- 1Department of Management Sciences, Khwaja Fareed University of Engineering and Information Technology, Rahim Yar Khan, Pakistan

- 2Department of Management Sciences, National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 3Lyallpur Business School, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan

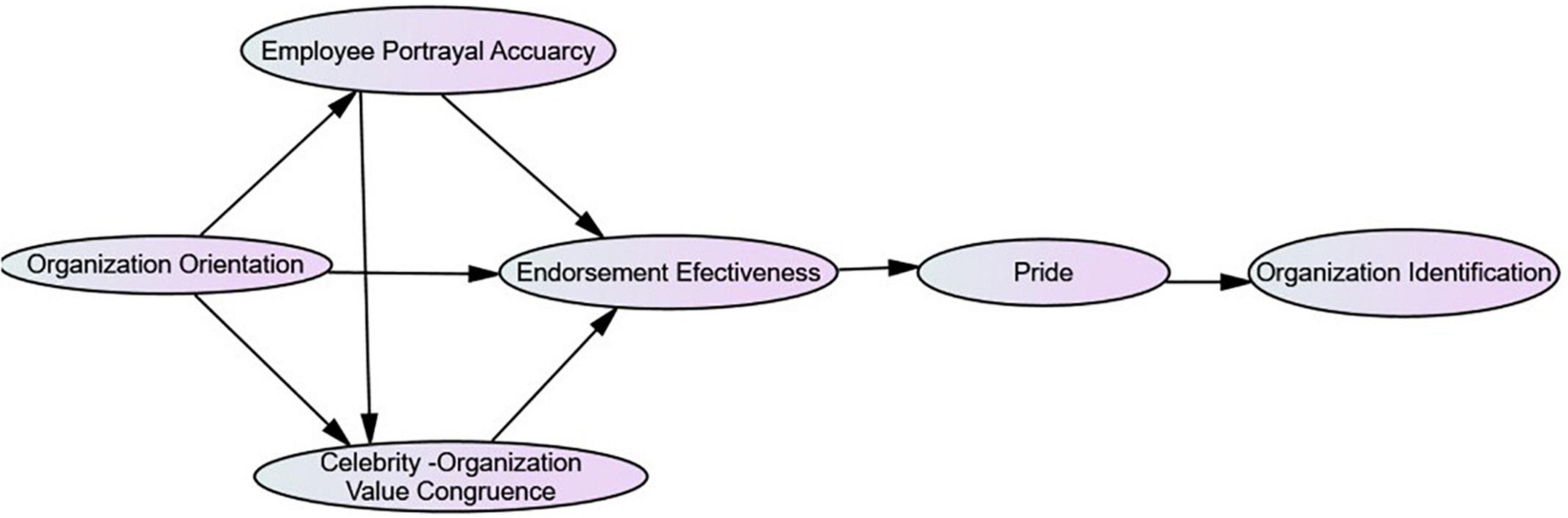

Celebrity endorsement has been used for decades to promote products to consumers. As employees are one of the primary stakeholders and are known as second consumers, their concerns about celebrity endorsement effectiveness and pride need attention for building their identification with an organization. This study investigated the internal branding process by examining employees’ brand orientation, celebrity-organization value congruence, and the accuracy of employee portrayal. Data are collected from a leading multinational bank in Pakistan through a structured questionnaire. The results of the study showed that when employees felt celebrity endorsement matched organizational values, the celebrity successfully portrayed actual corporate values. Thus, employees believed that endorsement effectively gained consumers’ attention and built a strong corporate image. The study affirmed that employees’ sense of pride toward their organization motivates them to identify with it. Furthermore, the results showed that value congruence mediates the relationship between brand orientation and endorsement effectiveness, while pride mediates the relationship between endorsement effectiveness and organization identification. Service organizations could use brand orientation to gain accurate employee portrayal that revives their pride and attachment with the organization and enhances corporate identification. The future directions and limitations are discussed.

Introduction

In marketing, celebrity endorsement is a very common phenomenon in the twenty-first century. Knoll and Matthes (2017) concluded that almost celebrities have appeared in every fifth advertisement. The study of Carlson et al. (2020) suggested that agencies have spent 10% of advertisement costs on promoting endorsements. In contrast, few multinational organizations have spent more than 25% of their promotion on endorsers. A celebrity is a personality who gains public appreciation and recognition from the name of the organization, whom they are endorsing for the purpose of promotion (McCracken, 1989).

Celebrities enjoy fame and popularity, influencing the endorsed brand’s image. The celebrity portrays a clear image of an organization to consumers. Brand marketing by a celebrity or a famous personality develops attractive appeal, gains more attention, and high recall (Davies and Slater, 2015). Companies use celebrities to create a distinguished position in the market and to build a positive brand image (Ranjbarian et al., 2010), which shapes a positive consumer attitude and a unique brand personality/organization (Thomson, 2006). Marketing managers and advertisers use endorsement strategies such as celebrity endorsement for their organizations because they understand that consumer attitude toward a celebrity also transfers to the organization (Choi and Rifon, 2012). Therefore, marketers and advertisers hire an appropriate celebrity because the endorsement by consumers’ accepted celebrity enhances consumers’ positive attitude (Surana, 2008). The work of Schimmelpfennig (2018) also concluded that positive association of celebrity-brand congruence with brand evaluation played a role in designing advocacy and engagement.

Organizational identification is considered a strategic asset for creating creditability among stakeholders, and it leads marketing managers to gain a competitive advantage by fabricating a dynamic corporate environment (Melewar, 2003). Organizational identification is the prime motivation for employees to understand better corporate goals, vision, and culture, which present pride, and image (Downey, 1987). An organization with good corporate identification attracts executives with exceptional skills that provide admirable financial outcomes (Melewar and Saunders, 1998). With a definite identification, it is easier to portray organizational capabilities, differentiation strategies, and product/service diversification (Lippincott and Margulies, 1988). Moreover, the consumer perspective presented that product quality, brand image, and loyalty are linked with organizational identification that portrays brand orientation for external and internal customers. Thus, organization identification is a step toward producing a corporate brand that brings a sense of community among stakeholders (Markwick and Fill, 1997).

Corporate marketing explains the coordination of a brand based on its organizational culture and knowledge (Balmer, 2013). It presents a unique strategic organizational approach (Illia and Balmer, 2012; Balmer, 2017) that constitutes identification-based corporate orientation. Corporate marketing describes an organizational structure that allows all stakeholders to exchange their values and beliefs mutually similar to the marketing orientation, which comprises internal/external communication mediums like TVCs, publicity, public relations, and endorsements (Balmer et al., 2020). Corporate branding is an effective tool for managers to build emotional ownership among stakeholders, especially by using celebrities as brand ambassadors/endorsers.

Employees of the organization are also part of that audience influenced by celebrities. Berry (1980) and Papasolomou and Vrontis (2006) highlighted that employees are internal customers, and their support is essential for successful marketing programs. Employees also interpret, judge, and react to the marketing communication strategies of their organization (Gilly and Wolfinbarger, 1998; Scott and Lane, 2000), which affects their satisfaction (Shostack, 1987) and supports them in identifying with their organization (Khan and Stanton, 2010; Farrelly et al., 2012; Hofer and Grohs, 2018). Employee pride is always a priority for reputable organizations.

Recent studies of organizational behavior suggested pride as an emerging area, and academic researchers investigated their relationships with the workplace (Ellington and Wilson, 2017; Kraemer et al., 2020). Various marketing techniques are used for internal marketing, which helps to shape behaviors for the achievement of organizational goals (Rafiq and Ahmed, 2000; Hartline and Bejou, 2004) and guide employees to live the brand image of their organization (Miles and Mangold, 2004). Ashforth and Mael (1989) and Dutton et al. (1994) studied the effects of new media advertising on employees’ attitudes, Celsi and Gilly (2010) studied the effects of advertising, and Hofer and Grohs (2018) studied the effects of sponsorship toward organization identification and performance outcomes.

Corporate marketing demands those marketing strategies that are customer-oriented, which deliver valuable identification of organization and employees in society. The study by Carlson et al. (2020) argued that unproductive endorsement attracts customers toward the product attachment rather than building customer association/engagement. However, customer-endorser affiliation built a sense of community for internal and external customers. In the service sector, the association of celebrity endorsement plays a central role in generating identification because “people” are one of the key promotional mix elements. The study proposed that optioning relevant endorsers could play a transforming role in building employee pride and organizational identification.

Moreover, the direct association of celebrity endorsers generates customer knowledge and recognition of its expertise and product-endorser fit. A competitive organization consists of attributes such as marketing strategy, corporate culture, and behavior, and these aspects build identity. Nowadays, corporate identity is getting attention as a strategic goal in disciples like marketing and behavioral sciences (Melewar, 2003). To experience consistency for a corporate brand, employee commitment and behavior indicate brand values (Lohndorf and Diamantopoulos, 2014; Piehler et al., 2016), pride, brand promise (Piha and Avlonitis, 2018), and desired level of brand identity (Harris and De Chernatony, 2001). Morhart et al. (2009) concluded that employees are vital for building organizational identity because any brand-branding intention needs all stakeholders to follow marketing mix strategies (Lohndorf and Diamantopoulos, 2014). While promoting product/service, frontline employees deliver the organizational promise that expresses their sense of belonging with the organization (Boukis et al., 2021), characterized as employee pride. Employee pride is considered a psychological tendency toward an organization when an employee believes that his/her performance exceeds expectations (Kraemer et al., 2020). The value of employee pride provides value-based appraisal and generates organizational identification (Thomas et al., 2018).

The study used stimulus–organism–response (SOR) theory to mark the research gap by investigating celebrity value congruence, employee pride, and organizational identification of employees. From an organizational perspective, assumptions of social identity theory (SIT) are employed to interpret the psychological mechanism of identifying an organization. This theory states that individuals see groups as a reference point for gathering/sharing information about others/themselves (Tyler et al., 1996). Thus, employees adopt the social status of their organization and present their pride (Tyler, 1999) by following corporate values/beliefs, such as advocating celebrity promotion/endorsement. The employees’ perspective suggested that an individual identification with the corporate world provides prestigious standings because being a part of that community brought pride and self-enhancement among stakeholders. Pratt (1998) focused on insights into social identification principles by investigating an individual’s relationship with his/her social group; in this case, it is brand orientation with employee identification.

Organizations benefit from encouraging identification among employees, as their identification ensures that employees will prefer their organizational interests (Cheney, 1983). Therefore, the growth of any organization is accredited to its in-depth orientation (Wright et al., 1995), and it might be linked with organizational commitment, competitive advantage, and overall organizational performance (Urde, 1994; Wong and Merrilees, 2007; Baumgarth and Schmidt, 2010). Moreover, it enhances employees’ identification and attachment with their organization (Foster et al., 2010).

Theoretical support and conceptual framework

The conceptual framework of this study is based on the cognitive psychological theory of SOR (Zimmerman, 2012). A stimulus is an object which induces an effect on an individual. Stimulus is the environmental cues that influence consumers’ feelings and can change a consumer’s overall behavior (Zimmerman, 2012). The SOR theory supports the effect of value-congruent endorsement on employees’ attitudes and behavior. The research framework hypothesizes that stimuli or environmental cues (celebrity-organization value congruence) affect the organism (employees’ emotional feelings), which produces effects (employees’ identification with their organization) (Rajaguru, 2014). Therefore, the study proposed that celebrity-organization value congruence leads to endorsement-linked pride, which enhances employees’ organization identification. Many studies have characterized different stimuli and organisms as a predictor of employee brand identification (Smidts et al., 2001; Mignonac et al., 2006; Bartels et al., 2007; Celsi and Gilly, 2010) based on the SOR model.

Based on organizational identification theory (Mael and Ashforth, 1992; Dutton et al., 1994), the study proposed that internal branding and employee orientation enhance employees’ identification with their organization. Internal branding processes aiming at increasing awareness and commitment of the employees toward their organization are essential to successfully implementing the organization’s policies (Foster et al., 2010). The growth of any organization is accredited to its thorough orientation (Wright et al., 1995), which might be linked with organizational commitment, competitive advantage, profitability, and overall organizational performance, and success (Urde, 1994), and employee identification and attachment with the organization (Baumgarth and Schmidt, 2010).

Internal marketing theories clearly state that internal relations and interactions are important for employees’ involvement, shaping their positive attitudes and motivating them to implement profitable corporate programs (Ahmed et al., 2003; Saleem and Iglesias, 2016). Brand-oriented culture and philosophy guide an organization toward corporate goals (Balmer and Balmer, 2013). Brand equity is believed to be created and protected through a brand-oriented mindset (M’zungu et al., 2010). Some studies have confirmed the role of brand orientation and internal branding on performance outcomes, but limited attempts have been made on their effects on employees’ behavior (Punjaisri and Wilson, 2007; De Chernatony et al., 2010).

Brand orientation facilitates long-term organizational survival. In such organizations, top management executives focus (Wong and Merrilees, 2005) on their brands and align organization strategies with brand strategies (Aaker, 1996), which result in higher brand performance (Gromark and Melin, 2011). Brand orientation is a system in which all the organization’s processes work together to create, develop, and protect an organization’s brand identity (Urde, 1999). Furthermore, it is an organizational culture that promotes the dominant role of a brand in an organization’s strategies and decisions (Wong and Merrilees, 2007; Baumgarth and Schmidt, 2010). It is an inside-out identity view that presents the brand as a part of an organization’s strategies and decisions (Urde et al., 2013).

Brand orientation acts as a mindset that contributes to organizational vision, mission, and values (Urde, 1999; Urde et al., 2013) and supports employees to live their brand (Ind, 2004), which enhances their brand identity and they grow as a strategic resource for an organization (Urde, 1999; De Chernatony et al., 2010; Wilden et al., 2010). Brand orientation facilitates organizational-wide commitment. Commitment and understanding of organizational values support employees to accept the external marketing communication, strengthening their existing beliefs and attitudes toward organizational values (Chakravarti et al., 1997). Hence, the employees who better understand their organizational values positively evaluate the celebrity endorser.

Many marketers and advertisers believe selecting the right celebrity is essential because consumers look for the fit between the celebrity and the organization/product (Choi and Rifon, 2012). A good congruence between the celebrity and organization/product effectively generates a positive endorsement/advertisement evaluation and increases the endorser’s believability (Davies and Slater, 2015). Previous studies found that employees expect value congruence between their organization and marketing communication (Gilly and Wolfinbarger, 1998; Celsi and Gilly, 2010). As members of an organization, employees have detailed knowledge and use it to assess the congruence between the celebrity’s and their organization’s values. Employees believe that as the celebrity is portraying the values of an organization, he/she should be matched with the organizational values (Choi and Rifon, 2012). Hence,

H1a: Brand orientation positively impacts employees’ perception of celebrity-organization value congruence.

Understanding their shared values within an organization helps employees assess the match between the celebrity portrayal values and the employees’ actual characteristics and behavior (Hogg and Turner, 1985). Tajfel and Turner (1982) revealed that people take self-categorization as a reference point to study the similarities between themselves and other members of a group. Therefore, employees evaluate the employee portrayal accuracy by endorser celebrity.

H1b: Brand orientation positively impacts employees’ perception of employee portrayal accuracy.

The celebrity-brand/product congruence plays an important role in deciding the effectiveness of a celebrity endorsement campaign (Hoogland et al., 2007). The celebrity casts a positive image on consumers, making endorsement more persuasive, thus increasing the organization’s attractiveness. A strong link between the product/brand and celebrity is effective for attaining positive evaluations toward advertisement, which ultimately influences the endorser’s believability (i.e., he will successfully portray the actual organization’s and employee’s value) and advertisement effectiveness (Davies and Slater, 2015). Literature suggests that value-congruent advertisement develops and enhances motivational characteristics toward portrayed values (Verplanken and Holland, 2002), which ultimately motivates employees to support the image of their organization portrayed by the endorser. The literature also supports that individuals who perceive similarities between external communication and existing beliefs and values show more assimilation to organizational communication (Sherif et al., 1965; Meyers and Sternthal, 1993).

H2: (a) Celebrity-organization value congruence and (b) employee portrayal accuracy positively impact the perception of endorsement effectiveness.

Endorser value congruence is the likeness of an employee’s values and those values portrayed by the celebrity. Endorser gives statements about organizational values, persuading employees to invoke their values and compare them to celebrity portrayed values.

H3: Celebrity-organization value congruence positively impacts employee portrayal accuracy.

Organizational behavior scholars admit the influence of external organizational images on employees’ attitudes (Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Dutton et al., 1994). When employees feel that the endorsement has effectively gained consumer attention and positively influenced the organization’s image, they “bask in the reflected glory” of the success of their organization (Cialdini et al., 1976). So we propose that:

H4: Celebrity Endorsement effectiveness positively influences employee’s pride.

Michie (2009) suggested that pride promotes behaviors that comply with an organization’s social norms. It encourages employees to identify strongly with their employer as they feel honored to be linked with an organization that is publically appreciated (Dutton et al., 1994). The brand-equity relationship has been found important for gaining a consuming response and emphasizing their role in celebrity endorsement (Albert et al., 2017). The positive impression of a celebrity using a service/product is transferred to employees/customers, who also adopt the usage pattern of their beloved celebrity to build an endorser-brand relationship (Carlson et al., 2020). In consumer studies, consumer-endorser identification has been achieved through the effectiveness of the celebrity identification process (Kamins et al., 1989), which means that recognizable celebrities impact organization identification process. Similarly, SIT approach states that employees use the social status of their organization to guide them in estimating their self-worth (Tyler, 1999). Thus, individuals try to identify with organizations, which have prestigious standings, because membership of a prestigious organization increases their self-esteem and fulfills the need of self-enhancement (Figure 1).

H5: Employee pride positively influences employee organizational identification.

Participants and procedures

To collect data from Habib Bank Limited (a leading commercial bank in Pakistan), we contacted the headquarters of HBL to request their support in data collection from their employees. Habib Bank Limited is a commercial bank in Pakistan with 1,650 branches all over Pakistan. Data were collected from 150 employees from HBL headquarters (Ndubisi et al., 2014). The sample-to-item ratio is generally recommended for exploratory factor analysis, which uses the number of items to decide the sample size in a study. The ratio between the item and the sample size should not be less than 5–1 (Gorsuch, 1983). Hair et al. (2018) suggested a sample-to-variable ratio to decide on sample size in a study. It is suggested that the minimum observation-to-variable ratio should be 5:1, but ratios of 15:1 or 20:1 are preferred.

The results of the demographics showed that 73% of respondents were male. More than 59% of the respondents were under the age of 40, showing that most of the employees are young and have been working with the organization for more than 10 years. An invitation (through email) to an online survey was sent to different employees working at the headquarters of HBL. Once they agreed to fill out the survey, the questionnaire was shared with them. The participants first responded to the items of brand orientation. After watching the HBL endorsement advertisement by famous cricketer Shaheen Shah Afridi, they evaluated celebrity-organization value congruence, employee portrayal accuracy, endorsement effectiveness, pride, and organization identification, which they feel resulted from watching the endorsement advertisement.

Measures

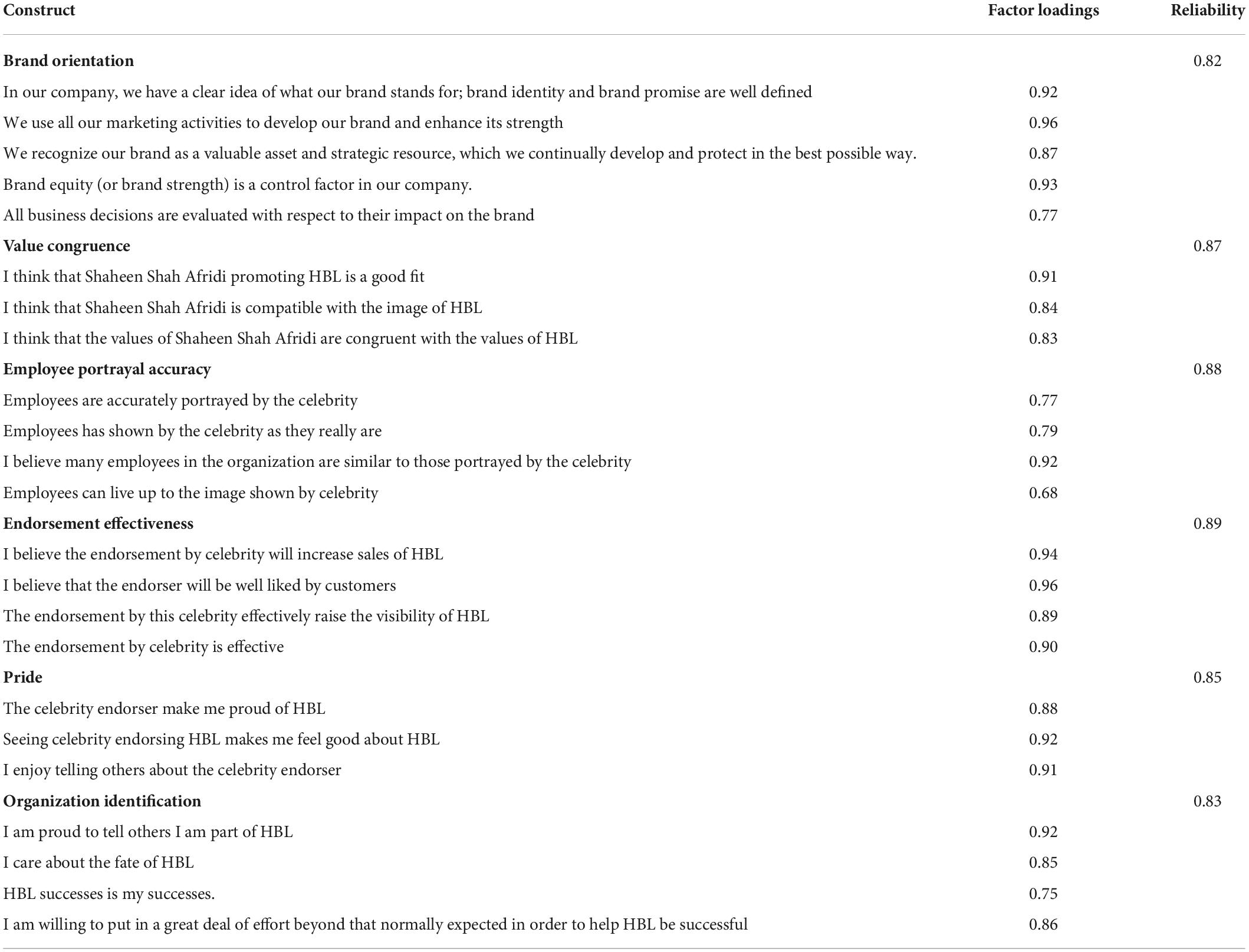

The constructs used in the study are accounted as “situated” variables because their responses were obtained as a reaction to the cue, an endorsement advertisement in our study that triggered temporary “situated” emotions such as pride and organization identification. The construct “brand orientation” was assessed on five items adopted from the study of Baumgarth and Schmidt (2010). “Value congruence” was assessed on three items adapted from Choi and Rifon (2012). Similarly, “pride” was assessed on three items, while “employee portrayal accuracy,” “endorsement effectiveness, and organization identification” were assessed on four items/each adopted from Celsi and Gilly (2010). The adopted items are mentioned in Table 1. After responding to questions related to the constructs, respondents answered the questions, including participants’ demographic information, such as gender, age, and years of experience in the organization. The study employed structural equation modeling (SEM) for data analysis. SEM is a multivariate technique used to evaluate multivariate causal relationships among variables. SEM is a multivariate statistical tool used to analyze structural relationships and structural links between latent and measured variables.

Results

The study has used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to estimate the discriminant validity, convergent, and reliability of the research model. AMOS was used to estimate the maximum likelihood of the measurement model. The model showed acceptable fit indices: χ2 = 257.012 with 1.147 CMIN/DF. The values of TLI, CFI, IFI, RFI, and NFI lie between 0.91 and 0.97, and the value of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.04. The GFI, CFI, and AGFI values are above 0.90 in the measurement model, indicating model fitness (Browne and Cudeck, 1993). Goodness-of-fit indices showed that the data fit thus supports construct validity. CFA was used to estimate the convergent validity of the constructs (Churchill, 1979). Convergent validity is supposed to occur if the pattern coefficient of the indicator exceeds 0.50 and the overall model has acceptable fit indices (Bagozzi et al., 1991).

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient value was used to estimate the internal consistency, and all the values of Cronbach’s alpha were found to be greater than the proposed threshold point of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). The Cronbach’s alpha value for construct brand orientation was measured at about 0.82, celebrity-organization value congruence was 0.87, employee portrayal accuracy was 0.88, endorsement effectiveness was 0.89, pride was 0.85, and organization identification was 0.83. These are significantly higher than the cutoff point of 0.70, confirming the constructs’ reliability (Nunnally, 1978; see Table 1). Factor loadings were found significant at the 0.01 level, and loadings above 0.40 were retained for analysis (see Table 1).

The average variance extracted (AVE) was estimated to study the discriminant validity. As Fornell and Larcker (1981) suggested, discriminant validity is supposed to occur if the AVE of a construct is greater than the correlation value with other constructs. All the AVEs values are larger than the threshold level of 0.50. Discriminant validity has been confirmed by following Fornell–Larcker’s criterion that all the square roots of AVEs are greater than their respective correlation values (Hew and Sharifah, 2017; see Table 2).

The results showed a significant relationship between brand orientation and organization-celebrity value congruence, hence supporting H1a (β = 0.56, p < 0.05). The relationship between brand orientation and employee portrayal accuracy is also significant, which supports H1b (β = 0.58, p < 0.05). Hence, the study supports the idea that brand orientation shapes employees attitude toward organization policies and decisions. Brand orientation also indirectly affects endorsement effectiveness (β = 0.05). Brand orientation does not directly affect endorsement effectiveness, so organization-celebrity value congruence was found to mediate the relationship between brand orientation and endorsement effectiveness. The results further showed a significant relationship of organization-celebrity value congruence with endorsement effectiveness and with employee portrayal accuracy, hence supporting H2a (β = 0.32, p < 0.5) and H3 (β = 0.42, p < 0.5), while employee portrayal accuracy was found to be insignificant with endorsement effectiveness, rejecting H2b. However, employee portrayal accuracy partially mediates the relationship between organization-celebrity value congruence and endorsement effectiveness. Endorsement effectiveness significantly correlates with pride (β = 0.76, p < 0.001) and supports H4. The relationship between pride and organization identification is also significant, supporting H5 (β = 0.37, p < 0.001). The relationship between endorsement effectiveness and organization identification is fully mediated by pride, as there was no direct effect of endorsement effectiveness on organization identification. Hence, the study supports the idea that pride associated with an organization’s activities and policies could lead to employees’ identification with the organization.

Discussion

The goal was to investigate whether brand orientation enhances employees’ organization identification or not. The study supports that internal branding influences employees’ organization identification. Thus, brand orientation encourages supportive organizational behaviors that motivate employees in the workplace. The study provides empirical evidence of the proposed association between brand orientation and employees’ identification with their organization, hence confirming previous literature on the consequences of internal branding (Ahmed and Rafiq, 1999; Punjaisri et al., 2008; Hirvonen et al., 2013; Biedenbach and Manzhynski, 2016). Brand orientation is an organizational culture that promotes the dominant role of a brand in an organization’s strategies and decisions (Wong and Merrilees, 2007; Baumgarth and Schmidt, 2010). The results showed that brand orientation could help employees to positively associate with organizations’ actions and take decisions accordingly, which is in line with the conclusion provided by M’zungu et al. (2010) and Balmer and Balmer (2013). Therefore, it encourages employees to associate with organizations’ celebrity endorsers.

The study confirmed that brand orientation positively impacts employees’ perceptions of employee portrayal accuracy and organization-celebrity value congruence, which is in line with the results of Matanda and Ndubisi (2013), who confirmed the impact of internal customer orientation on person-organization fit. Furthermore, the study also supported the findings of prior research stating that organizational competencies can promote employees’ commitment (Ahmed et al., 2003) because brand orientation shares a strong covenant relation with its stakeholders (including employees) (Balmer, 1998, 2001; Balmer and Gray, 2003). It promotes a culture of shared beliefs, behaviors, and expectations (Chatman and O’Reilly, 2016), shaping employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Baumgarth and Schmidt, 2010) toward celebrity endorsers and promoting organizational acceptability’ values portrayed by the celebrity.

Brand orientation promotes brand-supportive behavior that ensures that employees shape their behavior in correspondence with the brand identity and its values (Baumgarth and Schmidt, 2010). When employees come across a brand image of their organization, they get motivated to play their role as a stakeholder and attempt to relate it to their own identity (Gregory, 2007). Therefore, the employees who work with brand-oriented organizations feel a fit between celebrity-organization values.

Moreover, employees’ perception of celebrity-organization values congruence enhances the perception of endorsement effectiveness. These results are in line with the finding of Celsi and Gilly (2010) and Choi and Rifon (2012), who supported that selection of a favorable celebrity is essential because consumers look for the fit between the celebrity and the organization/product (Davies and Slater, 2015). Therefore, the study concluded that good congruence between the celebrity and organization/product effectively generates positive endorsement/advertisement evaluation and increases endorsers’ believability. The work of Meyers and Sternthal (1993) also suggested that employees who perceive similarities between external communication and existing beliefs and values show more attachment and advocate unique organization identification. However, this study does not support the role of employee portrayal accuracy in endorsement effectiveness, which is not in line with the previous literature (Celsi and Gilly, 2010) because employees perceive that puffery is part of an advertisement and integrated marketing communication (IMC) is designed for customers (James and Alman, 1996; Gilly and Wolfinbarger, 1998). From the employee perspective, employees’ portrayal accuracy has no impact on endorsement effectiveness, as they understand organizational culture and philosophy.

The cognitive theory of emotion proposes that emotions are developed in response to an activity (effective endorsement) which is judged to its effects on one’s wellbeing (such as organization success) (Michie, 2009). The results showed that effective endorsement brought employee pride, which is in line with the findings of Celsi and Gilly (2010). The effective endorsement gives a sense of pride to employees as it successfully promotes a positive image of the organization among consumers and society because of its position in society (Simon, 1995). Ashforth (2011) revealed that external organizational images influence the behavior of employees. So, when employees come across an image of their organization, they get motivated to play their role as a stakeholder and strive to relate it with their own identity (Scott and Lane, 2000) because they asses their self-worth based on the social standing of their organization (Tyler, 1999).

The study supported that the pride associated with the endorsement-linked recognition of their organization can help employees to strongly identify with their organization, which is in line with the findings of previous studies (Smidts et al., 2001; Fuller et al., 2006; Bartels et al., 2007; Celsi and Gilly, 2010; Khan et al., 2013). The employee perspective of SIT states that employees use the social status of their organization to guide them in estimating their self-worth (Tyler, 1999). Thus, individuals try to identify with organizations with prestigious standings because membership in a prestigious organization increases their self-esteem and fulfills the need for self-enhancement.

Hence, the study proved that brand orientation develops employees’ attitudes toward celebrity endorsement. Internal marketing theories state that internal association and interactions are important for employees’ involvement, shaping their positive attitudes and motivating them to implement profitable corporate programs (Saleem and Iglesias, 2016). By developing the employees’ attitude toward the celebrity endorser and his/her effectiveness, the employer could increase their identification with their organization. Furthermore, marketers and advertisers need to understand the importance of brand orientation on employees’ organization supportive behaviors toward organizations’ programs and policies, especially policies related to external marketing communication. The corporate internal communication process needs to be planned to ensure the product/service knowledge is constant and focuses on promise accuracy. The relevance of marketing strategies for employees with corporate values could strengthen their organizational identification.

Conclusion

Employees are considered as one of the primary stakeholders, so their concerns toward the celebrity endorser should be examined while planning IMC techniques. Employees have extensive knowledge of their organization and use it while evaluating the effectiveness of celebrity endorsers. Therefore, marketers and advertisers should hire only celebrities congruent with organizational values. The celebrities should understand that they need to portray only the actual values of the employees and organization.

This research studied the effect of celebrity value congruence and employee portrayal accuracy on employees’ attitudes toward endorsement effectiveness. However, there is a need to study more about the employees’ attitudes toward celebrity endorsers. First, employees’ general and specific attitudes toward celebrities should be studied to understand how employees’ attitudes toward a celebrity could facilitate them to identify with the organization and its endorsement campaign. Second, the effect of other organizational factors, including human resources practices, working environment, and methods of service provisions, could be studied to evaluate employees’ reactions toward celebrity endorse. The internal communication process should be planned to ensure the provision of constant and detailed information to the employees of an organization. Also, the relevance of marketing activities with employees and organization values can strengthen their identification with their organization, enhance their commitment, and motivate them to adopt more supportive behavior. The study recommends that advertisers and marketers hire a celebrity endorser that matches the organization’s values so that employees may relate to it. Marketers must motivate committed organization followers to enhance their beliefs about the organizational policies. Employees’ internal communication should support positive and strong beliefs about the organization’s marketing initiatives.

As the employees were exposed to actual celebrity endorsers and endorsement advertisements of the organization, we might have missed the effects of controlled experimental research, which could control any bias toward celebrity/endorsement advertisement. The study evaluates the effect of employees’ attitudes toward celebrity endorsers on their identification with their organization; future research should be conducted to study the effects on different performance outcomes such as employee customer focus. Another limitation of this study is the limited sample size that might not represent the population, so further studies with larger sample sizes might be conducted to have a more accurate representation. Future research could also use multiple-level data from consumers and employees to analyze the impact of endorser effectiveness and identification.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmed, P. K., and Rafiq, M. (1999). “The role of internal marketing in the implementation of marketing strategies,” in Internes marketing, (Wiesbaden: Gabler Verlag), 469–492. doi: 10.1007/978-3-663-05973-8_20

Ahmed, P. K., Rafiq, M., and Saad, N. M. (2003). Internal marketing and the mediating role of organizational competencies. Eur. J. Mark. 37, 1221–1241. doi: 10.1108/03090560310486960

Albert, N., Ambroise, L., and Valette-Florence, P. (2017). Consumer, brand, celebrity: Which congruency produces effective celebrity endorsements? J. Bus. Res. 81, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.08.002

Ashforth, B. E., and Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manage. Rev. 14:20. doi: 10.2307/258189

Ashforth, E. (2011). Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manage. 14, 20–39. doi: 10.5465/amr.1989.4278999

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., and Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Admin. Sci. Q. 36, 421–458. doi: 10.2307/2393203

Balmer, J. M. T. (1998). Corporate identity and the advent of corporate marketing. J. Market. Manage. 14, 963–996. doi: 10.1362/026725798784867536

Balmer, J. M. T. (2001). Corporate identity, corporate branding and corporate marketing–seeing through the fog. Eur. J. Market. 35, 248–291. doi: 10.1108/03090560110694763

Balmer, J. M. T. (2013). Corporate brand orientation: What is it? What of it? J. Brand Manage. 20, 723–741. doi: 10.1057/bm.2013.15

Balmer, J. M. T. (2017). Advances in corporate brand, corporate heritage, corporate identity, and corporate marketing scholarship. Eur. J. Market. 51, 1462–1414. doi: 10.1108/EJM-07-2017-0447

Balmer, J. M. T., and Gray, E. R. (2003). Corporate brands: What are they? What of them? Eur. J. Market. 37, 972–997. doi: 10.1108/03090560310477627

Balmer, J. M. T., Lin, Z., Chen, W., and He, X. (2020). The role of corporate brand image for B2B relationships of logistics service providers in China. J. Bus. Res. 117, 850–861. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.043

Balmer, J., and Balmer, J. M. T. (2013). Corporate heritage, corporate heritage marketing, and total corporate heritage communications: What are they? What of them? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 18, 290–326. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-05-2013-0031

Bartels, J., Pruyn, A., De Jong, M., and Joustra, I. (2007). Multiple organizational identification levels and the impact of perceived external prestige and communication climate. J. Organ. Behav. 28, 173–190. doi: 10.1002/job.420

Baumgarth, C., and Schmidt, M. (2010). How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically-tested model of ‘internal brand equity’ in a business-to-business setting. Ind. Market. Manage. 15, 387–340. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.02.022

Biedenbach, G., and Manzhynski, S. (2016). Internal branding and sustainability: Investigating perceptions of employees. J. Prod. Brand Manage. 25, 296–306. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-06-2015-0913

Boukis, A., Punjaisri, K., Balmer, J. M. T., Kaminakis, K., and Papastathopoulos, A. (2021). Unveiling frontline employees’ brand construal types during corporate brand promise delivery: A multi-study analysis. J. Bus. Res. 131, 673–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.068

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods and Res. 21, 230–258. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002005

Carlson, B. D., Donavan, D. T., Deitz, G. D., Bauer, B. C., and Lala, V. (2020). A customer-focused approach to improve celebrity endorser effectiveness. J. Bus. Res. 109, 221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.048

Celsi, M. W., and Gilly, M. C. (2010). Employees as internal audience: How advertising affects employees’ customer focus. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 38, 520–529. doi: 10.1007/s11747-009-0173-x

Chakravarti, D., Eagly, A. H., and Chaiken, S. (1997). The psychology of attitudes. J. Market. Res. 34:298. doi: 10.2307/3151869

Chatman, J. A., and O’Reilly, C. A. (2016). Paradigm lost: Reinvigorating the study of organizational culture. Res. Organ. Behav. 36, 199–224. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.004

Cheney, G. (1983). The rhetoric of identification and the study of organizational communication. Q. J. Speech 69, 143–158. doi: 10.1080/00335638309383643

Choi, S. M., and Rifon, N. J. (2012). It is a match: The impact of congruence between celebrity image and consumer ideal self on endorsement effectiveness. Psychol. Market. 29, 639–650. doi: 10.1002/mar.20550

Churchill, G. J. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measure of marketing constructs. J. Market. Res. 16, 64–73. doi: 10.1177/002224377901600110

Cialdini, R., Borden, R., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S. W., and Sloan, L. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 34, 366–375. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.34.3.366

Davies, F., and Slater, S. (2015). Unpacking celebrity brands through unpaid market communications. J. Market. Manage. 31, 665–684. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2014.1000941

De Chernatony, L., McDonald, M., and Wallace, E. (2010). Creating powerful brands, 4th Edn. Milton Park: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/978185617850

Downey, S. M. (1987). The relationship between corporate culture and corporate identity. Public Relat. Q. 31, 7–12.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., and Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Admin. Sci. Q. 39:239. doi: 10.2307/2393235

Ellington, J. K., and Wilson, M. A. (2017). The performance appraisal milieu: A multilevel analysis of context effects in performance ratings. J. Bus. Psychol. 32, 87–100. doi: 10.1007/s10869-016-9437-x

Farrelly, F., Greyser, S., and Rogan, M. (2012). Sponsorship linked internal marketing (SLIM): A strategic platform for employee engagement and business performance. J. Sport Manage. 26, 506–520. doi: 10.1123/jsm.26.6.506

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Foster, C., Punjaisri, K., and Cheng, R. (2010). Exploring the relationship between corporate, internal and employer branding. J. Prod. Brand Manage. 19, 401–409. doi: 10.1108/10610421011085712

Fuller, J. B., Hester, K., Barnett, T., Frey, L., Relyea, C., and Beu, D. (2006). Perceived external prestige and internal respect: New insights into the organizational identification process. Hum. Relat. 59, 815–846. doi: 10.1177/0018726706067148

Gilly, M. C., and Wolfinbarger, M. (1998). Advertising’s internal audience. J. Market. 62, 69–88. doi: 10.1177/002224299806200107

Gregory, A. (2007). Involving stakeholders in developing corporate brands: The communication dimension. J. Market. Manage. 23, 59–73. doi: 10.1362/026725707x178558

Gromark, J., and Melin, F. (2011). The underlying dimensions of brand orientation and its impact on financial performance. J. Brand Manage. 18, 394–410. doi: 10.1057/bm.2010.52

Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., and Black, W. C. (2018). Multivariate data analysis. red. Farmington Hills, MI: Cengage Learning EMEA.

Harris, F., and De Chernatony, L. (2001). Corporate branding and corporate brand performance. Eur. J. Market. 5, 441–456. doi: 10.1108/03090560110382101

Hartline, M. D., and Bejou, D. (2004). Internal relationship management: Linking human resources to marketing performance, 1st Edn. Milton Park: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9780203050552

Hew, T. S., and Sharifah, S. L. (2017). Applying channel expansion and self-determination theory in predicting use behaviour of cloud-based VLE. Behav. Inf. Technol. 36, 875–896. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2017.1307450

Hirvonen, S., Laukkanen, T., and Reijonen, H. (2013). No TitleThe brand orientation-performance relationship: An examination of moderation effects. J. Brand Manage. 20:623. doi: 10.1057/bm.2013.4

Hofer, K. M., and Grohs, R. (2018). Sponsorship as an internal branding tool and its effects on employees’ identification with the brand. J. Brand Manage. 25, 266–275. doi: 10.1057/s41262-018-0098-0

Hogg, M. A., and Turner, J. C. (1985). Interpersonal attraction, social identification and psychological group formation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 15, 51–66. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420150105

Hoogland, C. T., de Boer, J., and Boersema, J. J. (2007). Food and sustainability: Do consumers recognize, understand and value on-package information on production standards? Appetite 49, 47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.11.009

Ind, N. (2004). Living the brand: How to transform every member of your organization into a brand ambassador. London: Kogan Page.

James, E. L., and Alman, K. C. (1996). Consumer expectations of the information content in advertising. Int. J. Adv. 15, 75–88. doi: 10.1080/02650487.1996.11104635

Kamins, M. A., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., and Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: The impact of advertising effectiveness and credibility. J. Adv. 18, 4–10. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1989.10673146

Khan, A. M., and Stanton, J. (2010). A model of sponsorship effects on the sponsor’s employees. J. Promot. Manage. 16, 188–200. doi: 10.1080/10496490903574831

Khan, A., Stanton, J., and Rahman, S. (2013). Employees’ attitudes towards the sponsorship activity of their employer and links to their organisational citizenship behaviours. Int. J. Sports Market. Sponsorship 14, 20–41. doi: 10.1108/ijsms-14-04-2013-b003

Knoll, J., and Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: A meta- analysis. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 45, 55–75. doi: 10.1007/s11747-016-0503-8

Kraemer, T., Weiger, W. H., Gouthier, M. H., and Hammerschmidt, M. (2020). Toward a theory of spirals: The dynamic relationship between organizational pride and customer-oriented behavior. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 48, 1095–1115. doi: 10.1007/s11747-019-00715-0

Lippincott, A., and Margulies, W. (1988). America’s global identity crisis 2: Japan and Europe move ahead. New York, NY: Lippincott and Margulies Inc.

Illia, L., and Balmer, J. M. T. (2012). Corporate communication and corporate marketing: Their nature, histories, differences and similarities. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 17, 415–433. doi: 10.1108/13563281211274121

Lohndorf, B., and Diamantopoulos, A. (2014). Internal branding: Social identity and social exchange perspectives on turning employees into brand champions. J. Serv. Res. 17, 310–325. doi: 10.1177/1094670514522098

Mael, F., and Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 13, 103–112. doi: 10.1002/job.4030130202

Markwick, N., and Fill, C. (1997). Towards a framework for managing corporate identity. Eur. J. Market. 31, 396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.11.002

Matanda, M. J., and Ndubisi, N. O. (2013). Internal marketing, internal branding, and organisational outcomes: The moderating role of perceived goal congruence. J. Market. Manage. 29, 1030–1055. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2013.800902

McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. J. Consum. Res. 16, 315–349. doi: 10.1086/209217

Melewar, T. C. (2003). Determinants of the corporate identity construct: A review of the literature. J. Market. Commun. 9, 195–220. doi: 10.1080/1352726032000119161

Melewar, T. C., and Saunders, J. (1998). Global corporate visual identity systems: Standardisation, control and benefits. Int. Market. Rev. 15, 291–308. doi: 10.1108/02651339810227560

Meyers, J., and Sternthal, B. (1993). A two-factor explanation of assimilation and contrast effects. J. Market. Res. 30, 359–368. doi: 10.1177/002224379303000307

Michie, S. (2009). Pride and gratitude: How positive emotions influence the prosocial behaviors of organizational leaders. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 15, 393–403. doi: 10.1177/1548051809333338

Mignonac, K., Herrbach, O., and Guerrero, S. (2006). The interactive effects of perceived external prestige and need for organizational identification on turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 69, 477–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2006.05.006

Miles, S. J., and Mangold, G. (2004). A conceptualization of the employee branding process. J. Relationsh. Market. 3, 65–87. doi: 10.1300/J366v03n02_05

Morhart, F. M., Herzog, W., and Tomczak, T. (2009). Brand-specific leadership. Turning employees into brand champions. J. Market. 73, 122–142. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.5.122

M’zungu, S. D., Merrilees, B., and Miller, D. (2010). Brand management to protect brand equity: A conceptual model. J. Brand Manage. 17, 605–617. doi: 10.1057/bm.2010.15

Ndubisi, N. O., Nataraajan, R., and Chew, J. (2014). Ethical ideologies, perceived gambling value, and gambling commitment: An Asian perspective. J. Bus. Res. 67, 128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.11.004

Papasolomou, I., and Vrontis, D. (2006). Using internal marketing to ignite the corporate brand: The case of the U.K. retail bank industry. J. Brand Manage. 14, 177–195. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550059

Piehler, R., King, C., Burmann, C., and Xiong, L. (2016). The importance of employee brand understanding, brand identification, and brand commitment in realizing brand citizen behaviour. Eur. J. Market. 50, 1575–1601. doi: 10.1108/EJM-11-2014-0725

Piha, L. P., and Avlonitis, G. J. (2018). Internal brand orientation: Conceptualisation, scale development and validation. J. Market. Manage. 34, 370–394. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.722057

Pratt, M. B. (1998). “To be or not to be: Central questions in organizational identification,” in Identity in organizations, eds D. A. Whetton and P. C. Godfrey (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 171–208. doi: 10.4135/9781452231495.n6

Punjaisri, K., and Wilson, A. (2007). The role of internal branding in the delivery of employee brand promise. J. Brand Manage. 15, 57–70. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550110

Punjaisri, K., Wilson, A., and Evanschitzky, H. (2008). Exploring the influences of internal branding on employees’ brand promise delivery: Implications for strengthening customer–brand relationships. J. Relationsh. Market. 7, 407–424. doi: 10.1080/15332660802508430

Rafiq, M., and Ahmed, P. K. (2000). Advances in the internal marketing concept: Definition, synthesis and extension. J. Serv. Market. 14:6. doi: 10.1108/08876040010347589

Rajaguru, R. (2014). Motion picture-induced visual, vocal and celebrity effects on tourism motivation: Stimulus organism response model. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 19, 375–388. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2013.764337

Ranjbarian, B., Shekarchizade, Z., and Momeni, Z. (2010). Celebrity endorser influence on attitude toward advertisements and brands. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 13, 399–407.

Saleem, F. Z., and Iglesias, O. (2016). Mapping the domain of the fragmented field of internal branding. J. Prod. Brand Manage. 25, 43–57. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-11-2014-0751

Schimmelpfennig, C. (2018). Who is the celebrity endorser? A content analysis of celebrity endorsements. J. Int. Consum. Market. 30, 220–234. doi: 10.1080/08961530.2018.1446679

Scott, S. G., and Lane, V. R. (2000). A stakeholder approach to organizational identity. Acad. Manage. Rev. 25:43. doi: 10.2307/259262

Sherif, C. W., Sherif, M., and Nebergall, R. E. (1965). Attitude and attitude change: The social judgment-involvement approach. Philadelphia: Saunders, 127–167.

Shostack, G. L. (1987). Service positioning through structural change. J. Market. 51, 34–43. doi: 10.1177/002224298705100103

Smidts, A., Pruyn, A. T. H., and Van Riel, C. B. M. (2001). The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Acad. Manage. J. 44, 1051–1062. doi: 10.5465/3069448

Surana, R. (2008). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsement in India (Master’s thesis). Nottingham: The University of Nottingham.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 33, 1–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.33.020182.000245

Thomas, K. A., DeScioli, P., and Pinker, S. (2018). Common knowledge, coordination, and the logic of self-conscious emotions. Evol. Hum. Behav. 39, 179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2017.12.001

Thomson, M. (2006). Human brands: Investigating antecedents to consumers’ strong attachments to celebrities. J. Market. 70, 104–119. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.70.3.104

Tyler, T. R. (1999). “Why people cooperate with organizations: An identity-based perspective,” in Research in organizational behavior, eds R. I. Sutton and B. M. Staw (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press), 201–247.

Tyler, T. R., Degoey, P., and Smith, H. J. (1996). Understanding why the fairness of group procedures matters: A test of the psychological dynamics of the group-value model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 913–930. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.913

Urde, M. (1994). Brand orientation–a strategy for survival. J. Consum. Market. 11, 18–32. doi: 10.1108/07363769410065445

Urde, M. (1999). Brand orientation: A mindset for building brands into strategic resources. J. Mark. Manage. 15:117. doi: 10.1362/026725799784870504

Urde, M., Baumgarth, C., and Merrilees, B. (2013). Brand orientation and market orientation—From alternatives to synergy. J. Bus. Res. 66, 13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.018

Verplanken, B., and Holland, R. W. (2002). Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82:434. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.3.434

Wilden, R., Gudergan, S., and Lings, I. (2010). Employer branding: Strategic implications for staff recruitment. J. Market. Manage. 26, 56–73. doi: 10.1080/02672570903577091

Wong, H. Y., and Merrilees, B. (2005). A brand orientation typology for SMEs: A case research approach. J. Prod. Brand Manage. 14, 155–162. doi: 10.1108/10610420510601021

Wong, Y. W., and Merrilees, B. (2007). Closing the marketing strategy to performance gap: The role of brand orientation. J. Strateg. Market. 15, 387–340. doi: 10.1080/09652540701726942

Wright, P., Kroll, M., Pray, B., and Lado, A. (1995). Strategic orientations, competitive advantage, and business performance. J. Bus. Res. 33, 143–151. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(94)00064-L

Keywords: organization identification, brand orientation, celebrity endorsement effectiveness, employee pride, social identity theory

Citation: Abdullah M, Ghazanfar S, Ummar R and Shabbir R (2022) Role of celebrity endorsement in promoting employees’ organization identification: A brand-based perspective. Front. Psychol. 13:910375. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.910375

Received: 01 April 2022; Accepted: 04 August 2022;

Published: 08 September 2022.

Edited by:

T. Ramayah, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), MalaysiaReviewed by:

Eduardo Moraes Sarmento, Lusophone University of Humanities and Technologies, PortugalZubair Akram, Zhejiang Gongshang University, China

Larissa Batrancea, Babeş-Bolyai University, Romania

Copyright © 2022 Abdullah, Ghazanfar, Ummar and Shabbir. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rizwan Shabbir, cml6d2Fuc2hhYmJpckBnY3VmLmVkdS5waw==

Muhammad Abdullah

Muhammad Abdullah Sidra Ghazanfar

Sidra Ghazanfar Rakhshan Ummar2

Rakhshan Ummar2 Rizwan Shabbir

Rizwan Shabbir