- 1Department of Medical Informatics, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

- 4Department of General Courses, Population, Family and Spiritual Health Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran

- 5Pharmaceutical Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Background: The present study introduces informational and supportive needs and sources of obtaining information in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) through a three-round Expert Delphi Consensus Opinions method.

Methods: According to our previous scoping review, important items in the area of informational and supportive needs and sources of obtaining information were elucidated. After omitting duplicates, 56 items in informational needs, 36 items in supportive needs, and 36 items in sources of obtaining information were retrieved. Both open- and close-ended questions were designed for each category in the form of three questionnaires. The questionnaires were sent to selected experts from different specialties. Experts responded to the questions in the first round. Based on the feedback, questions were modified and sent back to the experts in the second round. This procedure was repeated up to the third round.

Results: In the first round, five items from informational needs, one item from supportive needs, and seven items from sources of obtaining information were identified as unimportant and omitted. Moreover, two extra items were proposed by the experts, which were added to the informational needs category. In the second round, seven, three, and seven items from informational needs, supportive needs, and sources of obtaining information were omitted due to the items being unimportant. In the third round, all the included items gained scores equal to or greater than the average and were identified as important. Kendall coordination coefficient W was calculated to be 0.344 for information needs, 0.330 for supportive needs, and 0.325 for sources of obtaining information, indicating a fair level of agreement between experts.

Conclusions: Out of 128 items in the first round, the omission of 30 items and the addition of two items generated a 100-item questionnaire for three sections of informational needs, supportive needs, and sources of obtaining information with a high level of convergence between experts' viewpoints.

1. Introduction

The increasing prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in developed and developing countries imposes a significant burden on healthcare systems (Calvet et al., 2014), which has led to an emerging global health concern (Molodecky et al., 2012). IBD mainly appears in two forms: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD). Chronic immune-mediated inflammatory gastrointestinal impairments are the underlying causes of multiple acute life-threatening complications, such as toxic megacolon, sepsis due to penetrating disorder, and thromboembolism (Carter et al., 2004). Although the exact etiology of IBD remains elusive, a complex interaction of genetic (Orholm et al., 1991) and environmental (Danese et al., 2004) factors is found to be responsible for the abnormal activation of the mucosal immune system (Baumgart and Carding, 2007). Both disorders are characterized by periods of remission and active intestinal inflammation, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain, that may even result in hospitalization (Langholz et al., 1994; Munkholm et al., 1995). Additionally, UC and CD increase the risk of colorectal cancer by up to 18% (Eaden et al., 2001). Associated primary sclerosing cholangitis may lead to cholangiocarcinoma. Accordingly, IBD patients are prone to high mortality, either directly or indirectly (Selinger et al., 2013). Because of the chronic nature of these disorders, their unpredictable disease course, their onset at young ages, and the high cost of medical and surgical treatments, they cause social isolation and mood disorders such as depression and anxiety (Sajadinejad et al., 2012; Moradkhani et al., 2013; Williet et al., 2014).

IBD is historically managed in a reactive and crisis-driven mode rather than proactive (Crohn's and Colitis Australia, 2013). Several models of care have been developed for IBD and can be used to overcome certain barriers to quality care. The WHO proposes an integrated approach to improve care quality and avoid disease complications (Jackson and De Cruz, 2019). It is patient-centered and involves patients in service developments; it includes an action plan for follow-up, contains education, incorporates a detailed evaluation of biopsychosocial functioning, and has a dedicated nurse for care coordination (Mikocka-Walus et al., 2012). This approach reduces the frequency of clinic visits, hospitalizations, and polypharmacy, which decreases healthcare costs (Mikocka-Walus et al., 2013).

However, such an integrated model of care is not accessible to all IBD patients, and only large tertiary centers can provide such multidisciplinary care. Another model of care for IBD patients is participatory care, in which patients play a role in the management of the disease. A collaboration is formed between the patient and the physician, while the patient is responsible for driving the healthcare system. Various electronic health tools (Eysenbach and CONSORT-EHEALTH Group, 2011), including web-based platforms, smartphone applications, telemedicine, and decision-support instruments, facilitate the implementation of this model of care. The participatory model promotes patient engagement, augments monitoring of the disease condition, and makes easy earlier intervention (Jackson et al., 2016). Value-based healthcare has recently emerged as a model of care that aims to improve quality in healthcare. It evaluates health outcomes and associated costs at the disease level (van Deen et al., 2015). This model is ultimately designed to overcome hurdles related to care costs (van Deen et al., 2017).

In recent years, the focus of disease management has been on patients rather than their disease. Patients with enhanced knowledge show a higher quality of life and are eager to obtain more information about their disease (Bernstein et al., 2011). Hence, elevating the perception of patients about IBD and its treatment options through care optimization by improving the information provided and augmenting education increased the quality of life and reduced depression and anxiety (Elkjaer et al., 2008). However, educating patients alone is not enough, and self-care strategies also improve disease symptoms, psychological wellbeing, and the use of healthcare resources (Barlow et al., 2010). A study showed that patients who had been trained in self-management care demonstrated higher confidence, had more ability to deal with their condition, experienced fewer hospitalizations, and maintained their quality of life at an appropriate level (Kennedy et al., 2004).

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) uses the best-known findings from current clinical care research diligently and wisely to integrate clinical expertise and manage individual patients (Hohmann et al., 2018). Although EBM is an outstanding approach, it has not yet been sufficiently developed for certain topics with a lack of evidence or uncertainty (Powell, 2003; Keeney et al., 2006). In such circumstances, a consensus opinion of experts is a suitable alternative. One of the available methods in this regard is the Delphi method. In this study, a panel of experts was established without any face-to-face data exchange. Data were collected by distributing sequential questionnaires in at least two rounds. Experts were informed about the feedback from each round in an anonymous way, and finally, an opinion systematically emerged (Hohmann et al., 2018). The advantages of the Delphi method are anonymity, controlled feedback, and statistical group responses (Dalkey and Helmer, 1963; Dalkey, 1969).

Data regarding indices of supportive needs, information needs, and sources of obtaining information for IBD patients are scarce. It is important to elucidate such indices from the perspective of experts, who are routinely involved in the management of these patients. Moreover, the level of knowledge of IBD patients in developing countries such as Iran is significantly lower compared with their peers in developed regions. This then leads to undesirable consequences such as late diagnosis (Rezailashkajani et al., 2006). Owing to the importance of self-empowerment in patients with IBD and identifying informational and supportive needs and sources of obtaining information, the present study was designed to fill this gap via a Delphi consensus study.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and registration protocol

A Delphi consensus study was designed to identify informational and supportive needs and sources of information for patients with IBD. This research was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUMS.REC.1400.230).

2.2. Motivations for the choice of the Delphi methodology

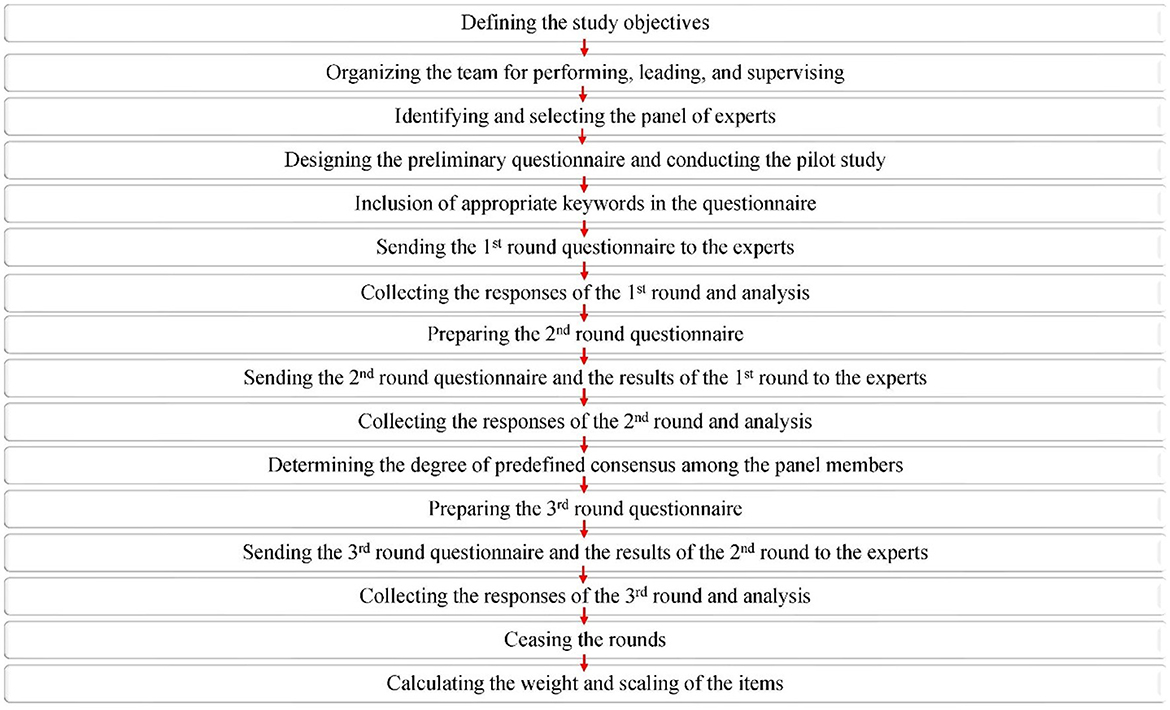

Based on a scoping review, the current Delphi study is the second phase of investigations in the era of self-care aspects in patients with IBD (Norouzkhani et al., 2023). In the scoping review, important parameters such as informative, psychological, and supportive elements for IBD patients were extracted from the literature and reported. Owing to the various opinions on disease diagnosis and management, formal group consensus methods can deliver objective and subjective judgments. In addition, formal group consensus methods include a wide range of knowledge and experience, interaction between members, and stimulating constructive debate. Therefore, the scientific research committee team identified parameters that need to be evaluated, scrutinized, ranked, and weighted specifically by experts. In this way, upcoming investigations, such as those of interventional procedures, are feasible based on expert-filtered data. To summarize, because the findings of the scoping review are the prerequisite for conducting the next phase, Delphi consensus is the option of choice to integrate diverse viewpoints from experts in the field. The main steps of the Delphi approach are illustrated in Figure 1.

2.3. Research questions

The current study aims to seek answers to the following questions:

What is the experts' opinion on the informational needs of patients with IBD?

What is the experts' opinion on the supportive needs of patients with IBD?

What is the experts' opinion on sources for obtaining information on patients with IBD?

2.4. Identification and selection of experts

A steering committee consisting of experts in the field of IBD was identified and selected. They were responsible for performing, leading, and supervising all the research steps. These experts were in well known national specialists in the field of IBD. This team also defined certain criteria, primarily based on the regulations of the European Food Safety Authority (Authority, 2014), for selecting experts who were responsible for responding to the questionnaires. These inclusion criteria were years/type of experience, vocational qualifications, related references, publications, awards, conference presentations, academic qualifications, and teaching experiences. Other criteria, such as expressing judgments and experiences of risk assessment, were also considered. A steering committee first assessed the feasibility of the types of specialty for responding to the questionnaires and then attempted to identify them. Main national experts in the field of IBD were mapped according to the existing databases/literature/knowledge or those with the most relevant publications in this area through Internet searches. Even those with opposing views were invited. At this point, their CVs were requested if they were not found in the public database. Those experts who did not respond to the questionnaires after 14 days were excluded from the study. All the invited experts were asked to sign a form informing them about the study's subject and objectives, its duration, and approximate round numbers to show their agreement to participate.

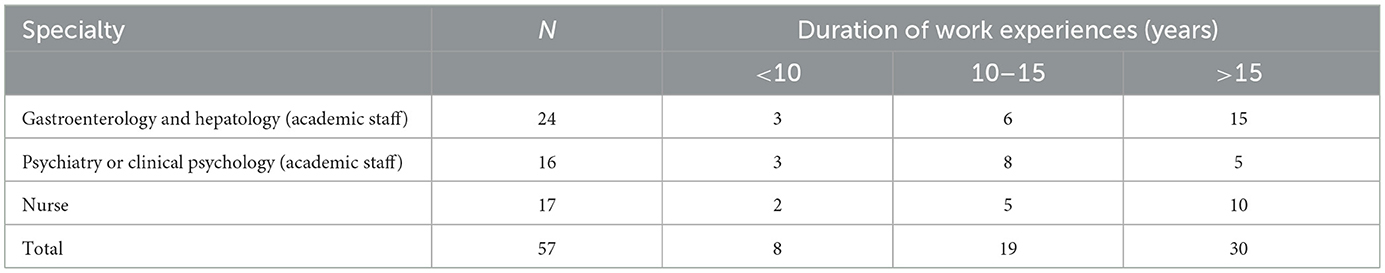

In the current study, two sampling methods were used to establish the panel of experts. Initially, purposive sampling was utilized to select the first line of experts based on defined criteria. Then, snowball sampling was used to accelerate the process of finding experts and increase the number of panel members. First-line experts were asked to introduce other experts in accordance with the defined criteria. This method of selecting panel members was used because the researchers' committee had no precise information about their expertise, which significantly affected the study's outcome. Furthermore, because experts in a specific field usually knew each other well in the context of a scientific community, more experts were found in a shorter period of time. Indeed, experts communicate with each other more easily based on previous familiarity, and hence, they accept participation and membership in the panel more readily compared with invitations from the researchers' committee. The average age of the experts was 44.89 ± 6.44 years, and 56.14% of them (n = 32) were men. All of them were academics in universities and research institutes and were gastroenterologists (n = 24, 42.11%), psychologists/psychiatrists (n = 16, 28.07%), or nurses (n = 17, 29.82%). The total years of experience of the experts in the field of IBD were 15.49 ± 5.58 years. Table 1 depicts the number of panel members, their field of specialty, and the duration of their work experiences.

2.5. Design of the preliminary questionnaire and implementation of the pilot study

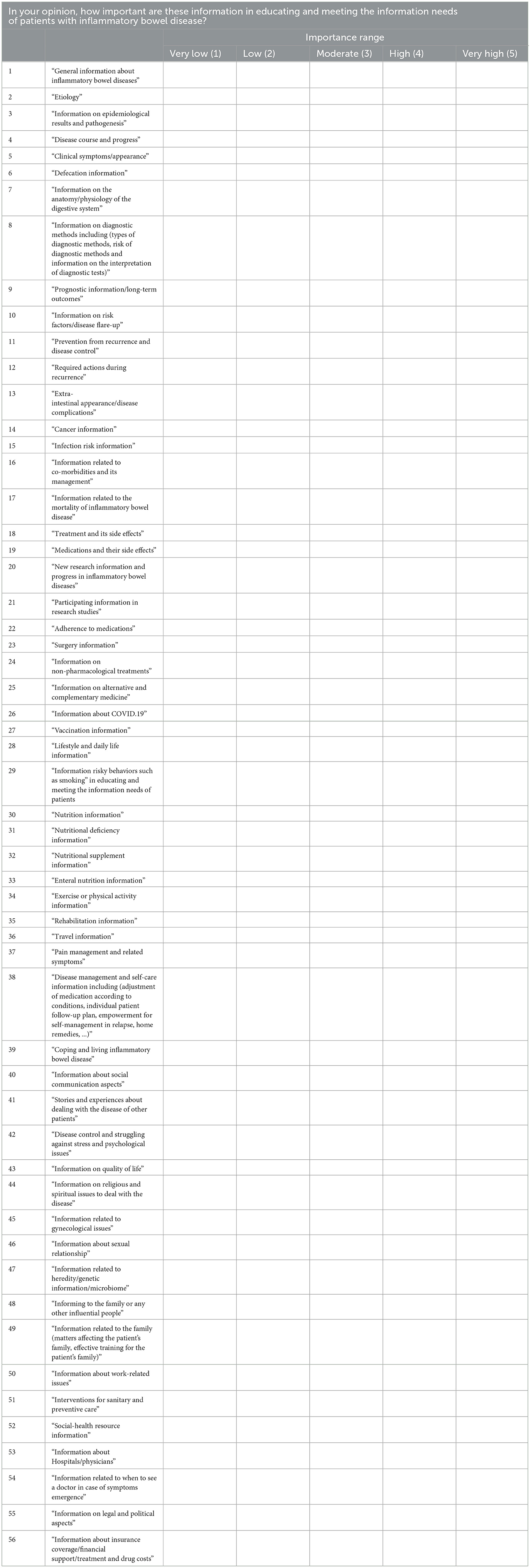

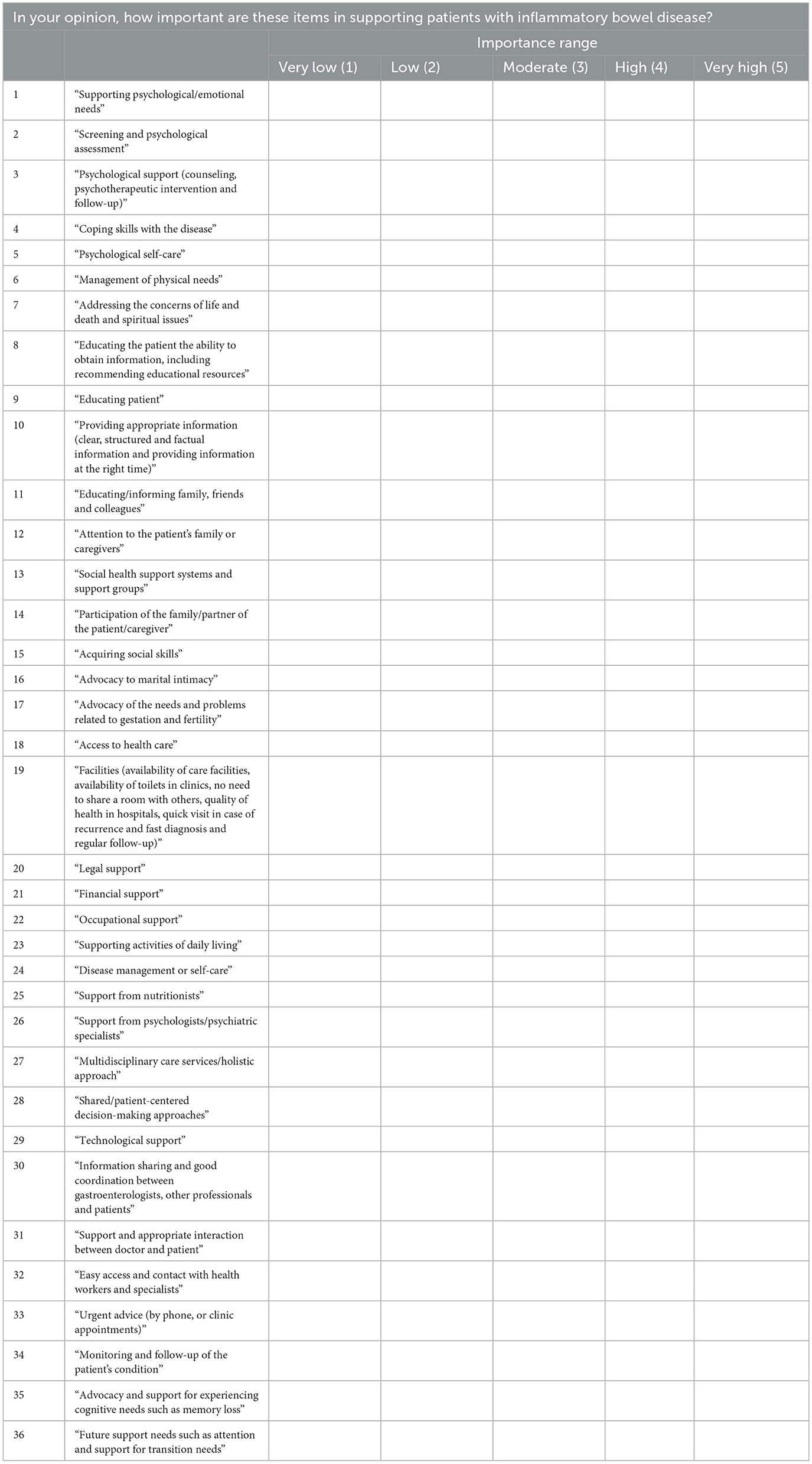

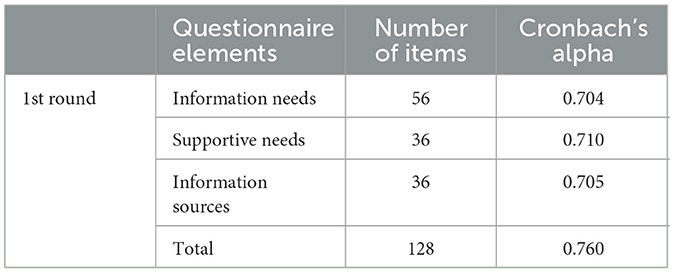

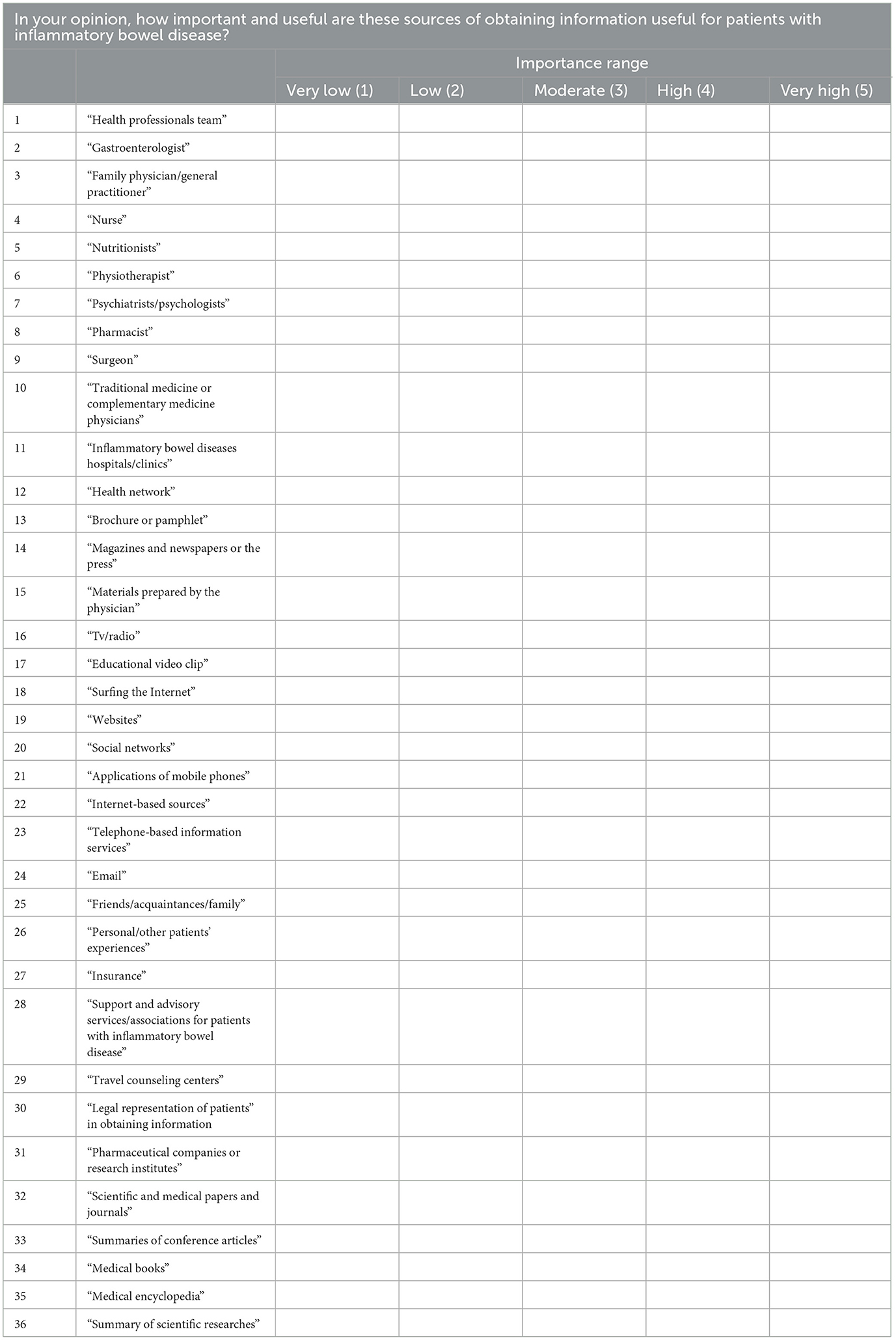

Our scoping review (Norouzkhani et al., 2023) identified important items in the informational needs, supportive needs, and sources of obtaining information. After omitting duplicates, 56 items in information needs, 36 items in supportive needs, and 36 items in sources of obtaining information were identified. Based on the retrieved items, specific questions were designed for each section, ultimately leading to a questionnaire with both open- and close-ended questions. The questionnaire was sent to four experts to find any possible pitfalls and misunderstandings within the questions. These experts were selected from three different provinces (Tehran, Khorasan Razavi, and Mazandaran). They discussed all the questions in the preliminary questionnaire and decided to replace some of them with more understandable questions with more suitable keywords if necessary. The experts proved the validity of the questionnaire and its content validity upon reaching a common understanding of the questions in line with the subject of the study. To check the reliability, Cronbach's alpha was calculated. Moreover, a test-retest examination was conducted for the questionnaires of the first and second rounds. As indicated in Tables 2–4, a 5-point Likert scale was defined, including one score for very low, two scores for low, three scores for moderate, four scores for high, and five scores for very high importance. In each section, the mean score was calculated for every question based on the received scores from all the experts, and this mean was considered for assigning the item to the low (<3) or high importance (≥3) category. If the question gained a high score, which means high importance, it was included in the next round of the questionnaire. Otherwise, it was omitted.

Table 4. First round questions of information sources and methods needs of patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Experts who participated had no direct interaction with each other, and data were exchanged via an Internet-based platform without physical contact. Generally, in this method, experts were asked to send their responses and any possible comments on consecutive questionnaires according to the cumulative feedback from the previous round. The feedback helped the experts to reevaluate, modify, or expand the comments (Windle, 2004). The promising advantage of such an approach is that it ensures anonymity for the participants. Such anonymity ensures that no specific expert would have a dominant effect on others' opinions (Dalkey, 1969; Landeta, 2006), allowing all individuals to have the same opportunity to express their own opinions. This way, it facilitates the free expression of ideas and helps acquire sufficient insight and knowledge in the field (Walker and Selfe, 1996; Turoff and Linstone, 2002; Ali, 2005).

A web-based platform was used for sending the first round of questionnaires. An analysis of the responses collected from the first round formed the basis for the preparation of the second round questionnaire. Based on the results from the first round, five questions out of 56 in the information needs section, one out of 36 in the supportive needs section, and seven out of 36 in the information sources section had scores lower than the mean. Hence, these questions were regarded as having low importance and omitted from the questionnaire. Moreover, experts agreed to add one item (fasting) to the information needs section and another one (acquiring psychological skills) to the supportive needs section. They believed that these two are effective in recognizing information and supportive needs in IBD patients. The second round of questionnaires and the results of the first round were sent to the experts via the web-based platform. The experts were informed in detail about the changes. Experts' comments were collected in the second round and combined to provide scoring for each question. Based on the findings extracted from the second round, a third round of questionnaires was designed. Seven questions out of 52 in the information needs section, three out of 36 in the supportive needs section, and seven out of 29 in the information sources section were found to have scored lower (<3) than the mean. These questions were regarded as having low importance and omitted from the questionnaire. At this step, no further items were proposed for adding to the questionnaire. After sending the new questionnaire to the experts and collecting their comments, they were subjected to analysis.

2.6. Ceasing the rounds

After the third round, analysis of the responses showed that the scores for all the questions were higher than the mean. The experts proposed no new statements at this stage. Furthermore, the results of all three rounds of this Delphi approach showed that experts' consensus had been reached for the following reasons: (1) No statement was omitted or added in the third round, (2) given that the number of respondents was more than 10 individuals and the Kendall coefficients were 0.330, 0.344, and 0.325 in three sections at the third round, a completely meaningful condition was deduced, and (3) there was a slight difference between the second and third rounds without significant growth in the Kendall coefficient.

2.7. Calculation of the weight and scales of the items

After finalizing the identification of important items in three sections, the weight and scale of each item were determined based on the scores assigned by the experts at the end of round three.

3. Results

In the present study, various important items were identified in the areas of informational needs, supportive needs, and sources of obtaining information using the Delphi consensus for patients with IBD and were presented from the viewpoints of experts using the consensus. Based on previous findings (Norouzkhani et al., 2023), a preliminary questionnaire was designed (Tables 2–4). In a scoping review, we previously identified informational needs, information resource, and supportive needs, as well as psychological needs, of IBD patients based on the Daudt methodological framework (Norouzkhani et al., 2023). After defining the research questions according to the four sections mentioned, all types of studies that were conducted in patients with IBD and ≥18 years of age were considered without any restrictions in the language or settings. A single consensus strategy based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria was defined, and electronic databases were extensively searched from January 2000 to April 2022. After omitting duplicates and screening the titles, the abstracts of the remaining papers were separately scrutinized by two independent experts. To ensure the similarity of the decisions made by these two experts on the inclusion and exclusion of the papers, 10% of them were checked by a third expert. At the next stage, full texts were assessed, and any disagreements were resolved by a third party. According to the guidelines for conducting the scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2015), there was no need to appraise the methodological quality or risk of bias in the included papers.

The resulting questionnaires were delivered to 79 other experts in the first round, and only 57 of them answered. There was a non-normal distribution among the collected parameters. As shown in Table 5, the Cronbach alpha was calculated at 0.760, which shows the reliability of the questionnaire. A total of 13 questions out of 128 were omitted from the questionnaire due to their low importance based on the scores. In terms of informational needs, items that were omitted were “participating information in research studies,” “rehabilitation information,” “information about social communication aspects,” “social-health resource information,” and “information on legal and political aspects.” Only the item “advocacy and support for experiencing cognitive needs such as memory loss” was omitted from the supportive needs section.

Regarding the information sources section, “physiotherapist,” “health network,” “email,” “friends/acquaintances/family,” “travel counseling centers,” “legal representation of patients in obtaining information,” and “medical encyclopedia” were removed. Meanwhile, two further items (fasting and acquiring psychological skills) were added to the questionnaire. After analyzing the responses from the first round, the Kendall rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the degree of convergence. The Kendall coefficient of 0.354 for information needs, 0.252 for supportive needs, and 0.353 for sources of obtaining information showed ~35%, 25%, and 35% convergence between the experts' viewpoints, respectively.

The number of questions was decreased to 117 by making the required changes. Analyzing the results of the second round of the questionnaire revealed that 17 questions indicated low importance based on their scores. The lack of any further items to be added to the questionnaire indicated that the current version had covered all aspects of the study objectives. In the second round, the Kendall coefficient was 0.343 for information needs, 0.310 for supportive needs, and 0.363 for sources of obtaining information, showing ~34%, 31%, and 36% convergence between the experts' viewpoints, respectively. Although the Kendall coefficient was meaningful at this stage, this does not provide sufficient evidence to cease the Delphi approach in the second round because there were still some questions of low importance in the second questionnaire, and therefore, the experts had not reached a consensus.

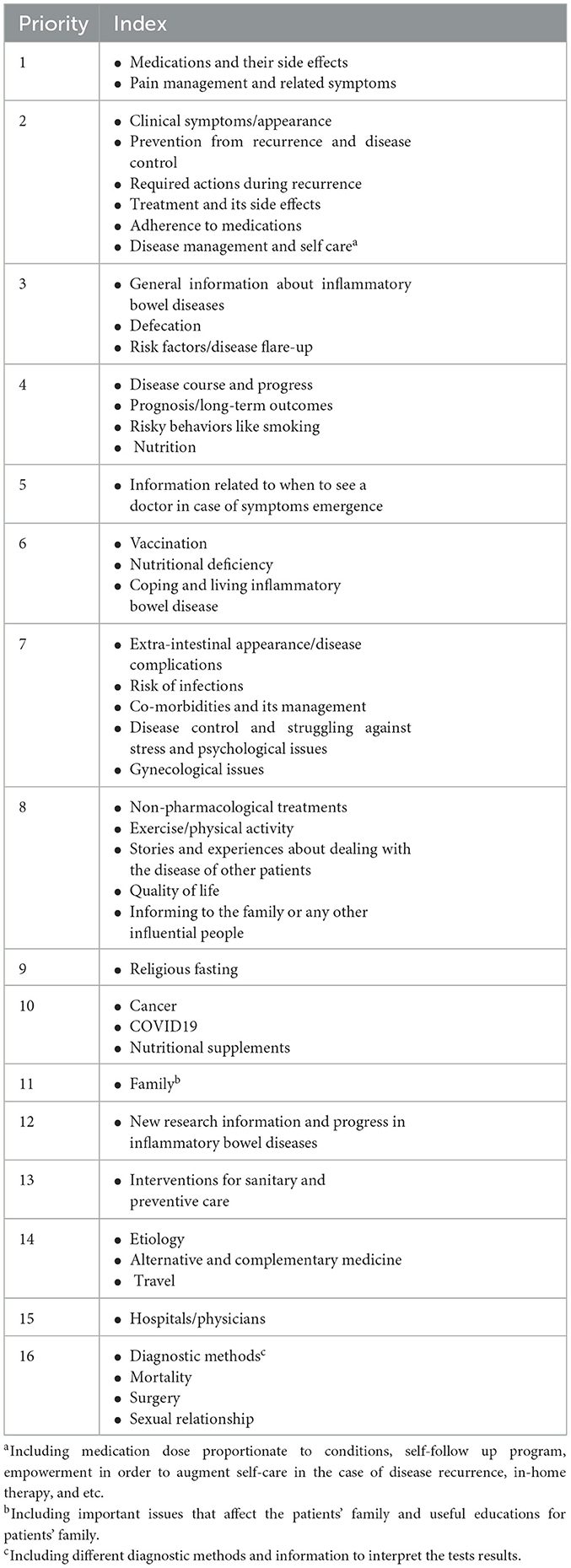

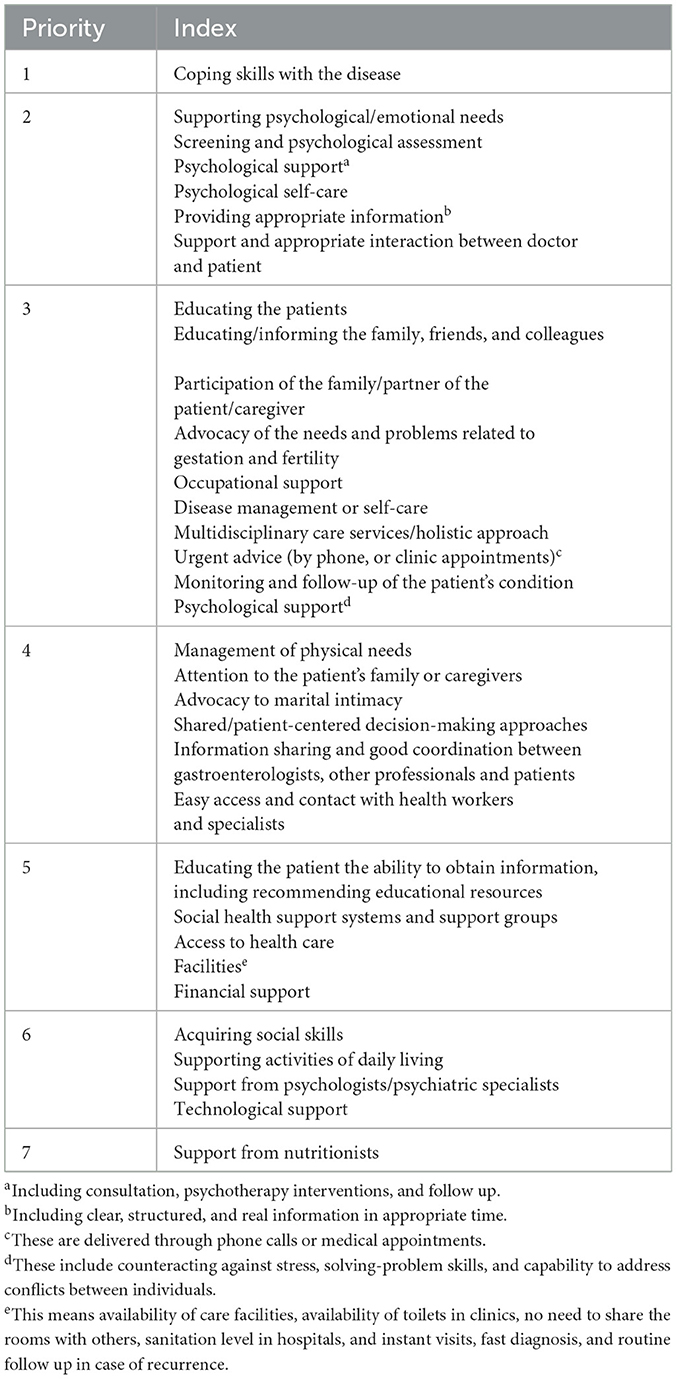

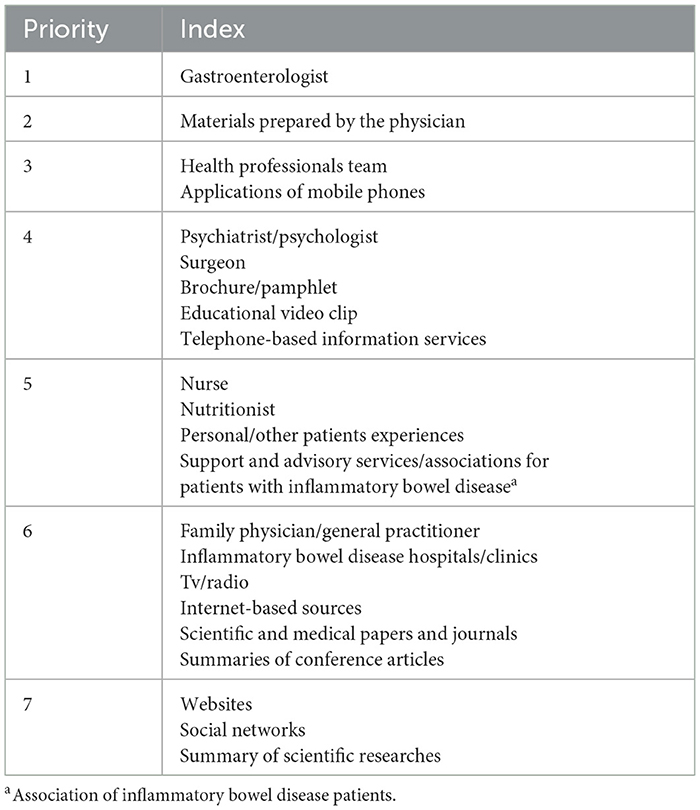

Omitting 17 indices of low importance produced a questionnaire with 100 questions. All the questions in the third round had a score equal to or greater than the mean. It was deduced that all the remaining items were of high importance. The Kendall coefficient was calculated to be 0.344 for information needs, 0.330 for supportive needs, and 0.325 for sources of obtaining information, meaning that there was ~34%, 33%, and 32% convergence between the experts' viewpoints, respectively. Similarly, in the second round, no other items were proposed by the experts, indicating that the current ones had encompassed all aspects of the study. The criteria for ceasing the rounds were provided, as there were no omissions or additions for any other items, and the difference in the Kendall coefficients between the second and the third rounds was not significant. Finalized items are provided in Tables 6–8 based on their weight and scaling.

Table 6. Approved items in information needs section after three rounds of Delphi consensus presenting in the order of weight and scaling.

Table 7. Approved items in supportive needs section after three rounds of Delphi consensus presenting in the order of weight and scaling.

Table 8. Approved items in information sources and methods section after three rounds of Delphi consensus presenting in the order of weight and scaling.

4. Discussion

The main aim of the present study was to provide a comprehensive set of important items in the management of IBD in three sections: information needs, supportive needs, and sources of obtaining information for patients with IBD based on the experts in the field. These three sections constitute critical indices that patients with IBD need to control and manage the disease. Moreover, this study not only precisely discriminated important items from other ones but also allowed the classification of the important items via a rating system. In other words, this makes the differentiation of the most and least remarkable items among important items feasible. In our study, a 128-item questionnaire in the first round was optimized into a questionnaire with 100 items after three rounds of the Delphi consensus. The findings of this study were derived from the combined viewpoints of major stakeholders in the field of IBD, including gastroenterologists, psychiatrists/psychologists, and nurses, through a Delphi consensus approach. A convergence of 32–34% among experts' viewpoints was reached at the end of the process, indicating an efficient consensus process.

Identifying the needs of IBD patients in precise categories is beneficial for patients, physicians, and other healthcare professionals. Such information enables patients to manage the disease, alleviate relevant anxiety and worries, and improve their compliance. Otherwise, screening for some negative consequences of IBD, such as colorectal cancer, is underestimated by patients. Moreover, patients feel they have control over medical decisions, which causes a positive relationship with their physicians and healthcare professionals, which in turn makes patients feel less alienated. Moreover, this awareness reduces the upcoming complications that affect the three parties in terms of overcoming the barriers in formal and informal support, increasing the support intake from different resources, and directing the delivery of information to the patients in a more conducive and systematic manner.

Owing to internal (lack of control over bowel movements) and external stressors (access to restrooms), patients with IBD require specific supportive needs, which multi-professional teams should develop. One study identified instrumental support (disease-related information) and emotional support (discussing disease management). To support IBD patients, various strategies (behavioral, social, and emotional) were adopted to cope with disease conditions (Larsson et al., 2017). In our study, experts believe that “disease compatibility skills” would be of the highest priority regarding supportive needs.

There is a paucity of information regarding IBD among patients. Intriguingly, it was reported that patients with different profiles of demographic characteristics and clinical parameters have unique and clinically relevant information needs (Daher et al., 2019). Insufficient efforts in delivering specific domains of information to IBD patients may impede the identification of symptoms required for disease diagnosis. Indeed, information is a valuable element, and it can be regarded as a potentially important component that improves IBD outcomes (Pittet et al., 2016). However, most IBD patients believe that they did not receive important information about the disease in the first 2 months after diagnosis (Bernstein et al., 2011). Notably, disease duration affects the patients' knowledge. Those who are recently diagnosed may need different types of information compared with those with chronic illnesses (Bernstein et al., 2011).

IBD patients need information to manage the disease in their daily routine. This was referred to as “knowledge needs” in one study (Lesnovska et al., 2014) and was classified into three groups: those related to the disease course, those related to managing everyday life, and those difficult to understand and assimilate. This type of need has great variation, especially at the time of diagnosis and during relapse. “Medications and their side effects” and “pain management and related symptoms” were identified as the most important items in the information needs section of the present study. In one study on IBD patients from Greece, the main complaint was the lack of information about treatment. The study revealed that certain hurdles in some aspects of their lives, such as health-related social life, emotional status, and work productivity, were significantly affected (Viazis et al., 2013). Treatment (medical and surgical), clinical appearance, cancer, and mortality risks are the types of additional information needed by the patients (Catalán-Serra et al., 2015).

With respect to the sources of obtaining information, “gastroenterologists” were known as the major sources in our study. Another study reported that gastroenterologists, besides the Internet, were the most frequent sources of information 2 months after diagnosis. However, it was shown that only 45% of patients were very satisfied with the information they received at the time of diagnosis (Bernstein et al., 2011). In third place, general practitioners were known as sources for obtaining information another study. Once more, only about half of the patients claimed that the gastroenterologists covered their information needs. Furthermore, it should be noted that the Internet was useful for young patients and those with a high level of literacy (Catalán-Serra et al., 2015).

Both the mental and physical health of IBD patients are impaired, according to the findings from one study, which showed that general health perceptions were below the critical value in 40% of patients. This demonstrates the importance and divergence of needs among IBD patients (Casellas et al., 2020). In a survey to identify the needs of young adults with IBD, psychological needs and daily living needs were presented as the most and least common ones (Cho et al., 2018). Because the burden of psychological distress was found to be concerning in such patients, point-of-care screening and interventions should be considered initially in the context of biopsychological care (Moon et al., 2020).

Clinical conditions of IBD patients, such as laboratory findings, activity parameters, and endoscopic examinations, traditionally form the basis of daily practice and care plans, such as the type of medications, frequency of visits, and referral to another specialist (Sainsbury and Heatley, 2005; Sajadinejad et al., 2012; Moradkhani et al., 2013; Williet et al., 2014). Although quality of life is improved by such an objective evaluation of the disease, some subjective aspects based on patients' characteristics such as personality, expectations, family framework, and social issues are also determined (Casellas et al., 2020). Nowadays, holistic and personalized medicine have become novel features in therapeutic approaches that alter the model of care for chronic diseases like IBD (Kennedy and Rogers, 2002; Baars et al., 2010). In line with this, the empowerment of the patients, their involvement in disease management, and incorporating their opinions into clinical decisions seem vital (O'Connor et al., 2013; Rettke et al., 2013). Implementing these approaches improves quality of life and creates satisfaction in patients regarding the kind of care and treatment they receive (Barlow et al., 2010; O'Connor et al., 2014). In a scoping review, the nature and extent of the research evidence were published for IBD patients across three life cycles. Scrutinizing the main needs of children, adolescents, and adults showed the value of the involvement of the patient and healthcare providers through supporting and promoting engagement. Moreover, such interventions were advised to be organized from a multidisciplinary perspective (Volpato et al., 2021).

Empowerment of IBD patients significantly contributes to rehabilitation programs and helps them handle the long-term consequences of the disease and manage their health status more efficiently by obtaining better outcomes (Small et al., 2013). Empowerment, as a complicated experience of personal modifications in life values and priorities, is classified at individual, organizational, and community levels (Aujoulat et al., 2007). In one study, the key aspects of empowerment in IBD patients were reported to be social interaction skills and disease-specific health literacy (Zare et al., 2020). Interactions with others in the form of communicating with optimistic people, establishing family and friendly entertainment plans, and having relations with peers improve the mental status of patients and are considered an efficient approach for controlling psychological situations that trigger IBD flare-ups. The ability to ask for support is another aspect of such interactions, which can be substantiated by asking physicians to speak to the relatives of the patients for support, meet coworkers/bosses about the disease, and demand reliable information in web-based tools from valid sources (Zare et al., 2020).

The Internet is not only a learning source for IBD patients but also a substrate for communication. Patients who use the Internet are young, more educated, and sicker (Angelucci et al., 2009). While the Internet delivers a considerable amount of information to IBD patients (Cima et al., 2007), it affects the relationship between patients and the physicians. It should be noted that information derived from the Internet is usually unregulated and unfiltered, and this may lead to confusion and mislead people into making poor choices. Some Internet-based applications, or social media applications, allow for exchanging ideas and facilitate interpersonal interaction (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010), eventually resulting in patient empowerment (Flisher, 2010). In addition, some applications are designed for use on smartphones and mobile tablets and help patients with symptom tracking and self-management. Some other applications are equipped to print or email reports to the physicians. However, some limitations, such as a lack of clarity in the qualifications of the providers, production of design and develop disease management products without consultation with IBD care providers, and the absence of validated measures of disease severity, restrain their use (Fortinsky et al., 2012).

To meet a wide range of needs that are considered important by patients, providing reliable applications would be an outstanding help. Although patients can access huge amounts of data through the Internet, social media, and support groups, they prefer to receive information about their disease mainly from physicians. However, transferring all the required information from physicians to patients through traditional verbal communication appears to be impractical. To overcome this barrier, written information, such as brochures or websites with user-friendly interfaces, is an appropriate alternative that supplements physician–patient consultations and provides a higher level of detailed information (Bernstein et al., 2011).

Reaching a high level of agreement is one of the strengths of the present study. This shows the validity of the consensus process that was obtained from the opinions of health experts from different fields. The inclusion of patients' preferences in a multidisciplinary way is necessary for clinical care.

4.1. Limitations

The findings of this study may not be generalizable to all IBD patients due to differences in the characteristics of IBD patients (prevalence and severity of the disease). All the invited experts were from the same country, and their opinions may differ from those of their peers in other regions. Furthermore, it is logistically impossible to gather all the experts in the field from different specialties. Distribution of experts with sufficient skill and expertise in managing IBD patients are not homogenous between regions and countries. Patients are not homogenous between regions and countries. Health infrastructures and facilities, such as centers specifically organized to support IBD patients in terms of medications and other needs, are not equally available between high- and middle-income countries. The comprehensive nature of care in chronic diseases such as IBD requires different healthcare providers, such as nutritionists, gynecologists, radiologists, general practitioners, stoma therapists, rheumatologists, physician assistants, pharmacists, and immunologists, to be involved in delivering diverse information to patients. For instance, mucosal immunologists, who are among the most important experts with critical roles in the differential diagnosis of various forms of IBD (CD and UC), were not present in our study. All these factors, in our opinion, may limit the generalizability of the findings of the current study.

5. Conclusion

The present study identified 100 items across three categories: supportive needs, sources of obtaining information, and the specific informational needs of IBD patients, as identified by experts using a Delphi-based methodology. Properly educating IBD patients based on verified needs can result in decreased stress levels, improved treatment adherence, and enhanced disease control and management. Although we believe that these questionnaires are useful for national patients in delivering certain information and meeting some needs, future studies should be conducted with the inclusion of a broader range of experts from both basic and clinical specialties and with the participation of different centers from different regions and countries to identify specific and more generalizable needs for IBD patients.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUMS.REC. 1400.230). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NN and HT conceived the original idea. NN carried out the experiment and wrote the manuscript with support from HT and MF. AB, MF, and JS carried out the experiment and aided in interpreting the results. SE and AB helped supervise the project. HT supervised the project. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the experts who worked on this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali, A. K. (2005). Using the Delphi technique to search for empirical measures of local planning agency power. Qual. Rep. 10, 718–744. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2005.1829

Angelucci, E., Orlando, A., Ardizzone, S., Guidi, L., Sorrentino, D., Fries, W., et al. (2009). Internet use among inflammatory bowel disease patients: an Italian multicenter survey. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 1036–1041. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328321b112

Aujoulat, I., d'Hoore, W., and Deccache, A. (2007). Patient empowerment in theory and practice: polysemy or cacophony? Patient Educ. Couns. 66, 13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.008

Authority, E. F. S. (2014). Guidance on expert knowledge elicitation in food and feed safety risk assessment. EFSA J. 12, 3734. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3734

Baars, J. E., Markus, T., Kuipers, E. J., and Van Der Woude, C. J. (2010). Patients' preferences regarding shared decision-making in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: results from a patient-empowerment study. Digestion 81, 113–119. doi: 10.1159/000253862

Barlow, C., Cooke, D., Mulligan, K., Beck, E., and Newman, S. A. (2010). critical review of self-management and educational interventions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 33, 11–18. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0b013e3181ca03cc

Baumgart, D. C., and Carding, S. R. (2007). Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet 369, 1627–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60750-8

Bernstein, K. I., Promislow, S., Carr, R., Rawsthorne, P., Walker, J. R., Bernstein, C. N., et al. (2011). Information needs and preferences of recently diagnosed patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 17, 590–598. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21363

Calvet, X., Panés, P. J., Alfaro, N., Hinojosa, J., Sicilia, B., Gallego, M., et al. (2014). Delphi consensus statement: quality indicators for inflammatory bowel disease comprehensive care units. J. Crohns. Colitis 8, 240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.10.010

Carter, M. J., Lobo, A. J., and Travis, S. P. (2004). Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 53, v1–v16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.043372

Casellas, F., Guinard Vicens, D., García-López, S., González-Lama, Y., Argüelles-Arias, F., Barreiro-de Acosta, M., et al. (2020). Consensus document on the management preferences of patients with ulcerative colitis: points to consider and recommendations. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 32, 1514–1522. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001885

Catalán-Serra, I., Huguet-Malavés, J. M., Mínguez, M., Torrella, E., Paredes, J. M., Vázquez, N., et al. (2015). Information resources used by patients with inflammatory bowel disease: satisfaction, expectations and information gaps. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 38, 355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2014.09.003

Cho, R., Wickert, N. M., Klassen, A. F., Tsangaris, E., Marshall, J. K., Brill, H., et al. (2018). Identifying needs in young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 41, 19–28. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000288

Cima, R. R., Anderson, K. J., Larson, D. W., Dozois, E. J., Hassan, I., Sandborn, W. J., et al. (2007). Internet use by patients in an inflammatory bowel disease specialty clinic. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.13, 1266–1270. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20198

Daher, S., Khoury, T., Benson, A., Walker, J. R., Hammerman, O., Kedem, R., et al. (2019). Inflammatory bowel disease patient profiles are related to specific information needs: a nationwide survey. World J. Gastroenterol. 25, 4246. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i30.4246

Dalkey, N. (1969). An experimental study of group opinion: the Delphi method. Futures 1, 408–426. doi: 10.1016/S0016-3287(69)80025-X

Dalkey, N., and Helmer, O. (1963). An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage. Sci. 9, 458–467. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458

Danese, S., Sans, M., and Fiocchi, C. (2004). Inflammatory bowel disease: the role of environmental factors. Autoimmun. Rev. 3, 394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.03.002

Eaden, J., Abrams, K., and Mayberry, J. (2001). The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut 48, 526–535. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.526

Elkjaer, M., Moser, G., Reinisch, W., Durovicova, D., Lukas, M., Vucelic, B., et al. (2008). IBD patients need in health quality of care ECCO consensus. J. Crohns. Colitis 2, 181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2008.02.001

Eysenbach, G., and CONSORT-EHEALTH Group (2011). CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 13, e1923. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1923

Flisher, C. J. (2010). Getting plugged in: an overview of internet addiction. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 46, 557–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01879.x

Fortinsky, K. J., Fournier, M. R., and Benchimol, E. (2012). Internet and electronic resources for inflammatory bowel disease: a primer for providers and patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18, 1156–1163. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22834

Hohmann, E., Cote, M. P., and Brand, J. C. (2018). Research pearls: expert consensus based evidence using the Delphi method. Arthroscopy 34, 3278–3282. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.10.004

Jackson, B. D., and De Cruz, P. (2019). Quality of care in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25, 479–489. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy276

Jackson, B. D., Gray, K., Knowles, S. R., and De Cruz, P. (2016). EHealth technologies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J. Crohns. Colitis 10, 1103–1121. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw059

Kaplan, A. M., and Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 53, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Keeney, S., Hasson, F., and McKenna, H. (2006). Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J. Adv. Nurs. 53, 205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03716.x

Kennedy, A., Nelson, E., Reeves, D., Richardson, G., Roberts, C., Robinson, A., et al. (2004). A randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness and cost of a patient orientated self management approach to chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 53, 1639–1645. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034256

Kennedy, A. P., and Rogers, A. E. (2002). Improving patient involvement in chronic disease management: the views of patients, GPs and specialists on a guidebook for ulcerative colitis. Patient Educ. Couns. 47, 257–263. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00228-2

Landeta, J. (2006). Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 73, 467–482. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2005.09.002

Langholz, E., Munkholm, P., Davidsen, M., and Binder, V. (1994). Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology 107, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90054-X

Larsson, K., Lööf, L., and Nordin, K. J. (2017). Stress, coping and support needs of patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease: a qualitative descriptive study. J. Clin. Nurs. 26, 648–657. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13581

Lesnovska, K. P., Börjeson, S., Hjortswang, H., and Frisman, G. H. (2014). What do patients need to know? Living with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 23, 1718–1725. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12321

Mikocka-Walus, A., Andrews, J. M., von Känel, R., and Moser, G. (2013). An improved model of care for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). J. Crohns. Colitis 7, e120–e121. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.08.004

Mikocka-Walus, A. A., Turnbull, D., Holtmann, G., and Andrews, J. M. (2012). An integrated model of care for inflammatory bowel disease sufferers in Australia: development and the effects of its implementation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18, 1573–1581. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22850

Molodecky, N. A., Soon, S., Rabi, D. M., Ghali, W. A., Ferris, M., Chernoff, G., et al. (2012). Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 142, 46–54. e42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001

Moon, J. R., Lee, C. K., Hong, S. N., Im, J. P., Ye, B. D., Cha, J. M., et al. (2020). Unmet psychosocial needs of patients with newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis: results from the nationwide prospective cohort study in Korea. Gut Liver 14, 459. doi: 10.5009/gnl19107

Moradkhani, A., Beckman, L. J., and Tabibian, J. H. (2013). Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: psychosocial, clinical, socioeconomic, and demographic predictors. J. Crohns. Colitis 7, 467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.07.012

Munkholm, P., Langholz, E., Davidsen, M., and Binder, V. (1995). Disease activity courses in a regional cohort of Crohn's disease patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 30, 699–706. doi: 10.3109/00365529509096316

Norouzkhani, N., Faramarzi, M., Shokri Shirvani, J., Bahari, A., Eslami, S., Tabesh, H. J., et al. (2023). Identification of the informational and supportive needs of patients diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease: a scoping review. Front. Psycholl. 14, 1718. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1055449

O'Connor, M., Bager, P., Duncan, J., Gaarenstroom, J., Younge, L., Détré, P., et al. (2013). N-ECCO Consensus statements on the European nursing roles in caring for patients with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns. Colitis 7, 744–764. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.06.004

O'Connor, M., Gaarenstroom, J., Kemp, K., Bager, P., and Woude, J. C. (2014). N-ECCO survey results of nursing practice in caring for patients with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis in Europe. J. Crohns. Colitis 8, 1300–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.012

Orholm, M., Munkholm, P., Langholz, E., Nielsen, O. H., Sørensen, T. I., Binder, V. J., et al. (1991). Familial occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 324, 84–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101103240203

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., Soares, C. B., et al. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 13, 141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Pittet, V., Vaucher, C., Maillard, M. H., Girardin, M., de Saussure, P., Burnand, B., et al. (2016). Information needs and concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: what can we learn from participants in a bilingual clinical cohort? PLoS ONE 11, e0150620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150620

Powell, C. (2003). The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J. Adv. Nurs. 41, 376–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x

Rettke, H., Staudacher, D., Schmid-Büchi, S., Habermann, I., Spirig, R., Rogler, G. J. P., et al. (2013). Inflammatory bowel diseases: experiencing illness, therapy and care. Pflege 26, 109–118. doi: 10.1024/1012-5302/a000275

Rezailashkajani, M., Roshandel, D., Ansari, S., and Zali, M. R. (2006). Knowledge of disease and health information needs of the patients with inflammatory bowel disease in a developing country. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 21, 433–440. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0030-4

Sainsbury, A., and Heatley, R. (2005). therapeutics. Psychosocial factors in the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 21, 499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02380.x

Sajadinejad, M. S., Asgari, K., Molavi, H., Kalantari, M., and Adibi, P. (2012). Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2012, 106502. doi: 10.1155/2012/106502

Selinger, C. P., Andrews, J., Dent, O. F., Norton, I., Jones, B., McDonald, C., et al. (2013). Cause-specific mortality and 30-year relative survival of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 19, 1880–1888. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31829080a8

Small, N., Bower, P., Chew-Graham, C. A., Whalley, D., and Protheroe, J. (2013). Patient empowerment in long-term conditions: development and preliminary testing of a new measure. BMC Health Serv. Res. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-263

Turoff, M., and Linstone, H. A. (2002). The Delphi method-techniques and applications. J. Mark. Res. 18. doi: 10.2307/3150755

van Deen, W. K., Esrailian, E., and Hommes, D. W. (2015). Value-based health care for inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Crohns. Colitis 9, 421–427. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv036

van Deen, W. K., Spiro, A., Burak Ozbay, A., Skup, M., Centeno, A., Duran, N. E., et al. (2017). The impact of value-based healthcare for inflammatory bowel diseases on healthcare utilization: a pilot study. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 29, 331–337. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000782

Viazis, N., Mantzaris, G., Karmiris, K., Polymeros, D., Kouklakis, G., Maris, T., et al. (2013). Inflammatory bowel disease: greek patients' perspective on quality of life, information on the disease, work productivity and family support. Ann. Gastroenterol. 26, 52. doi: 10.1016/S1873-9946(12)60126-3

Volpato, E., Bosio, C., Previtali, E., Leone, S., Armuzzi, A., Pagnini, F., et al. (2021). The evolution of IBD perceived engagement and care needs across the life-cycle: a scoping review. BMC Gastroenterol. 21, 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01850-1

Walker, A., and Selfe, J. (1996). The Delphi method: a useful tool for the allied health researcher. Br. J. Ther. Rehabil. 3, 677–681. doi: 10.12968/bjtr.1996.3.12.14731

Williet, N., Sandborn, W. J., and Peyrin–Biroulet, L. (2014). Patient-reported outcomes as primary end points in clinical trials of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 1246–1256. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.016

Windle, P. E. (2004). Delphi technique: assessing component needs. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 19, 46–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2003.11.005

Keywords: inflammatory bowel diseases, needs assessment, informational need, information seeking behavior, consumer health information, supportive needs, psychosocial need, Delphi technique

Citation: Norouzkhani N, Bahari A, Shirvani JS, Faramarzi M, Eslami S and Tabesh H (2023) Expert opinions on informational and supportive needs and sources of obtaining information in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a Delphi consensus study. Front. Psychol. 14:1224279. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1224279

Received: 17 May 2023; Accepted: 23 August 2023;

Published: 21 September 2023.

Edited by:

Rubén González-Rodríguez, University of Vigo, SpainReviewed by:

Danijela Petrovic, University of Novi Sad, SerbiaColm Antoine O. Morain, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

Andrea-René Angeramo, European University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Norouzkhani, Bahari, Shirvani, Faramarzi, Eslami and Tabesh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hamed Tabesh, dGFiZXNoaGFtZWRAeWFob28uY29t; dGFiZXNoNzlAZ21haWwuY29t; dGFiZXNoaEBtdW1zLmFjLmly

Narges Norouzkhani

Narges Norouzkhani Ali Bahari2

Ali Bahari2 Hamed Tabesh

Hamed Tabesh