- Millennium Nucleus on the Evolution of Work, Santiago, Chile

This paper presents a mediation–moderated model of the relationship between psychological empowerment, work engagement, age, and task performance. I seek to provide a more nuanced understanding of the mediating role of work engagement in the positive effect of psychological empowerment on task performance. Further, I explore employee age as a moderating factor in this mediation. I used online surveys among a sample of Latin American textile industry employees to capture individual perceptions about psychological empowerment, work engagement, and task performance. I modeled a mediation–moderated model using Hayes’ Process macro. The results confirm that the positive impact of employee psychological empowerment on task performance is partially mediated by work engagement. In addition, age was a significant moderator of the mediation effect. This study expands knowledge about how the psychological empowerment–work engagement relationship can predict task performance, including age as a boundary condition. Following the Job Demands–Resources theory, I also prove that conceptualizing psychological empowerment as a personal resource can benefit the integration of psychological empowerment and the work engagement stream of research. Moreover, the findings may help human resources management (HRM) researchers and practitioners acknowledge contextual differences in understanding the combined effects of psychological empowerment and work engagement. For instance, textile industry human resources managers can develop specific age–based human resource systems that empower and engages employees from emerging economies.

Introduction

In organizational psychology and human resources management (HRM), there has been a growing interest in studying the antecedents of task performance. In specific, HRM in textile industry companies are primarily focused on task performance (International Labour Organization [ILO], 2021). The concept of task performance is defined as the employee’s behavior in pursuing the objectives set in advance. This performance is notably affected by the individual strategy to achieve these objectives (Maslach et al., 2001). This article expands current knowledge about how the psychological empowerment–work engagement relationship can predict task performance, including age as a boundary condition. Following the JD–R theory, I also prove that conceptualizing psychological empowerment as a personal resource can benefit the integration of psychological empowerment and work engagement theories.

Psychological empowerment represents the motivational construct of an intrinsic task, including four cognitions that reveal a personal orientation: competence, meaning, self–determination, and impact, and demonstrates cognitive directions about their job role (Spreitzer, 1995). Psychological empowerment and work engagement (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009; Bakker and Albrecht, 2018) have been related to individual positive results, such as task performance and wellbeing (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003; Walumbwa et al., 2011). The job demands–resources (JD–R) theory is one of the most used theories to explain work engagement. Work engagement occurs when an employee has high job demands and resources to respond to these demands (Juyumaya, 2019). The JD–R model explains the employee’s motivational and strain process.

Resources are work–related elements that help face job demands (Demerouti et al., 2001). Resources can be of two types: (1) Personal resources if they refer to the individual’s self–perceptions of himself (e.g., self–esteem, self–efficacy, and optimism); and (2) Job resources if they are elements of the environment, physical, psychological, or organizational, which are available for the employee to face job demands (e.g., transformational leadership, autonomy, and feedback). The level of psychological empowerment of employees has been studied as an essential personal resource that increases the levels of work engagement (Zhang and Bartol, 2010). Nevertheless, researchers need to explore new mediators and moderators between these constructs and different types of job performance. Also, research needs to consider a wide range of samples (e.g., non–US samples, non–Students’ samples) and underexplored contexts (e.g., Latin America, textile industry). The study of work engagement moves away from the historical vision that has prevailed in the business world: the conception that a job is functional when the person performs their role and only dedicates themselves to it through a mechanized mode associated with the value chain. This is because work engagement theories study phenomena that had not previously been considered, such as vigor (energetic component), dedication (emotional component), and absorption (cognitive component) (Bakker and Demerouti, 2016).

This research explores the mediator role of work engagement in the relationship between psychological empowerment and task performance. Furthermore, I explore the role of employee age as a moderating factor in this relationship. In doing so, I seek to provide a more nuanced understanding of the mediating role of work engagement and the moderator role of age in the positive effect of psychological empowerment on task performance. Additionally, this research considers a poorly studied sample: Latin American textile industry employees. This is why this study diagnoses the levels of psychological empowerment, work engagement, and task performance of the employees in this industry, which is a valuable input for managerial decisions in HRM.

This article is structured as follows: first, this work develops the theoretical framework. Next, I explain the methodology. I modeled a first–stage mediation–moderated model using Hayes’ Process macro. The results confirm that the positive impact of psychological empowerment on task performance is mediated by work engagement. Interestingly, age was a significant moderator of the mediation effect. Finally, the final sections discuss the results, outline theoretical and practical implications for HRM, and present the conclusions of this study.

Theoretical framework

Psychological empowerment

Psychological empowerment is a phenomenon addressed by the field of organizational psychology. At the individual level, psychological empowerment is the ability of the person to feel responsible and the protagonist of their own life. At a corporate level, it is the opportunity for employees to be more efficient in their operation and take on creative challenges in their work and daily tasks (Spreitzer, 1995). The activation of individuals’ resources positively impacts the development of their functions at the individual, group, and organizational levels, allowing for sustained improvements (Deci et al., 1999; Schaufeli and Salanova, 2007).

According to Spreitzer (1995), psychological empowerment represents the motivational construct of an intrinsic task, including four cognitions that reveal a personal orientation: (1) Meaning, which refers to the alignment between one’s work role and one’s own beliefs, values, and standards; (2) Self–determination, is an individual’s sense of autonomy or control concerning the initiation or regulation of one’s actions; (3) Competence, refers to the belief in one’s capability to perform work activities successfully; and (4) Impact, is the belief that one can make a difference in the managerial process; that one could influence operational outcomes in the work unit. The four dimensions are independent, distinct, related, and mutually reinforcing, qualities that capture a dynamic state or active orientation toward work.

Work engagement

Schaufeli and Bakker (2003) define work engagement as a positive, fulfilling, work–related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption. Following JD–R theory, work engagement is the mental state that occurs when employees have high job demands and increased job and personal resources to respond to these job demands. Job demands are the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects that require sustained physical and psychological effort and are associated with specific physiological and psychological costs (Demerouti et al., 2001). Job resources refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving work goals, reducing job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, or stimulating personal growth, learning, and development, while the personal resources if they refer to the individual’s self–perceptions of himself (Bakker and Demerouti, 2016).

Previous research (e.g., Xanthopoulou et al., 2009; Walumbwa et al., 2011; Salessi and Omar, 2016; Juyumaya, 2018) has shown that engaged employees will perform better than others. Work engagement should not be confused with concepts such as job satisfaction, organizational happiness, work addiction, and even its opposite, the mental state of exhaustion or sustained stress, known as burnout syndrome. Burnout is a feeling of failure and an exhausted and spent existence resulting from an overload due to the employee’s demands of energy, personal resources, or spiritual strength (Maslach and Leiter, 2008; Bernd and Beuren, 2021).

Task performance

Task performance is another construct that has received the most attention from researchers of HRM, organizational behavior, strategic management, and organizational psychology. Possibly, it is famous since the competitiveness and productivity of organizations are closely linked to the individual performance of their members (Greguras et al., 2007). Hence, identifying its determinants and consequences has been a priority for various scholars, practitioners, and researchers. The lack of consensus about task performance measurement has led to the appearance of numerous scales to evaluate it. The specialized literature on task performance postulates more than eighty instruments to measure individual performance at a general level and more than forty scales to assess performance in more specific contexts (Wells and Welty–Peachey, 2011).

However, most of the instruments developed to date fail to measure all the dimensions that make up individual performance. On the other hand, using different scales to measure the dimensions of task performance can cause some redundancy in the questions, affecting the instrument’s application. It could even negatively impact the validity of the statistical analysis results due to increased correlations between the items (Murphy, 1990). Faced with the ambiguities caused by individual performance measurement, Koopmans et al. (2013) developed a generic instrument to evaluate it. The instrument, identified with the name of the personal task performance scale, has been designed to measure the behaviors of employees rather than their effectiveness.

The first attempts to explore generic task performance focused heavily on task requirements, with research focusing on technical competence, role performance, and task–specific competence, among others (Viswesvaran and Ones, 2000). Generic task performance models use broad dimensions to delimit the construct. However, models developed for specific jobs and contexts are based on narrower and personalized dimensions to describe the elements of task performance. Task performance is an essential dimension of generic task performance. It is found in the construct’s vast majority of explanatory models (e.g., Rodrigues and Rebelo, 2021).

Following Koopmans et al. (2013), task performance is composed of four dimensions: (1) Performance in the task; (2) Performance in context; (3) Counterproductive behaviors; and (4) Adaptive performance. These dimensions include the behaviors inherent to the technical tasks of the work position of the organization members. According to Koopmans et al. (2013), the performance of the task implies the performance of the specific or technical duties associated with the job. Therefore, it is related to the technical core of an organization and the activities directly or indirectly related to the transformation of organizational resources and capacities into appropriate products or services for economic exchange. This article analyzes the mediating effect of work engagement on the relationship between psychological empowerment and task performance.

The age effect

The relationships between psychological empowerment, work engagement, and task performance can be affected by demographic elements linked to individuals’ attitudes, values, and behaviors (Hofstede et al., 2010). Workforce aging and the need to work longer imply several challenges worldwide (Yeves et al., 2019). This paper proposes that the evolution of society, expressed in the emergence of different generational cohorts (e.g., baby boomers and centennials), might affect how employees experience psychological empowerment. For instance, the twenty-first century brought more individualism, competitiveness, and pressure to succeed. It increased the expectations of more horizontal relations and reduced power distance. In this context, the need for recognition was enhanced among younger employees, given the desire to excel among peers and establish closer relations with the leader (Didier and Luna, 2017). Then, I suggest that psychological empowerment on task performance will be more assertive in younger generations vs. older generations (baby boomers and generation X vs. millennials and centennials).

Previous research on social exchange theory has shown that reciprocity norms are more important among shortly tenured employees (Bal et al., 2013). As individuals shape their perceptions of the nature and dynamics of an exchange relationship, the reception of social benefits by the employer can boost a more favorable exchange expectation in younger employees. Similarly, as younger generations begin to understand and make sense of employment relationships through their interactions with organizational agents, psychological empowerment should differentially create more positive changes in them, in contrast to more experienced employees who have developed a more classical mindset of their employment relationship. In Latin America, this moderating effect could be more prevalent, as collectivism is inherently rooted in creating positive social exchanges based on reciprocity.

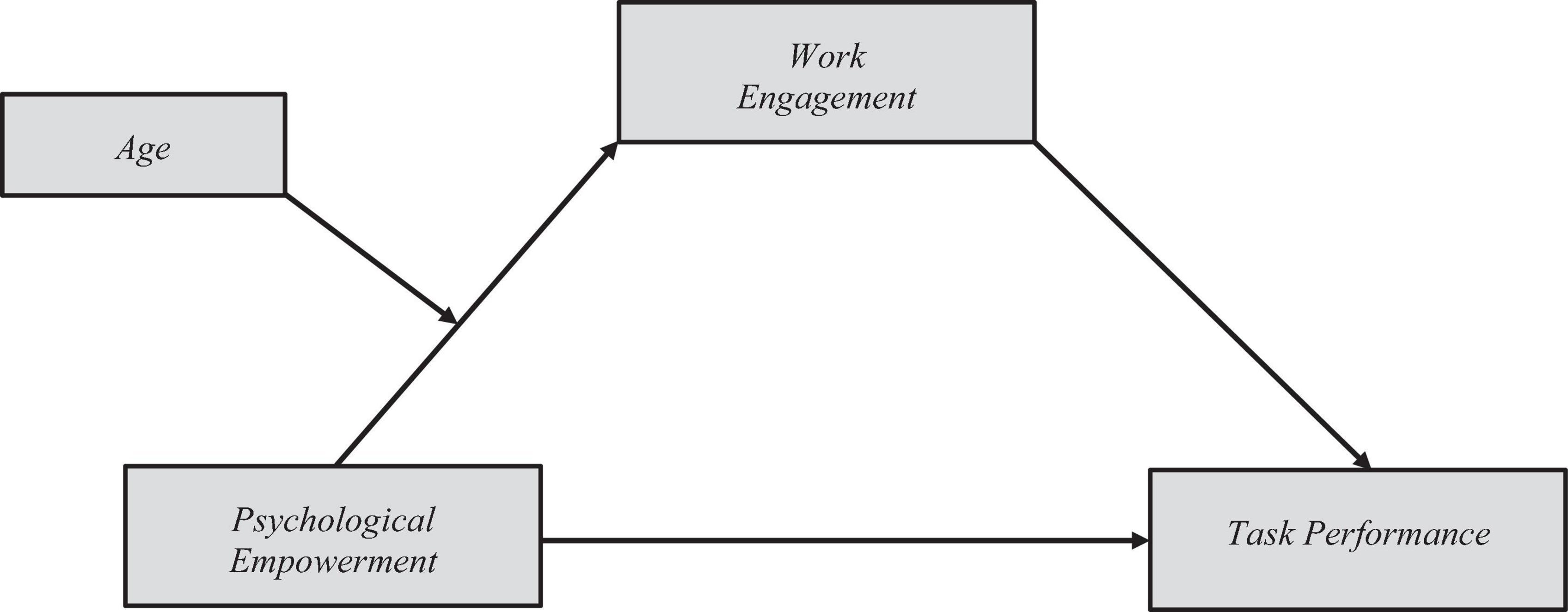

These collectivistic values could be learned by employees before their initial working experiences but are reinforced and confirmed when interacting with leaders. Moreover, Atwater et al. (2009) suggested that feedback is less likely to be found from supervisors in cultures such as Latin American culture. It is easier to obtain feedback from peers. Therefore, it is more presumable that the effects of psychological empowerment are more meaningful in younger generations. On this basis, I propose a mediation–moderated model. Figure 1 shows the model and the following hypothesis,

Hypothesis: The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between psychological empowerment and task performance is moderated by employee age, with the effect being more substantial for younger employees.

Methods

Data collection and sample

I designed a cross–sectional study and followed a quantitative approach using surveys. The online survey method was used for data collection. This method has multiple benefits, like a higher response rate compared to the manual distribution of a questionnaire (Rasool et al., 2021). I used Google Forms to conduct the experiment and automatically collected all the responses. This will allow the validation of the hypothesis through statistical analysis.

The study population was textile industry employees from Chile. The population was 655.257 employees in 2019 (SOL Foundation, 2022). Sample size = 196 (95% confidence). Employees worked in different communes of the metropolitan region of Chile. The final sample consisted of 200 employees (n = 200; female = 80%). I note that “The Chilean Social Outbreak” and the “Coronavirus Pandemic” did not affect the process because the data collection was carried out between January and September 2019.

Measures

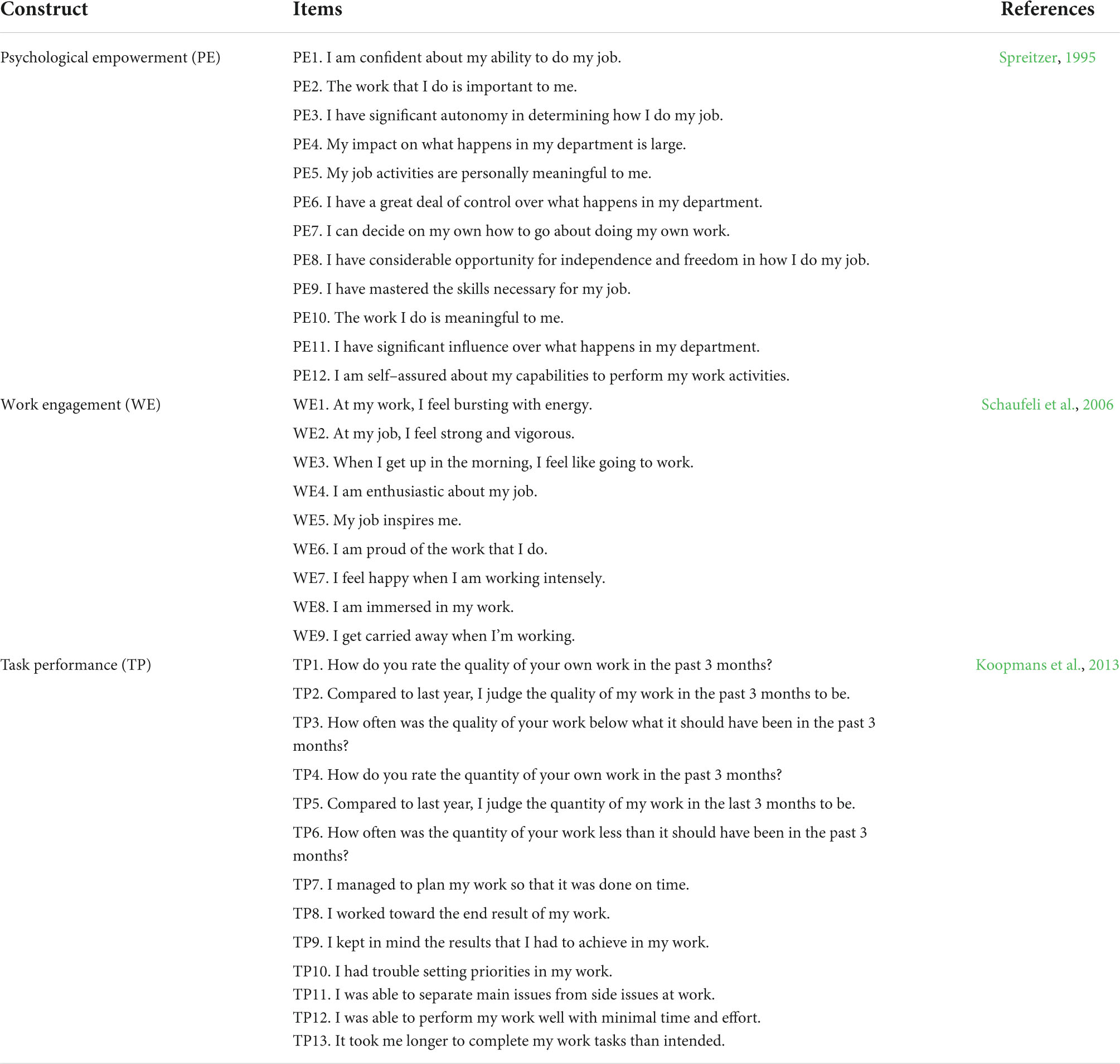

The methodology used is supported by a positivist epistemology, which promotes knowledge based on the formulation of hypotheses and empirical verification through the scientific method. This methodology requires data collection instruments that maintain the objective nature of the research. To this end, the present study used a survey that contained three Likert–type scales: (1) Psychological empowerment; (2) Work engagement; and (3) Task performance. Table 1 shows the items and authors of the used scales.

The applied survey consisted of a presentation of the study, the informed consent that ensured the confidentiality of the data and anonymity of the respondent, socio–demographic questions, and the three scales previously mentioned. All the scales followed a 5–point Likert–type response format, from “Strongly Disagree” = 1 to “Strongly Agree” = 5.

Psychological empowerment

Empowerment scale (Spreitzer, 1995). Spreitzer’s psychological empowerment scale (1995) measures perceived control, perceptions of competencies, and internalization of organizational goals and objectives. This research uses the 12 items Spanish validated version of Rivera et al. (2020).

Work engagement

UWES–9 scale (Schaufeli et al., 2006). This scale is available in two versions, including 17 items, and the abbreviated version, which includes nine items. I use the abbreviated version validated in Spanish by Juyumaya (2019).

Task performance

The Koopmans et al. (2013) task performance scale was used. The 13 items scale validated in Spanish by Gabini and Calzada (2015) was used.

Age

The study asked the age of each participant at the beginning of the survey. Then, I split the sample into two groups (high age/low age) to create a dummy variable.

Controls

In line with previous research (Walumbwa and Hartnell, 2011), we included participants’ age, gender, and work experience as control variables, because these variables can influence task performance.

Analysis strategy

The analyses were carried out using the statistical package SPSS v.23 and the Process macro extension (Hayes, 2013). The analysis strategy aimed to corroborate the existence of a possible mediation–moderated between the variables selected for the study. The data interpretation of this research is based on model 7 proposed by Hayes (2013). The normality test used was Pearson’s Chi–square, which allowed us to justify a parametric study. No missing data was found in this survey.

Results

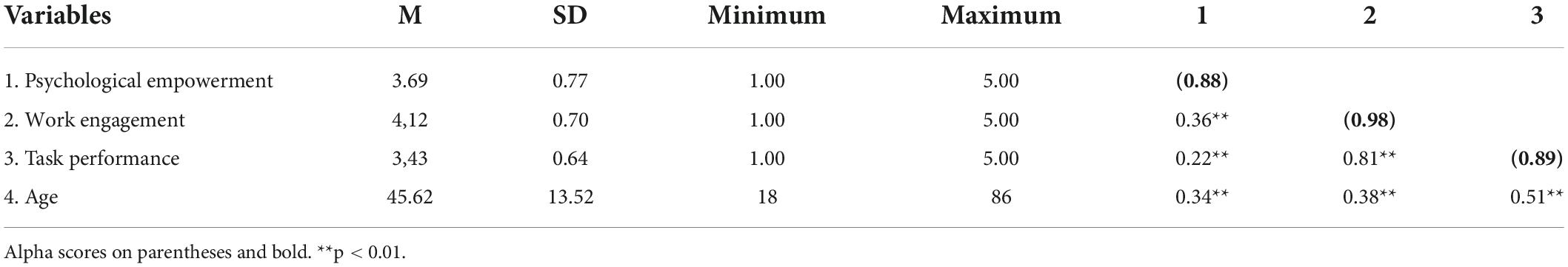

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha are available in Table 2. The correlations are positive and align with what has been reported. In the three variables used, the alpha exceeds the value of 0.80, which indicates that the scales were reliable.

Confirmatory factor analysis

This research conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). I tested the hypothesized three–factor model with psychological empowerment, work engagement, and task performance. The model fitted well the data [x2(108) = 2330.21; CFI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.05; RMSEA = 0.05], suggesting that participants were able to distinguish our key constructs. I also ran four alternative models merging pairs of constructs (psychological empowerment–work engagement; psychological empowerment–task performance; work engagement–task performance) and one model with a single–factor solution. Neither of these alternative models showed better fit indexes than the hypothesized model.

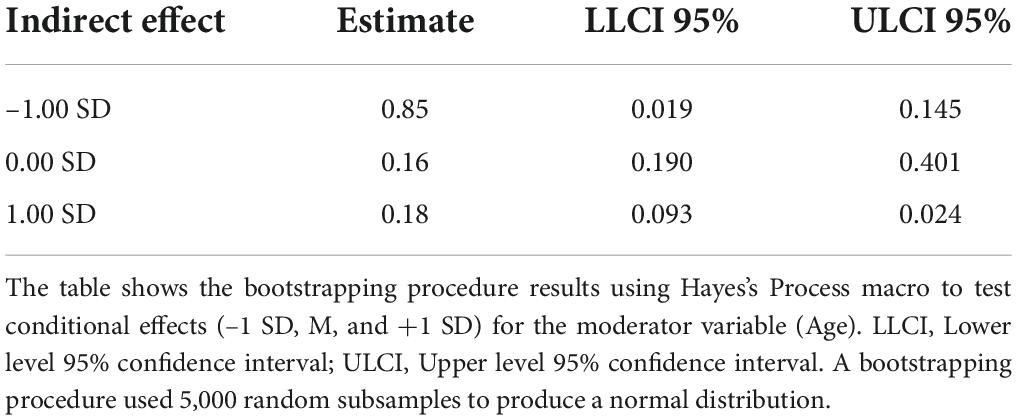

Mediation–moderated analysis

The main results of the mediation–moderated analysis are presented in Table 3. Table 3 shows the estimated and bootstrapped internals of work engagement (mediator) in the relationship between psychological empowerment and task performance for different levels of age (moderator) (+1 SD, M, −1 SD). I observe that the estimate of the mediation effect is significant and relatively constant at different levels of the moderator. The confidence interval of moderated mediation was different from zero [Estimate = 0.16, BootSE = 0.08, 95% CI: (0.19; 0.40)], suggesting that the mediation effect was moderated by employees’ age (Hayes, 2013).

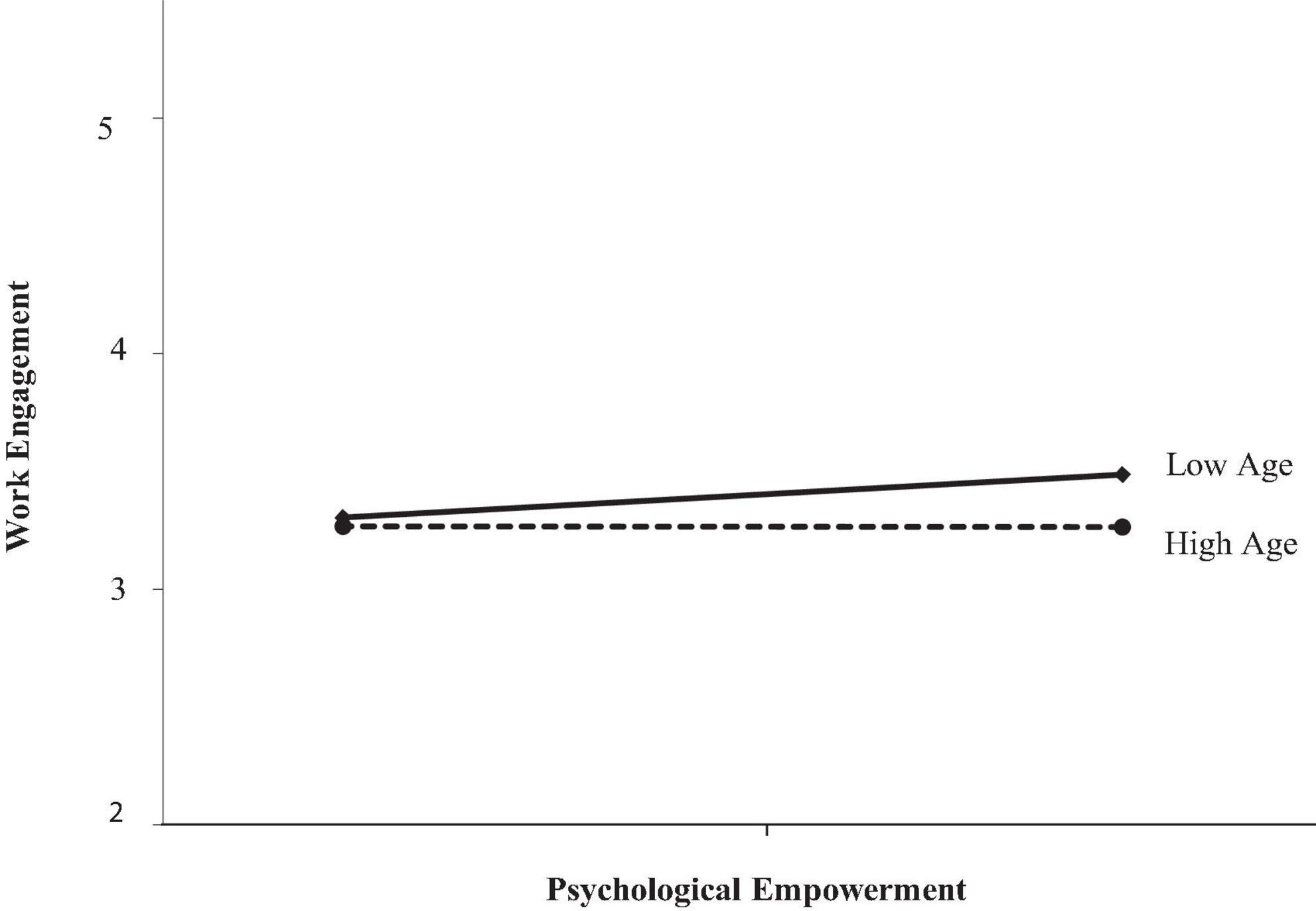

In Figure 2, the slope representing the relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement is positive for young employees and different from the same slope for older employees. Younger employees (low age: SD = −1.00) have higher engagement levels as perceived psychological empowerment increases. In comparison, work engagement levels for older employees (high age: SD = 1.00) appear unaffected by the psychological empowerment effect supporting the study’s hypothesis.

Discussion

Thanks to the results presented, the hypothesis of this study was supported. It is concluded that if employees are empowered in their capacities (i.e., with high levels of psychological empowerment), they will perform better when fulfilling their tasks. Furthermore, suppose employees are engaged (i.e., with high levels of work engagement). In that case, they will have even more positive repercussions on task performance. Moreover, I found that employees’ age moderates the mediation of psychological empowerment, work engagement, and task performance such that the mediation effect is more substantial for younger employees.

At the level of theoretical contribution, this study contributes to the theory of JD–R, which explains work engagement (Bakker, 2018). Psychological empowerment is a personal resource that helps respond to employees’ job demands in the textile industry. Hence, this study provides empirical evidence to understand work engagement in emerging economies. Scholars engaging in aging and HRM must study how different generational cohorts of employees experience psychological empowerment. Following other studies (e.g., Yeves et al., 2019), this paper delivers empirical evidence that the emergence of different generational cohorts (e.g., baby boomers and centennials) might affect how employees experience psychological empowerment and work engagement, and task performance.

The results support that work engagement mediates the relationship between psychological empowerment and task performance. Psychological empowerment is a crucial resource for facing job demands. Engaged employees have the energy (i.e., vigor), positive feelings (i.e., dedication), and attention (i.e., absorption) to perform better in the tasks (Bakker and Demerouti, 2016). As I mention, task performance is crucial for all industries, but even more in the textile industry. The presented results support the idea of Schaufeli and Salanova (2007) that engaged employees have more efficacy in their daily tasks. Engaged employees are happier at work, and their wellbeing and positive psychological state impact their task performance.

Practical implications

An essential significance of this study is related to the possibilities that the HRM in the textile industry has to create opportunities for employees to increase their levels of psychological empowerment and work engagement. These results highlight the prominence of recognizing the capabilities and attributes of the employees of an organization because if you are outstanding, the employees acquire security far beyond the work, reaching a personal level, which can bring multiple benefits to the individual, even beyond the work dimension (Rappaport, 1981; Riger, 1993). For instance, 360° performance evaluations would be quite indicated in the textile industry. This type of evaluation encourages the employee to empower himself and improve their task performance based on feedback from his co-employees, supervisors, customers, or clients and their own self–assessment.

This study delivers empirical evidence to scholars interesting in the textile industry. Scientific papers focused on employees in the textile industry are scarce. For this reason, gathering factual data regarding employees in this industry is a methodologically relevant task. The textile industry has similar features concerning the workforce composition in all the world countries since it mainly comprises women (Fashionunited, 2020). In the present research, the percentage of female participants was 80%. I encourage future studies to analyze the role of gender in the relationship between HRM practices and task performance or other contingent relationships.

The findings of this study can help business and management researchers and practitioners acknowledge contextual differences in understanding the combined effects of psychological empowerment and work engagement. Managers and practitioners may develop a specific age–based HRM system that empowers and engages employees. For example, the individually–driven work design process (i.e., job crafting) can better align the job with personal needs, goals, and skills (Wijngaards et al., 2022). Embedding strategies in people management practices that promote psychological empowerment and work engagement is a crucial source of competitive advantage based on developing individual capacities that are difficult to imitate. For instance, HRM areas can create organizational innovation strategies. These actions can build a positive corporate culture that benefits psychological empowerment and work engagement through supportive generational–based feedback (e.g., millennials mentoring baby boomers, and vice–versa) and, at the same time, influence sustainable organizational performance (Rasool et al., 2019).

Limitations and future research

Further research can study aspects related to the limitations of the present study. One limitation is the risk of common method variance due to using self–reported data. Future research can make an effort to solve this. Other limitations concern the study’s sample. Scholars from a wide range of perspectives should study employees in the textile industry from other Latin American countries, conduct longitudinal studies, and conduct comparative analyses between culturally different countries. Additionally, future research could continue to delve into other job or personal resources that increase work engagement (Juyumaya and Torres, 2020). For example, the study of the impact of new technologies and work arrangements on task performance, focusing on textile industry employees, can be a source of exciting future directions.

Conclusion

This paper presents a mediation–moderated model that analyzes the role of work engagement as a mediator in the relationship between psychological empowerment and task performance in the textile industry. In this way, I postulate that psychological empowerment increases work engagement, which in turn has, as a consequence, a higher task performance of the employees of this industry. Additionally, an employee’s age moderates the mediation effect of work engagement in the relationship between psychological empowerment and task performance, such that the mediation effect is more substantial for younger employees.

This article provides empirical evidence to develop the psychological empowerment, work engagement, and aging literature. Moreover, because this study investigates a poorly studied sample, it provides inputs to further theoretical analysis. For managerial practice, this study helps to manage organizations based on evidence. I promote that HRM managers consider psychological empowerment and work engagement as essential employee results. Likewise, the generation factor must be addressed. Thus, companies and businesses can promote the quality of working life, improve task performance, and build thriver organizations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Universidad Santo Tomas. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research initiative was supported by the National Research and Development Agency, 21190010 award granted to JJ.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Atwater, L., Wang, M., Smither, J. W., and Fleenor, J. W. (2009). Are cultural characteristics associated with the relationship between self and others’ ratings of leadership? J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0014561

Bakker, A. B. (2018). Job crafting among health care professionals: The role of work engagement. J. Nurs. Manage. 26, 321–331. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12551

Bakker, A. B., and Albrecht, S. (2018). Work engagement: current trends. Career Dev. Int. 23, 4–11. doi: 10.1108/CDI-11-2017-0207

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2016). Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273–285. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056

Bal, P. M., De Cooman, R., and Mol, S. T. (2013). The influence of organizational tenure is the dynamics of psychological contracts with work engagement and turnover intention. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 22, 107–122. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2011.626198

Bernd, D. C., and Beuren, I. M. (2021). Self–perception of organizational justice and burnout in attitudes and behaviors in the work of internal auditors. Rev. Bras. Gestão Negócios 23, 422–438. doi: 10.7819/rbgn.v23i3.4110

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., and Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta–analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 125, 627–668. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., de Jonge, J., Janssen, P. P. M., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). Burnout and engagement at work as a function of demands and control. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 27, 279–286. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.615

Didier, N., and Luna, J. F. (2017). ¿Dónde estamos? La cultura laboral chilena desde Hofstede. Rev. Colombiana Psicol. 26, 295–311. doi: 10.15446/rcp.v26n2.60557

Gabini, S., and Calzada, C. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de rendimiento laboral individual de Koopmans [Conference session], in Proceedings of the Congreso Internacional de la Facultad de Psicología, (Argentina: Universidad Nacional de la Plata).

Greguras, G. J., Robie, C., Born, M. P., and Koenigs, R. J. (2007). A social relations analysis of team performance ratings. Int. J. Select. Assess. 15, 434–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2389.2007.00402.x

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression–Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press, doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., and Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software for the Mind. New York, NY: McGraw–Hill.

International Labour Organization [ILO]. (2021). World employment and social outlook: trends 2021. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Juyumaya, J. (2018). Work engagement, satisfaction and task performance: the role of organizational culture. Estud. Admin. 25, 32–49. doi: 10.5354/0719-0816.2018.55392

Juyumaya, J. (2019). Utrecht scale of work engagement in chile: measurement, reliability, and validity. Estud. Admin. 26, 35–50. doi: 10.5354/0719-0816.2019.55405

Juyumaya, J., and Torres, J. P. (2020). Work engagement in a digital disruption era: new job demands and resources. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2020:17251. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2020.17251abstract

Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C., Hildebrandt, V., van Buuren, S., van der Beek, A., and De Vet, H. (2013). Development of an individual task performance questionnaire. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 62, 6–28. doi: 10.1108/17410401311285273

Maslach, C., and Leiter, M. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 498–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Leiter, M. (2001). Job burnout. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 52, 397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Murphy, K. R. (1990). Task performance and productivity, in Psychology in Organizations: Integrating Science and Practice, eds K. R. Murphy and F. E. Saal (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum).

Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: a social policy of empowerment over prevention. Am. J. Commun. Psycholo. 9, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00896357

Rasool, S. F., Samma, M., Wang, M., Zhao, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2019). How human resource management practices translate into sustainable organizational performance: the mediating role of product, process and knowledge innovation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 12, 1009–1025. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S204662

Rasool, S. F., Wang, M., Tang, M., Saeed, A., and Iqbal, J. (2021). How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: the mediating role of organizational support and employee well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2294. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052294

Riger, S. (1993). What is wrong with empowerment. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 21, 279–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00941504

Rivera, D., Mamani, C., and Elias, R. (2020). Validación del instrumento psychological empowerment “EP” en trabajadores de la empresa call center Atento, Lima. Rev. Invest. Valor Agregado 7, 1–10. doi: 10.17162/riva.v7i1.1411

Rodrigues, N., and Rebelo, T. (2021). Unfolding the impact of trait emotional intelligence facets and co–worker trust on task performance. Rev. Bras. Gestão Negócios 23, 470–487. doi: 10.7819/rbgn.v23i3.4111

Salessi, S., and Omar, A. (2016). Generic job satisfaction: psychometric properties of a scale to measure it. Rev. Altern. Psicol. 26, 329–345. doi: 10.15689/ap.2020.1904.15804.02

Schaufeli, W. B., and Bakker, A. B. (2003). Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., and Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross–national study. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 66, 701–716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., and Salanova, M. (2007). Efficacy or inefficacy that is the question: burnout and work engagement, and their relationships with efficacy beliefs. Anxiety Stress Coping 20, 177–196. doi: 10.1080/10615800701217878

SOL Foundation (2022). Homework: Pandemic and Transformations in Chile’s Textile Work and the Clothing Chain. Triesen: SOL Foundation.

Spreitzer, G. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 1442–1465. doi: 10.2307/256865

Viswesvaran, C., and Ones, D. S. (2000). Perspectives on models of task performance. Int. J. Select. Assess. 8, 216–226. doi: 10.1111/1468-2389.00151

Walumbwa, F. O., and Hartnell, C. A. (2011). Understanding transformational leadership–employee performance links: the role of relational identification and self–efficacy. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 153–172. doi: 10.1348/096317910X485818

Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., and Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: the roles of leader–member exchange, self–efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decision Process. 115, 204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.11.002

Wells, J. E., and Welty–Peachey, J. (2011). Turnover intentions: do leadership behaviors and satisfaction with the leader matter? Team Perform. Manag. 17, 23–40. doi: 10.1108/13527591111114693

Wijngaards, I., Pronk, F.R., Bakker, A. B., Burger, M. J. (2022). Cognitive crafting and work engagement: a study among remote and frontline health care workers during the COVID–19 pandemic. Health Care Manag. Rev. 47, 227–235. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000322

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 74, 235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.003

Yeves, J., Bargsted, M., Cortes, L., Merino, C., and Cavada, G. (2019). Age and perceived employability as moderators of job insecurity and job satisfaction: a moderated moderation model. Front. Psychol. 10:799. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00799

Keywords: psychological empowerment, work engagement, task performance, age, moderated mediation, human resources management

Citation: Juyumaya J (2022) How psychological empowerment impacts task performance: The mediation role of work engagement and moderating role of age. Front. Psychol. 13:889936. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.889936

Received: 04 March 2022; Accepted: 18 August 2022;

Published: 16 September 2022.

Edited by:

Ana Campina, Fernando Pessoa University, PortugalReviewed by:

Samma Faiz Rasool, Zhejiang University of Technology, ChinaSusmita Mukhopadhyay, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India

Copyright © 2022 Juyumaya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jesus Juyumaya, ai5qdXl1bWF5YUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Jesus Juyumaya

Jesus Juyumaya