- School of International and Public Affairs, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Introduction: Despite the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction is widely discussed, rare studies explore the theoretical mechanism of this relationship.

Methods: Through integrating public service motivation, role overload, job satisfaction, and marital status, this study explores psychological mechanisms and boundary conditions of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction. Data was collected from 349 public employees in eastern China.

Results: Empirical results reveal that public service motivation is positively related to job satisfaction by decreasing role overload. Moreover, marital status moderates the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction, as well as moderates the indirect effect of public service motivation on job satisfaction through role overload.

Discussion: These findings advance our understanding of the psychological mechanism and conditional effect of PSM in relation to job satisfaction and provide valuable insights into how to improve public employees’ well-being.

1. Introduction

Since introduced by Perry and Wise (1990), public service motivation (PSM) has attracted growing attention from scholars and practitioners, which is considered an important antecedent of work attitudes and behaviors, such as job satisfaction (e.g., Liu et al., 2008; Homberg et al., 2015), organizational commitment (Crewson, 1997; Sun, 2021), performance (Bellé, 2013; Andersen et al., 2014), change-supportive behavior (Hassan et al., 2021), and organizational citizenship behavior (Liu and Perry, 2016; Chen et al., 2021). This study focuses on the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. As the most frequently studied outcome of PSM, job satisfaction is of great interest. On the one hand, job satisfaction can predict employee well-being and is associated with health variables such as burnout, depression, and anxiety (Faragher et al., 2013; Di Marco et al., 2016). Also, from the humanitarian perspective, happiness or satisfaction is a permanent theme of life, and job satisfaction is a measure of “happiness at work,” which is worth pursuing in itself (Brown et al., 2012).

Nevertheless, the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction shows mixed or conflicting results. On the one hand, public employees who possess a high level of PSM are more likely to feel value consistency with their organization, perceive a high level of person-organization fit, devote themselves to public service and easily find job enjoyment, thus PSM will be positively linked to job satisfaction (Liu et al., 2008; Quratulain and Khan, 2015; Roh et al., 2016; Li et al., 2022). Meta-analysis of the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction also presents a positive relationship (Homberg et al., 2015). On the other hand, some scholars proposed that PSM might have dark sides, suggesting that employees with high PSM are prone to work overload, perceive more work stress, and suffer their well-being (Giauque et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015a,b; Van Loon et al., 2015). Meanwhile, scholars have also found a non-direct or non-significant relationship between PSM and job satisfaction (Wright and Pandey, 2008, 2011; Rayner et al., 2018).

Moreover, previous research usually focuses on the direct relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. Only a handful of studies have explored the psychological process and conditional effect of these two constructs. For instance, scholars have studied the mediating effect of value congruence (Wright and Pandey, 2008), mission valence (Wright and Pandey, 2011), emotional labor strategy (Li and Wang, 2016), organizational commitment (Park, 2020), perception of organization prestige (Bright, 2021), as well as the moderating effect of love of money (Liu and Tang, 2011), person-organization fit and needs-supplies fit (Liu et al., 2015a,b). It can be seen that the extent of studies on the theoretical mechanism between PSM and job satisfaction is limited and mostly carried out from the perspective of person-organization fit.

To address the research gap, our study aims to replicate and retest the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction in the Chinese public sector and to expand previous literature by examining a moderated mediation model. Based on the Job Demands-Resources model, job characteristics can be divided into two categories: job demands and job resources. Their interaction plays a vital role in the development of job strain (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007). PSM belongs to personal resources, and public employees with high PSM can better cope with tremendous job demands (Giauque et al., 2013; Bakker, 2015). Role overload occurs when employees feel insufficient resources to fulfill assigned requirements, commitments, or obligations (Peterson et al., 1995). When faced with tremendous work demands, we argue that highly motivated public employees possess high person-organization fit, feel more support and resources, therefore, are less prone to role overload, and have a high level of job satisfaction. Meanwhile, Chinese public employees describe their work situation as “A thousand threads from above, one needlepoint below.” Role overload has been a prominent and imperative issue in the Chinese public sector and significantly influences employees’ well-being (Liu et al., 2015a,b). Hence, this study will empirically examine the mediating effect of role overload between PSM and job satisfaction. Family roles could interact with work roles. Marital status, as a valued life condition in the family role (Hobfoll, 1989), can provide resources for the work domain (Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012). Simultaneously, married employees might face increasing demand at home and require more energy and time (Vatharkar and Aggarwal-Gupta, 2020). Thus, marriage may affect employees’ perception of role overload and its influence on employees’ well-being (Byron, 2005). However, the impact of marriage may vary by national context. Traditional Chinese family values constitute the context of marital life (Hu and Scott, 2016). For example, the wife is thought to be the primary housework role due to traditional gender roles, and family members across different generations tend to live together because of filial piety (Shek, 2006). It is necessary to investigate the conditional effect of marital status in Chinese context.

Through examining the aforementioned relationships, this study has a twofold contribution. Firstly, this study has examined the mediating effect of role overload in the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction, advancing the knowledge of the psychological mechanism of PSM in relation to job satisfaction. Role stress, like role ambiguity and conflict, has received extensive attention, and less attention has been paid to role overload (Örtqvist and Wincent, 2006). To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to empirically test the relationship between PSM and role overload, which enriches the literature on role overload. Secondly, this study explores the moderation effect of marital status and reveals that marriage plays a buffering effect. Through deepening understanding of resources in both work and family domains, this study contributes to the development of role stress theory and provides insights to improve employees’ job satisfaction.

2. Literature review and theoretical hypothesis

2.1. Public service motivation and job satisfaction

Job satisfaction is viewed as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke, 1976). It is believed that highly satisfied employees tend to possess higher organizational commitment (Aydogdu and Asikgil, 2011), have lower turnover rates (Zhang et al., 2022), perform more organizational citizenship behavior (Zeinabadi, 2010), as well as higher job performance (Judge et al., 2001). Nowadays, public sectors are faced with an increasingly volatile environment, and they have to improve employees’ productivity to meet the public service needs of citizens under the circumstance of personnel cutbacks and budget constraints (Piatak, 2019; Liu, 2020; Ahmad et al., 2021). Maintaining employees’ job satisfaction is one of the prerequisites for improving organizational effectiveness and providing high-quality public service (Cantarelli et al., 2016). However, public employees have low job satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2005). Thus, it is necessary and imperative to understand how to improve public employees’ job satisfaction effectively. Previous studies have explored a range of antecedent variables that affect job satisfaction, and scholars in the field of public administration have paid much attention to PSM. PSM is characterized as motives and actions rooted in the public sector to do good for others and the whole society (Perry and Hondeghem, 2008), which consists of four dimensions: attraction to policy making, commitment to the public interest, compassion, and self-sacrifice (Perry, 1996). Research on PSM has been widespread and has reached a consensus on the positive effects of PSM on work attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Liu and Perry, 2016; Ritz et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2021). Many studies have shown that employees with high PSM tend to be more satisfied with their jobs (Naff and Crum, 1999; Bright, 2008, 2021; Andersen and Kjeldsen, 2013).

Following previous research (Bright, 2007, 2021; Wright and Pandey, 2008, 2011), the P-O fit theory is widely used to explain the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. P-O fit theory assumes that when the congruence between individuals and their organizations increases, employees will have more positive work attitudes and behaviors, such as job satisfaction (Kristof, 1996). In contrast to colleagues with lower PSM, public employees with higher PSM have more tolerance of bureaucratic characteristics, have more excellent compatibility with public organizations, and perceive that the work environment can meet their values, needs, and interests (Scott and Pandey, 2005). It has been proven that PSM can predict P-O fit significantly, leading to higher job satisfaction (Bright, 2007; Teo et al., 2016; Prysmakova and Vandenabeele, 2020). Previous studies have also demonstrated that employees with high PSM will identify more with the public sector (Liu and Perry, 2016) and have a high organizational commitment (Park, 2020), which leads to more job satisfaction. Otherwise, the motivational theory posits that PSM can help public employees find more job enjoyment and express greater satisfaction in daily work (Liu et al., 2008). All these arguments stand to reason that PSM is positively linked to job satisfaction.

Despite the aforesaid positive relationship between PSM and job satisfaction, there are still some inconsistencies in the literature. Based on a survey of 455 council workers in Australia, Rayner et al. (2018) reported a non-significant relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. Considering the “too-much-of-good-thing” effect, several studies proposed that PSM might negatively influence job satisfaction. For example, in people-changing organizations, employees with strong social impact potential would be willing to do too much and overreach individual resources, leading to less satisfaction (van Loon et al., 2015). Meanwhile, the relationship between PSM and tenure also provides supporting evidence. If PSM is positively associated with job satisfaction, then highly satisfied employees are more likely to work longer in public organizations, which conflicts with the negative empirical results between tenure and job satisfaction (Naff and Crum, 1999; Moynihan and Pandey, 2007; Liu and Perry, 2016). Consistent with the rationale of the P-O fit theory, we believe that PSM predicts job satisfaction positively rather than vice versa. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: PSM has a positive effect on job satisfaction.

2.2. The mediating effect of role overload

Role stress refers to the disparity between perceived role expectations and the actual accomplishments in the role (Lambert and Lambert, 2001), which comprises three facets: role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload (Abdel-Halim, 1981). Role overload has received less attention than role conflict and ambiguity, which have been well-studied (Örtqvist and Wincent, 2006). Role overload depicts situations where employees lack time and resources to complete assigned requirements, commitments, or obligations (Peterson et al., 1995). When it occurs to the relationship between PSM and role overload, the Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R model, Bakker and Demerouti, 2007) can shed some light. PSM can be viewed as job resource which can help public employees cope with tremendous job demands (Giauque et al., 2013). As PSM increases, employees have more personal resources, feel the balance between job demands and resources, and thus are less likely to feel role overload. Otherwise, it has been proven that PSM is positively linked to person-organization fit (Bright, 2007, 2021; Kim, 2012). That is to say, public employees with high PSM tend to feel a high person-organization fit, perceive organizational support, and are inclined to experience less risk of role overload.

PSM can make employees feel more satisfied with their job by decreasing their perception of role overload. From the perspective of the JD-R model, employees who experience role overload will consume their psychological and physiological resources, resulting in decreased well-being, such as job satisfaction. The relationship between role overload and job satisfaction has been widely discussed and reported negative correlations (e.g., Fox et al., 1993; Yousef, 2002; Jones et al., 2007). For instance, based on a survey of 442 public employees, Pecino et al. (2019) reported a significant and negative relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. Meta-analysis integrating nine studies with 2,199 respondents also demonstrated a significant negative relationship between role overload and job satisfaction (Örtqvist and Wincent, 2006). The work–family literature also sheds some light on the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. Role overload is modeled as an important antecedent of work–family conflict (Duxbury et al., 2021). And work–family conflict can predict low job satisfaction (Bruck et al., 2002). With the increasing nonwork demands like having a toddler and caring for an elder, employees are more likely to experience role overload and perceive work–family conflict, which in turn damages work attitudes and behaviors (Duxbury et al., 2008). In addition, role overload has a negative relationship with work-family enrichment, which can also lead to low job satisfaction (Lapierre et al., 2018).

As stated above, we propose a negative relationship between PSM and role overload and a negative relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. The previous study has pointed out that the impact of personal or organizational resources on employees’ attitudes and behaviors was usually mediated by role overload (Gurbuz et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2020). Thus, we posit that role overload is an important mediator in the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. PSM can help employees balance out job demands and resources (Bright, 2007, 2021; Kim, 2012; Giauque et al., 2013), then employees will perceive less role overload and, in turn, enhance the level of job satisfaction. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Role overload mediates the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction.

2.3. The moderating effect of marital status

Every individual in society plays multiple roles simultaneously, with work and family roles being the most common roles (Grandy et al., 2005). Personal resources are assumed to be finite. If resources used in one role are depleted, they cannot be used in other roles (Edwards and Rothbard, 2000). Marital status, as a valued life condition in family role (Hobfoll, 1989), has a double-edged nature. On the one hand, in contrast to unmarried employees, married employees usually play more roles. They need to consume more resources to cope with increasing family demands, which may sap time and energy that could be used in the work domain and experience a lower level of job satisfaction. Extant research proposed that due to the shift of resources from work to family, marital status was positively related to work–family conflict (Byron, 2005; Vatharkar and Aggarwal-Gupta, 2020), which may negatively predict job satisfaction (Bruck et al., 2002; Grandy et al., 2005).

On the other hand, when employees are experiencing negative impacts because of a loss of resources in one domain, resources from other domains can mitigate the negative effects (Taris et al., 2001). Marriage can also be regarded as an important form of resources in family context (Hobfoll, 1989), and can shift valued resources to one’s work life (Ten Brummelhuis and Bakker, 2012). Faced with a high level of role overload, married employees could communicate with their spouses to get emotional or verbal appreciation, or perceive helpful advice, thus relieving work tension (Greenhaus et al., 2012). With the increasing commonness of dual-career families (Elloy and Smith, 2004), husband and wife usually share housework. When one of them is busy with work, the other typically takes up more chores, which gives employees a high work-life balance and helps them better deal with challenges at work. Meanwhile, marriage may impose more responsibilities and make employees prefer stable jobs. And they tend to take measures to cope with or adjust unsatisfactory aspects of their work (Azim et al., 2013). It has been proven that married employees enjoyed a higher level of job satisfaction than their single coworkers (Austrom et al., 1988; Azim et al., 2013; Olatunji and Mokuolu, 2014). Previous studies have demonstrated that marital status moderated the effect of role overload on its outcomes by providing additional resources. For example, marital status played moderating role in the relationship between role overload and work engagement (Kim et al., 2018), as well as the relationship between role overload and the work-family interface (Vatharkar and Aggarwal-Gupta, 2020).

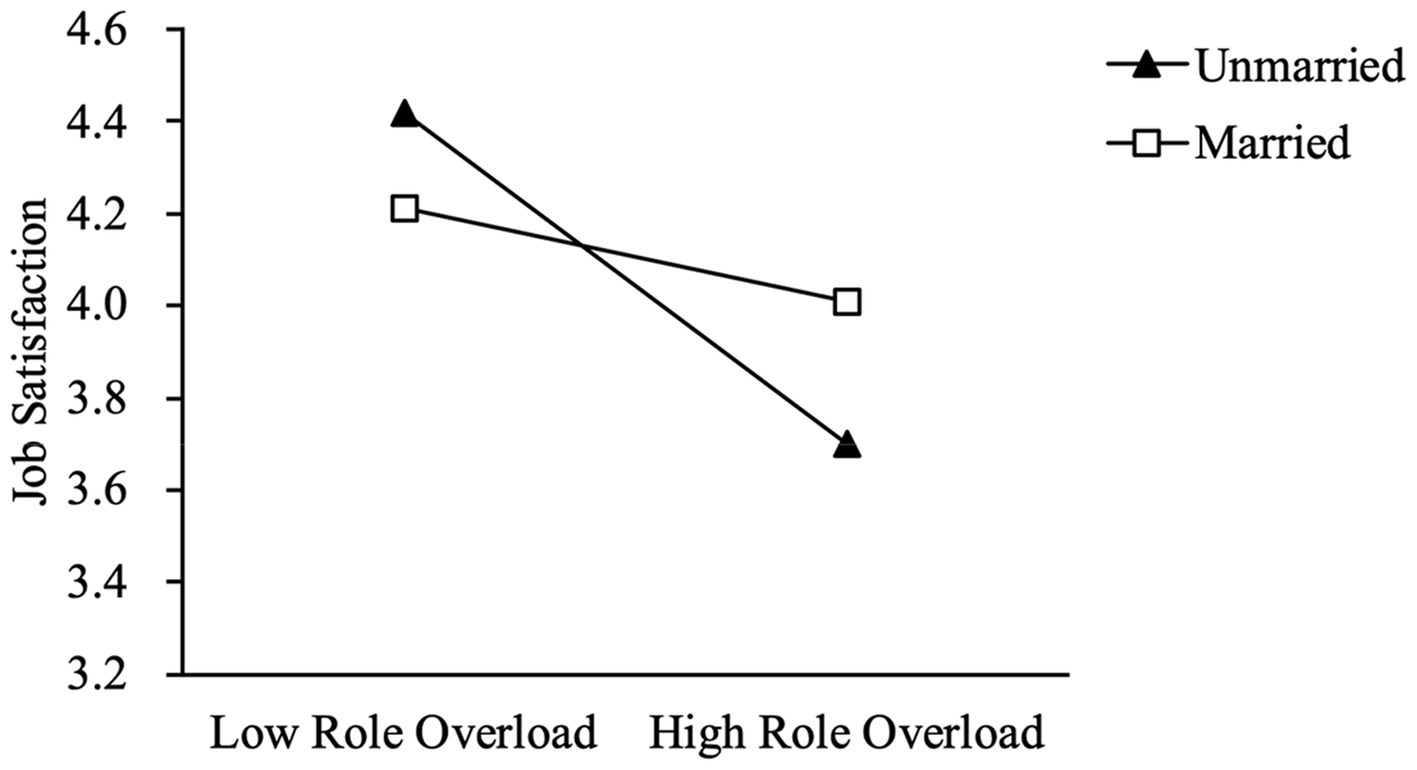

Thus, we posit that marital status plays a buffering role in the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. Specifically, in low role overload, married employees may face additional demands from family life and be less satisfied with their jobs than unmarried employees. In high role overload, married employees may derive emotional support from spouses, do less housework, take the initiative to adjust or adapt unsatisfactory facets to get a steady job, and thus be more satisfied with their jobs than unmarried employees. These lead us to:

Hypothesis 3: Marital status moderates the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction in that marital status attenuates the negative effect of increasing role overload.

The above three hypotheses imply an indirect effect of PSM on job satisfaction through role overload, and marital status moderates the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. Synthesizing the above arguments and hypotheses, we propose a moderated mediation model in which the indirect relationship between PSM and job satisfaction via role overload depends on marital status. Thus, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4: Marital status moderates the indirect effect of PSM on job satisfaction through role overload; specifically, the relationship is weaker for married public employees than unmarried public employees.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

This study collected data from public employees in a medium city in eastern China. With the help of the administration department, we distributed anonymous questionnaires to public employees from various departments, including education, personnel, health, and so on. And they were also informed it is voluntary to join the survey. A total of 500 questionnaires were distributed, and 349 valid questionnaires were obtained after excluding missing data, with a response rate of 69.8%. Among 349 respondents, 40.97% were male, and 59.03% were female. The average age was 35.33. In terms of education level, 74.5% got a bachelor’s degree, and 10.32% got a master’s degree and above. For marital status, 23.78% were unmarried, and 76.22% were married.

3.2. Measures

All key variables were measured using Likert five-point scales, ranging from 1 to 5, indicating “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

3.2.1. Public service motivation

This variable was measured by an 18-item scale developed by Liu and Perry (2016), which was validated in the Chinese public sector context. A sample item was “Meaningful public service is very important to me.” The Cronbach’s α for public service motivation was 0.97.

3.2.2. Role overload

Five-item scale developed by Peterson et al. (1995) was used to capture role overload. A representative item was “My workload is heavy.” The Cronbach’s α for role overload was 0.93.

3.2.3. Job satisfaction

This variable was measured by a three-item scale developed by Bono and Judge (2003), which was revised and validated by Liu et al. (2008) in the Chinese context. A sample item was “I feel fairly satisfied with my present job.” The Cronbach’s α for job satisfaction is 0.96.

3.2.4. Marital status

It was measured with one item that asked respondents about their marital status (unmarried = 1, married = 2).

Following previous research (e.g., Liu and Perry, 2016; Sun, 2021), this study controlled demographic variables, including gender (male = 1, female = 2), age, education (college and below = 1, bachelor =2, master and above = 3), and organizational tenure (in years).

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary analysis

Before hypothesis testing, this study did some preliminary analysis. Firstly, since our data was self-reported data collected at one time, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to examine common method bias (CMB). Four factors were drawn, and the first factor explained 30.75% of the total variance, which did not account for most of the variance, implying that CMB wasn’t a substantial concern (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

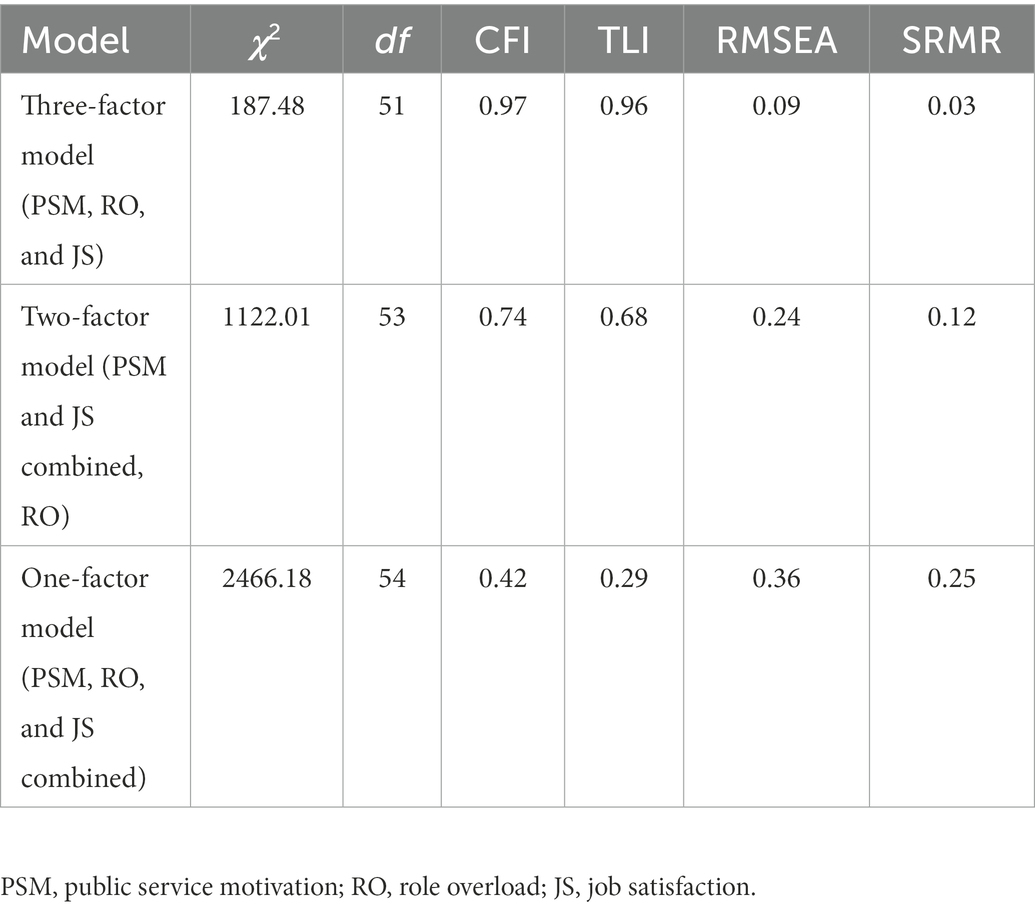

Table 1 presents the result of the confirmatory factor analysis. The results demonstrate that the three-factor model (public service motivation, role overload, and job satisfaction) fits well with the data (χ2 = 187.48, df = 51, χ2/df = 3.68, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.09, SRMR = 0.03). It performs better than the two-factor and one-factor models on all fitting indicators, indicating that the three constructs have good structural validity.

4.2. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

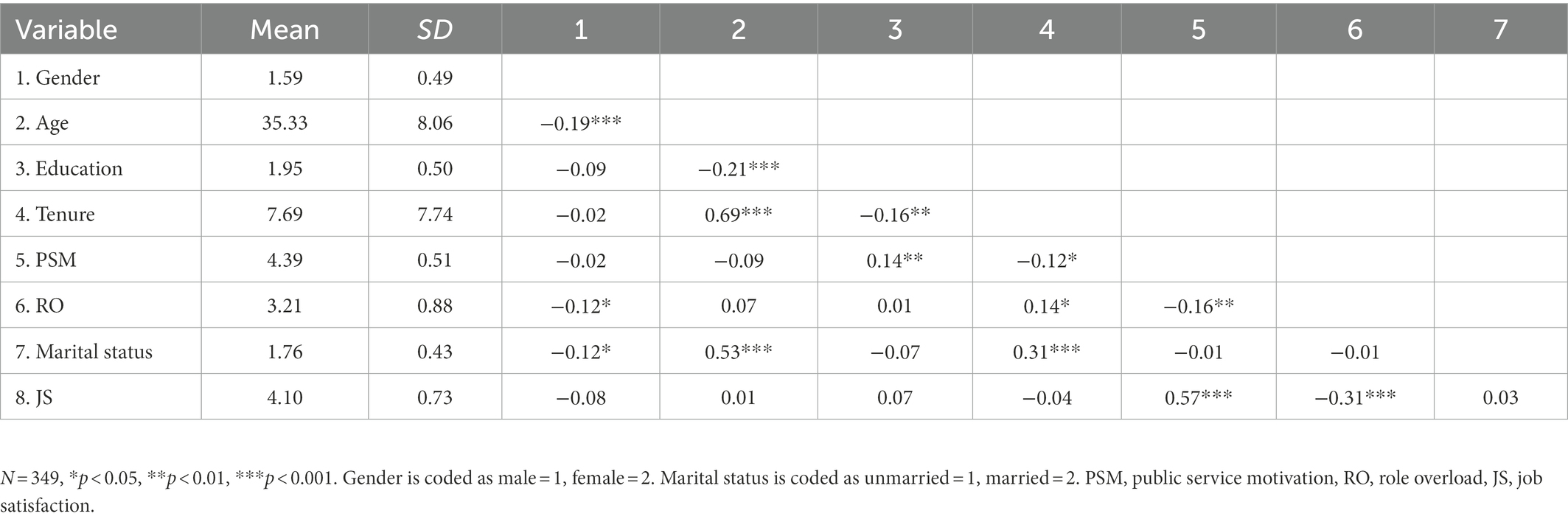

Table 2 reports the research variables’ means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients. According to the results of Table 2, public service motivation is positively correlated with job satisfaction (r = 0.57, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with role overload (r = −0.16, p < 0.01). Table 2 also shows that the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction is significantly negative (r = −0.31, p < 0.001). Thus, correlations between main variables provide initial support for research hypotheses.

4.3. Hypothesis testing

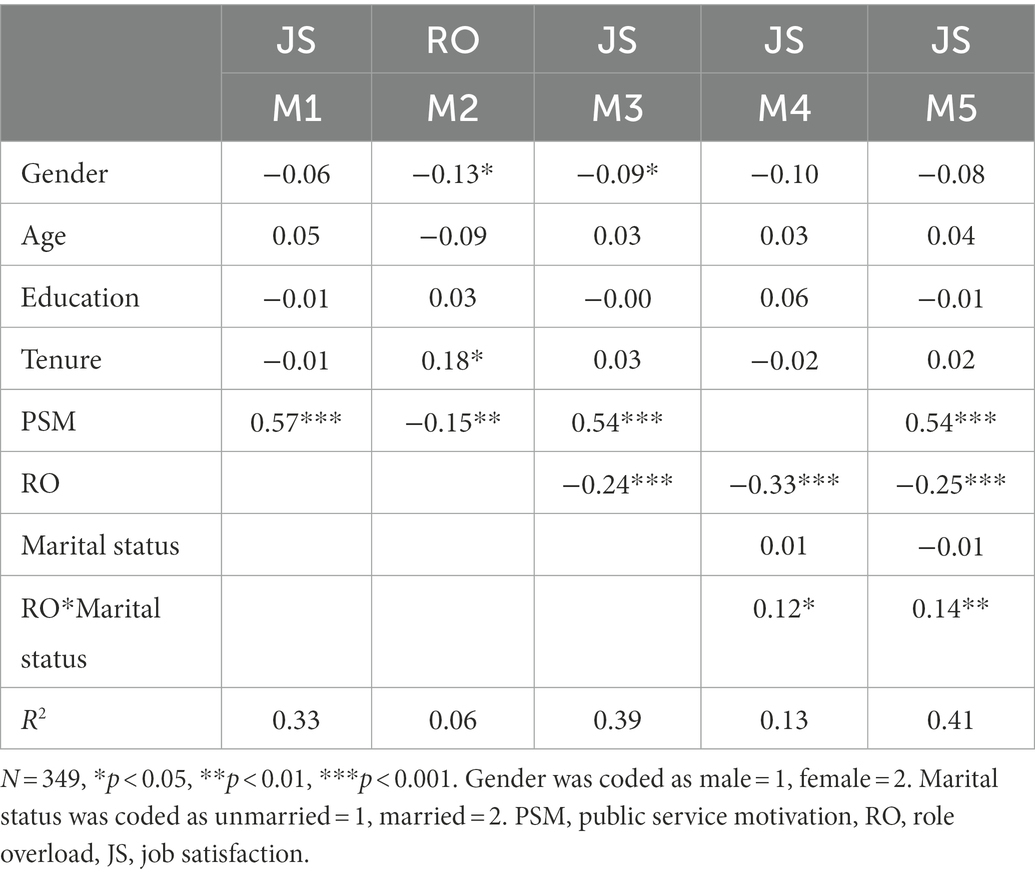

Table 3 shows the results of the regression analysis. Model 1 has controlled demographic variables to test the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. The results show that PSM positively affects job satisfaction (β = 0.57, p < 0.001) and explains 33% of the variance. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported.

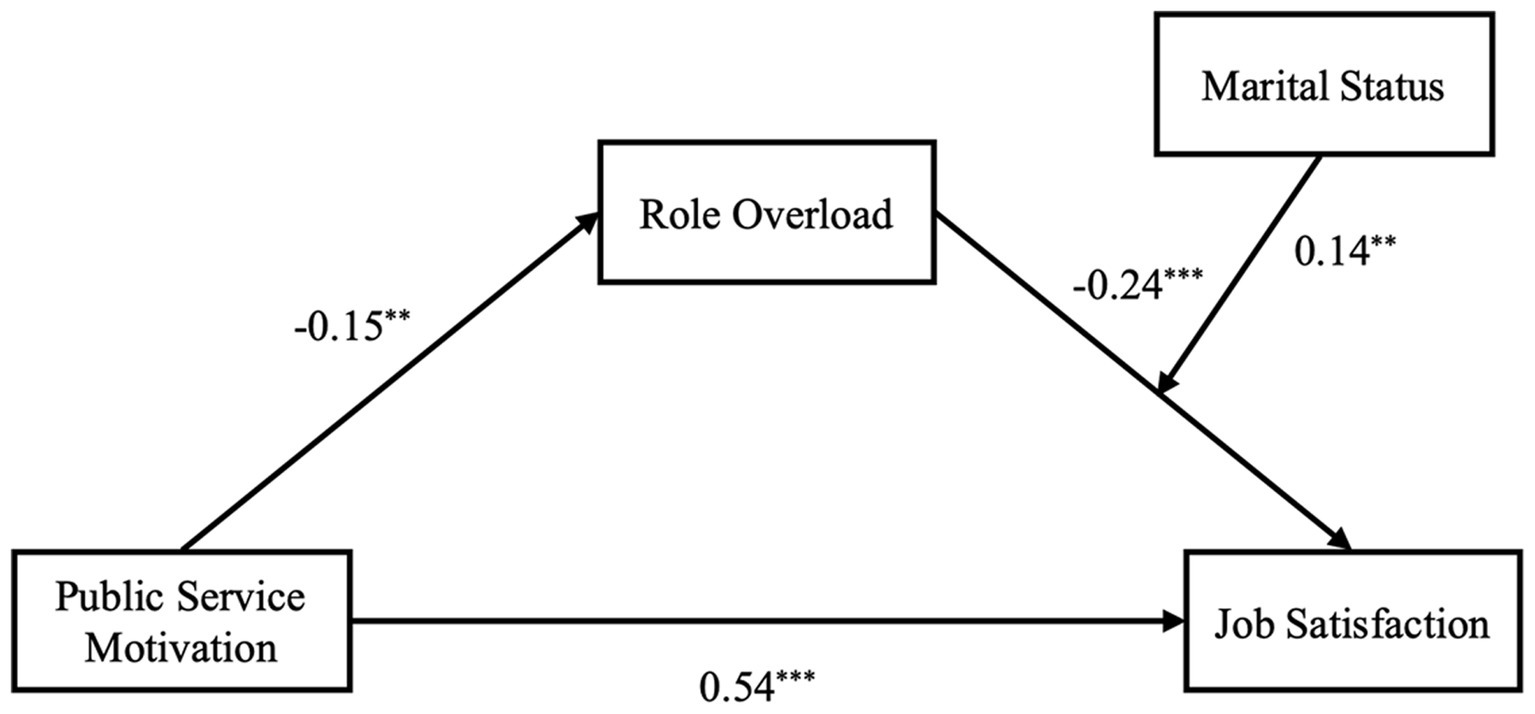

Then, following Baron and Kenny’s (1986) recommended procedures, Models 2 and 3 are employed to test the mediation effect. As model 2 shows, PSM is negatively associated with role overload (β = −0.15, p < 0.001). Model 3 adds role overload based on Model 1. The results demonstrate a significantly negative effect of role overload on job satisfaction (β = −0.24, p < 0.001), and PSM is still positively associated with job satisfaction (β = 0.54, p < 0.001). The inclusion role overload explains 6% of the variance for job satisfaction (from Model 1 (R2 = 0.33) to Model 3 (R2 = 0.39)). Hypothesis 2 is supported.

Model 4 includes the interaction term between role overload and marital status to test the moderation effect of marital status on the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. The results report that the interaction term is positively associated with job satisfaction (β = 0.12, p < 0.05) and explains 13% of the variance. Hypothesis 3 is supported. Model 5 includes the interaction term to Model 3 to test Hypothesis 4. The results show that the interaction term is positively associated with job satisfaction (β = 0.14, p < 0.01), which explains 2% of the variance for job satisfaction (Model 3 (R2 = 0.39) to Model 5 (R2 = 0.41)). Hypothesis 4 is supported. Figure 1 displays the moderation effect of marital status on the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction. As Figure 1 shows, the slope of unmarried employees is negative and steeper, implying that the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction is negative and intense. In contrast, the slope of married employees is negative and flatter. Specifically, when employees are faced with a higher level of role overload, married employees will experience a higher level of job satisfaction than unmarried employees.

Figure 1. The moderating effect of marital status on the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction.

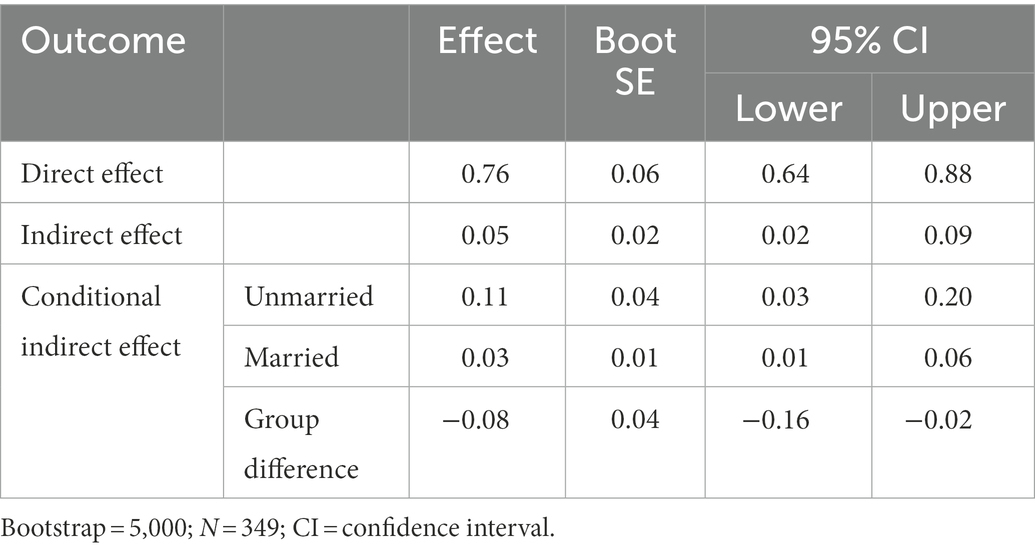

To further examine the Hypothesis more rigorously, we perform bootstrapping analysis with PROCESS macro for SPSS. Table 4 shows the results of the mediation effect and the moderated mediation effect. Model 4 in PROCESS is used to test the mediation effect, and Model 14 in PROCESS is used to examine the moderated mediation effect. As Table 4 shows, the indirect impact of PSM on job satisfaction through role overload is significant, with 95% CI [0.02, 0.09]. And 95% direct CI is [0.64, 0.88], excluding zero. Thus, role overload partially mediates the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. Hypothesis 2 is supported.

The results of the conditional indirect effect of marital status are also displayed. For unmarried public employees, the indirect effect of PSM on job satisfaction does not include zero, 95% CI is [0.03, 0.20], implying a significant indirect effect. For married public employees, the indirect effect of PSM on job satisfaction also does not include zero, 95% CI is [0.01, 0.06], implying the indirect effect is significant. And the moderated mediation effect (difference between two groups) is significant, with 95% CI [−0.16, −0.02]. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Figure 2 presents the results of the proposed moderated mediation model.

5. Discussion

With increasing efficiency and high-quality requirements for the public sector, how to improve public employees’ job satisfaction has been a critical theoretical and practical issue (Cantarelli et al., 2016). Although scholars have extensively examined the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction, little attention has been paid to its psychological mechanism and boundary condition. This study confirms the positive relationship between PSM and job satisfaction and examines the mediating effect of role overload and the moderating effect of marital status. The findings of this study provide both theoretical and practical implications.

5.1. Theoretical implication

Firstly, this study advances the development of public service motivation theory. Previous studies have widely examined the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction, leading to contradictory results (e.g., Naff and Crum, 1999; Van Loon et al., 2015; Rayner et al., 2018). In line with previous findings (Liu et al., 2008; Liu and Tang, 2011), we confirm a positive direct relationship between PSM and job satisfaction based on an investigation among 349 Chinese public employees. Meanwhile, compared to vast attention on the relationship between PSM and two kinds of role stress, role ambiguity and role conflict, little attention has been paid to the relationship between PSM and role overload. Only Gould-Williams et al. (2014) took civic duty as a primary component of PSM and investigated the relationship between work overload and civic duty. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first empirical research to examine the relationship between PSM and role overload. It demonstrates that employees with high PSM are inclined to perceive role overload. Some studies conflict with our findings. Scholars propose that high PSM employees might fully engage in their work, perform extra-role behavior (Bolino and Turnley, 2005; Giauque et al., 2013), which requires additional time and energy, and thus are more prone to role overload. Lin and Ling (2018) thought that role overload belonged to challenge stress, which is positively associated with PSM (Deng et al., 2019, 2021). Thus, future research should further explore the relationship between PSM and role overload, such as the curvilinear relationship.

Secondly, this study has enriched the mediating variables between PSM and job satisfaction. Although previous studies have examined some potential mediators in the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction (Wright and Pandey, 2008, 2011; Li and Wang, 2016; Park, 2020; Bright, 2021), rare studies were carried out from the perspective of role overload. Noteworthy, the results of our research show that role overload only partially mediated the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. Future research, therefore, should explore more mediators. Role overload can be split into two types: quantitative role overload and qualitative role overload (Yousef, 2002). The former refers to time limitation; the latter emphasizes a lack of ability, skill, and knowledge. Two kinds of role overload should be taken into account in future research. In addition, this study only focuses on the impact of role overload on the work domain. Employees who perceive role overload may bring work home and occupy personal time they could spend with family, which certainly influences the family domain (Carnes, 2017). Previous studies claimed dynamic spillover between work satisfaction and marriage satisfaction (Heller and Watson, 2005). Thus, future research could examine the impact of role overload on the family domain.

Thirdly, this study depicts the boundary condition and incorporates the work and family domains by examining the moderating effect of marital status. Although married employees can drain resources from their family domain, there is still a negative relationship between role overload and job satisfaction, implying that the amount of resources marriage provides is limited (Lapierre et al., 2018). In addition, the demands of the family domain are complex and changeable in the Chinese context. According to the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2011–2012, about one-third of Chinese families are multi-generational co-residence which implies that Chinese families are faced with more demands like caring for the elder (Xie, 2013). Having a toddler can also limit the resources employees can get from their families. Families with children under 6 years old have been found to report more family–work conflict (Bennett et al., 2017). Moreover, males and females are considered to play different roles in traditional Chinese culture. For instance, the husband is usually perceived as a breadwinner, and the wife is thought to deal with housework. Some scholars suggested that the wife may experience higher work–family conflict than the husband do (Wharton and Blair-Loy, 2006). Interestingly, the increase in education has eroded traditional gender values (Hu and Scott, 2016). Therefore, future research should control the influence of the national context.

5.2. Practical implication

First of all, this study confirmed that public employees with high PSM were more satisfied with their jobs, which raised the importance of cultivating PSM in the public sector. As a low-cost driver of job satisfaction (Homberg et al., 2015), PSM could be cultivated in various ways. For example, the public organization can implement standard tests to select individuals with high PSM and facilitate workplace trust to enhance public employees’ PSM (Paarlberg et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2021). Public organizations should also provide opportunities to serve the public, which was considered to enhance the positive effect of PSM on job satisfaction (Homberg et al., 2015). However, it is worth noting that PSM is not a panacea for high job satisfaction (Bright, 2008). Previous studies have proved that PSM might have a dark side, lead to “resigned satisfaction,” work stress, unethical behavior, and so on (Giauque et al., 2012, 2013; Liu et al., 2015a,b; Ripoll and Schott, 2020).

The findings of this study show that role overload partially mediated the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction, suggesting that public employees’ job satisfaction can be increased by eliminating role overload. Extant research has provided many management insights to decrease role overload. It is proved that leader-member exchange quality can offer additional resources to public employees and negatively predicts role overload (Tordera et al., 2008). Thus, Public organizations should take measures to cultivate high-quality relationships between leaders and employees. And total quality management (TQM) practice, like encouraging employees to involve in the decision-making process, can mitigate role overload (Ebrahimi et al., 2014). It has been proven that job involvement can buffer the negative effect of role overload (Allen et al., 2001).

Thirdly, our results show that marital status moderates the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction and the indirect relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. When employees are faced with high role overload, marriage can shift time and energy from the family domain to the work domain, help employees cope with tremendous demands, and increase their job satisfaction. But in the long run, the marriage hardly supplies resources sustainably, and growing marital discord may reduce job satisfaction (Rogers and May, 2003). Thus, it is vital to achieve a work-family balance. Thus, achieving work-family balance is vital, especially in enhancing positive spillover. Employees could gain resources like multiple-task skills, networking, and positive emotions from family lives, leading to higher job satisfaction (Greenhaus and Powell, 2006). Employees should cultivate a good family environment, like family cohesion and mutuality, which positively relates to positive family-to-work spillover (Carlson et al., 2006; Stevens et al., 2007). Meanwhile, public organizations should have formal institutional support to help employees balance work and family roles, such as flexible working arrangements, teleworking, time management training programs, and childcare facilities (McCarthy et al., 2010). Also, the public sector should foster family-supportive supervisor behaviors, which are essential social resources that can assist employees in managing demands from family and work and enhance employees’ well-being (Kossek et al., 2011).

5.3. Limitations and future research

Future research should address several limitations. First, data were collected from a convenience sample in a medium city in eastern China. It has been suggested that the relationship between PSM and its correlations may be influenced by cultural context (Houston, 2011; Rayner et al., 2018). And previous research also showed that the effect of role overload on organization commitment was contingent on power distance (Fisher, 2014). Future research should be conducted in larger samples to increase the generalizability of findings. The second limitation of this study is the cross-sectional design, which makes it challenging to clarify the causal relationship. Longitudinal or experimental research design is expected in future research. As well, all variables were self-reported. Future research could use different data sources, such as objective data, to decrease the risk of common method bias. Third, this study ignored the complexity of family domain demands and resources, such as the number of children, the need for elder care, and the complexity of marital status like unmarried cohabitation. Future research needs to consider different family compositions.

6. Conclusion

This study focused on the relationship between PSM and job satisfaction to investigate how to enhance public employees’ well-being effectively. Based on a survey of 349 public employees in eastern China, results showed that PSM had a significant positive effect on public employees’ job satisfaction and role overload plays a mediation role in their relationship. These findings not only respond to previous contradictory results and contribute to the development of role stress theory, but also advance the development of public service motivation theory by clarifying the psychological mechanism of PSM with job satisfaction and bringing insight into how PSM influences employees’ job satisfaction. Results also revealed that marital status played a moderation role in the relationship between role overload and job satisfaction and the indirect relationship between PSM and job satisfaction. Through depicting the boundary condition, marital status deepens our understanding of resources spillover between work and family domains. Under the imperative circumstance of increasing employees’ well-being, public organizations should select and foster PSM of employees, develop high Leader-member exchange quality and total quality management to eliminate role overload, and cultivate formal institutional support and family-supportive supervisor behaviors.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Project 20AZD020).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmad, A. B., Straatmann, T., Mueller, K., and Liu, B. (2021). Employees’ change support in the public sector—A multi-time field study examining the formation of intentions and behaviors. Public Admin. Rev. 81, 231–243. doi: 10.1111/puar.13275

Abdel-Halim, A. A. (1981). Effects of role stress-job design-technology interaction on employee work satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 24, 260–273. doi: 10.2307/255840

Allen, T. D., Freeman, D. M., Russell, J. E., Reizenstein, R. C., and Rentz, J. O. (2001). Survivor reactions to organizational downsizing: does time ease the pain? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 74, 145–164. doi: 10.1348/096317901167299

Andersen, L. B., Heinesen, E., and Pedersen, L. H. (2014). How does public service motivation among teachers affect student performance in schools? J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 24, 651–671. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mut082

Andersen, L. B., and Kjeldsen, A. M. (2013). Public service motivation, user orientation, and job satisfaction: a question of employment sector? Int. Public Manag. J. 16, 252–274. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2013.817253

Austrom, D. R., Baldwin, T. T., and Macy, G. J. (1988). The single worker: an empirical exploration of attitudes, behavior, and well-Being. Can. J. Admin. Sci. 5, 22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1936-4490.1988.tb00491.x

Aydogdu, S., and Asikgil, B. (2011). An empirical study of the relationship among job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 1, 43–53.

Azim, M. T., Haque, M. M., and Chowdhury, R. A. (2013). Gender, marital status, and job satisfaction an empirical study. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2, 488–498.

Bakker, A. B. (2015). A job demands–resources approach to public service motivation. Public Admin. Rev. 75, 723–732. doi: 10.1111/puar.12388

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bellé, N. (2013). Experimental evidence on the relationship between public service motivation and job performance. Public Admin. Rev. 73, 143–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02621.x

Bennett, M. M., Beehr, T. A., and Ivanitskaya, L. V. (2017). Work-family conflict: differences across generations and life cycles. J. Manag. Psychol. 32, 314–332. doi: 10.1108/JMP-06-2016-0192

Bolino, M. C., and Turnley, W. H. (2005). The personal costs of citizenship behavior: the relationship between individual initiative and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 740–748. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.740

Bono, J. E., and Judge, T. A. (2003). Self-concordance at work: toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Acad. Manag. J. 46, 554–571. doi: 10.2307/30040649

Bright, L. (2007). Does person-organization fit mediate the relationship between public service motivation and the job performance of public employees? Rev. Public Person. Adminis. 27, 361–379. doi: 10.1177/0734371X07307149

Bright, L. (2008). Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? Am. Rev. Public Admin. 38, 149–166. doi: 10.1177/0275074008317248

Bright, L. (2021). Does perceptions of organizational prestige mediate the relationship between public service motivation, job satisfaction, and the turnover intentions of federal employees? Public Person. Manag. 50, 408–429. doi: 10.1177/0091026020952818

Brown, A., Charlwood, A., and Spencer, D. A. (2012). Not all that it might seem: why job satisfaction is worth studying despite it being a poor summary measure of job quality. Work Employ. Soc. 26, 1007–1018. doi: 10.1177/0950017012461837

Bruck, C. S., Allen, T. D., and Spector, P. E. (2002). The relation between work–family conflict and job satisfaction: a finer-grained analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 60, 336–353. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1836

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. J. Vocat. Behav. 67, 169–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009

Cantarelli, P., Belardinelli, P., and Belle, N. (2016). A meta-analysis of job satisfaction correlates in the public administration literature. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 36, 115–144. doi: 10.1177/0734371X15578534

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Wayne, J. H., and Grzywacz, J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work–family interface: development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 68, 131–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.02.002

Carnes, A. M. (2017). Bringing work stress home: the impact of role conflict and role overload on spousal marital satisfaction. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 90, 153–176. doi: 10.1111/joop.12163

Chen, D., Zhang, Y., Ahmad, A. B., and Liu, B. (2021). How to fuel public employees’ change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: a two-wave moderated mediation study. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 43, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/0734371X211052675

Crewson, P. E. (1997). Public-service motivation: building empirical evidence of incidence and effect. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 7, 499–518. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024363

Deng, J., Guo, Y., Ma, T., Yang, T., and Tian, X. (2019). How job stress influences job performance among Chinese healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 24, 2–11. doi: 10.1186/s12199-018-0758-4

Deng, J., Liu, J., Guo, Y., Gao, Y., Wu, Z., and Yang, T. (2021). How does social support affect public service motivation of healthcare workers in China: the mediating effect of job stress? BMC Public Health 21, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11028-9

Di Marco, D., López-Cabrera, R., Arenas, A., Giorgi, G., Arcangeli, G., and Mucci, N. (2016). Approaching the discriminatory work environment as stressor: the protective role of job satisfaction on health. Front. Psychol. 7:1313. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01313

Duxbury, L., Bardoel, A., and Halinski, M. (2021). ‘Bringing the Badge home’: exploring the relationship between role overload, work-family conflict, and stress in police officers. Polic. Soc. 31, 997–1016. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2020.1822837

Duxbury, L., Lyons, S., and Higgins, C. (2008). “Too much to do, and not enough time: an examination of role overload” in Handbook of Work-Family Integration. eds. K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, and D. L. Whitehead (Guelph, ON: Academic Press), 125–140.

Ebrahimi, Z. F., Chong, C. W., and Rad, R. H. (2014). TQM practices and employees’ role stressors. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 31, 166–183. doi: 10.1108/IJQRM-04-2013-0067

Edwards, J. R., and Rothbard, N. P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 178–199. doi: 10.2307/259269

Elloy, D. F., and Smith, C. (2004). Antecedents of work-family conflict among dual-career couples: an Australian study. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 11, 17–27. doi: 10.1108/13527600410797927

Faragher, E. B., Cass, M., and Cooper, C. L. (2013). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis from stress. Wellbeing 1, 254–271. doi: 10.1057/9781137310651_12

Fisher, D. M. (2014). A multilevel cross-cultural examination of role overload and organizational commitment: investigating the interactive effects of context. J. Appl. Psychol. 99, 723–736. doi: 10.1037/a0035861

Fox, M. L., Dwyer, D. J., and Ganster, D. C. (1993). Effects of stressful job demands and control on physiological and attitudinal outcomes in a hospital setting. Acad. Manag. J. 36, 289–318. doi: 10.2307/256524

Giauque, D., Anderfuhren-Biget, S., and Varone, F. (2013). Stress perception in public organizations: expanding the Job Demands–Job Resources model by including public service motivation. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 33, 58–83. doi: 10.1177/0734371X12443264

Giauque, D., Ritz, A., Varone, F., and Anderfuhren-Biget, S. (2012). Resigned but satisfied: the negative impact of public service motivation and red tape on work satisfaction. Public Admin. 90, 175–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01953.x

Gould-Williams, J. S., Bottomley, P., Redman, T. O. M., Snape, E. D., Bishop, D. J., Limpanitgul, T., et al. (2014). Civic duty and employee outcomes: do high commitment human resource practices and work overload matter. Public Admin. 92, 937–953. doi: 10.1111/padm.12019

Grandy, A. A., Cordeiro, B. L., and Crouter, A. C. (2005). A longitudinal and multi-source test of the work–family conflict and job satisfaction relationship. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 78, 305–323. doi: 10.1348/096317905x26769

Greenhaus, J. H., and Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 31, 72–92. doi: 10.5465/amr.2006.19379625

Greenhaus, J. H., Ziegert, J. C., and Allen, T. D. (2012). When family-supportive supervision matters: relations between multiple sources of support and work–family balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.008

Gurbuz, S., Turunc, O., and Celik, M. (2013). The impact of perceived organizational support on work–family conflict: does role overload have a mediating role? Econ. Ind. Democr. 34, 145–160. doi: 10.1177/0143831x12438234

Hassan, H. A., Zhang, X., Ahmad, A. B., and Liu, B. (2021). Public service motivation and employee change-supportive intention: utilizing the theory of planned behavior. Public Pers Manage 50, 283–304. doi: 10.1177/0091026020934515

Heller, D., and Watson, D. (2005). The dynamic spillover of satisfaction between work and marriage: the role of time and mood. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 1273–1279. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1273

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Homberg, F., McCarthy, D., and Tabvuma, V. (2015). A meta-analysis of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction. Public Admin. Rev. 75, 711–722. doi: 10.1111/puar.12423

Houston, D. J. (2011). Implications of occupational locus and focus for public service motivation: attitudes toward work motives across nations. Public Admin. Rev. 71, 761–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02415.x

Hu, Y., and Scott, J. (2016). Family and gender values in China: generational, geographic, and gender differences. J. Fam. Issues 37, 1267–1293. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14528710

Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, I., Taylor, P., and Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J. Manag. Psychol. 20, 178–187. doi: 10.1108/02683940510579803

Jones, E., Chonko, L., Rangarajan, D., and Roberts, J. (2007). The role of overload on job attitudes, turnover intention, and salesperson performance. J. Bus. Res. 60, 663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.02.014

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., and Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 127, 376–407. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376

Kim, S. (2012). Does person-organization fit matter in the public-sector? Testing the mediating effect of person-organization fit in the relationship between public service motivation and work attitudes. Public Admin. Rev. 72, 830–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02572.x

Kim, Y., Lee, H., and Park, H. (2018). Relationships between role overload and work engagement among employees: a moderated mediation model. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 31, 249–279. doi: 10.24230/kjiop.v31i1.249-279

Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., and Hammer, L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: a meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers. Psychol. 64, 289–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x

Kristof, A. (1996). Person-organization fit: an integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 49, 1–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x

Lambert, V. A., and Lambert, C. E. (2001). Literature review of role stress/strain on nurses: an international perspective. Nurs. Health Sci. 3, 161–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00086.x

Lapierre, L. M., Li, Y., Kwan, H. K., Greenhaus, J. H., DiRenzo, M. S., and Shao, P. (2018). A meta-analysis of the antecedents of work–family enrichment. J. Organ. Behav. 39, 385–401. doi: 10.1002/job.2234

Li, M., Wen, B., and Hsieh, C. W. (2022). Understanding the role reward types play in linking public service motivation to task satisfaction: evidence from an experiment in China. Int. Public Manag. J. 25, 300–319. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2021.1963891

Li, M., and Wang, Z. (2016). Emotional labor strategies as mediators of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction in Chinese teachers. Int. J. Psychol. 51, 177–184. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12114

Lin, M., and Ling, Q. (2018). Is role stress always harmful? Differentiating role overload and role ambiguity in the challenge-hindrance stressors framework. Tour. Manag. 68, 355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.04.007

Liu, B. (2020). Understanding and Cultivating Workforce 2020. Public Pers. Manag. 49, 503–507. doi: 10.1177/0091026020931551

Liu, B. C., and Perry, J. L. (2016). The psychological mechanisms of public service motivation: a two-wave examination. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 36, 4–30. doi: 10.1177/0734371X14549672

Liu, B. C., Tang, N. Y., and Zhu, X. M. (2008). Public service motivation and job satisfaction in China: an investigation of generalizability and instrumentality. Int. J. Manpow. 29, 684–699. doi: 10.1108/01437720810919297

Liu, B. C., and Tang, T. L. P. (2011). Does the love of money moderate the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction? The case of Chinese professionals in the public sector. Public Admin. Rev. 71, 718–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02411.x

Liu, B. C., Tang, T. L. P., and Yang, K. F. (2015a). When does public service motivation fuel the job satisfaction fire? The joint moderation of person–organization fit and needs–supplies fit. Public Manag. Rev. 17, 876–900. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2013.867068

Liu, B. C., Yang, K. F., and Yu, W. (2015b). Work-related stressors and health-related outcomes in public service: examining the role of public service motivation. Am. Rev. Public Admin. 45, 653–673. doi: 10.1177/0275074014524298

Locke, E. A. (1976). “The nature and cause of job satisfaction” in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. ed. M. D. Dunnette (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally), 1297–1349.

McCarthy, A., Darcy, C., and Grady, G. (2010). Work-life balance policy and practice: understanding line manager attitudes and behaviors. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 20, 158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.12.001

Moynihan, D. P., and Pandey, S. K. (2007). The role of organizations in fostering public service motivation. Public Admin. Rev. 67, 40–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00695.x

Naff, K. C., and Crum, J. (1999). Working for America: does public service motivation make a difference? Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 19, 5–16. doi: 10.1177/0734371x9901900402

Olatunji, S. O., and Mokuolu, B. O. (2014). The influence of sex, marital status, and tenure of service on job stress, and job satisfaction of health workers in a Nigerian federal health institution. Afr. Res. Rev. 8, 126–133. doi: 10.4314/afrrev.v8i1.10

Paarlberg, L. E., Perry, J. L., and Hondeghem, A. (2008). “From theory to practice: strategies for applying public service motivation,” in Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service. eds. J. L. Perry and A. Hondeghem (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 268–293.

Park, S. (2020). Determinants of the job satisfaction of public officials: testing the mediation effect of organizational commitment. Public Organ. Rev. 20, 665–684. doi: 10.1007/s11115-020-00465-6

Pecino, V., Mañas, M. A., Díaz-Fúnez, P. A., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Padilla-Góngora, D., and López-Liria, R. (2019). Organizational climate, role stress, and public employees’ job satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:1792. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101792

Perry, J. L. (1996). Measuring public service motivation: an assessment of construct reliability and validity. J. Public Admin. Res. Theory 6, 5–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024303

Perry, J. L., and Hondeghem, A. (2008). Motivation in Public Management: The Call of Public Service. New York: Oxford University Press.

Perry, J. L., and Wise, L. R. (1990). The motivational bases of public service. Public Admin. Rev. 50, 367–373. doi: 10.2307/976618

Peterson, M. F., Smith, P. B., Akande, A., Ayestaran, S., Bochner, S., Callan, V., et al. (1995). Role conflict, ambiguity, and overload: a 21-nation study. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 429–452. doi: 10.2307/256687

Piatak, J. S. (2019). Weathering the storm: the impact of cutbacks on public employees. Public Pers. Manag. 48, 97–119. doi: 10.1177/0091026018801044

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prysmakova, P., and Vandenabeele, W. (2020). Enjoying police duties: public service motivation and job satisfaction. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 35, 304–317. doi: 10.1007/s11896-019-09324-7

Örtqvist, D., and Wincent, J. (2006). Prominent consequences of role stress: a meta-analytic review. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 13, 399–422. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.399

Quratulain, S., and Khan, A. K. (2015). How does employees’ public service motivation get affected? A conditional process analysis of the effects of person–job fit and work pressure. Public Pers. Manag. 44, 266–289. doi: 10.1177/0091026014568461

Rayner, J., Reimers, V., and Chao, C. W. (2018). Testing an international measure of public service motivation: is there really a bright or dark side? Aust. J. Public Admin. 77, 87–101. doi: 10.1111/1467-8500.12247

Ripoll, G., and Schott, C. (2020). Does public service motivation foster justification of unethical behavior? Evidence from survey research among citizens. Int. Public Manag. J. 26, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2020.1825576

Ritz, A., Brewer, G. A., and Neumann, O. (2016). Public service motivation: a systematic literature review and outlook. Public Admin. Rev. 76, 414–426. doi: 10.1111/puar.12505

Rogers, S. J., and May, D. C. (2003). Spillover between marital quality and job satisfaction: long-term patterns and gender differences. J. Marriage Fam. 65, 482–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00482.x

Roh, C. Y., Moon, M. J., Yang, S. B., and Jung, K. (2016). Linking emotional labor, public service motivation, and job satisfaction: social workers in health care settings. Soc. Work Public Health 31, 43–57. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2015.1087904

Scott, P. G., and Pandey, S. K. (2005). Red tape and public service motivation: findings from a national survey of managers in state health and human services agencies. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 25, 155–180. doi: 10.1177/0734371X04271526

Shek, D. T. (2006). Chinese family research: puzzles, progress, paradigms, and policy implications. J. Fam. Issues 27, 275–284. doi: 10.1177/0192513X05283508

Stevens, D. P., Minnotte, K. L., Mannon, S. E., and Kiger, G. (2007). Examining the “neglected side of the work-family interface” antecedents of positive and negative family-to-work spillover. J. Fam. Issues 28, 242–262. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06294548

Sun, S. (2021). The relationship between public service motivation and affective commitment in the public sector change: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 12:631948. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631948

Taris, T. W., Schreurs, P. J., and Van Iersel Silfhout, I. J. (2001). Job stress, job strain, and psychological withdrawal among Dutch university staff: towards a dual-process model for the effects of occupational stress. Work Stress. 15, 283–296. doi: 10.1080/02678370110084049

Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., and Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work–home interface: the work–home resources model. Am. Psychol. 67, 545–556. doi: 10.1037/a0027974

Teo, S. T., Pick, D., Xerri, M., and Newton, C. (2016). Person–organization fit and public service motivation in the context of change. Public Manag. Rev. 18, 740–762. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1045016

Tordera, N., González-Romá, V., and Peiró, J. M. (2008). The moderator effect of psychological climate on the relationship between leader–member exchange (LMX) quality and role overload. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 17, 55–72. doi: 10.1080/13594320701392059

Van Loon, N. M., Vandenabeele, W., and Leisink, P. (2015). On the bright and dark side of public service motivation: the relationship between PSM and employee wellbeing. Public Money Manag. 35, 349–356. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2015.1061171

Vatharkar, P. S., and Aggarwal-Gupta, M. (2020). Relationship between role overload and the work–family interface. Comp. Psychol. Monogr. 9, 305–321. doi: 10.1108/SAJBS-09-2019-0167

Wharton, A. S., and Blair-Loy, M. (2006). Long work hours and family life: a cross-national study of employees’ concerns. J. Fam. Issues 27, 415–436. doi: 10.1177/0192513X05282985

Wright, B. E., and Pandey, S. K. (2008). Public service motivation and the assumption of person–organization fit: testing the mediating effect of value congruence. Admin. Soc. 40, 502–521. doi: 10.1177/0095399708320187

Wright, B. E., and Pandey, S. K. (2011). Public organizations and mission valence: when does mission matter? Admin. Soc. 43, 22–44. doi: 10.1177/0095399710386303

Xie, Y. (2013). Gender and family in contemporary China. Population studies center research report 13, 808.

Yousef, D. A. (2002). Job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between job stressors and affective, continuance, and normative commitment: a path analytical approach. Int. J. Stress Manage. 9, 99–112. doi: 10.1023/a:1014954703735

Zeinabadi, H. (2010). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) of teachers. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 5, 998–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.225

Zhang, H., Sun, L., and Zhang, Q. (2022). How Workplace social capital affects turnover intention: the mediating role of job satisfaction and burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:9587. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159587

Keywords: public service motivation, job satisfaction, role overload, marital status, public employees

Citation: Zhang Y (2023) Disclosing the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction in the Chinese public sector: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 14:1073370. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1073370

Edited by:

Nicola Mucci, University of Florence, ItalyReviewed by:

Amalia Raquel Pérez Nebra, University of Zaragoza, SpainVincenzo Cupelli, Retired, Florence, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Zhang, ✉ emhhbmd5aW5nMDgwQHNqdHUuZWR1LmNu

Ying Zhang

Ying Zhang