institutional quarantine and isolation centres and its sociodemographic correlates in Qatar: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 11:e045794. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045794

Romagnani, P., Gnone, G., Guzzi, F., Negrini, S., Guastalla, A., Annunziato, F., et al. (2020). The COVID-19 infection: lessons from the Italian experience. J. Public Health Policy 41, 238–244. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00229-y

Roy, D., Tripathy, S., Kar, S. K., Sharma, N., Verma, S. K., and Kaushal, V. (2020). Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 51:102083. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083

Sharun, K., Tiwari, R., Natesan, S., and Dhama, K. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, associated zoonotic concerns, and importance of the one health approach during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Vet. Q. 41, 50–60. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2020.1867776

Shevlin, M., McBride, O., Murphy, J., Miller, J. G., Hartman, T. K., Levita, L., et al. (2020). Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych open 6:e125. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.109

Shuja, K. H., Aqeel, M., Jaffar, A., and Ahmed, A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and impending global mental health implications. Psychiatr. Danub. 32, 32–35. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2020.32

Smida, M., Khoodoruth, M. A. S., Al-Nuaimi, S. K., Al-Salihy, Z., Ghaffar, A., Khoodoruth, W. N. C., et al. (2021). Coping strategies, optimism, and resilience factors associated with mental health outcomes among medical residents exposed to coronavirus disease 2019 in Qatar. Brain Behav. 11:e2320. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2320

Sohrabi, C., Alsafi, Z., O'Neill, N., Khan, M., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., et al. (2020). World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 76, 71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034

Tee, M. L., Tee, C. A., Anlacan, J. P., Aligam, K., Reyes, P., Kuruchittham, V., et al. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J. Affect. Disord. 277, 379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043

Umucu, E., and Lee, B. (2020). Examining the impact of COVID-19 on stress and coping strategies in individuals with disabilities and chronic conditions. Rehabil. Psychol. 65, 193–198. doi: 10.1037/rep0000328

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., et al. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wang, H., Xia, Q., Xiong, Z., Li, Z., Xiang, W., Yuan, Y., et al. (2020). The psychological distress and coping styles in the early stages of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic in the general mainland Chinese population: a web-based survey. PLoS One 15:e0233410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233410

WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard (2021). Available at: https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed December 27, 2021).

Wolfson, J. A., Garcia, T., and Leung, C. W. (2021). Food insecurity is associated with depression, anxiety, and stress: evidence from the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Equity 5, 64–71. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0059

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L., Gill, H., Phan, L., et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affec. Dis. 277, 55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Yan, L., Gan, Y., Ding, X., Wu, J., and Duan, H. (2021). The relationship between perceived stress and emotional distress during the COVID-19 outbreak: effects of boredom proneness and coping style. J. Anxiety Disord. 77:102328. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102328

Keywords: COVID-19, depression, stress, anxiety, psychological impact

Citation: Ropi I, Lillo M, Malavasi M, Argentieri A, Barbieri A, Lou B, Barbieri DM and Passavanti M (2024) The psychological implications of COVID-19 over the eighteen-month time span following the virus breakout in Italy. Front. Psychol. 15:1363922. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1363922

Edited by:

Khaled Trabelsi, University of Sfax, TunisiaReviewed by:

Faten Salhi, University of Manouba, TunisiaMohamed Adil Shah Khoodoruth, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

Yasodha Rohanachandra, Latrobe Regional Hospital, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Ropi, Lillo, Malavasi, Argentieri, Barbieri, Lou, Barbieri and Passavanti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baowen Lou, YmFvd2VuLmxvdUBudG51Lm5v; Marco Passavanti, cHNpY29sb2dvbWFyY29wYXNzYXZhbnRpMUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Ingrid Ropi

Ingrid Ropi Margherita Lillo

Margherita Lillo Matteo Malavasi3

Matteo Malavasi3