94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 08 January 2024

Sec. Developmental Psychology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1290911

This article is part of the Research Topic Parental Influence on Child Social and Emotional Functioning View all 17 articles

This study explores the effects of authoritarian parenting styles on children’s peer interactions, an aspect often overlooked in the existing literature that primarily focuses on family environmental factors. Data was collected through anonymous child-report questionnaires completed by 2,303 parents and teachers of children aged 3–6 years. The findings reveal that (1) authoritarian parenting significantly hinders children’s peer interactions; (2) the negative effects of authoritarian parenting differ based on gender, age, and family composition: (a) girls generally exhibit higher peer interactions than boys, with authoritarian parenting having a stronger impact on boys’ peer interactions; (b) peer interactions increase significantly with age, and younger children are more susceptible to the negative effects of authoritarian parenting; (c) children with siblings have higher peer interactions, and authoritarian parenting style has a greater influence on their interactions compared to only children. The study discusses potential reasons and provides practical suggestions for families to make informed parenting style choices based on these findings.

Social development plays a crucial role in fostering a well-adjusted personality in children, and the capacity for social support is instrumental in promoting positive psychosocial development, serving as a valuable resource and protective factor. These aspects form the bedrock for establishing positive peer relationships and nurturing physical and mental well-being (Perren et al., 2012; Perren and Diebold, 2017). The quality of peer relationships primarily hinges on children’s proficiency in interacting with their peers, serving as a key indicator of their social development (Zhang et al., 2022). Recognizing the significance of physical and mental development in school-age children, along with the paramount importance of education quality, the new round of preschool education reform in China highlights the Guidelines for the Learning and Development of Children Aged 3–6. These guidelines underscore the importance of attending to children’s peer interactions, as building positive peer relationships constitutes the initial step in children’s social adaptation and plays a pivotal role in enhancing their mental well-being (Tian, 2019).

Existing research both at home and abroad indicates that individuals with an interdependent self-concept often display collectivist traits. They can maintain a collective equilibrium by adjusting their speech and actions to changing situations, fostering harmonious relationships with their peer group (Zhou et al., 2014). Failing to establish appropriate peer interactions can negatively impact children’s social adjustment and interpersonal development in adulthood (Bosacki, 2015). Such adverse peer interactions not only affect children’s social development but also increase the risk of depression and autism (Gong and Liu, 2004). Consequently, scholars have increasingly focused on studying children’s peer interaction abilities, making it a prominent research area in the field of child sociality (Pang et al., 1997). Consequently, considering the widespread presence of authoritarian family structures in China, coupled with the significant focus on children’s peer interactions across various nations, it becomes critically important to investigate the mechanisms through which the authoritarian parenting style influences children’s peer interactions in China, and to examine its diverse effects.

The formation and development of children’s peer interactions are complex and multidimensional. Previous scholars, both domestic and international, have explored the relationship between children’s peer interactions and various factors, such as parenting style (Mikami et al., 2010; Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2019), teacher-student interactions (Luckner and Pianta, 2011), socio-emotional development (Chen, 2012), and classroom learning (Howe and Mercer, 2007), among other perspectives that encompass multiple domains and dimensions. Parenting style, in particular, plays a fundamental role in children’s social development and significantly impacts peer interactions (Hosokawa and Katsura, 2019; Sahithya et al., 2019; Mak et al., 2020). Parenting styles involve varying attitudes and methods parents use in child-rearing (Darling and Steinberg, 1993). Typically, two central facets define parenting techniques: a parent’s responsiveness and their level of demands (Lamborn et al., 1991; Villarejo et al., 2023). Responsiveness generally refers to a parent’s warmth, active engagement, and support for their child’s individuality (Baumrind, 1991; Climent-Galarza et al., 2022). Conversely, demandingness indicates the degree of rigidity and standards parents establish, aligning with societal or household values (Steinberg et al., 1994; Palacios et al., 2022). Given these two dimensions, researchers have identified distinct parenting categories, such as authoritative, authoritarian, neglectful, and indulgent parenting styles (Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994; Villarejo et al., 2023).

Cultural nuances can play a pivotal role in shaping the relationship between parenting techniques and child adaptation (Pinquart and Kauser, 2018; Garcia et al., 2019). Some studies have found that parenting styles in Asian contexts, particularly in Pakistan, tend to lean towards an authoritarian approach. Children raised by authoritative parents exhibit elevated levels of aggressive behavior and emotional instability (Anjum et al., 2019). Within the Chinese cultural and social milieu, a child deemed “well-behaved and aware” is often one who has benefitted from effective parental guidance, encompassing both “discipline” and “instruction.” Rooted in Confucianism, Chinese moral culture emphasizes patriarchal hierarchies and the virtues of righteousness. Parents might resort to stringent disciplinary actions when children do not meet established standards, seeing this firmness as their duty (Chao, 1994). Such exacting parenting helps the young grasp their place in both family and society, aiding in their seamless assimilation into societal norms (Pan and Shang, 2023). Unlike Western parents, Chinese parents often resort to criticism and directives to achieve their expectations of their children when it comes to raising educated, high-achieving family members. This is especially true in areas like academic achievements and the pursuits of the children, showcasing a distinct authoritarian inclination among Chinese parents (Dornbusch et al., 2016; Ren et al., 2022).

Parenting styles encompass a combination of parenting attitudes, methods, behaviors, and emotional expressions conveyed through parents’ responses to their children in daily life, demonstrating cross-situational stability (Darling and Steinberg, 2017). They play a vital role in promoting positive adaptive development (Delvecchio et al., 2020), aligning with Gottman’s research on family emotional life (Gottman et al., 1996). Pivotal research conducted in the United States, primarily focusing on middle-class European-American families, has demonstrated that parenting characterized by a blend of demandingness, as observed in the authoritative style, is correlated with psychosocial benefits (Darling and Steinberg, 1993; Steinberg and Morris, 2001). Conversely, a parenting approach that combines demandingness with a lack of responsiveness, characteristic of the authoritarian style, has been linked to significantly adverse outcomes (Darling and Steinberg, 1993; Steinberg, 2001). Children raised under authoritarian parenting tend to experience social impairments, lack social initiative, have difficulty expressing themselves, struggle to form close friendships, and often face rejection by their peers. Recent research conducted in Europe within middle-class family contexts has also established a correlation between the authoritarian parenting style and adverse consequences (Alcaide et al., 2023; Reyes et al., 2023). As a result, children’s behavior in peer interactions is rooted in the parenting styles they experience.

However, research on ethnic minority groups in the U.S., including African-Americans and Chinese-Americans, reveals a deviation from the European-American family patterns. Authoritarian parenting in these groups is not always harmful and can be beneficial (Baumrind, 1996; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996; Chao, 2001). Martínez et al. (2021) attribute these differences to varied family perceptions and self-esteem. African-American children under authoritarian parenting might feel familial love and connection, unlike their European-American counterparts, who may feel alienated (Baumrind, 1996; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996). This indicates the effects of authoritarian parenting on children’s social behavior vary across cultures. Understanding these parenting styles is crucial for promoting healthy peer interactions and preventing adverse psychological outcomes in children. This study aims to examine the impact of authoritarian parenting on children’s peer interactions in Asian cultures, characterized by collectivism and hierarchical relationships, to provide new insights into scientific parenting.

Firstly, as children grow older, their social cognition improves. They exhibit a decrease in the frequency of forceful displays and aggressive conflicts, and gradually realize the benefits of cooperation and sharing, leading to the establishment of intimate relationships (Green et al., 2008). Older children tend to communicate and comprehend more coherently due to better verbal skills, effectively manage socio-emotional conflicts to reduce social barriers, strengthen their social self-confidence, and foster improved peer interactions. However, children raised under authoritarian parenting styles, characterized by ordering, dictating, and controlling, often demonstrate higher dependency and obedience to their parents, lack assertiveness, exhibit poorer group sensitivity, and have lower psycho-theoretical maturity compared to their peers. They tend to view the self and peers as competitors for achievement (Xu et al., 2013), potentially leading to increased aggression. Conversely, children with strong and dominant personalities may find it challenging to maintain long-term peer relationships and experience higher frequencies of peer alienation (Xu et al., 2008).

Secondly, gender differences play a crucial role in child indicators and the manifestation of variations in child socialization (Wei et al., 2011). The peer socialization model suggests that boys and girls exhibit different patterns of social behavior and types of interaction. Girls tend to focus on smaller-scale interactions and are better at providing intimacy, support, and empathy within their social groups, resulting in higher initial levels of pro-social behavior and better peer interactions compared to boys (Van der Graaff et al., 2018). However, boys raised under authoritarian parenting styles have been found to display higher stress responses to group activities and exhibit more negative and hostile emotions. Their withdrawal in peer interactions increases the risk of social impairment and adherence to organizational rules (Wang and Gai, 2020). Another study found that harsh discipline by fathers significantly predicted internal problem behavior and life satisfaction in sons but not in daughters (Wu et al., 2017). This is because boys’ peer groups tend to be larger and engage in rougher play with more physical contact (Wang and Zhuang, 2012).

Thirdly, the one-child family has been the predominant family model in China since the full implementation of the country’s family planning policy in 1979 (Hao, 2012). Only children without siblings have been found to have poorer mental health compared to children with siblings. They face a higher risk of suicidal ideation, self-harm during conflicts, and an increased likelihood of drug dependence (Wang et al., 2019). Due to the absence of other sibling subsystems in the family, parental conflicts and family disputes can directly impact the emotional state of the only child (Hao and Feng, 2002). The adoption of an authoritarian parenting style not only hinders the development of only children but also contributes to negative emotions in their peer interactions, fostering competitive, hostile, and aggressive behavior, leading to a decline in the quality of peer relationships (Tippett and Wolke, 2015). Based on these findings, it is evident that the impact of authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions is influenced by their age, gender, and family structure. This relationship deserves considerable attention in research on family education and children’s social development practices.

Given China’s unique cultural background, the choice of parenting style and the establishment of peer relationships are geographically specific. Chinese parents place greater emphasis on children’s obedience and exert more control over them compared to Western parents (Luo et al., 2013; Ng et al., 2014). Moreover, Asian developing countries, including China, place considerable importance on developing an individual’s ability to inhibit emotions and impulses, viewing overexpression of negative emotions or impulsive behavior as a sign of immaturity (Chen et al., 2005). Children are encouraged to exercise self-control, which is considered a sign of achievement, mastery, and maturity in Confucian philosophy (Ho, 1986).

In conclusion, education in the group home is founded on principles of “Tao” and “Art,” with a primary focus on fostering comprehensive physical and mental development in children. The approach places particular emphasis on promoting emotional stability and appropriate behavior, which leads to the realization of intrinsic and social values in individuals. In summary, numerous studies have explored the theoretical and empirical aspects of authoritarian parenting style and its impact on peer interactions. However, few studies have delved into the profound effects and heterogeneity of authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions during early childhood. To address this gap, the current study aims to investigate the heterogeneous effects of authoritarian parenting style on the peer interactions of 3- to 6-year-old children. The research aims to provide targeted and effective parenting guidance for Chinese family education and raise awareness among families with authoritarian parenting styles about promoting their children’s social development while reducing internalization and externalization problems. Based on the aforementioned context, the following hypotheses have been formulated for this study:

Hypothesis 1: Authoritarian parenting style is hypothesized to have a significant negative impact on children’s peer interactions.

Hypothesis 2: Gender is hypothesized to moderate the effect of the authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions.

Hypothesis 3: Age is hypothesized to moderate the effect of the authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions.

Hypothesis 4: Number is hypothesized to moderate the effect of the authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions.

A total of 2,397 healthy children were recruited from 16 kindergartens, including both public and private ones, located in ten provinces across seven regions in China: North China, East China, South China, Central China, Northwest China, Southwest China, and Northeast China. The recruitment was conducted using stratified and randomized cluster sampling to ensure representative participation in this study. Questionnaires were distributed to parents and teachers of the participating children, with a total of 2,397 questionnaires successfully recovered, resulting in a 100% recovery rate. However, 94 questionnaires exhibited information mismatch and regularity in the answers and were consequently excluded. As a result, 2,303 valid questionnaires were obtained, corresponding to a questionnaire answer validity rate of 96.08%. Among the participants, 1,180 were boys (51.2%) and 1,123 were girls (48.8%). The age range of the children was from 3 to 6 years, and they were divided into two groups: 1,082 children (47%) in the 3–4 years old group and 1,221 children (53%) in the 4 years old or older group. The children were also categorized based on their kindergarten group size, with 784 (34%) in small groups, 782 (34%) in intermediate groups, and 737 (32%) in large groups. Additionally, 6.8% of the children lived in villages (totaling 157), 93% lived in towns (totaling 2,146), and none lived in cities. Furthermore, 9.8% of the children had divorced parents (totaling 98), while 95.7% had intact families (totaling 2,205). In terms of family structure, 46.4% of families had no second child (totaling 1,068), and 53.6% had a second child (totaling 1,235).

Authoritarian parenting style was assessed in this study using the Parenting Styles & Dimensions Questionnaire-Short Version (PSDQ-Short Version) (Robinson et al., 2001), which was developed by Robinson et al. The PSDQ-Short Version comprises 12 questions related to authoritarian parenting style. These questions gauge parents’ tendencies to display authoritarian behavior and their use of authoritarian practices with their children. This instrument quantifies the extent of authoritarian parenting practices and is completed by all participating parents. For instance, one of the items read, “I would be strict with my child to encourage improvement” (e.g., scolding, criticizing). Respondents rate their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always), with higher scores indicating a higher frequency of authoritarian parenting behavior by the parent. The scale has demonstrated robust reliability and excellent psychometric properties when tested with a group of Chinese participants (Li et al., 2012). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the authoritarian parenting style scale was 0.946.

Peer interactions. In this study, we employed the Peer Interaction Competence Scale for Young Children, developed by Zhang (2002). Several other studies have also utilized this questionnaire (Qin, 2022; Qin and Caizhen, 2022). The scale comprises 24 items that are categorized into four dimensions: social initiative, verbal and non-verbal interactions, social barriers, and pro-social behavior. Teachers completed the questionnaire based on their observations of the children’s daily academic and social performances. One of the sample items reads: “Children can organize a group of their peers to work collaboratively in the classroom.” A 4-point reverse Likert scale was utilized (1 = not at all, 4 = fully), with higher scores reflecting stronger peer interaction competencies. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale in this study was found to be 0.841, indicating a good level of internal consistency.

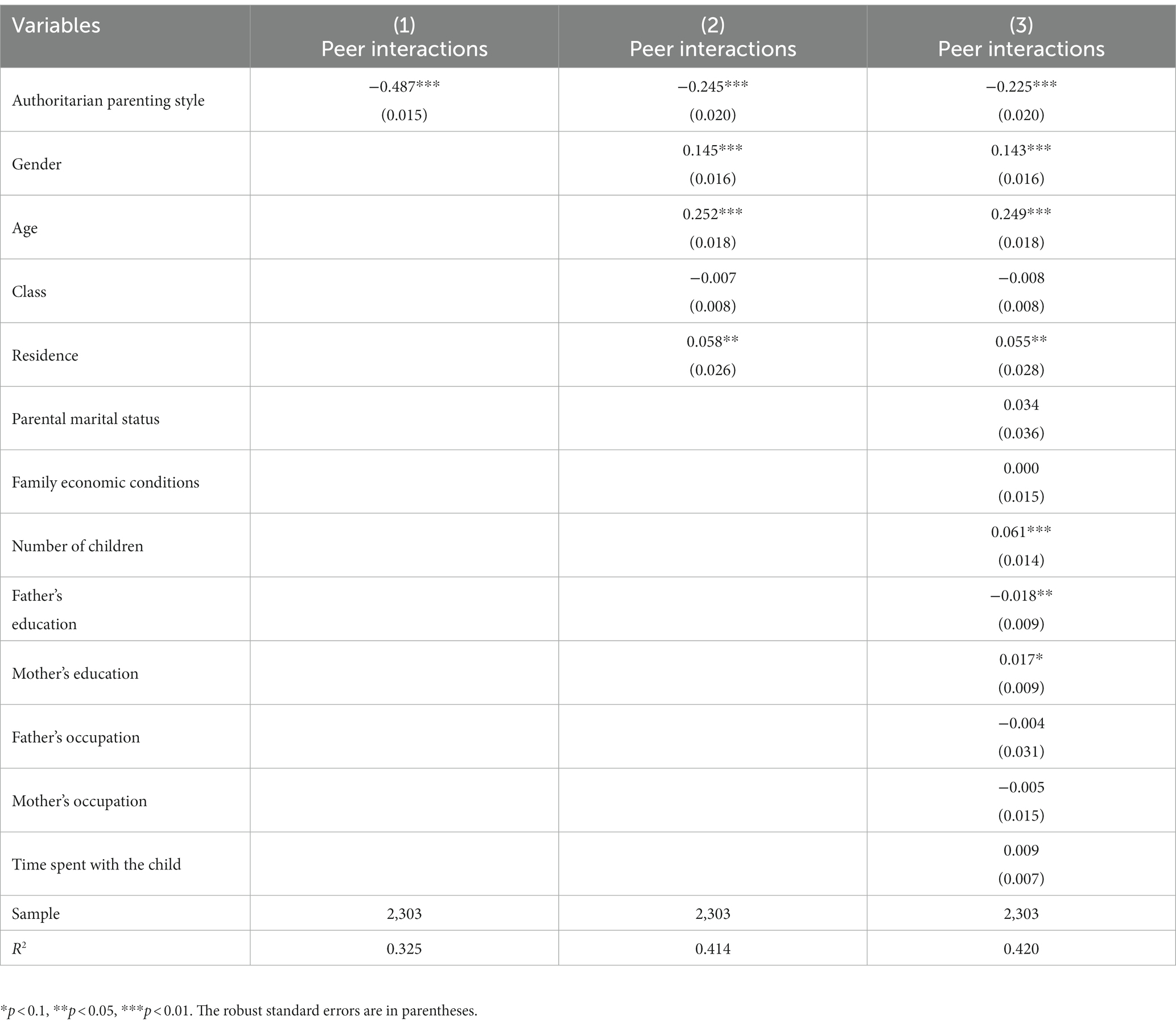

Considering the cultural variations between different regions, we carefully selected individual and family-level control variables that might have an impact on peer interactions and authoritarian parenting style in children aged 3–6 years. At the individual child level, the control variables included gender (coded as boy = 0), age (coded as 3–4 years = 0), class (coded as 1 = junior class), place of residence (coded as rural = 0), and parental marital status (coded as yes = 0 if parents were divorced). At the child’s family level, the control variables encompassed economic conditions, whether the child had a second sibling (coded as no = 0), educational levels of the father and mother, occupations of the father and mother, and the amount of daily time spent with the child by the parents. Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for all the variables employed in this study.

Prior to commencing the survey, the researchers sought consent from the local education authority and the participating schools. During the survey, essential information about the school campus was gathered from the principal and teachers. The researchers then provided a clear explanation of the study’s objectives and procedures to both parents and teachers before administering the questionnaires. The questionnaires were distributed during parent-teacher meetings conducted in classrooms. Before completing the questionnaires, participants provided written consent and were duly informed about the study’s purpose, confidentiality measures, and the guarantee of anonymity. To ensure consistent and accurate instructions, a trained postgraduate student thoroughly explained the study’s objectives and guidelines to the participants before they filled out the questionnaires. Following completion, the questionnaires were centrally collected and subjected to thorough verification. All research materials used in this study were thoroughly reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee of the corresponding author’s university.

The data were analysed using SPSS version 26.0 and STATA version 16.0 and consisted of four sections.

Firstly, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were performed to assess the relationships between the core variables.

Secondly, in analysing the impact of authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions, the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis was conducted in this process using a stepwise increase in the number of influencing factors, with the model formula:

where represents the score of the ith child’s peer interactions, represents the score of the ith child’s authoritarian parenting style, represents the kth control variable, is the intercept term, is the coefficient of for the authoritarian parenting style, is the coefficient of the control variable , and is the error term.

Thirdly, Generalised propensity score matching (GPSM) model was used to further identify the relationship between authoritarian parenting style and children’s peer interactions. And the robustness of OLS was tested based on the estimation of GPSM with the model equation:

where the treatment variable is authoritarian parenting style and the outcome variable is peer interactions. Firstly, the conditional probability density distribution of the treatment variable is estimated by GPSM based on the given covariates and the generalised propensity score is obtained. Therefore, the two factors that affect both the treatment variable and the outcome variable: the child and the family are selected as covariates. Then, by constructing an OLS regression model with the treatment variable and the generalised propensity score , the conditional expectation of the outcome variable was calculated and the coefficients were obtained. Finally, the range of values of the treatment variable was divided into a number of equally spaced consecutive intervals, and based on the coefficients obtained in the previous step, the average treatment effect (ATE) of was estimated within each interval (Chen et al., 2014).

Fourthly, the sample data were divided according to gender, age and number of children, and the Fisher permutation test (FP) was used to explore whether the results of the effect of authoritarian parenting styles on peer interaction skills varied according to gender, age and number of children.

All data in this study were collected through self-reports from both parents and teachers, potentially introducing common method bias. To address this concern, Harman’s one-factor test (Zhou and Long, 2004) was conducted. The results indicated the presence of four factors, each with an eigenvalue greater than 1. However, the first common factor accounted for only 21.027% of the variance, which was below the critical threshold of 40%. Consequently, it was concluded that there was no significant common method bias affecting the study.

Prior to conducting the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis on authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions, a multiple covariance test was conducted on models (1), (2), and (3). Based on the parents’ responses to the questionnaire, the maximum variance inflation factors for models (1), (2), and (3) were 1.00, 2.01, and 5.82, respectively, all of which were below the threshold of 10. These findings indicated the absence of significant multicollinearity issues in models (1), (2), and (3), allowing them to be subjected to OLS regression analysis.

To enhance the scientific validity and reliability of the regression results, multiple adjusted regressions were employed to analyze the impact of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions by gradually incorporating additional influencing factors (Equation 1). Model (1) only included the core variable of authoritarian parenting style. Model (2) introduced individual child characteristics as a dimension variable in addition to the core variable from model (1). Finally, based on model (2), model (3) included family characteristics as dimension variables (refer to Table 2). The testability index (Table 2) illustrates that as stepwise regression progresses, the models progressively incorporate more factors that affect peer interactions, resulting in an increase in the R2 values to 0.325, 0.414, and 0.420, respectively. This indicates that the models are well-constructed, and the inclusion of children’s individual characteristics and family characteristics contributes to a more comprehensive explanation of children’s peer interactions. In each of the models (1), (2), and (3), the estimated coefficients of authoritarian parenting style passed the 1% significance test, and all exhibited negative signs. This suggests that authoritarian parenting style significantly and adversely affects children’s peer interactions. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is validated.

Table 2. Results of the OLS benchmark regression on the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions.

Due to the non-normal distribution of the independent variable, authoritarian parenting style from the parent-completed questionnaires, it was standardized within the range of [0,1]. Subsequently, the fractional logit model was employed to estimate the conditional probability density of treatment intensity (Equation 2). The results indicated that the fractional logit model demonstrated a good fit, as evidenced by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value of 0.910. Among the selected control variables, child gender, child age, and whether the family had a second child exhibited the highest regression coefficients for authoritarian parenting style, surpassing other variables significantly. Furthermore, all three variables passed the 1% significance test, signifying their substantial impact on authoritarian parenting style (refer to Table 3).

The dose–response plots of authoritarian parenting style (Figure 1) demonstrated a significant decrease in the level of peer interactions as the level of authoritarian parenting style increased, even after controlling for GPSM. This indicates a consistent and robust negative correlation between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions, which aligns with the findings of the previous OLS regression analysis, reaffirming the strong impact of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions.

First, the baseline OLS regression results for model (3) in Table 2 reveal that child gender has a coefficient of 0.143 (p < 0.001) in the association between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions. Secondly, models (1) and (2) in Table 4 display the OLS regression results for the impact of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions separately for boys and girls. In both cases, the estimated coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level with negative signs. Notably, the absolute value of the regression coefficient for authoritarian parenting style on boys’ peer interactions (−0.271) is larger than that for girls’ peer interactions (−0.193). Furthermore, the results of Fisher’s exact test for the difference in gender coefficients concerning the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions are significant at the 5% level. These findings indicate that overall, girls’ peer interactions are higher than those of boys. Moreover, there is a gender heterogeneity effect in the relationship between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions, with the effect of authoritarian parenting style on boys’ peer interactions being more pronounced compared to girls. As a result, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed.

Firstly, the baseline OLS regression results for model (3) in Table 2 reveal a coefficient of 0.249 (p < 0.001) for children’s age in the relationship between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions. Secondly, models (1) and (2) in Table 5 present the OLS regression results for the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions for two age groups: 3–4 years old and 4–6 years old, respectively. In both cases, the estimated coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level with negative signs. Notably, the absolute value of the regression coefficient for authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions for children aged 3–4 years (−0.292) is greater than that for children aged 4–6 years (−0.177). Additionally, the empirical p-value of Fisher’s exact test for the variability of the age coefficient concerning the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions is significant at the 1% level. These findings indicate that the level of peer interactions significantly increases with age among children aged 3–6 years. Moreover, there is a child age heterogeneity effect in the relationship between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions, with the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions being more pronounced among children aged 3–4 years compared to children aged 4–6 years. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Firstly, the baseline OLS regression results for model (3) in Table 2 reveal a coefficient of 0.061 (p < 0.001) for the number of children in the family in the relationship between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions. Secondly, models (1) and (2) in Table 6 present the OLS regression results for the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions for two groups: children without a second child in the family and children with a second child in the family, respectively. In both cases, the estimated coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level with negative signs. Notably, the absolute value of the regression coefficient for authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions for children without a second child in the family (−0.300) is larger than that for children with a second child in the family (−0.168). Additionally, the empirical p-value of Fisher’s exact test for the variability of the number coefficients concerning the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions is significant at the 1% level. These findings indicate that children with a second child in the family have significantly more peer interactions than children without a second child in the family. Furthermore, there is a heterogeneous effect of the number of children on the relationship between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions, with the effect of authoritarian parenting style on peer interactions being more pronounced among children without a second child in the family compared to those with a second child in the family. Thus, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

The current study has revealed a significant negative predictive effect of authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions, which aligns with family systems theory and is consistent with previous research involving children and early adolescents (Chan et al., 2018; Obimakinde et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2021). During the child’s interactions with their parents, they observe and imitate the verbal and emotional expressions of family members, and they perceive the reactions of individuals to various stimuli. Consequently, when confronted with relevant situations during group interactions, children draw on the information they have absorbed from their parents to respond in a similar manner, mobilizing their own emotions and executive capabilities. Authoritarian parents’ attitudes are characterized by a lack of respect for their children’s opinions and excessive discipline, with limited feedback, encouragement, and approval. This consistent imposition of unreasonable demands gradually erodes the child’s personality development and reinforces negative parent–child interaction experiences (Liu and Feng, 2023). Over time, this parent–child dynamic can affect the child’s normal responses in peer interactions, rendering them susceptible to intense emotions and aggressive behavior, leading to victimization by peers.

In systems theory, the peer connections of children are seen as a unique system, heavily influenced by family dynamics. The characteristics and behavior patterns within a family, especially those of authoritarian parents, greatly shape children’s interactions with peers (Brown and Bakken, 2011). Children exposed to authoritarian parenting often misinterpret peer actions as hostile, which leads to their alienation and possibly to their withdrawal from social groups (Ros and Graziano, 2018). This social impairment places them at risk of isolation from their peers. Furthermore, in the absence of social support, children might resort to rumination instead of seeking coping mechanisms to handle stress or negative emotions. This can increase their likelihood of developing depressive tendencies (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Authoritarian parenting, characterized by low warmth and high punitive demands, can have detrimental effects on children both at the group and individual levels. High levels of parental authoritarianism correlate with more problematic peer interactions, poor social relationships, and negative social interaction patterns. In structured group settings, some children may react to the restrictive nature of authoritarian parenting by violating established norms or by becoming socially withdrawn and “invisible” to their peers. Both outcomes hinder the development of positive peer interactions, negatively affecting children’s physical and mental well-being and impeding their social development.

This study also revealed heterogeneous effects of gender, age, and the number of children on the negative impacts of authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions.

Firstly, research indicates that girls generally have more peer interactions than boys, influenced by the authoritarian parenting style, which affects boys more significantly. This disparity aligns with Social Role Theory (Eagly, 2013), suggesting societal expectations and gender roles shape emotional and behavioral development. Girls often show obedience, while boys demonstrate assertiveness and defiance, reflecting societal teachings of gender-specific traits (Eagly, 2009). Children internalize these gender characteristics, influencing their focus and processing of gender-related information (Hilt et al., 2010). In peer interactions, girls prioritize relationships and support, using positive strategies during conflicts, thus promoting prosocial behavior (Jahromi et al., 2021). Boys, conversely, focus on game-related emotions, prefer temporary group dynamics, and may resort to aggressive conflict resolution, often exacerbating peer issues. These patterns suggest the need for parental awareness of children’s peer interaction styles, especially among boys, where negative interactions and behaviors are more prevalent.

Secondly, the study’s findings revealed a significant increase in the level of peer interactions among children aged 3–6 years with advancing age. Additionally, the impact of authoritarian parenting on peer interactions was found to be more pronounced among children aged 3–4 years compared to those aged 4–6 years, which aligns with previous research (Zheng, 2018). Physiologically, the prefrontal lobe of a child’s brain undergoes gradual development alongside physical growth. This brain region plays a vital role in emotion regulation and behavioral inhibition, directly influencing children’s emotional responses and controlling their externalized behaviors. The findings of this research align with Gottman’s emotion-centric perspective on parenting approaches and offer insights into discerning if children exhibit positive or negative emotional inclinations (Jespersen et al., 2021). Moreover, the developmental theory of group socialization (Saara, 1951) posits that as children grow older, the proportion of their participation in peer groups significantly increases. Interactions in diverse social situations continually complement and fulfill children’s intrinsic needs for social engagement (Li, 2004). Consequently, their repertoire of peer interaction strategies becomes more varied (Elenbaas, 2019; Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2019), and they develop logical thinking when selecting interaction modes that align with the rules of the organization. With reduced dependency on the family for defining their social interactions and values (Sümer et al., 2019), they are more likely to develop self-validation and empathy for others, acquire positive peer interactions, and establish meaningful peer relationships.

Finally, the study’s findings also revealed that children with a second child in the family had significantly higher levels of peer interactions than children without a second child in the family. Moreover, authoritarian parenting style had a stronger impact on peer interactions for children without a second child in the family compared to those with a second child, consistent with a previous study (Cameron et al., 2013). In terms of family structure, children without a second child in the family bear the sole burden of family conflicts and the authoritarian control of their parents (Liu et al., 1988). This unique role may foster individualistic characteristics or an independent self-concept, making them assertive, but also prone to neglecting the feelings and needs of their peers. They may seek to impose their own expectations and achieve personal goals by altering external conditions, exhibiting a strong sense of self and independence. Consequently, in group settings, they may become demanding or even bullies, seeking the initiative and leadership that may be lacking at home and displaying emotional outbursts and problem behaviors that are rejected by their peers. From the perspective of the “erosion-convergence” theory of the dynamics of social influence, the differences in children’s psychological and behavioral outcomes are rooted in variations in family environment and parenting styles. Thus, in light of the recent opening of the three-child policy in China, further comparative investigations and in-depth probes into the effects of different family structures on children’s development are necessary to contribute to the advancement of scientific family and pre-school education.

After controlling for child- and family-related variables, the results of this study indicate that authoritarian parenting style is negatively correlated with peer interactions. There is gender, age, and number heterogeneity in the negative effects of authoritarian parenting style on children’s peer interactions: (a) Girls’ overall peer interactions are higher than boys’, and authoritarian parenting has a stronger impact on boys’ peer interactions than on girls. (b) Peer interactions among children aged 3 to 6 increase significantly with age, and authoritarian parenting style has a more pronounced effect on peer interactions of 3- to 4-year-olds than on those of 4- to 6-year-olds. (c) Peer interactions are significantly higher for children with a second child in the family than for only children, and authoritarian parenting style has a greater impact on peer interactions for children with a second child in the family than for only children. The implications of these findings are threefold: Firstly, it offers targeted and effective parenting advice for family education. Secondly, this study’s findings contribute to the expansion of family research into a broader international context. By exploring the nuances of family cultures in various countries, we aim to assimilate the most effective aspects of each. Thirdly, the observed diversity in parenting styles across different socioeconomic classes in various countries underscores the need for future research. Such studies could perform in-depth analyses of the relationship between children’s parenting styles, their peer interactions, and socioeconomic class.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee Review Board of Liaoning Normal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Foundation of Liaoning Province Education Administration’s Key Research Project for Universities (grant ID: LJKZR20220114) and the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China (grant ID: 23YJA880015).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alcaide, M., Garcia, O. F., Queiroz, P., and Garcia, F. (2023). Adjustment and maladjustment to later life: evidence about early experiences in the family. Front. Psychol. 14, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1059458

Anjum, A., Noor, T., and Sharif, N. (2019). Relationship between parenting styles and aggression in Pakistani adolescents. Khyber Med. Univ. J. 11, 98–101.

Baumrind, D. (1991). “Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition” in Advances in family research. Family transitions. eds. P. A. Cowan and E. M. Hetherington (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc), 111–163.

Baumrind, D. (1996). The discipline controversy revisited. Fam. Relat. 45, 405–414. doi: 10.2307/585170

Bosacki, S. L. (2015). Children’s theory of mind, self‐perceptions, and peer relations: A longitudinal study. Infant and Child Development, 24, 175–188. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2012.659233

Brown, B. B., and Bakken, J. P. (2011). Parenting and peer relationships: reinvigorating research on family–peer linkages in adolescence. J.Res. Adolesc. 21, 153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00720.x

Cameron, L., Erkal, N., Gangadharan, L., and Meng, X. (2013). Little emperors: behavioral impacts of China's one-child policy. Science 339, 953–957. doi: 10.1126/science.1230221

Chan, J. Y., Harlow, A. J., Kinsey, R., Gerstein, L. H., and Fung, A. L. C. (2018). The examination of authoritarian parenting styles, specific forms of peer-victimization, and reactive aggression in Hong Kong youth. School. Psychol. Int. 39, 378–399. doi: 10.1177/0143034318777781

Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Dev. 65, 1111–1119. doi: 10.2307/1131308

Chao, R. K. (2001). Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Dev. 72, 1832–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00381

Chen, X. (2012). Culture, peer interaction, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. Perspec. 6, 27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00187.x

Chen, X., Cen, G., Li, D., and He, Y. (2005). Social functioning and adjustment in Chinese children: The imprint of historical time. Child development, 76, 182–195.

Chen, Y., Wang, X., Fu, D., and Li, D. (2014). Is more exporting really better? A re-estimation based on generalised propensity score matching. J. Financ. Econ. 5, 100–111. doi: 10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.2014.05.010

Climent-Galarza, S., Alcaide, M., Garcia, O. F., Chen, F., and Garcia, F. (2022). Parental socialization, delinquency during adolescence and adjustment in adolescents and adult children. Behav. Sci. 12, 1–21. doi: 10.3390/bs12110448

Darling, N., and Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 113, 487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

Darling, N., and Steinberg, L. (2017). “Parenting style as context: an integrative model” in Interpersonal development. ed. R. Zukauskiene (London: Routledge), 477–487.

Deater-Deckard, K., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., and Pettit, G. S. (1996). Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 32, 1065–1072. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.1065

Delvecchio, E., Germani, A., Raspa, V., Lis, A., and Mazzeschi, C. (2020). Parenting styles and child’s well-being: the mediating role of the perceived parental stress. Eur. J. Psychol. 16, 514–531. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v16i3.2013

Dornbusch, S. M., Ritter, P. L., Leiderman, P. H., Roberts, D. F., and Fraleigh, M. J. (2016). “The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance” in Cognitive and moral development, academic achievement in adolescence. eds. R. M. Lerner and J. Jovanovic (New York: Routledge), 276–289.

Eagly, A. H. (2009). The his and hers of prosocial behavior: an examination of the social psychology of gender. Am. Psychol. 64, 644–658. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.64.8.644

Eagly, A. H. (2013). Sex differences in social behavior: a social-role interpretation. London: Psychol. Press

Elenbaas, L. (2019). Perceptions of economic inequality are related to children’s judgments about access to opportunities. Developmental Psychology, 55, 471.

Garcia, F., Serra, E., Garcia, O. F., Martinez, I., and Cruise, E. (2019). A third emerging stage for the current digital society? Optimal parenting styles in Spain, the United States, Germany, and Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132333

Gong, D., and Liu, B., (2004). Teaching children how to interact with their peers. Studies in Early Childhood Education, 4:11–12. [In Chinese]

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., and Hooven, C. (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: theoretical models and preliminary data. J. Fam. Psychol. 10, 243–268. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243

Green, V. A., Cillessen, A. H., Rechis, R., Patterson, M. M., and Hughes, J. M. (2008). Social problem solving and strategy use in young children. The Journal of genetic psychology, 169, 92–112.

Hao, K., (2012). An empirical study of the one-child group in China. Guangzhou: Guangdong Education Publishing House. 1–499

Hao, Y., and Feng, X., (2002). The influence of parent-child relationship on the growth of only children. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition), 6, 109–112. [In Chinese]

Hilt, L. M., McLaughlin, K. A., and Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2010). Examination of the response styles theory in a community sample of young adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 38, 545–556. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9384-3

Hosokawa, R., and Katsura, T. (2019). Role of parenting style in children’s behavioral problems through the transition from preschool to elementary school according to gender in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:21. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16010021

Howe, C., and Mercer, N. (2007). Children's social development, peer interaction and classroom learning. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Faculty of Education

Jahromi, L. B., Kirkman, K. S., Friedman, M. A., and Nunnally, A. D. (2021). Associations between emotional competence and prosocial behaviors with peers among children with autism spectrum disorder. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities, 126, 79–96.

Jespersen, J. E., Hardy, N. R., and Morris, A. S. (2021). Parent and peer emotion responsivity styles: an extension of Gottman’s emotion socialization parenting typologies. Child 8:319. doi: 10.3390/children8050319

Ladd, G. W., and Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2019). “Parents and children’s peer relationships” in Handbook of parenting. eds. G. W. Ladd and B. Kochenderfer-Ladd (London: Routledge), 278–315.

Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., and Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 62, 1049–1065. doi: 10.2307/1131151

Li, D., Zhang, W., Li, D., Wang, Y., and Zhen, S. (2012). The effects of parenting style and temperament on adolescent aggression: a test of unique, differential and mediating effects. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2, 211–225. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2012.00211

Li, Y., (2004). Social development of the child and its nurturing. Shanghai: East China Normal University Press. 10.

Liu, Q., and Feng, L. (2023). Parental marital quality and adolescent sibling relationships: the mediating role of parenting style and its gender differences. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 5, 1–9. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2023.05.06

Liu, Y., Wang, S., Yin, H., and Gu, C. (1988). A comparative study of only child and non-only child survey report. Popul. J. 3, 15–19. doi: 10.16405/j.cnki.1004-129x.1988.03.006

Luckner, A. E., and Pianta, R. C. (2011). Teacher–student interactions in fifth grade classrooms: relations with children's peer behavior. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 257–266. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12022

Luo, R., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., and Song, L. (2013). Chinese parents’ goals and practices in early childhood. Early Child. Res. Quart. 28, 843–857. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.08.001

Mak, M. C. K., Yin, L., Li, M., Cheung, R. Y. H., and Oon, P. T. (2020). The relation between parenting stress and child behavior problems: negative parenting styles as mediator. J. Child Fam. Stud. 29, 2993–3003. doi: 10.1007/s10826-020-01785-3

Martínez, I., Murgui, S., Garcia, O. F., and Garcia, F. (2021). Parenting and adolescent adjustment: the mediational role of family self-esteem. J. Child Fam. Stud. 30, 1184–1197. doi: 10.1007/s10826-021-01937-z

Mikami, A. Y., Lerner, M. D., Griggs, M. S., McGrath, A., and Calhoun, C. D. (2010). Parental influence on children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: II. Results of a pilot intervention training parents as friendship coaches for children. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 38, 737–749. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9393-2

Ng, F. F. Y., Pomerantz, E. M., and Deng, C. (2014). Why are Chinese mothers more controlling than American mothers? “My child is my report card”. Child development, 85, 355–369.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 100, 569–582. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569

Obimakinde, A. M., Omigbodun, O., Adejumo, O., and Adedokun, B. (2019). Parenting styles and socio-demographic dynamics associated with mental health of in-school adolescents in Ibadan, south-West Nigeria. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 31, 109–124. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2019.1662426

Palacios, I., Garcia, O. F., Alcaide, M., and Garcia, F. (2022). Positive parenting style and positive health beyond the authoritative: self, universalism values and protection against emotional vulnerability from Spanish adolescents and adult children. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1066282

Pang, H., Ye, L., and Yan, J., (1997). On the way teachers influence children’s social development. Studies in Early Childhood Education, 2:34–38. [In Chinese]

Pan, Y., and Shang, Z. (2023). Linking culture and family travel behaviour from generativity theory perspective: a case of Confucian culture and Chinese family travel behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 54, 212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.12.014

Perren, S., and Diebold, T. (2017). Soziale Kompetenzen sind bedeutsam für gelingende Peerbeziehungen und Wohlbefinden in der Kindertagesstätte. Frühe Kindheit 2, 30–38.

Perren, S., Forrester-Knauss, C., and Alsaker, F. D. (2012). Self-and other-oriented social skills: differential associations with children’s mental health and bullying roles. J. Educ. Res. Online 4, 99–123. doi: 10.25656/01:7053

Pinquart, M., and Kauser, R. (2018). Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 24, 75–100. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000149

Qin, L. (2022). Influence of family environment on peer interaction skills of 4- and 6-year-old children. Advance Educ. 12:2008.

Qin, L., and Caizhen, Y. (2022). The relationship between peer interactions and social withdrawal in young children. Advance Soc. Sci. 11:356.

Ren, L., Boise, C., and Cheung, R. Y. (2022). Consistent routines matter: child routines mediated the association between interparental functioning and school readiness. Early Child. Res. Quart. 61, 145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.07.002

Reyes, M., Garcia, O. F., Perez-Gramaje, A. F., Serra, E., Melendez, J. C., Alcaide, M., et al. (2023). Which is the optimum parenting for adolescents with low vs. high self-efficacy? Self-concept, psychological maladjustment and academic performance of adolescents in the Spanish context. An. De. Psicol. 39, 446–457. doi: 10.6018/analesps.517741

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., and Hart, C. H. (2001). “The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ)” in Handbook of family measurement techniques, vol. 3. eds. J. Touliatos, B. F. Perlmutter, and M. A. Straus (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 319–321.

Ros, R., and Graziano, P. A. (2018). Social functioning in children with or at risk for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 47, 213–235. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1266644

Saara, R. R. (1951). “Social behavior and personality development” in Toward a general theory of action (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 465–478.

Sahithya, B. R., Manohari, S. M., and Vijaya, R. (2019). Parenting styles and its impact on children–a cross cultural review with a focus on India. Ment. Health. Relig. Cult. 22, 357–383. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2019.1594178

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. J. Res. Adolesc. 11, 1–19. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00001

Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Darling, N., Mounts, N. S., and Dornbusch, S. M. (1994). Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 65, 754–770. doi: 10.2307/1131416

Steinberg, L., and Morris, A. S. (2001). Adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

Sümer, N., Pauknerova, D., Vancea, M., and Manuoğlu, E. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of work values in Czech Republic, Spain, and Turkey: Parent-child similarity and the moderating role of parenting behaviors. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 682, 86–105.

Tian, J. (2019). An examination of the reform of China's pre-school education curriculum over the past 40 years of reform and opening up. Educ. Sci. Res. 5, 60–65.

Tippett, N., and Wolke, D. (2015). Aggression between siblings: associations with the home environment and peer bullying. Aggress. Behav. 41, 14–24. doi: 10.1002/ab.21557

Van der Graaff, J., Carlo, G., Crocetti, E., Koot, H. M., and Branje, S. (2018). Prosocial behavior in adolescence: Gender differences in development and links with empathy. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47, 1086–1099.

Villarejo, S., Garcia, O. F., Alcaide, M., Villarreal, M. E., and Garcia, F. (2023). Early family experiences, drug use and psychosocial adjustment across the life span: is parental strictness always a protective factor? Psychosoc. Interv. doi: 10.5093/pi2023a16

Wang, M. T., Degol, J. L., and Henry, D. A. (2019). An integrative development-in-sociocultural-context model for children’s engagement in learning. Am. Psychol. 74, 1086–1102. doi: 10.1037/amp0000522

Wang, S., and Gai, X., (2020). Rule internalisation in 3-7 years old children: the interaction of parenting behaviours with children’s gender and temperament. Studies in Early Childhood Education, 2, 68–78. [In Chinese]

Wang, X., and Zhuang, Y. (2012). Developmental characteristics of peer interaction skills of migrant children aged 3-6 years old. Studies in Early Childhood Education, 9, 29–34. [In Chinese]

Wei, H., Fan, C., Zhou, Z., Tian, Y., and Qi, Y., (2011). Relationships between relational aggression, friendship quality and loneliness in children of different genders. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19:681–683. [In Chinese]

Wu, Y., Guo, F., Wang, Y., Jiang, L., and Chen, Z., (2017). The relationship between parental marital quality and adolescents’ externalising problems: the mediating role of parenting styles. Psychological Development and Education, 3, 345–351. [In Chinese]

Xu, F., Guo, X., and Zhang, J. (2013). Characteristics and psychological theories of 3- to 4-year-old children\u0027s understanding of the concept of lie, and the role of parenting styles. Psychological Development and Education, 29:449–456. [In Chinese]

Xu, H., Zhang, J., and Zhang, M., (2008). A review of research on the impact of family parenting styles on children’s socialisation development. Journal of Psychological Science, 31:940–942. [In Chinese]

Zhang, Q., Huang, H., and Wang, C., (2022). The effect of affective perspective-taking ability on young children’s peer relationships - the mediating role of pro-social behaviour. Journal of Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University, 38:48–55. [In Chinese]

Zhang, Y. (2002). Development of the peer interaction skills scale for 4-6 years old. J. J. Sec. Nor. Univ. 1, 42–44.

Zheng, H., (2018). Research on the influence of 4-6-year-old children’s emotional comprehension on peer conflict resolution strategies (Master’s thesis, Henan University). [In Chinese]

Zhou, H., and Long, L. (2004). Statistical tests and control methods for common method bias. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 6, 942–950.

Zhou, L., Jiang, L., Zhang, X., Hu, J., and Zhang, H., (2014). An analysis of the mechanisms influencing self-concept on subjective well-being: the mediating role of self-efficacy and relationship harmony. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 12:107–114 135. [In Chinese]

Keywords: authoritarian parenting style, peer interactions, social development, gender heterogeneity, age heterogeneity, number heterogeneity

Citation: Li D, Li W and Zhu X (2024) The association between authoritarian parenting style and peer interactions among Chinese children aged 3–6: an analysis of heterogeneity effects. Front. Psychol. 14:1290911. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1290911

Received: 08 September 2023; Accepted: 12 December 2023;

Published: 08 January 2024.

Edited by:

Xiaoqin Zhu, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Oscar F. Garcia, University of Valencia, SpainCopyright © 2024 Li, Li and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xingchen Zhu, emh1eGluZ2NoZW5sbm51QDE2My5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.