- School of Psychology and Therapeutic Studies, Faculty of Social and Health Sciences, Leeds Trinity University, Leeds, United Kingdom

Problem gambling can cause significant harm, yet rates of gambling continue to increase. Many individuals have the motivation to stop gambling but are unable to transfer these positive intentions into successful behavior change. Implementation intentions, which are goal-directed plans linking cues to behavioral responses, can help bridge the gap between intention and many health behaviors. However, despite the strategy demonstrating popularity in the field of health psychology, its use in the area of gambling research has been limited. This mini review illustrates how implementation intentions can be used to facilitate change in gambling behavior. Adopting the strategy could help reduce the number of people with gambling problems.

Introduction

Gambling disorders, problem gambling, and excessive gambling can be detrimental to a person’s health. It can lead to negative consequences such as depression, unemployment, financial distress, relationship problems, and criminal behavior (Afifi et al., 2016; Bond et al., 2016; Adolphe et al., 2019; Muggleton et al., 2021). Problem gambling can co-occur with other behavioral addictions (Kessler et al., 2008; Konkolÿ Thege et al., 2016), have considerable impact on close ones (Goodwin et al., 2017), and potentially lead to suicide ideation and behavior (Wardle and McManus, 2021). It is estimated that problem gamblers account for between 0.1 and 5.8% of the population (Williams et al., 2012; Calado and Griffiths, 2016).

Problem gambling has been an issue in Western society for decades, though the availability and opportunity to gamble has increased significantly over the past few years (Abbott, 2020). For example, the recent growth in internet and online gambling has had a major impact on the gambling experience (Gainsbury, 2015). Among the many advantages, internet gambling is highly accessible, convenient to users, and can be undertaken anonymously (Gainsbury et al., 2012). There has also been a rapid rise in gambling advertisements with gambling companies offering free bets, enhanced odds, sign up bonuses, and money back guarantees (Clemens et al., 2017; Rawat et al., 2020). Due to the availability of gambling and the influence of promotional campaigns, it is predicted that gambling is not going to abate in the future (Hodgins and Stevens, 2021). Thus, there is a need for interventions to successfully intervene on and reduce gambling behavior.

Motivation toward gambling

Understanding and explaining human behavior can be achieved using social cognition theories and models, such as the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), and social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986). These approaches identify the mechanisms through which psychological beliefs and determinants influence behavior. As well as understanding behavior, these theories can also inform the development of behavior change interventions. Specifically, the theories can identify the important and modifiable psychological determinants that interventions should target. For illustrative purposes and due to its popularity in the health domain, the theory of planned behavior will be the focus of this paper.

The theory of planned behavior places intention as the proximal determinant of behavior. Intention represents a person’s motivation and willingness to engage in the behavior and is determined by attitude (i.e., behavioral evaluations), subjective norm (i.e., perceived approval of others), and perceived behavioral control (i.e., perceived control over the behavior). A large body of research has attested to the utility of the theory in understanding why people do or do not engage in health promoting or health risk behaviors. The theory has been found to account for between 40 and 45% of the variance in intention and 19–36% of the variance in behavior (e.g., Armitage and Conner, 2001; Hagger et al., 2002; McEachan et al., 2011). Although research applied to gambling has been limited, some studies have used the theory to understand gambling intentions and behavior (e.g., Martin et al., 2010; Wu and Tang, 2012; St-Pierre et al., 2015; St Quinton, 2021). Wu and Tang (2012) and Martin et al. (2010) found gambling intentions to be predicted by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Similarly, St-Pierre et al. (2015) identified intention to be predicted by attitude and perceived behavioral control. In relation to gambling behavior, research has found intention to be a significant predictor (Wu and Tang, 2012; St Quinton, 2021).

The intention-behavior gap

The theory of planned behavior has accounted for impressive variance in intention towards health behaviors, including gambling. However, there is a well-known gap between what people intend to do and what actually occurs (Sheeran and Webb, 2016). Experimental evidence has demonstrated that medium-to-large changes in intention results in only small-to-medium changes in behavior (Webb and Sheeran, 2006). The successful enaction of intention often involves overcoming setbacks, not giving in to temptations, and staying on track (Heckhausen and Gollwitzer, 1987; Schwarzer and Luszczynska, 2008). In relation to gambling, individuals may have the intention to limit or abstain from the behavior but nevertheless proceed to gamble. Indeed, evidence has shown that a large proportion of those with the motivation or intention to stop gambling often relapse (Hodgins and el-Guebaly, 2004; Smith et al., 2015), and a significant number drop out from gambling-related treatment (Pfund et al., 2021). Given the theory of planned behavior specifies intention as the proximal determinant of behavior, the model has been suggested to be unable to account fully for behavior (Sniehotta et al., 2014). The question remains as to how those intending to refrain or abstain from gambling can be facilitated in doing so.

Implementation intentions

To account for the gap between intention and behavior, various strategies and models have been developed. In health psychology, research has found the benefits of planning, specifically implementation intentions. Implementation intentions are goal-directed plans formed based on what, when, where, and how the behavior will be undertaken. To develop an implementation intention, two important aspects must be considered (Gollwitzer, 2014). First, one must identify a cue or critical situation. These can be cues facilitating the behavior or cues related to barriers to be overcome. Second, an appropriate behavioral response must be linked to the situation. These behavioral responses are behaviors to be undertaken once the cue is encountered. Implementation intentions are effective because deliberately identifying cues improves perceptual readiness and once encountered, automatically elicits the behavioral response (Webb and Sheeran, 2004; Gollwitzer, 2014). The effectiveness of these plans can be increased when an “if/then” format is used to link the cue to the response. For example, a person wishing to stop gambling may state “If I am asked to go to a casino, then I will remind myself of the money I will likely lose.” Here, encountering the proposition to attend the casino will automatically elicit a reminder of the potential negative consequences.

It is important to note that an implementation intention is not a motivational strategy, and its effectiveness is not due to increased motivation (Webb and Sheeran, 2008). That is because planning focuses on increasing opportunities to undertake the behavior, not on increasing motivation toward the behavior. An individual without a positive intention is unlikely to strengthen their motivation due to developing a plan. However, the effectiveness of planning depends on the presence of motivation. That is, the extent to which planning is successful depends on a person’s willingness to either engage or not engage in the focal behavior. In fact, the effectiveness of implementation intentions can be improved in the presence of strong intentions (Prestwich and Kellar, 2014). Thus, a pre-requisite to planning is a (strong) behavioral intention or (strong) motivation toward the behavior.

Implementation intentions can be self-generated where the researcher or health provider instructs the person to develop their own plans. Specifically, they are asked to identify situational cues and link with appropriate behavioral responses. Given the person develops their own cues and responses, commitment to the plans can be enhanced (Sniehotta, 2009). Alternatively, implementation intentions can be provided by the researcher or health provider. Armitage (2008) developed volitional help sheets which include a number of situational cues and behavioral responses. The individual is instructed to make links between the cues and outcomes deemed most relevant or salient to them. Although this does not guarantee the cues and responses will be applicable to all, this does circumvent any difficulty the person may have in generating their own plans.

Evidence has demonstrated implementation intentions to be effective in promoting behavior (Gollwitzer and Sheeran, 2006), including those related to health (Prestwich et al., 2003; Gollwitzer and Sheeran, 2006; Hagger and Luszcynska, 2014; Presseau et al., 2017). Gollwitzer and Sheeran (2006) showed implementation intentions had moderate-to large effects on health behaviors. Presseau et al. (2017) identified planning had a small-to-medium effect on objectively measured health behavior and a medium effect on self-reported health behavior. Despite these considerable behavioral effects, the use of implementation intentions has been limited in gambling research (Rodda et al., 2020). For example, a systematic review conducted by St Quinton et al. (2022) identified 18 strategies were used in interventions targeting adolescent gambling. However, planning was not included in any intervention. Furthermore, Rodda et al. (2018) did find action planning was used by problem gamblers during online forums. However, it is unclear whether the plans were developed and enacted in the form of implementation intentions. Finally, Rodda et al. (2017) found that despite the uptake of many behavioral strategies, including planning, their use in gambling prevention is often not maintained. Therefore, there is a gap for implementation intentions to be used in this area.

It is worth noting that implementation intentions share similarities with other treatments used to modify risky behavior, such as gambling. For example, therapeutic approaches such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing often attempt relapse prevention by identifying triggers. However, there are important differences between these approaches and implementation intentions. For example, although clients undertaking cognitive behavioral therapy are often asked to specify when and where they will strive for their goals, therapists rarely prompt clients to link a critical cue with a goal-directed response (Duhne et al., 2020). Moreover, unlike these treatment approaches, the adoption of implementation intentions does not necessitate communication between a client and interventionist (Wittleder et al., 2019). Evidence has also shown implementation intentions can be more effective than these therapeutic approaches (e.g., Varley et al., 2011; Mutter et al., 2020).

Implementation intentions and gambling

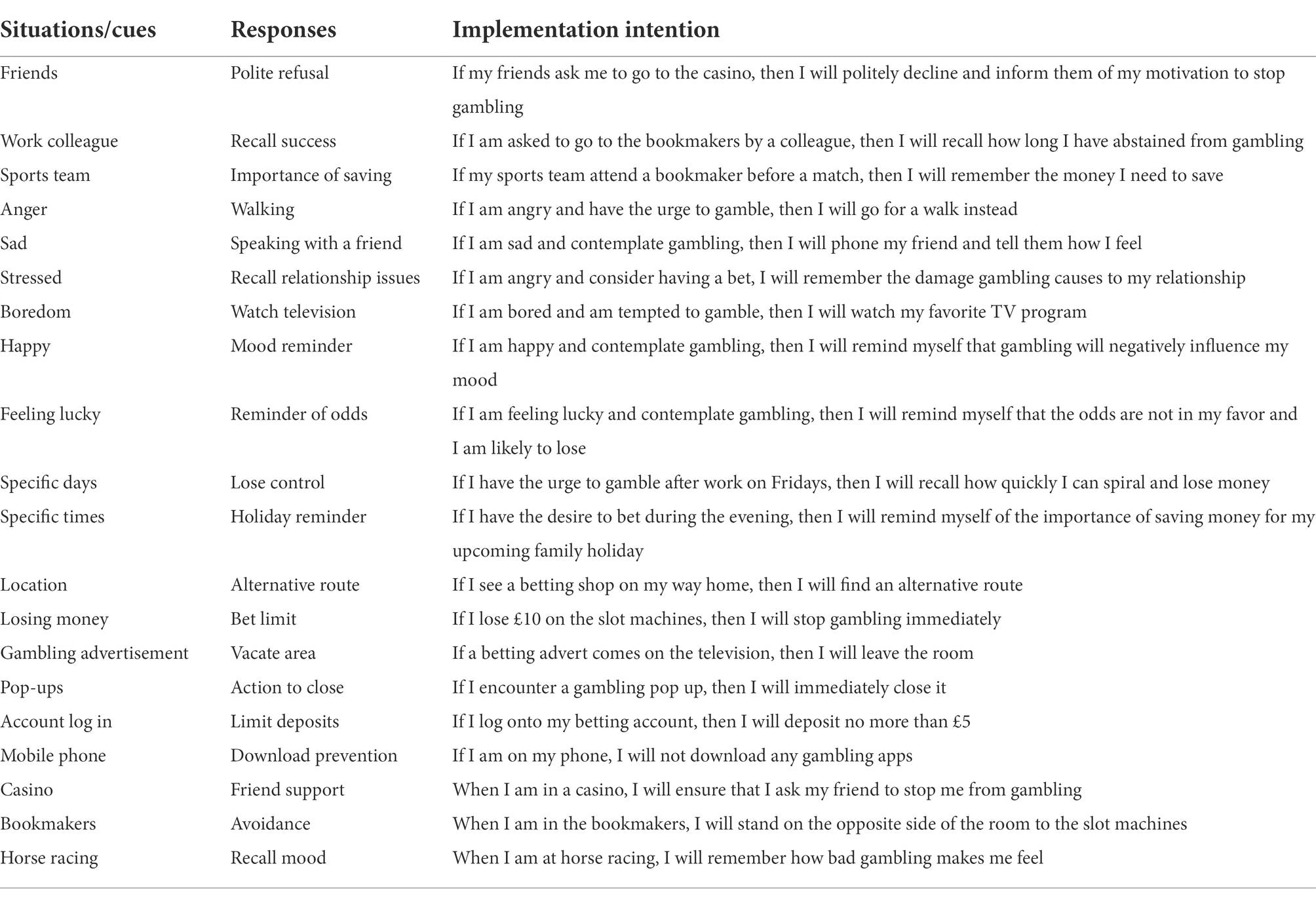

Individuals intending to quit or limit their gambling often fail to follow through on these good intentions (Hodgins, and el-Guebaly, N., 2004; Smith et al., 2015). There are many factors that can interfere with these intentions. However, adopting implementation intentions could prevent motivation to refrain from gambling being derailed. Examples of how implementation intentions could be used are described next, but additional situations and responses are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of situations, responses, and implementation intentions related to gambling prevention.

Gambling is often undertaken as a social activity and can be influenced by the behaviors and actions of others (Zhai et al., 2017; Mazar et al., 2018). Such referents can include friends, work colleagues, and social groups (i.e., sports teams, book clubs, and gym classes). Although these referents can support gambling abstinence, they may also have a negative influence by encouraging it. However, the negative influence of these groups can be subsided through implementation intentions. Consider a person invited to a casino by a group of friends. Now, this person could develop a plan that responds to the invitation. For example, the individual may state “If my friends ask me to go to the casino, then I will politely decline and inform them of my motivation to stop gambling.” In this way, encountering the situation (the invitation) would automatically lead to a positive behavioral response (the polite refusal). The implementation intention therefore protects the motivation or intention to abstain from gambling without having the need for conscious deliberation. As another example, a colleague may frequently visit a bookmaker during lunchtime. When asked by the colleague whether they would like to accompany them one day, the implementation intention “If I am asked to go to the bookmakers by a colleague, then I will recall how much money I have saved through gambling abstinence” could facilitate a positive behavioral response. Again, the plan put in place means the response is guided automatically when the situation is encountered.

These examples use implementation intentions to avoid entering a gambling facility. However, this may not always be preferred or needed. For example, in example 1, the individual may believe that refusing to go along to the casino with friends is likely to cause upset or disappointment. However, an implementation intention could be developed to elicit positive behavioral responses in these locations (e.g., “When I am in a casino, I will ensure that I ask my friend to stop me from gambling”). Similarly, the person in example 2 may feel confident going into the bookmakers but have concerns about abstaining from the slot machines. To facilitate abstinence, a plan such as “When I am in the bookmakers, I will stand on the opposite side of the room to the slot machines” could be used. Additionally, these examples relate to intentions to abstain from gambling, but the same logic would apply to limiting gambling. For example, example one could be modified to “If I am asked to go to the bookmakers by a colleague, then I will accept but put no more than £5 into the machine” or “If I lose £5 on the slot machine, then I will stop gambling immediately.”

In addition to social influences, gambling can be triggered by specific negative emotions, such as stress, boredom, or anger (Buchanan et al., 2020; Kılıç et al., 2020). Implementation intentions can be used overcome these emotions. An individual prone to gambling when angry could plan “If I am angry and have the urge to gamble, then I will go for a walk instead.” In addition to negative emotions, gambling can be influenced by positive emotions (Rogier et al., 2022). A plan could be developed to prevent such feelings leading to gambling. For example, an implementation intention could state “If I am happy and contemplate gambling, then I will remind myself that gambling will negatively influence my mood.”

There may be specific times or days when gambling are more likely to occur (Morasco et al., 2007). For example, an individual could be more susceptible to gambling during the evening or after finishing work on a particular day. Implementation intentions such as “If I have the urge to gamble after work on Fridays, then I will recall how quickly I can spiral and lose money” and “If I have the desire to bet during the evening, then I will remind myself of the importance of saving money for my upcoming family holiday” could protect motivation toward abstinence. Finally, planning could be used to limit the influence of gambling advertisements, promotions, and pop-ups. Consider a person sitting watching a football match on television and a gambling advert appears on the screen with various enhanced odds for the match. This could make the person want to have a bet on the match. However, the implementation intention “If a betting advert comes on the television, then I will leave the room” could deter them from doing so.

These examples and those provided in Table 1 are not exhaustive as there will be many other circumstances and situations associated with gambling. Additionally, variability will exist in the effect of eliciting cues. For example, one individual may be inclined to gamble when stressed whereas another person may not. Moreover, the automatic behavioral responses will not be pertinent for each person; two people may be tempted to gamble in the evening, but only one may be influenced by a reminder that they are saving for a family holiday. It is therefore important that plans are relevant to the person wishing to abstain from gambling. Specifically, the situation and cues need to be considered carefully to elicit positive behavioral change. Plan effectiveness is also likely to be determined by the severity of the gambling problem. For example, planning for what happens when entering the casino may not be effective those with a severe gambling problem.

Implications for gambling

Abstaining from or limiting gambling can be a difficult challenge, even in the presence of strong motivation. Planning how this is going to be achieved can produce effective behavior change. Several recommendations can be made for the use of implementation intentions.

It is important that people are motivated to either limit or refrain from future gambling. That is because without an intention to do so, planning is unlikely to be successful. In the absence of a positive intention, motivational models, such as the theory of planned behavior, should be sought. These models can identify why a person is lacking motivation to change, and interventions can be developed accordingly. For example, some individuals may perceive odds to be in their favor or believe roulette outcomes can be predicted. In these instances, education could be useful to modify these erroneous attitudes.

In the absence of an intention to change, focus should be given to motivation. But the ceiling of motivation means this is usually insufficient to modify gambling behavior. Interventions should therefore introduce planning strategies to facilitate positive intentions. Given the ease of which planning interventions or instructions can be delivered, there is vast potential for its use in the gambling domain. Research in health psychology has recently adopted the use of technology to deliver behavioral interventions. For example, popularity has risen in interventions adopting a mobile device (Steinhubl et al., 2015). Given the number of people using mobile phones to gamble (James et al., 2017); this could be an effective mode to prevent it. This may be especially useful given a large proportion of gamblers are unwilling to seek face-to-face help (Gainsbury et al., 2014). Communication could be made through text messages, emails, or mobile applications. For example, a text message could notify the user to develop an implementation intention, or a mobile application could instruct on how gambling abstinence can be achieved through planning. Bi-directional communication could be adopted whereby the user responds to such requests, and the implementation intentions are checked by the provider.

The optimal effectiveness of implementation intentions depends on ensuring aspects of fidelity. Firstly, it is important that the planning instructions are delivered in accordance with the strategy. If recommending implementation intentions, clear instructions need to be provided related to the identification of situations and behavioral responses. If, however, cues and behavioral responses are provided, then careful consideration must be given to ensure these are prominently associated with gambling. Secondly, it is important that the person wishing to abstain from gambling adheres to the instructions given. For example, failure to pair risky situations with critical responses would undermine the psychology underlying the effectiveness of planning.

Conclusion

Abstaining from or limiting gambling behavior is difficult and motivation is often insufficient. A useful strategy facilitating motivation is implementation intentions, a specific type of planning. The importance of both motivation and implementation intentions can be illustrated by considering the following: there is one individual with strong motivation to stop gambling. Now, this individual does not plan for circumstances that may deter influence motivation to refrain from gambling. When encountering many unanticipated events, the individual fails to implement the intention by proceeding to gamble. There is a second individual with the same strong intention to refrain from gambling. Unlike the first individual, this person has also developed specific implementation intentions after considering potential barriers. When this person encounters the same unanticipated events as example 1, they are able overcome them and follow through on their intention to abstain from gambling. Therefore, those with a strong intention to refrain from gambling plus implementation intentions may be better placed to reduce or abstain from gambling. Consequently, implementation intentions should be utilized by those wishing to modify their gambling behavior.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbott, M. W. (2020). The changing epidemiology of gambling disorder and gambling-related harm: public health implications. Public Health 184, 41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.003

Adolphe, A., Khatib, L., van Golde, C., Gainsbury, S. M., and Blaszczynski, A. (2019). Crime and gambling disorders: a systematic review. J. Gambl. Stud. 35, 395–414. doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9794-7

Afifi, T. O., Nicholson, R., Martins, S. S., and Sareen, J. (2016). A longitudinal study of the temporal relation between problem gambling and mental and substance use disorders among young adults. Can. J. Psychiatr. 61, 102–111. doi: 10.1177/0706743715625950

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Armitage, C. J. (2008). A volitional help sheet to encourage smoking cessation: a randomized exploratory trial. Health Psychol. 27, 557–566. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.557

Armitage, C. J., and Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 40, 471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Bond, K. S., Jorm, A. F., Miller, H. E., Rodda, S. N., Reavley, N. J., Kelly, C. M., et al. (2016). How a concerned family member, friend or member of the public can help someone with gambling problems: a Delphi consensus study. BMC Psychology 4:1. doi: 10.1186/s40359-016-0110-y

Buchanan, T. W., McMullin, S. D., Baxley, C., and Weinstock, J. (2020). Stress and gambling. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 31, 8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.09.004

Calado, F., and Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Problem gambling worldwide: an update and systematic review of empirical research (2000-2015). J. Behav. Addict. 5, 592–613. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.073

Clemens, F., Hanewinkel, R., and Morgenstern, M. (2017). Exposure to gambling advertisements and gambling behavior in young people. J. Gambl. Stud. 33, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9606-x

Duhne, P. G. S., Horan, A. J., Ross, C., Webb, T. L., and Hardy, G. E. (2020). Assessing and promoting the use of implementation intentions in clinical practice. Soc. Sci. Med. 265:113490. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113490

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley

Gainsbury, S. M. (2015). Online gambling addiction: the relationship between internet gambling and disordered gambling. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2, 185–193. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0057-8

Gainsbury, S., Hing, N., and Suhonen, N. (2014). Professional help-seeking for gambling problems: awareness, barriers and motivators for treatment. J. Gambl. Stud. 30, 503–519. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9373-x

Gainsbury, S., Wood, R., Russell, A., Hing, N., and Blaszczynski, A. (2012). A digital revolution: comparison of demographic profiles, attitudes and gambling behavior of internet and non-internet gamblers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28, 1388–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.02.024

Gollwitzer, P. M. (2014). Weakness of the will: is a quick fix possible? Motiv. Emot. 38, 305–322. doi: 10.1007/s11031-014-9416-3

Gollwitzer, P. M., and Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta‐analysis of effects and processes. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 69–119.

Goodwin, B. C., Browne, M., Rockloff, M., and Rose, J. (2017). A typical problem gambler affects six others. Int. Gambl. Stud. 17, 276–289. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2017.1331252

Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., and Biddle, S. J. H. (2002). A meta-analytic review of the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior in physical activity: predictive validity and the contribution of additional variables. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 24, 3–32. doi: 10.1123/jsep.24.1.3

Hagger, M. S., and Luszczynska, A. (2014). Planning interventions: the way forward. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being. 6, 1–47. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12017

Heckhausen, H., and Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motiv. Emot. 11, 101–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00992338

Hodgins, D. C., and el-Guebaly, N. (2004). Retrospective and prospective reports of precipitants to relapse in pathological gambling. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 72, 72–80. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.72

Hodgins, D. C., and Stevens, R. M. G. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on gambling and gambling disorder: emerging data. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 34, 332–343. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000709

James, R. J. E., O’Malley, C., and Tunney, R. J. (2017). Understanding the psychology of mobile gambling: a behavioural synthesis. Br. J. Psychol. 108, 608–625. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12226

Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Winters, K. C., et al. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol. Med. 38, 1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900

Kılıç, A., van Tilburg, W. A. P., and Igou, E. R. (2020). Risk-taking increases under boredom. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 33, 257–269. doi: 10.1002/bdm.2160

Konkolÿ Thege, B., Hodgins, D. C., and Wild, T. C. (2016). Co-occurring substance-related and behavioral addiction problems: a person-centered, lay epidemiology approach. J. Behav. Addict. 5, 614–622. doi: 10.1556/2006.5.2016.079

Martin, R. J., Usdan, S., Nelson, S., Umstattd, M. R., LaPlante, D., Perko, M., et al. (2010). Using the theory of planned behavior to predict gambling behavior. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 24, 89–97. doi: 10.1037/a0018452

Mazar, A., Williams, R. J., Stanek, E. J., Zorn, M., and Volberg, R. A. (2018). The importance of friends and family to recreational gambling, at-risk gambling, and problem gambling. BMC Public Health 18:1080. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5988-2

McEachan, R. R. C., Conner, M., Taylor, N. J., and Lawton, R. J. (2011). Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 5, 97–144. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2010.521684

Morasco, B. J., Weinstock, J., Ledgerwood, D. M., and Petry, N. M. (2007). Psychological factors that promote and inhibit pathological gambling. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 14, 208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.02.005

Muggleton, N., Parpart, P., Newall, P., Leake, D., Gathergood, J., and Stewart, N. (2021). The association between gambling and financial, social and health outcomes in big financial data. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 319–326. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01045-w

Mutter, E. R., Oettingen, G., and Gollwitzer, P. M. (2020). An online randomised controlled trial of mental contrasting with implementation intentions as a smoking behaviour change intervention. Psychol. Health 35, 318–345. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2019.1634200

Pfund, R. A., Peter, S. C., McAfee, N. W., Ginley, M. K., Whelan, J. P., and Meyers, A. W. (2021). Dropout from face-to-face, multi-session psychological treatments for problem and disordered gambling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 35, 901–913. doi: 10.1037/adb0000710

Presseau, J., Squires, J., Patey, A., Francis, J., Asad, S., Simard, S., et al. (2017). Cochrane review and meta-analysis of trials of action and/or coping planning for health behaviour change. Eur. Health Psychol. 19:885.

Prestwich, A., and Kellar, I. (2014). How can the impact of implementation intentions as a behaviour change intervention be improved? Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 64, 35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2010.03.003

Prestwich, A., Lawton, R., and Conner, M. (2003). The use of implementation intentions and the decision balance sheet in promoting exercise behaviour. Psychol. Health 18, 707–721. doi: 10.1080/08870440310001594493

Rawat, V., Hing, N., and Russell, A. M. T. (2020). What’s the message? A content analysis of emails and texts received from wagering operators during sports and racing events. J. Gambl. Stud. 36, 1107–1121. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09896-3

Rodda, S. N., Bagot, K. L., Manning, V., and Lubman, D. I. (2020). An exploratory RCT to support gamblers’ intentions to stick to monetary limits: a brief intervention using action and coping planning. J. Gambl. Stud. 36, 387–404. doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09873-w

Rodda, S. N., Hing, N., Hodgins, D. C., Cheetham, A., Dickins, M., and Lubman, D. I. (2017). Change strategies and associated implementation challenges: an analysis of online Counselling sessions. J. Gambl. Stud. 33, 955–973. doi: 10.1007/s10899-016-9661-3

Rodda, S. N., Hing, N., Hodgins, D. C., Cheetham, A., Dickins, M., and Lubman, D. I. (2018). Behaviour change strategies for problem gambling: an analysis of online posts. Int. Gambl. Stud. 18, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2018.1432670

Rogier, G., Colombi, F., and Velotti, P. (2022). A brief report on dysregulation of positive emotions and impulsivity: their roles in gambling disorder. Curr. Psychol. 41, 1835–1841. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00638-y

Schwarzer, R., and Luszczynska, A. (2008). How to overcome health-compromising behaviors: the health action process approach. Eur. Psychol. 13, 141–151. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.13.2.141

Sheeran, P., and Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention–behavior gap. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 10, 503–518. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12265

Smith, D. P., Battersby, M. W., Pols, R. G., Harvey, P. W., Oakes, J. E., and Baigent, M. F. (2015). Predictors of relapse in problem gambling: a prospective cohort study. J. Gambl. Stud. 31, 299–313. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9408-3

Sniehotta, F. F. (2009). Towards a theory of intentional behaviour change: plans, planning, and self-regulation. Br. J. Health Psychol. 14, 261–273. doi: 10.1348/135910708X389042

Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., and Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 8, 1–7. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.869710

St Quinton, T. (2021). A reasoned action approach to understand mobile gambling behavior among college students. Curr. Psychol. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01656-0

St Quinton, T., Morris, B., Pickering, D., and Smith, D. M. (2022). Behavior change techniques and delivery modes in interventions targeting adolescent gambling: a systematic review. J. Gambl. Stud. doi: 10.1007/s10899-022-10108-8 [Epub ahead of print].

Steinhubl, S. R., Muse, E. D., and Topol, E. J. (2015). The emerging field of mobile health. Sci. Transl. Med. 7:283rv3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3487

St-Pierre, R. A., Derevensky, J. L., Temcheff, C. E., and Gupta, R. (2015). Adolescent gambling and problem gambling: examination of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Int. Gambl. Stud. 15, 506–525. doi: 10.1080/14459795.2015.1079640

Varley, R., Webb, T. L., and Sheeran, P. (2011). Making self-help more helpful: a randomized controlled trial of the impact of augmenting self-help materials with implementation intentions on promoting the effective self-management of anxiety symptoms. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 79, 123–128. doi: 10.1037/a0021889

Wardle, H., and McManus, S. (2021). Suicidality and gambling among young adults in Great Britain: results from a cross-sectional online survey. Lancet Public Health 6, e39–e49. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30232-2

Webb, T. L., and Sheeran, P. (2004). Identifying good opportunities to act: implementation intentions and cue discrimination. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 34, 407–419. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.205

Webb, T. L., and Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 132, 249–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249

Webb, T. L., and Sheeran, P. (2008). Mechanisms of implementation intention effects: the role of goal intentions, self-efficacy, and accessibility of plan components. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 373–395. doi: 10.1348/014466607X267010

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., and Stevens, R. M. (2012). “The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends”. Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Wittleder, S., Kappes, A., and Oettingen, G., Gollwitzer, PM., Jay, M., and Morgenstern, J. (2019). Mental contrasting with implementation intentions reduces drinking when drinking is hazardous: an online self-regulation intervention. Health Educ. Behav. 46, 666–676. doi: 10.1177/1090198119826284

Wu, A. M. S., and Tang, C. S.-K. (2012). Problem gambling of Chinese college students: application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Gambl. Stud. 28, 315–324. doi: 10.1007/s10899-011-9250-4

Keywords: implementation intentions, motivation, gambling, planning, intention

Citation: St Quinton T (2022) How can implementation intentions be used to modify gambling behavior? Front. Psychol. 13:957120. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.957120

Edited by:

Richard J. Tunney, Aston University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Neven Ricijas, University of Zagreb, CroatiaCopyright © 2022 St Quinton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tom St Quinton, dC5zdHF1aW50b25AbGVlZHN0cmluaXR5LmFjLnVr

Tom St Quinton

Tom St Quinton