94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 04 September 2023

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1209021

This article is part of the Research TopicCOVID-19 Epidemiological Situation as a Psychosocial Determinant of Trauma and StressView all 14 articles

Lydia Kastner1,2*†

Lydia Kastner1,2*† Ulrike Suenkel2,3†

Ulrike Suenkel2,3† Gerhard W. Eschweiler2,4

Gerhard W. Eschweiler2,4 Theresa Dankowski5,6

Theresa Dankowski5,6 Anna-Katharina von Thaler5,7

Anna-Katharina von Thaler5,7 Christian Mychajliw2,4

Christian Mychajliw2,4 Kathrin Brockmann7,8

Kathrin Brockmann7,8 Walter Maetzler5

Walter Maetzler5 Daniela Berg5

Daniela Berg5 Andreas J. Fallgatter2,3,8

Andreas J. Fallgatter2,3,8 Sebastian Heinzel5,6

Sebastian Heinzel5,6 Ansgar Thiel1,9

Ansgar Thiel1,9Introduction: Older age is a main risk factor for severe COVID-19. In 2020, a broad political debate was initiated as to what extent older adults need special protection and isolation to minimize their risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, isolation might also have indirect negative psychological (e.g., loneliness, stress, fear, anxiety, depression) or physical (e.g., lack of exercise, missing medical visits) consequences depending on individual strategies and personality traits to cope longitudinally with this crisis.

Methods: To examine the impact of individuals’ coping with the pandemic on mental health, a large sample of 880 older adults of the prospective longitudinal cohort TREND study were surveyed six times about their individual coping strategies in the COVID-19 pandemic between May 2020 (05/2020: Mage = 72.1, SDage = 6.4, Range: 58–91 years) and November 2022 in an open response format. The relevant survey question was: “What was helpful for you to get through the last months despite the COVID-19 pandemic? E.g., phone calls, going for a walk, or others.”

Results and Discussion: In total, we obtained 4,561 records containing 20,578 text passages that were coded and assigned to 427 distinct categories on seven levels based on qualitative content analysis using MAXQDA. The results allow new insights into the impact of personal prerequisites (e.g., value beliefs, living conditions), the general evaluation of the pandemic (e.g., positive, irrelevant, stressful) as well as the applied coping strategies (e.g., cognitive, emotional- or problem-focused) to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic by using an adapted Lazarus stress model. Throughout the pandemic emotional-focused as well as problem-focused strategies were the main coping strategies, whereas general beliefs, general living conditions and the evaluation were mentioned less frequently.

In early 2020, the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) caused a global health crisis that challenged our health care systems, upended daily life, and led to economic and social upheaval, e.g., lockdowns, quarantine and hygiene regulations (Chen, 2020; Wu and McGoogan, 2020; State of Baden-Württemberg, 2023). Estimates indicate that more than 660 million people worldwide were infected with SARS-CoV-2 by January 2023, of which approximately 6.7 million were fatal (Abab et al., 2022; Johns-Hopkins-University, 2023). Although, most people had only mild to moderate diseases, a substantial minority had a higher risk for severe COVID-19 and adverse health outcomes, such as long- or post-COVID (Abab et al., 2022; Subramanian et al., 2022). Across several countries, mortality rates increased exponentially depending on age and multimorbidity (Bonanad et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023). Early on, age had been identified as most significant risk factor for severe COVID-19 (Chen et al., 2023) because older adults also have a higher prevalence of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes (Zhu et al., 2020; Kompaniyets et al., 2021b), obesity (Kim et al., 2021; Kompaniyets et al., 2021a,b), coronary heart (Lippi and Henry, 2020; Kim et al., 2021), and neurocognitive diseases (Rosenthal et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021). For instance, it was found that mortality risk increased up to 26% for adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias compared to 2019 (for adults without dementia the risk increased up to 12%, Gilstrap et al., 2022).

This sparked controversial debates about how to deal with an increased vulnerability for COVID-19 in older (or particularly frail) adults. It was claimed that these adults need both a special protection and isolation to minimize their risk of infection and they also need to maintain independence and autonomy to avoid negative psychological (e.g., depression, loneliness, anxiety), and physical consequences (e.g., lack of exercise, missing medical visits and using negative coping strategies, AgeUK, 2020; Chen, 2020; Promislow and Anderson, 2020; Chen et al., 2023). In Germany, point prevalence for a depressive episode in older adults was 7% (95% CI 4.4–10.6%), and for adults aged 75+ years even 17% (95% CI 9.7–26.1%, Luppa et al., 2012). Despite the expectation that social isolation would lead to a significant health care gap and increased depressive symptoms and loneliness, studies showed that the psychosocial well-being of older adults remained remarkably stable throughout the pandemic (Betsch et al., 2020; Röhr et al., 2020; Minahan et al., 2021; van den Besselaar et al., 2021; Dankowski et al., 2023). Psychological stress, however, was only elevated at the beginning of the pandemic and depended on health status, functional resources, individuals’ participation/activity and living environment (Gaertner et al., 2021). In general, these results might be surprising if we consider the COVID-19 pandemic as a global health crisis in which individuals had to adapt quickly to changes in work, social activities, and quarantine restrictions (Giordano, 2020; Gaertner et al., 2021; Bhattacharjee and Ghosh, 2022). Several studies investigated how older adults coped with stress arising from the pandemic and to what extent individual characteristics, resilience and various coping strategies played a role in this – but only at one particular stage of the pandemic (e.g., Greenwood-Hickman et al., 2021; Bhattacharjee and Ghosh, 2022; Halamová et al., 2022; Iswatun et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2022; Joseph et al., 2023). Resilience, thus, describes the capacity to recover quickly from difficult situations and stressful life events, whereby this in turn depends not only on the psychological prerequisites of the individual but can be considered as a dynamic process allowing positive adaptation in unknown situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Coping or coping strategies describe the active process and specific behavior that protects oneself to avoid negative experiences during stressful life events (Pearlin and Schooler, 1978; Carver et al., 1989; Chen, 2020). Since feelings of stress are a cumulation of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors taking into account internal and external demands, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) described a model in which perceived stress depends on primary appraisal of a stimulus as irrelevant, positive or stressful. After the primary appraisal, when a person has determined the relevance and consequences of the stimulus for him- or herself, the secondary appraisal involves the evaluation of resources. Therefore, skills the person has acquired in previous stressful situations, self-confidence, but also material resources or social support are needed. The fewer resources a person has to cope with a specific stressful situation, the more intense the stress response will be. These two appraisals do not temporally occur in sequence but may overlap and influence each other and are characterized by person’s perception. After the appraisal is completed, coping occurs. The focus of coping can be on changing the external situation (problem-oriented coping), e.g., through the structuring of daily activities or hygiene and protection measures, or on changing internal states and feelings (emotion-oriented coping), e.g., through social contacts, self-care, mindfulness. Since the COVID-19 pandemic could be described as a psychological stressful experience, the individual’s cognitive evaluation of the situation (as positive, irrelevant, or stressful) and the resources available to the individual may determine whether coping is necessary at all or the extent to which coping strategies are (or need to be) used.

In the present study, we were interested in how older adults with an increased vulnerability for severe COVID-19 cope with the pandemic-related circumstances over time and how these strategies change over time.

Since very little is known in the literature about how vulnerable populations deal with the COVID-19 pandemic longitudinally, we posed the following research question: How do older adults cope with the COVID-19 pandemic over time? To answer our research question, we sent questionnaires to a vulnerable population of older adults at continuous intervals over a period of 2.5 years (for more detailed information, see 2.1 research sample). In these, among many other topics, an open-ended question was asked about what the participants experienced as helpful during the pandemic from May 2020 to November 2022. Our first aim was to categorize the responses to the open-ended question (text fragments) using qualitative data analysis and develop a comprehensive category system. Furthermore, in an exploratory quantitative analysis, we aimed to examine associations between coping (strategies) and demographic variables (age, education level), fear of COVID-19, perceived stress, resilience, depression, loneliness, health-related quality of life, and physical (in)activity, as well as gender differences. This proceeding represents a mixed-methods approach.

The cohort of the present study originates from the prospective longitudinal cohort study “Tübingen Evaluation of Risk Factors for Early Detection of NeuroDegeneration” (TREND), which was initiated in 2009 and is currently in its 5th follow-up (Wave 6). Participants are examined in 2-year intervals. The main purpose of the TREND study is to identify, define, and validate risk factors and prodromal markers for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.1 For TREND, older adults (aged 50+ years) from the Neckar-Alb and Stuttgart regions (in southern Germany) were recruited, primarily participants with specific prodromal markers for neurodegeneration (“enriched cohort”): lifetime depression, hyposmia, or (probable) REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). In-depth details about the inclusion and exclusion criteria of TREND can be found in the study protocol (Gaenslen et al., 2014). In addition, participants were included who had previously taken part in another study for early detection of Parkinson’s disease which was population-based (“Prospective evaluation of Risk factors for Idiopathic Parkinson’s Syndrome,” PRIPS; Berg et al., 2010, 2013). A total of 1,201 participants took part in at least one visit of the TREND study. Membership to one or more risk groups (depression, hyposmia, probable RBD) was determined at the first study visit using tests and questionnaires. At the first study visit, 60% of participants had at least one prodromal marker (30% depression, 36% hyposmia, 18% probable REM sleep behavior disorder; for more details see Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, 14% had first-degree relatives with Parkinson’s disease, and 31% with dementia, and participants thus had an increased risk of developing the diseases. The study follows the guidelines for good scientific practice at the University of Tübingen (Germany), the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its later amendments and was approved by the local ethics committee of the University Hospital Tübingen (No 90/2009BO2). All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

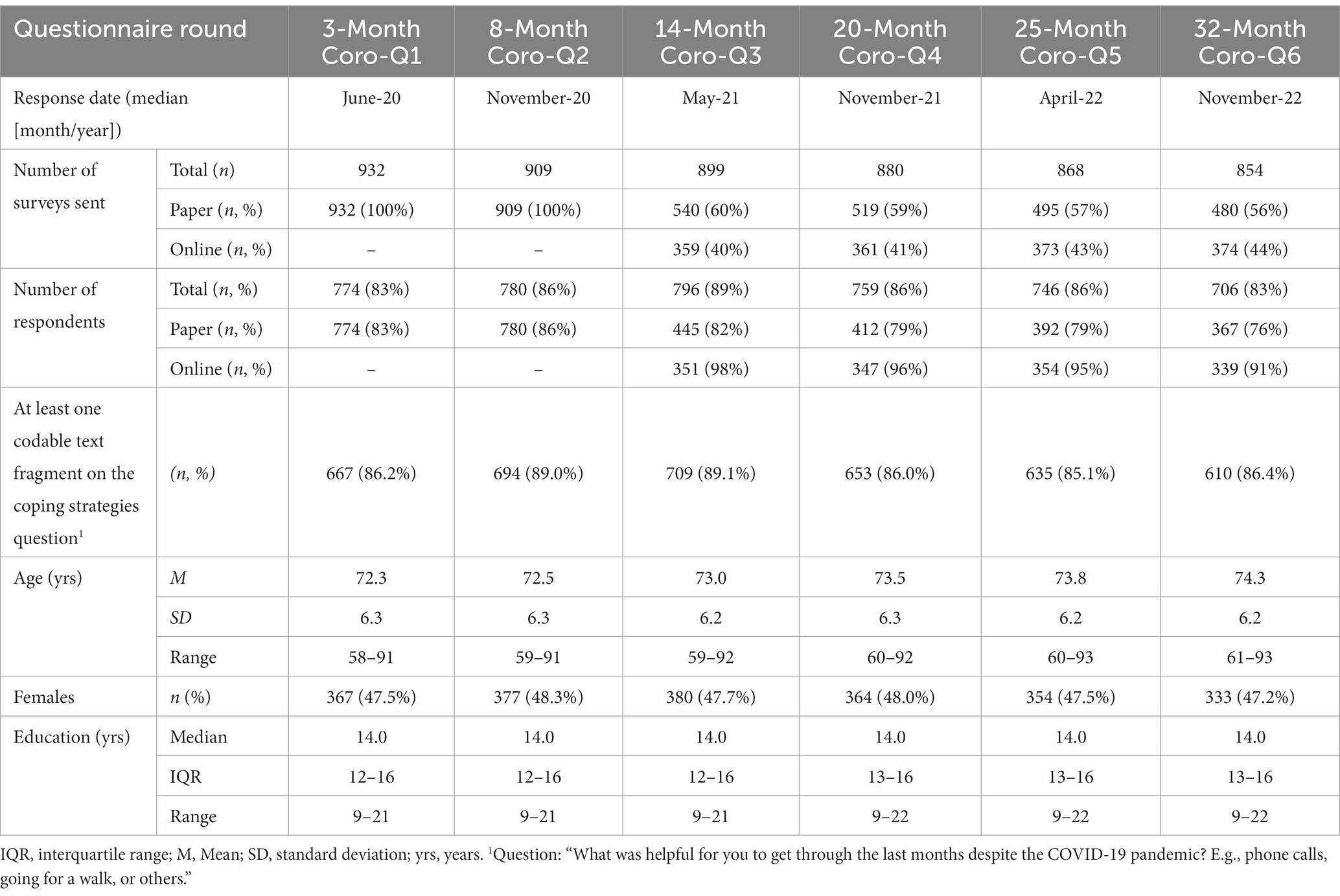

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown and hygiene recommendations of the regional government and the Robert Koch Institute, the regular TREND data collection had to be paused immediately in March 2020 to minimize our participants’ risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 (Governmental Regulation of the State of 266 Baden-Württemberg from 03/17/2020, CoronaVO). In the following, the research question arose how our cohort with increased vulnerability (older age, increased risk for neurodegenerative diseases) would cope with the pandemic longitudinally, especially the protective measures such as self-isolation and general restrictions. As it is known from the literature, adults who are at increased risk for dementia are also at increased risk for severe COVID-19 progression and accelerated cognitive decline (Chen et al., 2023). To investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our cohort, six Corona questionnaires (Coro-Q, in the following referred to as Coro-Q1 to Coro-Q6 in Tables/Figures, e.g., Coro-Q1 means Corona questionnaire No. 1) on general, health- and pandemic-related aspects were sent to the participants via post and later also online. Eight hundred and eighty participants of the TREND cohort were willing to take part in these COVID-19 pandemic related questionnaires at least once (mean age in May 2020: M = 72.1, SD = 6.4, Range: 58–91 years; 48.3% females, years of education: Mdn = 14, IQR: 12–16 years; for demographics of each questionnaire round see Table 1). The first questionnaire was sent by post in May 2020, followed by five more questionnaires approximately every 6 months (paper or online questionnaires, depending on participants’ preference). The response rates for each questionnaire were > 80%. Participants did not reach any financial or other benefit of the participation in the pandemic-related questionnaire study. However, it should be noted that most participants had been taking part in TREND for over 10 years at the onset of the pandemic, and many participants had developed a strong commitment to the study and a bond with the longstanding, consistent study team over time. This may have contributed to the exceptionally high response rates. Table 1 provides an overview of the questionnaire rounds [Coro-Q1 to Coro-Q6, and demographic characteristics of the respondents (Ntotal = 4,561)]. Of the 880 participants who completed at least one Corona questionnaire (Coro-Q), 56% had at least one prodromal marker for neurodegeneration (29% depression, 31% hyposmia, 17% probable REM sleep behavior disorder); 14% had first degree relatives with Parkinson’s disease and 35% with dementia (for exact numbers and percentages for each risk group and combination of prodromal markers see Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1. Questionnaire rounds (Coro-Q1 to Coro-Q6) and demographic characteristics of the participants.

As of June 2023, TREND has a total of 77 subjects who have developed a severe neurodegenerative disease (Parkinson’s disease, dementia, or other); of these, 27 have completed a Corona questionnaire at least once (14 subjects diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, 11 diagnosed with dementia, one diagnosed with progressive generalized chorea, one with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), with 13 of these participants receiving their diagnosis during the course of the pandemic (2021 to 2023) (four Parkinson’s disease, nine dementia). Overall, the subcohort of TREND that completed at least one Corona questionnaire contains 3% subjects with a severe neurodegenerative disease.

From May 2020 to November 2022, more than 800 older adults were surveyed six times (Coro-Q1 to Coro-Q6) at 6-month intervals about their fear of getting COVID-19, depression, perceived stress, loneliness, resilience, health-related quality of life, and level of physical (in)activity. Table 2 shows selected material used in the questionnaire rounds. At the end of each of the abovementioned six Coro-Q questionnaires, there was a question about personal coping with the COVID-19 pandemic in an open-ended response format: “What was helpful for you to get through the last months despite the COVID-19 pandemic? (E.g., phone calls, going for a walk, or others).” Because the active subset of the TREND cohort at the beginning of the pandemic still consisted of more than 900 subjects, we were unable to interview each participant in person using semi-structured interviews. For this reason, we had to rely on postal or online questionnaires. In total, we obtained 4,561 records in the six biannual questionnaire rounds. An impressive and unique set of qualitative longitudinal data on the pandemic, health-related and psychosocial factors of older adults’ personal coping with the COVID-19 pandemic was collected over a 2.5-year period. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Tübingen (Harris et al., 2009).

The core of this article is a mixed-methods analysis to answer our research question on how older adults with increased vulnerability for severe COVID-19 (Chen et al., 2023) deal with the pandemic situation longitudinally (cf. mixed-methods or hybrid approach, Hussy et al., 2010).

First, a qualitative content analysis was conducted on the textual information that participants were asked to provide at the end of the questionnaire by indicating what they found helpful for coping with the pandemic. In response to the open-ended question “What was helpful for you to get through the last months despite the COVID-19 pandemic? (E.g., phone calls, going for a walk, or others),” we received answers in text format. These ranged from one-word answers through lists to shorter or longer text fragments (in complete sentences). For organizing and coding the text material, we used the qualitative analysis software MAXQDA (VERBI-Software, 2021). MAXQDA is a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) designed to assist researchers in managing and analyzing qualitative and mixed-methods data, provided in a range of tools to facilitate the organization, coding, analysis, and visualization of data. As method, we used the widely used and established qualitative content analysis according to Mayring (2015, 2020), which enabled us to analyze the text material (summarizing, explicating, structuring), form categories, and combine two approaches: (1) inductive category development (“bottom-up approach”) and (2) deductive category application (“top–down approach”). Accordingly, in a first step, we inductively coded the text material and derived a preliminary category system. In long team and expert discussions, it turned out that the code system so far was insufficient regarding many text passages that described for instance general value beliefs or the evaluation of the pandemic situation and did not directly represent coping strategies (e.g., “faith in god,” “having a garden”). Due to this problem, some text passages from our participants could not be logically integrated into our category system. At this point, as it is also part of the method according to Mayring, we added the deductive approach and started searching for definitions and classifications of coping and coping strategies (for an overview see Skinner et al., 2003). Thereby, we encountered Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional stress model (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). This model offered a solution for handling text passages about general value beliefs or the evaluation of the pandemic situation. Thus, in a second step, we restructured our category system deductively using the theoretical framework of Lazarus and Folkman by considering the pandemic situation as stress. Overall, after inductive category formation with recourse to the transactional stress model (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), we were able to deductively classify all text material in the sample into a logical and comprehensive category system.

Once the final category system was defined, we were able to calculate the numbers for each category and each participant for all six questionnaire rounds. In a quantitative exploratory analysis, we investigated how our main categories correlate with demographic variables (age, years of education), depression, perceived stress, resilience, loneliness, health-related quality of life, physical (in)activity, and examined gender differences (Herrera-Añazco et al., 2022; Peyer et al., 2022). Kendall’s tau B was used for correlations and Mann–Whitney U tests for group comparisons because of the skewness of the data. Quantitative data analysis was performed using the software SPSS version 29.0 (IBM-Corp, 2021).

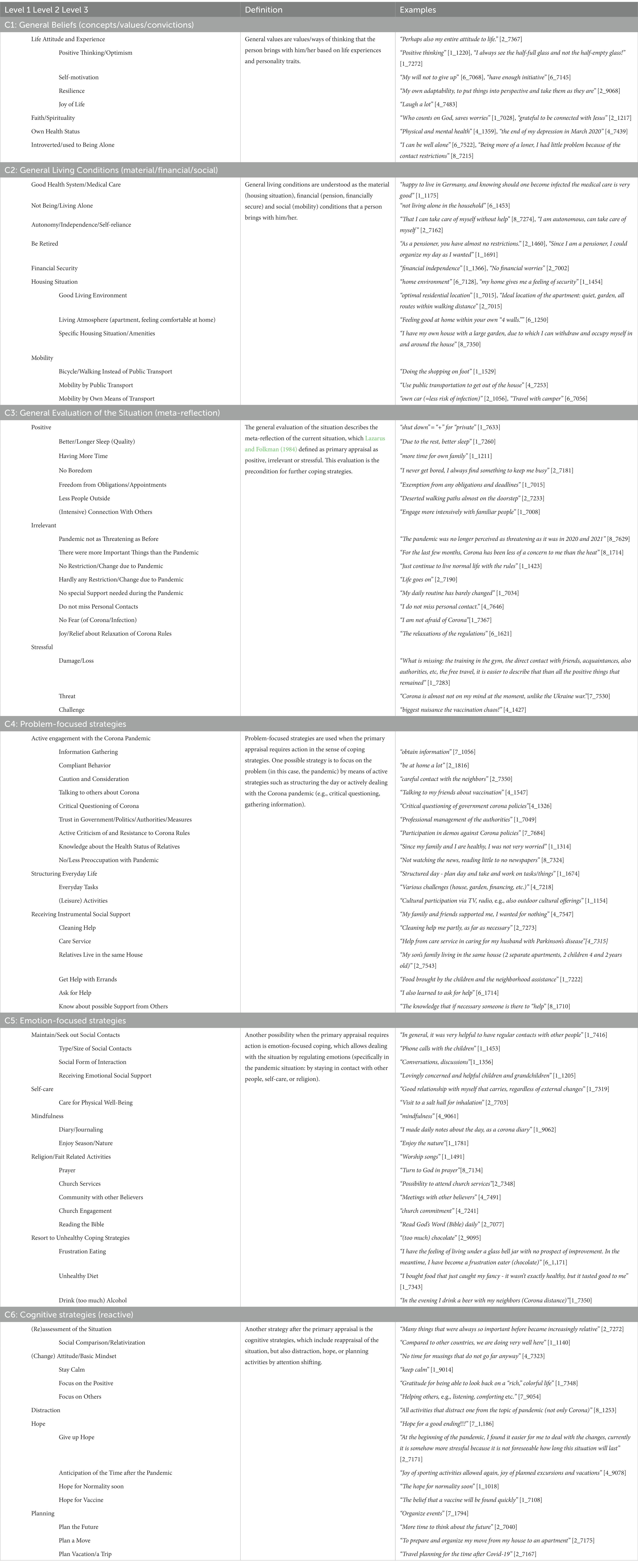

Through the qualitative content analysis in MAXQDA and deductively using an adapted/extended Lazarus stress model, a total of 20,578 text passages could be coded and 427 categories could be formed which are organized on seven hierarchic levels, with level 1 representing the highest and level 7 the lowest (for details, see Supplementary Table S1). In this article, we use the term “categories” to refer to the related content that has been organized hierarchically. Categories at higher levels represent supercategories and stand for a topic area (e.g., problem-focused strategies) to which further categories are subordinated (e.g., structuring everyday life). The more detailed a topic is represented in the category system, the more levels that topic has. The categories are mutually exclusive and the representation in Supplementary Table S2 is not cumulative, since it was possible that very generally formulated text fragments were sorted directly into a higher level without belonging to one of the subordinate levels. However, the category system can be aggregated at each level by cumulating the numbers of the lower levels and adding them to the numbers of the higher levels.

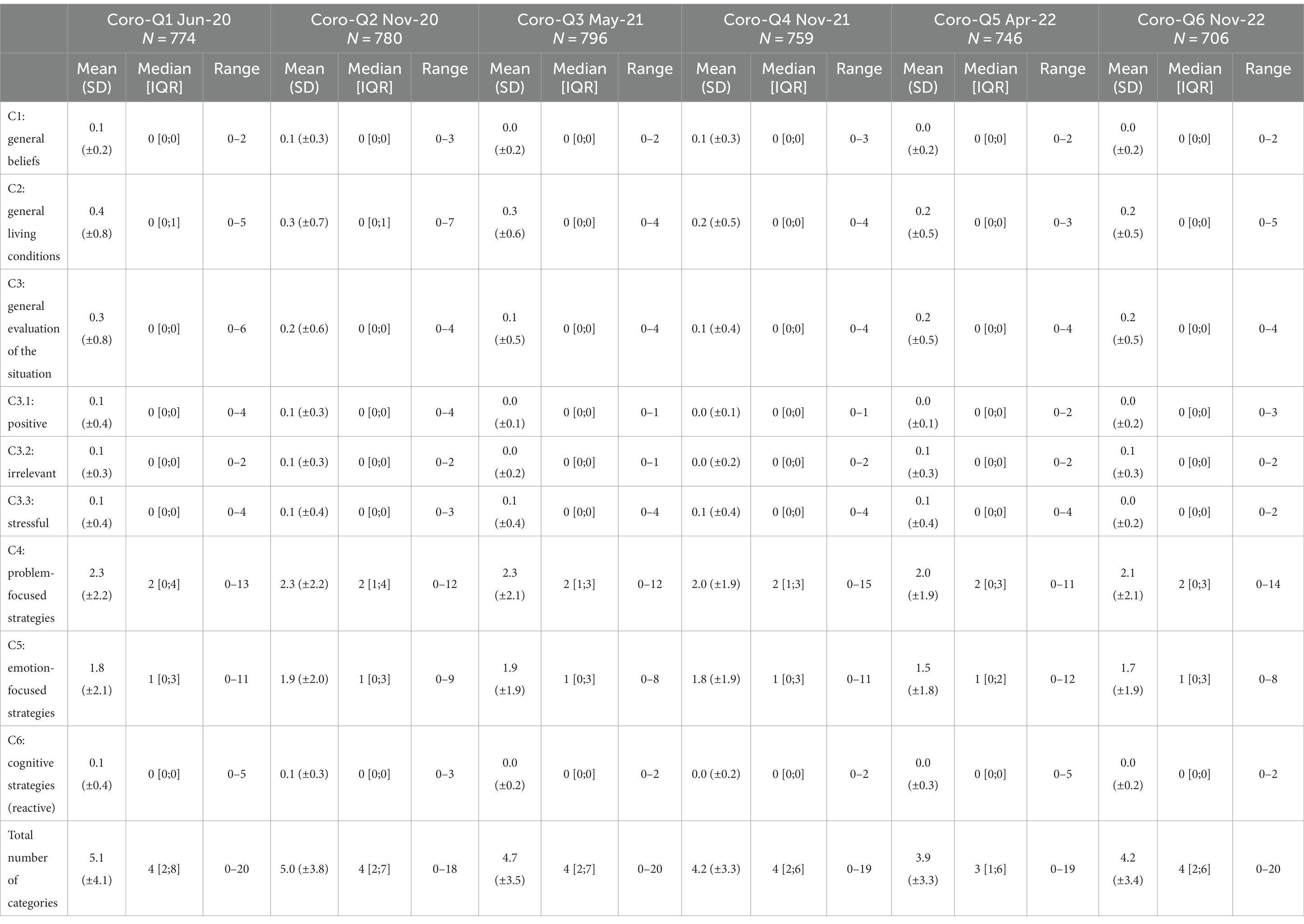

We obtained six main categories on level 1 (C1–C6): (1) C1: General Beliefs (concepts/values/convictions) (N = 234), (2) C2: General Living Conditions (material/financial/social) (N = 1,252), (3) C3: General Evaluation of the Situation (meta-reflection as positive, irrelevant, or stressful) (N = 863), (4) C4: Problem-focused Strategies (N = 9,925), (5) C5: Emotion-focused Strategies (N = 8,049), (6) C6: Cognitive Strategies (reactive) (N = 255). Thereby, C1 and C2 describe the general prerequisites that a person possesses in terms of values and material/financial/social resources, whereas C3 represents the general evaluation of the situation in the form of the primary appraisal as positive, irrelevant, or stressful. This is followed by the secondary appraisal, considering whether sufficient resources are available to deal with the problem. C4–C6 represent the specific coping strategies in dealing with the problem, where either the external situation is to be changed by problem-focused coping (e.g., daily structuring) or the internal attitude with respect to emotions (e.g., by emotion regulation through eating, social contacts) or cognitions (e.g., by distraction, attitude change). A definition of the 6 main categories (and subcategories up to level 3) and examples can be found in Table 3. For details on the distribution of the numbers of the main categories among the 6 questionnaire rounds, see Table 4 (a more detailed table with all 427 categories can be found in the Supplementary Table S1) and for relative frequencies of how often each category was used, see Table 5. On average, across all six questionnaire rounds, participants most frequently used problem-focused coping strategies in dealing with the pandemic {Coro-Q1 (Median [IQR]): 2 [0;4]; Coro-Q2: 2 [1;4]; Coro-Q3: 2 [1;3]; Coro-Q4: 2 [1;3]; Coro-Q5: 2 [0;3]; Coro-Q6: 2 [0;3], cf. Table 4}. Few participants reported their general value beliefs, general life circumstances, their general evaluation of the pandemic or cognitive strategies (see Tables 4, 5).

Table 3. A definition of the 6 main categories (subcategories up to level 3) and participants’ examples.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of the six main categories: an overview of how often participants named each strategy.

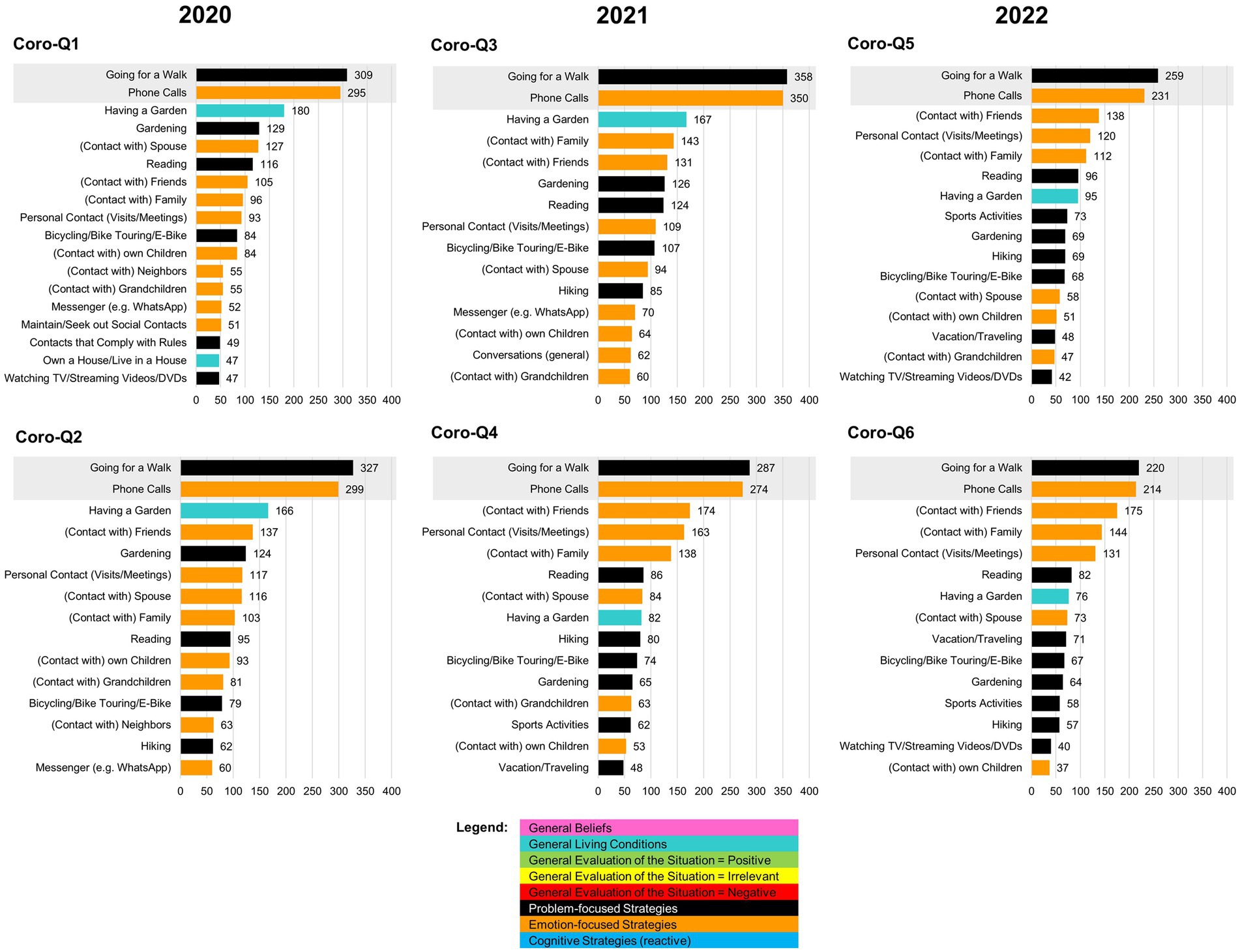

In further analyses, we were interested in what was most frequently mentioned by the participants. Therefore, for each round of questionnaires, the 15 most frequently mentioned categories were identified from the 427 categories (Figure 1). In 2020, among the top 15, going for a walk (top 1) and phone calls (top 2), as well as having a garden (top 3), were most frequently mentioned. In addition, many emotion-focused strategies were mentioned, such as contact with a spouse, friends, family, and neighbors. In 2021, going for a walk and phone calls continued to be among the top 3, with more problem-focused strategies added, such as bicycling, gardening, sports activities, or traveling, which was found again in a relatively similar manner in 2022. Across all rounds, emotion-focused strategies (social contact to individuals online or personally) were consistently listed. However, it should be noted that the top 15 are probably skewed by the fact that examples were suggested in the open-ended question. For “general living conditions,” two items reached the top 15 at the beginning of the pandemic, namely “having a garden” and “own a house/live in a house.” During the pandemic, “having a garden” lost some ranks, but remained consistently among the top 15 mentions. In contrast, general beliefs and evaluation of the situation were mentioned less frequently, so that they do not appear in the top 15 (see Discussion). For a more detailed overview of the top 15, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the Top 15 mentioned items for coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants had to answer the question “What was helpful for you to get through the last months despite the COVID-19 pandemic? E.g., phone calls, going for a walk, or others”.

In the exploratory analysis, we were interested in whether there is a relationship between our six main categories (level 1, but for content reasons, C3 “general evaluation of the situation” was also analyzed on level 2) and demographic variables (age, sex, years of education), depression, perceived stress, resilience, loneliness, health-related quality of life and physical inactivity. Resilience was only recorded from the 2nd corona questionnaire (Coro-Q2) onwards. For this reason, no correlations with our main categories are available for the first corona questionnaire (Coro-Q1).

Results are shown for the six main categories for each of the six questionnaire rounds in Supplementary Tables S3–S9. Although most of the correlations were weak (r < 0.3), correlations r > 0.1 or correlations that showed a pattern over time were reported. Most of the significant correlations were as expected: Rating the situation as irrelevant (C3.2) correlated negatively with fear of COVID-19 and perceived stress, while positive correlations were found with resilience (Coro-Q4/Coro-Q5) and health-related quality of life (Coro-Q4). In contrast, if the situation was rated as stressful (C3.3), a positive correlation with perceived stress and a negative correlation with health-related quality of life emerged as an almost continuous pattern. In addition, a weak negative correlation between rating the situation as stressful and resilience was found in the last three questionnaire rounds. Not surprisingly, at several time points, depression and loneliness also correlated positively with the evaluation of the situation as stressful. For problem-focused strategies (C4), which include (leisure) activities and among them sports, a negative correlation with physical inactivity was found as a consistent pattern. At four time points, fear of COVID-19 also correlated positively with the problem-focused strategies, which include pandemic-related activities (e.g., adhering to Corona rules, seeking information). Emotion-focused strategies (C5), which include maintaining social contacts, showed a negative correlation with loneliness in the last two questionnaire rounds, a pattern of negative correlation with age, and a positive correlation with education in the first two questionnaire rounds. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning a negative correlation of general beliefs (C1) with fear of COVID-19 at two time points (Coro-Q2 and Coro-Q4) and a positive correlation of problem-focused strategies (C4) with years of education (Coro-Q2, Coro-Q3). For total number of codes, there was an almost consistent pattern of a positive correlation with fear of COVID-19 and a negative correlation with physical inactivity. There was also a negative correlation between the total number of codes and age and a positive correlation with years of education in the first two rounds of questionnaires. In the last questionnaire rounds, the total number of codes correlated negatively with loneliness and positively with health-related quality of life. No pattern or noteworthy individual correlations were found for general living conditions (C2), evaluation of the situation as positive (C3.1), and cognitive strategies (C6).

Since gender differences are found in many questionnaires on stress management, resilience, depression, anxiety, and physical activity (Herrera-Añazco et al., 2022; Peyer et al., 2022), we were also exploratively interested in whether these differences could also be found in our categories generated by the qualitative analysis. Regarding gender-related group comparisons using Mann–Whitney U-Test, women reported more positive aspects when evaluating the situation at the beginning of the pandemic compared to men (Coro-Q1, Coro-Q2). They also reported more strategies overall in all questionnaire rounds, but especially emotion-focused strategies, showing small effect sizes (r between 0.16 and 0.28). In addition, women also reported more problem-focused strategies at four time points. For an overall overview of all correlations and group comparisons, see Supplementary Tables S3–S9.

In the current article, we were interested in how older adults with increased vulnerability for severe COVID-19 cope with the pandemic situation in the long-term. In order to better classify older adults’ coping strategies, a qualitative approach was chosen to identify long-term coping strategies by using a qualitative content analyses according to Mayring (2000, 2015). Contrary to the expectations that older adults might have difficulties withstanding the pandemic situation (Ayalon et al., 2020; Minahan et al., 2021), especially with regard to the psychosocial effects, the results of this article highlight older adults’ resilience in terms of their coping and adaptability during the crisis of COVID-19. Our main finding in this study was that the Lazarus and Folkman (1984) “extended” transactional stress model helped to classify the responses from over 800 participants over a period of 2.5 years.

According to text material, we identified six main categories that comprised the coping strategies mentioned by participants. Categories included three types of coping mechanisms (problem-focused, emotion-focused, or cognitive), as well as general beliefs, living conditions, and the specific evaluation of the situation as positive, irrelevant, or stressful. In line with other studies investigating coping strategies in older adults, the transactional stress model allowed a comprehensive and individual-centered view of the stress-inducing events, such as the pandemic (Minahan et al., 2021; Whitehead and Torossian, 2021). In contrast, the main criticism in this model was the individual-centered view of stress-induced events, without sufficiently considering the situation (e.g., Broda, 1990). The model assumed that an individual experiences stress when he or she perceived an imbalance between him- or herself and the environment, and that this imbalance was classified as a threat.

Especially, for the evaluation of the situation as irrelevant, we found that the lower the fear of COVID-19 and the lower the perceived stress, the more text fragments belonging to this category could be coded. We also found a positive correlation between the evaluation of the situation as irrelevant and resilience, which indicated that more resilient individuals were better able to cope with stress and assess situations as stressful less frequently. As expected, the higher the perceived stress and depression and the lower the resilience and health-related quality of life, the more frequently codable text question segments were found to evaluate the situation as stressful. In line with our expectations, we found for the problem-focused strategies (C4) including daily structuring, (leisure) activities and sports, that the higher the number in this category, the higher the level of physical activity reported in the standardized questionnaire. Similarly, the correlation with fear of COVID-19 could be explained by the fact that C4 also included a subcategory on “active engagement with the corona pandemic” (e.g., seeking information, following corona rules, taking protective measures, keeping distance). For the emotion-focused strategies, which included the large subcategory of “maintaining and seeking out social contacts,” while it was not surprising that loneliness was negatively correlated with the number of codes in this category, it was interesting that the greater the fear of COVID-19 reported, the higher the number of codes in this category. It probably played a large role that contacts could be maintained at a distance that did not carry a risk of infection, e.g., telephone calls (top 2 among all categories), video conferencing, and messengers. A potential explanation for choosing telephone calls, video conferencing, and messengers might be the rise of the internet and social media platforms (34% of older adults use social media platforms, Anderson and Perrin, 2017). Despite the very weak correlations the pattern of fewer emotion-focused strategies being mentioned with increasing age may be because older adults less frequently use modern means of communication or have smaller social networks. In contrast, there seemed to be a correlation of education with emotion-focused strategies, which might also be explained by the fact that education allowed more opportunities to use different means of communication. The fact that the greater the fear of COVID-19, the higher the total number of codes, was probably since people who were less engaged with the pandemic due to low fear also have a lower need to communicate on this topic (in this case, the question of what helped them deal with the pandemic). The quantitative analysis of the data did confirm several (plausible) relationships between coping and psychosocial factors, which support the validity of our qualitative category system. In other studies, gender differences were found in many questionnaires on stress management, resilience, depression, anxiety, and physical activity, in the sense that women reported be more stressed, more depressed and anxious, and were less physically active (Herrera-Añazco et al., 2022; Peyer et al., 2022); this could be confirmed by our data. Regarding the data on coping during the pandemic, we found that women assessed the situation more positively than men at the beginning of the pandemic (early summer and late fall 2020). It is possible that mostly women responded who had suffered little from the effects of the pandemic and were therefore happy to answer this open-ended question. This finding could possibly also be explained by the fact that in our study women wrote more text overall and achieved a higher number of categories than men. It is already known from other studies that women have a higher need to communicate in open response formats (Moreno and Mayer, 1999). Otherwise, the coping strategies mentioned are consistent with other studies (Finlay et al., 2021; Greenwood-Hickman et al., 2021). For instance, Finlay et al. (2021) reported strategies such as exercising, modifying routines, going outdoors, following public health guidelines, staying socially connected. Negative coping strategies such as overeating were rarely mentioned.

There are several strengths of this study, including (a) a large number of qualitative data collected over 2-year period from over 800 subjects, (b) these data belong to a long-term prospective data collection long before the COVID-19 pandemic in a well-characterized cohort of older adults; (c) continuous rounds of questionnaires with specific questions on pandemic-, health- and psychosocial factors, and (d) an open-ended question about individual coping strategies. The question was deliberately chosen in an open-ended format to allow us to capture the unpredictable developments of the pandemic and not limit ourselves to coping strategies mentioned in already established coping questionnaires (e.g., COPE inventory). However, there are also some limitations that should be mentioned: First, there might have been a bias due to the specific wording of the open question about coping strategies, since examples were given in addition to the specific question (e.g., making phone calls, going for a walk, etc.). This might have led participants to think more about problem-solving strategies and therefore these were mentioned more often in our study. Moreover, the wording of the question about coping strategies seemed to suggest to participants that only positive strategies should be mentioned, so dysfunctional strategies for dealing with the pandemic were only mentioned 1–2 times in all questionnaire rounds. However, the aim was to look at the helpful strategies and not at the obstacles.

Another limitation of our study are missing answers to the question on coping strategies. The question may have been intentionally left unanswered or inadvertently overlooked, or that no coping strategies could be mentioned because nothing was experienced as helpful. Another possible explanation for this finding could be that the participants became tired of answering the question over the duration of the pandemic, in the sense of a lack of motivation. Besides, it should be mentioned that the sample of the TREND study might be selective with respect to well-educated and wealthy individuals. For example, many of our participants reported having their own garden or house, which provided them with free space during the pandemic. But the years of education did only show correlations with coping strategies lower than 0.07 (cf. Supplementary Tables S2–S7).

Methodologically, it should be noted that the coping strategies were recorded by means of a free-text field and using an open format question, rather than using an already established coping questionnaire. Nevertheless, the results of these surveys are unique, as data on coping strategies were collected at regular intervals over a period of 2.5 years, which extend the data pool of usual qualitative surveys (in our study, a total of 20,578 text segments in 4561 records, originating from more than 800 participants and collected at six time points over a 2.5-year period, were coded). The response rates over 2.5 years stayed between 83 and 90% and were exceptionally high for surveys. These constantly high rates prevent a severe bias towards healthy and resilient subjects, which is underlined by the fact that similar patterns of coping strategies emerged, even when all respondents were included, and analyses were not limited to subjects who participated in each of the six questionnaires. Society should be aware of helpful strategies, share them with older individuals and support and facilitate such strategies and activities, as the next pandemic and lockdowns might come.

In conclusion, the present findings provide novel insights into the longitudinal coping strategies of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, emotional-focused as well as problem-focused strategies were the main coping strategies, whereas general beliefs, general living conditions and the evaluation were mentioned less frequently. However, the current results so far do not allow a conclusion on how stable these strategies were for the individual.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The TREND study and all its amendments, including the questionnaires during the COVID-19 pandemic, were approved by the ethics committee at the Medical Faculty of the Eberhard Karls University and at the University Hospital of Tübingen (No. 90/2009BO2). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SH, DB, WM, KB, US, A-KT, TD, GE, and AT developed the research question, and contributed to the conception and study design. LK, CM, US, A-KT, SH, GE, and AT implemented the questionnaires. US programmed the database and online questionnaires. A-KT, US, and LK entered the data. US, LK, GE, and AT categorized the data in MAXQDA. LK and US contributed to drafting the text, designed the figures and tables, and performed the statistical analyses. All authors provided critical feedback and helped in every stage of the research, analysis, and manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The TREND study is being conducted at the University Hospital Tübingen and has been supported by the Hertie Institute for Clinical Brain Research, the DZNE, the Geriatric Center of Tübingen, the Center for Integrative Neuroscience. and partially funded in subprojects by the Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Union Chimique Belge, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the International Parkinson Foundation before 2017. Specifically, the CORO-TREND project of the TREND study was funded by the German Research Society (DFG, grant number: AOBJ: 675915, Project 458531848).

We thank the participants for their continued participation in the TREND study and the CORO-TREND project and for answering the questionnaires during the COVID-19 pandemic. We acknowledge the work of the numerous (doctoral) students and study nurses, who actively contributed to study organization, and data collection, entry, and monitoring. The (CORO-)TREND organization team consists of A-KT, US, LK, as well as the senior consultancy of CM, Inga Liepelt-Scarfone, and the operative controlling of Ramona Täglich, and Bettina Faust. We would also like to thank our federal volunteers Annika Weger, Sascha Koehler, Jakob Mickeler, Lisa Slédz, and Helen Alberth for their help with printing and mailing the questionnaires and with data entry.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1209021/full#supplementary-material

Abab, P., Haroon, S., O’Hara, M. E., and Jordan, R. E. (2022). Comorbidities and COVID-19. BMJ 377, 1–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o1431

AgeUK. Older people’s lives during the pandemic: age UK is listening and acting: AgeUK (2020) Available at: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/discover/2020/05/campaigning-coronavirus/

Anderson, M., and Perrin, A. (2017). Tech Adoption Climbs Among Older Adults, Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. United States of America. Available at: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/617864/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/1598740 (Accessed August 10, 2023).

Ayalon, L., Chasteen, A., Diehl, M., Levy, B., Neupert, S. D., Rothermund, K., et al. (2020). Aging in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity the journals of gerontology. Series B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 76, e49–e52. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa051

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., and Brown, G. K. (1987). Beck Depression Inventory. New York, USA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R., and Ranieri, W. F. (1996). Comparison of Beck depression inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. J. Pers. Assess. 67, 588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., and Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 4, 561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

Berg, D., Godau, J., Seppi, K., Behnke, S., Liepelt-Scarfone, I., Lerche, S., et al. (2013). The PRIPS study: screening battery for subjects at risk for Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 20, 102–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03798.x

Berg, D., Seppi, K., Liepelt, I., Schweitzer, K., Wollenweber, F., Wolf, B., et al. (2010). Enlarged hyperechogenic substantia nigra is related to motor performance and olfaction in the elderly. Mov. Disord. 25, 1464–1469. doi: 10.1002/mds.23114

Betsch, C., Korn, L., Felgendreff, L., Eitze, S., Schmid, P., Sprengholz, P., et al. (2020). German COVID-19 snapshot monitoring (COSMO) - Welle 16 (07.07.2020). PsyArXiv. 1–25.

Bhattacharjee, A., and Ghosh, T. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic and stress: coping with the new normal. J. Prevent. Health Promot 3, 30–52. doi: 10.1177/26320770211050058

Bonanad, C., Garcia-Blas, S., Tarazona-Santabalbina, F., Sanchis, J., Bertomeu- González, V., Fácila, L., et al. (2020). The effect of age on mortality in patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis with 611,583 subjects. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 915–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.045

Broda, M. (1990). “Anspruch und Wirklichkeit — Einige Überlegungen zum transaktionalen Copingmodell der Lazarus-Gruppe” in Krankheitsverarbeitung Berlin. ed. F. A. Muthny (Heidelberg: Springer)

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., and Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies a theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 267–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

Chen, L.-K. (2020). Older adults and COVID-19: resilience matters. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 89, 1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104124

Chen, Y., Röhr, S., Werle, B. M., and Romero-Ortuno, R. (2023). “Being a frail older person at a time of COVID-19 pandemic,” in Aging - From Fundamental Biology to Societal Impact Portugal. eds. P. J. Oliveira and J. O. Malva (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Elsevier).

Chmitorz, A., Wenzel, M., SR, D., Kunzler, A., Bagusat, C., Helmreich, I., et al. (2018). Population-based validation of a German version of the brief resilience scale. PLoS One 13:e0192761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192761

Dankowski, T., Kastner, L., Suenkel, U., von Thaler, K., Mychajliw, C., Krawczak, M., et al. (2023). Longitudinal dynamics of depression in risk groups of older individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in epidemiology, section neurological and mental health. Epidemiology 3:3. doi: 10.3389/fepid.2023.1093780

Feng, Y. S., Kohlmann, T., Janssen, M. F., and Buchholz, I. (2021). Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual. Life Res. 30, 647–673. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y

Finlay, J. M., Kler, J. S., O’Shea, B. Q., Eastman, M. R., Vinson, Y. R., and Kobayashi, L. C. (2021). Coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of older adults across the United States. Front. Public Health 9, 1–2. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.643807

Gaenslen, A., Wurster, I., Brockmann, K., Huber, H., Godau, J., Faust, B., et al. (2014). Prodromal features for Parkinson’s disease–baseline data from the TREND study. Eur. J. Neurol. 21, 766–772. doi: 10.1111/ene.12382

Gaertner, B., Fuchs, J., Möhler, R., Meyer, G., and Scheidt-Nave, C. (2021). Zur Situation älterer Menschen in der Anfangsphase der COVID-19 Pandemie: Ein Scoping Review. J. Health Monitoring 6, 1–39. doi: 10.25646/7856

Gierveld, J. D. J., and Tilburg, T. V. (2006). A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Aging 28, 582–598. doi: 10.1177/0164027506289723

Gilstrap, L., Zhou, W., Alsan, M., Nanda, A., and Skinner, J. S. (2022). Trend in mortality rates among medicare enrollees with Alzheimer disease and related dementias before and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic JAMA. Neurology 79, 342–348. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0010

Giordano, P. (2020). In Zeiten der Ansteckung: Wie die Corona-Pandemie unser Leben verändert. Hamburg, Germany: Rowohlt Verlag GmbH.

Greenwood-Hickman, M. A., Dahlquist, J., Cooper, J., Holden, E., McClure, J. B., Mettert, K. D., et al. (2021). “They’re going to zoom it”: a qualitative investigation of impacts and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic among older adults. Front. Public Health 9, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.679976

Halamová, J., Greškovičová, K., Baránkova, M., Stnádelová, B., and Krizova, K. (2022). There must be a way out: the consensual qualitative analysis of best coping practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.917048

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., and Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 42, 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Hautzinger, M., Bailer, M., Worall, H., and Keller, F. (1996). BDI Beck-Depressions-Inventar, Testhandbuch. Bern, Germany: Verlag Hans Hube.

Hautzinger, M., Keller, F., Kühner, C., and Beck, A. T. (2009). Beck Depressions-Inventar: BDI-II; Manual. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Pearson Assessment.

Herdman, M., Gudex, C., Lloyd, A., Janssen, M. F., Kind, P., Parkin, D., et al. (2011). Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 20, 1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

Herrera-Añazco, P., Urrunaga-Pastor, D., Benites-Zapata, V. A., Bendezu-Quispe, G., Toro-Huamanchumo, C. J., and Hernandez, A. V. (2022). Gender differences in depressive and anxiety symptoms during the first stage of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Latin America and the Caribbean. Front. Psych. 13, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.727034

Hussy, W., Schreier, M., Echterhoff, G., Hussy, W., Schreier, M., and Echterhoff, G. (2010). “Qualitative Analyseverfahren” in Forschungsmethoden in Psychologie und Sozialwissenschaften für. eds. W. Hussy, M. Schreier, and G. Echterhoff (Bachelor: Springer), 235–264.

Iswatun, I., Yusuf, A., Susanto, J., Makhfudli, M., Nasir, A., and Mardhika, A. D. (2022). Anxiety, coping strategies, quality of life of the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 11, 1501–1508. doi: 10.11591/ijphs.v11i4.21768

Johns-Hopkins-University. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) (2023) Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

Joseph, C. A., Kobayashi, L. C., Frain, L. N., and Finlay, J. M. (2023). “I can’t take any chances”: a mixed methods study of frailty, isolation, worry, and loneliness among aging adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Appl. Gerontol. 42, 789–799. doi: 10.1177/07334648221147918

Kim, L., Garg, S., O’Halloran, A., Whitaker, M., Pham, H., Anderson, E. J., et al. (2021). Risk factors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized adults identified through the US coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-associated hospitalization surveillance network (COVID-NET). Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, e206–e214. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1012

Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Dreier, M., Reinecke, L., Müller, K. W., Schmutzer, G., et al. (2016). The German version of the perceived stress scale - psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatr. 16, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9

Kompaniyets, L., Goodman, A. B., Belay, B., Freedman, D. S., Sucosky, M. S., Lange, S. J., et al. (2021a). Body mass index and risk for COVID-19-related hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, invasive mechanical ventilation, and death — United States, March–December 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 70, 355–361. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7010e4

Kompaniyets, L., Pennington, A. F., Goodman, A. B., Rosenblum, H. G., Belay, B., Ko, J. Y., et al. (2021b). Peer reviewed: underlying medical conditions and severe illness among 540,667 adults hospitalized wiith COVID-19, march 2020–march 2021. Prev. Chronic Dis. 18, 1–13. doi: 10.5888/pcd18.210123

Kumar, R., Singh, A., Mishra, R., Saraswati, U., and Bhalla, J. (2022). Pagali SARSotToPC, coping ways, and public support during the COVID-19 pandemic in the vulnerable populations in the United States. Front. Psych. 13, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.920581

Lazarus, R. S., and Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Lippi, G., and Henry, B. M. (2020). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Respir. Med. 167:105941. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105941

Luppa, M., Sikorski, C., Luck, T., Ehreke, L., Konnopka, A., Wiese, B., et al. (2012). Age-and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life–systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033

Mayring, P. (2020). “Qualitative inhalts analyse” in Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie Springer Fachmedien. eds. G. Mey and K. Mruck (Wiesbaden, Germany), 495–511.

Minahan, J., Falzarano, F., Yazdani, N., and Siedlecki, K. L. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and psychosocial outcomes across age through the stress and coping framework. Gerontologist 61, 228–239. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa205

Moreno, R., and Mayer, R. E. (1999). Gender differences in responding to open-ended problem-solving questions. Learn. Individ. Differ. 11, 355–364. doi: 10.1016/S1041-6080(99)80008-9

Mura, G., and Carta, M. G. (2013). Physical activity in depressed elderly. A systematic review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 9, 125–135. doi: 10.2174/1745017901309010125

Pearlin, L. I., and Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. J. Health Soc. Behav. 19, 2–21. doi: 10.2307/2136319

Peyer, K. L., Hathaway, E. D., and Doyle, K. (2022). Gender differences in stress, resilience, and physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 24, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2022.2052075

Promislow, D. E. L., and Anderson, R. (2020). A geroscience perspective on COVID-19 mortality. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 16, 30–33. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa094

Röhr, S., Reininghaus, U., and Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2020). Mental wellbeing in the German old age population largely unaltered during COVID-19 lockdown: results of a representative survey. BMC Geriatr. 20:489. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01889-x

Rosenthal, N., Cao, Z., Gundrum, J., and Sianis, J. S. S. (2020). Risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in a US national sample of patients with COVID-19. JAMA 3:e2029058. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29058

Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., and Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: a review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychol. Bull. 129, 216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216

State of Baden-Württemberg. (2023). Corona-Regulation of the State of Baden-Württemberg. Available at: https://www.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/service/aktuelle-infos-zu-corona/uebersicht-corona-verordnungen (Accessed October 8, 2023).

Subramanian, A., Nirantharakumar, K., Hughes, S., Myles, P., Williams, T., Gokhale, K. M., et al. (2022). Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat. Med. 28, 1706–1714. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01909-w

Thefeld, W., Stolzenberg, H., and Bellach, B. M. (1999). “Bundes-Gesundheitssurvey: Ergebnisse, Zusammensetzung der Teilnehmer und Non-Responder-Analyse,” in Der Bundesgesundheitssurvey: Erfahrungen, Ergebnisse, Perspektiven Vol 61. 55–61.

van den Besselaar, J. H., MacNeil Vroomen, J. L., Buurman, B. M., Hertogh, C. M. P. M., Huisman, M., Kok, A. A. L., et al. (2021). Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and perceived mastery in older adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. J. Psychosom. Res. 151:110656. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110656

VERBI-Software. (2021). MAXQDA 2022 [computer software]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software. Available at: maxqda.com

Whitehead, B. R., and Torossian, E. (2021). Older adults’ experience of the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods analysis of stresses and joys. Gerontologist 61, 36–47. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa126

Wu, Z., and McGoogan, J. M. (2020). Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 323, 1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648

Keywords: COVID-19, coping, Lazarus stress model, psychosocial factors, older adults

Citation: Kastner L, Suenkel U, Eschweiler GW, Dankowski T, von Thaler A-K, Mychajliw C, Brockmann K, Maetzler W, Berg D, Fallgatter AJ, Heinzel S and Thiel A (2023) Older adults’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic – a longitudinal mixed-methods study. Front. Psychol. 14:1209021. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1209021

Received: 21 April 2023; Accepted: 08 August 2023;

Published: 04 September 2023.

Edited by:

Mateusz Krystian Grajek, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, PolandReviewed by:

Selka Sadiković, University of Novi Sad, SerbiaCopyright © 2023 Kastner, Suenkel, Eschweiler, Dankowski, von Thaler, Mychajliw, Brockmann, Maetzler, Berg, Fallgatter, Heinzel and Thiel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lydia Kastner, bHlkaWEua2FzdG5lckB1bmktdHVlYmluZ2VuLmRl

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.