95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 20 January 2023

Sec. Gender, Sex and Sexualities

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1060543

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights in Gender, Sex and Sexualities: 2022 View all 14 articles

Prithvi Sanjeevkumar Gaur1

Prithvi Sanjeevkumar Gaur1 Sreoshy Saha2

Sreoshy Saha2 Ashish Goel3

Ashish Goel3 Pavel Ovseiko4

Pavel Ovseiko4 Shelley Aggarwal5

Shelley Aggarwal5 Vikas Agarwal6

Vikas Agarwal6 Atiq Ul Haq7

Atiq Ul Haq7 Debashish Danda8

Debashish Danda8 Andrew Hartle9

Andrew Hartle9 Nimrat Kaur Sandhu10

Nimrat Kaur Sandhu10 Latika Gupta6,11,12,13*

Latika Gupta6,11,12,13*The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a significant change in the way healthcare is dispensed. During the pandemic, healthcare inequities were experienced by various sections of society, based on gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. The LGBTQ individuals were also affected by this inequity. There is a lack of information on this topic especially in the developing countries. Hence this issue requires further exploration and understanding. Previous literature briefly explored the mental, physical, and emotional turmoil faced by the LGBTQ community on a regular basis. They feared rejection by family and friends, bullying, physical assault, and religious biases. These issues prevented them from publicly speaking about their sexual orientation thereby making it difficult to collect reliable data. Although they require medical and psychological treatment, they are afraid to ask for help and access healthcare and mental health services. Being mindful of these difficulties, this article explores the various underlying causes of the mental health problems faced by LGBTQ individuals, especially, in the Indian subcontinent. The article also examines the status of healthcare services available to Indian sexual minorities and provides recommendations about possible remedial measures to ensure the well-being of LGBTQ individuals.

- Present condition of LGBTQ + mental healthcare accessibility in the world.

- Present condition of LGBTQ + mental healthcare accessibility in India and neighboring regions.

- Prevalent healthcare disparities faced by the Indian LGBTQ + individuals.

- Reform measures and steps toward providing healthcare to LGBTQ + individuals in the Indian subcontinent.

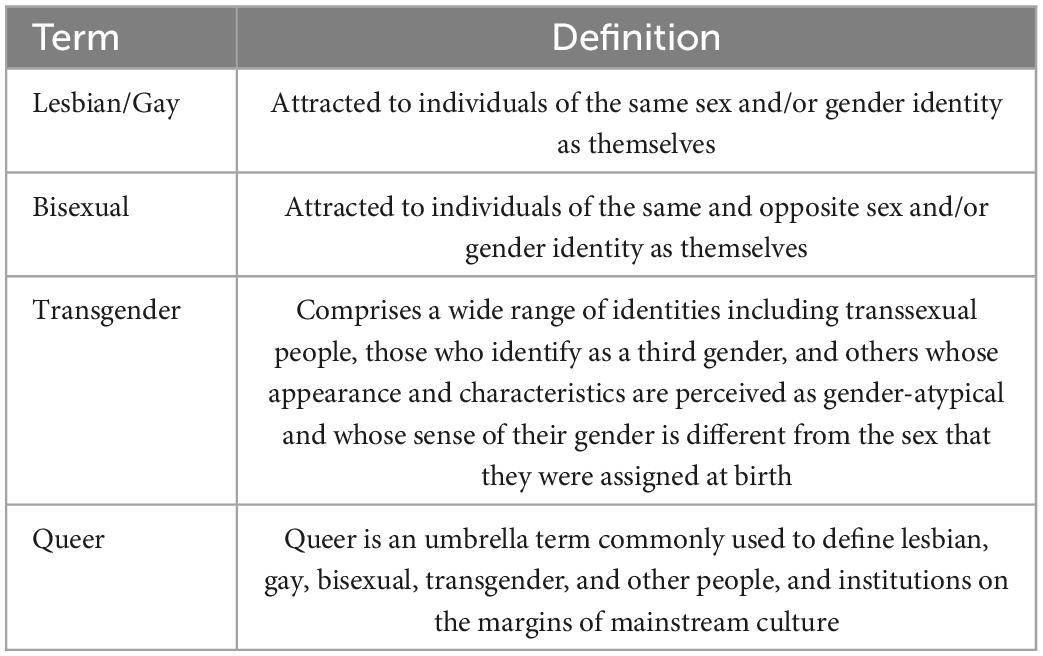

The word LGBTQ is an acronym for Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender and Queer. It is used to describe non-heterosexual and non-cis-gendered individuals. As these terms are often difficult to define, we have utilized the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) definitions for these terms (Definitions, 2017). These definitions have been provided for reference in Table 1 to provide context and clarity in our discussion. The COVID-19 pandemic has dynamically changed the way healthcare services are being delivered to the public. It led to the worsening of inequitable access to healthcare services based on gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity (Lopez et al., 2021). The LGBTQ community has experienced a disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic with 56% of LGBTQ individuals reporting job losses compared to 44% of the non-LGBTQ individuals. Moreover, 74% of the LGBTQ individuals reported worry and stress related to the pandemic had a negative impact on mental health compared to 49% of the non- LGBTQ individuals (Dawson et al., 2021). There is currently a dearth of data on this topic in developing countries particularly in the Indian subcontinent. Our paper aims to fill this gap in knowledge by examining the mental health issues faced by adolescents who identify as LGBTQ in the Indian subcontinent, their inequitable access to healthcare services, and suggest the possible remedial measures which can lessen the impact of these inequities with a special focus on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1. Gender identity definitions as per the UNHRC (Definitions, 2017).

India legalized gay relationships on September 6, 2018, marking the first step toward recognizing LGBTQ rights in the country (The Times of India, 2018). The first Pride March of India was held in Kolkata in March 1999 (Deccan Herald, 2019). However, there is no reliable systematically collected data on the prevalence of LGBTQ individuals in India as the 2011 Census did not record this data accurately (Mandal et al., 2020). Individuals may be hesitant to come out as LGBTQ due to familial stress, religious bias, fear of rejection, fear of physical assault, cultural stigma, etc., making it difficult to collect reliable data (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). The aforementioned factors and others may exacerbate their need to conceal their personal and sexual experiences making them more susceptible to medical and mental health concerns with an insufficient access to healthcare services.

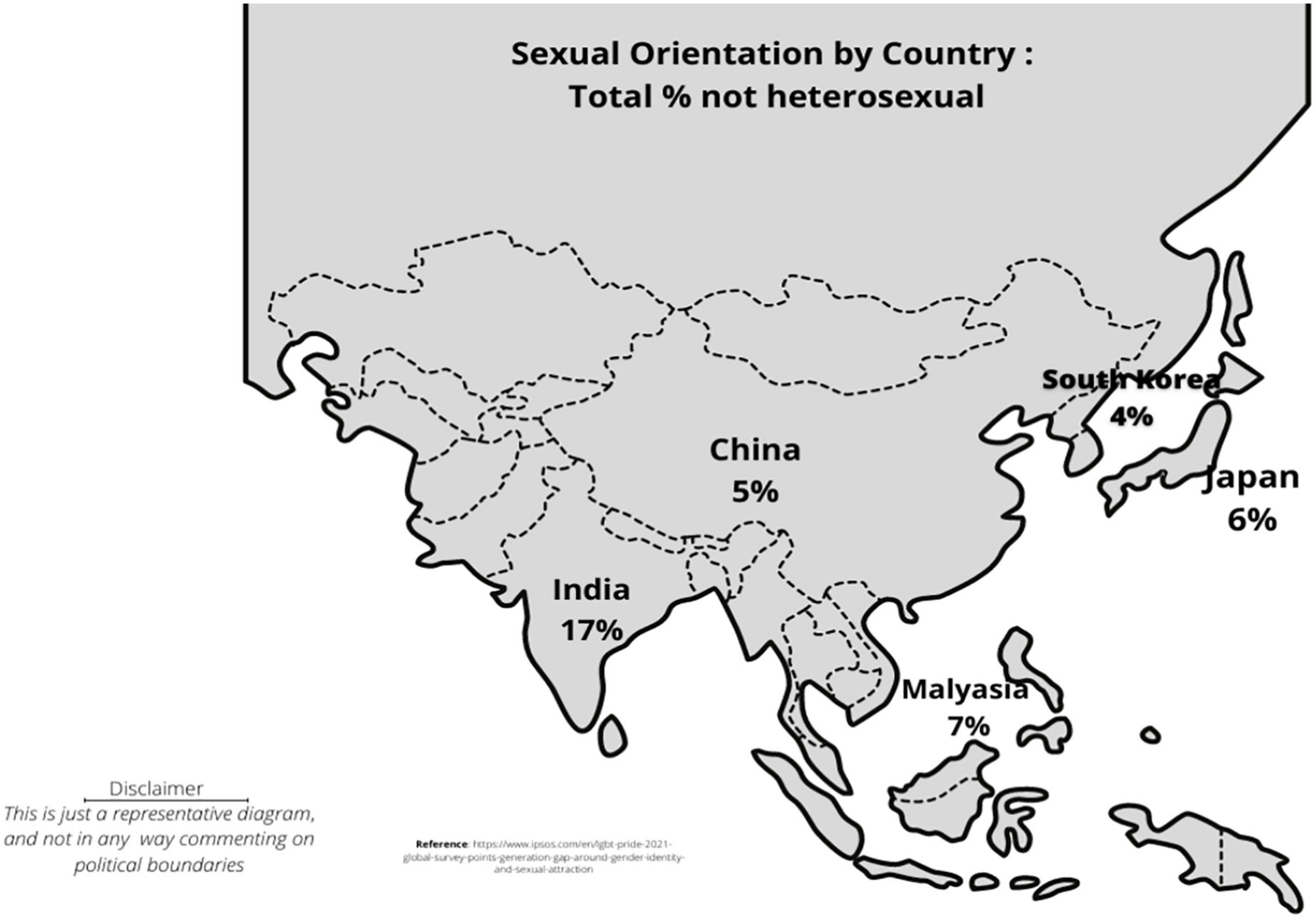

Figure 1 shows the percentage of individuals who identify as non-heterosexual in the different countries of the Indian subcontinent. However, there are limited data to adequately identify individuals who self-report their identity as not being heterosexual.

Figure 1. The percentage of individuals who identify as non-heterosexual in the Indian subcontinent according to LGBT + Pride 2021 Global Survey Report.

A practical paradigm for comprehending mental health disparities among LGBTQ people is Meyer’s Minority Stress model (MS model). MS model implies the stressors and their impact on sexual minorities. The stressors comprise objective external occurrences, expectations of these occurrences, and the internalization of negative societal attitudes. With the division of stresses into proximal and distal categories, the theory puts forth various aspects of the strains on LGBTQ individuals. It affirms the direct connection between the problems of LGBTQ individuals and environmental stress. It also highlights several aspects, i.e., prejudice events, stigma, disclosure, suicide, and mental disorders on the health of LGBTQ. Consequently, we attempt to illustrate several difficulties the LGBTQ youth in the Indian subcontinent experience that have a substantial influence on them (Meyer, 2003; Frost and Meyer, 2009).

Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs) refer to maltreatment, abuse and residing in an environment harmful to the development of a child. They tend to have traumatic and lasting negative impact on the health and well-being of the child (Sutter and Perrin, 2016; Boullier and Blair, 2018). Individuals exposed to greater than four ACEs have stronger association with sexual risk-taking, poor mental health, alcohol and drug abuse and self-inflicted violence (Hughes et al., 2017)It may also lead to the development of feelings of shame which itself has been associated with adverse health outcomes (Scheer et al., 2020).

In a survey conducted with LGBTQ youth between 14 and 18 years of age in the United States and Canada, 43% of the respondents reported being exposed to more than 4 ACEs, with higher scores in 9 out of 10 categories when compared to national samples (Craig et al., 2020). Additional studies from Canada, Mexico, Miami, and Israel show that female sex workers who identify as a sexual minority report having poor mental health compared to sex workers who do not identify as minorities, have a history of childhood trauma and suffer from mental health burdens (Cwikel et al., 2004; Ulibarri et al., 2009, 2013; Surratt et al., 2012; Puri et al., 2017). There is a growing body of literature indicating that LGTBQ individuals endure higher levels of traumatic experiences with a disproportionate impact on their physical and mental health.

LGBTQ youth are more likely to be victims of bullying (Juvonen and Graham, 2014; Earnshaw et al., 2017). LGBTQ victims of bullying in school report higher levels of absenteeism and lower academic achievement (Nishina et al., 2005). It has been linked to emotional distress, somatic complaints such as anxiety and headache, feelings of loneliness and self-blame as well as depression and anxiety (Gini and Pozzoli, 2013; Bruce et al., 2014).

Households which follow heteronormative ideologies are a source of distress for the LGBTQ youth (Castellanos, 2016). Homeless LGBTQ youth report heteronormative attitudes, stigma, and discrimination at home which lead to significant physical and mental health concerns, including engagement in risky sexual behavior, substance abuse and family conflict due to disclosure of sexual orientation (Corliss et al., 2011; Rhoades et al., 2018; Baams et al., 2019).

Many LGBTQ youth are left homeless after disclosing their identity to parents and facing rejection (McCann and Brown, 2019). Studies show that 37% of people reaching out to crisis service providers experience homelessness and a large percentage of those in foster care or unstable housing are LGBTQ youth (Gangamma et al., 2008; Tyler, 2013). These LGBTQ youth face mental health issues like depression, anxiety, suicidal tendencies, substance abuse and show disparate school functioning (Gangamma et al., 2008; Tyler, 2013). Homeless LGBTQ youth are more likely to contract sexually transmitted diseases compared to homeless heterosexual youth and are more likely to report more internalizing symptoms, depression and suicide attempts compared to heterosexual youth (Tyler, 2013).

The coronavirus pandemic forced many LGBTQ youth to stay at home or return back home. This was a possible stressor for those individuals whose sexual orientation was not known at home. The college campus or other out-of-home environments may have been the first opportunity for such individuals where they could continue to explore their sexual identities. They might have participated in educational opportunities such as sexuality and gender studies classes to better understand their identities. However, taking such classes at home may be a cause of discomfort for their families affecting their continued ability to take such classes (The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2020).

Religion plays an important role in societal evolution. This role extends to the acceptance of LGBTQ individuals in society. However, religion is often reported as a source of emotional distress by some of the LGBTQ youth. Most LGBTQ youth cite religion as a negative factor in their lives as their faith communities often show antagonistic behaviors toward same-sex relationships (Ream and Savin-Williams, 2005; Higa et al., 2014). Many LGBTQ youths (73% men and 43% women) may opt for “so called conversion therapy in an attempt to align with expected norms through personal righteousness, individual efforts, church counseling, psychotherapy, support groups, psychiatric treatment, family therapy, peer support and electroconvulsive shock treatments (Dehlin et al., 2015). Although these efforts may have some positive effects such as reduced depression and suicidal ideation, there is a lack of evidence on their effectiveness and they may also have adverse effects (Serovich et al., 2008; Dehlin et al., 2015).

A study conducted in the US reported that 38.6% of the total LGBTQ participants had considered completing suicide while 27.9% of the participants had attempted suicide (Green et al., 2020). The rate of suicidality was higher among those who had undergone sexual orientation or gender identity conversion efforts (Green et al., 2020). Female LGBTQ youth report higher rates of self-harm and suicidality, as they are prone to face more abuse and violence; however, there is no difference in substance abuse among males and females (Russell and Joyner, 2001). Another study showed that LGBTQ adolescents in the grades 7–12 were twice as likely to complete suicide suffer from depression, alcohol, and substance abuse compared to their heterosexual peers (Russell and Joyner, 2001).

There is a dearth of literature regarding the psychological issues faced by LGBTQ youth in India. However, extrapolating the difficulties faced by the adult population some basic assumptions can be made about the healthcare accessibility for adolescents (Rao and Jacob, 2012). A discord between gender identity and natal role, poor self and social acceptance of one’s sexual orientation, discrimination, physical, verbal and sexual abuse from family, friends, and peers during after coming out, fear of law-enforcement, loneliness, and lack of coping mechanisms lead to poor physical and mental health outcomes among the LGBTQ youth (Bhattacharya and Ghosh, 2020).

In Kolkata, a large proportion of the Hijra, Kothis and Transgender individuals (HKT) engage in traditional means of income (logon, cholla and badhai) due to the lack of proper education and employment opportunities, which can take a toll on their mental, physical, and sexual health. The HKT individuals that rely on cholla (begging on the streets and in trains) and logon (singing and dancing at weddings) are more prone to sexual abuse and survival sex (formally known as prostitution or sex work). A study among transgender individuals found that 16.7% of the participants had experienced sexual violence in the last 3 months. HKT individuals often report inaccurate health status, perhaps as a coping mechanism, although they claimed to be healthy but the PCS (Physical Composite Score) and MCS (Mental Composite Score) reflected otherwise (Bhattacharya and Ghosh, 2020).

Men who have sex with men (MSMs) suffer from depression due to the discrimination based on their sexual orientation, gender, physical or sexual violence, alcohol use, STIs and HIV status (Patel et al., 2015). One study reported a prevalence of 52.9% for psychiatric illness among MSMs according to the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) which measures somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression (Prajapati et al., 2014). Studies on a sexual minority of the Indian subcontinent have explored the explicit detrimental impacts of substance abuse on their mental health. Sexual minorities fall into a higher-risk population susceptible to substance abuse. With the involvement of a lot of physical illnesses, it overtly gives rise to a variety of mental health concerns (Tomori et al., 2016; Wilkerson et al., 2018; Wandrekar and Nigudkar, 2020). A study on women of sexual minority showed a high prevalence of alcohol abuse, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), depression, and suicidal risk among transgender individuals (Yr et al., 2018).

Among the adult gay population of Manipur, 6.2% of the participants suffered from GAD, 3.1% had panic disorders and 9.3% had social phobia (Niranjan, 2018). Similarly, mental health disorders were also found among individuals who identified as lesbians (Niranjan, 2018). In Bengaluru, among individuals 18 years and older who are the “Nirvana,” “Akwa,” “Kothis,” the mean depression and anxiety score was 8.5 and ranged from 6.1 among participants identifying themselves as “others” to 9.4 among the Nivana (Thompson et al., 2019). A significant statistical difference was also seen in reports of depression and anxiety based on gender identity. Nearly half of the Nirvana and Akwa hijra participants and a quarter of the Kothi participants reported physical violence in the previous 6 months and experiences of rape in the previous year mostly associated with younger age and working in Basti, sex work as Chelas or at a CBO (community-based organization) (Thompson et al., 2019). A majority of the studies in India focus on transgender individuals who are employed in survival sex including adolescents who are excluded by family and/or society and represent a marginalized community (UNDP, 2010).

Transgender adults and MSMs report avoiding free government healthcare and prefer to self-medicate or access private healthcare as they face discrimination due to social stigma (Patel et al., 2012; King, 2015). Sexual minority women avoid accessing mental healthcare due to the fear of mental health malpractice, the stigma of mental illnesses, and previous negative experiences (Ganju and Saggurti, 2017). Physician homophobia can be a deterrent for LGBTQ patients to seek healthcare (Bowling et al., 2016). Even though healthcare providers are developing positive attitudes, discriminatory practices like delayed services and judgmental attitudes using direct and indirect verbal indicators inhibits the LGBTQ community from accessing healthcare services (Agoramoorthy and Minna, 2007).

Senior psychiatrists have been found to discriminate against LGBTQ individuals based on the traditional gender stereotypes, leading to reduced access to high quality healthcare services (Chakrapani et al., 2011). Despite the efforts of the WHO and the Indian Psychiatric Society to non-pathologize homosexuality, many healthcare professionals still carry out unethical practices such as “so called conversion therapy based on social stigma (Rao et al., 2016). Blood banks are being scrutinized as some of them discourage or “ban” the donation of blood by LGBTQ individuals according to the Central government’s guideline for Blood Donor Selection and Blood Donor Referral that was brought into effect in the 1980s to control the global AIDS pandemic (Kalra, 2012; Hindustan Times, 2021).

Some Indian states, Tamil Nadu being the first, have framed transgender welfare policies under which transgender individuals can access free sex reassignment surgery with proper documentation (UNDP, 2013). A survey among medical students showed that students with greater knowledge about homosexuality showed positive attitudes toward LGBTQ individuals (Banwari et al., 2015). Women had a more positive attitude, which did not correspond with greater knowledge in the study (Madhan et al., 2012). Dental students were less informed and thus, lacked positive attitudes toward LGBTQ patients. This indicates the need for an all-inclusive non-discriminatory curriculum focused on problems of the LGBTQ individuals. Academic books used by the medical students are also seen to contain negative stereotypes regarding LGBTQ individuals which promote social stigma among young medical students (Chatterjee and Ghosh, 2013). A psychiatry book used by the West Bengal University of Health Sciences contains terms such as cross-gender homosexuality and ego-dystonic homosexuality. A forensic medicine book states that homosexuality is an offense, and such individuals may pose a social, moral, and psychological problem. However, the National Medical Commission recently released an advisory to amend the discriminatory information in medical textbooks, taking a step toward LGBTQ inclusion in the medical fraternity (Meyer, 2003).

The health disparities faced by the LGBTQ community in India due to discrimination and exclusion reflects the deeply embedded cultural practice of homophobia and transphobia, supported by a lack of adequate legal protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

First, strategies must be developed from the ground up to tackle this issue. Childhood experiences profoundly shape our future. Considering the predominance of unfavorable childhood events among LGBTQ youth, a secure and supportive upbringing might lessen their mental health burden to a great extent. An effective strategy for addressing childhood issues should be started with proper conditioning of schools since this is the primary setting where most children learn about social mores and standards (Willging et al., 2016a). The LGBTQ youth and the SHPs agree that there is a need to increase knowledge, improve skills, and change attitudes toward LGBTQ-related topics among SHPs (Reisner et al., 2020). Elimination of the bullying culture could be an impactful approach owing to it having a severe negative impact on victims. In the Indian subcontinent, there is a dearth of effective prevention strategies to deal with bullying toward LGBTQ youth; this problem has instilled panic in LGBTQ youth for ages. To overcome this challenge, training School Health Professionals (SHPs) can be helpful as they would be enabled to serve as a source of care and support for LGBTQ youth. SHPs need to address bullying and victimization to help prevent poor psychological outcomes among LGBTQ youth.

Unstable housing is one of the major challenges LGBTQ youths encounter in the Indian subcontinent. With the provocation of many problems, mental health has also drastically deteriorated due to homelessness or domestic disputes. While family support could be a big comfort for LGBTQ youth, their rejection instead makes it challenging for LGBTQ youth to live with family. If the family members were enlightened and empathetic toward LGBTQ youth, the quality of their life could substantially improve. Therefore, our recommendation in this regard is to educate and involve family members to improve the lives of LGBTQ youth. We must identify ways to safely involve family members who are vital to the LGTBQ individuals’ lives. If a welcoming environment could be established in the family for this vulnerable population, it could relieve many of the mental health issues (Meyer, 2003; Pufahl et al., 2021).

Homophobic hospital settings have been one of the omniscient worries for most of the LGBTQ youth. Though they have been battling several mental health issues for years, they are hesitant to get help from healthcare providers due to cultural baggage. They have many unaddressed health concerns they fear disclosing, which keeps inflating their health. If the clinical setting environment could be improved, it would aid in resolving both biological and mental health difficulties. In enhancing healthcare services for LGBTQ youth in India, it is essential to better understand the unmet medical needs of LGBTQ individuals and develop competencies among healthcare workers to handle such patients with compassion and sensitivity.

In light of this pressing issue, our recommendations skew toward training healthcare professionals to provide appropriate care to LGBTQ youth. Taking into consideration the six building blocks of the CanMEDs 2015 Physician Competency Framework of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, the health inequities of the LGBTQ population in India can be addressed by psychiatrists with a range of skills to work with varied patients to achieve a complete understanding of youth predicaments, advocacy, and leadership within communities (Frank et al., 2015; Kealy-Bateman, 2018). LGBTQ–informed treatment involves easily implementable additions to practices like asking the clients about the pronouns they prefer, avoiding disrespectful language, and not making assumptions about the health risks and stereotypes associated with LGBTQ individuals (Frank et al., 2015; Kealy-Bateman, 2018). It has been seen that simply inquiring about the sexual identity of a person decreases the probability of treatment dropout by 30% (Mandal and Dhawan, 2018).

Consequently, healthcare providers must be trained to create a welcoming environment for this vulnerable population. A study by Saahas (meaning courage), a non-profit organization in India, showed that LGBTQ participants showed positive attitudes toward LGBTQ-affirmative treatments. The primary reason for reaching out to Saahas was to discuss queer-specific experiences related to stigma and relationship challenges, such as dealing with family members. Using preferred pronouns and identity validation made the LGBTQ participants more willing to seek help at the organization. In particular, they discussed the multiple types of issues that affect LGBTQ youth, including impacts of religion, caste, class identities, differentiation between environmental problems and those arising from dysfunctional thoughts, and the absence of being in an open space to reveal and discuss the manifestations of sexual abuse and victimization (Wandrekar and Nigudkar, 2019).

Furthermore, healthcare services for LGBTQ youth must be based on the best evidence for clinical effectiveness. Ratner’s 12-step recovery model for homosexual alcohol abusers proved effective and is used by LGBTQ individuals (Ratner, 1988). The reason Ratner’s program worked is that it makes a conscious effort to differentiate between a lesbian and gay lifestyle and the effects of addiction in both (Wandrekar and Nigudkar, 2019). The model also considered possible addiction-related issues like sexual abuse, grief, and victimization (Ratner, 1988). It has been seen that four sessions of motivational interviewing (MI), as compared to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and MI for alcohol-dependent MSM, can reduce drinking for a sustained time period (Morgenstern et al., 2007). Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) has been seen to be effective for homeless LGBTQ youth (Grafsky et al., 2011).

Transparency, effective communication, and extension of community health resources to these vulnerable communities are fundamental to ensuring their overall health and wellbeing.

Although LGBTQ youths have been associated with many undesirable health concerns like more serious self-harm attempts, depression, and substance abuse disorders, there is no standard and reliable source to understand their health issues. Standardized statistics on LGBTQ health status would be eye-opening here since it could help draw attention to the areas that require it the most. In India, there is a scarcity of research related to the understanding of the mental health needs of LGBTQ individuals, and therefore, there is a lack of protocols in place to address gaps in their care. Although some practitioners have established LGBTQ-friendly practices, systematic documentation of these practices is needed with the participation of members of different health professions to develop guidelines providing holistic and gender-affirmative healthcare services (Ranade and Chakravarty, 2013).

In this context, we recommend focusing on developing standardized methods for collecting information about the health status of LGBTQ youth. In doing so, the APA (American Psychological Association) LGB (lesbian, gay, and bisexual) guidelines provide an example of evidence-based guidelines on the management of psychological issues and their determinants for LGB individuals (American Psychological Association, 2021).

Although LGBTQ people’s past experiences led them to view religion as a menace to their lives, it has the potential to save LGBTQ youth if implemented positively. Religious communities can play an important role in the management of mental health issues being faced by LGBTQ youth. Some religious communities provide support to LGBTQ individuals such as the provision of anti-suicide counseling and resources for homelessness with most LGBTQ individuals displaying a preference for in-person resources (Raedel et al., 2020). If implemented In the Indian subcontinent, its adaptation might aid in solving many mental health concerns of LGBTQ youth.

Social media, which possesses a great capacity for transformation, can spell its magic cast on the LGBTQ community if utilized in an effective direction. Previous literature has indicated the use of social networking sites (SNSs) among LGBTQ youth has led to the creation of a community with some level of social support and increased access to sexual health-related information which contributes to positive identity development (Gray, 2009; DeHaan et al., 2013; Craig and McInroy, 2014; Fox and Ralston, 2016). While they are coping with various psychological issues, social community support can help ease the load of addressing it rather alone. Therefore, the use of social media to create a sense of community among LGBTQ youth should be encouraged. However, some of these SNSs have also facilitated cyberbullying or discrimination and victimization based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, which has led to psychological distress and worse mental health outcomes among LGBTQ youth (Varjas et al., 2013; Fox and Moreland, 2015; McConnell et al., 2017; Abreu and Kenny, 2018).

Those who are experiencing a mental breakdown may find great comfort in connecting with a peer who has gone through comparable experiences. A positive shift in the delivery of LGBTQ mental healthcare might result from the formal incorporation of peer intervention in the healthcare setting. With the exploration of many underreported physical and mental health concerns, it can provide remedies to LGBTQ individuals at a root level. It can also create a sense of empowerment with recognition of their necessities (Willging et al., 2016b; Worrell et al., 2022). Therefore, to achieve a positive transformation in LGBTQ mental healthcare, our recommendation leans toward the incorporation of a peer intervention in healthcare delivery.

Our last contribution to the list of recommendations is the digitalization of healthcare settings. This endeavor of comprehensive service delivery may be made achieved through the inclusion of technology. The recent “LGBT Health and Wellness Cloud” initiative in Bengaluru has demonstrated the potential of technology for global healthcare services (The New Indian Express, 2022). If such models are implemented throughout the nation, it can open the door of healthcare services to many underserved LGBTQ people (Nisly et al., 2018). We thus advocate for the alignment of technology in healthcare with a view to raising the bar for equity.

This article highlights the various aspects in which the LGBTQ community has been marginalized within the complex Indian medical system. There is a vital need for reliable centralized statistical data regarding the number of individuals identifying as LGBTQ in India, their healthcare needs as well as the barriers and facilitators of care. As gaps in healthcare demands and accessibility are identified, remedial measures can be taken to ensure the availability of high-quality healthcare services for this traditionally marginalized group. Due to the diversity of this community, reliable collection of accurate information may seem challenging. However, without adequate resource allocation, the medical and mental health needs of a large proportion of this population are being missed or under-identified.

Healthcare professionals must be trained to adequately interview and provide their services to LGBTQ individuals, with compassion and acceptance for all human experiences. Through high quality, evidence-based medical training, health professionals will be better equipped to provide a holistic care. Professional and political organizations should develop policies to allow for the provision of easily accessible healthcare services in an inclusive medical environment for the LGBTQ community. Ultimately, these health disparities must be eliminated as they have the potential to impact the overall health of the community as no group exists in isolation and the health of a community is defined by the health of all those that inhabit it.

LG, PG, SS, and VA: conceptualization. LG, PG, SS, SA, and NS: investigation. LG, PG, SA, and PO: methodology. LG, PG, and SS: resources. LG: software. LG, PO, SA, VA, AUH, and DD: supervision. LG, PG, SS, AG, AH, and NS: validation. LG, PG, SS, AG, PO, and SA: visualization. PG, SS, LG, and NS: writing – original draft. All authors: data curation, writing – review and editing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abreu, R., and Kenny, M. (2018). Cyberbullying and LGBTQ Youth: A systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 11, 81–97. doi: 10.1007/s40653-017-0175-7

Agoramoorthy, G., and Minna, J. H. (2007). India’s homosexual discrimination and health consequences. Revista Saúde Pública 41, 657–660.

American Psychological Association (2021). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay and bisexual clients. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association.

Baams, L., Wilson, B. D. M., and Russell, S. T. (2019). LGBTQ youth in unstable housing and foster care. Pediatrics 143:e20174211. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4211

Banwari, G., Mistry, K., Soni, A., Parikh, N., and Gandhi, H. (2015). Medical students and interns’ knowledge about and attitude towards homosexuality. J. Postgrad. Med. 61, 95–100. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.153103

Bhattacharya, S., and Ghosh, D. (2020). Studying physical and mental health status among hijra, kothi and transgender community in Kolkata. India. Soc. Sci. Med. 265:113412. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113412

Boullier, M., and Blair, M. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences. Paediatr. Child Health 28, 132–137.

Bowling, J., Dodge, B., Banik, S., Rodriguez, I., Mengele, S., Herbenick, D., et al. (2016). Perceived health concerns among sexual minority women in Mumbai, India: An exploratory qualitative study. Cult. Health Sex. 18, 826–840. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1134812

Bruce, D., Stall, R., Fata, A., and Campbell, R. T. (2014). Modeling minority stress effects on homelessness and health disparities among young men who have sex with men. J. Urban Health 91, 568–580. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9876-5

Castellanos, H. D. (2016). The role of institutional placement, family conflict, and homosexuality in homelessness pathways among latino LGBT Youth in New York City. J. Homosex. 63, 601–632. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1111108

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Top health issues for LGBT populations information & Resource Kit. Available online at: https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/top-health-issues-lgbt-populations-information-resource-kit. (accessed July 16, 2022).

Chakrapani, V., Newman, P., Shunmugam, M., and Dubrow, R. (2011). Barriers to free antiretroviral treatment access among kothi-identified men who have sex with men and aravanis (transgender women) in Chennai, India. AIDS Care 23, 1687–1694. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.582076

Chatterjee, S., and Ghosh, S. (2013). Void in the sphere of wisdom: A distorted picture of homosexuality in medical textbooks. Available online at: http://ijme.in/articles/void-in-the-sphere-of-wisdom-a-distorted-picture-of-homosexuality-in-medical-textbooks/?galley=html (accessed January 10, 2023).

Corliss, H. L., Goodenow, C. S., Nichols, L., and Austin, S. B. (2011). High burden of homelessness among sexual-minority adolescents: Findings from a representative massachusetts high school sample. Am. J. Public Health 101, 1683–1689. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300155

Craig, S. L., and McInroy, L. (2014). you can form a part of yourself online: The influence of new media on identity development and coming out for LGBTQ youth. J. Gay Lesb. Ment. Health 18, 95–109.

Craig, S. L., Austin, A., Levenson, J., Leung, V. W., Eaton, A. D., and Souza, S. A. (2020). Frequencies and patterns of adverse childhood events in LGBTQ+ youth. Child Abuse Neglect 107:104623. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104623

Cwikel, J., Chudakov, B., Paikin, M., Agmon, K., and Belmaker, R. H. (2004). Trafficked female sex workers awaiting deportation: Comparison with brothel workers. Arch Womens Ment. Health 7, 243–249. doi: 10.1007/s00737-004-0062-8

Dawson, L., Kirzinger, A., and Kates, J. (2021). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on LGBT People. Available online at: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-lgbt-people (accessed January 10, 2023).

Definitions (2017). UN free & equal. Available online at: https://www.unfe.org/definitions/ (accessed April 23, 2022).

DeHaan, S., Kuper, L. E., Magee, J. C., Bigelow, L., and Mustanski, B. S. (2013). The interplay between online and offline explorations of identity, relationships, and sex: A mixed-methods study with LGBT youth. J. Sex. Res. 50, 421–434. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.661489

Dehlin, J. P., Galliher, R. V., Bradshaw, W. S., Hyde, D. C., and Crowell, K. A. (2015). Sexual orientation change efforts among current or former LDS church members. J. Counsel. Psychol. 62, 95–105.

Earnshaw, V. A., Reisner, S. L., Juvonen, J., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Perrotti, J., and Schuster, M. A. (2017). LGBTQ Bullying: Translating research to action in pediatrics. Pediatrics 140, e20170432. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0432

Fox, J., and Moreland, J. J. (2015). The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 45, 168–176.

Fox, J., and Ralston, R. (2016). Queer identity online: Informal learning and teaching experiences of LGBTQ individuals on social media. Comput. Human Behav. 65, 635–642.

Frank, J. R., Snell, L., and Sherbino, J. (2015). CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Frost, D. M., and Meyer, I. H. (2009). Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. J. Counsel. Psychol. 56, 97–109.

Gangamma, R., Slesnick, N., Toviessi, P., and Serovich, J. (2008). Comparison of HIV Risks among gay, lesbian, bisexual and heterosexual homeless youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 37, 456–464. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9171-9

Ganju, D., and Saggurti, N. (2017). Stigma, violence and HIV vulnerability among transgender persons in sex work in Maharashtra, India. Cult. Health Sex. 19, 903–917. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1271141

Gini, G., and Pozzoli, T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 132, 720–729.

Grafsky, E. L., Letcher, A., Slesnick, N., and Serovich, J. M. (2011). Comparison of treatment response among GLB and non-GLB street living youth. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.10.007

Gray, M. L. (2009). negotiating identities/queering desires: Coming out online and the remediation of the coming-out story. J. Comput.Media. Commun. 14, 1162–1189.

Green, A. E., Price-Feeney, M., Dorison, S. H., and Pick, C. J. (2020). Self-reported conversion efforts and suicidality among US LGBTQ youths and young adults, 2018. Am. J. Public Health 110, 1221–1227. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305701

Higa, D., Hoppe, M. J., Lindhorst, T., Mincer, S., Beadnell, B., Morrison, D. M., et al. (2014). Negative and positive factors associated with the well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (lgbtq) youth. Youth Soc. 46, 663–687. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12449630

Hindustan Times (2021). Bar on transgender persons, others from donating blood: SC seeks govt’s response. Available online at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/sc-seeks-centre-response-on-barring-transgenders-gay-people-from-donating-blood-101614936356466.html

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., et al. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2, e356–e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

Juvonen, J., and Graham, S. (2014). Bullying in Schools: The power of bullies and the plight of victims. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65, 159–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115030

Kalra, G. (2012). Breaking the ice: IJP on homosexuality. Indian J. Psychiatry 54:299. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102463

Kealy-Bateman, W. (2018). The possible role of the psychiatrist: The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population in India. Indian J. Psychiatry 60, 489–493. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_83_17

King, M. (2015). Attitudes of therapists and other health professionals towards their LGB patients. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 27, 396–404. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1094033

Lopez, L. III, Hart, L. H. III, and Katz, M. H. (2021). Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA 325, 719–720.

Madhan, B., Gayathri, H., Garhnayak, L., and Naik, E. (2012). Dental students’ regard for patients from often-stigmatized populations: Findings from an Indian dental school. J. Dent. Educ. 76, 210–217.

Mandal, C., Debnath, P., and Sil, A. (2020). ‘Other’ gender in India: An Analysis of 2011 Census Data. SocArXiv. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/j48qy

Mandal, P., and Dhawan, A. (2018). Interventions in individuals with specific needs. Indian J. Psychiatry 60, S553–S558.

McCann, E., and Brown, M. (2019). Homelessness among youth who identify as LGBTQ+: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 28, 2061–2072. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14818

McConnell, E. A., Clifford, A., Korpak, A. K., Phillips, G., and Birkett, M. (2017). Identity, victimization, and support: Facebook experiences and mental health among LGBTQ Youth. Comput. Human. Behav. 76, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.026

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–697.

Morgenstern, J., Irwin, T. W., Wainberg, M. L., Parsons, J. T., Muench, F., Jr, D. A., et al. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men who have sex with men. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75, 72–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.72

Niranjan, H. (2018). A study on homosexuals and their psychiatric morbidities in a northeastern state of India, Manipur. Indian J. Soc. Psychiatry 34, 245–248.

Nishina, A., Juvonen, J., and Witkow, M. R. (2005). Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The psychosocial. Somatic, and Scholastic Consequences of Peer Harassment. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 34, 37–48. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_4

Nisly, N., Imborek, K., Miller, M., Dole, N., Priest, J., Sandler, L., et al. (2018). Developing an Inclusive and Welcoming LGBTQ Clinic. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 646–662.

Patel, S. K., Prabhakar, P., and Saggurti, N. (2015). Factors associated with mental depression among men who have sex with men in Southern India. Health 07:1114.

Patel, V., Mayer, K., and Makadon, H. (2012). Men who have sex with men in India: A diverse population in need of medical attention. Indian J. Med. Res. 136, 563–570.

Prajapati, A. C., Parikh, S., and Bala, D. V. (2014). A study of mental health status of men who have sex with men in Ahmedabad city. Indian J. Psychiatry 56:161. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.130498

Pufahl, J., Rawatb, S., Chaudary, J., and Shiff, N. J. (2021). Even mists have silver linings: Promoting LGBTQ+ acceptance and solidarity through community-based theatre in India. Public Health 194, 252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.027

Puri, N., Shannon, K., Nguyen, P., and Goldenberg, S. M. (2017). Burden and correlates of mental health diagnoses among sex workers in an urban setting. BMC Womens Health 17:133. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0491-y

Raedel, D. B., Wolff, J. R., Davis, E. B., and Ji, P. (2020). Clergy attitudes about ways to support the mental health of sexual and gender minorities. J. Relig. Health 59, 3227–3246.

Ranade, K., and Chakravarty, S. (2013). Conceptualising gay affirmative counselling practice in India building on local experiences of counselling with sexual minority clients. Indian J. Soc. Work 74, 237–254.

Rao, T. S., Sathyanarayana Rao, T. S., Prasad Rao, G., Raju, M. S. V. K., Saha, G., Jagiwala, M., et al. (2016). Gay rights, psychiatric fraternity, and India. Indian J. Psychiatry 58:241. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.192006

Ratner, E. (1988). Model for the treatment of lesbian and gay alcohol abusers. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 5, 25–46.

Ream, G. L., and Savin-Williams, R. (2005). Reconciling christianity and positive non-heterosexual identity in adolescence, with implications for psychological well-being. J. Gay Lesb. Issues Educ. 2, 19–36.

Reisner, S. L., Sava, L. M., Menino, D. D., Perrotti, J., Barnes, T. N., Humphrey, D. L., et al. (2020). Addressing LGBTQ student bullying in massachusetts schools: Perspectives of LGBTQ students and school health professionals. Prev. Sci. 21, 408–421.

Rhoades, H., Rusow, J. A., Bond, D., Lanteigne, A., Fulginiti, A., and Goldbach, J. T. (2018). Homelessness, mental health and suicidality among LGBTQ youth accessing crisis services. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 49, 643–651. doi: 10.1007/s10578-018-0780-1

Russell, S. T., and Joyner, K. (2001). Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. Am. J. Public Health 91, 1276–1281.

Scheer, J. R., Harney, P., Esposito, J., and Woulfe, J. M. (2020). Self-reported mental and physical health symptoms and potentially traumatic events among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals: The role of shame. Psychol. Violence 10, 131–142. doi: 10.1037/vio0000241

Serovich, J. M., Craft, S. M., Toviessi, P., Gangamma, R., McDowell, T., and Grafsky, E. L. (2008). A systematic review of the research base on sexual reorientation therapies. J Marital Fam. Ther. 34, 227–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00065.x

Surratt, H. L., Kurtz, S. P., Chen, M., and Mooss, A. (2012). HIV risk among female sex workers in Miami: The impact of violent victimization and untreated mental illness. AIDS Care 24, 553–561. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630342

Sutter, M., and Perrin, P. B. (2016). Discrimination, mental health, and suicidal ideation among LGBTQ people of color. J. Couns. Psychol. 63, 98–105. doi: 10.1037/cou0000126

The Chronicle of Higher Education (2020). Covid-19 Sent LGBTQ students back to unsupportive homes. that raises the risk they won’t return. Available online at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/covid-19-sent-lgbtq-students-back-to-unsupportive-homes-that-raises-the-risk-they-wont-return (accessed January 10, 2023).

The New Indian Express (2022). Health, wellness cloud for LGBTQIA+ launchedin Bengaluru. Chennai: The New Indian Express.

The Times of India (2018). Supreme court decriminalises section 377: All you need to know | India News - Times of India. Available online at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/sc-verdict-on-section-377-all-you-need-to-know/articleshow/65695884.cms (accessed January 10, 2023).

Thompson, L. H., Dutta, S., Bhattacharjee, P., Leung, S., Bhowmik, A., Prakash, R., et al. (2019). Violence and mental health among gender-diverse individuals enrolled in a human immunodeficiency virus program in Karnataka. South India. Trans. Health 4, 316–325. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2018.0051

Tomori, C., McFall, A. M., Srikrishnan, A. K., Mehta, S. H., Solomon, S. S., Anand, S., et al. (2016). Diverse rates of depression among men who have sex with men (msm) across india: Insights from a multi-site mixed method study. AIDS Behav. 20, 304–316. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1201-0

Tyler, K. A. (2013). Homeless Youths’ HIV risk behaviors with strangers: Investigating the importance of social networks. Arch. Sex Behav. 42, 1583–1591. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0091-3

Ulibarri, M. D., Hiller, S., Lozada, R., Rangel, M., Stockman, J., Silverman, J., et al. (2013). prevalence and characteristics of abuse experiences and depression symptoms among injection drug-using female sex workers in Mexico. J. Environ. Public Health 2013:631479. doi: 10.1155/2013/631479

Ulibarri, M. D., Semple, S. J., Rao, S., Strathdee, S. A., Fraga-Vallejo, M. A., Bucardo, J., et al. (2009). History of abuse and psychological distress symptoms among female sex workers in two Mexico-U.S. Border Cities. Violence Vict. 24, 399–413. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.3.399

UNDP (2013). The case of tamil nadu transgender welfare board: Insights for developing practical models of social protection programmes for transgender people in India | UNDP in India. New York: UNDP.

UNDP. (2010). Hijras/Transgender women in India: HIV, Human rights and social exclusion. New York: UNDP.

Varjas, K., Meyers, J., Kiperman, S., and Howard, A. (2013). Technology hurts? Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth perspectives of technology and cyberbullying. J. Sch. Violence 12, 27–44.

Wandrekar, J., and Nigudkar, A. (2019). Learnings From SAAHAS—A Queer Affirmative CBT-Based Group Therapy Intervention for LGBTQIA+ Individuals in Mumbai, India. J. Psychosex. Health 1, 164–173.

Wandrekar, J., and Nigudkar, A. (2020). What Do We Know About LGBTQIA+ mental health in india? A review of research from 2009 to 2019. J. Psychosex. Health 2, 26–36.

Wilkerson, J. M., Di Paola, A., Rawat, S., Patankar, P., Rosser, B. R. S., and Ekstrand, M. L. (2018). Substance Use, mental health, hiv testing, and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men in the state of Maharashtra, India. AIDS Educ. Prev. 30, 96–107. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2018.30.2.96

Willging, C. E., Green, A. E., and Ramos, M. M. (2016a). Implementing school nursing strategies to reduce LGBTQ adolescent suicide: A randomized cluster trial study protocol. Implement. Sci. 11:145. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0507-2

Willging, C. E., Israel, T., Ley, D., Trott, E. M., DeMaria, C., Joplin, A., et al. (2016b). Coaching mental health peer advocates for rural LGBTQ people. J. Gay Lesb. Ment. Health 20, 214–236. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2016.1166469

Worrell, S., Waling, A., Anderson, J., Lyons, A., Pepping, C. A., and Bourne, A. (2022). The Nature and impact of informal mental health support in an LGBTQ Context: Exploring peer roles and their challenges. Sexuality research & social policy. J. NSRC 19, 1586–1597. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00681-9

Keywords: COVID-19, LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer), adolescent, mental healthcare, sexual and gender minorities

Citation: Gaur PS, Saha S, Goel A, Ovseiko P, Aggarwal S, Agarwal V, Haq AU, Danda D, Hartle A, Sandhu NK and Gupta L (2023) Mental healthcare for young and adolescent LGBTQ+ individuals in the Indian subcontinent. Front. Psychol. 14:1060543. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1060543

Received: 03 October 2022; Accepted: 04 January 2023;

Published: 20 January 2023.

Edited by:

Mark Vicars, Victoria University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jonathan Glazzard, Edge Hill University, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Gaur, Saha, Goel, Ovseiko, Aggarwal, Agarwal, Haq, Danda, Hartle, Sandhu and Gupta. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Latika Gupta,  ZHJsYXRpa2FndXB0YUBnbWFpbC5jb20=; orcid.org/0000-0003-2753-2990

ZHJsYXRpa2FndXB0YUBnbWFpbC5jb20=; orcid.org/0000-0003-2753-2990

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.