95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 06 September 2022

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.920274

Lulin Zhou1†

Lulin Zhou1† Arielle Doris Tetgoum Kachie1*†

Arielle Doris Tetgoum Kachie1*† Xinglong Xu2

Xinglong Xu2 Prince Ewudzie Quansah2

Prince Ewudzie Quansah2 Thomas Martial Epalle3

Thomas Martial Epalle3 Sabina Ampon-Wireko2

Sabina Ampon-Wireko2 Edmund Nana Kwame Nkrumah4

Edmund Nana Kwame Nkrumah4Nurses’ turnover intention has become a concern for medical institutions because nurses are more needed than ever under the prevalence of COVID-19. This research sought to investigate the effects of the four dimensions of organizational justice on COVID-19 frontline nurses’ turnover intention through the mediating role of job engagement. We also tested the extent to which perceived job alternatives could moderate the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention. This descriptive cross-sectional study used an online survey to collect data from 650 frontline nurses working in appointed hospitals in Jiangsu province, China. Hierarchical regression was used to analyze the hypothesized relationships. Findings revealed that all organizational justice components significantly influenced job engagement and turnover intention. Job engagement also significantly affected nurses’ turnover intention and mediated the relationships between organizational justice components and turnover intention. Besides, perceived job alternatives moderated the relationships between job engagement and turnover intention. The implications of this study include demonstrating that healthcare authorities should respect human rights through effective organizational justice as this approach could encourage nurses to appreciate their job and be more devoted to staying and achieving their institutional duties, especially under challenging circumstances.

Nurses’ role in any community is vital, as they work 24/7 to provide patients with quality care services. Since the end of 2019, when the COVID-19 pandemic tragically attacked the world, frontline nurses have shown bravery and courage to save people’s lives. COVID-19 has been a shock for the world and its population, and the challenges to global health are still evident (World Health Organization, 2021). Nursing personnel was no less involved in China, where the pandemic erupted. Experienced, newly licensed, and even volunteer student nurses had to put efforts together considering the emergency of the situation (Zhang W. et al., 2020; Zhang Y. et al., 2020). Older nurses had to put their experience and courage forward. Also, newly registered nurses had to be more determined than ever to embrace their new work environment despite the pandemic. Volunteer student nurses had to acknowledge the challenges the work environment could bring into their lives. The conditions were such that frontline nurses had to simultaneously protect their lives and be on duty (Cai et al., 2020; Thorne, 2020).

According to Zhou et al. (2021) and Obeng et al. (2021), one can easily feel demotivated to continue working under conditions that threaten their existence. Recent research showed that COVID-19 increased turnover intention among healthcare personnel. Typical examples happened in the Philippines (Labrague and de Los Santos, 2020), Peru (Yáñez et al., 2020), Pakistan (Irshad et al., 2021), and China as well (Mo et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2020; Zhang W. et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2021).

Regardless of its old age and the significant number of academic research papers dealing with the topic, turnover intention remains a dynamic field of research, especially with the advancement of new managerial techniques for workers’ retention, labor market dynamism, the development of technology, new research methods, and constant environmental changes. In many cases, turnover intention happens when people’s job gives them more dissatisfaction, anxiety, and fear than happiness (Jung et al., 2021). According to Chen et al. (2022), organizational justice is one possible factor that tends to create satisfaction or dissatisfaction, serenity or anxiety, happiness or melancholy, and courage or fear in many organizations, including the healthcare sector. It has also been linked to turnover in previous studies (Suifan et al., 2017; Hussain and Khan, 2019; Cao et al., 2020; Mengstie, 2020).

Colquitt et al. (2005) defined organizational justice as how workers feel about their company’s impartiality or fairness. It has four dimensions: distributive justice, procedural justice, interpersonal justice, and information justice (Nojani et al., 2012; Colquitt et al., 2013; Mengstie, 2020). Studies (e.g., Cao et al., 2020 and Mengstie, 2020) that examined the relationship between organizational justice and turnover intention analyzed these four dimensions as a composite score of organization justice, making it unclear whether each dimension’s predictive effects on turnover intention differ. The current study will address this literature gap by examining the predictive capacity of the four dimensions of organizational justice on turnover intention among frontline nurses, especially in COVID-19. Frontline nurses constitute an appropriate sample to explore how the different aspects of organizational justice influence their turnover intention in such a demanding environment. Such a study might be relevant to reducing nurses’ turnover intention and, thus, their actual turnover. However, it may be complete if we know how (the influencing mechanism through which) these organizational justice components could directly or indirectly influence turnover intentions. Job engagement has been proposed in previous studies (e.g., Park and Johnson, 2019; Cao et al., 2020; Jung et al., 2021; and Chen et al., 2022) to mediate the relationship between turnover intention and its antecedent significantly.

Job engagement refers to a positive, meaningful, and enthusiastic attitude employees show to their organization when they like their job (Schaufeli et al., 2006). It can demotivate employees from leaving their current jobs (Moo and Sung, 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). Thus, organizations that create a climate that increases job engagement are likely to benefit from lower turnover than organizations that do not (Jung et al., 2021). Therefore, analyzing job engagement as a mediator between the nurses’ perception of justice and turnover intention will contribute to the literature. Despite the mediating capacity of job engagement on turnover intention and other antecedents, it is relevant to examine the conditions under which the impact of job engagement on turnover intention could either be strengthened or weakened. Alternative job opportunities (Dohlman et al., 2019) may be possible to provide conditions that can buffer the impact of work engagement on turnover intention.

Perceived job alternative refers to workers’ interest in the external labor market and their awareness of other available jobs (Sender et al., 2021). It can affect employees’ engagement as it increases one’s enthusiasm for their job (Dohlman et al., 2019). The assurance of getting a new job may also involve the cognitive aspect of staying or not in that job (Hom et al., 2012). Though precedent research demonstrated how the perception of alternative job opportunities might influence employees’ job attitudes and their movement desirability (Li et al., 2016), they failed to investigate whether it moderates the relationship between workers’ engagement and turnover intention. Thus, exploring such intervention is indispensable.

Also, several studies have proposed various theories to explain the relationships between turnover intention and its antecedents. There is the equity theory (Cao et al., 2020), the job demands-resources model (Carlson et al., 2017; Scanlan and Still, 2019), the conservation of resources theory (Jin et al., 2016), and the effort-reward-imbalance model (Derycke et al., 2011; Zeng et al., 2021) among others. This study employs social exchange theory (SET; Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005) to espouse the linkages between organizational justice, job engagement, alternative job opportunities, and turnover intention.

The social exchange theory’s core theoretical and empirical aspects rest on reciprocity, social networks, fairness, solidarity, and social cohesion (Cook, 2015). The theory supposes that people’s social behaviors result from evaluating the benefits and costs during an exchange process. Individuals perform a behavior when they are assured that the resulting reward will at least be equal to or exceed the costs. Conversely, individuals will restrain from performing a behavior when inputs are more than outcomes and could even start looking at other options (Bies and Moag, 1986; Colquitt, 2001). From this viewpoint, medical industries’ exemplary implementation of organizational justice may enhance workers’ resources such as engagement, lower negative job attitudes such as turnover intention, and eradicate alternative job search behavior.

Thus, this study assumes that the pandemic aggressivity could affect nurses’ perception of justice in their workplace, influencing their engagement and willingness to continue in that profession or pushing them to find alternative jobs. Otherwise, despite the difficulties, they could also, with the appropriate resources, find themselves valuable enough for the current time and get more engaged to help the world go back to a healthier place (Thorne, 2020; Zhang Y. et al., 2020). Following this trend, this study aimed to explore organizational justice’s impact on turnover intention through job engagement among frontline nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, the moderating role of perceived job alternatives on job engagement and turnover intention relationship will be ascertained. The study also presents a conceptual framework (Figure 1) that espouses the linkages among the various variables under investigation.

Turnover intention has been defined as an employee’s perception of the likelihood of leaving their current job or forfeiting their present position in an organization (Meyer et al., 1993; Tao et al., 2018). As a precursor of actual turnover (which is among the leading cause of the nursing shortage), the turnover intention has been addressed widely in the nursing literature in other parts of the world (Al Sabei et al., 2020; Bautista et al., 2020), as in China (Wang and Wang, 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). Damages to the medical organizations and employees’ lives make it continue to be a subject of growing interest, especially after the World Health Organization projection of about 12.9 million nurses shortage in the world by the end of 2035 (Marć et al., 2019). With the current COVID-19 pandemic, this projection could be more significant.

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned the world upside down, and frontline nurses’ lives have been impacted in many ways. Caring for COVID-19 patients has affected their mental health, wellbeing, and family life (Mo et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). They had to deal with and quickly adapt to constantly changing protocols and policies and a patient load augmentation (Labrague and de Los Santos, 2020). Additionally, they have been exposed to discrimination and isolation (Al Sabei et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2020). With the experience of the previous sanitary crisis (SARS or Serious Acute Respiratory Syndrome) the country went through in 2002/2003, Chinese nurses knew how someone’s life could be affected (Catton, 2020). Evidence supports that the unexpected changing conditions made nurses more vulnerable and susceptible to quitting; they were highly concerned about their personal and family welfare since they had to balance facing a deadly virus and their ethical duty (Maben and Bridges, 2020). As He et al. (2020) reported, the prevalence of turnover intention before COVID-19 was already high at 30.4% among Chinese health personnel. It increased by 10.1% during COVID-19 (Hou et al., 2021). Though a plethora of research has assessed the factors influencing nursing turnover intention, it is still essential to consider the combination of other fundamentals affecting it since attitudes are contextual and are subject to change, and their understanding seems complex.

The concept of organizational justice has been increasingly given a universal concern based on its little emphasis on human rights (Topbaş et al., 2019). It has gained more consideration in the Western culture throughout the years; however, the non-Western world still needs more evidence on how its workers perceive it (Fodchuk, 2009; Cao et al., 2020). It is important to note that the perception of human rights has evolved with time and is also influenced by the differences in cultural backgrounds and levels of development (Kausikan, 1996). For example, taking someone’s right to life (committing murder) is a gross violation of human rights and should be sentenced accordingly in any civilized world. Still, in many aspects of human rights, the East, compared to the West, considers human rights as a process rather than specific outcomes (Seokwoo and Hee, 2020). The Eastern human rights idea results from historical developments which vary with liberal frameworks and democratic institutions. Their practice of human rights differs from the country and is integrated into people’s everyday life. It is closely related to religious beliefs, historical background, social conditions and values (Prakash and Murarka, 2021).

Organizational justice is perceived differently across cultures as a psychological construct since it expresses workers’ judgment of fairness or righteousness in their organizations (Quezada-Abad et al., 2019). Then, it can significantly influence organizational behaviors and outcomes (Colquitt, 2001). Evidence supports that perceived justice is positively associated with organizational behaviors such as job engagement (Cao et al., 2020; Suifan et al., 2020), trust (Bidarian and Jafari, 2012; AL-Abrrow et al., 2013), organizational citizenship behaviors (Chang, 2014; Sulander et al., 2016), organizational commitment (Ohana, 2014; Fardid et al., 2018), job satisfaction (Cassar and Buttigieg, 2015; Fardid et al., 2018), and negatively with turnover intention and other negative attitudes (Colquitt et al., 2013; Proost et al., 2015; Terzioglu et al., 2016) across various settings. Employees’ perception of injustice can predispose them to experience burnout; contrariwise, their engagement is enhanced when they think they are treated fairly by their institution. They want to stay and give the best of themselves (Maslach et al., 2001).

According to Colquitt (2001) and Colquitt et al. (2013), organizational justice is a multifaceted concept that includes four dimensions, distributive justice, procedural justice, interpersonal justice, and informational justice. Distributive justice has to do with fairness in outcomes’ distribution, like salary, promotion, or rewards. Workers try to evaluate the balance between their outputs and inputs. Here, employees’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral reactions are related to their judgment of how outcomes are distributed (Cropanzano et al., 2007). Procedural justice refers to ethics’ consistency, accuracy, and respect during decision-making and outcomes distribution (Leventhal, 1980; Quezada-Abad et al., 2019). It influences employees’ consideration for their organization and attitudes to stick with the company’s best interests. Interpersonal justice expresses how the authority enacts procedures or distributes outcomes with respect and dignity. When their organization appropriately treats workers, it enhances other good behaviors and willingness to comply with decisions (Bies and Moag, 1986; Colquitt, 2001). Informational justice deals with truth and adequacy in sharing information or implementing procedures. In providing information, the clarifications and justifications help elucidate any feeling of injustice and prevent adverse reactions among the personnel (Colquitt et al., 2013).

Drawing on the social exchange theory (SET; Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005), organizations that can fulfill the various elements of organizational justice such that employees can perceive their dispensation as fair or equitable can persuade employees to reciprocate through devotion. Highly devoted employees show higher enthusiasm for work engagement than less devoted employees (Suifan et al., 2020). Therefore, we rely on SET and other related studies (e.g., Colquitt et al., 2013; Chen and Jin, 2014; Cao et al., 2020; and Chen et al., 2022) to propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Organizational justice will have a significant negative influence on turnover intention.

H1a: Distributive justice will have a significant negative influence on turnover intention.

H1b: Procedural justice will have a significant negative influence on turnover intention.

H1c: Interpersonal justice will have a significant negative influence on turnover intention.

H1d: Informational justice will have a significant negative influence on turnover intention.

H2: Organizational justice will significantly and positively affect nurses’ job engagement.

H2a: Distributive justice will significantly and positively affect nurses’ job engagement.

H2b: Procedural justice will significantly and positively affect nurses’ job engagement.

H2c: Interpersonal justice will significantly and positively affect nurses’ job engagement.

H2d: Informational justice will significantly and positively affect nurses’ job engagement.

When employees like their job, one of the positive, enthusiastic responses they give to their organization is engagement (Ghosh et al., 2014). Therefore, it is a vital factor an organization can rely on to boost its productivity and profit and reduce employee turnover (Bin, 2016). According to Schaufeli et al. (2006), job engagement encapsulates vigor, absorption, and dedication, implying that people use their energy to immerse in and fulfill their life-driven purpose, which is their job. It has been related to many antecedents and consequences (Al-Tit and Hunitie, 2015). Positive outcomes related to workers’ engagement include satisfaction (Bin, 2016; Pieters, 2018), commitment (Al-Tit and Hunitie, 2015), good performance (Bin, 2016; Terzioglu et al., 2016), low intent to quit, and other positive behaviors (Bakker et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2019). From the lenses of the job demands-resources (JD-R) model, the firm’s physical, social and psychological aspects are required resources that can empower workers’ intellectual and emotional association with it and lower their withdrawal behaviors (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007). Also, drawing on social exchange theory (SET; Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005), employees feel more connected to their company, work hard, and encourage colleagues to do the same when higher engagement occurs. SET theorists (e.g., Agarwal, 2014; Ancarani et al., 2018; and Yin, 2018) highlight that promoting job engagement creates a validation environment for employees to function. Employees who feel validated show great enthusiasm, stay longer, and work for their organizations through reciprocity (Juhdi et al., 2013). Several other studies (e.g., Edwards-Dandridge, 2019; Cao et al., 2020; and Zhang X. et al., 2020) also found work engagement to mitigate one’s desire to leave their work voluntarily. Therefore, from the perspective of social exchange theory and other related literature, the study hypothesizes that:

H3: Job engagement has a significant negative influence on frontline nurses’ turnover intention

Previous studies have demonstrated the mediating capacity of job engagement between its causing variables and those it impacts in various settings. For instance, job engagement has been shown to mediate significantly, among others, the relationships between organizational justice and job performance among airline employees in Jordan (Suifan et al., 2020), between job and personal resources, and turnover intention among female nurses in Iran (Shahpouri et al., 2016), between organizational support and intention to leave among healthcare employees in Turkey (Baş and Çınar, 2021), between job insecurity and safety behavior among enterprises employees (Zhang et al., 2021), or between job characteristics and job satisfaction among public banks workers in India (Rai and Maheshwari, 2021). From the literature review, organizational justice can influence job engagement (Zhu et al., 2015; Park et al., 2016; Özer et al., 2017) and turnover intention (Agbaeze et al., 2018; Perreira et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019). Also, studies like Park and Johnson (2019), Edwards-Dandridge et al. (2020), and Quek et al. (2021) have demonstrated that job engagement significantly influences turnover intention. Therefore, drawing on social exchange theory (SET), we believe that employees who fit in their work due to acceptable organization justice may be better engaged and show lower motivation to leave. For instance, the healthcare sector consists of inter-related activities and resources, including compensation, promotions, disciplinary procedures, performance appraisal, training, holidays, leave with pay, etc. From SET perspectives (Williamson and Williams, 2011), nurses who perceive inequality in distributing these resources may feel injustice. They may exhibit their displeasure in the form of lower job engagement (Chênevert et al., 2013). In contrast, nurses may feel justice or fairly treated if they perceive the equitable distribution of organizational resources. They may be motivated and inspired by the actions of their organization. Such nurses may reciprocate their organizations’ kind gestures through higher job engagement (Yin, 2018), which may reduce turnover intention (Memon et al., 2014; Edwards-Dandridge, 2019). From this background, it is expected that organizational justice increases work engagement and work engagement may reduce turnover intentions. Therefore, relying on the social exchange theory, we hypothesized that:

H4: Job engagement will significantly mediate the relationship between organizational justice and frontline nurses’ turnover intention.

H4a: Job engagement will significantly mediate the relationship between distributive justice and frontline nurses’ turnover intention.

H4b: Job engagement will significantly mediate the relationship between procedural justice and frontline nurses’ turnover intention.

H4c: Job engagement will significantly mediate the relationship between interpersonal justice and frontline nurses’ turnover intention.

H4d: Job engagement will significantly mediate the relationship between informational justice and frontline nurses’ turnover intention.

As human beings, workers always strive to look at what is best for themselves (Tay and Diener, 2011; Taormina and Gao, 2013). Their perception of their profitability and the availability of opportunities in the labor market influence their working behaviors and attitudes (Dohlman et al., 2019). Employees’ turnover intentions have been associated with alternative job opportunities. It is stated that turnover cognitions are prompted in employees who show low job attitudes or have job search behavior (Hom et al., 2012). For example, Sender et al. (2021) highlighted that workers with high turnover intentions had many job opportunities and presented severe deviant behaviors. The turnover intention was similarly predicted by perceived job alternatives in a study by Wossen and Alemu (2018), where personnel with a higher turnover intention had an increased perception of job availability outside the company.

Prior research has also established how perceived job alternatives can moderate and alter a bivariate causal relationship by strengthening or weakening it. Because of previous antecedents, withdrawal behaviors from workers may be observed depending on their perceived level of alternative jobs. In a study by Robert and Vandenberghe (2017), alternative job opportunities moderated the relationship between openness to experience and intention to quit. Another study by Van Hootegem et al. (2019) similarly observed that perceived job opportunities played a moderating role between job insecurity and the willingness to undertake training. Within a correlation framework as a third variable, perceived job alternative has been shown to affect the zero-order correlation between two other variables (Baron and Kenny, 1986).

Workers with a high perception of alternative job opportunities show less positive job attitudes such as job satisfaction, commitment, or job engagement and are most likely to leave (Li et al., 2016; Dohlman et al., 2019). Furthermore, these positive job attitudes negatively influence turnover intention, making perceived job alternatives satisfy the moderation criterion. The social exchange theory also explains that the relationship evolves with time and reaches different stages during an exchange process. At the beginning of the relationship, individuals may ignore the social exchange balance but start contrasting the costs and benefits with time. If they estimate the results are not equitable, they may start evaluating the alternatives, which may eventually affect the nature of the relationship (Emerson, 1976; Lambe et al., 2001). From this premise and based on the fact that limited research has examined how perceived job alternatives could alter the direction between job engagement and turnover intention; we then suggest the following hypothesis:

H5: Perceived job alternatives will moderate the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention.

This research used a descriptive and cross-sectional study design based on STROBE guidelines, using an online questionnaire survey to collect data. Data were collected from frontline nurses working in tertiary hospitals across Jiangsu province in China. Third-level hospitals are big-sized hospitals with more than 500 beds and equipped with advanced technologies offering high-quality, specialized, and comprehensive medical care, with possibilities for medical education and research, and are found in large cities (Zhang et al., 2013; La Forgia and Yip, 2017).

A purposive and random sampling technique was used to select 14 tertiary hospitals among the 28 designated to treat pneumonia caused by the novel coronavirus in Jiangsu Province. For a better representation, one of the two hospitals was selected in each of the 13 prefecture-level cities of Jiangsu Province and the 14th among the two at the provincial level.

Registered nurses formally or contract employed, on duty during the survey, who have been working for at least 6 months in their actual work unit and who have been directly involved in taking care of patients with coronavirus were eligible to participate in this study. We adopted a sample-to-variable ratio for the sample size determination, presented as the N: p ratio, where N and p are the numbers of participants and items, respectively (Chatterjee and Hadi, 2015; Sprent and Smeeton, 2016). More specifically, a 10: 1 ratio was used (as proposed by Cattell (1978), and cited by Kline (2014)) to determine sample size, indicating that for the 31 items of the survey, a total number of 310 participants would be sufficient. The online survey was then conveniently sent to 650 frontline nurses (approximatively the double amount required to ensure greater participation), of which 576 submitted the questionnaire, making a response rate of 88.6%.

Data collection was done under the approval of various hospital authorities between September and October 2021, a few months after the outbreak in Nanjing city. An online data collection approach was adopted due to the pandemic’s restrictions. Hospitals’ administrators helped share the questionnaire link with nurses working in different hospitals through nurses’ supervisors. Nurses’ supervisors then forwarded the link to their networking groups to make it accessible, mainly through WeChat, a well-liked mobile application in China. The questionnaire included four standardized scales and socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, age, education level, marital status, employment status, salary, and years of experience. To manage common method biases and also deal with invalid responses appropriately, we designed the questionnaires in a way that could have the tenacity to prevent issues related to invalid responses. It was designed in a manner that made all the questions compulsory. Hence, failing to respond to one question would not allow one to submit the survey. Therefore all submitted online responses by the respondents were filled without errors. The respondents’ ability to fill the online surveys appropriately could emanate from the fact that nurses were informed in the introductory text that preceded the questionnaire that they should answer all the questions if they choose to participate. Also, prior to issuing the QR-Code and online link containing the online survey, the authors sought clearance from the authorities of these hospitals. We explained to them the objectives of the study. After receiving the approval, we held short meetings with the various frontline nurses’ supervisors, explained to them the aim of our research, and requested them to encourage nurses under their supervision to participate in the online survey issued to them by their administrators in the form of either QR-Code or an online link. We assured them of the utmost anonymity and privacy of their responses. We informed the respondents that their responses would only be used for academic exercise and that their identity would not be disclosed to anyone in any way or any form. We also requested them to fill out the online survey sent to them by their administrators with all honesty and sincerity. We reminded them that there was no wrong or correct answer and that they could choose the most appropriate response that addresses or fits their current situation. In all our meetings with the respondents, we highlighted that participation was voluntary. Moreover, those who choose to participate could decline anytime they deem necessary. Employing these approaches helped manage biases and invalid responses.

Since the available versions of the scales were in English (see Appendix A), their items were reverse translated into Chinese. Back-translation and standard blind translation were adopted for this purpose (Brislin, 1986), and two expert translators achieved this to ensure the consistency and the equivalence of the meanings. The first translated from English to Chinese, and the second did the reverse translation from Chinese back to English as recommended by Hambleton (2005). Two professors in the research team and four doctoral students helped judge and certify the content validity of those same items. A pilot study was conducted on 45 nurses before the survey was released online. The pilot testing was proper to refine the items and ensure no ambiguities with the meanings. Fortunately, no significant issues were pointed out by nurses. Besides, nurses enrolled for that were not included in the final analysis.

Perceived organizational justice was measured using one of the most widely used justice measures proposed by Colquitt (2001). The scale has 20 items distributed among four dimensions: distributive justice (4 items), procedural justice (7 items), interpersonal justice (4 items), and informational justice (5 items). The constructs showed good internal consistency and reliability, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.78 to 0.93 (Colquitt, 2001; Omar et al., 2018). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a stronger perception of justice. It is a well-validated scale, used in several other studies and across various settings (Díaz-Gracia et al., 2014; Omar et al., 2018). The overall instrument Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study was 0.746, and that of the different constructs was 0.936, 0.922, 0.871, and 0.889 for distributive justice, procedural justice, interpersonal justice, and informational justice, respectively.

Job engagement was assessed using five items of the job engagement scale taken from the study of Jung et al. (2021), which they adapted from Schaufeli et al. (2002) and Schaufeli et al. (2006). Responses were rated on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always), and higher scores showed greater engagement. The Cronbach’s overall alpha of 0.97 indicated a high internal consistency (Jung et al., 2021). The reliability result of the items for this work was 0,877, judged acceptable.

The perception of nurses’ alternative job opportunities was analyzed using three items, rated on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An increase in the score indicated an increased perception of job alternatives. The scale was picked from the work of Mushtaq et al. (2014), which they adapted from Mowday et al. (1984). Their study reported a good predictive validity and reliability of the scale (Cronbach alpha = 0.73; Mushtaq et al., 2014), and in this study, the internal consistency was also good, being 0.941.

The three-item turnover intention scale developed by Singh et al. (1996) was adopted for this study. Its predictive validity and reliability were initially 0.89 and, in the current research, 0.831. Answers were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). A higher score suggested an increase in the intention to leave.

SPSS version 26 was used to analyze the descriptive aspects of the data and to perform exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The EFA helped ensure that the survey items were loaded under their predicted components. Besides, AMOS version 22 was used to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The CFA was conducted to provide additional robust support to the data set. We also used hierarchical regression analysis in SPSS to test the various hypothesized relationships.

Of the 576 responses received, 72.7% (419) were female nurses, and 27.3% (157) were males. Their ages were distributed among 20–30 (40.3%), 31–40 (37.3%), and 41–50 (22.4%) years old. Also, 354 (61.5%) graduated from the university, and 222 (38.5%) studied in a vocational school. There were 239 (41.5%) formally employed nurses, while 337 (58.5%) worked on a contract basis. Moreover, 451 (78.3%) nurses were married, and 125 (21.7%) were not. Regarding their salary, about 385 (66.8%) nurses admitted receiving a monthly salary greater than 5,000 RMB, 83 (14.4%) and 79 (13.7%) said their monthly salary range is between 4,001–5,000 RMB, and 3,001–4,000 RMB, respectively, the rest of 29 (5%) said they receive less than 3,000 RMB a month. Among the participants, 271 (47%) have been working for more than ten (10) years, 166 (28.8%) for 6–10 years, 126 (21.9%) for 1–5 years, and only 13 (2.3%) have worked for less than a year.

Podsakoff et al. (2003) indicate that common method biases could exist if data is collected from single sources. Therefore, this current study employed procedural and statistical approaches recommended in previous studies (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2010; Jordan and Troth, 2020; and Rodríguez-Ardura and Meseguer-Artola, 2020) in handling issues related to a common method bias. Procedurally, we obtained permission from appropriate authorities, guaranteed respondents’ anonymity and confidentiality, and encouraged respondents to respond to the questionnaire items honestly since there was no right or wrong answer. We statistically checked for common method bias by performing Harman’s single factor test with exploratory factor analysis in SPSS version 26 software. The results showed that a single factor could explain only 26.251% of the total variance. Hence, a single could not account for more than 50% of the total variance, suggesting that our data did not suffer from common method biases.

The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results showed that all items had good loadings above 0.50. The recorded values of Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO-MSA; 0.886) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS; X2 = 12,518.172; df = 465; p < 0.001) were within acceptable thresholds.

As shown in Table 1, the CFA’s factors loadings revealed that the factor loadings for the variables were greater than the 0.50 suggested thresholds (0.669–0.999). Each factor loading had a significant value of p < 0.001.

Using SPSS to test the Cronbach’s Alpha reliability, the outcomes (see Table 1) revealed that each factor had a Cronbach’s Alpha above the 0.70 thresholds (0.831–0.941). These results imply that the scales used to assess the various constructs had good internal consistency.

The study further checked the validity of the constructs with composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) with the help of the AMOS plugin developed by Gaskin and Lim (2016). This AMOS plugin could automatically generate CR, AVE, discriminant validity (DV), and the correlation table using standardized coefficients and correlation values.

As seen in Table 1, all the CR values exceeded the 0.70 cutoffs (0.846–0.941), and those of AVE were higher than the 0.50 thresholds (0.594–0.841), as suggested by Joreskog and Sorbom (1993). These results show that the constructs had good convergent validity. Moreover, the discriminant validity values in bold along the diagonal path of the latent factor correlation matrix were greater than their corresponding inter-factor correlation coefficients (see Table 2). The DV results show that although the variables are related, they are unique and distinct from each other.

Furthermore, a CFA model fit comparison test was done to establish the best model fit for the data set. As displayed in Table 3, the outcomes revealed that a 7-factor model fits best the data set in comparison to a 4-factor model and a 1-factor model, with Chi-square statistics (X2 = 498.299) to degrees of freedom (df = 413), normed Chi-square fit index (X2/df) = 1.207 (X2/df < 3.0 thresholds according to Hu and Bentler (1999)), comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.993, Tucker–Lewis fit index (TLI) = 0.992, and goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.947 (CFI, TLI, GFI > 0.90 benchmark as suggested by Schuenemeyer (1989)). Likewise, the values of the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.028, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.019 were within the acceptable levels, <0.08 and < 0.06, respectively (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

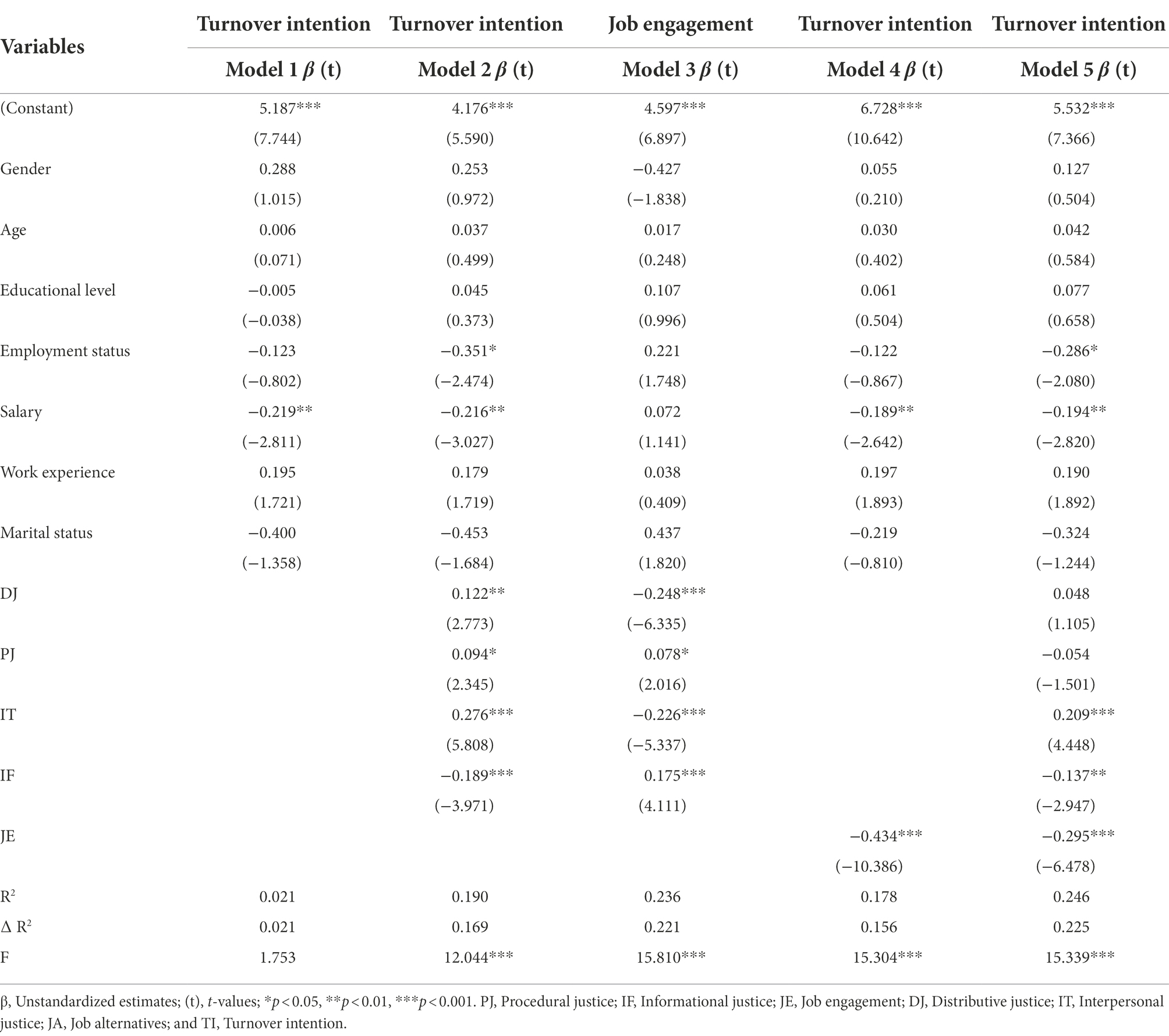

Using SPSS, hierarchical regression analysis helped estimate the main and mediating effects hypotheses, and the results are displayed in Table 4. The demographic characteristics such as gender, age, educational level, employment status, salary, work experience, and marital status were used as control variables. Model 2 in Table 4 shows the results of the effect of organizational justice on turnover intention. Distributive justice (β = 0.122, p < 0.010), procedural justice (β = 0.094, p < 0.050), and interpersonal justice (β = 0.276, p < 0.001) had a significant positive influence on frontline nurses’ turnover intention, making H1a, H1b, and H1c not supported. Contrariwise, informational justice (β = −0.189, p < 0.001) had a significant negative influence on nurses’ turnover intention; thus, H1d was supported. Likewise, Model 3 in Table 4 depicts the effect of organizational justice with all its subscales on job engagement. Distributive justice (β = −0.248, p < 0.001) and interpersonal justice (β = −0.226, p < 0.001) exerted a significant but negative effect on nurses’ job engagement, hence, H2a and H2c were not supported. However, procedural justice (β = 0.078, p < 0.050) and informational justice (β = 0.175, p < 0.001) both significantly and positively affected nurses’ job engagement, H2b and H2d were supported. Model 4 in Table 4 revealed that job engagement significantly and negatively predicted turnover intention (β = −0.434, p < 0.001), favoring H3.

Table 4. Hierarchical regression analysis results of the main effect and the mediating effect of job engagement.

Moreover, Model 5 in Table 4 presents the indirect impact of the different dimensions of organizational justice on turnover intention through job engagement. The outcomes highlighted that when job engagement is applied in the relationship between organizational justice and turnover intention, distributive justice, and procedural justice exert non-statistically significant impacts on turnover intention. However, job engagement (β = −0.295, p < 0.001) still significantly affected the turnover intention, implying that job engagement fully mediated those relationships. Hence, H4a and H4b were supported. On the other hand, interpersonal justice (β = 0.209, p < 0.001) and informational justice (β = −0.137, p < 0.010) had statistically significant influences on turnover intention in the presence of job engagement as a mediator. Since job engagement’s influence on turnover intention was still significant, this implied a partial mediation for job engagement in those relationships. H4c and H4d were also favorable.

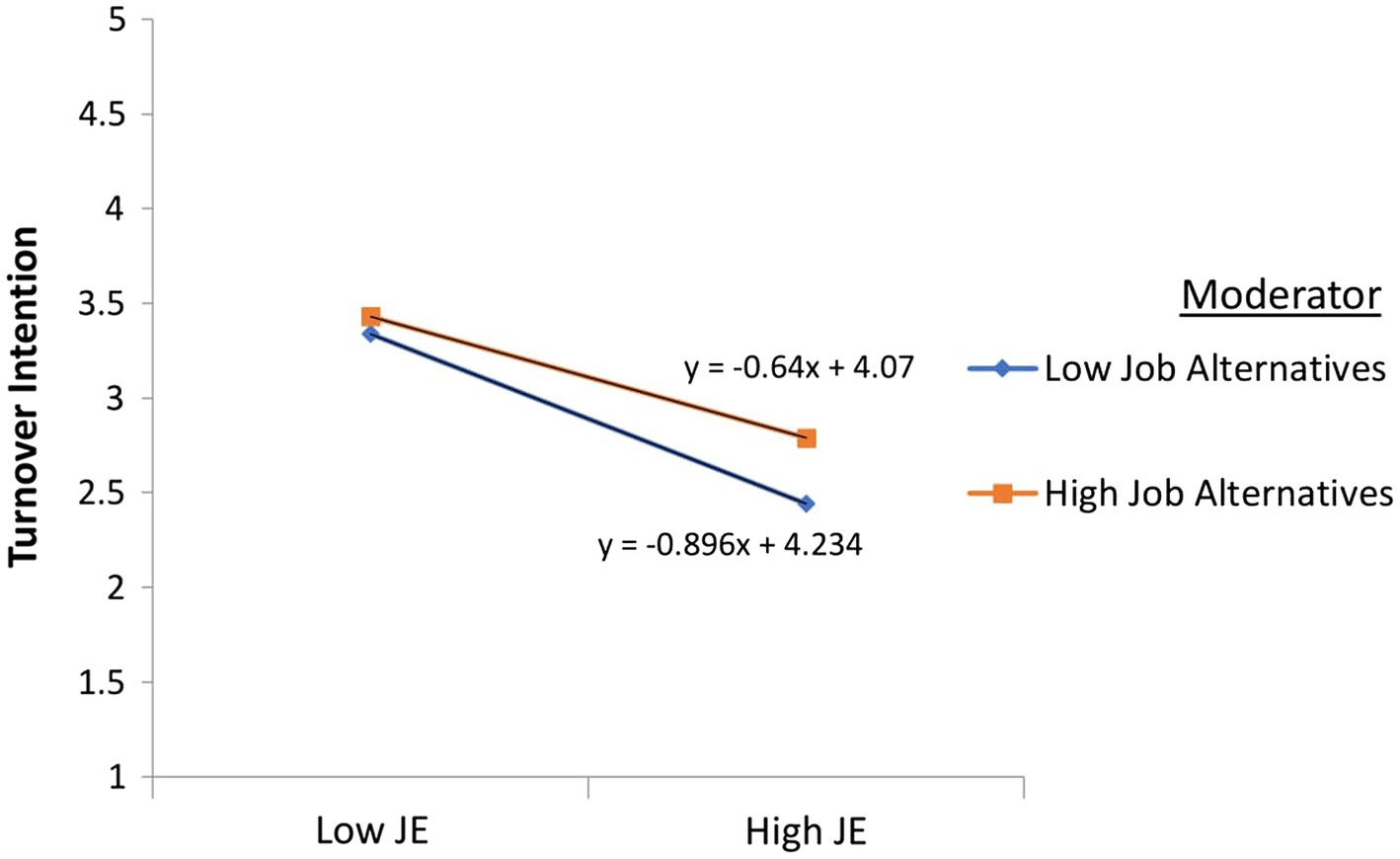

Hierarchical regression analysis was also used with mean-centered variables (to avoid multicollinearity) to test the moderating effect of perceived job alternatives on the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention. From Model 2 in Table 5, it is still observed that job engagement significantly affected turnover intention negatively after being centralized, giving additional support for H3. Based on the estimation of Model 3 in Table 5, job engagement (β = −0.384, p < 0.001) and perceived job alternatives (β = 0.110, p < 0.010) had a negative and positive statistically significant influence on turnover intention, respectively. The same model also revealed that the interaction of job engagement and perceived job alternatives (β = 0.064, p < 0.050) was statistically significant. These outcomes suggest that perceived job alternatives moderated the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention, supporting H5.

This study was conducted under the challenging sanitary context of COVID-19. It aimed to establish the direct and indirect relationships between organizational justice and turnover intention through job engagement as a mediator. It was also a matter of testing the moderating effect of perceived job alternatives on the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention. The different scales were proven valid and reliable under the study’s conditions. Moreover, hierarchical regression analysis outcomes provided additional evidence for the suggested hypotheses.

The results from the analysis indicated that three aspects of justice (distributive, procedural, and interpersonal) significantly and positively influenced turnover intention. These findings do not agree with our hypotheses and are inconsistent with most past research studies, where distributive justice (Akgunduz and Cin, 2015; Yang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022), procedural justice (Kumar, 2015; Gharbi et al., 2022), and interpersonal justice (Leineweber et al., 2020) were mainly observed to affect turnover intention negatively.

The implication could be that during the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese frontline nurses felt injustice or unfairness in the distribution of outcomes, the procedure enactment, and interpersonal relationships at work, especially with their superiors. They could have perceived that their input was not rewarded accordingly, the decision-making procedures were inaccurate, and their relationships with their supervisors did not match their expectations.

Moreover, looking at the different distributive aspects (equity, equality, and need), the organizations might have applied equality instead of equity or need during their distribution of outcomes and decision processes, stipulating that being at the front line was not considered an extra investment that should be explicitly rewarded or what nurses would have liked was not necessarily needed. Contrariwise, the companies could have promoted esprit de corps and built group cohesion among workers by applying equality and dealing with available resources (Colquitt et al., 2005).

Interpersonal justice exacerbated turnover intention could also reveal that frontline nurses did not appreciate how their supervisors related to them. Instead of acting with courtesy and respect, they might have bruised their emotions, which could mitigate their level of acceptance of decisions and increase their intention to leave (Colquitt et al., 2013).

Only informational justice was found to affect turnover intention negatively, meaning that the way information was shared with frontline nurses did not automatically increase their desire to leave. This result aligns with prior findings (Suifan et al., 2017; Hussain and Khan, 2019). When it first appeared, COVID-19 was an unknown disease; information and procedures had to be updated frequently, sometimes daily, which was not easy to handle for frontline nurses (Sampaio et al., 2021). Moreover, the Chinese government marshaled important resources to control the pandemic successfully, and frontline nurses might have appreciated these efforts (Zhang Y. et al., 2020). Still, even if the information was misgiven or without manners, nurses might have understood that it was related to the uncommon and challenging situation and showed good attitudes toward their organizations.

In this study, distributive justice and interpersonal justice were found to significantly and negatively affect job engagement, while procedural justice and informational justice positively and significantly affected job engagement. These results are consistent with several empirical works that concluded a significant prediction of job engagement by organizational justice (Maslach et al., 2001; Saks, 2006; Ghosh et al., 2014; Pieters, 2018; Gupta et al., 2019; Suifan et al., 2020). Studies reported that distributive justice and procedural justice were positively related to job engagement (Pandey and David, 2013; Rasheed and Khan, 2013; Özer et al., 2017; Pakpahan et al., 2020), corroborating this study’s findings on procedural justice but contradicting the results concerning distributive justice. As for informational justice, this research’s outcome agrees with the works of Pakpahan et al. (2020) and Özer et al. (2017) but disagrees with those studies concerning interpersonal justice. Indeed, within a fair working environment, employees tend to be highly engaged and perform better (Suharti and Suliyanto, 2012). Employees’ participation in decision-making makes them feel valuable to the organization and enhances their engagement (Bin, 2016). Ghosh et al. (2014) contented that individuals’ satisfaction in allocating outcome procedures is not always related to their received outcomes. If they judged the distribution process fair and the products unfavorable, they can still boost their inner esteem and self-worth and respond with more engagement (Colquitt et al., 2005).

The pandemic context was not that appropriate for judging the procedures reasonably (Maben and Bridges, 2020; Mo et al., 2020; Zhang Y. et al., 2020). Because people’s lives were suddenly in danger, a quick response-action needed to be made, most of the decisions were taken from above, and nurses had to be executors (Cai et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2021). They probably could understand that, but still, they might not have been happy with the distribution of resources, outcomes, and the treatment manners of their supervisors. With stress, fear, and distress of the moment, they probably wished their superiors understood them more and acted with particular attention, kindness, and dignity and rewarded them accordingly.

The findings also revealed a negative and significant influence of job engagement on turnover intention, corroborating several similar results from previous research (Lu et al., 2016; Moo and Sung, 2017; Zhang et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2020; Zhang and Li, 2020). This prediction was strangely insignificant in Mi et al. (2020) work.

Moreover, job engagement significantly mediated the relationships between organizational justice and turnover intention, concurring with other studies (Al-Shbiel et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2020). Kaya et al. (2016) opined that good organizational practices enhance employees’ loyalty and belongingness to the company, reducing the intention to leave. Engaged workers will interact affectively with their work; regardless of the challenges, they will try not to lose motivation and show willingness and persistence to do their job well (Lu et al., 2016).

That says, during the COVID-19, frontline nurses showed a palpable dedication to their job and loyalty to the country and their organization by accepting to be at the front. The above finding suggests that while some organizational practices shook nurses’ engagement, they did not automatically expose a greater intention to leave.

The analysis’s introduction of perceived job alternatives exhibited interesting results and gave more insights concerning this variable’s influence on turnover intention. Findings highlighted that perceived job alternatives positively affected the leaving intent and moderated the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention. For instance, nurses’ likelihood of getting alternative jobs weakened that relationship, as shown in Figure 2. In this situation, employees could have a duality of affectivity and context. Though liking their career, extreme working conditions and the dangerous workplace could instigate their desire to continue in that profession, depending on the availability of alternative employment (Mushtaq et al., 2014). Contextually, the presence of COVID-19 not only downturned the economy but also increased unemployment, threatening nurses’ confidence in job availability (Song et al., 2020).

Figure 2. Moderating effect of perceived job alternatives on job engagement and turnover intention relationship.

This study revealed theoretical and practical contributions in exploring how organizational justice can influence turnover intention in critical times. Theoretically, this work extends the literature on the variables involved in the conceptual framework, confirming the influencing strength of the causal variables, particularly in the nursing industry. First, in exploring organizational justice’s influence on turnover intention, this study has extended the knowledge on the specific aspects of organizational justice that significantly affect turnover intention. It has been demonstrated that interpersonal justice has the greatest predictive capacity on turnover intention, followed by informational justice, distributive justice, and procedural justice. Second, the integration of job engagement as a mediator supports the motivational role job resources should play to mitigate the adverse effects of job demands and foster the achievement of organizational goals (Schaufeli and Taris, 2014). In this study, job engagement has successfully mediated the relationship between the determinant variable (organizational justice) and the consequent variable (turnover intention), showing the nurses’ willingness to spend compensatory effort to attain their objectives. Therefore, the social exchange theory (SET) finds additional support in this study. Third, perceived job alternatives have been proven to weaken the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention. This supposes that the cognitive aspect of looking for alternative job opportunities is prompted in employees whose mental resilience, enthusiasm, and focus are challenged by limited resources, making them think of leaving (Hom et al., 2012; Mitchell et al., 2015). These findings reveal that inadequate treatments deteriorate the value of exchange and reciprocity expected in the workplace (Omar et al., 2018), giving additional explanation and support to the social exchange theory.

Practically, the study explicitly highlighted the justice aspects relevant to frontline nurses in critical times to enhance their staying intent. Some elements of organizational justice were found to exacerbate nurses’ engagement and turnover intent. The study’s outcomes encourage healthcare managers to provide frontline nurses with physical, psychological, and physiological resources to help them restrain job demands and associated costs (Bakker et al., 2007). Doing so will promote nurses’ personal growth, learning, and development and better equip them to attain their institutional aspirations (Moo and Sung, 2017; Scanlan and Still, 2019). As Yang et al. (2021) argued, the depletion of workers’ valuable resources does not favor their willingness to stick to the organization’s goals but instigates their intention to leave. The ability of perceived job alternatives to weaken the relationship between job engagement and turnover intention confirms frontline nurses’ unfavorable conditions and limited resources. Overall, it is suggested that good organizational practices should be promoted in medical companies to improve workers’ constructive attitudes and behaviors. Besides, increasing the perception of justice in the workplace can boost individuals’ engagement, making employees more enthusiastic about achieving the firm’s objectives. Such practices can also help curb leaving thoughts and active search for alternative employment opportunities, even in tough times.

Although this work had many contributions, it also presented some limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the study restraints it in a certain period. A longitudinal study may provide more substantial results of the hypothesized causal effects. Though the constructs of primary importance for this study showed significant influence on turnover intention, future studies may consider other personal and organizational variables such as work environment, routinization, negative affectivity, burnout, workplace violence, or comparison with the present job and explore their level of influence on nurses’ desire to stay in their profession. Moreover, the survey was conducted only in Jiangsu province, China, and among frontline nurses. Hence, generalizing the findings may not be appropriate. Since COVID-19 is still relevant in the whole country and the hypothesized relationships showed significant results, a similar approach can be tested nationwide, including more healthcare actors.

This work showed that turnover intention among frontline nurses was exacerbated by poor implementation of distributive, procedural, and interpersonal justice. However, procedural and informational justice enhanced job engagement, while distributive and interpersonal justice negatively affected it. The intervention of job engagement as a mediator could mitigate the manifestations of the poor effects of distributive and procedural justice on nurses leaving intentions since it fully mediated those relationships. Still, the mediation was only partial for interpersonal and informational justice. Moreover, job engagement negatively influenced nurses’ turnover intention, and perceived job alternatives moderated that relationship by weakening its strength. This research’s findings and implications may give health policymakers and nursing managers insights into addressing the continual nursing shortage by controlling the turnover intention causing forces in critical times.

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jiangsu University, with the approval number JU-IRB: 05/08/21. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AK: conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation. PQ: methodology and formal analysis. TE: software and visualization. EN and SA-W: validation and data curation. EN: investigation. XX and AK: resources. TE and PQ: writing—review and editing. LZ: supervision. XX: project administration. LZ and XX: funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 71974079) and the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. 20SHD002).

The authors are thankful to the administrators in the study hospitals who helped to share the survey link with the nurses and all the nurses who participated in this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agarwal, U. A. (2014). Examining the impact of social exchange relationships on innovative work behaviour: role of work engagement. Team Perform. Manag. 20, 102–120. doi: 10.1108/TPM-01-2013-0004

Agbaeze, E. K., Ogbo, A., and Nwadukwe, U. C. (2018). Organizational justice and turnover intention among medical and non-medical workers in university teaching hospitals. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 9, 149–160. doi: 10.2478/mjss-2018-0035

Akgunduz, Y., and Cin, F. M. (2015). Job embeddedness as a moderator of the effect of manager trust and distributive justice on turnover intentions. Anatolia 26, 549–562. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2015.1020504

Al Sabei, S. D., Labrague, L. J., Miner Ross, A., Karkada, S., Albashayreh, A., Al Masroori, F., et al. (2020). Nursing work environment, turnover intention, job burnout, and quality of care: the moderating role of job satisfaction. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 52, 95–104. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12528

AL-Abrrow, H. A., Ardakanib, M. S., Haroonic, A., and Pour, H. M. (2013). The relationship between organizational trust and organizational justice components and their role in job involvement in education. Int. J. Manag. Acad. 1, 25–41.

Al-Shbiel, S. O., Ahmad, M. A., Al-Shbail, A. M., Al-Mawali, H., and Al-Shbail, M. O. (2018). The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between organizational justice and junior accountants’ turnover intentions. Acad. Account. Finan. Stud. J. 22, 1–23.

Al-Tit, A., and Hunitie, M. (2015). The mediating effect of employee engagement between its antecedents and consequences. J. Manag. Res. 7, 47–62. doi: 10.5296/JMR.V7I5.8048

Ancarani, A., Di Mauro, C., Giammanco, M. D., and Giammanco, G. (2018). Work engagement in public hospitals: A social exchange approach. Int. Rev. Pub. Admin. 23, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/12294659.2017.1412046

Bakker, A. B., Albrecht, S. L., and Leiter, M. P. (2011). Key questions regarding work engagement. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psy. 20, 4–28. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2010.485352

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., and Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 274–284. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Baş, M., and Çınar, O. (2021). The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between perceived organizational support and turnover intention-with an application to healthcare employees in erzincan province of turkey. Ekonomski Vjesnik 34, 291–306. doi: 10.51680/ev.34.2.4

Bautista, J. R., Lauria, P. A. S., Contreras, M. C. S., Maranion, M. M. G., Villanueva, H. H., Sumaguingsing, R. C., et al. (2020). Specific stressors relate to nurses’ job satisfaction, perceived quality of care, and turnover intention. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 26:e12774. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12774

Bidarian, S., and Jafari, P. (2012). The relationship Between organizational justice and organizational trust. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 47, 1622–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.873

Bies, R. J., and Moag, J. F. (1986). “Interactional justice: communication criteria of fairness,” in Research on Negotiations in Organizations. eds. R. J. Lewicki and B. H. Sheppard (Bazerman: JAI Press), 43–55.

Bin, A. S. (2016). The relationship between job satisfaction, work performance, and employee engagement: an explorative study. Issues Bus. Manag. Econ. 4, 1–8. doi: 10.15739/IBME.16.001

Brislin, R. W. (1986). “The wording and translation of research instruments,” in Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. ed. J. W. B. Lonner (California, Oaks: Sage), 133–164.

Cai, H., Tu, B., Ma, J., Chen, L., Fu, L., Jiang, Y., et al. (2020). Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan Between January and march 2020 During the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med. Sci. Monit. 26:e924171. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924171

Cao, T., Huang, X., Wang, L., Li, B., Dong, X., Lu, H., et al. (2020). Effects of organizational justice, work engagement, and nurses’ perception of care quality on turnover intention among newly licensed registered nurses: A structural equation modeling approach. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 2626–2637. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15285

Carlson, J. R., Carlson, D. S., Zivnuska, S., Harris, R. B., and Harris, K. J. (2017). Applying the job demands resources model to understand technology as a predictor of turnover intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 77, 317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.009

Cassar, V., and Buttigieg, S. (2015). Psychological contract breach, organizational justice and emotional wellbeing. Pers. Rev. 44, 217–235. doi: 10.1108/pr-04-2013-0061

Cattell, R. B. (1978). The scientific use of factor Analysis in Behavioral and life Sciences. New York, NY:Plenum.

Catton, H. (2020). Global challenges in health and health care for nurses and midwives everywhere. Int. Nurs. Rev. 67, 4–6. doi: 10.1111/inr.12578

Chang, C. S. (2014). Moderating effects of nurses’ organizational justice between organizational support and organizational citizenship behaviors for evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 11, 332–340. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12054

Chang, S.-J., Van Witteloostuijn, A., and Eden, L. (2010). From the Editors: Common Method Variance in International Business Research. United States: Springer.

Chatterjee, S., and Hadi, A. S. (2015). Regression Analysis by Example. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons.

Chen, H., and Jin, Y.-H. (2014). The effects of organizational justice on organizational citizenship behavior in the Chinese context: The mediating effects of social exchange relationship. Pub. Person. Manag. 43, 301–313. doi: 10.1177/0091026014533897

Chen, D., Lin, Q., Yang, T., Shi, L., Bao, X., and Wang, D. (2022). Distributive justice and turnover intention Among medical staff in Shenzhen, China: The mediating effects of organizational commitment and work engagement. Risk Manag. Healthcare Pol. 15, 665–676. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S357654

Chênevert, D., Jourdain, G., Cole, N., and Banville, B. (2013). The role of organisational justice, burnout and commitment in the understanding of absenteeism in the Canadian healthcare sector. J. Health Organ. Manag. 27, 350–367. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-06-2012-0116

Colquitt, J. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: a construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 386–400. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.386

Colquitt, J. A., Greenberg, J., and Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2005). “What is organizational justice? A historical overview,” in Handbook of Organizational Justice. eds. J. Greenberg and J. A. Colquitt (NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 3–56.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., et al. (2013). Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A metaanalytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 98, 199–236. doi: 10.1037/a0031757

Cook, K. S. (2015). “Exchange: Social,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. ed. J. D. Wright. 2nd Edn. (Oxford: Elsevier), 482–488.

Cropanzano, R., Bowen, D., and Gilliland, S. (2007). The Management of Organizational Justice. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 21, 34–48. doi: 10.5465/AMP.2007.27895338

Cropanzano, R., and Mitchell, M. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 31, 874–900. doi: 10.1177/0149206305279602

Derycke, H., Vlerick, P., Burnay, N., Decleire, C., D’Hoore, W., Hasselhorn, H., et al. (2011). Impact of the effort–reward imbalance model on intent to leave among Belgian health care workers: a prospective study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83, 879–893. doi: 10.1348/096317909X477594

Díaz-Gracia, L., Barbaranelli, C., and Moreno-Jiménez, B. (2014). Spanish version of Colquitt’s organizational justice scale. Psicothema 26, 538–544. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2014.110

Dohlman, L., Di Meglio, M., Hajj, J., and Laudanski, K. (2019). Global brain drain: how can the Maslow theory of motivation improve our understanding of physician migration? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:1182. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071182

Edwards-Dandridge, Y. M. (2019). Work engagement, job satisfaction, and nurse turnover intention. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies. Available at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/6323 (Accessed March 19, 2022).

Edwards-Dandridge, Y. M., Simmons, B. D., and Campbell, D. G. (2020). Predictor of turnover intention of register nurses: job satisfaction or work engagement? Int. J. Appl. Manag. Technol. 19, 87–96. doi: 10.5590/IJAMT.2020.19.1.07

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2, 335–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

Fardid, M., Hatam, N., and Kavosi, Z. A. (2018). Path analysis of the effects of nurses’ perceived organizational justice, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction on their turnover intention. Nurs. Midwifery Studies 7, 157–162. doi: 10.4103/nms.nms_13_18

Fodchuk, K. M. (2009). Organizational justice perceptions in China: Development of the Chinese Organizational Justice Scale. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Dissertation, Psychology, Old Dominion University.

Gharbi, H., Aliane, N., Al Falah, K. A., and Sobaih, A. E. E. (2022). You really affect me: The role of social influence in the relationship between procedural justice and turnover intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:162. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095162

Ghosh, P., Rai, A., and Sinha, A. (2014). Organizational justice and employee engagement: exploring the linkage in public sector banks in India. Pers. Rev. 43, 628–652. doi: 10.1108/PR-08-2013-0148

Gupta, A., Tandon, A., and Barman, D. (2019). Employee Engagement. Manag. Techn. Employee Engag. Contemp. Organiz. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-7799-7.CH001

Hambleton, R. K. (2005). “Issues, designs, and technical guidelines for adapting tests into multiple languages and cultures,” in Adapting Educational and Psychological Tests for Cross-Cultural Assessment. eds. R. K. Hambleton, P. F. Merenda, and C. D. Spielberger (NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 7–25.

He, R., Liu, L. L., Zhang, W. H., Zhu, B., Zhang, N., and Mao, Y. (2020). Turnover intention among primary health workers in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Med. J. Open. 10. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037117

Hom, P. W., Mitchell, T. R., Lee, T. W., and Griffeth, R. W. (2012). Reviewing employee turnover: focusing on proximal withdrawal states and an expanded criterion. Psychol. Bull. 138, 831–858. doi: 10.1037/a0027983

Hou, H., Pei, Y., Yang, Y., Lu, L., Yan, W., Gao, X., et al. (2021). Factors associated with turnover intention Among healthcare workers During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in China. Am. J. Top. Med. Hyg. 14, 4953–4965. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S318106

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, X., Li, Z., and Wan, Q. (2019). From organisational justice to turnover intention among community nurses: A mediating model. J. Clin. Nurs. 28, 3957–3965. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15031

Hussain, M., and Khan, M. S. (2019). Organizational justice and turnover intentions: probing the Pakistani print media sector. Evidence-based HRM 7, 180–197. doi: 10.1108/EBHRM-04-2018-0030

Irshad, M., Khattak, S. A., Hassan, M. M., Majeed, M., and Bashir, S. (2021). How perceived threat of COVID-19 causes turnover intention among Pakistani nurses: A moderation and mediation analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 30:350. doi: 10.1111/inm.12775

Jin, M., McDonald, I. B., and Park, J. (2016). Person-organization fit and turnover intention: exploring the mediating role of employee followership and job satisfaction Through conservation of resources theory. Rev. Pub. Person. Admin. 38, 167–192. doi: 10.1177/0734371X16658334

Jordan, P. J., and Troth, A. C. (2020). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of reasearching in organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 45, 3–14. doi: 10.1177/0312896219871976

Juhdi, N., Pa’wan, F., and Hansaram, R. M. K. (2013). HR practices and turnover intention: the mediating roles of organizational commitment and organizational engagement in a selected region in Malaysia. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24, 3002–3019. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.763841

Jung, H. S., Jung, Y. S., and Yoon, H. H. (2021). The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 92:102703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102703

Kaya, N., Aydin, S., and Ayhan, O. (2016). The effects of organizational politics on perceived organizational justice and intention to leave. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 6, 249–258. doi: 10.4236/ajibm.2016.63022

Kumar, N. K. (2015). Role of perceived organizational support and justice on employee turnover intentions: employee engagementas mediator. Int. J. manag. Appl. Sci. 1, 106–112.

La Forgia, G. M., and Yip, W. (2017). “China’s hospital sector,” in China’s Healthcare System and Reform. eds. L. R. Burns and G. G. E. Liu (London: Cambridge University Press), 219–249.

Labrague, L., and de Los Santos, J. A. (2020). Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction, and turnover intention among frontline nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 29, 395–403. doi: 10.1111/JONM.13168

Lambe, C. J., Wittmann, C. M., and Spekman, R. E. (2001). Social exchange theory and research on business-to-business relational exchange. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 8, 1–36. doi: 10.1300/J033v08n03_01.S2CID167444712

Leineweber, C., Peristera, P., Bernhard-Oettel, C., and Eib, C. (2020). Is interpersonal justice related to group and organizational turnover? Results from a Swedish panel study. Soc. Sci. Med. 265:113526. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113526

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). “What should be done with equity theory?” in Social Exchange. eds. K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, and R. H. Willis (MA: Springer), 27–55.

Li, J. J., Mitchel, T. R., Hom, P. W., and Griffeth, R. W. (2016). The effects of proximal withdrawal states on job attitudes, job searching, intent to leave, and employee turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 1436–1456. doi: 10.1037/apl0000147

Lu, L., Lu, A. C. C., Gursoy, D., and Neale, N. R. (2016). Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison between supervisors and line-level employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 28, 737–761. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-07-2014-0360

Maben, J., and Bridges, J. (2020). Covid-19: supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 2742–2750. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15307

Marć, M., Bartosiewicz, A., Burzyńska, J., Chmiel, Z., and Januszewicz, P. (2019). A nursing shortage – a prospect of global and local policies. Int. Nurs. Rev. 66, 9–16. doi: 10.1111/inr.12473

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Memon, M. A., Salleh, R., Baharom, M. N. R., and Harun, H. (2014). Person-organization fit and turnover intention: The mediating role of employee engagement. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 6:205

Mengstie, M. M. (2020). Perceived organizational justice and turnover intention among hospital healthcare workers. BMC Psychol. 8:19. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-0387-8

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., and Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 78, 538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

Mi, Y., Jang, M., and Li, S. S. (2020). Structural Relationship between Authentic Leadership, Job Engagement, Job Burnout, and Turnover Intention among Workers in the Service Industry: Multi-Group Analysis by Emotional Labor Intensity. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 39, 39–62. doi: 10.37210/JVER.2020.39.6.39

Mitchell, T. R., Li, J. J., Lee, T., Hom, W. P., and Griffeth, R. (2015). The effects of proximal withdrawal state on attitudes, job search, intent to quit and turnover. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015:12265. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2015.12265abstract

Mo, Y., Deng, L., Zhang, L., Lang, Q., Liao, C., Wang, N., et al. (2020). Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 28, 1002–1009. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13014

Moo, L. J., and Sung, P. Y. (2017). The effects of job demands and job resources on turnover intention and mediating effect of job engagement of child-care teachers. Korean J. Child Care Educ. Pol. 11, 1–28. doi: 10.5718/kcep.2017.11.1.1

Mowday, R. T., Koberg, C. S., and McArthur, A. W. (1984). The psychology of the withdrawal process: a cross-validational test of Mobley’s intermediate linkages model of turnover in two samples. Acad. Manag. J. 27, 79–94.

Mushtaq, A., Amjad, M. S., Bilal, B., and Saeed, M. M. (2014). Perceived alternative job opportunities between organizational justice and job satisfaction: evidence from developing countries. East Asian J. Bus. Manag. 4, 5–13. doi: 10.13106/eajbm.2014.vol4.no1.5

Nie, A., Su, X., Zhang, S., Guan, W., and Li, J. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on frontline nurses: a cross-sectional survey study. J. Clin. Nurs. 29, 4217–4226. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15454

Nojani, M. I., Arjmandnia, A., Afrooz, G., and Rajabi, M. (2012). The study on relationship between organizational justice and job satisfaction in teachers working in general, special and gifted education systems. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 46, 2900–2905. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.586

Obeng, A. F., Zhu, Y., Quansah, P. E., Ntarmah, A. H., and Cobbinah, E. (2021). High-performance work practices and turnover intention: investigating the mediating role of employee morale and the moderating role of psychological capital. SAGE Open 11:215824402098855. doi: 10.1177/2158244020988557

Ohana, M. (2014). A multilevel study of the relationship between organizational justice and affective commitment: The moderating role of organizational size and tenure. Pers. Rev. 43, 654–671. doi: 10.1108/pr-05-2013-0073

Omar, A., Salessi, S., Vaamonde, J., and Urqueaga, F. (2018). Psychometric properties of Colquitt’s organizational justice scale in argentine workers. Liberabit 24, 61–79. doi: 10.24265/liberabit.2018.v24n1.05

Özer, Ö., Uğurluoğlu, Ö., and Saygili, M. (2017). Effect of organizational justice on work engagement in healthcare sector of Turkey. J. Health Manag. 19, 73–83. doi: 10.1177/0972063416682562

Pakpahan, M., Eliyana, A., Hamidah, A. D., and Bayuwati, T. R. (2020). The role of organizational justice dimensions: enhancing work engagement and employee performance. Syst. Rev. Pharmacy 11, 323–332.

Pandey, S., and David, S. (2013). A study of engagement at work: what drives employee engagement? EJCMR 2, 155–161.

Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., and Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

Park, K. A., and Johnson, K. R. (2019). Job satisfaction, work engagement, and turnover intention of CTE health science teachers. Int. J. Res. Voc. Educ. Training 6, 224–242. doi: 10.13152/IJRVET.6.3.2

Park, Y., Song, J. H., and Lim, D. H. (2016). Organizational justice and work engagement: the mediating effect of self-leadership. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 37, 711–729. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-09-2014-0192

Perreira, T. A., Berta, W., and Herbert, M. (2018). The employee retention triad in health care: exploring relationships amongst organisational justice, affective commitment and turnover intention. J. Clin. Nurs. 27, e1451–e1461. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14263

Pieters, W. R. (2018). Assessing organizational justice as a predictor of job satisfaction and employee engagement in Windhoek. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 16:928. doi: 10.4102/SAJHRM.V16I0.928

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prakash, R. V., and Murarka, R. (2021). “Understanding Human Rights from an Eastern Perspective: A Discourse,” in Asian Yearbook of International Law. Vol. 24. (Netherlands: Brill Nijhoff), 41–59.

Proost, K., Verboon, P., and van Ruysseveldt, J. (2015). Organizational justice as buffer against stressful job demands. J. Manag. Psychol. 30, 487–499. doi: 10.1108/jmp-02-2013-0040

Quek, S. J., Thomson, L., Houghton, R., Bramley, L., Davis, S., and Cooper, J. (2021). Distributed leadership as a predictor of employee engagement, job satisfaction and turnover intention in UK nursing staff. J. Nurs. Manag. 29, 1544–1553. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13321

Quezada-Abad, C. J., Teijeiro-Álvarez, M. M., Brito-Gaona, L. F., and Freire-Seoane, M. J. (2019). Factor analysis of organizational justice: The case of Ecuador. Europ. Res. Stud. J. 22, 22–50.