95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 11 May 2023

Sec. Consciousness Research

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1119115

This article is part of the Research Topic Psychedelic Humanities View all 21 articles

A commentary has been posted on this article:

Commentary: ARC: a framework for access, reciprocity and conduct in psychedelic therapies

Meg J. Spriggs1,2

Meg J. Spriggs1,2 Ashleigh Murphy-Beiner1,3

Ashleigh Murphy-Beiner1,3 Roberta Murphy1,4

Roberta Murphy1,4 Julia Bornemann1,2

Julia Bornemann1,2 Hannah Thurgur2

Hannah Thurgur2 Anne K. Schlag1,2*

Anne K. Schlag1,2*The field of psychedelic assisted therapy (PAT) is growing at an unprecedented pace. The immense pressures this places on those working in this burgeoning field have already begun to raise important questions about risk and responsibility. It is imperative that the development of an ethical and equitable infrastructure for psychedelic care is prioritized to support this rapid expansion of PAT in research and clinical settings. Here we present Access, Reciprocity and Conduct (ARC); a framework for a culturally informed ethical infrastructure for ARC in psychedelic therapies. These three parallel yet interdependent pillars of ARC provide the bedrock for a sustainable psychedelic infrastructure which prioritized equal access to PAT for those in need of mental health treatment (Access), promotes the safety of those delivering and receiving PAT in clinical contexts (Conduct), and respects the traditional and spiritual uses of psychedelic medicines which often precede their clinical use (Reciprocity). In the development of ARC, we are taking a novel dual-phase co-design approach. The first phase involves co-development of an ethics statement for each arm with stakeholders from research, industry, therapy, community, and indigenous settings. A second phase will further disseminate the statements for collaborative review to a wider audience from these different stakeholder communities within the psychedelic therapy field to invite feedback and further refinement. By presenting ARC at this early stage, we hope to draw upon the collective wisdom of the wider psychedelic community and inspire the open dialogue and collaboration upon which the process of co-design depends. We aim to offer a framework through which psychedelic researchers, therapists and other stakeholders, may begin tackling the complex ethical questions arising within their own organizations and individual practice of PAT.

One in eight people in the world today are living with a mental health difficulty (World Health Organization, 2022), and there are increasing demands for the development of new approaches to mental health treatment. Despite an overall growth in mental health research, the proportion of studies looking at new interventions, particularly of a pharmacological nature, has declined, with many large pharmaceutical companies withdrawing funding. As a result, there have been few, if any, major pharmaceutical breakthroughs since the 1950s (Hyman, 2013; Stephan et al., 2016; Nutt et al., 2020; Wortzel et al., 2020). There has also been a growing recognition of the wider social, ecological, and socio-economic determinants of mental wellbeing and the health inequalities this represents. This has shaped the resulting calls for a greater focus on integrative, collaborative, and community-based care to better support mental wellbeing for all (Shim et al., 2014; Commission for Equality in Mental Health, 2020; Knifton and Inglis, 2020; World Health Organization, 2022).

Psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT)1 has been suggested as a paradigm shift that could address many of the challenges the fields of psychiatry face (Schenberg, 2018; Nutt et al., 2020, Nutt et al., 2022; Petranker et al., 2020; Lu, 2021). Since 2006, there has been extensive growth, in the number of clinical trials conducted, the potential conditions for which PAT is being investigated, as well as in the number of research centers across the globe that are undertaking these trials (Aday et al., 2020; Reiff et al., 2020; Yaden et al., 2021). Where once funding came primarily from philanthropists, corporate enterprises and private investors are now interested in this new approach and are funding a rapid expansion of the field (Phelps et al., 2022; Schwarz-Plaschg, 2022).

Drawing upon the (thus far) positive results of research, a media spotlight has also been placed upon psychedelics (Pilecki et al., 2021; Williams M. L. et al., 2021). Yet, psychedelics remain illegal in most jurisdictions across the world. Given the success of grassroots movements in instigating psilocybin decriminalization initiatives in parts of the US, and recent regulatory changes permitting the prescription of psilocybin and MDMA in Australia from July 2023 onward, it is possible similar public interest initiatives will develop in other parts of the world. Public support has also facilitated early access and compassionate use schemes in some countries that bypass the slow and meticulous pace of research where some deem existing evidence as sufficient to claim it unethical to withhold the treatment for those in need (Greif and Šurkala, 2020). This growing awareness has come alongside rising rates of naturalistic psychedelic use and increasing numbers of psychedelic retreats being offered in many countries globally (Yockey et al., 2020; Killion et al., 2021; Yockey and King, 2021; Glynos et al., 2022). A greater demand for reliable harm reduction information is demonstrated by the growing number of training programmes, referral networks, and psychedelic integration circles run for and by healthcare professionals (Pilecki et al., 2021).

Standing at the helm of a potential paradigm shift, the psychedelic research community now has the opportunity to help steer the future of PAT in a fair and sustainable manner. Within the broader context, there is a pressing need to better understand how these treatments might be most equitably and ethically delivered. The speed at which the field of PAT is moving has already begun to unearth cracks. Reports of unethical conduct have surfaced from both inside and outside the legal framework [Peluso et al., 2020; Psymposia and New York Magazine Cover Story (Power Trip), 2022; Schwarz-Plaschg, 2022]. Additionally, the assimilation of psychedelics into a purely biomedical framework risks repeating historical injustices and exacerbating inequities (Devenot et al., 2022; Schwarz-Plaschg, 2022). This has led some to question the capacity of this budding field to maintain ethical integrity (Williams M. L. et al., 2021; Yaden et al., 2021; Phelps et al., 2022) and has resulted in a flourish in ethical comments in both the public and academic domain (Smith and Sisti, 2020; Brennan et al., 2021; Pilecki et al., 2021; Thal et al., 2021; Williams M. L. et al., 2021; McMillan, 2022; Smith and Appelbaum, 2022). Ethical and practice guidelines for how, when, and by whom PAT should be conducted have been developed by different actors including research establishments [e.g., MAPS (Carlin and Scheld, 2019)], professional bodies [e.g., Psychedelic Association of Canada (PAC, 2022)], and community led/grassroots organizations [e.g., the North Star Pledge (North Star Ethics Pledge, 2020) and Chacruna’s Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative (Chacruna, 2021)]. At present, this growing wisdom is diffuse and often at times context specific. With no overarching framework from which to work across sectors, there is a risk that many of these important ethical questions may fall to the wayside as the psychedelic movement accelerates forward.

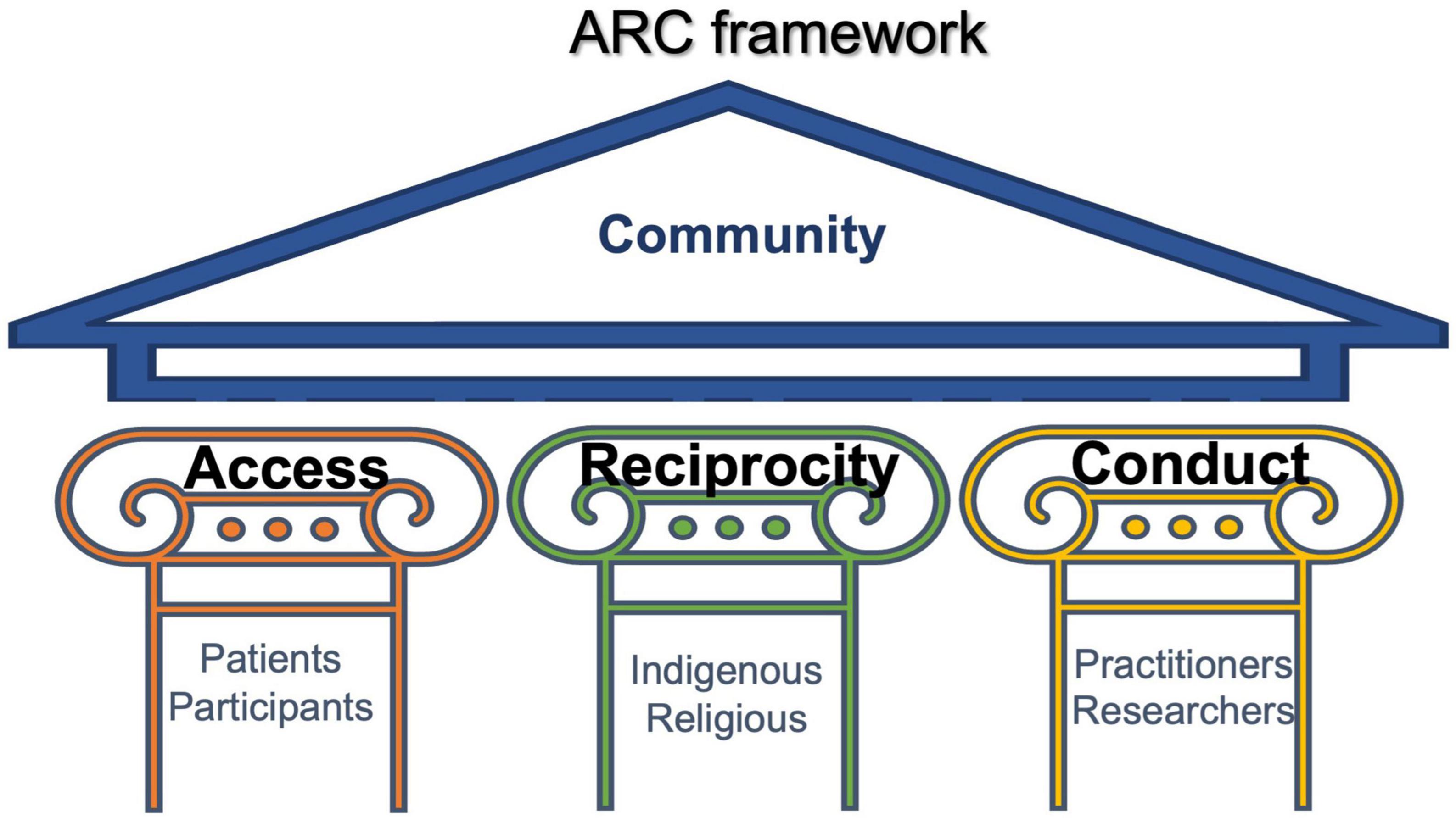

Here we present Access, Reciprocity and Conduct (ARC); a framework for ethically informed ARC in psychedelic therapies (Figure 1). The three pillars of ARC represent a commitment to equitable access to psychedelic therapies (Access), a respect for traditional and spiritual uses of psychedelics (Reciprocity), and the safe and ethical delivery of PAT in clinical settings (Conduct). Each pillar subsumes its own unique ethical challenges that are far-reaching and multifaceted. In an effort to balance complexity and parsimony, the ARC framework provides a scaffold for in-depth independent explorations of each pillar, while offering opportunity for shared learning. As depicted in Figure 1, different stakeholders hold particular relevance to each pillar, however, their interdependence is critical for supporting the continued growth of policy, industry, research, clinical and community-based infrastructure. Here, we provide background on each of these pillars, before outlining the development process for ARC.

Figure 1. The ARC framework consists of three pillars: Access, Reciprocity and Conduct. The strength of each pillar calls upon specific actors, but it is their interdependence that is critical to an equitable and culturally informed ethical framework.

It is well documented that mental health disparities exist at global, national, and local levels (Weich et al., 2001; Amaddeo and Jones, 2007; Evans-Lacko et al., 2018). The social determinants of mental health outcomes are also well established, showing that marginalized groups (those who experience social and political inequality) are disproportionately affected by mental distress (Alegría et al., 2018). Low socioeconomic status is related to both poor mental health outcomes and limitations in accessing care, with poverty being both a causal factor and a consequence of mental health difficulties (Alegría et al., 2018). Discrimination related to race, ethnicity, immigrant status, sexual orientation and other marginalized identities are also strongly associated with negative mental health outcomes (Benoit et al., 2015; Berger and Sarnyai, 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Hynie, 2018; Pachter et al., 2018).

There are multiple barriers to accessing mental healthcare for marginalized groups. There are not only practical barriers (e.g., distance, costs of transport, loss of income to attend appointments) but also psycho-social and cultural barriers (e.g., culturally inappropriate models of illness, stigma, racism and discrimination, history of abuses by mental healthcare and research, and a resulting fear and mistrust toward accessing healthcare services (Amaddeo and Jones, 2007; Memon et al., 2016). As such, even in countries where efforts are made to improve equal access through the national provision of free healthcare (e.g., through the UK National Health Service), the distribution of needs-based care is socially patterned, meaning that those from marginalised2 groups who do access mental healthcare, are still more likely to receive a poor service, and one which is not designed to adequately meet their needs (Watt, 2018).

Psychedelic assisted therapy runs the risk of also exacerbating these existing inequalities in access to healthcare. Misconceptions and laws surrounding drugs, including psychedelics, propagated by historical mistruths in the media and “the war on drugs” have disproportionately impacted marginalized groups by the disruption of communities, as well as racial stereotyping, profiling, and discrimination (Hutchison and Bressi, 2021; Rea and Wallace, 2021). Additionally, a history of exploitation in psychedelic research carried out between the 1950s and 1980s (Strauss et al., 2022) has left a legacy of mistrust toward science and healthcare among underrepresented communities. This has all played a part in perpetuating inadequate representation of marginalized groups within modern research settings; both in participants of clinical trials and, in some research teams themselves (Michaels et al., 2018, 2022; Buchanan, 2021; Williams M. T. et al., 2021). This under-representation means the results of PAT research may not be generalizable to marginalized groups. Consequently, this may form part of a vicious cycle in which some PAT practitioners and models do not adequately consider the necessary adaptations for working appropriately and sensitively with the people represented. If legalized, PAT may also be a prohibitively expensive treatment, meaning there is a serious need to consider affordable models of care across disparate healthcare contexts from the start. If equity is not prioritized in the current research context, or in the development and regulation of legally available treatments, the risk of perpetuating healthcare inequalities is high (Rea and Wallace, 2021).

Well-conducted research, which invites co-design and collaboration from members of marginalized groups, may contribute to shaping more widely applicable models of psychedelic care. However, this will not happen without deliberate and conscious action. The goal of the “Access” pillar of the ARC framework is to identify priority areas for PAT in research and clinical contexts to suggest actionable steps toward the development of inclusive, equitable and culturally sensitive models of care and practice.

Many Indigenous peoples have stewarded psychedelics as traditional medicines for millennia, cultivating relationships with and accumulated knowledge on various plants, fungi and cacti, some of which are now used in PAT (Celidwen et al., 2023).

As plant psychedelics mature as medicines in Western contexts, a degree of commercialization of these compounds and their sacred ancient practices seems inevitable. Numerous companies and individuals are already profiting from speculative investments with few, if any, benefits accruing to Indigenous peoples (Williams et al., 2022).3 Rather, Indigenous peoples are often left out of the sector, as the field is currently widely represented by Westerners. This raises moral and ethical issues, such as those related to cultural appropriation, patenting of “the sacred” and exclusionary practices in research and praxis. These must be addressed if the psychedelic ecosystem is to develop in an equitable and sustainable manner.

Initiatives for addressing reciprocity have been launched by various organizations. For example, the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative helps Indigenous peoples create conditions for medicine development (Chacruna, 2021), while other initiatives focus on avenues for financial support [e.g., Grow Medicine (2022) and the Indigenous Medicine Conservation Fund (2022)]. The variability of these approaches reflects the complexity of their aims and objectives, and these are yet to be standardized into guidelines for if and how to give back to traditional knowledge carriers of ancient plant medicines.

Recently, presenting an all-encompassing approach, an Indigenous-led globally represented group of practitioners, activists, scholars, lawyers, and human rights defenders convened to formulate a set of ethical guidelines concerning traditional Indigenous medicines current use in Western psychedelic research and practice (Celidwen et al., 2023). Appreciating the challenges in discussing reciprocity and benefit sharing, the group nevertheless identified eight interconnected ethical principles for engaging with Indigenous peoples in relation to psychedelic research and practise: Reverence, Respect, Responsibility, Relevance, Regulation, Reparation, Restoration, and Reconciliation. This transdisciplinary and transcultural group aims to continue their important work by further examining the implementation, policy recommendations, and practical applications of plant psychedelics, including the variety of Indigenous voices.

This approach, as well as the overarching aims, are similar to the Reciprocity pillar of ARC. The first step of our focus groups was to identify key priorities to support the reciprocity and sustainability of psychedelics, and subsequently translate these into actionable recommendations. These findings are currently being prepared for a separate publication as they go beyond the scope of the present paper which aims to introduce the ARC framework per se.

Holding reciprocity as a core value in an ethical framework is hoped to contribute to a culture that makes psychedelic medicines available in a way that respects the lineages of Indigenous knowledges, that are essentially–not accidentally–coupled with many of the psychedelic plants on which Western psychedelic medicines are based (Devenot et al., 2022). Protecting participants and patients as psychedelics move into the mainstream is essential, but equally it is essential to create an environment which supports the autonomy and protection of traditional carriers of these medicines. In this way, the Reciprocity pillar of the ARC framework is interconnected with the Access and Conduct pillars, whereby the values of humanity instilled by an inclusive worldview are incorporated across all pillars.

The issues discussed here are by no means novel or limited to developments in the psychedelic therapy field. The exploitation of natural resources and traditional knowledges relates to much broader concerns than plant medicines. However, with the rapid developments of psychedelic medicines in the West, and the benefits as well as risks that these expansions may bring, there is an opportunity to consider how best to develop this sector in a fair manner, so that benefits are not limited to (largely) Western companies but rather shared with the traditional knowledge bearers who have paved the way for current developments and without whom today’s “psychedelic renaissance” in the Global North might not be happening. These issues go deeper than the commercialization of psychedelic medicines, touching on values of how to treat nature and humanity. It is the responsibility of PAT practitioners, researchers, and other stakeholders to reflect on the ethical dilemmas caused by the commercialization of nature and the sacred, and also to rise to the challenge of developing impactful initiatives toward reciprocity and sustainability.

The “conduct” arm of the ARC framework concerns how those involved in developing and delivering psychedelic-assisted therapy carry out their activities, and how PAT is made available to patients and clinical trial participants. Ethical dilemmas occur at every level of the psychedelic therapy system, from the participant-therapist dyad to the conduct of teams, professionals, and the wider socio-political system (Anderson et al., 2020; Read and Papaspyrou, 2021; Thal et al., 2021). Conduct, within the ARC framework, concerns the values and processes involved in developing and delivering PAT, and it is therefore inextricably linked to access and reciprocity. To meaningfully consider the ethics of conduct at every level is a necessarily arduous task, which will take the concerted efforts of many over time.

With the rapid expansion of PAT in clinical trials there is an immediate need to consider the complexity of the participant-therapist dyad in the clinic room (Thal et al., 2021) and therefore this is a key focus. At present, there is no formal certification process for becoming a psychedelic therapist and what (if any) qualifications or training should be required has yet to be established (Phelps, 2017; Williams M. L. et al., 2021). Whilst therapists are governed by the standards of their professional regulating bodies, these ethical codes and practice guidelines do not cover work with psychedelics (Phelps, 2017; Brennan et al., 2021; Thal et al., 2021). Equally, many “psychedelic sitters” both inside and outside research environments are not therapeutically trained and so are not governed by any therapeutic ethical codes. As a result, there are few places offering support or guidance on the complexity of this work. Issues pertaining to the use of therapeutic touch, power dynamics, and boundary transgressions have already begun to surface (McLane et al., 2021).

As patients enter into highly vulnerable and even regressed states with psychedelics, challenging aspects of the ordinary therapeutic relationship and process are amplified (Grof, 2000; Brennan et al., 2021; Read and Papaspyrou, 2021; Thal et al., 2021; Murphy et al., 2022). Viewed through a psychotherapeutic lens, these include complex transferential issues, anxieties, and psychological defenses and enactments; all of which may impede improvement or lead to adverse outcomes if not managed appropriately (Grof, 2000; Thal et al., 2021). Questions such as how to obtain informed consent (Grof, 2000; Smith and Sisti, 2020) how best to support participants who have had spiritual experiences (Grof, 2000), or how to approach the emergence of possible new memories of abuse (Thal et al., 2021) or collective trauma (Williams M. T. et al., 2021) are just a few of the ethical dilemmas practitioners are facing. There are questions as to who this treatment can help and how (Murphy et al., 2022) when it might be unhelpful or harmful (Anderson et al., 2020) and how to work in culturally sensitive ways and with marginalized groups (Anderson et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2020; Williams M. T. et al., 2021).

There is a complex myriad of ethical and clinical issues therapists, sitters and participants can be presented with, which highlights the urgent need for comprehensive ethical and practice guidelines for PAT. Existing documents of this kind (Bevir et al., 2019; Carlin and Scheld, 2019; Guild of Guides, 2020; North Star Ethics Pledge, 2020; Council on Spiritual Practices, 2022; From The Conclave, 2022; Murphy et al., 2022; PAC, 2022) have typically been developed for a specific context and a specific psychedelic substance. We plan to integrate, develop, and expand on these with the involvement of relevant stakeholders such as past participants, therapists of different therapeutic orientations, sitters, and researchers which will be reported in a separate publication. Regardless of theoretical orientation, profession, or context, these guidelines will provide helpful tools for working safely and ethically. These fundamentals of practice can then be used along with others to inform trainings, certification processes, and minimum professional standards. Established standards of care will provide an essential level of professionalism and containment to practitioners supporting the therapeutic process of PAT. It would be a disservice to the depth of this therapeutic modality to suggest simple solutions to the complex questions this work presents. Rather than a set of rigid or inflexible rules, the ARC framework intends to suggest guidelines which are expected to continue to evolve as more is learned and understood about the use of PAT.

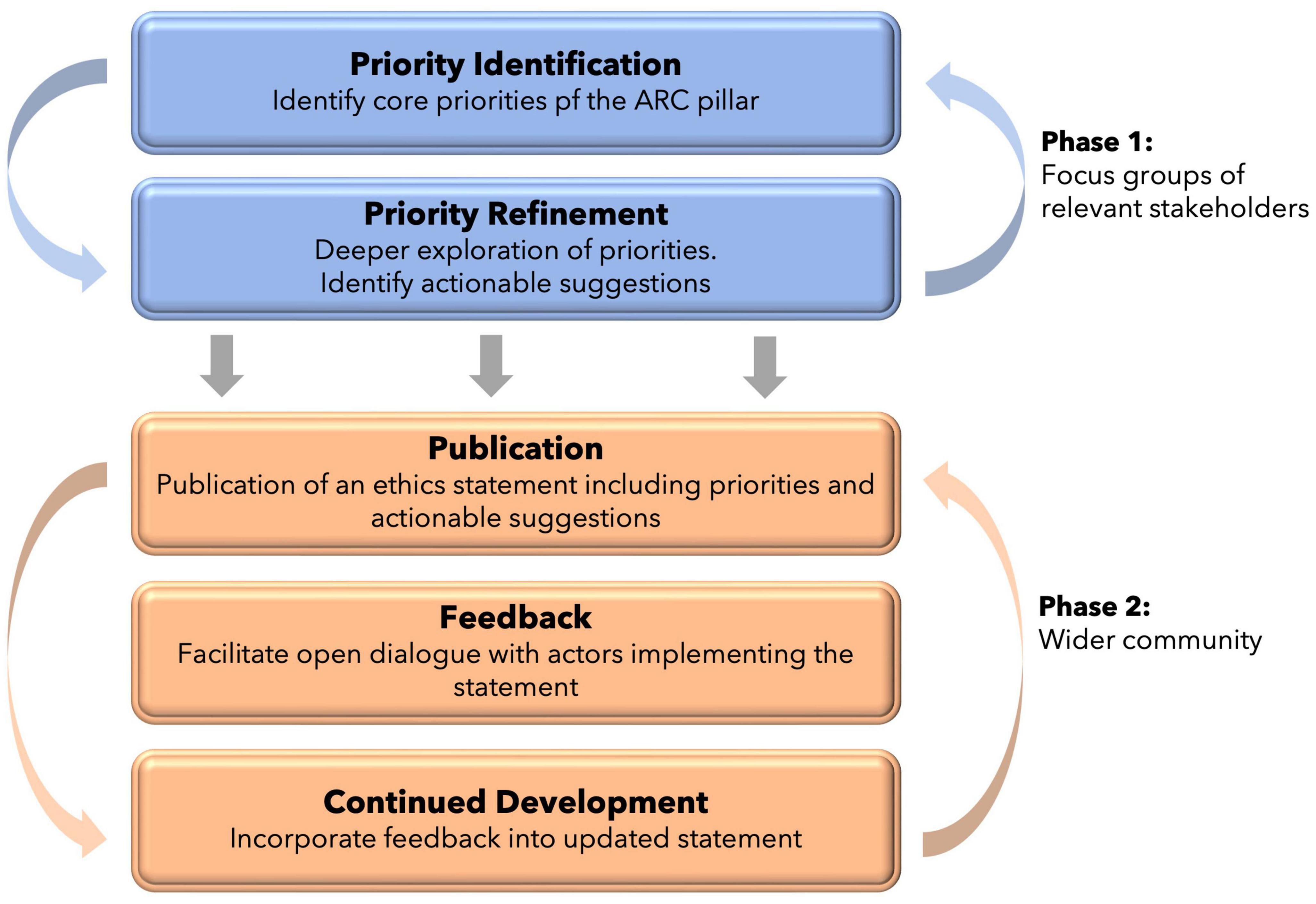

Co-design is an approach being widely adopted in research, policy, and service design, and refers to the active and deliberate involvement of different stakeholders in exploring, developing and evaluating initiatives (O’Brien and Vincent, 2003; Boyd et al., 2012; Blomkamp, 2018; Bevir et al., 2019; Close et al., 2021; Eseonu, 2022). Not only is co-design a tool for better decision making, but it also considers the influence of existing power dynamics and inequalities, and gives stakeholders an opportunity to address fractionization (Bevir et al., 2019). Here, we employ co-design in two ways (1) the use of focus groups in the generation of the initial ethical statements, and (2) opening up for feedback from the wider transdisciplinary communities of stakeholders involved in PAT, based on real-world practical implementation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The dual-phase process for co-design of the three ethics statements of ARC. Phase 1 refers to co-design within small focus-groups. Phase 2 refers to co-design with the wider community through implementation and continued feedback.

At the time of writing, the ethical statements for the three ARC pillars are within the first stage of development: the use of focus groups to develop the ethics statements. Given the complexity of each theme, a statement for each of the three pillars will be developed independently. The process is iterative, whereby key ethical principles are identified, explored, and molded through multiple open discussions with a focus group of different stakeholders. The stakeholders have been identified to be representative of the actors most closely implicated in the ARC pillar in question, and come from research, industry, community, anthropological, policy, and indigenous contexts. The goal of these focus groups is not to produce the answers but to bring important questions and potential solutions into our shared awareness, so as to promote future focus, expansion, and research on important themes. As the coordinators of ARC, our role is to elicit the guiding principles, priorities, and wider substance of the ethical framework. Each pillar is working under an independent timeline, however, work began on this process in August 2021.

At the end of this phase of the process, a statement on ethics and practice will be produced and published for each of the three pillars. Each statement will provide recommendations, guidelines and thinking tools to provide pragmatic steps others can incorporate into their practice in their own context. Importantly, we do not view this as the end of the process. Once publicly available, we invite further feedback from the wider psychedelic community on the implementation of the framework. We envision that all three statements will hold relevance for most PAT clinical contexts and holding them all under the shared ARC framework allows for a more coherent integration with one another. It is hoped that this process will empower psychedelic research, practitioners and organizations to tackle these ethical issues within the scope of their own work.

Meeting the unique and multifaceted ethical and practice demands of PAT will take careful forethought, interdisciplinary collaboration, and humility. In line with the current developments in psychedelic medicine, and the nascent psychedelic industry, the incorporation of guidelines addressing safety, reciprocity and equity is vital yet difficult to develop and challenging to implement. The future potential of PAT can only be fully realized if the broader socio-cultural context is considered, and both patients and traditional communities are included as key stakeholders, and decision makers.

ARC represents a framework that embodies reciprocity, protects conduct, and prioritizes equity of access, valuing the knowledge and experience of traditional Indigenous healers, therapists, scientists, participants and the wider community. It is hoped that this will springboard important ethical conversations in research, therapy and public domains, so that the safe and ethical development of these treatments can be at the forefront when the field of PAT matures.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

MS, AM-B, and AS conceived the study. MS had oversight of the writing of the manuscript with contributions from AM-B, AS, JB, HT, and RM. All authors developed the study and revised the manuscript.

The authors would like to acknowledge all the contributors and public collaborators who have made this work possible.

AS was Head of Research of Drug Science. HT was Senior Research Officer at Drug Science. Drug Science receives an unrestricted educational grant from a consortium of medical psychedelics companies to further its mission, that is the pursuit of an unbiased and scientific assessment of drugs regardless of their regulatory class. All Drug Science committee members, including the Chair, are unpaid by Drug Science for their effort and commitment to this organization. As part of her position at AS and HT collaborates with industry partners who are researching the development of psychedelic treatments. AS was Scientific Advisor at Psych Capital. None of the authors would benefit from the wider prescription of medical psychedelics in any form, and none of the companies have been involved in the development and funding of this research.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aday, J. S., Bloesch, E. K., and Davoli, C. C. (2020). 2019: a year of expansion in psychedelic research, industry, and deregulation. Drug Sci. Policy Law 6, 1–6. doi: 10.1177/2050324520974484

Alegría, M., NeMoyer, A., Bagué, I. F., Wang, Y., and Alvarez, K. (2018). Social determinants of mental health: where we are and where we need to go. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 20:95. doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0969-9

Amaddeo, F., and Jones, J. (2007). What is the impact of socio-economic inequalities on the use of mental health services? Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 16, 16–19. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00004565

Anderson, B. T., Danforth, A. L., and Grob, C. S. (2020). Psychedelic medicine: safety and ethical concerns. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 829–830. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30146-2

Anderson, K. N., Bautista, C. L., and Hope, D. A. (2019). Therapeutic alliance, cultural competence and minority status in premature termination of psychotherapy. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 89:104. doi: 10.1037/ort0000342

Benoit, C., McCarthy, B., and Jansson, M. (2015). Occupational stigma and mental health: discrimination and depression among front-line service workers. Can. Public Policy 41, (Suppl. 2), S61–S69. doi: 10.3138/cpp.2014-077

Berger, M., and Sarnyai, Z. (2015). More than skin deep”: stress neurobiology and mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Stress 18, 1–10. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2014.989204

Bevir, M., Needham, C., and Waring, J. (2019). Inside co-production: ruling, resistance, and practice. Soc. Policy Adm. 53, 197–202. doi: 10.1111/spol.12483

Blomkamp, E. (2018). “The promise of co-design for public policy 1,” in Routledge Handbook of Policy Design, eds M. H. Howlett and I. Mukherjee (Milton Park: Routledge) doi: 10.4324/9781351252928-4

Boyd, H., McKernon, S., Mullin, B., and Old, A. (2012). Improving healthcare through the use of co-design. NZ Med. J. 125, 76–87.

Brennan, W., Jackson, M. A., MacLean, K., and Ponterotto, J. G. (2021). A qualitative exploration of relational ethical challenges and practices in psychedelic healing. J. Humanist Psychol. doi: 10.1177/00221678211045265 [Epub ahead of print].

Buchanan, N. T. (2021). Ensuring the psychedelic renaissance and radical healing reach the Black community: commentary on culture and psychedelic psychotherapy. J. Psychedelic. Stud. 4, 142–145. doi: 10.1556/2054.2020.00145

Carlin, S. C., and Scheld, S. (2019). MAPS MDMA-assisted psychotherapy code of ethics. Multidiscip. Assoc. Psychedelic Stud. Bull. 29, 24–27.

Celidwen, Y., Redvers, N., Githaiga, C., Calambás, J., Añaños, K., Chindoy, M. E., et al. (2023). Ethical principles of traditional Indigenous medicine to guide western psychedelic research and practice. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 18:100410. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100410

Chacruna (2021). Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative of the Americas. Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative. Available online at: https://chacruna-iri.org/ (accessed November 15, 2022).

Close, J. B., Bornemann, J., Piggin, M., Jayacodi, S., Luan, L. X., Carhart-Harris, R., et al. (2021). Co-design of guidance for patient and public involvement in psychedelic research. Front. Psychiatry 12:727496. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.727496

Commission for Equality in Mental Health (2020). Mental Health for All? the Final Report of the Commission for Equality in Mental Health. London: Centre for Mental Health

Cookson, R., Doran, T., Asaria, M., Gupta, I., and Mujica, F. P. (2021). The inverse care law re-examined: a global perspective. Lancet 397, 828–838. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00243-9

Council on Spiritual Practices (2022). Code of Ethics for Spiritual Guides. Available online at: https://csp.org/docs/code-of-ethics-for-spiritual-guides (accessed April 15, 2023).

Devenot, N., Conner, T., and Doyle, R. (2022). Dark side of the shroom: erasing indigenous and counterculture wisdoms with psychedelic capitalism, and the open source alternative. Anthropol. Conscious. 33, 476–505. doi: 10.1111/anoc.12154

Eseonu, T. (2022). Co-creation as social innovation: including ‘hard-to-reach’groups in public service delivery. Public Money Manag. 42, 306–313. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2021.1981057

Evans-Lacko, S., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bruffaerts, R., et al. (2018). Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol. Med. 48, 1560–1571. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003336

From The Conclave (2022). 5-MEO-DMT Recommended Model for Best Practices. Available online at: https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5dab753665b2d985ff08d69b/5dab753665b2d92d7808d6d1_Best%20Practices%20Outline%20(Finalv9).pdf (accessed April 15, 2023).

Gerber, K., Flores, I. G., Ruiz, A. C., Ali, I., Ginsberg, N. L., and Schenberg, E. E. (2021). Ethical concerns about psilocybin intellectual property. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 4, 573–577. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00171

Glynos, N. G., Fields, C. W., Barron, J., Herberholz, M., Kruger, D. J., and Boehnke, K. F. (2022). Naturalistic psychedelic use: a world apart from clinical care. J. Psychoactive Drugs 11, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2022.2108356

Greif, A., and Šurkala, M. (2020). Compassionate use of psychedelics. Med. Health Care Philos. 23, 485–496. doi: 10.1007/s11019-020-09958-z

Grow Medicine (2022). Available online at: https://growmedicine.com/ (accessed April 15, 2023).

Guild of Guides (2020). Code of Conduct – Guild of Guides NL. Available online at: https://www.guildofguides.nl/code-of-conduct/ (accessed December 1, 2022).

Hutchison, C., and Bressi, S. (2021). Social work and psychedelic-assisted therapies: practice considerations for breakthrough treatments. Clin. Soc. Work J. 49, 356–367. doi: 10.1007/s10615-019-00743-x

Hyman, S. (2013). Psychiatric Drug Development: Diagnosing a Crisis. Available online at: https://dana.org/article/psychiatric-drug-development-diagnosing-a-crisis/ (accessed November 11, 2022).

Hynie, M. (2018). The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: a critical review. Can. J. Psychiatry Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie 63, 297–303. doi: 10.1177/0706743717746666

Indigenous Medicine Conservation Fund (2022). Available online at: https://www.imc.fund/ (accessed April 15, 2023).

Killion, B., Hai, A. H., Alsolami, A., Vaughn, M. G., Sehun Oh, P., Salas-Wright, C. P., et al. (2021). LSD use in the United States: trends, correlates, and a typology of us. Drug Alcohol Depend 223, 108715. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108715

Knifton, L., and Inglis, G. (2020). Poverty and mental health: policy, practice and research implications. BJPsych Bull. 44, 193–196. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2020.78

Lee, J. H., Gamarel, K. E., Bryant, K. J., Zaller, N. D., and Operario, D. (2016). Discrimination, mental health, and substance use disorders among sexual minority populations. LGBT Health 3, 258–265. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0135

Lu, D. (2021). ‘Psychedelics Renaissance’: New Wave of Research Puts Hallucinogenics Forward to Treat Mental Health. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/sep/26/psychedelics-renaissance-new-wave-of-research-puts-hallucinogenics-forward-to-treat-mental-health (accessed November 10, 2022).

McLane, H., Hutchison, C., Wikler, D., Howell, T., and Knighton, E. (2021). Respecting Autonomy in Altered States: Navigating Ethical Quandaries in Psychedelic Therapy - Journal of Medical Ethics Blog. Available online at: https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-ethics/2021/12/22/respecting-autonomy-in-altered-states-navigating-ethical-quandaries-in-psychedelic-therapy/ (accessed December 1, 2022).

McMillan, R. M. (2022). Psychedelic injustice: should bioethics tune in to the voices of psychedelic-using communities? Med. Humanit. 48, 269–272. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2021-012299

Memon, A., Taylor, K., Mohebati, L. M., Sundin, J., Cooper, M., Scanlon, T., et al. (2016). Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open 6:e012337. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012337

Michaels, T. I., Lester, I. I. I. L., de la Salle, S., and Williams, M. T. (2022). Ethnoracial inclusion in clinical trials of ketamine in the treatment of mental health disorders. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 83, 596–607. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2022.83.596

Michaels, T. I., Purdon, J., Collins, A., and Williams, M. T. (2018). Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: a review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry 18:245. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1824-6

Murphy, R., Kettner, H., Zeifman, R. J., Giribaldi, B., Kaertner, L., Martell, J., et al. (2022). Therapeutic alliance and rapport modulate responses to psilocybin assisted therapy for depression. Front. Pharmacol. 12:788155. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.788155

Nichols, D. E. (2020). Psilocybin: from ancient magic to modern medicine. J. Antibiot. 73, 679–686. doi: 10.1038/s41429-020-0311-8

North Star Ethics Pledge (2020). Available online at: http://northstar.guide/ethicspledge (accessed November 14, 2022).

Nutt, D., Erritzoe, D., and Carhart-Harris, R. (2020). Psychedelic psychiatry’s brave new world. Cell 181, 24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.020

Nutt, D., Spriggs, M., and Erritzoe, D. (2022). Psychedelics therapeutics: what we know, what we think, and what we need to research. Neuropharmacology 223:109257. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109257

O’Brien, K. M., and Vincent, N. K. (2003). Psychiatric comorbidity in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: nature, prevalence, and causal relationships. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 23, 57–74. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00201-5

PAC (2022). PAC - Code of Ethics. Available online at: https://www.psychedelicassociation.net/code-of-ethics (accessed November 14, 2022).

Pachter, L. M., Caldwell, C. H., Jackson, J. S., and Bernstein, B. A. (2018). Discrimination and mental health in a representative sample of African-American and Afro-caribbean youth. J. Racial. Ethn. Health Disparities 5, 831–837. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0428-z

Peluso, D., Sinclair, E., Labate, B., and Cavnar, C. (2020). Reflections on crafting an ayahuasca community guide for the awareness of sexual abuse. J. Psychedelic Stud. 4, 24–33. doi: 10.1556/2054.2020.00124

Petranker, R., Anderson, T., and Farb, N. (2020). Psychedelic research and the need for transparency: polishing Alice’s looking glass. Front. Psychol. 11:1681. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01681

Phelps, J. (2017). Developing guidelines and competencies for the training of psychedelic therapists. J. Humanist Psychol. 57, 450–487. doi: 10.1177/0022167817711304

Phelps, J., Shah, R. N., and Lieberman, J. A. (2022). The rapid rise in investment in psychedelics—cart before the horse. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 189–190. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3972

Pilecki, B., Luoma, J. B., Bathje, G. J., Rhea, J., and Narloch, V. F. (2021). Ethical and legal issues in psychedelic harm reduction and integration therapy. Harm. Reduct. J. 18, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00489-1

Psymposia and New York Magazine Cover Story (Power Trip). (2022). Available online at: https://www.psymposia.com/powertrip/ (accessed April 15, 2023).

Rea, K., and Wallace, B. (2021). Enhancing equity-oriented care in psychedelic medicine: utilizing the EQUIP framework. Int. J. Drug Policy 98:103429. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103429

Read, T., and Papaspyrou, M. (eds) (2021). Psychedelics and Psychotherapy: the Healing Potential of Expanded States. Vermont: Park Street Press.

Reiff, C. M., Richman, E. E., Nemeroff, C. B., Carpenter, L. L., Widge, A. S., Rodriguez, C. I., et al. (2020). Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 391–410. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010035

Schenberg, E. E. (2018). Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: a paradigm shift in psychiatric research and development. Front. Pharmacol. 9:733. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00733

Schwarz-Plaschg, C. (2022). Socio-psychedelic imaginaries: envisioning and building legal psychedelic worlds in the United States. Eur. J. Futur. Res. 10, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40309-022-00199-2

Shim, R., Koplan, C., Langheim, F. J., Manseau, M. W., Powers, R. A., and Compton, M. T. (2014). The social determinants of mental health: an overview and call to action. Psychiatr. Ann. 44, 22–26. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20140108-04

Smith, W. R., and Appelbaum, P. S. (2022). Novel ethical and policy issues in psychiatric uses of psychedelic substances. Neuropharmacology 216:109165. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2022.109165

Smith, W. R., and Sisti, D. (2020). Ethics and ego dissolution: the case of psilocybin. J. Med. Ethics [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106070

Stephan, K. E., Bach, D. R., Fletcher, P. C., Flint, J., Frank, M. J., Friston, K. J., et al. (2016). Charting the landscape of priority problems in psychiatry, part 1: classification and diagnosis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00361-2

Strauss, D., de la Salle, S., Sloshower, J., and Williams, M. T. (2022). Research abuses against people of colour and other vulnerable groups in early psychedelic research. J. Med. Ethics 48, 728–737. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2021-107262

Thal, S. B., Bright, S. J., Sharbanee, J. M., Wenge, T., and Skeffington, P. M. (2021). Current perspective on the therapeutic preset for substance-assisted psychotherapy. Front. Psychol. 12:617224. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617224

Watt, G. (2018). The inverse care law revisited: a continuing blot on the record of the national health service. Br. J. General Practice 68, 562–563. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X699893

Weich, S., Lewis, G., and Jenkins, S. P. (2001). Income inequality and the prevalence of common mental disorders in Britain. Br. J. Psychiatry 178, 222–227. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.222

Williams, K., Romero, O. S. G., Braunstein, M., and Brant, S. (2022). Indigenous philosophies and the ‘Psychedelic Renaissance’. Anthropol. Conscious. 33, 506–527. doi: 10.1111/anoc.12161

Williams, M. L., Korevaar, D., Harvey, R., Fitzgerald, P. B., Liknaitzky, P., O’Carroll, S., et al. (2021). Translating psychedelic therapies from clinical trials to community clinics: building bridges and addressing potential challenges ahead. Front. Psychiatry 12:737738. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.737738

Williams, M. T., Reed, S., and Aggarwal, R. (2020). Culturally informed research design issues in a study for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychedelic Stud. 4, 40–50. doi: 10.1556/2054.2019.016

Williams, M. T., Reed, S., and George, J. (2021). Culture and psychedelic psychotherapy: ethnic and racial themes from three black women therapists. J. Psychedelic. Stud. 4, 125–138. doi: 10.1556/2054.2020.00137

World Health Organization (2022). World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All. Geneva: WHO.

Wortzel, J. R., Turner, B. E., Weeks, B. T., Fragassi, C., Ramos, V., Truong, T., et al. (2020). Trends in mental health clinical research: characterizing the ClinicalTrials.gov registry from 2007–2018. Naudet F, editor. PLoS One 15:e0233996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233996

Yaden, D. B., Yaden, M. E., and Griffiths, R. R. (2021). Psychedelics in psychiatry—keeping the renaissance from going off the rails. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 469–470. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3672

Yockey, A., and King, K. (2021). Use of psilocybin (“mushrooms”) among US adults: 2015–2018. J. Psychedelic Stud. 5, 17–21. doi: 10.1556/2054.2020.00159

Keywords: psychedelic assisted therapy (PAT), ethics, equity, co-design, psychotherapy

Citation: Spriggs MJ, Murphy-Beiner A, Murphy R, Bornemann J, Thurgur H and Schlag AK (2023) ARC: a framework for access, reciprocity and conduct in psychedelic therapies. Front. Psychol. 14:1119115. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1119115

Received: 08 December 2022; Accepted: 31 March 2023;

Published: 11 May 2023.

Edited by:

Marina Weiler, California State University, Los Angeles, United StatesReviewed by:

Peter Schuyler Hendricks, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Spriggs, Murphy-Beiner, Murphy, Bornemann, Thurgur and Schlag. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anne K. Schlag, YW5uZS5zY2hsYWdAZHJ1Z3NjaWVuY2Uub3JnLnVr

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.