- 1School of Health Sciences of Polytechnic of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

- 2Centre for Innovative Care and Health Technology (ciTechCare), Polytechnic of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

- 3Research in Education and Community Intervention (RECI I&D), Piaget Institute, Viseu, Portugal

- 4Palliative and Supportive Care Service and Institute of Higher Education and Research in Healthcare, Lausanne University Hospital, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

- 5HESAV School of Health Sciences, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western, Lausanne, Switzerland

- 6High School of Health (HEdS), Geneva, Switzerland

- 7Department of Readaptation and Geriatrics, Palliative Medicine Division, University Hospital Geneva and University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

- 8Center for Health Technology and Services Research (CINTESIS), NursID, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Introduction

Times of crisis are times of suffering and pain and opportunities for transformation. Beyond the current debate on measures to combat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), one must consider two consequences of the pandemic that can be opportunities to foster spiritual well-being (Stilos et al., 2021) and exercise hope in palliative care.

First, the pandemic made us remember our human fragility (Bunkers, 2020; Lozupone et al., 2020). The trail of death, fear, and social paralysis brought on by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has imposed a heavy blow against the dictatorship of human narcissism and exposed our human frailty before an invisible and insidious threat that separates us from our loved ones. In this perspective, there are paths of spirituality leading deep into ourselves, introspectively, in search of meaning and connection with others, toward transcendence and the Divine (Steinhauser et al., 2017; Worth and Smith, 2021). Greater spiritual well-being is closely tied with a sense of dignity and self-worth, of having lived a full and fulfilling life (Roman et al., 2020). Evidence indicates that spirituality has an essential role in mental and physical health, serving as a protective element during psychological adjustment to unpleasant situations (Niemiec et al., 2020).

Second, in addition to our fragility, this new reality reminds us that we are mutually dependent beings. No one can take care of themselves alone in the face of disease, bringing us to the edge of our finitude. We are social beings, created for solidarity, connection, and affection. We could use these unprecedented times to experience deeper connectivity with what and who matters (Long et al., 2022).

Given the psychological consequences of COVID-19-related stressors, positive and hopeful thinking may be a beneficial resource that allows individuals to maintain or regain their well-being (Hamouche, 2020; Büssing et al., 2021; Counted et al., 2022). Fostering education on the pedagogy of hope and its ties with spiritual well-being (Jaiswal et al., 2014) can contribute to education for alterity. In alterity, commitment to hope implies a pledge to create conditions and dynamics of hope for others. Only then can there be an effective change in attitudes and the creation of civic awareness of the responsibility in constructing a society of hope. Addressing spirituality and hope may improve knowledge of healthy human functioning and flourishing mental health, as well as represent “life worth living” in general (Rego and Nunes, 2019). Spirituality and character strengths, like hope, can both promote greater wholeness in one's psycho-spiritual journey and contribute to the communal good (Niemiec et al., 2020).

Herein, we intend to underline and reflect on hope as a practice of spiritual care in palliative care, especially because hope is, itself, a pedagogy of life that helps one fulfill themselves as a person. We highlight the exercise of hope in end-of-life contexts, particularly in the training of palliative care professionals.

Promoting Hope As Spiritual Care

According to Leget (2018), spiritual needs can be apparent, implicit, or even buried, and they can be interwoven with other sorts of needs. This definition is based on three basic notions: the sacred or transcendent; a relationship with the sacred; and the search for ultimate meaning or purpose (Peterson and Seligman, 2004; Mayseless and Russo-Netzer, 2017; Niemiec et al., 2020).

By placing a relatively new emphasis on character strengths and virtues, positive psychology can help position spirituality as a human character strength. Following the Platonic and Aristotelian traditions, the Values-In-Action (VIA) framework considers transcendence as a virtue, which includes character strengths, such as spirituality, gratitude, and hope (Peterson and Seligman, 2004; Kor et al., 2019).

In this context, hope is conceptualized as a positive character trait that enables individuals to thrive and flourish (Kor et al., 2019; Niemiec et al., 2020), based not on external results (such as expectation), but on one's personal fulfillment (a radical change in the human condition) (Pinsent, 2020). Thus, hope is internal energy forever growing and enabling one to break down walls and obstacles (Guedes et al., 2021). The experience of hope transmits peace and security to the present and, thus, gives strength to walk with confidence toward the future.

In this sense, a pedagogy of hope should be present in the loving, supportive, encouraging, and activating presence of those who work in palliative care. Every therapeutic intervention should be committed to hope, translated, and materialized in a personal attitude and ability to help others look at reality differently, with neither a facile optimism nor a destructive pessimism, but a realistic, active, questioning hope (Olsman, 2022).

Hope is a product of human action, but also an ontological necessity (Torres-Olave, 2021). That is why, in desperate situations (e.g., spiritual anguish), hope appears as the only source of salvation, leading people to look ahead and search for new ways to solve difficulties, especially when the remedy is complicated or cannot be found in science, technology, and social development. This is the case of terminal illnesses that are both desperate and intrusive. When faced with such situations, many people give in to despair and disillusionment, as evidenced by the increase in suicidality (Salamanca-Balen et al., 2021), and experience anxiety and depression (Lee et al., 2022), while others continue to nourish the hope that better days will come, even invoking divine protection, thus, envisioning improvements in health or family life.

Why We Wait: Fostering Hope in Palliative Care

Curiously, in the face of adverse socio-economic and cultural circumstances (which mainly victimize the most vulnerable), hope appears as the main and last stronghold a person can cling to, even if resigned to their fate (Javier-Aliaga et al., 2022). The same is true of victims of incurable diseases or other situations, for which all human, scientific, and technological capacities seem exhausted, but who nevertheless claim to have an unshakable faith and hope. Several studies support the existence of spiritual distress in patients who are seriously ill that require coping strategies (e.g., hope) to overcome suffering (Kondejewski and Sinclair, 2018; Martins and Caldeira, 2018). Why do these people continue to wait, despite all their setbacks?

Hope is present in every part of our lives, as a search for the meaning of life, particularly in times of suffering. Viktor Frankl's book Man's Search for Meaning drew attention to what he called “the existential vacuum” and how human beings are unable to develop in an unfavorable environment, without meaning, order, trust, and stability (Schimmoeller and Rothhaar, 2021). Meaning is an essential element of a human being throughout the construction of their life (Feldman et al., 2018). We are beings devoted to the search for meaning. Biologically, our nervous system is structured such that external stimuli are automatically organized by the brain into internally meaningful structures (Genon et al., 2018). Psychologically, hope is a response of trust, which, at the same time, allows us to find the meaning of difficulties and trials in life, including the most serious. However, some situations exceed our abilities and control, when the presence of meaning in life is beyond our control. This is when hope comes into play when it guarantees the presence of meaning in life and promotes life satisfaction (Karata et al., 2021).

Given the positive effects of hope in palliative care, various psychospiritual and clinical strategies to foster hope or diminish hopelessness have been documented in the palliative care literature (Laranjeira et al., 2020). Herth (2000), for example, designed a nursing intervention program to enhance hope and quality of life in a group of cancer patients. Duggleby and Williams (2010) developed a group intervention program designed to help palliative caregivers endure suffering by living with hope. Similarly, dignity therapy (a brief psychological intervention based on scientific understandings of dignity toward the end-of-life) has been tried in a diverse group of patients in palliative care (Salamanca-Balen et al., 2021). Some strategies have been intended primarily to improve other outcomes, with hope or hopelessness measured as a secondary outcome. Meaning-centered psychotherapy studies, for example, often assess spiritual well-being and quality of life as key outcomes and hopelessness as a secondary outcome (Breitbart et al., 2012).

A recent meta-analysis found that hope-fostering interventions improved spirituality and lowered depression considerably (Salamanca-Balen et al., 2021). Hope and spirituality may be connected, which would explain why these interventions affect both outcomes. Moreover, there is evidence that multi-component interventions (such as early palliative care, which incorporates particular medical, social, and psychological components) can be beneficial in enhancing the quality of life, lowering depression, and increasing survival (Temel et al., 2010). Thus, hope is not just a virtue, a source of energy that allows us to face and overcome barriers and difficulties, but also a fundamental dynamic of living, enabling one to face life with a different perspective and renewed meaning, even when none seems to exist (Colla et al., 2022). While a lack of judgment or critical thinking about one's spiritual beliefs can result in a narrow and selfish worldview that becomes dogmatic and rigid, too much hope may cause a person to only see the positive aspects of their spirituality and ignore the negative aspects or limitations (Niemiec et al., 2020). The simplistic concept of “good” spirituality may lead researchers to overlook the potentially damaging aspects of spiritual life. There are many examples of those seeking intimacy with God via generosity and compassion, who also employ intense self-punishing asceticism to attain their sacred aspirations. By definition, ignoring the dark side of spirituality results in an incomplete or inaccurate depiction of the phenomena (Paloutzian and Park, 2013).

Religious and spiritual struggles may compromise the well-being and positive mental states and be related to anxiety or depression in those receiving palliative care (Damen et al., 2021). The most common spiritual struggles in end-of-life care include the following: “anger or disappointment with God, feeling abandoned, or unloved by God; tensions and guilt about not living up to one’s higher standards and wrestling with attempts to follow moral principles; and concerns that life may not matter, and questions about whether one’s own life has a deeper meaning” (Pargament and Exline, 2020, p.1). To properly apply spiritual care in palliative care at this stage, healthcare providers must build their spiritual competency via education and self-reflection (Gijsberts et al., 2019).

Continuing Education Program For Healthcare Providers in Palliative Care: Some Recommendations

As mentioned, understanding personhood cannot dispense with analyzing the conditions that make being a person possible. Personhood is inseparable from living with dignity and, consequently, from the common good that makes it possible. Hence, the mandatory inclusion of the approach of spirituality and hope when training professionals who face end-of-life situations is part of a more humanized and patient-centered model of care (García-Navarro et al., 2021). Regrettably, these professions are not sufficiently trained and prepared to deal with spirituality and interventions related to finitude (Wu et al., 2016; Oliveira et al., 2021).

As part of an international consortium between higher education institutions in Portugal (Polytechnic of Leiria) and Universities of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland-HES-SO (Lausanne and Geneva), a continuing education program on spirituality was designed for palliative care professionals. This proposal aims to promote the experience of hope in palliative care, thus, making it possible to: understand that hope is a humanizing virtue that generates dignity, love, and meaning in life and to understand hope as a force and dynamism that spurs an active commitment to the other and compassion in care.

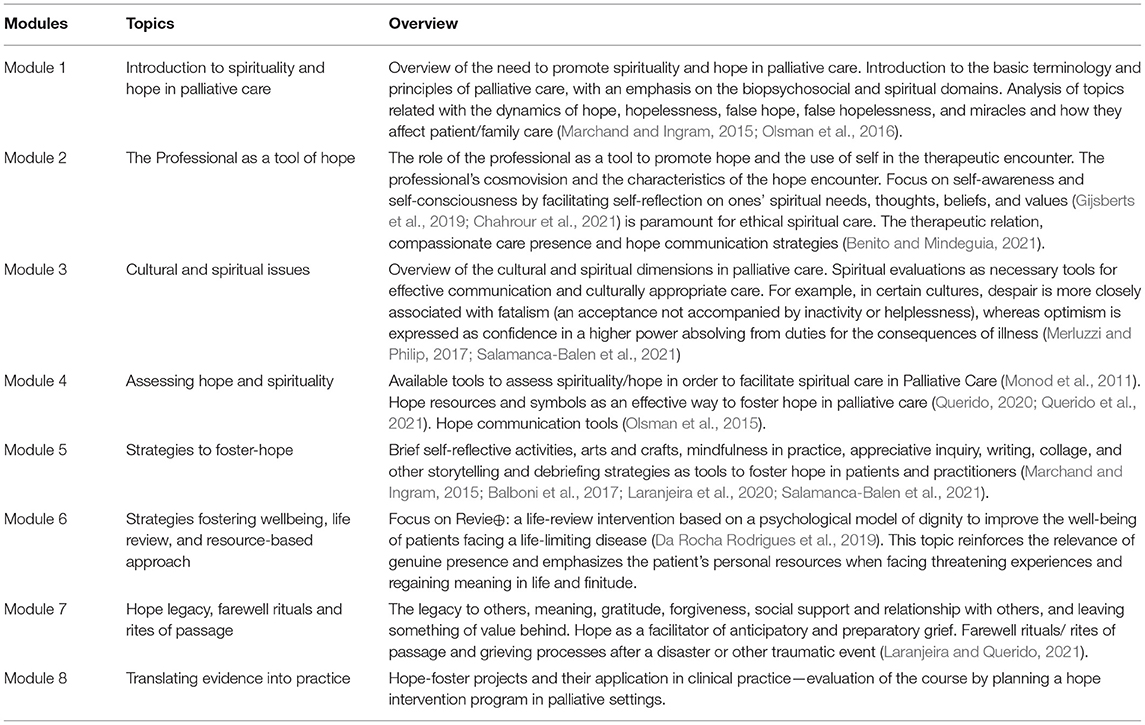

Therefore, this type of continuous training (Table 1) will provide professionals with a coherent and authentic vision of hope in contexts where death and dying happen persistently. Only in this way will they understand hope as something to be hoped for and believed in, but also as a virtue and a force that motivates and demands an active commitment to the other and compassion for the situation in which they find themselves.

Final Remarks

Advocating for hope and spirituality in palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic is critical because they help patients bring purpose to their lives. We should not remain inert in the face of difficulties, but should rather maintain hope and know-how to transform problems into experiences that promote our growth and learning. Spirituality and hope facilitate each other and together contribute to greater human wholeness by giving meaning and adjustment to negative life experiences.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work is funded by national funds through FCT–Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I. P. (UIDB/05704/2020 and UIDP/05704/2020) and under the Scientific Employment Stimulus—Institutional Call—(CEECINST/00051/2018).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Balboni, T., Fitchett, G., Handzo, G., Johnson, K. S., Koenig, H., Pargament, K., et al. (2017). State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research part ii: screening, assessment, and interventions. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 54, 441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.029

Benito, E., and Mindeguia, M. (2021). La presencia: el poder terapéutico de habitar el presente en la práctica clínica. Psicooncología 18, 371–385. doi: 10.5209/psic.77759

Breitbart, W., Poppito, S., Rosenfeld, B., Vickers, A., Li, Y., Abbey, J., et al. (2012). Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 1304–1309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2517

Bunkers, S. S.. (2020). Moments of fragility and vitality. Nurs. Sci. Q. 33, 286–292. doi: 10.1177/0894318420943152

Büssing, A., Rodrigues Recchia, D., Dienberg, T., Surzykiewicz, J., and Baumann, K. (2021). Awe/gratitude as an experiential aspect of spirituality and its association to perceived positive changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 12, 642716. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.642716

Chahrour, W., Hvidt, N., Hvidt, E., and Viftrup, D. (2021). Learning to care for the spirit of dying patients: the impact of spiritual care training in a hospice-setting. BMC Palliat. Care 20, 115. doi: 10.1186/s12904-021-00804-4

Colla, R., Williams, P., Oades, L. G., and Camacho-Morles, J. (2022). “A New Hope” for positive psychology: a dynamic systems reconceptualization of hope theory. Front. Psychol. 13, 809053. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809053

Counted, V., Pargament, K. I., Bechara, A. O., Joynt, S., and Cowden, R. G. (2022). Hope and well-being in vulnerable contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic: does religious coping matter? J. Positive Psychol. 17, 70–81. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1832247

Da Rocha Rodrigues, M. G., Pautex, S., and Zumstein-Shaha, M. (2019). Revie ⊕: an intervention promoting dignity in people with advanced cancer: a feasibility study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 39, 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.01.006

Damen, A., Exline, J., Pargament, K., Yao, Y., Chochinov, H., Emanuel, L., et al. (2021). Prevalence, predictors and correlates of religious and spiritual struggles in palliative cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 62, e139–e147. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.04.024

Duggleby, W. D., and Williams, A. M. (2010). Living with hope: developing a psychosocial supportive program for rural women caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. BMC Palliat. Care 9, 3. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-9-3

Feldman, D., Balaraman, M., and Anderson, C. (2018). “Hope and Meaning-in-Life: points of contact between hope theory and existentialism,” in The Oxford Handbook of Hope, eds W. G. Matthew and J. L. Shane (New York, NY: Oxford University Press).

García-Navarro, E. B., Medina-Ortega, A., and García Navarro, S. (2021). Spirituality in patients at the end of life—is it necessary? A qualitative approach to the protagonists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 227. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010227

Genon, S., Reid, A., Langner, R., Amunts, K., and Eickhoff, S. B. (2018). How to characterize the function of a brain region. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 350–364. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.010

Gijsberts, M., Liefbroer, A., Otten, R., and Olsman, E. (2019). Spiritual care in palliative care: a systematic review of the recent european literature. Med. Sci. (Basel) 7, 25. doi: 10.3390/medsci7020025

Guedes, A., Carvalho, M., Laranjeira, C., Querido, A., and Charepe, Z. (2021). Hope in palliative care nursing: concept analysis. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 27, 176–187. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2021.27.4.176

Hamouche, S.. (2020). COVID-19 and employees' mental health: stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Res. 2, 15. doi: 10.35241/emeraldopenres.13550.1

Herth, K.. (2000). Enhancing hope in people with a first recurrence of cancer. J. Adv. Nurs. 32:1431–1441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01619.x

Jaiswal, R., Alici, Y., and Breitbart, W. (2014). A comprehensive review of palliative care in patients with cancer. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 26, 87–101. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.868788

Javier-Aliaga, D. J., Quispe, G., Quinteros-Zuñiga, D., Adriano-Rengifo, C. E., and White, M. (2022). Hope and resilience related to fear of COVID-19 in young people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 5004. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095004

Karata,ş, Z., Uzun, K., and Tagay, Ö. (2021). Relationships between the life satisfaction, meaning in life, hope and COVID-19 fear for Turkish adults during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychology 12, 633384. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633384

Kondejewski, J., and Sinclair, S. (2018). Spiritual distress within inpatient settings-a scoping review of patients' and families' experiences. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 56, 122–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.03.009

Kor, A., Pirutinsky, S., Mikulincer, M., Shoshani, A., and Miller, L. (2019). A longitudinal study of spirituality, character strengths, subjective well-being, and prosociality in middle school adolescents. Front. Psychol. 10, 377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00377

Laranjeira, C., and Querido, A. (2021). Changing rituals and practices surrounding COVID-19 related deaths: Implications for mental health nursing. Br. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 10, 1–5. doi: 10.12968/bjmh.2021.0004

Laranjeira, C., Querido, A., Charepe, Z., and Dixe, M. (2020). Hope-based interventions in chronic disease: an integrative review in the light of Nightingale. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 73, e20200283. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0283

Lee, W., Chang, S., DiGiacomo, M., Draper, B., Agar, M., and Currow, D. (2022). Caring for depression in the dying is complex and challenging - survey of palliative physicians. BMC Palliat. Care 21, 11. doi: 10.1186/s12904-022-00901-y

Leget, C.. (2018). “Spirituality in palliative care,” in Textbook of Palliative Care, eds R. D. MacLeod and L. Van den Block (Cham: Springer International Publishing).

Long, E., Patterson, S., Maxwell, K., Blake, C., Bosó Pérez, R., Lewis, R., et al. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social relationships and health. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 76, 128–132. doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-216690

Lozupone, M., La Montagna, M., Di Gioia, I., Sardone, R., Resta, E., Daniele, A., et al. (2020). Social frailty in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Front. Psychiatry 11, 577113. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577113

Marchand, L., and Ingram, C. (2015). The healing power of hope: for patients and palliative care clinicians (SA518). J. Pain Symptom Manag. 49, 396. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.161

Martins, H., and Caldeira, S. (2018). Spiritual distress in cancer patients: a synthesis of qualitative studies. Religions 9, 285. doi: 10.3390/rel9100285

Mayseless, O., and Russo-Netzer, P. (2017). A vision for the farther reaches of spirituality: a phenomenologically based model of spiritual development and growth. Spirit. Clin. Practice 4, 176–192. doi: 10.1037/scp0000147

Merluzzi, T., and Philip, E. (2017). “Letting go”: from ancient to modern perspectives on relinquishing personal control-a theoretical perspective on religion and coping with cancer. J. Relig. Health 56, 2039–2052. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0366-4

Monod, S., Brennan, M., Rochat, E., Martin, E., Rochat, S., and Büla, C. J. (2011). Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 1345–1357. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1769-7

Niemiec, R. M., Russo-Netzer, P., and Pargament, K. I. (2020). The decoding of the human spirit: a synergy of spirituality and character strengths toward wholeness. Front. Psychol. 11, 2040. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02040

Oliveira, L., Oliveira, A., and Ferreira, M. (2021). Nurses' training and teaching-learning strategies on the theme of spirituality. Escola Anna Nery 25, e20210062. doi: 10.1590/2177-9465-ean-2021-0062

Olsman, E.. (2022). Witnesses of hope in times of despair: chaplains in palliative care. A qualitative study. J. Health Care Chaplain. 28, 29–40. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2020.1727602

Olsman, E., Leget, C., and Willems, D. (2015). Palliative care professionals' evaluations of the feasibility of a hope communication tool: a pilot study. Prog. Palliat. Care 23, 321–325, doi: 10.1179/1743291X15Y.0000000003

Olsman, E., Willems, D., and Leget, C. (2016). Solicitude: balancing compassion and empowerment in a relational ethics of hope-an empirical-ethical study in palliative care. Med. Health Care Philos. 19, 11–20. doi: 10.1007/s11019-015-9642-9

Paloutzian, R. F., and Park, C. L. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Pargament, K. I., and Exline, J. J. (2020). Religious and Spiritual Struggles. Available Online at: https://www.apa.org/topics/belief-systems-religion/spiritual-struggles (accessed May 20, 2022).

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. New York, NY; Washington, DC: Oxford University Press; American Psychological Association.

Pinsent, A.. (2020). “Hope as a virtue in the middle ages,” in Historical and Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Hope, ed S. C. van den Heuvel (Cham: Springer).

Querido, A.. (2020). “A promoção da esperança em saúde mental,” in Enfermagem em Saúde Mental: Diagnósticos e Intervenções, eds C. Sequeira and F. Sampaio (Lisboa: Lidel), 243–246.

Querido, A., Laranjeira, C., Dixe, M., Figueiredo, M., Marques, R., and Charepe, Z. (2021). “A Promoção da Esperança nas Transições de Saúde-Doença: Contributos para a Ação [Promoting Hope in Health-Disease Transitions: Contributions to Action],” in O Cuidado Centrado no Cliente, da Apreciação à Intervenção de Enfermagem, Coord Eunice Henriques (Lisboa: Sabooks-Lusodidacta), 187–202.

Rego, F., and Nunes, R. (2019). The interface between psychology and spirituality in palliative care. J. Health Psychol. 24, 279–287. doi: 10.1177/1359105316664138

Roman, N. V., Mthembu, T. G., and Hoosen, M. (2020). Spiritual care - 'A deeper immunity' - A response to Covid-19 pandemic. Afr. J. Primary Health Care Family Med. 12, e1–e3. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2456

Salamanca-Balen, N., Merluzzi, T. V., and Chen, M. (2021). The effectiveness of hope-fostering interventions in palliative care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat. Med. 35, 710–728. doi: 10.1177/0269216321994728

Schimmoeller, E. M., and Rothhaar, T. W. (2021). Searching for meaning with victor frankl and walker percy. Linacre Q. 88, 94–104. doi: 10.1177/0024363920948316

Steinhauser, K., Fitchett, G., Handzo, G., Johnson, K., Koenig, H., Pargament, K., et al. (2017). State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research part i: definitions, measurement, and outcomes. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 54, 428–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.028

Stilos, K. K., Ford, R. B., and Wynnychuk, L. (2021). Call to action: the need to expand spiritual care supports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 31, 347–349.

Temel, J., Greer, J., Muzikansky, A., Gallagher, E., Admane, S., Jackson, V., et al. (2010). Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

Torres-Olave, B.. (2021). Pedagogy of hope: reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Educ. Rev. 73, 1,128. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2020.1766207

Worth, P., and Smith, M. D. (2021). Clearing the pathways to self-transcendence. Front. Psychol. 12, 648381. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648381

Keywords: hope, spirituality, positive psychology, palliative care, healthcare professionals, COVID-19 pandemic, continuing education

Citation: Laranjeira C, Baptista Peixoto Befecadu F, Da Rocha Rodrigues MG, Larkin P, Pautex S, Dixe MA and Querido A (2022) Exercising Hope in Palliative Care Is Celebrating Spirituality: Lessons and Challenges in Times of Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 13:933767. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.933767

Received: 01 May 2022; Accepted: 30 May 2022;

Published: 29 June 2022.

Edited by:

Llewellyn Ellardus Van Zyl, North West University, South AfricaReviewed by:

Andrzej Jastrzebski, University of Ottawa, CanadaCopyright © 2022 Laranjeira, Baptista Peixoto Befecadu, Da Rocha Rodrigues, Larkin, Pautex, Dixe and Querido. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlos Laranjeira, Y2FybG9zLmxhcmFuamVpcmFAaXBsZWlyaWEucHQ=; Ana Querido, YW5hLnF1ZXJpZG9AaXBsZWlyaWEucHQ=

Carlos Laranjeira

Carlos Laranjeira Filipa Baptista Peixoto Befecadu4

Filipa Baptista Peixoto Befecadu4 Maria Goreti Da Rocha Rodrigues

Maria Goreti Da Rocha Rodrigues Philip Larkin

Philip Larkin Maria Anjos Dixe

Maria Anjos Dixe Ana Querido

Ana Querido