- 1Department of Psychology, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières, QC, Canada

- 2Department of Human Resources Management, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières, QC, Canada

- 3Vulnérabilité, Capabilité et Rétablissement (VCR), Ecole de Psychologues Praticiens of Catholic University of Paris, Paris, France

- 4INSERM INSPIIRE UMR 1319, Lorraine University, Nancy, France

Introduction: The Impostor Phenomenon (IP) refers to a psychological experience characterized by unjustified feelings of intellectual and professional fraud, accompanied by the fear of not maintaining performance and of being exposed. IP is receiving increasing attention in the fields of psychological health at work and occupational psychology as well as among the general public, since it affects the functioning of both individuals and organizations. The aim of this scoping review is to map the range of interventions that have been conducted to address IP among individuals experiencing it in a professional context.

Methods: The search and selection process to identify relevant reports was conducted using the PRISMA-ScR methodology and JBI recommendations and resulted in the selection of 31 studies.

Results: The results reported concerning the characteristics of the studies, the interventions described, and the effects identified are heterogeneous. More than half of the studies used research designs (experimental, pre-experimental, exploratory, etc.). Two major types of intervention emerge: training and counseling. The effectiveness of the interventions varies according to the evaluation methodology that was used, although most authors conclude that the proposed intervention is relevant.

Discussion: In light of these results, recognizing and educating individuals regarding the various manifestations of IP, as well as offering support in a group context, appear to be primary intervention levers. Future intervention proposals should explore psychosocial and educational influences as well as the impact of the immediate environment on IP-related beliefs.

Introduction

Since its emergence in the late 1970s (Clance and Imes, 1978), the concept of impostor phenomenon (IP) is drawing increasing scientific interest and gaining popularity among the general public. It is characterized by an intense and secret psychological experience of intellectual and professional fraud (e.g., Clance and Imes, 1978; Harvey and Katz, 1985). These unjustified feelings of phoniness in the face of success, known as impostor feelings, are accompanied by the fear of not being able to reproduce one’s performance and the fear of being discovered (Clance and Imes, 1978; Clance, 1985). IP seems to be a common experience, as Tewfik (2022) pointed out, “may unwittingly come from common work experiences such as a promotion in which one is suddenly expected to successfully execute unfamiliar responsibilities” (p. 992). Moreover, going through a major life transition or acquiring a new role, in a professional or a private context, can put individuals at risk of developing IP (Harvey, 1981; Fujie, 2010). IP can also be considered a vicious circle, where each repetition reinforces the dysfunctional beliefs and associated negative feelings (e.g., Clance and Imes, 1978; Clance, 1985; Chrisman et al., 1995). With the exception of rare positive accounts (Fruhan, 2002; McElwee and Yurak, 2010; Tewfik, 2022), the expression of the IP is considered to be very detrimental to health and wellbeing at work (e.g., Vergauwe et al., 2015) and, consequently, to the proper functioning of organizations (e.g., Kets de Vries, 2005). Addressing IP seems to be a significant lever of action for organizations wishing to promote good health at work, and employee fulfillment and performance. Yet, as revealed by the systematic review by Bravata et al. (2020), treatments for IP have been little studied to date. To fill this gap, this review examines interventions to address IP and proposes a benchmark for future contributions to this field of research.

To better understand its objectives, it is worth mentioning the broader context of current knowledge about IP. First of all, data on the prevalence of IP within the population vary widely, from 9% to 82%, depending on the psychometric instrument and cut-off score (Bravata et al., 2020). It is generally associated with a decrease in wellbeing and life satisfaction (Clance and O’Toole, 1987; September et al., 2001). Furthermore, IP can affect individuals’ psychological health in various ways (e.g., Bernard et al., 2002; Brauer and Wolf, 2016). Indeed, it predicts up to 15% of self-reported psychological distress (Oriel et al., 2004). The most frequently associated comorbidities are depression (e.g., Oriel et al., 2004; Leonhardt et al., 2017), anxiety (e.g., Bernard et al., 2002; Kananifar et al., 2015) low self-esteem (Neureiter and Traut-Mattausch, 2016), and somatic symptoms and social dysfunction (Kananifar et al., 2015). Moreover, IP is now considered by many experts to be a psychopathological reality (e.g., Chassangre, 2016) and some researchers have suggested that it should be included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (Bravata et al., 2020).

Observational studies of IP in a work context have been carried out in various fields, such as academia (e.g., Clance and Imes, 1978; Byrnes and Lester, 1995), healthcare (e.g., Ares, 2018; LaDonna et al., 2018), marketing (e.g., Fried-Buchalter, 1997), and management (Rohrmann et al., 2016). In professional context, IP is generally associated with reduced job satisfaction (Vergauwe et al., 2015). Studies have demonstrated its link with stress (e.g., Rohrmann et al., 2016; Alrayyes et al., 2020), burn-out (e.g., Legassie et al., 2008; Vergauwe et al., 2015), and emotional exhaustion (Leach et al., 2019). Furthermore, IP is known to negatively affect work-life balance (Crawford et al., 2016) and it is positively related to workaholism (Mir and Kamal, 2018), suggesting that persons who experience IP are more likely to work harder and longer, in order to avoid their fear of failure. In addition, it can often become an obstacle to career progression and the motivation to take on a leadership role (Neureiter and Traut-Mattausch, 2016, 2017). It can also influence decisions about whether to continue in an educational program or a career (e.g., Clance and O’Toole, 1987; Blondeau and Awad, 2018). Moreover, IP is usually known to lead to maladaptive organizational behaviors (e.g., Bechtoldt, 2015; Neureiter and Traut-Mattausch, 2016). More recently, Tewfik (2022) has nuanced this observation by demonstrating that those who experience IP were evaluated as more interpersonally effective. What is more, this relational efficiency does not come at the expense of competence-related outcomes. IP is also known as a factor influencing absenteeism and turnover in companies (Kets de Vries, 2005). However, organizational functioning and managerial attitudes can mitigate the deleterious effects of IP (e.g., Bechtoldt, 2015; Crawford et al., 2016).

That being said, an important aspect of the theoretical background is the lack of conceptual clarity regarding IP and the persistent discussion over the nature of the construct. Beyond the lack of uniformity in the terms used to designate it (sometimes a phenomenon, a syndrome, impostorism, an experience, a feeling, thoughts, etc.), a lack of consensus remains on its consideration as a trait or a state (Gullifor et al., 2023) or on the dimensionality of the phenomenon (Mak et al., 2019). Indeed, IP was described by early authors as a cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dynamic (Clance, 1985), corresponding to a list of intrapersonal criteria (Clance, 1985; Harvey and Katz, 1985). If, for many years, it was perceived as a stable personality trait (e.g., Topping, 1983; Sonnak and Towell, 2001), it was later seen as an affective state that could manifest itself in certain situations (e.g., Leary et al., 2000; McElwee and Yurak, 2007); a psychological experience according to McElwee and Yurak (2010). Since then, this aspect of the discussion has not really been elucidated, as Gullifor et al. (2023) pointed out. In response to this issue, these authors proposed a trait–state conceptualization of IP. On the other hand, Mak et al. (2019), in a systematic review of IP measurement scales, identify that the lack of conceptual clarity around the dimensionality of the IP has limited the establishment of a gold standard measure.

Despite these critical gaps in the scientific literature, which are legitimately deplored by the authors of systematic reviews on the subject (Mak et al., 2019; Bravata et al., 2020; Gullifor et al., 2023), the field of research of the interventions addressing IP is, quite recently, expanding. According to recent perspectives (e.g., Kark et al., 2022), IP presents as a psycho-social issue that affects the psychological health, wellbeing, and careers of individuals. These findings justify a scoping review, to support both current intervention approaches and the development of future research in this field. A scoping review is particularly relevant to the topic of interventions addressing IP given that the subject is emergent and has not been extensively reviewed. Like systematic reviews, scoping reviews follow a rigorous, systematic literature search and identification process; however, they are more exploratory in nature (Colquhoun et al., 2014; Lockwood and Tricco, 2020).

Therefore, the aim of this scoping review is to provide a more comprehensive overview of the research landscape, map the range of interventions that have been conducted to address IP among individuals experiencing it in a professional context, which is currently unavailable in the literature. In line with this objective, it addresses the following questions: (1) What types of studies and methodologies have been undertaken to explore interventions addressing IP expressed in occupational contexts? (2) What are the modalities and characteristics of these interventions? and (3) What are the effects of these interventions?

Method

This scoping review uses a systematic approach to analyze and aggregate scientific data on a given topic to identify concepts, theories, sources, and gaps associated with current knowledge (e.g., Munn et al., 2018; Tricco et al., 2018, 2022). However, unlike a systematic review, a scoping review must examine all relevant literature, regardless of the study design. This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (2018) guidelines and the recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) (2020). PRISMA-ScR Check List is presented as Supplementary Table 2.

Framing elements were defined to guide the identification and selection of references. These elements concern: (1) the target population of adults in a professional context (such as employees, managers, self-employed workers, but also student trainees and interns), (2) the concept of interventions to address IP, and (3) the organizational, training or private context of these interventions.

Search and selection process of references

Search terms and sources

Relevant references were identified using an iterative process, initiated in November 2022, supported by a librarian specialized in database selection, keyword identification, equation development and search strategy. This approach was then refined in light of the initial results.

Six databases covering psychological, medical, and business literature were selected: APA PsycArticles, APA PsycINFO (EBSCO), Business Source Complete (EBSCO), PubPsych, Scopus, and MEDLINE. The search equation was developed by combining impostor phenomenon (IP) keywords and treatment terms. In the literature, the terms Impostor Syndrome (IS) and Impostor Phenomenon (IP) are synonymous. Other less common terms, such as Impostor Experience, Fraud Syndrome, and Impostorism, were also included. These terms were associated with the keywords Treatment, Intervention, Therapy, Counseling, Rehabilitation, and Management.

The database search identified a total of 394 references. It was subsequently completed by a manual search and consultation of the reference lists, which identified a further 14 references. As an example, the search strategy for APA PsycInfo is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Selection of references

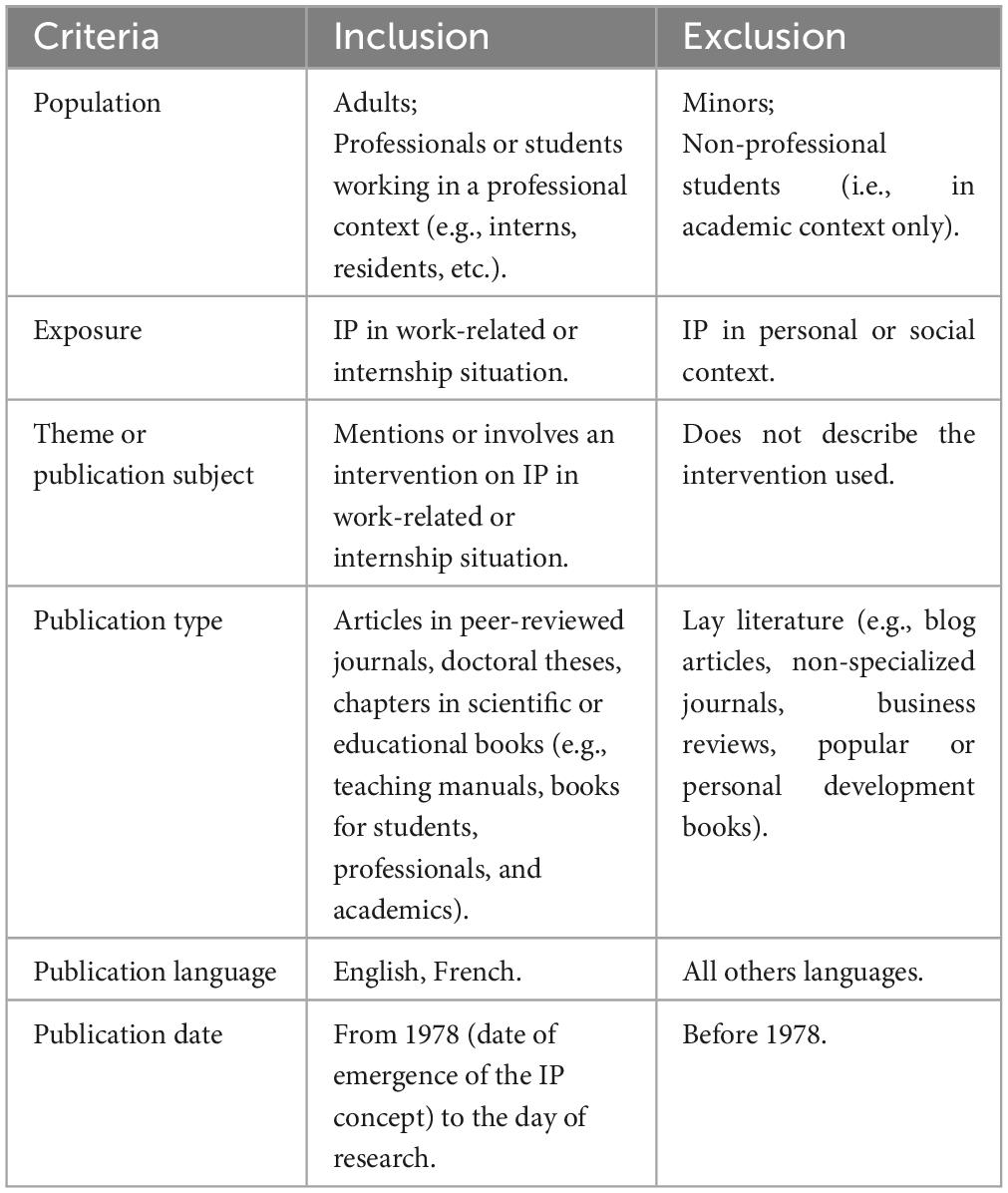

The selection of references was based on predetermined eligibility criteria (Table 1).

According to the JBI, the broad scope of scoping reviews allows for “less restrictive inclusion criteria” (Peters et al., 2015, p. 7) and may draw upon data from any type of evidence and research methodology (Peters et al., 2020). Furthermore, based on the defined objectives and framing elements, the definition of inclusion criteria (in terms of dates, diversity of sources and types of methodology) ensured broad coverage of all the literature relevant to this scoping review; including exploratory, prescriptive, and non-experimental scientific literature. In addition, although this research falls within the field of organizational psychology, it was decided to include studies involving students; as long as they are in internship situations, which utilize their skills as future professionals rather than strictly academic competencies. Exclusion criteria were defined to eliminate references that would not have pertinently addressed the questions raised by this scoping review (e.g., excluding studies focusing on children, references without any interventions, etc.).

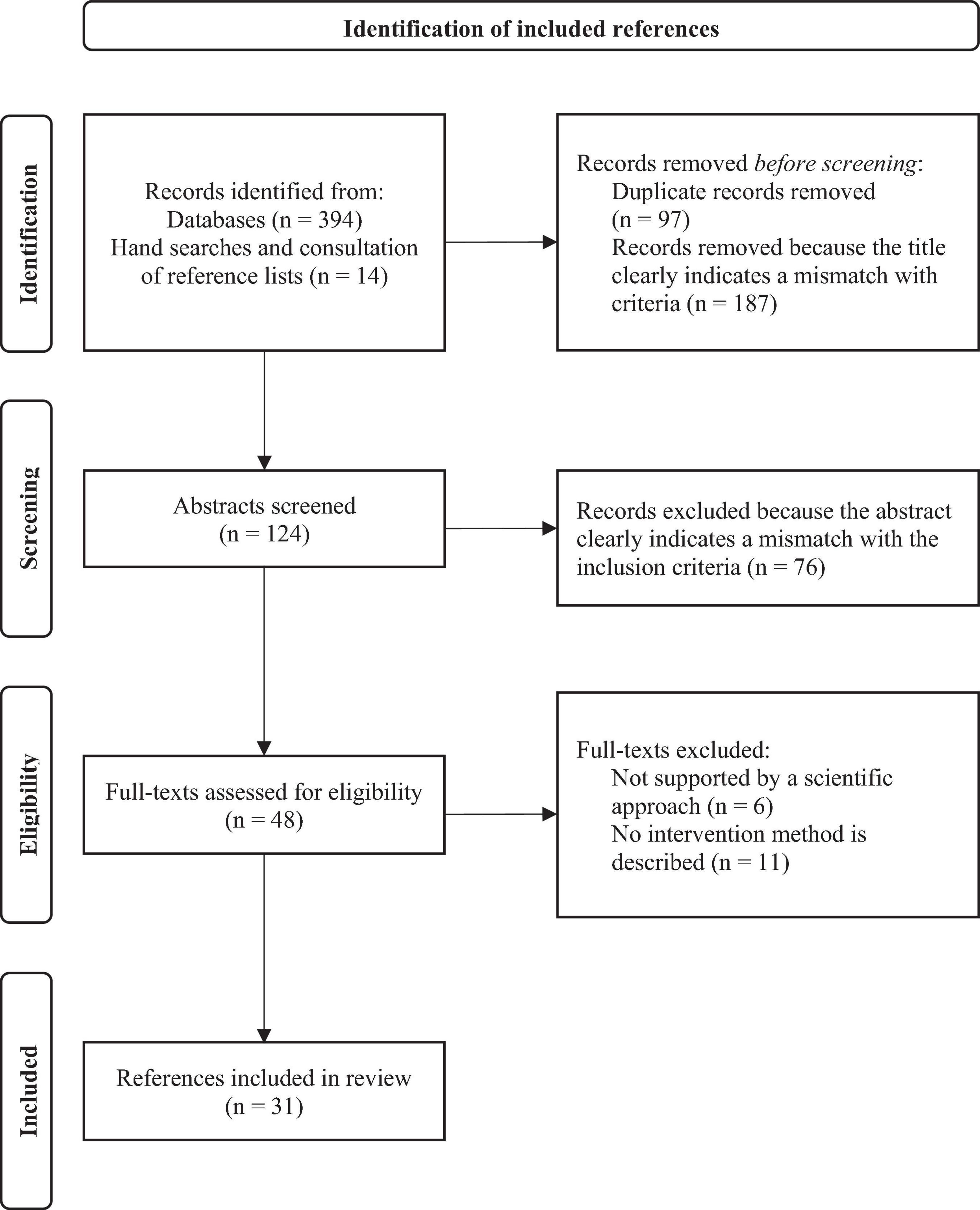

After deleting duplicates, the titles and abstracts of all references were examined for relevance. Those that clearly did not meet the criteria were eliminated. Two reviewers then applied these criteria to all the abstracts retained after the first selection (n = 124), and then to the full texts (n = 48) to determine their eligibility. In the end, 31 publications were retained. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram.

Data extraction

The information and characteristics of the selected references were extracted using a coding grid. They included title, authors, geographical origin, year and type of publication, study objectives, study population and sample size (if applicable), participant characteristics, methodology, measures used, type of intervention, results of analyses, and finally, limitations and main conclusions.

Results

General overview

Of the 31 references on IP interventions selected, 26 are scientific articles from peer-reviewed journals, with a wide range of contents and formats; 4 are chapters in scientific or professional books and 1 is a doctoral thesis.

The interventions presented in these documents vary depending on the context of the studies. First, most interventions were conducted in Europe or the United States (over 80%). Second, the majority of the interventions were deployed in the healthcare and higher education (university) sectors, among participants reporting IP in relation to their professional activities.

Regarding the characteristics of the participants, most of the interventions were carried out with a sample of participants composed primarily of women. Some even specifically targeted professional women (e.g., Mann et al., 2023). Moreover, in half the studies, the average age of participants was under 40 years. In addition, the fact that the participants were young professionals was sometimes reported as an important aspect (e.g., Harte and McGlade, 2018; Danhauer et al., 2019; Baumann et al., 2020). However, not all authors reported the age of participants (e.g., Deshmukh et al., 2022).

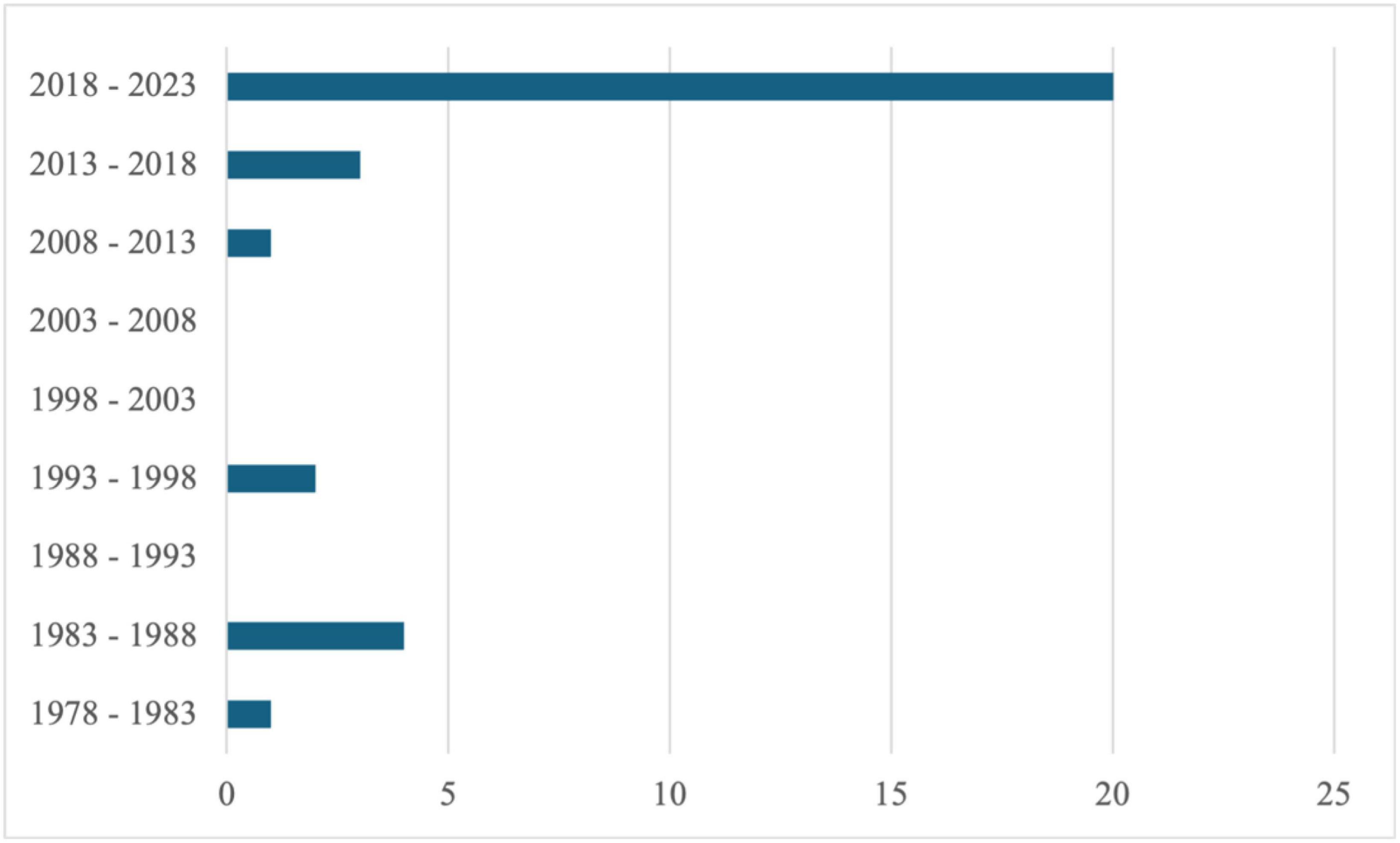

In terms of temporal landmarks, it is very interesting to observe that the field of research on interventions addressing IP is recently in full expansion. This is even more true when considering only studies based on a research design (all post-2018). Figure 2 presents the number of publications related to IP interventions over the years. This observation constitutes an additional argument in favor of proposing a synthesis of existing data and gaps in the current literature.

Figure 2. Number of publications related to interventions addressing IP between 1978 and 2023 (October).

Considering the great heterogeneity of the selected references and to clearly report the results, as well as to be able to make consistent comparisons between types of intervention, the decision was made to split the references into two categories. The objective of splitting the references into two categories is to facilitate the distinction between both and to help the readers further discern the conclusions drawn from these two types of literature. The results from these two types of literature are thus presented separately below.

Studies carried out using a research design

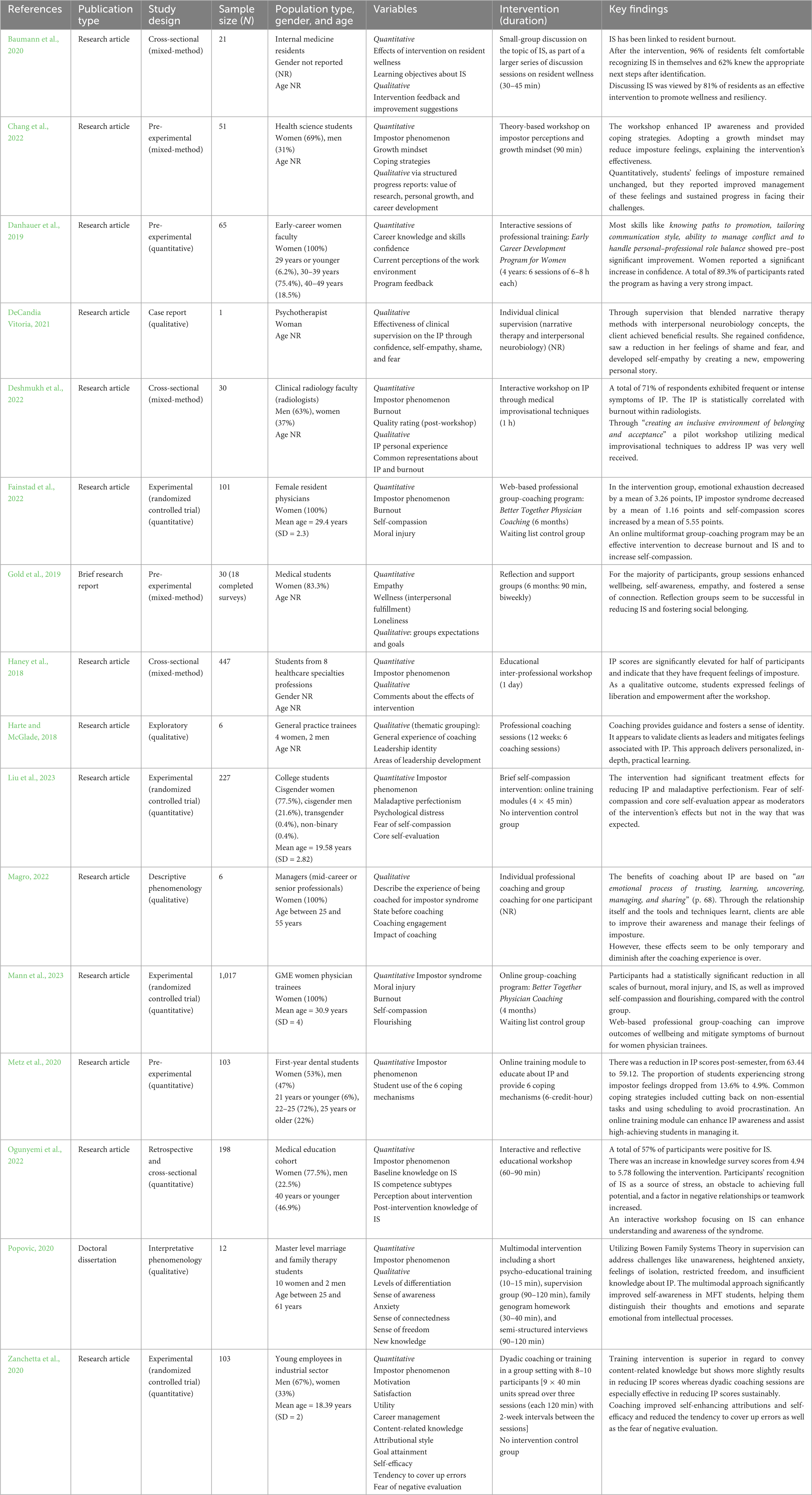

Table 2 presents references describing an intervention tested using a scientific research design.

Study characteristics

Different research designs were used to guide each study. The main characteristics of the studies are reported in Table 3.

The robustness of the study design varied widely from one study to another. Only a few studies involved a randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of their interventions with a control group (i.e., no intervention or a waiting list) (Zanchetta et al., 2020; Fainstad et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023; Mann et al., 2023). Most other studies measured the variables before and after the intervention. Three studies used a cross-sectional design (Haney et al., 2018; Baumann et al., 2020; Deshmukh et al., 2022) and also collected qualitative data on the interventions (e.g., feedback). Finally, two studies used a descriptive (Magro, 2022) or interpretative (Popovic, 2020) phenomenological approach. Regarding sample size, there is considerable variability. For example, the study by Mann et al. (2023) includes more than a thousand participants while DeCandia Vitoria (2021) study presents a case study.

The research objectives formulated in each study also contributed to the heterogeneity between them. While several specifically addressed IP and evaluated the effects of the proposed intervention (e.g., Zanchetta et al., 2020), others situated their objectives within a broader framework (e.g., Fainstad et al., 2022; Mann et al., 2023). It should be noted that very few studies examined the IP issue in isolation: most evaluated several variables simultaneously.

Intervention characteristics

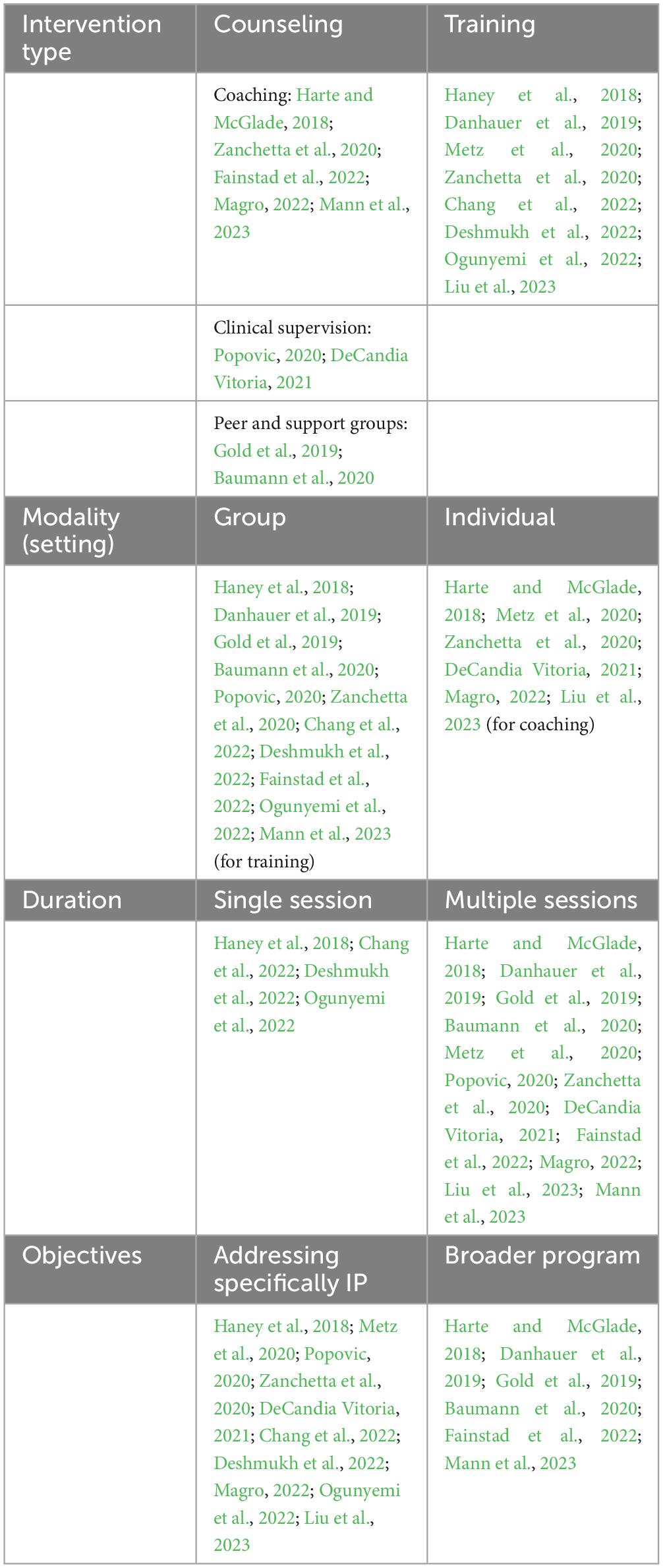

Although intervention models varied from one study to another, common characteristics make it possible to identify trends (Table 4).

First, two major types of approaches emerge among these models. More specifically, half the interventions were based on practices carried out in the context of counseling. These included coaching interventions, clinical supervision, and support groups. Additionally, almost all the other interventions adopted a professional training approach. Only one study (Zanchetta et al., 2020) compared two types of intervention (individual coaching and group training).

Several interventions based on principles of counseling aimed to foster openness and sharing of experiences among peers, in order to break the sense of isolation that characterizes IP. This is particularly true of the reflection and support groups studied by Gold et al. (2019) and the small group discussion sessions offered by Baumann et al. (2020). In the field of supervision, DeCandia Vitoria (2021) adopted an approach defined by simultaneous use of narrative therapy and interpersonal neurobiology. In her study, Popovic (2020) combined psychoeducation with group supervision and individual exercises. Finally, coaching interventions most often addressed the behavioral, cognitive, and emotional aspects of IP. These interventions are based on the coaching alliance, especially in the case of an individual approach (Zanchetta et al., 2020; Magro, 2022).

Training courses are essentially aimed at enhancing knowledge, interpersonal skills or know-how. Some of the selected studies involved purely technical skills related to the activity (e.g., medical improvisational techniques, Deshmukh et al., 2022), others more cross-disciplinary or relational skills (e.g., adapting communication style, managing conflicts, etc., Danhauer et al., 2019). The intervention proposed by Metz et al. (2020) consisted of an online training module on IP presenting more appropriate coping mechanisms. Some training sessions took the form of participative and reflective pedagogical workshops (e.g., Haney et al., 2018; Ogunyemi et al., 2022), with the goal of promoting feelings of liberation and empowerment.

Interventions can also be distinguished based on whether they involve group or individual modalities. While most of the selected studies trended toward group interventions, some were individual. Duration of the interventions, which was highly variable, is another characteristic differentiating the studies. Duration ranged from a single 1-h session (e.g., Deshmukh et al., 2022) to several months (e.g., Mann et al., 2023). Nevertheless, most interventions involved multiple sessions. Finally, some interventions were also part of a broader program, while others focused specifically on the IP.

Characteristics of identified effects

Although most studies concluded that the proposed intervention was effective in treating IP, these conclusions were based on evidence that varied from study to study. Indeed, the type of design and the nature of the data collected undeniably influenced the effects identified and conclusions. A distinction can be drawn between the main effects reported by studies that collected quantitative data, using an experimental or pre-experimental design (pre-intervention and post-intervention measures), and the effects identified by studies that reported qualitative data.

Among the studies that based their conclusions on quantitative data, some compared an experimental condition with a control condition. In a randomized controlled trial, they demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed intervention compared to the absence of intervention. For example, after 6 months of professional coaching intervention, Fainstad et al. (2022) found a significant reduction in IP in female participants compared to those in the control group. The study by Zanchetta et al. (2020) compared two experimental conditions (training and coaching) and a control condition. It highlighted the lasting effectiveness of a coaching intervention in reducing IP issues. These authors concluded that training was less effective than coaching in reducing IP issues but was superior for acquiring associated knowledge. Other studies analyzed the variations in scores obtained by participants before and after the intervention, without comparison with a control group. For example, Metz et al. (2020) reported the beneficial effects of their online training module, as evidenced by a significant decrease in scores on the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS) at the end of the semester, 4 months after their intervention.

Studies that reported qualitative data on the effects of interventions revealed complementary information. Some presented evaluations related to the satisfaction or experience of the participants, which were usually favorable or very favorable (e.g., Danhauer et al., 2019, Baumann et al., 2020; Deshmukh et al., 2022). This positive outcome led the authors to conclude that their intervention adequately addressed the issues. For example, participants in the intervention conducted and evaluated by Gold et al. (2019) reported that it contributed to improving their wellbeing, self-awareness, and empathy skills. Similarly, according to Haney et al. (2018), their training achieved its objectives, as the participants expressed feelings of liberation and empowerment after the workshop.

Finally, exploratory studies, whether descriptive phenomenology or case studies, clearly illustrate the mechanisms on which interventions rely to promote the reduction of IP, which they do not otherwise measure. Thus, Harte and McGlade (2018) concluded that coaching helped give direction and meaning to individual experience, which in turn helped counteract feelings of imposture. Magro (2022), pointed to the counseling and the tools and techniques learned, which enabled clients to improve their awareness and manage their feelings of imposture. Similarly, the clinical supervision proposed by DeCandia Vitoria (2021) to a therapist seemed to enable her to regain confidence, reduce her feelings of shame and fear, and strengthen her self-empathy.

Studies carried out without a research design

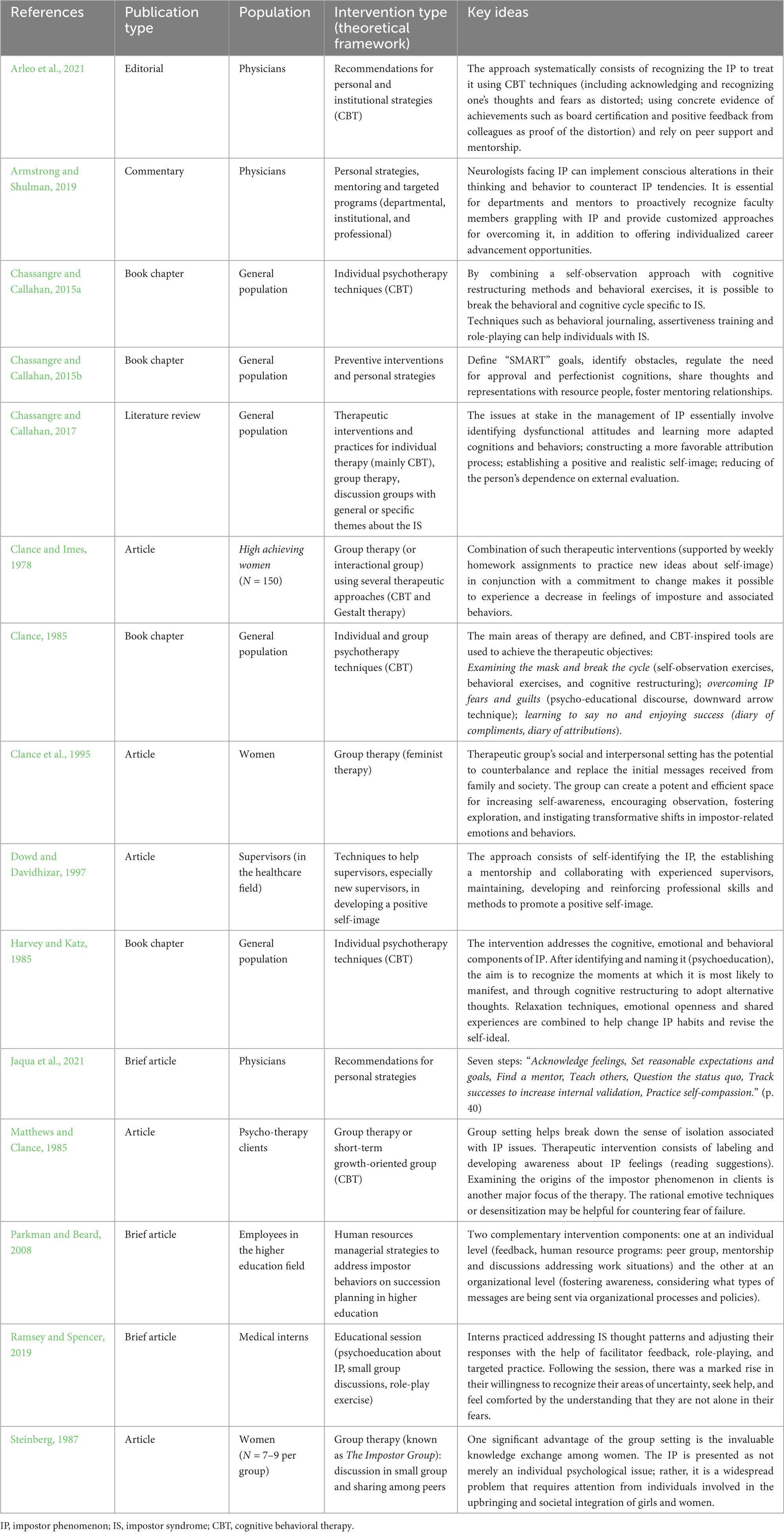

Table 5 includes references presenting interventions carried out without a research design.

Study characteristics

Most of the references classified in this section are articles published in peer-reviewed journals and describe various intervention models carried out in diverse contexts (Clance and Imes, 1978; Matthews and Clance, 1985; Steinberg, 1987; Clance et al., 1995; Parkman and Beard, 2008; Ramsey and Spencer, 2019). These articles present a description of the IP, the intervention carried out and its repercussions, as well as recommendations for practitioners wishing to develop a similar approach. However, the interventions described were neither carried out nor evaluated using a research design. Most often, neither the IP nor other variables were measured. These articles therefore present a professional view of IP interventions, outside the field of empirically based interventions. Therefore, the results reported cannot be compared to those obtained by the studies reported in the previous section. However, it is important to present them in order to better understand the current state of knowledge regarding IP interventions.

Among the selected references, one literature review (Chassangre and Callahan, 2017) and one commentary (Armstrong and Shulman, 2019) address general aspects and list guidelines as well as recommendations for interventions addressing IP. Three others provide scientifically supported recommendations, but their implementation is not described (Dowd and Davidhizar, 1997; Arleo et al., 2021; Jaqua et al., 2021). In addition, this section includes a chapter from Clance (1985) and one from Harvey and Katz (1985), pioneering authors on the subject of IP. These authors present interventions and recommendations based on their clinical experience. Similarly, the two chapters from the work of Chassangre and Callahan (2015a,b) synthesize the contributions of the previous authors and integrate them into their proposed intervention on IP, within the psychotherapeutic framework.

Intervention characteristics

In the references identified, two main types of interventions can be distinguished, those focusing on psychotherapy and those making recommendations for personal strategies.

Most of the interventions described fall within the field of psychotherapy and include both group therapy (Clance and Imes, 1978; Matthews and Clance, 1985; Steinberg, 1987; Clance et al., 1995) and individual interventions (Harvey and Katz, 1985; Dowd and Davidhizar, 1997; Chassangre and Callahan, 2015a,b). Some authors also make recommendations for both modes of intervention (Clance, 1985; Chassangre and Callahan, 2017). In terms of theoretical framework, several references adopt an approach derived from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (Clance, 1985; Harvey and Katz, 1985; Matthews and Clance, 1985; Chassangre and Callahan, 2015a,b, 2017). For example, Clance and Imes (1978) proposed an intervention integrating the contributions of CBT and Gestalt therapy. A few years later, Clance et al. (1995) suggested a feminist-oriented therapeutic group. An intervention put forward by Ramsey and Spencer (2019) resembles training, but also integrates some aspects of counseling, combining a psychoeducational component focusing on IP with small-group discussions and role-playing exercises.

Articles recommending interventions based on personal strategies to reduce IP also address the cognitive, emotional and behavioral components of the phenomenon (e.g., Chassangre and Callahan, 2015a; Arleo et al., 2021; Jaqua et al., 2021). Among these recommendations, it is interesting to note that the approaches described have much in common with each other, but also with coaching (e.g., Zanchetta et al., 2020). For example, Jaqua et al. (2021) describe a seven-step counseling approach that involves acknowledging one’s own feelings and practicing self-compassion, yet also recommend finding a mentor in order to be able to rely on external resources. Overall, these interventions are more briefly described than those based on psychotherapy.

Characteristics of identified effects

Most studies conducted without a research design offer a relatively brief description of the impact of interventions on participants. The effects described are exclusively qualitative in nature, or are estimates of expected effects, according to the clinical or professional experience of the authors. Nevertheless, the information is sufficiently complete to enable several observations.

Firstly, authors who have opted for a group intervention approach argue that it can help break the feeling of isolation often experienced with IP (e.g., Matthews and Clance, 1985). In this regard, Clance et al. (1995) suggest that their feminist-oriented therapeutic intervention makes it possible to counteract and substitute the familial and social influences initially received. Steinberg (1987) describes a peer discussion group (The Impostor Group) and identifies the sharing of knowledge and experiences as one of the main strengths of the intervention. However, individual support may also be indicated in certain cases, as described by Matthews and Clance (1985), offering an opportunity to personalize the treatment of IP. Finally, some researchers suggest that training-based interventions enable the transmission of IP-related knowledge and its subsequent reevaluation on a personal level. For example, Ramsey and Spencer (2019) emphasize that their intervention enables participants to recognize their knowledge gaps more serenely and to seek help without concealing their feelings of imposture.

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review, which situates the contribution of 31 references, is to address three main questions arising from the literature on interventions for IP. The first concerns the types of studies and methodologies that currently exist regarding such interventions. The second focuses on the modalities and characteristics of these interventions, and the third concerns their effects. These three questions are discussed below, followed by the limitations of this review and future perspectives for this field of research.

Type of studies and methodologies

Most of the references included in this scoping review are articles in peer-reviewed journals. However, not all present a scientific investigative approach. Those supported by a scientific research design are from after 2018, and used various methodologies. A majority proposed a quantitative design (e.g., Danhauer et al., 2019), while others relied on mixed or purely qualitative data (e.g., Haney et al., 2018). Research design robustness varied across studies: some presented randomized controlled trials (e.g., Fainstad et al., 2022) while others adopted exploratory approaches (e.g., Magro, 2022). Sample sizes also varied, ranging from individual case (e.g., DeCandia Vitoria, 2021) to studies including over a thousand participants (e.g., Mann et al., 2023).

That said, many of the interventions cited were conducted without the aid of a scientific research design. For example, some articles described professional experiments (e.g., Clance and Imes, 1978). Such interventions cannot be considered as evidence-based practices and are more exploratory in nature. However, the methodological recommendations for scoping reviews, unlike systematic reviews, make it possible to include these publications. In addition to the recent developments identified in this scoping review, this may also explain some of the differences found with the most recent published systematic reviews on IP (Bravata et al., 2020; Gullifor et al., 2023). Thus, it is appropriate to be cautious when extracting the best practices from this literature to guide the development of future interventions.

Modalities and characteristics of interventions

Before discussing the intervention characteristics, it is important to note that most authors agreed on a common definition of IP, one that is consistent with its original conceptualization (e.g., Clance and Imes, 1978; Clance, 1985). Indeed, the definition of IP is not discussed in most of the studies selected, despite the persistent lack of conceptual clarity relating to IP. This observation echoes that of Gullifor et al. (2023) when challenging “the implicit assumption that the conceptualization of IP is thoroughly and soundly developed” (p. 2).

In fact, according to the authors, IP manifests on several levels: cognitive, emotional, and behavioral. Many interventions, whether psychotherapeutic or non-psychotherapeutic, take a CBT-inspired approach to address IP (e.g., Clance, 1985; Chassangre and Callahan, 2017; Gold et al., 2019). In particular, Chassangre and Callahan’s (2015a) interventions draw on intervention techniques described by Clance (1985) (e.g., Attribution Diary, Downward Arrow Technique, etc.), to influence the dynamics of the impostor cycle. Baumann et al. (2020) also point to the influence of CBT in their approach to IP discussion groups. However, interventions based on other conceptual frameworks, such as positive psychology (Fainstad et al., 2022; Mann et al., 2023), narrative therapy and interpersonal biology (DeCandia Vitoria, 2021) or Gestalt (Clance and Imes, 1978), offer another perspective on the beliefs underlying IP (e.g., representations of success, professional skills, beliefs about one’s own abilities, etc.). They also suggest behavioral coping strategies, such as techniques to prevent procrastination (e.g., Metz et al., 2020).

Furthermore, pioneering authors (Clance and Imes, 1978; Clance, 1985; Clance et al., 1995) considered IP to be a psycho-social and interpersonal problem. They emphasized the influence of social norms and stereotypes on the emergence of feelings of imposture, particularly among women. For this reason, Clance et al. (1995) proposed a group therapy approach aimed at overcoming the intrapsychic and sociocultural determinants that can lead to the development and maintenance of impostor feelings. IP continues to be viewed as partly a social and collective phenomenon rather than a strictly individual issue in some recent research (e.g., Haney et al., 2018; Baumann et al., 2020; Popovic, 2020; Arleo et al., 2021). Many interventions thus account for the role played by the social dimension of the work environment (e.g., Danhauer et al., 2019; Gold et al., 2019; Deshmukh et al., 2022) and aim to break the sense of isolation associated with IP. Although some authors opt for an individual approach (e.g., Harte and McGlade, 2018; Metz et al., 2020; DeCandia Vitoria, 2021); according to Steinberg (1987), Parkman and Beard (2008), and Armstrong and Shulman (2019), IP is systemic in nature and therefore needs to be addressed at the organizational or social level. It may therefore be relevant to address it within educational programs, integration strategies, and human resource management policies. This is consistent with recent theoretical developments on IP at work, which suggests that it may emerge from the social context (e.g., Kark et al., 2022).

Finally, it should be noted that two main intervention modalities appear: those based on discussion and counseling, and those focused on training. Most approaches incorporate a psycho-educational component, either provided by the facilitator (e.g., Haney et al., 2018; Ogunyemi et al., 2022), or through suggested readings (Matthews and Clance, 1985; Steinberg, 1987). Role-playing is a technique frequently mentioned in this context and can encourage the expression of feelings as well as regulation of IP manifestations (e.g., Ramsey and Spencer, 2019; Deshmukh et al., 2022).

Following these observations, intervention methods such as training or counseling seem to be the most popular, as are group-based interventions. The transmission of IP-related knowledge emerges as a trend to be retained as a good practice for interventions. Futures research should also clarify the conceptualization they adopt regarding IP.

Effects of interventions

As mentioned above, the impact of the interventions described differs according to the type of intervention and design used. In this section, the effects reported by interventions based on counseling and training, as well as the effects of more specific intervention modalities (e.g., role-playing), are discussed separately.

Among interventions based on counseling, coaching is repeatedly presented as being effective, as are peer exchange and support groups (e.g., Harte and McGlade, 2018; Baumann et al., 2020; Mann et al., 2023). These interventions seem to promote openness and awareness. They also encourage effort at the level of mentalization, as much as the concrete implementation of coping strategies (e.g., Harte and McGlade, 2018; Magro, 2022). Furthermore, in a group context, the impact of the facilitator’s counseling with participants seems to be amplified by the relationships among the participants themselves (e.g., Steinberg, 1987; Baumann et al., 2020; Fainstad et al., 2022). More specifically, this type of intervention can foster connection and a sense of social belonging (Gold et al., 2019).

Training-based interventions are relevant for knowledge transmission. Several studies have shown a post-intervention increase in IP-related knowledge (e.g., Deshmukh et al., 2022; Ogunyemi et al., 2022). In addition, training can promote a decrease in IP (e.g., Metz et al., 2020), as well as positive feelings of liberation, empowerment, and connection with the peer group (e.g., Haney et al., 2018; Gold et al., 2019).

That said, when comparing coaching and training, the study by Zanchetta et al. (2020) is particularly interesting. According to these authors, coaching operates on multiple levels and produces a significant and lasting reduction in IP issues. However, training remains a more favorable approach for acquiring knowledge associated with IP. In the absence of studies comparing the different approaches, it is difficult to definitively establish the superiority of individual coaching over other modalities of intervention (i.e., training, support groups, etc.).

Future research could build on the promising approaches that counseling interventions seem to offer, by incorporating a psychoeducational component. Additionally, it appears that the group intervention modality seems appropriate for breaking the isolation related to IP. Although the current state of the literature provides interesting insights into the effectiveness of interventions, but it still needs to be enriched. It appears that mixed-method study designs, incorporating both quantitative measures and the analysis of qualitative data, would allow for an understanding of both if and how the interventions are useful and effective.

Limitations and futures research directions

This study has certain limitations that should be mentioned. A first limitation stems from the nature of the references included. Indeed, almost half do not present any research design. Consequently, the generalizability of their findings is extremely limited. Moreover, many studies that use a research design are exploratory and very few adopt a true experimental design. Most often, approaches to assessing the effects of intervention on IP are insufficiently robust. For example, some studies do not measure IP directly (e.g., Danhauer et al., 2019), others have no post-intervention measurement (e.g., Deshmukh et al., 2022), or assess intervention quality exclusively via self-reported satisfaction (e.g., Baumann et al., 2020). It is therefore difficult to generalize findings about the effects of these interventions on IP.

A second limitation arises from incomplete information regarding the characteristics and modalities of the interventions. Indeed, several studies offer a limited description of the design and implementation of the intervention for the IP. Aspects such as an overview of intervention content, duration, context, intervention mode and nature of interactions are not systematically reported by the authors (e.g., Clance and Imes, 1978; Baumann et al., 2020; DeCandia Vitoria, 2021). Details about the characteristics of these interventions are often lacking, even when they are essential.

A third limitation concerns the heterogeneity of the references collected and the interventions described, which constitutes an obstacle to comparing these interventions. For example, it would be inappropriate to compare the findings of an exploratory study (Harte and McGlade, 2018) with those of a randomized controlled trial (Mann et al., 2023). Similarly, it would not be reasonable to compare an intervention carried out over a period of 1 h (Deshmukh et al., 2022) with one carried out over a period of 1 day (Haney et al., 2018) or several months (Zanchetta et al., 2020). Thus, while most interventions on IP have recognizable positive effects, it remains difficult to establish precise criteria when it comes to evaluating the effectiveness of interventions on IP.

A fourth limitation regards the student population samples used in many studies included in this scoping review. Although we have restricted the eligible population to students in internship situations or already working in a professional environment, it is legitimate to wonder whether this “in-between” situation raises the same issues as those encountered in a strictly professional environment. In order to truly understand and address the organizational issues associated with IP, it would be important for future research to investigate a professional audience, at the very heart of the activity.

While this scoping review cannot pinpoint the ideal intervention for all the reasons mentioned above, it nonetheless identifies certain favorable trends for effectively intervening on IP. For example, bidirectional approaches, which promote exchange and openness, have particularly favorable impact on IP. Moreover, it is essential to consider different modes of IP expression and psychoeducation when developing an intervention. That said, it would also be relevant to promote reflective work on the causes of IP (psycho-social, educational, systemic origins, etc.), as well as the role of the social environment in reinforcing the beliefs and patterns associated with it. Finally, this scoping review highlights the fact that group support (as opposed to individual intervention) appears advantageous. However, customizing the intervention should be considered, to allow participants to develop a better sense of self. Developing individuals’ psychological resources by promoting self-knowledge also seems a particularly relevant research focus. According to Gullifor et al. (2023), the impostor phenomenon may emerge from an incongruence between one’s own self-concept and other self-concept. Therefore, any research perspective aimed at developing a more accurate vision of oneself is interesting. These avenues could be explored not only in future research, but also by those working with people reporting IP in an organizational context.

In summary, future research should respond to a dual contextual challenge: a gap to be bridged between the small number of scientific studies and the abundant lay literature on IP; and a lack of conceptual clarity regarding IP. From this perspective, future research should use more rigorous methodology in terms of variable measurement (e.g., systematic pre- and post-intervention measurements of the variables studied) and ensure that robust research designs are used (e.g., experimental or quasi-experimental designs). It may also be relevant to investigate the psychological processes involved in the development of IP in order to intervene on them. Regarding the framework and design of interventions, future studies could integrate a psychosocial understanding of the phenomenon into the aspects described above. This would distinguish them from the lay literature, build on advice and recommendations associated with purely individual strategies.

Conclusion

This scoping review is aimed at researchers and professionals interested in interventions for IP and presents the current state of knowledge in this regard. It discusses the different types of studies and methodologies emerging from this field of research, the modalities and characteristics of interventions, and their effects. It also provides insight into gaps and perspectives for future practices and research.

In conclusion, the study of interventions addressing IP is an emerging field of research that is recently experiencing considerable progress and still requires further exploration. Indeed, while the imposter syndrome is a topic that seems to have gained in popularity and is a common experience, there could be a risk involved in trivializing it. It represents a psychological health issue at work, ultimately affecting the proper functioning of organizations.

Although conceptual issues remain to be resolved to better understand IP, it is just as urgent to develop interventions aimed at reducing it, in view of its implications for people’s health and its negative consequences in the workplace. In light of the results reported in this scoping review, recognizing and educating individuals experiencing IP about its various manifestations, as well as offering support in a group context, appear to be important intervention strategies. Future interventions should aim to explore the psycho-social and educational influences, as well as the impact of the work environment on beliefs related to IP.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

EP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PD: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PM: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM-K: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marjorie Bilodeau from Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (Quebec, Canada), for her advice and assistance with the systematic search.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1360540/full#supplementary-material

References

Alrayyes, S., Dar, U. F., Alrayes, M., Alghutayghit, A., and Alrayyes, N. (2020). Burnout and imposter syndrome among Saudi young adults. the strings in the puppet show of psychological morbidity. Saudi Med. J. 41, 189–194. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.2.24841

Ares, T. L. (2018). Role transition after clinical nurse specialist education. Clin. Nurse Specialist 32, 71–80. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000357

Arleo, E. K., Wagner-Schulman, M., McGinty, G., Salazar, G., and Mayr, N. A. (2021). Tackling impostor syndrome: a multidisciplinary approach. Clin. Imaging 74, 170–172. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.12.035

Armstrong, M. J., and Shulman, L. M. (2019). Tackling the imposter phenomenon to advance women in neurology. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 9, 155–159. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000607

Baumann, N., Faulk, C., Vanderlan, J., Chen, J., and Bhayani, R. K. (2020). Small-group discussion sessions on imposter syndrome. MedEdPORTAL 16:11004. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11004

Bechtoldt, M. (2015). Wanted: self-doubting employees—managers scoring positively on impostorism favor insecure employees in task delegation. Pers. Individ. Dif. 86, 482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.002

Bernard, N. S., Dollinger, S. J., and Ramaniah, N. V. (2002). Applying the big five personality factors to the impostor phenomenon. J. Pers. Assess. 78, 221–233. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7802_07

Blondeau, L. A., and Awad, G. H. (2018). The relation of the impostor phenomenon to future intentions of mathematics-related school and work. J Career Dev. 45, 253–267. doi: 10.1177/0894845316680769

Brauer, K., and Wolf, A. (2016). Validation of the german-language clance impostor phenomenon scale (GCIPS). Pers. Individ. Dif. 102, 153–158.

Bravata, D. M., Watts, S. A., Keefer, A. L., Madhusudhan, D. K., Taylor, K. T., Clark, D. M., et al. (2020). Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 1252–1275.

Byrnes, K. D., and Lester, D. (1995). The imposter phenomenon in teachers and accountants. Psychol. Rep. 77:350. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.1.350

Chang, S., Lee, H. Y., Anderson, C., Lewis, K., Chakraverty, D., and Yates, M. (2022). Intervening on impostor phenomenon: prospective evaluation of a workshop for health science students using a mixed-method design. BMC Med. Educ. 22:802.

Chassangre, K. (2016). La Modestie Pathologique : Pour Une Meilleure Compréhension du Syndrome de L’imposteur. Thèse doctorale. Toulouse: Université Toulouse le Mirail.

Chassangre, K., and Callahan, S. (2015a). “Outils de prise en charge cognitive et comportementale du syndrome,” in Traiter la dépréciation de soi. Le syndrome de l’imposteur, ed. Dunod (Paris: Dunod), 135–169

Chassangre, K., and Callahan, S. (2015b). “Exercices et méthodes pour consolider la prise en charge,” in Traiter la dépréciation de soi. Le syndrome de l’imposteur, ed. Dunod (Paris: Dunod), 170–180.

Chassangre, K., and Callahan, S. (2017). J’ai réussi, j’ai de la chanc je serai démasqué: revue de littérature du syndrome de l’imposteur. Pratiques Psychologiques 23, 97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.prps.2017.01.001

Chrisman, S. M., Pieper, W. A., Clance, P. R., Holland, C. L., and Glickauf-Hughes, C. (1995). Validation of the clance imposter phenomenon scale. J. Pers. Assess. 65, 456–467. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_6

Clance, P. R. (1985). “Part three: Taking off the mask,” in The impostor phenomenon: Overcoming the fear that haunts your success, ed. Peachtree Pub Ltd (Atlanta: Peachtree Pub Ltd), 129–191.

Clance, P. R., Dingman, D., Reviere, S. L., and Stober, D. R. (1995). Impostor phenomenon in an interpersonal/social context. Women Therapy 16, 79–96. doi: 10.1300/J015v16n04_07

Clance, P. R., and Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 15, 241–247. doi: 10.1037/h0086006

Clance, P. R., and O’Toole, M. A. (1987). The imposter phenomenon: an internal barrier to empowerment and achievement. Women Therapy 6, 51–64. doi: 10.1300/J015V06N03_05

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., et al. (2014). Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Crawford, W. S., Shanine, K. K., Whitman, M. V., and Kacmar, K. M. (2016). Examining the impostor phenomenon and work-family conflict. J. Manag. Psychol. 31, 375–390. doi: 10.1108/JMP-12-2013-0409

Danhauer, S. C., Tooze, J. A., Barrett, N. A., Blalock, J. S., Shively, C. A., Voytko, M. L., et al. (2019). Development of an innovative career development program for early-career women faculty. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 8:2164956119862986. doi: 10.1177/2164956119862986

DeCandia Vitoria, A. (2021). Experiential supervision: healing imposter phenomenon from the inside out. Clin. Supervisor 40, 200–217.

Deshmukh, S., Shmelev, K., Vassilades, L., Kurumety, S., Agarwal, G., and Horowitz, J. M. (2022). Imposter phenomenon in radiology: incidence, intervention, and impact on wellness. Clin. Imaging 82, 94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.11.009

Dowd, S. B., and Davidhizar, R. (1997). Do you feel like an impostor? Health Care Supervisor 15, 51–56.

Fainstad, T., Mann, A., Suresh, K., Shah, P., Dieujuste, N., Thurmon, K., et al. (2022). Effect of a novel online group-coaching program to reduce burnout in female resident physicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 5, 1–14.

Fried-Buchalter, S. (1997). Fear of success, fear of failure, and the imposter phenomenon among male and female marketing managers. Sex Roles 37, 847–859. doi: 10.1007/BF02936343

Fruhan, G. A. (2002). Understanding Feelings of Fraudulence in the Early Professional Lives of Women. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest Information & Learning.

Fujie, R. (2010). Development of the state impostor phenomenon scale. Jap. Psychol. Res. 52, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5884.2009.00417.x

Gold, J. A., Bentzley, J. P., Franciscus, A. M., Forte, C., and De Golia, S. G. (2019). An intervention in social connection: medical student reflection groups. Acad. Psychiatry 43, 375–380. doi: 10.1007/s40596-019-01058-2

Gullifor, D. P., Gardner, W. L., Karam, E. P., Noghani, F., and Cogliser, C. C. (2023). The impostor phenomenon at work: a systematic evidence-based review, conceptual development, and agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 45, 234–251. doi: 10.1002/job.2733

Haney, T. S., Birkholz, L., and Rutledge, C. (2018). A workshop for addressing the impact of the imposter syndrome on clinical nurse specialists. Clin. Nurse Specialist 32, 189–194. doi: 10.1097/nur.0000000000000386

Harte, S., and McGlade, K. (2018). Developing excellent leaders - the role of executive coaching for GP specialty trainees. Educ. Primary Care 29, 286–292. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2018.1501770

Harvey, J. C. (1981). The impostor phenomenon and achievement: A failure to internalize success. Temple University.

Harvey, J. C., and Katz, C. (1985). “Chapter seven: Throwing away the mask,” in If I’m so successful why do i feel like a fake: The impostor phenomenon., ed. St Martin’s Press (New York, NY: St Martin’s Press), 205–240.

Jaqua, E. E., Nguyen, V., Park, S., and Hanna, M. (2021). Coping with impostor syndrome. Fam. Pract. Manag. 28:40.

Kananifar, N., Seghatoleslam, T., Atashpour, S., Hoseini, M., Habil, M., and Danaee, M. (2015). The relationships between imposter phenomenon and mental health in isfahan universities students. Int. Med. J. 22, 144–146.

Kark, R., Meister, A., and Peters, K. (2022). Now you see me, now you don’t: a conceptual model of the antecedents and consequences of leader impostorism. J. Manag. 48, 1948–1979. doi: 10.1177/01492063211020358

LaDonna, K. A., Ginsburg, S., and Watling, C. (2018). “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: what physicians’ self-assessment of their performance reveals about the imposter syndrome in medicine. Acad. Med. 93, 763–768.

Leach, P. K., Nygaard, R. M., Chipman, J. G., Brunsvold, M. E., and Marek, A. P. (2019). Impostor phenomenon and burnout in general surgeons and general surgery residents. J. Surgical Educ. 76, 99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.06.025

Leary, M. R., Patton, K. M., Orlando, A. E., and Wagoner Funk, W. (2000). The impostor phenomenon: Self?perceptions, reflected appraisals, and interpersonal strategies. J. Pers. 68, 725–756.

Legassie, J., Zibrowski, E. M., and Goldszmidt, M. A. (2008). Measuring resident well-being: impostorism and burnout syndrome in residency. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 1090–1094. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0536-x

Leonhardt, M., Bechtoldt, M. N., and Rohrmann, S. (2017). All impostors aren’t alike–differentiating the impostor phenomenon. Front. Psychol. 8:1505. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01505

Liu, S., Wei, M., and Russell, D. (2023). Effects of a brief self-compassion intervention for college students with impostor phenomenon. J. Couns. Psychol. 70, 711–724. doi: 10.1037/cou0000703

Lockwood, C., and Tricco, A. C. (2020). Preparing scoping reviews for publication using methodological guides and reporting standards. Nurs. Health Sci. 22, 1–4. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12673

Magro, C. (2022). From hiding to sharing. a descriptive phenomenological study on the experience of being coached for impostor syndrome. Int. J. Evidence Based Coaching Mentoring S16, 68–80. doi: 10.24384/0409-b325

Mak, K. K. L., Kleitman, S., and Abbott, M. J. (2019). Impostor phenomenon measurement scales: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 10:671. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00671

Mann, A., Shah, A. N., Thibodeau, P. S., Dyrbye, L., Syed, A., Woodward, M. A., et al. (2023). Online well-being group coaching program for women physician trainees: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 6:e2335541. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.35541

Matthews, G., and Clance, P. R. (1985). Treatment of the impostor phenomenon in psychotherapy clients. Psychother. Private Pract. 3, 71–81. doi: 10.1300/J294v03n01_09

McElwee, R. O. B., and Yurak, T. J. (2007). Feeling versus acting like an impostor: Real feelings of fraudulence or self-presentation? Individ. Differ. Res. 5.

McElwee, R. O. B., and Yurak, T. J. (2010). The phenomenology of the impostor phenomenon. Individ. Dif. Res. 8, 184–197.

Metz, C. J., Ballard, E., and Metz, M. J. (2020). The stress of success: an online module to help first-year dental students cope with the impostor Phenomenon. J. Dental Educ. 84, 1016–1024. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12181

Mir, I., and Kamal, A. (2018). Role of workaholism and self-concept in predicting impostor feelings among employees. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 33, 413–427.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., and Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18, 1–7.

Neureiter, M., and Traut-Mattausch, E. (2016). An inner barrier to career development: preconditions of the impostor phenomenon and consequences for career development. Front. Psychol. 7:48. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00048

Neureiter, M., and Traut-Mattausch, E. (2017). Two sides of the career resources coin: career adaptability resources and the impostor phenomenon. J. Vocat. Behav. 98, 56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2016.10.002

Ogunyemi, D., Lee, T., Ma, M., Osuma, A., Eghbali, M., and Bouri, N. (2022). Improving wellness: defeating Impostor syndrome in medical education using an interactive reflective workshop. PLoS One 17:e0272496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272496

Oriel, K., Plane, M. B., and Mundt, M. (2004). Family medicine residents and the impostor phenomenon. Fam. Med. 36, 248–252.

Parkman, A., and Beard, R. (2008). Succession planning and the imposter phenomenon in higher education. CUPA-HR J. 59, 29–36.

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., and Khalil, H. (2020). Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., and Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 13, 141–146.

Popovic, M. (2020). The Impact of Bowen Family Systems Theory Group Supervision Intervention with Master Level Marriage and Family Therapy Students Who Self-Identify with Having Imposter Phenomenon. Doctoral dissertation. Texas: Texas Wesleyan University.

Ramsey, J. L., and Spencer, A. L. (2019). Interns and imposter syndrome: proactively addressing resilience. Med. Educ. 53, 504–505. doi: 10.1111/medu.13852

Rohrmann, S., Bechtoldt, M. N., and Leonhardt, M. (2016). Validation of the impostor phenomenon among managers. Front. Psychol. 7:821. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00821

September, A. N., McCarrey, M., Baranowsky, A., Parent, C., and Schindler, D. (2001). The relation between well-being, impostor feelings, and gender role orientation among canadian university students. J. Soc. Psychol. 141, 218–232. doi: 10.1080/00224540109600548

Sonnak, C., and Towell, T. (2001). The impostor phenomenon in British university students: relationships between self-esteem, mental health, parental rearing style and socioeconomic status. Pers. Individ. Dif. 31, 863–874. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00184-7

Steinberg, J. A. (1987). Clinical interventions with women experiencing the impostor phenomenon. Women Therapy 5, 19–26. doi: 10.1300/J015V05N04_04

Tewfik, B. A. (2022). The impostor phenomenon revisited: examining the relationship between workplace impostor thoughts and interpersonal effectiveness at work. Acad. Manag. J. 65, 988–1018. doi: 10.5465/amj.2020.1627

Topping, M. H. (1983). The Impostor Phenomenon: a Study of its Construct and Incidence in University Faculty Members. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest Information & Learning.

Tricco, A. C., Khalil, H., Holly, C., Feyissa, G., Godfrey, C., Evans, C., et al. (2022). Rapid reviews and the methodological rigor of evidence synthesis: a JBI position statement. JBI Evid. Synth. 20, 944–949. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-21-00371

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Internal Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Vergauwe, J., Wille, B., Feys, M., De Fruyt, F., and Anseel, F. (2015). Fear of being exposed: the trait-relatedness of the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in the work context. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 565–581. doi: 10.1007/s10869-014-9382-5

Keywords: scoping review, impostor phenomenon, interventions, workplace, adults

Citation: Para E, Dubreuil P, Miquelon P and Martin-Krumm C (2024) Interventions addressing the impostor phenomenon: a scoping review. Front. Psychol. 15:1360540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1360540

Received: 23 December 2023; Accepted: 05 March 2024;

Published: 28 March 2024.

Edited by:

Susanne Braun, Durham University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Timothy Holmes, Durham University, United KingdomDaniel Gullifor, University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, United States

Copyright © 2024 Para, Dubreuil, Miquelon and Martin-Krumm. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emma Para, ZW1tYS5wYXJhQHVxdHIuY2E=

Emma Para

Emma Para Philippe Dubreuil

Philippe Dubreuil Paule Miquelon

Paule Miquelon Charles Martin-Krumm

Charles Martin-Krumm