- 1The Saudi Investment Bank Chair for Investment Awareness Studies, The Deanship of Scientific Research, The Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

- 2Applied College in Abqaiq, King Faisal University, Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

- 3Adam Smith Business School, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

This study explored the impact of financial literacy (financial awareness) on potential entrepreneurs' intent in Saudi Arabia. It also examined saving behavior as a mediator in the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention. The study's data were collected by an online questionnaire sent to a sample of 270 potential entrepreneurs at Abqaiq Applied College, affiliated with King Faisal University. Data analysis was done using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). According to the findings, there is no direct relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intent. However, it has been reported that saving behavior can mediate between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intent.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship and the small and mid-size enterprise (SME) have been identified as critical drivers of economic growth and development, as well as a means of alleviating poverty (Li et al., 2020a; Yaser Al-Mamary et al., 2020; Alshebami, 2021; Cai et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2021). Entrepreneurship and SMEs have recently received a lot of attention from various scholars and institutions because of their role in assisting individuals and allowing them to develop new ideas, products and services that result in a higher standard of living. More support, however, is still required for their overall development. This support can be institutional (Ali et al., 2021) or psychological, such as enhancing individuals' personal traits (Bhatti et al., 2021). More specifically, the development of entrepreneurial intent among individuals, particularly potential entrepreneurs (qualified students), would necessitate early preparation. Individuals, for example, must develop high self-confidence, tolerate risk, and be willing to innovate (Koh, 1996; Nasip et al., 2017).

In addition, potential entrepreneurs must educate themselves financially and instill the habit of saving to make better investment decisions, make appropriate planning decisions, and seize available business opportunities in the market (Kilara and Latortue, 2012; Rikwentishe et al., 2015a; Li et al., 2020b). This is because financial education, also known as financial knowledge (Gilenko and Chernova, 2021), financial literacy, or financial awareness, is an essential aspect of individuals' financial wellbeing and financial empowerment (Ali et al., 2021). Indeed, financial literacy is defined as the ability to comprehend and apply fundamental financial principles to effectively allocate financial resources and identify market opportunities (Li and Qian, 2020).

It is also the ability to make sound financial and wealth-generation decisions (Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015). Individuals with a high level of financial literacy can easily develop the necessary risk management skills, identify available business opportunities, gain more market knowledge, manage their money more effectively, and make better financial decisions, all of which are critical for the growth of venture creation and entrepreneurship (Hilgert et al., 2003; Klapper et al., 2015; Li and Qian, 2020; Qader et al., 2022). Furthermore, financial literacy can help individuals develop saving habits (Hilgert et al., 2003; Sabri and MacDonald, 2010), leading to the establishment of new businesses or the expansion of existing ones (Rikwentishe et al., 2015b).

Despite the existence of some literature discussing the concept of financial literacy and saving behavior, it is still believed that there is a dearth of research in this area (Lusardi et al., 2009; Arnida et al., 2015), particularly related to young adult saving and financial literacy in developing countries. As a result, it is critical to investigate how financial literacy and saving habits influence the entrepreneurial behavior of potential entrepreneurs (qualified students) in Saudi Arabia, as it is believed that Saudi Arabia has promising economic indicators related to entrepreneurship and SMEs (Ali et al., 2021).

Furthermore, because Saudi Arabia's state budget is heavily reliant on oil revenue, it has found it challenging to meet its obligations due to the budget deficit caused by the continuous fluctuation in oil prices. As a result, the Saudi government created the so-called Saudi Vision 2030, a long-term plan to implement various reforms in various sectors of the economy, including entrepreneurship and SME sectors. The Saudi Vision 2030 aimed to increase the contribution of the SME sector to GDP from 20 to 35%, increase household savings from 6 to 10% of total household income, and reduce unemployment from 11.6 to 7% (Khan and Alsharif, 2019; Aljarodi, 2020; Alshebami et al., 2020; Elnadi and Gheith, 2021). Consequently, to meet the goals of Saudi Vision 2030, it is critical to investigate the impact of certain factors, such as financial literacy and saving behavior, on the entrepreneurial behavior of potential entrepreneurs. This is because it is believed that financial literacy and saving affect individuals' entrepreneurial intent and business creation, either directly or indirectly (Hilgert et al., 2003; Rikwentishe et al., 2015b; Li and Qian, 2020).

However, despite the importance of financial literacy in enhancing entrepreneurial behavior among individuals, it was discovered that there is still a paucity of literature on the subject (Li and Qian, 2020). Moreover, few studies have focused on saving and its role in business creation (Otto, 2009). Additionally, there is a significant gap in financial literacy levels between developed and developing countries (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011). According to the World Bank, the Arab world is ranked as one of the least financially literate regions (The World Bank, 2016). Saudi Arabia, in particular, was identified as one of the poorest countries in terms of financial literacy, with men accounting for ~34% and women accounting for ~29% (Hasler and Lusardi, 2017).

Although only about half of the world's adult population saves money regularly (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018), Saudi Arabia was identified as a country with a lower rate of savings when compared to other countries (The General Authority for Statistics, 2020). Saudis have a financial literacy rate of around 31% (Alshebami and Seraj, 2021). The low savings rate in Saudi Arabia can be attributed to various factors, including low income (King Khaled Foundation, 2018) and a lack of financial literacy (Hailesellasie et al., 2013). Low financial literacy in Saudi Arabia is more prevalent among young people under 37 years old. Therefore, there is a need to improve financial literacy in that group (Sedais and Al Shahab, 2020).

Accordingly, we argue that financial awareness or literacy is required to develop saving habits and entrepreneurial behavior (Delafrooz and Paim, 2011; Li and Qian, 2020). To put it another way, Those individuals who can develop a high level of financial literacy can obtain essential skills to make sound investments and financial decisions, increase their financial freedom, improve their standard of living, and increase their confidence and autonomy (Sohn et al., 2012; Philippas and Avdoulas, 2019; Ali et al., 2021; Gilenko and Chernova, 2021). Financial literacy also helps to prepare individuals with entrepreneurial financial skills, market knowledge, finance sources, financial knowledge, and entrepreneurial intent (Hilgert et al., 2003; Levesque et al., 2009; Li and Qian, 2020). It also enables them to recognize and capitalize on available business (Evan and Jovanovic, 1989). As a result, the following questions will be addressed in this study:

1. Is there a link between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intent among potential Saudi entrepreneurs?

2. Can saving behavior in Saudi Arabia mediate the relationship between financial literacy and the entrepreneurial intent of potential entrepreneurs?

The article is divided into the following sections. After the introduction, it discusses the extant literature and the development of hypotheses. The work then shifts to discussing the research methodology, analysis of the results, and discussion. It then concludes by presenting the implications and conclusions of the study.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Theoretical Underpinnings

According to established theories such as Ajzen (1991) theory of planned behavior and Bandura (1986) social cognitive theory, external factors influence individuals' intentions to perform specific behaviors. These external influences directly influence how people think, perceive and act. In general, intent is a good predictor of individual behavior in the context of business creation. An individual's desire to start their own business is also a cognitive state (Bullough et al., 2014). Personal traits (Koh, 1996; Nasip et al., 2017; Jiatong et al., 2021; Murad et al., 2021; Rafiq and Muhammad, 2021) or level of financial literacy (Evan and Jovanovic, 1989) or individual saving behavior are just a few of the factors that can influence an individual's entrepreneurial intention (Kilara and Latortue, 2012; Rikwentishe et al., 2015b; Tshiaba et al., 2021).

Furthermore, concerning the financial literacy theoretical background, it has been observed that there are no specific measures for measuring financial literacy (Cole and Fernando, 2008; Oseifuah, 2010). We use the measures that measure an individual's knowledge level and behavior developed by Cude et al. (2006) and Thung et al. (2012). Accordingly, we define financial literacy as individuals' ability to make efficient decisions and judgements when managing personal finances (Stolper and Walter, 2017). Also, we use the behavioral life cycle theory (BLCT), which states that mental accounting, framing and self-control are methods for enhancing the savings behavior of individuals (Mpaata et al., 2021).

Financial Literacy and Entrepreneurial Intention

Financial literacy is defined as people's knowledge of financial concepts and how to apply this knowledge to make sound financial decisions (Stolper and Walter, 2017). Financial literacy raises people's awareness of business opportunities and the necessary risk management skills and market knowledge for developing entrepreneurship and business profit (Hilgert et al., 2003). Financial literacy is essential, especially in light of evidence pointing to a lack of funds as a barrier to creating new ventures (Li and Qian, 2020); financial literacy will notify the entrepreneurs of the necessary financial sources for funding their business. Furthermore, because a lack of financial literacy and awareness leads to higher borrowing costs and more debts (Stango and Zinman, 2009), as well as poor financial behavior and business investment, it is assumed that a high level of financial awareness or literacy will lead to a better understanding of finance and its financial means (Li and Qian, 2020). Financial literacy alerts entrepreneurs to the necessary financial sources for funding their business (Glaser and Walther, 2014).

Moreover, financial literacy specifically assists potential entrepreneurs in making better financial decisions, identifying better sources of funding for their start-ups (Levesque et al., 2009), managing their enterprises' budgets, and making strategic business investment decisions. It also aids in the development of entrepreneurial skills, such as recognizing and capitalizing on available market business opportunities (Evan and Jovanovic, 1989). Individuals with higher financial literacy are likelier to act wisely when making risky business investment decisions (Gilenko and Chernova, 2021). They are likelier to participate in more financial services and products and save and invest (Hogarth and Hilgert, 2002).

According to resource-based theory, financial literacy is an intangible source for the entrepreneurial firm (RBV). This is because a high level of financial literacy among individuals in general, and young people in particular, may contribute to promoting entrepreneurial activities such as autonomy and motivation, self-employment (Oseifuah, 2010; Li and Qian, 2020), as well as facilitating the financing source for them. As a result of the previous discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Financial literacy and entrepreneurial intent have a positive relationship.

The Mediating Role of Saving Behavior Between Financial Literacy and Entrepreneurial Intention

Financial literacy is defined as people's ability to clearly understand and interpret their finances to make sound financial decisions. Financial literacy significantly impacts various factors, including individuals' saving behavior (Thung et al., 2012; Arnida et al., 2015). Individuals with a high level of financial literacy can ensure greater financial stability and save more funds for unforeseen events and needs. Individuals' saving behavior is influenced positively by financial literacy (Hilgert et al., 2003; Lusardi et al., 2009; Sabri and MacDonald, 2010; Delafrooz and Paim, 2011). This means that the greater one's financial literacy, the greater one's level of savings, and the greater one's financial wellbeing (Browning and Lusardi, 1996; Gilenko and Chernova, 2021).

Furthermore, although there is very little empirical evidence linking saving and financial literacy (Supanantaroek et al., 2016), existing literature on poor financial literacy indicates that young people with low financial literacy have difficulties managing their economic activities (Sabri et al., 2008), which reduces their ability to save money. As a result, financial literacy encourages people to save regularly, which benefits both individuals and the economy (Gilenko and Chernova, 2021). Individual saving and investment behavior can be influenced by subjective financial assessment as well as personal characteristics (Furnham and Cheng, 2019) as well as personal characteristics.

Furthermore, because financial literacy increases individual savings, it enables people to start new businesses or expand existing ones (Rikwentishe et al., 2015b). Saving provides individuals who want to start small businesses with the necessary business capital and enables them to meet their liquidity challenges (Dunn and Holtz-Eakin, 2000; Kilara and Latortue, 2012; Bosumatari, 2014). Savings are essential for funding individuals and businesses, especially potential entrepreneurs or so-called students (Kilara and Latortue, 2012). As a result, those with good saving habits can quickly develop an entrepreneurial mindset and start making money (Bosumatari, 2014). Saving is thought to be an efficient way of accumulating funds. Therefore, a positive relationship between entrepreneurial development and saving habits develops (Erskine et al., 2006; Rikwentishe et al., 2015b).

Consequently, it is argued that savings can serve as a link between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intent. This is because financial literacy instills in people the necessary skills and perceptions of saving behavior, highlighting the importance of saving in individuals' financial stability and wellbeing, and making sound financial and business decisions. Furthermore, once an individual saves and collects the necessary funds, they can be used in a variety of entrepreneurial investments, such as meeting future challenges and creating new or expanding existing job opportunities (Okeke et al., 2015; Rikwentishe et al., 2015b; Supanantaroek et al., 2016). To conclude, it is argued that people with strong self-control and financial literacy are likelier to save, invest, and develop entrepreneurial intentions. As a result, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Saving behavior mediates the relationships between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention.

Hypothesized Model

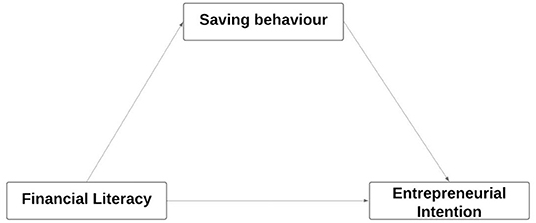

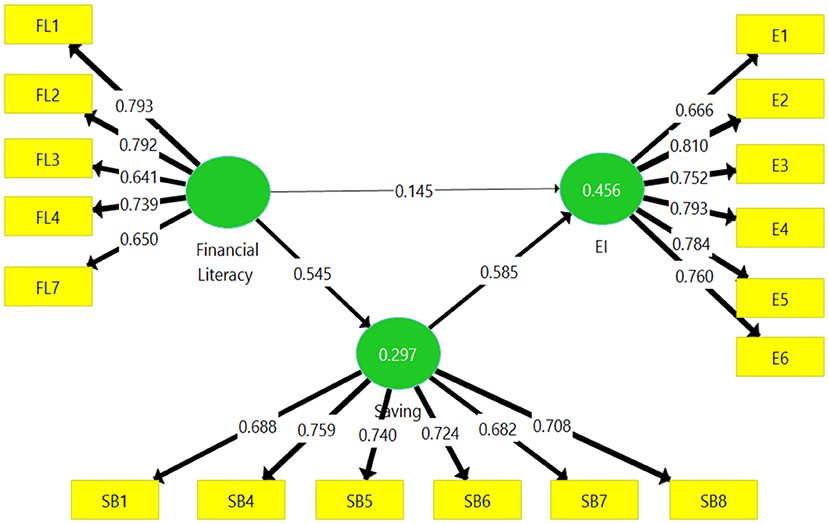

In this model, shown in Figure 1, financial literacy is an independent variable, entrepreneurial intention as a dependent variable, and saving behavior is a mediating variable that affects the relationship.

Research Methodology

Participants and Procedures

The quantitative study was conducted using a self-administered questionnaire sent to 270 potential entrepreneurs (qualified students) of the Applied College of Abqaiq, affiliated with King Faisal University in Saudi Arabia. The study's target respondents consist of applied college students pursuing two types of programmes: Human Resource Management and Medical Secretary. Compared to other students with bachelor's degrees and other degrees, these students have the most difficulty finding jobs after graduation. As a result, they are expected to establish small entrepreneurial businesses.

The study respondents were chosen because they had studied a subject called “financial management,” which provided them with the necessary information for financial planning. They also learned about various topics and received specific entrepreneurship training. The study included both male and female participants. Similar surveys from previous studies were used to develop the study's questionnaire. The survey questionnaire was distributed to respondents via an online link. However, before distribution, a pilot study with 15 respondents was conducted to assess the suitability of the measurers and the questionnaire. Because there were no issues with the questionnaire criteria, the questionnaire link was then sent to respondents and made available online for 1 month.

Respondents' Demographic Information

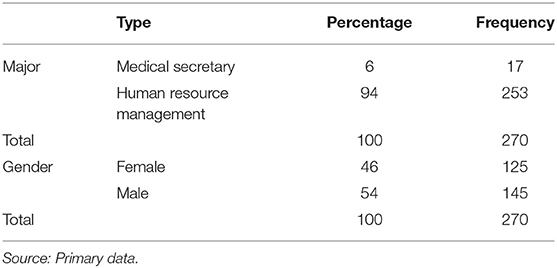

Table 1 summarizes the study's 270 respondents, of which 125 were females and 145 were males.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of respondents (94%) were from the human resource programme, while only 6% were from the medical secretary programme.

Sources of Measures Used in the Study

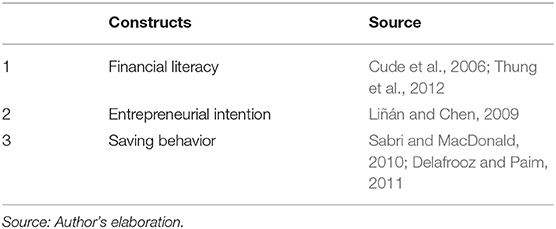

Table 2 shows the sources of measurements used in the study for financial literacy, entrepreneurial intentions, and saving behavior.

The measures of the study were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale, showing five in total agreement and one in complete disagreement.

Analysis of Data

Two steps were taken to evaluate the data and interpret the study's findings: (1) examine the measurement model, and (2) examine the structural model.

Measurement Model Analysis

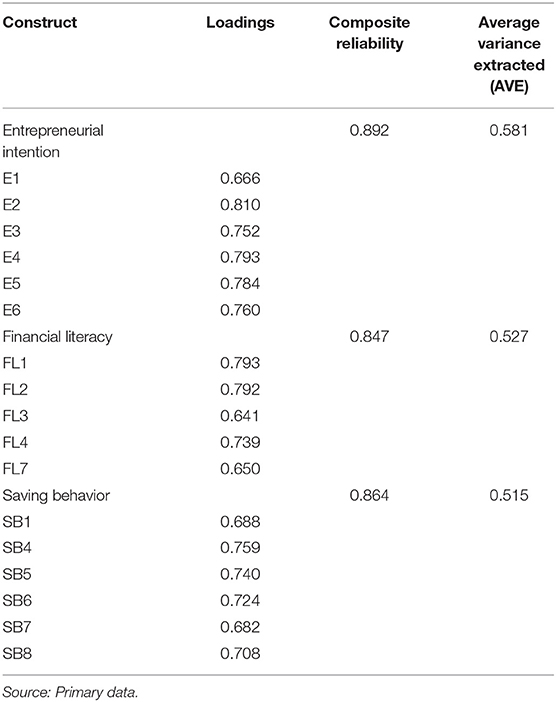

The purpose of the measurement model was to investigate the convergent validity and reliability of the study items and constructs. Thus, we began by assessing the so-called factor loading of all indicators. To ensure better reliability of the items used in the study, we recommended that the values of each indicator have a loading value of 0.70 or higher to ensure that the measured construct could explain 50% of the variance in the indicator used for analysis, revealing good reliability (Hair et al., 2019). However, it should be noted that even though there might be items below 0.70 loading values, their removal should be based on the condition that their removal will lead to more composite reliability. It should also be noted that items between 60 and 70% loadings were accepted in the exploratory research. Nevertheless, those items with loading values below 0.40 were removed (Hair et al., 2011, 2017).

In the second step of the measurement model, we evaluated the composite reliability used to assess the reliability of the internal consistency of the study constructs. The higher the composite reliability, the greater the reliability. Composite reliability should be between 60 and 70% (Hair et al., 2017). In the third step, we evaluated convergent validity, which assesses how one measure compares favorably to another measure of the same construct. In this case, we examined convergent validity using the extracted average variance (AVE). We used the recommended AVE of 50% or above, as it demonstrates the ability of the construct to explain more than 50% of the variance in the indicator (Hair et al., 2011, 2019).

Table 3 contains a description of the reliability and convergent validity. It shows that after removing the unwanted indicators, the results are in line with the recommended values, indicating the presence of adequate reliability and validity.

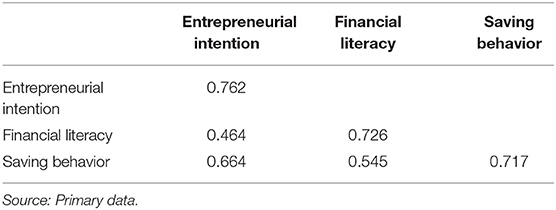

After completing step 3, we proceeded to step 4 of the measurement model, which determines the discriminant validity of the study constructs. This step illustrated how distinctive one construct was compared to the other constructs in the structural model (Hair et al., 2019).

To assess the discriminate validity, the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) was used. Table 4 shows how empirically distinct one construct in the structural model is from the others. It also assumes that the sum of all model construct variances cannot be greater than their individual variances. The HTMT values did not exceed 0.90, indicating that the study constructs had adequate discriminate validity (Henseler et al., 2015).

Analysis of the Structural Model

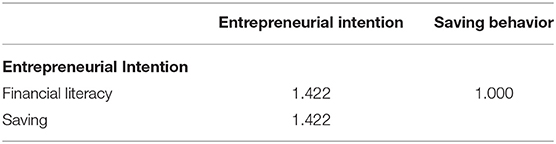

Collinearity Issue

After examining various tests in the measurement model, we evaluated the first step in the structural model. To ensure that the regression results were free of bias, we began by investigating the collinearity issue. As a result, we put the so-called variance inflation factor to the test (VIF). Thus, if the VIF value was >5, the study would be deemed to have collinearity issues.

Table 5 shows that all of the reported values are <3, indicating no collinearity.

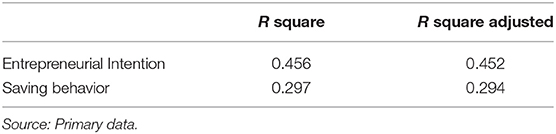

Explanatory Power

After examining the collinearity, we reviewed the coefficient of determination (R2), also known as the model's explanatory power. This test was carried out by calculating R2, the sum of the independent variables' effects on the dependent variables.

The model's explanatory power was deemed adequate because the R2 in Table 6 was more significant than 0.25. In other words, the model could account for ~45% of the variance in entrepreneurial intention. There is no rule of thumb for R2 because the outcome can vary based on the field of study and context.

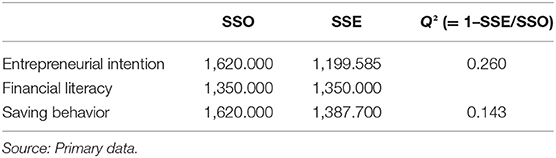

Construct Cross-Validated Redundancy

In Table 7, we see the constructs' cross-validated redundancy results. The 1-SSE/SSO values were higher than zero. Accordingly, the study's model had adequate predictive power.

Hypothesis Testing and Results

This section is important because it describes the bootstrapping procedure used to test the hypotheses with 500 resamples.

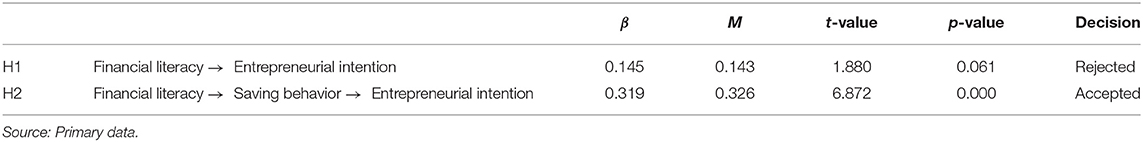

Table 8 shows the relationship between the variables in the study. Accordingly, hypothesis H1 is rejected because it demonstrates no direct positive relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.145, P > 0.05). However, when saving behavior was included as a mediator between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention, the findings revealed that saving behavior could fully mediate the previously mentioned relationships. As a result, H2 was accepted (β = 0.319, P < 0.05).

Path Coefficient Representations

Figure 2 demonstrates the path coefficients of the study's different constructs.

Discussion

This study investigated how the financial literacy of potential entrepreneurs (qualified students) influences their entrepreneurial behavior and business establishment decisions. The study also aimed to examine how potential entrepreneurs' saving behavior can mediate the relationship between their level of financial literacy and their entrepreneurial intention. As a result of investigating the hypothesized relationships of the study constructs, intriguing results were discovered. It was first reported that financial literacy among potential entrepreneurs does not always result in the development of entrepreneurial intentions.

This finding was surprising because it was revealed otherwise in most previous literature. However, this result could be attributed to the fact that, while those potential entrepreneurs may have the intention to start their small entrepreneurial firms, they may be hampered by other environmental factors, such as formal and informal institutions or a lack of necessary financial support, leading them to abandon the idea of starting a venture. This may confirm the need for financial support and the need to instill a saving culture in individuals' mindsets. This finding could also be attributed to the fact that those potential entrepreneurs have a limited understanding of financial literacy, which is insufficient to change their mindsets and direct their behavior toward business creation. This finding is similar to those of Ojogbo et al. (2022), who reported no connection and revealed a negative association between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention. Ojogbo is also not consistent with previous studies confirming a positive relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intent, such as Hilgert et al. (2003) and Levesque et al. (2009).

Hypothesis H2, which stated that saving behavior mediates the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention, was accepted. Acceptance was expected because as more people develop financial knowledge, literacy, or awareness, they become more knowledgeable about financial issues, save money, manage their personal finances wisely, and take advantage of the market's available finance and entrepreneurial opportunities (Delafrooz and Paim, 2011). They also recognize the significance of saving behavior as a source of finance for individuals. As a result, they begin saving and reinvesting in future investments and entrepreneurial firms (Arnida et al., 2015). Saving is considered vital because it connects individuals' financial literacy, entrepreneurial intent, and business creation. It also enables them to face future financial challenges, uncertainties and potential risks. Saving also allows them to reduce their reliance on external sources of finance, which are often inaccessible and expensive. This research supports the findings of previous studies (Hilgert et al., 2003; Sabri and MacDonald, 2010; Delafrooz and Paim, 2011; Thung et al., 2012; Arnida et al., 2015), which emphasize the importance of financial literacy and saving in the development of entrepreneurial intention and behavior.

Implications

The continuous rise in the unemployment rate and other socioeconomic problems in various parts of the world, particularly in countries with oil-based economies, has compelled them to devise new strategies for dealing with these challenges. Consequently, Saudi Arabia, as one of the oil-producing countries affected by these events, developed its own strategy, including the so-called Saudi Vision 2030, to address these challenges, particularly to support SMEs and entrepreneurship (Alshebami et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2021; Elnadi and Gheith, 2021). Accordingly, this article contributes new literature to the existing literature on the impact of financial literacy and saving behavior in supporting SMEs and potential entrepreneurs' entrepreneurial intentions. It also provides empirical evidence regarding the effects of financial literacy on entrepreneurial intention and the mediation effect of saving behavior on entrepreneurial intention among potential entrepreneurs.

Furthermore, the study emphasizes the need to broaden the study's scope and sample size to allow researchers to examine the impact of financial literacy and other financial concepts from various perspectives. The study also emphasizes the importance of improving financial literacy and instilling saving habits in potential entrepreneurs to maximize the benefits of their entrepreneurial firms' creation (Dunn and Holtz-Eakin, 2000; Kilara and Latortue, 2012; Rikwentishe et al., 2015a). It also highlights that good saving habits can be a good source of start-up capital (Dozie, 1995; Bosumatari, 2014).

The study recommends that policymakers, educational institutions, and other development programmes focus on developing the necessary financial literacy programmes and saving curricula and include them as an essential part of their university syllabus to maximize the benefits of potential entrepreneurs and direct them toward starting their small businesses. While universities and other educational institutions develop the necessary financial literacy programmes, banks and other financial institutions must work on creating different types of saving services to encourage individuals to save. Furthermore, financial institutions and banks should provide more support and financial grants to scholars to continue researching other aspects of financial literacy and investment awareness and their impact on the SME and entrepreneurship sectors. Finally, policymakers in Saudi Arabia must popularize the concept of financial awareness or literacy and direct it toward supporting the development of entrepreneurship.

Conclusions

The significance of instilling entrepreneurial intention and behavior in potential entrepreneurs necessitated identifying key factors that may contribute to the development of potential entrepreneurs' entrepreneurial behavior. As a result, we investigated how financial literacy and saving behavior can influence potential entrepreneurs' entrepreneurial intentions (qualified students). The study sought to examine the perceptions of 270 potential entrepreneurs at the applied college of Abqaiq, affiliated with King Faisal University, regarding financial literacy, saving behavior and entrepreneurial intention. The study found an interesting relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention and the ability of saving behavior to mediate the relationship between financial literacy and entrepreneurial intention in the study context. We also concluded that the greater individuals' financial literacy, the greater their potential savings. Furthermore, the more one saves, the more likely to engage in entrepreneurial behavior.

As a result, policymakers and the private sector must focus on and collaborate on increasing financial literacy and saving behavior among potential entrepreneurs. This behavior can be accomplished by growing educational programmes on financial literacy and developing more saving products and services to encourage potential entrepreneurs. The entrepreneurs, in turn, would become more involved in them and as a result, develop a propensity for business creation. Finally, even though this study contains some intriguing findings, it is essential to note that it has some limitations regarding its sample and the concepts used. Because of the small sample size, it is difficult to generalize the findings. Consequently, it is suggested that future studies include larger sample sizes, more concepts on the regression process, control variables, and broaden the context of the study by comparing other countries to Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by King Faisal University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Saudi Investment Bank Chair for Investment Awareness Studies, the Deanship of Scientific Research, the Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. 32].

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali, M., Ali, I., Badghish, S., and Soomro, Y. (2021). Determinants of financial empowerment among women in Saudi Arabia. Front. Psychol. 12, 747255. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.747255

Aljarodi, A. (2020). Female Entrepreneurial Activity in Saudi Arabia : An Empirical Study. (Ph.D. Thesis), Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, International Doctorate in Entrepreneurship and Management Bellaterra Cerdanyola Del Valles (Spain).

Alshebami, A., Aljubari, I., Alyoussef, I., and Raza, M. (2020). Entrepreneurial education as a predicator of community college of abqaiq students' entrepreneurial intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 10, 3605–3612. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2020.6.033

Alshebami, A., and Seraj, A. (2021). The antecedents of saving behavior and entrepreneurial intention of Saudi Arabia university students. Educ. Sci. Theory Practi. 21, 67–84. doi: 10.12738/jestp.2021.2.005

Alshebami, S. (2021). The influence of psychological capital on employees' innovative behavior: mediating role of employees' innovative intention and employees' job satisfaction. SAGE Open 11, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/21582440211040809

Arnida, S., Nadiah, M., Rozana, O., Naina, M., and Syazwani, N. (2015). Determinants of Savings Behaviour Among Muslims in Malaysia: an Empirical Investigation. Singapore: Springer Science+Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-429-0

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood, CO: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Bhatti, M., AlDoghan, M., Saat, S., Juhari, A., and Alshagawi, M. (2021). Entrepreneurial intentions among women: does entrepreneurial training and education matters? (Pre- and post-evaluation of psychological attributes and its effects on entrepreneurial intention). J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 28, 167–184. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-09-2019-0305

Bosumatari, D. (2014). Determinants of saving and investment behaviour of tea plantation workers: an empirical analysis of four tea gardens of udalguri district (Assam). PRAGATI : J. Indian Econ. 1, 144–164. doi: 10.17492/pragati.v1i1.2497

Browning, M., and Lusardi, A. (1996). Micro household saving: micro theoreies and micro facts. J. Econ. Lit. 34, 1797–1855.

Bullough, A., Renko, M., and Myatt, T. (2014). Danger zone entrepreneurs: the importance of resilience and self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 38, 473–499. doi: 10.1111/etap.12006

Cai, L., Murad, M., Ashraf, S. F., and Naz, S. (2021). Impact of dark tetrad personality traits on nascent entrepreneurial behavior: the mediating role of entrepreneurial intention. Front. Bus. Res. China 15, 1–19. doi: 10.1186/s11782-021-00103-y

Cheng, C. T., Tang, Y., and Buck, T. (2021). The interactive effect of cultural values and government regulations on firms' entrepreneurial orientation. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 29, 221–240. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-06-2021-0228

Cole, S., and Fernando, N. (2008). Assessing the Importance of Financial Literacy, Vol. 9. Mandaluyong: Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Cude, B., Lawrence, F., Lyons, A., Metzger, K., LeJeune, E., Marks, L., et al. (2006). “College students and financial literacy: what they know and what we need to learn,” in Eastern Family Economics and Resource Management Association, 102–109. Available online at: http://mrupured.myweb.uga.edu/conf/22.pdf

Delafrooz, N., and Paim, L. H. (2011). Determinants of saving behavior and financial problem among employees in Malaysia. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 5, 222–228. Available online at: http://ajbasweb.com/old/ajbas/2011/July-2011/222-228.pdf

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., and Hess, J. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. Washington, DC: World Bank, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29510

Dunn, T., and Holtz-Eakin, D. (2000). Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self-employment: evidence from intergenerational links. J. Labor Econ. 18, 282–305. doi: 10.1086/209959

Elnadi, M., and Gheith, M. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in higher education: evidence from Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 19, 100458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100458

Erskine, M., Kier, C., Leung, A., and Sproule, R. (2006). Peer crowds, work experience, and financial saving behaviour of young Canadians. J. Econ. Psychol. 27, 262–284. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2005.05.005

Evan, D., and Jovanovic, B. (1989). An estimated model of entrepreneurial choice under liquidity constraints. J. Polit. Econ. 97, 808–827.

Furnham, A., and Cheng, H. (2019). Factors influencing adult savings and investment: findings from a nationally representative sample. Pers. Individ. Diffe. 151, 109510. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109510

Gilenko, E., and Chernova, A. (2021). Saving behavior and financial literacy of russian high school students : an application of a copula-based bivariate probit-regression approach. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 127, 106–122. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106122

Glaser, M., and Walther, T. (2014). Run, Walk, or Buy? Financial Literacy, Dual-Process Theory, and Investment Behavior. The University of Innsbruck and Ulm. Available online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2167270

Hailesellasie, A., Abera, N., and Baye, G. (2013). Assessment of saving culture among households in Ethiopia. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 4, 1–8. Available online at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1031.88&rep=rep1&type=pdf#:~:text=64.1%25%20of%20the%20respondents%20fromprefer%20purchasing%20of%20physical%20assets

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hair, J. J., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd Edn. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hasler, A., and Lusardi, A. (2017). The Gender Gap in Financial Literacy: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center, The George Washington University School of Business. Available online at: https://gflec.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/The-Gender-Gap-in-Financial-Literacy-A-Global-Perspective-Report.pdf

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hilgert, M., Hogarth, J., and Beverly, S. (2003). Household financial management: the connection between knowledge and behavior. Fed. Res. Bull. 89, 309–322. Available online at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2003/0703lead.pdf

Hogarth, J. M., and Hilgert, M. A. (2002). “Financial knowledge, experience and learning preferences: preliminary results from a new survey on financial literacy,” in Consumer Interest Annual, Proceedings of the American Council on Consumer Interests 2002 Annual Conference, Vol. 48 (Los Angeles, CA), 1–7. Available online at: https://www.consumerinterests.org/assets/docs/CIA/CIA2002/hogarth-hilgert_financial%20knowledge.pdf

Jiatong, W., Murad, M., Bajun, F., Tufail, M. S., Mirza, F., and Rafiq, M. (2021). Impact of entrepreneurial education, mindset, and creativity on entrepreneurial intention: mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 12, 724440. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724440

Khan, A., and Alsharif, N. N. (2019). SMEs and Vision 2030, Jadwa Investment. Available online at: http://www.jadwa.com/en (accessed March 31, 2022).

Kilara, T., and Latortue, A. (2012). “Emerging perspectives on youth savings,” in Consultative Group to Assist the Poor. Available online at: https://www.cgap.org/sites/default/files/CGAP-Focus-Note-Emerging-Perspectives-on-Youth-Savings-Aug-2012.pdf (accessed March 31, 2022).

King Khaled Foundation (2018). Reaching the Less Fortunate: The Politics of Financial Inclusion in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. King Khaled Foundation. Available online at: https://www.kkf.org.sa/insights/

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., and van Oudheusden, P. (2015). Financial Literacy Around the World: Insights From The Standard and Poor's Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey. Washington, DC: The Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center. Available online at: https://gflec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Finlit_paper_16_F2_singles.pdf

Koh, H. C. (1996). Testing hypotheses of entrepreneurial characteristics a study of Hong Kong MBA students. J. Manag. Psychol. 11, 12–25.

Levesque, B., Godfrey, N., and Miller, M. (2009). The Case for Financial Literacy in Developing Countries: Promoting Access to Finance by Empowering Consumers. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank.

Li, C., Ashraf, S. F., Shahzad, F., Bashir, I., and Murad, M. (2020a). Influence of knowledge management practices on entrepreneurial and organizational performance : a mediated-moderation model. Front. Psychol. 11, 577106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577106

Li, C., Murad, M., Shahzad, F., Aamir, M., and Khan, S. (2020b). Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: role of entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 11, 1611. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01611

Li, R., and Qian, Y. (2020). Entrepreneurial participation and performance: the role of financial literacy. Manag. Decis. 58, 583–599. doi: 10.1108/MD-11-2018-1283

Liñán, F., and Chen, Y.-W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 33, 593–617. Available online at: http://institucional.us.es/vie/documentos/resultados/LinanChen2009.pdf

Lusardi, A., and Mitchell, O. S. (2011). Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing (No. NBER Working Papers 17078). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w17078/w17078.pdf

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., and Curto, V. (2009). Financial Literacy Among the Young: Evidence and Implications for Consumer Policy Consumers. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Retirement Research Center. Available online at: https://pensionresearchcouncil.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/BWP2009-01.pdf

Mitchell, O., and Lusardi, A. (2015). Financial literacy and economic outcomes: evidence and policy implications. J. Retire. 3, 107–114. doi: 10.3905/jor.2015.3.1.107

Mpaata, E., Koske, N., and Saina, E. (2021). Does self-control moderate financial literacy and savings behavior relationship? A case of micro and small enterprise owners. Curr. Psychol. 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02176-7

Murad, M., Li, C., Ashraf, S. F., and Arora, S. (2021). The influence of entrepreneurial passion in the relationship between creativity and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Glob. Bus. Competit. 16, 51–60. doi: 10.1007/s42943-021-00019-7

Nasip, S., Amirul, S. R., Sondoh, S. L. Jr., and Tanakinjal, G. H. (2017). Psychological characteristics and entrepreneurial intention a study among University students in North Borneo, Malaysia. Educ. Train. 59, 825–840. doi: 10.1108/ET-10-2015-0092

Ojogbo, L. U., Idemobi, E. I., Ngige, C. D., and Anamemena, J. C. (2022). Financial literacy and development of entrepreneurial intentions among graduates of selected tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Int. J. Res. Pub. Rev. 3, 1052–1061. Available online at: https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V3ISSUE1/IJRPR2442.pdf

Okeke, A., Nto, P., and Anayochukwu, J. (2015). Analysis of the factors influencing savings and investment behaviour among yam entrepreneurs in Benue State, Nigeria. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 7, 205–209. Available online at: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/EJBM/article/viewFile/26013/26491

Oseifuah, E. K. (2010). Financial literacy and youth entrepreneurship in South Africa. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 1, 164–182. doi: 10.1108/20400701011073473

Otto, A. M. C. (2009). The Economic Psychology of Adolescent Saving. Available online at: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/83873/OttoA.pdf (accessed March 31, 2022).

Philippas, N., and Avdoulas, C. (2019). Financial literacy and financial well-being among generation-Z university students: evidence from Greece. Eur. J. Fin. 26, 360–381. doi: 10.1080/1351847X.2019.1701512

Qader, A. A., Zhang, J., Ashraf, S. F., Syed, N., Omhand, K., and Nazir, M. (2022). Capabilities and opportunities: linking knowledge management practices of textile-based SMEs on sustainable entrepreneurship and organizational performance in China. Sustainability. 14, 1–26. doi: 10.3390/su14042219

Rafiq, M., and Muhammad, R. (2021). Impact of entrepreneurial education, mindset, and creativity on entrepreneurial intention: mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 12, 724440.

Rikwentishe, R., Musa Pulka, B., and Msheliza, S. K. (2015a). The effects of saving and saving habits on entrepreneurship development. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 7, 111–119. Available online at: www.iiste.org

Rikwentishe, R., Pulka, B. M., and Msheliza, S. K. (2015b). The effects of saving and saving habits on entrepreneurship development. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 7, 111–118. Available onlie at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.735.9741&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Sabri, M., and MacDonald, M. (2010). Savings behavior and financial problems among college students: the role of financial literacy in Malaysia. Crosscult. Commun. 6, 103–110. Available online at: http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/ccc/article/view/1468

Sabri, M., MacDonald, M., Masud, J., Paim, L., Hira, T. K., and Othman, M. (2008). Financial behavior and problems among college students in Malaysia: research and education implication. Consum. Inter. Annu. 54, 166–170.

Sedais, K. I., and Al Shahab, O. (2020). The Impact of Covid-19 on the Banking Sector of Saudi Arabia, 1–19. Available online at: https://home.kpmg/sa/en/home/insights/2020/04/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-the-banking-sector.html (accessed March 31, 2022).

Sohn, S.-H., Joo, S.-H., Grable, J. E., Lee, S., and Kim, M. (2012). Adolescents' financial literacy: the role of financial socialization agents, financial experiences, and money attitudes in shaping financial literacy among South Korean youth. J. Adolesc. 35, 969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.002

Stango, V., and Zinman, J. (2009). Exponential growth bias and household finance. J. Finance 64, 2807–2849. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01518.x

Stolper, O., and Walter, A. (2017). Financial literacy, financial advice, and financial behavior. J. Bus. Econ. 87, 581–643. doi: 10.1007/s11573-017-0853-9

Supanantaroek, S., Lensink, R., and Hansen, N. (2016). The impact of social and financial education on savings attitudes and behavior among primary school children in Uganda. Eval. Rev. 44, 511–541. doi: 10.1177/0193841X16665719

The General Authority for Statistics (2020). Saudi Youth in Numbers. The General Authority for Statistics. Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/saudi_youth_in_numbers_report_2020en.pdf

The World Bank (2016). Financial Education in the Arab World: Strategies, Implementation and Impact. Rabat: World Bank. Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/events/2016/10/20/financial-education-in-the-arab-world (acessed March 31, 2022).

Thung, C. M., Kai, C. Y., Nie, F. S., Chiun, L. W., and Tsen, T. C. (2012). Determinants of Saving Behaviour among the University Students in Malaysis. Universiti tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia. Available online at: http://eprints.utar.edu.my/607/1/AC-2011-0907445.pdf

Tshiaba, S. M., Wang, N., Ashraf, S. F., Nazir, M., and Syed, N. (2021). Measuring the Sustainable Entrepreneurial Performance of Textile-Based Small – Medium Enterprises : A Mediation—Moderation Model (Basel). Sustainability. 13, 11050. doi: 10.3390/su131911050

Keywords: awareness, SMEs, Saudi Arabia, entrepreneurship, entrepreneurs

Citation: Alshebami AS and Al Marri SH (2022) The Impact of Financial Literacy on Entrepreneurial Intention: The Mediating Role of Saving Behavior. Front. Psychol. 13:911605. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.911605

Received: 02 April 2022; Accepted: 10 May 2022;

Published: 10 June 2022.

Edited by:

Majid Murad, Jiangsu University, ChinaReviewed by:

Muhammad Sibt E. Ali, Zhengzhou University, ChinaMaria Safitri, Universitas Dian Nuswantoro, Indonesia

Sheikh Farhan Ashraf, Jiangsu University, China

Copyright © 2022 Alshebami and Al Marri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ali Saleh Alshebami, YWFsc2hlYmFtaUBrZnUuZWR1LnNh; Salem Handhal Al Marri, c2hhbG1hcnJpQGtmdS5lZHUuc2E=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Ali Saleh Alshebami

Ali Saleh Alshebami Salem Handhal Al Marri1,2,3*†

Salem Handhal Al Marri1,2,3*†