- 1College of Foreign Languages, Jishou University, Jishou, Hunan, China

- 2School of Foreign Languages, Hunan University of Finance and Economics, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 3College of English, Xi'an International Studies University, Xi'an, Shaanxi, China

The study focuses on the syntactic functions and prosodic features of the turn-media particle dai in Jishou dialect, Hunan Province, China, as well as its distributions and interactional functions across eight different contexts. The research utilizing a corpus of 70 h consisting of 300,000 characters of the Jishou dialect, employed the conversation analysis (CA) method to analyze the interactional behaviors of dai. The results show that dai serves as an overt marker of speakers' negative stances, including complaining and criticizing. It is treated as an emerging product continuously shaped by diverse factors, such as context, sequential positioning, prosodic manifestation in talk-in-interaction, and its influence on the subsequent development of the conversation.

1. Introduction: Particles and language

Particles are ubiquitous in languages across the world. They have been cross-linguistically discussed in terms of their function of marking speakers' stance, e.g., oh in English (Schiffrin, 1987; Heritage, 1998); yo, ne, sa, zo, and no in Japanese (Cook, 1990, 1992; Maynard, 1993, 2002; Tanaka, 1999), and kwun, ney, tela, and ta in Korean (Lee, 1993; Strauss, 2005; Strauss and Ahn, 2007). These particles exist within a wide variety of interactional contexts and serve to express surprise, empathy, and degrees of certainty. Examples of these include “a, ou, ya, ba, ne” in Mandarin (Li and Thompson, 1981; Li et al., 1982; Wu, 1997, 2004), “la, lo, wo” in Cantonese (Luke, 1990; Matthews and Yip, 2013), “nâ, nia” in Thai (Horie and Iwasaki, 1996), and “nii(n), joo, kato” in Finnish (Hakulinen and Seppänen, 1992; Sorjonen, 1997, 2001).

Given the pervasiveness of particles within and across languages and their discourse-pragmatic functions, their research can provide keen insights into the socio-contextual elements that underlie various aspects of speakers' stances in relation to the participants, the theme of the talk, the information presented, and so on.

In the article, conversation analysis (CA) is employed to investigate the interactional functions of one such turn-medial particle,1dai, in the Jishou dialect of Western Hunan Province, China. We chose ‘dai' as the focal point of our study for two reasons: first, it plays a crucial role in indicating the speaker's emotional stance, and second, it is unique to the Jishou dialect and is not present in other dialects spoken in the Hunan Province, as confirmed by both literature and field research. We identified and tracked its usage within a corpus of audio-taped interactions in which native speakers of Jishou interact face-to-face with numerous interlocutors in various contexts. The study illustrates that dai serves as a clear indicator of the speaker's negative stance, and it is utilized by speakers to express complaints and criticisms within negative interactional contexts,2 as is presented in excerpt 1 below:

(1) (Households)

(In this scenario, person M3 believed that person R had already reached his destination, Jishou City. M then expressed her complaint to R over the phone, stating that the train was late. However, it was later revealed that R had only just arrived in Huaihua City, which is a two-hour journey away from Jishou City).

1M: aiyo, cai dao huaihua a.

(exclamation), just arriving in (city) PRT

Uh-oh, (you are) just arriving in Huaihua.

2M: → wo dai: hai yiwei ni zao dao le.

I PRT still thought you early arrive PRV

I DAI thought that you had arrived early.

(in Jishou)

3M: aiyo, na ni xiaci bie zai zuo huoche le.

(exclamation), then you next time N again take train CRS

Ah, then you (had better) not take the train next time.

Excerpt 1 illustrates when the dai turn-at-talk is used to address speaker M's complaints (line 2). Her negative stance can also be seen in her suggestion that R had better not take the train next time (line 3). Prosodically and lexically, the prolonged particle dai and two prefaced exclamations aiyo mainly contribute to achieving a negative affective stance. In the article, we will demonstrate that turn-medial particle dai is an overt marker of an emergent negative stance in talk, showing participants' orientation to complaints and criticisms.

2. Previous research on dai

The Jishou dialect is spoken in an area at the border between the Xiang dialect, which is spoken in Hunan Province, China, and Southwestern Mandarin. It displays characteristics of both dialects, combining features of the Xiang dialect and Southwestern Mandarin in its phonetic system. For instance, when ancient-voiced initials are pronounced as plosives or affricatives, their tones are transformed into Ping-sheng (level ones) in the same unaspirated way as the Xiang dialect does. However, there is no Ru-sheng (entry tone) in the Jishou dialect. Under this condition, ancient Ru-sheng characters are pronounced in a rising tone whose tone pitch is similar to the usual tone pitch of Southwestern Mandarin. Morpho-syntactically, abundant retroflexed er-suffixed (-儿) words, reduplicative constructions, and shared syntax ingredients with Southwestern Mandarin in the Jishou dialect demonstrate that the Jishou dialect is far closer to Southwestern Mandarin than the Xiang dialect (Xiang, 2011). In addition, the fact that ethnic minorities account for 70% of the total population in Jishou city contributes to long-term contact among the Han, Tujia, and Miao populations, with distinctive features of the Jishou dialect induced by regional language contact (Li, 2002; Xiang, 2009).

Typical for the Jishou dialect, the particle dai is common in ordinary conversations. Previous studies on dai (e.g., Li, 2002; Xu, 2006; Yang, 2008) argued morphologically that it serves as an infix in the verb reduplication “V dai V” and adjective reduplication “A dai A.” However, in the former sense, it is placed at the sentence's predicate, as is presented in excerpts 2 and 3. In the latter sense, it acts as the predicate or complement, as is presented in excerpts 4 and 5. Besides, they also point out that the embeddedness of the particle dai adds speakers' subjective stances to their utterances. Thus, “V dai V” and “A dai A,” compared with those without dai, present speakers' stronger deontic modality (Excerpts 2–5 are quoted from Li, 2002: p. 250–258).

(2) wo naoke yun dai yun.

my head faint PRT faint

I am feeling strongly faint.

(3) hu li de shui kai dai kai.

kettle inside PRT water boil PRT boil

The water inside the kettle keeps boiling violently.

(4) na tiao po gao dai gao, pa si ge ren.

that C slope high PRT high, climb exhaust C people

That slope is so high and exhausting to climb up.

(5) ta zuo shi guoxi dai guoxi.

3SG do things careful PRT careful

He is quite conscientious about his work.

Unlike previous research, this study identified 54 instances where dai functions as an infix in verb and adjective reduplication, accounting for only 2% of total occurrences of dai. The remaining 98% function as turn-medial particles, demonstrating that dai plays an important role in interactions among speakers of Jishou, as is presented in excerpt 1.

Given the claims that the turn-medial particle dai is highly emotionally charged and frequently used in interactions, this study, which is based on a corpus of 70 h comprising approximately 300,000 characters of the Jishou dialect, employs CA to explore its interactional functions. This study also seeks to gain a deeper understanding of the functional motivations behind its use, not just through the analysis of specific linguistic features but also by examining the actions and attitudes that it accomplishes in the course of the interaction, as evidenced by the participants' conduct.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. “Section 3” introduces the analytical and methodological framework and provides an overview of the data analyzed, the transcription procedures, and the contextual distribution of dai. “Sections 4 and 5” demonstrate dai's syntactic functions, prosodic features, and sequential functions. “Section 6” presents findings regarding the interactional functions of dai in the initiative and responsive positions. The final section summarizes the findings presented in the main sections and discusses the implications of this study.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. The function of particles in social interaction

CA is a field of research where a conversation is viewed as a primordial site for and a basic form of social interaction, which is this study's major theoretical and methodological framework. Social interaction is structurally organized by participants and is “a describable domain of interactional activity exhibiting stable, orderly properties that are the specific and analyzable achievements of speakers and hearers” (Zimmerman, 1988: 407). The main objective of CA is to examine and describe the structural elements of everyday conversations and other forms of talk-in-interaction that enable people to establish a shared understanding of the interaction.

From a CA perspective, one key aspect that underlies the organization of social interaction is “recipient design,” i.e., “the multitude of respects in which the talk by a party in a conversation is constructed or designed in ways that display an orientation and sensitivity to the particular other(s) who are the co-participants” (Sacks et al., 1974: p. 727). In the organization of their action, participants ordinarily consider the contingencies as they demonstrate in their next moves what sense they make of a prior speaker's action. Accordingly, to understand the participants' “then-relevant” sense of these contingencies, the immediately subsequent moves by participants commonly become analytic loci for CA. In short, this study mainly uses subsequent talk as a “proof procedure” in the analysis.

From the perspective of CA, the interactional functions of the turn-medial particle dai can be accomplished interactionally through the use of linguistic resources or other practices. Thus, the interactional functions of dai are treated as an emerging product that is shaped by and shapes the subsequent development of interaction. In this process, linguistic resources or other practices play a constitutive role in contributing to the functions accomplished by the particle dai. The interactional functions of particle dai are mutually dependent, thereby “maintaining or altering the sense of the activities and unfolding circumstances in which they occur” (Heritage, 1984: p. 140). Our study outlines three major areas for studying the particle's functions: (a) context; (b) sequential positioning; and (c) prosodic manifestation. Our study sheds light on how linguistic resources play a role in achieving social action and mutual understanding, and it can be seen as a contribution to the expanding field of research on Chinese dialects within interactional linguistics.

3.2. The data4 and transcription conventions

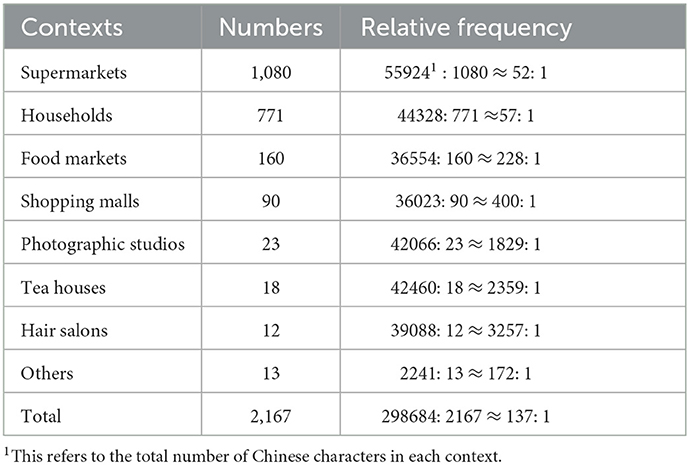

Our study's corpus consists of telephone and face-to-face conversations among family members, friends, or acquaintances. The authors collected these conversations mainly in eight contexts, including supermarkets, households, tea houses, hair salons, shopping malls, food markets, photographic studios, and others in Jishou from December 2012 to July 2021. The corpus comprises approximately 70 h of interaction by 97 participants, including 61 women and 36 men, all of whom are native speakers of the Jishou dialect. Their ages range from the mid-20s to the late 80s. Various contexts and combinations of participants are chosen to guarantee that the research findings are not context- and participant-specific.

The 70 h of interactions were transcribed using the Pinyin romanization system without tone marks, in accordance with the conventions of CA (Atkinson and Heritage, 1984), with slight modifications5.

Each transcribed Jishou dialectal turn is accompanied by two lines of an English translation. The first line provides a literal translation of each Jishou dialectal element, while the second line offers an idiomatic English equivalent, as is shown in excerpts 1–5.

3.3. The contextual distribution of the turn-medial particle dai

3.3.1. The number and relative frequency in eight different contexts

As shown in Table 1, there is a noticeable discrepancy in dai's distribution in eight different contexts. More specifically, out of a total of 2,167 instances in the present corpus, 1,851 instances occur overwhelmingly in supermarkets (1,080) and households (771) contexts, respectively. Other contexts with a dramatically lower frequency of dai are food markets (160), shopping malls (90), photographic studios (23), tea houses (18), hair salons (12), and others (13). A simple calculation reveals that the number of dai in supermarket and family contexts is about six times that of the total number of the other contexts. The data presented in the supermarkets are conversations among four sisters (M, A1, A2, and A3). In contrast, those in the households consist of family members (M, F, and R), demonstrating that the turn-medial particle dai is more likely to be used among participants with more intimate social relationships.

However, as shown in Table 1, although its frequency is lower, the occurrence of dai in seven other contexts involving participants with relatively more distant social relationships is not an isolated linguistic phenomenon. As will be shown later in this article, the speakers' negative stance for complaining and criticizing is displayed and partly achieved by the dai turn-at-talk. In addition, pursuing interpersonal harmony in interaction has been suggested to be the essence of human beings' rationality (Ran, 2012: p. 1); thus, in this study, there are fewer instances of face-threatening dai turns-at-talks in the seven other settings with participants in more distant social relationships, which is understandable.

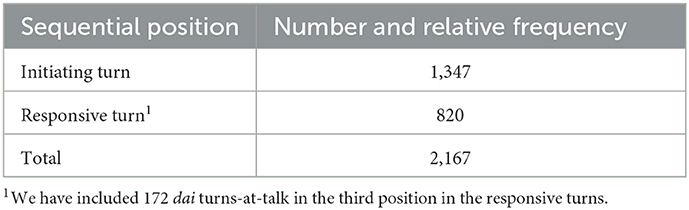

3.3.2. The relative frequency of dai in sequential positions

Sequential position refers to the relative position of adjacent turns within an adjacency pair consisting of two or more turns with conditional relevance in turn-taking (Schegloff, 1996). Previous studies (Schegloff, 1982; Couper-Kuhlen, 1996; Goodwin, 2000; Wu, 2004; Couper-Kuhlen and Selting, 2018) have found an “interaction” between particles' sequential positioning and their syntactic features, meanings, and functions. As Table 2 demonstrates, the turn-medial particle dai in an initiating turn, compared with that in a responsive turn, has a higher relative frequency. The fact that the sequential positioning influences the relative frequency of dai shows an interactive relationship between syntactic features, meanings, and functions of the turn-medial particle dai and its sequential placement in the interaction.

In this section, we have discussed the “interaction” between dai and its distribution in different contexts and sequential positions. Then, the interactional functions of the turn-medial particle dai from the perspective of CA will be described empirically.

4. Syntactic functions and prosodic features of the turn-medial particle dai

To date, there have been very few studies of dai in the Jishou dialect. This section will be dedicated to its syntactic functions and prosodic features.

4.1. Syntactic positions

Syntactically speaking, there are three main positions for the turn-medial particle dai: (1) being between the nominal subject and predicate, as is presented in the excerpts (6a, b); (2) following a sentence-initial adverbial, as is shown in excerpts (6c, d); (3) following a prepositioned object, as is presented in the excerpts (6e, f). Overall, the turn-medial particle dai is referred to as a marker dividing the sentential “theme-rheme.”

(6) a. wo dai yi yang mei de.

I PRT one C N gain

I DAI have gained nothing.

b. ta sun dou hao da le,

3sg grandson already very old PRV,

ni dai hai mei you.

you PRT still N have

His grandson has already grown up to be an

older child (but) you DAI do not have (your own) yet.

c. zhe ge shihou dai loufang hai jicongjicong.

this C time PRT buildings still everywhere

In recent times DAI, buildings exist everywhere.

d. na tian lai dai:

that day come PRT

wo hai yao tamen tuoxie a.

I then ask them take off shoes Q

(Did it mean that) I should ask them to take off (their)

shoes on the day they came DAI (to my house)?

e. rou dai wo de ji ke chi.

meat PRT I get a few C eat

I (only) got a few dices of meat DAI to eat.

f. anhao_anhao dai mei

kan dao.

cipher_cipher PRT N see ASP

(I) have not seen the cipher DAI (at all).

4.2. Sentential functions

The turn-medial particle dai in declarative sentences is shown in excerpts (7a, b ).

(7) a. ta dai gang, zhe shui hui leng.

3sg PRT say, this water will cold

It was him, DAI, who said the water would get colder.

b. dianshi dai ta dou mei kan.

television PRT 3sg already N watch

He hardly ever watches TV DAI.

In addition, the turn-medial particle dai can also be used in exclamatory sentences to express the speaker's assessment directly. As presented in excerpt 7c, dai is mainly used in responsive turns to evaluate a prior turn's statement.

(7)c (Supermarkets)

((A1 and M are making a comparison of transactions between two suppliers))

A1: na ta shengyi mo bu hao a?

then 3sg business Q N good Q

then isn’t his business in good condition?

M:

→ yo:: renjia haoduo dou shi zhijie gei

oh:: others many already be direct give

chaoshi songhuo, ta dai:::

supermarket deliver goods, 3sg PRT

Oh::, many other suppliers directly deliver goods to

supermarkets (this is good business), but he (his business) DAI (is not good)

The turn-medial particle dai is completely incompatible with interrogative and imperative sentences based on the present corpus.

4.3. Prosodic manifestation

There are two types of prosodically different dais in the present corpus; one of them, the unmarked dai, is produced with a flat, low pitch and demonstrates prosodic features closer to what has been described for particles in the literature, while the other, the marked dai (marking as daim), does not. These marked tokens are produced either with a markedly high pitch or with some dynamic pitch movements, such as a rising or a falling-rising pitch contour. The unmarked dai is considered the main prosodic manifestation, as presented in excerpt 8:

(8) a. zhe ge shihou dai loufang hai jicongjicong.

this C time PRT buildings still everywhere

In recent times DAI, buildings exist everywhere.

b. rou dai wo de ji ke chi.

meat PRT I get a few C eat

I (only) got a few dices of meat DAI to eat.

The connotation of a segment following the turn-medial particle dai can be inferred from the context so that speakers can omit the following segments. In this case, dai manifests itself as a marked one, as presented in excerpts 9a and 9b:

(9)a (Food Markets)

((S and D are coworkers in a food market. S grumbles about D's eating outside))

S: wo dengxia chuqu chi suanlafen.

I later go outside to eat (local snack)

I will go outside to eat hot and sour rice noodles later.

D: → wo fan dou bang ni zhu le, ni daim::

I rice already help you cook PRV, you PRT::

I have already cooked the meal for you, but you DAI (do not eat it).

b (Shopping Malls)

((Z is B’s client. They complain about their dark circles to each other))

Z: ni kan wo dou you heiyanquan.

you see, I already have dark circle

Look, I already have dark circles.

B: → wo haiyao geng hei xie, wo daim::

I even more black C, I PRT::

Mine (dark circles) are even worse; my dark circles

DAI (is so heavy).

5. Sequential functions of the turn-medial particle dai

This section presents findings from a detailed analysis of the negative stance marker dai in the initiative and responsive turns, respectively. The particle mainly contributes to achieving a negative stance through increasing variation in volume, pitch, stress, and other prosodic resources; different uses of gestures and other types of embodiment; and accounting or other types of orientations toward these turn-at-talks, etc.

5.1. Initiative turn

In the present corpus, dai occurs regularly in initiating turns where the speaker expresses a complaint or criticism toward a prominent piece of information in that turn, as is illustrated in excerpt 10:

(10) (Households)

(M first complains to F that A1's relatives ate up all the agents' consigned beverages, and then M and F reach an agreement that it is not good for people to drink too many beverages)

1M: → yi jian dai::, aiyou.

one C PRT, (exclamation),

A2 shuo, hai mei fanying guolai,

A2 say, N react ASP,

mei you le.

N have PRV.

A full box DAI (of beverages) , well, A2 said, had been

emptied before others knew it.

2M: A1 la, ta wu naxie qinqi yi lai, jiu

A1 PRT, 3sg family: once those relatives

come,

han tamen chi.

ask them to eat.

When A1’s relatives visit, she always treats them

(with these beverages).

2F: A1 han, [<kuai chi kuai chi

A1 say, [ <quick eat quick eat

A1 told them to drink freely.

3M: um. zhexie chi duo le bu hao.

PRT, these eat many CRS N good.

Um, it is harmful to drink too many beverages.

4M: Tamen shuo hanyou fuermalin, hai you naxie sesu.

they say contain formalin, then have those pigment

They said that there are formalin and pigments in

those beverages.

5F: um, you dian, duoshao you xie.

PRT, have C, more or less have C

True, there are, more or less.

6M: xiaode man, chi naxie chi duo le bu hao a.

know Q, eat those eat many CRS N good PRT

Get it? It is not good for you to drink too many (beverages).

In excerpt 10, the dai turn-at-talk delivers some prominent information about the conversation (line 1); that is, A1 complains that A1's relatives emptied a box full of beverages, and the verbal practice “yi jian dai::/a box full DAI (of beverages)” produced with a prolonged dai invites other speakers to join in with speaker M's complaints and criticisms. Preceding the dai turn, speaker M's complaints and criticisms of A1's selfishness are evident throughout the conversation. Primarily, through the choice of words conveying a sense of complaining (naxie/those, buhao/not good), speaker M expresses a recognizable negative stance. In line 1, M showed her discontent by referring to A1's relatives with the deictic expression “naxie” (those). According to Fang (2002), the deictic word “na” (that) indicates that the stated event lies in the marginal area of a speaker's inner world and is used to express a negative or disapproving stance toward the event. The dai turn-at-talk simultaneously elicits F's evaluation of A1's selfish behavior: given that the practice of giving an identical repetition of A1's utterance “kuaichikuaichi” (eat at a quick pace) in a quick tempo, F vividly depicts the situation where A1 urges her relatives to drink free beverages, implying his complaints on such selfish behavior. Moreover, in lines 4–6, both M and F believe that A1's behavior is not only selfish but harmful to her relatives' health. Lexical and prosodic resources form the evidence of the conversation as being “affect-laden”; reflexively, the dai utterance itself shapes the development of the interaction; that is, as the whole conversation seems to be complaining about the event from the start with the dai turn-at-talk, the negative stance is co-constructed in the whole conversation.

Excerpt 11 provides another instance in which the dai turn-at-talk is used to express complaints and criticism toward a recipient. dai turn-at-talk, in this case, mainly exists among family members:

(11) (Supermarkets)

((M rebukes R for his improper wearing of shoes in the hot summer))

1M: ni dai chuan qi na xiezi huilai,

you PRT wear CRS that shoes back,

zheme re.

so hot.

How could you DAI wear these shoes back in

this heat?

2R: ai::ya::, chuan shenme xiezi? ni xiaode shenme?

(exclamation), wear what shoes? you know what

Ah, what’s wrong with my shoes? You know

nothing (about fashion)

As shown in excerpt 11, M uses dai turn-at-talk to blame R for wearing high heels in the hot summer. Then, R responds to the previous turn with the stressed exclamation “aiya”(Ah) and two consecutive rhetorical questions, expressing his strong impatience. R's responses indicate that he has M's complaints in the previous turn. Considering this, through the selection of “na”(that) as in excerpt 10 and syntactic design—rhetorical questions—speaker M showed her negative stance, and the whole conversation is filled with a negative flavor, such as the prolonged injection aiya.

Despite dai turns-at-talk in the data signaling speaker's negative stance, the above excerpts demonstrate that the particle dai itself can be used to construct complaints and criticisms to some extent. Excerpt 12 is a case in point:

(12) (Supermarkets)

((M, A2, A3 gossip about their relative—CQ. They thought that CQ bought PH a hat because CJ (PH's mother) buys almost all the goods that she needs in CQ's shop.))

1A2: zhe maozi hao chou.

this hat very ugly

This hat is really ugly.

2M: xiao yaer bu guan.

little boy N care

Little boy does not care about that (he wears an ugly hat).

3A2: → ta ((CQ)) dai hao, ta gei ni yaer mai maozi la.

3sg PRT good, 3sg give your child buy hat PRT

She DAI (is) not bad, she bought your son this hat.

4A3: CJ changsi dao ta((CQ)) nail mai dongxi da=

CJ often go 3SG there buy thing PRT=

CJ often goes to her((CQ)) shop to buy something=

5M: =ta ((CJ)) zhaogu ta((CQ)) shengyi da.

=3sg patronize 3sg business PRT

She ((CJ)) patronizes her ((CQ)) place.

6A3: zhe yaer ((CJ)) shenme dou dao ta((CQ)) naer mai,

this guy what all go 3sg there buy

This guy ((CJ)) goes to her ((CQ)) shop

whenever she needs to buy something.

7A3: ni bu gei ta mai, ta bu gei ni yaer mai.

you N give 3sg buy, 3sg N give your child buy

(if) you do not buy something

from her ((CQ)) shop, she will

not buy your child (the hat).

8A3: buguo ta((CQ)) ye keyi, ni de ge maozi dai. hhh

but 3sg also okay, you get C hat wear(laugh)

But she ((CQ)) is not bad, you got a hat from her (at least). hhh

9A2: jiu shi jiang lo, gei ni mai maozi.

then be say PRT, give you buy hat

That’s right. She ((CQ)) bought your (son) a hat.

In excerpt 12, “ta dai hao” (she is not bad) is a format of “dai + good.” The particle dai contributes to the display of a negative stance to some extent, whereas the adjective “hao (good)” usually displays a positive stance. Thus, combining these two words is supposed to accomplish a speaker's mixed stance; that is, the topic in focus is both bad and good. Excerpt 12, involving positive and negative aspects simultaneously on a topic in a conversation, might serve as evidence regarding dai itself as a negative stance marker to some extent. To begin with, in line 1, A2 is saying, “zhe maozi hao chou (This hat is really ugly),” thereby displaying a strong negative stance toward the hat's style and design. Then, M's initiation, “xiao yaer buguan (Little boy does not care about that he wears an ugly hat)” in line 2, elicits A2's response, “ta ((CQ)) dai hao, ta gei ni yaer mai maozi l a(She is not bad, she bought your son this hat.)”. At first, A2 complains that the hat is ugly. M seems to criticize that complaint by claiming that the boy does not care about being ugly, thereby also implicitly defending the giver, and A3 seems to take up on the implicit defense of the giver by explicitly praising the giver for giving the hat. A3's lines 4 and 6 provide evidence for A2's implication: A3 thinks that it is because CJ often takes care of CQ's business that CQ buys a hat for PH, which indicates that this action should not be CQ's willingness but a kind of exchange of benefits. In addition, A2 uses the intensified responsive marker “jiushi jianglo (That's right)” in the closing line 9 to show that she does not just agree with A3 but rather positively assesses that A3 repeated her own previous dai-complaint in line 3 (Qu, 2006: p. 78; Yao, 2012: p. 76). From the above, we can conclude that “ta dai hao” (she is not bad) is a mixed stance toward her (CQ), where the positive aspect comes from the adjective “hao (good)” and the negative aspect, without any doubt, is brought about by the turn-medial particle dai.

5.2. Responsive turn

A speaker mainly uses the turn-medial particle dai in responsive turns to construct a self-accusation when faced with criticisms from others. We count 820 dais in the responsive turn and find that 648 cases, or about 80% of the total, belong to this pattern, as is illustrated in excerpt 13:

(13) (Hair Salons)

((T questions hair stylist H for ignoring his regular customer C10))

1T: ta han ni ji sheng,

3sg call you several sound,

wo kan ni dou mei li ta.

I see you even N respond 3sg

She called you several times, but I saw that you did not

respond to her.

2H: → wo daim zhe tiao yanjing bu ren ren. hhhh Qishi

man, dou shi shuren.

I PRT this C eyes N know person (laugh). Actually PRT, all

be acquaintances

I’m DAI not good at recognizing others. hhhh. Actually we

are all acquaintances.

3T: oh, deng xia gei renjia jieshi yi xia,

PRT, wait C give people explain one C,

Yeah, then you’d better explain to her,

4T: yaoburan jiang ni bu li ren hhhh

otherwise say you N respond people (T and H laugh together)

otherwise, she would think that you ignore her

(deliberately). hhhh

In excerpt 13, in the face of T's blame for “ignoring the regular customer,” H uses a format of “wo daim(I dai) + reason” to express self-accusation in a self-deprecating way. In excerpt 14, J, in the third position in the responsive turns, responds to the blame for “mistaking soy sauce for vinegar” from T and R in the same way.

(14) (Tea Houses)

((T, R and J are close friends. T and R blame J for his mistaking soy sauce for vinegar))

1T: aiya, ni gao shenme la? Shi jiangyou, ni kan qingchu qi lo.

(exclamation), you do what PRT? Be soy sauce, you

see clear ASP PRT

Ah, what are you doing? It is soy sauce (not vinegar),

you had better see more clearly (next time).

2R: na tiao J ou.

That C J PRT.

What a (sloppy) person J is.

3J: → wo daim dou meng le, wo yiwei zhe tiao shi cu.

I PRT even stupid PRV, I think this C be vinegar

I DAI was thoroughly lost, I thought it was vinegar.

4: hhhh.

(J, T and R laugh)

What is notable in the above two excerpts is that their self-deprecating blame on themselves triggers the “laughter” of participants. The laughter, caused by H's neglect of a regular customer and J's ridiculous mistakes, is employed by the speakers simultaneously to alleviate the embarrassment caused by the criticism (Levinson, 1983: p. 70). In other words, the non-verbal practice of “laughter” demonstrates that other participants accurately catch the self-deprecating blame of the speaker's turn.

The turn-medial dai is also used by speakers to directly express negative evaluations of the participants in the interaction. Nevertheless, in line with the politeness principle, such direct complaints and criticism are not common. This conclusion is supported by statistics, which indicate that dai of this type occurs 57 times, accounting for only a small portion (7%) of the entire corpus of 820 dais in responsive turns, as presented in excerpt 15:

(15) (Photographic Studios)

(( A customer complained that studio employee S accidentally deleted a photographic plate. S' boss is now talking to him about it.))

1S: wo gang gen ta jieshi le, ta ziji jiang bu yaojin, ta

diannao litou cun de you.

I just with 3sg explain CRS, 3sg self say N matter,

3sg computer in save CSC have

I just explained it to him, and he said that it did not

matter, for he had already saved them (the pictures) on

his computer.

2Q: → ni daim zuo shi tai meiyou zhuntou le, renjia tousu

ni le, ni hai guai renjia.

You PRT do a thing so N reliability PRT, other

complain you PRT, you still blame other

You DAI are so unreliable. The customer has

complained about you, and you are still blaming

the customer.

3S: na zhende buhaoyisi, wo buxiaoxin shan cuo de.

Then really sorry, I careless deleted mistake ASP

I’m really sorry, then. I deleted (the pictures) by accident.

In excerpt 15, speaker Q's negative stance in line 2 can also be verified from the next turn by recipient S: S uses an apologetic expression “buhaoyisi (I'm sorry)” with an intensifier “zhende (really)” to respond to Q's criticism in the prior marked dai turn, displaying that he orients to dai turn-at-talk as a negative stance-laden statement.

6. Conclusions

Particles are viewed as key contributions to speakers' fluency, although some are stigmatized as informal, disfluent elements of speech (Crible et al., 2017; Degand, 2018; Degand and Van Bergen, 2018). By combining syntax, pragmatic functions, and syntagmatic variables (co-occurrence and clusters of words, pauses, silence, etc.), as well as rich corpus-based observations, our study might obtain a more comprehensive picture of the turn-medial particle dai, which is an overt marker of speakers' negative stance, including complaining and criticizing. The study shows that a negative stance is treated as an emergent product shaped continuously by diverse factors in talk-in-interaction and shapes the subsequent development of conversation. In other words, CA of the turn-medial particle dai takes an interactional approach, which is different from some previous studies of stance (e.g., Biber and Finegan, 1988, 1989; Field, 1997), whose focus has been on the realization of linguistic stance markers. Specifically, the current study is focused on how stance can be accomplished in interaction by means of linguistic and other resources, such as context, sequential positioning, and prosodic manifestation.

Context is a key factor in accomplishing language functions (Hopper, 1998; Heine and Kuteva, 2002). In this study, displaying the negative stance is both “context-sensitive” and “context-renewing.” On the one hand, the turn-medial particle dai exists in contexts featuring complaints and criticisms with high frequency, which further embodies and reinforces its interactional function by absorbing the sense of the complaints and criticisms implied in the context. On the other hand, there is a “reflexive relationship” between the particle dai and the context in which it occurs. The speaker uses it to establish a “stance frame” and sets a baseline of negative evaluation for the subsequent conversation.

Furthermore, the turn-medial particle dai interacts with different sequential positions and realizes multivariate interactional functions. Positioning the particle in the first pair of an adjacency pair allows the speaker to initiate a new sequence and take control of the interaction. Thus, a turn with dai in this sequential position is responsible for drawing the listener's attention to key information in the conversation. When the particle dai is positioned in the second or third part of an adjacency pair, it refers to the current speaker's response and achieves a negative assessment of what others just said or intended in a preceding turn (or turns).

With respect to the prosodic manifestation of the turn-medial particle dai, we noted that there are two types of distinctive dai in the present corpus: the unmarked dai produced with a flat, low pitch, and the marked dai produced either with a markedly high pitch or with some dynamic pitch movements, such as a rising or a falling-rising pitch contour. Unmarked forms occur regularly in initiating turns where speakers complain or criticize a prominent piece of information. Unmarked dai registers the matter being addressed as new information. A speaker mainly uses the unmarked dai in responsive turns to construct a self-accusation when faced with criticism from others.

However, the marked dai is characteristically used to register a stronger negative stance. It is commonly used to alert the recipient to some negatively valenced interactional work that the dai-suffixed turn-at-talk is attempting to accomplish. It is worth noting that the connotation of a segment following a marked dai can be inferred from the context so that speakers can omit the following segment; that is, the dai utterance is prosodically, syntactically, and pragmatically excluded.

The examples in “Section 5” reveal that both dai in initiating turns and in responding turns are indexing a complaint or criticism already established in the sequence. Dai also serves different functions in the first, second, or third positions, whether in a turn of informing or in a turn that both receives and informs. In other words, while unmarked dai in the first pair of an adjacency pair and marked dai in the second or third position can be used to register a new delivery as well as a new assessment, the former characteristically invokes a sense of emphasis, which is not displayed in the latter, and the additional layer of import exhibited in the use of marked dai may be achieved by the interaction among distinctive prosody and sequential position.

Our findings regarding the interactional functions of the turn-medial particle dai, with its distinctive prosodic characteristics, contribute to our existing body of knowledge on the Jishou dialect. The present study, based on an extensive corpus of naturally occurring interactions, is a new attempt to describe and explain the interactional functions of the turn-medial particle dai and the underlying logic and regularity using the CA. The work done here is just the tip of the iceberg; it serves only as a starting point for more investigation. Further CA research is needed to develop the interaction analysis of a wide range of discourse particles in the Jishou dialect from the following three aspects: (1) investigating the actual usage of particles based on naturally occurring interactions; (2) implementing positionally sensitive grammar by carrying out a dynamic analysis of different particles' sequential organization; and (3) exploring the patterns and emergent conditions of different particles. Apart from occurring in both initiative and responsive turns, there seems to be a pattern in the use of the particle dai in the current turn, e.g., X dai, + clause, X dai + the rest of the clause, X daim:::. Its role in these structures may have been different, such as a topic marker for the division of theme and rhyme. As an important discourse marker, the analysis of what particle dai contains should not be limited to the sequential position but its position in the turns. More research is also needed to elucidate this matter.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

FL contributed for article writing. XL and RL for data collection and analysis. JZ for data collection. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (An Interactional Linguistic Study of Mandarin Final Particles) (Grant number: 21BYY162); Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province, China (A conversation analysis of Mandarin Particles) (Grant number: 22A0357) and Research Foundation for Talented Scholars of Jishou University.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1018648/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^It should be noted, however, that the term “particle” is occasionally used as a term of convenience as a substitute for the term “turn-medial particle” in this study.

2. ^“Negative interactional contexts” refer to situations in which speakers express their negative attitudes, potentially challenging the listener's social image, such as through complaints, objections, refusals, warnings, and so on. For example, Wu's (2004) study of final particles in Mandarin Chinese using Conversation Analysis has demonstrated that the particle ou at the end of a turn serves as a warning to the listener of negatively-valenced interactions such as complaints, disagreements, warnings, jokes, declines of requests, rejections of expectations, or denials of presuppositions.

3. ^The main participants' coding is found in Appendix I.

4. ^We have obtained informed consent from the participants in the recordings done in public places.

5. ^The transcription and glossing conventions employed in the excerpts are provided in Appendices II and III.

References

Atkinson, J. M., and Heritage, J. (1984). Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., and Finegan, E. (1988). Adverbial stance types in English. Discourse Process 11, 1–34. doi: 10.1080/01638538809544689

Biber, D., and Finegan, E. (1989). Styles of stance in English: lexical and grammatical marking of evidentiality and affect. Text 9, 93–124. doi: 10.1515/text.1.1989.9.1.93

Cook, H. M. (1990). An indexical account of the Japanese sentence-fifinal particles no. Discourse Processes 13, 401–439. doi: 10.1080/01638539009544768

Cook, H. M. (1992). Meanings of non-referential indexes: a case of the Japanese particle. Text 12, 507–539. doi: 10.1515/text.1.1992.12.4.507

Couper-Kuhlen, E., and Selting, M. (2018). Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crible, L., Degand, L., and Gilquin, G. (2017). The clustering of discourse markers and filled pauses: a corpus-based French-English study of (dis)fluency. Lang. Contrast 17, 69–95. doi: 10.1075/lic.17.1.04cri

Degand, L., and Van Bergen, G. (2018). (2018). Discourse markers as turn-transition devices: evidence from speech and instant messaging. Discourse Processes 55, 47–71. doi: 10.1080/0163853X.2016.1198136

Fang, M. (2002). Zhishici zhe he na zai Beijinghua zhong de yufahua[On the Grammaticalization of Zhe in Beijing Mandarin: from demonstrative to definite article]. Zhongguo Yuwen 4, 343–383.

Field, M. (1997). The role of factive predicates in the indexicalization of stance: a discourse perspective. J. Pragmatics 27, 799–814. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(96)00047-1

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and Embodiment within Situated Human Interaction. J. Pragmatic.32, 1489–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

Hakulinen, A., and Seppänen, E. L. (1992). Finnish kato: from verb to particle. J. Pragmatic. 18, 527–549. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(92)90118-U

Heine, B., and Kuteva, T. (2002). Word Lexicon of Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heritage, J. (1998). Oh-prefaced responses to inquiry. Lang. Soc. 27, 291–334. doi: 10.1017/S0047404500019990

Hopper, J. P. (1998). “Emergent grammar,” in The New Psychology of Language: Cognitive and Functional Approaches to Language Structure, T. Michael. (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 213–3.

Horie, P. I., and Iwasaki, S. (1996). Register and Pragmatic Particles in Thai Conversation, Paper Presented at the Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Languages and Linguistics. Salaya: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidon University.

Li, C. N., and Thompson, A. S. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Li, C. N., Thompson, S. A., and Thompson, R. M. (1982). “The discourse motivation for the Perfect aspect: the Mandarin particle” in Tense-aspect: Between Semantics and Pragmatics, ed P. Hopper (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 19–44.

Luke, K. K. (1990). Utterance Particles in Cantonese Conversation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Maynard, S. K. (1993). Discourse Modality: Subjectivity, Emotion, and Voice in the Japanese Language. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Maynard, S. K. (2002). Linguistic Emotivity: Centrality of Place, the Topic-Comment Dynamic, and an Ideology of ‘Pathos' in Japanese Discourse. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Qu, C. (2006). A Discourse Grammar of Mandarin Chinese. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.

Ran, Y. (2012). Renji jiaowang zhongde hexie guanli moshi jiqi weifan [Rapport management model and conflict speech in interpersonal interaction]. Foreign Lang. Educ. 4, 1–17. doi: 10.16362/j.cnki.cn61-1023/h.2012.04.009

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., and Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50, 696–735. doi: 10.1353/lan.1974.0010

Schegloff, E. A. (1982). Discourse as an interactional achievement: Some uses of uh-huh and other things that come between sentences,” in Analyzing Discourse: Text and Talk, T. Deborah (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press), 71–93.

Schegloff, E. A. (1996). Confirming allusions: toward an empirical account of action. Am. J. Sociol. 1, 161–216. doi: 10.1086/230911

Sorjonen, M. L. (1997). Recipient Activities: Particles nii(n) and joo as Responses in Finnish Conversations. Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

Sorjonen, M. L. (2001). Responding in Conversation: A Study of Response Particles in Finnish. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Strauss, S. (2005). Cognitive realization markers in Korean: a discourse-pragmatic study of the sentence ending particles –kwun, –ney, and –tela. Lang. Sci. 27, 437–480. doi: 10.1016/j.langsci.2004.09.014

Strauss, S., and Ahn, K. (2007). Cognition through the Lens of Discourse and Interaction: The Case of –kwun, -ney, and –tela Japanese/Korean Linguistics. Stanford: CSLI

Tanaka, H. (1999). Turn-Taking in Japanese Conversation: A Study in Grammar and Interaction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Wu, R. J. (1997). Transforming participation frameworks in multi-party Mandarin conversation: the use of discourse particles and body behaviors. Issues Appl. Ling. 8, 97–117. doi: 10.5070/L482005263

Wu, R. J. (2004). Stance in Talk: A Conversation Analysis of Mandarin Final Particles. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Xiang, L. (2009). Xiangxi zizhizhou hanyu fangyan de guishu wenti[Issue on ascription of the dialect of Xiangxi Autonomous Prefecture]. J. Lang. Lit. Studies 2009, 88–90.

Xiang, X. (2011). Constraint reality: linguistic expressions of restrictivity and emotive stances. A discourse-pragmatic study of utterance-final la?h in Shishan (Hainan Island, China). Lingua 8, 1377–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2011.03.002

Xu, W. (2006). Hanyu Chongdieshi Zhuangtaici Fanchou Xitong Yanjiu [A Study of Duplicated Descriptives in Chinese Language]. Shanghai: Dissertation of East Normal University.

Yang, J. (2008). Hanyu Fangyan Xingrongci Chongdieci Yanjiu [A Study of Duplication Adjective in Chinese Language]. Shanghai: Dissertation of Fudan University.

Yao, S. (2012). Ziran Kouyuzhong de Guanlian Biaoji Yanjiu[Connective Markers in Natural Conversation]. Beijing: China Social Science Press.

Keywords: Jishou dialect, turn-medial particle dai, marker of negative affective stance, conversation analysis, interactional (socio) linguistics

Citation: Liu F, Li X, Liu R and Zeng J (2023) Linguistic expressions of negative stances: A conversation analysis of turn-medial particle dai in Jishou dialect (Hunan Province, China). Front. Psychol. 14:1018648. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1018648

Received: 13 August 2022; Accepted: 16 January 2023;

Published: 21 February 2023.

Edited by:

Antonio Bova, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Peter Furko, Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary, HungaryChusni Hadiati, Jenderal Soedirman University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2023 Liu, Li, Liu and Zeng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng Liu,  bGl1ZmVuZ181MTUwQDEyNi5jb20=

bGl1ZmVuZ181MTUwQDEyNi5jb20=

Feng Liu

Feng Liu Xi Li2

Xi Li2