- 1Department of Psychiatry, Montreal University, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de l’Université de Montreal, Instititut Universitaire en Santé mentale de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine and Health Science, United Arab Emirates University, Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates

- 3Department of Psychiatry, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

- 4Department of Mental Health, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada

- 5Centre for Affective Disorders, Psychological Medicine, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom

- 6Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 7Montreal University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 8New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 9University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

- 10Université de Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland

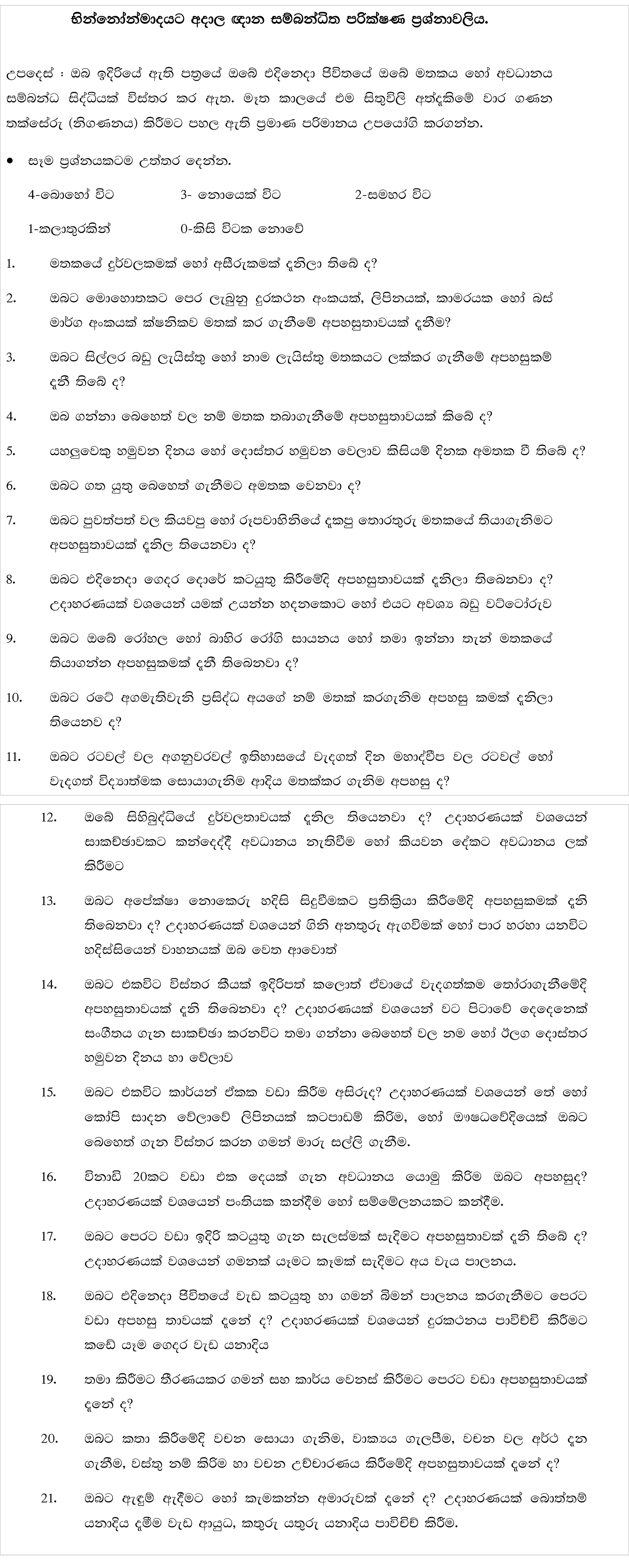

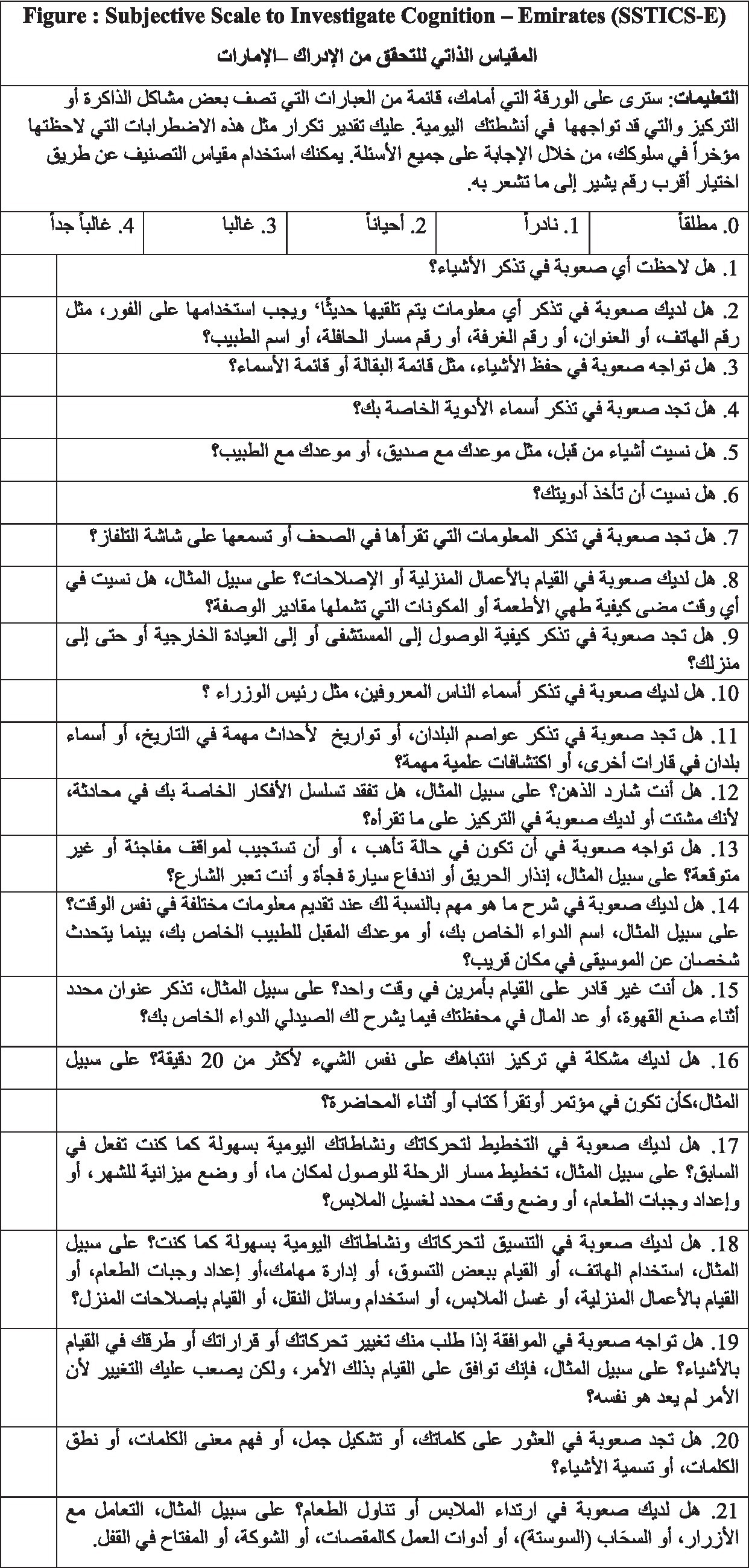

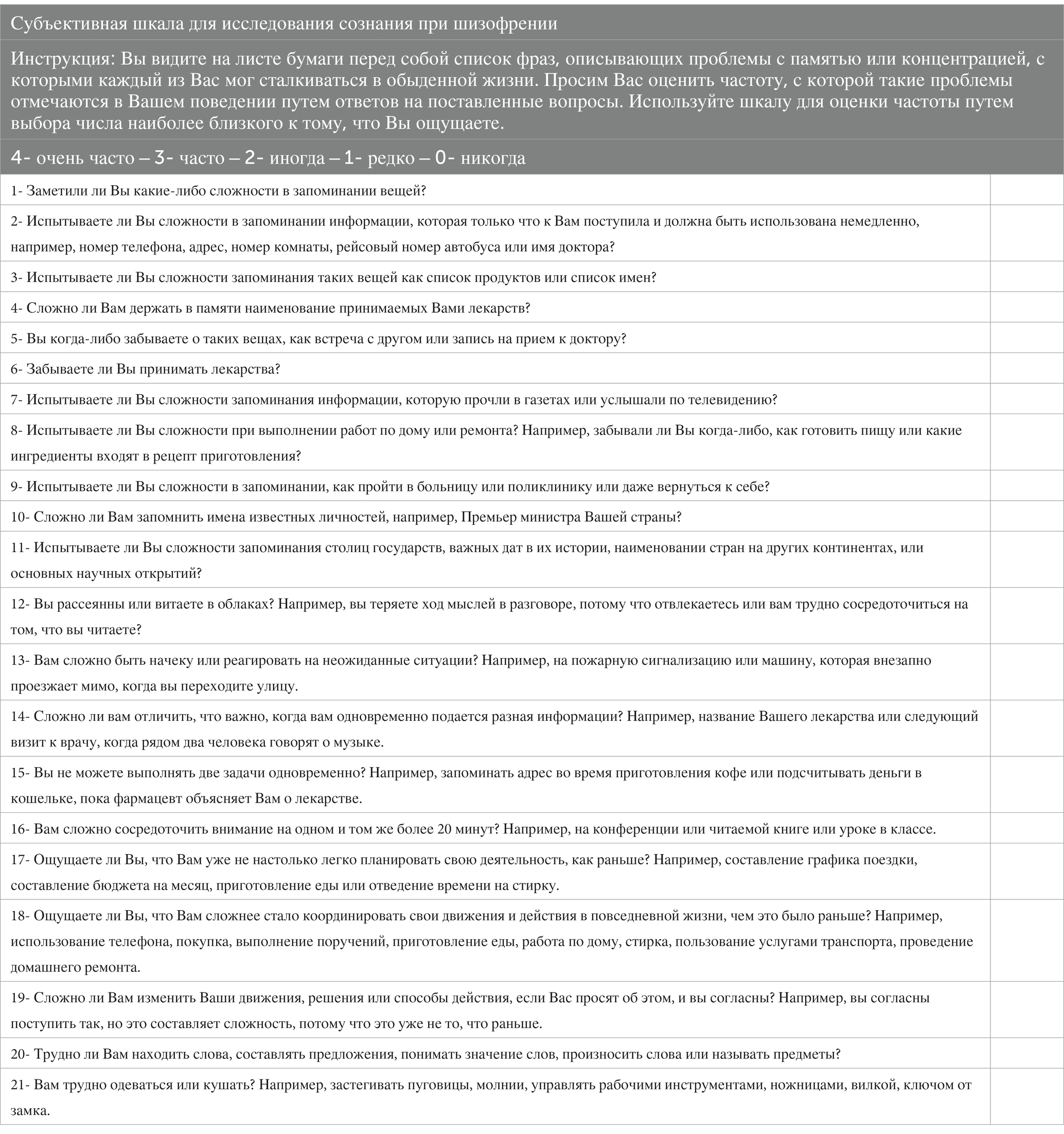

The development of appropriate and valid multicultural and multilingual instruments research is necessary due to a growing multicultural and multilingual society in the 21st century. We explored the use of a cognitive scale related to subjective complaints, focusing on the first step: a cross-cultural and semantic validation. This study presents the translation and cross-validation process of the “Subjective Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia” (SSTICS) for the United Arab Emirates (UAE) region via different languages used in Dubaï/Abu Dhabi. This scale measures cognitive complaints and has been validated with psychosis and used in 20 clinical trials worldwide. It evaluates areas of the illness related to self-awareness focusing on memory dysfunction and deficits of attention, language, and praxis. We described the method of cross-cultural validation, with back-translation, semantic steps, and societal contexts. The use of the Subjective Scale to Investigate Cognition in Emirates (SSTIC-E) was explored with different samples of UAE Arabic-speaking subjects. First, a pilot sample mean SSTICS total score was 16.5 (SD:16.9); (p < 0.001). The SSTIC-E was then administered to 126 patients and 84 healthy control participants. The healthy group has a lower mean score of 22.55 (SD = 12.04) vs. 34.06 (SD = 15.19). The method was extended to nine other languages, namely, Pakistani/Urdu, Hindi, Marathi, Lithuanian, Serbian, German, Romanian, Sinhala, and Russian. The scales are provided in the article. The overall aim of the translation process should be to stay close to the original version of the instrument so that it is meaningful and easily understood by the target language population. However, for construct validity, some items must be adapted at the time of translation to ensure that the questioned cognitive domain is respected. For example, cooking, an executive function, does not have the same occurrence for an Emirati male, or remembering a prime minister’s name, semantic memory, requires an electoral system to appoint the leader of a country. Translation methods and processes present many challenges but applying relevant and creative strategies to reduce errors is essential to achieve semantic validation. This study aims to measure personally experienced knowledge or attitudes; such language effects can be a thorny problem.

Introduction

The availability of psychological assessment tools in many languages is essential in generalizing research results across different cultural settings or in conducting cross-cultural comparative studies. Yet, translating these tools, especially those relying on the reporting of subjective states, poses several challenges. According to Nida (1993) and Huang et al. (2022), cultural differences constitute significant obstacles for translators and are the source of misconceptions among readers. If translation is seen as a form of intercultural communication and cultural differences cause significant difficulties in translation, then its impact is even more prominent when it comes to translating subjective cognitive content. According to these authors, in addition to lexical, semantic, and grammatical structures, translation becomes a task that serves to faithfully transcribe the meaning of information written in one language (for instance English) with the same information in another language (Arabic).

Most psychometrically sound research instruments have been developed and their properties evaluated using English-speaking populations (Capitulo et al., 2001; Duffy, 2006). Given the cultural diversity and the variety of languages spoken in the world, health researchers are challenged to be culturally and linguistically sensitive when administering a clinical instrument (Abdel Aziz et al., 2021).

The process of cross-cultural validation allows the translation of a clinical instrument into a language different from the one in which it was developed and it may contribute to identifying any possible cultural-related variability in the phenomena studied when a different language is used. It is always considered a complex process because of the possible interference arising from cross-cultural and ethnic factors that were not accounted for at the time the instrument was originally designed (Duffy, 2006).

Success in tackling these challenges, according to Hilton and Skrutkowski (2002), depends on understanding the fundamental problems of language equivalence, cultural constructs, and psychometric changes that are embedded in translation (Stip, 1996). This should be the first consideration when seeking to develop a culturally equivalent translated instrument. We illustrate this process in psychopathology with the case of a scale measuring cognitive complaints in schizophrenia (Stip, 1996; Hilton and Skrutkowski, 2002).

Subjective Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is associated with significant cognitive impairments, as illustrated by both narrative (Stip, 1996) and systematic reviews, such as a recent umbrella review (Gebreegziabhere et al., 2022) that summarized the findings of 63 systematic reviews published in this field (Table 1).

Specifically, these systematic reviews have reported that people with schizophrenia have lower cognitive functioning when compared to both healthy individuals and those with affective disorders, with some cognitive domains being affected more than others. The specific deficits relate to long-term outcomes in the areas of memory, attention, executive tasks, language, and social cognition, and most chronic patients with schizophrenia are ranked in the fifth percentile below normal in some measures of neuropsychological function (Tyson et al., 2008).

Generally, the memory includes a set of autonomous systems: sensory memory, short-term memory (working memory), and long-term memory. The latter is divided into explicit (conscious), also known as declarative memory (facts and events), and implicit (unconscious) memory, also known as procedural memory (skills and tasks). Finally, declarative memory is divided into semantic and episodic memory (Craik and Lockhart, 1972).

Among the cognitive impairments reported in schizophrenia, those related to self-perceived insight continue to be a developing research area and one of the utmost clinical importance given the findings that more than half of all patients suffering from schizophrenia do not believe that they have a disorder (Dam, 2006). Moreover, in addition to general cognitive ability and cognitive dysfunctions, poor clinical insight in schizophrenia has been found to also be associated with theory of mind deficits (Bora, 2017), thus highlighting the difficulty of a patient with positive or negative symptoms to subjectively recognize their own cognitive impairment (Lecardeur et al., 2009). Research in the area of insight and cognitive functioning in schizophrenia depends on the availability of assessment tools that, in addition to objective neuropsychological testing, make use of patients’ self-reporting. One such tool is the Subjective Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia (SSTICS) developed by Stip et al. (2003). The scale is a questionnaire based on 21 very pragmatic questions that assess specific aspects of cognition and target cognitive domains known to be impaired in people with schizophrenia. This scale was originally constructed and validated in parallel in the two official Canadian languages, French and English. Since its inception, there have been more than 20 publications in PubMed that employed this scale, and it has been used in clinical studies translated into five languages, namely Italian (Stratta et al., 2020), Castilian (Bengochea Seco et al., 2010), Mandarin/Taiwan (Chuang et al., 2019), Korean (Shin et al., 2016), Hindi (Baliga et al., 2020), and Tunisian Arabic or SASCCS (Johnson et al., 2009; Bouhamed et al., 2021; Haddad et al., 2021).

SSTICS is an instrument designed to collect self-reported cognitive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia (Prouteau et al., 2004; Homayoun et al., 2011; Cella et al., 2020). The scale has been constructed and described in a seminal article in 2003 (see Stip et al., 2003 for the complete description of each item of the scale) (Stip et al., 2003). It is straightforward to use and designed as a Likert-type. It provides a measure of all the aspects of subjective cognition and insight into schizophrenia (Bayard et al., 2009; Sellwood et al., 2013; Potvin et al., 2014; Stip et al., 2022).

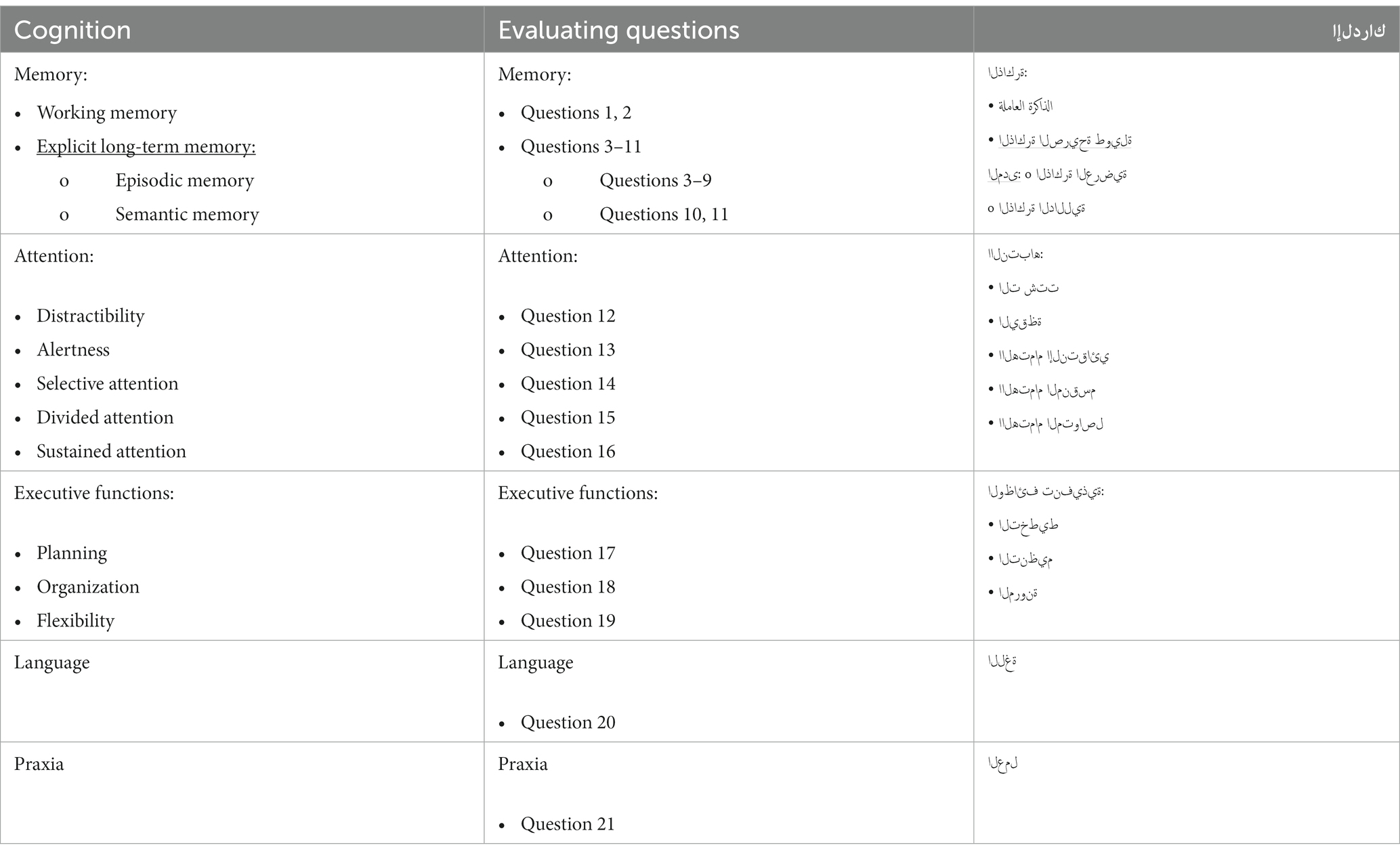

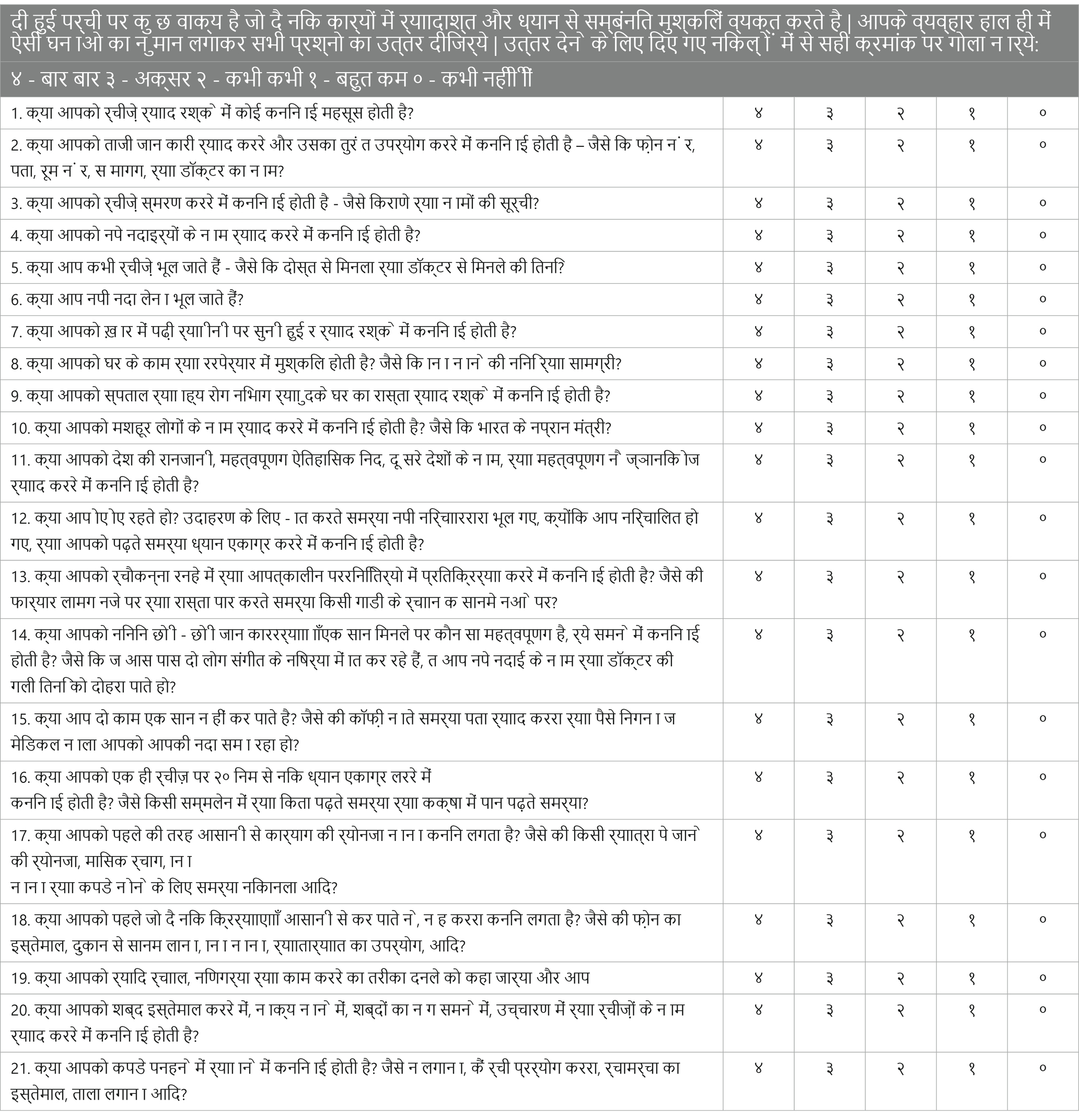

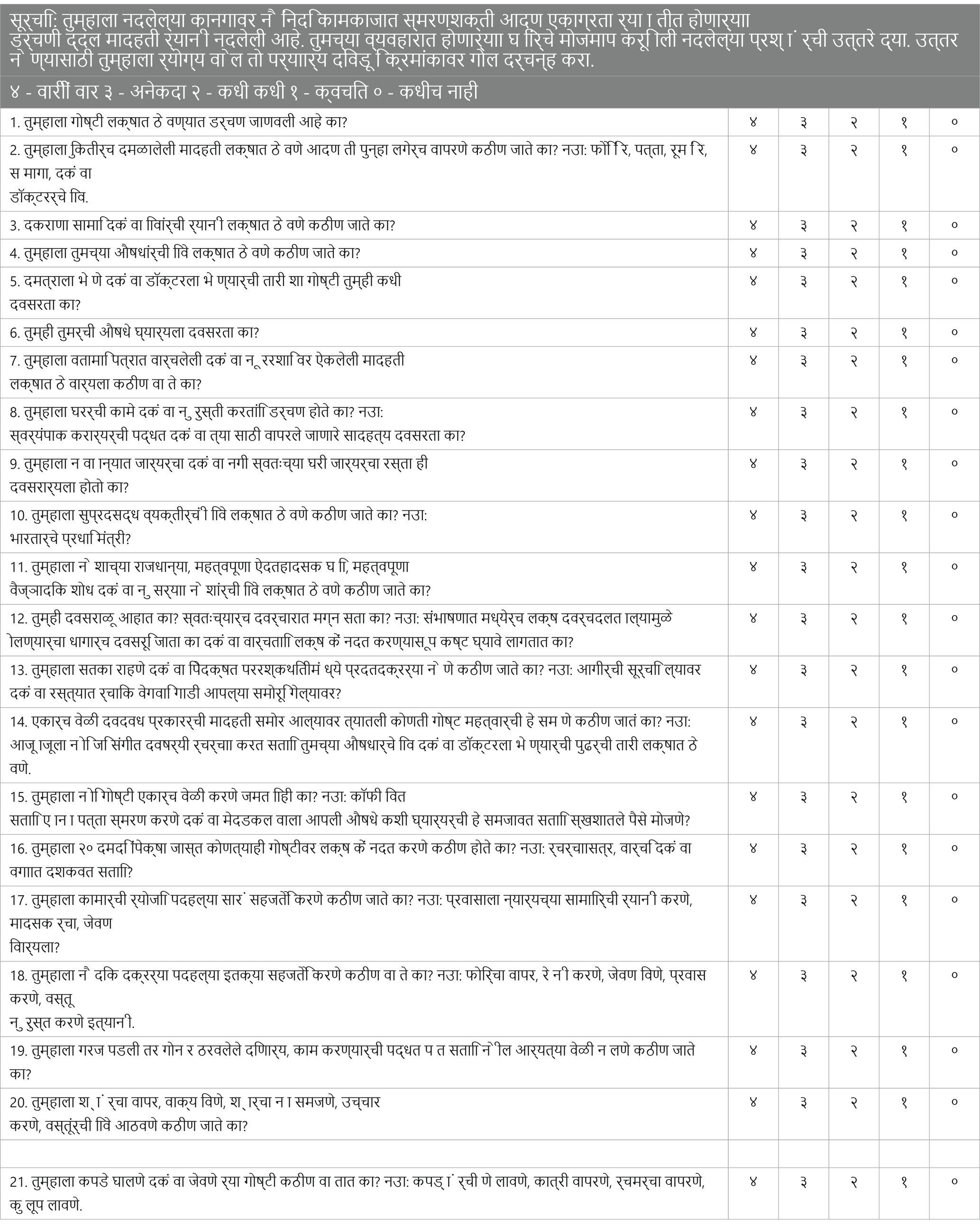

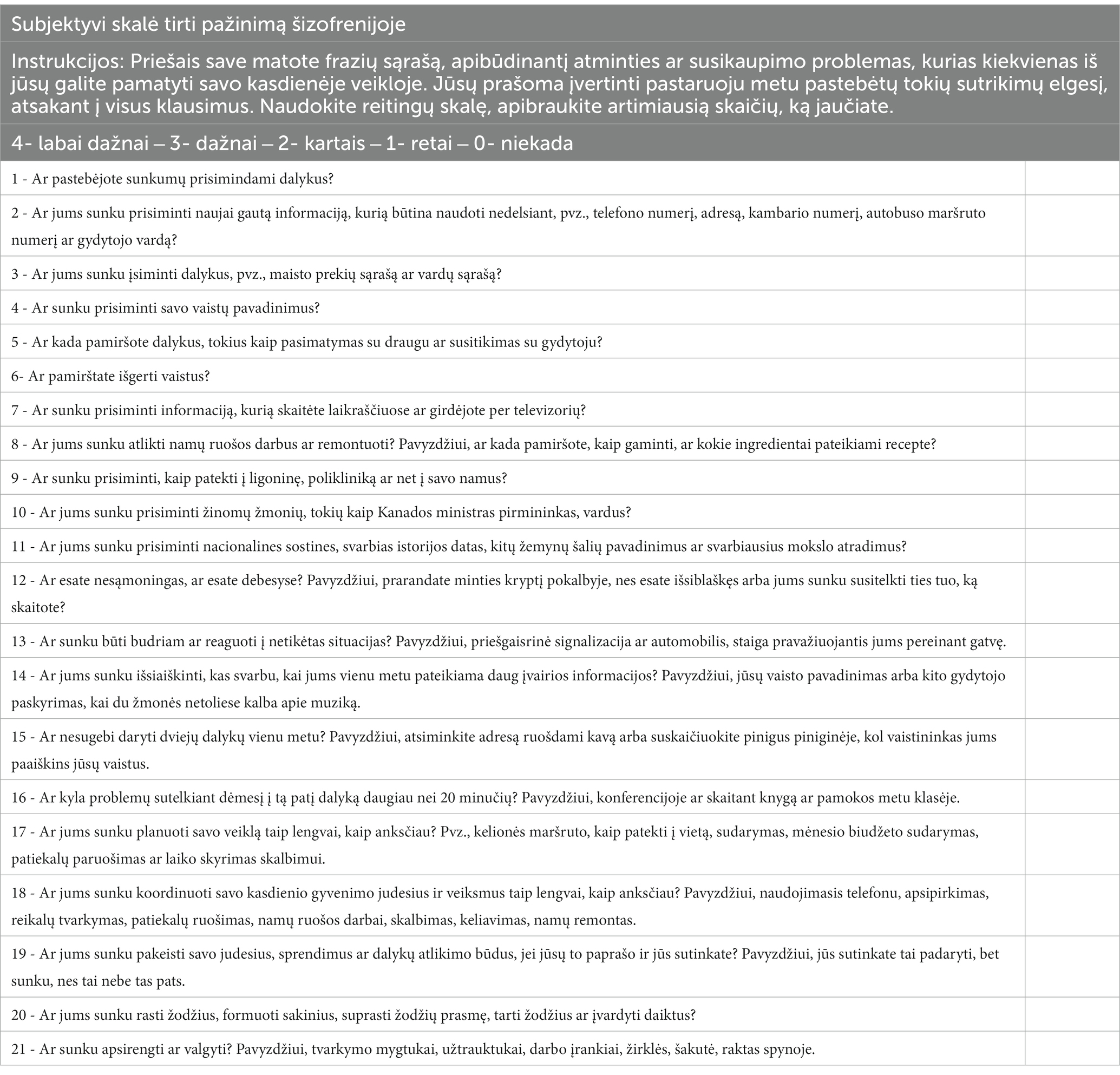

Initially based on the discoveries of objective cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, the SSTICS scale is a construct that, using simple questions asked to the person, aims to reflect a cognitive complaint in a mirror of the objective cognitive domain. Therefore, specific areas of cognition covered are working memory, explicit memory (divided into episodic and semantic memory), attention, executive function, and language. The scale consists of five domains to assess subjective complaints, in which the first domain assesses memory in two forms (working memory in questions 1 and 2) and explicit long-term memory (episodic memory questions 3–9, and semantic memory in questions 10 and 11). The second domain assesses attention in five sub-domains from question 12 to question 16 (distractibility Q12, alertness Q13, selective attention Q14, divided attention Q15, and sustained attention Q16). The third domain evaluates executive functions in questions 17, 18, and 19, by asking about planning in Q17, organization in Q18, and flexibility in Q19. The fourth domain for language assessment in question 20 and question 21, which is the last on the scale is for praxia assessment (Table 2).

UAE and cross-cultural validation context

Mental health services started in the mid-1970s in the UAE and developed from the psychiatric services offered in some of the emirates (i.e., Abu Dhabi and Dubai). In the early 1980s, psychotherapy that was offered to psychiatric patients as treatment in hospitals was seen as a supportive service (Al-Darmaki, 2003, 2004). Over the last 30 years, the need for psychotherapy in the UAE community gained importance with the rapid social and economic changes associated with the influence and impact of other cultures (Table 3).

Only recently, several objective assessment tools have been translated and adapted for application in the UAE Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment test (MOCA). However, there are no assessment tools to assess subjective cognitive complaints or deficits in performance in patients with schizophrenia in the UAE.

The presence of interpreters or translators may complicate the psychotherapeutic process of a patient (El-Islam, 2005; Miller et al., 2005; Anderson et al., 2009; Hunt and Swartz, 2017). A clear understanding of the dialectal and cultural characteristics among Arab patients is needed (Okasha et al., 2000; Sayed, 2003). The development of mental health concepts depends on the accuracy of the conversation between the therapist and the patient, as well as the impact of culture on how the patients can express their emotions. Personal emotional expression, either publicly or in interactions with others, is not encouraged in UAE culture in general (Table 4).

Patients are encouraged by their therapists and physicians to express their emotions and describe how their overall health status is affected. The same concerns can be applied to cognition. Therefore, considering the differences between cultures, languages, and beliefs is crucial when developing or modifying a psychometric scale, ensuring the relevance and effectiveness of the resulting instrument.

Relevance

For any novel psychometric instrument to be applied in a different culture (UAE) from the setting in which it was originally developed (Canada), it needs to be appropriately adapted. Cultural adaptation of an existing instrument has many benefits over creating an entirely new tool, such as reducing cost and time spent developing it. Psychometric instruments, such as SSTICS, can not only stimulate cross-cultural research but also be employed in many fields such as public health, primary health care, psychiatry, neurology, and other disciplines. In practice, cultural adaptation is done while translating the tool from its original language and it precedes its psychometric validation through the assessment of different aspects of reliability and validity using well-established scientific measures. In this process, the self-reporting scales are potentially susceptible to significant alterations resulting from a series of influences, including social attractiveness, suppression, habits, and response style. Thus, describing and analyzing the cultural adaptation and psychometric validation process may serve as a guide for future similar undertakings (Table 5).

SSTICS in Arabic

Cross-cultural validation of an assessment instrument is a complex process that requires a significant investment in time and financial resources (Bullinger et al., 1993). Even though a 2015 review of cross-cultural adaptation guidelines for questionnaires did not find a consensus among the 31 guidelines investigated in this study, the authors reported that similar results were achieved using most of them as long as the adaptation and validation processes were properly and separately considered (Epstein et al., 2015). Before venturing into this process for SSTICS, it is vital to ensure that there is no equivalent instrument in the Arabic language, or an equivalent instrument translated and validated. Otherwise, the researcher must make an exhaustive review of the instruments relevant to his study to select the one that has passed the validation stages, is the most rigorous, and is in its original language (Haccoun, 1987; Flaherty et al., 1988; Guillemin et al., 1993).

In general, the cross-cultural validation of an instrument involves three main steps: (1) the translation and verification of its equivalence; (2) empirical verification of the validity of the translated version; (3) adaptation of scores to cultural context and development standards (Epstein et al., 2015). Each of them also includes steps necessary for creating a valid version, and several options are available to the researcher with their advantages and disadvantages. The semantic aspect of a questionnaire is the first step to consider before going any further with the validation. It is often a neglected step. The difference between dialects needs to be considered (Table 6).

There are different types of translation methods. The translation process must ensure that an instrument retains inferential equivalence, that is, it is possible to produce the same inferences from the translated version as with the original instrument. The correspondence between words (semantic equivalence) is difficult to achieve from one culture to another, considering the vocabulary, dialect, and grammar specific to each language.

This can be the case between the UAE and Canada. Some translated expressions have no meaning in another culture, and expressions specific to the target culture, and retaining the meaning of the items must be found (equivalence of expression). Certain situations that are evoked in the culture of the original instrument may not correspond to the reality in another culture. These items should be replaced by other situations appropriate to the target culture while preserving the objective and the meaning aimed by these items (experiential equivalence) (Guillemin et al., 1993).

Finally, the same exercise should be applied to some concepts, which, when translated, do not allow the exact representation of the target culture (conceptual equivalence). Translating items into different contexts is a delicate task that raises many questions. Only translating an instrument into the local language does not guarantee validity and accuracy in a different context.

Capitulo et al. (2001) identified the decentering of the translation process as an extension of back-translation (Capitulo et al., 2001). Once the final version has been developed, after the back-translation, whoever owns the copyright to the original instrument and the translation team/individual will agree on the semantic equivalence between the “original’ and the translation instrument by modifying the original instrument for universally better-understood language (Capitulo et al., 2001).

Hilton and Skrutkowski (2002) describe symmetric and asymmetric categories of translation. Symmetric translation requires that the original and the translation instruments be faithful to meaning and familiarity. Decentering refers to the translation process in which the source and target of language versions are seen as equally important and subject to change (Hilton and Skrutkowski, 2002).

In the asymmetric translation category, the original language is kept without modification, thus the translated version may present a literal translation of words and may lack conceptual equivalence. One of the reasons that an instrument developer or organization resists making changes is to avoid compromising the validity and instrument reliability. The translation process is considered incomplete until the instrument is pretested with members of the target culture.

Pretesting an instrument primarily serves two purposes: it checks the quality of the translation and the practicalities of test administration (Hilton and Skrutkowski, 2002).

Several objectives are targeted when translating the tool, not only the meaning but also the equivalence of content, technique, and concept. The ‘subject’s belonging to a different ethnic group influences their results in the various clinical tests’. A great deal of documentation exists revealing the difficulties caused by using assessment instruments in a different cultural context other than the one they were created for. Flaherty et al. (1988) show that to ensure the correct use of a diagnostic instrument in a new cultural context (Flaherty et al., 1988), it is essential to verify the equivalence of these five dimensions:

Content equivalence corresponds to the content of each instrument item that is relevant in the cultures where its use is conceived. This step includes the verification of the items by a team of specialists from each culture. They decide on the relevance or not of each item. At best, the author of the tool is contacted.

Semantic equivalence corresponds to the fact that the meaning of each item remains the same after translating the tool into the target language. Back-translation is considered the best method to ensure semantic equivalence, translating the scale into the desired language and then reverse translation by another translator into the original language.

A high-importance concept, technical equivalence should be directly related to the assessment method and not interfere with results obtained from one culture to another, for example, when the paper-and-pencil method is not necessarily familiar or a male interviewer interviewing women in certain contexts, which can skew the data.

• Criteria equivalence is the tool’s ability to assess a variable in two different cultures. After analyzing the data, the interpretation of the results should be similar.

• Finally, conceptual equivalence corresponds to the fact that the tool measures the same theoretical construct in each culture, in our case, subjective cognition (Flaherty et al., 1988).

Translation is the first step; the adaptation process is the second step. The term “adaptation” has a different meaning from “translation”; hence, adaptation contains all modifications of the translated document related to cultural, dialectal, linguistic, and contextual aspects (Beaton, 2010; Gjersing, 2010; Paula, 2014). Adaptation ensures that the resulting tool achieves the required uniformity and offers contextual, dialectal, experiential, and hypothetical equivalence, as backed by the expert committee review and the creators of the scale (Bravo et al., 1991).

Objectives

In this study, our general objective was to present the different steps necessary at the very beginning of the process of cultural adaptation and validation of the SSTICS. In the UAE, the questionnaire’s clientele is from several countries and with various ethnicities making the study complex. We started the back-translations with the Emirates Arabic language, which is the predominant language in the United Arab Emirates, and then we added a comparison of back-translations from 9 other languages for the scale to compare the differences between all back-translations. All the versions will be added to the first Arabic back-translation since UAE has residents from different countries and nationalities (Table 7).

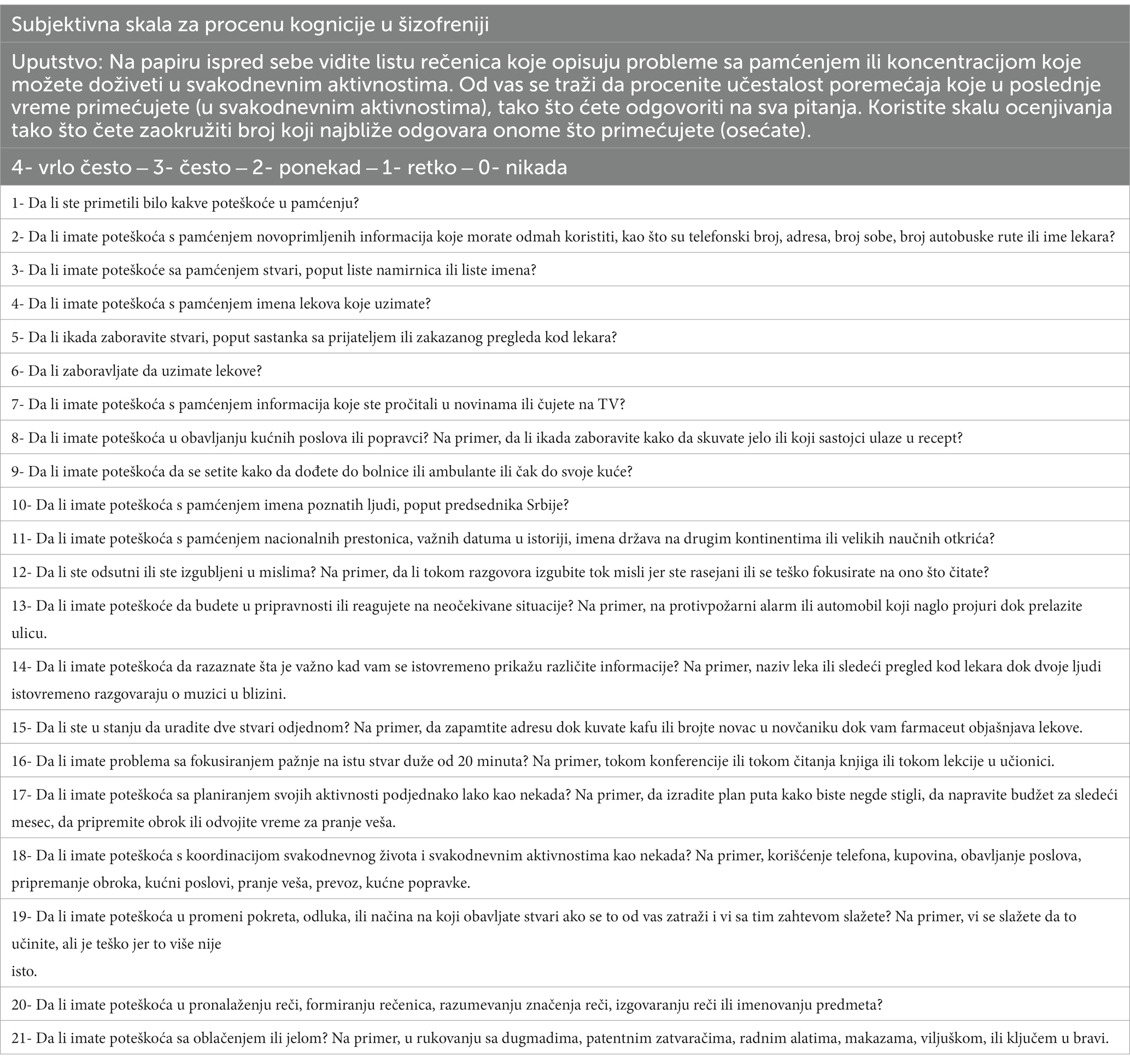

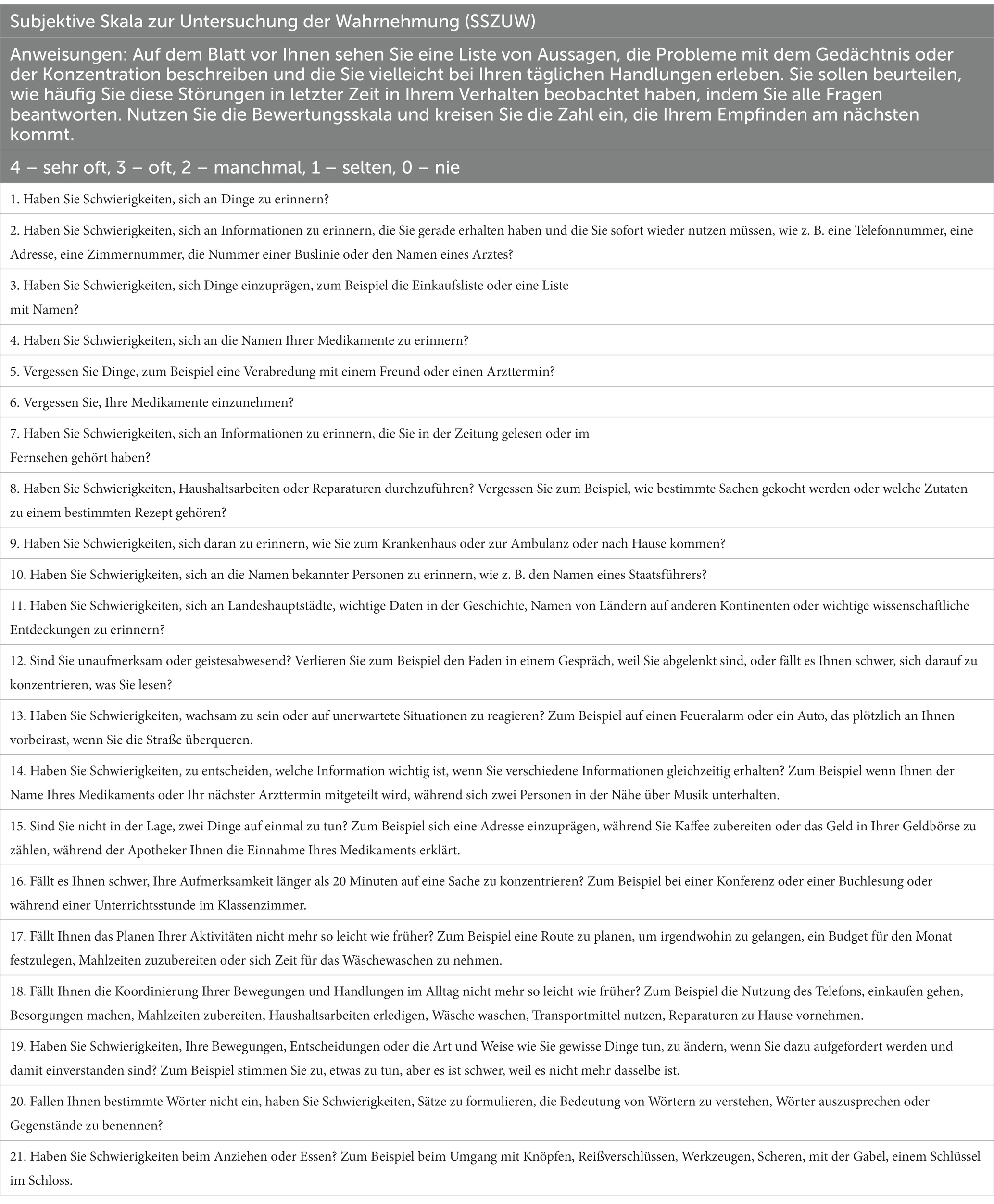

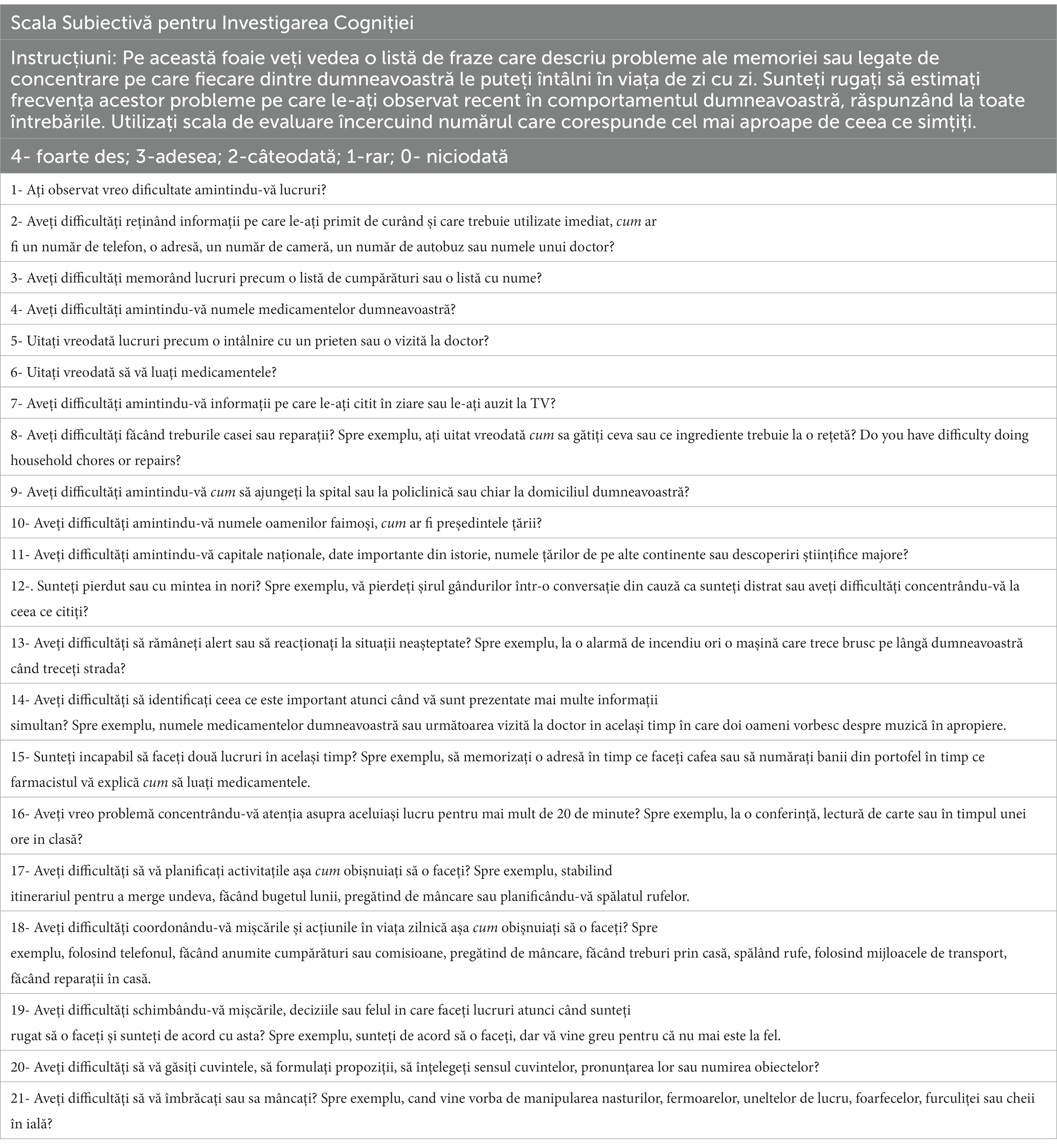

Specifically, we aimed to (1) translate the SSTICS into UAE Arabic; (2) explain the cultural adjustment needed to make the scale applicable and adjusted to suit the UAE; (3) present and post the scale and make it available to clinicians, readers, and researchers who are planning to validate it in the UAE. (4) We tested the feasibility of it in the UAE with a pilot (N = 13) and an exploratory study (N = 23). (5) Additionally, we added comparisons for the scale back-translations in different 9 languages, that can be used and validated in those countries, as well as for patients with those nationalities living in UAE such as Egyptian Arabic, Pakistan/Urdu, Hindi, Marathi, Lithuanian, Serbian, German, Romanian, Sinhala, and Russian (Table 8).

Method (Arabic)

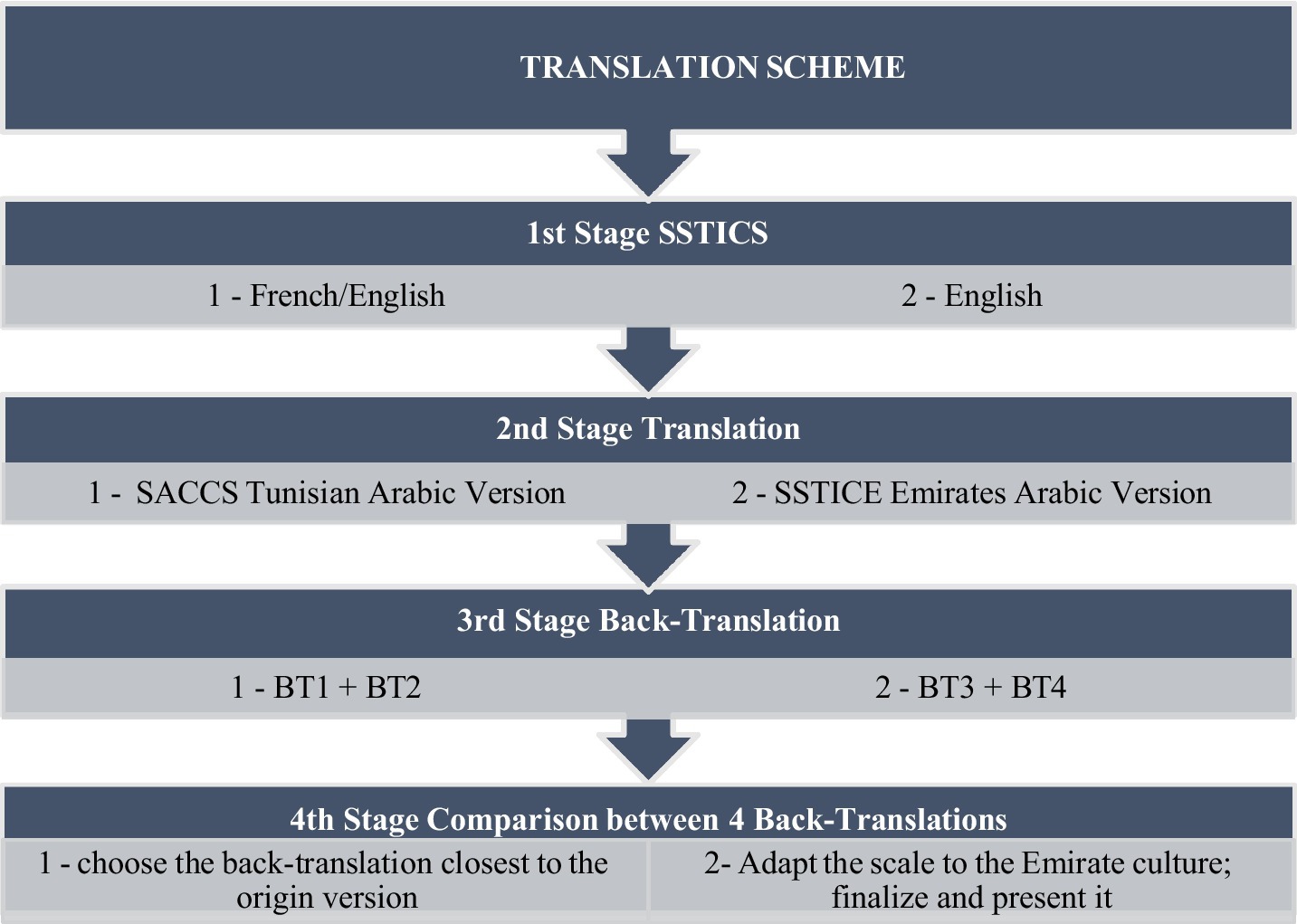

The initial translation aims to develop the first version of the tool in the language used in the UAE. A native speaker of both languages Arabic and English did the initial translation. The first step in developing a subjective scale to investigate cognitive deficits in the Emirate population was performed through four main stages. The first stage was the examination of the two versions of (SSTICS), the initial French language version that was translated to Tunisian Arabic (SACCS) and the English language version (SSTICS). The second stage was the translation (by a single researcher) of the English SSTICS into a second translated Arabic version in the Emirates Arabic language, named the Subjective Scale to Investigate Cognition in Emirates (SSTICE).

The third stage involved translating the two Arabic SSTICS versions (SACCS and SSTICE) back into the English language. Two independent researchers processed each scale version, each blind to the other “investigator’s work.” After completing this stage, we obtained four different back-translations (two back-translations for each scale), performed by four independent researchers. In the fourth stage, one reviewer compared the four translations and chose the version most like the original English-language SSTICS, so that adaptation and validation could be performed, and the final version of SSTICE-GCC was presented (Figure 1). The author of the scale (ES) reviewed all the versions.

During the harmonization stage, meetings were held between the different people involved in translation to examine the divergent items and concepts and ensure inter-translation validity. During these meetings, participants made decisions regarding concepts identified as potentially problematic or confusing in the instructions’ meaning and understanding. When necessary, the author of the tool has provided clarifications on the meaning of the concepts so that the Arabic version is as faithful as possible to the original. Decisions made by meeting participants were noted, and a draft of the tool was developed.

We provided the final version of the scale to (N = 13) residents in psychiatry to check the visibility and preference, and to ensure the understanding of each item by the participants. For each word questioned by participants or not understood, the final version was reviewed and adapted by the two translators by consensus. The step of reviewing the results of the application and finalization allows us to make the last necessary changes in the preliminary tool. The instructions for the various items were well understood by clinicians and were easily administered; few reformulations were necessary (Table 9).

Results

Results (Arabic)

The Arabic language is known for its complexity and richness of vocabulary. Its singularity appears from its designation. If one mentions Arabic without an adjective, some will understand that it is classical Arabic, which is also called literary, literal, or Koranic. Others perhaps, less numerous, would consider it dialectal Arabic, i.e., one of the forms of Arabic spoken in the Maghreb like Tunisia or Saharan Africa (Mauritania) or the East (Egyptian, Sudanese, Chadians, Saudis, Jordanians, Palestinians, Lebanese, Syrians, Iraqis, speak of Dathina, Hadramawt, Yemeni, and Omani).

Diglossia that prevails in the Arab world, namely the existence of a literary variant reserved for written use and the dialectal variants that are spoken in the various Arab countries, might be very old. The Koranic Arabic was not a spoken language whose dialects would be emitted historically but a standard of prestige in which the prophet received and wanted to transmit the revelation of Islam. In addition, literary Arabic is currently used in all Arabic literature. It can be used on the radio and television, in official speeches, in scientific communication, and in any other formal circumstance (Figure 2).

What nevertheless makes it possible to say that literary Arabic is not a spoken language in the ordinary sense of the term is, in fact, simple: it is not the mother tongue of people; the inhabitants of Arab countries speak and transmit to their children only the dialect of the country where they live. We know that Arabic dialects can be quite different, even within the same geographic and cultural settings, and more so between two sets: an Emirati and a Moroccan may have trouble communicating, each speaking his/her dialect. In this case, using literary Arabic may be considered. However, because of the substantial heterogeneity of the levels of schooling and education, not every Arabic speaker knows literary Arabic well enough to use it in their oral communication. In addition, the use of literary Arabic in oral communication appears to most Arabic speakers as being artificial, the dialects alone having a reality as instruments of conversation (Table 10).

Translating and back-translating: from SSTICS to SSTICE

The initial translation aims to develop the first version of the tool in the language used in the UAE. A native speaker in both languages Arabic and English performed the initial translation. The process of adopting the SSTICS to produce the SSTIC-E was performed through four main stages:

• The first stage was the examination of the two versions of SSTICS, the initial French language version that was translated to Tunisian Arabic (SACCS) and the English language version (SSTICS).

• The second stage was the translation (by a single researcher) of the English SSTICS into the Arabic Emirati version language, named the Subjective Scale to Investigate Cognition in Emirates (SSTIC-E).

• In the third stage involved translating the two Arabic SSTICS versions (SASCCS and SSTIC-E) back into the English language. Two independent researchers processed each scale version, each blinded to the other “investigator’s work.” After completing this stage, we obtained four different back-translations (two back-translations for each scale), performed by four independent researchers.

• In the fourth stage, one reviewer compared the four translations and chose the version most like the original English-language SSTICS, so that adaptation and validation could be performed, and the final version of SSTICE-E was presented (Figure 1). The author of the scale (ES) reviewed all the versions.

Finally, in the harmonization stage, meetings were held between the different people involved in translation to examine the divergent items and concepts and ensure inter-translation validity. During these meetings, participants made decisions regarding concepts identified as potentially problematic or confusing in the meaning and understanding of the instructions. When necessary, the author of the tool has provided clarifications on the meaning of the concepts so that the Arabic version is as accurate as possible to the original. Decisions made by meeting participants were noted, and a draft of the tool was developed.

SSTIC-E piloting

We provided the final version of the scale to 13 residents in the Al Ain Hospital psychiatry clinic, the main goal was to check the translated version in terms of wording adaptability, visibility, and preferred language (Arabic or English) of using the SSTIC-E, as well as to ensure the understanding of each item of the scale by the participants. No obstacles were documented by participants, and all their comments were taken into consideration for a better and clearer version of the final Arabic version of the scale. The final version was reviewed and adapted by the two translators by consensus.

Additional step: comparison for SSTICS back-translation of 9 languages

To enhance the importance of linguistic and textual differences in a different type of cross-translation and cross-adaptation based on each country’s language, context, and culture, we received different versions of back-translation from different countries. All the unpublished translations are displayed in the supplementary section. These versions of the scales are Pakistani/Urdu, Hindi, Marathi, Lithuanian, Serbian, German, Romanian, Sinhala, and Russian.

When we compared the back-translations, we found slight differences in using alternative synonymous words without changing the general meanings of the sentences or the questions. Moreover, we found some of the back-translations had slightly different grammar, others added more words or used completely different vocabulary (for example, in some back-translations, they used “you face difficulty” and in other back-translations “you struggle,” also, some used “house maintenance” and some used “home repairs”).

Some of the back-translations we found typical as the original scale, those highlighted in light orange (original scale BT, and BT-Version 1, 3) and others also had typical back translations but differed slightly from the original scale, highlighted in light green (BT-Version 4, 5). We classified differences into two types: grammarian, and semantic and contextual.

Grammarian

Because most of the back-translations come from countries where English is not the first language, we have noticed some mistakes in grammar and punctuation. These variations may affect the context meanings because of their misplaced positions in the sentence or using the wrong verb or noun sometimes.

Semantic

Context and culture: The socio-political context would also have influenced the formulation of the question. For example, “Who is the first minister of Canada?” (Q #10) is a question related to explicit semantic memory. In some countries, the election of a first minister or president of the republic is every 4 or 5 years. In other countries, there is no election, and the leader is for life; this is the case with monarchical models. In the use of the scale in France, for example, we will instead ask who the president of the Republic is. In the Emirates, the question would be “What is the name of the leader of the country?”

In addition, the sociological context is not the same relative to cooking, laundry, etc. For example, Q.17 tests the executive tasks, but in the UAE culture, this question is not significant since Emirati citizens do not do laundry themselves, instead, they rely on house helpers or automatic laundries (see Supplementary Table S1). Considering that the SSTICS was developed from a construct of cognition, the adequacy between the question on executive functions and real life is crucial if one wants a minimum of ecological validity (Supplementary Table S1)

Discussion

Precautions

In this process, we had to choose between different methods such as the traditional translation. It simply consists of the translation by a bilingual researcher or professional translator of the original instrument. This method, used alone, is not recommended because it introduces significant bias, especially in the interpretation of the researcher or the translator. This difficulty can be overcome by performing several parallel translations by different bilingual translators or researchers, but the following methods are recommended. Therefore, the team was composed of several psychiatrists from different cultures within the Arab world.

The method of translation by a committee of experts involves participation in the translation of several bilingual people who know the field for which the instrument is intended, which also limits the bias of a single researcher. This committee can consider a first translated version or participate in the development of a first version. Under ideal conditions, if the author (ES) of the original version participates in it, this makes it possible to clarify certain ambiguities that the translation process generates. We were able at this stage to document certain differences in dialect and semantic usage. For instance:

Comments: “some minor comments on the translation.”

Some repeated words, some literal translations, and redirecting for the correct meanings of the words in Arabic. Here are some examples: all the texts written in Arabic are accompanied by an interlinear gloss, to help the reader follow the relationship between the source text and its translation, and the structure of the original language:

التعليمات: سترى على الورقة التي أمامك، قائمة من العبارات التي تصف بعض مشاكل الذاكرة أو التركيز والتي قد يواجهها كل منكم في أنشطته اليومية.جميع األسئلة عليك تقدير تكرار مثل هذه االضطرابات التي الحظتها مؤخراً في سلوكك، من خالل اإلجابة على.

2- Do you have difficulty remembering information that is freshly received and that must be used immediately, such as a telephone number, an address, a room number, a bus route number, or a doctor’s name?

12-Are you absent-minded or up in the clouds? For example, you lose your train of thought in a conversation because you are distracted, or you have a hard time focusing on what you are reading?

Back-translation implies that when the first version translated from the instrument has been produced, it is re-translated by a second person in its original language. The gap between the original version and the re-translated version identifies problematic items. This method can be even more sophisticated by performing two reverse translations in parallel, involving four people. This method can be considered ideal and was used. However, researchers who have used it find it challenging to obtain a perfect equivalence between the re-translated and original versions. For instance: Q# 20 Do you have difficulty finding words, making sentences, or understanding the meaning of words (may need to specify whether you mean written or spoken words)? or pronouncing them, or naming objects?

In addition, a recent study by Cella and colleagues showed that the SSTICS could be used as a screening measure and be completed by service users independently (Cella et al., 2020). However, item complexity may limit self-administration, which can affect item interpretation (Eremenco et al., 2005).

First use in UAE: exploratory and feasibility findings

As a first opportunity, a population of our area and hospital agreed to participate in our questionnaire when they had a follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. This gave us the opportunity to test the use of the SSTIC-E (UAE Arabic) with a sample of 23 subjects. The mean age of our sample was 30.18% (18–62) 62% were female. The mean SSTICS total score was 16.5 (SD:16.9), in accordance with scores found in previous studies using the SSTICS in similar samples (Mancini et al., 2002). Working memory 2.13 (SD 1.83); Explicit memory 6.20 (SD 6.02); Attention 4.65 (SD 4.12); Language 1.13 (SD 1.06); Praxis 0.19 (SD 0.46). No correlations were found with age since this sample size was small. The Ethical Board at UAEU accepted the project and every subject gave consent to participate.

Second, and although this article is not focused on carrying out a clinical validation study at this stage but rather on describing the processes to be respected beforehand in the cultural and linguistic validation of the construct, we summarize here the feasibility results obtained from a population in the Emirates: The Arabic version of the SSTIC-E was administered to a total of 210 participants, including 126 patients and 84 healthy control participants (Al Mugaddam, 2023). The healthy group has a lower mean score of 22.55 (SD = 12.04), with a range of scores from 1 to 63. On the other hand, the patient group has a higher mean score of 34.06 (SD = 15.19), with a range of scores from 1 to 73 (p < 0.001). Additionally, the scores are broken down into five cognitive domains: Memory, Attention, Executive Function, Language, and Praxia. In the Memory domain, the control group has a mean score of 13.50 (SD = 7.21), with a range of scores from 1 to 36, while the patient group has a mean score of 17.58 (SD = 8.22), with a range of scores from 0 to 38; (p = 0.0005). In the Attention domain, the control group has a mean score of 5.81 (SD = 3.65), with a range of scores from 0 to 16, while the patient group has a mean score of 9.68 (SD = 4.64), with a range of scores from 0 to 20; (p < 0.0001). In the Executive Function domain, the control group has a mean score of 3.01 (SD = 2.52), with a range of scores from 0 to 12, while the patient group has a mean score of 4.76 (SD = 3.29), with a range of scores from 0 to 12; (p = 0.0002). In the Language domain, the control group has a mean score of 0.90 (SD = 9.6), with a range of scores from 0 to 4, while the patient group has a mean score of 1.45 (SD = 1.25), with a range of scores from 0 to 4; (p = 0.0786). In the Praxia domain, the control group has a mean score of 0.24 (SD = 0.63), with a range of scores from 0 to 3, while the patient group has a mean score of 0.76 (SD = 1.15), with a range of scores from 0 to 4; (p = 0.0009). To explore comparison, we compared the proportions between the control and patient groups for the SSTIC-E Scores, performing independent sample t-tests for each domain of the SSTIC-E score. In all domains except for Language, the mean scores of the patient groups were significantly higher than those of the control group, indicating worse performance in cognitive functioning. The effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were moderate to large for all domains except for Language, where the effect size was small. Overall, the patient group has higher scores in all domains, indicating that they have more cognitive impairment than the control group. Comparing the study results with the literature, the total mean score on the SSTICS for Stip et al.’s (2003) study population was 25.94 (SD = ±9.72) (Stip et al., 2003), which is similar to the study findings by Raffard et al. (2020) in France, where patients scored 25.56 (SD = ±9.10), but lower than the score of our patient participants, 34.06 (SD = ±15.19). However, the control group in the latter study scored similar results (22.55, SD = ±7.87) (Raffard et al., 2020) to the control group of our study (22.55, SD = ±12.04).

Most of the studies had SSTICS mean scores relatively close to our study results. For example, Stratta et al. (2020) found a mean score of 23.34 (SD = ±14.91) when validating the SSTICS in an Italian patient population (Stratta et al., 2020), while Lecardeur et al. (2009) reported a mean score of 24.73 (SD = ±9.56) for patients with schizophrenia who had preserved awareness of their cognitive deficits, as measured by the SSTICS (Lecardeur et al., 2009). In contrast, Haddad et al. (2021) found that subjective cognitive complaints were associated with poorer cognitive performance in Lebanese patients with schizophrenia, with patients scoring 25.15 (SD = 16.67; min = 0, max = 76; median = 23.50) and controls scoring 9.15 (SD = 7.63; min = 0, max = 37; median = 7.00) (Haddad et al., 2021). The lowest mean score for SSTICS among patients was reported by Baliga et al. (2020) in India, with a mean score of 16.22 (SD = ± 10.8) (Baliga et al., 2022). Similarly, Shin et al. (2016) in Korea reported a mean SSTICS score of 18.9 (SD = ±14.3) for patients, Shin et al. (2016) and Chuang et al. (2019) in Taiwan found a mean SSTICS score of 16.22 (SD = ± 10.8) for their study population of patient participants (Chuang et al., 2019).

Applications

The intended application of translated versions is multiple depending on the languages and countries where the scale may be useful. In the Emirates, it gives the possibility of choosing a version, depending on the origin of the person tested, their mother tongue, or the language they use at home, so that the complaint best reflects their cognitive reality. The diversity of the authors of the article reflects this concern and may reflect the motivation of a healthcare professional to use the scale with a variety of people. Additionally, the scale can be used by professionals who propose a cognitive remediation plan. For example, neurocognitive disorders, which affect approximately 80% of people with schizophrenia, are present from the first psychotic episode. They must be objectified as soon as possible. A neuropsychological evaluation is considered when a cognitive complaint is formulated. Such a complaint may initially be raised by the SSTIC-E. In this case, a neuropsychological assessment and an assessment of social cognition are implemented. In the end, the results must be returned to the patient, so that they can take ownership of them. The preserved processes on which they can rely on to recover are put into perspective with those that are altered so that they can manage them as best as possible. The application will also eventually be broadened in transdiagnostic approaches. In certain geographic or economic situations, there are no means to carry out a complete neuropsychological assessment. The scale will still provide a signal of cognitive difficulty. Finally, the scale can be used in clinical or epidemiological research.

Conclusion

In summary, in the back-translation, the translation from the languages used in the UAE, including Arabic, was re-translated into English. Subsequently, a revision of the reverse translation was performed. This involves comparing the version translated back into English with the original version of the measurement tool to ensure the equivalence of the concepts. Both versions have been revised to identify any discrepancies. Problematic items were reviewed, and the Arabic version and other languages were improved accordingly.

Instrument developers face many challenges in developing translations. Multi-step procedures should be used, with bilingual and bicultural experts working independently or in committee and using mixed qualitative and quantitative methods to test translations. It remains difficult to achieve 100% equivalence (Beaton et al., 2000).

The study presented provides the first version of SSTICS intended for cross-cultural validation. The role of the translator’s team was to produce a text that could convey meaning to the receptors of the target culture, i.e., in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries (GCC). The team tried to respect the rule of intra-textual coherence, which stipulates that the target text (translates) must be sufficiently intelligible for the receiver and have a communicative and cultural meaning, as a part of his world of reference, for instance in Dubai or Abu Dhabi. The future use of the SSTIC-E cross-culturally adapted to the UAE will be a starting point for comparisons and further studies using this scale in the UAE and the Gulf region. Epidemiological studies using assessment scales such as SSTICS help bridge healthcare professionals and policymakers and help establish the best medical practices, policies, and interventions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by United Arab Emirates University, Social Sciences Ethical Committee (UAEU-SSeC), (ERS_2021_8418). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ES created the scale and the design of the study, supervised the process, and wrote the first version of this manuscript. FA translated SSTICS from English to Arabic and the final modification of the Arabic scale (SSTIC-E). LA and KA made substantial contributions to the first back-translation of SSTICS from the Arabic version into English. AO made substantial contributions to the second back-translation of SACCS, the Arabic Tunisian version into English. DA made substantial contributions in comparing the four back-translations and chose the most similar one to the original SSTICS. SJ was responsible for the version in Urdu. AS and RB were responsible for the versions in Hindi and Marathi. SW was responsible for the Sinhala version. EA was responsible for the German version. VA was responsible for the Lithuanian version. AM-M was involved in the first study with SSTICS and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and accepted to be accountable for the content of the study.

Acknowledgments

Iffat Elbarazi for supervising of the PhD of FM.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1125990/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdel Aziz, K., Aly El-Gabry, D., Al-Sabousi, M., Al-Hassani, G., Ragheb, M. M., Elhassan Elamin, M., et al. (2021). Pattern of psychiatric in-patient admissions in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. BJPsych Int. 18, 46–50. doi: 10.1192/bji.2020.54

Al Mugaddam, F. (2023). First step for the cross-validation of the arabic emirate version of “the subjective scale to investigate cognition-emirates”(sstic-e). Populat. Med. 5:A1295. doi: 10.18332/popmed/164636

Al-Darmaki, F. R. (2003). Attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help: what really counts for United Arab Emirates university students? Soc. Behav. Pers. 31, 497–508. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2003.31.5.497

Al-Darmaki, F. R. (2004). Counselor training, anxiety, and counseling self-efficacy: implications for training psychology students from the United Arab Emirates University. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 32, 429–439. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2004.32.5.429

Anderson, T., Ogles, B. M., Patterson, C. L., Lambert, M. J., and Vermeersch, D. A. (2009). Therapist effects: facilitative interpersonal skills as a predictor of therapist success. J. Clin. Psychol. 65, 755–768. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20583

Baliga, S. P., Kamath, R. M., and Kedare, J. S. (2020). Subjective cognitive complaints and its relation to objective cognitive performance, clinical profile, clinical insight, and social functioning in patients of schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. Indian J. Psychiatry 62, 178–185. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_639_19

Bayard, S., Capdevielle, D., Boulenger, J.-P., and Raffard, S. (2009). Dissociating self-reported cognitive complaints from clinical insight in schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry 24, 251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.12.010

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., and Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 25, 3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

Bengochea Seco, R., Gil Sanz, D., Fernández Modamio, M., Arrieta Rodríguez, M., Sánchez Calleja, R., Prat Solís, R., et al. (2010). Cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: relationship with insight and other cognitive measures. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 3, 55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2010.03.002

Bora, E. (2017). Relationship between insight and theory of mind in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 190, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.029

Bouhamed, M., Sallemi, R., Kolsi, S., Feki, I., and Masmoudi, J. (2021). The factors associated with subjective cognitive complaints in schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry 64:S545. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.1453

Bravo, M., Canino, G. J., Rubio-Stipec, M., and Woodbury-Fariña, M. (1991). A cross-cultural adaptation of a psychiatric epidemiologic instrument: the diagnostic interview schedule’s adaptation in Puerto Rico. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 15, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00050825

Bullinger, M., Anderson, R., Cella, D., and Aaronson, N. (1993). Developing and evaluating cross- cultural instruments from minimum requirements to optimal models. Qual. Life Res. 2, 451–459. doi: 10.1007/BF00422219

Capitulo, K. L., Cornelio, M. A., and Lenz, E. R. (2001). Translating the short version of the perinatal grief scale: process and challenges. Appl. Nurs. Res. 14, 165–170. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2001.22377

Cella, M., Bodnar, M., Lepage, M., Malla, A., Joober, R., Iyer, S., et al. (2020). Investigating subjective cognitive complaints in psychosis: introducing the brief scale to investigate cognition in schizophrenia (SSTICS-brief). Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 25, 190–200. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2020.1722084

Chuang, S. P., Wu, J. Y. W., and Wang, C. S. (2019). Self-perception of mental illness, and subjective and objective cognitive functioning in people with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 15, 967–976. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S193239

Craik, F. I. M., and Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 11, 671–684. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Dam, J. (2006). Insight in schizophrenia: a review. Nord. J. Psychiatry 60, 114–120. doi: 10.1080/08039480600600185

Duffy, M. E. (2006). Translating instruments into other languages: basic considerations. Clin. Nurse Spec. 20, 225–226. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200609000-00006

El-Islam, M. F. (2005). Some cultural aspects of the Arab patient–doctor relationship. Int. Psychiatry 2, 18–20. doi: 10.1192/S1749367600007116

Epstein, J., Santo, R. M., and Guillemin, F. (2015). A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 68, 435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.021

Eremenco, S. L., Cella, D., and Arnold, B. J. (2005). A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval. Health Prof. 28, 212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342

Flaherty, J. A., Gaviria, F. M., Pathak, D., Mitchell, T., Wintrob, R., Richman, J. A., et al. (1988). Developing instruments for cross-cultural psychiatric research. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 176, 257–263. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198805000-00001

Gebreegziabhere, Y., Habatmu, K., Mihretu, A., Cella, M., and Alem, A. (2022). Cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia: an umbrella review. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 272, 1139–1155. doi: 10.1007/s00406-022-01416-6

Guillemin, F., Bombardier, C., and Beaton, D. (1993). Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 46, 1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n

Haccoun, R. R. (1987). Une nouvelle technique de vértification de l’équivalence de mesures psychologiques traduites. [A new technique for verifying the equivalence of translated psychological measures]. Revue Québécoise de Psychologie 8, 30–39.

Haddad, C., Salameh, P., Sacre, H., Polin, C., Clément, J.-P., and Calvet, B. (2021). Subjective cognitive complaints and relations to objective cognitive performance among Lebanese patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 21:549. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03564-w

Hilton, A., and Skrutkowski, M. (2002). Translating instruments into other languages: development and testing processes. Cancer Nurs. 25, 1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00001

Homayoun, S., Nadeau-Marcotte, F., Luck, D., and Stip, E. (2011). Subjective and objective cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia—is there a link? Front. Psychol. 2:148. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00148

Hunt, X., and Swartz, L. (2017). Psychotherapy with a language interpreter: considerations and cautions for practice. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 47, 97–109. doi: 10.1177/0081246316650840

Johnson, I., Kebir, O., Ben Azouz, O., Dellagi, L., Rabah, Y., and Tabbane, K. (2009). The self- assessment scale of cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: a validation study in Tunisian population. BMC Psychiatry 9:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-66

Lecardeur, L., Briand, C., Prouteau, A., Lalonde, P., Nicole, L., Lesage, A., et al. (2009). Preserved awareness of their cognitive deficits in patients with schizophrenia: convergent validity of the SSTICS. Schizophr. Res. 107, 303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.003

Miller, K. E., Martell, Z. L., Pazdirek, L., Caruth, M., and Lopez, D. (2005). The role of interpreters in psychotherapy with refugees: an exploratory study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 75, 27–39. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.27

Okasha, A., Rafaat, M., Mahallawy, N., Nahas, G. E., Dawla, A. S. E., Sayed, M., et al. (2000). Cognitive dysfunction in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 101, 281–285. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101004281.x

Potvin, S., Pelletier, J., and Stip, E. (2014). Neurocognitive insight in schizophrenia: a meta- analysis. Sante Mentale Au Quebec 39, 183–200. doi: 10.7202/1027839ar

Prouteau, A., Verdoux, H., Briand, C., Lesage, A., Lalonde, P., Nicole, L., et al. (2004). Self-assessed cognitive dysfunction and objective performance in outpatients with schizophrenia participating in a rehabilitation program. Schizophr. Res. 69, 85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.011

Sayed, M. A. (2003). Conceptualization of mental illness within Arab cultures: meeting challenges in cross-cultural settings. Soc. Behav. Pers. 31, 333–341. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2003.31.4.333

Sellwood, W., Morrison, A. P., Beck, R., Heffernan, S., Law, H., and Bentall, R. P. (2013). Subjective cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: relation to antipsychotic medication dose, actual cognitive performance, insight and symptoms. PLoS One 8:e83774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083774

Shin, Y.-J., Joo, Y.-H., and Kim, J.-H. (2016). Self-perceived cognitive deficits and their relationship with internalized stigma and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 12, 1411–1417. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S108537

Stip, E. (1996). Memory impairment in schizophrenia: perspectives from psychopathology and pharmacotherapy. Can. J. Psychiatry 41, S27–S34. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100822

Stip, E., Al Mugaddam, F., Nauman, J., Baki, A. A., and Potvin, S. (2022). Subjective cognitive complaints in first episode psychosis: a focused follow-up on sex effect and alcohol usage. Schizophrenia Res. Cogn. 30:100267. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2022.100267

Stip, E., Caron, J., Renaud, S., Pampoulova, T., and Lecomte, Y. (2003). Exploring cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: the subjective scale to investigate cognition in schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry 44, 331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00086-5

Stratta, P., Pacitti, F., Rossi, R., Chialastri, S., Santarelli, V., Marucci, C., et al. (2020). Subjective scale to investigate cognition in schizophrenia (SSTICS): a validation study in Italian population. Riv. Psichiatr. 55, 98–105. doi: 10.1708/3333.33024

Keywords: SSTICS, subjective cognition, cognitive complaints, memory assessment, meta-cognition, schizophrenia, Arabic translation, cognitive scale

Citation: Stip E, Al Mugaddam F, Abdel Aziz K, Amiri L, Javaid SF, Arnone D, Almheiri E, Al Helali A, Oulhaj A, Statsenko Y, Ljubisavljevic MR, Wanigaratne S, Lungu O, Karpauskaite D, Aksionova V, Subbarayan A, Bangalore RP and Mancini-Marie A (2024) Cross-cultural differences through subjective cognition: illustration in translatology with the SSTIC-E in the UAE. Front. Psychol. 15:1125990. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1125990

Edited by:

Prakash Padakannaya, Christ University, IndiaReviewed by:

Padmavati Ramachandran, Schizophrenia Research Foundation, IndiaThaddeus Alfonso, Christ University, India

Copyright © 2024 Stip, Al Mugaddam, Abdel Aziz, Amiri, Javaid, Arnone, Almheiri, Al Helali, Oulhaj, Statsenko, Ljubisavljevic, Wanigaratne, Lungu, Karpauskaite, Aksionova, Subbarayan, Bangalore and Mancini-Marie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emmanuel Stip, ZW1tYW51ZWwuc3RpcEB1bW9udHJlYWwuY2E=

Emmanuel Stip

Emmanuel Stip Fadwa Al Mugaddam

Fadwa Al Mugaddam Karim Abdel Aziz

Karim Abdel Aziz Leena Amiri2

Leena Amiri2 Syed Fahad Javaid

Syed Fahad Javaid Danilo Arnone

Danilo Arnone Abderrahim Oulhaj

Abderrahim Oulhaj Yauhen Statsenko

Yauhen Statsenko Milos R. Ljubisavljevic

Milos R. Ljubisavljevic Ovidiu Lungu

Ovidiu Lungu Aravinthan Subbarayan

Aravinthan Subbarayan Adham Mancini-Marie

Adham Mancini-Marie