95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Psychol. , 18 May 2023

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1144087

This article is part of the Research Topic Long-term Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Sleep and their Relationships with Mental Health View all 5 articles

Giada Rapelli1*

Giada Rapelli1* Giorgia Varallo1

Giorgia Varallo1 Serena Scarpelli2

Serena Scarpelli2 Giada Pietrabissa3,4

Giada Pietrabissa3,4 Alessandro Musetti5

Alessandro Musetti5 Giuseppe Plazzi6,7

Giuseppe Plazzi6,7 Christian Franceschini1

Christian Franceschini1 Gianluca Castelnuovo3,4

Gianluca Castelnuovo3,4Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic caused several psychological consequences for the general population. In particular, long-term and persistent psychopathological detriments were observed in those who were infected by acute forms of the virus and need specialistic care in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT) has shown promising results in managing nightmares of patients with different traumas, but it has never been used with patients admitted to ICUs for severe COVID-19 despite this experience being considered traumatic in the literature.

Methods: The purpose of this case study is to describe the application of a four-session IRT for the treatment of COVID-related nightmares in a female patient after admission to the ICU. A 42-year-old Caucasian woman who recovered from a pulmonary rehabilitation program reported shortness of breath, dyspnea, and everyday life difficulties triggered by the long-COVID syndrome. She showed COVID-related nightmares and signs of post-traumatic symptoms (i.e., hyperarousal, nightmares, and avoidance of triggers associated with the traumatic situation). Psychological changes in the aftermath of a trauma, presence, and intensity of daytime sleepiness, dream activity, sleep disturbances, aspects of sleep and dreams, and symptoms of common mental health status are assessed as outcomes at the baseline (during the admission to pneumology rehabilitation) at 1-month (T1) and 3-month follow-up (T2). Follow-up data were collected through an online survey.

Results: By using IRT principles and techniques, the patient reported a decrease in the intensity and frequency of bad nightmares, an increase in the quality of sleep, and post-traumatic growth, developing a positive post-discharge.

Conclusion: Imagery rehearsal therapy may be effective for COVID-19-related nightmares and in increasing the quality of sleep among patients admitted to the ICU for the treatment of COVID-19. Furthermore, IRT could be useful for its brevity in hospital settings.

The COVID-19 pandemic and confinement measures are established adverse events increasing the risk of anxiety, fear of contagion, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Giusti et al., 2020, 2022; Rapelli et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Pietrabissa et al., 2021). Changes in daily routine and work schedule also caused alterations in the sleep–wake cycle and decreased sleep quality (Franceschini et al., 2020). Insomnia, hypersomnia, and nightmares were frequently observed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Borghi et al., 2021; Margherita et al., 2021; Scarpelli et al., 2022a) and, especially during the second wave, people presenting with more nightmares also showed greater sleep problems and higher levels of PTSD (Scarpelli et al., 2021).

Individuals suffering from COVID-19 post-acute symptoms reported greater sleep alterations and more frequent nightmares than individuals with “short-COVID” (Scarpelli et al., 2022b). Furthermore, patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) (e.g., patients intubated and mechanically ventilated due to respiratory failure) were at higher risk of experiencing PTSD symptoms including intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, arousal, and reactivity (Nagarajan et al., 2022); in fact, ICU represented additional extreme stressors for patients with COVID-19, who could feel fear of death, pain from medical procedures such as endotracheal intubation, limited ability to communicate, feelings of loss of control, mood swings, sleep disturbance, and feelings of panic and suffocation (Kaseda and Levine, 2020).

Acute phase survivors of severe COVID-19 treated in the ICU were more likely to experience poor sleep quality characterized by wakefulness, a high proportion of time spent in shallow sleep, and a relatively low proportion of time spent in REM sleep, as well as vivid nightmares and hallucinations (Helms et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2020). This could impact their recovery process in the long-term (e.g., post-intensive care syndrome and long-COVID syndrome) from 20 days after the ICU discharge (Weidman et al., 2022) to 3-month follow-up (Rousseau et al., 2021) and persist even after 1 year from discharge (Kaseda and Levine, 2020).

One year after admission to an ICU, patients tend to develop a worse health-related quality of life, persistent dyspnea, and impairment in pulmonary function (Gamberini et al., 2021). ICU might, therefore, be considered a potential high-trauma experience for patients with COVID-19 (Beck et al., 2021; Janiri et al., 2021), and its consequences deserve appropriate attention. In this respect, imagery rehearsal therapy (IRT; Kellner et al., 1992), a third-generation cognitive-behavioral technique, has shown promising results in reducing the number and intensity of nightmares in patients who experienced different types of traumas (Krakow and Zadra, 2006; Pierpaoli-Parker et al., 2021; Poschmann et al., 2021) and only partially in ICU patients (Szabó and Tóth, 2021). It works by elaborating on the original nightmare and providing a cognitive shift that empirically refutes the original premise of the nightmare (Lancee et al., 2011; Germain, 2013). To date, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the efficacy of IRT in the treatment of trauma-related experiences of COVID-19.

The purpose of this case study is to describe the implementation of four-session IRT for the treatment of a female patient previously admitted for a 3-week ICU treatment following COVID-19 and showing trauma-related nightmares 9 months after admission. Furthermore, this case study intends to illustrate for the first time how IRT’s skills and strategies can be used for the treatment of post-traumatic nightmares after admission to an ICU for COVID-19.

CARE guidelines (Case Report; Gagnier et al., 2013) for writing a patient case report in a checklist were used to enhance the manuscript process (see Supplementary data sheet 2).

Grace (pseudonym) was admitted to the 1-month of a pulmonary rehabilitation program with complaints of shortness of breath, dyspnea, and everyday life difficulties triggered by long-COVID syndrome (she received the diagnosis of COVID-19 9 months earlier), which also caused her significant weight gain due to sedentariness (current body mass index, BMI = 29.8 kg/m2). She was a 42-year-old woman living in Central Italy. She worked as an employee, was married, and had two children (a 12-year-old girl and a 7-year-old boy). During the initial assessment phase, no particular stressful family, couple, or work situations emerged. During the present hospitalization, Grace received a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) and received continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy with benefits. Grace reported using CPAP regularly during the initial adjustment in the hospital. Still, she continued to experience sleep disturbances and daily nightmares once a day (intrusive thoughts/memories pertained to the doctors’ communication that she would be intubated in ICU because her condition worsened after contracting the virus).

For this reason, the patient asked for psychological support. No pharmacological treatment was used. Ethical approval of the study was obtained by the Medical Ethics Committee of the IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano (ID: 2021_03_23_02). All procedures performed in the study were run following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Before the study, the interviewer informed the participant about the aim and procedure of the interview and intervention and obtained her signed informed consent and permission to audio-record the session for research purposes (see Supplementary data sheet 1).

It is to be noted as an unanticipated event that, at the final debriefing with the psychologist following the last survey (T2), Grace reported a stressful situation in the family that led to her decision to separate from her husband. The husband and the wife in the last survey were separated at home.

A trained psychologist (GR) conducted a face-to-face semi-structured interview with the patient during the first week of pulmonary rehabilitation in order to explore the deep experience of Grace in the ICU.

The semi-structured interview occurred in a dedicated room of the hospital, lasted for about 1 h, and, during the interview, Grace was asked about the experience of being infected and the experience of the ICU, feelings and worries about COVID-19 management during the hospitalization and at home, feelings about COVID-19 consequences during hospitalization and at home after discharge, and the frequent nightmares related to the experience in ICU.

A storytelling approach with probing questions (e.g., “tell me more about that experience” and “how did that make you feel?”) was further used during the interview to clarify or expand meanings presented by the patient, thus facilitating a dialogic interaction process and to help to express deepest thoughts and feelings as freely as possible.

Selected psychological outcomes were collected at the beginning (Baseline – T0) and termination of the IRT intervention through self-reported measures (see Table 1) and at 1-month (T1) and 3-month follow-up (T2). Follow-up data were collected through an online survey. After T2, the psychologist who managed the intervention and Grace met in an online meeting to get feedback on her emotional, psychological, and sleep-related state.

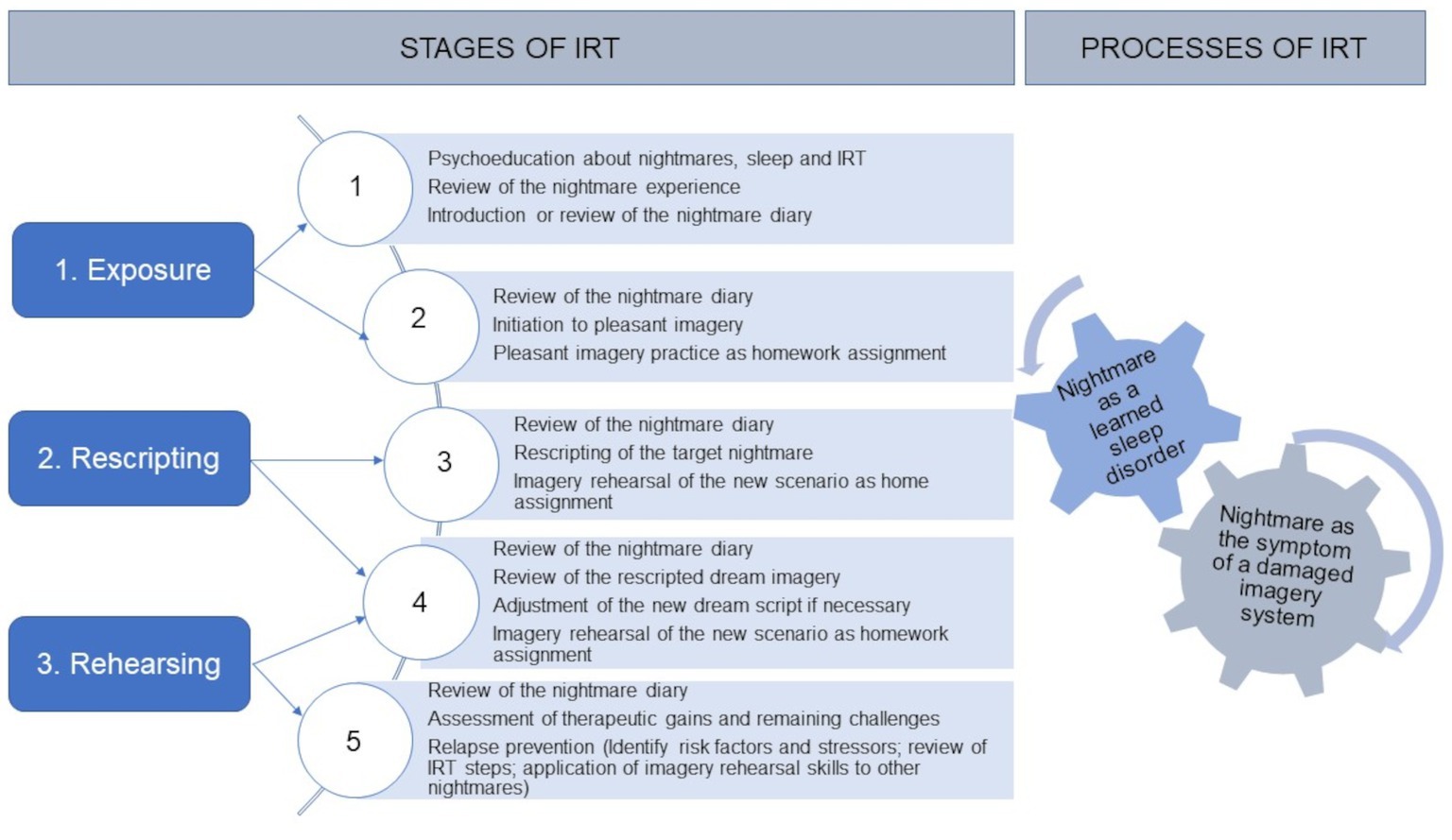

Figure 1 shows the identified stages and process of IRT. Table 2 describes the IRT intervention.

Figure 1. Stages and process of IRT. Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT) is a brief evidence-based cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) technique developed by Kellner et al. (1992), which is effective in reducing nightmare distress and nightmares frequency, including PTSD-related forms of nightmares, and maintaining changes in long-term follow-up (Kunze et al., 2016; Ellis et al., 2019; Lancee et al., 2021). It works by inhibiting the original nightmare and providing a cognitive shift that empirically refutes the original premise of the nightmare (Lancee et al., 2011; Germain, 2013). Many non-pharmacologic techniques have been proposed to treat PTSD-related or idiopathic nightmares, including hypnosis, lucid dreaming, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, desensitization, and IRT. However, only desensitization and IRT have been the object of controlled studies, and IRT has received the most empirical support (Krakow and Zadra, 2010). This method seems to have a beneficial effect on PTSD symptoms, the quality of sleep, and the nightmare frequency (Van Schagen et al., 2015; Van Schagen and Lancee, 2018).

Table 3 shows the results of the IRT-based psychological intervention between the three waves and the changes in the patient with respect to psychological and sleep-related variables.

Furthermore, intervention sessions faithfully followed the IRT reference manuals (Kellner et al., 1992), and regular supervision sessions were conducted between the psychologist and experts in IRT (CF and SS) to ensure treatment fidelity.

The total score of PTG increased from the baseline to follow-ups. According to Mazor et al. (2016), scores of 45 and below represented none to low PTG levels, whereas scores of 46 and above-represented medium to very high PTG levels. Before the treatment, Grace reported low levels of PTG; at the end of the treatment, and 4 months later, she showed high levels of PTG referring to the cutoff point of the scale. Furthermore, analyzing the five dimensions of PTGI, the patient showed an increase in value from the baseline to follow-ups in relating to others, new possibilities, appreciation of life, and spiritual change. Regarding the dimension of personal strength, Grace showed an increase in the long term, but the change was smaller than in previous subscales. Because there are no studies to our knowledge with respect to subdimension cutoffs, we cannot make assumptions regarding the minimal clinical difference.

Regarding the daytime sleepiness measured with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), the patient showed a higher normal daytime sleepiness in the baseline according to the scale range of the ESS; the score was higher at the end of the treatment, showing mild excessive daytime sleepiness and the daytime sleepiness at T2 returned higher normal also. Hence, daytime sleepiness showed no trend over the course of the study. It should be reiterated that the patient was being treated for OSAS and was following CPAP therapy at the time of treatment.

Sleep quality was measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). In terms of self-reported sleep quality (i.e., scores at PSQI), the total PSQI score at the baseline was 12, with a cutoff of ≥5 indicating sleep disorders. Interestingly, the total PSQI decreased from the baseline in both follow-ups, meeting the minimal clinically important difference of ≥3 as suggested by previous evidence (Hughes et al., 2009; Eadie et al., 2013; McDonnell et al., 2014; Weinberg et al., 2020). In fact, a change of three points or more was chosen to indicate the smallest amount of change in PSQI that might be considered important by the patient according to the literature also considering the short-term assessment.

Sleep efficiency was measured with the sleep and dreams diary at T0 and T1, and it had a range from 93 to 63%, and there was no clear trend of improvement. Normal sleep efficiency is considered to be 85% or greater, and the patient thus appeared to show a wide range of variability (Miller et al., 2014), suggesting no normal sleep efficiency.

Scores on the item related to the emotional intensity of dreams decreased at T1 and T2 (2 = rather intense dreams) compared to T0 (4 = very intense), while the emotional intensity remained unchanged with a score of 0 indicating a neutral tone. Moreover, the nightmare frequency at T0 was 6 (indicating a nightmare once a week), and at T1 and T2 was 4 (indicating a nightmare once a month). Despite the reduction in frequency, the emotional distress associated with the nightmare remained stable (i.e., quite distressing).

Grace did not show improvement in stress, anxiety, and depression measured with DASS. In particular, the stress level showed a rising trend from the baseline to follow-ups and, as compared to the clinical cutoff point, the levels of stress were low in all three assessments; the anxiety showed a non-linear variation, and it was higher in T2 after 4 months from the beginning of treatment but always behind the clinical cutoff point. Moreover, for depression, there was an increasing trend from the baseline to follow-ups, but the levels were behind the clinical cutoff points in all the measurements.

Cognitive-behavioral treatments such as IRT have successfully reduced nightmare frequency, PTSD severity, and other mental health issues, such as depressive symptoms, while improving sleep quality (Ellis et al., 2019; Gieselmann et al., 2019). To date, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the efficacy of IRT either in the treatment of trauma-related experiences of COVID-19 or in patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICU. For these reasons, an IRT-based intervention protocol was conceptualized and administered to a patient with COVID-19-related nightmares and symptoms of PTSD linked to the experience of being admitted to the ICU 9 months after the traumatic event.

A preliminary semi-structured interview revealed anxiety and guilt over the possibility of having infected someone to be her first emotional reaction to the COVID-19 diagnosis. Furthermore, the need to be intubated and the risk of death shocked Grace to the point that it was difficult for the patient to describe her emotions. However, she was not the only one affected by this event as also her family struggled with this news and had to establish a new routine after the patient was discharged from the hospital. Nonetheless, the patient was able to find the silver lining in this traumatic experience and reported that exposure to a life-threatening illness reawakened her will to live. In fact, in addition to the difficulties people face as a result of traumatic events, a growing body of research indicates they might also experience positive life changes (Schaefer and Moos, 1992; Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995). These experiences can be associated with the discovery of new coping strategies and personal and environmental resources in response to adverse life events (Prati and Pietrantoni, 2006)—a phenomenon named post-traumatic growth (PTG) (e.g., Lee et al., 2010; Wlodarczyk et al., 2016; Gil-González et al., 2022). PTG is linked to lower levels of depression (Helgeson et al., 2006), higher satisfaction with life (Mols et al., 2009), optimism, and positive wellbeing (Helgeson et al., 2006).

What emerged in the interview with Grace’s words was in line also with levels of PTG total score, and subscales (relating to others, new possibilities, appreciation of life, and spiritual change) increased after the IRT treatment in both follow-ups; in particular for the total score, the increase between T0 and T2 is more than 3-fold higher than the increase from T1 to T2.

Surprisingly, despite the IRT being an effective and specific treatment for trauma-related sleep disturbance and post-traumatic stress (see Casement and Swanson, 2012 for a meta-analysis), to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the effect of this treatment on PTG. Implications for future research design and interpretation of published research will be implemented.

Regarding Grace’s daytime sleepiness during and after the treatment, results may suggest that it was high-normal across the time points. There was not a trend that could suggest a change, maybe because the patient followed therapy with CPAP for OSAS. Despite the literature showing several psychological barriers to CPAP treatment (Rapelli et al., 2021, 2022), Grace reported a good adjustment to it.

Consistent with previous findings, sleep quality improved following IRT treatment (Casement and Swanson, 2012; Albanese et al., 2022). Interestingly, the total PSQI score decreased from 12 (T0) to 8 (T1 and T2), meeting the minimal clinically significant difference of 3, as suggested by prior research (Longo et al., 2021). This improvement in sleep quality was accompanied by a decrease in the emotional intensity and frequency of nightmares measured with the MADRE. However, the level of nightmares-associated emotional distress did not significantly change across time points. The patient reported a neutral emotional state and a moderate level of distress related to nightmares (score 3 = quite distressing) across time points. These findings are different from the literature (Krakow et al., 2001b; Hansen et al., 2013); however, since this article presents a single case study, there is variability due to the involvement of a single subject which does not allow us generalizability. A possible explanation for this finding might be the increase in anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms measured with DASS at the 3-month follow-up and reported by Grace also in the final debriefing: the daily stress with the return to home and work could have had a negative impact on the psychological status. In fact, following her hospitalization and subsequent return home, the patient did not return to the clinic. However, due to divorce, we hypothesize that her psychological symptoms are more related to this stressful situation in the family than to her sleep concerns and post-traumatic events. In the literature, there were contrasting results regarding the effect of IRT on psychological well-being. For example, Lu et al. (2009) did not find improvement in depression after the IRT for war veterans; in contrast, Simard and Nielsen (2009) found that administering a single session of IRT to a group of children with sleep disturbances, but without PTSD diagnosis, led to a reduction in the distress caused by nightmares and to a decrease of other anxious and depressive symptoms.

A limitation of this case study might be that the duration of the intervention was limited to four sessions; in fact, a larger number of sessions would have potentially promoted further improvement in the patient’s outcome; however, this case reflects the common, real-world practice and is also illustrative of successful work with complex patients who complain of significant psychological and physical difficulties. Furthermore, since this article presents a single case study, there is variability due to the involvement of a single subject which does not allow us generalizability. Moreover, since there are no controls, we could not assume that the IRT intervention is more effective than usual care.

This case study suggests that the use of IRT may help to reduce the frequency of nightmares and improve sleep quality in a female patient after ICU for COVID-19. Although additional research is warranted on the specific impact of IRT treatment on PTSD and sleep disorders among patients who experience COVID-19 in an ICU, our case suggests that IRT may be an effective treatment for adults experiencing sleep disturbances and post-traumatic symptoms after admission to an ICU for COVID-19.

Grace at the end of the intervention trusted the method, reporting that she was happy not to have experienced further nightmares related to the ICU. She said she is more aware of her own way of experiencing the emotions related to that traumatic event and reiterated that she is surprised at herself that she was able to give positive growth meaning to the event.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Medical Ethics Committee of the IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano (ID: 2021_03_23_02). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

GR, GV, SS, GPi, AM, GPl, CF, and GC contributed to the development of the study. GR, GV, GPi, and CF contributed to the analysis of the results. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The research study was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer EV declared a past co-authorship with the authors AM, GPl, CF, and GC to the handling editor.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1144087/full#supplementary-material

Albanese, M., Liotti, M., Cornacchia, L., and Mancini, F. (2022). Nightmare Rescripting: using imagery techniques to treat sleep disturbances in post-traumatic stress disorder. Front. Psych. 13:866144. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.866144

Alexander, F. (1993). The corrective emotional experience (1946). Psicoterapia e Scienze Umane 27, 85–101.

Barbieri, G. L., and Musetti, A. (2018). The trans-autobiographical writing in the psychiatric context. J. Poet. Ther. 31, 173–183. doi: 10.1080/08893675.2018.1467819

Beck, K., Vincent, A., Becker, C., Keller, A., Cam, H., Schaefert, R., et al. (2021). Prevalence and factors associated with psychological burden in COVID-19 patients and their relatives: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One 16:e0250590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250590

Borghi, L., Bonazza, F., Lamiani, G., Musetti, A., Manari, T., Filosa, M., et al. (2021). Dreaming during lockdown: a quali-quantitative analysis of the Italian population dreams during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave. Res. Psychother. 24:547. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2021.547

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., and Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

Carney, C. E., Buysse, D. J., Ancoli-Israel, S., Edinger, J. D., Krystal, A. D., Lichstein, K. L., et al. (2012). The consensus sleep diary: standardizing prospective sleep self-monitoring. Sleep 35, 287–302. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1642

Casement, M. D., and Swanson, L. M. (2012). A meta-analysis of imagery rehearsal for post-trauma nightmares: effects on nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and posttraumatic stress. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 566–574. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.002

Curcio, G., Tempesta, D., Scarlata, S., Marzano, C., Moroni, F., Rossini, P. M., et al. (2013). Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI). Neurol. Sci. 34, 511–519. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1085-y

Eadie, J., van de Water, A. T., Lonsdale, C., Tully, M. A., van Mechelen, W., Boreham, C. A., et al. (2013). Physiotherapy for sleep disturbance in people with chronic low back pain: results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 94, 2083–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.04.017

Ellis, T. E., Rufino, K. A., and Nadorff, M. R. (2019). Treatment of nightmares in psychiatric inpatients with imagery rehearsal therapy: an open trial and case series. Behav. Sleep Med. 17, 112–123. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2017.1299738

Franceschini, C., Musetti, A., Zenesini, C., Palagini, L., Scarpelli, S., Quattropani, M. C., et al. (2020). Poor sleep quality and its consequences on mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Front. Psychol. 11:574475. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.574475

Gagnier, J. J., Kienle, G., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., Sox, H., and Riley, D. (2013). The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. J. Med. Case Rep. 7, 1–6. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-223

Gamberini, L., Mazzoli, C. A., Prediletto, I., Sintonen, H., Scaramuzzo, G., Allegri, D., et al. (2021). Health-related quality of life profiles, trajectories, persistent symptoms and pulmonary function one year after ICU discharge in invasively ventilated COVID-19 patients, a prospective follow-up study. Respir. Med. 189:106665. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106665

Germain, A. (2013). Sleep disturbances as the hallmark of PTSD: where are we now? Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 372–382. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040432"

Gieselmann, A., Ait Aoudia, M., Carr, M., Germain, A., Gorzka, R., Holzinger, B., et al. (2019). Aetiology and treatment of nightmare disorder: state of the art and future perspectives. J. Sleep Res. 28:e12820. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12820

Gil-González, I., Pérez-San-Gregorio, M. Á., Conrad, R., and Martín-Rodríguez, A. (2022). Beyond the boundaries of disease—significant post-traumatic growth in multiple sclerosis patients and caregivers. Front. Psychol. 13:903508. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903508

Giusti, E. M., Pedroli, E., D'Aniello, G. E., Stramba Badiale, C., Pietrabissa, G., Manna, C., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684

Giusti, E. M., Veronesi, G., Callegari, C., Castelnuovo, G., Iacoviello, L., and Ferrario, M. M. (2022). The north Italian longitudinal study assessing the mental health effects of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic health care workers—part II: structural validity of scales assessing mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:9541. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159541

Hansen, K., Höfling, V., Kröner-Borowik, T., Stangier, U., and Steil, R. (2013). Efficacy of psychological interventions aiming to reduce chronic nightmares: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33, 146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.012

Helgeson, V. S., Reynolds, K. A., and Tomich, P. L. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 74, 797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797

Helms, J., Kremer, S., Merdji, H., Clere-Jehl, R., Schenck, M., Kummerlen, C., et al. (2020). Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 2268–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597

Hughes, C. M., McCullough, C. A., Bradbury, I., Boyde, C., Hume, D., Yuan, J., et al. (2009). Acupuncture and reflexology for insomnia: a feasibility study. Acupunct. Med. 27, 163–168. doi: 10.1136/aim.2009.000

Janiri, D., Carfì, A., Kotzalidis, G. D., Bernabei, R., Landi, F., Sani, G., et al. (2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after severe COVID-19 infection. JAMA Psychiat. 78, 567–569. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0109

Johns, M. W. (1991). A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14, 540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540

Kaseda, E. T., and Levine, A. J. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder: a differential diagnostic consideration for COVID-19 survivors. Clin. Neuropsychol. 34, 1498–1514. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2020.1811894

Kellner, R., Neidhardt, J., Krakow, B., and Pathak, D. (1992). Changes in chronic nightmares after one session of desensitization or rehearsal instructions. Am. J. Psychiatry 149, 659–663. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.5.659

Krakow, B., Germain, A., Tandberg, D., Koss, M., Schrader, R., Hollifield, M., et al. (2000). Sleep breathing and sleep movement disorders masquerading as insomnia in sexual-assault survivors. Compr. Psychiatry 41, 49–56. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90131-7"

Krakow, B., Hollifield, M., Johnston, L., Koss, M., Schrader, R., Warner, T. D., et al. (2001b). Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286, 537–545. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.537

Krakow, B., Melendrez, D., Pedersen, B., Johnston, L., Hollifield, M., Germain, A., et al. (2001a). Complex insomnia: insomnia and sleep-disordered breathing in a consecutive series of crime victims with nightmares and PTSD. Biol. Psychiatry 49, 948–953. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01087-8"

Krakow, B., and Neidhardt, E. J. (1992). Conquering bad dreams and nightmares: a guide to understanding, interpretation, and cure. New York: Berkley."

Krakow, B., and Zadra, A. (2006). Clinical management of chronic nightmares: imagery rehearsal therapy. Behav. Sleep Med. 4, 45–70. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0401_4

Krakow, B., and Zadra, A. (2010). Imagery rehearsal therapy: principles and practice. Sleep Med. Clin. 5, 289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2010.01.004"

Kunze, A. E., Lancee, J., Morina, N., Kindt, M., and Arntz, A. (2016). Efficacy and mechanisms of imagery rescripting and imaginal exposure for nightmares: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 17, 1–14.

Lancee, J., Effting, M., and Kunze, A. E. (2021). Telephone-guided imagery rehearsal therapy for nightmares: efficacy and mediator of change. J. Sleep Res. 30:e13123. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13123

Lancee, J., Van Schagen, A. M., Swart, M. L., and Spoormaker, V. I. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for nightmares. Gedragstherapie 44, 95–109.

Lee, J. A., Luxton, D. D., Reger, G. M., and Gahm, G. A. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of the posttraumatic growth inventory with a sample of soldiers previously deployed in support of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J. Clin. Psychol. 66, 813–819. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20692

Longo, U. G., Berton, A., De Salvatore, S., Piergentili, I., Casciani, E., Faldetta, A., et al. (2021). Minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state for the Pittsburgh sleep quality index in patients who underwent rotator cuff tear repair. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:8666. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168666

Lovibond, P. F., and Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 33, 335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U"

Lu, M., Wagner, A., Van Male, L., Whitehead, A., and Boehnlein, J. (2009). Imagery rehearsal therapy for posttraumatic nightmares in US veterans. J. Trauma. Stress. 22, 236–239. doi: 10.1002/jts.2040

Margherita, G., Gargiulo, A., Lemmo, D., Fante, C., Filosa, M., Manari, T., et al. (2021). Are we dreaming or are we awake? A quali–quantitative analysis of dream narratives and dreaming process during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dreaming 31, 373–387. doi: 10.1037/drm0000180

Mazor, Y., Gelkopf, M., Mueser, K. T., and Roe, D. (2016). Posttraumatic growth in psychosis. Front. Psych. 7:202. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00202

McDonnell, L. M., Hogg, L., McDonnell, L., and White, P. (2014). Pulmonary rehabilitation and sleep quality: a before and after controlled study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NPJ Primary Care Respir. Med. 24, 14028–14025. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.28

Miller, C. B., Espie, C. A., Epstein, D. R., Friedman, L., Morin, C. M., Pigeon, W. R., et al. (2014). The evidence base of sleep restriction therapy for treating insomnia disorder. Sleep Med. Rev. 18, 415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.01.006

Mols, F., Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., Coebergh, J. W., and van de Poll-Franse, L. V. (2009). Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol. Health 24, 583–595. doi: 10.1080/08870440701671362

Nagarajan, R., Krishnamoorthy, Y., Basavarachar, V., and Dakshinamoorthy, R. (2022). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of severe COVID-19 infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 299, 52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.040

Neidhardt, E. J., Krakow, B., Kellner, R., and Pathak, D. (1992). The beneficial effects of one treatment session and recording of nightmares on chronic nightmare sufferers. Sleep 15, 470–473.

Pierpaoli-Parker, C., Bolstad, C. J., Szkody, E., Amara, A. W., Nadorff, M. R., and Thomas, S. J. (2021). The impact of imagery rehearsal therapy on dream enactment in a patient with REM-sleep behavior disorder: a case study. Dreaming 31, 195–206. doi: 10.1037/drm0000174

Pietrabissa, G., Volpi, C., Bottacchi, M., Bertuzzi, V., Guerrini Usubini, A., Löffler-Stastka, H., et al. (2021). The impact of social isolation during the covid-19 pandemic on physical and mental health: the lived experience of adolescents with obesity and their caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:3026. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063026

Poschmann, I. S., Palic-Kapic, S., Sandahl, H., Berliner, P., and Carlsson, J. (2021). Imagery rehearsal therapy for trauma-affected refugees–a case series. Int. J. Dream Res. 14, 121–130. doi: 10.11588/ijodr.2021.1.77853

Prati, G., and Pietrantoni, L. (2006). Crescita post-traumatica: Un’opportunità dopo il trauma? [post-traumatic growth: an opportunity after the trauma?]. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale 12, 133–144.

Prati, G., and Pietrantoni, L. (2014). Italian adaptation and confirmatory factor analysis of the full and the short form of the posttraumatic growth inventory. J. Loss Trauma 19, 12–22. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2012.734203

Rapelli, G., Lopez, G., Donato, S., Pagani, A. F., Parise, M., Bertoni, A., et al. (2020). A postcard from Italy: challenges and psychosocial resources of partners living with and without a chronic disease during COVID-19 epidemic. Front. Psychol. 11:567522. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567522

Rapelli, G., Pietrabissa, G., Angeli, L., Bastoni, I., Tovaglieri, I., Fanari, P., et al. (2022). Assessing the needs and perspectives of patients with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome following continuous positive airway pressure therapy to inform health care practice: a focus group study. Front. Psychol. 13:947346. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.947346

Rapelli, G., Pietrabissa, G., Manzoni, G. M., Bastoni, I., Scarpina, F., Tovaglieri, I., et al. (2021). Improving CPAP adherence in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a scoping review of motivational interventions. Front. Psychol. 12:705364. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.705364

Rogers, J. P., Chesney, E., Oliver, D., Pollak, T. A., McGuire, P., Fusar-Poli, P., et al. (2020). Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0

Rossi, A., Panzeri, A., Pietrabissa, G., Manzoni, G. M., Castelnuovo, G., and Mannarini, S. (2020). The anxiety-buffer hypothesis in the time of COVID-19: when self-esteem protects from the impact of loneliness and fear on anxiety and depression. Front. Psychol. 11:2177. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02177

Rousseau, A. F., Minguet, P., Colson, C., Kellens, I., Chaabane, S., Delanaye, P., et al. (2021). Post-intensive care syndrome after a critical COVID-19: cohort study from a Belgian follow-up clinic. Ann. Intensive Care 11, 118–119. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00910-9

Scarpelli, S., Alfonsi, V., Gorgoni, M., Musetti, A., Filosa, M., Quattropani, M. C., et al. (2021). Dreams and nightmares during the first and second wave of the COVID-19 infection: a longitudinal study. Brain Sci. 11:1375. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11111375

Scarpelli, S., De Santis, A., Alfonsi, V., Gorgoni, M., Morin, C. M., Espie, C., et al. (2022b). The role of sleep and dreams in long-COVID. J. Sleep Res. e13789. Advance online publication.:e13789. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13789

Scarpelli, S., Gorgoni, M., Alfonsi, V., Annarumma, L., Di Natale, V., Pezza, E., et al. (2022c). The impact of the end of COVID confinement on pandemic dreams, as assessed by a weekly sleep diary: a longitudinal investigation in Italy. J. Sleep Res. 31:e13429. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13429

Scarpelli, S., Zagaria, A., Ratti, P. L., Albano, A., Fazio, V., Musetti, A., et al. (2022a). Subjective sleep alterations in healthy subjects worldwide during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sleep Med. 100, 89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2022.07.012"

Schaefer, J. A., and Moos, R. H. (1992). “Life crises and personal growth” in Personal coping: Theory, research, and application. ed. B. N. Carpenter (Westport, CT: Praeger), 149–170.

Settineri, S., Frisone, F., Alibrandi, A., and Merlo, E. M. (2019). Italian adaptation of the Mannheim dream questionnaire (MADRE): age, gender and dream recall effects. Int. J. Dream Res. 12, 119–129. doi: 10.11588/ijodr.2019.1.59328

Simard, V., and Nielsen, T. (2009). Adaptation of imagery rehearsal therapy for nightmares in children: a brief report. Psychotherapy 46, 492–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017945

Szabó, J., and Tóth, S. (2021). Collision every night: treating nightmares with trauma-focused methods: case report. Sleep Vigilance 5, 151–156. doi: 10.1007/s41782-021-00126-8

Tedeschi, R. G., and Calhoun, L. G. (1995). Trauma and transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Van Schagen, A. M., and Lancee, J. (2018). Nachtmerries: prevalentie en behandeling in de specialistische ggz. Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 60, 710–716.

Van Schagen, A. M., Lancee, J., De Groot, I. W., Spoormaker, V. I., and Van den Bout, J. (2015). Imagery rehearsal therapy in addition to treatment as usual for patiens with diverse psychiatric diagnoses suffering from nightmares: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, e1105–e1113. doi: 10.4088/jcp.14m09216

Weidman, K., LaFond, E., Hoffman, K. L., Goyal, P., Parkhurst, C. N., Derry-Vick, H., et al. (2022). Post–intensive care unit syndrome in a cohort of COVID-19 survivors in New York City. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 19, 1158–1168. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202104-520OC

Weinberg, M., Mollon, B., Kaplan, D., Zuckerman, J., and Strauss, E. (2020). Improvement in sleep quality after total shoulder arthroplasty. Phys. Sports Med. 48, 194–198. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2019.1671142

Keywords: case report, imagery rehearsal therapy, intensive care unit, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, nightmare, sleep disorder

Citation: Rapelli G, Varallo G, Scarpelli S, Pietrabissa G, Musetti A, Plazzi G, Franceschini C and Castelnuovo G (2023) The long wave of COVID-19: a case report using Imagery Rehearsal Therapy for COVID-19-related nightmares after admission to intensive care unit. Front. Psychol. 14:1144087. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1144087

Received: 13 January 2023; Accepted: 19 April 2023;

Published: 18 May 2023.

Edited by:

Antonella Granieri, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

Elena Vegni, University of Milan, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Rapelli, Varallo, Scarpelli, Pietrabissa, Musetti, Plazzi, Franceschini and Castelnuovo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giada Rapelli, Z2lhZGEucmFwZWxsaUB1bmlwci5pdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.