- 1Escuela de Psicología y Filosofía, Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica, Chile

- 2Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Tarapacá, Arica, Chile

With the massification of the Internet and social networks, a new form of dating violence called cyber-violence has emerged, which involves behaviors of control, humiliation, intimidation and threats towards the partner or ex-partner. Using a non-probabilistic sample of 1,001 participants aged 18 to 25 years, the present study used an ex post facto, retrospective, cross-sectional, single-group design to analyze the joint effects that beliefs associated with dating violence such as romantic love myths, jealousy, and sexism have on the victimization and perpetration of cyber-violence. The results evidenced that jealousy is involved in both Cyber-victimization and Cyber-harassment perpetrated, while sexist beliefs are only involved in perpetration. In the discussion section, it is postulated that cyber-violence is a phenomenon that is more related to the probability of aggression, but not to the probability of being a victim. Finally, limitations and implications for future research are discussed.

1. Introduction

Dating violence (DV), as it is referred to in Anglo-Saxon literature, refers to any aggressive behavior, harassment, or intentional attack, towards a partner or ex-partner, either physically, sexually, or psychologically, occurring in a romantic relationship involving young people or adolescents [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020], who do not have, nor have had, legal ties, economic dependence, or situations of mutual cohabitation (Vizcarra et al., 2013; Pazos Gómez et al., 2014; Rubio-Garay et al., 2017).

Early studies focusing interest on violence in these age groups date back to the mid-1980s (e.g., Makepeace, 1981; O’Keeffe et al., 1986), although they have become more relevant in the last two decades (Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017), being recognized as a severe public health problem (Valdivia Peralta and González Bravo, 2014), considering its notorious impacts on the physical and mental health of young people (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013), and its high prevalence (López-Barranco et al., 2022).

The emergence and massification of the Internet and social networks has revealed that dating violence can be exercised both in person and through digital media [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020], resulting in a new form of dating violence, called cyber-violence in relationships or online dating violence, which refers to violent behaviors towards the partner or ex-partner through the use of new information and communication technologies (ICTs), such as the Internet, cell phones and social networks (Guadix et al., 2018) and is characterized by including behaviors of control, humiliation, intimidation, and threat (Cava et al., 2020a,b), such as, for example, checking the cell phone, sharing photos, videos, and information of the partner without consent, threatening exposure of content on social networks, limiting the content that their partner uploads to the Internet, exerting control over the partner to monitor their social relationships, knowing where they are and what they are doing, among others (Rodríguez et al., 2021). These behaviors impact the psychosocial well-being of young people (Cava and Buelga, 2018; Cava et al., 2020a,b), leading several adverse consequences in the short and long term (Pérez-Marco et al., 2020; Tomaszewska and Schuster, 2021).

Young people and adolescents may be involved as victims of cyber-violence in their romantic relationships, i.e., being subjected to virtual control or abuse by their partner or ex-partner or perpetrating such violent behaviors (Marcos et al., 2020). However, it is typical for this type of situation to occur with a bidirectional character, where they can be, at the same time, victims or aggressors (López-Barranco et al., 2022). Therefore, when evaluating cyber-violence, it is relevant to analyze it from both roles, which may allow identifying common or differential factors in the levels of cyber-violence exercised and received.

Numerous studies have been developed in recent decades focused on identifying cyber-violence behaviors (e.g., Zweig et al., 2013), their prevalence (Peskin et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2018), and the consequences of such actions (Shorey et al., 2012; Borrajo and Gamez-Guadix, 2016; Hancock et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2018). However, given the grueling consequences for the physical and mental health of young people and adolescents, in recent years, and with a focus on prevention, interest has centered on identifying those factors that increase or decrease the likelihood of being a victim or perpetrator of cyber-violence (Vizoso-Gómez and Fernández-Gutiérrez, 2022).

Many young couples and adolescents are unable to recognize violent behaviors and confuse them as demonstrations of romantic love (Pérez-Marco et al., 2020), normalizing the use of cyber-violence as a strategy to resolve their conflicts (Vizoso-Gómez and Fernández-Gutiérrez, 2022). Conflict is a constitutive aspect of any relationship, but it can trigger diverse and intense negative emotions (Chapman and Gillespie, 2019). Negative emotions have been identified as a central precedent of a violent response, evidenced as the main reason young people and adolescents explain aggression in their relationships (Pazos Gómez et al., 2014). Conflicts can have diverse origins; however, given that in youth and adolescent relationships, economic or domestic commitments are not frequently present (Garzón González et al., 2017), the primary source of conflict is associated with jealousy (Alegría del Ángel and Rodríguez Barraza, 2015), which, at the same time, are also considered as a direct motivation to exercise dating violence (Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., 2018).

Jealousy occurs in response to the perception of threat, real or imagined, of loss or damage of a significant relationship (Branson and March, 2021), as a consequence of the involvement of a third person, which translates into a negative emotional response marked by anger, sadness, and fear, among others (Bosch et al., 2008). Although jealousy is commonly identified as a pathological response that should be avoided, multiple cultural beliefs act as a justification and reinforcer of jealousy, being typical for it to be normalized, supported by beliefs such as the myths of romantic love (Yela, 2000), and gender role (i. e. sexism; Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., 2018), approaches that could contribute to young people normalizing certain types of behaviors and even perceiving them as an expression of love (Malonda et al., 2017; Garrido and Barceló, 2019).

Romantic myths are a set of commonly shared socially beliefs about the how “real love” and meaningful romantic relations must be, in words of Yela (2003), “the supposed true nature of love.” As happens with other myths, they are usually fictitious, absurd, misleading, irrational, and impossible to fulfill (Yela, 2003; Bosch et al., 2008). Myths about romantic love have been recognized as a factor that contributes to fostering and maintaining violence in relationships (Garrido, 2001; González Méndez and Santana Hernández, 2001; Sanmartín et al., 2003; Lagarde, 2005; Sanpedro, 2005; Bosch et al., 2008; Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero, 2018; Del Castillo, 2018; Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero, 2021; Ariza Ruiz et al., 2022), as they reinforce violent love models by promoting the idea that true love should be possessive and exclusive (Yela, 2003; Pequeño et al., 2019).

Sexism is a multidimensional construct, referring to sexist beliefs and attitudes that limit gender roles and expression by sex, usually associated with discrimination against women (Glick and Fiske, 1996; Fernández-Montalvo and Echeburúa, 1997; Arnoso et al., 2017). During the last decades, sexist beliefs have been considered a relevant vulnerability factor for the perpetration and victimization of violence (León-Ramírez and Ferrando Piera, 2014; Ibabe et al., 2016; Marcos et al., 2020), being considered as one of the main background in the justification and promotion of dating violence (Orozco Vargas et al., 2022), as it that sexism can contribute to power inequality in the relationship and to the reinforcement of stereotypical gender roles (Glick and Fiske, 2001), which are also present in cyber-violence, where online harassment and abuse can be motivated by misogyny and sexism. Some research in the young and adolescent population indicates that men, and women with more traditional beliefs of sexism, are more accepting of the use of aggression in couple relationships and aggression towards women (Ulloa et al., 2004), data that confirm the existence of sociocultural factors that influence and reinforce sexist models and gender differences (Soler et al., 2005; Pazos Gómez et al., 2014).

In summary, jealousy, romantic love myths, and sexism are interrelated components that would constitute a belief system that would favor the emergence of negative emotions and legitimize violent manifestations (Cava and Buelga, 2018), including those that are expressed virtually, even though the evidence confirming these relationships is robust, most available studies present restrictions to understanding the joint role of these variables and establishing their relative importance since they are restricted to a few variables (e.g., De Los Reyes et al., 2022). In addition to the methodological restrictions of the use of univariate models and the lack of multivariate approximations, and the one that is of most significant interest for the present study, most of the available studies have focused on manifestations of face-to-face violence, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the new dynamics of romantic relationships, which have a robust virtual component.

In this scenario, it seems relevant to have evidence that establishes the combined effects of various beliefs associated with dating violence on cyber-violence in relationships to contribute to developing and prioritizing preventive actions from psychology and promoting healthy relationships. Therefore, the present study contrasts an explanatory model of online dating violence for cyber victimization and Cyber-harassment perpetrated from a latent variable model that includes romantic love myths, sexism, and jealousy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

This research corresponds to a non-experimental, ex post facto, retrospective, cross-sectional, single-group, correlational study with non-probabilistic sampling via social networks.

2.2. Participants

The initial sample consisted of 1,360 young people; however, to safeguard the existence of a dating experience, it was decided to exclude those who stated that they had not been in any romantic relationship in the last 12 months.

The final sample consisted of 1,001 participants between 18 and 25 years of age, with a mean age of 21.01 years (SD = 2.093), of whom 86% (n = 861) were female and 13.4% (n = 134) were male. In relation to the sexual orientation of the participants, 82.8% identified themselves as heterosexual, followed by 11.6% Bisexual, 2.6% Pansexual and 1.8% Homosexual. In turn, 63.8% stated that they were in an exclusive relationship (single partner), while 26.3% were single without occasional partners. The occupation of most of the participants was higher education students (77.5%), 8% were workers and 8.6% engaged in both activities.

The participants of this research were invited through social networks. The invitation was disseminated publicly and specified the inclusion criteria: (1) being between 18 and 25 years old and (2) permanent residence in a region of Chile. Data was collected by convenience sampling method during the years 2021–2022.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Cyber-violence scale in adolescent couples (Cib-VPA)

Developed by Cava and Buelga (2018). This instrument is an adaptation of the scale, the original version of which is composed of 20 4-point Likert-type attitudinal/behavioral statements (1 = never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = quite often; 4 = always), intended to assess two dimensions: Cyber-harassment perpetrated, including items related to aggressive and controlling behaviors perpetrated against the partner through social networks; and Cyber-victimization, describing the same aggressive and controlling behaviors, but, in this case, assessing the extent to which adolescents have suffered such behaviors in their romantic relationship. The reliability estimates reported by Cava and Buelga (2018) are satisfactory for each dimension (ω ≥ 0.80). Additionally, the scale has been adapted and validated for use in Chilean youth (Ramírez-Carrasco et al., 2023b).

2.3.2. Ambivalent sexism inventory

A 6-point, 22-item Likert-type bifactor scale designed to assess two dimensions: hostile sexism and benevolent sexism. The scale has a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.84 and has been adapted and validated for use with university students in northern Chile (Cárdenas et al., 2010).

2.3.3. Myths of romantic love scale (E-MAR)

Developed by Ramírez-Carrasco et al. (2023a). Self-report scale composed of 40 items of 4-point Likert-type behavioral/attitudinal statements (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, agree, strongly agree), intended to evaluate 8 dimensions: 1) myth of the better half (5 items); 2) myth of pairing (5 items); 3) exclusivity and fidelity myth (5 items); 4) jealousy myth (7 items); 5) omnipotence myth (4 items); 6) free will myth (4 items); 7) myth marriage (6 items); and 8) myth eternal passion (4 items). The scale presented a suitable fit [CFI = 0.969, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.047(0.045–0.050)].

2.3.4. Multidimensional scale of jealousy in dating

Self-developed scale (Supplementary material), whose final version is composed of 20 items of 4-point Likert-type behavioral/attitudinal statements (1 = never; 2 = sometimes; 3 = quite often; 4 = always), designed to evaluate 4 dimensions: 1) affective jealousy related to deception (6 items); 2) affective jealousy related to abandonment (3 items); 3) cognitive jealousy (6 items); 4) behavioral jealousy (5 items). This scale has evidence of validity based on internal structure [CFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.980, RMSEA = 0.038(0.032–0.043)]. However, the behavioral jealousy dimension was excluded from the present study, given that there is a very close correspondence of the items with the dependent variable since 3 allude to online control strategies.

2.4. Procedure

The present study and the data collection instruments were assessed and approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of the Universidad de Tarapacá, following the ethical Helsinki guidelines according to the World Medical Association for research with human beings.

The application of the scale was carried out in a general population of young Chileans (N = 1,360). The instrument was administered online together with other scales in the framework of a more extensive study, with the objective of developing an integrative-comprehensive model of dating violence in young couples and adolescents. The model included variables, such as, cyber-violence, self-esteem, jealousy, romantic love myths, sexism, emotional regulation and risk behaviors. As well as the informed consent, where the participant declared whether they accepted to participate voluntarily in the research, in which the objectives of the research, the rights of the participants, commitment to anonymity, confidentiality and use of the information for the ole purposes of the research were informed.

2.5. Statistical analysis

First, an exploratory structural equation analysis (ESEM) with GEOMIN rotation (Asparouhov and Muthén, 2009) was performed for the multidimensional models to assess the adequacy of the measurement models to the study sample, and the weighted least squares robust least squares estimation method (WLSMV), which has evidenced to function adequately with non-normal discrete variables and has a suitable performance for ordinal variables such as those of the instruments used to assess the constructs of interest (Suh, 2015). Confirmatory factor analyzes (CFA) and the weighted least squares robust weighted least squares estimation method (WLSMV) were performed for unidimensional models. From these analyzes, an ad-hoc adjustment was made to the ambivalent sexism inventory, eliminating 3 items that presented relevant cross-loadings (>0.3) or minor factorial saturations (<0.4), which produced a relevant misfit of the measurement model.

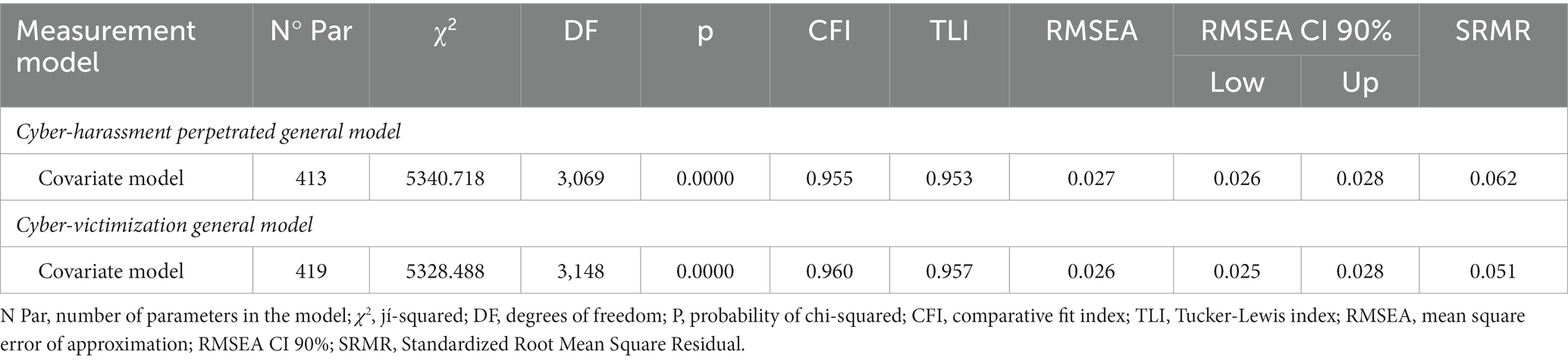

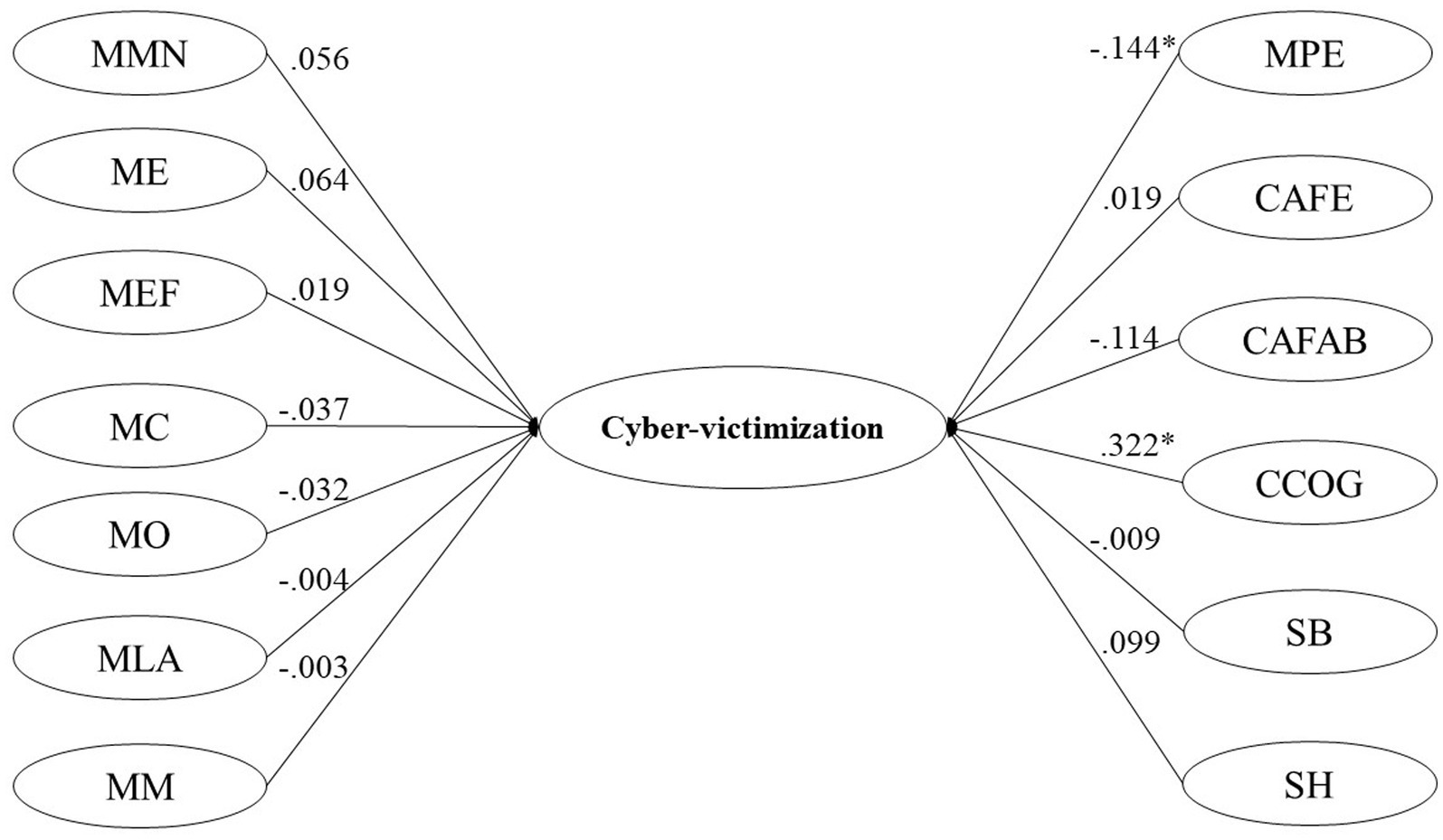

Finally, using the weighted least squares robust least squares estimation method (WLSMV), 2 structural equation models were performed, one for Cyber-victimization and the other for Cyber-harassment perpetrated (see Figures 1, 2), using as independent variables the subdimensions of the measurement instruments: Ambivalent Sexism Inventory, Myths of Romantic Love Scale, and Jealousy Scale. The overall model fit was assessed following the cut-point recommendation (e.g., CFI > 0.95; TLI > 0.95; RMSEA<0.06) proposed by Schreiber (2017).

Figure 1. Cyber-victimization general model. MMN, myth of the better half; ME, mith of pairing; MEF, exclusivity and fidelity myth; MC, jealousy myth; MO, omnipotence myth; MLA, free will myth; MM, myth marriage; MPE, myth eternal passion; CAFE, affective jealousy related to deception; CAFAB, affective jealousy related to abandonment; CCOG, cognitive jealousy; SB, benevolent sexism; SH, hostile sexism. The coefficients are standardized.

Figure 2. Cyber-harassment perpetrated General Model. MMN, myth of the better half; ME, mith of pairing; MEF, exclusivity and fidelity myth; MC, jealousy myth; MO, omnipotence myth; MLA, free will myth; MM, myth marriage; MPE, myth eternal passion; CAFE, affective jealousy related to deception; CAFAB, affective jealousy related to abandonment; CCOG, cognitive jealousy; SB, benevolent sexism; SH, hostile sexism. The coefficients are standardized.

All the analyzes were carried out from the polychoric correlation matrices, which are suitable for treating ordinal variables (Barendse et al., 2015), using Mplus software version 8.2.

3. Results

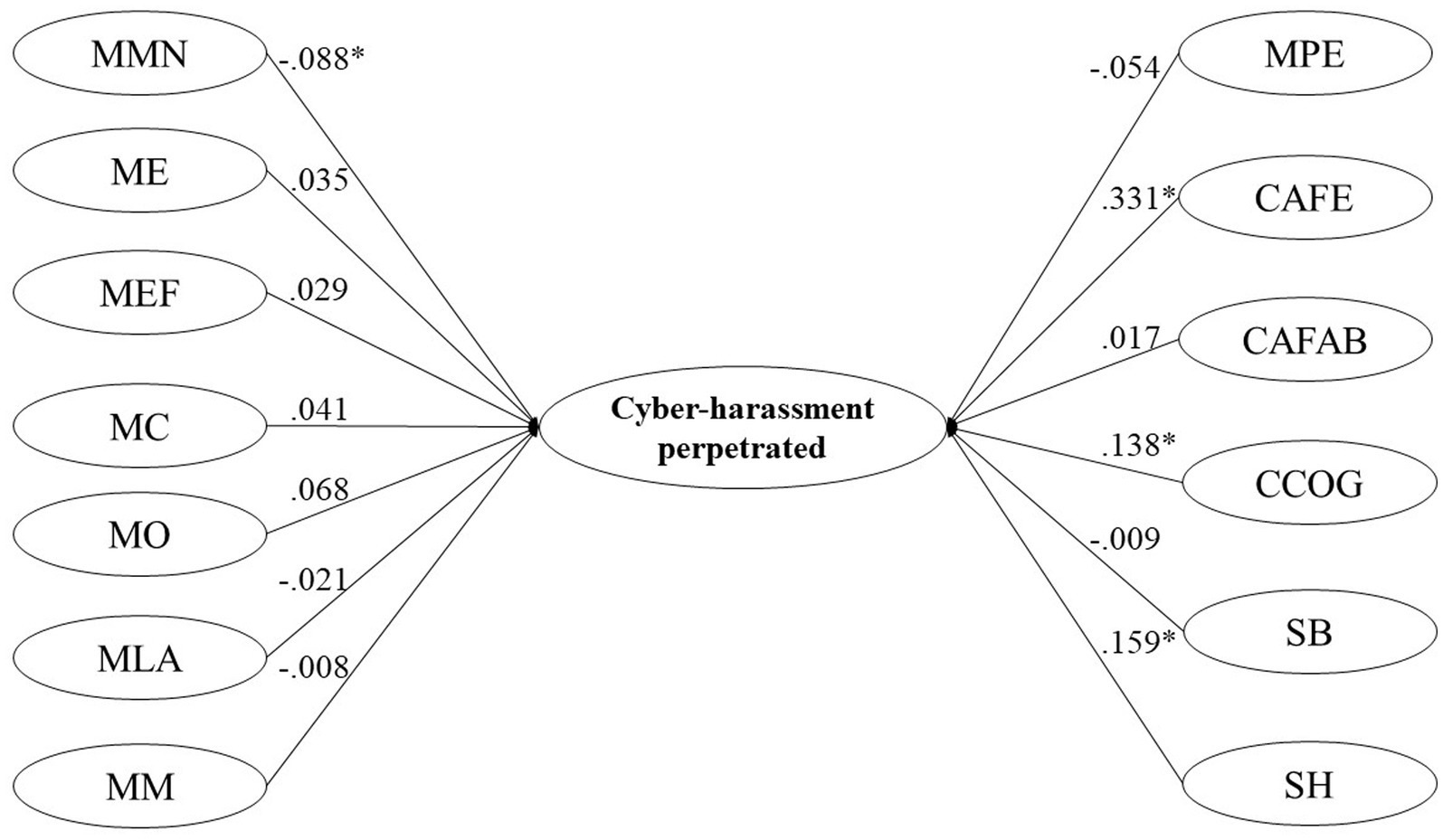

First, global fit indicators of the measurement models for each instrument are presented (Table 1).

The observed values (see Table 1) mirror fit indicators adequate to the recommended standards (CFI > 0.95; TLI > 0.95; RMSEA <0.06: Schreiber, 2017), which would indicate that the measurement models are a population-based explanation of the relationships observed in this sample so that they could be incorporated into a structural equation model.

Table 2 presents the global fit indicators of the structural equation models for Cyber-victimization (see Figure 1) and Cyber-harassment perpetrated dimensions (see Figure 2). Both models showed adequate levels of fit indicators.

Table 3 shows the effects of romantic love myths, Jealousy, and sexism on cyber-violence. In the Cyber-victimization model (see Figure 1), it was observed that cognitive Jealousy had a moderate direct effect (>0.3; Cohen, 1989) on cyber-victimization, whereas the myth of eternal passion had a slight inverse effect (>0.1; Cohen, 1989).

In the Cyber-harassment perpetrated model (see Figure 2), a moderate direct effect was observed on affective Jealousy relative to cheating and mild direct effects of cognitive Jealousy and hostile sexism. Although, given the sample size, a statistically significant effect of the better half myth is observed, its practical effect is null (>, 1; Cohen, 1989).

4. Discussion

This research aims to identify the shared effects that beliefs associated with dating violence (romantic love myths, jealousy, and sexism) have on cyber-violence victimization and perpetration. Overall, the results showed that, when analyzed from the combined effects, some dimensions of jealousy participate in both Cyber-victimization and Cyber-harassment perpetrated. In contrast, sexist beliefs only participate in perpetration, indicating that cyber-violence is related to the probability of assault but not the probability of being a victim. In the case of romantic love myths, no relevant effects were evidenced other than a slight protective role in the cyber-victimization of the myth of eternal passion.

In the case of cyber-victimization, it was observed that cognitive jealousy seems to increase the probability of suffering virtual aggression, which could be explained by the fact that people with a tendency to this type of cognition tend to tolerate relationships prone to more abusive situations. However, considering that the study is cross-sectional and correlational, it is impossible to establish with certainty a specific directionality of the effects. Consequently, it is not possible to establish causality, and there may be bidirectional effects. In this sense, another possibility is that experiencing cyber-victimization leads to increased cognitive jealousy by generating higher uncertainty about the relationship.

In the case of Cyber-harassment perpetrated, it was observed that affective jealousy related to cheating, but not to abandonment, plays a dominant role in the manifestation of virtual aggression. One possible explanation for this is that cheating-related effects are associated with high-activation negative emotions (e.g., anger), which are strongly associated with aggression. In contrast, affective jealousy related to abandonment would be linked to low-activation negative emotions (e.g., sadness). Additionally, to affective jealousy related to cheating and cognitive jealousy, and according to the literature (Branson and March, 2021; Toplu-Demirtaş et al., 2022), hostile sexism would increase the perpetration of cyber-violence by constituting a series of attitudes that favor and legitimize violence towards women, favoring adverse effects of high activation, by making negative attributions about women’s intentions (Orozco Vargas et al., 2022).

The present study is subject to some limitations typical of this type of design. The first of these refers to the social desirability biases of the participants, which were minimized through anonymity, mainly in the dimension that alludes to the perpetration of violence against the partner. Another limitation of this study is the typical restrictions of a non-probabilistic and self-administered sampling via social networks. The sample was mainly made up of women, which could lead to a bias in the data obtained by not collecting equivalent information on men and women. An explanation for this asymmetry of the sample is that women are more willing to participate in gender-based violence issues (Bolaños, 2015; Menéndez, 2017) and have a greater inclination to report acts of GBV compared to men (Rodríguez, 2014).

Future research should consider clarifying whether the proposed model presents possible differential effects by gender, given that there are discrepancies in the results obtained in this area, with more severe consequences evidenced in the female gender (Stonard, 2021), as well as a higher probability of being identified as victims (Taquette and Monteiro, 2019). Likewise, studies in this regard highlight that dating violence is more prevalent because it is exercised in a bidirectional manner (Rojas-Solís and Romero-Méndez, 2022), an aspect that requires further study, inviting the development of comparative analyzes of both perpetration and victimization of dating violence.

Finally, the findings of this study can be a reference to guide studies on dating violence in young couples and adolescents, as well as to develop prevention and intervention programs in the educational and health care settings, given that young people and adolescents come first to consult and seek help in this context (Valdivia-Peralta et al., 2019), therefore it is essential not to make this issue invisible and to implement actions and public policies that address these variables with the aim of establishing preventive models of dating violence in order to promote healthy loving relationships in young people and adolescents.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Scientific Ethical Committee of the Universidad de Tarapacá. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DR-C: contributed to conception, design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, organized the database, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and wrote sections of the manuscript. RF-U: contributed to design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote sections of the manuscript. FP-C: contributed to write sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was carried out with funding from the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID), a complementary benefit grant for operational expenses for a doctoral thesis research study, project code 21201938.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1212737/full#supplementary-material

References

Alegría del Ángel, M., and Rodríguez Barraza, A. (2015). Dating violence: perpetration, and mutual violence. A review. Act. Psic. 29, 57–72. doi: 10.15517/ap.v29i118.16008

Ariza Ruiz, A., Viejo Almanzor, C., and Ortega Ruiz, R. (2022). The romantic love and related myths in Colombia: a systematic review. Suma Psicol. 29, 77–90. doi: 10.14349/sumapsi.2022.v29.n1.8

Arnoso, A., Ibabe, I., Arnoso, M., and Elgorriaga, E. (2017). El sexismo como predictor de la violencia de pareja en un contexto multicultural. Anu. de Psicol. Juridica 27, 9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.apj.2017.02.001

Asparouhov, T., and Muthén, B. (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 16, 397–438. doi: 10.1080/10705510903008204

Barendse, M. T., Oort, F. J., and Timmerman, M. E. (2015). Using exploratory factor analysis to determine the dimensionality of discrete responses. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 22, 87–101. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.934850

Bolaños, M. F. (2015) Estudio del impacto de las redes sociales en el comportamiento de los adolescentes de 12 a 14 años en una unidad educativa en la ciudad de Guayaquil. Universidad Politécnica Salesiana Sede Guayaquil. Available at: https://dspace.ups.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/10296/1/UPS-GT001190.pdf

Bonilla-Algovia, E., and Rivas-Rivero, E. (2018). Psychometric properties of the reduced version of the myths scale toward love in a sample of Colombian students. Suma Psicol. 25, 162–170. doi: 10.14349/sumapsi.2018.v25.n2.8

Bonilla-Algovia, E., and Rivas-Rivero, E. (2021). Psychometric properties of the reduced version of the myths scale toward love in Salvadoran students. Psykhe 30, 1–9. doi: 10.7764/psykhe.2019.21737

Borrajo, E., and Gamez-Guadix, M. (2016). Cyber dating abuse: its link to depression, anxiety and dyadic adjustment. Behav. Psychol. 24, 221–235.

Bosch, E., Ferrer, V., García, M., Ramis, M., Mas, M., Navarro, C., et al. (2008) From love myths to intimate partner violence against women. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer. Available at: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/publicacioneselectronicas/documentacion/Documentos/DE0055.pdf

Branson, M., and March, E. (2021). Dangerous dating in the digital age: Jealousy, hostility, narcissism, and psychopathy as predictors of Cyber Dating Abuse. Comput. Hum. Behav. 119:106711. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106711

Cárdenas, M., Lay, S. L., González, C., Calderón, C., and Alegría, I. (2010). Ambivalent sexism inventory: adaptation, validation and relationship to psychosocial variables. Salud Sociedad 1, 125–135. doi: 10.22199/S07187475.2010.0002.00006

Cava, M.-J., and Buelga, S. (2018). Psychometric properties of the cyber-violence scale in adolescent couples (Cib-VPA). Suma Psicol. 25, 51–61. doi: 10.14349/sumapsi.2018.v25.n1.6

Cava, M. J., Buelga, S., Carrascosa, L., and Ortega-Barón, J. (2020a). Relations among romantic myths, offline dating violence victimization and cyber dating violence victimization in adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:1551. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051551

Cava, M. J., Martínez-Ferrer, B., Buelga, S., and Carrascosa, L. (2020b). Sexist attitudes, romantic myths, and offline dating violence as predictors of cyber dating violence perpetration in adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 111:106449. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106449

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2020) Preventing teen dating violence: What is teen dating violence?, Cdc.gov. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/TDV-factsheet_2020.pdf (accessed April 11, 2023).

Chapman, H., and Gillespie, S. M. (2019). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): a review of the properties, reliability, and validity of the CTS2 as a measure of partner abuse in community and clinical samples. Aggress. Violent Behav. 44, 27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.10.006

Cohen, J. (1989) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd. New Jersey: Hillsdate.

Del Castillo, C. C. (2018). El amor romántico, los estereotipos de género y su relación con la violencia de pareja. Aportaciones a la Psicol. Soc. 4, 459–474.

De Los Reyes, V., Jaureguizar, J., and Redondo, I. (2022). Cyberviolence in young couples and its predictors. Behav. Psychol./Psicol. Conduct. 30, 391–410. doi: 10.51668/bp.8322204n

Exner-Cortens, D., Eckenrode, J., and Rothman, E. (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics 131, 71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029

Fernández-Montalvo, J., and Echeburúa, E. (1997). Variables psicopatológicas y distorsiones cognitivas de los maltratadores en el hogar: un análisis descriptivo. Anál. Modif. Conducta 23, 151–180.

Garrido, M. C., and Barceló, M. V. (2019). Prevalencia de los mitos del amor romántico en jóvenes. OBETS: Revista de Ciencias Sociales 14, 343–371. doi: 10.14198/OBETS2019.14.2.03

Garzón González, R., Barrios Acosta, M. E., and Oviedo Córdoba, M. (2017). Violencia en las relaciones erótico afectivas entre adolescentes. Tesis Psicol. 12, 100–115. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=139057274008

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 491–512. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent sexism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 33, 115–188. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(01)80005-8

González Méndez, R., and Santana Hernández, J. D. (2001) Violencia en parejas jóvenes. Análisis y prevención. Madrid: Pirámide.

Guadix, M. G., Borrajo, E., and Zumalde, E. C. (2018). Partner abuse, control and violence through internet and smartphones: characteristics, evaluation and prevention. Papeles del Psicól. 39, 218–227. doi: 10.23923/pap.psicol2018.2874

Hancock, K., Keast, H., and Ellis, W. (2017). The impact of cyber dating abuse on self-esteem: the mediating role of emotional distress. Cyberpsychology 11:2. doi: 10.5817/cp2017-2-2

Ibabe, I., Arnoso, A., and Elgorriaga, E. (2016). Ambivalent sexism inventory: adaptation to Basque population and sexism as a risk factor of dating violence. Span. J. Psychol. 19, E78–E79. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2016.80

Lagarde, M. (2005) Para mis Socias de la Vida: Claves Feministas Para el Poderío y la Autonomía de las Mujeres, los Liderazgos Entrañables y las Negociaciones en el Amor. Barcelona: Horas y Horas.

León-Ramírez, B., and Ferrando Piera, P. J. (2014). Assessing sexism and gender violence in a sample of Catalan university students: a validity study based on the ambivalent sexism inventory and the dating violence questionnaire. Anuario de psicol. 44, 327–341. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=97036176006

López-Barranco, P. J., Jiménez-Ruiz, I., Pérez-Martínez, M. J., Ruiz-Penin, A., and Jiménez-Barbero, J. A. (2022). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the violence in dating relationships in adolescents and young adults. Rev. Iberoam. de Psicol. y Salud 13, 73–84. doi: 10.23923/j.rips.2022.02.055

Lu, Y., Van Ouytsel, J., Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., and Temple, J. R. (2018). Cross-sectional and temporal associations between cyber dating abuse victimization and mental health and substance use outcomes. J. Adolesc. 65, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.02.009

Makepeace, J. M. (1981). Courtship violence among college students. Fam. Relat. 30, 97–102. doi: 10.2307/584242

Malonda, E., Tur-Porcar, A., and Llorca, A. (2017). Sexism in adolescence: parenting styles, division of housework, prosocial behaviour and aggressive behaviour /Sexismo en la adolescencia: estilos de crianza, división de tareas domésticas, conducta prosocial y agresividad. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 32, 333–361. doi: 10.1080/02134748.2017.1291745

Marcos, V., Gancedo, Y., Castro, B., and Selaya, A. (2020). Dating violence victimization, perceived gravity in dating violence behaviors, sexism, romantic love myths and emotional dependence between female and male adolescents. Rev. Iberoam. de Psicol. y Salud 11, 132–145. doi: 10.23923/j.rips.2020.02.040

Menéndez, L. (2017) Estudio sobre la violencia de género presente en las redes sociales dirigido a adolescentes. Universidad Internacional de la Rioja. Available at: https://reunir.unir.net/bitstream/handle/123456789/6600/MENENDEZ%20MARTINEZ%2C%20LUCIA.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

O’Keeffe, N. K., Brockopp, K., and Chew, E. (1986). Teen dating violence. Soc. Work 31, 465–468. doi: 10.1093/sw/31.6.465

Orozco Vargas, A. E., Venebra Muñoz, A., Aguilera Reyes, U., and García López, G. I. (2022). Path analysis of patriarchal and sexist beliefs, attitudes toward violence, and dating violence. Psicol. Conductual 30, 309–331. doi: 10.51668/bp.8322116s

Pazos Gómez, M., Oliva Delgado, A., and Gómez, Á. H. (2014). Violence in young and adolescent relationships. Rev. Latinoam Psicol. 46, 148–159. doi: 10.1016/s0120-0534(14)70018-4

Pequeño, A., Reyes, N., Vidaurrazaga, T., and Leal, G. (2019) Amores Tempranos: Violencia en los pololeos en adolescentes y jóvenes en Chile. Available at: http://insmujer.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Amores-Tempranos_VF.pdf

Pérez-Marco, A., Soares, P., Davó-Blanes, M. C., and Vives-Cases, C. (2020). Identifying types of dating violence and protective factors among adolescents in Spain: a qualitative analysis of Lights4Violence materials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:2443. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072443

Peskin, M. F., Markham, C. M., Shegog, R., Temple, J. R., Baumler, E. R., Addy, R. C., et al. (2017). Prevalence and correlates of the perpetration of cyber dating abuse among early adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 358–375. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0568-1

Ramírez-Carrasco, D., Ferrer-Urbina, R., Acevedo-Peralta, M., Galleguillos-Beni, P., Maluenda-Maldonado, C., and Rojas-Muñoz, A. (2023a). “Development and Validity Evidence of the Myths of Romantic Love Scale (E-MAR) in Young Chileans,” Terapia Psicológica.

Ramírez-Carrasco, D., Ferrer-Urbina, R., Leiva Gutiérrez, J., Chamorro-Valdivia, C., and Miranda-Silva, N. (2023b). “Adaptation and validity evidence for the use of the cyber-violence scale in adolescent couples (CIB-VPA), in south American youth,” Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación - e Avaliação Psicológica RIDEP. Spain.

Rodríguez-Díaz, F., Juan Herrero, L., Rodríguez-Franco, C., Bringas-Molleda, S. P.-Q., and Pérez, B. (2017). Validation of dating violence questionnarie-R (DVQ-R). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 17, 77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2016.09.001

Rodríguez-Domínguez, C., Durán Segura, M., and Martínez-Pecino, R. (2018). Cyber aggressors in dating relationships and its relation with psychological violence, sexism and jealousy. Health Addict. / Salud Drog. 18, 17–27. doi: 10.21134/haaj.v18i1.329

Rodríguez, E., Calderón, D., Kuric, S., and Sanmartín, A. (2021) Barómetro Juventud y Género 2021. Identidades, representaciones y experiencias en una realidad social compleja. Madrid: Centro Reina Sofía sobre Adolescencia y juventud, FAD.

Rodríguez, J. A. (2014) “Violencia en el noviazgo de estudiantes universitarios venezolanos,” Archivos Crim. Crim. Segur. Priv., (12), pp. 4–20. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4714103 (accessed: April 11, 2023).

Rojas-Solís, J., and Romero-Méndez, C. (2022). Violencia en el noviazgo: Análisis sobre su direccio-nalidad, percepción, aceptación, consideración de gravedad y búsqueda de apoyo. Salud Drog. 22, 132–151. doi: 10.21134/haaj.v22i1.638

Rubio-Garay, F., López-González, M., Carrasco, M., and Amor, P. (2017). The prevalence of dating violence: a systematic review. Pap. Psicol. 37, 135–147. doi: 10.23923/pap.psicol2017.2831

Sanmartín, J. I., Iborra, Y. García E., and Martínez Sánchez, P. (2003) 3RD international report. Partner violence against women: Statistics and legislation. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307445582_III_Informe_Internacional_Violencia_contra_la_mujer_en_las_relaciones_de_pareja_Estadisticas_y_Legislacion

Sanpedro, P. (2005). El mito del amor y sus consecuencias en los vínculos de pareja. Disenso 45, 5–20.

Schreiber, J. B. (2017). Update to core reporting practices in structural equation modeling. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 13, 634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.06.006

Shorey, R. C., Temple, J. R., Febres, J., Brasfield, H., Sherman, A. E., and Stuart, G. L. (2012). The consequences of perpetrating psychological aggression in dating relationships: A descriptive investigation. J. Interpers. Violence 27, 2980–2998. doi: 10.1177/0886260512441079

Smith, K., Cénat, J. M., Lapierre, A., Dion, J., Hébert, M., and Côté, K. (2018). Cyber dating violence: prevalence and correlates among high school students from small urban areas in Quebec. J. Affect. Disord. 234, 220–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.043

Soler, E., Barreto, P., and Gonzales, R. (2005) “Cuestionario de respuesta emocional a la violencia doméstica y sexual,” Psicothema 267–274. Available at: https://www.psicothema.com/pdf/3098.pdf (accessed: April 11, 2023).

Stonard, K. E. (2021). The prevalence and overlap of technology-assisted and offline adolescent dating violence. Curr. Psychol. 40, 1056–1070. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-0023-4

Suh, Y. (2015). The performance of maximum likelihood and weighted least square mean and variance adjusted estimators in testing differential item functioning with nonnormal trait distributions. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 22, 568–580. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.937669

Taquette, S. R., and Monteiro, D. L. M. (2019). Causes and consequences of adolescent dating violence: a systematic review. J. Inj. Violence Res. 11, 137–147. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v11i2.1061

Tomaszewska, P., and Schuster, I. (2021). Prevalence of teen dating violence in Europe: a systematic review of studies since 2010. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2021, 11–37. doi: 10.1002/cad.20437

Toplu-Demirtaş, E., Akcabozan-Kayabol, N. B., Araci-Iyiaydin, A., and Fincham, F. D. (2022). Unraveling the roles of distrust, suspicion of infidelity, and jealousy in cyber dating abuse perpetration: An attachment theory perspective. J. Interpers. Violence 37:NP1432–NP1462. doi: 10.1177/0886260520927505

Ulloa, E. C., Jaycox, L. H., Marshall, G. N., and Collins, R. L. (2004). Acculturation, gender stereotypes, and attitudes about dating violence among Latino youth. Violence Vict. 19, 273–287. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.3.273.65765

Valdivia-Peralta, M., Fonseca-Pedrero, E., González Bravo, L., and Paíno Piñeiro, M. (2019). Invisibilización de la violencia en el noviazgo en Chile: evidencia desde la investigación empírica. Perf. Latinoam. 27, 1–31. doi: 10.18504/pl2754-012-2019

Valdivia Peralta, M. P., and González Bravo, L. A. (2014). Violencia en el noviazgo y pololeo: una actualización proyectada hacia la adolescencia. Rev. de Psicol. 32, 329–355. doi: 10.18800/psico.201402.006

Vizcarra, M. B., Poo, A. M., and Donoso, T. (2013). Dating violence prevention program. Rev. de Psicol. 22, 48–61. doi: 10.5354/0719-0581.2013.27719

Vizoso-Gómez, C., and Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. (2022). Programa socioeducativo de prevención de la violencia en el noviazgo en adolescentes. Int. J. New Educ. 10, 87–102. doi: 10.24310/ijne.10.2022.15556

Yela, C. (2000) El amor desde la psicología social. Ni tan libres ni tan racionales. Madrid: Pirámide. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28112223_El_amor_desde_la_psicologia_social_ni_tan_libres_ni_tan_racionales

Yela, C. (2003). The other side of love: myths, paradoxes and problems. Encuentros en Psicol. Soc. 1, 263–267.

Keywords: dating violence, cyber-violence, cyber-harassment perpetrated, cyber-victimization, jealousy, sexism, romantic love

Citation: Ramírez-Carrasco D, Ferrer-Urbina R and Ponce-Correa F (2023) Jealousy, sexism, and romantic love myths: the role of beliefs in online dating violence. Front. Psychol. 14:1212737. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1212737

Edited by:

Gordon Patrick Dunstan Ingram, University of Los Andes, ColombiaReviewed by:

César Armando Rey Anacona, Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, ColombiaMohamed Rafik Noor Mohamed Qureshi, King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2023 Ramírez-Carrasco, Ferrer-Urbina and Ponce-Correa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela Ramírez-Carrasco, ZHJhbWlyZXpjQGFjYWRlbWljb3MudXRhLmNs

Daniela Ramírez-Carrasco

Daniela Ramírez-Carrasco Rodrigo Ferrer-Urbina

Rodrigo Ferrer-Urbina Felipe Ponce-Correa

Felipe Ponce-Correa