95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 06 July 2023

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1189194

It is established that personality traits contribute to life satisfaction but why they are connected are far less understood. This research report tested if self-rated health (SRH) which is one’s subjective ratings of their health and has a high predictivity of actual health mediates the associations between the Big Five model of personality and life satisfaction in a cohort (N = 5,845) of older adults from the UK. By using Pearson’s correlation analysis and mediation analysis, the current research reported positive correlations between Agreeableness, Openness, Conscientiousness, and Extraversion, SRH, and life satisfaction. However, Neuroticism was negatively correlated with SRH and life satisfaction. The main findings were that SRH partially mediates the associations between all traits in the Big Five and life satisfaction in older adults. This study began novel exploration on if SRH could explain the connections between the Big Five and life satisfaction. Results revealed SRH could partially explain these associations in all traits. These results may offer additional support to recently developed integrated account of life satisfaction, which argues that there are no single determinants of life satisfaction. Rather, life satisfaction is made up by many factors including but not limited to personality and health.

As the cognitive aspect of subjective well-being (SWB), life satisfaction refers to an individual’s overall subjective evaluation or perception of their own life as a whole. Understanding the contributing factors of life satisfaction can lead to a better comprehension of the broad sense of SWB (Schimmack et al., 2002). Indeed, in the past several decades, several theoretical models have been developed to account for life satisfaction mainly including the bottom-up (Headey et al., 2005; Diener, 2009; Erdogan et al., 2012; Loewe et al., 2014) and top-down (Headey et al., 2005; Diener, 2009; Erdogan et al., 2012; Loewe et al., 2014) model. Specifically, the bottom-up model suggests that life satisfaction is a sum of satisfaction of aspects of life including but not limited to satisfaction with health, income, and housing. The top-down perspective of life satisfaction proposes personality traits can decide life satisfaction. These two theories do not seem to be controversial but can be integrated. Indeed, during the past few years, empirical evidence seems to favor an integrated account of life satisfaction, which argues that life satisfaction is made up of satisfaction towards aspects of life and personality traits (Lachmann et al., 2017; Malvaso and Kang, 2022).

Thus, according to these theories, personality traits and health are all relevant to life satisfaction. The Big Five is a widely used inventory that measures personality traits including Openness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Neuroticism. The Big Five has been consistently found to be associated with health (Strickhouser et al., 2017) such as biological markers (Stephan et al., 2018a,b), mental health (Hakulinen et al., 2015a; Kang et al., 2023), risks of chronic conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (Terracciano et al., 2014) and mortality risk (Graham et al., 2017). Self-rated health (SRH) refers to the subjective rating of one’s own health, which is strongly predictive of actual healthy including risks of chronic disease, cognitive decline, dementia, and mortality (DeSalvo et al., 2006; Montlahuc et al., 2011; Latham and Peek, 2013; Bendayan et al., 2017).

Regarding the specific directions of the relationships between the Big Five, SRH, and life satisfaction, Neuroticism tends to be negatively related to SRH (Chapman et al., 2006; Löckenhoff et al., 2012; Turiano et al., 2012; Kööts-Ausmees et al., 2016; Mund and Neyer, 2016; Stephan et al., 2020). Openness (Löckenhoff et al., 2012; Stephan et al., 2020), Extraversion (Goodwin and Engstrom, 2002; Löckenhoff et al., 2012; Turiano et al., 2012; Stephan et al., 2020), and Conscientiousness (Löckenhoff et al., 2012; Turiano et al., 2012; Stephan et al., 2020; Kitayama and Park, 2021) tend to have a positive link to SRH although some studies did not find such a connection between Openness and SRH (Turiano et al., 2012; Kööts-Ausmees et al., 2016; Mund and Neyer, 2016; Stephan et al., 2020). The connection between Agreeableness and SRH remains still controversial (Löckenhoff et al., 2012; Turiano et al., 2012; Stephan et al., 2020). Similarly, literature generally found that Neuroticism has a negative relationship with life satisfaction whereas Agreeableness, Openness, Extraversion, and Conscientiousness have a positive connection to life satisfaction (e.g., Lachmann et al., 2017; Malvaso and Kang, 2022). Finally, SRH is strongly associated with life satisfaction regardless of country and age (e.g., Kööts-Ausmees and Realo, 2015; Atienza-González et al., 2020).

Given these pieces of evidence, there is good reason to believe that the Big Five personality traits may contribute to life satisfaction via SRH pathways. Indeed, personality traits can contribute to objective health such as sleep (Stephan et al., 2018a,b), physical activities (Sutin et al., 2016), and inflammation (Luchetti et al., 2014) and addictive behaviors (Kang, 2022a,b, 2023) that may ultimately affect health and are associated with SRH. Moreover, as speculated by prior studies (e.g., Lachmann et al., 2017; Malvaso and Kang, 2022), being healthy is one of the most important factors that people use to assess life satisfaction. Importantly, this may become a more critical factor in evaluating life satisfaction in older adults, who are experiencing a lot a more health issues that may interfere with their daily life than their younger counterparts.

Thus, the current research report aimed to investigate if the Big Five are related to life satisfaction via SRH pathway in older adults. The current research hypothesizes that SRH meditates the relationships between the Big Five and life satisfaction.

Wave 3 data from Understanding Society: the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS) were collected between 2010 and 2011 and were selected for this study (University of Essex, 2022). Please refer to https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk for more information. Wave 3 was used because only Wave 3 contains assessments of all main variables of interest. Data collections have been approved by the University of Essex Ethics Committee. People who were younger than 65 years old or have missing variables were removed, which resulted in a sample of 5,845 older adults.

UKHLS Wave 3 used the 15-item version of the Big Five, which has been shown to be a valid version to measure the Big Five with good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hahn et al., 2012; Soto and John, 2017). Please refer to Supplementary material for a complete set of these questions. A Likert scale ranging from 1 (“disagree strongly”) to 5 (“agree strongly”) were used to score these responses. This study reverse-coded some of scores when appropriate.

SRH was captured by the question “In general, would you say your health is…” using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (excellent) to 5 (very poor). Responses from this question were reversed coded so a higher score reflects better health. The reliability of it is high (e.g., Lundberg and Manderbacka, 1996).

Life satisfaction was measured by the question “How dissatisfied or satisfied are you with… your life overall?” Participants answered this question with a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 7 (completely satisfied). The results of single-item measure are pretty similar to multi-item inventories such as the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Cheung and Lucas, 2014).

Age, sex, income (monthly), education, and marital status were included as study control variables. The coding of these can be found in Table 1.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) were first calculated between personality traits including Agreeableness, Openness, Extraversion, Neuroticism, and Conscientiousness, SRH, and life satisfaction. Mediation analysis is a statistical method used to examine the mediating effect of a variable in explaining the relationship between two other variables. It aims to determine whether and how much of the relationship between an independent variable (X) and a dependent variable (Y) can be explained by the influence of a mediator variable (Baron and Kenny, 1986). Mediation analyses were conducted using the mediation toolbox on MATLAB 2018a by setting personality traits as the independent variables, SRH as the mediator, and life satisfaction as the dependent variable with 10,000 bootstrap sample significance testing with study control variables as covariates.1

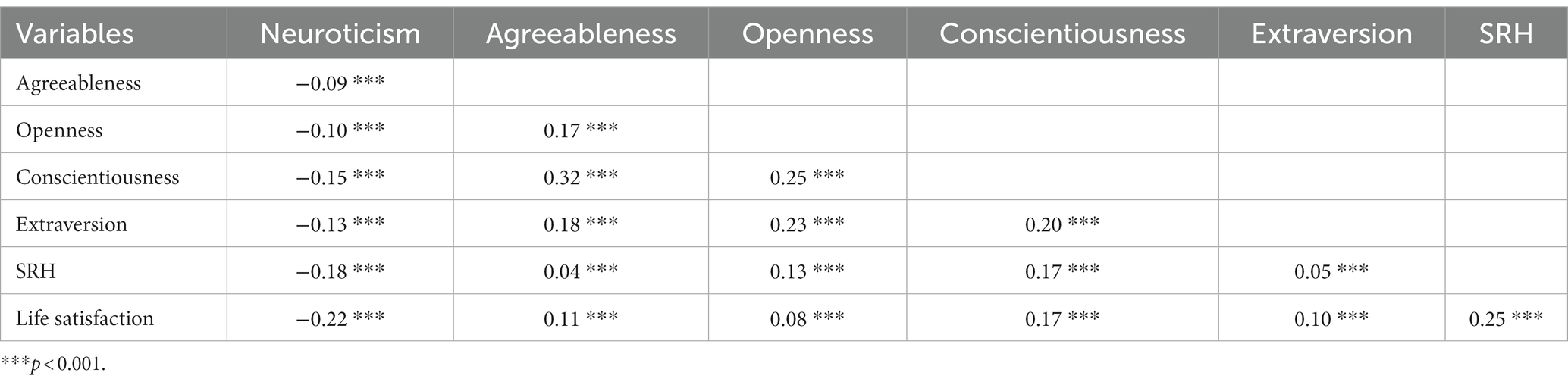

Descriptive statistics were demonstrated in Table 1. Pearson’s correlation revealed that Neuroticism is negatively correlated with SRH [r = −0.18, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (−0.21, −0.16)] and life satisfaction [r = −0.22, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (−0.25, −0.19)]. Agreeableness had correlations with SRH [r = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.01, 0.06)] and life satisfaction [r = 0.11, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.09, 0.14)]. The correlations between Openness and SRH [r = 0.13, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.11, 0.16)] and life satisfaction [r = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.06, 0.11)] were positive. Conscientiousness was positively correlated with SRH [r = 0.17, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.14, 0.19)] and life satisfaction [r = 0.17, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.14, 0.19)]. Extraversion had positive associations with SRH [r = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.03, 0.08)] and life satisfaction [r = 0.10, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.08, 0.12)]. Finally, SRH was positively correlated with life satisfaction [r = 0.25, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.23, 0.27)] (see Table 2).

Table 2. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) between Neuroticism, Agreeableness, Openness, Conscientiousness, SRH, and life satisfaction.

Mediation analysis found that SRH partially mediated the relationship between Neuroticism [mediation effect: b = −0.04, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (−0.04, −0.04); direct effect: b = −0.18, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (−0.19, −0.17)], Agreeableness [mediation effect: b = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.02, 0.02); direct effect: b = 0.15, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.14, 0.16)], Openness [mediation effect: b = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.02, 0.03); direct effect: b = 0.05, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.04, 0.06)], Conscientiousness [mediation effect: b = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. [0.04, 0.05]; direct effect: b = 0.16, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.15, 0.17)] and Extraversion [mediation effect: b = 0.01, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.01, 0.02); direct effect: b = 0.09, p < 0.001, 95% C.I. (0.08, 0.10)]. The complete results were demonstrated in Table 3 and Figure 1.

Table 3. The median analysis results for A. Neuroticism, B. Agreeableness, C. Openness, D. Conscientiousness, and E. Extraversion.

Figure 1. The path diagram for (A) Neuroticism, (B) Agreeableness, (C) Openness, (D) Conscientiousness, and (E) Extraversion. Standardized coefficients are included in the parenthesis.

This research report sought to test whether SRH mediates the associations between the Big Five and life satisfaction in older adults. Results provided novel findings that SRH partially mediates all the associations between the Big Five and life satisfaction.

The finding that SRH mediates the relationship between Neuroticism and life satisfaction is totally explainable given that Neuroticism is tendency to experience negative emotions, which is associated with affective disorder (Hakulinen et al., 2015a) and other chronic diseases including dementia (Terracciano et al., 2014) and chronic respiratory diseases (Terracciano et al., 2017). In addition, Neuroticism is positively connected with addictive behaviors such as use of cigarette (Hakulinen et al., 2015b) and alcohol (Luchetti et al., 2018). Finally, Neuroticism is related to other aspects of health including a slower speed of walking (e.g., Stephan et al., 2018a,b) and biological dysfunctions (Sutin et al., 2019). Thus, Neuroticism may contribute to worse SRH and thus less life satisfaction.

SRH served as a significant mediator in the associations between Agreeableness and life satisfaction, Openness and life satisfaction, and Extraversion and life satisfaction. Agreeableness is positively connected to overall health (Strickhouser et al., 2017). Additionally, behaviors that benefit health including more physical activities (Artese et al., 2017), fewer addictive behaviors (Luchetti et al., 2018), and better adherence to medicine (Axelsson et al., 2011). High Openness is related to a higher level of physical activities (Sutin et al., 2016) and physical function (Stephan et al., 2018a,b) but yet a lower rate of inflammation (Luchetti et al., 2014). Extraversion is also associated with health-promoting behaviors such as more physically activities (Sutin et al., 2016; Kroencke et al., 2019), better quality of sleep (Stephan et al., 2018a,b), and better mental health (Hakulinen et al., 2015a). Furthermore, people with high Extraversion also have better objective health including a higher aerobic capacity (Terracciano et al., 2013) and better physical functions (Stephan et al., 2018a,b). Thus, high Agreeableness, Openness, and Extraversion scores may contribute to a better SRH and thus higher life satisfaction.

SRH was also a significant mediator in the connection between Conscientiousness and life satisfaction. There are positive relationships between Conscientiousness and health-promoting including physical activities (Sutin et al., 2016; Kroencke et al., 2019). However, there are also negative associations between Conscientiousness and addictive behaviors including use of alcohol (Hakulinen et al., 2015b), drug (Kang, 2022a), and cigarette (Luchetti et al., 2018; Kang, 2022b). In addition, Conscientiousness has negative relationship with chronic diseases (Weston et al., 2015) such as obesity (Jokela et al., 2013). Moreover, Conscientiousness is associated with better objective health including better lung function, more grip strength, and a faster speed of walking (e.g., Sutin et al., 2018). Finally, Conscientiousness is also linked to health marker such as metabolic, inflammatory, and cardiovascular markers (Luchetti et al., 2014; Sutin et al., 2018). Therefore, high Conscientiousness scores may contribute to a better SRH and thus higher life satisfaction.

However, all the mediations found in the current study were partial mediation and the coefficients were small, which indicates that health cannot fully explain why personality traits are associated with life satisfaction. For instance, as pointed out by Malvaso and Kang (2022), life satisfaction can also be explained by aspects including household incomes, housing, job, spouse/partner, social life, leisure time. Moreover, studies have found that personality are also related to these factors that contribute to overall life satisfaction such as social support (e.g., Yu et al., 2021). Thus, further studies on how these factors may mediate the associations between the Big Five and life satisfaction can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying basis of why personality traits are related to life satisfaction. In addition, another weakness of the current research is its cross-sectional and self-reported and there is no clinical assessment of health, which may be biased. Finally, these data were quite old, which may limit its implications for today. Future studies could address these limits by including multiple mediators and using objective measurements and longitudinal designs.

In conclusion, SRH partially explained the relationship between the Big Five and life satisfaction on a large cohort of older adults from the UK. This study began novel exploration on if SRH could explain the connections between the Big Five and life satisfaction. Results revealed SRH could partially explain these associations in all traits. These results may offer additional support to recently developed integrated account of life satisfaction, which argues that there are no single determinants of life satisfaction. Rather, life satisfaction is made up by many factors including but not limited to personality and health (Malvaso and Kang, 2022).

The findings of this study have practical implications for interventions aimed at enhancing life satisfaction in older adults. Firstly, targeted health interventions focusing on improving self-rated health (SRH) may positively impact life satisfaction. Encouraging physical activities, reducing addictive behaviors, and improving medication adherence could be valuable strategies. Secondly, considering the influence of personality traits on SRH and life satisfaction, interventions that foster traits including Agreeableness, Openness, Conscientiousness, and Extraversion but reduce Neuroticism may have a positive effect. Lastly, a comprehensive approach that acknowledges the multidimensional nature of life satisfaction, including personality, health, and other life domains such as income, housing, and social support, is crucial for promoting overall well-being in older adults. By incorporating these strategies, practitioners and policymakers can design interventions that address the complex interplay of factors contributing to life satisfaction in this population.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Essex. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

WK: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software, supervision, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. AM: writing—original draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1189194/full#supplementary-material

Artese, A., Ehley, D., Sutin, A. R., and Terracciano, A. (2017). Personality and actigraphy-measured physical activity in older adults. Psychol. Aging 32, 131–138. doi: 10.1037/pag0000158

Atienza-González, F. L., Martínez, N., and Silva, C. (2020). Life satisfaction and self-rated health in adolescents: the relationships between them and the role of gender and age. Span. J. Psychol. 23:e4. doi: 10.1017/SJP.2020.10

Axelsson, M., Brink, E., Lundgren, J., and Lötvall, J. (2011). The influence of personality traits on reported adherence to medication in individuals with chronic disease: an epidemiological study in West Sweden. PLoS One 6:e18241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018241

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bendayan, R., Piccinin, A. M., Hofer, S. M., and Muniz, G. (2017). Are changes in self-rated health associated with memory decline in older adults? J. Aging Health 29, 1410–1423. doi: 10.1177/0898264316661830

Chapman, B. P., Duberstein, P. R., Sörensen, S., and Lyness, J. M. (2006). Personality and perceived health in older adults: the five factor model in primary care. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 61, P362–P365. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.6.P362

Cheung, F., and Lucas, R. E. (2014). Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: results from three large samples. Qual. Life Res. 23, 2809–2818. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4

DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K., He, J., and Muntner, P. (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question: a meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 21, 267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x

Diener, E. (2009). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 55, 11–58. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2350-6_2

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., and Mansfield, L. R. (2012). Whistle while you work: a review of the life satisfaction literature. J. Manag. 38, 1038–1083. doi: 10.1177/0149206311429379

Goodwin, R., and Engstrom, G. (2002). Personality and the perception of health in the general population. Psychol. Med. 32, 325–332.

Graham, E. K., Rutsohn, J. P., Turiano, N. A., Bendayan, R., Batterham, P. J., Gerstorf, D., et al. (2017). Personality predicts mortality risk: an integrative data analysis of 15 international longitudinal studies. J. Res. Pers. 70, 174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2017.07.005

Hahn, E., Gottschling, J., and Spinath, F. M. (2012). Short measurements of personality–validity and reliability of the GSOEP big five inventory (BFI-S). J. Res. Pers. 46, 355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.03.008

Hakulinen, C., Elovainio, M., Pulkki-Råback, L., Virtanen, M., Kivimäki, M., and Jokela, M. (2015a). Personality and depressive symptoms: individual participant meta-analysis of 10 cohort studies. Depress. Anxiety 32, 461–470. doi: 10.1002/da.22376

Hakulinen, C., Hintsanen, M., Munafò, M. R., Virtanen, M., Kivimäki, M., Batty, G. D., et al. (2015b). Personality and smoking: individual-participant meta-analysis of nine cohort studies. Addiction 110, 1844–1852. doi: 10.1111/add.13079

Headey, B., Veenhoven, R., and Weari, A. (2005). “Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being” in Citation classics from social indicators research (Dordrecht: Springer), 401–420.

Jokela, M., Hintsanen, M., Hakulinen, C., Batty, G. D., Nabi, H., Singh-Manoux, A., et al. (2013). Association of personality with the development and persistence of obesity: a meta-analysis based on individual–participant data. Obes. Rev. 14, 315–323. doi: 10.1111/obr.12007

Kang, W. (2022a). Big five personality traits predict illegal drug use in young people. Acta Psychol. 231:103794. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103794

Kang, W. (2022b). Personality predicts smoking frequency: An empirical examination separated by sex. Personal. Individ. Differ. 199:111843. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2022.111843

Kang, W. (2023). Understanding the associations between personality traits and the frequency of alcohol intoxication in young males and females: findings from the United Kingdom. Acta Psychol. 234:103865. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2023.103865

Kang, W., Steffens, F., Pineda, S., Widuch, K., and Malvaso, A. (2023). Personality traits and dimensions of mental health. Sci. Rep. 13:7091

Kitayama, S., and Park, J. (2021). Is conscientiousness always associated with better health? A US–Japan cross-cultural examination of biological health risk. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 47, 486–498.

Kööts-Ausmees, L., and Realo, A. (2015). The association between life satisfaction and self–reported health status in Europe. Eur. J. Personal. 29, 647–657. doi: 10.1002/per.2037

Kööts-Ausmees, L., Schmidt, M., Esko, T., Metspalu, A., Allik, J., and Realo, A. (2016). The role of the five–factor personality traits in general self–rated health. Eur. J. Personal. 30, 492–504. doi: 10.1002/per.2058

Kroencke, L., Harari, G. M., Katana, M., and Gosling, S. D. (2019). Personality trait predictors and mental well-being correlates of exercise frequency across the academic semester. Soc. Sci. Med. 236:112400. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112400

Lachmann, B., Sariyska, R., Kannen, C., Błaszkiewicz, K., Trendafilov, B., Andone, I., et al. (2017). Contributing to overall life satisfaction: personality traits versus life satisfaction variables revisited—is replication impossible? Behavioral sciences 8:1. doi: 10.3390/bs8010001

Latham, K., and Peek, C. W. (2013). Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife US adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 68, 107–116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs104

Löckenhoff, C. E., Terracciano, A., Ferrucci, L., and Costa, P. T. Jr. (2012). Five-factor personality traits and age trajectories of self-rated health: the role of question framing. J. Pers. 80, 375–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00724.x

Loewe, N., Bagherzadeh, M., Araya-Castillo, L., Thieme, C., and Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2014). Life domain satisfactions as predictors of overall life satisfaction among workers: evidence from Chile. Soc. Indic. Res. 118, 71–86. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0408-6

Luchetti, M., Barkley, J. M., Stephan, Y., Terracciano, A., and Sutin, A. R. (2014). Five-factor model personality traits and inflammatory markers: new data and a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 50, 181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.08.014

Luchetti, M., Sutin, A. R., Delitala, A., Stephan, Y., Fiorillo, E., Marongiu, M., et al. (2018). Personality traits and facets linked with self-reported alcohol consumption and biomarkers of liver health. Addict. Behav. 82, 135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.034

Lundberg, O., and Manderbacka, K. (1996). Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand. J. Soc. Med. 24, 218–224. doi: 10.1177/140349489602400314

Malvaso, A., and Kang, W. (2022). The relationship between areas of life satisfaction, personality, and overall life satisfaction: An integrated account. Front. Psychol. 13:894610. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.894610

Montlahuc, C., Soumare, A., Dufouil, C., Berr, C., Dartigues, J. F., Poncet, M., et al. (2011). Self-rated health and risk of incident dementia: a community-based elderly cohort, the 3C study. Neurology 77, 1457–1464. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823303e1

Mund, M., and Neyer, F. J. (2016). The winding paths of the lonesome cowboy: evidence for mutual influences between personality, subjective health, and loneliness. J. Pers. 84, 646–657. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12188

Schimmack, U., Radhakrishnan, P., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., and Ahadi, S. (2002). Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: integrating process models of life satisfaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 582–593. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.4.582

Soto, C. J., and John, O. P. (2017). The next big five inventory (BFI-2): developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 113, 117–143. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000096

Stephan, Y., Sutin, A. R., Bayard, S., Križan, Z., and Terracciano, A. (2018a). Personality and sleep quality: evidence from four prospective studies. Health Psychol. 37, 271–281. doi: 10.1037/hea0000577

Stephan, Y., Sutin, A. R., Bovier-Lapierre, G., and Terracciano, A. (2018b). Personality and walking speed across adulthood: prospective evidence from five samples. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 9, 773–780. doi: 10.1177/1948550617725152

Stephan, Y., Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Hognon, L., Canada, B., and Terracciano, A. (2020). Personality and self-rated health across eight cohort studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 263:113245. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113245

Strickhouser, J. E., Zell, E., and Krizan, Z. (2017). Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychol. 36, 797–810. doi: 10.1037/hea0000475

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Luchetti, M., Artese, A., Oshio, A., and Terracciano, A. (2016). The five-factor model of personality and physical inactivity: a meta-analysis of 16 samples. J. Res. Pers. 63, 22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.05.001

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., and Terracciano, A. (2018). Facets of conscientiousness and objective markers of health status. Psychol. Health 33, 1100–1115. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2018.1464165

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., and Terracciano, A. (2019). Personality and metabolic dysfunction in young adulthood: a cross-sectional study. J. Health Psychol. 24, 495–501. doi: 10.1177/1359105316677294

Terracciano, A., Schrack, J. A., Sutin, A. R., Chan, W., Simonsick, E. M., and Ferrucci, L. (2013). Personality, metabolic rate and aerobic capacity. PLoS One 8:e54746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054746

Terracciano, A., Stephan, Y., Luchetti, M., Gonzalez-Rothi, R., and Sutin, A. R. (2017). Personality and lung function in older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 72, 913–921. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv161

Terracciano, A., Sutin, A. R., An, Y., O'Brien, R. J., Ferrucci, L., Zonderman, A. B., et al. (2014). Personality and risk of Alzheimer's disease: new data and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement. 10, 179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.002

Turiano, N. A., Pitzer, L., Armour, C., Karlamangla, A., Ryff, C. D., and Mroczek, D. K. (2012). Personality trait level and change as predictors of health outcomes: findings from a national study of Americans (MIDUS). J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 67, 4–12. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr072

University of Essex. (2022). Institute for social and economic research. Understanding society: waves 1–11, 2009–2020 and harmonised BHPS: Waves 1–18, 1991–2009. [data collection]. 15th edition. UK data service. SN: 6614.

Weston, S. J., Hill, P. L., and Jackson, J. J. (2015). Personality traits predict the onset of disease. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6, 309–317. doi: 10.1177/1948550614553248

Keywords: personality, self-rated health, life satisfaction, mediation, older adults

Citation: Kang W and Malvaso A (2023) Self-rated health (SRH) partially mediates and associations between personality traits and life satisfaction in older adults. Front. Psychol. 14:1189194. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1189194

Received: 18 March 2023; Accepted: 25 May 2023;

Published: 06 July 2023.

Edited by:

Atsushi Oshio, Waseda University, JapanReviewed by:

Maria Rita Sergi, University of G.'d'Annunzio, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Kang and Malvaso. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weixi Kang, d2VpeGkyMGthbmdAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.